Abstract

Liver transplantation (LT) is the final step in a complex care cascade. Little is known about how race, gender, rural versus urban residence, or neighborhood socioeconomic indicators impact a patient's likelihood of LT waitlisting or risk of death during LT evaluation. We performed a retrospective cohort study of adults referred for LT to the Indiana University Academic Medical Center from 2011 to 2018. Neighborhood socioeconomic status indicators were obtained by linking patients' addresses to their census tract defined in the 2017 American Community Survey. Descriptive statistics were used to describe completion of steps in the LT evaluation cascade. Multivariable analyses were performed to assess the factors associated with waitlisting and death during LT evaluation. There were 3454 patients referred for LT during the study period; 25.3% of those referred were waitlisted for LT. There was no difference seen in the proportion of patients from vulnerable populations who progressed to the steps of financial approval or evaluation start. There were differences in waitlisting by insurance type (22.6% of Medicaid vs. 34.3% of those who were privately insured; p < 0.01) and neighborhood poverty (quartile 1 29.6% vs. quartile 4 20.4%; p < 0.01). On multivariable analysis, neighborhood poverty was independently associated with waitlisting (odds ratio 0.56, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.38–0.82) and death during LT evaluation (hazard ratio 1.49, 95% CI 1.09–2.09). Patients from high‐poverty neighborhoods are at risk of failing to be waitlisted and death during LT evaluation.

Abbreviations

- ACS

American Community Survey

- AIH

autoimmune hepatitis

- ALD

alcohol‐related liver disease

- CI

confidence interval

- ESLD

end‐stage liver disease

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HR

hazard ratio

- LT

liver transplantation

- MELD

Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease

- NASH

nonalcohol‐related steatohepatitis

- RUCA

rural–urban commuting area

- SD

standard deviation

- SES

socioeconomic status

- SNAP

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

- OR

odds ratio

INTRODUCTION

End‐stage liver disease (ESLD) is more prevalent in some vulnerable populations, yet these groups have lower access to liver transplantation (LT).[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ] Vulnerable populations in health care are defined as groups experiencing significant disparities in life expectancy, access to and use of health care services, morbidity, and mortality.[ 5 ] Racial and ethnic minorities, women, those with low socioeconomic status (SES), and those living in rural settings are known to have disparities in access to LT.[ 3 ] Bryce et al.[ 6 ] in a multicenter Pennsylvania cohort demonstrated that Black patients, those who lacked commercial insurance, and women were less likely to undergo LT evaluation and waitlisting. A more recent study found that the odds of being waitlisted were lower for patients of Black race, patients with alcohol‐induced hepatitis, those who were unmarried, those with inadequate insurance, and those with lower annual household income.[ 7 ]

These studies provide insight into disparities in referral and waitlisting of vulnerable populations, but focus largely on individual social needs versus community social determinants.[ 8 ] A decade of research has demonstrated that where we live, work, and interact (i.e., our neighborhood) are important upstream determinants of health.[ 9 ] Neighborhood determinants are not simply surrogates markers for individual social needs. Understanding the full complexity of a patient's situation is necessary to help them navigate complex care cascades. Furthermore, relying on individual needs such as income may result in late recognition of those at risk for failure to progress through the LT evaluation cascade as these data may not be available about patients until after a full social work evaluation is completed. Using neighborhood SES indicators, that can be readily obtained by using a patient's address, populations at risk for failure to progress from referral might be identified on arrival. With early identification, navigation programs might be implemented to help improve waitlisting of vulnerable populations. Finally, these studies did not explore the real risk of death during evaluation without prompt waitlisting for these at‐risk populations.

To obtain access to LT, the standard of care, life‐saving treatment for ESLD, one must complete a complex LT evaluation cascade.[ 3 ] No study has examined the impact of neighborhood SES on waitlisting or the risk vulnerable populations have for death during the LT evaluation. Understanding these factors is a necessary step toward developing targeted interventions to achieve health equity. Here we explore the role that race, gender, geography, and neighborhood SES play on waitlisting and death during LT evaluation.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study population

All adult patients who were referred to the Indiana University Academic Medical Center for LT evaluation from December 2011 to March 2018 were identified using our center's transplantation database and included in the study. The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at our institution and is compliant with ethical conduct of research. Patients who were referred for multiorgan evaluation were excluded from the study.

Exposures

Exposures of interest included race, gender, insurance type, rural versus urban residence, and neighborhood‐level SES indicators. Race and sgender were defined by self‐report in the transplantation database as Black, White, or other, and male or female, respectively. Other race was defined as those who identified themselves as, but not limited to, Hispanic, Asian Pacific Islander, Native American, or declined to identify. Individual patient insurance types were documented at the time of referral in the LT database and were defined as private, Medicare, and Medicaid (included Medicare patients with Medicaid supplement). Patients with Indiana Medicaid have the same evaluation requirements as those with private insurance and have no insurance‐specific barriers to waitlisting. Rural versus urban residence and neighborhood SES indicators were obtained by linking patients' addresses to a census tract defined in the 2017 American Community Survey (ACS). The ACS provides data about social, economic, housing, and demographic characteristics for multiple geographic areas down to the census tract level, which are small areas of approximately 1200–8000 (average 4000) persons.[ 10 ] Census tracts provide more granularity than zip code (73,000 areas vs. 43,000 zip codes in the United States).[ 10 ] We used the rural–urban commuting area (RUCA) codes to define rural versus urban residence.[ 11 ] We defined urban as metropolitan (≥50,000 residents) and micropolitan (10,000–49,999 residents). We defined rural as small town (2500–9999 residents) and rural (<2500).[ 12 ]

Neighborhood SES measurement

Two composite indexes including the Social Deprivation Index and the Area Deprivation Index have been used to describe “neighborhood deprivation.”[ 13 , 14 ] Such composite indexes have robustness in documenting the extent of socioeconomic disparities; the Area Deprivation Index, for example, includes 21 ACS variables. However, in that robustness they can lack precision. For a large public health intervention work, a robust definition of deprivation is critical. Our aim here, however, was to be precise in determining whether there was an association between neighborhood SES and waitlisting. Therefore, we explored four individual indicators of neighborhood SES: the proportion of residents living in a patient's neighborhood with (1) income below the poverty level (poverty defined by the ACS), (2) education less than high school, (3) receiving cash or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP; Cash SNAP), and (4) insured by Medicaid. Poverty can be defined by federal income standards and can also be indicated by the need for assistance through programs such as SNAP and Medicaid, which each have different income and employment requirements, thus capturing different populations. Any variables that were collinear would not need to be included in final models.

Covariates

Covariates of interest were captured from the LT database and the electronic medical records. Patient age was captured at the time of referral for LT. Underlying liver disease was defined as hepatitis C virus (HCV), alcohol‐related liver disease (ALD), nonalcohol‐related steatohepatitis (NASH), autoimmune liver disease (autoimmune hepatitis), cholestatic liver diseases including primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis, and hepatitis B virus infection. All other underlying liver diseases were classified as other. Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were also identified. The Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score at the time of referral was also captured for each patient. Marital status was defined as single (never married, divorced, or widowed) and married/life partner. Positive alcohol biomarkers were defined as having a positive serum ethanol, ethyl glucuronide, carbohydrate‐deficient transferrin, or phosphatidylethanol test after LT evaluation had begun. One or more of these tests is run on all patients at the start of LT evaluation. Charlson Comorbidity Index was captured on each patient including comorbidities captured in our electronic medical record from entry into our health system until 6 months after an LT evaluation began.

In those patients who had an evaluation started but were not waitlisted, a manual transplantation database chart review was preformed to identify reasons for failure to be waitlisted for LT.

Outcomes

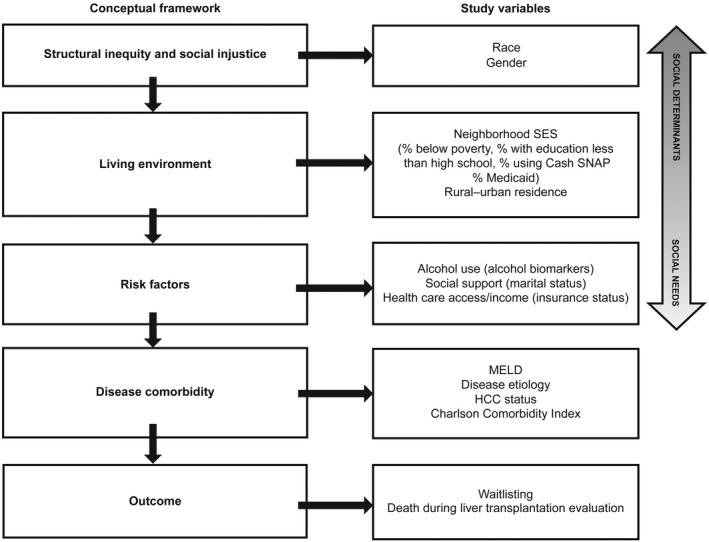

The primary outcome was waitlisting for LT. The secondary outcome was death during LT evaluation. A patient's risk for the study outcomes are a result of structural inequity, living environment, risk factors, and disease severity. A conceptual framework for a potential relationship between the exposures, covariates, and outcomes is provided in Figure 1 and is adapted from Alcaraz et al.'s[ 15 ] model on addressing social determinants.

FIGURE 1.

The role of the social determinants of health in LT outcomes. Study exposures, covariates, and outcomes superimposed on a conceptual framework for understanding the social determinants of health and transplantation outcomes.[15]

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations and compared with t‐tests and analysis of variance. MELD score was reported as a median and compared using Wilcoxon rank sum test. Categorical variables were described with number and percentage and compared with chi‐square test.

The ACS provides the proportion of residents in the census tract with each socioeconomic indicator of interest, for example, the proportion of residents in each census tract with incomes below the poverty level. The population referred for LT was divided into quartiles for each neighborhood SES variable, with quartile 4 having the highest proportion of residents with that variable. The proportion of residents living in the census tract with each neighborhood SES variable of interest was then reported by quartile.

For the primary outcome of waitlisting, logistic regression was used to assess the association between the exposures of interest and waitlisting. Waitlisting was also explored using the method of Fine and Gray with death during LT evaluation as a competing risk.[ 16 ] For the secondary outcome of death during LT evaluation, we performed a survival analysis using a Cox proportional hazards models analyzing time‐to‐event with multivariable adjustments. Models were censored for (1) LT waitlisting, (2) evaluation end as documented by the transplantation database. Age at referral, race, and gender were included in all models. MELD score at referral, liver disease etiology, HCC status, individual insurance type, alcohol biomarkers, marital status, Charlson Comorbidity Index, rural versus urban residence, and neighborhood SES indicators were included in the models if the p value was <0.2 between the exposure and the outcome. We used Pearson correlation matrices to explore collinearity between the neighborhood SES indicators, race, and individual insurance type. Variables with a coefficient greater than or equal to 0.8 were considered collinear and not included in the final models.

For the primary outcome of waitlisting, all covariates were included in the multivariable model. For the secondary outcome of death during LT evaluation, the final model included age at referral, gender, MELD score at time of referral, liver disease etiology, HCC status, rural versus urban residence, individual insurance type, alcohol biomarkers, and neighborhood poverty level. Odds ratios (ORs) and hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Robust sandwich variance estimator was calculated, allowing for intragroup clustering on census tract.[ 17 ] All CIs, significance tests, and resulting p values were two‐sided, with an α level of 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical package Stata, release 14 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

There were 3454 patients referred for LT during the study period. The population was 5.83% Black and 1.93% other races; 38.7% were women (Table 1). The average age at referral was 55.4 ± 11.2 years. The most common underlying liver disease was HCV (30.3%), followed by ALD (22.0%) and NASH (20.9%). HCC was present in 17.9% of the cohort. The median MELD score at referral was 15 (interquartile range 11–20). Most patients had Medicaid (40.8%) as their primary insurance type, followed by private (29.8%) and Medicare (29.4; Table 1). The proportion of residents with income below the poverty level in quartile 1 was 4.3% compared with 27.1% percent in quartile 4 (Table 1). There was missingness for alcohol biomarkers (n = 107) and marital status (n = 302); for all other variables missingness was <30.

TABLE 1.

Clinical characteristics and neighborhood socioeconomic indicators of patients referred and waitlisted for LT

| All referred (N = 3454) | Waitlisted | Not waitlisted | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (SD) | 55.4 (11.2) | 55.0 (10.6) | 55.6 (11.4) | 0.09 |

| Race (N = 3260) | 0.02 | |||

| White | 3007 (92.2) | 796 (91.8) | 2211 (92.4) | |

| Black | 190 (5.83) | 45 (5.20) | 145 (6.10) | |

| Other | 63 (1.93) | 26 (3.00) | 37 (1.55) | |

| Gender (N = 3447) | 0.14 | |||

| Men | 2112 (61.3) | 554 (63.4) | 1558 (60.6) | |

| Women | 1335 (38.7) | 320 (36.6) | 1015 (39.5) | |

| Diagnosis (N = 3356) | <0.001 | |||

| HCV | 1017 (30.3) | 232 (26.6) | 785 (31.6) | |

| ALD | 739 (22.0) | 167 (19.2) | 572 (23.0) | |

| NASH | 702 (20.9) | 215 (24.7) | 487 (19.6) | |

| AIH | 133 (4.00) | 40 (4.60) | 93 (3.74) | |

| Cholestatic liver diseases | 230 (6.90) | 108 (12.4) | 122 (4.91) | |

| HBV | 60 (1.80) | 15 (1.72) | 45 (1.81) | |

| Other | 475 (14.2) | 95 (10.9) | 380 (15.3) | |

| HCC (N = 3454) | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 618 (17.9) | 195 (22.3) | 423 (16.4) | |

| No | 2836 (82.1) | 679 (77.7) | 2157 (83.6) | |

| MELD score (N = 2718) | 15 (11–20) | 16 (12–20) | ||

| Insurance type (N = 3131) | <0.001 | |||

| Private | 933 (29.8) | 320 (37.0) | 613 (27.1) | |

| Medicare | 921 (29.4) | 258 (29.8) | 663 (29.3) | |

| Medicaid | 1277 (40.8) | 288 (33.3) | 989 (43.7) | |

| Rural versus urban | 0.34 | |||

| Urban | 2918 (87.5) | 757 (88.4) | 2161 (87.2) | |

| Rural | 417 (12.5) | 99 (11.6) | 318 (12.8) | |

| Neighborhood SES | ||||

| Income below poverty (N = 3335) | 13.8 | 12.5 | ||

| Income below poverty quartiles (% of residents in neighborhood with income below poverty; N = 3335) | <0.001 | |||

| Q1 (4.3) | 840 | 249 | 591 | |

| Q2 (8.9) | 828 | 231 | 597 | |

| Q3 (15.0) | 843 | 208 | 635 | |

| Q4 (27.1) | 824 | 168 | 656 | |

| Education less than high school (N = 3335) | 5.2 | 4.9 | ||

| Education less than high school quartiles (% of residents in neighborhood with education less than high school; N = 3335) | 0.001 | |||

| Q1 (1.5) | 836 | 250 | 586 | |

| Q2 (3.3) | 842 | 210 | 632 | |

| Q3 (5.6) | 831 | 207 | 624 | |

| Q4 (10.6) | 826 | 189 | 637 | |

| Cash SNAP assistance (N = 3335) | 4.8 | 4.1 | ||

| Cash SNAP assistance quartiles (% of residents in neighborhood with Cash SNAP assistance; N = 3335) | <0.001 | |||

| Q1 (1.0) | 834 | 253 | 581 | |

| Q2 (2.8) | 836 | 246 | 590 | |

| Q3 (5.2) | 855 | 204 | 651 | |

| Q4 (10.2) | 810 | 153 | 657 | |

| Medicaid (N = 3335) | 18.1 | 9.9 | ||

| Medicaid quartiles (% of residents in neighborhood insured by Medicaid; N = 3335) | <0.001 | |||

| Q1 (6.6) | 834 | 252 | 582 | |

| Q2 (13.1) | 841 | 631 | 210 | |

| Q3 (20.3) | 840 | 638 | 202 | |

| Q4 (32.5) | 820 | 608 | 212 | |

Note: Data are presented as mean (SD), n (%), median (range), %, or n.

The column N provides total number referred while the row N provides the number referred for whom there was complete data. Note that the missigness for those who had an evaluation completed was less than 30 for all variables except alcohol biomarkers and marital status.

Abbreviations: AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ALD, alcohol‐related liver disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; LT, liver transplantation; MELD, Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease; NASH, nonalcohol‐related steatohepatitis; SES, socioeconomic status; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

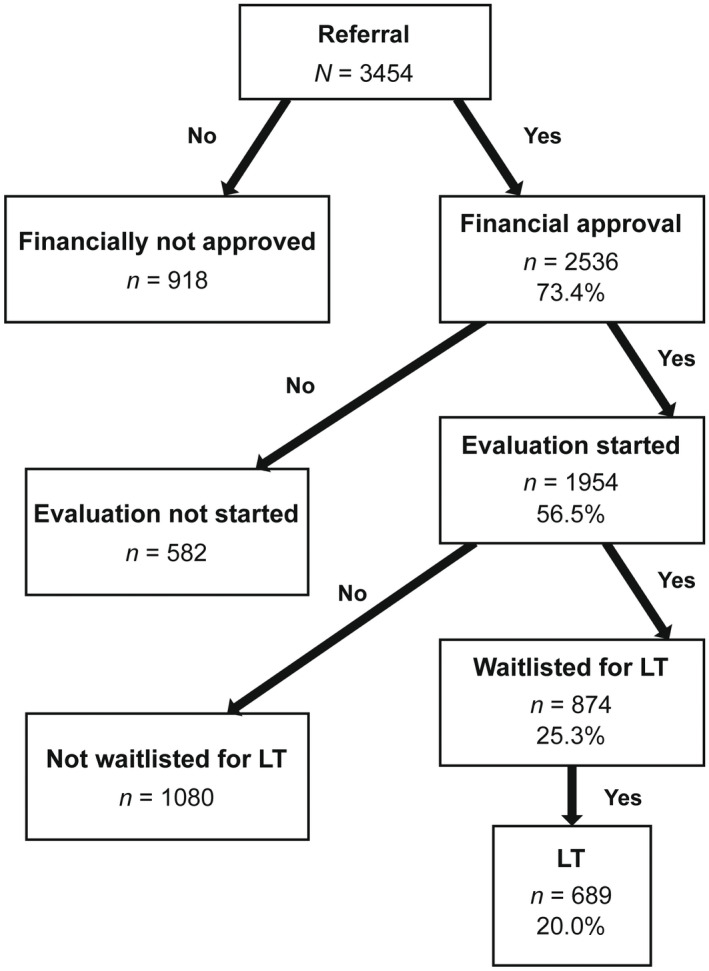

COMPLETION OF STEPS IN THE LIVER TRANSPLANTATION CASCADE

Of the 3454 patients referred for LT, 73.4% received financial approval for LT (Figure 2). Of those referred for LT, 56.5% had an evaluation started, 25.3% were waitlisted for LT, and 20.0% underwent LT (Figure 2). Of those patients who had an evaluation started, 44.8% were waitlisted for LT and 35.3% underwent LT.

FIGURE 2.

LT evaluation cascade. The proportion of patients referred who completed each step in the cascade.

The median time from evaluation start to LT waitlisting was 133 days. This varied by race (White, 130.5 days; Black, 187 days; Other, 105.5 days; p = 0.01) insurance type (private insurance, 113.5 days; Medicaid, 149 days; Medicare, 138 days; p < 0.001), and Cash SNAP assistance (quartile 1 = 121 days; quartile 2 = 127 days; quartile 3 = 143 days; quartile 4 = 148 days; p = 0.01), but not by gender (men, 131 days vs. women, 134 days; p = 0.69) or neighborhood poverty quartile (quartile 1 = 131 days; quartile 2 = 125 days; quartile 3 = 136.5 days; quartile 4 = 144 days; p = 0.11).

We evaluated the proportion of patients that completed each step of the LT evaluation cascade by race, gender, insurance status, rural–urban residence, and neighborhood SES (Table 2). There were no significant differences in the proportion of each of these population who obtained financial approval (73.0%–81.1%) or had an LT evaluation started (56.4%–64.5%) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Clinical characteristics and neighborhood socioeconomic indicators of patients as they progress through the steps of the LT care cascade from referral to transplantation

| All referred (N = 3454) | Financial approval (financial approval/referred; N = 2536) | Evaluation start (evaluation start/referred; N = 1954) | Waitlisted (waitlisted/referred; N = 874) | Transplanted (transplanted/referred; N = 689) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 55.4 (11.2) | 55.8 (10.7) | 55.4 (10.3) | 55.0 (10.6) | 54.7 (10.6) |

| Race (N = 3260) | |||||

| White | 3007 | 2287 (76.1) | 1770 (58.9) | 796 (26.5) | 633 (21.1) |

| Black | 190 | 146 (76.8) | 113 (59.5) | 45 (23.7) | 34 (17.9) |

| Other | 63 | 49 (77.8) | 44 (69.8) | 26 (41.3) | 16 (25.4) |

| Sex (N = 3447) | |||||

| Men | 2112 | 1549 (73.3) | 1208 (57.2) | 554 (26.2) | 452 (21.4) |

| Women | 1335 | 987 (73.9) | 742 (55.6) | 320 (24.0) | 237 (17.8) |

| Diagnosis (N = 3356) | |||||

| HCV | 1017 | 773 (76.0) | 625 (61.5) | 232 (22.8) | 185 (18.2) |

| ALD | 739 | 564 (76.3) | 421 (57.0) | 167 (22.6) | 138 (18.7) |

| NASH | 702 | 543 (77.4) | 427 (60.8) | 215 (30.6) | 167 (23.8) |

| AIH | 133 | 91 (68.4) | 71 (53.4) | 40 (30.1) | 32 (24.1) |

| Cholestatic liver diseases | 230 | 174 (75.7) | 152 (66.1) | 108 (47.0) | 89 (38.7) |

| HBV | 60 | 47 (78.3) | 30 (50.0) | 15 (25.0) | 10 (16.7) |

| Other | 475 | 305 (64.2) | 209 (44.0) | 95 (20.0) | 68 (14.3) |

| HCC (N = 3454) | |||||

| Yes | 618 | 479 (77.5) | 409 (66.2) | 195 (31.6) | 157 (25.4) |

| No | 2836 | 2057 (72.5) | 1531 (54.3) | 679 (23.9) | 532 (18.8) |

| MELD (N = 2718) | 15 (11–20) | 15 (11–19) | 15 (12–19) | 16 (12–20) | 16 (13–20) |

| Insurance type (N = 3131) | |||||

| Private | 933 | 752 (80.6) | 602 (64.5) | 320 (34.3) | 263 (28.2) |

| Medicare | 921 | 741 (80.5) | 547 (59.4) | 288 (22.5) | 192 (20.9) |

| Medicaid | 1277 | 1036 (81.1) | 784 (61.4) | 258 (22.6) | 229 (17.9) |

| Rural designation (N = 3335) | |||||

| Urban | 2918 | 2182 (74.8) | 1678 (57.5) | 757 (26.0) | 594 (20.4) |

| Rural | 417 | 315 (75.5) | 235 (56.4) | 99 (23.4) | 81 (19.4) |

| Neighborhood social determinants | |||||

| Income below poverty (N = 3335) | 13.8 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 12.5 | 12.7 |

| Income below poverty quartiles (% in neighborhood with income below poverty; N = 3335) | |||||

| Q1 (4.3) | 840 | 618 (73.6) | 460 (54.8) | 249 (29.6) | 196 (23.3) |

| Q2 (8.9) | 828 | 638 (77.1) | 493 (59.5) | 231 (27.9) | 175 (21.1) |

| Q3 (15.0) | 843 | 623 (73.9) | 490 (58.1) | 208 (24.7) | 164 (19.5) |

| Q4 (27.1) | 824 | 618 (75) | 470 (57.0) | 168 (20.4) | 140 (17.0) |

| Education less than high school (N = 3335) | 5.2 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 4.9 | 5.0 |

| Education less than high school quartiles (% in neighborhood with education less than high school; N = 3335) | |||||

| Q1 (1.5) | 836 | 615 (24.6) | 463 (55.4) | 250 (30.0) | 196 (23.4) |

| Q2 (3.3) | 842 | 615 (73.0) | 477 (56.7) | 210 (25.0) | 159 (18.9) |

| Q3 (5.6) | 831 | 633 (76.2) | 483 (58.1) | 207 ((25.0) | 168 (20.2) |

| Q4 (10.6) | 826 | 634 (76.8) | 490 (59.2) | 189 (22.9) | 152 (18.4) |

| Cash SNAP assistance (N = 3335) | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 4.1 | 4.2 |

| Cash SNAP assistance quartiles (% in neighborhood with Cash SNAP assistance; N = 3335) | |||||

| Q1 (1.0) | 834 | 625 (74.9) | 468 (56.1) | 253 (30.3) | 194 (23.3) |

| Q2 (2.8) | 836 | 628 (75.1) | 497 (59.5) | 246 (29.4) | 194 (23.2) |

| Q3 (5.2) | 855 | 652 (76.3) | 524 (61.3) | 204 (23.9) | 156 (18.3) |

| Q4 (10.2) | 810 | 592 (73.1) | 424 (52.3) | 153 (18.9) | 131 (16.2) |

| Medicaid (N = 3335) | 18.1 | 18.1 | 18.0 | 9.9 | 16.8 |

| Medicaid quartiles (% in neighborhood with Medicaid; N = 3335) | |||||

| Q1 (6.6) | 834 | 620 (24.8) | 464 (55.6) | 252 (30.2) | 201 (24.1) |

| Q2 (13.1) | 841 | 631 (75.0) | 498 (59.2) | 222 (26.4) | 168 (20.0) |

| Q3 (20.3) | 840 | 638 (76.0) | 494 (58.8) | 222 (26.4) | 174 (20.7) |

| Q4 (32.5) | 820 | 608 (74.2) | 457 (55.7) | 160 (19.5) | 132 (16.1) |

Note: Bolded variables represent significant differences among vulnerable populations in the proportion referred for LT who completed each step. Data are presented as mean (SD), n (%), median (range), %, or n.

The column N provides total number referred while the row N provides the number referred for whom there was complete data. Note that the missigness for those who had an evaluation completed was less than 30 for all variables except alcohol biomarkers and marital status.

Abbreviations: AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ALD, alcohol‐related liver disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; LT, liver transplantation; MELD, Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease; NASH, nonalcohol‐related steatohepatitis; SD, standard deviation; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

However, there were significant differences in the proportion of patients from these vulnerable populations who were waitlisted for LT. The proportion of patients of other races who were referred and ultimately waitlisted for LT was 41.3% compared with 23.7% of Black patients and 26.5% of White patients (p = 0.02); there was no significant difference between Black and White patients referred and ultimately waitlisted (p = 0.34). Higher proportions of privately insured patients (34.3%) referred for LT were waitlisted compared with patients with Medicare (22.5%) and Medicaid (22.6%; p < 0.001). Fewer patients living in neighborhoods with high poverty (quartile 4 20.4% vs. quartile 1 29.6%; p < 0.01), higher proportions of residents with education less than high school (quartile 4 22.9% vs. quartile 1 30.0%, p = 0.01), higher proportions of residents with Cash SNAP assistance (quartile 4 18.9% vs. quartile 1 30.3%, p < 0.001), and higher proportions of residents with Medicaid insurance (quartile 4 19.5% vs. quartile 1 30.2%, p < 0.01) were waitlisted for LT (Table 2).

There were no differences in financial approval, evaluation start, and waitlisting between men and women. However, fewer women who were waitlisted ultimately underwent LT compared with men (17.8% vs. 21.4%, p = 0.01) (Table 2). There also was no difference in completion of the steps in the LT evaluation cascade between those living in rural and urban areas (Table 2).

Only 20% of patients referred underwent LT (Figure 2). There were three groups of patients, who prior to waitlisting, failed to progress through the cascade: (1) those who were referred and did not get financial approval, (2) those who received financial approval and did not have an LT evaluation started, and (3) those who had an evaluation started but were not waitlisted for LT (Figure 2).

Referred for LT but did not receive financial approval

There were 918 patients referred for LT who did not get financial approval for LT (Figure 2). They were on average 54.3 ± 12.5 years old; 23.9% of White patients who were evaluated were not listed compared with 23.2% of Black patients and 22.2% of other race (p = 0.93). There were no differences by gender (men 26.7% and women 26.1%; p = 0.70), insurance type (private 19.4%, Medicaid 18.9%, Medicare 19.5%; p = 0.91), rural or urban residence (urban 25.2%, rural 24.5%), or by neighborhood poverty quartile (quartile 1 26.4% vs. quartile 4 25.0%; p = 0.89) between those who were referred and received financial approval and those who did not.

Received financial approval but LT evaluation not started

Of 2536 patients who received financial approval, 582 were not evaluated for LT (Figure 2). Patients who had financial approval but did not have an LT evaluation started were an average of 56.4 ± 11.1 years old. There were no differences by race (White, 27.8%; Black, 26.1%; Other 20.0% ; p = 0.41), gender (men, 27.6%; women, 29.5%; p = 0.29), insurance type (private, 25.9%; Medicaid, 28.9%; and Medicare, 30.3%; p = 0.13), rural or urban residence (urban, 28.0%; rural 30.4%), or neighborhood poverty quartile (quartile 1 25.6% vs. quartile 4 24.3%; p = 0.89) between those who had financial approval and were evaluated and those who were not evaluated for LT. Patients who had financial approval and did not have an evaluation started were more likely to have positive alcohol biomarkers (3.6% vs. 6.4%; p = 0.03) and more likely to be single or divorced (40.5% vs. 53.9%; p < 0.001).

Evaluation started but failed to be waitlisted

Of 1954 patients who started LT evaluation, 874 were waitlisted for LT and 1080 exited the LT evaluation cascade prior to waitlisting (Figure 2).

Patients who were not waitlisted after starting an evaluation were an average of 55.9 ± 10.1 years old. About 61.1% of Black patients who were evaluated were not listed, compared with 55.2% of White patients, and 40.9% of other race (p = 0.07). The proportions of men (54.3%) and women (57.1%) who failed to be waitlisted were similar (p = 0.22). The proportion of Medicaid patients (63.4%) who failed to be waitlisted was significantly higher than in those with private (47.2%) and Medicare (53.0%) insurance types (p < 0.001). Patients living in neighborhoods with higher proportions of poverty (64.3% vs. 46.3%; p < 0.01), higher proportions of residents with education less than high school (61.4% vs. 46.4%; p = 0.01), higher proportions of residents with using Cash SNAP assistance (64.2% vs. 46.4%; p < 0.001), and higher proportions of residents with Medicaid (64.7% vs. 46.1%; p < 0.01) failed to be waitlisted.

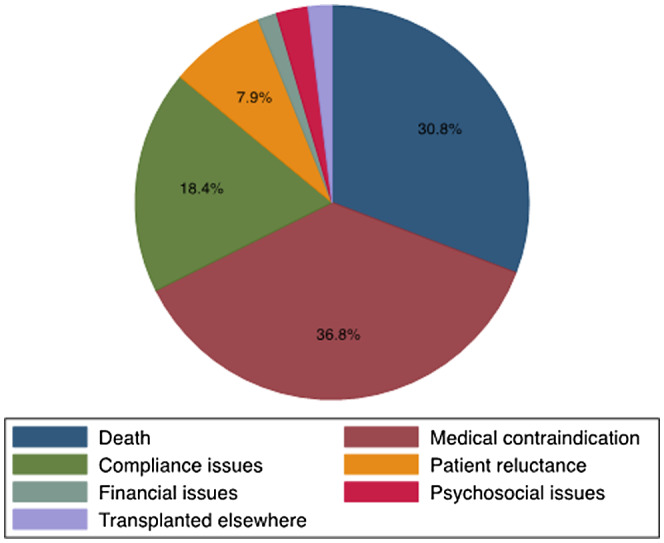

Reasons for failure to be waitlistedwere evaluated. The most common reason for starting an evaluation but failing to be waitlisted was medical contraindication (36.8%), followed by death (30.8%) and issues with compliance 18.4% (Figure 3). These remained the top three reasons for failure to be waitlisted when explored by race, gender, and rural/urban residence.

FIGURE 3.

Reasons for failure to complete LT evaluation (N = 1080). Reasons for failing to complete the LT evaluation in patients who started an evaluation but did not complete the evaluation.

Predictors of waitlisting for LT evaluation

Disparities in the evaluation cascade were identified at the waitlisting step. Predictors of waitlisting were evaluated using multivariable logistic regression models that included age, gender, race, MELD at referral, etiology of liver disease, Charlson Comorbidity Index, HCC diagnosis, individual insurance type, rural versus urban residence, alcohol biomarker positivity, and marital status. There were complete variables on 1531 of the 1954 patients who were evaluated for LT and included in the final model. Neighborhood‐level Medicaid was colinear with neighborhood poverty (Pearson 0.82) and Cash SNAP assistance was also colinear with neighborhood poverty (Pearson 0.80), so they were excluded from the final model. Neighborhood educational attainment was not collinear with neighborhood poverty (Pearson 0.61), so it was included in the final model. There was no correlation between race and any of the neighborhood SES indicators or individual insurance type (Pearson r 0.07–0.14). Being from a high‐poverty neighborhood compared with a lower‐poverty neighborhood (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.38–0.82) and being personally insured by Medicaid (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.58–0.99) were associated with failure to be waitlisted (Table 3). Increasing age and MELD score were also associated with failure to be waitlisted (Table 3). The results from the competing risk analysis were similar to the logistic regression analysis (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Predictors of LT waitlisting (N = 1531)

| Logistic regression | Competing risk | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | SHR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age at referral | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.01 | 0.98 (0.98–0.99) | 0.003 |

| Femalegender | 0.82 (0.65–1.03) | 0.10 | 0.86 (0.74–1.01) | 0.10 |

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | Reference | ||

| Black | 1.12 (0.69–1.81) | 0.65 | 0.94 (0.68–1.28) | 0.68 |

| Other | 1.15 (0.49–2.74) | 0.78 | 1.19 (0.74–1.91) | 0.47 |

| MELD score | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | <0.001 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.01 (0.96–1.05) | 0.78 | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 0.43 |

| Rural geography | 0.85 (0.63–1.16) | 0.32 | 0.86 (0.69–1.06) | 0.16 |

| Insurance type | ||||

| Private | Reference | Reference | ||

| Medicaid | 0.76 (0.58–0.99) | 0.04 | 0.69 (0.57–0.83) | <0.001 |

| Medicare | 1.00 (0.75–1.34) | 0.99 | 0.88 (0.73–1.07) | 0.20 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| HCV | Reference | Reference | ||

| ALD | 1.06 (0.77–1.46) | 0.72 | 0.99 (0.79–1.26) | 0.98 |

| NASH | 2.03 (1.47–2.80) | <0.001 | 1.47 (1.19–1.82) | <0.001 |

| AIH | 1.77 (0.97–3.21) | 0.06 | 1.95 (1.30–2.91) | 0.001 |

| Cholestatic liver diseases | 3.49 (2.18–5.59) | <0.001 | 2.15 (1.63–2.83) | <0.001 |

| HBV | 2.04 (0.76–5.49) | 0.16 | 1.86 (1.02–3.40) | 0.04 |

| Other | 1.35 (0.90–2.04) | 0.15 | 1.23 (0.99–1.70) | 0.06 |

| HCC diagnosis | 0.50 (0.37–0.67) | <0.001 | 0.65 (0.54–0.79) | <0.001 |

| Education less than high school quartiles | ||||

| Q1 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Q2 | 0.80 (0.57–1.12) | 0.20 | 0.85 (0.69–1.04) | 0.12 |

| Q3 | 0.87 (0.62–1.22) | 0.44 | 0.95 (0.76–1.19) | 0.66 |

| Q4 | 0.85 (0.60–1.21) | 0.37 | 0.95 (0.74–1.22) | 0.68 |

| Income below poverty quartiles | ||||

| Q1 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Q2 | 0.87 (0.64–1.20) | 0.40 | 0.93 (0.76–1.14) | 0.48 |

| Q3 | 0.81 (0.57–1.15) | 0.25 | 0.83 (0.66–1.04) | 0.10 |

| Q4 | 0.56 (0.38–0.82) | 0.003 | 0.66 (0.51–0.85) | 0.002 |

| Alcohol biomarkers positive | 0.66 (0.39–1.10) | 0.11 | 0.84 (0.56–1.25) | 0.39 |

| Marital status single | 0.78 (0.62–0.99) | 0.06 | 0.86 (0.73–1.01) | 0.06 |

The column N provides total number referred while the row N provides the number referred for whom there was complete data. Note that the missigness for those who had an evaluation completed was less than 30 for all variables except alcohol biomarkers and marital status.

Abbreviations: AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ALD, alcohol‐related liver disease; CI, confidence interval; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; LT, liver transplantation; MELD, Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease; NASH, nonalcohol‐associated steatohepatitis; OR, odds ratio; SHR, subdistribution hazard ratio.

Predictors of death during LT evaluation

Of the 1954 patients who started an LT evaluation, 447 died during evaluation (22.3%); there were complete variables on 1759 patients included in the model. Cox proportional hazards for survival as predicted by the adjusted model are detailed in Table 4. Patients from high‐poverty compared with lower‐poverty neighborhoods were significantly more likely to die during LT evaluation (HR 1.49, 95% CI 1.09–2.05). Patients with rural residence were less likely to die during LT evaluation than those from urban residence (HR 0.71, 95% 0.51–0.99). Increasing age and MELD score were associated with death during LT evaluation (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards model of predictors of death during LT evaluation (N = 1759)

| HR (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at referral | 1.02 (1.00–1.03) | 0.01 |

| Female gender | 0.97 (0.77–1.22) | 0.82 |

| Race | ||

| White | Reference | |

| Black | 0.69 (0.45–1.04) | 0.08 |

| Other | 0.72 (0.33–1.56) | 0.41 |

| MELD score | 1.08 (1.06–1.010) | <0.001 |

| Rural geography | 0.71 (0.50–0.99) | 0.045 |

| Insurance type | ||

| Medicaid | Reference | |

| Private | 1.09 (0.85–1.42) | 0.49 |

| Medicare | 0.80 (0.61–1.03) | 0.09 |

| Diagnosis | ||

| HCV | Reference | |

| ALD | 0.66 (0.50–0.89) | <0.001 |

| NASH | 0.82 (0.62–1.10) | 0.12 |

| AIH | 0.37 (0.14–0.94) | 0.04 |

| Cholestatic liver diseases | 0.30 (0.15–0.63) | <0.001 |

| HBV | 1.20 (0.62–2.3) | 0.59 |

| Other | 1.20 (0.83–1.75) | 0.32 |

| HCC diagnosis | 1.11 (0.85–1.44) | 0.77 |

| Income below poverty quartiles | ||

| Q1 | Reference | |

| Q2 | 1.24 (0.89–1.71) | 0.20 |

| Q3 | 1.28 (0.91–1.79) | 0.14 |

| Q4 | 1.49 (1.09–2.05) | 0.01 |

| Alcohol biomarkers positive | 057 (0.30–1.10) | 0.09 |

The column N provides total number referred while the row N provides the number referred for whom there was complete data. Note that the missigness for those who had an evaluation completed was less than 30 for all variables except alcohol biomarkers and marital status.

Abbreviations: AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ALD, alcohol‐related liver disease; CI, confidence interval; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HR, hazard ratio; LT, liver transplantation; MELD, Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease; NASH, nonalcohol‐associated steatohepatitis.

Because neighborhood poverty was associated with death during LT evaluation, we explored the cohort that began an LT evaluation further by this SES indicator. Compared with quartile 1, patients in quartile 4 were younger (quartile 4 54.8 years old vs. quartile 1 55.3 years old), more likely to be Black race (quartile 1 3.9% vs. quartile 4 14.2%; p < 0.001), more likely to be insured by Medicaid (quartile 1 31.7% vs. quartile 4 54.6%), and more likely to be single (quartile 1 37.6% vs. quartile 4 54.5%). Residents in quartile 4 had more underlying HCV than those in quartile 1, with similar MELD and Charlson Comorbidity Index at presentation (Table 5). There were no significant differences by neighborhood poverty quartile for reasons for failure to complete LT evaluation. The leading reasons remained death, medical contraindication, and issues with compliance (Table S1).

TABLE 5.

Cohort characteristics by neighborhood poverty quartile

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 55.3 | 55.4 | 56.0 | 54.8 | 0.02 |

| Female gender | 36.9 | 37.3 | 42.7 | 39.2 | 0.06 |

| Race | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 93.4 | 96.6 | 95.1 | 83.7 | |

| Black | 3.9 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 14.2 | |

| Other | 2.7 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2.2 | |

| MELD score | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 0.31 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 6.6 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 7.1 | 0.51 |

| Rural geography | 3.8 | 15.7 | 25.0 | 5.3 | <0.001 |

| Insurance type | |||||

| Private | 38.3 | 33.9 | 25.1 | 20.3 | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 31.7 | 35.5 | 43.1 | 54.6 | |

| Medicare | 30.0 | 30.6 | 31.4 | 25.1 | |

| Diagnosis | <0.001 | ||||

| HCV | 24.3 | 26.5 | 30.0 | 39.2 | |

| ALD | 23.6 | 23.3 | 21.9 | 20.6 | |

| NASH | 21.2 | 23.4 | 21.1 | 17.5 | |

| AIH | 3.8 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 4.4 | |

| Cholestatic liver diseases | 8.6 | 7.3 | 6.1 | 5.1 | |

| HBV | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.9 | |

| Other | 16.0 | 13.4 | 15.1 | 11.5 | |

| HCC diagnosis | 17.1 | 16.1 | 17.7 | 20.8 | 0.08 |

| Alcohol biomarkers positive | 4.9 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 5.4 | 0.32 |

| Marital status single | 37.6 | 39.4 | 43.7 | 54.5 | <0.001 |

The column N provides total number referred while the row N provides the number referred for whom there was complete data. Note that the missigness for those who had an evaluation completed was less than 30 for all variables except alcohol biomarkers and marital status.

Abbreviations: AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ALD, alcohol‐related liver disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; MELD, Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease; NASH, nonalcohol‐related steatohepatitis.

DISCUSSION

The utilization of MELD in the allocation of organs for LT has allowed for an objective prioritization of sicker patients and improved waitlist mortality.[ 18 ] Despite this, disparities in access to LT for vulnerable populations remain. In this study, we sought to evaluate the role that race, gender, individual insurance status, rural versus urban residence, and neighborhood SES indicators play on LT waitlisting and death during LT evaluation. Our findings demonstrate that in this cohort, there are barriers in access along the care cascade, with the majority beginning after LT evaluation has started. Importantly, neighborhood poverty was independently associated with a failure to be waitlisted and death during LT evaluation.

In patients who were referred for LT, we saw no racial, gender, rural/urban, or neighborhood SES disparities in financial approval for LT evaluation or evaluation start after being seen by a transplantation hepatologist. While there were no disparities seen in financial approval in this cohort, it is possible that there was significant pre‐screening for appropriate insurance by referring providers prior to LT referral. In this cohort, there were no disparities in starting an evaluation for LT for vulnerable populations, suggesting less of a role for provider bias at this step in the cascade. However, there are some important caveats. Only 5.9% of the population referred for LT was Black, while Black residents make up 9.9% of the Indiana population, suggesting there could be bias earlier in the process. In addition, those who had financial approval but failed to have an evaluation started were more likely to have positive alcohol biomarkers and more likely to be unmarried/single/widowed, suggesting that this population had a higher burden of risk factors and social needs in health (alcohol use and potential issues with social support) that were unable to be met to help them get to the evaluation step. Finally, evaluation completion time varied significantly by race, individual insurance type, and neighborhood SES and likely contributed to poor outcomes.[ 19 ] Once patients were waitlisted for LT, only disparities by sex were observed in LT. This finding is consistent with the gender/sex disparity in LT that has long been recognized and thought to be due in part to donor–recipient size mismatch and limitations in the ability of creatinine and therefore MELD score to accurately predict renal function in women.[ 3 ]

The disparities seen in our descriptive analysis began at the waitlisting step, where neighborhood SES and individual insurance were associated with a failure to be waitlisted. This was confirmed on multivariable analysis where neighborhood poverty and being insured by Medicaid were independently associated with a failure to be waitlisted. In the study by Bryce et al.,[ 6 ] in a cohort from 1994 to 2001, Black patients, those who lacked commercial insurance, and women were less likely to undergo LT evaluation waitlisting and transplantation. In a more recent study, the authors found that Black race was associated with a 26% lower odds of being waitlisted for LT.[ 7 ] This is the first study to our knowledge to explore neighborhood SES indicators and waitlisting. We did not see lower rates of waitlisting in our Black cohort of patients. This likely reflects nuanced practice patterns by institution and perhaps our small sample size, warranting a larger multicenter study on this topic.

Importantly, we found that neighborhood poverty, independent of MELD score, was associated with death during LT evaluation. Neighborhood social determinants—particularly lower SES quartile—have been previously associated with a decreased odds of waitlisting and poor posttransplantation outcomes in solid organ transplantations.[ 20 , 21 ] These associations are important because this information is readily available on referral and could be used to identify patients at risk for poor outcomes before patients even arrive at our transplantation centers. Furthermore, these data contribute to our understanding of a more complete model of health.

There was an association between urban residence and death during LT evaluation. In solid organ transplantation, much of the focus has been on disparities in referral and transplantation for rural patients.[ 12 , 22 , 23 ] However, our study is the first to our knowledge to look at the risk of urbanicity on death during the complex LT evaluation process. Strategies are needed to help the highest risk cohorts navigate this process effectively.

Finally, while death was the leading reason for failure to complete LT evaluation, it was notable that many patients did not complete evaluation due to issues with adherence. Adherence to the medical plan of care is necessary to ensure a good post‐LT outcome. However, the lack of adherence is complex and may be the result of a fear, cost, failed doctor–patient relationships, lack of medical literacy, and mistrust, and warrants further study in LT care.[ 24 ]

Our study's strengths are that it explores a large cohort of LT patients through multiple steps in the LT cascade. We used readily available address and zip code information to identify at‐risk populations. Finally, our center is the only transplantation center in the state; thus, it is likely we captured the population of interest at a higher rate than in multicenter states. While our study provides important new data, it is a single‐center experience. Patterns may differ across the country, and therefore, further study is warranted. In addition, we did not explore referral and our referral populations did not reflect the proportion of minorities or rural residents in our state. We also did not have information about the causes of death for the patients within our cohort. As this is an ESLD population, we believe the reasons for death were likely liver related. Furthermore, there were no differences in Charlson score by neighborhood poverty, making nonliver‐related mortality differences less likely. Our analysis was retrospective, so while we could clearly identify who started an LT evaluation and who was waitlisted for LT, our database did not a priori define the step of evaluation completion in patients who were not waitlisted. Finally, our analysis did not attempt to control for any changes in allocation over the study period.

In conclusion, the social determinants of health and social needs in health are associated with progression through the LT care cascade. More specifically, neighborhood poverty is associated with a failure to be waitlisted and ultimately death during LT evaluation. Multicenter studies are needed to better understand barriers to completing waitlisting for this group so that death during LT can be avoided. Interventions including expedited LT evaluation pathways and navigation programs need to be studied in this vulnerable population.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Marwan Ghabril is on the Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) for PTC Therapeutics, BioCryst, and CymaBay.

Supporting information

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Open access funding enabled and organized by ProjektDEAL.

Mohamed KA, Ghabril M, Desai A, Orman E, Patidar KR, Holden J, et al. Neighborhood poverty is associated with failure to be waitlisted and death during liver transplantation evaluation. Liver Transpl. 2022;28:1441–1453. 10.1002/lt.26473

SEE EDITORIAL ON PAGE 1421

REFERENCES

- 1. Moon AM, Singal AG, Tapper EB. Contemporary epidemiology of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;18:2650–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nguyen GC, Thuluvath PJ. Racial disparity in liver disease: biological, cultural, or socioeconomic factors. Hepatology. 2008;47:1058–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nephew LD, Serper M. Racial, gender, and socioeconomic disparities in liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2021;27:900–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rosenblatt R, Wahid N, Halazun KJ, Kaplan A, Jesudian A, Lucero C, et al. Black patients have unequal access to listing for liver transplantation in the United States. Hepatology. 2021;74:1523–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gehlert S, Mozersky J. Seeing beyond the margins: challenges to informed inclusion of vulnerable populations in research. J Law Med Ethics. 2018;46:30–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bryce CL, Angus DC, Arnold RM, Chang CCH, Farrell MH, Manzarbeitia C, et al. Sociodemographic differences in early access to liver transplantation services. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2092–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jesse MT, Abouljoud M, Goldstein ED, Rebhan N, Ho CX, Macaulay T, et al. Racial disparities in patient selection for liver transplantation: an ongoing challenge. Clin Transplant. 2019;33:e13714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. J CBaA . Meeting individual social needs falls short of addressing Social Determinants of Health. Health Affairs Blog; 2019. [cited 2022 Jan]. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20190115.234942/full/ [Google Scholar]

- 9. Williams DR, Costa MV, Odunlami AO, Mohammed SA. Moving upstream: how interventions that address the social determinants of health can improve health and reduce disparities. J Public Health Manag Pract 2008;14(Suppl):S8–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. US Census Bureau . American Community. Five‐Year Trends Available for Median Household Income, Poverty Rates and Computer and Internet UseSurvey. Available from: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press‐releases/2018/2013‐2017‐acs‐5year.html

- 11. US Department of Agriculture . Economic Research Services, Rural‐Urban Commuting Codes. Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data‐products/rural‐urban‐commuting‐area‐codes/

- 12. Axelrod DA, Guidinger MK, Finlayson S, Schaubel DE, Goodman DC, Chobanian M, et al. Rates of solid‐organ wait‐listing, transplantation, and survival among residents of rural and urban areas. JAMA. 2008;299:202–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Singh GK. Area deprivation and widening inequalities in US mortality, 1969–1998. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1137–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Butler DC, Petterson S, Phillips RL, Bazemore AW. Measures of social deprivation that predict health care access and need within a rational area of primary care service delivery. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(Pt 1):539–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alcaraz KI, Wiedt TL, Daniels EC, Yabroff KR, Guerra CE, Wender RC. Understanding and addressing social determinants to advance cancer health equity in the United States: a blueprint for practice, research, and policy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rogers W. Regression standard errors in clustered samples. StataCorp LP, College Station; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cholongitas E, Marelli L, Shusang V, Senzolo M, Rolles K, Patch D, et al. A systematic review of the performance of the model for end‐stage liver disease (MELD) in the setting of liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1049–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. US Census Bureau . Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/IN2019

- 20. Wayda B, Clemons A, Givens RC, Takeda K, Takayama H, Latif F, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in adherence and outcomes after heart transplant: a UNOS (united network for organ sharing) registry analysis. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11:e004173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Patzer RE, Amaral S, Wasse H, Volkova N, Kleinbaum D, McClellan WM. Neighborhood poverty and racial disparities in kidney transplant waitlisting. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1333–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O'Hare AM, Johansen KL, Rodriguez RA. Dialysis and kidney transplantation among patients living in rural areas of the United States. Kidney Int. 2006;69:343–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ross KH, Patzer RE, Goldberg D, Osborne NH, Lynch RJ. Rural‐urban differences in in‐hospital mortality among admissions for end‐stage liver disease in the United States. Liver Transpl. 2019;25:1321–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gast A, Mathes T. Medication adherence influencing factors—an (updated) overview of systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2019;8:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1