Abstract

We conducted a systematic review to assess outcomes in Hispanic donors and explore how Hispanic ethnicity was characterized. We searched PubMed, EMBASE, and Scopus through October 2021. Two reviewers independently screened study titles, abstracts, and full texts; they also qualitatively synthesized results and independently assessed quality of included studies. Eighteen studies met our inclusion criteria. Study sample sizes ranged from 4007 to 143,750 donors and mean age ranged from 37 to 54 years. Maximum follow‐up time of studies varied from a perioperative donor nephrectomy period to 30 years post‐donation. Hispanic donors ranged between 6% and 21% of the donor populations across studies. Most studies reported Hispanic ethnicity under race or a combined race and ethnicity category. Compared to non‐Hispanic White donors, Hispanic donors were not at increased risk for post‐donation mortality, end‐stage kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, non‐pregnancy‐related hospitalizations, or overall perioperative surgical complications. Compared to non‐Hispanic White donors, most studies showed Hispanic donors were at higher risk for diabetes mellitus following nephrectomy; however, mixed findings were seen regarding the risk for post‐donation chronic kidney disease and hypertension. Future studies should evaluate cultural, socioeconomic, and geographic differences within the heterogeneous Hispanic donor population, which may further explain variation in health outcomes.

Keywords: clinical research/practice, disparities, donors and donation, donors and donation: donor follow‐up, donors and donation: living, health services and outcomes research, kidney transplantation/nephrology, kidney transplantation: living donor

Short abstract

Hispanic compared to non‐Hispanic living kidney donors are not at increased risk for post‐donation mortality, end‐stage kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, non‐pregnancy‐related hospitalizations, or perioperative surgical complications, but are at higher risk of post‐donation diabetes.

Abbreviations

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- ESKD

end‐stage kidney disease

- GN

glomerulonephritis

- HCUP‐NIS

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Nationwide Inpatient Sample

- HTN

hypertension

- LDKT

living donor kidney transplantation

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplant

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

1. INTRODUCTION

The Hispanic population is the largest and one of the fasting growing minority groups in the United States, with over 62 million people identifying as Hispanic or Latino in 2020. 1 The terms “Hispanic” or “Latino” have been used to describe a population with a shared cultural heritage, and frequently a common language, but do not refer to race or ancestry. 2 Initially, the term “Hispanic” was propagated following efforts in the 1970s calling for the federal government to collect data on the Hispanic population. 3 In 1980, a “Hispanic” category was added to the Census to identify US residents of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Central American, South American, and other Spanish‐speaking country origins; this single term was later replaced by the interchangeable use of “Hispanic or Latino” in 1997. 3 , 4 More recently, “Latinx” has been popularized as a more gender‐inclusive term to describe Hispanic ethnicity. 3 Herein we use the term Hispanic for reading ease, although we recognize that individuals may preferentially identify as Hispanic, Latino, Latina, Latinx, or a combination of these categories.

With the ability to collect data on the Hispanic population, research has highlighted numerous health disparities in this group and other minorities with kidney disease. 5 , 6 , 7 For instance, Hispanic individuals have a higher prevalence and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) compared to the general population. 8 , 9 Recent USRDS data demonstrate chronic kidney disease (CKD) prevalence is lower among Hispanic individuals at 11.9% compared to non‐Hispanic White individuals (15.7%). 10 However, Hispanic individuals are 1.3 times more likely to develop end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD) as compared to non‐Hispanic White individuals, 10 and have a higher risk of CKD progression. 11 , 12 , 13 Hispanic persons with ESKD are less likely to undergo living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) as compared to the non‐Hispanic White population in the United States, 14 , 15 and have experienced a decline in biologically related living kidney donors under the age of 50. 16 , 17 Notably, Hispanic donors are the largest racial or ethnic subgroup (40%) among international living kidney donors. 18 National cohort studies following donors have evaluated health outcomes among varying racial or ethnic subgroups; one study showed Hispanic donors experience an increased risk of ESKD compared to White donors, albeit the absolute risk was small. 19 Another study showed that Hispanic donors had a higher risk of hypertension (HTN), drug‐treated DM, and CKD after nephrectomy, as compared to White donors. 20 While recent reviews discuss the risks of living kidney donation across race and ethnicity, 21 , 22 , 23 we were particularly interested in reviewing post‐donation health outcomes among donors that self‐identified as Hispanic, and exploring how studies characterized Hispanic ethnicity.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design and literature search strategy

We performed a systematic review of published, peer‐reviewed original research evaluating post‐donation outcomes in Hispanic individuals. We compared study designs, participant characteristics and evaluated factors that may have compromised validity. Eligible studies evaluated clinical post‐transplant outcomes in Hispanic donors. We included studies that categorized Hispanic donors into a mutually exclusive group or compared Hispanic donors to Hispanic controls.

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, and Scopus through October 2021. An expert clinical informationist (J.B.) and content experts within our team (F.A., C.E.C., and T.S.P.) developed search strategies to identify pertinent studies (Item 1).

2.2. Data extraction, study inclusion, and exclusion criteria

Two reviewers screened study titles and abstracts from initial search results; full texts were subsequently reviewed. We included articles that evaluated post‐donation outcomes in Hispanic living kidney donors who were 18 years of age or older and living in the United States. We excluded abstracts or published manuscripts that did not include original research or if they were not written in English. We hand‐searched bibliographies of articles meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria and three additional review papers 21 , 22 , 23 to identify studies that may have been missed by initial search strategies.

2.3. Data classification and analysis

We decided a priori to not conduct a formal meta‐analysis because we expected studies to be methodologically diverse and focusing on disparate clinical outcomes. Instead, we synthesized results qualitatively within summary tables to compare differences and similarities between studies. Among these comparisons, we have highlighted perspectives of risk among living donors as previously described by Lentine et al. 24 We noted how Hispanic ethnicity was defined in each study.

2.4. Assessment of studies’ quality (internal and external validity for relevant outcomes)

An adapted version of previously published instruments 25 , 26 , 27 was used to independently assess the validity of included studies (Item 2). Regarding internal validity, we evaluated whether studies were at minimal risk for selection bias, used valid outcome assessments, rigorous statistical analyses, and appropriately discussed limitations and potential sources of bias. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to evaluate external validity. Two reviewers independently assessed study quality with a third party available to resolve disagreements.

3. RESULTS

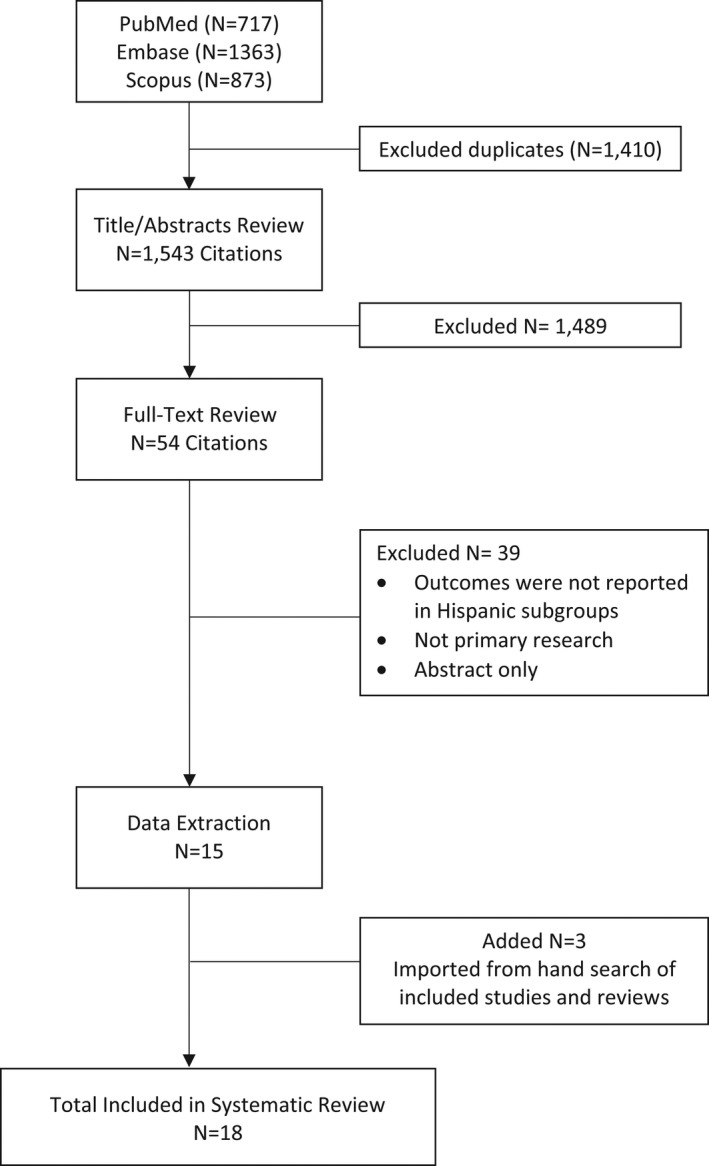

Our search identified 1543 non‐duplicate records (i.e., citations and abstracts), of which 54 were deemed eligible for full‐text review. We retained 15 articles meeting inclusion criteria. From hand‐searching bibliographies of the final 15 articles and 3 review papers, 21 , 22 , 23 we obtained 3 additional articles resulting in the final inclusion of 18 studies 19 , 20 , 24 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 (Figure 1, Table 1). The results in the tables highlight outcomes evaluated among Hispanic donors and respective comparison groups (Tables 2 and 3).

FIGURE 1.

Summary of literature search and article review process

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study | Outcome | Sample size | Data source and study design | Demographics | Socioeconomic status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age | Female sex (%) | Race and ethnicity (%) | Insurance (%) | Education (%) | ||||

| 2010, Friedman | Perioperative complications | 6320 | Cross‐sectional analysis using discharge data (1995–2005) from the HCUP‐NIS, ICD‐9 diagnostic, and procedure codes (1999–2005) from cases of patients undergoing LKD. Mean LOS: 3.3 days | 40 | 59 |

n = 4329 Hispanic: 11 Black: 12 Other▪: 6 White: 68 |

n = 6210 Private: 44 Self‐Pay: 13 Medicare: 13 Medicaid 2 No charge 1 Other: 26 |

NR |

| 2010, Lentine ◊ | CKD, CVD, DM, HTN | 4650 |

Linkage of OPTN data (1987–2007) with administrative billing claims from a private health insurer (2000–2007) CKD outcome evaluated among coding subgroup of 2307 LKDs. Median follow‐up: 7.7 yrs |

37 | 55 |

Hispanic: 8.2 Non‐Hispanic Black: 13.1 Non‐Hispanic White: 76.3 Other▪: 2.4 |

Private: 100 |

n = 3385

<12th grade

|

| 2010, Segev | Mortality | 80 347 | Linkage of OPTN LKD data (1994–2009) and SSDMF. Median follow‐up: 6.3 yrs | 18–39: 49 40–49: 30 50–59: 17 ≥60: 4 | 59 |

n = 80 286 Hispanic: 12.3 Black: 13.1 Other□: 1.6 White: 73.1 |

NR |

n = 41 146 GS: 2 HS: 36 Some college: 28 College graduate: 24 Post‐college: 10 |

| 2011, Lentine ◊ | DM, HTN (accounted for relatedness to recipient) | 4650 | Linkage of OPTN data (1987–2007) with administrative billing claims from a private health insurer (2000–2007) | See Lentine 2010 | ||||

| 2014, Lentine Am J Nephrol ◊ | HTN | 4650 | Linkage of OPTN data (1987–2007) with administrative billing claims from a private health insurer (2000–2007), specifically using pharmacy fills | See Lentine 2010 | ||||

| 2014, Lentine Transp. | CKD, DM, HTN | 4007 | Linkage of OPTN data (1987–2008) with Medicare‐insured living donors. Median follow‐up: 6 yrs | 55 | 60 |

Hispanic: 5.7 Non‐Hispanic Black: 8.1 Non‐Hispanic White: 83.4 Other▪: 2.8 |

Medicare: 100 | NR |

| 2014, Muzaale | ESKD | 96 217 | Linkage of OPTN LKD data (1994–2011) and national kidney replacement treatment records. Healthy controls from NHANES III (screened for health exclusions to donation, matched by demographic and clinical factors) LKD. Median follow‐up: 7.6 yrs | 40 | 59 |

Hispanic: 12.5 Black: 12.9 White/other □: 74.6 |

NR |

HS or less: 36 Some college: 28 College graduate: 25 Post college: 10 |

| 2014, Schold | Rehospitalization | 4524 | Retrospective cohort using State Inpatient Databases compiled by AHRQ. Data from North Carolina, New York, Florida, California. Follow‐up: 731 days | 41 | n = 386160 |

n = 3395 Hispanic: 21 Black: 10 White: 63 |

NR | NR |

| 2015, Lam ◊ | Gout | 4650 | Linkage of OPTN data (1987–2007) with administrative billing claims from a private health insurer (2000–2007) | See Lentine 2010 | ||||

| 2015, Lentine ◊ |

Proteinuria Nephrotic syndrome Nephritis/nephropathy Renal failure, any kidney diagnosis, CKD (accounting for relatedness) |

4650 | Linkage of OPTN data (1987–2007) with administrative billing claims from a private health insurer (2000–2007) | See Lentine 2010 | ||||

| 2016, Anjum |

ESKD, early (0–9 yrs), and late (10–25 yrs) post‐donation by subtype:

|

125 427 | Linkage of OPTN data (1987–2014) and national kidney replacement treatment records. Median follow‐up: 11 yrs | 40 | 59 |

Hispanic: 12 Black: 13 White or other▪: 75 |

NR |

HS or less: 35 Attended college: 28 Graduate or more: 37 |

| 2016, Lentine | Perioperative complications | 14 964 | Linkage of OPTN data (2008–2012) with UHC database, an alliance of 107 academic medical centers and 234 of affiliated hospitals. Follow‐up: perioperative period | 42 | 62 |

Hispanic: 11 Black: 12 Other: 5 White: 72 |

Insured: 73 Uninsured: 12 Missing: 15 |

NR |

| 2017, Massie | ESKD | 133 824 | Linkage of OPTN data (1987–2015) and national kidney replacement treatment records, SSDMF. Median follow‐up: NR | 40* | ESKD: 39 No ESKD: 59 |

Hispanic: % NR ESKD, Black: 34 No ESKD, Black: 13 |

NR | NR |

| 2018, Wainright | ESKD | 123 526 | Linkage of OPTN LKD data (1994–2016) and national kidney replacement treatment records, SSDMF. Median follow‐up: 10.3 | ESKD: 38 No ESKD: 41 | ESKD: 42 No ESKD: 60 |

ESKD

No ESKD

|

NR | NR |

| 2019, Holscher |

Early (within first 2 yrs post‐donation)

|

41 260 | Linkage of OPTN data (2008–2014) with OPTN living donor follow‐up form data. Max follow‐up: 2 yrs | 42* | 62 |

Hispanic ethnicity, reported separately from race: 14 Race:

|

Insured 73 Uninsured: 13 Unknown: 14 |

Some college or higher

|

| 2019, Lentine |

DM

|

28 515 | Retrospective cohort study using a large US pharmaceutical claims data warehouse‐ comprises National Council for Prescription Drug Program 5.1‐format prescription claims aggregated from multiple sources including data clearinghouses, retail pharmacies, and prescription benefit managers (2007 to 2016). Mean follow‐up: 3.8 yrs | 43 | 67 |

Hispanic: 12 White: 74 Black: 11 Other▪: 4 |

Insured: 79 Uninsured: 10 Unknown: 11 |

College or higher: 67 GS/HS: 25 Unknown: 8 |

| 2020, Muzaale | ESKD, stratified by biological relatedness | 143 750 | Linkage of OPTN LKD data (1987–2017) and national kidney replacement treatment records. Median follow‐up: 12 yrs | 40 | 59 |

Hispanic: 13 Asian: 3 Black: 12 White: 72 |

NR |

College graduate: 26 Post‐graduate education: 11 |

| 2021, Augustine | Change in eGFR, proteinuria | 34 504 | LKD data (2008–2014) from the SRTR registry. Max follow‐up: 2 yrs | 42 | 63 |

Hispanic: 13.7 Black: 11.0 Other▪: 4.8 White: 70.5 |

Insured: 85 |

HS or less: 29 Some college or higher: 71 |

▪ other, not explicitly defined; ◊ same cohort (original study: Lentine et al., 2010); *median; median time follow‐up from donation to the end of observed insurance benefits; □ other, defined as American Indian, Native Hawaiian, Alaskan Native, Pacific Islander, and multiracial.

Abbreviations: AHRQ, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Am J Nephrol, American Journal of Nephrology; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; ESKD, end‐stage kidney disease; GN, glomerulonephritis, eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GS, grade school; HCUP‐NIS, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project‐National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample; HS, high school; HTN, hypertension; LKD, living kidney donor; LOS, length of stay; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; NR, not reported; OPTN, Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network; SRTR, Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients; SSDMF, Social Security Death Master File; Transp, Transplantation; yrs, years.

TABLE 2.

Findings of included studies

| Study | Post‐donation outcomes | Risk perspective b | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010, Friedman | Perioperative complications | Descriptive Comparative: within donors |

Adjusted OR for all complications after nephrectomy, in Hispanic donors compared to White donors: 0.97 (95% CI 0.75–1.25) |

|

2010, Lentine a |

CKD CVD DM HTN |

Descriptive Comparative: within‐donor. Comparison of Hispanic versus White individuals, and general population using NHANES 2005–2006 |

Adjusted HR, at 5 yrs post‐donation, of:

Estimated prevalence of HTN among Hispanic living donors 5 yrs after nephrectomy, as compared to the general Hispanic population, according to subgroup: Female sex evaluated at age 40: 18.4 (95% CI 13.4–23.1) in Hispanic donors; 10.4 (95% CI 8.5–12.7) in Hispanic NHANES respondents Male sex, evaluated at age 40: 20.6 (95% CI 14.9–25.8) in Hispanic donors; 9.8 (95% CI 7.9–12.0) in Hispanic NHANES respondents Female sex evaluated at age 55: 40.2 (95% CI 30.5–48.6) in Hispanic donors; 21.6 (95% CI 18.1–25.6) in Hispanic NHANES respondents Male sex, evaluated at age 55: 44.2 (95% CI 33.3–53.3) in Hispanic donors; 20.5 (95% CI 16.9–24.5) in Hispanic NHANES respondents Estimated prevalence of DM among Hispanic living donors 5 yrs after nephrectomy, as compared to the general Hispanic population, according to subgroup: Female sex evaluated at age 40: 5.7 (95% CI 2.6–8.7) in Hispanic donors; 7.5 (95% CI 6.0–9.3) in Hispanic NHANES respondents Male sex, evaluated at age 40: 5.2 (95% CI 2.3–8.1) in Hispanic donors; 7.2 (95% CI 5.6–9.3) in Hispanic NHANES respondents Female sex evaluated at age 55: 10.8 (95% CI 4.8–16.4) in Hispanic donors; 14.5 (95% CI 11.8–17.7) in Hispanic NHANES respondents Male sex, evaluated at age 55: 9.9 (95% CI 4.2–15.4) in Hispanic donors; 14.5 (95% CI 11.8–17.7) in Hispanic NHANES respondents |

| 2010, Segev | Mortality | Descriptive Comparative, within‐donor |

|

| 2011, Lentine a |

DM HTN Accounting for relatedness |

Descriptive Comparative, within‐donor |

Adjusted HR, at 5 yrs post‐donation, of developing DM or HTN among Hispanic donors related to recipients compared to White donors similarly related to recipients:

|

|

2014, Lentine Am J Nephrol a |

HTN | Descriptive Comparative, within‐donor |

Adjusted HR, at 5 yrs post‐donation, likelihood of pharmacy fills for Hispanic compared to White donors:

|

|

2014, Lentine Transp. |

CKD DM HTN |

Descriptive Comparative, within‐donor |

Adjusted HR, at 5 yrs post‐donation, among Hispanic donors with Medicare compared to White donors with Medicare of developing:

|

| 2014, Muzaale | ESKD | Descriptive Comparative, within‐donor; Attributable: LKD versus healthy non‐donors |

Cumulative Incidence of ESKD at 15 yrs per 10 000, among Hispanic donors: 32.6 (95% CI 17.9–59.1), compared to White donors: 22.7 (95% CI 15.6–30.1) Cumulative Incidence of ESKD at 15 yrs for Hispanic donors: 32.6 per 10 000 (95% CI 17.9–59.1), compared to healthy Hispanic non‐donors: 6.7 per 10 000 (95% CI 0.00–15.0), for an absolute risk increase of ESKD at 15 yrs of 25.9 per 10 000 (p = .002) |

| 2014, Schold | Rehospitalization | Descriptive Comparative, within‐donor |

Cumulative Incidence of:

Adjusted HR in Hispanic donors compared to White donors:

|

|

2015, Lam a |

Gout | Descriptive Comparative within‐donor | Adjusted HR, at 7 yrs post‐donation, among Hispanic donors compared to White donors of developing gout (diagnostic billing claim or pharmacy fill), 0.60 (95% CI 0.19–1.9); gout diagnosis alone: 0.72 (95% CI not reported, p‐value >0.05); starting gout medication alone: 1.05 (CI not reported, p‐value >0.05) |

|

2015, Lentine a |

Proteinuria Nephrotic Syndrome Nephritis/ Nephropathy Renal Failure Any kidney diagnosis CKD Accounting for relatedness |

Descriptive Comparative, within‐donor |

Adjusted HR, at 7 yrs post‐donation, among Hispanic donors compared to White donors for:

Adjusted HR (including adjustment for donor‐recipient relationship), at 7 yrs post‐donation, for Hispanic donors compared to White donors for:

|

|

2016, Anjum |

ESKD, early (0–9 yrs) & late (10–25 yrs) post‐ donation: DM‐related HTN‐related GN‐ related |

Descriptive Comparative, within‐donor |

IRR of late post‐donation (10–25 yrs) ESKD compared with early post donation ESKD (0–9 yrs) in Hispanic donors compared to White donors:

|

| 2016, Lentine |

Perioperative Complications |

Descriptive Comparative, within donors |

|

| 2017, Massie | ESKD | Descriptive Comparative, within‐donor | Adjusted HR of ESKD within Hispanic donors compared to White donors 1.16 (95% CI 0.75–1.80; p = .5) |

| 2018, Wainright | ESKD | Descriptive Comparative, within‐donor |

|

| 2019, Holscher |

Early, w/in 2 yrs post‐donation: DM HTN |

Descriptive Comparative, within‐donor |

Adjusted IRR for risk among Hispanic versus non‐Hispanic donors:

|

|

2019, Lentine, |

Anti‐DM med use, Non‐insulin anti‐DM med use, Insulin use | Descriptive Comparative, within‐donor |

Adjusted HR, at 9 yrs post‐donation, among Hispanic donors compared to White donors of:

|

|

2020, Muzaale |

ESKD, stratified by biological relatedness | Descriptive Comparative, within Hispanic donor only |

|

|

2021, Augustine |

Change in eGFR, Proteinuria | Descriptive Comparative, within‐donor |

|

Abbreviations: ACEi, ace inhibitor; ADM, anti‐diabetic medication; Am J Nephrol, American Journal of Nephrology; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BB, beta blocker; CCB, calcium channel blocker; CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; ESKD, end‐stage kidney disease; GN, glomerulonephritis; HR, hazard ratio; HTN, hypertension; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; OR, odds ratio; Transp, Transplantation; yrs, years.

Same cohort (original study: Lentine et al., 2010).

Perspective of risk among Hispanic living kidney donors, as previously described in Lentine et al. 24

TABLE 3.

Quality assessment of included studies: percentage of studies meeting quality criteria by outcome

|

Outcome Total studies (n = 18) |

Minimal risk for selection bias | Well‐described criteria | Valid outcome assessment |

Limitations and potential bias discussed |

Adjustment for confounders | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ESKD (n = 5) |

100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Conclusions made about Hispanic donors based on exploratory analysis (Massie 2017) SES variables not accounted for in analysis comparing Hispanic donors to White donors (Muzaale 2014; Anjum 2016; Massie 2017) SES variables not accounted for in analysis comparing Hispanic donors of varying relatedness (Muzaale 2020) |

|

CKD, change in eGFR, proteinuria (n = 4) |

25% | 100% | 75% | 100% | 100% |

Comprised of privately insured donors, only 8.2% Hispanic donors (Lentine 2010; Lentine 2015) Comprised of Medicare insured donors, only 5.7% Hispanic donors (Lentine 2014 Transp) Proteinuria not well defined (Augustine 2021) SES variables not accounted for in analysis (Lentine 2010; Lentine 2014 Transp; Lentine 2015) |

|

DM (n = 5) |

20% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Comprised of privately insured donors, only 8.2% Hispanic donors (Lentine 2010; Lentine 2011; Lentine 2019) Comprised of Medicare insured donors, only 5.7% Hispanic donors (Lentine 2014, Transp) SES factors not accounted for in analysis (Lentine 2010; Lentine 2011; Lentine 2014 Transp) |

|

HTN (n = 5) |

20% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Comprised of privately insured donors, only 8.2% Hispanic donors (Lentine 2010; Lentine 2011; Lentine 2014 AJN) Comprised of Medicare insured donors, only 5.7% Hispanic donors (Lentine 2014 Transp) SES factors not accounted for in analysis (Lentine 2010, Lentine 2011; Lentine 2014 AJN; Lentine 2014 Tranp) |

| Mortality (n = 1) | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | SES factors not accounted for in analysis, Mortality comparisons between Hispanic donors and Hispanic healthy controls not reported (Segev 2010) |

|

CVD (n = 1) |

0% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | Comprised of privately insured donors, only 8.2% Hispanic donors. SES factors not accounted for in analysis (Lentine 2010) |

|

Preoperative Complications (n = 2) |

50% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Subsampling and possible misrepresentation of total Hispanic living donors not fully addressed (Friedman 2010) Socioeconomic variables not accounted for in analysis (Friedman 2010) |

|

Hospitalization (n = 1) |

0% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | Hospitalizations possibly underestimated but would have affected all racial/ethnic groups. Unclear if study data is representative to OPTN Data (Schold 2014) |

|

Gout (n = 1) |

0% | 100% | 100% | 0% | 100% | Comprised of privately insured donors, only 8.2% Hispanic donors. Diagnosis not made by joint fluid analysis (Lam 2015) |

Abbreviations: AJN, American Journal of Nephrology; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus, HTN, hypertension; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESKD, end‐stage kidney disease; SES, socioeconomic; Transp, Transplantation.

Studies retrospectively linked living donor data to national databases such as CMS data 19 , 28 , 37 , 38 , 41 national transplant waiting and recipient lists, 19 , 41 living donor follow‐up form data, 30 , 42 or the Social Security Death Master File. 40 , 41 Donor information was also linked to administrative insurance data, 20 , 24 , 31 , 34 , 36 Medicare billing claims, 35 State Inpatient Databases (SID), 39 hospital discharge information, 29 and administrative records from an academic hospital consortium. 33 Studies included 4007 to 143 750 living donors, with mean ages of 37–54. Maximum follow‐up time varied from a perioperative donor nephrectomy period to 30 years post‐donation. Slightly more than half of study participants were women (≥54.8%). Hispanic donors ranged between 5.7% and 21.0% of the donor populations across studies. Most studies reported a combined race and ethnicity category and evaluated Hispanic donors as a mutually exclusive group (e.g., Hispanic donors, non‐Hispanic White, non‐Hispanic Black); one study specified an ethnicity category (Hispanic vs. all non‐Hispanic donors), separate from race. 30 Hispanic ethnicity by country of origin was not reported. Post‐donation health outcomes included mortality, perioperative complications, hospitalizations, ESKD, CKD, cardiovascular disease (CVD), DM, HTN, and gout.

In a large national study linking OPTN data to the Social Security Death Master File, Hispanic donors were not at increased for 90‐day surgical mortality as compared to White donors. 40 This study also evaluated mortality for donors of all racial and ethnic groups to healthy (non‐donor) controls over a 12‐year follow‐up. The risk of 12‐year mortality was no higher for all donors compared to matched healthy controls. However, mortality comparisons were not specifically reported between Hispanic donors and healthy (non‐donor) Hispanic controls.

Compared to White donors, Hispanic donors were more likely to develop Clavien grade IV or higher surgical complications, but were not at increased risk of developing complications overall, or by specific subtypes including genitourinary, vascular, bleeding, thrombosis, wounds, hernias, cardiac, respiratory, or other complications. 33 “Other complications” was a wide‐ranging category that included, but was not limited to nervous system complications, conversion to open nephrectomy, ICU stays, or death. Hispanic donors did not have an increased risk of post‐donation non‐pregnancy‐related hospitalizations as compared to White donors. 39

Most studies did not show a difference in the risk for developing ESKD among Hispanic donors compared to White donors. In a national study evaluating 123,526 donors, Hispanic donors were not at increased risk of ESKD at 20 years post‐donation compared to White donors after multivariable adjustment (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR]: 1.29 [95% CI 0.8–2.07]). 41 Furthermore, Anjum et al. evaluated the risk of ESKD by comparing the likelihood of late post‐donation (10–25 years) ESKD risk versus early post‐donation (0–9 years) ESKD risk, and by ESKD etiology. 28 Compared to White donors, the incidence of late post‐donation HTN‐related ESKD compared with early post‐donation HTN‐related ESKD in Hispanic donors was numerically greater but was not statistically significant. 28 There was no difference in the incidence of late post‐donation DM‐ or glomerulonephritis (GN)‐related ESKD compared with early post‐donation DM‐ or GN‐related ESKD, respectively, in Hispanic donors, compared to White donors. However, to further evaluate the risk of ESKD associated with kidney donation, Muzaale et al. assessed the 15‐year risk of ESKD between Hispanic donors and a healthy, matched non‐donor Hispanic population. The risk of ESKD among Hispanic donors was 32.6 per 10 000, and for healthy Hispanic non‐donors it was 6.7 per 10 000, for an absolute risk increase of 25.9 per 10 000 for Hispanic donors compared to the healthy non‐donor Hispanic population. 19

Hispanic donors had approximately twice the risk of developing CKD compared to White donors in a cohort of living kidney donors linked to administrative data of a private US health insurer 20 ; this elevated risk persisted even after accounting for relatedness, 34 but there was not an increased risk of developing proteinuria or nephrotic syndrome. Among a cohort of Medicare‐insured donors, Hispanic donors were not at increased risk of CKD or proteinuria compared to White donors. 35

In a cohort of donors linked to private insurance claims, Hispanic donors were more likely to have post‐donation drug‐treated DM compared to White donors (aHR: 2.94 [95% CI 1.57–5.51]), 20 although the difference in risk for reported DM from medical claims between Hispanic and White donors only reached borderline statistical significance. When relatedness was incorporated into the analysis, compared to White donors, the risk of post‐donation type 2 DM in Hispanic donors was numerically greater but was not statistically significant. 36 When OPTN data were linked to a US pharmaceutical claims data warehouse, there was no significant difference in the risk of taking any anti‐diabetic medications in Hispanic compared to White donors, but Hispanic donors were more likely to start insulin therapy. 32 Using Medicare claims, at 5 years post‐donation, Hispanic donors had twice the relative risk of post‐donation DM compared to White donors. 35 Regarding early post‐donation outcomes, relative to White donors, Hispanic donors were more likely to develop post‐donation DM within the first two years (aHR: 2.45 [95% CI 1.14–5.26]). 30

Mixed results were seen in the risk for developing post‐donation HTN among Hispanic donors compared to White donors. When OPTN data were linked to private insurance medical claims, compared to White donors, Hispanic donors had a 36% higher relative risk of post‐donation HTN diagnosis (from medical claims), but there was not an increased relative risk of post‐donation drug‐treated HTN. 20 Notably, this study demonstrated that the prevalence of HTN among Hispanic donors was higher than the general population (using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey [NHANES]). When accounting for relatedness, there was not an increased risk for post‐donation HTN diagnosis among Hispanic donors with private insurance, compared to similarly insured White donors. 36 In a study evaluating national living donor registry data linked to Medicare claims, Hispanic donors were not at increased risk of developing any post‐donation HTN or benign HTN in Hispanic relative to similarly insured White donors. 35 In terms of early post‐donation outcomes, compared to White donors, Hispanic donors were less likely to develop HTN in the first two years post‐donation. Of note, this last study included all OPTN data for living donors, and the analysis adjusted for several variables including education, employment, smoking, preoperative body mass index, and systolic blood pressure.

From the initial cohort linking 4650 donors from OPTN donor data to private insurance medical claims to evaluate the risk of post‐donation CKD, DM, and HTN, the relative risk of CVD and gout was also evaluated. Hispanic donors were not more likely to experience post‐donation CVD or gout compared to White donors. 20 , 31

4. DISCUSSION

In this systematic review, we found a wide array of health outcomes were evaluated among Hispanic living kidney donors. There was no significant difference in mortality between Hispanic and White donors. Although inferences cannot be made for mortality risk between Hispanic donors to Hispanic healthy controls, in a national cohort of live kidney donors, the 12‐year mortality was similar for overall racial and ethnic donors compared to matched healthy controls. 40 Most studies did not show a difference in long‐term risk for ESKD for Hispanic donors compared to White donors. There was a small absolute risk increase for ESKD among Hispanic donors compared to a healthy control group of Hispanic non‐donors. 19 As in the general population, most studies showed Hispanic donors were at higher risk for DM following nephrectomy as compared to White donors; however, mixed findings were seen regarding the risk for post‐donation CKD and HTN.

Contrasting inferences regarding the risk of post‐donation CKD observed among Hispanic donors compared to White donors are likely due to study populations, that is, one involving a cohort of younger privately insured kidney donors versus a study sample with older donors with Medicare coverage. For example, relative to White donors with private insurance, insured Hispanic donors had a higher risk of developing CKD. A positive association between having health insurance and prevalent CKD was also seen in a cross‐sectional study of over 15 000 Hispanic adults. 43 This may be related to increased comorbid conditions affecting individuals with CKD, making them more likely to obtain health insurance. 43 Regarding post‐donation HTN, in the national cohort using administrative insurance data by Lentine et al., the point estimates for the prevalence of HTN five years post‐donation for Hispanic donors in this cohort were higher than the general population using NHANES data. 20 This may be due to enhanced medical follow‐up following donor nephrectomy and subsequent diagnosis of underlying HTN, as compared to the general population. 20 It bears mentioning that the lack of risk differences or risk conflicting data does not imply a lack of inherent risk among Hispanic donors following nephrectomy. Nonetheless, research to date helps reassure that absolute risks following donor nephrectomy are low overall. 19 , 20 , 40

In most studies, Hispanic ethnicity was reported under race or a combined race and ethnicity category as a mutually exclusive subgroup from non‐Hispanic White, non‐Hispanic White/other, non‐Hispanic Black, or Other. Only one study reported Hispanic ethnicity separately from race. 30 Country of birth or residence, or duration of residence in the United States was not reported. This is likely due to small sample sizes in each subcategory of Hispanic donors and/or lack of data. The Living Donor Registration Worksheet by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) includes subsections regarding ethnicity and race for individuals to choose from. For Hispanic or Latino origin, individuals may choose between subcategories of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, other, or unknown. 44 If individuals identify with a different country of origin, this information may not be captured. The Worksheet also inquires about citizenship status and year of entry into the United States. These details are critical when evaluating health outcomes in the increasingly diverse Hispanic population, particularly since previous research shows the prevalence of various chronic diseases such as HTN, DM, and CKD vary markedly as a function of Hispanic background. 43 , 45 , 46 , 47

The Hispanic population is diverse, wherein individual‐level behaviors and beliefs may be influenced by a confluence of factors, including country of origin or residence, English proficiency, time of residence in the United States, etc. To explore the role of acculturation in health and disease, the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) was developed. HCHS/SOL is a multicenter epidemiologic study that has enrolled over 16 000 Hispanic adults living in the United States and aims to propagate future research examining health disparities among Hispanic communities. 48 , 49 In addition to reproaching how data are collected, investigators have redesigned health interventions targeting Hispanic communities, with a focus on cultural competency, which refers to “a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals that enables effective work in cross‐cultural situations.” 50 Within transplantation, cultural competency has been a critical component of health interventions aimed at mitigating persistent disparities in LDKT rates among minority populations. 14 , 15 , 51 , 52 To date, interventions aimed at increasing LDKT among Hispanic donors include a culturally competent educational website about LDKT, 53 , 54 a Spanish language mass media campaign on living organ donation attitudes and perceptions among Hispanics, 55 a hospital‐based, culturally sensitive LDKT‐specific educational program, 56 and the development of a culturally competent transplant program. 57 , 58 , 59 In a recent nonrandomized, multi‐site, hybrid trial, the implementation of a comprehensive culturally competent kidney transplant program, increased LDKT rates for Hispanic patients. 60 Positive results from culturally competent interventions further reinforce that sociocultural factors influence LDKT disparities. 61 , 62 , 63 In addition to cultural differences among Hispanic individuals, heath‐related behaviors or beliefs may be shaped by income, insurance status, knowledge of LDKT, geography, among other factors. Future studies should continue to evaluate unique barriers to LDKT that may arise within Hispanic communities residing in different regions of the country. Next steps also necessitate collaboration with community stakeholders to understand the complicated underpinnings giving rise to differences in outcomes and access to care.

To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive evaluation of health outcomes in Hispanic living kidney donors to date. Our review incorporates a carefully constructed literature search across several databases and the use of methods consistent with PRISMA guidelines. 64 We employed a comprehensive quality assessment of potential factors influencing the validity of included studies. Most studies had well‐defined outcomes, well‐described inclusion and exclusion criteria, and elucidated limitations and potential sources of bias (Table 3, Table S1). Included studies provided a diverse set of adult patient populations of varying ages, insurance status, sources of health information, and relatedness from cohorts stretching broad time periods.

Findings from our review are limited by several factors including relatively limited follow‐up time particularly as it relates to outcomes such as mortality, ESKD, or CVD‐related events. Acknowledging the limitations of the data, no clear associations emerged among variables that would likely be linked in clinical contexts, including hypertension, proteinuria, CKD, and ESKD. Some outcomes were examined in selective groups of living kidney donors, such as those with private insurance or Medicare. Only seven studies accounted for some level of socioeconomic status in their analyses (Table S1). Hispanic donors were classified into one homogeneous group, we were not able to ascertain national geographic variations in post‐donation outcomes, and lastly, our findings may lack generalizability to donor populations in other countries.

In summary, available evidence suggests there is not a substantial difference in long‐term risk of mortality, ESKD, CVD, or non‐pregnancy‐related hospitalizations in Hispanic donors as compared to White donors in the United States. Hispanic donors appeared at higher risk for DM following nephrectomy as compared to White donors; however, there were mixed results for the risk of developing post‐donation HTN and CKD. Overall absolute risks of donation remain small and should encourage efforts to expand LDKT. Future studies should evaluate cultural, socioeconomic, and geographic differences within the heterogeneous Hispanic donor population, which may further explain variation in health outcomes.

DISCLOSURE

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Purnell is the Chair of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons (ASTS) Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee; a member of the Governing Board of Directors for the National Minority Organ Tissue Transplant Education Program (MOTTEP); and a member of the Governing Board of Trustees for the Living Legacy Foundation of Maryland (LLF). The ASTS, National MOTTEP, and LLF played no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript or the decision to submit for publication.

Alvarado F, Cervantes CE, Crews DC, et al. Examining post‐donation outcomes in Hispanic/Latinx living kidney donors in the United States: A systematic review. Am J Transplant. 2022;22:1737–1753. doi: 10.1111/ajt.17017

Funding information

Dr. Alvarado was supported, in part, by grant 2T32DK773226 from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIH/NIDDK). Dr. Crews was supported, in part, by grant 1K24HL148181 from the NIH/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Al Ammary was supported, in part, by grant K23DK129820 from the NIH/NIDDK. Dr. Purnell was supported, in part, by grant K01HS024600 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The NIH and AHRQ had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript or the decision to submit for publication.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no new data were generated during the current study. The data that support the findings of this study are available in the manuscript tables and supplementary material of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Krogstad JM, Noe‐Bustamante L. Key facts about U.S. Latinos for National Hispanic Heritage Month. Pew Research Center. Updated September 9, 2021. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact‐tank/2021/09/09/key‐facts‐about‐u‐s‐latinos‐for‐national‐hispanic‐heritage‐month/

- 2. González Burchard E, Borrell LN, Choudhry S, et al. Latino populations: a unique opportunity for the study of race, genetics, and social environment in epidemiological research. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(12):2161‐2168. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.068668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Noe‐Bustamante L, Mora L, HugoLopez M. About one‐in‐Four U.S. hispanics have heard of latinx, but just 3% use it. Pew Reseach Center. Updated August 11, 2020. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/wp‐content/uploads/sites/5/2020/08/PHGMD_2020.08.11_Latinx_FINAL.pdf

- 4. Office of Management and Budget . Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. Federal Register Notice October 30, 1997. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/omb/fedreg_1997standards

- 5. Desai N, Lora CM, Lash JP, Ricardo AC. CKD and ESRD in US hispanics. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73(1):102‐111. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.02.354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hall YN. Social determinants of health: addressing unmet needs in nephrology. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;72(4):582‐591. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Crews DC, Liu Y, Boulware LE. Disparities in the burden, outcomes, and care of chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014;23(3):298‐305. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000444822.25991.f6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aguayo‐Mazzucato C, Diaque P, Hernandez S, Rosas S, Kostic A, Caballero AE. Understanding the growing epidemic of type 2 diabetes in the Hispanic population living in the United States. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2019;35(2):e3097. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services; 2020. Accessed October 5, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national‐diabetes‐statistics‐report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 10. USRD System 2020 USRDS Annual Data Report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. 2020. https://adr.usrds.org/2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11. Lora CM, Daviglus ML, Kusek JW, et al. Chronic kidney disease in United States Hispanics: a growing public health problem. Ethnicity Dis. 2009;19(4):466‐472. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peralta CA, Katz R, DeBoer I, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in kidney function decline among persons without chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(7):1327‐1334. doi: 10.1681/asn.2010090960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fischer MJ, Hsu JY, Lora CM, et al. CKD progression and mortality among Hispanics and non‐Hispanics. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(11):3488‐3497. doi: 10.1681/asn.2015050570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Purnell TS, Luo X, Cooper LA, et al. Association of race and ethnicity with live donor kidney transplantation in the United States from 1995 to 2014. JAMA. 2018;319(1):49‐61. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network . National Data, Transplants in the U.S. by Recipient Ethnicity. Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Accessed December 2, 2021. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view‐data‐reports/national‐data/

- 16. Al Ammary F, Bowring MG, Massie AB, et al. The changing landscape of live kidney donation in the United States from 2005 to 2017. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(9):2614‐2621. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Al Ammary F, Yu Y, Ferzola A, et al. The first increase in live kidney donation in the United States in 15 years. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(12):3590‐3598. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Al Ammary F, Thomas AG, Massie AB, et al. The landscape of international living kidney donation in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(7):2009‐2019. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Wang M‐C, et al. Risk of end‐stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2014;311(6):579‐586. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.285141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lentine K, Schnitzler M, Xiao H, et al. Racial variation in medical outcomes among living kidney donors. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):724‐732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lentine KL, Lam NN, Segev DL. Risks of living kidney donation: current state of knowledge on outcomes important to donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(4):597‐608. doi: 10.2215/cjn.11220918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davis CL. Living kidney donors: current state of affairs. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2009;16(4):242‐249. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2009.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lentine KL, Segev DL. Health outcomes among non‐Caucasian living kidney donors: knowns and unknowns. Transpl Int. 2013;26(9):853‐864. doi: 10.1111/tri.12088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Garg AX, et al. Understanding antihypertensive medication use after living kidney donation through linked national registry and pharmacy claims data. Am J Nephrol. 2014;40(2):174‐183. doi: 10.1159/000365157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Purnell TS, Auguste P, Crews DC, et al. Comparison of life participation activities among adults treated by hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(5):953‐973. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13(Suppl 1):S31‐S34. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_543_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross‐Sectional Studies. Accessed August 1, 2020. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health‐topics/study‐quality‐assessment‐tools

- 28. Anjum S, Muzaale AD, Massie AB, et al. Patterns of end‐stage renal disease caused by diabetes, hypertension, and glomerulonephritis in live kidney donors. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(12):3540‐3547. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Friedman AL, Cheung K, Roman SA, Sosa JA. Early clinical and economic outcomes of patients undergoing living donor nephrectomy in the United States. Arch Surg. 2010;145(4):356; discussion 362. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Holscher CM, Bae S, Thomas AG, et al. Early hypertension and diabetes after living kidney donation: a National Cohort Study. Transplantation. 2019;103(6):1216‐1223. doi: 10.1097/tp.0000000000002411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lam NN, Garg AX, Segev DL, et al. Gout after living kidney donation: correlations with demographic traits and renal complications. Am J Nephrol. 2015;41(3):231‐240. doi: 10.1159/000381291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lentine KL, Koraishy FM, Sarabu N, et al. Associations of obesity with antidiabetic medication use after living kidney donation: an analysis of linked national registry and pharmacy fill records. Clin Transplant. 2019;33(10):e13696. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lentine KL, Lam NN, Axelrod D, et al. Perioperative complications after living kidney donation: a National study. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(6):1848‐1857. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Garg AX, et al. Race, relationship and renal diagnoses after living kidney donation. Transplantation. 2015;99(8):1723‐1729. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, et al. Consistency of racial variation in medical outcomes among publicly and privately insured living kidney donors. Transplantation. 2014;97(3):316‐324. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000436731.23554.5e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, et al. Associations of recipient illness history with hypertension and diabetes after living kidney donation. Transplantation. 2011;91(11):1227‐1232. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31821a1ae2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Massie AB, Muzaale AD, Luo X, et al. Quantifying postdonation risk of ESRD in living kidney donors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(9):2749‐2755. doi: 10.1681/asn.2016101084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Al Ammary F, et al. Donor‐recipient relationship and risk of ESKD in live kidney donors of varied racial groups. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(3):333‐341. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schold JD, Goldfarb DA, Buccini LD, et al. Hospitalizations following living donor nephrectomy in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(2):355‐365. doi: 10.2215/cjn.03820413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Segev DL, Muzaale AD, Caffo BS, et al. Perioperative mortality and long‐term survival following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2010;303(10):959‐966. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wainright JL, Robinson AM, Wilk AR, Klassen DK, Cherikh WS, Stewart DE. Risk of ESRD in prior living kidney donors. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(5):1129‐1139. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Augustine JJ, Arrigain S, Mandelbrot DA, Schold JD, Poggio ED. Factors associated with residual kidney function and proteinuria after living kidney donation in the United States. Transplantation. 2021;105(2):372‐381. doi: 10.1097/tp.0000000000003210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ricardo AC, Flessner MF, Eckfeldt JH, et al. Prevalence and correlates of CKD in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(10):1757‐1766. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02020215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. United Network for Organ Sharing . Living Donor Registration Worksheet. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://unos.org/wp‐content/uploads/LDR‐1.pdf

- 45. Schneiderman N, Llabre M, Cowie CC, et al. Prevalence of diabetes among Hispanics/Latinos from diverse backgrounds: the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Diabetes Care. 2014;37(8):2233‐2239. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Elfassy T, Zeki Al Hazzouri A, Cai J, et al. Incidence of Hypertension among US Hispanics/Latinos: the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(12):e015031. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.015031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ricardo AC, Loop MS, Gonzalez F, et al. Incident chronic kidney disease risk among Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31(6):1315‐1324. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2019101008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hispanic Community Health Study (HCHS)/ Study of Latinos (SOL). Accessed October 1, 2021. https://sites.cscc.unc.edu/hchs/

- 49. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute . Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Accessed October 1, 2021. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/science/hispanic‐community‐health‐studystudy‐latinos‐hchssol

- 50. National Prevention Information Network . Cultural Competence In Health And Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Updated September 10, 2021. Accessed November 28, 2021. https://npin.cdc.gov/pages/cultural‐competence#what

- 51. Boulware LE, Sudan DL, Strigo TS, et al. Transplant social worker and donor financial assistance to increase living donor kidney transplants among African Americans: the TALKS Study, a randomized comparative effectiveness trial. Am J Transplant. 2021;21(6):2175‐2187. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Purnell TS, Hall YN, Boulware LE. Understanding and overcoming barriers to living kidney donation among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2012;19(4):244‐251. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2012.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gordon EJ, Feinglass J, Carney P, et al. An interactive, bilingual, culturally targeted website about living kidney donation and transplantation for hispanics: development and formative evaluation. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4(2):e42. doi: 10.2196/resprot.3838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gordon EJ, Feinglass J, Carney P, et al. A culturally targeted website for Hispanics/Latinos about living kidney donation and transplantation: a randomized controlled trial of increased knowledge. Transplantation. 2016;100(5):1149‐1160. doi: 10.1097/tp.0000000000000932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Alvaro EM, Siegel JT, Crano WD, Dominick A. A mass mediated intervention on Hispanic live kidney donation. J Health Commun. 2010;15(4):374‐387. doi: 10.1080/10810731003753133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cervera I, DeVargas M, Cortes C, et al. A hospital‐based educational approach to increase live donor kidney transplantation among Blacks and Hispanics. Med Sci Technol. 2015;56:43‐52. doi: 10.12659/MST.892986 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gordon EJ, Reddy E, Gil S, et al. Culturally competent transplant program improves Hispanics’ knowledge and attitudes about live kidney donation and transplant. Prog Transplant. 2014;24(1):56‐68. doi: 10.7182/pit2014378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gordon EJ, Lee J, Kang R, et al. Hispanic/Latino disparities in living donor kidney transplantation: role of a culturally competent transplant program. Transplant Direct. 2015;1(8):e29. doi: 10.1097/txd.0000000000000540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gordon EJ, Romo E, Amórtegui D, et al. Implementing culturally competent transplant care and implications for reducing health disparities: a prospective qualitative study. Health Expect. 2020;23(6):1450‐1465. doi: 10.1111/hex.13124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gordon EJ, Uriarte JJ, Lee J, et al. Effectiveness of a culturally competent care intervention in reducing disparities in Hispanic live donor kidney transplantation: a hybrid trial. Am J Transplant. 2022;22(2):474‐488. 10.1111/ajt.16857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gordon EJ, Mullee JO, Ramirez DI, et al. Hispanic/Latino concerns about living kidney donation: a focus group study. Prog Transplant. 2014;24(2):152‐162. doi: 10.7182/pit2014946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shilling LM, Norman ML, Chavin KD, et al. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of the barriers to living donor kidney transplantation among African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(6):834‐840. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kutzler HL, Peters J, O’Sullivan DM, et al. Disparities in end‐organ care for Hispanic patients with kidney and liver disease: implications for access to transplantation. Curr Surg Rep. 2020;8(3):3. doi: 10.1007/s40137-020-00248-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339(jul21 1):b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no new data were generated during the current study. The data that support the findings of this study are available in the manuscript tables and supplementary material of this article.