Abstract

It is well established that there is a fundamental need to develop a robust therapeutic alliance to achieve positive outcomes in psychotherapy. However, little is known as to how this applies to psychotherapies which reduce suicidal experiences. The current narrative review summarizes the literature which investigates the relationship between the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy and a range of suicidal experiences prior to, during and following psychotherapy. Systematic searches of MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Web of Science, EMBASE and British Nursing Index were conducted. The search returned 6472 studies, of which 19 studies were eligible for the present review. Findings failed to demonstrate a clear link between suicidal experiences prior to or during psychotherapy and the subsequent development and maintenance of the therapeutic alliance during psychotherapy. However, a robust therapeutic alliance reported early on in psychotherapy was related to a subsequent reduction in suicidal ideation and attempts. Study heterogeneity, varied sample sizes and inconsistent reporting may limit the generalizability of review findings. Several recommendations are made for future psychotherapy research studies. Training and supervision of therapists should not only highlight the importance of developing and maintaining the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy when working with people with suicidal experiences but also attune to client perceptions of relationships and concerns about discussing suicidal experiences during therapy.

Keywords: psychotherapy, suicide, systematic review, Therapeutic alliance

Key Practitioner Message.

This is the first review to investigate the relationship between the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy and suicidal experiences pre‐therapy, during therapy and after therapy.

There is no clear link between suicidal experiences prior to psychotherapy and the strength of the therapeutic alliance.

A robust, client‐viewed, therapeutic alliance established early in psychotherapy is related to reduced future suicidal experiences.

Training and supervision of therapists should highlight the importance of, and, key considerations, when developing and maintaining a therapeutic alliance with people with suicidal experiences.

Practitioners involved in psychotherapy trials with suicidal experience outcomes should routinely measure the therapeutic alliance and assess the relationship between alliance and suicidal experiences.

1. INTRODUCTION

Suicidal ideation, attempts and deaths by suicide are a major global health concern and a public health priority. Estimates show that in 2018, 14.8 in every 100,000 people in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020) and 11.2 in every 100,000 people in the United Kingdom (Office for National Statistics, 2019) died by suicide. The risk of death by suicide is higher in people with mental health diagnoses, such as borderline personality disorder (45.1%) and depression (19.7%), than within the general population (Chesney et al., 2014). Suicidal ideation and suicide plans have also been described as key predictors of suicide attempts and suicide deaths (Bertelsen et al., 2007; O'Connor & Kirtley, 2018). Furthermore, male gender, fewer years spent in education, a history of physical and repeated sexual abuse, unemployment and homelessness increase the risk of suicidal experiences (Nock & Kessler, 2006; Schneider et al., 2011; Windfuhr & Kapur, 2011).

Evidence‐based psychotherapies, which are grounded in contemporary models of the psychological mechanisms underpinning suicide, have been developed to target suicidal thoughts and behaviour (Johnson et al., 2008; Joiner & Silva, 2012; O'Connor & Kirtley, 2018; Williams, 1997). There is evidence from two meta‐analytic reviews to suggest that psychotherapies such as cognitive therapy (CT), cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT), mentalization‐based treatment and interpersonal psychotherapy reduce suicidal behaviour (Calati & Courtet, 2016; Tarrier et al., 2008).

For the purpose of this review, a definition of psychotherapy was based on that of Beutler (2009): the consideration of client and therapist factors, development of the client‐therapist alliance and implementation of therapeutic techniques which aim to facilitate beneficial change for people with mental health problems. One aspect of psychotherapy, which has gained significant attention, is the therapeutic alliance. In broad terms, the therapeutic alliance captures perceptions of the evolving working relationship between a client and therapist in a wide range of clinical interactions, including psychological talking therapies. The alliance, as perceived by both therapists and clients, is recognized as pivotal to a positive outcome from psychotherapy (Flückiger et al., 2018). This is a finding which traverses a variety of therapeutic modalities and a diverse range of mental health problems (Flückiger et al., 2018).

Despite the abundance of research indicating a relationship between the therapeutic alliance and therapeutic outcomes, a query remains over whether the therapeutic alliance is, indeed, a predictor of outcome alone, a development which resulted from expectations of psychotherapy and/or a facilitator of effective psychotherapy (Horvath, 2006; Zilcha‐Mano, 2017). A possible barrier to addressing such a query within the current literature is that the majority of measures of therapeutic alliance are captured at one time point during psychotherapy. This limits insight into the alliance–outcome relationship at other time points during therapy (Zilcha‐Mano, 2017). A new model has been proposed by Zilcha‐Mano (2017) for understanding the possible therapeutic nature of the alliance, which posited that client ‘trait‐like’ (e.g. patterns of relating, expectations of relationships and appraisals of themselves and interactions with others) and alliance ‘state‐like’ (e.g. ‘in‐the‐moment’ dynamic and therapeutic nature of the alliance itself) components contribute to therapeutic change. That said, the use of the term ‘trait’ implies that the characteristics that clients bring to the therapeutic situation are unable to change, whereas a fundamental aim of therapy is to bring about change. Moreover, it appears that this model is yet to be empirically tested. Furthermore, measures of the therapeutic alliance need to be reviewed to examine whether they are sensitive to session‐by‐session therapeutic change (Zilcha‐Mano, 2017). Therefore, session‐by‐session ratings of therapeutic alliance may allow researchers to better understand if the alliance is uniquely related to therapeutic change.

Three factors in the development of the therapeutic alliance have been scrutinized, which include the effect of mental health problems on the development of the alliance, breakdowns or ruptures (Safran et al., 1990) and the effect that the alliance has on positive changes in mental health problems subsequent to therapy (DeRubeis & Feeley, 1990). That said, the pathways to perceived helpful therapy may be cyclical or non‐linear.

In terms of pre‐therapy experiences, the severity of anxiety, depression, psychosis, attachment style and number of traumatic events were not associated with client perspectives of the alliance early on in psychological therapies, such as supportive expressive psychotherapy and CBT (Gibbons et al., 2003;Reynolds et al., 2017; Shattock et al., 2018). In contrast, experience of depression pre‐therapy has been significantly related to poorer client perception of the alliance (Shattock et al., 2018). Additionally, depression and coping styles such as acceptance and seeking emotional support prior to starting therapy were significantly correlated with client perception of a stronger therapeutic alliance (Reynolds et al., 2017; Shattock et al., 2018). Despite the conflicting evidence presented within the literature, mental health problems and coping styles that pre‐existed before the start of therapy may lend to the investment in a stronger initial client–therapist bond, which could positively feed into a strengthening of the alliance in therapy.

The therapeutic alliance has been recognized as non‐linear, often fluctuating, during the course of psychotherapy. Events such as alliance ruptures (e.g. breakdown in communication and poor understanding) and the resolution of such ruptures may occur between the client and therapist (Safran et al., 1990; Safran & Muran, 2006). It is necessary for the therapist to be able to recognize when ruptures occur and to negotiate with the client ways of resolving such ruptures. It has been posited that alliance ruptures and harmful client–therapist interactions may be risk factors for adverse reactions to therapy (Parry et al., 2016). However, studies have suggested that alliance ruptures and subsequent repairs are associated with not only positive outcomes and a stronger therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy (Muran et al., 2009) but also greater improvements in mental health problems, compared to no experience of alliance ruptures (Stiles et al., 2004). This may be due to clients learning from interpersonal struggles (Safran et al., 1990; Safran & Muran, 2000). Nevertheless, it is important to monitor and address the occurrence of alliance ruptures and harmful interactions in therapy to ensure the safe delivery of therapy and mitigate against possible adverse reactions to therapy (Parry et al., 2016).

The alliance–outcome relationship is well established. Not only has a stronger client‐therapist alliance predicted positive outcomes post‐therapy (Flückiger et al., 2018), but the possible reciprocal relationship with psychological distress has been explored. Evidence pertaining to this issue largely comes from research involving those experiencing anxiety and/or depression. Early on in CBT, improvement in experiences of depression were found to be related to a more robust therapeutic alliance, but the alliance was not found to be related to subsequent improvement in experiences (DeRubeis & Feeley, 1990; Strunk et al., 2010). Moreover, a stronger therapeutic alliance developed during supportive‐expressive psychotherapy was associated with less severe experiences of depression across four time‐points. But severity of depression was not associated with the perceived strength of the therapeutic alliance at subsequent time points (Zilcha‐Mano et al., 2014). Additionally, a reciprocal temporal relationship between the therapeutic alliance and changes in severity of depression and psychological distress has been observed during the delivery of a range of psychotherapies, including, cognitive behavioural, psychodynamic and alliance‐fostering approaches (Crits‐Christoph et al., 2011; Falkenström et al., 2013). Therefore, perceptions of a positive therapeutic alliance, especially when formed during initial sessions, may lead to subsequent reductions in psychological distress early on in psychotherapy which may in turn positively reinforce an even stronger therapeutic alliance. It remains unclear how generalizable such findings are to populations experiencing other mental health problems or different types of therapy. One area for which there is relatively scant research is the effect of severe mental health problems and suicidal experiences prior to starting therapy on the client–therapy alliance.

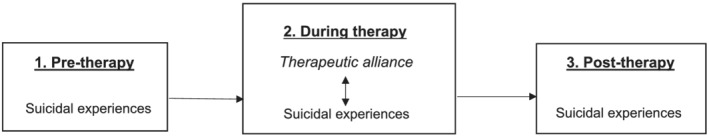

Considering the significance of the therapeutic alliance and therapeutic outcome, very few suicide prevention‐focused intervention studies have examined the contribution of the therapeutic alliance upon suicidal outcome variables. One existing review has broadly explored the relationship between therapeutic alliance and suicidal ideation, self‐harm and suicide attempts in people accessing mental health services or receiving psychotherapy (Dunster‐Page et al., 2017). Findings indicated that a more robust therapeutic alliance was associated with a reduction in suicidal thoughts and instances of self‐harm, whereas there were mixed results regarding the relationship with suicide attempts (Dunster‐Page et al., 2017). Such inconsistencies could be due to lower frequency of suicide attempts and therefore less power to detect a relationship. The focus of the review was quite broad, looking at the alliance in both inpatient and outpatient mental health teams in the United States, individual care coordinators from community mental health teams in the United Kingdom, as well as psychotherapy, and the relationship between both suicide and self‐harm outcomes. Thus far, there is a gap in the evidence base, whereby the direction of the relationship between the therapeutic alliance established during psychotherapy and suicidal experiences has not yet been investigated using systematic review methods. Hence, the overarching aims of the current review were to investigate the nature of the relationship between the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy and suicidal experiences by examining the evidence for suicidal thoughts and behaviours as (1) predictors of the alliance (i.e. suicidal experiences pre‐therapy influencing the therapeutic alliance), (2) correlates of the alliance (i.e. suicidal experiences related to the therapeutic alliance at the same time point during psychotherapy) and (3) outcomes due to the therapeutic alliance (i.e. the therapeutic alliance altering suicidal experiences post‐therapy [see Figure 1]). An additional aim was to assess the reliability, validity, applicability, findings and reporting of studies which are published and included in the current systematic review.

FIGURE 1.

A diagram to illustrate the direction of the three types of relationship under investigation between the therapeutic alliance and suicidal experiences

2. METHOD

The current systematic review was conducted and is reported in line with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA; Liberati et al., 2009) and was registered on the Prospero Centre for Reviews and Dissemination website (CRD42019138823).

2.1. Search strategy

The database search strategy was carried out from 1976 (MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO and Web of Science) or date of inception (1987; British Nursing Index) to December 2021. The search was limited to 1976 as this is predominantly when the first therapeutic alliance measures were developed (Luborsky, 1976). A restriction on English language was applied. Search terms comprised phrases relating to suicide, psychotherapy and therapeutic alliance, all separated by the Boolean operator; ‘AND’. The first search term was ‘suicid*’ to capture all studies relating to suicidal experiences such as suicidal ideation and attempts and death by suicide. The second set of search terms were those related to psychotherapy: ‘cognitiv*’ OR ‘psychotherap*’ OR ‘psycholog* therap*’ OR ‘psychosocial’ OR ‘talking therap*’ OR ‘counseling’ OR ‘counselling’ OR ‘talking treatment’ OR ‘psycholog* intervention*’. The final set of search terms were related to the therapeutic alliance: ‘alliance’ OR ‘therap* relation*’ OR ‘bond*’ OR ‘connection’ OR ‘rapport’ OR ‘collaborat*’ OR ‘therap* attachment’ OR ‘engage*’ OR ‘empath*’ OR ‘withdraw*’ OR ‘therap* delivery’ OR ‘therap* process’. Forward and backward citation chaining (Booth et al., 2013) was utilized to account for the possibility of potential peer‐reviewed articles being missed in the original search. This technique involved using the ‘finding citing articles’ feature on Ovid to identify relevant studies which cited included studies, in addition to examining reference lists for all studies included in the present review. The use of citation chaining is encouraged to ensure the review strategy is comprehensive (Booth et al., 2013).

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Studies were deemed eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (1) written in English; (2) quantitative empirical studies; (3) published in a peer‐reviewed academic journal; (4) involved individuals of any age, gender, ethnicity and presenting mental health problem who have had suicidal experiences (i.e. suicidal ideation or attempts) in their lifetime or had died by suicide; (5) involved a psychotherapeutic intervention delivered individually or in a group at any point in time; (6) any measure of therapeutic alliance; (7) any measure of suicidal experiences (such criteria ensured that measures which may not be validated questionnaires, e.g. hospital or other records, were included); and (8) reported analyses of the relationship between the therapeutic alliance and at least one type of suicidal experience.

Studies were excluded if they met the following criteria: (1) review articles, clinical practice, position papers, treatment guidelines, grey literature and qualitative only studies; (2) intervention was solely pharmacological therapy (i.e. medicinal treatments), alternative medicinal or other treatment (i.e. homoeopathy, acupuncture, osteopathy, chiropractic, herbal medicines, aromatherapy and prescribed exercise) or self‐guided interventions, including interventions which primarily use technology (i.e. smartphone application or website where a human therapist is not conducting psychotherapy).

2.3. Study selection

Titles and abstracts were screened by the first author (CH). Full texts of potentially eligible papers were then examined by the first author to confirm eligibility. A random sample of 13.5% (n = 32) of all full texts was screened by a second independent reviewer (JQ) to determine inter‐rater reliability. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Overall, there was 100% agreement (κ = 1). Queries regarding whether studies met with the eligibility criteria were resolved by discussed with three experienced clinical and academic psychologists (PG, GH, DP).

2.4. Data extraction and analysis

Data were extracted with reference to a data extraction table, which had been created and piloted by the first author, comprising study characteristics, client and therapist characteristics, modes of therapy delivery and data analysis (see Appendix A for more specific details of data extracted). For those studies that measured the therapeutic alliance and suicidal experiences but did not analyse the relationship between these two variables, the relevant data or analyses were then requested from the corresponding authors. Of 27 authors who were contacted, four provided the necessary data analysis. Corresponding authors from 17 out of 19 included studies were contacted to request missing data.

2.5. Quality assessment using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

There is no consensus as to which quality assessment tool is most suitable for use across a variety of study designs (Katrak et al., 2004). Included studies in the current review collected data using RCT and cohort designs. However, specific questions pertaining to the quality of randomization processes were not applicable to the current review question, which focused on the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy. Additionally, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) (2018) checklist for cohort studies has been specifically recommended for critical appraisals of cohort studies (Rosella et al., 2016). The CASP checklists provide clinicians and researchers with a framework to assess the reliability, validity, applicability, findings and reporting of studies which are published. As the questions posed by the CASP checklist were broad, each question was tailored to the current systematic review topic to ensure the quality assessment of studies was relevant. For example, adapted questions included assessing whether measures of therapeutic alliance and suicidal experiences were reliable and valid, the therapists were systematically trained, therapist fidelity monitored and the psychotherapy was safe. Therefore, each study was quality assessed using an adapted version of the CASP (2018) checklist for specific study designs.

The first author (CH) quality assessed all included studies, of which five (26%) were also assessed by an independent second reviewer (JQ) to determine inter‐rater reliability. Four studies were selected at random based on each study design. However, one study was specifically selected to be independently quality assessed as the first author of the present review is the first author of the included paper. There was 96% agreement (κ = .92) on the CASP ratings for the five selected papers.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search results

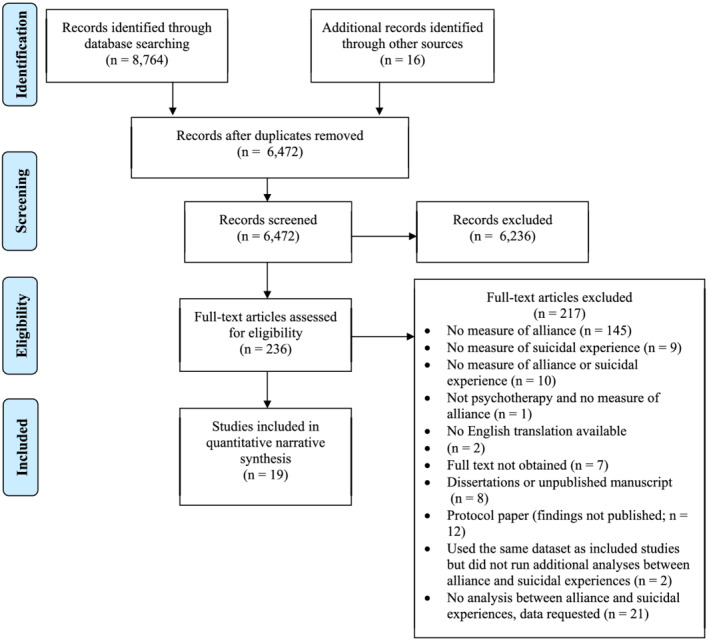

A summary of study flow from initial database search to inclusion at full‐text level are presented in Figure 2. Notably, 23 studies measured both the therapeutic alliance and suicidal experiences but did not conduct a statistical analysis of the relationship between these variables. Nineteen studies met inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review, of which two sets of two studies (n = 4) analysed data from the same pool of participants.

FIGURE 2.

PRISMA diagram

3.2. Study characteristics

As might be expected, there was considerable heterogeneity across studies with respect to geographical location, study design, settings, sample sizes, participant characteristics, types and delivery mode of therapy offered, characteristics of the therapists, measures of the therapeutic alliance, measures of suicidal experiences and study quality. Furthermore, analyses examined different directions of the relationship between the therapeutic alliance and suicidal experiences (pre‐therapy, during therapy and post‐therapy). The number of times each variable was measured and at which time points also varied considerably (e.g. baseline, during therapy at a single time point or session by session, upon therapy cessation and either once or multiple times at follow‐up time points). Additionally, some studies had low retention rates, unclear therapy or follow‐up timeframes and/or did not report or provide sufficient data (standard deviations, standard errors and confidence intervals). Due to clinical and methodological diversity, statistical heterogeneity and insufficient data, a meta‐analysis examining the relationships between the therapeutic alliance and suicidal experiences was considered inappropriate (Higgins & Green, 2011). Nine out of 19 studies were conducted in the United States, four in Canada and six in Europe.

Study details, such as design, study setting/recruitment sources, sample sizes, sample population, type of psychotherapy, therapy delivery characteristics, therapist qualifications and supervision, have been collated in Table 1. There are, however, several key points to note. For instance, most studies used a cohort/longitudinal or randomized controlled trial (RCT) design (including pilot RCTs) using opportunity sampling from the community, mental health inpatient and outpatient settings, with sample sizes ranging from 4 to 633 and follow‐up time periods between 2 weeks and a median of 4.19 years. Participants with different mental health problems were recruited across studies, but those with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder were represented most frequently, whereas people diagnosed with eating disorders, bipolar disorder or non‐affective psychosis had the least frequent representation. The mean age of participants ranged from just under 15 to just over 48 years. Ethnicity was predominantly Caucasian or not reported. Seven out of 13 RCTs compared psychological therapy with an active control (e.g. client‐centred, non‐directive supportive family therapy, psychodynamic, eclectic or cognitive therapy). The experience of the study therapists, who came from various allied mental health professions (e.g. social work, psychology and nursing) and were either in training or had qualifications ranging from masters and PhD degrees to professional registration in clinical psychology and psychiatry, ranged from 1 to 26 years. The types of therapy offered were also diverse including cognitive, psychodynamic and eclectic approaches, delivered in one‐to‐one settings (nine studies), groups (three studies) or a mixture of group and individual work (seven studies). The number of therapy sessions ranged from 3 to 339, but most (n = 12) studies offered 3–20 weekly sessions lasting between 60 and 180 min.

TABLE 1.

Included study characteristics in date order from oldest to most recent, participant age and ethnicity, details of psychotherapy delivery, format and context and therapist qualifications and supervision

| Study characteristics | Participants | Psychotherapy delivery, format and context | Therapists | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study number and reference | Country | Design | Sample population and study setting | Therapy arm sample size | Mean age | Ethnicity and Gender | Psychotherapy type and session length | Length and setting of psychotherapy | N and qualifications | Supervision |

| 1. Shearin and Linehan (1992) | USA | Cohort/longitudinal | People with a diagnosis of BPD and parasuicidal behaviour in the community | 4 | Not reported | Not reported; 100% female | Dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT): 60‐min individual sessions and 150‐min group skills per week | Up to 31 sessions over 7 months at an outpatient university research clinic | 4 psychology and nursing graduate students | Supervision provided to ensure adherence to DBT protocol, but no further details reported |

| 2. Turner (2000) | USA | Two‐armed RCT; active control | People with a diagnosis of BPD in the community |

Total: 24 DBT: 12 |

Total: 22.00 |

Total: 79.17% Caucasian; 79.17% female |

DBT: Individual (DBT skills sessions provided in individual sessions) a | Up to 84 individual sessions over 12 months at a community mental health outpatient clinic |

4 therapists; background in client‐centred, psychodynamic and family systems conducted both therapies DBT: Trained to conduct DBT |

Weekly group supervisions (one for each therapeutic modality). Reviewed therapy audio recordings to monitor treatment fidelity |

| Active control: 12 | Active control: Individual client‐centred therapy a | Active control: Trained to work with people diagnosed with BPD | ||||||||

| 3. Goldman and Gregory (2009) | USA | Two‐armed RCT; TAU control | Diagnosis of BPD; clinical settings—non‐specific | 15 | 27.40 | 85.70% Caucasian; 90% female | Dynamic deconstructive psychotherapy: Individual a | Up to 52 sessions over 12 months b | 5 therapists; 1 expert therapist, 4 third‐year trainee psychiatrists | Weekly group supervision. Biweekly individual supervision was used to review audio recordings to monitor treatment fidelity |

| 4. Hirsh et al. (2012) | Canada | Two‐armed RCT; active control | People with a diagnosis of BPD and experience of suicidal behaviour and NSSI outpatient |

Total: 87 DBT: 43 |

Total: 31.41 DBT: 30.56 |

Not reported; 100% female | DBT: 60‐min individual sessions, 120‐min skills group and 120‐min phone coaching | Sessions delivered weekly over 1 year at two teaching hospitals c |

25 therapists DBT: 13 therapists 3 psychiatrists, 4 PhD level psychologists, 5 master's level clinicians and 1 nurse |

DBT: Weekly group supervision (2 h) |

| Active control: 44 | Active control: 32.25 | Not reported | Active control: Individual general psychiatric management (includes dynamically informed psychotherapy) a |

Active control: 12 therapists 8 psychiatrists, 1 PhD level psychologist, 1 master's level clinician and 2 nurses |

Active control: Weekly group supervision (90 min) | |||||

| 5. Bryan et al. (2012) | USA | Cohort/longitudinal |

Military Primary care clinic |

497 | 37.14 | 54.10% Caucasian; 57.7% female | CBT: 30‐min individual sessions | Up to 8 sessions at a primary care clinic | 22 therapists; 8 clinical psychologists (6 trainers and 2 externship trainees), 9 predoctoral clinical psychology interns and 5 social worker interns | Interns were trained under the supervision of clinical psychologists to deliver CBT. No further details on supervision reported |

| 6. Perry et al. (2013) | Canada | Cohort/longitudinal | People with diagnoses of anxiety, depression and/or PD outpatient—psychiatry | 53 | 30.90 | Not reported; 77% female | Long‐term dynamic psychotherapy: Individual a | Up to 339 sessions over a median of 4.19 years at an outpatient clinic | 22 therapists; psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers and advanced practice nurses; 20 were also psychoanalysts | No supervision groups or specific therapy manual used |

| 7. Tsai et al. (2014) | Canada | Cohort/longitudinal | People with a diagnosis of depression who were outpatient/in the community | 80 | 47.82 | 76.10% Caucasian; 73% female | CBT for depression: 120‐min group sessions | Up to 10 sessions over 10 weeks at an outpatient community mental health service/hospital | 2 therapists; 1 clinical psychologist and 1 psychiatrist | Not reported |

| 8. Bedics et al. (2015) | USA | Two‐armed RCT; active control | People with a diagnosis of BPD and experience of suicidal behaviour and NSSI in the community |

Total: 101 DBT: 52 |

Total: 29.30 | Total: 86.50% Caucasian; 100% female | DBT: 60‐min individual sessions and 150 min of group skills and telephone consultations per week | Sessions delivered over 1 year at university outpatient clinic and community practice c |

37 therapists DBT: 15 (12 of whom had a doctoral degree) |

DBT: Weekly group supervision |

| Active control: 49 | Active control: Community treatment by experts (eclectic/psychodynamic therapy) a | Active control: 25 (14 of whom had a doctoral degree) | Active control: Not required to attend supervision | |||||||

| 9. Gysin‐Maillart et al. (2016) d | Switzerland | Two‐armed RCT; TAU control | People who had recently attempted suicide who are attending a psychiatry outpatient department | 60 | 36.50 | Not reported; 60% female | Attempted Suicide Short Intervention Program (ASSIP):Up to 90‐min individual sessions | 3 sessions (4 if necessary) delivered weekly at an outpatient department | 4 therapists; 1 psychiatrist and 3 clinical psychologists (2 of whom were experienced in clinical suicide prevention) | Regular supervision to review therapy video recordings to ensure therapy fidelity |

| 10. Gysin‐Maillart et al. (2017) d | Switzerland | RCT; TAU control | People who had recently attempted suicide who are attending a psychiatry outpatient department | 60 | 36.50 | Not reported; 60% female | ASSIP: Up to 90‐min individual sessions | 3 sessions (4 if necessary) delivered weekly at an outpatient department | 4 therapists; 1 psychiatrist and 3 clinical psychologists (2 of whom were experienced in clinical suicide prevention) | Regular supervision to review therapy video recordings to ensure therapy fidelity |

| 11. Plöderl et al. (2017) | Austria | Cohort/longitudinal | People who had attempted suicide and/or had suicidal ideation and were admitted to an inpatient ward | 633 | 39.19 | Not reported; 51% female | Individual and group psychotherapeutic crisis intervention (eclectic, pan‐theoretical and flexible) a | Up to 15 weekly sessions over 3 weeks on the inpatient ward and up to 5 further follow‐up sessions over 6 months delivered at a clinic or via telephone | 7 therapists; psychiatrists, psychotherapists/psychologists | Not reported |

| 12. Rufino and Ellis (2018) | USA | Cohort/Longitudinal | People with diagnoses related to mood, anxiety and/or PD and suicidal thoughts and admitted to an inpatient ward | 434 | 33.44 | 91.00% Caucasian; 53.5% female | Individual therapy; psycho‐educational and therapeutic groups; family therapy a | Sessions delivered on an inpatient ward c | Not reported | Not reported |

| 13. Ibrahim et al. (2018) d | USA | Two‐armed RCT; active control | People who were experiencing depression and suicidal thoughts recruited from a mix of clinical and non‐clinical settings |

Total: 115 Attachment‐based family therapy: 60 |

Total: 14.96 | Total: 28.70% Caucasian; 82.9% female | Attachment‐based family therapy: 90‐min individual and family therapy sessions | 16 weekly sessions over 16 weeks delivered at a university research lab/intervention clinic | 17 therapists; all at least master's level | Not reported |

| Active Control: 55 |

Active control: Family‐enhanced non‐directive supportive therapy Individual a sessions and 4 60‐min parent psycho‐educational sessions |

|||||||||

| 14. Haddock et al. (2019) | UK | Two‐armed RCT; TAU control | People with experiencing of suicidal thoughts and/or behaviours and admitted to an inpatient ward | 24 | 33.88 | 91.67% Caucasian; 58% female | Cognitive behavioural suicide prevention therapy: Up to 70‐min individual sessions | 20 sessions delivered over 6 months on an inpatient ward and followed up in the community | 2 therapists; both clinical psychologists who met the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies minimum standards for CBT accreditation | Weekly supervision |

| 15. Johnson et al. (2019) | USA | Two‐armed RCT; active control | Veterans who had recently attempted suicide and recently discharged from an inpatient ward |

Total: 134 Suicide‐focused assessment group therapy: 69 |

Total: Not reported Suicide Focused Assessment Group Therapy: 47.72 | 70.90% Caucasian; 11.9% female | Suicide‐focused assessment group therapy: Group sessions a | Suicide‐focused assessment group therapy: Up to 12 weekly sessions delivered in an outpatient setting | 2 therapists facilitated both group therapies; 1 clinical psychologist and 1 social worker | Observation and spot checks by the principal investigator ensured adherence and fidelity to suicide‐focused assessment group therapy |

| Active control: 65 | Active control: 48.33 |

Active control: Usual assessment group therapy Group sessions a |

Active control: Up to 12 weekly sessions delivered in an outpatient setting | |||||||

| 16. Ryberg et al. (2019) | Norway | Two‐armed RCT; active control | People with ongoing suicidal ideation, intent, and behaviour in both inpatient and outpatient settings |

Total: 78 Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS): 37 |

Total: 39.90 CAMS: 38.40 |

Not reported; 53% female | CAMS with psychodynamic, cognitive or eclectic psychotherapy: Up to 60‐min individual sessions | CAMS: A mean of 17.80 therapy sessions were attended weekly, of which 7.90 were CAMS specific. Therapy sessions were delivered in inpatient and outpatient settings. Number of sessions not predetermined | 43 therapists; CAMS: 8 psychologists and 1 psychiatrist | CAMS: Once therapists were adherent to the CAMS procedure, supervision was available by request |

| Active control: 41 | Active control: 33.70 | Active control: Psychodynamic, cognitive or eclectic psychotherapy up to 45‐min individual sessions | Active control: A mean of 14.6 weekly sessions delivered in inpatient and outpatient settings. Number of sessions not predetermined | Active control: 15 psychologists, 4 residents, 6 psychiatrists and 9 psychiatric nurses | Active control: Not reported | |||||

| 17. Stratton et al. (2020) | Canada | Two‐armed RCT; waitlist control | People with diagnosis of BPD; suicidal behaviour and NSSI in an outpatient setting | 43 | 27.29 | Not reported; 83.3% female | DBT skills: 120‐min group | 20 weekly sessions delivered at a teaching hospital | 5 therapists; 2 PhD, 3 MSW | Weekly group supervision |

| 18. Huggett et al. (2021) | UK | Two‐armed RCT; TAU control | People with non‐affective psychosis‐related diagnoses; suicidal ideation and/or behaviour in both inpatient and outpatient settings | 64 | 36.83 | 88% Caucasian; 43.75% female | Cognitive behavioural suicide prevention therapy: Up to 180‐min individual sessions | Up to 24 sessions delivered over 6 months in outpatient and inpatient settings | 8 individuals who were clinical psychologists, mental health nurses and a social worker and met the British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies minimum standards for CBT accreditation | Weekly group supervision, monthly individual supervision, and regular peer supervision to ensure and monitor therapy fidelity |

| 19. Ibrahim et al. (2021)d | USA | Two‐armed RCT; active control | People who were experiencing depression and suicidal thoughts recruited from a mix of clinical and non‐clinical settings | 118 | 14.96 | 28.7% Caucasian; 81.7% female | Attachment‐based family therapy: 90‐min individual and family therapy sessions | Up to 16 weekly sessions over 16 weeks delivered at a university research lab/intervention clinic | 17 therapists; all at least master's level | Weekly supervision, which included live supervision and review of therapy tapes |

|

Active control: Family‐enhanced nondirective supportive therapy Individual a sessions and 4 60‐min parent psychoeducation sessions |

||||||||||

Length of sessions not reported.

Setting not reported.

Number of sessions not reported.

Used the same RCT sample.

3.3. Measures of the therapeutic alliance and suicidal experiences

It is worth considering first ways in which the therapeutic alliance was measured and second ways in which suicidal experiences were measured and documented across studies (see Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Details of the therapeutic alliance, suicidal ideation and suicide attempt measures used in included studies

| Therapeutic alliance measure | Suicidal experiences measures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study number and reference | Client rated | Therapist rated | Observer rated | Suicidal ideation measure | Suicide attempt measure |

| 1. Shearin and Linehan (1992) |

Structural Analysis of Social Behaviour INTREX form (Benjamin, 1988) Rated session by session, weekly, Sessions 1–31 (early–mid therapy) |

Structural Analysis of Social Behaviour INTREX form (Benjamin, 1988) Rated session by session, weekly, Sessions 1–31 (early–mid therapy) |

N/A | Measured using a daily diary card | Measured using a daily diary card |

| 2. Turner (2000) |

Helping Relationship Questionnaire (Haq; Luborsky, 1984) Rated at 6 months (mid‐therapy) |

N/A | N/A | Beck Suicidal Ideation Scale (Beck et al., 1988) Measured at baseline, 6 and 12 months (pre‐, mid‐ and end of therapy) | Target behaviour ratings—frequency of parasuicide |

| 3. Goldman and Gregory (2009) | N/A | N/A |

Working Alliance Inventory Observer Short form (WAI‐O‐S; Tichenor & Hill, 1989; Tracey & Kokotovic, 1989) Rated at baseline, 3, 6 9 and 12 months (early, mid and end of therapy) |

N/A |

The Lifetime Parasuicide Count (Linehan & Comtois, 1996) Measured at baseline, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months (pre‐, mid‐ and end of therapy) |

| 4. Hirsh et al. (2012) |

Working Alliance Inventory (WAI; Horvath & Greenberg, 1989) Rated at baseline, 4, 8 and 12 months (early, mid and end of therapy) |

N/A | N/A | N/A |

Suicide Attempt Self‐Injury Interview (Linehan et al., 2006) Measured at baseline, 4, 8 and 12 months (pre‐, mid‐ and end of therapy) |

| 5. Bryan et al. (2012) |

The Therapeutic Bond Scale (CelestHealth Solutions, 2008) Rated after session 1 (early in therapy) |

N/A | N/A |

1 item from the Behavioral Health Measure‐20 (Kopta & Lowry, 2002) Measured session‐by‐session |

N/A |

| 6. Perry et al. (2013) |

The Psychosocial Treatment Interview (PTI; Steketee et al., 1997) Measured every 6 months (early, mid and end of therapy) |

N/A |

Therapeutic Alliance Analogue Scales (Brysk, 1987) Rated 3 sessions around 1 months and 6 months (early in therapy) |

Longitudinal Interval Follow‐up Evaluation (Keller et al., 1987) Adapted for the Study of Personality (Perry, 1990) measured at baseline and every 6–12 months (pre‐, mid‐ and end of therapy) |

N/A |

| 7. Tsai et al. (2014) |

WAI (Horvath & Greenberg, 1986; Horvath & Greenberg, 1989) Rated after Sessions 1 and 5 (early and mid‐therapy) |

N/A | N/A | Number of participants with recurring or current ideation at baseline | Number of participants who had previously attempted suicide at baseline |

| 8. Bedics et al. (2015) |

California Psychotherapy Alliance Scale (Gaston, 1991) Rated after Session 1 and at 4, 8 and 12 months (early, mid and end of therapy) |

California Psychotherapy Alliance Scale (Gaston, 1991) Rated after Session 1 and at 4, 8 and 12 months (early, mid and end of therapy) |

N/A | N/A |

Suicide Attempt Self‐Injury Interview (Linehan et al., 2006) Measured at baseline, 4, 8 and 12 months (pre‐, mid‐ and end of therapy) |

| 9. Gysin‐Maillart et al. (2016) a |

Penn Haq–German version (Bassler et al., 1995; Luborsky, 1984) Rated after Sessions 1 and 3 (early and end of therapy) |

N/A | N/A |

Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSS) German version (Beck & Steer, 1991; Fidy, 2008) Measured at baseline, 6, 12, 18 and 24 months (pre‐therapy and follow‐up time points) |

Demographic question and hospital records |

| 10. Gysin‐Maillart et al. (2017) a |

Penn Haq–German version (Bassler et al., 1995; Luborsky, 1984) Rated after Sessions 1 and 3 (early and end of therapy) |

N/A | N/A |

BSS German version (Beck & Steer, 1991; Fidy, 2008) Measured at baseline, 6 and 12 months (pre‐therapy and follow‐up time points) |

BSS German version (Beck & Steer, 1991; Fidy, 2008) Measured at baseline, 6 and 12 months (pre‐therapy and follow‐up time points) |

| 11. Plöderl et al. (2017) |

WAI–Short Revised German Translation (Wilmers et al., 2008) Rated at intake and discharge from the inpatient ward (early and towards the end of therapy) |

N/A | N/A |

BSS (Beck & Steer, 1991) Measured at intake and discharge from the inpatient ward (early and towards the end of therapy) |

BSS (Beck & Steer, 1991) Measured at intake and discharge from the inpatient ward (early and towards the end of therapy) |

| 12. Rufino and Ellis (2018) |

WAI (Horvath & Greenberg, 1989) Rated at admission, every 2 weeks and prior to discharge (early, mid and end of therapy) |

N/A | N/A |

Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (Posner et al., 2011) Suicide Cognitions Scale (Bryan et al., 2014; Ellis & Rufino, 2015) Measured at admission, every 2 weeks and prior to discharge (early, mid and end of therapy) |

Frequency of prior suicide attempts measured at admission to the inpatient ward (early in therapy) |

| 13. Ibrahim et al. (2018) a |

Therapeutic Alliance Quality Scale (Riemer et al., 2012) Rated session by session on a weekly basis, between Sessions 1 and 16 (early, mid and end of therapy) |

N/A | N/A |

Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire–Junior weekly (Reynolds & Mazza, 1999) Measured at baseline (pre‐therapy) |

Suicide attempt history measured at baseline (pre‐therapy) |

| 14. Haddock et al. (2019) |

WAI (Horvath & Greenberg, 1989) Rated at Session 4 and end of therapy (early and end of therapy) |

WAI (Horvath & Greenberg, 1989) Rated at Session 4 and end of therapy (early and end of therapy) |

N/A |

BSS (Beck et al., 1979) and Suicide Probability Scale (Cull & Gill, 1982) Measured at baseline, 6 week and 6 months (pre‐therapy, early therapy, and end of therapy) |

Frequency of suicide attempts collected by a review of clinical records between randomization and 6 months (start to end of therapy) |

| 15. Johnson et al. (2019) |

WAI‐S (Hatcher & Gillaspy, 2006) Rated at 1 and 3 months (early and end of therapy) |

N/A | N/A |

BSS (Beck et al., 1979) Measured at baseline, 1 month and 3 months (pre‐therapy, early therapy, and end of therapy) |

Suicide Attempt and Self‐Injury Count (Linehan & Comtois, 1999) Measured at baseline, 1 month and 3 months (pre‐therapy, early therapy and end of therapy) |

| 16. Ryberg et al. (2019) |

WAI‐S (Hatcher & Gillaspy, 2006) Rated after 3 weeks of therapy (early in therapy) |

N/A | N/A |

BSS (Beck et al., 1997) Measured at baseline, 6 and 12 months (pre‐therapy and follow‐up time points) |

N/A |

| 17. Stratton et al. (2020) |

Group Session Rating Scale (GSRS; Duncan & Miller, 2007) Rated at baseline, 5, 10, 15 and 20 weeks and 3 months post‐intervention (pre‐therapy early, mid and end of therapy and follow up) |

N/A | N/A | N/A |

Lifetime Suicide Attempt and Self‐Injury Interview (Linehan & Comtois, 1996) Measured at baseline, 5, 10, 15 and 20 weeks and 3 months post‐intervention (pre‐therapy early, mid and end of therapy and follow‐up) |

| 18. Huggett et al. (2021) |

WAI‐SR (Hatcher & Gillaspy, 2006) Rated at Session 4 (early in therapy) |

WAI‐SR (Hatcher et al., 2020) Measured at Session 4 (early in therapy) |

N/A |

Adult Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (ASIQ; Reynolds, 1991) Measured at baseline and end of therapy (pre‐therapy and end of therapy) |

Self‐reported frequency of Suicide Attempts over the previous 6 months measured at baseline and end of therapy (pre‐therapy and end of therapy) |

| 19. Ibrahim et al. (2021) a |

Therapeutic Alliance Quality Scale (Riemer et al., 2012) Rated at Session 4 (early in therapy) |

N/A | N/A |

Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire–Junior weekly (Reynolds & Mazza, 1999) Measured at 16 weeks (end of therapy) |

N/A |

Used the same RCT sample.

First, the most frequently used measure of therapeutic alliance was the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI; Horvath & Greenberg, 1989). The WAI was used in 10 studies, two of which measured both client and therapist perspectives; seven of which sampled client perspectives only; and one of which sampled independent observer ratings of client–therapist alliance. The remaining nine studies captured the client perspective of the therapeutic alliance by using seven different measures other than the WAI. Further, two studies used two different measures other than the WAI to capture the therapist perspectives of the alliance. The final study used an independent observer rated measure to assess the client and therapist alliance (Perry et al., 2013). It is important to consider who collects the therapeutic alliance measures from clients. This is because clients may not want to be seen as being critical of the therapist, which could impact on the quality of intervention delivery and therapeutic outcome (Lingiardi et al., 2016). Of the 19 studies in the current review, 17 measured client perspectives of the therapeutic alliance, with five out of those 17 being administered by independent researchers. Furthermore, two studies used independent observer ratings of therapy session video or audio recordings. Studies ranged from measuring the therapeutic alliance at one time point, that is, Session 1 (Bryan et al., 2012) or after 3 weeks (Ryberg et al., 2019) or 6 months (Turner, 2000), through to measurements taken across 16–31 session‐by‐session ratings using two therapeutic alliance measures (Ibrahim et al., 2018; Shearin & Linehan, 1992).

Second, there was considerable variability in measures of suicidal experiences. The Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (Beck et al., 1988) was the most commonly used validated self‐report measure of suicidal experiences, whereas several different validated interview‐based measures and non‐validated measures were also used. Although some measures have the capacity to measure both suicidal ideation and self‐harm in addition to suicide attempts, it should be noted that most studies treated such variables as separate during the analysis in relation to the therapeutic alliance. However, the Suicide Probability Scale (SPS; Cull & Gill, 1982), which assessed a combination of suicidal ideation, negative thoughts, hopelessness and hostility, was used and analysed as a composite measure in one study (Haddock et al., 2019). Two studies included a population of adolescents and so used the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire–Junior to examine suicidal ideation (Ibrahim et al., 2018, 2021).

Third, suicidal experiences were measured at several time points, including prior to taking part in psychotherapy (e.g. measured at baseline or admission to a mental health inpatient ward), during psychotherapy (e.g. measured session‐by‐session or early and mid‐therapy), towards the end or upon cessation of psychotherapy and at follow‐up time points.

3.4. The relationship between the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy and suicidal experiences

This review focuses upon understanding the extent to which (1) suicidal experiences occurring pre‐therapy influenced the therapeutic alliance, (2) suicidal experiences are correlated with/related to the therapeutic alliance at the same time point during psychotherapy and (3) the therapeutic alliance developed during therapy affected suicidal experiences post‐therapy or at therapy cessation.

3.5. Suicidal experiences pre‐therapy as a predictor of the therapeutic alliance

A summary of analyses used and statistics produced by studies which examined suicidal experiences pre‐therapy as a predictor of the therapeutic alliance is presented in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Details of analyses used and statistics produced in included studies which examined suicidal experiences pre‐therapy as a predictor of the therapeutic alliance

| Suicidal experiences pre‐therapy as a predictor of the therapeutic alliance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study number and reference | Suicidal ideation pre‐therapy as a predictor of the therapeutic alliance | Suicide attempts pre‐therapy as a predictor of the therapeutic alliance | Change in suicidal ideation and behaviour combined as a predictor of change in the therapeutic alliance | Suicide attempts as a predictor of change in the therapeutic alliance over time |

| 1. Shearin and Linehan (1992) | N/A | N/A |

Time series Client χ2(8) = 29.46, p < .001 Therapist χ2(8) = 25.68, p < .001 |

N/A |

| 3. Goldman and Gregory (2009) | N/A |

Spearman's correlation Client r = −.04, p = .925 |

N/A | N/A |

| 7. Tsai et al. (2014) |

Independent samples t‐test Client Session 1: t = −.422, df = 59, p = .674 Session 5: t = −1.23, df = 50, p = .225 |

Independent samples t‐test Client Session 1: t = .439, df = 58, p = .662 Session 5: t = .388, df = 49, p = .700 |

N/A | N/A |

| 10. Gysin‐Maillart et al. (2017) | N/A |

Bivariate correlations Client Session 1: r = −.34, p = .008 Session 3: r = −.13, p = .340 |

N/A | N/A |

| 11. Plöderl et al. (2017) | N/A |

Wilcoxon test Client Previous suicide attempt: M = 46.70 No previous suicide attempt: M = 48.59 W = 54,697, N = 633, p = .02 |

N/A | N/A |

| 13. Ibrahim et al. (2018) |

Multiple hierarchical linear regression Client β = −.04, p = .07, SE = .03, df = 100, t = −1.38 |

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 14. Haddock et al. (2019) |

Pearson's correlation Client ideation: r = −.222, n = 17, p = .195 Potential: r = −.226, n = 17, p = .192 Therapist ideation: r = .162, n = 22, p = .235 Potential: r = .360, n = 22, p = .050 |

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 15. Johnson et al. (2019) |

Path analysis Client IRR = .73 |

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 17. Stratton et al. (2020) | N/A |

Bivariate correlation r = −.10 |

N/A |

Logistic regression r = −.17 |

| 18. Huggett et al. (2021) |

Pearson's correlation Client r(57) = −.115, p = .386, 99% CI [−.43, 0.23] Therapist r(58) = −.034, p = .794, 99% CI [−.36, 0.30] a |

Independent samples t‐test Client t(56) = −2.46, p = .023, 99% CI [−10.69, 0.36] Therapist t(57) = −1.34, p = .186, 99% CI [−5.51, 2.21] a |

N/A | N/A |

The authors amended the alpha level to .01 to minimize the probability of a Type 1 error occurring and to correct for multiple testing.

3.6. Suicidal ideation pre‐therapy as a predictor of the therapeutic alliance

Four studies consistently found that experience of suicidal ideation prior to psychotherapy was not significantly related to (Haddock et al., 2019; Huggett et al., 2021) and did not significantly predict (Ibrahim et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2019) client perceptions of the therapeutic alliance at Session 4 or 1 month into therapy. A fifth study found that for people with and without suicidal ideation prior to therapy, there were no significant differences between alliance scores at Session 1 and Session 5 of psychotherapy (Tsai et al., 2014). A non‐significant relationship was also observed between a measure of suicide potential pre‐therapy and client therapeutic alliance at Session 4 (Haddock et al., 2019). Thus, the current evidence indicated that suicidal ideation prior to therapy did not significantly influence client perceptions of the therapeutic alliance early on in therapy.

Similarly, in two studies, suicidal ideation prior to therapy was not significantly related to therapist perceptions of the therapeutic alliance at Session 4 (Haddock et al., 2019; Huggett et al., 2021). Conversely, there was a moderate significant positive relationship between self‐reported suicide potential prior to therapy and the therapist view of the therapeutic alliance at Session 4, even though the sample size was small (Haddock et al., 2019). Hence, the evidence from this study suggests that clients with greater self‐reported suicide potential, which involved experiences of suicidal thoughts, hopelessness, negative self‐evaluations and hostility, were perceived by therapists as forming a stronger therapeutic alliance early on in therapy. This is despite a measure of suicidal ideation prior to therapy not relating to therapist views of the therapeutic alliance across two studies.

3.7. Suicide attempts pre‐therapy as a predictor of the therapeutic alliance

Six studies examined the extent to which lifetime suicide attempts or suicide attempts in the previous 6 months influenced the formation and maintenance of the therapeutic alliance from the perspective of the client or an observer. One study suggested that client perceptions of the therapeutic alliance at Session 1, which was held on admission to a mental health inpatient ward, were significantly lower in people who had previously attempted suicide compared to those who had not attempted suicide (Plöderl et al., 2017). In a second study, there was a moderate negative significant relationship between the number of suicide attempts prior to psychotherapy and therapeutic alliance measured at the first psychotherapy session (Gysin‐Maillart et al., 2017), but by the third session, this negative relationship had diminished. Notably, only three or four sessions were offered as part of this specific psychotherapy.

However, in two studies, there was a non‐significant relationship between number of suicide attempts prior to group psychotherapy and therapeutic alliance measured in Session 1 (Stratton et al., 2020; Tsai et al., 2014) and Session 5 (Tsai et al., 2014). In a third study, frequency of lifetime suicide attempts at baseline had no relationship with the therapeutic alliance after 3 months of psychotherapy (Goldman & Gregory, 2009). Furthermore, a fourth study found no evidence to suggest a significant difference in client nor therapist perceptions of the therapeutic alliance when clients had previously attempted suicide or not (Huggett et al., 2021).

In summary, clients who have attempted suicide prior to commencing psychotherapy have varied perceptions of the robustness of the therapeutic alliance at the first session but are still able to form a good therapeutic alliance with a psychotherapist at the outset of therapy.

3.8. Change in suicidal ideation and behaviour combined as a predictor of change in the therapeutic alliance

One study analysed suicidal ideation and behaviour as a composite variable (Shearin & Linehan, 1992). A time series approach was taken to analysing the session‐by‐session data over 7 months of psychotherapy. Experiences of the composite measure of suicide during therapy were significantly associated with client perceptions that the therapists were understanding and warm in the following week's therapy session (Shearin & Linehan, 1992).

3.9. Suicide attempts as a predictor of change in the therapeutic alliance over time

One study implicitly examined lifetime frequency of suicide attempts prior to group psychotherapy and whether this was related to change in the client perception of the therapeutic alliance over time (Stratton et al., 2020). Lifetime frequency of suicide attempts did not significantly correlate with change in therapeutic alliance over the course of group psychotherapy (Stratton et al., 2020).

3.10. Suicidal experiences as a correlate of the therapeutic alliance at the same time point during psychotherapy

A summary of analyses used and statistics produced by studies which examined suicidal experiences as a correlate of the therapeutic alliance at the same time point during psychotherapy is presented in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Details of analyses used and statistics produced in included studies which examined suicidal experiences as a correlate of the therapeutic alliance at the same time point during psychotherapy

| Suicidal experiences as a correlate of the therapeutic alliance at the same time point during psychotherapy | ||

|---|---|---|

| Study number and reference | Suicidal ideation in relation to the therapeutic alliance at the same time point during therapy | Suicide attempts in relation to the therapeutic alliance at the same time‐point during therapy |

| 3. Goldman and Gregory (2009) | N/A |

Spearman's correlation Client r = .08, p = .851 |

| 6. Perry et al. (2013) |

Wilcoxon test Client 1 month: Z = 1.83, p = .07; Z = 1.70, p = .09 |

N/A |

| 11. Plöderl et al. (2017) |

Spearman's correlation Client Session 1: r = −.19, N = 633, p < .01 Final session: r = −.36, N = 633, p = .01 |

N/A |

3.11. Suicidal ideation in relation to the therapeutic alliance at the same time point during therapy

In the present review, experience of suicidal ideation measured during therapy was cross‐sectionally examined in relation to the therapeutic alliance during psychotherapy by only two studies. From the client's perception of the therapeutic alliance, one study found a small, negative relationship between suicidal ideation and therapeutic alliance at Session 1, which took place on admission to a crisis intervention and suicide prevention inpatient ward (Plöderl et al., 2017). A second study (Perry et al., 2013) found only trends towards a significant difference between the therapeutic alliance ratings, 1 month into psychotherapy again in people with and without suicidal ideation at this time point. Similarly, in the same study, therapist views of the therapeutic alliance (1 and 6 months into psychotherapy) and client views of the therapeutic alliance (6 months into psychotherapy) did not differ dependent on whether the client had or had not experienced suicidal ideation (Perry et al., 2013). Thus, the majority of the evidence indicates that experience of suicidal ideation during psychotherapy did not influence client or therapist perceptions of the therapeutic alliance early on or part way through psychotherapy.

A moderate negative relationship was observed between client perception of the therapeutic alliance and suicidal ideation towards the end of psychotherapy, that is, discharge from the mental health inpatient ward (Plöderl et al., 2017). Such finding suggests that clients who perceived the therapeutic alliance as stronger towards the end of psychotherapy experienced less severe suicidal thoughts.

In summary, the current literature suggests client and therapist perceptions of the therapeutic alliance early on, or part way through psychotherapy, are not related to client experiences of suicidal thoughts. Although, most notably in an inpatient population, towards the end of psychotherapy and final session on inpatient wards, clients who perceived the therapeutic alliance as stronger experienced less severe suicidal ideation.

3.12. Suicide attempts in relation to the therapeutic alliance at the same time point during therapy

In the present review, only one study (Goldman & Gregory, 2009) examined the cross‐sectional relationship between suicide attempts and the therapeutic alliance. The average of the observer‐rated therapeutic alliance had no significant relationship with the total frequency of suicide attempts, both collected over four time points during psychotherapy (Goldman & Gregory, 2009).

3.13. Therapeutic alliance as a predictor of prospective suicidal experiences during and post‐therapy

A summary of analyses used and statistics produced by studies which examined the therapeutic alliance as a predictor of prospective suicidal experiences during and post‐therapy is presented in Table 5.

TABLE 5.

Details of analyses used and statistics produced in included studies which examined the therapeutic alliance as a predictor of prospective suicidal experiences during and post‐therapy

| Therapeutic alliance as a predictor of prospective suicidal experiences during and post‐therapy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study number and reference | Therapeutic alliance in relation to suicidal ideation post‐therapy | Therapeutic alliance as a predictor of prospective suicidal behaviour (e.g. suicide attempts and self‐harm) during and post‐therapy | Therapeutic alliance during psychotherapy in relation to predicting prospective changes in suicidal ideation over time | Therapeutic alliance during psychotherapy in relation to predicting change in suicidal behaviour (e.g. suicide attempts) over time |

| 1. Shearin and Linehan (1992) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Time series Client χ2(8) = 25.68, p < .001 Therapist χ2(8) = 17.26, p < .05 |

| 2. Turner (2000) |

Canonical correlation Alliance: Canonical coefficient = .628 Intervention: Canonical coefficient = .631 Therapy cessation suicidal ideation: Canonical coefficient = .84 |

Canonical correlation Therapy cessation suicide attempts and self‐harm (composite measure) Canonical coefficient = .80 |

N/A | N/A |

| 3. Goldman and Gregory (2009) | N/A |

Predictive correlation r = .36, p = .552 |

N/A | N/A |

| 4. Hirsh et al. (2012) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Multilevel modelling Client b = −.01, SE = .01, t/chi‐square = 2.92 Reduction in suicide attempts b = −.05, SE = .02, t = 10.09, p < .05 |

| 5. Bryan et al. (2012) | N/A | N/A |

Repeated measures mixed linear Regression Client B = .045, SE = .117, p = .702 |

N/A |

| 6. Perry et al. (2013) | N/A | N/A |

Simple linear regression Interactions r s = −.45, n = 28, p = .02 Client r s = −.18, n = 28, p = .38 Therapist r s = −.24, n = 28, p = .24 |

N/A |

| 8. Bedics et al. (2015) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Hierarchical linear modelling Client Changes in alliance b = −.12, SE = .10, z = −1.14, p = .26 Working capacity Suicide‐focused therapy b = −.35, SE = .16, z = −2.39, p < .02 Therapy without focus on suicide prevention b = .02, SE = .13, z = .17, p = .87 Therapist Overall alliance across both therapies b = −.31, SE = .10, z = −3.13, p < .005 Suicide‐focused therapy Overall alliance b = −.34, SE = .14, z = −2.38, p < .02 Client commitment b = −.28, SE = .11, z = −2.56, p < .02 Client working capacity b = −.26, SE = .12, z = −2.26, p < .03 Therapy without focus on suicide prevention Understanding and involvement b = −.43, SE = .14, z = −3.00, p < .003 Overall alliance b = −.27, SE = .14, z = −1.93, p = .05 |

| 9. Gysin‐Maillart et al. (2016) ¶ |

Linear regression Client 12‐month follow‐up: t57 = −3.02, p = .004; coefficient: −.26, R2 = .18 24‐month follow‐up: t57 = −3.11, p = .003; coefficient: −.21, R2 = .30 |

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 10. Gysin‐Maillart et al. (2017) ¶ |

Stepwise multiple linear regression Client β = −.334, R2 = .386, p = .004 |

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 11. Plöderl et al. (2017) | N/A | N/A |

Spearman's correlation (change score calculated as difference pre and post) Client r = .05, p = .23 |

N/A |

| 15. Johnson et al. (2019) | N/A | N/A |

Structural equation modelling Client IRR = 1.04, p = .001 |

N/A |

| 16. Ryberg et al. (2019) | N/A | N/A |

Mixed effects linear regression Overall alliance 6‐month follow‐up: β = .38, N = 78, p = .039 Client–therapist bond 6‐month follow‐up β = .1.47, N = 78, p = .003 12‐month follow‐up β = 1.10, N = 78, p = .029 |

N/A |

| 18. Huggett et al. (2021) |

Pearson's correlation Client r(58) = −.22, p = .087, 99% CI [−.51, .11] Therapist r(58) = −.22, p = .087, 99% CI [−.51, .11] Multiple hierarchical linear regression Client Model 1: β = −.33, t(56) = −2.66, p = .010, 95% CI [−2.64, −.37] R2 = .110, p = .010 for Step 1 Model 2: β = −.28, t(55) = −2.51, p = .015, 95% CI [−2.29, −.26] R2 = .231, p = .001 for Step 1; ΔR2 = .078, p = .015 for Step 2 Model 3: β = −.27, t(53) = −2.34, p = .023, 95% CI [−2.23, −.18] R2 = .231, p = .001 for Step 1; ∆R2 = .037, p = .261 for Step 2; ∆R2 = .068, p = .023 for Step 3. WAI‐SR Moderated linear regression Client Interaction effect: b = .003, t(54) = 1.85, p = .07 Total number of minutes spent in therapy Short: b = −2.07, 95% CI [−3.40, −.74], t = −3.12, p = .003 Mean: b = − 1.14, 95% CI [−2.18, −.11], t = −2.20, p = .032 Long: = − .21, 95% CI [−1.76, 1.34], t = −.59, p = .560 |

Independent samples t‐test Client t(55) = −.72, p = .463, 99% CI [−9.62, 6.64] Therapist t(56) = .63, p = .529, 99% CI [−4.68, 6.36] |

N/A | N/A |

| 19. Ibrahim et al. (2021) |

Hierarchical linear models Interaction between therapy adherence and client alliance in relation to suicidal ideation t (329) = −2.72, p < .01 ∆R2 = .02, ∆F (3, 329) = 2.80, p = .04 |

N/A | N/A | N/A |

3.14. Therapeutic alliance in relation to suicidal ideation post‐therapy

Six studies examined the therapeutic alliance as perceived by the client in relation to suicidal ideation towards the end of psychotherapy or upon psychotherapy cessation and at follow‐up time points.

First, there were significant negative relationships between the therapeutic alliance early on in therapy and suicidal ideation, across three studies, at therapy cessation (Huggett et al., 2021), 6‐month follow‐up (Gysin‐Maillart et al., 2017), 12‐month follow‐up (Gysin‐Maillart et al., 2016; Gysin‐Maillart et al., 2017) and 24‐month follow‐up (Gysin‐Maillart et al., 2016). These findings remained when baseline confounding variables were controlled for, that is, suicidal ideation, depression and hopelessness (Huggett et al., 2021) and depression and the number of previous suicide attempts (Gysin‐Maillart et al., 2017).

A fourth study analysed the simultaneous impact of the therapeutic alliance and intervention upon suicidal ideation. Both the therapeutic alliance measured mid‐way (6 months) through therapy and difference between the intervention groups, that is, DBT and client‐centred therapy had a similar relationship with lower severity of suicidal ideation upon therapy cessation (Turner, 2000).

A fifth study investigated the therapeutic alliance as a moderator between therapy adherence and suicidal ideation upon therapy cessation. The interaction between good therapy adherence and the client perception a stronger therapeutic alliance was significantly correlated with lower frequency of suicidal thoughts (Ibrahim et al., 2021).

In contrast, a sixth study indicated that client perception of the therapeutic alliance measured early on in therapy was not significantly correlated to suicidal ideation upon therapy cessation when discharged from the inpatient ward and at 2 weeks and 6 months' post‐discharge (Rufino & Ellis, 2018). Furthermore, there was no evidence for a significant relationship between therapist views of the alliance and suicidal ideation upon therapy cessation (Huggett et al., 2021).

Overall, there is evidence to suggest that a more robust therapeutic alliance perceived by the client early on or mid‐way through a suicide‐focused psychotherapy may be related to less severe or less frequent suicidal ideation both at the end of therapy and at follow‐up time points, although this finding was not supported by all included studies.

3.15. Therapeutic alliance as a predictor of prospective suicidal behaviour (e.g. suicide attempts and self‐harm) during and post‐therapy

Three studies examined the relationship between the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy and suicidal behaviour post‐therapy (Goldman & Gregory, 2009; Turner, 2000). The first study (Goldman & Gregory, 2009) found that the observer‐rated therapeutic alliance at 3 months did not significantly relate to suicide attempts mid‐way (6 months) through psychotherapy. Additionally, the second study suggested there were no significant differences in client nor therapist perceptions of the therapeutic alliance when clients had previously attempted suicide or not (Huggett et al., 2021). In contrast, the third study (Turner, 2000) found that client perceptions of the therapeutic alliance as stronger, at the mid‐way point (6 months) during therapy, were as important as the type of therapy (DBT or client‐centred therapy) being delivered, in terms of explaining the impact on suicidal behaviour outcome post‐therapy (composite measure of suicide attempts and self‐harm).

In summary, studies examining client‐, therapist‐ and observer‐rated therapeutic alliance have contradictory findings as to whether the therapeutic alliance is related to subsequent suicide attempts.

3.16. Therapeutic alliance during psychotherapy in relation to predicting prospective changes in suicidal ideation over time

Five studies examined to what extent the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy predicted changes in suicidal ideation over time (Bryan et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2019; Perry et al., 2013; Plöderl et al., 2017; Ryberg et al., 2019). All five studies described the method used to calculate rate of change scores.

One study provided evidence that observer ratings of a strong therapeutic alliance at 6 months into therapy resulted in reduced suicidal ideation. An observer rating of one component of the therapeutic alliance, namely, interactions between the client and therapist (e.g. collaborative discussions and establishing a rapport), had a medium negative significant relationship with frequency of suicidal ideation over a median duration of 4.19 years (Perry et al., 2013). In other words, if client–therapist interactions were rated as strong by observers, there was a greater reduction in suicidal ideation over time. However, such a relationship was not reported for client or therapist perceptions of the therapeutic alliance overall, respectively.

A second study suggested that a strong therapeutic alliance early on in therapy moderated the relationship between type of psychotherapy and severity of suicidal ideation at follow‐up time points (Ryberg et al., 2019). More specifically, interactions between the overall therapeutic alliance and psychotherapy condition were significantly related to reductions in severity of suicidal ideation at 6‐month follow‐up. Similarly, an interaction between one component of the therapeutic alliance, the client–therapist bond and psychotherapy condition was significantly related to improvement in suicidal ideation at both 6‐month and 12‐month follow‐up.

In contrast, a third study found that a one unit increase in the strength of the client perception of the therapeutic alliance at 1 month was significantly related to a 4% increase in severity of suicidal ideation at the same time point (Johnson et al., 2019). However, changes in the therapeutic alliance from 1 month to therapy cessation at 3 months were not related to changes in suicidal ideation severity at the end of therapy.

A fourth study indicated that the client perception of the therapeutic alliance measured early on in psychotherapy did not significantly influence subsequent changes in suicidal ideation after two to eight sessions of psychotherapy (Bryan et al., 2012), although one may question if such a number of sessions is sufficient when working with suicidal clients. A fifth study also observed no such relationship between client view of the early therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy delivered on a mental health inpatient ward and changes in severity of suicidal ideation over the course of up to 15 sessions of psychotherapy (Plöderl et al., 2017).

To summarize, no firm conclusions can be made as to whether the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy predicts change in suicidal ideation over time.

3.17. Therapeutic alliance during psychotherapy in relation to predicting change in suicidal behaviour (e.g. suicide attempts) over time

Three studies investigated whether the therapeutic alliance during psychotherapy predicted change in suicidal behaviour over time (Bedics et al., 2015; Hirsh et al., 2012; Shearin & Linehan, 1992). All three studies reported analyses which were used to examine change in suicidal attempts/behaviour over time.

One study examined the therapeutic alliance in two types of psychotherapy; more specifically, one was suicide focused, and one not exclusively focused on reducing suicidal thoughts and behaviours (Bedics et al., 2015). For all clients, regardless of psychotherapy received, changes in the therapeutic alliance did not significantly predict changes in frequency of suicide attempts. However, there appeared to be a trend towards an interaction, whereby for clients who received a suicide‐focused psychotherapy, there was a significant negative relationship between clients' perception of their working capacity and frequency of suicide attempts over the course of 12 months of therapy (Bedics et al., 2015). This indicates that as perceptions of working capacity increased, subsequent suicide attempts reduced. However, there was no such relationship for clients who received psychotherapy without a focus upon suicide prevention. Moreover, no other aspect of the therapeutic alliance was significantly related to suicide attempts, for example, client commitment, therapist understanding and involvement and agreement on working strategy (Bedics et al., 2015). Additionally, a second study (Hirsh et al., 2012) found that the client view of the therapeutic alliance was not significantly related to frequency of suicide attempts over 1 year of psychotherapy. This result occurred even though suicide attempts significantly reduced over the same time period (Hirsh et al., 2012).

When considering therapist perceptions of the therapeutic alliance, irrespective of whether or not therapy was suicide focused, overall perception of the therapeutic alliance and each component of the therapeutic alliance (client working capacity, client commitment, working strategy consensus and therapist understanding and involvement) had significant negative relationships with suicide attempts over 1 year of psychotherapy (Bedics et al., 2015). Furthermore, such relationships were further scrutinized for therapies with and without a specific focus on suicide prevention, respectively. For therapists who delivered a suicide‐focused therapy, it appeared that the overall therapeutic alliance, along with client commitment and client working capacity, had a significant negative relationship with suicide attempts over 1 year of psychotherapy (Bedics et al., 2015). Therapists' perception of their understanding and involvement was not related to frequency of client suicide attempts for therapists conducting suicide‐focused therapy. However, when therapists provided a therapy which was not specifically focused on suicide prevention, an increase in therapist perception of their understanding and involvement and overall perception of the alliance significantly predicted a reduction in suicide attempts over 1 year of psychotherapy (Bedics et al., 2015).

Similarly, a third study found that improvements in both client and therapist perceptions of the therapeutic alliance were associated with a significant reduction in suicidal behaviour over 7 months of psychotherapy (Shearin & Linehan, 1992). However, the definition of suicidal behaviour in this study (Shearin & Linehan, 1992) was not provided.

The current literature tentatively suggests that one component of the client perception of the therapeutic alliance (working capacity) and therapist perceptions of the overall therapeutic alliance predict a reduction in subsequent suicide attempts over the course of psychotherapy. Additionally, the results of one study demonstrate that different components of the therapist‐rated therapeutic alliance (i.e. therapist understanding and involvement, client commitment and client working capacity) were related to a reduction in suicide attempts when therapists used different therapeutic modalities.

3.18. Study quality

Across studies, four scored affirmatively for six or seven of the seven CASP criteria (Gysin‐Maillart et al., 2016, 2017; Hirsh et al., 2012; Huggett et al., 2021), whereas two only scored one or two, respectively (Rufino & Ellis, 2018; Shearin & Linehan, 1992; see Table 6). It was noticeable that those studies which met between six and seven out of seven criteria for study quality were most likely to be RCTs and had an outpatient population and used validated measures of alliance and suicidal experiences. Six studies adopted a cohort design, whereas RCTs were used to collect data for the other 13 studies. Inherently, cohort studies are not as robust as RCTs in minimizing bias (Levin, 2006, 2007). Most studies (n = 16) had acceptable outcome measure retention rates or accounted for attrition in the analysis to mitigate against attrition bias. Overall, the majority of studies appeared to be of good methodological quality, with 14 of the 19 studies meeting at least four out of seven criteria.

TABLE 6.

Quality assessment for included studies

| CASP question | 1. Did the trial address a clearly focused issue? | 2. Was the exposure accurately measured to minimize bias? | 3. Was the outcome accurately measured to minimize bias? | 4. Have authors identified all important confounding factors? | 5. Was the follow‐up of subjects complete enough? | 6. Can the results be applied to the local population? | 7. Are the benefits worth the harms and costs? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|