Abstract

Since the 1990s, the sociology of rationing has developed in explicit opposition to health economic and bioethical approaches to healthcare rationing. This implies a limited engagement with other disciplines and a limited impact on political debates. To bring the sociology of rationing into an interdisciplinary dialogue, it is important to understand the disciplines' analytical differences and similarities. Based on a critical interpretive literature synthesis, this article examines four disciplinary perspectives on healthcare rationing and priority setting: (1) Health economics, which seeks to develop decision models to provide for more rational resource allocation; (2) Bioethics, which seeks to develop normative principles and procedures to facilitate a just allocation of resources; (3) Health policy studies, which focus on issues of legitimacy and implementation of decision models; and lastly (4) Sociology, which analyses the uncertainty of rationing and the resulting value conflicts and negotiations. The article provides an analytical overview and suggestions on how to advance the impact of sociological arguments in future rationing debates: Firstly, we discuss how to develop the concepts and assumptions of the sociology of rationing. Secondly, we identify specific themes relevant for sociological inquiry, including the recurring problem of how to translate administrative priority setting decisions into clinical practice.

Keywords: critical interpretive literature study, distributive justice, interdisciplinary dialogue, priority setting, resource allocation, sociology of rationing

INTRODUCTION: TOWARDS A CONTEMPORARY SOCIOLOGY OF RATIONING

The sociological literature on rationing arose in the 1990s in opposition to the political ideal of letting explicit priority setting inform rationing decisions. In the context of the introduction of the new model for the National Health Services (NHS) in England in 1991 and the introduction of the Oregon Health Plan in the United States in 1994, researchers with sociological and related disciplinary backgrounds raised several concerns about the dominant presentation of explicit priority setting as a viable solution to the problem of allocating finite healthcare resources (Light & Hughes, 2001). They argued, firstly, that while explicit priority setting ensured transparency and legitimacy concerning rationing decisions — rationing decisions that have always been made — they also introduced a particular way of thinking about and managing the distribution of care. This should not be seen as neutral, they argued (Joyce, 2001; Light & Hughes, 2001). Secondly, they problematised the widespread belief in the potential of explicit priority setting in ensuring the transparency of rationing decisions. To the sociological researchers, rationing was — and is — a messy affair (Hunter, 1995) due to the heterogeneity of patient populations, the imperfections of priority setting tools, and the uncertainty involved in medical decision‐making (Mechanic, 1997). They believed that although the reliance on national plans and health economic tools to deal with health care priorities was seductive, it could also be harmful (Griffiths & Hughes, 1998; Hunter, 1995; Mechanic, 1997). Once a strong research programme, the sociology of rationing has yet to define its role in current debates. Political and scholarly debates in the 1990s mainly revolved around whether or not to introduce explicit priority setting schemes, such as the Oregon Health Plan. Contemporary discussions have moved beyond this question and explicit priority setting has, despite the criticisms, become more prevalent (Brousselle & Lessard, 2011; Cromwell et al., 2015). But if explicit priority setting is here to stay, what is the role for a sociological critique?

The establishment of national priority setting agencies in many Western countries, such as The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in England, testifies to the fact that explicit priority setting has become a reality (Brousselle & Lessard, 2011; Cromwell et al., 2015). The role of these agencies is to evaluate medicine and other medical technologies to inform reimbursement decisions and thereby provide for cost‐effective use of healthcare resources. Scholars from different disciplines are currently discussing how to design such evaluation programs and otherwise inform resource allocation decisions: Health economists focus on the development and refinement of evaluation methods and decision models (cf. Hauck et al., 2004; Peacock et al., 2010). Bioethicists consider which principles and deliberative procedures should underpin resource allocation (Cookson & Dolan, 2000; Daniels & Sabin, 2006 [1997]), and policy analysts discuss the institutional preconditions for obtaining public acceptability and successful implementation of rationing decisions (Angell et al., 2016; Pace et al., 2015; Weale et al., 2016). Economic and bioethical perspectives enjoy central positions in debates on priority setting and rationing, with their research agendas attuned to delivering prescriptive decision support. Sociological perspectives have at present a less central position. We believe, however, that critical sociological enquiries into rationing practices can contribute to contemporary debates by elucidating aspects of healthcare rationing that are often overlooked or sidestepped by other disciplines. The question is whether the sociology of rationing should maintain its oppositional approach to healthcare rationing also in the future, or whether it is time to integrate sociological insights prospectively into priority setting and rationing practices.

With this study, we outline the contours of the current debates on priority setting and rationing, and discuss the potential contributions of a contemporary sociology of rationing. Through a critical interpretive literature synthesis (CIS) (Dixon‐Woods et al., 2006), we outline four disciplinary perspectives on priority setting and rationing; health economy, bioethics, healthcare policy and sociology. Following a configurative logic of synthesis (Gough et al., 2012), we explicate and compare the preferred concepts and analytical assumptions of these perspectives. The article offers two contributions. First, we provide what we believe is the first analytical overview of different disciplinary perspectives on rationing and priority setting. The overview can be used as a brief introduction to the discussions and themes occupying different research traditions, and as a means of understanding and handling analytical discrepancies between the disciplines. Second, we provide suggestions on how the sociology of rationing could gain a stronger position in current and future debates on rationing and priority setting. These suggestions concern the analytical toolbox of the sociology of rationing, as well as the identification of themes and areas that could benefit from a critical, sociological inquiry.

METHODS

To scrutinise the conceptual basis of studies of rationing and priority setting in healthcare, we performed a comprehensive literature search and conducted a conceptual analysis, using the CIS approach, which reflects our interest in synthesising methodologically and epistemologically diverse studies. The CIS approach involves scrutiny of the conceptual basis of studies (Dixon‐Woods et al., 2006). The aim is to arrive at conceptualisations that ‘provide enlightenment through new ways of understanding’ a complex phenomenon (Gough et al., 2012, p. 3).

Search strategy and use of concepts

In terms of concepts, the research disciplines included here emphasise either priority setting or rationing. ‘Priority setting’ is typically used in economic and health policy studies to refer to the systematic approach used by policymakers to define what is more and less important (Lauerer et al., 2016). ‘Rationing’ is the concept used by most sociologists and bioethicists, reflecting an interest in the process of distributing resources across organisational and regulatory borders. We develop these analytical nuances of the different concepts in the literature synthesis. However, in the search we treated the terms interchangeably. In the remainder of this article, we refer to priority setting and rationing as PSR for simplicity.

Rather than a quantitatively exhaustive search of all related studies (Gough et al., 2012, p. 3), our aim was to identify studies from various disciplines that could inform our understanding of the analytical differences and convergences among scholarly fields. We began by performing a scoping review in order to (1) ascertain the relevance of our study, that is, examine whether similar review articles had previously been made, and (2) inform the analytical construction of a sampling frame (Dixon‐Woods et al., 2006) from which to identify various disciplines dealing with PSR.

For the scoping review, we searched the following databases: Academic Search Premier, Embase, Socindex, Medline and Econlit. Table 1 provides an overview of search parameters and keywords. For keywords with different possible endings we used truncated search terms (marked by the asterisk (*)) to bring up all versions of the word.

TABLE 1.

Search parameters and keywords

| Search parameters a | Keywords b |

|---|---|

| What | Priori*, rank*, rationi*, resource allocat*, categoriz* |

| Where | Health*, health, care, medic*, pharmaceutic*, treatment*, hospital*, drug* |

| Wh | Decision mak*, policy mak*, administ*, govern*, regulat*, organi* |

Separated by the AND function.

Separated by the OR function.

We specified that ‘review’ OR ‘literature study’ should figure in the title or abstract, and that the language should be English. A full‐text reading of the 14 identified reviews revealed that no studies had previously attempted a cross‐disciplinary analysis of the literature on PSR. For the main literature search, we re‐used the search strategy described above, specifying the format to peer‐reviewed articles and the period to 1990–2019. To achieve our purpose of providing an overview of different disciplinary approaches to PSR, we performed a handheld search to retrieve further studies from the traditions that had yielded few or dispersed results (including sociology). For the handheld search, we used reference lists in already‐retrieved studies, overarching search phrases in Google.scholar (including ‘rationing’) and the related articles function. We retrieved 701 articles through the database and the handheld searches. The total number of included articles from each discipline does not reflect the volume or impact of the discipline. Rather, the choice of inclusion was based upon our aspiration of understanding the conceptual bases of the disciplines. For the established and coherent discipline of economy, this required fewer studies than was the case for particularly sociology, where we needed a relatively high number of hand‐searched articles to gain a sufficiently thorough conceptual understanding of the discipline.

Screening of articles based on relevance and quality

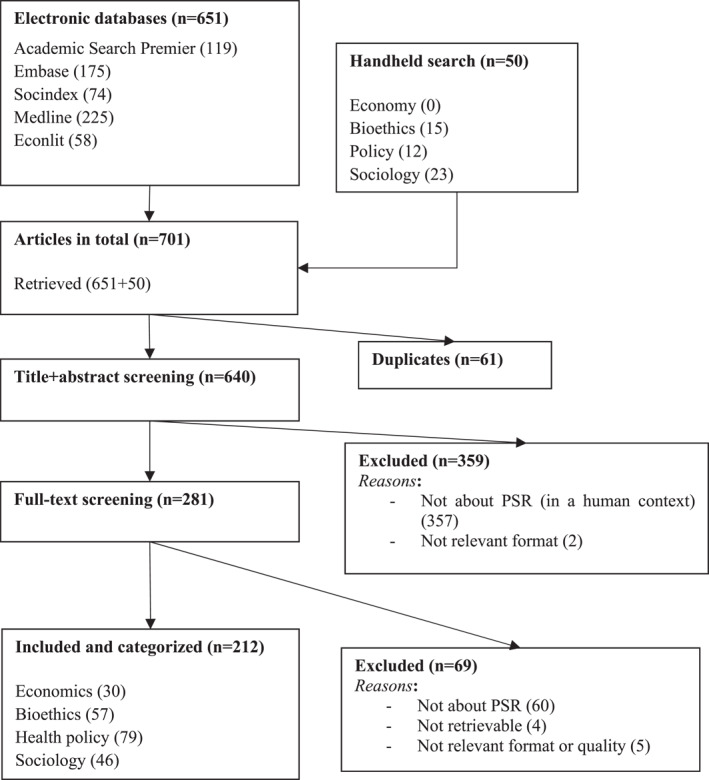

We screened titles and abstracts, and included articles containing: (1) results from empirical studies on (human) health care PSR or (2) theoretical discussions about PSR of health care resources. Whether to, and how to, conduct an appraisal of the quality of studies in interpretive reviews is contested (for thorough discussions, see Walsh & Downe, 2006 or Dixon‐Woods et al., 2006). We have included studies based on their conceptual relevance rather than their methodological rigour, and applied only a few broad quality criteria, namely that the aim and objectives were in line with the analysis undertaken, and that key concepts were specified. In total, we excluded 489 articles because they were duplicates, did not meet our content or quality criteria, were not retrievable, or not of the relevant format. Accordingly, we included 212 articles in the review (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Overview of search and categorisation process

Synthesis

We categorised the studies into four disciplinary perspectives: Economics, bioethics, health policy and sociology. Our categorisation of the studies into the disciplinary perspectives was informed by the institutional affiliation or biographies of the authors of the original studies, the conception of priority setting or rationing advanced in the study, and its primary research agenda. While there are disciplinary overlaps and other disciplines could have been emphasised (e.g. anthropology), these categories allow us to identify and compare dominant approaches to PSR. The categories provide the foundation for an analytical overview rather than an all‐encompassing representation of the different academic fields. For each category, we identified key works as publications with many citations, and/or publications representing what we found to epitomise the discipline's shared agenda and analytical approach in a particularly clear way.

LITERATURE SYNTHESIS: FOUR DISCIPLINARY PERSPECTIVES

The analytical findings for each perspective are condensed as ideal types in Table 2. Below we present the perspectives' analytical approach and research agenda, including their overall conception of PSR and their type of contributions.

TABLE 2.

Ideal typical differences among disciplinary perspectives on PSR

| Economics | Bioethics | Health policy | Sociology | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conception of PSR | A choice situation: Decision‐makers must make trade‐offs between alternatives | An ethical dilemma: Decision‐makers must balance conflicting concerns | A political process: Decision‐makers must manage the interests of multiple stakeholders and foster democratic participation | A social practice: Multiple actors engage in negotiations regarding the appropriateness of specific allocations |

| Main concern | The accountability of formal decision‐makers with budgetary responsibility: Political pressure may prompt irrational choices | The injustice of implicit rationing: Decisions may be biased and discriminatory | The stability of democratic institutions: Illegitimate decisions may prompt public resistance | The unintended effects of applying prescriptive models |

| PSR should take into account: | Preferences: Studies seek to elicit the inclinations of individuals to favour certain distributive outcomes and aggregate these preferences into decision weights | Philosophical positions: Studies seek to identify theoretical conceptions of equity, fairness etc. and operationalise these constructs into decision criteria and procedural principles | Attitudes: Studies seek to map the views of interest groups to provide an overview of attitudes to be acknowledged and balanced | Negotiability: Studies seek to expose uncertainty and identify strategies employed by groups of actors to demonstrate how decisions are made and work in practice |

| Research agenda | Mainly prescriptive: Develop decision models and methods that provide for rational allocation of scarce resources | Mainly prescriptive: Develop principles that provide for fair allocation of scarce resources | Mainly descriptive: Develop insights about factors that impact the legitimacy and successful implementation of allocative decisions and models | Mainly descriptive and critical: Challenge beliefs in prescriptive decision models |

| Solutions suggested to improve PSR practices | Objective and accurate models that provide for transparent decision‐making | More sophisticated theoretical conceptions | Participatory techniques that take into account the characteristics of the political context | Explicitation of the social dynamics that shape allocative practices |

HEALTH ECONOMIC PERSPECTIVE ON PSR

The overall aim of the studies we have categorised as health economic is to aid rational resource allocation. With the analytical starting point that healthcare demands will always exceed the available resources, PSR is analysed as situations that require decision‐makers to make choices. The aim of the studies is to avoid ‘irrational’ choices and ‘sub‐optimal’ spending patterns, by developing evaluation methods and decision models for explicit priority setting. This will ultimately enhance the accountability of decision‐makers to the communities they serve. Hence, the studies mainly use the term ‘priority setting’ and use this concept to refer to systematic approaches undertaken to specify the allocation of resources among competing services or treatments based on explicit criteria and methods. Key studies include Cromwell et al. (2015), Nobre et al. (1999), Tsourapas and Frew (2011) and Hauck et al. (2004).

Health economic studies typically focus on the development and refinement of decision models that serve to systematically compare alternative investments. Based on studies of population ‘preferences’, various decision criteria are ‘weighted’ to model their societal importance. The notion of preference derives from consumer studies that estimate the demand for particular goods or services. In relation to priority setting, preference studies are used to estimate the acceptability of particular decision criteria in a given population. Economic studies have traditionally focussed on maximising health gains, subject to budget constraints, through a certain distribution of resources (Brookes et al., 2015; Tsourapas & Frew, 2011; Wilkinson et al., 2016). Studies increasingly promote more multi‐faceted approaches however, where ‘rational’ investments are not limited to the idea of cost‐benefit maximisation. Many studies promote overarching models to guide decisions, such as multi‐criteria decision analysis (MCDA) (Brookes et al., 2015; Cromwell et al., 2015; Nobre et al., 1999; Paolucci et al., 2017), and programme budgeting and marginal analysis (PBMA) (Cromwell et al., 2015; Mitton, 2003; Mitton et al., 2003; Peacock et al., 2010; Tsourapas & Frew, 2011; Wilson et al., 2009). Other studies apply ‘equity weights’ to traditional health economic outcome measures, such as quality‐adjusted life‐years (QALYs) (Norheim et al., 2014; Wilson et al., 2009).

While new decision criteria are explored and adopted in the economic decision‐models, the understanding of ‘rational’ decision‐making is still built upon the explicit modelling of decision criteria. Analytical attention is, in this way, centred upon methodological discussions related to the construction of outcome measures (e.g. Heller et al., 2006; Wilson et al., 2009) and the elicitation of preferences from research panels that are meant to represent particular populations (e.g. adult citizens in a country) (Nobre et al., 1999; Peacock et al., 2010). Discussions, for instance, may be concerned with how to aggregate or model variability in preferences among various stakeholder groups (Brookes et al., 2015; Heller et al., 2006; Schwappach, 2005). The proposed solutions to the social conflicts associated with priority setting tend to be based on more precise methods. Some studies note an apparent paradox: The practical impact of economic ‐models for priority setting is still limited even though these models have become more widespread. To make sense of this paradox, it is suggested in these studies that decision‐makers may have limited understanding of the methodology underpinning decision analysis (Brookes et al., 2015; Wilkinson et al., 2016), implying a need to make economic evaluation more attuned to decision‐makers’ needs and local circumstances (Cromwell et al., 2015; Lasry et al., 2008; Peacock et al., 2010). In this way, in order to overcome misalignments between models and practices, health economic studies tend to advocate adjustments of methods and models.

BIOETHICAL PERSPECTIVES ON PSR

Bioethical studies consider PSR to contain an inevitable dilemma on how to balance moral principles in order to achieve a just allocation of resources (Scheunemann & White, 2011). Generally, bioethicists focus on the rationing of health care resources, and define this as decisions that limit an individual's access to potentially beneficial medical care as a means to conserve or allocate scarce resources. The bioethicist studies do not discuss whether to ration or not, but ‘how, by whom and to what degree’ (Teutsch & Rechel, 2012, p. 1). Central works include: Daniels and Sabin (2006 [1997]), Ubel (2000), Rosoff (2017a) and Peppercorn et al. (2014).

Bioethical studies are concerned with allocative justice. To them, implicit rationing constitutes an equity problem as it may obscure potentially discriminatory principles, such as resource distribution through (in)ability to pay (Gruenewald, 2012; Maynard, 1999) or decisions reflecting a clinician's own individual bias (Oei, 2016). Implicit rationing also entails the risk of undermining the doctor/patient relationship, as it gives the doctor the role of a ‘double agent’ working in the interest of both the patient and the administration (Lauridsen, 2009; Menzel, 1993; Oei, 2016). Some early studies argued in favour of implicit rationing conducted by individual clinicians, because they observed an unwillingness among political decision‐makers to take responsibility for PSR decisions (Grimes, 1987). Others saw implicit rationing as a way of respecting ‘professional ethics’ or individual assessments (Kleinert, 1998; Norheim, 1995; Rosenblatt & Harwitz, 1999). During the past two decades however, most studies agree that explicit decision‐making about resource allocation is the way forward (Daniels & Sabin, 2008b; Lauridsen, 2009; Rosoff, 2017b; Ubel, 2000).

To inform explicit decision processes, bioethical studies seek to develop theoretically robust conceptions and criteria. Four overall philosophical positions are represented in bioethical studies. First, utilitarianism, which promotes the greatest good for the highest number (see, for example, Elfenbein et al., 1994). Second, egalitarianism, which is a broad term used to define the pursuit of equality (Williams et al., 2012). Third, liberalism¸ which promotes the individual's right to self‐determination (Zwart, 1993), and fourth, communitarianism, which promotes ‘community values’ and places the community at the centre (Mooney, 1998). In discussions about the concrete principles used to set limits for access to resources, it is often argued that ‘need’, rather than, say, ‘age’, or ‘immigration status’ is a more legitimate distributive principle, because it is clinically relevant and morally defensible (Rosoff, 2017a). The question of how to conceptualise and rank needs, however, is subject to debate (Hope et al., 2010; Maynard, 1999; Rosoff, 2017a).

Contending that consensus on allocative principles is unfeasible, many studies today subscribe to the idea of a fair process. The ‘accountability for reasonableness’ (or ‘A4R’) framework developed by Daniels and Sabin (2008b, 2008a) is supported by most bioethical studies in this review (though see Klonschinski's critique (2016)). The A4R framework provides four criteria against which the fairness of PSR processes can be measured: (1) Publicity, that is, that PSR decisions should be made accessible to the public, (2) relevance, that is, that PDR decisions should be influenced by relevant evidence, (3) revision and appeal, that is, that mechanisms are in place to challenge and review PSR decisions and (4) regulation and enforcement, that is, that mechanisms are in place to enforce the three other conditions (Daniels & Sabin, 2008a, p. 45ff).

HEALTH POLICY PERSPECTIVES ON PSR

In the health policy perspective, PSR is considered a political process, the success of which depends on stakeholder attitudes and organisational implementation. The studies aim to bridge the gap between PSR principles and practice by examining how local adaptions and stakeholder involvement may improve the feasibility and democratic legitimacy of PSR processes. The studies often frame decision‐makers as their audience, and provide knowledge that is both applicable or useful to actors working with PSR, as well as academics seeking to improve PSR models. A central idea is that by taking multiple stakeholder attitudes into account through participatory processes, it becomes possible to ‘move away from the normal pulling and hauling of competing political forces in procedures of policy consultation towards a more collectively orientated and problem‐orientated basis of decision‐making’ (Weale et al., 2016, p. 12). The literature is characterised by having limited references to other studies. On democratic deliberation, key studies include Weale (2016), Weale et al. (2016), and Broqvist and Garpenby (2015). On the implementation of PSR models, key studies include Gibson et al. (2004) and Hall et al. (2016).

The health policy perspective includes three types of studies: (1) Evaluations and implementation analyses of particular models and approaches, such as PBMA or A4R, often coupled with practical guides for future users (e.g. Cornelissen et al., 2014; Mitton, 2003). These studies explain implementation problems through factors related to institutions, interests, organisations, management and resources (Barasa et al., 2017; Maluka, 2011; Teng et al., 2007). (2) Analyses of attitudes to PSR. Reflecting the idea that it is important to strike a balance among different views in order to ensure the legitimacy of rationing decisions (Rosen & Karlberg, 2002), these studies examine and compare the attitudes and expectations of different stakeholder groups (typically doctors, policymakers and citizens) to PSR and to different kinds of rationing criteria, such as age, disease severity or social position (Aidem, 2017; Broqvist et al., 2018; Kuder & Roeder, 1995; Rogge & Kittel, 2016). Furthermore, they examine who is seen as acceptable decision‐makers, for example, doctors or administrative gatekeepers (Broqvist & Garpenby, 2015; Kuder & Roeder, 1995). (3) Public and patient participation. These studies operate with the premise that traditional guidelines for process legitimacy do not sufficiently secure public legitimacy. Their solution is increased public participation. Participation is understood broadly as ‘taking part in the processes of formulation, passage and implementation of public policies’ (Weale et al., 2016, p. 739), and includes a range of activities, ranging from providing citizens with formal roles in priority setting processes to open contestation of rationing decisions (Hunter et al., 2016).

SOCIOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES ON PSR

Sociological studies tend to use the term ‘rationing’ rather than ‘priority setting’, which reflects an interest in the socially contingent factors and implications of resource allocation rather than specific decision‐models or frameworks for setting priorities. Rationing is understood as a situated negotiation shaped by multiple social factors. Many sociological studies problematise the assumptions of prescriptive decision models, documenting how they often give rise to new problems when applied in practice. Sociological contributions are typically defined in opposition to the prescriptive approaches characteristic of the economic and bioethical perspectives. Consequently, the sociological literature does not form a collective conversation, but is fragmented and dispersed in comparison with the economic and bioethical literature. Central studies are primarily from earlier decades, such as Light and Hughes (2001) and Mechanic (1997), with slightly newer contributions being Moreira (2011), Hedgecoe (2006) and Calnan et al. (2017).

Early studies positioned themselves in direct opposition to the agenda of explicating PSR decisions and decision processes, emphasising PSR's ‘susceptibility to political manipulation’ (Mechanic, 1997, p. 86). We are better off, they argued, ‘muddling through elegantly 1 ’ (ibid.). Today, many studies are concerned with what may be called the reductionist assumptions of prescriptive approaches to PSR, which allegedly fail to recognise the uncertainty and derived negotiable nature of rationing decisions, whether in regulatory or clinical settings. According to these studies, the prescriptive models run the risk of being inoperable in empirical situations or of having unintended implications for decision‐makers and affected citizens (Chabrol et al., 2017; Garpenby & Nedlund, 2016; Kaufman, 2009; Light & Hughes, 2001; Moreira, 2011; Rhodes et al., 2019; Syrett, 2003).

There are three main types of sociological studies. The first challenges the very idea of explicit rationing. Light and Hughes (2001) question whether rationing is at all inevitable and argue that the project of rationing health care resources is built on fallacies associated with the idea ‘rational choice’ school of economic thought. These sociologogical studies intend to expose how rational choice arguments shape our definition and framing of societal problems and their solution (Joyce, 2001). Related to these studies are ones that demonstrate how social phenomena are co‐constituted with rationing, including scarcity (Chabrol et al., 2017), disinvestment (Rooshenas et al., 2015), exceptionality (Hughes & Doheny, 2019), death (Timmermans, 1999), life longevity (Kaufman, 2009) and patient deservingness (Hughes & Doheny, 2019; Rhodes et al., 2019; Vassy, 2001). The second type describes how social dynamics shape rationing decisions, focussing on different aspects and levels of social dynamics, including national contexts (Gross, 1994; Stanton, 1999; Wells, 2003), organisational factors (Calnan et al., 2017; Hughes & Griffiths, 1997; Prior, 2001; Sandberg et al., 2018) and doctors' professional judgement (Gross, 1994; Hedgecoe, 2006; Klein et al., 1995). The third type analyses the steps taken by organisations or individuals to navigate through ‘the layers of complexity and uncertainty’ in making PSR decisions (Calnan et al., 2017; Hughes & Doheny, 2019; Sjögren, 2006; Sjögren, 2008; Syrett, 2007).

DISCUSSION: TOWARDS INTERDISCIPLINARY DIALOGUE

Having described the particularities of the four disciplinary approaches, we will now discuss how a sociological perspective could influence debates about PSR in the future. Firstly, by building a stronger and more coherent analytical approach to PSR, and secondly, by offering sociological insights into the practice of PSR as a contribution to the prescriptive approaches that are currently dominant.

Refining the sociological perspective on PSR

The impact of sociological analyses of rationing may be currently impeded by their dispersion, and by their limited engagement with current studies from the popular approaches to PSR. To help the uptake of sociological insights by other disciplines, two related strategies could be pursued:

Firstly, sociologists could work to (re‐)establish PSR as a sociological field of research by choosing and solidifying a shared vocabulary to analyse PSR processes and their outcomes, and by exchanging and strengthening arguments internally to foster an accumulation of insights. One theme that is relevant to stimulate this development is that of mechanisms or strategies used to deal with the complex and uncertain nature of rationing processes. This theme unites many sociological studies of PSR (e.g. Calnan et al., 2017; Hughes & Doheny, 2011; Hughes & Doheny, 2019, Hughes & Griffiths, 1997; Moreira, 2011; Sjögren, 2008). However, it has hitherto involved only limited shared theory‐building. One identified strategy is to mobilise categories of ‘exceptionality’ to allow individual clinical judgements to ‘override managerial or political guidelines on allocation’ (Hughes & Doheny, 2019, p. 1601; Syrett, 2007, p. 55). Another strategy, ‘stratification’, is pursued by regulators in negotiations over delineations of populations eligible for specific treatment (Wadmann & Hauge, 2021). The strategies vary in terms of whether they are used to ‘deal’ with complexity and/or to pursue political interests, but they share the assumption that the reality of rationing and priority setting is never settled, but involves ongoing dilemmas and value struggles. The conceptualisation and classification of these strategies begun by scholars such as Sjögren (2008) and Calnan et al. (2017) could become a key element in a contemporary sociology of rationing.

While sociological studies have traditionally pursued post hoc, critical analyses of PSR, future contributions could explore the potential of integrating the knowledge built through this work in the ex ante process of developing and designing PSR models and systems. An example of such an attempt is provided by Moreira (2011), who develops an uncertainty‐focussed conceptual model based on the idea that ‘accepting and fostering the exploration of uncertainty at the core of health care priority setting systems should provide those systems with increased social robustness’ (Moreira, 2011, p. 1333). Moreira's model provides a different solution to the paradox presented above; that the practical impact of economic models of priority setting remains limited, even though the models are becoming still more widespread. Where health economic studies problematise the gap between PSR ideals and practice and intend to close it by means of adjusting PSR models, Moreira sees this gap as a premise for political decision‐making. Moreira's argument is that uncertainty and inapplicability cannot be delimited by fine‐tuning the PSR systems. Rather, he suggests that accepting and exploring the aspects of uncertainty can in fact increase the PSR systems' robustness (Moreira, 2011). Framing sociological insights as lessons for the future of PSR might lead to a strengthened and more distinct sociological conversation about PSR, which other disciplines could relate to, challenge, and learn from.

Secondly, the sociology of rationing could improve its position by updating its assumptions about the dominant approaches to PSR. During the past 20–30 years, the economic and bioethical literature has moved from idealistic modelling to more pragmatic and multi‐facetted approaches recognising the various and often conflicting positions in PSR (e.g. Daniels & Sabin, 2006 [1997]; Norheim et al., 2014). This development requires acknowledgement, and a more complex response, than that provided by many sociological studies so far. Further, it implies that the sociological perspective is not nearly as far removed from the prescriptive approaches as in the 1990s, because these approaches increasingly recognise and attempt to deal with the uncertainties and political negotiations of PSR. In fact, there is a shared interest among the disciplinary perspectives in understanding why PSR systems and principles often work differently than intended (e.g. Cleary et al., 2010; Cromwell et al., 2015), which constitutes a perfect occasion for a sociological response.

Sociological contributions to an interdisciplinary dialogue on PSR

With a strengthened perspective on PSR, the sociology of rationing could make several relevant contributions to an interdisciplinary dialogue. Firstly, sociological studies can grasp the dilemmas and implications of PSR that unfold in clinical practice. For example, sociologists can demonstrate how and why rationing decisions based on cost‐effectiveness considerations may lose legitimacy and practical applicability, when these decisions are translated from administrative settings into clinical practice where competing values may prevail (e.g. Hughes & Doheny, 2011; Wadmann & Hauge, 2021). In this way, a sociological argument could be that a good PSR decision is not only just, rational and democratic, it also needs to be applicable and legitimate in practical, clinical situations. In the same vein, a sociological contribution to the current focus on strengthening the viability of PSR models and decisions could be to explore the possibility of reciprocal exchange between clinical practice and priority setting. This could be by integrating a feedback loop in the decision‐making process in order to evaluate the decision's practical applicability and consequences for clinical practice.

Secondly, sociological studies could explore the possibilities and challenges that arise when questions of access to treatment traverse regional and national borders. The decision‐models developed by economists, bioethicists or political scientists are often designed for administrative units with budgetary responsibility; typically nations, regions or hospitals. The challenges for local decision‐makers, however, are increasingly influenced by global dynamics, such as changing regulatory standards for market approval of medical technologies (Salcher‐Konrad et al., 2020), the market dynamics of Big Pharma, and the international organisation and mobilisation of patient groups (Callon & Rabeharisoa, 2008; Epstein, 2008). As digital media enable information to travel faster and wider than ever, local rationing decisions may quickly reach a global audience, and international differences in access criteria for, or evaluations of, specific treatments can be exposed and used to challenge the legitimacy of local PSR decisions.

Thirdly, a sociological perspective could contribute to the development of new forms of patient and public involvement in PSR processes. The dominant perspectives on PSR operate with different reasons and means for including public viewpoints. Political scientists aim to ensure legitimacy by including population samples represented through, for instance, citizen panels (e.g. Schwappach, 2005). Economists measure citizen preferences in order to inform their models (e.g. Shah, 2009), while bioethicists often use patient case stories to support arguments for particular procedures or principles (e.g. Gruenewald, 2012). Increasingly, however, patients and patient organisations are not waiting to be included. They seek to gain influence by setting research agendas and otherwise engaging in knowledge production; something that Rabeharisoa et al. (2014) call evidence‐based activism. As the challenges of patient and public engagement are well documented (Irwin et al., 2013; Steffensen et al., 2022), sociological studies could investigate the motives and strategies of patients and publics who self‐organise. This could foster social innovation and find new ways of taking the concerns of affected patient groups seriously.

CONCLUSION

The increasing reliance on explicit priority setting and rationing as solutions to the problem of how to distribute scarce healthcare resources underscores the relevance of interrogating and debating the assumptions and consequences of these solutions. Sociological studies have a strong tradition of critical inquiry into PSR systems and decisions, and an analytical lens attuned to observing the value negotiations involved in PSR practices. However, the sociological perspective has still only had limited impact on the current academic and political debates on PSR. To explore the potential of sociological arguments in a cross‐disciplinary dialogue on PSR, we have conducted a critical, interpretive literature study and analysed the potential for revitalising a contemporary sociology of rationing. Our review provides an analytical overview of the assumptions and research agendas that characterise four disciplines engaged in PSR debates: economics, bioethics, health policy and sociology. On this basis, we argue that the sociology of rationing could advance its potential by establishing a shared conceptual vocabulary and an intra‐disciplinary exchange of arguments. With its ability to grasp the contextual and processual aspects of PSR, the sociology of rationing could contribute to interdisciplinary debates and offer important observations on the viability of PSR systems and decisions. We point to three thematic opportunities: Firstly, the translation of administrative PSR decisions into clinical practice and treatment decisions for individual patients. Sociological studies could offer insights on the problems brought about by this process, and thereby provide a feedback loop to administrative PSR processes. Secondly, the challenges and opportunities that arise when questions of treatment access traverse national borders. The sociological perspective can bring forward the expanding repertoire of arguments available to stakeholders of PSR and analyse clashes between international and local value parameters. Thirdly, the development of alternative approaches to patient and public involvement in PSR. Sociological studies have observed increasing public contestation of PSR decisions from patient movements and may translate this knowledge into lessons for future patient involvement in PSR systems.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Amalie Martinus Hauge: Conceptualisation; Equal, Formal analysis; Equal, Data curation; Equal, Methodology; Equal, Project administration; Lead, Writing – original draft; Lead, revision; Lead. Eva Iris Otto: Conceptualisation; Equal, Formal analysis; Equal, Methodology; Equal. Sarah Wadmann: Conceptualisation; Equal, Formal analysis; Equal, Data curation; Equal, Methodology; Equal, Project administration; Supporting, Writing – original draft; Supporting, revision; Supporting.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank colleagues from VIVE with different disciplinary backgrounds for engaging with our project. Particularly, we are grateful to Bjørn Christian Arleth Viinholt, VIVE, who provided technical assistance and advice regarding the literature search and to Lise Desireé Hansen for feedback on an early version of the analysis. We would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers and the editorial team for constructive comments. The study is based on research conducted within an unrestricted research grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF17OC0026466).

Hauge, A. M. , Otto, E. I. , & Wadmann, S. (2022). The sociology of rationing: Towards increased interdisciplinary dialogue ‐ A critical interpretive literature review. Sociology of Health & Illness, 44(8), 1287–1304. 10.1111/1467-9566.13507

END NOTE

A phrase suggested in an editorial by hospital director of the NHS David J Hunter in 1995 (Hunter, 1995).

Contributor Information

Amalie Martinus Hauge, Email: amha@vive.dk.

Eva Iris Otto, Email: eio@anthro.ku.dk.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this literature study are academic articles available via the bibliographical databases Academic Search Premier, Embase, Socindex, Medline and Econlit. The study's protocol and a full list of included papers are available on request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- Aidem, J. M. (2017). Stakeholder views on criteria and processes for priority setting in Norway: A qualitative study. Health Policy, 121(6), 683–690. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angell, B. , Pares, J. , & Mooney, G. (2016). Implementing priority setting frameworks: Insights from leading researchers. Health Policy, 120(12), 1389–1394. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barasa, E. W. , Molyneux, S. , English, M. , & Cleary, S. (2017). Hospitals as complex adaptive systems: A case study of factors influencing priority setting practices at the hospital level in Kenya. Social Science & Medicine, 174, 104–112. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.12.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes, V. J. , Del Rio, V. V. , & Ward, M. P. (2015). Disease prioritization: What is the state of the art? Epidemiology and Infection, 143(14), 2911–2922. 10.1017/s0950268815000801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broqvist, M. , & Garpenby, P. (2015). It takes a giraffe to see the big picture ‐ Citizens' view on decision makers in health care rationing. Social Science & Medicine, 128, 301–308. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broqvist, M. , Sandman, L. , Garpenby, P. , & Krevers, B. (2018). The meaning of severity ‐ do citizens views correspond to a severity framework based on ethical principles for priority setting? Health Policy, 122(6), 630–637. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brousselle, A. , & Lessard, C. (2011). Economic evaluation to inform health care decision‐making: Promise, pitfalls and a proposal for an alternative path. Social Science & Medicine, 72(6), 832–839. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callon, M. , & Rabeharisoa, V. (2008). The growing engagement of emergent concerned groups in political and economic life: Lessons from the French association of neuromuscular disease patients. Science, Technology & Human Values, 33(2), 230–261. 10.1177/0162243907311264 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calnan, M. , Hashem, F. , & Brown, P. (2017). Still elegantly muddling through? NICE and uncertainty in decision making about the rationing of expensive medicines in England. International Journal of Health Services, 47(3), 571–594. 10.1177/0020731416689552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabrol, F. , David, P. , & Krikorian, G. (2017). Rationing hepatitis C treatment in the context of austerity policies in France and Cameroon: A transnational perspective on the pharmaceuticalization of healthcare systems. Social Science & Medicine, 187, 243–250. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary, S. , Mooney, G. , & McIntyre, D. (2010). Equity and efficiency in HIV‐treatment in South Africa: The contribution of mathematical programming to priority setting. Health Economics, 19(10), 1166–1180. 10.1002/hec.1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson, R. , & Dolan, P. (2000). Principles of justice in health care rationing. Journal of Medical Ethics, 26(5), 323–329. 10.1136/jme.26.5.323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelissen, E. , Mitton, C. , Davidson, A. , Reid, C. , Hole, R. , Visockas, A.‐M. , & Smith, N. (2014). Determining and broadening the definition of impact from implementing a rational priority setting approach in a healthcare organization. Social Science & Medicine, 114, 1–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromwell, I. , Peacock, S. J. , & Mitton, C. (2015). Real‐world' health care priority setting using explicit decision criteria: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Services Research, 15(1), 164. 10.1186/s12913-015-0814-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, N. , & Sabin, J. (2006) [1997]. "limits to health care: Fair procedures, democratic deliberation, and the legitimacy problem for insurers. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 26(4), 303–350. 10.1111/j.1088-4963.1997.tb00082.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, N. , & Sabin, J. E. (2008a). Setting limits fairly: Learning to share resources for health. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, N. , & Sabin, J. (2008b). Accountability for reasonableness: An update. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 337, 1850. 10.1136/bmj.a1850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon‐Woods, M. , Cavers, D. , Agarwal, S. , Annandale, E. , Arthur, A. , Harvey, J. , Hsu, R. , Katbamna, S. , Olsen, R. , Smith, L. , Riley, R. , & Sutton, A. J. (2006). Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 6(1), 35. 10.1186/1471-2288-6-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfenbein, P. , Miller, J. B. , & Milakovich, M. (1994). Medical resource allocation: Rationing and ethical considerations‐‐Part I. Physician Executive, 20(2), 3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, S. (2008). Patient groups and health movements. In Hackett E. J., Amsterdamska O., Lynch D. & Wacjman J. (Eds.), New handbook of science and technology studies (pp. 499–539). Mit Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garpenby, P. , & Nedlund, A.‐C. (2016). Political strategies in difficult times ‐ the “backstage” experience of Swedish politicians on formal priority setting in healthcare. Social Science & Medicine, 163, 63–70. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J. L. , Martin, D. K. , & Singer, P. A. (2004). Setting priorities in health care organizations: Criteria, processes, and parameters of success. BMC Health Services Research, 4(1), 25. 10.1186/1472-6963-4-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough, D. , Thomas, J. , & Oliver, S. (2012). Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Systematic Reviews, 1(1), 28. 10.1186/2046-4053-1-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, L. , & Hughes, D. (1998). Purchasing in the British NHS: Does contracting mean explicit rationing? Health, 2(3), 349–371. 10.1177/136345939800200305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes, D. S. (1987). Rationing health care. Lancet (London, England), 1(8533), 615–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross, E. B. (1994). Health care rationing: Its effects on cardiologists in the United States and Britain. Sociology of Health & Illness, 16(1), 19–37. 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11346997 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald, D. A. (2012). Can health care rationing ever Be rational? Journal of Law Medicine & Ethics, 40(1), 17–25. 10.1111/j.1748-720x.2012.00641.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, W. , Smith, N. , Mitton, C. , Gibson, J. , & Bryan, S. (2016). An evaluation tool for assessing performance in priority setting and resource allocation: Multi‐site application to identify strengths and weaknesses. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 21(1), 15–23. 10.1177/1355819615596542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck, K. , Smith, P. C. , & Goddard, M. (2004). The economics of priority setting for health care: A literature review. [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecoe, A. M. (2006). It's money that matters: The financial context of ethical decision‐making in modern biomedicine. Sociology of Health & Illness, 28(6), 768–784. 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2006.00541.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller, R. F. , Gemmell, I. , Wilson, E. C. F. , Fordham, R. , & Smith, R. D. (2006). Using economic analyses for local priority setting: The population cost‐impact approach. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 5(1), 45–54. 10.2165/00148365-200605010-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope, T. , Østerdal, L. P. , & Hasman, A. (2010). An inquiry into the principles of needs‐based allocation of health care. Bioethics, 24(9), 470–480. 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2009.01734.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D. , & Doheny, S. (2011). Deliberating tarceva: A case study of how British NHS managers decide whether to purchase a high‐cost drug in the shadow of NICE guidance. Social Science & Medicine, 73(10), 1460–1468. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D. , & Doheny, S. (2019). Constructing ‘exceptionality’: A neglected aspect of NHS rationing. Sociology of Health & Illness, 41(8), 1600–1617. 10.1111/1467-9566.12976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, D. , & Griffiths, L. (1997). ‘Ruling in’ and ‘Ruling out’: Two approaches to the micro‐rationing of health care. Social Science & Medicine, 44(5), 589–599. 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00207-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, D. J. (1995). Rationing: The case for "muddling through elegantly. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 311(7008), 811. 10.1136/bmj.311.7008.811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, D. J. , Kieslich, K. , Littlejohns, P. , Staniszewska, S. , Tumilty, E. , Weale, A. , & Williams, I. (2016). Public involvement in health priority setting: Future challenges for policy, research and society. Journal of Health, Organisation and Management, 30(5), 796–808. 10.1108/jhom-04-2016-0057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, A. , Jensen, T. E. , & Jones, K. E. (2013). The good, the bad and the perfect: Criticizing engagement practice. Social Studies of Science, 43(1), 118–135. 10.1177/0306312712462461 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, P. (2001). Governmentality and risk: Setting priorities in the new NHS. Sociology of Health & Illness, 23(5), 594–614. 10.1111/1467-9566.00267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, S. R. (2009). Making longevity in an aging society: Linking ethical sensibility and medicare spending. Medical Anthropology, 28(4), 317–325. 10.1080/01459740903303852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein, R. , Day, P. , & Redmayne, S. (1995). Rationing in the NHS: The dance of the seven veils‐in reverse. British Medical Bulletin, 51(4), 769–780. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinert, S. (1998). Rationing of health care‐‐how should it be done? Lancet, 352(9136), 1244. 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)70485-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonschinski, A. (2016). The trade‐off metaphor in priority setting: A comment on Lübbe and Daniels. In Prioritization in medicine (pp. 67–81). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kuder, L. B. , & Roeder, P. W. (1995). Attitudes toward age‐based health care rationing. A qualitative assessment. Journal of Aging and Health, 7(2), 301–327. 10.1177/089826439500700207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasry, A. , Carter, M. W. , & Zaric, G. S. (2008). S4HARA: System for HIV/AIDS resource allocation. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation, 6(1), 7. 10.1186/1478-7547-6-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauerer, M. , Schätzlein, V. , & Nagel, E. (2016). Introduction to an international dialogue on prioritization in medicine. In Nagel E. & Lauerer M. (Eds.), Prioritization in medicine: An international dialogue (pp. 1–10). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lauridsen, S. (2009). Administrative gatekeeping ‐ A third way between unrestricted patient advocacy and bedside rationing. Bioethics, 23(5), 311–320. 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00652.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light, D. W. , & Hughes, D. (2001). Introduction: A sociological perspective on rationing: Power, rhetoric and situated practices. Sociology of Health & Illness, 23(5), 551–569. 10.1111/1467-9566.00265 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maluka, S. O. (2011). Strengthening fairness, transparency and accountability in health care priority setting at district level in Tanzania. Global Health Action, 4(1), 1–11. 10.3402/gha.v4i0.7829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, A. (1999). Rationing health care: An exploration. Health Policy, 49(1–2), 5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic, D. (1997). Muddling through elegantly: Finding the proper balance in rationing. Health Affairs, 16(5), 83–92. 10.1377/hlthaff.16.5.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel, P. T. (1993). Double agency and the ethics of rationing health care: A response to marcia angell. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal, 3(3), 287–292. 10.1353/ken.0.0255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitton, C. , Patten, S. , Waldner, H. , & Donaldson, C. (2003). Priority setting in health authorities: A novel approach to a historical activity. Social Science & Medicine, 57(9), 1653–1663. 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00549-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitton, C. R. , Donaldson, C. , Waldner, H. , & Eagle, C. (2003). The evolution of PBMA: Towards a macro‐level priority setting framework for health regions. Health Care Management Science, 6(4), 263–269. 10.1023/a:1026285809115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, G. (1998). “Communitarian claims” as an ethical basis for allocating health care resources. Social Science & Medicine, 47(9), 1171–1180. 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00189-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, T. (2011). Health care rationing in an age of uncertainty: A conceptual model. Social Science & Medicine, 72(8), 1333–1341. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobre, F. F. , Trotta, L. T. , & Gomes, L. F. (1999). Multi‐criteria decision making‐‐an approach to setting priorities in health care. Statistics in Medicine, 18(23), 3345–3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norheim, O. F. (1995). The Norwegian welfare state in transition: Rationing and plurality of values as ethical challenges for the health care system. Journal of Medicine and Philosophy, 20(6), 639–655. 10.1093/jmp/20.6.639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norheim, O. F. , Baltussen, R. , Johri, M. , Chisholm, D. , Nord, E. , Brock, D. W. , Carlsson, P. , Cookson, R. , Daniels, N. , Danis, M. , Fleurbaey, M. , Johansson, K. A. , Kapiriri, L. , Littlejohns, P. , Mbeeli, T. , Rao, K. D. , Edejer, T. T.‐T. , & Wikler, D. (2014). Guidance on priority setting in health care (GPS‐Health): The inclusion of equity criteria not captured by cost‐effectiveness analysis. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation, 12(1), 18. 10.1186/1478-7547-12-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oei, G. (2016). Explicit versus implicit rationing: Let's Be honest. The American Journal of Bioethics, 16(7), 68–70. 10.1080/15265161.2016.1180449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace, J. , Pearson, S. , & Lipworth, W. (2015). Improving the legitimacy of medicines funding decisions: A critical literature review. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science, 49(3), 364–368. 10.1177/2168479015579519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolucci, F. , Redekop, K. , Fouda, A. , & Fiorentini, G. (2017). Decision making and priority setting: The evolving path towards universal health coverage. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 15(6), 697–706. 10.1007/s40258-017-0349-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock, S. J. , Mitton, C. , Ruta, D. , Donaldson, C. , Bate, A. , & Hedden, L. (2010). Priority setting in healthcare: Towards guidelines for the program budgeting and marginal analysis framework. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 10(5), 539–552. 10.1586/erp.10.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppercorn, J. , Zafar, S. Y. , Houck, K. , Ubel, P. , & Meropol, N. J. (2014). Does comparative effectiveness research promote rationing of cancer care? The Lancet Oncology, 15(3), e132–e138. 10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70597-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prior, L. (2001). Rationing through risk assessment in clinical genetics: All categories have wheels. Sociology of Health & Illness, 23(5), 570–593. 10.1111/1467-9566.00266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rabeharisoa, V. , Moreira, T. , & Akrich, M. (2014). Evidence‐based activism: Patients’, users’ and activists’ groups in knowledge society. BioSocieties, 9(2), 111–128. 10.1057/biosoc.2014.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, T. , Egede, S. , Grenfell, P. , Paparini, S. , & Duff, C. (2019). The social life of HIV care: On the making of ‘care beyond the virus. BioSocieties, 14(3), 321–344. 10.1057/s41292-018-0129-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogge, J. , & Kittel, B. (2016). Who shall not Be treated: Public attitudes on setting health care priorities by person‐based criteria in 28 nations. PLoS One, 11(6), e0157018. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooshenas, L. , Owen‐Smith, A. , Hollingworth, W. , Badrinath, P. , Beynon, C. , & Donovan, J. L. (2015). "I won't call it rationing…": An ethnographic study of healthcare disinvestment in theory and practice. Social Science & Medicine, 128, 273–281. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, P. , & Karlberg, I. (2002). Opinions of Swedish citizens, health‐care politicians, administrators and doctors on rationing and health‐care financing. Health Expectations, 5(2), 148–155. 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2002.00169.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt, L. , & Harwitz, D. G. (1999). Fairness and rationing implications of medical necessity decisions. American Journal of Managed Care, 5(12), 1525–1531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosoff, P. M. (2017a). Drawing the line: Healthcare rationing and the cutoff problem. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosoff, P. M. (2017b). Who should ration? AMA Journal of Ethics, 19(2), 164–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salcher‐Konrad, M. , Naci, H. , & Davis, C. (2020). Approval of cancer drugs with uncertain therapeutic value: A comparison of regulatory decisions in Europe and the United States. The Milbank Quarterly, 98(4), 1219–1256. 10.1111/1468-0009.12476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg, J. , Persson, B. , & Garpenby, P. (2018). The dilemma of knowledge use in political decision‐making: National guidelines in a Swedish priority‐setting context. Health Economics, Policy and Law, 14(4), 1–18. 10.1017/s1744133118000233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheunemann, L. P. , & White, D. B. (2011). The ethics and reality of rationing in medicine. Chest, 140(6), 1625–1632. 10.1378/chest.11-0622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwappach, D. L. B. (2005). Are preferences for equality a matter of perspective? Medical Decision Making, 25(4), 449–459. 10.1177/0272989x05276861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah, K. K. (2009). Severity of illness and priority setting in healthcare: A review of the literature. Health Policy, 93(2–3), 77–84. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjögren, E. (2006). Reasonable drugs: Making decisions with ambiguous knowledge. Economic Research Institute, Stockholm School of Economics (EFI). [Google Scholar]

- Sjögren, E. (2008). Deciding subsidy for pharmaceuticals based on ambiguous evidence. Journal of Health, Organisation and Management, 22(4), 368–383. 10.1108/14777260810893962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, J. (1999). The cost of living: Kidney dialysis, rationing and health economics in Britain, 1965‐1996. Social Science & Medicine, 49(9), 1169–1182. 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00158-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen, M. B. , Matzen, C. , & Wadmann, S. (2022). Patient participation in priority setting: Co‐existing participant roles. Social Science & Medicine, 294, 114713. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syrett, K. (2003). A technocratic fix to the 'legitimacy problem'? The blair government and health care rationing in the United Kingdom. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 28(4), 715–746. 10.1215/03616878-28-4-715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syrett, K. (2007). Law, legitimacy and the rationing of health care: A contextual and comparative perspective. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, F. , Mitton, C. , & Mackenzie, J. (2007). Priority setting in the provincial health services authority: Survey of key decision makers. BMC Health Services Research, 7(1), 84. 10.1186/1472-6963-7-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teutsch, S. , & Rechel, B. (2012). Ethics of resource allocation and rationing medical care in a time of fiscal restraint ‐ US and Europe. Public Health Reviews, 34(1), 1–10. 10.1007/bf03391667 26236074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans, S. (1999). When death isn't dead: Implicit social rationing during resuscitative efforts. Sociological Inquiry, 69(1), 51–75. 10.1111/j.1475-682x.1999.tb00489.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tsourapas, A. , & Frew, E. (2011). Evaluating 'success' in programme budgeting and marginal analysis: A literature review. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 16(3), 177–183. 10.1258/jhsrp.2010.009053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubel, P. A. (2000). Pricing life: Why it's time for health care rationing, Basic Bioethics series. A Bradford Book. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vassy, C. (2001). Categorisation and micro‐rationing: Access to care in a French emergency department. Sociology of Health & Illness, 23(5), 615–632. 10.1111/1467-9566.00268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wadmann, S. , & Hauge, A. M. (2021). Strategies of stratification: Regulating market access in the era of personalized medicine. Social Studies of Science, 51(4), 628–653. 10.1177/03063127211005539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, D. , & Downe, S. (2006). Appraising the quality of qualitative research. Midwifery, 22(2), 108–119. 10.1016/j.midw.2005.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weale, A. (2016). Between consensus and contestation. Journal of Health, Organisation and Management, 30(5), 786–795. 10.1108/jhom-03-2016-0040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weale, A. , Kieslich, K. , Littlejohns, P. , Tugendhaft, A. , Tumilty, E. , Weerasuriya, K. , & Whitty, J. A. (2016). Introduction: Priority setting, equitable access and public involvement in health care. Journal of Health, Organisation and Management, 3(5), 736–750. 10.1108/jhom-03-2016-0036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells, K. (2003). A needs assessment regarding the nature and impact of clergy sexual abuse conducted by the interfaith sexual trauma Institute. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 10(2), 201–217. 10.1080/10720160390230691 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, T. , Sculpher, M. J. , Claxton, K. , Revill, P. , Briggs, A. , Cairns, J. A. , Teerawattananon, Y. , Asfaw, E. , Lopert, R. , Culyer, A. J. , & Walker, D. G. (2016). The international decision support initiative reference case for economic evaluation: An aid to thought. Value in Health, 19(8), 921–928. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, I. , Robinson, S. , & Dickinson, H. (2012). Rationing in healthcare: The theory and practice of priority setting. The Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E. C. F. , Peacock, S. J. , & Ruta, D. (2009). Priority setting in practice: What is the best way to compare costs and benefits? Health Economics, 18(4), 467–478. 10.1002/hec.1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwart, H. (1993). Rationing in The Netherlands: The liberal and the communitarian perspective. Health Care Analysis: Journal of Health Philosophy and Policy, 1(1), 53–56. 10.1007/bf02196971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this literature study are academic articles available via the bibliographical databases Academic Search Premier, Embase, Socindex, Medline and Econlit. The study's protocol and a full list of included papers are available on request from the corresponding author.