Abstract

To a great extent, older people in Sweden, often with extensive care needs, are cared for in their own home. Support is often needed from both family and professional caregivers. This study aimed to describe and analyse different aspects of health, functioning and social networks, and how they relate to formal and informal care in the home among older adults. Analyses were performed utilising data from the OCTO‐2 study, with a sample of 317 people living in Jönköping County, aged 75, 80, 85 or 90 years, living in their own homes. Data were collected with in‐person‐testing. Based on receipt of care, the participants were divided into three groups: no care, informal care only, and formal care with or without informal care. Descriptive statistics and multinomial regression analysis were performed to explore the associations between received care and different aspects of health (such as multimorbidity, polypharmacy), social networks (such as loneliness, number of confidants) and functioning (such as managing daily life). The findings demonstrate that the majority of the participants received no care at home (61%). Multimorbidity and polypharmacy were more common among those receiving some kind of care in comparison to those who received no care; moreover, those receiving some kind of care also had difficulties managing daily life and less satisfaction with their social networks. The multinomial logistic regression analyses demonstrated that age, functioning in daily life, perceived general health and satisfaction with the number of confidants were related to receipt of care, but the associations among these factors differed depending on the type of care that was received. The results show the importance of a holistic perspective that includes the older person's experiences when planning home care. The results also highlight the importance of considering social perspectives and relationships in home care rather than focusing only on health factors.

Keywords: community, family caregiving, health and social care, health care, home care, informal care, older people

What is known about this topic

The care of older people is increasingly occurring at their homes.

The responsibility of informal (family) caregivers is increasing.

Multimorbidity, polypharmacy, and functional limitations are related to the receipt of home care.

What the paper adds

The situation for older people who receive formal and informal home care is complex from different aspects of health, social networks and functioning.

Functioning in daily life is related to both formal and informal care, but it has no significant correlation with multimorbidity and polypharmacy.

Perceived health is only related to informal care; satisfaction with the number of confidants is related to formal care. This indicates the importance of relationships and increasing awareness about the social perspectives of home care.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the last several decades, the structure of formal care in Sweden has changed. Shorter hospital stays, in combination with a decrease in the number of beds in residential care facilities, have led to an increase in older adults receiving in‐home care (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2019). Formal care, as defined in this study, includes both health care and social services, based on the needs of the older person and performed by different professional caregivers such as assistant nurses, nurses, physiotherapists and occupational therapists. The municipalities are obliged to provide in‐home care and service (Szebehely & Trydegård, 2012), mainly regulated by two laws: the Health Care Act (SFS 2017:30) and the Social Services Act (SFS 2001:453). The Health Care Act aims to medically prevent, investigate, and treat illnesses and injuries. The Social Services Act aims to promote people's economic and social security, equality in living conditions and active participation in social life. This means that people who cannot provide for themselves or manage daily life on their own, for example, have right to assistance and support after an assessment primarily based on their ability to perform daily activities.

In Sweden, families are also increasingly taking care of older people, often named informal care. Informal care is defined as nonpaid care provided by a family member or friend (National Board of Health and Welfare, 2019). This occurs even though, due to Swedish legalisation, families have no formal caregiving responsibilities. Formal home care has also decreased among older people with minor care needs, as their needs are increasingly being met by their family members (Szebehely & Trydegård, 2012; Wimo et al., 2017). People who are married or cohabiting are more likely to receive informal care, whereas people without a family need professional caregivers to continue living at home. Cognitive impairment and the need for psychosocial support are also related to the receipt of informal care (Sigurdardottir et al., 2012; Swinkels et al., 2016; Wimo et al., 2017).

This study illuminates different aspects of health, functioning and social networks. One aspect of health is multimorbidity that is presumed to affect care consumption in terms of health care and social services. Most definitions of multimorbidity describe the condition as living with at least two or more competing chronic or acute illnesses or medical conditions (Fortin et al., 2004; Valderas et al., 2009). Multimorbidity is often followed by polypharmacy, another aspect of health. While there seems to be no consensus in defining polypharmacy (Bushardt et al., 2008), a common definition used in this study is concomitant medication with three or more drugs (Ernsth Bravell, 2017). Due to increased average life expectancy, older people also have increasing care needs (Szebehely & Trydegård, 2012). Furthermore, older people with cognitive impairment are granted more services in personal care and more hours per month than clients without cognitive impairment. To a greater extent, home care services are granted to clients living alone (Sandberg et al., 2019). An aspect of functioning is the activities of daily living (ADL), which is often demonstrated to be related to the need for formal home care (Bravell et al., 2008).

As understood, multimorbidity is just one aspect that affects an older person's receipt of formal and informal home care. Formal and informal care are also related to other aspects of health, such as life satisfaction and aspects of social networks, such as perceived loneliness (Lee et al., 2020). However, there is limited knowledge about how different aspects of health, functioning, and social networks influence the receipt of formal and informal home care. This study enables a better understanding of their association with care, which is important in adequately planning for care and meeting the individual needs of older people who are cared for at home.

1.1. Aim

This study aimed to describe and analyse different aspects of health, functioning and social networks, and how they relate to in‐home formal and informal care of older adults.

2. METHOD

2.1. Design and participants

This study used data from OCTO‐2 for secondary analyses. The OCTO‐2 study collected data about different aspects of health, functioning, mobility and social networks, and was a population‐based study among older adults in Sweden (Fristedt et al., 2016; Kammerlind et al., 2014). The study population in OCTO‐2 consisted of 327 persons who were randomly selected from a population register on people living in Jönköping County, Sweden. Eligible for inclusion in the OCTO‐2 study were men and women in four age cohorts: 75‐, 80‐, 85‐ or 90 years‐old, living in Jönköping County, Sweden in 2009 and 2010. Persons with dementia were excluded from OCTO‐2. The present study excluded participants living in nursing homes (n = 10), thus yielding a sample of 317 participants.

OCTO‐2 used an in‐person data collection method that was performed by three trained research‐nurses who visited the study participants' homes to interview and examine them. The interviews were based on a large number of questions and questionnaires regarding, for example, health, quality of life, social networks, activities in daily life (ADL), and physical activity. The examinations included tests of cognitive function, blood pressure and physical performance. All participants chose to participate and gave their informed written consent.

2.2. Instruments and variables

Receipt of care was the outcome variable of this study. The participants were initially asked if they needed help in performing instrumental activities in daily life and/or with personal care and/or with health care matters. The follow‐up question was: If so, from whom do you receive the care (formal caregiver or informal caregiver or both)? Based on the answers, the participants were divided into three groups: no care, informal care only (receive care from relatives, such as spouses or children), and formal care (from professional caregivers) with or without informal care.

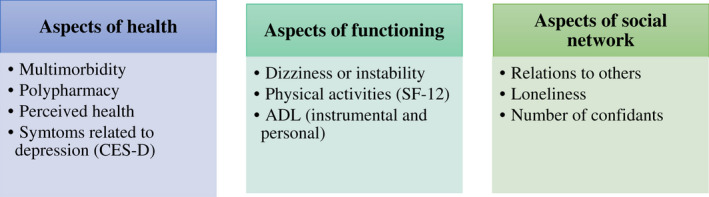

Variables related to different aspects of health, functioning, and social networks were selected from the questionnaire in OCTO‐2 (see Figure 1) based on previous research.

FIGURE 1.

Examples of the different aspects of health, functioning and social network included in the present study

Aspects of health were assessed with multimorbidity, polypharmacy, Short Form 12 Health Survey (S ‐12), Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D), and a question about quality of life.

Multimorbidity and polypharmacy: The participants were asked to describe their medical conditions, which were then summed and dichotomised in relation to the definition of multimorbidity (0–1 diseases = no multimorbidity, 2 or more diseases = multimorbidity). The use of prescribed drugs was handled in a similar way. The total number of drugs used was counted and dichotomised according to the definition of polypharmacy (0–2 drugs = no polypharmacy, 3 or more drugs = polypharmacy).

Self‐reported health was assessed using SF‐12 (Gandek et al., 1998). SF‐12 aims to provide glimpses into self‐reported mental and physical functioning and overall health‐related quality of life. Subjective health was addressed with the following question: In general, would you say your health is (1 = excellent, 2 = very good, 3 = good, 4 = fair, 5 = poor)? The physical and emotional dimensions were captured by the following questions: Does your health now limit you in these activities? If so, how much? This covered 11 different areas: moderate activities, climbing several flights of stairs (1 = Yes, limited a lot, 2 = Yes, limited a little, 3 = No, not limited at all), accomplished less than you would like (physical), were limited in activities (physical), accomplished less than you would like (emotionally), and did not do work or other activities as carefully as usual (emotionally) (1 = yes, 2 = no). Furthermore, the participants were asked questions regarding their experiences during the previous 4 weeks, such as: How much did pain interfere with your normal work? (1 = not at all, 2 = a little bit, 3 = moderately, 4 = quite a bit, 5 = extremely); Have you felt calm and peaceful? Did you have a lot of energy? Have you felt downhearted and blue? How much of the time has your physical health or emotional problems interfered with your social activities? These four questions had six response options (1 = all of the time, 2 = most of the time, 3 = a good bit of the time, 4 = some of the time, 5 = a little of the time, 6 = none of the time). In the descriptive analyses, response alternatives with low response rates were collapsed to increase power (see Table 2). For the regression analyses (see below), the one question, In general, would you say your health is, was used to estimate subjective health. The reason for not including the index of SF‐12 was to avoid multicollinearity.

TABLE 2.

Associations between aspects of health and functioning with the three outcome groups (no care, informal care only and formal care with or without informal care) using Kendall's Tau‐b

| No care | Informal care only | Formal care with or without informal care |

Kendall's Tau‐b (P) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 317 | 194 (61%) | 60 (19%) | 63 (20%) | ||

| Multimorbidity | |||||

| No | 124 (39.1) | 89 (45.9) | 16 (26.7) | 19 (30.2) | 0.156 (−0.003) |

| Yes | 193 (60.9) | 105 (54.1) | 44 (73.3) | 44 (69.8) | |

| Polypharmacy | |||||

| No | 137 (43.2) | 99 (51.0) | 20 (33.3) | 18 (28.6) | 0.191 (<0.001) |

| Yes | 180 (56.8) | 95 (49.0) | 40 (66.7) | 45 (71.4) | |

| SF‐12 | |||||

| In general, would you say your health is: | |||||

| Excellent/Very Good | 87 (27.6) | 74 (38.3) | 7 (11.7) | 6 (9.5) | 0.300 (<0.001) |

| Good | 130 (41.1) | 81 (42.0) | 17 (28.3) | 32 (50.8) | |

| Fair/Poor | 99 (31.3) | 38 (19.7) | 36 (60.0) | 25 (39.7) | |

| Moderate activities: | |||||

| Yes, limited a lot | 55 (17.5) | 12 (6.2) | 19 (31.7) | 24 (38.7) | −0.395 (<0.001) |

| Yes, limited a little | 150 (47.6) | 87 (45.1) | 35 (58.3) | 28 (45.2) | |

| No, not limited at all | 110 (34.9) | 94 (48.7) | 6 (10.0) | 10 (16.1) | |

| Climbing SEVERAL flights of stairs: | |||||

| Yes, limited a lot | 52 (16.6) | 12 (6.2) | 18 ( 30.0) | 22 (36.1) | −0.341 (<0.001) |

| Yes, limited a little | 144 (45.8) | 87 (45.1) | 29 (48.3) | 28 (45.9) | |

| No, not limited at all | 118 (37.6) | 94 (48.7) | 13 (21.7) | 11 (18.0) | |

| Accomplished less than you would like (physical): | |||||

| Yes | 128 (40.8) | 51 (26.7) | 40 (66.7) | 37 (58.7) | −0.319 (<0.001) |

| No | 186 (59.2) | 140 (73.9) | 20 (33.3) | 26 (41.3) | |

| Were limited in activities (physical): | |||||

| Yes | 122 (39.1) | 50 (26.3) | 41 (68.3) | 31 (50.0) | −0.276 (<0.001) |

| No | 190 (60.9) | 140 (73.7) | 19 (31.7) | 31 (50.0) | |

| Accomplished less than you would like (emotionally): | |||||

| Yes | 81 (25.7) | 33 (17.2) | 22 (36.7) | 26 (41.3) | −0.234 (<0.001) |

| No | 234 (74.3) | 159 (82.8) | 38 (63.3) | 37 (58.7) | |

| Didn't do work or other activities as carefully as usual (emotionally): | |||||

| Yes | 79 (25.2) | 33 (17.3) | 22 (36.7) | 24 (38.7 ) | −0.216 (<0.001) |

| No | 234 (74.8) | 158 (82.7) | 38 (63.3) | 38 (61.3) | |

| Past 4 weeks, how much did pain interfere with your normal work? | |||||

| Not at all/A little bit | 201 (63.6) | 138 (71.5) | 26 (43.3) | 37 (58.7) | |

| Moderately | 81 (25.6) | 40 (20.7) | 24 (40.0) | 17 (27.0) | 0.166 |

| Quite a bit/Extremely | 34 (10.8) | 15 (7.8) | 10 (16.7) | 9 (14.3) | −0.002 |

| Past 4 weeks: Have you felt calm and peaceful? | |||||

| All of the time/Most of the time | 216 (70.4) | 147 (78.2) | 33 (57.9) | 36 (58.0) | 0.195 (<0.001) |

| A Good Bit of the Time/Some of the Time | 44 (14.3) | 22 (11.7) | 9 (15.8) | 13 (21.0) | |

| A Little of the Time/None of the Time | 47 (15.3) | 19 (10.1 ) | 15 (26.3) | 13 (21.0 ) | |

| Past 4 weeks: Did you have a lot of energy? | |||||

| All of the time/Most of the time | 140 (47.0) | 112 (58.9) | 15 (28.3) | 13 (23.6) | 0.300 (<0.001) |

| A Good Bit of the Time/Some of the Time | 69 (23.2) | 40 (21.1) | 12 (22.6) | 17 (30.9) | |

| A Little of the Time/None of the Time | 89 (29.8) | 38 (20.0) | 26 (49.1) | 25 (45.5) | |

| Past 4 weeks: Have you felt downhearted and blue? | |||||

| All of the time/Most of the time | 15 (9.3) | 8 (9.8) | 4 (9.5) | 3 (7.9) | |

| A Good Bit of the Time/Some of the Time | 24 (14.8) | 12 (14.6) | 8 (19.0) | 4 (10.5) | 0.032 |

| A Little of the Time/None of the Time | 123 (75.9) | 62 (75.6) | 30 (71.5) | 31 (81.6) | −0.65 |

| Past 4 weeks: how much of the time has your physical health or emotional problems interfered with your social activities? | |||||

| All of the time/Most of the time | 34 (10.9) | 11 (5.8) | 8 (13.6) | 15 (24.6) | −0.274 (<0.001) |

| A Good Bit of the Time/Some of the Time | 43 (13.8) | 18 (9.4) | 13 (22.0) | 12 (19.7) | |

| A Little of the Time/None of the Time | 234 (75.3) | 162 (84.8) | 38 (64.4) | 34 (55.7) | |

| CES‐D | |||||

| I was bothered by things that usually don't bother me | |||||

| Rarely or none of the time | 268 (87.0) | 170 (88.1) | 45 (78.9) | 53 (91.4) | 0.014 |

| Quite often or always | 40 (13.0) | 23 (11.9) | 12 (21.1) | 5 (8.6) | −0.794 |

| I felt that I could not shake off the blues even with help from my family or friends | |||||

| Rarely or none of the time | 276 (90.5) | 180 (94.2) | 44 (78.6) | 52 (89.7) | 0.129 |

| Quite often or always | 29 (9.5) | 11 (5.8) | 12 (21.4) | 6 (10.3) | −0.023 |

| I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing | |||||

| Rarely or none of the time | 268 (87.3) | 177 (92.2) | 45 (78.9) | 46 (79.3) | 0.176 |

| Quite often or always | 39 (12.7) | 15 (7.8) | 12 (21.1) | 12 (20.7) | −0.003 |

| I felt depressed | |||||

| Rarely or none of the time | 282 (92.2) | 179 (94.2) | 49 (84.5) | 54 (93.1) | 0.069 |

| Quite often or always | 24 (7.8) | 11 (5.8) | 9 (15.5) | 4 (6.9) | −0.205 |

| I felt that everything I did was an effort | |||||

| Rarely or none of the time | 256 (83.7) | 172 (90.5) | 39 (67.2) | 45 (77.6) | 0.202 (<0.001) |

| Quite often or always | 50 (16.3) | 18 (9.5 ) | 19 (32.8) | 13 (22.4) | |

| My sleep was restless | |||||

| Rarely or none of the time | 226 (74.3) | 144 (76.6) | 42 (72.4) | 40 (69.0) | 0.067 |

| Quite often or always | 78 (25.7) | 44 (23.4) | 16 (27.6) | 18 (31.0) | −0.236 |

| I was happy | |||||

| Rarely or none of the time | 64 (21.7) | 31 (16.8) | 14 (24.6) | 19 (35.2) | −0.159 |

| Quite often or always | 231 (78.3) | 153 (83.2) | 43 (75.4) | 35 (64.8) | −0.008 |

| I enjoyed life | |||||

| Rarely or none of the time | 32 (10.5) | 16 (8.4) | 7 (12.1) | 9 (16.1) | −0.091 |

| Quite often or always | 272 (89.5) | 174 (91.6) | 51 (87.9) | 47 (83.9) | −0.125 |

| I felt sad | |||||

| Rarely or none of the time | 262 (85.9) | 169 (89.4) | 45 (77.6) | 48 (82.8) | 0.11 |

| Quite often or always | 43 (14.1) | 20 (10.6) | 13 (22.4) | 10 (17.2) | −0.054 |

| Quality of Life | |||||

| How do you feel about life at all right now? | |||||

| Very good/Good | 226 (71.3) | 153 (78.9) | 37 (61.7) | 36 (57.1) | −0.201 (<0.001) |

| Fairly good/Neither good nor bad | 83 (26.2) | 39 (20.1) | 18 (30.0) | 26 (41.3) | |

| Pretty bad/Bad | 8 (2.5) | 2 (1.0) | 5 (8.3) | 1 (1.6) | |

| ADL | |||||

| Housekeeping | |||||

| No problem | 211 (69.6) | 166 (88.8) | 32 (57.1) | 13 (21.7) | 0.554 (<0.001) |

| Some problem | 48 (15.9) | 16 (8.6) | 16 (28.6) | 16 (26.7) | |

| Big problem/Can't do it at all | 44 (14.5) | 5 (2.7) | 8 (14.3) | 31 (51.6) | |

| Shopping | |||||

| No problem | 243 (77.9) | 180 (93.8) | 35 (60.3) | 28 (45.2) | 0.477 (<0.001) |

| Some problem | 29 (9.3) | 9 (4.7) | 10 (17.2) | 10 (16.1) | |

| Big problem/Can't do it at all | 40 (12.8) | 3 (1,6) | 13 (22.5) | 24 (38.7) | |

| Transporting | |||||

| No problem | 231 (74.3) | 179 (94.2) | 27 (45.8) | 25 (40.3) | 0.553 (<0.001) |

| Some problem | 27 (8.7) | 8 (4.2) | 15 (25.4) | 4 (6.5) | |

| Big problem/Can't do it at all | 53 (17.0) | 3 (1.6) | 17 (28.9) | 33 (53.2) | |

| Handle Finances | |||||

| No problem | 256 (86.5) | 182 (98.4) | 40 (74.1) | 34 (59.7) | 0.445 (<0.001) |

| Some problem | 21 (70.9) | 3 (1.6) | 8 (14.8) | 10 (17.5) | |

| Big problem/Can't do it at all | 19 (64.2) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (11.1) | 13 (22.8) | |

| Food preparation | |||||

| No problem | 251 (84.8) | 177 (97.3) | 41 (74.5) | 33 (55.9) | 0.444 (<0.001) |

| Some problem | 24 (8.1) | 5 (2.7) | 8 (14.5) | 11 (18.7) | |

| Big problem/Can't do it at all | 21 (7.1) | 0 (0,0) | 6 (11.0) | 15 (25.4) | |

| Bathing | |||||

| No problem | 290 (91.5) | 192 (99.0) | 56 (93.3) | 42 (66.7) | 0.382 (<0.001) |

| Some problem | 15 (4.7) | 2 (1.0) | 4 (6.7) | 9 (14.3) | |

| Big problem/Can't do it at all | 12 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (19.0) | |

| Dressing | |||||

| No problem | 297 (93.7) | 192 (99.0) | 53 (88.3) | 52 (82.5) | 0.269 (<0.001) |

| Some problem | 18 (5.7) | 1 (0.5) | 7 (11.7) | 10 (15.9) | |

| Big problem/Can't do it at all | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Toileting | |||||

| No problem | 312 (98.5) | 194 (100) | 59 (98.3) | 59 (93.6) | |

| Some problem | 3 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | 2 (3.2) | 0.175 |

| Big problem/Can't do it at all | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.2) | −0.026 |

| Transferring | |||||

| No problem | 304 (95.9) | 192 (99.0) | 58 (96.7) | 54 (85.7) | |

| Some problem | 12 (3.8) | 2 (1.0) | 2 (3.3) | 8 (12.7) | 0.22 |

| Big problem/Can't do it at all | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | −0.003 |

| Feeding | |||||

| No problem | 315 (99.4) | 194 (100) | 60 (100) | 61 (96.9) | 0.122 |

| Some problem | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.1) | −0.154 |

| Dizziness | |||||

| Dizziness or instability | |||||

| No | 180 (58.6) | 123 (63.4) | 31 (53.4) | 26 (47.3) | 0.127 |

| Yes | 127 (41.4) | 71 (36.6) | 27 (46.6) | 29 (52.7) | −0.021 |

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the validated CES‐D instrument (Carleton et al., 2013). CES‐D is self‐reported and based on the question: How often have you felt this way during the past week? There were nine possible statements associated with this question: I was bothered by things that usually don't bother me; I felt that I could not shake off the blues even with help from my family or friends; I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing; I felt depressed; I felt that everything I did was an effort; My sleep was restless; I was happy; I enjoyed life; I felt sad. All the statements had the same answer options (1 = rarely or none of the time, 2 = quite often or always). To increase the interpretability of the logistic regression analyses, an index of CES‐D was created. Each variable was dichotomised (0 = no problems, 1 = problems of some kind) and summarised to obtain a range of the index of 0–9.

Quality of life was highlighted with the question: How do you feel about life right now (1 = very good/good, 2 = fairly good/neither good nor bad, 3 = pretty bad/bad)?

To assess aspects of functioning, ADL and questions about dizziness were used.

ADL was divided into two groups according to the Katz Index; instrumental ADL (iADL) and personal ADL (pADL) (Katz, 1983). iADL included housekeeping, shopping, transporting, handling finances, and food preparation; pADL included bathing, dressing, using the toilet, transferring, and feeding. Each question had four possible answers (1 = no problem, 2 = some problem, 3 = big problem, 4 = can't do it at all). Due to low response rates in the answer alternatives big problem and can't do at all, both options were combined into ‘3 = big problem/can't do it all’. To increase the interpretability of the logistic regression analyses, two indexes were created: a iADL index and a pADL index, where each variable was dichotomised (0 = no problems, 1 = problems of some kind) and summarised. The range of the iADL index and the pADL index was 0–5.

Dizziness: To further describe an aspect of functioning, a question on whether the participants had problems with dizziness and instability (yes = 1, no = 2) was used.

Different aspects of social networks were captured by six questions: Do you think you meet your children as often as you wish (1 = yes, 2 = no); How many people do you know that you can share your innermost thoughts and feelings with (confidants)? (1 = nobody, 2 = 1–2, 3 = 3 or more); Are you satisfied with the number of confidants, or do you wish you had more or fewer (1 = I am satisfied, 2 = would like more, 3 = I would like to have fewer); Do you think you meet your friends and confidants as often as you wish (1 = yes, 2 = no)?; Does it happen that you feel lonely (1 = almost always, 2 = often, 3 = rarely, 4 = almost never; however, due to low response rates in the answer alternatives rarely and almost, both choices were combined into ‘3 = rarely/almost never’); Would anyone notice if something would happen to you (an incident, becoming ill, or something similar)? (1 = yes, pretty soon, 2 = yes, but not immediately, 3 = no, nobody).

2.3. Analysis

SPSS version 24 was used for the statistical analyses. Non‐parametric statistics (Kendall's Tau‐b) were used to analyse the differences in the groups based on the type of care received: no care (0), informal care only (1) and formal care with or without informal care (2). To further explore the associations between received care and different aspects of health, functioning and social networks, a multinomial logistic regression analysis was performed using the variables that demonstrated statistically significant associations with received care in the non‐parametric analyses. Only four of the variables demonstrated a statistically significant contribution in the initial regression model. These four variables were then included in the final multivariable regression model.

2.4. Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee in Linköping, Sweden (Dnr 225‐08). Participation in the present study was voluntary, and data collection was conducted after obtaining the participants' informed written consent.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Descriptive characteristics

The median age was 80 years. More than half of the sample were independent (61%) and did not receive any help at home, and only one‐fifth (20%) received formal care. The overall pattern was that the older age groups received more help than the younger groups. Moreover, the participants who did not have other people living in their households also reported receiving formal care (with or without informal care) to a greater extent, even if almost three‐fourths (72.5%) of them managed without formal care. Women received more care, especially formal care (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Description of the sample (n = 317) with comparisons between the three outcome groups (no care, informal care only and formal care with or without informal care) using Kendall's Tau‐b

| No Care | Informal care only | Formal care with or without informal care |

Kendall's Tau‐b (P) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 317 | 194 (61%) | 60 (19%) | 63 (20%) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Women | 167 (52.7) | 89 (45.8) | 32 (53.3) | 46 (73.0) | −0.187 (<0.001) |

| Men | 150 (47.3) | 105 (54.1) | 28 (46.7) | 17 (27.0) | |

| Age | |||||

| 75 years | 110 (34.7) | 83 (42.8) | 19 (31.7) | 8 (12.7) | 0.306 (<0.001) |

| 80 years | 95 (29.9) | 60 (30.9) | 23 (38.3) | 12 (19.0) | |

| 85 years | 68 (21.5) | 42 (21.7) | 10 (16,7) | 16 (25.4) | |

| 90 years | 44 (13.9) | 9 (4.6) | 8 (13.3) | 27 (42.9) | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 169 (53.3) | 115 (59.3) | 31 (51.7) | 23 (36.5) | 0.186 (<0.001) |

| Never married | 13 (4.1) | 9 (4.6) | 4 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Divorced | 16 (5.0) | 12 (6.2) | 2 (3.3) | 2 (3.2) | |

| Widowed | 119 (37.6) | 58 (29.9) | 23 (38.3) | 38 (60.3) | |

| Other persons in household | |||||

| Yes | 164 (51.7) | 113 (58.2) | 30 (50.0) | 21 (33.3) | −0.176 (<0.001) |

| No | 153 (48.3) | 81 (41.8) | 30 (50.0) | 42 (66.7) | |

3.2. Different aspects of health

Multimorbidity and polypharmacy appeared to be related to receiving formal care, and significantly more participants with multimorbidity and polypharmacy were among those who received some kind of care (Table 2). Quality of life was assessed as higher in the participants who received no care than in those who received formal care.

3.3. Different aspects of functioning

The participants who reported being able to independently perform daily activities received less care. Most of the participants managed the pADL on their own, but the variations in dependence were greater for the iADL.

3.4. Different aspects of social networks

As demonstrated in Table 3, to a high extent, older people reported being satisfied with the number of confidants and how often they meet with confidants; this was especially true for the participants who do not receive care. This experience was less positive among the participants who received formal care. Moreover, those who receive care were less satisfied with the number of confidants and how often they spent time with them.

TABLE 3.

Associations between aspects of social networks in the three outcome groups (no care, informal care only and formal care with or without informal care) using Kendall's Tau‐b

| No care | Informal care only | Formal care with or without informal care |

Kendall's Tau‐b (P) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 317 | 194 (61%) | 60 (19%) | 63 (20%) | ||

| Do you think you meet your children as often as you wish? | |||||

| No | 103 (34.7) | 59 (32.2) | 18 (32.7) | 26 (44.1) | −0.077 |

| Yes | 194 (65.3) | 124 (67.8) | 37 (67.3) | 33 (55.9) | −0.174 |

| How many people do you know that you can share your innermost thoughts and feelings with (trust in)? | |||||

| Nobody | 28 (8.9) | 13 (6.7) | 7 (11.7) | 8 (13.1) | |

| 1–2 | 142 (45.1) | 83 (42.8) | 29 (48.3) | 30 (49.2) | −0.119 |

| 3 or more | 145 (46.0) | 98 (50.5) | 24 (40.0) | 23 (37.7) | −0.022 |

| Are you satisfied with the number of confidants or would you wish you had more or fewer? | |||||

| I am satisfied | 278 (88.6) | 182 (94.3) | 53 (88.3) | 43 (70.5) | 0.251 (<0.001) |

| Would like more | 35 (11.1) | 11 (5.7) | 6 (10.0) | 18 (29.5) | |

| Would like to have fewer | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Do you think you meet your friends and confidants as often as you wish? | |||||

| No | 78 (24.8) | 30 (15.5) | 20 (33.3) | 28 (45.9) | −0.273 (<0.001) |

| Yes | 236 (75.2) | 163 (84.5) | 40 (66.7) | 33 (54.1) | |

| Does it happen that you feel lonely? | |||||

| Almost always/Often | 38 (12.1) | 15 (7.7) | 13 (22.0) | 10 (16.4) | −0.215 (<0.001) |

| Rarely | 82 (26.1) | 42 (21.7) | 17 (28.8) | 23 (37.7) | |

| Almost never/never | 194 (61.8) | 137 (70.6) | 29 (49.2) | 28 (45.9) | |

| Would anyone notice if something would happen to you? (incident, become ill or similar) | |||||

| Yes, pretty soon | 191 (61.6) | 118 (62.1) | 37 (61.7) | 36 (60.0) | |

| Yes, but not immediately | 111 (35.8) | 67 (35.3) | 20 (33.3) | 24 (40.0) | 0.011 |

| No, nobody | 8 (2.6) | 5 (2.6) | 3 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | −0.841 |

3.5. Relations of care and different aspects of health, functioning, and social networks

Age (higher) was related to receiving formal care, as well as to satisfaction with the number of confidants. Perceived general health was related to informal care. iADL was related to both outcomes (informal care only and formal care with or without informal care), where higher dependence on performing activities was related to receiving care (Table 4). These four variables were included in the final regression model, in which relationships with the categories for received care similar to those described above were confirmed (Table 5). In other words, the significant relationships between informal care and different aspects of health, functioning, and social networks were found in perceived health and iADL. Similarly, the significant relationships between formal care and different aspects of health, functioning, and social networks were found in iADL and satisfaction with number of confidants.

TABLE 4.

Multinomial regression: variables associated with informal care only and formal care with or without informal care

|

Informal care only (n = 60) |

Formal care with or without informal care (n = 59) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXB (B) | CI | EXB (B) | CI | |

| Gender | 1.153 | 0.509–2.614 | 0.541 | 0.206–1.420 |

| Age | 1.031 | 0.954–1.115 | 1.178*** | 1.080–1.287 |

| Other persons in household | 0.872 | 0.203–3.750 | 2.324 | 0.463–11.672 |

| Multimorbidity | 1.053 | 0.462–2.400 | 1.057 | 0.401–2.748 |

| Polypharmacy | 0.906 | 0.407–2.014 | 0.904 | 0.358–2.280 |

| General perceived health | 2.017* | 1.138–3.574 | 0.881 | 0.462–1.682 |

| CES‐D index | 1.008 | 0.984–1.032 | 1.017 | 0.992–1.043 |

| iADL | 2.360*** | 1.719–3.239 | 3.136*** | 2.216–4.439 |

| Satisfaction with life | 1.151 | 0.786–1.686 | 1.249 | 0.781–1.198 |

| Satisfaction with number of confidants | 1.261 | 0.384–4.141 | 5.223** | 1.561–17.480 |

| Do you meet confidants as often as you wish? | 0.700 | 0.291–1.684 | 0.526 | 0.198–1.394 |

| Feelings of loneliness | 0.704 | 0.411–1.203 | 1.044 | 0.545–2.000 |

Reference category No care (n = 194).

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

TABLE 5.

Final model of multinomial regression: variables associated with informal care and formal care with or without informal care

|

Only informal care (n = 60) |

Formal care with or without informal care (n = 61) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXB (B) | CI | EXB (B) | CI | |

| Age | 1.025 | 0.954–1.101 | 1.189*** | 1.098–1.287 |

| General perceived health | 2.370** | 1.439–3.902 | 1.112 | 0.631–1.960 |

| iADL | 2.399*** | 1.775–3.244 | 3.180*** | 2.297–4.403 |

| Satisfaction with number of confidants | 2.071 | 0.717–5.986 | 6.971*** | 2.385–20.377 |

Reference category No care (n = 194).

p < .01

p < .001.

4. DISCUSSION

This study aimed to describe and analyse different aspects of health, functioning and social networks, and how they relate to formal and informal care in the home among older adults. The descriptive analyses demonstrate that the situation of older people receiving care in their own home is complex. Although functional and health aspects seem to be related to the outcome of the receipt of care, they are not the only factors that have an impact on care. In our study, satisfaction with the number of confidants is significantly related to use of formal care, and also that those receiving formal care perceive loneliness to higher extent. According to Svanström et al. (2013) care might contribute to an older person's perceived loneliness and insecurity in their own homes. This is also emphasised by the National Board of Health and Welfare (2019) which states that older people who are not satisfied with the care they receive also experience more loneliness. Even though we have no information about the satisfaction with care in our study, our results, as well as others, imply that loneliness seems to be a factor that needs to be considered among people receiving formal care in their own home.

Functional and health aspects are related to the impact of care in several ways. Previous studies indicate that perceived quality of life is significantly related to regularly needing help with ADL (Hellstrom et al., 2004). This is in line with present study, where older people need help in daily life to a larger extent, often involving both informal and formal caregivers. These findings are in line with those reported by Bolin et al. (2008) and Büscher et al. (2011), indicating that there is a need to be aware of more aspects than functioning and health when organising care in the home of older people. You also must consider the needs of the older person and provide home care with a focus on self‐determination and independence (Jarling et al., 2018).

In our study informal care is more common among the participants who need help and support with iADL. Efforts made by informal caregivers are common and very important in the welfare systems in Sweden today. There is often a partner (cohabiting or not) who can take a significant amount of responsibility. Previous studies have shown that married women and men with limitations in daily life receive most of their care from their spouses (Maresova et al., 2020; Ris et al., 2019). Men receive care from their spouses to a greater extent than women (Glauber, 2017). Although our study did not investigate gender aspects of care, it seems reasonable to emphasise older women's need for formal support, as they often outlive their partners and therefore have less informal care which is also in line with the findings of Sigurdardottir et al. (2012), Szebehely and Trydegård (2012), and Wimo et al. (2017). However, the responsibility taken by informal caregivers can be extremely stressful and lead to burnout and a changed life situation (Jarling et al., 2019; Peetoom et al., 2016).

Further analysis of our data in a multinomial logistic regression offered a somewhat different picture in comparison to the descriptive analyses. The health aspects of multimorbidity and polypharmacy do not have any significant correlation with receipt of care. Kendall's Tau‐b analyses demonstrate significant differences, where older people in use of formal care, to a greater extent, suffer from multimorbidity and polypharmacy. It is not surprising that ADL is significant when receiving home care, especially for people in the higher age group; neither is it surprising that formal care is often decided based on ADL. This assumption is also in line with the perspectives of nurses working in home care ranking characteristics for predicting home care needs (van den Bulck et al., 2019). However, in addition to the lack of association among health factors, the results demonstrate a significant correlation between the receipt of formal care and satisfaction with the number of confidants. In our sample, most participants are satisfied with the number of confidants. Nevertheless, according to the logistic regression analyses, older people who receive formal care are less satisfied with the number of confidants than those who did not receive any type of care. A possible explanation is that home care often is detailed and regulated in time and therefore the caregivers do not have time to create a deeper relationship with the older person between the efforts that are to be made. Care needs to be provided with continuity to create a consistent and stable relationship with the person being cared for and to provide room for the relationship to grow (Hughes & Burch, 2020).

If the older person who is being cared for does not have many confidants or having less functional possibilities to go outside and meet friends and family, one can assume that the professional caregiver becomes the confidant and the proxy for other significant persons. Findings also show that older person's relationship with the caregiver becomes very important for how he/she estimates the care, for example, by having someone to trust (Hughes & Burch, 2020; Lundgren et al., 2018, 2019) or being able to live their life as before (Haex et al., 2020). However, professional caregivers face paradoxes that are difficult to deal with, such as the care receiver's care needs versus the informal caregiver's ability to cope (Janssen et al., 2014). This adds to the complexity of caring for a person in their home as well as being cared for.

The results of the relationship between formal care and satisfaction with confidants imply that professionals in formal care may play an important social role for the older person. Therefore, it is important to understand the patient from a holistic perspective. A human being is more than just a recipient of care, and more than just symptoms and a diagnosis. Professional caregivers need to understand how older persons experience their life situations and how they express their needs (Dahlberg, 1996). According to Ernsth Bravell et al. (2020) formal competence, such as education, contributes to a sense of security for the older person. When formal competence is lacking, it may be difficult to accurately assess the needs of someone who requires extensive care, and thus provide effective care.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

One strength of the OCTO‐2 study is the richness of the data; the data contained many variables and provided a comprehensive picture to respond to the purpose of the study. Even though data were collected some years ago, they are still considered relevant to answer the research questions. For this study, data from OCTO‐2 was used for secondary analyses, thus presenting both benefits and limitations. One advantage of studying existing data is that it safeguards the vulnerability of the older population. One disadvantage is that the variables were already determined, so there was no possibility of adjusting to better fit the study's purpose. The study used random selection; hence, some choices were made. For example, older people with cognitive impairments were excluded from participation. This selection needs to be considered when interpreting the results. Natural bias also occurred because the oldest group of participants contained the fewest number of people.

One bias for the exclusion criteria was cognitive failure; thus, the people who agreed to participate in the study probably succeeded relatively well in terms of living on their own. The older a person is, the greater the risk/chance of receiving some kind of help. Therefore, it could be assumed that if people with cognitive impairment had participated in the study, there would probably have been more people reporting that they had received help.

5. CONCLUSION

The situation of older people who are cared for in their own homes and who receive formal and informal home care is complex. The results show the importance of a holistic perspective that includes the older person's experiences and also highlight the importance of considering social perspectives and relationships in home care. Many aspects need to be taken into account to determine the older people's needs in home care, which requires competence, openness and sensitivity. In today's care, which is increasingly controlled by time and resources in combination with cutbacks and a lack of professional caregivers, this is a challenge. More research is needed to further improve our understanding of the older people's experience of being cared for at home and how the relationship with the professional caregivers can contribute to security and well‐being for the older people cared for in their own home.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

No conflict of interest to declare.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTION

The authors have made an active contribution to the conception and design and/or analysis and interpretation of the data and/or the drafting of the paper and all have critically reviewed the content. The manuscript has been read and approved for submission by all authors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the study nurses, Gerd Martinson, Gun Karlsson and Anna‐Carin Säll Grahnat, for their excellent work during the data collection process.

Jarling, A. , Rydström, I. , Fransson, E. I. , Nyström, M. , Dalheim‐Englund, A.‐C. , & Bravell, M. E. (2022). Relationships first: Formal and informal home care of older adults in Sweden. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30, e3207–e3218. 10.1111/hsc.13765

Funding information

The OCTO 2 study was originally supported by Futurum, Jönköping, Region Jönköping County (grant number FUTURUM‐13282) and the Eva and Oscar Ahrén Foundation.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- Bolin, K. , Lindgren, B. , & Lundborg, P. (2008). Informal and formal care among single‐living elderly in Europe. Health Economics, 17(3), 393–409. 10.1002/hec.1275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravell, M. E. , Berg, S. , & Malmberg, B. (2008). Health, functional capacity, formal care, and survival in the oldest old: A longitudinal study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 46(1), 1–14. 10.1016/j.archger.2007.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büscher, A. , Astedt‐Kurki, P. , Paavilainen, E. , & Schnepp, W. (2011). Negotiations about helpfulness—The relationship between formal and informal care in home care arrangements. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 25(4), 706–715. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2011.00881.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushardt, R. L. , Massey, E. B. , Simpson, T. W. , Ariail, J. C. , & Simpson, K. N. (2008). Polypharmacy: Misleading, but manageable. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 3(2), 383–389. 10.2147/cia.s2468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton, R. N. , Thibodeau, M. A. , Teale, M. J. N. , Welch, P. G. , Abrams, M. P. , Robinson, T. , & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2013). The center for epidemiologic studies depression scale: A review with a theoretical and empirical examination of item content and factor structure. PLoS One, 8(3), e58067. 10.1371/journal.pone.0058067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg, K. (1996). Intersubjective meeting in holistic caring: A Swedish perspective. Nursing Science Quarterly, 9(4), 147–151. 10.1177/089431849600900405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernsth Bravell, M. (2017). Medical treatment. In Blomqvist K., Edberg A. K., Ernsth Bravell M., & Wiik H. (Eds.), Care of older people (pp. 465–475). Studentlitteratur. [Google Scholar]

- Ernsth Bravell, M. , Bennich, M. , & Walfridsson, C. (2020). “In August, I counted 24 different names”: Swedish older adults' experiences of home care. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 40(9), 1020–1028. 10.1177/0733464820917568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin, M. , Lapointe, L. , Hudon, C. , Vanasse, A. , Ntetu, A. L. , & Maltais, D. (2004). Multimorbidity and quality of life in primary care: A systematic review. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 2, 51. 10.1186/1477-7525-2-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fristedt, S. , Kammerlind, A.‐S. , Ernsth Bravell, M. , & Fransson, E. (2016). Concurrent validity of the Swedish version of the Life‐Space Assessment Questionnaire. BMC Geriatrics, 16, 181. 10.1186/s12877-016-0357-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandek, B. , Ware, J. E. , Aaronson, N. K. , Apolone, G. , Bjorner, J. B. , Brazier, J. E. , Bullinger, M. , Kaasa, S. , Leplege, A. , Prieto, L. , & Sullivan, M. (1998). Cross‐validation of item selection and scoring for the SF‐12 Health Survey in nine countries: Results from the IQOLA Project. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 1171–1178. 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00109-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauber, R. (2017). Gender differences in spousal care across the later life course. Research on Aging, 39(8), 934–959. 10.1177/0164027516644503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haex, R. , Thoma‐Lürken, T. , Beurskens, A. J. H. M. , & Zwakhalen, S. M. G. (2020). How do clients and (In)formal caregivers experience quality of home care? A qualitative approach. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(1), 264–274. 10.1111/jan.14234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrom, Y. , Persson, G. , & Hallberg, I. R. (2004). Quality of life and symptoms among older people living at home. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 48, 584–593. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03247.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, S. , & Burch, S. (2020). ‘I'm not just a number on a sheet, I'm a person’: Domiciliary care, self and getting older. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(3), 903–912. 10.1111/hsc.12921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, B. , Abma, T. , & Van Regenmortel, T. (2014). Paradoxes in the care of older people in the community: Walking a tightrope. Ethics and Social Welfare, 8(1), 39–56. 10.1080/17496535.2013.776092 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarling, A. , Rydström, I. , Ernsth Bravell, M. , Nyström, M. , & Dalheim‐Englund, A.‐C. (2018). Becoming a guest in your own home: Home care in Sweden from the perspective of older people with multimorbidities. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 13(3), e12194. 10.1111/opn.12194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarling, A. , Rydstrom, I. , Ernsth‐Bravell, M. , Nystrom, M. , & Dalheim‐Englund, A.‐C. (2019). A responsibility that never rests—The life situation of a family caregiver to an older person. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 34(1), 44–51. 10.1111/scs.12703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammerlind, A.‐S.‐ C. , Fristedt, S. , Ernsth Bravell, M. , & Fransson, E. I. (2014). Test–retest reliability of the Swedish version of the Life‐Space Assessment Questionnaire among community‐dwelling older adults. Clinical Rehabilitation, 28(8), 817–823. 10.1177/0269215514522134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz, S. (1983). AssessingSelf‐maintenance: Activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 31(12), 721–727. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1983.tb03391.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y. , Barken, R. , & Gonzales, E. (2020). Utilization of formal and informal home care: How do older Canadians' experiences vary by care arrangements? Journal of Applied Gerontology, 39(2), 129–140. 10.1177/0733464817750274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren, D. , Ernsth Bravell, M. , Börjesson, U. , & Kåreholt, I. (2018). The association between psychosocial work environment and satisfaction with old age care among care recipients. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 39(7), 785–794. 10.1177/0733464818782153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundgren, D. , Ernsth Bravell, M. , Börjesson, U. , & Kåreholt, I. (2019). The impact of leadership and psychosocial work environment on recipient satisfaction in nursing homes and home care. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, 5, 2333721419841245. 10.1177/2333721419841245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maresova, P. , Lee, S. , Fadeyi, O. O. , & Kuca, K. (2020). The social and economic burden on family caregivers for older adults in the Czech Republic. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 1–12. 10.1186/s12877-020-01571-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Board of Health and Welfare . (2019). Progress report for health care and social care for older people. National Board of Health and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Peetoom, K. K. B. , Lexis, M. A. S. , Joore, M. , Dirksen, C. D. , & De Witte, L. P. (2016). The perceived burden of informal caregivers of independently living elderly and their ideas about possible solutions. A mixed methods approach. Technology and Disability, 28(1–2), 19–29. 10.3233/TAD-160441 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ris, I. , Schnepp, W. , & Mahrer Imhof, R. (2019). An integrative review on family caregivers' involvement in care of home‐dwelling elderly. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(3), 95–111. 10.1111/hsc.12663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg, L. , Nilsson, I. , Rosenberg, L. , Borell, L. , & Boström, A.‐M. (2019). Home care services for older clients with and without cognitive impairment in Sweden. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(1), 139–150. 10.1111/hsc.12631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SFS 2001:453 . Social Services Act. Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- SFS 2017:30 . Health Care Act. Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdardottir, S. H. , Sundstrom, G. , Malmberg, B. O. , & Bravell, M. E. (2012). Needs and care of older people living at home in Iceland. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 40(1), 1–9. 10.1177/1403494811421976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svanström, R. , Sundler, A. J. , Berglund, M. , & Westin, L. (2013). Suffering caused by care—Elderly patients' experiences in community care. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well‐being, 8, 20603. 10.3402/qhw.v8i0.20603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinkels, J. C. , Suanet, B. , Deeg, D. J. H. , & Broese Van Groenou, M. I. (2016). Trends in the informal and formal home‐care use of older adults in the Netherlands between 1992 and 2012. Ageing and Society, 36(9), 1870–1890. 10.1017/S0144686X1500077X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szebehely, M. , & Trydegård, G.‐B. (2012). Home care for older people in Sweden: A universal model in transition. Health & Social Care in the Community, 20(3), 300–309. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01046.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valderas, J. M. , Starfield, B. , Sibbald, B. , Salisbury, C. , & Roland, M. (2009). Defining comorbidity: Implications for understanding health and health services. Annals of Family Medicine, 7(4), 357–363. 10.1370/afm.983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bulck, A. , Metzelthin, S. , Elissen, A. , Stadlander, M. , Stam, J. , Wallinga, G. , & Ruwaard, D. (2019). Which client characteristics predict home‐care needs? Results of a survey study among Dutch home‐care nurses. Health & Social Care in the Community, 27(1), 93–104. 10.1111/hsc.12611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimo, A. , Elmståhl, S. , Fratiglioni, L. , Sjölund, B.‐M. , Sköldunger, A. , Fagerström, C. , Berglund, J. , & Lagergren, M. (2017). Formal and informal care of community‐living older people: A population‐based study from the Swedish National Study on Aging and Care. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 21(1), 17–24. 10.1007/s12603-016-0747-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.