Dear editor,

Psychotropic polypharmacy and long‐term benzodiazepine receptor agonist (BzRA) use are major health issues as they can increase the risk of adverse effects. To promote the appropriate use of psychotropic drugs in Japan, medical fee reductions were implemented four times between 2012 and 2018 (Table S1). 1

This observational study aimed to evaluate the effect of medical fee revisions on the polypharmacy and prescription of high‐potency psychotropics by distinguishing between before and after intervention periods using a Japan Medical Data Center (JMDC) dataset containing all medical fee data of health insurance service subscribers aged 0–74 years (workers and their family members) (Table S2). Medical information of health insurance service subscribers who visited any department of a medical institution (hospitals, clinics, etc.) every April from 2005 to 2019 and were prescribed psychotropic drugs was extracted. Dosages of sulpiride <300 and ≥300 mg/day were considered antidepressant and antipsychotic dosages, respectively. The potency of psychotropics was calculated based on the psychotropic dose equivalence in Japan. 2 Drugs not listed in the psychotropic dose equivalence in Japan were defined as follows: flunitrazepam 1 mg/day = suvorexant 20 mg/day = ramelteon 8 mg/day and chlorpromazine 100 mg/day = asenapine 2.5 mg/day = brexpiprazole 0.5 mg/day (Table S3). The proportion of patients prescribed three or more psychotropics—such as anxiolytics, hypnotics, antidepressants, and antipsychotics—(polypharmacy rate) among the total number of prescribed psychotropics was calculated. Subsequently, the proportions of those prescribed high‐potency psychotropics among those prescribed psychotropics (rate of prescription of high‐potency psychotropics) were calculated. High‐potency anxiolytics, hypnotics, antidepressants, and antipsychotics were defined as those equivalent to >15 mg/day diazepam, >2 mg/day flunitrazepam, >300 mg/day imipramine, and >600 mg/day chlorpromazine, respectively. The rates of polypharmacy and prescription of high‐potency psychotropics were adjusted using the Japanese annual vital statistics. We set as benchmarks a reduction in the rates of the polypharmacy and prescriptions of high‐potency psychotropics to qualify the intervention as beneficial.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Akita University Graduate School of Medicine (approval number: 2352). The study was conducted per the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 1989 and the International Conference on Harmonization Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. As we analyzed an anonymized dataset, informed consent was waived.

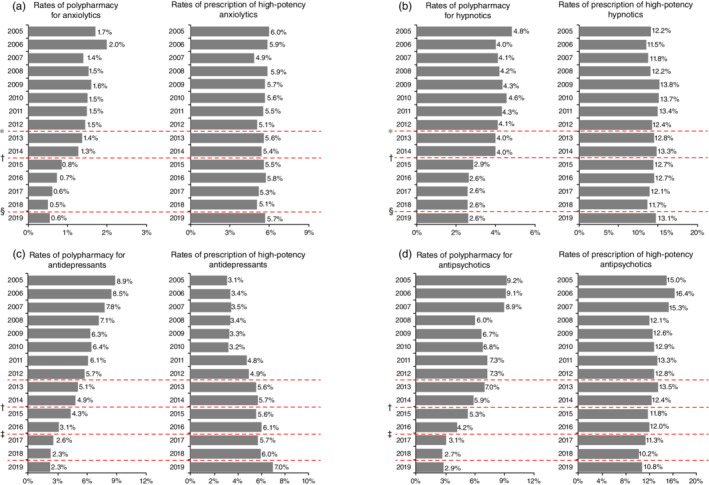

Figure 1 shows changes in the rates of polypharmacy and prescription of high‐potency psychotropics every April from 2005 to 2019 (Tables [Link], [Link], [Link], [Link], [Link], Figs [Link], [Link], [Link], [Link], [Link]). Rates of polypharmacy of all four psychotropics were considered to have decreased. However, the polypharmacy rates of anxiolytics and hypnotics from 2015 onward and antidepressants and antipsychotics from 2017 onward remained stable. In contrast, the rates of prescription of high‐potency antipsychotics decreased, those of anxiolytics and hypnotics remained generally unchanged, and those of antidepressants increased.

Fig. 1.

Patients prescribed three or more drugs and those prescribed high‐potency psychotropic drugs, including (a) anxiolytics, (b) hypnotics, (c) antidepressants, and (d) antipsychotics. Based on the census data, the rates of polypharmacy and prescription of high‐potency psychotropic drugs were adjusted for age based on 5‐year age groups and sex. The figure on the left shows the proportion of subscribers who were prescribed three or more of each class of psychotropic drugs among subscribers who were prescribed psychotropic drugs every April between 2005 and 2019. The figure on the right shows the proportion of subscribers prescribed high‐potency psychotropic drugs among subscribers prescribed psychotropic drugs. High‐potency anxiolytics, hypnotics, antidepressants, and antipsychotics were defined as those equivalent to >15 mg/day diazepam, >2 mg/day flunitrazepam, >300 mg/day imipramine, and >600 mg/day chlorpromazine, respectively. †Revision in 2012. ‡Revision in 2014. §Revision in 2016. ¶Revision in 2018.

It is difficult to reduce the prescribed dosage or discontinue the use of BzRAs, the most frequently prescribed anxiolytics and hypnotics, due to physical dependence. 3 Patients who do not successfully reduce or discontinue BzRAs may require health policy and medical intervention. Cognitive‐behavioral therapy (CBT) may be considered in patients with anxiety disorders who cannot reduce or discontinue anxiolytic use; CBT promotes the discontinuation of both short and long‐term anxiolytic use. 4 In contrast, CBT for insomnia facilitates the short‐term discontinuation of benzodiazepines; however, the effects may not last long. 5 Therefore, new long‐term effective treatments for discontinuing hypnotics in patients with insomnia are required. Throughout the study period, polypharmacy rates decreased for antidepressants, whereas the rates of prescription of high‐potency psychotropics increased annually. Although guidelines recommend that antidepressants be prescribed as monotherapy when treating depression, 6 , 7 patients suffering from depression failed to achieve remission with antidepressant monotherapy. 8 The increased rates of prescription of high‐potency antidepressants in this study may be due to combination therapy of antidepressants for patients who did not achieve remission with antidepressant monotherapy. Rates of polypharmacy and prescription of high‐potency antipsychotics decreased over time. Schizophrenia treatment guidelines recommend using antipsychotic monotherapy, possibly promoting appropriate antipsychotic use. 9 , 10

There were some limitations. First, it is unclear to what extent the JMDC dataset represents the general Japanese population. Also, this study could not exclude other societal factors, besides medical fee revisions, that might have influenced psychotropic prescribing during the study period.

In conclusion, our results indicate that medical fee revision significantly reduced the polypharmacy rates for all psychotropic drugs. However, fee revision did not reduce the prescription rates of high‐potency psychotropics other than antipsychotics. Further studies examining the effects of medical fee revisions for reducing long‐term BzRAs use are warranted.

Disclosure statement

Masahiro Takeshima has received speaker's honoraria from Daiichi Sankyo Company, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Meiji Seika Pharma, Viatris Pharmaceuticals Japan, and Yoshitomi Pharmaceutical, and research grants from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, EISAI, Shionogi and the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (R3‐21GC1016) outside the submitted work. Yoshikazu Takaesu has received speaker's honoraria from Takeda Pharmaceutical, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Kyowa Pharmaceutical, EISAI, MSD, and Yoshitomi Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work. Kazuo Mishima has received speaker's honoraria from EISAI Co., Ltd., Nobelpharma Co., Ltd., and MSD Inc., and research grants from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (19GC1012, 21GC0801) outside the submitted work. Mizuki Kudo has received speaker's honoraria from Meiji Seika Pharma outside the submitted work. Minori Enomoto, Masaya Ogasawara, Yu Itoh, Kazuhisa Yoshizawa, and Dai Fujiwara have no competing interests to declare.

Supporting information

Fig. S1 Trends in the rates of polypharmacy and prescription of high‐potency anxiolytics over time.

Fig. S2 Trends in the rates of polypharmacy and prescription of high‐potency hypnotics over time.

Fig. S3 Trends in the rates of polypharmacy and prescription of high‐potency antidepressants over time.

Fig. S4 Trends in the rates of polypharmacy and prescription of high‐potency antipsychotics over time.

Fig. S5 Trends in the monthly prescription rates of psychotropic drugs over time.

Table S1 Details of the medical fee revisions to reduce psychotropic polypharmacy and long‐term use of benzodiazepine receptor agonists in Japan.

Table S2 Demographic data of the subscribers to the health insurance service.

Table S3 List of the psychotropic drugs that can be prescribed in Japan and their potencies.

Table S4 Prescription of concomitant psychotropic drugs.

Table S5 The proportion of those prescribed three or more psychotropic drugs among subscribers to the health insurance service who were prescribed psychotropic drugs (by 5‐year age group and sex).

Table S6 Potency of psychotropics.

Table S7 The proportion of those prescribed high‐potency psychotropics among subscribers to the health insurance service who were prescribed psychotropic drugs (by 5‐year age group and sex).

Table S8 Monthly prescription rate of psychotropics (by 5‐year age group and sex).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English‐language editing. All authors had full access to the data included in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analyses. This study was supported by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (R3‐21GC1016).

References

- 1. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . Medical fee revision (in Japanese). [Cited 27 January 2022.] Available from https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000106602.html

- 2. Japan Psychiatric Rating Scales Association . Psychotropic dose equivalence in Japan. 2017. [Cited 27 January 2022.] Available from http://jsprs.org/toukakansan/2017ver/

- 3. Rickels K, Case WG, Downing RW, Winokur A. Long‐term diazepam therapy and clinical outcome. JAMA 1983; 250: 767–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Takeshima M, Otsubo T, Funada D et al. Does cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders assist the discontinuation of benzodiazepines among patients with anxiety disorders? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2021; 75: 119–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Takaesu Y, Utsumi T, Okajima I et al. Psychosocial intervention for discontinuing benzodiazepine hypnotics in patients with chronic insomnia: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2019; 48: 101214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kennedy SH, Lam RW, McIntyre RS et al. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) 2016 clinical guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: Section 3. Pharmacological treatments. Can. J. Psychiatr. 2016; 61: 540–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Japanese Society of Mood Disorders . Japanese Society of Mood Disorders Guidelines II. Depression. Igakusyoin, Tokyo, Japan, 2016; 51–70 (in Japanese); (DSM‐5)/Major depressive disorder. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR et al. Acute and longer‐term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: A STAR*D report. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006; 163: 1905–1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Taylor DM, Barnes TR, Young AH. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley‐Blackwell; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Japanese Society of Neuropsychopharmacology . Guideline for pharmacological therapy of schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacol. Rep. 2021; 41: 266–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 Trends in the rates of polypharmacy and prescription of high‐potency anxiolytics over time.

Fig. S2 Trends in the rates of polypharmacy and prescription of high‐potency hypnotics over time.

Fig. S3 Trends in the rates of polypharmacy and prescription of high‐potency antidepressants over time.

Fig. S4 Trends in the rates of polypharmacy and prescription of high‐potency antipsychotics over time.

Fig. S5 Trends in the monthly prescription rates of psychotropic drugs over time.

Table S1 Details of the medical fee revisions to reduce psychotropic polypharmacy and long‐term use of benzodiazepine receptor agonists in Japan.

Table S2 Demographic data of the subscribers to the health insurance service.

Table S3 List of the psychotropic drugs that can be prescribed in Japan and their potencies.

Table S4 Prescription of concomitant psychotropic drugs.

Table S5 The proportion of those prescribed three or more psychotropic drugs among subscribers to the health insurance service who were prescribed psychotropic drugs (by 5‐year age group and sex).

Table S6 Potency of psychotropics.

Table S7 The proportion of those prescribed high‐potency psychotropics among subscribers to the health insurance service who were prescribed psychotropic drugs (by 5‐year age group and sex).

Table S8 Monthly prescription rate of psychotropics (by 5‐year age group and sex).