Abstract

Attachment theory´s core hypotheses (universality, normativity, sensitivity, and competence) are assumed to be applicable worldwide. However, the majority of studies on attachment theory have been conducted in Western countries, and the extent to which these core hypotheses are supported by research conducted in Latin America has never been systematically addressed. The purpose of this systematic narrative literature review is to provide an integrative discussion of the current body of empirical studies concerning attachment theory conducted in Latin American countries. For that purpose, a search was conducted in four electronic databases (Web of Science, PsycInfo, SciELO, and Redalyc) and 82 publications on attachment and/or sensitivity met inclusion criteria. None of the studies reported cases in which an attachment relationship was absent, and a predominance of secure attachment patterns was found, mainly for non‐risk samples (NRS). Sensitivity levels were generally deemed adequate in NRS, and related to attachment quality. Attachment security and caregivers’ sensitivity were positively associated with child outcomes. Attachment‐based intervention studies mostly showed efficacy. In conclusion, Latin American research supports the key theoretical assumptions of attachment theory, mainly in samples of urban middle‐class NRS. However, the field of attachment‐related research would be enriched by also investing in Latin American studies on caregiving rooted in local concepts and theories.

Keywords: attachment; attachment theory; Latin America; parenting; sensitivity; América Latina; teoría de la afectividad; afectividad; sensibilidad; crianza; Mots clés: Amérique Latin; théorie de l'attachement; attachement; sensibilité; parentage; Schlüsselwörter: Lateinamerika; Bindungstheorie; Bindung; Sensibilität; Elternschaft; キーワード:ラテンアメリカ、愛着理論、アタッチメント、感受性、子育て; 关键词:拉丁美洲, 依恋理论, 依恋, 敏感性, 育儿; الكلمات الرئيسية: أمريكا اللاتينية ، نظرية التعلق ، التعلق ، الحساسية ، التربية

Resumen

Trasfondo: Se asume que las hipótesis centrales de la teoría de afectividad (universalidad, normatividad, sensibilidad y competencia) son aplicables en todo el mundo. La mayoría de los estudios sobre la teoría de afectividad, sin embargo, se han realizado en países occidentales, y sistemáticamente nunca se ha discutido hasta qué punto la investigación llevada a cabo en América Latina apoya las hipótesis centrales. Objetivo: El propósito de esta sistemática revisión de la información narrativa es aportar una discusión integrada del actual cuerpo de estudios empíricos acerca de la teoría de afectividad llevados a cabo en países de América Latina. Método: Se llevó a cabo una investigación en cuatro bases electrónicas de datos (Red de la Ciencia, PsycInfo, SciELO y Redalyc) y 82 publicaciones sobre la afectividad y/o la sensibilidad reunieron los criterios de inclusión. Resultados: Ninguno de los estudios reportó casos en los cuales una relación de afectividad estaba ausente, y se encontró una predominancia de patrones de afectividad segura, principalmente en las muestras sin riesgo. Por lo general, los niveles de sensibilidad fueron considerados adecuados en las muestras sin riesgo y relacionados con la calidad de la afectividad. La seguridad de la afectividad y la sensibilidad de quienes prestan el cuidado se asociaron positivamente con los resultados en el niño. Los estudios sobre la intervención con base en la afectividad por la mayor parte mostraron eficacia. Conclusiones: La investigación en América Latina apoya las suposiciones teóricas claves de la teoría de afectividad, principalmente en grupos muestras urbanos de clase media y muestras sin riesgo. El campo de la investigación relacionada con la afectividad pudiera, sin embargo, beneficiarse de invertir también en estudios en América Latina sobre la prestación de cuidado arraigada en conceptos y teorías locales.

Résumé

Contexte: On assume que les hypothèses fondamentales de la théorie de l'attachement (universalité, normativité, sensibilité et compétence) sont applicables au monde entier. Cependant la majorité des études sur la théorie de l'attachement ont été faites dans des pays occidentaux et la mesure dans laquelle ces hypothèses fondamentales sont soutenues par des recherches faites en Amérique Latine n'a jamais été abordée de manière systématique. But : Le but de cette revue systématique de la littérature et des recherches est d'offrir une discussion intégrée du corpus d’études empiriques actuel concernant la théorie de l'attachement, faites dans des pays d'Amérique Latine. Méthodes : Une recherche a été faite dans quatre bases de données électroniques (Web of Science, PsycInfo, SciELO, and Redalyc) et 82 publications sur l'attachement et/ou la sensibilité ont rempli les critères d'inclusion. Résultats : Aucune des études n'a fait état de cas où la relation d'attachement était absente et une prédominance de patterns d'attachement sécure a été trouvée, essentiellement pour les échantillons sans risque. Les niveaux de sensibilité étaient généralement considérés comme étant adéquate chez les échantillons sans risque et liés à la qualité de l'attachement. La sécurité de l'attachement et la sensibilité des personnes prenant soin des enfants étaient fortement liées aux résultats de l'enfant. Les études sur l'intervention basée sur l'attachement ont dans l'ensemble démontré leur efficacité. Conclusions : Les recherches sur l'Amérique Latine soutiennent les hypothèses théoriques clés de la théorie de l'attachement, essentiellement dans les échantillons d’échantillons sans risque, urbains et de classe moyenne. Cependant le domaine des recherches liées à l'attachement serait enrichi si l'on investissait aussi dans des études sur l'Amérique Latine portant sur des modes de soin enracinés dans les concepts et les théories locales.

Zusammenfassung

Lateinamerikanische Bindungsstudien: Eine narrative Überblicksarbeit

Hintergrund: Es wird angenommen, dass die Kernhypothesen der Bindungstheorie (Universalität, Normativität, Sensibilität und Kompetenz) weltweit anwendbar sind. Die meisten Studien zur Bindungstheorie wurden jedoch in westlichen Ländern durchgeführt und es wurde nie systematisch untersucht, inwieweit diese Kernhypothesen durch Forschung in Lateinamerika gestützt werden.

Ziel: Ziel dieser systematischen, narrativen Literaturübersicht ist es, eine integrative Diskussion der aktuellen empirischen Studien zur Bindungstheorie zu ermöglichen, die in lateinamerikanischen Ländern durchgeführt wurden.

Methode: Eine Suche in vier elektronischen Datenbanken (Web of Science, PsycInfo, SciELO und Redalyc) wurde durchgeführt. 82 Veröffentlichungen zum Thema Bindung und/oder Sensibilität erfüllten die Einschlusskriterien.

Ergebnisse: In keiner der Studien wurde über Fälle berichtet, in denen eine Bindungsbeziehung fehlte, und es wurden überwiegend sichere Bindungsmuster gefunden ‐ hauptsächlich innerhalb von Nicht‐Risikostichproben. Die Sensibilitätsniveaus wurden in Nicht‐Risikostichproben im Allgemeinen als angemessen angesehen und hingen mit der Bindungsqualität zusammen. Bindungssicherheit und Sensibilität der Bezugspersonen standen in einem positiven Zusammenhang mit Outcomes bei den Kindern. Studien zu bindungsbasierten Interventionen zeigten überwiegend Wirksamkeit.

Schlussfolgerungen: Die lateinamerikanische Forschung unterstützt die wichtigsten theoretischen Annahmen der Bindungstheorie, vor allem in Stichproben aus der städtischen Mittelschicht, die nicht zu Risikogruppen gehören. Das Feld der Bindungsforschung würde jedoch bereichert, wenn auch lateinamerikanische Studien zur Kinderbetreuung durchgeführt würden, die auf lokalen Konzepten und Theorien beruhen.

抄録

ラテンアメリカの愛着研究:ナラティブ・レビュー

背景: 愛着理論の中核的仮説(普遍性、規範性、感受性、有能性)は、世界中に通用するものと推定される。しかし、愛着理論に関する研究の大半は欧米で行われており、ラテンアメリカで行われた研究によってこれらの中核的仮説がどの程度裏付けされているかは、これまで体系的に扱われたことがなかった。

目的:この体系的なナラティブ文献レビューの目的は、ラテンアメリカ諸国で行われた愛着理論に関する現在の実証的一連の研究について統合的な議論を提供することである。

方法: 4つの電子データベース(Web of Science, PsycInfo, SciELO, Redalyc)と、選択基準を満たした愛着および/または感受性に関する82の出版物で検索が実施された。

結果:主に非リスクのサンプルについて、愛着関係が見られないケースを報告する研究はなく、安定型愛着パターンが優勢であることがわかった。非リスクのサンプルでは、感受性のレベルは概して適切であり、愛着の質に関係していた。愛着の安全性と養育者の感受性は、子どもの転帰と正の相関があった。愛着の観点に基づいた介入研究は、そのほとんどが有効性を示していた。

結論:ラテンアメリカの研究は、主に都市の中流階級の非リスクのサンプルにおいて、愛着理論の主要な理論的仮説を裏付けている。しかし、愛着に関連する研究の分野は、地域の概念や理論に根ざした養育に関するラテンアメリカの研究にも注力することによって、より深まるであろう。

摘要

研究背景:依恋理论的核心假设(普遍性、规范性、敏感性和能力)被认为是适用于全世界的。然而, 大多数关于依恋理论的研究都是在西方国家进行的, 这些核心假设在多大程度上得到了拉丁美洲研究的支持, 这一点从未得到系统的阐述。

研究目的:这篇系统的叙述性文献综述的目的是对当前在拉丁美洲国家进行的有关依恋理论的实证研究进行综合讨论。

研究方法:在四个电子数据库(Web of Science、PsycInfo、SciELO 和 Redalyc)中进行了检索, 82篇关于依恋或敏感性的出版物符合纳入标准。

研究结果:所有研究都没有报告依恋关系缺失的案例, 并且我们发现安全型依恋模式占主导地位, 研究主要针对非风险样本。在非风险样本中, 敏感性水平通常被认为是合格的, 并且与依恋质量有关。依恋安全性和看护者的敏感性与儿童发展结果呈正相关。基于依恋的干预研究大多显示了有效性。

研究结论:拉丁美洲的研究支持了依恋理论的关键理论假设, 并且研究主要是在城市中产阶级非风险样本中开展。然而, 通过加大对拉丁美洲基于当地概念和理论的护理研究, 将会丰富与依恋相关的研究领域。

ملخص

دراسات التعلق بأمريكا اللاتينية: مراجعة سردية

الخلفية: من المفترض أن تكون الفرضيات الأساسية لنظرية التعلق (العالمية ، المعيارية ، الحساسية ، والكفاءة) قابلة للتطبيق في جميع أنحاء العالم. ومع ذلك ، فقد أجريت غالبية الدراسات حول نظرية التعلق في الدول الغربية ، ولم يتم تناول مدى دعم هذه الفرضيات الأساسية من خلال الأبحاث التي أجريت في أمريكا اللاتينية بشكل منهجي. الهدف: الغرض من هذه المراجعة المنهجية السردية هو تقديم مناقشة متكاملة للمجموعة الحالية من الدراسات التجريبية المتعلقة بنظرية التعلق التي أجريت في بلدان أمريكا اللاتينية. الطريقة: تم إجراء بحث في أربع قواعد بيانات إلكترونية (Web of Science و PsycInfo و SciELO و Redalyc) وقد استوفى 82 منشورًا حول التعلق و / أو الحساسية معايير التضمين. النتائج: لم تذكر أي من الدراسات حالات غابت فيها علاقة التعلق ، وكانت أنماط التعلق الآمن هي السائدة ، بشكل أساسي للعينات الغير معرضة للمخاطرة. اعتُبرت مستويات الحساسية بشكل عام كافية في العينات غير المعرضة للمخاطرة ، ومرتبطة بجودة التعلق. وارتبط أمان التعلق وحساسية مقدمي الرعاية بشكل إيجابي بنتائج الطفل. أظهرت دراسات التدخل القائمة على التعلق فعالية في الغالب. الاستنتاجات: يدعم البحث في أمريكا اللاتينية الافتراضات النظرية الرئيسية لنظرية التعلق ، ولا سيما في عينات الطبقة المتوسطة الحضرية غير المعرضة للخطر. ومع ذلك ، يمكن إثراء مجال البحث المرتبط بالتعلق من خلال الاستثمار في المزيد من الدراسات في أمريكا اللاتينية حول تقديم الرعاية القائمة على المفاهيم والنظريات المحلية.

1. INTRODUCTION

More than 600 million people (nearly 9% of world population) live in the 20 countries that make up Latin America. Yet the Latin American literature on parenting and child development is often not considered in the international scientific discourse about attachment, even though it has seen substantial growth in the past decades. This way, in order to better understand attachment theory, which claims to reflect universal processes, it is necessary to determine whether its core hypotheses, in terms of the predominance of secure attachment (van IJzendoorn, 1990), sensitive parenting as a predictor of secure attachment (Ainsworth et al., 1974; Bakermans‐Kranenburg et al., 2003; De Wolff & van IJzendoorn, 1997), and positive child outcomes of attachment (Thompson, 2016), are also confirmed in these populations. Although these hypotheses are thought to be universally applicable, most attachment research comes from Western, Anglo‐Saxon countries, (Mesman, van IJzendoorn, & Sagi‐Schwartz, 2016); and the debate on the universality versus culture‐specificity of caregiver sensitivity is far from over (Keller et al., 2018; Mesman, 2018; Mesman et al., 2018). In this narrative literature review, we present and discuss empirical studies on attachment and/or sensitivity in Latin American countries to provide a comprehensive overview and integration of the available evidence for the core hypotheses of attachment theory in this region.

Humans establish attachment relationships throughout their lives, and the earliest attachment relationship is the emotional bond between infants and their main caregivers that is thought to reflect a universal human mechanism based on ethological and evolutionary considerations (Bowlby, 1969/1982, 1979). Attachment is considered “secure” if there is a balance between attachment behaviors (seeking proximity and comfort when distressed) and exploration behaviors (engaging with the environment when it is safe) (Ainsworth, 1989; Bowlby, 1969/1982). A core parenting variable in attachment theory is sensitive responsiveness, which refers to the ability of the caregiver to notice and interpret children´s signals accurately and to respond to those signals promptly and appropriately, which is defined as fitting the nature of the child´s communications (Ainsworth et al., 1978). The proposed universality of the main attachment mechanisms has been captured in four core hypotheses (van IJzendoorn, 1990): (1) The universality hypothesis assumes that given the opportunities, and in absence of neurodevelopmental issues, all children will become attached to a caregiver; (2) the normativity hypothesis states that in a non‐life‐threatening context, most children will be securely attached to their caregiver; (3) the sensitivity hypothesis refers to the assumption that children will be securely attached depending on the caregiving features, in which sensitivity is central; and (4) the competence hypothesis assumes that infants with a secure attachment will develop higher levels of social‐cognitive competence than children with an insecure attachment relationship. Further, relevant additions to the original formulations of the third and fourth hypotheses include the assumption that sensitivity is universal (although not uniform) (Mesman et al., 2018), and is related to positive child outcomes (Feeney & Woodhouse, 2016). Moreover, attachment theory research has led to the development of many intervention programs (Berlin et al., 2016), with many focusing on improving caregivers’ sensitivity as a means of fostering positive child development in different domains of functioning (Bakermans‐Kranenburg et al., 2003).

KEY FINDINGS

A total of 82 publications, between 1988 and 2020, representing 8 Latin American countries were identified, mostly on urban middle‐class non‐risk samples of mother‐child dyads.

Core theoretical assumptions (universality, normativity, sensitivity, and competence) were supported; and attachment‐based interventions proved some level of efficacy.

Despite an increase in Latin American attachment studies in the last decades, the continent is still underrepresented in the international scientific discourse on attachment which would benefit from including truly local insights in caregiving practices.

RELEVANCE TO THE FIELD OF MENTAL HEALTH

The relevance of attachment theory concepts to infant and child mental health development is undeniable, as evidenced by over 750 papers published in Infant Mental Health Journal since the year 2000. However, despite the theory's universality claims, systematic investigations of evidence for its hypotheses outside of the Western world are scarce. This paper provides a comprehensive summary of attachment research in Latin American countries to contribute to inclusive perspectives on attachment theory.

DIVERSITY AND ANTI‐RACIST STATEMENT

This literature review in itself represents an effort to mark the relevance of studying the empirical evidence base for a key developmental theory in a region usually ignored in mainstream research. Highlighting research from the Global South not necessarily written in hegemonic English promotes equity and inclusiveness in this particular scientific field. Further, any theory that supposes universality can only be taken seriously by paying attention to populations and studies from all possible corners of the globe to address potential normative biases. All of the authors identify as people of color, and three of them as ethnically Latin American (from Peru, Brazil, and Chile). All authors of the paper are involved in research on marginalized populations, addressing Eurocentric normativity and exclusion in mainstream theories and scientific practices.

Even though there is growing evidence that attachment theory's core principles are applicable outside of the Western world, the overwhelming majority of studies on attachment and sensitivity have been conducted in western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD; Henrich et al., 2010) societies (Mesman, van IJzendoorn, & Sagi‐Schwartz, 2016). This is one of the circumstances that prompted the cultural debate on attachment theory, along with the fact that parenting is known to be influenced by urban versus rural residence (Keller et al., 2006). Based on this and other relevant differences between Western and non‐Western countries, the cultural debate has raised criticism and questioned the universality of the attachment theory assumptions construct (Keller, 2013, 2021; LeVine, 2004; Weisner, 2015). Authors from the culture‐specificity perspective questioned the effect of culture on the applicability of the attachment theory´s core hypotheses and argued that definitions of those hypotheses and attachment‐related constructs are biased, focusing on individualistic cultural contexts (Keller, 2013; Rothbaum et al., 2000; Quinn & Mageo, 2013), not considering cultural‐specific parenting patterns (Dawson, 2018, Kärtner et al., 2010). For instance, they criticize the assumption that the infant is the central agent of the interaction, that infants are assumed to take the lead, and that dyadic interactions are expected to be turn‐taking and well‐rounded. Finally, they also question the focus on dyadic exchanges rather than (simultaneous) interactions with multiple caregivers that are common in many cultures (Keller et al., 2018).

Regarding the study of the attachment hypotheses in non‐Western countries, a cross‐cultural review including the case of Asia reported a total of 18 studies from six countries (Mesman, van IJzendoorn, & Sagi‐Schwartz, 2016). More recently, a review of research in Africa over the past 50 years identified only nine studies that assessed infant attachment in only five African countries (Voges et al., 2019). In both reviews, the fact that children were observed to be attached to a preferred caregiver, and a predominance of secure attachment patterns—similar to the Western findings—support the universality and normativity hypotheses. Only a handful of studies examined and (partly) supported the sensitivity and competence hypotheses outside of the West (Mesman, van IJzendoorn, & Sagi‐Schwartz, 2016).

Although research about attachment theory in Latin America has steadily evolved from a nascent to a fruitful field during the last two decades, it has not yet bridged the large gap separating Latin American research from the international discourse on attachment (Causadias et al., 2011). Challenges that may contribute to this gap include practical barriers to the use of attachment standardized research methods, the lack of facilities and financial resources for this type of research, the expenses of training (often only available in English) for key observational measures (Mesman, van IJzendoorn, & Sagi‐Schwartz, 2016), limited access to international peer‐reviewed publications on the state of the art of attachment research (Causadias & Posada, 2013), as well as the need to include large sample sizes that enable the use of parametric statistics. In addition, the work that is done in the region is often published only in Spanish or Portuguese and does not find its way to the international research community. It is not surprising, then, that attachment‐related studies in Latin America are scarce, and those that exist are overlooked. In the nonsystematic overview of relevant studies in non‐Western context by Mesman, van IJzendoorn, and Sagi‐Schwartz (2016), only seven studies from Latin America were included.

Despite these problems, clear progress has been made in the past decades. A group mainly of Latin American professionals and researchers established the Ibero‐American Attachment Network in 2009 (Red Iberoamericana de Apego, RIA) (Causadias et al., 2011), aimed at enhancing the interest, knowledge, and international collaboration in attachment research in the region. The network intends to provide training opportunities, hold a biennial Latin American attachment conference, and foster collaboration between teams from different countries. As a result, more than a decade after the foundation of RIA, the body of attachment literature in the area and the collaboration among local researchers has grown. However, many studies are still published in Spanish or Portuguese, and/or published in journals that are not indexed in the most current databases, so that they are easily segregated from the international literature. Therefore, the actual extent to which the attachment hypotheses are supported by research in Latin America has never been systematically addressed.

Given the specific cultural characteristics of Latin American countries, we cannot just assume that the principles of attachment theory apply here exactly as they do in Western countries. In the specific case of Latin American countries, familism—that refers to the support, loyalty and commitment offered to family members—is an important element of family cultural conceptions (Coohey, 2001), and Latin American parents and caregivers tend to present higher levels of emotional support and protectiveness than those in other cultures (Domenech et al., 2009; Harwood et al., 2002). Regarding parenting practices, a more controlling parental style characterized by respect and obedience is common (Dixon et al., 2008), but it is combined with traditional childrearing patterns characterized by physical affection and close family bonds (López et al., 2000). These particular manifestations of parental care do not seem conducive to sensitive responsiveness to children´s needs, or to child secure attachment and positive developmental outcomes. Overprotection or controlling strategies tend to be at odds with fostering secure base behaviors such as experiencing the mother as a safe haven (DeKlyen & Greenberg, 2016).

The aim of this systematic narrative literature review is to provide an integrative discussion of the current body of empirical studies concerning attachment theory in Latin American countries. Most of attachment research focuses on early childhood and the relationship between children and their caregivers, and observational measures commonly use a macro‐coding approach that refers to procedures in which caregivers´ behaviors are assessed based on a holistic observation of an entire interaction period, yielding a global score, in contrast to micro‐coding approach in which interactions are coded frame by frame (Mesman, 2010). For this reason, this narrative literature review will focus on children up to 6 years of age and their caregivers, and when using observational techniques will only include macro‐coding measures. The review is organized according to three themes: (1) the publication characteristics in terms of language, country, authors, publication year, and main caregiver considered; (2) the four core attachment hypotheses and the two stated additions, regarding the principles of (a) the universality of attachment, (b) the normativity of secure attachment, (c) caregiver sensitivity predicting secure attachment and additionally, the universality of caregiver sensitivity, and (d) secure attachment fostering social‐cognitive competence and other positive child outcomes, and—added for the purpose of this review—caregiver sensitivity fostering positive child outcomes across domains; and (3) the content and effectiveness of attachment‐based intervention studies in the Latin American context. We conclude by describing the main lessons from this review in terms of substantive insights, limitations of the current body of empirical research, and directions for future studies in the region. It has to be noted that this narrative literature review is theory‐driven, and focuses on the pre‐defined (Western) concepts and instruments from the field of attachment theory (etic approach), and does not include studies from other literatures of more locally developed caregiving concepts (emic approach) that may also provide valuable contributions to our understanding of the bond between caregivers and children. We will consider the potential added value of the latter in relation to our findings in the discussion section.

2. METHOD

2.1. Search strategy

The literature search focused on empirical studies about child attachment and parental sensitivity in Latin America published by August 22nd of 2018, using four electronic databases: Web of Science (WoS), PsycInfo, SciELO, and Redalyc. Prior to the database exploration, search terms that best represented the review aim were discussed and defined by the first and last authors.

The search keywords defined for WoS and PsycInfo were: TOPIC: (“maternal sensitiv*” OR “maternal responsive*” OR “paternal sensitiv*” OR “paternal responsive*” OR “mother* sensitiv*” OR “mother* responsive*” OR “father* sensitiv*” OR “father* responsive” OR “parent* sensitive*” OR “parent* responsive*” OR “sensitive parenting” OR attachment* OR “attachment representation*”) AND TOPIC: (infant* OR child* OR toddler OR baby OR babies OR preschooler) AND TOPIC: (“latin america*” OR latinoamerica* OR Argentin* OR Bolivia* OR Brasil* OR Brazil* OR Chile* OR Colombia* OR “Costa Rica*” OR “Costa Riq*” OR Cuba* OR Equador* OR Ecuador* OR “El Salvador*” OR Guatemal* OR Haiti* OR Hondur* OR Mexic* OR Nicaragu* OR Panam* OR Paragua* OR Peru* OR “República Dominicana” OR Dominican* OR Uruguay* OR Uruguai* OR Venezuela*OR “across the globe*” OR cultur*).

The search terms were adapted for the databases containing Spanish publications (SciELO and Redalyc) and defined as follows: “sensibilidad* materna* OR responsividad* materna* OR sensitividad* materna* OR sensibilidad* paterna* OR responsividad* paterna* OR sensitividad* paterna* OR sensibilidad* parental* OR responsividad* parental* OR sensitividad* parental* OR sensib* madre* OR sensib* padre* OR crianza sensi*OR apego* OR representaciones de apego AND Infan* OR niñ* OR hij* OR bebe* OR preescolar.” For all databases, the search terms were requested in the “Topic” field, matching on title, abstract, keywords and/or content of the publications. The range of time of publication was 1988–2018. Additionally, due to the production time of this review, a supplemental search was conducted on October 16th 2020. Disciplines unrelated to the field of this study (the broad behavioral and social sciences) were excluded.

2.2. Selection criteria

Studies had to meet all of the following inclusion criteria: (a) empirical article; (b) language of publication Spanish, Portuguese, or English; (c) when using observational techniques studies that include macro‐coding measures of attachment and/or sensitivity; (d) focus on human infants and children up to the age of 6 years; and (e) the focus children were born and living in Latin American countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Dominican Republic, Uruguay, and Venezuela).

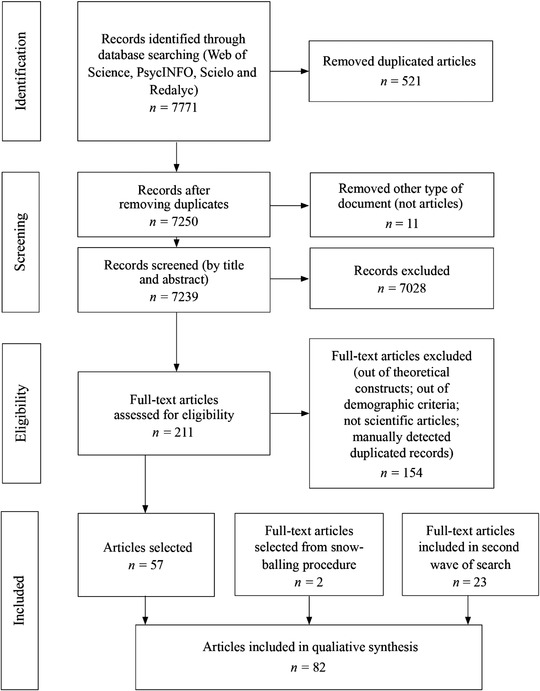

The selection of studies for this review is summarized in Figure 1, following the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses (Moher et al., 2009), and shows the results of the main search conducted in 2018, and the supplemental search conducted in 2020. These searches combined yielded 82 publications, between 1988 and 2020, to be included in this narrative review. Two randomly selected publications in English and two in Spanish were used to pilot the coding process by the first and the second authors, and results were discussed with the last author. The remaining publications were randomly assigned to trained coders. Studies published in Spanish or Portuguese were only assigned to native speakers of the respective languages. For each publication, coders performed a full‐text reading to identify: main research question, research design, presence of intervention (yes/no), groups/conditions, country, age of children, special characteristics of the population, main variables, attachment theory hypotheses tested in the study, measures and instruments, use of observation (yes/no), main results, and other coder observations (if applicable).

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for the search strategy

3. RESULTS

3.1. Publication characteristics

Eighty‐two publications related to attachment theory hypotheses and/or interventions conducted in Latin America were identified. Approximately three‐quarters of them were published in the past 10 years, showing that the number of studies from this region has increased just recently. Two of these publications were written in Portuguese, 31 in Spanish, 42 in English, and the remaining seven in Spanish and English, which is a recent practice of some Latin American journals. More than a third of the publications (n = 32) have co‐authors from institutions from outside of Latin America, and almost all these publications were issued in English.

Eight out of twenty Latin American countries were represented in these publications: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru. The vast majority of publications (n = 68) presented results based on a sample from one country. Fourteen publications presented data on more than one country, but just three of these presented samples from more than one Latin American country. The remaining eleven were comparisons mainly with the United States or European countries. Chilean samples were by far the most frequently represented, being present in more than half of identified publications (n = 45), followed by publications from Colombia (n = 12), Peru (n = 9), Mexico (n = 8), and Brazil (n = 6). Argentina, Ecuador, and Cuba were represented only once or twice each. Figure 2 shows the frequency of samples represented by years and countries.

FIGURE 2.

Frequency of samples per country and year

Finally, in most of the publications (n = 62) mothers were included as the main caregiver in relation to whom child attachment and caregiver sensitivity was assessed. Additional professional caregivers were considered in twelve publications, while fathers and grandmothers were only considered in three and one publication, respectively. One small‐scale study included three same‐sex couples as the main caregivers in relation to whom variables were assessed. In 11 publications no specific caregiver was reported since attachment was assessed at a representational level.

3.2. Attachment theory core hypotheses

In this section, studies reporting results that relate to four core hypotheses of attachment theory and defined additions are revised. This includes studies that report statistics on (a) the presence and quality of child attachment—covering the universality and normativity hypotheses; (b) the level of caregiver sensitivity, and/or the association between sensitivity and attachment quality—covering sensitivity hypothesis; and (c) the association between attachment quality or caregiver sensitivity and child social‐cognitive competence or other child outcomes—covering the competence hypothesis. Five of the identified publications (Fresno & Spencer, 2011; Garcia Quiroga & Hamilton‐Giachritsis, 2017; Posada et al., 2013; Santelices et al., 2015; Woldarsky et al., 2019) did not report individual statistics results or it was not possible to confirm that samples were also considered in other publications, therefore, are not included in the descriptions below.

Groups and subgroups of participants were categorized as either non‐risk samples (NRS) or high‐risk samples (HRS), based on the assumptions in the publication in question. Samples were labeled as HRS when the publication mentioned that specific characteristics of this sample were likely to negatively affect child attachment and/or caregiver´s sensitivity. These characteristics could include child, caregiver, and/or family risk factors. In four studies data from rural groups were considered, and even though in some cases it was mentioned it was a possible risk, we chose to not stigmatize these groups by labeling them as HRS. Finally, we decided not to report specific socioeconomic status (SES) level of groups and subgroups, because this information was often lacking, and when present reported in many different ways that cannot be compared between studies.

3.2.1. Universality and normativity hypotheses

Forty‐eight publications that measured child attachment were found, of which 45 reported statistical results on the presence and/or quality of attachment, reflecting 39 unique samples (see Table 1 for details). Secure attachment was assessed with six different instruments, of which the Attachment Behavior Q‐Sort (AQS; Waters, 1995) and the Massie‐Campbell´s Attachment During Stress Scale (ADS; Massie & Campbell, 1992) are the only ones with psychometric studies in Latin American samples (Nóblega, Conde et al., 2019; Salinas‐Quiroz et al., 2014). Most of the publications using other instruments presented below did report relevant information about the measures they used for their specific samples; and described their training processes, along with information about the achieved intercoder reliability at training or when coding, that were adequate in all publications. However, in eight cases no appropriate information about reliability was reported.

TABLE 1.

Overview of publications reporting on child attachment quality and attachment correlates

| Publication | Country | Type of sample | n | Children's age (in months) | Predominantly secure | Attachment‐outcome relation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Strange Situation Procedure (SSP) | ||||||

| Valenzuela (1990) | Chile | NRS and HRS | 85 | 17 to 21 |

NRS: Yes HRS: No |

Yes |

| Lecannelier et al. (2008) | Chile | NRS | 130 | 11 to 19 | Yes | NA |

| Mesa et al. (2009) | Colombia | HRS | 4 | 12 to 18 | No | NA |

| Santelices et al. (2010)a | Chile | NRS | 72 | M = 12 | Yes | NA |

| Quezada and Santelices (2010) | Chile | NRS | 72 | 11 to 15 | Yes | NA |

| Gojman et al. (2012) | Mexico | NRS, urban (U) and rural (R) | 66 | 10 to 26 |

U: Yes R: No |

NA |

| Saur et al. (2018) | Brazil | NRS | 50 | 12 to 25 | Yes | Yes |

| Lecannelier et al. (2019) | Chile | NRS, study 1 (S1) and study 2 (S2) | 233 |

S1: M = 13.30 S2: M = 18.00 |

S1: Yes S2: Yes |

NA |

| Fuertes et al. (2020) | Brazil | NRS | 26 | M = 12 | Yes | NA |

| The Attachment Behavior Q‐Sort (AQS) | ||||||

| Posada et al. (1995) | Colombia | NRS | 31 | 30 to 55 | No | NA |

| Posada et al. (1999) | Colombia | NRS and HRS | 84 |

NRS = 8 to 19 HRS = 12 to 60 |

NRS: Yes HRS: No |

NA |

| Posada et al. (2002) | Colombia | NRS | 61 | 8 to 19 | Yes | NA |

| Carrillo et al. (2004) | Colombia | NRS, with mother (M) and grandmother (GM) | 30 | 18 to 42 |

M: Yes GM: Yes |

NA |

| Posada et al. (2004) | Colombia | NRS | 30 | 6 to 13 | Yes | NA |

| Ortiz et al. (2006) | Colombia | NRS and HRS | 40 | 10 to 30 |

NRS: No HRS: No |

NA |

| Wachs et al. (2011)b | Peru | NRS, at 12 (T1) and 18 (T2) months | 177 | 12 and 18 |

T1: Yes T2: Yes |

Yes |

| Carbonell et al. (2015) | Colombia | HRS | 10 | 30 to 66 | NA | No |

| Salinas‐Quiroz (2015) | Mexico | NRS | 34 | 20 to 36 | No | Yes |

| Nóblega et al. (2016) | Peru | NRS | 32 | 8 to 10 | No | NA |

| Posada et al. (2016) |

Colombia (C) Peru (P) |

NRS | 115 |

C = 39 to 48 P = 45 to 72 |

C: Yes P: No |

NA |

| Díaz et al. (2018) | Ecuador | NRS | 16 | 36 to 71 | Yes | NA |

| Salinas‐Quiroz et al. (2018) | Mexico | NRS | 8 | M = 27.3 | NRS: Yes | NA |

| Bortolini and Piccinini (2018) | Brazil | NRS and HRS | 48 | M = 28.1 |

NRS: Yes HRS: No |

NA |

| Nóblega, Bárrig & Fourment (2019) | Peru | NRS | 56 | 30 to 72 | No | NA |

| The Attachment Story Completion Task (ASCT) | ||||||

| Riquelme et al. (2003) | Chile | NRS | 60 | 36 to 72 | Yes | Yes |

| Pierrehumbert et al. (2009) | Chile | NRS, girls (G) and boys (B) | 45 | M = 54 |

G: Yes B: No |

NA |

| Pérez et al. (2013) | Chile | NRS | 137 | 37 to 49 | Yes | NA |

| Fresno et al. (2014) | Chile | NRS and HRS | 66 | M = 70.8 |

NRS: Yes HRS: No |

NA |

| Villachan‐Lyra et al. (2015) | Brazil | NRS | 40 | 36 to 48 | NA | Yes |

| García Quiroga et al. (2017) | Chile | NRS and HRS | 77 |

NRS: M = 53.63 HRS: M = 63.78 HRS: M = 64.71 |

NRS: Yes HRS: No HRS: No |

NA |

| Pérez et al. (2017) | Chile | NRS | 46 | M = 54.26 | No | NA |

| Fresno et al. (2018) | Chile | NRS and HRS | 96 | M = 72 |

NRS: Yes HRS: No |

NA |

| Nóblega, Bárrig‐Jó et al. (2019) |

Mexico (M) Peru (P) |

NRS | 94 |

M = 36 to 78 P = 41 to 72 |

M: Yes P: Yes |

Yes |

| Massie‐Campbell`s Attachment During Stress Scale (ADS) | ||||||

| Lecannelier et al. (2009)a | Chile | NRS | 17 | M = 44 | Yes | NA |

| Figueroa et al. (2012)a | Chile | NRS | 9 | 5 to 12 | No | NA |

| Lecannelier et al. (2014)a | Chile | HRS | 62 | 2 to 12 | No | Yes |

| Cárcamo et al. (2016) | Chile | NRS, at Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2) | 110 |

T1: M = 6.4 T2: M = 14.85 |

T1: Yes T2: Yes |

NA |

| Farkas et al. (2017) | Chile | NRS, urban/non‐Mapuche (NM) and rural/Mapuche (M) | 34 | M = 11.74 |

NM: Yes M: No |

NA |

| Cárcamo et al. (2019) | Chile | NRS | 25 | 10 to 14 | Yes | NA |

| Lecannelier et al. (2019) | Chile | NRS and HRS | 253 |

NRS: M = 17.21 HRS: M = 12.50 HRS: M = 7.51 |

NRS: Yes HRS: No HRS: No |

NA |

| Parenting‐Child Reunion Inventory (PCRI) | ||||||

| Sotgiu et al. (2011) | Cuba | NRS and HRS | 22 | 48 to 132 |

NRS: Yes HRS: Yes |

NA |

| Family Drawing Test | ||||||

| Lara et al. (1994) | Mexico | NRS, working (W) and non‐working (NW) mothers | 211 | 60 to 83 |

W: No NW: No |

Yes |

Note: n = number of participants being considered in reported results from publication; NRS = Non‐risk sample; HRS = High‐risk sample. For AQS, samples with similar or higher scores as/than the mean security score from the met‐analysis (.35; Cadman et al., 2017) were classified as predominantly secure.

aAttachment‐based intervention publication: only control group or pre‐intervention results are reported.

bOnly 30 items from AQS were used to describe attachment behavior.

In relation to the universality hypothesis, it should be noted that none of the studies that assessed child attachment reported cases in which it was not possible to evaluate an attachment relationship. Additionally, Table 1 shows that the AQS, considered as a gold standard of attachment assessment, was the most used measure in this review with 14 publications, reporting on 19 unique samples. Average secure base behavior scores in all samples were positive, ranging from .19 (SD = .30) to .58 (SD = .19). Comparing sample averages with the mean security score of .35 (95% CI [.34,.37]) reported in the most recent meta‐analysis (average of 186 samples; Cadman et al., 2017), reveals a mix of Latin American samples scoring similarly (k = 3), scoring higher (k = 7), and scoring lower (k = 9). Samples with similar or higher scores as/than the mean security score from the meta‐analysis were classified as predominately secure.

According to attachment theory, normativity hypothesis can only be expected to be met among populations without conditions that would hamper the formation of a secure attachment relationship, therefore, results based on HRS should be cautiously used when testing this hypothesis. The AQS average scores, as describing the level of similarity with a securely attached child, provide some indirect information that also gives some support for this hypothesis. Additionally, the remaining five instruments reported on the quality of attachment. Table 1 shows that the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP; Ainsworth et al., 1978)—considered to be the gold standard of assessing attachment quality—was only used in nine publications with 12 unique samples, consisting mostly of NRS of typically developing children (TDC) from Chile. In one sample, almost 50%, and in eight samples, more than 50% of children were classified as securely attached, which is in line with the normative (modal) tendency reported cross‐culturally (Solomon & George, 2016). Lower percentages of security were reported in publications on high‐risk and rural samples. This pattern reflects mixed support for the normativity hypothesis, with the majority of (but not all) studies in NRS showing predominant secure attachment. The lower rate of security in at‐risk samples is consistent with attachment theory which assumes lower security in challenging circumstances.

The Attachment Story Completion Task (ASCT; Bretherton et al., 1990) assesses children attachment representations through narratives to identify secure base scripts. Eight publications, reporting on 14 unique samples, mainly from Chile, included children from 3 to 6 years old. For eight samples, a predominance of secure attachment was reported, with more than 50% of children classified as secure or children obtaining scores reflecting secure attachment according to their specific coding system. The remaining four out of six samples with predominant insecure attachment were reported for high‐risk groups. The ADS is a widely used instrument in Chilean public health care, and we found seven publications using the ADS reporting on 10 unique samples, five of which showed a predominance of secure attachment, with more than 50% of children classified as secure or with scores that indicated the predominance of secure behaviors. Three out of the remaining five samples with predominant insecurity were HRS and one was a rural/Mapuche sample. The Parent–Child Reunion Inventory (PCRI self‐report; Marcus, 1988) and the Family Drawing Test (FDT; based on child drawings) were each used in one publication with two samples. Attachment security was the predominant pattern for the samples on the PCRI publication, but not for the samples on the FDT publication.

3.2.2. Sensitivity hypotheses and quality of caregiving

Fifty‐three publications that measured caregiver sensitive behavior were found, of which 48 reported statistical results on the quality of sensitivity and/or the association between caregiver sensitivity and child attachment quality, reflecting 44 unique samples (see Table 2 for details).

TABLE 2.

Overview of publications reporting on caregiver´s sensitive quality and sensitivity correlates

| Publication | Country | Type of sample | n | Children's age (in months) | Predominantly sensitive | Sensitivity hypothesis confirmed | Sensitivity‐outcome relation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ainsworth's Maternal Sensitivity vs. Insensitivity scale | |||||||

| Valenzuela (1997) | Chile | NRS and HRS | 85 | 17 to 21 |

NRS: Yes HRS: No |

Yes | Yes |

| Gojman et al. (2012) | Mexico | NRS, urban secure (US), urban insecure group (UI) and rural secure (RS), rural insecure group (RI) | 66 | 9 to 26 |

US: Yes UI: No RS: Yes RI: No |

Yes | NA |

| Fourment et al. (2021) | Peru | NRS | 12 | 4 to 21 | Yes | NA | NA |

| Ribeiro et al. (2021) | Brazil | NRS | 22 | M = 2 | Yes | NA | NA |

| Experimental Index of Child‐Adult Relationships (CARE‐Index) | |||||||

| Santelices et al. (2009) | Chile | NRS, primary caregiver (PC) and care centre staff (CCS) | 185 | 8 to 24 |

PC: Yes CCS: Yes |

NA | Yes |

| Tenorio De Aguiar et al. (2009) | Chile | NRS | 40 | 3 to 9 | Yes | NA | Yes |

| Olhaberry (2011) | Chile | NRS, day care (DC) and without day care (WDC) | 80 | 4 to 15 |

DC: Yes WDC: Yes |

NA | Yes |

| Olhaberry (2012) | Chile | NRS, girls (G) and boys (B) | 80 | 4 to 15 |

G: Yes B: Yes |

NA | Yes |

| Olhaberry and Santelices (2013) | Chile | NRS, single mother (SF) and nuclear families (NF) | 80 | 4 to 17 |

SF: Yes NF: Yes |

NA | Yes |

| Santelices and Pérez (2013) | Chile | NRS, at Time 1 (T1), Time 2 (T2), and Time 3 (T3) | 43 | 8 to 24 |

T1: Yes T2: Yes T3: Yes |

NA | NA |

| Santelices (2014) | Chile | NRS | 69 | 12 to 24 | Yes | NA | NA |

| Olhaberry, Escobar, Mena et al. (2015) a | Chile | HRS | 134 | 2 to 3 | No | NA | NA |

| Olhaberry, Escobar, Morales et al. (2015) | Chile | HRS | 10 | 4 to 16.2 | No | NA | Yes |

| Olhaberry, León et al. (2015) a | Chile | HRS | 61 | 8.4 to 18.8 | No | NA | NA |

| Farkas et al. (2017) | Chile | NRS, urban/non‐Mapuche (NM) and rural/Mapuche (M) | 34 | M = 11.74 |

NM: Yes M: Yes |

NA | NA |

| Santelices et al. (2017) a | Chile | NRS, control (CG) and experimental group (EG) | 53 | 0 to 24 |

CG: Yes EG: Yes |

NA | NA |

| Binda et al. (2019) | Chile | HRS | 177 | 2 to 12 | Yes | NA | NA |

| Fuertes et al. (2020) | Brazil | NRS, clustered as secure (S) and insecure (I) | 26 | M = 9 |

S: Yes I: Yes |

No | NA |

| Maternal Behavior Q‐Set (MBQS) and Maternal Behavior for Preschoolers Q‐Set (MBPQS) | |||||||

| Posada et al. (1999) | Colombia | NRS and HRS | 84 |

NRS = 8 to 19 HRS = 12 to 60 |

NRS: Yes HRS: No |

Yes | NA |

| Posada et al. (2002) | Colombia | NRS | 61 | 8 to 19 |

Yes |

Yes | NA |

| Posada et al. (2004) | Colombia | NRS | 30 | 6 to 13 | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Ortiz et al. (2006) | Colombia | NRS and HRS | 40 | 10 to 30 |

NRS: No HRS: Yes |

Yes | NA |

| Carbonell et al. (2010) | Colombia | NRS and HRS | 93 | 3 to 7 |

NRS: Yes HRS: Yes |

NA | |

| Carbonell et al. (2015) | Colombia | HRS | 10 | 30 to 66 | NA |

No |

Yes |

| Salinas‐Quiroz (2015) | Mexico | NRS | 34 | 20 to 60 |

Yes |

No |

No |

| Nóblega et al. (2016) | Peru | NRS | 32 | 8 to 10 |

Yes |

Yes | NA |

| Posada et al. (2016) |

Colombia (C) Peru (P) |

NRS | 115 |

C = 39 to 48 P = 45 to 72 |

C: Yes P: No |

Yes | NA |

| Díaz et al. (2018) | Ecuador | NRS | 16 | 36 to 71 |

No |

Yes | NA |

| Salinas‐Quiroz et al. (2018) | Mexico | NRS | 8 | M = 27.3 | Yes | NA | NA |

| Márquez et al. (2019) | Mexico | NRS and HRS | 40 |

NRS = 61.2 HRS = 60 |

NRS: Yes HRS: Yes |

NA | NA |

| Nóblega, Bárrig & Fourment (2019) | Peru | NRS | 56 | 30 to 72 | No | Yes | NA |

| Barone et al. (2021) a | Colombia | NRS, control (CG) and experimental group (EG) | 25 | 16 to 36 |

CG: Yes EG: Yes |

NA | NA |

| Adult Sensitivity Scale (E.S.A.) | |||||||

| Farkas et al. (2015) | Chile | NRS, mothers (MO) and educators (ED) | 226 | 10 to 15 |

MO: Yes ED: Yes |

NA | NA |

| Farkas and Rodríguez (2017) | Chile | NRS | 90 | 10 to 15 | Yes | NA | No |

| Gálvez and Farkas (2017) | Chile | NRS | 105 | 10 to 14 | Yes | NA | Yes |

| Kast et al. (2017) | Chile | NRS | 19 | 10 to 15 | Yes | NA | |

| Cuellar and Farkas (2018) | Chile | NRS | 78 | 10 to 15 | Yes | NA | No |

| Muñoz and Farkas (2018) | Chile | NRS | 12 | 12 to 14 | NA | NA | Yes |

| Farkas et al. (2020) | Chile | NRS, at Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2) | 90 |

T1: M = 12.0 T2: M = 29.31 |

T1: Yes T2: Yes |

NA | NA |

| Ramos et al. (2020) | Chile | NRS | 91 | 10 to 15 | Yes | NA | Yes |

| Emotional Availability Scales: Infancy to Early Childhood Version (EAS) | |||||||

| Bornstein et al. (2008) | Argentina | NRS | 70 | M = 20.22 | Yes | NA | NA |

| Fonseca et al. (2010) | Brazil | NRS and HRS | 131 | M = 4.00 |

NRS: Yes HRS: Yes |

NA | NA |

| Bornstein et al. (2012) | Argentina | NRS | 70 | M = 5.27 | Yes | NA | NA |

| Gil‐Rodríguez et al. (2018) | Mexico | NRS | 60 | M = 51.96 | No | NA | Yes |

| The Attachment During Stress Scale (ADS) | |||||||

| Cárcamo et al. (2016) | Chile | NRS, at Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2) | 110 |

T1: M = 6.4 T2: M = 14.85 |

T1: Yes T2: Yes |

Yes | NA |

Note: n = number of participants being considered in reported results from publication; NRS = Non‐risk sample; HRS = High‐risk sample.

Attachment‐based intervention publication: only control group or pre‐intervention results are reported.

Sensitivity was assessed with seven different instruments, of which the Adult Sensitivity Scale (E.S.A; Santelices et al., 2012) is the only one that has been developed in Latin America, and has been shown to have adequate validity and reliability for its use in different contexts in Chile (Santelices et al., 2012). Additionally, the maternal Q‐sorts are the only ones with psychometric studies in Latin American samples (Bárrig‐Jó et al., 2020; Díaz & Nóblega 2020; Salinas‐Quiroz et al., 2014). Almost all of the publications using other instruments presented here did report information about the measures they used for their specific samples, and described their training processes, along with information about the achieved intercoder reliability at training or when coding, which was adequate in all cases. In two cases no information about reliability for the Maternal Behavior Q‐Set (MBQS; Pederson & Moran, 1995) and the Emotional Availability Scales: Infancy to Early Childhood Version (EA Scales; 3rd ed.; Biringen et al., 1998) was reported.

Table 2 shows that Ainsworth's Maternal Sensitivity versus Insensitivity to Infant Signals and Communications observational scale (Ainsworth et al., 1974)—considered as the gold standard of sensitive caregiver behavior assessment—was only used in four publications with eight unique samples. Five of eight samples had average sensitivity scores considered as sensitive, that is, scores 5 or higher. Lower average sensitivity levels were reported for a high‐risk sample and mothers with insecure attachment representations. The Experimental Index of Child‐Adult Relationships (CARE‐Index, Crittenden, 2006) was the most used measure in this review with 14 publications, reporting on 21 unique samples. Considering average scores rounded up to one digit, 18 samples were in the “adequate” category (scores from 7 to 10 out of 14) and the remaining three in the “risk/inept” category (scores from 0 to 6). Lower average scores of sensitive behaviors were reported in publications on HRS. The other most used instrument was the MBQS and Maternal Behavior for Preschoolers Q‐Set (MBPQS; Posada et al., 2007) also with 14 publications, reporting on 19 unique samples, mainly with NRS of TDC. Average caregivers´ sensitive behavior scores were positive in all subsamples, ranging from .20 (SD = .44) to .74 (SD = .25). More than two‐thirds of these samples (k = 14) reached average scores close to .50 or higher. Only one out of the remaining five samples with lower average scores can be considered an at‐risk sample.

The E.S.A was the only measure developed in Latin America, with eight publications, reporting on eight unique samples, all of them NRS of TDC from Chile. In all eight samples average caregiver´s sensitive behavior scores were in the “adequate” category, with the majority of caregivers classified as “adequate” too. The EA Scales and the Massie‐Campbell´s Attachment During Stress Scale (ADS; Massie & Campbell, 1992) were used four times and once, respectively, and sensitive behavior was the predominant pattern among five out of the six samples they reported.

The sensitivity hypothesis, that is, the relation between caregiver´s sensitive behavior and child secure attachment, was tested in fourteen publications, and was confirmed in 11 of those publications (see penultimate column of Table 2), most of which were NRS.

3.2.3. Competence hypotheses and sensitivity correlates

The final column of Table 1 shows that the competence hypothesis and its extension to other child outcomes were tested in only a few Latin American publications, but when studied, most of the evidence supports it. Nine out of ten relevant publications indicated that secure attachment was related to social‐cognitive competence and more positive functioning in children across different domains. Attachment security was associated with a higher socio‐cognitive development and higher social competence; and more competent behavior in terms of social orientation, object orientation, and reactivity. Additionally, attachment security was found to be related with a higher cognitive and language development level; a stronger theory of mind; and a better nutritional status. Only one study found no relation between attachment security and child development such as gross and fine motor, hearing and language, and personal and social competence.

Although caregiver´s sensitive responsiveness is not generally represented in descriptions of the competence hypothesis, it is interesting to see if sensitivity—as a key attachment process variable—also relates to positive outcomes in the Latin American context as it does in Western samples. The final column of Table 2 shows that 15 publications reported testing associations between sensitivity and child developmental outcomes, 12 of which turned out to be significant. Sensitive behavior was associated with a better nutritional status, a higher level of cooperativeness (and lower level of passivity), a better development of gross and fine motor skills, hearing and language, and personal and social skills, a better socio‐emotional developmental level, a higher dyadic level of commitment, and lower emotional and behavioral problems. Three publications found no significant relations between sensitivity and child socio‐cognitive or socio‐emotional development, nor with child language ability.

3.3. Effectiveness of attachment‐based interventions

Nine publications aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of attachment‐based interventions (see Table 3 for details). Almost all of them were conducted in Chile, and only the one conducted in Colombia used an internationally known program, the Video‐feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting and Sensitive Discipline (VIPP‐SD; Juffer et al., 2008). Local programs used in Chile differed in each study, and only two of them had specific names: Play with Our Children (POC; Brahm et al., 2016) and Promoting secure attachment (Santelices et al., 2010). Studies were experimental or quasi‐experimental, and seven out of the nine studies worked with a control group to compare the results of the intervention programs.

TABLE 3.

Overview of publications reporting on attachment‐based interventions

| Lecannelier et al. (2009) | |

|---|---|

| Country | Chile |

| Sample | N = 55 typically developing children (age 2–4 months) |

| Intervention program | Two intervention groups: (1) Attachment workshop group: six one‐and‐a‐half‐hour group session intervention with the objective of providing tools and knowledge to promote secure attachment through the enhancement of maternal sensitivity and mentalization skills; (2) Massage workshop group: one one‐and‐a‐half‐hour and seven twenty‐minutes group session training on infant massage combined with maternal sensitivity |

| Study design | Randomized control trial with Pre‐ to Posttest |

| Measures | Massie‐Campbell´s Attachment During Stress Scale for infant attachment, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale for maternal depressive symptomatology |

| Main results | Considering both attachment workshop and massage workshop as one group, secure attachment rate significantly increased from pre‐ to posttest. The rate of depressive symptomatology only significantly decreased from pre‐ to posttest in the attachment workshop group |

| Santelices et al. (2010) | |

|---|---|

| Country | Chile |

| Sample | N = 72 typically developing children (mean age 12 months) |

| Intervention program | Promoting secure attachment intervention with ten (pre‐ and post‐natal) group sessions aimed at promoting maternal sensitivity, to modify mother´s mental representations, and to promote the development of a secure bond between the dyad. Techniques included group discussions, educational videos, and didactical exercises were used to approach topics like attachment, pregnancy, maternal representations, and discussing fantasies related to the baby |

| Study design | Randomized control trial with Posttest only |

| Measures | Strange Situation Procedure for infant attachment |

| Main results | The proportion of secure attached children increased from pre‐ to posttest in the intervention groups, but not significantly more than in the control group (n.s.) |

| Figueroa et al. (2012) | |

|---|---|

| Country | Chile |

| Sample | N = 9 children (average age 7 months) with early indicators of insecure attachment to mothers |

| Intervention program | Four weekly two‐hours group sessions with the educational objectives of clarifying the "attachment" concept, some parenting guidelines, and tools to address stressful situations. Skills associated with parental sensitivity, child rearing, and child development were discussed |

| Study design | Pre‐to Posttest, No control group |

| Measures | Massie‐Campbell´s Attachment During Stress Scale for infant attachment, Qualitative interviews for adult's evaluation |

| Main results | Quantitatively, the number of securely attached children increased from four pre‐intervention to seven post‐intervention (n.s.). Qualitatively, participants were satisfied with the intervention, highlighted that it helped them to connect better with their other children, and that during the workshops they were able to share their experiences, emotions, and fears with other caregivers |

| Lecannelier et al. (2014) | |

|---|---|

| Country | Chile |

| Sample | N = 41 institutionalized children (age 2–12 months) and their caregivers |

| Intervention program | One‐day face‐to‐face training followed but permanent supervision with the Attachment sensitivity manual aimed at developing and promote of skills, knowledge, and attitudes adequate to understand, manage, and assess the infant's competencies and development. The manual is divided in two: (1) Basic aspects: the minimum competencies for interacting with the infants and include the promotion of physical contact, visual contact, and vocalization; and (2) Specific aspects: a more complex type of activity related to the promotion of interactive play, the detection and regulation of temperament, and the detection and regulation of attachment styles |

| Study design | Pre‐to Posttest, No control group |

| Measures | Massie‐Campbell´s Attachment During Stress Scale for infant attachment |

| Main results |

No effects of the intervention on attachment security was found |

| Olhaberry, Escobar, Mena et al. (2015) | |

|---|---|

| Country | Chile |

| Sample | N = 134 typically developing children (age 2–3 months) and their mothers with history of depression |

| Intervention program | Five 1.5‐hr group sessions aimed at reducing maternal depression and promote a positive mother‐infant bond from pregnancy to the child's first year of life. Theoretically based on attachment theory and cognitive behavioral principals, topics related to how participants feel, how to identify and solve problems, how the pregnancy is being lived, the mother they had and the mother they want to be, and getting ready for the arrival of the baby we treated in each session |

| Study design | Pre‐to Posttest, with control group |

| Measures | Experimental Index of Child‐Adult Relationships for maternal sensitivity, Beck Depression Inventory for maternal depressive symptomatology |

| Main results | Intervention group showed significantly higher scores in maternal sensitivity compared to control group at posttest, and a significant reduction of depressive symptoms from pre‐ to posttest compared to control group |

| Olhaberry, León et al. (2015) | |

|---|---|

| Country | Chile |

| Sample | N = 61 typically developing children (age 8.4–18.8 months) and their mothers receiving treatment for depressive symptomatology |

| Intervention program | Four sixty‐minutes video‐feedback‐sessions that included speaking for the child, questions (related to observed, its relation with other interactions, about the child, and themselves), information about the child`s development period, identification of sensitive interaction chains, giving support to the mother, exploration of internal states that underlie behaviors, reflection, and creating new meanings |

| Study design | Pre‐to Posttest, with control group |

| Measures | Experimental Index of Child‐Adult Relationships for maternal sensitivity, Beck Depression Inventory for maternal depressive symptomatology |

| Main results | Intervention group showed significantly higher level of maternal sensitivity compared to control group from pre‐ to posttest. A descriptive reduction in maternal depressive symptoms was observed for both groups, difference was not statistically significant |

| Brahm et al. (2016) | |

|---|---|

| Country | Chile |

| Sample | N = 102 typically developing children (age 2–23 months) |

| Intervention program | Play with Our Children (POC; UC–Christus Health Network dependent on the Family Medicine Department of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile) with weekly group‐sessions, home visits, and interviews aimed at strengthening dyadic interaction, promote comprehensive development of children from 0 to 48 months old, enhance parenting skills, and strengthen networks among caregivers. Intervention is mainly based on attachment theory, a psychoanalytic approach, and community orientation. |

| Study design | Posttest only, with control group |

| Measures | Maternal Behavior Q‐set for maternal sensitivity, Patient Health Questionnaire for maternal depressive symptoms, Parenting stress index |

| Main results | At posttest, sensitivity was significantly higher in intervention mothers than control‐group mothers of children older than 12 months, but not in the group of children younger than 12 months. Parental stress was significantly lower in mothers of children younger than 12 months. A decrease in maternal depressive symptoms was observed for both age groups, but was not statistically significant |

| Santelices et al. (2017) | |

|---|---|

| Country | Chile |

| Sample | N = 53 typically developing children (age 0–24 months) and their nursery schools` caregivers (teachers and assistants) |

| Intervention program | Eight monthly four‐hour group workshop and field supervision program to promote sensitivity, based on the needs of the individuals involved. Workshops aimed at developing a more sensitive response and an improved reflective or mentalizing capacity in the relationships with children, and field supervision aimed at addressing the school caregiver's anxiety and supporting their work with their managers |

| Study design | Pre‐to Posttest, with control group |

| Measures | Experimental Index of Child‐Adult Relationships for caregiver sensitivity |

| Main results | Intervention group showed significantly higher sensitivity levels than the control group from pre‐ to posttest |

| Barone et al. (2021) | |

|---|---|

| Country | Colombia |

| Sample | N = 25 typically developing children (age 16–36 months) and their mothers, from a low socioeconomic status rural area |

| Intervention program | Video‐feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting and Sensitive Discipline (VIPP‐SD; Juffer et al., 2008) standardized protocol of six home visits, with defined themes, tips, and exercises for each visit, according to the specific maternal profile defined at baseline evaluation |

| Study design | Randomized control trial with Pre‐ to Posttest |

| Measures | Maternal Behavior Q‐Set for maternal sensitivity and Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices survey for food habits |

| Main results | VIPP‐SD enhanced sensitivity at post‐intervention and changes remained stable at 6‐month follow up. Intervention group showed significantly higher positive food habits than the control group, food habits improved from pre‐ to post‐intervention and from pre‐intervention to follow‐up, and VIPP‐SD enhanced food habits at post‐intervention and changes remained stable at 6‐month follow up |

Table 3 shows that three interventions were tested with TDC and their caregivers. In two of these cases, dyads were parents and children from low to middle‐low SES homes and some evidence on the effectiveness of their interventions was found, based on a significant increase in sensitivity or secure attachment in the intervention group either from pre‐ to posttest or compared to the control group, or both. In the case of the low‐risk or non‐risk dyads, results did not demonstrate any significant effectiveness. In contrast, a study with TDC and their nursery school´s caregivers, teachers and assistants, showed significant effectiveness of the intervention to improve caregivers` sensitivity in the intervention group compared to the control group from pre‐ to posttest. From the remaining five publications, which included dyads considered to be at risk or disadvantaged, only three showed evidence for the effectiveness of the interventions. This was the case for two Chilean samples of TDC children with their mothers with history of depression and receiving treatment for depressive symptomatology; and one Colombian sample of TDC from a low socioeconomic status rural area. In all three cases, effectiveness meant a significant increase in sensitivity in the intervention group compared to the control group from pre‐ to posttest. From these publications, it can be concluded that there is some evidence for the effectiveness of attachment‐based interventions in Latin American samples.

4. DISCUSSION

The present systematic narrative literature review gives information about the main characteristics of Latin American publications on attachment theory; additionally, it provides some support for each of the core hypotheses of attachment theory, however, some specificities need to be highlighted; and some evidence on the effectiveness of attachment‐based interventions in the Latin American contexts is also provided. Nevertheless, some important gaps and limitations in the available literature need to be addressed.

Looking at the characteristics of all the studies reviewed in terms of country, authors, publication language, sample characteristic, and caregivers considered, some interesting patterns emerge. For one, only a few Latin American countries produce the majority of publications (12 out of 20 countries not represented at all), with Chile being the country with the highest production on publications related to attachment theory by far, particularly regarding attachment‐based intervention publications that were almost exclusively from Chile. This is likely to be related to a recent public health policy shift in Chile focusing on promoting children´s social and emotional development (Cárcamo et al., 2014), which might draw more attention from scholars and grant higher societal relevance to attachment‐driven research. With considerably less production, but still second on the list is Colombia, that together with Chile is among the top five countries with the highest scientific production in Latin America in general (Ibánez, 2018). Interestingly, most of the researchers conducting attachment studies in Latin America received their graduate training in the United States and Europe (Causadias & Posada, 2013). In addition, a significant percentage of the English publications in the current review have co‐authors from institutions from United States and Europe. This is likely to indicate that Latin American researchers are collaborating to make use of the extensive expertise in this field in other regions of the world. However, a potential downside is that this could also reflect dependence on Western researchers. More generally, the mechanisms that favor Western theories and English publications as focal points in scholarship from the Global South could play a role here, given that it facilitates international visibility and recognition, but can also marginalize local perspectives (Collyer, 2016).

In terms of study characteristics, most samples consisted of NRS of TDC, and most included only the mother as the main caregiver. Non‐maternal caregivers were only represented in a few publications. The near absence of fathers is in line with the international literature, in which fathers are usually left out (Cabrera et al., 2018; Palm, 2014). Remarkably, one small‐scale study included same‐sex parents, which is clearly an innovative inclusion in the field. Further, it has to be noted that few psychometric studies of the key attachment‐related instruments have been conducted with Latin American groups, and study samples are usually small (in comparison to Western samples). The often‐limited resources available for academic research in most Latin American countries are likely to be responsible for these issues.

Furthermore, the results of the present study reveal some support for the universality and normativity hypotheses. Regarding universality hypothesis, from the AQS publications and the fact that scores tend to be positive it is possible to presume the existence of an attachment bond; while from the other instruments measuring the quality of attachment, the possibility of classifying children as secure or insecure allowed us to presumed the existence of an attachment bond. It is also important to note that in all these cases Western‐based instruments to measure attachment were used. The Latin‐American studies described here support Bowlby´s (1969/1982) idea of attachment as a universal (and evolutionary) phenomenon.

Regarding the normativity hypothesis, results showed that the majority of NRS, mainly consisting of TDC, were securely attached or had secure attachment representations. However, this predominance was not the pattern in most of the HRS (12 out of 13), characterized by at‐risk family circumstances, such as chronically underweight children, or children with history of maltreatment, including abuse, children institutionalized or in alternative care, and dyads in prison. As previously mentioned, normativity hypothesis as such, can only be expected to be met among populations without conditions that entail risk for typical development, and the aforementioned results support this idea. Moreover, when reviewing AQS results, most of NRS had average scores similar to or higher than the mean security score reported in the most recent meta‐analysis (Cadman et al., 2017), and when this was not the case low scores were assumed to be due to the fact that they were based on mothers´ reports, that the interaction was assessed with secondary caregivers, that the samples consisted of very young children, or that the dyads were characterized by low‐SES backgrounds. However, in those cases in which reasons were not totally clear, a qualitative approach that allows for a better understanding of the potential cultural‐specific patterns needs to be conducted.

The findings from samples at risk underline the importance of socioeconomic characteristics in shaping parenting and child development (Conger & Donnellan, 2007; Emmen et al., 2013; Mesman et al., 2012). This is a particularly relevant issue considering that 72 million children (around 37%) live in moderate or extreme poverty in Latin American and the Caribbean, and that poverty is higher among children who live in remote rural areas and peri‐urban setting or among indigenous or afro‐descendant population (Unicef, 2021). The question is then, what is normative in this broader socio‐economic context? More variety in study populations would help us answer that question. Most of the participants in studies reviewed are not poor. Even though a few publications included extremely poor dyads or population from rural areas, the majority of studies are conducted with middle class urban samples, mainly due to the accessibility and practical reasons. Unfortunately, as it was not possible to report specific SES levels of all samples, due to their lack or the diversity of ways in which it was reported, we acknowledge the disadvantage this represents to provide a broader understanding of the impact of socioeconomic background in child development.

The universality of sensitivity and the association between sensitivity and child secure attachment, that is to say sensitivity hypothesis, were also well‐supported. Firstly, according to the criteria set by the instruments in question, most of the NRS showed adequate levels of sensitive responsiveness, whereas lower average sensitivity scores were observed mainly in at‐risk caregivers. In addition, support for the presence and relevance of the idea of sensitive behavior within Latin American population has been provided by a study that reported convergence between maternal beliefs of the ideal sensitive mother and attachment theory's description of the sensitive mother in seven cultural groups of four Latin American countries (Mesman, van IJzendoorn, Behrens et al., 2016). Secondly, the significant association between sensitivity and attachment security was supported in almost all samples in which it was tested (11 out of 14).

Finally, some support was also found for the competence hypothesis, along with some support for the significant relation of secure attachment and caregiver sensitivity with other positive child outcomes, although these were addressed in only a few studies. Interestingly, there were more studies testing the relation between caregivers’ sensitivity and positive child outcomes than studies testing the relation between child attachment quality and social‐cognitive competence and other child outcomes. Most of the studies testing these relations proved that both child attachment security and caregivers’ sensitivity were relevant antecedents for a more positive developmental functioning of children. The low number of this type of studies is not specific to Latin America (Mesman, van IJzendoorn, & Sagi‐Schwartz, 2016), and this scarcity is striking considering that the claim that early child attachment security is vital for promoting positive development across the life span is central to attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969/1982). At best, this signals an urgent need for further research to empirically clarify the nature and strength of the contribution of caregiver‐child attachment and caregiver´s sensitive behavior to children's development. At worst, it raises suspicions about non‐significant results in file drawers, casting doubt on the actual predictive value of attachment security for child developmental outcomes.

Attachment‐based intervention studies were by far the least represented in this review and only one of the included programs (VIPP‐SD; Juffer et al., 2008) was on the list of those identified as having the strongest evidence for effectiveness in Western samples (Berlin et al., 2016). The lack of this type of studies could be related to the relative complexity of conducting such research, given that they require more involvement, and longer commitment from participants, as repeated visits are required. Challenges such as cultural differences, limited funding for enough participants, insufficient familiarity of participants with this type of program, and lack of workplace support hinder the implementation of interventions in low‐SES countries (Hailemariam et al., 2019). All of the attachment‐based intervention studies were published in the last decade, and eight out of nine were conducted in Chile, showing that this type of studies is a novelty in Latin America attachment research, in contrast to the international literature in which this type of studies has been produced over three decades (Woodhouse, 2018). Regarding the performance of attachment‐based interventions, most of the publications reported some level of effective functioning, generally showing an increase in caregivers´ sensitive behavior and to a lesser extent in child secure attachment. Interestingly, all nine studies used a different intervention program, and none of them were used more than once, suggesting that the theoretical focus rather than the precise content could contribute to their success.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This narrative literature review represents a first step in the process of systematically collecting and describing studies rooted in attachment theory in Latin America. However, some additional steps need to be taken. Future reviews could include studies on older children, adolescents, or adults, as well as other assessment approaches, in order to gradually achieve a better and broader insight into attachment research in Latin American countries. But more importantly, acknowledging that there is still a debate on the universality versus culture‐specificity of attachment theory and its applicability in non‐Western countries, reviews of Latin American studies related to parenting and caregiver‐child interactions rooted in local concepts and theoretical points of view need to be conducted. The scholarly literature on parenting would benefit from combining insights from etic and emic approaches (Corona & Maldonado, 2018; Helfrich, 1999) that allow for the recognition and understanding of cultural patterns and practices related to the concepts of sensitivity and attachment in the Latin American region and beyond.

Fourment, K. , Espinoza, C. , Ribeiro, A. C. L. , & Mesman, J. (2022). Latin American Attachment studies: A narrative review. Infant Mental Health Journal, 43, 653–676. 10.1002/imhj.21995

REFERENCES

- Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44(4), 709–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M. D. S. , Bell, S. M. , & Stayton, D. J. (1974). Infant–mother attachment and social development: ‘‘Socialization’’ as a product of reciprocal responsiveness to signals. In Richards M.P.M. (Ed.), The integration of a child into a social world (pp. 99–135). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M. D. S. , Blehar, M. C. , Waters, E. , & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Erlbaum. 10.4324/9781315802428 [DOI] [Google Scholar]