Abstract

Sweat discharged as a result of exposure to sauna plays an important role in removing inorganic ions accumulated in the body, including heavy metals. In this study, inorganic ions (toxic and nutrient elements) excreted in the form of sweat from the body using a water-filtered infrared-A (wIRA) sauna were determined using inductively coupled plasma sector field mass spectrometry. The analyzed elements included eight toxic elements (Al, As, Be, Cd, Ni, Pb, Ti, and Hg) and 10 nutrient elements (Ca, Co, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mg, Mn, Se, V, and Zn), and their correlations were determined. Analysis of the sweat obtained from 22 people using the wIRA sauna showed a higher inorganic ion concentration than that obtained from conventional activities, such as exercise or the use of wet sauna, and the concentration of toxic elements in sweat was higher in females than in males. Correlation analysis of the ions revealed a correlation between the discharge of toxic elements, such as As, Be, Cd, and Ni, and discharge of Se and V, and Ni was only correlated with Mn. This study provides fundamental information on nutritional element supplementation when using wIRA sauna for detoxification.

Keywords: Water-filtered infrared-A (wIRA), Sauna, Sweat, Toxic elements, Nutrient

Introduction

A sauna induces thermal stress in the body and increases peripheral circulation as peripheral resistance decreases by approximately 40%. Increased peripheral blood flow via a sauna is equivalent to that achieved by moderate exercise and heat exchange with the skin, including diaphoresis (Vuori 1988). There is also evidence that aerobic exercise significantly favors to remove toxic elements from the body (Maynar-Marino et al. 2018). Thus, saunas could provide cardiovascular benefits and elimination of toxic elements for those living in climatic environment with limited exercise options in winter or in confined environment owing to infectious diseases, such as COVID-19. The use of saunas has been promoted worldwide owing to its health benefits; some common types of saunas include Roman baths, Aboriginal jjimjilbangs, Scandinavian saunas (dry heat, 40–60% relative humidity), and Turkish baths (with steam).

An infrared (IR) sauna, which is a recently developed dry sauna, uses IR rays to heat exposed skin tissue and can maintain an ambient temperature that is lower than that of other sauna methods. An IR sauna positively influences blood pressure in the body. In a study by Masuda et al. (Masuda et al. 2004), patients with coronary artery problems were provided with an IR sauna at 60 °C for 15 min daily for 2 weeks. The participants who received the IR sauna had significantly lower systolic blood pressure than those who did not (mean, 110 vs. 122 mmHg). Participants who received daily IR sauna therapy also had lower 8-epi-PGF2-alpha levels, suggesting lower oxidative stress. Ikeda et al. (Ikeda et al. 2005) reported an increase in nitric oxide production due to repeated IR saunas, which reduced blood pressure. Moreover, sweat discharged from exposure to saunas plays an important role in removing heavy metals accumulated in the body (Genuis et al. 2011). Sheng et al. (Sheng et al. 2016) analyzed the urine and sweat of 17 residents living near streams (Zhenjiang City, China) that contained high concentrations of heavy metals (Pb, Zn, Cd, Co, Ni, and Cu). They observed that the heavy metal concentrations in the urine and sweat samples of the residents who exercised were lower than those of the residents who did not exercise, and the heavy metal concentration in sweat was higher than that in the urine of participants. In addition, Genuis et al. (Genuis et al. 2011) analyzed the blood, urine, and sweat discharged through exercise and sauna by 20 participants. They found that Cu, Mn, Ni, U, Pb, Co, Cr, Al, Zn, and Hg were discharged more in sweat than in urine, and Tl, As, Se, and Mo were excreted through urine rather than through sweat.

Water-filtered infrared-A (wIRA) is a type of radiation that uses water to absorb infrared-B and infrared-C rays, which have long wavelengths, and separate IR-A rays. It has a high penetrating power into tissues, such as in human skin. Therefore, it is possible to deliver more energy to the deep regions of tissues with wIRA than with infrared rays, which are not filtered by water (Piazena and Kelleher 2010; Piazena et al. 2014). wIRA rays can penetrate the skin tissue of the body to a depth of approximately 2–3 cm. A study on clinical treatment using wIRA irradiation showed positive results in patients with ulcus cruris and superficial skin tumors, effectively inhibiting pain and maintaining body temperature in newborns (Akca et al. 1999; Hürlimann et al. 1998; Hoffmann 1994; Sugrue et al. 1990).

Sweat excreted through exercise or sauna can remove heavy metals from the body, but at the same time causes nutrient loss owing to the release of nutrients such as Ca and Mg. Since the body needs to replenish its nutritional supply, it is necessary to understand the intercorrelation between nutrients lost due to the excretion of heavy metals from the body. Therefore, in this study, inorganic ions (including toxic elements) present in body sweat discharged using a wIRA sauna were first identified, and their relationship with the discharged inorganic ions was analyzed.

Materials and methods

Participant recruitment

Participants were randomly recruited from among visitors in Sunhan Hospital (Gwangju, Korea) between January and May 2020. All participants had a clear understanding of the content and purpose of the experiment before commencing the study. Prior consent was obtained for the provision of information, and the collected data does not require Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. The exclusion criteria were as follows: minors under the age of 18, people older than 70 years, patients with major health problems (such as tuberculosis), patients diagnosed with inflammatory or infectious diseases within the last 6 months, those with skin conditions (eczema, psoriasis, and contact dermatitis), and those who did not consent to participate in the experiment. A total of 22 participants (6 men, 16 women) had an average age of 46.9 years (2.97 Std. Err.), and 21 patients had underlying conditions, such as headache, diabetes mellitus, and cancer. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and general clinical characteristics of participants

| No. | Sex | Age (year) |

Clinical diagnosis | Height (cm) |

Weight (kg) |

BMI† (kg/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 58 | Knee pain | 154 | 55 | 23.19 |

| 2 | M | 41 | Gastritis | 173 | 73 | 24.39 |

| 3 | F | 64 | Knee pain | 157 | 59 | 23.94 |

| 4 | F | 58 | Endometrial cancer | 162 | 58 | 22.10 |

| 5 | F | 26 | Wrist pain | 173 | 63 | 21.05 |

| 6 | M | 50 | Cerebral infarction | 165 | 75 | 27.55 |

| 7 | F | 52 | Neck pain | 157 | 62 | 25.15 |

| 8 | F | 26 | Healthy | 154 | 47 | 19.82 |

| 9 | F | 54 | Headache | 156 | 56 | 23.01 |

| 10 | F | 49 | Anemia | 153 | 50 | 21.36 |

| 11 | F | 61 | Gallbladder stone | 156 | 53 | 21.78 |

| 12 | M | 56 | Diabetes mellitus | 167 | 67 | 24.02 |

| 13 | F | 41 | Back pain | 161 | 62 | 23.92 |

| 14 | M | 63 | Headache | 171 | 56 | 19.15 |

| 15 | M | 41 | Diabetes mellitus | 179 | 91 | 28.40 |

| 16 | F | 42 | Hyperlipidermia | 153 | 50 | 21.36 |

| 17 | F | 34 | Herpes | 165 | 51 | 18.73 |

| 18 | F | 30 | Headache | 164 | 55 | 20.45 |

| 19 | F | 28 | Fatigue | 160 | 45 | 17.58 |

| 20 | F | 64 | Arthritis | 155 | 65 | 27.06 |

| 21 | F | 27 | Gastritis, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo | 165 | 72 | 26.45 |

| 22 | M | 67 | Gastric cancer | 170 | 56 | 19.38 |

†BMI, body mass index

Experimentation using wIRA sauna

The wIRA sauna device used to determine the inorganic element discharge characteristics from the body was a capsule-type device equipped with multiple lamp tubes using multiple halogen lamps in the shape of a bulb (Fig. 1). The wIRA-based thermotherapy device used in this study has a chamber shape with a lid of about 2.00 m in width × 0.66 m in length × 1.00 m in height. A total of 12 sets (18 per set) of halogen lamps (220 V, 28 W) for generating near-infrared rays were installed inside. The IR-A (wavelength range: 780–1400 nm) rays used in this study were separated from the IR rays generated by halogen lamps using a water-filtering method that circulates water in the lamp tube. Sweat discharged by the participants through the sauna was collected using a gravity-draining sweat collection storage device, and the collection was conducted for 30 min. The amount of sweat collected for 30 min was about 20 to 80 mL, which was about 0.1% of body weight, and the change in body weight was negligible. The sauna device was operated at room temperature, and the internal temperature of the device was maintained between 38.5 and 42.0 °C and the humidity was kept below 30%. Participants were asked to remove foreign substances from their skin by showering up to 6 h before the sauna and not apply moisturizers such as lotions to their skin after showering. They were also asked not to engage in strenuous exercise or labor that would make them sweat after showering.

Fig. 1.

Digital image of the wIRA sauna device used in this study

Sample collection and analytic methods

Sweat (at least 20 mL) from all body parts of the participants was collected using a sweat collection chamber installed in the wIRA sauna device. The sweat samples were stored in a − 20 °C freezer in capped 50 mL glass vials until analysis. Pre-treatment of the samples for quantitative analysis of the concentration of inorganic ions involved the preparation of a mixed solution of 1 mL of the sweat sample and 9 mL of aqua regia (nitric acid: hydrochloric acid = 3:1). A closed-vessel microwave-assisted digestion device (Mars6, CEM Corporation, USA) was used at a power of 1000 W, sample temperature of 200 °C, and irradiation for 60 min (Rodushkin et al. 2004). Chemical analysis was performed using inductively coupled plasma sector field mass spectrometry (ELAN 9000 ICP/MS, Perkin Elmer, USA) to determine the concentration of inorganic ions in the pretreated sample. The elemental analysis included the analysis of eight toxic elements (Al, As, Be, Cd, Ni, Pb, Ti, and Hg) and ten nutritional elements (Ca, Co, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mg, Mn, Se, V, and Zn). Analysis of the samples was performed in triplicate, and a one-tailed t-test was conducted at a 95% confidence level (p < 0.05) to confirm the difference between groups in a specific direction with superior statistical power.

Results and discussion

Effect of wIRA sauna on inorganic ions excretion

The concentrations of toxic elements in the sweat collected in this study were comparable with those reported in previous studies (Table 2). The results of this study showed higher concentrations for Hg (34.8 times), As (18.0 times), Pb (6.8–496.6 times), Cd (4.2–418.6 times), and Ni (8.9–11.4 times) than other studies (Table 3) (Genuis et al. 2011; Sheng et al. 2016; Siquier-Coll et al. 2020a; Tang et al. 2016). However, since the experimental conditions cannot be the same for each literature, more careful attention is needed in comparing the concentrations of discharged heavy metals. Siquier-Coll et al. (Siquier-Coll et al. 2020a) conducted an experiment at a temperature similar to that used in this study (~ 42 °C). The concentrations of Cd and Pb in the sweat from this study were 24.8 times and 8.3 times higher, respectively. Conversely, Kuan et al. (Kuan et al. 2022) reported that the removal of heavy metals from the body through dynamic exercise could be more effective than removal through static exposure to a hot environment.

Table 2.

Statistics of chemical analysis results for inorganic ions in collected sweat samples (unit: μg/L)

| Toxic | Nutritional | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elements | Mean | Std.Err | Elements | Mean | Std.Err |

| Al | 5594.93 | 493.74 | Ca | 38,577.00 | 3568.06 |

| As | 102.36 | 16.69 | Co | 32.55 | 3.90 |

| Be | 22.81 | 5.39 | Cr | 1551.80 | 62.32 |

| Cd | 29.30 | 6.11 | Cu | 759.26 | 68.79 |

| Ni | 876.29 | 75.49 | Fe | 16,607.34 | 2067.75 |

| Pb | 312.85 | 29.84 | Mg | 8949.23 | 618.18 |

| Tl | 1.49 | 0.36 | Mn | 195.99 | 17.81 |

| Hg | 29.90 | 2.03 | Se | 68.14 | 13.14 |

| V | 58.50 | 7.01 | |||

| Zn | 1247.80 | 162.25 | |||

Std. Err., standard error

Table 3.

Comparison of concentration analysis results of toxic elements in collected sweat samples (this study) with other (reference) data (unit: μg/L)

| Elements | This study | Genuis et al. (Genuis et al. 2011) | Sheng et al. (Sheng et al. 2016) | Tang et al. (Tang et al. 2016) | Siquier-Coll et al. (Siquier-Coll et al. 2020a) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 5594.93 | 5100.55 | - | - | - |

| As | 102.36 | 5.7 | - | - | - |

| Be | 22.81 | - | - | - | - |

| Cd | 29.3 | 7.02 | 0.552 | 0.07 | 1.18 |

| Ni | 876.29 | 100.84 | 78.764 | - | - |

| Pb | 312.85 | 31.04 | 45.808 | 0.63 | 37.86 |

| Tl | 1.49 | 0.11 | - | - | - |

| Hg | 29.9 | 0.86 | - | - | - |

| Method | wIRA sauna |

Exercise Steam sauna Infrared sauna |

Exercise | Exercise | Sauna |

When the thermal load applied to the body through sauna increases, the body activates heat-consuming mechanisms such as sweating. At this time, blood flow to the skin increases by approximately 5–10% and cardiac output increases by 60–70% (Hannuksela and Ellahham 2001; Leppäluoto 1988). The IR generated from the wIRA sauna device has a high skin penetration ability and hence can react with the eccrine sweat glands of the coiled tubular glands under the skin surface more effectively than a conventional sauna (Levisky et al. 2000), consequently increasing the concentration of heavy metal ions in discharged sweat. Although the amount of sweat collected for 30 min was at least 20 mL, the presented data has a limitation that the amount of sweat was not corrected because the concentration was included in 1 mL of the sweat sample.

Sweat characteristics according to gender and clinical diagnoses

The concentrations of toxins and nutrients in excreted sweat were compared according to the sex of the participants. Although the age of male (mean age of 53.0 years, standard error [Std. Err.] of 4.48) was higher than that of female (mean age of 44.6 years, Std. Err. of 3.63), the average concentration in sweat was higher in female than in male (Table 4). These results can be attributed to the fact that females generally sweat less than males (Smith and Havenith 2012). However, there was no statistical difference in the data for each element (p > 0.05). Nonetheless, these results corroborate those of previous studies. Sheng et al. (Sheng et al. 2016) analyzed the concentration of heavy metals in the blood of local residents near rivers containing high concentrations of heavy metals. Baker (Baker 2017) stated that body mass, body composition, sex, menstrual cycle phase, maturation, aging, medications, medical conditions, and genetics play an important role in the characteristics of ions in sweat discharged due to exercise and sweating. In a study by Genuis et al. (Genuis et al. 2011), inorganic ions in the sweat of participants (9 men, 11 women) discharged through exercise and sauna (including steam and infrared sauna) were analyzed. They found that the concentrations of As, Al, Bi, Co, Cr, Cu, Mn, Mo, Ni, Pb, and Zn were higher in women than in men.

Table 4.

Average of chemical analysis results for inorganic ions in collected sweat samples (unit: μg/L) according to gender

| Toxic | Nutritional | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elements | Female | Male | F/M ratio | Elements | Female | Male | F/M ratio |

| Al | 5715.96 | 5272.20 | 1.08 | Ca | 40,833.00 | 32,561.00 | 1.25 |

| As | 109.47 | 83.41 | 1.31 | Co | 34.44 | 27.51 | 1.25 |

| Be | 24.81 | 17.48 | 1.42 | Cr | 1573.05 | 1495.12 | 1.05 |

| Cd | 32.35 | 21.18 | 1.53 | Cu | 820.33 | 596.41 | 1.38 |

| Ni | 907.33 | 866.81 | 1.05 | Fe | 17,269.09 | 14,842.67 | 1.16 |

| Pb | 326.20 | 277.26 | 1.18 | Mg | 9359.19 | 7856.00 | 1.19 |

| Tl | 1.61 | 1.17 | 1.38 | Mn | 202.31 | 179.15 | 1.13 |

| Hg | 30.66 | 27.85 | 1.10 | Se | 73.02 | 55.11 | 1.33 |

| V | 62.19 | 48.69 | 1.28 | ||||

| Zn | 1192.15 | 1396.20 | 0.85 | ||||

F/M, female to male

In the sweat of participants with severe diagnoses such as cancer (#4, #22), cerebral infarction (#6), and diabetes (#12, #15), the average concentration of all components except for Zn was up to 35% lower (Al (0.95), As (0.80), Be (0.83), Cd (0.76), Ni (0.93), Pb (1.00), Tl (0.78), Hg (0.97), Ca (0.65), Co (0.85), Cr (0.96), Cu (0.78), Fe (0.91), Mg (0.87), Mn (0.90), Se (0.83), V (0.89)) than that of participants with mild diagnoses such as knee pain, headache, and anemia, etc. It might be due to the effect of sweating response to medication that interfere with neural sudomotor mechanisms (e.g. anticholinergics and antidepressants such as amitriptyline) (Baker 2017). Interestingly, the excretion of Zn (1.50) was increased, and this opposite trend was consistent with the comparison according to gender (Table 4). Although statistical significance was not found for most of the elements, only Ca showed a significant difference (p < 0.05) among the participants.

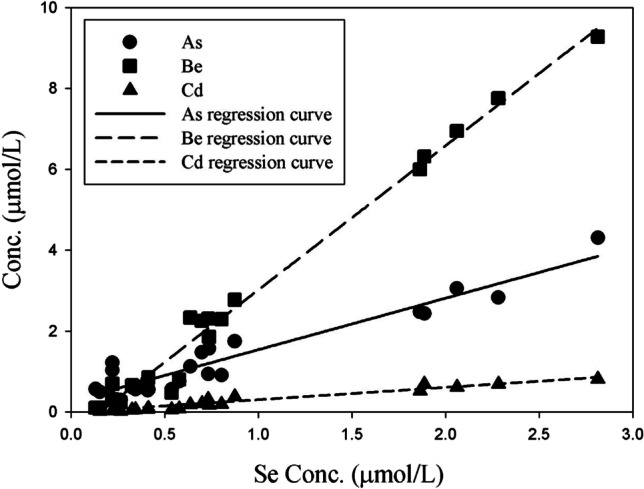

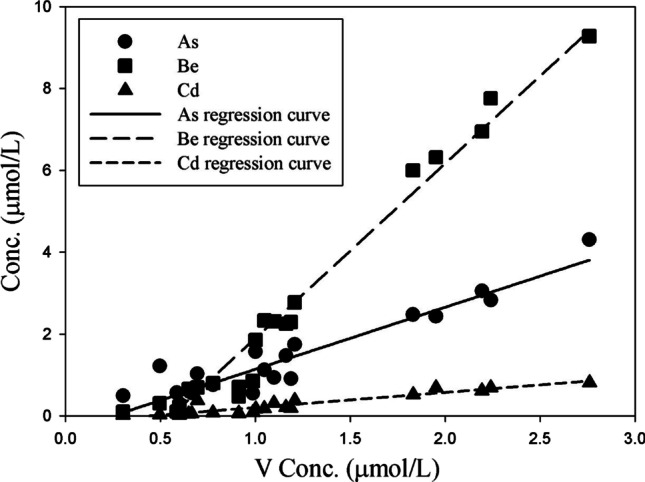

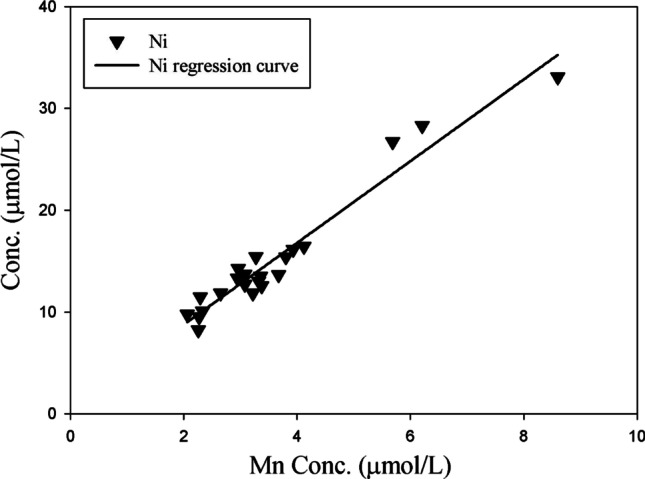

Correlation between inorganic elements

This study tried to focus on the correlation between toxic and nutritional elements contained in the same amount of sweat (1 mL), and a correlation analysis was performed to determine the correlation between nutrients and toxic elements in sweat discharged via wIRA sauna (Table 5). Among the eight toxic elements, the discharge characteristics of Al, Pb, and Hg were not related to those of the nutrient elements. However, As, Be, Cd, and Tl were positively correlated with Co, Se, and V (correlation coefficient of 0.7 or higher), and Ni was only correlated with Mn (correlation coefficient of 0.98). In particular, the nutrient elements Se and V showed very high correlation coefficients of 0.9 or more with As, Be, and Cd. This indicates the need to supplement the body with nutrients, as Se and V are discharged simultaneously with toxic elements when using wIRA sauna. In a similar study, Siquier-Coll (Siquier-Coll et al. 2020b) also reported that supplementation of Zn and Se may be necessary in hot environments. Based on correlation analysis, a relationship diagram is presented for the highly correlated nutrient elements Se and V and the toxic elements As, Be, and Cd (Figs. 2 and 3). Se and V showed very high determination coefficients (0.8684–0.9857) for the toxic elements As, Be, and Cd. In addition, Mn exhibited a determination coefficient of 0.9446 for Ni (Fig. 4). This indicates that the concentrations of Se, V, and Mn in the body decrease when toxins are discharged from the body through sweat using the wIRA sauna. Meanwhile, the usefulness of sweat components as biomarkers for human physiology is currently limited (Baker 2019). Therefore, more studies are needed to determine the potential relationship between sweat composition and physiological mechanisms.

Table 5.

Correlation analysis result between inorganic elements in excreted sweat

| Al | As | Be | Cd | Ni | Pb | Tl | Hg | Ca | Co | Cr | Cu | Fe | Mg | Mn | Se | V | Zn | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||

| As | 0.03 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| Be | − 0.04 | 0.96 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| Cd | 0.22 | 0.91 | 0.94 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| Ni | − 0.12 | 0.19 | − 0.04 | − 0.08 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| Pb | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| Tl | 0.05 | 0.90 | 0.84 | 0.78 | 0.39 | 0.24 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| Hg | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.39 | 0.13 | 0.52 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| Ca | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.06 | − 0.12 | − 0.25 | − 0.11 | − 0.45 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| Co | − 0.08 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.74 | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.96 | 0.41 | − 0.03 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Cr | − 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.01 | − 0.03 | 0.39 | 0.10 | 0.05 | − 0.34 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 1.00 | |||||||

| Cu | 0.05 | 0.65 | 0.59 | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.73 | 0.56 | 0.01 | 0.71 | − 0.21 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Fe | − 0.15 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.26 | 0.29 | − 0.10 | 0.32 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 1.00 | |||||

| Mg | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 0.45 | − 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.28 | − 0.09 | 0.43 | 0.53 | 1.00 | ||||

| Mn | − 0.03 | 0.17 | − 0.05 | − 0.09 | 0.98 | 0.23 | 0.41 | 0.48 | − 0.23 | 0.51 | 0.41 | 0.31 | 0.19 | − 0.14 | 1.00 | |||

| Se | − 0.08 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.91 | − 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.84 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.82 | − 0.03 | 0.63 | 0.29 | 0.42 | − 0.06 | 1.00 | ||

| V | − 0.08 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.91 | − 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.78 | 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.77 | − 0.02 | 0.56 | 0.27 | 0.41 | − 0.14 | 0.99 | 1.00 | |

| Zn | 0.01 | − 0.19 | − 0.35 | − 0.38 | 0.33 | − 0.02 | − 0.14 | 0.41 | − 0.14 | − 0.09 | − 0.31 | 0.38 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.31 | − 0.28 | − 0.34 | 1.00 |

Fig. 2.

Relationship between Se and other toxic elements in excreted sweat

Fig. 3.

Relationship between V and other toxic elements in excreted sweat

Fig. 4.

Relationship between Mn and Ni in excreted sweat

Conclusion

In this study, the characteristics of inorganic ions in sweat discharged using a wIRA sauna were analyzed to remove toxic elements accumulated in the body. The findings are as follows:

Chemical analysis of the concentration of inorganic ions in sweat discharged from the skin of 22 participants using the wIRA sauna device was performed. Al was detected among the toxic elements, whereas Ca, Fe, and Mg were detected among the nutrient elements at relatively high concentrations. The detected concentrations were higher than those obtained in previous studies using sweat discharged through exercise and wet saunas.

The characteristics of inorganic ion excretion from sweat were determined according to the sex of the participants. The average concentration of toxic elements in the sweat of females was higher than that of males, although the males were older than the females on average.

Correlation analysis to determine the correlation between nutrient elements and toxic elements in sweat showed that the characteristics of Al, Pb, and Hg (toxic elements) were not related to the nutrient characteristics. However, As, Be, Cd, and Tl were correlated with Co, Se, and V, and Ni was only correlated with Mn.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Kang-hee Cho, Sung-hun Jung, Min-sun Choi, and Yong-jin Jung. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Chang-Gu Lee and Nag-choul Choi, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is a study on human subjects, does not include subjects in a vulnerable environment, and does not collect or record personally identifiable information. In addition, although this study directly manipulates the subject or the environment, it does not involve invasive actions such as drug administration or blood collection, and it corresponds to a study using only simple contact measurement equipment or observation equipment that does not follow physical changes, so it was not reviewed by the IRB in accordance with Article 13 of the Enforcement Rule of Bioethics and Safety Act (https://www.irb.or.kr/menu02/commonDeliberation.aspx (accessed on 14 September 2022)).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Kang-hee Cho and Chang-Gu Lee contributed equally to this work.

References

- Akca O, et al. Postoperative pain and subcutaneous oxygen tension. Lancet. 1999;354:41–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)00874-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LB. Sweating rate and sweat sodium concentration in athletes: a review of methodology and intra/interindividual variability. Sports Med. 2017;47:111–128. doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0691-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LB. Physiology of sweat gland function: the roles of sweating and sweat composition in human health. Temperature. 2019;6:211–259. doi: 10.1080/23328940.2019.1632145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genuis SJ, Birkholz D, Rodushkin I, Beesoon S. Blood, urine, and sweat (BUS) study: monitoring and elimination of bioaccumulated toxic elements. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2011;61:344–357. doi: 10.1007/s00244-010-9611-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannuksela ML, Ellahham S. Benefits and risks of sauna bathing. Am J Med. 2001;110:118–126. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00671-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann G. Oxygen Transport to Tissue XV. Berlin: Springer; 1994. Improvement of wound healing in chronic ulcers by hyperbaric oxygenation and by waterfiltered ultrared A induced localized hyperthermia; pp. 181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hürlimann A, Hänggi G, Panizzon R. Photodynamic therapy of superficial basal cell carcinomas using topical 5-aminolevulinic acid in a nanocolloid lotion. Dermatology. 1998;197:248–254. doi: 10.1159/000018006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda Y, et al. Repeated sauna therapy increases arterial endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression and nitric oxide production in cardiomyopathic hamsters. Circ J. 2005;69:722–729. doi: 10.1253/circj.69.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuan WH, Chen YL, Liu CL (2022) Excretion of Ni, Pb, Cu, As, and Hg in sweat under two sweating conditions. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19. 10.3390/ijerph19074323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Leppäluoto J. Human thermoregulation in sauna. Ann Clin Res. 1988;20:240–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levisky JA, Bowerman DL, Jenkins WW, Karch SB. Drug deposition in adipose tissue and skin: evidence for an alternative source of positive sweat patch tests. Forensic Sci Int. 2000;110:35–46. doi: 10.1016/S0379-0738(00)00146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda A, Miyata M, Kihara T, Minagoe S, Tei C. Repeated sauna therapy reduces urinary 8-Epi-Prostaglandin F 2α. Jpn Heart J. 2004;45:297–303. doi: 10.1536/jhj.45.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynar-Marino M, Llerena F, Bartolome I, Crespo C, Munoz D, Robles MC, Caballero MJ. Effect of long-term aerobic, anaerobic and aerobic-anaerobic physical training in seric toxic minerals concentrations. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2018;45:136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazena H, Kelleher DK. Effects of infrared-A irradiation on skin: discrepancies in published data highlight the need for an exact consideration of physical and photobiological laws and appropriate experimental settings. Photochem Photobiol. 2010;86:687–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2010.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazena H, Meffert H, Uebelhack R. Physical and photobiological basics for prophylactic and therapeutic application of infrared radiation. Aktuelle Dermatol. 2014;40:335–339. [Google Scholar]

- Rodushkin I, Engström E, Stenberg A, Baxter DC. Determination of low-abundance elements at ultra-trace levels in urine and serum by inductively coupled plasma–sector field mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2004;380:247–257. doi: 10.1007/s00216-004-2742-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng J, Qiu W, Xu B, Xu H, Tang C. Monitoring of heavy metal levels in the major rivers and in residents’ blood in Zhenjiang City, China, and assessment of heavy metal elimination via urine and sweat in humans. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2016;23:11034–11045. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-6287-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siquier-Coll J, Bartolomé I, Pérez-Quintero M, Muñoz D, Robles M, Maynar-Mariño M. Effect of exposure to high temperatures in the excretion of cadmium and lead. J Therm Biol. 2020;89:102545. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2020.102545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siquier-Coll J, Bartolome I, Perez-Quintero M, Munoz D, Robles MC, Maynar-Marino M. Influence of a high-temperature programme on serum, urinary and sweat levels of selenium and zinc. J Therm Biol. 2020;88:102492. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2019.102492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CJ, Havenith G (2012) Body mapping of sweating patterns in athletes: a sex comparison. Med Sci Sports Exerc 44:2350–2361 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sugrue M, Carolan J, Leen E, Feeley T, Moore D, Shanik G. The use of infrared laser therapy in the treatment of venous ulceration. Ann Vasc Surg. 1990;4:179–181. doi: 10.1007/BF02001375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang S, Yu X, Wu C. Comparison of the levels of five heavy metals in human urine and sweat after strenuous exercise by ICP-MS. J Appl Math Phys. 2016;4:183–188. doi: 10.4236/jamp.2016.42022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vuori I. Sauna bather's circulation. Ann Clin Res. 1988;20:249–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]