Dear editor

We read with great interest the paper by Kim et al. suggesting KL-6 and IL-6 as predictive markers in severely ill Covid-19 patients.1 The gene for CXCR6, the receptor for the chemokine CXCL16, has been showed to be negatively correlated with disease severity in Covid-19 disease.2 Several studies has demonstrated that soluble CXCL16 gives prognostic information in cardiovascular and inflammatory disorders3, 4, 5, 6 and CXCL16 expression is reported to be increased in lung macrophages in moderate compared to severe Covid-19.7 But most studies have focused on the expression of its receptor CXCR6, and the prognostic value of CXCL16 in Covid-19 is not known.

In the present study we examined the prognostic value of circulating CXCL16 levels (examined by enzyme immunoassay) in two separate cohorts of hospitalized Covid-19 patients in Norway compromising the first three waves of the Covid-19 pandemic (March 2020-September 2021). For more details on materials and methods, see Supplemental file.

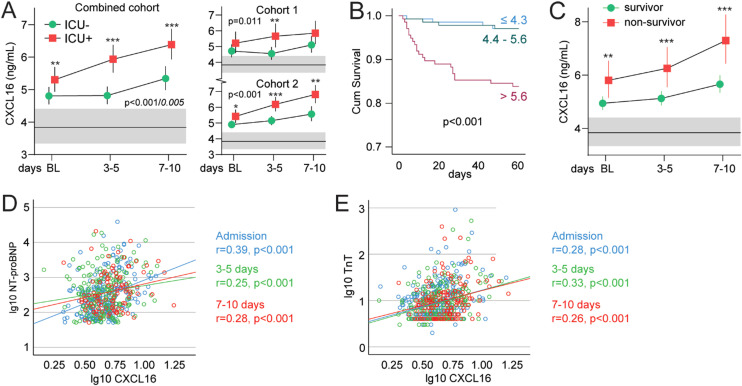

In our combined cohort, 110 of 414 patients (27%) were admitted to intensive care unit (ICU), and 125 (31%) patients developed respiratory failure (RF; i.e., P/F-ratio < 26.6 kPa) the first 10 days after admission (Table 1 ). CXCL16 levels were significantly higher in ICU patients as compared to patients not admitted to ICU, as evaluated by a linear mixed model adjusting for age, sex, specific Covid-19 treatment (randomized controlled trial [RCT] in cohort 1, dexamethasone use in cohort 2), eGFR and CRP (Fig. 1 A). CXCL16 levels increased in both groups during hospitalization, but the increase was more pronounced in the ICU group. The same pattern was seen for patients with RF (Fig. S1). In the combined cohort, 37 of 414 patients died within 60 days of hospital admission (Table 1). Kaplan-Meier analysis of admission levels showed that patients in the upper tertile of CXCL16 were at increased risk of death within 60 days (Fig. 1B). Evaluated as a continuous variable, a one SD increase in CXCL16 was associated with a 2.11 (95% CI 1.60–2.78, p < 0.001) times higher risk of death. The increased risk of death was present in patients treated with dexamethasone (HR 1.83, p = 0.001), but especially in those not treated with dexamethasone (HR 2.51, p < 0.001). The association of CXCL16 with 60-day total mortality was still significant (HR 1.50 [1.08–2.10] p = 0.017) after adjustments for other predictors of unfavorable outcomes such as age, sex, randomized treatment (cohort 1), dexamethasone use (cohort 2), eGFR and CRP (Fig. S2). Evaluation of the temporal profile during the first 10 days after inclusion revealed that patients who died had consistently higher levels of CXCL16 than survivors, with the largest differences at the end of the observation period (Fig. 1C).

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical, and biochemical characteristics in 414 patients hospitalized for Covid-19, stratified by two large multi-center cohorts in Norway.

| Parameter | Cohort 1 n = 162 |

Cohort 2 n = 252 |

Combined n = 414 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 59.7 ± 15.4 | 57.0 ± 15.3 | 58.0 ± 15.4 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 103 (64) | 159 (63) | 262 (63) |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | 28.2 ± 4.6 | 28.8 ± 5.2 | 28.5 ± 4.9 |

| Treatment group | |||

| Standard of Care (SoC), n (%) | 81 (50) | 254 (100) | 333 (80) |

| SoC + Hydroxychloroquine, n (%) | 43 (27) | 0 (0) | 43 (10) |

| SoC + Remdesivir, n (%) | 38 (24) | 0 (0) | 38 (9) |

| Dexametasone | 2 (1) | 134 (53)* | 136 (33) |

| Oxygen therapy | 91 (56) | 194 (77)* | 285 (69) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Chronic cardiac disease, n (%) | 24 (15) | 47 (19) | 71 (17) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 51 (32) | 84 (35) | 135 (34) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease, n (%) | 31 (20) | 67 (27) | 98 (24) |

| Obesity, n (%) | 43 (29) | 70 (28) | 113 (28) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 27 (17) | 58 (25) | 85 (22) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 5 (4) | 16 (7) | 21 (6) |

| Outcomes | |||

| ICU admission, n (%) | 31 (19) | 79 (31)* | 110 (27) |

| Respiratory failure, n (%) | 50 (31) | 75 (30) | 125 (31) |

| 60-day death, n (%) | 8 (5) | 29 (12) | 37 (9) |

| P/F-ratio at admission, kPa | 42.4 (32.4,49.6) | 40.0 (28.1,48.3) | 41.3 (30.0,49.3) |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.2 ± 1.5 | 12.9 ± 1.8 | 13.0 ± 1.7 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 70 (35,136) | 53 (24,117) | 62 (29,125) |

| Ferritin, µg/L | 612 (358,1111) | 617 (297,1146) | 615 (322,1127) |

| White blood cell count, x 109/L | 6.5 ± 2.8 | 6.9 ± 3.2 | 6.7 ± 3.1 |

| Neutrophils, x 109/L | 4.8 ± 2.7 | 5.3 ± 3.1 | 5.1 ± 3.0 |

| Lymphocytes, x 109/L | 1.2 ± 0.53 | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 1.1 ± 0.5 |

| eGFR | 87 ± 25 | 90 ± 29 | 89 ± 27 |

Continuous data are given as mean ± SD or median (25th, 75th) percentile.

Abbrevations: SoC; standard of care, ICU; intensive care unit, P/F-ratio; PaO2/FiO2-ratio; eGFR; estimated glomerular filtration rate.

*P < 0 .05 between cohorts 1 and 2.

Fig. 1.

Intra-hospital temporal profile of CXCL16 according to (A) ICU admission during the first 10 days after inclusion in the combined cohort and within cohorts. (B) CXCL16 and 60-day mortality in severe Covid-19. (C) Temporal profile of CXCL16 during the first 10 days after inclusion according to 60-day mortality. (D) Correlation plot between CXCL16 and NT-proBNP and (E) TnT during the first 10 days after inclusion. Blue circles are at admission, green circles at 3–5 days and red circles at 7–10 days. The correlation coefficients are Pearson. The p-values reflect the group (outcome) effect from the linear mixed models and the interaction p-value (group*time) is shown in italic if significant. gray areas reflect reference value range from age- and sex-matched healthy controls. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 between groups. BL; baseline, RF; acute respiratory failure, ICU; intensive care unit; NT-proBNP; N-terminal-pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, Tnt; Troponin.

Due to its known role in cardiovascular pathologies, we explored the association between CXCL16 and markers of cardiac function. Mixed models regression with NT-proBNP as dependent and CXCL16 and time as covariates, revealed a positive correlation (Estimate 0.05, t = 4.9, p < 0.001). We found a similar correlation with TnT as dependent variable (Estimate 0.03, t = 5.6, p < 0.001). Both markers showed a consistent correlation across all time-points (Fig. 1D, E). Partial correlation analysis, controlling for the P/F ratio, revealed little influence of respiratory function on the association between CXCL16 and NT-proBNP (admission r = 0.36, p < 0.001; 3–5 days r = 0.18, p = 0.013; 7–10 days r = 0.26, p = 0.003) or TnT (admission r = 0.27, p < 0.001; 3–5 days r = 0.21, p = 0.002; 7–10 days r = 0.26, p = 0.003).

To obtain further insight into the regulation of CXCL16 and its receptor CXCR6 in relation to cardiac involvement during Covid-19 disease, we evaluated the expression of CXCL16/CXCR6 in cardiac related cells exposed to SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro and in cardiac tissue samples from Covid-19 patients in RNA sequencing datasets deposited in public repositories (Supplemental Table S1). Despite some discrepancies, it seems that CXCL16 may be expressed within the myocardium of Covid-19 patients. In particular, when extracting CXCL16/CXCR6 RNA expression from a Covid-19 tissue atlas,8 using a single cell approach in autopsy cardiac tissue samples from 15 Covid patients and 28 healthy controls, we found increased expression of CXCL16, but not of CXCR6, in cardiac fibroblasts and to some degree also in cardiac macrophages, as compared with controls (Fig. S3).

Recently, Smieszek et al. reported elevated CXCL16 levels in hospitalized Covid-19 patients as compared to healthy controls, with the highest levels in those with the most severe disease, according to the current WHO classification.9 In the present study we extend these findings by including a larger number of patients (414 versus 141 patients), from two separate cohorts, recruited during the first three waves of Covid-19 that also included dexamethasone treatment that was used as SoC since autumn 2020. Our findings suggest that CXCL16 could be a novel and robust marker of Covid-19 severity including total mortality, and potentially also cardiac involvement during hospitalization. Interestingly, whereas patients with and without dexamethasone treatment showed similar CXCL16 levels at inclusion, patients that received dexamethasone showed increased CXCL16 levels during follow-up, possibly reflecting more severe disease in dexamethasone user, and/or indicating the need for additional treatment modalities in these patients.

The present study has some limitations such as lack of data on CXCL16 expression in immune cells and pulmonary tissue. We also lack cardiac imaging data from the hospitalized Covid-19 patients and the data on association with cardiac involvement should be interpreted cautiously. Moreover, correlations do not necessarily mean any causal relationship. Although our study included data from the three first waves of SARS-CoV-2, we lack data from Covid-19 disease driven by the omicron variant.

In sum, we show that a significant elevated CXCL16 at admission and during hospitalization were associated with adverse outcome such as RF, the need for treatment at ICU and 60-day total mortality also after adjusting for several variables including CRP. High levels of CXCL16 were also associated with cardiac involvement during hospitalization as assessed by high levels of TnT and NT-proBNP. Our findings suggest that CXCL16 could be a novel and reliable marker for adverse outcome in hospitalized Covid-19 patients, potentially also involved in the pathogenesis of severe Covid-19 disease including myocardial injury.

Declaration of Competing Interest

JCH and AMDR has received funding from Vivaldi Invest A/S owned by Jon Stephenson von Tetzchner; LH has stock ownership in Algipharma AS; ARH has received honoraria from Pfizer for lectures: TE is former (immediate past) President European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. The other authors report no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study received the following funding: Oslo University Hospital, Research Council of Norway (Grant No. 312780), South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (Grant No. 2021—071) and a philantropic donation from Vivaldi Invest A/S owned by Jon Stephenson von Tetzchner. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, or decision to publish this article.

Study group members

The Norwegian SARS-CoV-2 study group investigators are:

Cathrine Austad, Mette Bogen, Anne Hermann, Karl Erik Müller, Hanne Opsand, Trude Steinsvik, Bjørn Martin Woll (Vestre Viken Hospital Trust ); Erik Egeland Christensen, Susanne Dudman, Kristin Eftestøl, Børre Fevang, Beathe Kiland Granerud, Liv Hesstvedt, Synne Jenum, Marthe Jøntvedt Jørgensen, Elisabeth Toverud Landaas, Andreas Lind, Sarah Nur, Vidar Ormaasen, Frank Olav Pettersen, Else Quist-Paulsen, Dag Henrik Reikvam, Kjerstin Røstad, Linda Skeie, Anne Katrine Steffensen, Birgitte Stiksrud, Kristian Tonby (Oslo University Hospital); Berit Gravrok, Vegard Skogen, Garth Daryl Tylden (University Hospital of North Norway); Simen Bøe (Hammerfest County Hospital).

The NOR-SOLIDARITY consortium members are:

Jan Terje Andersen, Anette Kolderup, Trine Kåsine, Fridtjof Lund-Johansen, Inge Christoffer Olsen, Karoline Hansen Skåra, Trung Tran, Cathrine Fladeby, Liv Hesstvedt, Mona Holberg-Petersen, Synne Jenum, Simreen Kaur Johal, Dag Henrik Reikvam, Kjerstin Røstad, Anne Katrine Steffensen, Birgitte Stiksrud, Eline Brenno Vaage, Erik Egeland Christensen, Marthe Jøntvedt Jørgensen, Fridtjof Lund-Johansen, Sarah Nur, Vidar Ormaasen, Frank Olav Pettersen (Oslo University Hospital); Saad Aballi, Jorunn Brynhildsen, Waleed Ghanima, Anne Marie Halstensen (Østfold Hospital Trust); Åse Berg (Stavanger University Hospital); Bjørn Blomberg, Reidar Kvåle, Nina Langeland, Kristin Greve Isdahl Mohn (Haukeland University Hospital); Olav Dalgard (Akershus University Hospital); Ragnhild Eiken, Richard Alexander Molvik, Carl Magnus Ystrøm (Innlandet Hospital Trust); Gernot Ernst, Lars Thoresen (Vestre Viken Hospital Trust); Lise Tuset Gustad, Lars Mølgaard Saxhaug, Nina Vibeche Skei (Nord-Trøndelag Hospital Trust); Raisa Hannula (Trondheim University Hospital); Mette Haugli, Roy Bjørkholt Olsen (Sørlandet Hospital Trust); Dag Arne Lihaug Hoff (Ålesund Hospital); Asgeir Johannessen, Bjørn Åsheim-Hansen (Vestfold Hospital Trust); Bård Reikvam Kittang (Haraldsplass Deaconess Hospital); Lan Ai Kieu Le (Haugesund Hospital); Ravinea Manotheepan, Hans Schmidt Rasmussen, Grethe-Elisabeth Stenvik, Ruth Foseide Thorkildsen, Leif Erik Vinge (Diakonhjemmet Hospital); Pawel Mielnik (Førde Hospital); Vegard Skogen (University Hospital of North Norway); Hilde Skudal (Telemark Hospital Trust); Birgitte Tholin (Molde Hospital).

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2022.09.029.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Kim S.H., et al. Diagnostic value of serum KL-6 and IL-6 levels in critically ill patients with Covid-19-associated pneumonia. J Infect. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2022.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellinghaus D., et al. Genomewide association study of severe Covid-19 with respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(16):1522–1534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2020283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jansson A.M., et al. Soluble CXCL16 predicts long-term mortality in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2009;119(25):3181–3188. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.806877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schranz D., et al. Fatty acid-binding protein 3 and CXC-chemokine ligand 16 are associated with unfavorable outcome in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021;30(11) doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2021.106068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villar J., et al. Clinical and biological markers for predicting ARDS and outcome in septic patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):22702. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02100-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turgunova L., et al. Association of biomarker level with cardiovascular events: results of a 4-year follow-up study. Cardiol Res Pract. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/8020674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liao M., et al. Single-cell landscape of bronchoalveolar immune cells in patients with Covid-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(6):842–844. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0901-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delorey T.M., et al. Covid-19 tissue atlases reveal SARS-CoV-2 pathology and cellular targets. Nature. 2021;595(7865):107–113. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03570-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smieszek S.P., et al. Elevated plasma levels of CXCL16 in severe Covid-19 patients. Cytokine. 2022;152 doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2022.155810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.