Significance

Super-enhancers (SEs) hold stronger power than regular enhancers to direct gene expression in the regulation of stem cell pluripotency. To dissect how pluripotency-associated SEs have evolved in mammals, we performed a systematic comparison of SEs among pigs, humans, and mice. Our analysis allowed the identification of three pluripotency-associated SEs (SE-SOX2, SE-PIM1, and SE-FGFR1) that are conserved in Placentalia (accounting for 94% of mammals) as well as many species-specific SEs. All three SEs were sufficient to direct pluripotency-dependent gene expression, and disruption of each conserved SE caused the loss of stem cell pluripotency. Our work highlights a small number of conserved SEs essential for the maintenance of pluripotency.

Keywords: pluripotency, super-enhancer, evolution, pigs, BRD4

Abstract

Despite pluripotent stem cells sharing key transcription factors, their maintenance involves distinct genetic inputs. Emerging evidence suggests that super-enhancers (SEs) can function as master regulatory hubs to control cell identity and pluripotency in humans and mice. However, whether pluripotency-associated SEs share an evolutionary origin in mammals remains elusive. Here, we performed comprehensive comparative epigenomic and transcription factor binding analyses among pigs, humans, and mice to identify pluripotency-associated SEs. Like typical enhancers, SEs displayed rapid evolution in mammals. We showed that BRD4 is an essential and conserved activator for mammalian pluripotency-associated SEs. Comparative motif enrichment analysis revealed 30 shared transcription factor binding motifs among the three species. The majority of transcriptional factors that bind to identified motifs are known regulators associated with pluripotency. Further, we discovered three pluripotency-associated SEs (SE-SOX2, SE-PIM1, and SE-FGFR1) that displayed remarkable conservation in placental mammals and were sufficient to drive reporter gene expression in a pluripotency-dependent manner. Disruption of these conserved SEs through the CRISPR-Cas9 approach severely impaired stem cell pluripotency. Our study provides insights into the understanding of conserved regulatory mechanisms underlying the maintenance of pluripotency as well as species-specific modulation of the pluripotency-associated regulatory networks in mammals.

The developmental potential of interspecific chimeras established from pluripotent stem cells (PSCs) indicates the presence of conserved regulatory mechanisms controlling proliferation and differentiation during development (1, 2). Mammalian PSCs share key transcription factors and can be induced from adult somatic cells through the forced expression of OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-Myc to activate pluripotency-associated genes (3–5). However, PSCs derived from different species require distinct external signals, suggesting a regulatory discrepancy in maintaining pluripotency among different species (6, 7). For instance, MEK-ERK inhibitors (such as PD-0325901) have an opposing effect on boosting pig (Sus scrofa) and mouse pluripotency (8). How the regulatory landscape responsible for the maintenance of stem cell pluripotency has evolved in mammals is still unclear.

Enhancers or cis-regulatory elements play key roles in controlling spatial and temporal expression of genes essential for many biological processes (9). Emerging evidence suggests that groups of enhancers with unusually strong enrichment for the binding of transcriptional coactivators may accumulate at certain regions of animal genomes to form super-enhancers (SEs) (10). Compared with typical enhancers (TEs), SEs are characterized by high levels of histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac) density with an enormous size (11, 12). Such SEs can function as master regulatory hubs to determine cell identity and developmental and disease states in a broad range of human and mouse cell types (13–15). Previous studies have shown that SEs in mouse PSCs are densely occupied by master pluripotency-related transcription factors, and reduced expression in OCT4 or mediators led to preferential loss of expression of SE-associated genes relative to other genes (16). Deletion of the SEs associated with NANOG or SOX2 in mice blocked their corresponding gene expression and caused a failure in the maintenance of pluripotency (17–20).

Since the majority of studies on mammalian pluripotency were conducted in humans and mice (21–23), whether pluripotency-associated SEs share an evolutionary origin in mammals is still an open question in the field (24, 25). To address this question, we extended our research to pigs that are distantly related to humans and mice. Pigs have been used as a critical model for numerous human conditions and diseases including xenotransplantation due to the similarity in organ anatomy, physiology, and metabolism (26, 27). For instance, genome-edited pigs were reported to better recapitulate the features of neurodegenerative diseases than similarly modified mice models were (28). Recently, several porcine PSC lines derived from preimplantation embryos or established through induced PSC technology showed the ability to differentiate into the three germ layers (29, 30). These PSC lines provide a unique opportunity for investigating the evolution of SEs associated with pluripotency in mammals. In this study, we performed systematic identification of SEs in porcine PSCs using multiomics. Our cross-species comparative epigenomic analysis revealed three SEs conserved within placental mammals essential for the maintenance of stem cell pluripotency.

Results

Systematic Identification of SEs Associated with Porcine PSCs.

Reprogramming of porcine somatic cells by doxycycline-induced expression of four transcriptional factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-Myc) is an efficient approach to produce porcine PSCs (8, 31, 32). Using this system, we established a porcine pluripotent cell line possessing the ability to produce xenochimerism with mouse early embryos (33) (Fig. 1 A and B). Changes in culture condition are sufficient to drive these porcine PSCs to switch rapidly between a pluripotent state and a differentiation state, as indicated by alkaline phosphatase (AP) staining and the expression levels of pluripotent genes (Fig. 1 C and D and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and B). Therefore, we chose this cell line for the identification and characterization of SEs in this study.

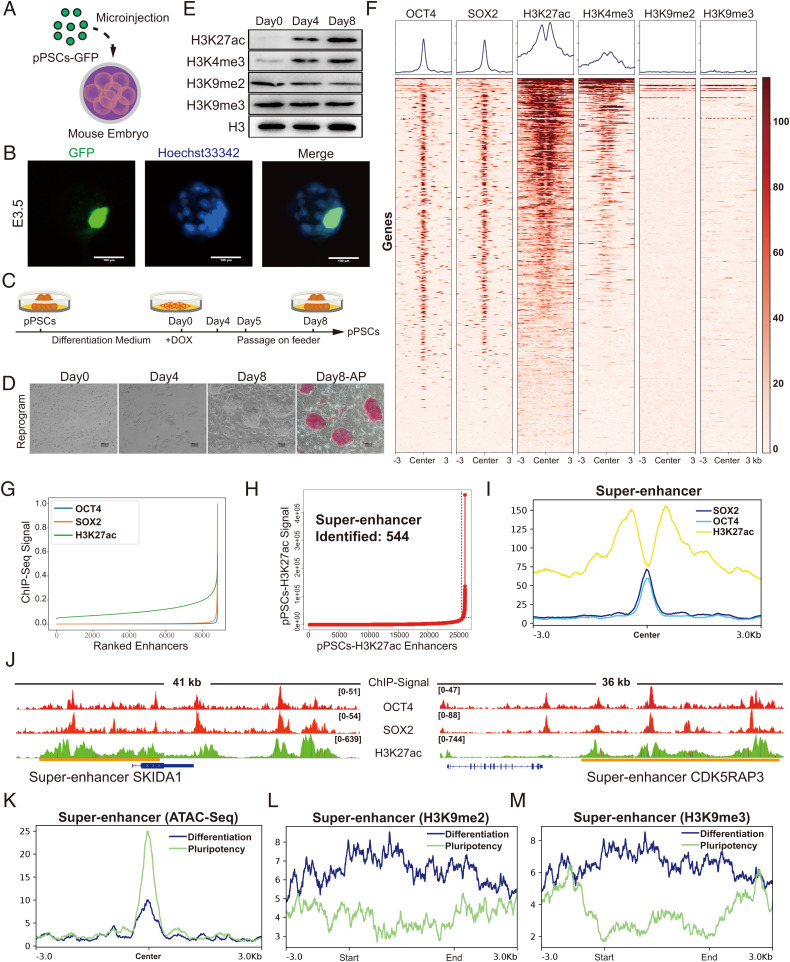

Fig. 1.

Systematic identification of SEs in porcine PSCs. (A) Schematic of the generation of pig-mouse ex vivo chimeric embryos. (B) Representative images of porcine PSC-injected mouse embryos cultured in vitro at E3.5. The nuclei were marked by Hoechst33342, and the location of the injected porcine PSCs was marked with GFP. Scale bar, 100 µm. (C and D) Strategies for switching porcine PSCs between pluripotent state and differentiation state by changing the culture condition. Under the reprogramming culture condition, differentiated porcine PSCs transformed to the pluripotent state (referred to as secondary reprogramming). Scale bar, 100 µm. (E) Western blot analysis of representative histone modifications during secondary reprogramming. (F) Heatmaps of OCT4, SOX2, H3K27ac, H3K4me3, H3K9me2, and H3K9me3 surrounding the OCT4 binding loci. (G) Distribution of H3K27ac, OCT4, and SOX2 normalized ChIP-seq signals. Each ChIP-seq data point was normalized by dividing the ChIP-seq signals by the maximum signals individually and was sorted in ascending order. (H) Identification of SEs in porcine PSCs. Within the 12.5-kb window, H3K27ac signals were ranked for porcine PSCs. The enhancers above the inflection point were defined as original SEs. (I) Average ChIP-seq signal density of OCT4, SOX2, and H3K27ac surrounding the center of the SE regions. (J) ChIP-seq signal profiles of OCT4, SOX2, and H3K27ac in porcine PSCs at two representative top-ranked SE loci. Gene models are shown below the binding profiles. The positions of SEs are marked by orange lines. (K) Average ATAC-seq signal density in the pluripotent state and differentiation state of porcine PSCs surrounding the SE regions. (L and M) Average ChIP-seq signal density of H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 in pluripotent and differentiation states of porcine PSCs surrounding the SE regions. DOX, doxycycline. pPSC, porcine pluripotent stem cell. E3.5, embryonic day 3.5.

H3K27ac histone modification, combined with others such as H3K4me3 (which marks active promoters), has been frequently used as a marker for the identification of active TEs and SEs (34–36). Previously, SEs associated with stem cells were defined by the presence of sites bound by master regulators (such as OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG) and by the potential to span large genomic regions, with an average size generally an order of magnitude larger than that of TEs (14, 16, 37). Upon the establishment of pluripotency in PSCs, the levels of total H3K27ac and H3K4me3 histone modification increased dramatically (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 C–J). In contrast, the repressive histone marks H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 displayed a slight but statistically significant reduction (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Fig. S1C). To identify SEs associated with porcine PSCs, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) including histone ChIP-seq (H3K27ac, H3K4me3, H3K9me2, and H3K9me3) and transcription factor ChIP-seq (OCT4 and SOX2). Our results showed that 2,159 out of 3,337 OCT4- and SOX2-regulated genes displayed H3K27ac enrichment (Fig. 1F and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 K and L). Consistent with previously reported observations in humans and mice, OCT4- and SOX2-enriched peaks overlapped well with H3K27ac-defined enhancers in pigs (Fig. 1G). Next, SEs associated with porcine PSCs were identified by concatenated H3K27ac-marked regions (absent for H3K4me3 signals), the presence of OCT4 and SOX2 ChIP signals, and a minimum size of 5.8 kb (38) (Fig. 1 H and I and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). For instance, we found there were two top-ranked SEs associated with SKI/DACH Domain Containing 1 (SKIDA1) and CDK5 Regulatory Subunit Associated Protein 3 (CDK5RAP3) (Fig. 1J). The latter has been reported to be essential for the survival of human PSCs (39). Gene Ontology (GO) term analysis suggested that the identified SE-associated genes are associated with embryo development and signaling pathways regulating the pluripotency of stem cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1M). To further confirm that the identified SEs are indeed associated with pluripotency, we conducted assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with high-throughput sequencing (ATAC-seq) to monitor chromatin accessibility in SE regions in both the pluripotent state and the differentiation state. We found that SE regions were open in the pluripotent state but exhibited a dramatic reduction in chromatin accessibility during the differentiation of porcine PSCs (Fig. 1K). Consistently, SE regions were strongly marked by repressive histone marks H3K9me2 and H3K9me3 in the differentiation state but displayed relatively weak signals in the pluripotent state (Fig. 1 L and M). Taken together, our data show that the SEs we identified in porcine PSCs are closely associated with pluripotency.

BRD4 Is an Essential Activator for Mammalian Pluripotency-Associated SEs.

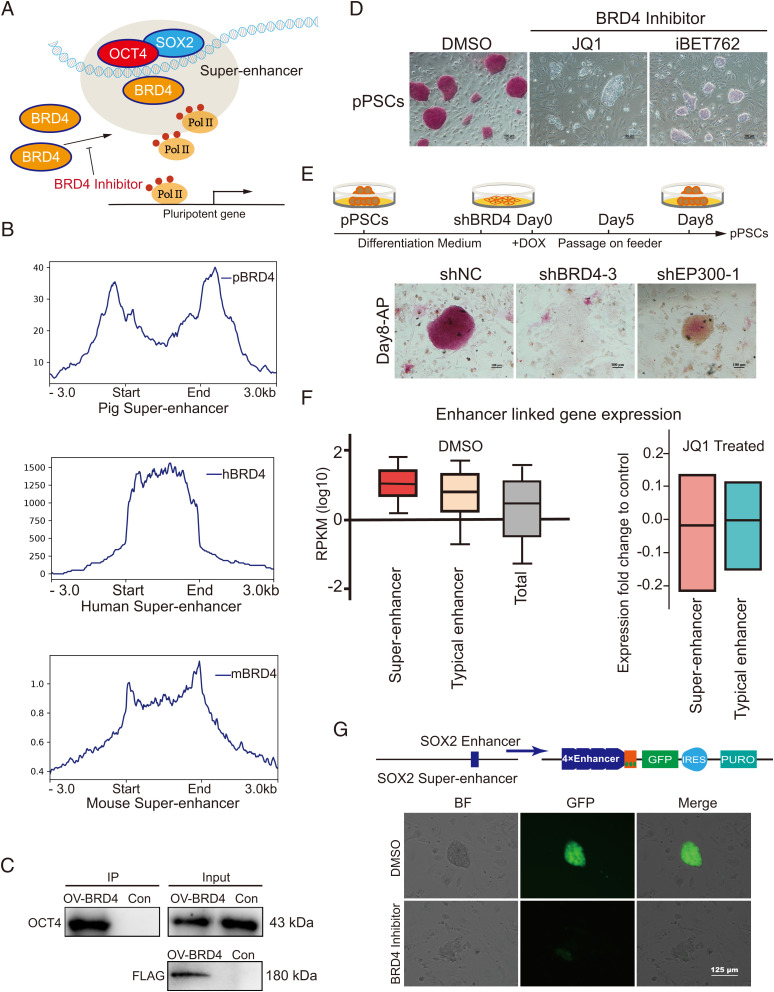

BRD4, a highly conserved (>84% sequence identity between humans and basal mammals) chromatin reader protein that recognizes and binds acetylated histones (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), directly interacts with OCT4 and SOX2 to activate pluripotency-related genes in mice (40–42) (Fig. 2A). To investigate whether this regulatory mechanism is common in mammalian PSCs, we performed BRD4 ChIP-seq and compared the BRD4 enrichment in SEs identified from pigs, humans, and mice. We observed a consistent enrichment of BRD4 binding in SEs identified from all three species (Fig. 2B). Coimmunoprecipitation experiments supported that the direct interaction between BRD4 and OCT4 was also present in porcine PSCs (Fig. 2C). To further explore the function of BRD4 in porcine PSCs, we attempted to establish a BRD4-knockout cell line using the CRISPR-Cas9 approach. A green fluorescent protein (GFP)–STOP cassette was introduced to produce a BRD4 mutant allele, while another red fluorescent protein (RFP)-STOP cassette was used to destroy the second allele to produce BRD4 homozygous knockout cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A–E). However, no GFP/RFP double-positive cell was obtained, providing direct evidence for the necessity of BRD4 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4F). Therefore, we switched to BRD4 inhibitors and RNA interference (RNAi). We found that BRD4 inhibition through drug treatment (JQ1 and iBET762) led to rapid differentiation of porcine PSCs (Fig. 2D), as revealed by the incorporation of 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU) assay and cell growth curves (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A–D). Similarly, BRD4 knockdown blocked the establishment of porcine PSCs, resulting in a failure in the formation of typical porcine PSC colonies (Fig. 2E and SI Appendix, Fig. S4G). Additionally, the phenotype of BRD4 knockdown seems to be more robust compared with the knockdown of E1A-binding protein P300 (an important histone acetylase that is extensively involved in SE-associated transcriptional regulation) (Fig. 2E and SI Appendix, Fig. S4H).

Fig. 2.

BRD4 is an essential activator for mammalian pluripotency-associated SEs. (A) Model showing pluripotency-associated SEs working, relying on the enrichment of BRD4 in human and mouse PSCs. (B) Average ChIP-seq signal density of BRD4 in pigs, humans, and mice surrounding the pluripotency-associated SE regions. (C) The interaction of BRD4 and OCT4 in porcine PSCs. FLAG-tagged BRD4 was revealed by Western blot using the anti-Flag antibody. We used the anti-OCT4 antibody to test the protein interaction in porcine PSCs. (D) AP staining assay of porcine PSCs treated with iBET762, JQ1, and DMSO. Porcine PSCs lost their pluripotency after BRD4 inhibitor (iBET762 and JQ1) treatment. Scale bar, 100 µm. (E) The strategy for reprogramming BRD4-inhibited porcine cells. The top part is the schematic to reprogram the differentiated PSCs with BRD4 interference. The AP staining assay for cells carrying different shRNAs after 8 d of reprogramming is shown at the bottom. (F) Box plots of expression (reads per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads; RPKMs) from enhancer-linked genes and all expressed genes. Genes linked to SEs have relatively high expression levels, and inhibition of BRD4 leads to a slightly greater reduction in the expression of SE-linked genes compared with that of TE-linked genes. (G) GFP expression driven by the SOX2 enhancer in mouse PSCs. All images were based on the same exposure conditions. The BRD4 inhibitor reduced the activity of SEs. Scale bar, 125 µm. DOX, doxycycline. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; h, human; m, mouse; p, pig; shRNA, short hairpin RNA. pPSCs, porcine pluripotent stem cells. Pol II, RNA polymerase II. IP, immunoprecipitation. OV, overexpression. Con, wild-type pPSCs. shNC, an shRNA negative (control). shBRD4-3, an shRNA targeting BRD4. shEP300-1, an shRNA targeting EP300. IRES, internal ribosome entry site element. PURO, puromycin resistant. BF, bright field.

Then we wanted to ask if the phenotype we observed for BRD4 inhibition is correlated with a reduction in enhancer activities. Therefore, we performed a unique identifier transcriptome profiling of JQ1-treated porcine PSCs. We found that BRD4 inhibition led to the suppression of pluripotency-related signaling pathways (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 E and F). Notably, we observed that the expression of genes linked to SEs is more robust than that of TEs in porcine PSCs (Fig. 2F). Blocking BRD4 led to a slightly greater reduction in the expression of SE-linked genes compared with TE-linked genes (Fig. 2F). Next, we tested if BRD4 is essential for the activation of SEs in pigs. Using the SE associated with SOX2 (a known regulator of pluripotency) as an example, we found that inhibition of BRD4 blocked cell pluripotency and activation of SOX2 SE in a reporter assay (43) (Fig. 2G). In summary, our data suggest BRD4 is a highly conserved regulator essential for the activation of SEs in mammals.

Pluripotency-Associated Transcription Factor Binding Motifs Are Enriched in SEs.

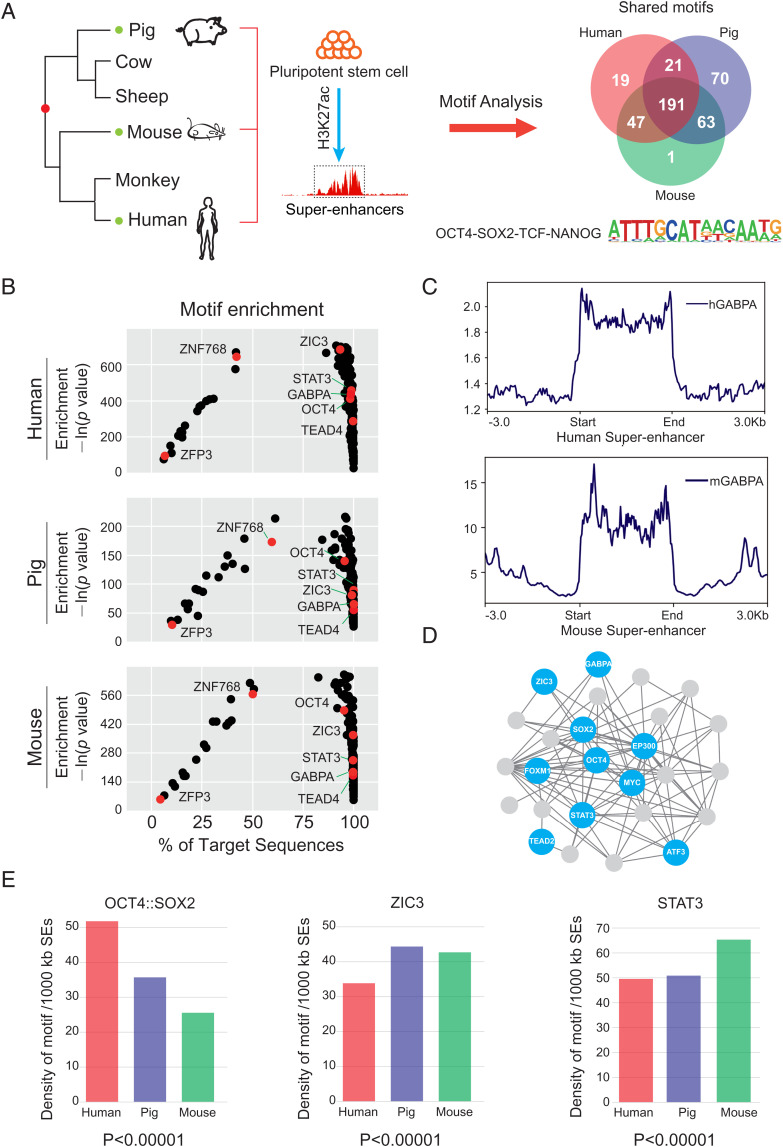

We next explored the motif enrichment of pluripotency-associated SEs in pigs, mice, and humans. Our analysis revealed 278 significantly enriched transcription factor binding motifs for human SEs, 345 for pigs, and 302 for mice (Fig. 3A). Among these predicted transcription factors, 191 were shared in all three species (Fig. 3B). Combined with the transcriptome data of human, pig, and mouse PSCs, we identified 30 shared pluripotency-related transcription factors with relatively high abundance. To test whether these predicated transcription factors indeed bind to SEs, we took GABPA as an example and examined its binding regions in genomes of human and mouse PSCs using previously published ChIP-seq datasets (44, 45). As expected, we observed significant enrichment of GABPA occupation in SE regions in both humans and mice (Fig. 3C). Protein–protein interaction analysis using Cytoscape revealed that complex interactions are likely to present among these 30 transcription factors (Fig. 3D and SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A and B).

Fig. 3.

Pluripotency-associated transcription factor binding motifs are enriched in SEs. (A) The evolution relationship between humans, pigs, and mice. SE sequences from the three species were extracted for motif analysis. (B) The distribution of the 191 overlapped motifs identified in human (top), pig (middle), and mouse (bottom) pluripotency-associated SEs. Representative pluripotency-associated factors are marked in red. (C) Average ChIP-seq signal density of GABPA in humans and mice pluripotency-associated SEs. GABPA is enriched in SE regions. (D) Protein interaction networks of representative transcription factors in pigs. Factors with relatively high expression levels are marked in blue. (E) The average numbers of the OCT4::SOX2 motif, the ZIC3 motif, and the STAT3 motif per 1,000-kb SEs. h, human; m, mouse.

Furthermore, the genome-wide distribution of the representative motifs (e.g., OCT4::SOX2, ZIC3, and STAT3) was compared among pigs, mice, and humans. We observed a large variation of the relative density of each binding motif in different species (Fig. 3E and SI Appendix, Fig. S6C). For example, the density of the OCT4::SOX2 motif in human SEs was about two times higher than that of mice. To overcome the bias caused by species-specific modulation of motifs, we also calculated the motif distribution with human- and mouse-specific motif sequences and observed consistent trends in the tested species (SI Appendix, Fig. S6D). Taken together, our data indicate conserved transcription factor binding motifs are present but not evenly distributed in mammalian SEs associated with stem cell pluripotency, which may explain the diversity in the regulatory landscape of pluripotency.

Identification of Conserved Pluripotency-Associated SEs.

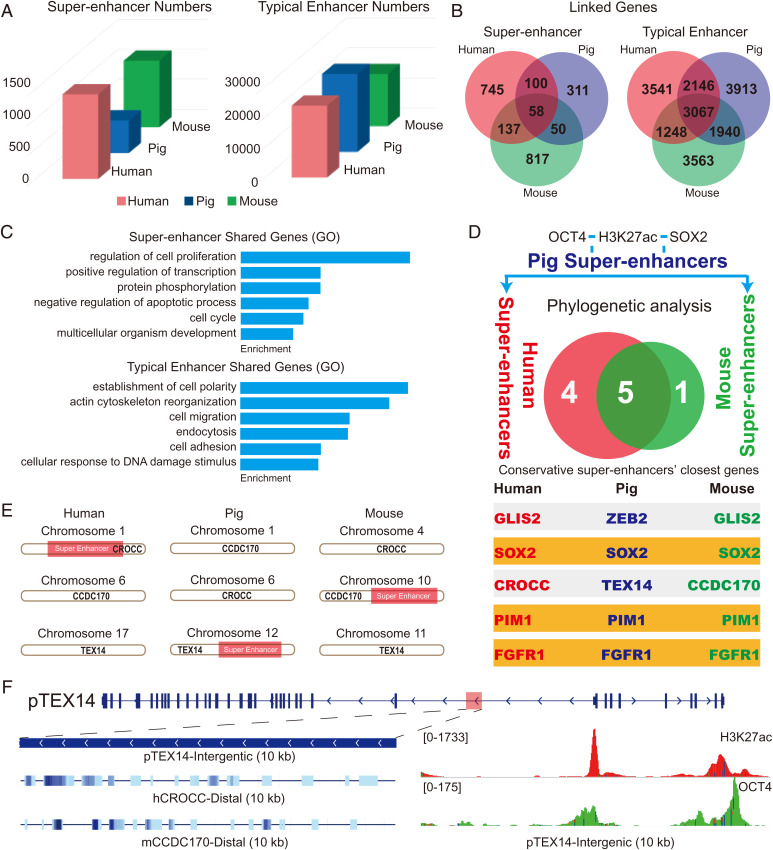

Unlike protein-coding genes, enhancers or cis-regulatory elements usually exhibit weak DNA sequence conservation and undergo rapid evolution in mammals (46, 47). Nevertheless, certain ancient groups of highly conserved enhancers have been identified in vertebrate development (48, 49). For instance, a limb-specific enhancer of Sonic hedgehog, the zone of polarizing activity regulatory sequence, is highly conserved in many vertebrate species (50). Genomic substitution of the mouse enhancer with its snake orthologs caused severe limb reduction, suggesting that highly conserved enhancers are functionally significant. To determine whether conserved pluripotency-associated SEs are present in mammals, we compared the distribution and conservation of pluripotency-associated SEs and TEs in the three distantly related mammals. Our results unveiled 1,409 SEs and 23,797 TEs in humans; 1,108 SEs and 17,277 TEs in mice; and 544 SEs and 25,786 TEs in pigs (Fig. 4A). To understand the functions of identified enhancers, we combined transcriptome data, H3K4me3 (which marks active promoters) ChIP-seq data, and Hi-C data (51, 52) to link enhancers to their potential target genes (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 and details in Materials and Methods). We identified 3,067 shared TE-linked genes (about 27.7% of porcine TE–linked genes) and 58 shared (about 11.2% of total porcine SE–linked genes) SE-linked genes in all three species (Fig. 4B). GO term analysis indicated that the top GO term associated with shared SE-linked genes and TE-linked genes was regulation of cell proliferation and establishment of cell polarity, respectively (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

The rapid evolution of pluripotency-associated SEs in mammals. (A) Numbers of human, pig, and mouse pluripotency-associated SEs and TEs. (B) SE- and TE-linked genes of humans (red), pigs (blue), and mice (green). (C) GO analysis of the shared enhancer-linked genes in three species. (D) Phylogenetic analysis of the SE sequences of humans, pigs, and mice. The H3K27ac, OCT4, and SOX2 ChIP-defined SEs in porcine PSCs were identified and subjected to conservation analysis in the genomes of humans and mice. The SE-linked genes are listed. (E and F) Characteristics of the SE linked to the gene TEX14 (SE-TEX14) in pigs. SE-TEX14 shows different proximal genes in humans and mice and displays high OCT4 occupation. h, human; m, mouse; p, pig.

Next, we selected H3K27ac, OCT4, and SOX2 ChIP-defined SEs in porcine PSCs and then subjected them to conservation analysis in the genomes of humans and mice using PhastCons. There were nine SEs with PhastCons scores larger than 0.4 between humans and pigs and six between pigs and mice. Only five (ZEB2, SOX2, TEX14, PIM1, and FGFR1) conserved SEs were mapped across the three species, yet two (ZEB2 and TEX14) of them displayed discrepant proximal genes (Fig. 4D). For example, the SE linked to the gene TEX14 in pigs (SE-TEX14) is proximal to CROCC in humans and CCDC170 in mice (Fig. 4 E and F). Importantly, systematic evaluation of the conservation score for SE-SOX2, SE-PIM1, and SE-FGFR1 using University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) whole-genome alignment data (241 species) indicated that these three SEs are highly conserved in an infraclass of Mammalia, Placentalia (accounting for 94% of mammal species) (53, 54) (SI Appendix, Figs. S8–S10). In contrast, no or small conserved regions of the three SEs were detectable in more basal mammals (such as opossum and platypus), which may be due to the large phylogenetic distance or may suggest they were newly evolved in Placentalia. The conservation of these SEs seems to be correlated with the involvement of their target genes during early embryogenesis in humans, pigs, and mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). Altogether, our data suggest that three evolutionarily conserved SEs are present in the genomes of placental mammals.

Activation of Conserved SEs Correlates with Pluripotency.

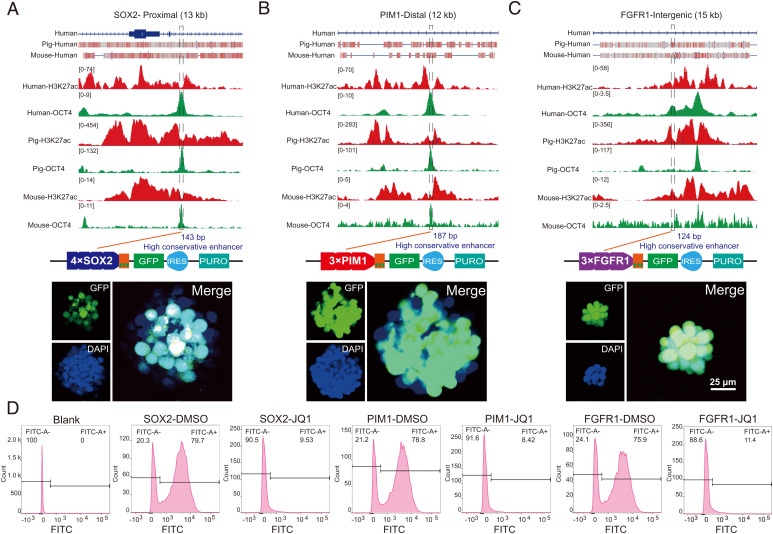

We next investigated whether the activation of SE-SOX2, SE-PIM1, and SE-FGFR1 is correlated with stem cell pluripotency. Given that SEs are large in size, we asked if core subregions that play a dominant role are present in the identified SEs (55). As expected, 143-bp, 187-bp, and 124-bp subregions were identified for SE-SOX2, SE-PIM1, and SE-FGFR1, respectively, with much higher conservation scores and OCT4 occupation than the rest of the regions of each SE (Fig. 5 A–C and SI Appendix, Fig. S12). We then performed lentivirus-based reporter assays in porcine PSCs by cloning all three subregions into a GFP reporter vector with a basal promoter, which alone is not sufficient to drive reporter expression (43). The expression of GFP relies on the regulatory activities of tested DNA fragments. To enhance reporter expression, we utilized multiple tandem duplications of each core region as previously described (43). Upon lentivirus infection, we observed robust activation of GFP for all enhancers in porcine PSCs, but not in somatic cells without pluripotency (SI Appendix, Fig. S13). Similarly, consistent results were also observed in mouse PSCs (SI Appendix, Fig. S14A), suggesting that the three subregions contain pluripotency-dependent enhancer activities. To explore whether the main function of these conserved SEs is pluripotent relevant, we then subjected the PSC lines carrying SE-directed reporters to embryoid body (EB) formation. This assay allows PSCs to differentiate into various cell types involved in all three embryonic germ layers. As expected, at 7 d after differentiation, we observed a dramatic reduction in SE activation as reflected by the inactivation of GFP expression in more than 80% of EB-derived cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). Because BRD4 is an essential activator for pluripotency-associated SEs, we tested if the three conserved subregions respond to BRD4 inhibition. After 48 h of 0.25 µM BRD4 inhibitor treatment, the intensity of GFP expression was reduced dramatically (SI Appendix, Fig. S14B), followed by the disappearance of GFP-positive cells at 72 h after treatment (Fig. 5D). We concluded that the three conserved subregions of each SE contained enhancer activities sufficient to activate pluripotency-dependent gene expression.

Fig. 5.

Activation of conserved SEs correlates with pluripotency. (A–C) Characteristics of the three conserved SEs. The top part is the gene models of the SEs in the human genome, and the conserved regions across species are marked by red rectangles. The middle part is the distribution of histone H3K27ac and OCT4 ChIP-seq signals in the selected SEs. The conserved subregions we identified are marked by dotted boxes. The bottom part shows the results of our reporter assay. The three conserved subregions are sufficient to drive reporter expression. The nuclei are marked by Hoechst33342. Scale bar, 25 µm. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of GFP expression in murine PSCs. BRD4 inhibitor reduced the activity of SE conserved subregions. The abscissa represents the GFP fluorescence intensity, and the ordinate represents the number of cells with certain GFP fluorescence intensity. The Blank group represents wild-type mouse PSCs. Cells were divided into two groups according to the GFP expression. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide. IRES, internal ribosome entry site element. PURO, puromycin resistant. FITC, fluorescein Isothiocyanate (GFP fluorescence intensity).

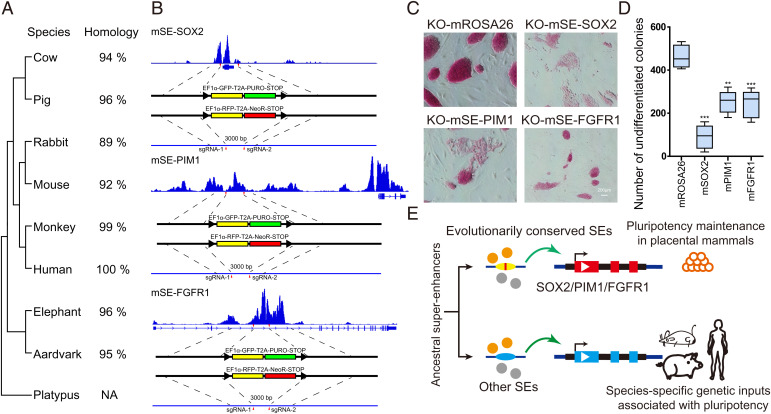

Conserved SEs Are Essential for the Maintenance of Pluripotency.

The remarkable conservation of three identified SEs in mammals indicates potential roles in controlling stem cell pluripotency (Fig. 6A and SI Appendix, Figs. S8–S10). To test the function of SEs, we generated SE-disrupted mouse PSCs for SE-SOX2, SE-PIM1, and SE-FGFR1 with a CRISPR-Cas9 approach by replacing each enhancer with GFP- and RFP-STOP cassettes (Fig. 6B and SI Appendix, Fig. S16 A and B). As expected, we observed a significant reduction in the expression of SE-linked genes and pluripotent marker genes in mutant clones (SI Appendix, Fig. S16C). SE-disrupted PSCs exhibited a dramatic loss of pluripotency, spontaneous differentiation, and decreased proliferative potential, resulting in a reduced number of undifferentiated colonies and decreased EdU incorporation compared with the control (mROSA26-locus edited) (Fig. 6 C and D and SI Appendix, Fig. S16D). Similarly, we observed an impaired ability to form embryoid bodies for SE-disrupted PSCs, which further supports the loss of pluripotency due to the SE deficiency (SI Appendix, Fig. S16E). Consistent results were also observed in porcine PSCs upon the deletion of each SE using a lentivirus system expressing single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) (SI Appendix, Fig. S17). To further verify that the reduction of SE-linked gene expression in mutant clones is caused by enhancer disruption rather than a change in differentiated cell state, we decided to carry out a conditional deletion using the Cre-loxP system. We inserted two loxP sites on either side of the SE-FGFR1 core subregion and knocked in a tamoxifen-inducible Cre-activation cassette at the mROSA26 locus via homologous recombination (SI Appendix, Fig. S18 A and B). The gradual decrease of FGFR1 expression upon tamoxifen treatment at 48 and 96 h confirmed the SE-dependent activation of target gene expression (SI Appendix, Fig. S18 C and D).

Fig. 6.

The three conserved SEs are essential for pluripotency. (A) The evolutionary tree of the three SE conserved subregions among nine representative mammals. Their sequence identities to humans are listed on the right. (B) The strategy to disrupt the three conserved SEs in murine PSCs by CRISPR-Cas9. (C) AP staining assay of murine PSCs with SE disruption. Murine PSCs lost their pluripotency when the three conserved SEs were destroyed. The editing of the murine ROSA26 locus was used as the control. Scale bar, 200 µm. (D) Numbers of undifferentiated AP-positive colonies under different editing treatments. n = 5 independent experiments (**P <0 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (E) The model of ancestral SE evolution in mammalian pluripotency maintenance. We propose that evolutionarily conserved SEs are critical in maintaining mammalian pluripotency, and other SEs may contribute to the species-specific genetic inputs associated with pluripotency. m, mouse. NA, not available. PURO, puromycin resistant. NeoR, neomycin resistant.

Next, we asked whether the conserved subregions and nonconserved subregions of SEs contribute equally to the maintenance of pluripotency. We selected a nonconserved region of SE-FGFR1 and subjected it to CRISPR-Cas9–mediated deletion in mice PSCs (SI Appendix, Fig. S18E). In contrast to conserved subregions, deletion of the nonconserved region failed to produce an obvious effect on the expression of FGFR1 and stem cell pluripotency as revealed by AP staining and cell morphology (SI Appendix, Fig. S18 F and G). Our results suggest that the conserved regions seem to be more important for pluripotency.

To determine whether nonconserved (species-specific) SEs also contribute to the maintenance of stem cell pluripotency, we selected a mouse-specific SE associated with the Jam2 gene as an example (SI Appendix, Fig. S19 A and B). We performed lentivirus-based reporter assays for SE-JAM2 and observed a similar ability to activate reporter expression in murine PSCs compared with the three conserved SEs (SI Appendix, Fig. S20). Interestingly, SE-JAM2 deletion led to a significant reduction of Jam2 gene expression but had no impact on stem cell pluripotency (SI Appendix, Fig. S19 C–F). In addition, we observed no changes in the expression of pluripotent factors such as SOX2 upon the deletion of SE-JAM2, which further suggests that SE-JAM2 is not involved in the maintenance of pluripotency (SI Appendix, Fig. S19 E and F). Taken together, our data indicate that evolutionarily conserved SEs are essential for maintaining stem cell pluripotency and that conserved subregions of each SE are likely to be more important than nonconserved subregions.

Discussion

In this study, we applied comprehensive genomic and epigenomic approaches to compare pluripotency-associated SEs in pigs, mice, and humans. Although most SEs have undergone rapid changes in DNA sequence and rearrangements during mammalian evolution, we identified three evolutionarily conserved SEs linked to SOX2, PIM1, and FGFR1. The remarkable conservation of these SEs seems to be consistent with the critical roles that SE-linked genes play during development and in the maintenance of pluripotency. SOX2, PIM1, and FGFR1 are activated during early embryogenesis in humans, pigs, and mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). Further, SOX2 and FGFR1 are well-known regulators required for maintaining stem cell pluripotency (56–60). Deletion of SOX2 resulted in the trophectodermal differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs) (61). The expression of FGFR1 is required for the formation of prime state mouse ESCs (62), and blocking FGFR1 reduces the proliferation of human ESCs (63).

Despite PIM1 knockout mice being homozygous viable (64), inhibition of PIM1 with RNAi led to extensive differentiation of mouse ESCs after 9 d of transfection (65). In contrast, overexpression of PIM1 improved the reprogramming efficiency of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (66). It has been suggested that PIM1 plays a critical role in maintaining the telomere lengths of mouse cardiomyocytes (67). We speculated that the expression of PIM1 may facilitate the proliferative potential of stem cells by regulating the length of the telomere. Besides, PIM1 can promote cell survival rate by activating the anti-apoptotic factor BCL2 (68, 69). Stem cells with high PIM1 expression levels may overcome stage-related compatibility barriers to effectively form interspecies chimeras (33, 70). Further research is needed to elucidate the function of PIM1 in maintaining pluripotency.

The essential roles of SE-SOX2, SE-PIM1, and SE-FGFR1 have allowed us to propose that evolutionarily conserved SEs are critical to maintaining stem cell pluripotency in mammals, while the rearrangement of certain SEs in different species may contribute to variation in genetic inputs involved in regulating stem cell proliferation and differentiation. The SEs can be divided into subregions with various functions (71, 72). Several studies have reported that at least a subset of subregions is required for proper SE function, despite some subregions being redundant (17, 39, 55). Additionally, during the naive-to-primed pluripotency transition of mouse PSCs, subregions within SEs displayed pronounced differences in the dynamics of CpG methylation (73). Combined with our findings, the nonconserved domains of SEs create the possibility for evolving species-specific and lineage-specific modulation of target genes involved in pluripotency. Taken together, our study findings highlight the rapid evolution of SEs and indicate that certain essential pluripotency-associated SEs share an evolutionary origin in placental mammals. The species-specific and rearranged SEs may contribute to distinct genetic inputs involved in the regulation of PSCs in different species (Fig. 6E).

Materials and Methods

Ethics Declarations.

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Center of Northwest A&F University and were performed in strict accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China, Policy No. 2006398).

Generation of Cell Lines with Genomic Editing.

The generation of the Cre-loxP–mediated SE-FGFR1 conditional enhancer-deletion (3,000 bp) cell line was carried out in two steps. First, the sgRNA-expressing vector targeting the mROSA26 locus and the donor vector containing 1,500- to 2,500-bp homology arms and tamoxifen-induced Cre-expression cassettes (MerCreMer) were transfected into stem cells. For electric transfection, 3 × 106 cells in 250 μL electroporation buffer containing 15 μg plasmids were treated with 300 V for 1 ms in a 2-mm gap by BTX-ECM 830 (BTX). After 12 h, cells were washed and further incubated in the fresh medium. Further, cells were screened by 300 µg/mL G418 (Gibco) for 3 d. Second, the cassette (loxP-enhancer-loxP) was introduced into the PSCs through the same strategy (transfecting one donor vector and two sgRNA-expressing vectors targeting both sides of the SE-FGFR1 core subregion). After 72 h, limiting dilution was performed, and incubation was continued for 6 to 8 d. Individual colonies were picked, and genomic DNA was extracted for genotyping. Gene editing–positive colonies were expanded for further investigation (74, 75). Tamoxifen (1 μM final concentration) was purchased from MedChem Express. Details on generation of other cell lines with enhancer deficiency can be found in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Identification of SEs.

The H3K27ac-defined SEs in human and mice PSCs were obtained from previously published research (76). The identification of H3K27ac-defined SEs in porcine PSCs was performed in four steps. First, the original SEs were identified by ROSE in porcine PSCs according to the published protocol (13, 16). The total numbers of mapped H3K27ac ChIP-seq reads per million reads were calculated and normalized by the length of each enhancer. The enhancers above the inflection point were defined as original SEs. Second, we kept SEs identified in the first step with OCT4 and SOX2 ChIP signals. Third, SEs were assessed for absence of H3K4me3 (which marks active promoters), H3K9me3, and H3K9me2 signals in porcine PSCs. Fourth, the SE regions were monitored for accessibility using high ATAC-seq signals. The final list of porcine pluripotency-associated SEs is provided in SI Appendix, Table S7.

In this study, we assigned the ChIP-defined SEs to their neighboring genes, allowing a maximal distance of 100 kb between the SE and the target transcription start site (TSS), in combination with transcriptome data, H3K4me3 (which marks active promoters) ChIP-seq data, and available Hi-C data from pigs, mice, and humans (51, 52). As an SE-linked gene, the gene should be actively transcribed, should have an active H3K4me3-defined promoter, and should share the same topological associated domains (TAD) as its corresponding SE. The chromosome conformation was analyzed by HiCExplorer (77).

SE Conservation Analysis.

The conservation of SEs was determined in three steps. First, we identified H3K27ac, OCT4, and SOX2 ChIP-defined SEs in porcine PSCs. The overlapped SEs shared by all three ChIP datasets were picked as stem cell pluripotency–associated SEs. Second, we subjected these pluripotency-associated SEs to conservation analysis in the genomes of humans and mice using PhastCons (78). As a result, we found five SEs that were conserved among pigs, mice, and humans with a conservation score of more than 0.4. Third, according to the precomputed whole-genome alignment data (the Vertebrate Multiz Alignment & Conservation-100 Species and Cactus Alignment & Conservation of Zoonomia Placental Mammals 241 Species) (53, 54, 79), only three of them (SE-SOX2, SE-PIM1, and SE-FGFR1) displayed shared synteny in placental mammals, suggesting that each SE may be derived from a common ancestor and should be critical. Therefore, we selected these three SEs for further functional validation. The source data used to perform the sequence alignment was downloaded from the UCSC (http://genome.ucsc.edu/). The evolutionary trees were measured by MEGA X (80).

Details of cell culture conditions, plasmids, interspecific chimeric embryo formation assay, AP staining, Western blot, immunofluorescence staining, coimmunoprecipitation, cell proliferation assay, flow cytometry, digital RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq, and motif enrichment analysis are provided in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (32072806 and 62072377), the China National Basic Research Program (2016YFA0100203), the Program of Shaanxi Province Science and Technology Innovation Team (2019TD-036), Program of Shaanxi Province Science and Technology (2022NY-044), Program of Shaanxi Province for Demonstration of key technologies of animal husbandry. Wei Wang was supported by the National Institute of Biological Sciences. We thank Seqhealth Technology Co., LTD for supplying sequencing services. We thank Prof. Jianyong Han (China Agricultural University) and Dr. Minglei Zhi (China Agricultural University) for the TAD boundary data of porcine PSCs.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. B.A. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2204716119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

H3K27ac, H3K4me3, and BRD4 ChIP-seq in porcine PSCs were performed in this study and uploaded to National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under the accession number PRJNA866208 (81). Previously published data were used for this work (i.e., H3K9me2, H3K9me3, OCT4, and SOX2 ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data in porcine PSCs have been uploaded to the National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI] Sequence Read Archive database under the accession No. PRJNA633419 by our laboratory) (82, 83). The H3K27ac ChIP-seq data of human PSCs was obtained from NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus accession No. GSM466732 (84). The H3K27ac ChIP-seq data of mouse PSCs was obtained from accession Nos. GSM594578 and GSM594579. The BRD4 ChIP-seq data of human PSCs was obtained from accession No. GSM1466835. The BRD4 ChIP-seq data of mouse PSCs was obtained from accession Nos. GSM1865691 and GSM1865692. The OCT4 ChIP-seq data of human PSCs was obtained from accession No. GSM1705268. The OCT4 ChIP-seq data of mouse PSCs was obtained from accession Nos. GSM1693784 and GSM16937845. The GABPA ChIP-seq data of humans and mice PSCs was obtained from accession Nos. GSM803424 and GSM3258762. The H3K4me3 ChIP-seq data and gene expression profiles of human PSCs were obtained from accession No. GSE16256. The H3K4me3 ChIP-seq data of mouse PSCs was obtained from accession No. GSM594581. Gene expression profiles of mouse and human early embryos were downloaded from the DevOmics (85), and that of pigs came from accession No. GSE112380. Gene expression profiles of mouse PSCs were obtained from accession No. GSM2533843. Information about human and mouse PSCs TAD boundaries was taken from http://3dgenome.org, and the Hi-C data of porcine PSCs was sourced from the Jianyong Han laboratory (CRA003960) (86).

References

- 1.Li X., et al. , Generation and application of mouse-rat allodiploid embryonic stem cells. Cell 164, 279–292 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu J., et al. , Interspecies chimerism with mammalian pluripotent stem cells. Cell 168, 473–486.e15 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu T., et al. , Cross-species single-cell transcriptomic analysis reveals pre-gastrulation developmental differences among pigs, monkeys, and humans. Cell Discov. 7, 8 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi K., Yamanaka S., A decade of transcription factor-mediated reprogramming to pluripotency. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 183–193 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shi Y., Inoue H., Wu J. C., Yamanaka S., Induced pluripotent stem cell technology: A decade of progress. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 16, 115–130 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ying Q. L., et al. , The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature 453, 519–523 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Theunissen T. W., et al. , Systematic identification of culture conditions for induction and maintenance of naive human pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 15, 471–487 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao X., et al. , Establishment of porcine and human expanded potential stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 21, 687–699 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang W., et al. , Changes in regeneration-responsive enhancers shape regenerative capacities in vertebrates. Science 369, eaaz3090 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pott S., Lieb J. D., What are super-enhancers? Nat. Genet. 47, 8–12 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang J., et al. , Super enhancers-Functional cores under the 3D genome. Cell Prolif. 54, e12970 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X., Cairns M. J., Yan J., Super-enhancers in transcriptional regulation and genome organization. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 11481–11496 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hnisz D., et al. , Super-enhancers in the control of cell identity and disease. Cell 155, 934–947 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen C., et al. , SEA version 3.0: A comprehensive extension and update of the Super-Enhancer archive. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D198–D203 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong R. W. J., et al. , Enhancer profiling identifies critical cancer genes and characterizes cell identity in adult T-cell leukemia. Blood 130, 2326–2338 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whyte W. A., et al. , Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell 153, 307–319 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrawal P., et al. , Genome editing demonstrates that the -5 kb Nanog enhancer regulates Nanog expression by modulating RNAPII initiation and/or recruitment. J. Biol. Chem. 296, 100189 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blinka S., Reimer M. H. Jr, Pulakanti K., Rao S., Super-enhancers at the Nanog locus differentially regulate neighboring pluripotency-associated genes. Cell Rep. 17, 19–28 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou H. Y., et al. , A Sox2 distal enhancer cluster regulates embryonic stem cell differentiation potential. Genes Dev. 28, 2699–2711 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y., et al. , CRISPR reveals a distal super-enhancer required for Sox2 expression in mouse embryonic stem cells. PLoS One 9, e114485 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watts J. L., Ralston A., Universal assembly instructions for the placenta. Nature 587, 370–371 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh G., et al. , A flexible repertoire of transcription factor binding sites and a diversity threshold determines enhancer activity in embryonic stem cells. Genome Res. 31, 564–575 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinoshita M., et al. , Capture of mouse and human stem cells with features of formative pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 28, 453–471.e8 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu X., et al. , Evolutionary epigenomic analyses in mammalian early embryos reveal species-specific innovations and conserved principles of imprinting. Sci. Adv. 7, eabi6178 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kinoshita M., et al. , Pluripotent stem cells related to embryonic disc exhibit common self-renewal requirements in diverse livestock species. Development 148, dev199901 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prather R. S., Pig genomics for biomedicine. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 122–124 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang L., et al. , Porcine germline genome engineering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2004836117 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan S., et al. , A huntingtin knockin pig model recapitulates features of selective neurodegeneration in Huntington’s disease. Cell 173, 989–1002.e13 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xue B., et al. , Porcine pluripotent stem cells derived from IVF embryos contribute to chimeric development in vivo. PLoS One 11, e0151737 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma Y., Yu T., Cai Y., Wang H., Preserving self-renewal of porcine pluripotent stem cells in serum-free 3i culture condition and independent of LIF and b-FGF cytokines. Cell Death Discov. 4, 21 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu D., et al. , Silencing of retrotransposon-derived imprinted gene RTL1 is the main cause for postimplantational failures in mammalian cloning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E11071–E11080 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ezashi T., et al. , Derivation of induced pluripotent stem cells from pig somatic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 10993–10998 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu Z., et al. , BCL2 enhances survival of porcine pluripotent stem cells through promoting FGFR2. Cell Prolif. 54, e12932 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Creyghton M. P., et al. , Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 21931–21936 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barski A., et al. , High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129, 823–837 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mansour M. R., et al. , Oncogene regulation. An oncogenic super-enhancer formed through somatic mutation of a noncoding intergenic element. Science 346, 1373–1377 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang Y., et al. , SEdb: A comprehensive human super-enhancer database. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 (D1), D235–D243 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mack S. C., et al. , Therapeutic targeting of ependymoma as informed by oncogenic enhancer profiling. Nature 553, 101–105 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song M., et al. , Mapping cis-regulatory chromatin contacts in neural cells links neuropsychiatric disorder risk variants to target genes. Nat. Genet. 51, 1252–1262 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu T., Pinto H. B., Kamikawa Y. F., Donohoe M. E., The BET family member BRD4 interacts with OCT4 and regulates pluripotency gene expression. Stem Cell Reports 4, 390–403 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Micco R., et al. , Control of embryonic stem cell identity by BRD4-dependent transcriptional elongation of super-enhancer-associated pluripotency genes. Cell Rep. 9, 234–247 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan S. H., et al. , Brd4 and P300 confer transcriptional competency during zygotic genome activation. Dev. Cell 49, 867–881.e8 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hotta A., et al. , Isolation of human iPS cells using EOS lentiviral vectors to select for pluripotency. Nat. Methods 6, 370–376 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gertz J., et al. , Distinct properties of cell-type-specific and shared transcription factor binding sites. Mol. Cell 52, 25–36 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hartl D., et al. , CG dinucleotides enhance promoter activity independent of DNA methylation. Genome Res. 29, 554–563 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Srivastava M., et al. , The Amphimedon queenslandica genome and the evolution of animal complexity. Nature 466, 720–726 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Villar D., et al. , Enhancer evolution across 20 mammalian species. Cell 160, 554–566 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wong E. S., et al. , Deep conservation of the enhancer regulatory code in animals. Science 370, eaax8137 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Irimia M., Maeso I., Roy S. W., Fraser H. B., Ancient cis-regulatory constraints and the evolution of genome architecture. Trends Genet. 29, 521–528 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kvon E. Z., et al. , Progressive loss of function in a limb enhancer during snake evolution. Cell 167, 633–642.e11 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y., et al. , The 3D genome browser: A web-based browser for visualizing 3D genome organization and long-range chromatin interactions. Genome Biol. 19, 151 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhi M., et al. , Generation and characterization of stable pig pregastrulation epiblast stem cell lines. Cell Res. 32, 383–400 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anonymous; Zoonomia Consortium, A comparative genomics multitool for scientific discovery and conservation. Nature 587, 240–245 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blanchette M., et al. , Aligning multiple genomic sequences with the threaded blockset aligner. Genome Res. 14, 708–715 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang J., et al. , Dynamic control of enhancer repertoires drives lineage and stage-specific transcription during hematopoiesis. Dev. Cell 36, 9–23 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Avilion A. A., et al. , Multipotent cell lineages in early mouse development depend on SOX2 function. Genes Dev. 17, 126–140 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Velychko S., et al. , Excluding Oct4 from Yamanaka cocktail unleashes the developmental potential of iPSCs. Cell Stem Cell 25, 737–753.e4 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kang M., Garg V., Hadjantonakis A. K., Lineage establishment and progression within the inner cell mass of the mouse blastocyst requires FGFR1 and FGFR2. Dev. Cell 41, 496–510.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fang L., et al. , A methylation-phosphorylation switch determines Sox2 stability and function in ESC maintenance or differentiation. Mol. Cell 55, 537–551 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Molotkov A., Mazot P., Brewer J. R., Cinalli R. M., Soriano P., Distinct requirements for FGFR1 and FGFR2 in primitive endoderm development and exit from pluripotency. Dev. Cell 41, 511–526.e4 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Masui S., et al. , Pluripotency governed by Sox2 via regulation of Oct3/4 expression in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 625–635 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Takehara T., Teramura T., Onodera Y., Frampton J., Fukuda K., Cdh2 stabilizes FGFR1 and contributes to primed-state pluripotency in mouse epiblast stem cells. Sci. Rep. 5, 14722 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bendall S. C., et al. , IGF and FGF cooperatively establish the regulatory stem cell niche of pluripotent human cells in vitro. Nature 448, 1015–1021 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Laird P. W., et al. , In vivo analysis of Pim-1 deficiency. Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 4750–4755 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aksoy I., et al. , Self-renewal of murine embryonic stem cells is supported by the serine/threonine kinases Pim-1 and Pim-3. Stem Cells 25, 2996–3004 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brady J. J., et al. , Early role for IL-6 signalling during generation of induced pluripotent stem cells revealed by heterokaryon RNA-seq. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 1244–1252 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ebeid D. E., et al. , Pim1 maintains telomere length in mouse cardiomyocytes by inhibiting TGFβ signalling. Cardiovasc. Res. 117, 201–211 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Didichenko S. A., Spiegl N., Brunner T., Dahinden C. A., IL-3 induces a Pim1-dependent antiapoptotic pathway in primary human basophils. Blood 112, 3949–3958 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brasó-Maristany F., et al. , PIM1 kinase regulates cell death, tumor growth and chemotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer. Nat. Med. 22, 1303–1313 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Masaki H., et al. , Inhibition of apoptosis overcomes stage-related compatibility barriers to chimera formation in mouse embryos. Cell Stem Cell 19, 587–592 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thomas G. D., et al. , Deleting an Nr4a1 super-enhancer subdomain ablates Ly6Clow monocytes while preserving macrophage gene function. Immunity 45, 975–987 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thomas H. F., et al. , Temporal dissection of an enhancer cluster reveals distinct temporal and functional contributions of individual elements. Mol. Cell 81, 969–982.e13 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bell E., et al. , Dynamic CpG methylation delineates subregions within super-enhancers selectively decommissioned at the exit from naive pluripotency. Nat. Commun. 11, 1112 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang J., et al. , Establishment of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knock-in system for porcine cells with high efficiency. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 189, 26–36 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li N., et al. , Reconstitution of male germline cell specification from mouse embryonic stem cells using defined factors in vitro. Cell Death Differ. 26, 2115–2124 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pérez-Rico Y. A., et al. , Comparative analyses of super-enhancers reveal conserved elements in vertebrate genomes. Genome Res. 27, 259–268 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ramírez F., et al. , High-resolution TADs reveal DNA sequences underlying genome organization in flies. Nat. Commun. 9, 189 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Felsenstein J., Churchill G. A., A Hidden Markov Model approach to variation among sites in rate of evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 13, 93–104 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Karolchik D., et al. ; University of California Santa Cruz, The UCSC genome browser database. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 51–54 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kumar S., Stecher G., Li M., Knyaz C., Tamura K., MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang J., et al. , Data from “Super-enhancers conserved within placental mammals maintain stem cell pluripotency.” National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=PRJNA866208. Deposited 5 August 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Zhu Z., et al. , Histone demethylase complexes KDM3A and KDM3B cooperate with OCT4/SOX2 to define a pluripotency gene regulatory network. The FASEB Journal 35, (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang J., et al. , Data from “Super-enhancers conserved within placental mammals maintain stem cell pluripotency.” National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=PRJNA633419. Deposited 18 May 2020.

- 84.Lister R., et al. , Hotspots of aberrant epigenomic reprogramming in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 471, 68–73 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yan Z., et al. , DevOmics: an integrated multi-omics database of human and mouse early embryo. Brief. Bioinform. 22, (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhi M., et al. , Generation and characterization of stable pig pregastrulation epiblast stem cell lines. Cell Res. 32, 383–400 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

H3K27ac, H3K4me3, and BRD4 ChIP-seq in porcine PSCs were performed in this study and uploaded to National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under the accession number PRJNA866208 (81). Previously published data were used for this work (i.e., H3K9me2, H3K9me3, OCT4, and SOX2 ChIP-seq and RNA-seq data in porcine PSCs have been uploaded to the National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI] Sequence Read Archive database under the accession No. PRJNA633419 by our laboratory) (82, 83). The H3K27ac ChIP-seq data of human PSCs was obtained from NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus accession No. GSM466732 (84). The H3K27ac ChIP-seq data of mouse PSCs was obtained from accession Nos. GSM594578 and GSM594579. The BRD4 ChIP-seq data of human PSCs was obtained from accession No. GSM1466835. The BRD4 ChIP-seq data of mouse PSCs was obtained from accession Nos. GSM1865691 and GSM1865692. The OCT4 ChIP-seq data of human PSCs was obtained from accession No. GSM1705268. The OCT4 ChIP-seq data of mouse PSCs was obtained from accession Nos. GSM1693784 and GSM16937845. The GABPA ChIP-seq data of humans and mice PSCs was obtained from accession Nos. GSM803424 and GSM3258762. The H3K4me3 ChIP-seq data and gene expression profiles of human PSCs were obtained from accession No. GSE16256. The H3K4me3 ChIP-seq data of mouse PSCs was obtained from accession No. GSM594581. Gene expression profiles of mouse and human early embryos were downloaded from the DevOmics (85), and that of pigs came from accession No. GSE112380. Gene expression profiles of mouse PSCs were obtained from accession No. GSM2533843. Information about human and mouse PSCs TAD boundaries was taken from http://3dgenome.org, and the Hi-C data of porcine PSCs was sourced from the Jianyong Han laboratory (CRA003960) (86).