Significance

Developing photocatalysts that can complete CO2 reduction and H2O oxidation reactions simultaneously to realize artificial photosynthesis has great significance for energy and climate issues. Regulating the transfer mode of photogenerated charges in catalysts can greatly improve the efficiency of charge separation and photocatalytic performance. Here, three molecular oxidation–reduction (OR) junctions were constructed by connecting oxidation and reduction clusters in different ways and realized efficient artificial photosynthesis. These OR junctions served as a clear molecular model system to firstly explore the specific effects of different connection modes of oxidation and reduction parts on the migration of photogenerated charges. The specific design schemes of molecular OR junctions can further guide the subsequent design and synthesis of more-efficient catalysts for artificial photosynthesis.

Keywords: artificial photosynthesis, heterogeneous photocatalyst, photocatalytic CO2 reduction, polyoxometalate

Abstract

Constructing redox semiconductor heterojunction photocatalysts is the most effective and important means to complete the artificial photosynthetic overall reaction (i.e., coupling CO2 photoreduction and water photo-oxidation reactions). However, multiphase hybridization essence and inhomogeneous junction distribution in these catalysts extremely limit the diverse design and regulation of the modes of photogenerated charge separation and transfer pathways, which are crucial factors to improve photocatalytic performance. Here, we develop molecular oxidation–reduction (OR) junctions assembled with oxidative cluster (PMo12, for water oxidation) and reductive cluster (Ni5, for CO2 reduction) in a direct (d-OR), alternant (a-OR), or symmetric (s-OR) manner, respectively, for artificial photosynthesis. Significantly, the transfer direction and path of photogenerated charges between traditional junctions are obviously reformed and enriched in these well-defined crystalline catalysts with monophase periodic distribution and thus improve the separation efficiency of the electrons and holes. In particular, the charge migration in s-OR shows a periodically and continuously opposite mode. It can inhibit the photogenerated charge recombination more effectively and enhance the photocatalytic performance largely when compared with the traditional heterojunction models. Structural analysis and density functional theory calculations disclose that, through adjusting the spatial arrangement of oxidation and reduction clusters, the energy level and population of the orbitals of these OR junctions can be regulated synchronously to further optimize photocatalytic performance. The establishment of molecular OR junctions is a pioneering important discovery for extremely improving the utilization efficiency of photogenerated charges in the artificial photosynthesis overall reaction.

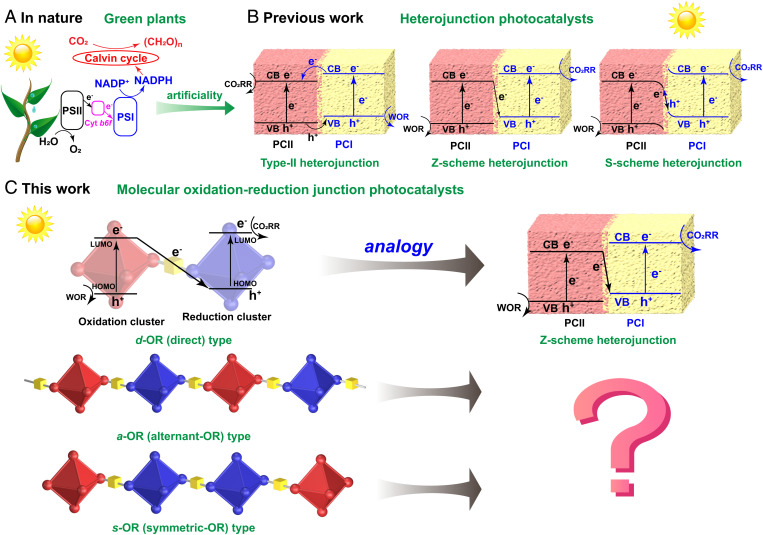

To cope with the increasingly serious greenhouse effect, exploring green, economic, and sustainable CO2 conversion and utilization methods to achieve carbon neutrality has become an important research goal of global development (1–7). As we all know, green plants can use solar energy to complete photosynthesis, that is, effectively reducing CO2 to energy-rich organic carbon products along with oxidizing H2O to O2 (Scheme 1A) (8, 9). By simulating the synergistic mode of photosystem I (PSI) and PSII in natural photosynthesis, type-II/Z-scheme/S-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst combining two different kinds of semiconductor materials (photocatalyst I [PCI] and PCII), with the characteristics of improved separation efficiency of photogenerated electron hole and strong redox capability, has been proposed to realize the artificial photosynthesis (Scheme 1B) (10–13). However, heterojunction materials are difficult to achieve precisely structural adjustment on the oxidative and reductive components from the molecular level. Therefore, it is almost impossible to study the specific effect of the different connection modes and spatial orientations of oxidative and reductive moieties in catalysts systematically on photocatalytic performance. In contrast, inspired by the design concept of heterojunctions, we think that using oxidative and reductive structural motifs to construct periodically distributed molecular junctions, which can essentially create more charge separation and transfer pathways, represents a good choice to achieve the above objective.

Scheme 1.

Photocatalytic mechanisms in different systems. (A) Operational mechanism of photosynthesis in green plants. (B) Operational mechanisms of artificial photosynthesis in heterojunction catalysts. The mentioned three kinds of heterojunction photocatalysts (type II, Z scheme, and S scheme) are all composed of oxidative part and reductive parts. The reason for their different categories is the distinction in charge transfer between the oxidative and reductive parts. (C) Operational mechanisms of artificial photosynthesis in molecular OR junctions.

In the proposed biomimetic oxidation–reduction (OR) junction, a specific electron transfer mode can occur between the oxidation part and reduction part under light irradiation. Hence, a single molecular OR junction can be regarded as a subminiature heterojunction. It is well known that classic heterojunction catalysts are composed of two or more kinds of semiconductor materials by bulk phase recombination; the oxidative and reductive components are concentrated in their respective regions (14–17). However, the oxidative and reductive catalytic moieties in molecular junctions are spatially periodically arranged. Consequently, the nature of molecular OR catalysts is quite different from the traditional heterojunction catalysts. More importantly, oxidation and reduction parts in the lattice of the molecular junctions can be arranged and connected in diversely spatial patterns (e.g., alternating or symmetrical manner), which means that more possibilities of charge separation and transfer pathway can be achieved in the finite or infinite structures of molecular junctions. These cases may also take place in the aggregative heterojunction, but it is difficult to carry out precise structural design and regulation in such a complicated multiphase hybrid system. In this regard, the well-defined crystalline structures and monophase periodic distribution of molecular OR junctions can provide a clear and intuitive research platform. In addition, the small size of the clusters (usually <3 nm) ensures the rapid charge migration between junctions (18).

Based on the above considerations, we designed and constructed three molecular OR junctions, (PMo12O40){Ni5(bzt)6(H2O)8(C2H5O)(py)2(NO3)} (d-OR, 1H-btz = 1H-benzotriazole, py = pyrazine), (PMo12O40){Ni5(bzt)6(H2O)3(C2H5O)5(NO3)} (a-OR), and {(PMo12O40)Ni5(bzt)6(H2O)5(C2H5O)(py)2(NO3)}2(py) (s-OR), which are assembled with oxidative (O) polyoxometallate H3PMo12O40 (PMo12) cluster and reductive (R) Ni5(bzt)6(NO3)4(H2O)4 (Ni5) cluster in direct, alternant, and symmetric manners, respectively (Scheme 1C). According to the energy-level distribution, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and in situ XPS analysis, we found that the separation and transfer pathway of photogenerated charges between PMo12 and Ni5 clusters in d-OR is similar to the PCI and PCII systems in Z-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst. Therefore, d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR represent an appropriate molecular model system to explore the specific influence of the different connection modes and spatial orientations of oxidation and reduction parts in catalyst on the photocatalytic performance. As expected, when d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR are used as photocatalysts, they all exhibit superior artificial photosynthesis performance in a mixed atmosphere of CO2 and water vapor and are more efficient than independent Ni5 and PMo12. In these three molecular junctions, PMo12 and Ni5 act as oxidative and reductive catalytic sites to convert H2O and CO2 into O2 and CO. The bridging O atoms enable rapid charge transfer between PMo12 and Ni5. After 10 h of light irradiation, the yield of produced CO is s-OR (238.68 μmol/g) > d-OR (152.70 μmol/g) > a-OR (112.19 μmol/g), indicating that the connection modes between the oxidation part and the reduction part indeed exert an important influence on photocatalytic performance. Through the comparison of the migration of photogenerated electrons and holes, we found that, compared with d-OR, the photogenerated charges of s-OR can transfer to the lower energy level, thereby decreasing the catalytic efficiency. Furthermore, density functional theory (DFT) calculations proved that the rearrangement of the orbitals leads to a decreased lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy level of Ni5 in d-OR, which is more conducive to the occurrence of the catalytic reaction. In a-OR, the orbital distribution changes slightly relative to unconnected monomers Ni5 and PMo12. When d-OR is connected in a symmetric model to form s-OR, a new lower vacant orbital will be generated in the center of the R-R part to promote the photoexcited charge transfer process and inhibit the electron hole recombination of the Ni5 part. This work discloses that the diversified connection modes and spatial arrangements of oxidative and reductive components in catalysts for artificial photosynthetic overall reaction can greatly alter the separation and recombination efficiency of photogenerated charges and then make an impact on the final photocatalytic performance. More importantly, the establishment of molecular OR junctions provides a very important platform for discovering and deeply understanding more migration types of photogenerated charges in photocatalysts.

Results

Structural Design and Fabrication of Photocatalysts.

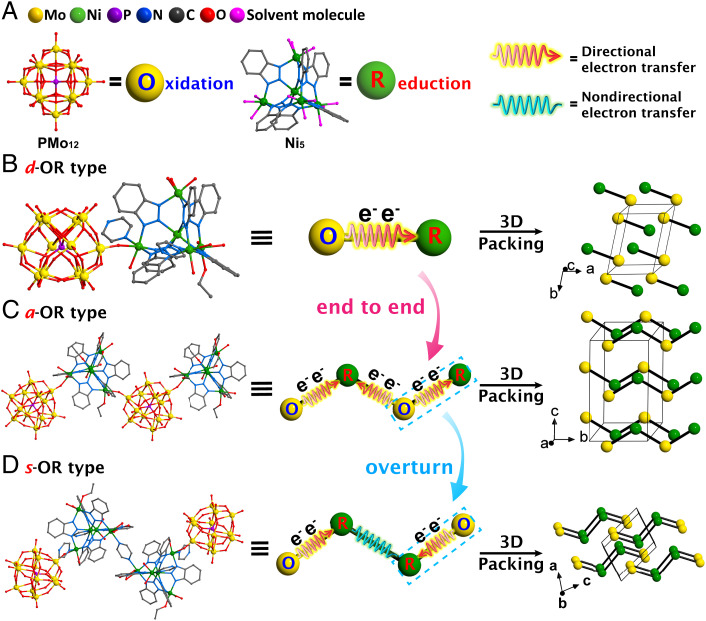

It is very important to select suitable oxidative and reductive clusters to successfully construct OR junction photocatalysts. The following points need to be considered. (1) These two kinds of clusters should have oxidizability and reducibility, respectively. (2) These two kinds of clusters should possess appropriate charge properties (such as anion and cation, respectively), which can make it easy to be connected through chemical bonds and crystallized. Following these ideas, we select a classical polyoxometalate (PMo12) as the oxidative cluster unit and a Ni-based cluster (Ni5) as the reductive cluster unit to assemble OR photocatalysts. Ni5 is a compound with a tetrahedral configuration (19). Each metal ion at the vertex of the tetrahedron coordinates with a water molecule and a NO3¯ ion, of which the NO3¯ can be replaced by other anionic groups (20, 21) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

Three types of OR photocatalysts, d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR, were synthesized by a simple solvothermal method using PMo12, Ni5, and pyrazine as the raw materials (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis reveals that d-OR assembled directly with PMo12 and Ni5 clusters crystallizes in the triclinic space group P-1 (SI Appendix, Table S1). Ni5 cluster keeps its original host tetrahedral configuration, but one of its original NO3¯ ions is replaced by a terminal O atom from PMo12 (Fig. 1B). The bridging O atom connecting PMo12 and Ni5 in a very short distance of 3.86 Å may allow for rapid photogenerated charge transfer. Intermolecular hydrogen bonds and π–π interactions between ligands make d-OR molecules form a three-dimensional supramolecular compound (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). a-OR crystallizes in the monoclinic space group P21/c and two formula units (Z = 2) per unit cell (SI Appendix, Table S1) and is a one-dimensional chain structure by connecting PMo12 and Ni5 clusters alternately (Fig. 1C). The a-OR chains are further extended into a three-dimensional supramolecular array via hydrogen bonds (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). It’s worth noting that all the vertical Ni ions in d-OR and a-OR coordinate with at least one solvent molecule that is easy to leave and makes exposed Ni ions as potential open sites for the adsorption and activation of substrates (SI Appendix, Figs. S5 and S6). That is to say, the number of catalytic sites is equivalent to the number of vertical Ni ions in d-OR and a-OR. The s-OR type molecule is built from a pyrazine group connecting two mirror-symmetric OR units (O-R-py-R-O). SCXRD analysis shows that s-OR crystallizes in the triclinic space group P-1 and one formula unit (Z = 1) per unit cell (SI Appendix, Table S1). The part of “OR” in s-OR has almost the same configuration as a single d-OR molecule (Fig. 1D). The coordination-saturated Ni linkers (Ni3 and Ni5) are encompassed by two O from chelate NO3¯ ions and four N atoms from three bzt¯ and pyrazine ligands, which indicates these Ni ions in s-OR cannot serve as catalytic sites (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). The s-OR molecules are further stacked into three-dimensional supramolecular structures through multiple hydrogen bonds and π–π interactions (SI Appendix, Fig. S8).

Fig. 1.

The structure composition of photocatalysts. (A) Crystal structures and simplified balls of oxidative PMo12 cluster and reductive Ni5 cluster. The red arrows represent the directional photoelectron transfer between clusters. The cyan curves represent the nondirectional charge transfer between two clusters. (B–D) Crystal structures determined by SCXRD analysis, simplified structures, and packing diagrams of d-OR-, a-OR-, and s-OR-type photocatalysts. The simplified diagram in the Middle shows possible charge transfer between PMo12 (O) and Ni5 (R) clusters. All hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

Characterization of Photocatalysts.

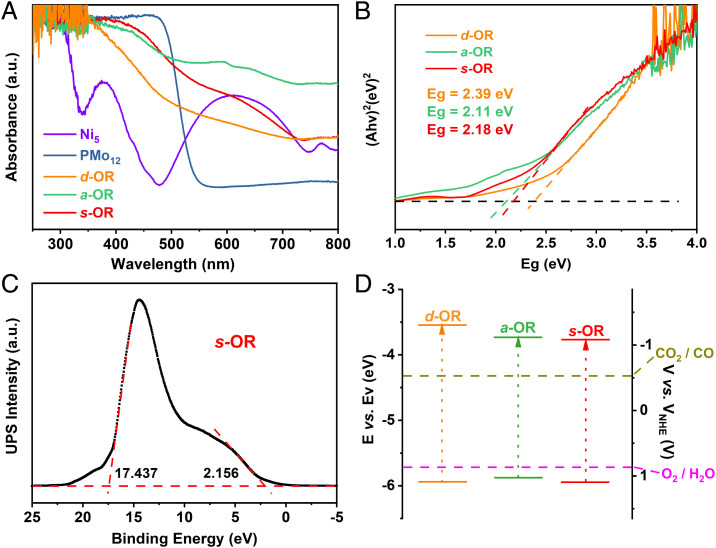

The purity of d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR was confirmed by the well-matched experimental and simulated powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). The ultraviolet and visible (UV-Vis) absorption spectra of Ni5, PMo12, d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR were characterized to compare their light-harvesting ability. As shown in Fig. 2A, PMo12 shows strong absorption in the range of 250–480 nm, while Ni5 exhibits a broad absorption range of 250–700 nm. It is noted that, when PMo12 and Ni5 were assembled into d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR, their light absorption was throughout the whole range of 250–800 nm. Obviously, these OR photocatalysts show better sunlight utilization than independent PMo12 and Ni5. The band gap energy (Eg) of d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR were further calculated to be 2.39 eV, 2.11 eV, and 2.18 eV, respectively, through Tauc plots (Fig. 2B). Moreover, UV photoelectron spectrometer (UPS) experiment was carried out to confirm their highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) positions (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S12) (22). The obtained HOMO values were −6.30 eV, −5.92 eV, and −5.84 eV (vs. vacuum level) for d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR respectively, which are all below the oxidation level (−5.67 eV vs. vacuum level) for H2O to O2 (23). Then the LUMO levels were determined at −3.91 eV (d-OR), −3.76 eV (a-OR), and −3.53 eV (s-OR) that are all above the reduction level for CO2-to-CO reduction (−4.34 eV vs. vacuum level) (24). Based on the above results, the band structures of d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR are properly positioned to thermodynamically achieve CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR) and water oxidation reaction (WOR) simultaneously, corroborating their potential to be catalysts for artificial photosynthetic overall reaction (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of the electronic structures of d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR. (A) UV-Vis absorption spectra of Ni5 (purple), PMo12 (blue), d-OR (yellow), a-OR (green), and s-OR (red) in the range of 250–800 nm. (B) Diffuse reflectance UV-Vis spectra of K–M function versus Ev (eV) of d-OR (yellow), a-OR (green) and s-OR (red). The intersection values of the tangents with the baseline are their corresponding values of band gaps. (C) UPS spectra of s-OR. The horizontal dashed red line is the baseline. The other two dashed red lines are the tangent of the curve. The intersection values of the tangents with the baseline are the edges of the UPS spectra. a.u., arbitrary unit. (D) Band structure diagram for d-OR (yellow), a-OR (green), and s-OR (red). All of the three molecular junctions can achieve artificial photosynthetic overall reaction thermodynamically.

Artificial Photosynthetic Overall Reaction.

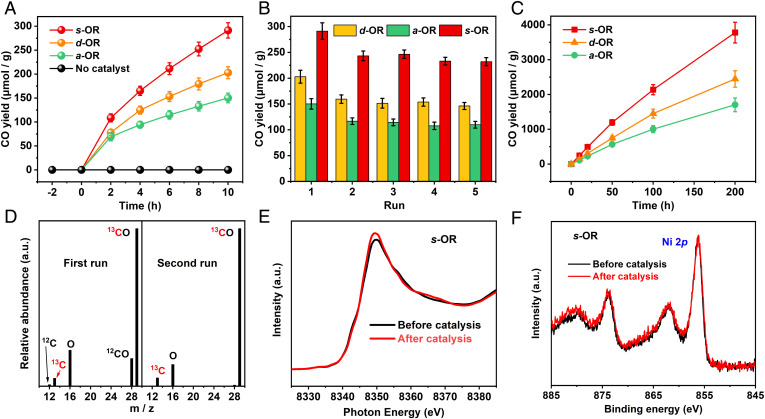

Benefiting from the broad range of light absorption and appropriate band structures of d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR, they were utilized as catalysts to perform the photosynthetic overall reaction in a gas–solid system under illumination. The entire catalytic system runs only in the presence of photocatalysts, water vapor, and CO2. The results showed that all these photocatalysts can convert CO2 and H2O into CO and O2. After 10 h of light irradiation, independent Ni5 and PMo12 clusters showed low CO yields of 71.27 μmol/g and 46.95 μmol/g, respectively. In sharp contrast, d-OR, one of the assemblies composed of Ni5 and PMo12 clusters, revealed a much higher performance, with the CO yield of 202.88 μmol/g. It’s obvious that the connection of Ni5 and PMo12 through a bridging O atom greatly promotes the efficiency of photocatalysis. Under the identical reaction condition, the CO yield (170.12 μmol/g) catalyzed by a-OR was slightly lower than d-OR, while s-OR revealed the highest CO2-to-CO reduction performance (271.25 μmol/g) among them (Fig. 3A). Moreover, H2 as the most-common primary competitive product was not detected by gas chromatography (SI Appendix, Figs. S13 and S14).

Fig. 3.

Photocatalytic CO2 reduction performance of d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR. (A) The yield of CO catalyzed by d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR. (B) Cycle performance of d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR. (C) Photocatalytic durability of d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR under continual irradiation. (D) Mass spectra extracted from gas chromatography–mass spectrometry analysis of CO product from 13CO2 reduction. The molecular ion peaks appearing at m/z peak of 12, 13, 16, 28, and 29 are ascribed to 12C, 13C, 16O, 12C16O, and 13C16O, respectively. (E and F) Ni L-edge X-ray absorption near-edge spectroscopy spectra (E) and high-resolution Ni 2p XPS spectra (F) of s-OR before and after catalysis.

A series of deletional control experiments were carried out to confirm the whole reaction, of which no photosynthetic products could be detected with the absence of photocatalysts or in the dark (SI Appendix, Table S5). When the reaction system was lacking water or performed under Ar atmosphere, only small amounts of CO were produced (ca. 48 μmol/g for d-OR, 28 μmol/g for a-OR, and 47 μmol/g for s-OR, as entries 3 and 5 shown in SI Appendix, Table S5). It suggested that the photosynthetic system was operated by light, photocatalysts, CO2, and H2O together. The durability of photocatalysts was evaluated by refilling CO2 and water after each 10-h run (see details in SI Appendix); it was found that the CO production catalyzed by d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR were dropped to 159.42, 136.78, and 223.23 μmol/g, respectively, on the second run. Then the yields of CO displayed negligible decay on the next three runs, suggesting the outstanding recyclability of these three photocatalysts (Fig. 3B). The catalytic stability was further assessed by keeping the reaction under continuous irradiation. The production of CO increased almost linearly in at least 200 h (Fig. 3C). Combined with the cycling experiments, d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR all revealed excellent catalytic durability. As for WOR, the production of O2 was evaluated on an online test system. The molar ratio of produced CO and O2 was close to stoichiometric 2:1, being in line with the theoretical value (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). Isotope-tracing experiments were carried out to prove these photocatalysts are indeed active for simultaneous CO2RR and WOR rather than decomposition of photocatalysts. When using fresh s-OR as a representative photocatalyst under water vapor and 13CO2 atmosphere to operate the overall reaction, only a trace amount of CH4, C2H6, and acetaldehyde (CH3CHO), as well as the main CO and O2 product, could be detected by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. By analyzing the m/z values of products, CH4, C2H6, and CH3CHO were not labeled by 13C (SI Appendix, Fig. S16), and two obvious signals at m/z 28 and 29 corresponding to 12CO and 13CO were shown in the CO peak with the ratio of absolute abundance of 1:5 (Fig. 3 C, Left). The content of 12CO was close to the yield loss between the first and second runs of the cycling test. The unlabeled products might be derived from the conversion of ethanol molecules in the catalysts, which caused the decline in CO yield during the first two runs of the cycling experiment. Then we reintroduce 13CO2 into the reactor for the second run of illumination. The result showed that only CO could be detected, and the signal at m/z 28 was minuscule (<1% contrasted with m/z 29, Fig. 3 C, Right). It can be concluded that CO production in the second run was all converted from CO2. The O source in O2 was verified by using H218O as the reactant; the obvious m/z peak at 36 revealed that the O2 was indeed converted from H2O (SI Appendix, Fig. S17). After photocatalysis, the unchanged X-ray absorption near-edge spectroscopy and XPS spectra indicated the structural integrity of the used catalysts (Fig. 3 D and E and SI Appendix, Fig. S18). Obviously, d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR cannot only complete the artificial photocatalytic overall reaction like traditional heterojunction catalysts but can also establish a pioneering system to study the influence of the connection mode and spatial arrangement of oxidation and reduction components on the photocatalytic performance from their clear and periodically distributed structures, which has never been reported before. Therefore, in this work, we call these constructed molecular compound catalysts “molecular OR junctions”. They may be widely used to study the important effects of more-unknown photogenerated charge separation and transfer paths between redox components in catalysts on the photocatalytic performance of the overall reaction.

Discussion

It is well recognized that the efficiency of photocatalysis is mainly affected by light harvesting, charge separation, and charge utilization (25). Because of the similar light absorption and catalytic sites of d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR, the efficiency of charge separation, in other words, electron hole recombination, may affect their performance of artificial photosynthesis mostly. We notice that the ratio of Ni5 and PMo12 units are all 1:1 in d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR, so the connection modes and spatial orientations of Ni5 and PMo12 clusters in these molecular OR junctions may be the key factors to impact their charge separation efficiency. From the analysis of the band structures of PMo12 and Ni5 (SI Appendix, Figs. S19 and S20), the LUMO and HOMO positions of Ni5 are all more negative than those of PMo12, proving the oxidative capacity of PMo12 and reductive capacity of Ni5. To determine which transfer pathway the photogenerated charges between PMo12 and Ni5 parts in these molecular junctions obeys, the direction of the internal electric field needs to be verified. Due to the larger work function of Ni5 than that of PMo12 (26), electrons can transfer from Ni5 to PMo12 when they link together through a coordination bond (SI Appendix, Fig. S21). XPS results provide further evidence for this fact (SI Appendix, Fig. S22). The negative shift in Mo 3d and the positive shift in Ni 2p of d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR indicate the electron transfer from Ni5 to PMo12, resulting in the formation of an internal electric field from Ni5 to PMo12, which is consistent with the inference of UPS. Importantly, high-resolution in situ XPS spectra for Ni 2p of d-OR were performed. Compared with the dark condition, the negative shift in the Ni 2p binding energy under light irradiation indicates the increased electron density at the Ni sites. The results prove that the migration direction of photogenerated electrons is from PMo12 to Ni5 (SI Appendix, Fig. S23). It follows that, under light irradiation, the photogenerated electrons in the LUMO of PMo12 tend to recombine with the photogenerated holes in the HOMO of Ni5, leaving photogenerated holes in the HOMO of PMo12 and photogenerated electrons in the LUMO of Ni5 with strong redox capacity to complete WOR and CO2RR (SI Appendix, Fig. S24) (27). That means PMo12 and Ni5 link together and combine into d-OR to form a Z-scheme-like molecule.

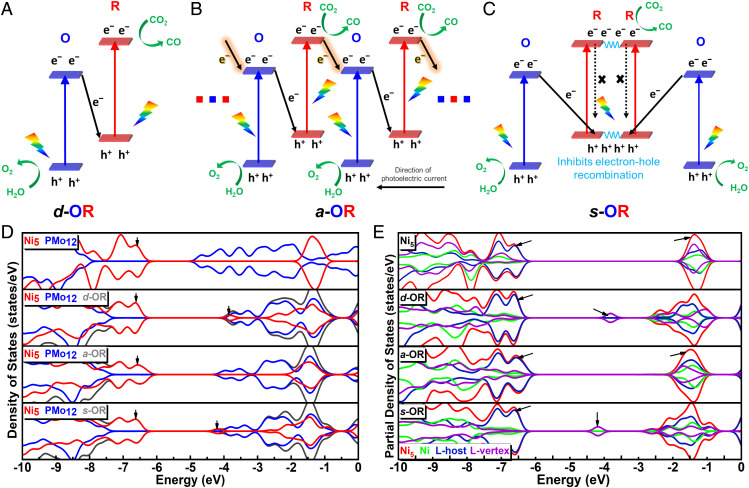

When d-OR is under illumination, electrons are excited from HOMO levels of Ni5 and PMo12 to their corresponding LUMO positions. The photogenerated electrons of PMo12 then transfer to Ni5 under the internal electric field. Then the reserved electrons in the LUMO of Ni5 and holes in the HOMO of PMo12 participate in the CO2RR and WOR, respectively (Fig. 4A). The matched band structures and proper charge migration between Ni5 and PMo12 inhibit the recombination of photogenerated electrons and holes and render d-OR to reveal better performance than Ni5 and PMo12 themselves (SI Appendix, Fig. S24). The consequence is in accordance with the regulation of Z-scheme nanomaterial photocatalysts (12, 28). Additional density of state analysis has also supported this point (Fig. 4D). Compared with the isolated Ni5, the LUMO levels of the Ni5 moieties in d-OR are depressed obviously, resulting in the smaller HOMO–LUMO gaps becoming more easily excited by visible light. And subsequent partial densities of state (PDOS) analysis (Fig. 4E) showed that in the unoccupied states of Ni5 moiety in d-OR existed polarization distribution, which further confirmed that the junction mode of d-OR could inhibit electron hole recombination. When Ni5 and PMo12 are connected alternately to be a-OR through the coordination bonds, the greater orbital overlap between OR fragments would promote more interaction and charge transfer. However, the delocalized distribution of the unoccupied state similar to the isolated Ni5 exists in a-OR, in which the local excited states would be produced and be quenched by fast electron hole recombination. On the other hand, when taking a-OR under light irradiation, following the same regulation as d-OR, the excited electrons of PMo12 transferred to the adjacent Ni5. Nevertheless, because of its infinite one-dimensional structure, the electrons in the LUMO of Ni5 can further migrate to the next PMo12 (Fig. 4B and SI Appendix, Fig. S25). Because some of the electrons transfer to the energy levels with weaker reducing capacity, it can decrease the catalytic performance of a-OR. As for s-OR, because the OR units are jointed together in a mirror-symmetrical manner, the direction of electron migration is far from the holes. It leads to the efficiency of electron-hole separation in s-OR being greatly improved (Fig. 4C). Obviously, a stronger polarization distribution of the unoccupied states exists in s-OR, and the lowest unoccupied state is mainly contributed by L-vertex ligands (Fig. 4E). And due to the connection mode of Ni clusters in s-OR, the LUMO orbital is mainly distributed on the piperazine and NO3 ligands of R-R center (SI Appendix, Fig. S26), which further reduces the overlap of HOMO and LUMO orbitals and inhibits the electron hole recombination of inner Ni5 to improve the catalytic activity of Ni5. Equally important, the steady-state photoluminescence (PL) measurements of d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR were carried out to support the above-mentioned points. The PL emission quenching of a-OR and s-OR is more enhanced and declined than d-OR, respectively, indicating the efficiency of electron hole recombination decreases from a-OR, d-OR, to s-OR (SI Appendix, Fig. S27A) (29, 30). In addition, time-resolved fluorescence decay spectra were performed to evaluate the charge carrier dynamics of d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR (SI Appendix, Fig. 27B and Table S6). The longest average lifetime of s-OR implies that the photogenerated charges in s-OR can survive the longest to participate in the catalytic reaction, in line with the catalytic efficiency.

Fig. 4.

Proposed charge separation and transfer pathways for d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR photocatalysts under light irradiation and corresponding evidence from total densities of state (TDOSs) and partial densities of state (PDOSs). (A–C) According to the calculated band structure and the results of XPS and in situ XPS analysis, the photogenerated charges of d-OR can migrate from PMo12 to Ni5 under light irradiation. When d-OR extends to the infinite one-dimensional structure of a-OR, the photogenerated electrons can further transfer to the next cluster, which fundamentally weakens the reducing capacity. While d-OR changes into s-OR, presenting a mirror-symmetric O-R-R-O pattern, the symmetric charge-transfer pathway can extremely inhibit the recombination of photogenerated electron hole pairs, thus achieving the best photocatalytic performance. (D) TDOS and PDOS of isolated PMo12, isolated Ni5, and Pmo12 and Ni5 moieties of d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR clusters. For the isolated Ni5 and PMo12, there is almost no orbital overlap and hybridization, and the probability of charge transfer is slight. For the d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR clusters, the unoccupied states’ energy levels of Ni5 moieties of d-OR and s-OR exhibit a significant decline. (E) PDOS of isolated Ni5 and Ni5 moiety of d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR clusters. Ni stands for the Ni moiety, L-host stands for the benzotriazole moiety, and L-vertex stands for the piperazine, H2O, and NO3 moieties.

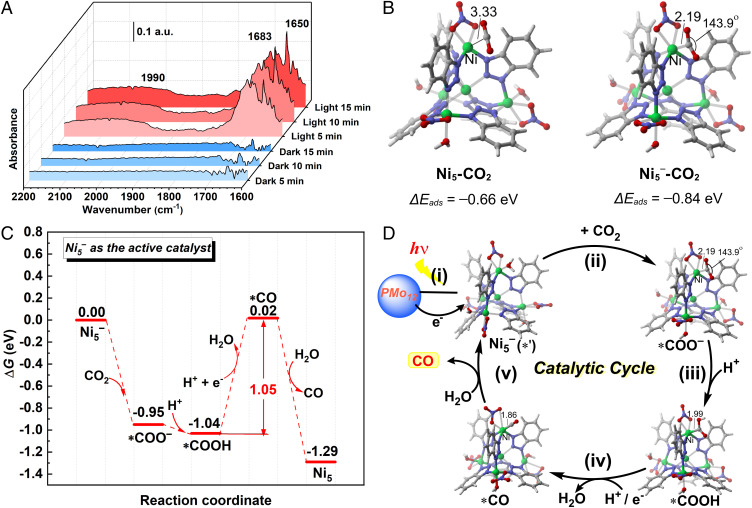

In order to capture the intermediate species during the reaction to study the underlying catalytic mechanism, in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier-transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) was carried out to understand the catalytic process in depth. As shown in Fig. 5A, in a mixed atmosphere of CO2 and water vapor, there was no additional peak appearing after 15 min in the darkness. In sharp contrast, after 5 min of light irradiation, two peaks at 1,650 and 1,683 cm−1 attributed to Ni-CO2− and Ni-CO2H complex rapidly arose (31). The contemporaneous band around 1,990 cm−1 can be assigned to Ni-CO species (32). In order to further understand the reaction mechanism of the CO2RR process, DFT calculations have been carried out by employing Ni5 as the model based on the above results (SI Appendix, Fig. S28). Firstly, we investigated the effect of electron injection on the CO2 adsorption of Ni5. The CO2 adsorption on the neutral Ni5 requires the electronic energy (ΔEads) of −0.66 eV, of which the CO2 molecule remains almost linear and the C−Ni distance is shortened to 3.33 Å. In contrast, the ΔEads value of the reduced Ni5− complex becomes −0.84 eV with a further shortened C−Ni bond distance (2.19 Å) and a slightly curved CO2 moiety (143.9 degree) (Fig. 5B). The calculation results indicate that the reduced Ni5− as the active site is more favorable to adsorbed CO2 forming a carbonate *COO− species than the neutral Ni5. Therefore, Ni5− has potential advantages as an active catalyst of CO2RR. Then, the *COO− captures a proton to afford a stable *COOH (Fig. 5 C and D). Such protonation process is exoergic of 0.09 eV. Subsequently, a proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) process requires a moderate Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°) of 1.05 eV to obtain the *CO species with H2O releasing, which serves as the potential determining step of the CO2RR process. Finally, the target CO product is released via a spontaneous ligand exchange process with the ΔG° value of −1.31 eV. In comparison, the neutral Ni5 complex would undergo two endoergic PCET processes to afford the *CO species, resulting in a large energy barrier of 1.19 eV (SI Appendix, Fig. S30). According to the above-mentioned experiment and calculation results, a favorable CO2RR mechanism catalyzed by the reduced Ni5− has been illustrated in Fig. 5D.

Fig. 5.

Study on mechanism of artificial photosynthesis. (A) In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier-transform spectroscopy under dark and light conditions. (B) Optimized structures of the neutral complex (Ni5) and the charged state (Ni5−) after attracting CO2; the bond lengths are given in Å. The carbon dioxide electron adsorption energy (ΔEads) of Ni5 is −0.66 eV, and the adsorption energy of reduced state Ni5− is −0.84 eV. (C) Gibbs energy profile for the CO2 reduction process to CO production with reduced state Ni5− as the catalytic center. For the intermediate species involved in the catalysis, we also investigated varieties of adsorption possibilities and selected the most-stable structures to evaluate the changes of potential energy surfaces (SI Appendix, Fig. S29). The potential determining step is the CO2RR process with a barrier of 1.05 eV. (D) The proposed possible mechanism: (i) the electron transfer from PMo12 moiety to the Ni5 moiety by photoexcitation; (ii) the activation of CO2 to form *COO− species; (iii) the protonation to obtain *COOH species; (iv) the proton-coupled electron transfer process to afford the reduced *CO species, and (v) the desorption of CO.

Conclusion

In summary, we firstly proposed the concept of molecular OR junctions, and that established such three kinds of model molecular OR junctions to complete the artificial photosynthetic overall reaction. Through linking oxidative PMo12 cluster and reductive Ni5 cluster with a bridge O atom in direct, alternant, and symmetric manners, three molecular junctions, d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR, were successfully obtained. As expected, d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR can all realize outstanding CO2-to-CO photoconversion (15.9, 13.7, and 22.3 μmol g−1 h−1 for d-OR, a-OR, and s-OR, respectively, >200 h) coupled with photo-oxidating H2O to O2, without any assistance of cocatalyst, photosensitizer, or sacrificial agent. Importantly, in virtue of the well-defined and periodic structures of these molecular OR junctions, we investigated the effect of diversified connection modes and spatial arrangements of oxidative and reductive components in overall reaction catalysts on photocatalytic performance. Combined with the related experimental characterization and detailed DFT theoretical calculations, we find that the R-R part in s-OR reduces the overlap of HOMOs and LUMOs and inhibits the recombination of photogenerated electron hole pairs, resulting in the better catalytic activity of s-OR than d-OR and a-OR. Beyond the artificial photosynthetic whole-reaction system, these results may also have implications for other photocatalytic systems, like water splitting or redox organic conversion. Obviously, both of the specific design schemes of molecular OR junctions and the corresponding structure-performance relationship can further guide the subsequent design and synthesis of more-efficient catalysts for artificial photosynthesis.

Materials and Methods

All starting materials, reagents, and solvents used in experiments were commercially available, high-grade purity materials and used without further purification. Thermogravimetric analyses of the samples were performed on a PerkinElmer TG-7 analyzer heated from room temperature to 700 °C in flowing N2/O2 with a heating rate of 20 °C/min. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) measurements were recorded in the range of 4,000–400 cm−1 on a Mattson Alpha-Centauri spectrometer using the technique of pressed KBr pellets. PXRD measurements were recorded ranging from 5 to 50° at room temperature on a D/max 2500 VL/PC diffractometer (Japan) equipped with graphite monochromatized Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54060 Å). The UV-Vis-near infrared spectra were performed on a Varian Cary 5000. XPS and UPS were measured on an Escalab 250Xi. PL spectra were recorded by a FluoroMax-4 spectrofluorometer (HORIBA Scientific). In situ DRIFTS was carried out on a Bruker Tensor II FTIR NEXUS. In situ XPS tests were performed on a ThermoFisher Nexsa.

DFT Calculations.

All of the geometry optimizations, vibrational frequency evaluations, and intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) (33) calculations were performed at the (U)M06 (34) functional with the def2-SVP (35) basis set. More accurate electronic energies on the potential energy surface (PES) were corrected by single-point energy calculations at the (U)M06-D3 (36) functional with the def2-TZVP (37) basis set. The above-mentioned quantum calculations were carried out with the Gaussian 09 (38). The partial density of states (PDOS) were performed for the crystal structure using Multiwfn (39) software with Gaussian broadening function and full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 0.3 eV. The three-dimensional molecular structures were performed by CYLview (40) program, and the relevant molecular orbitals were printed by Visual Molecular Dynamics (41) program.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22225109, 22201082, and 92061101), the Excellent Youth Foundation of Jiangsu Natural Science Foundation (No. BK20211593), and the GuangDong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2021A1515110429).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2210550119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All data are included in the manuscript and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Listorti A., Durrant J., Barber J., Artificial photosynthesis: Solar to fuel. Nat. Mater. 8, 929–930 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo Z., et al. , Self-adaptive dual-metal-site pairs in metal-organic frameworks for selective CO2 photoreduction to CH4. Nat. Catal. 4, 719–729 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang Z., et al. , Filling metal-organic framework mesopores with TiO2 for CO2 photoreduction. Nature 586, 549–554 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo Z., et al. , Selectivity control of CO versus HCOO− production in the visible-light-driven catalytic reduction of CO2 with two cooperative metal sites. Nat. Catal. 2, 801–808 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakimoto K. K., Wong A. B., Yang P., Self-photosensitization of nonphotosynthetic bacteria for solar-to-chemical production. Science 351, 74–77 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding M., Flaig R. W., Jiang H.-L., Yaghi O. M., Carbon capture and conversion using metal-organic frameworks and MOF-based materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 2783–2828 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li X.-X., et al. , Design of crystalline reduction-oxidation cluster-based catalysts for artificial photosynthesis. JACS Au 1, 1288–1295 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan X., et al. , Structural basis of LhcbM5-mediated state transitions in green algae. Nat. Plants 7, 1119–1131 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang B., Sun L., Artificial photosynthesis: opportunities and challenges of molecular catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 2216–2264 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Q., et al. , Molecularly engineered photocatalyst sheet for scalable solar formate production from carbon dioxide and water. Nat. Energy 5, 703–710 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang Y., et al. , All-solid-state Z-scheme α-Fe2O3/amine-RGO/CsPbBr3 hybrids for visible-light-driven photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Chem 6, 766–780 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y., et al. , Direct and indirect Z-scheme heterostructure-coupled photosystem enabling cooperation of CO2 reduction and H2O oxidation. Nat. Commun. 11, 3043 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu F., et al. , Unique S-scheme heterojunctions in self-assembled TiO2/CsPbBr3 hybrids for CO2 photoreduction. Nat. Commun. 11, 4613 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tian Z.-Y., et al. , Construction of LOW-COST Z-scheme heterostructure Cu2O/PCN for highly selective CO2 photoreduction to methanol with water oxidation. Small 17, 2103558 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Low J., Yu J., Jaroniec M., Wageh S., Al-Ghamdi A. A., Heterojunction photocatalysts. Adv. Mater. 29, 1601694 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bian J., et al. , Energy platform for directed charge transfer in the cascade Z-scheme heterojunction: CO2 photoreduction without a cocatalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 60, 20906–20914 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou P., Yu J., Jaroniec M., All-solid-state Z-scheme photocatalytic systems. Adv. Mater. 26, 4920–4935 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li A., et al. , Thin heterojunctions and spatially separated cocatalysts to simultaneously reduce bulk and surface recombination in photocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55, 13734–13738 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bai Y.-L., Tao J., Huang R.-B., Zheng L.-S., The designed assembly of augmented diamond networks from predetermined pentanuclear tetrahedral units. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 47, 5344–5347 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan Y.-X., Zhang Y., He Y.-P., Zheng Y.-J., Microporous metal–organic layer built from pentanuclear tetrahedral units: gas sorption and magnetism. New J. Chem. 38, 5272–5275 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lan Y.-Q., Li S.-L., Jiang H.-L., Xu Q., Tailor-made metal-organic frameworks from functionalized molecular building blocks and length-adjustable organic linkers by stepwise synthesis. Chemistry 18, 8076–8083 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu J., et al. , Water splitting. Metal-free efficient photocatalyst for stable visible water splitting via a two-electron pathway. Science 347, 970–974 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong J., Zhang W., Ren J., Xu R., Photocatalytic reduction of CO2: a brief review on product analysis and systematic methods. Anal. Methods 5, 1086–1097 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li R., Zhang W., Zhou K., Metal-organic-framework-based catalysts for photoreduction of CO2. Adv. Mater. 30, e1705512 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou L., et al. , High light absorption and charge separation efficiency at low applied voltage from Sb-doped SnO2/BiVO4 core/shell nanorod-array photoanodes. Nano Lett. 16, 3463–3474 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou H., et al. , Photovoltaics. Interface engineering of highly efficient perovskite solar cells. Science 345, 542–546 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu Q., Zhang L., Cheng B., Fan J., Yu J., S-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst. Chem 6, 1543–1559 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang W., Mohamed A. R., Ong W.-J., Z-scheme photocatalytic systems for carbon dioxide reduction: Where are we now? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 59, 22894–22915 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong L.-Z., et al. , Stable heterometallic cluster-based organic framework catalysts for artificial photosynthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 59, 2659–2663 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang S., Guan B. Y., Lou X. W. D., Construction of ZnIn2S4-In2O3 hierarchical tubular heterostructures for efficient CO2 photoreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 5037–5040 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu Y., et al. , Tracking mechanistic pathway of photocatalytic CO2 reaction at Ni sites using operando, time-resolved spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5618–5626 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuehnel M. F., Orchard K. L., Dalle K. E., Reisner E., Selective photocatalytic CO2 reduction in water through anchoring of a molecular Ni catalyst on CdS nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 7217–7223 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukui K., Formulation of the reaction coordinate. J. Phys. Chem. 74, 4161–4163 (1970). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhao Y., Truhlar D. G., The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 120, 215–241 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weigend F., Ahlrichs R., Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 7, 3297–3305 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grimme S., Antony J., Ehrlich S., Krieg H., A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154104 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peintinger M. F., Oliveira D. V., Bredow T., Consistent Gaussian basis sets of triple-zeta valence with polarization quality for solid-state calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 34, 451–459 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frisch M. J., et al. , Gaussian 09 Revision D.01 (Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu T., Chen F., Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Legault C. Y., CYLview, 1.0b (2009). www.cylview.org. Accessed 15 September 2022.

- 41.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K., VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38, 27–28 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the manuscript and/or SI Appendix.