Abstract

Site-directed mutagenesis of the draG gene was used to generate altered forms of dinitrogenase reductase-activating glycohydrolase (DRAG) with D123A, H142L, H158N, D243G, and E279R substitutions. The amino acid residues H142 and E279 are not required either for the coordination to the metal center or for catalysis since the variants H142L and E279R retained both catalytic and electron paramagnetic resonance spectral properties similar to those of the wild-type enzyme. Since DRAG-H158N and DRAG-D243G variants lost their ability to bind Mn(II) and to catalyze the hydrolysis of the substrate, H158 and D243 residues could be involved in the coordination of the binuclear Mn(II) center in DRAG.

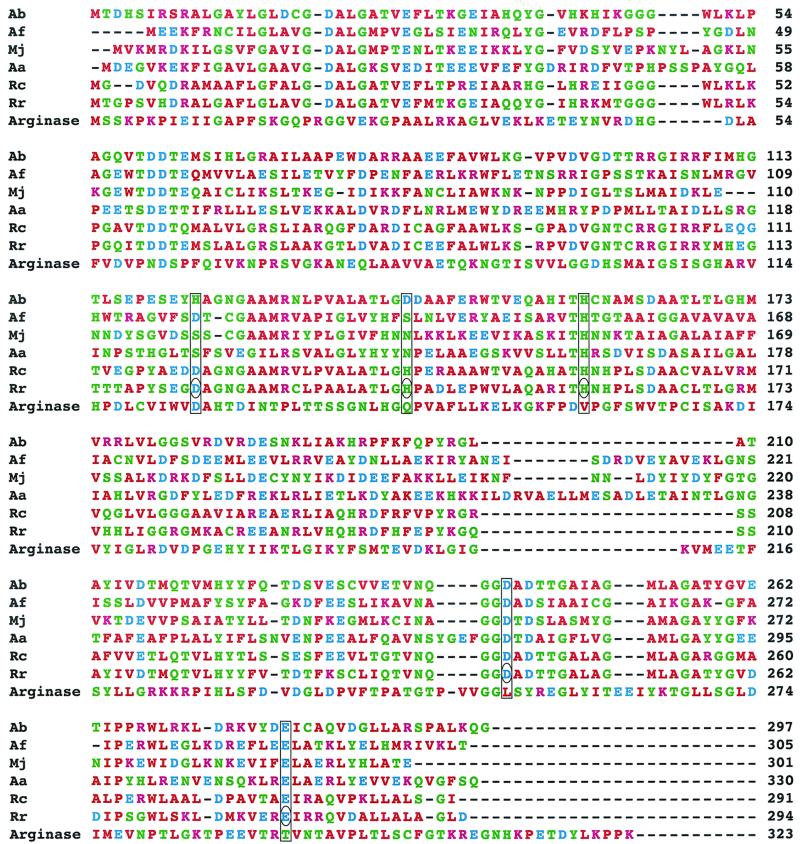

Nitrogenase activity in Rhodospirillum rubrum is regulated by reversible ADP ribosylation of Arg-101 on a single subunit of the dinitrogenase reductase homodimer under the conditions of energy stress or nitrogen sufficiency. The transfer of the ADP-ribose moiety from NAD+ to dinitrogenase reductase is catalyzed by dinitrogenase reductase ADP-ribosyltransferase (DRAT) (4). Activation of dinitrogenase reductase via glycohydrolysis of the ADP-ribosyl protein linkage is catalyzed by dinitrogenase reductase-activating glycohydrolase (DRAG) (5, 6, 9). DRAG is a 32-kDa monomeric enzyme that requires Mg-ATP and free divalent metal for its activity with ADP-ribosylated dinitrogenase reductase as the substrate and has been shown to have a binuclear Mn(II) center at the active site (1). The role of the binuclear Mn(II) center in the deribosylation of the protein substrate ADP-ribosylated dinitrogenase reductase is not well understood. Therefore, based on DRAG's sequence similarity with DRAGs from other sources and with arginase (Fig. 1), which has a binuclear Mn(II) center at the active site, an attempt has been made to understand the role of D123, H142, H158, D243, and E279 residues by site-specific mutagenesis studies.

FIG. 1.

Sequence alignment of DRAG from R. rubrum (Rr) with DRAG from Azospirillum brasilense (Ab), Archaeoglobus fulgidus (Af), Methanococcus jannaschii (Mj), Aquifex aeolicus (Aa), Rhodobacter capsulatus (Rc), and arginase from Rattus norvegicus. The amino acid residues chosen for site-directed mutagenesis in this study are circled.

The Quick Change method (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions to generate DRAG D123A, H142L, H158N, D243G, and E279R substitutions. The plasmid pYPZ148 containing a 3.3-kb PstI fragment of R. rubrum with draTGB cloned in pUC19 (2) was used as the template. After mutagenesis all draG mutations were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. Plasmids containing mutagenezied draG were digested with BsaI and BstBI, and 1.1-kb fragments of draG were subcloned into pUX115 (2) to replace the wild-type region. In these plasmids draG is expressed from the strong nifH promoter and DRAG levels are about 100-fold higher than that of the wild type. Variants of DRAG were overexpressed in R. rubrum strain UR472, a draTGB deletion mutant.

Both the wild-type DRAG and the variants were purified following the published procedure (9). Wild-type DRAG was purified from an overexpressing R. rubrum strain, UR276. Cells were broken by the French press method. DRAG activity was measured as previously described by coupling the activity of dinitrogenase reductase with the reduction of acetylene by dinitrogenase (10). DRAG activity was calculated as nanomoles of ethylene produced per milligram of protein per minute.

The quantification of Mn(II) binding to DRAG variants was determined by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) (8) using a Varian E-3 spectrometer as follows. A Mn(II) standard curve was determined for the concentration range 25 to 500 μM in 50 mM MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid)–0.2 M NaCl–2 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.0. The variants were then titrated with different concentrations of Mn(II), and the concentration of free Mn(II) was determined. Then, the concentration of bound Mn(II) was calculated from the difference between the total and free Mn(II). Finally, a Rosenthal-Scatchard plot was constructed by plotting bound Mn(II) versus free Mn(II) and the values of Bmax (maximum amount of metal bound to the enzyme) were calculated. Low temperature X-band EPR spectra were recorded with a Varian E-15 EPR spectrometer equipped with an Oxford Instruments Cryostat. Samples for EPR spectroscopy were prepared by concentrating the enzyme with a Pall Filtron Microconcentrator to 10 to 16 mg/ml in 50 mM MOPS–0.2 M NaCl–2 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.0. Then, MnCl2 was added to a concentration of 0.5 mM to activate the enzyme.

Wild-type DRAG and the variants were purified according to the published procedure, and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis of purified variants showed a single band that migrated with the wild-type DRAG at a molecular mass of 32 kDa. The purity of all protein samples was estimated as greater than 95%. The in vitro activity, Mn(II) binding, and EPR properties of the variants are summarized in Table 1. The variants DRAG-H142L and DRAG-E279R had in vitro activities similar to that of the wild-type, whereas the DRAG-D123A variant was only 70% active. The variant DRAG-H158N had only 2% of the activity of the wild-type enzyme, and the DRAG-D243G variant did not show any in vitro DRAG activity.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of in vitro activity, Mn(II) binding and EPR properties of wild-type and DRAG variant enzymesa

| Enzyme | % of wild-type activity | Mn(II) bound (mol/mol binding ratiob) | EPR spectral properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 100 | 2.0 | —c |

| DRAG-D123A | 70 | 0.4 | Absent |

| DRAG-H142L | 95 | 2.0 | Wild type |

| DRAG-H158N | 2 | 0 | Absent |

| DRAG-D243G | 0 | 0 | Absent |

| DRAG-E279R | 100 | 1.12 | Wild type |

The activity assay, Mn(II) quantification, and EPR spectral analysis were performed as described in the text.

Values are averages of two independent determinations.

See reference 1.

To demonstrate that the catalytically active wild type and the variants were structurally intact, their secondary structures were characterized by circular dichroism spectroscopy. Although small differences were observed in the circular dichroism spectra of the variants compared to that of the wild type, the intensity differences did not indicate significant changes in the secondary structures (data not shown).

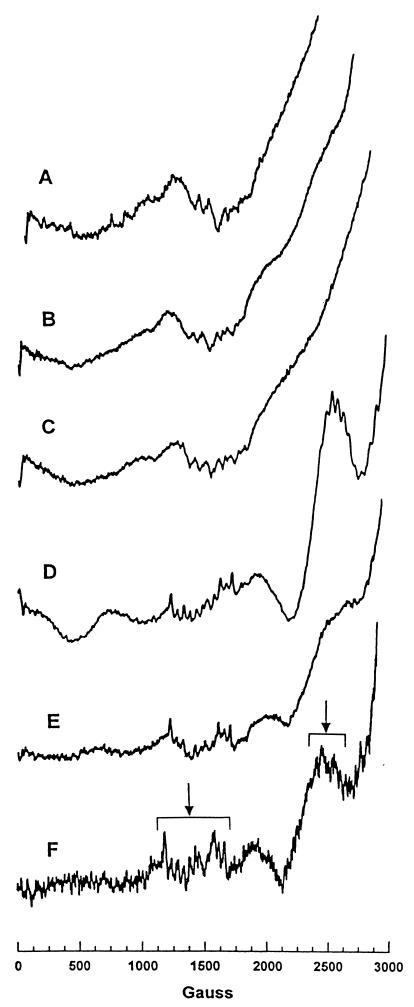

The Mn binding properties of the altered forms of DRAG were studied by EPR. The large six-line EPR signal due to free Mn(II) is quenched upon binding to DRAG, and this property was used to quantitate Mn(II) binding to DRAG variants. EPR quantitation of Mn(II) binding revealed binding ratios of 0.4, 2, and 1.2 mol/mol for the variants DRAG-D123A, DRAG-H142L, and DRAG-E279R, respectively. The variants DRAG-H158N and DRAG-D243G did not bind any detectable manganese. The EPR spectra of DRAG-H142L and DRAG-E279R were very similar to that of the wild type (Fig. 2 [compare the spectra F, E, and D]) and showed the characteristic 11-line 55Mn hyperfine spectra centered at 1,400 and 2,800 G with the 45-G spacing typical of exchange-coupled Mn(II) pairs.

FIG. 2.

Low-temperature EPR spectra of DRAG-D243G (A), DRAG-H158N (B), DRAG-D123A (C), DRAG-E279R (D), and DRAG-H142L (E) variants and wild-type DRAG (F). Spectra were recorded at 4.2 K. Each sample contains 200 μl of enzyme solution (10 to 16 mg/ml) in 50 mM MOPS–0.2 M NaCl, pH 7.0. The spectral features characteristic of a ligand-bridged binuclear Mn(II)-Mn(II) cluster centered at 1,400 and 2,800 G are indicated by arrows.

The variant DRAG-E279R with full in vitro DRAG activity bound only 1.2 mol of Mn(II)/mol of enzyme. EPR analysis of the sample without adding exogenous Mn(II) did not show the presence of any bound Mn(II); thus, DRAG-E279R does not contain tightly bound Mn as isolated. The variant DRAG-D123A bound only 0.4 mol of Mn(II)/mol of enzyme although exhibiting 70% in vitro DRAG activity. Addition of ADP-ribosylated dinitrogenase reductase (the substrate) to the sample failed either to increase the affinity for Mn(II) or to restore the binuclear metal signal. The ambiguity in metal binding properties of these two variants could be due to (i) nonspecific binding of some other metal at the active site or (ii) differences in the experimental conditions used in the activity assay and the metal binding experiments, or it could be due to both. The amino acid residues H142 and E279 cannot be critical for the coordination to binuclear Mn(II) center or for catalysis since the variants DRAG-H142L and DRAG-E279R retained both catalytic and EPR spectral properties similar to that of the wild-type enzyme. Since DRAG-H158N and DRAG-D243G variants lack the ability to bind Mn(II) or to catalyze hydrolysis of the substrate, the ADP-ribosylated dinitrogenase reductase, we propose that residues H158 and D243 could be involved in the coordination of the binuclear Mn(II) center in DRAG from R. rubrum. These observations suggest that although DRAG has some sequence similarity with arginase, for which the structure (3) is known, the environment of the binuclear Mn site in the two enzymes is very different.

Although DRAG can also be activated in vitro by Fe2+ (2.5 mM), Mg2+, and Co3+ (>20 mM) (7), Mn2+ (1 mM) is still thought to be the physiological factor since Mn2+ binds more tightly to the enzyme compared to other metals. However, neither the nature of metal used in vivo nor the role of the binuclear metal center in the hydrolytic deribosylation reaction of the protein substrate ADP-ribosylated dinitrogenase reductase is understood. Structure-function analysis of the binuclear metal center of DRAG enzyme is the focus of our ongoing crystallographic studies.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to George Reed for advice and for the use of EPR facilities. We thank Edward Pohlmann for his help.

R.R.P. was supported by NIH grant GM35759. This work was supported by NIH grant GM J4910 to P.W.L.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antharavally B S, Poyner R R, Ludden P W. EPR spectral evidence for a binuclear Mn(II) center in dinitrogenase reductase-activating glycohydrolase from Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:8897–8898. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grunwald S K, Lies D P, Roberts G P, Ludden P W. Posttranslational regulation of nitrogenase in Rhodospirillum rubrum strains overexpressing the regulatory enzymes dinitrogenase reductase ADP-ribosyltransferase and dinitrogenase reductase activating glycohydrolase. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:628–635. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.628-635.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanyo Z F, Scolnick L R, Ash D E, Christianson D W. Structure of a unique binuclear manganese cluster in arginase. Nature. 1996;383:554–557. doi: 10.1038/383554a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowery R G, Ludden P W. Purification and properties of dinitrogenase reductase ADP-ribosyltransferase from the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:16714–16719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludden P W, Burris R H. Activating factor for the iron protein of nitrogenase from Rhodospirillum rubrum. Science. 1976;194:424–426. doi: 10.1126/science.824729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nielsen G M, Bao Y, Roberts G P, Ludden P W. Purification and characterization of an oxygen-stable form of dinitrogenase reductase-activating glycohydrolase from Rhodospirillum rubrum. Biochem J. 1994;302:801–806. doi: 10.1042/bj3020801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nordlund S, Noren A. Dependence on divalent cations on the activation of inactive Fe-protein of nitrogenase from Rhodospirillum rubrum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;791:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reed G H, Markham G D. EPR of Mn(II) complexes with enzymes and other proteins. Biol Magn Reson. 1984;6:73–142. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saari L L, Triplett E W, Ludden P W. Purification and properties of the activating enzyme for iron protein of nitrogenase from the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:15502–15508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stewart W P D, Fitzgerald G P, Burris R H. In situ studies on N2 fixation using the acetylene reduction technique. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1967;58:2071–2078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.5.2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]