Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study is to examine where and with whom adolescents spent time during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic compared to 2019.

Methods

Time diary data from the May 2019 to December 2020 waves of the American Time Use Survey were used to examine trends in where and with whom a sample of individuals aged 15–18 years (N = 437) spent their time.

Results

Only 13% of adolescents spent any time at school on a given day during the pandemic (May-December 2020), compared to 36% in the same period in 2019. Average time with friends decreased by 28%. Over the 7.5-month period, this amounts to an average of 204 fewer hours/34 fewer days in school and 86 fewer hours with friends. Time spent sleeping or sleepless did not change.

Discussion

Time at school and with friends decreased substantially during the first months of the pandemic.

Keywords: Time use, COVID-19 pandemic, School closure

Implications and Contribution.

This study provides nationally representative evidence that where and with whom adolescents aged 15–18 years spent their time changed dramatically from 2019 to 2020. The proportions of adolescents spending any time at school, not at home, or with nonhousehold individuals were substantially lower in 2020.

See Related Editorial on p.173

How, where, and with whom individuals spent their time changed dramatically in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Adults increased their total awake time at home by more than 2.1 hours and averaged more time alone and less time with nonhousehold individuals in 2020 compared to 2019 [1], but the effects of the pandemic on how, where, and with whom adolescents spent their time are less understood.

In March 2020, nearly all US K-12 schools closed, and in most states remained closed through fall 2020 [2]. High school closures in Switzerland led to an increase in adolescents’ sleep by about 75 minutes/day; this increase was associated with improved health measures but also increased psychological distress during the pandemic’s early months [3]. In the United States, pandemic-related stressors such as community lockdowns and school closures were linked to poorer sleep quality among adolescents [4], and sleep problems and more screen time were associated with increased distress [5].

Research suggests that the vast majority of adolescents engaged in some social distancing during the first weeks of the pandemic [6], but adherence to public health recommendations may have waned as the pandemic continued [7]. Because adolescence is a period during which autonomy and peers are particularly important [8], the time use of adolescents in the pandemic warrants greater examination.

Methods

This study used data from the annual, cross-sectional American Time Use Survey (ATUS) [9,10]. Administered by the Bureau of Labor and Statistics (BLS), the ATUS collects 24-hour retrospective time diaries from a nationally representative sample of individuals aged 15 or older. ATUS respondents are interviewed about how they spent their time, their physical locations, and the physical presence of other people on the day prior. The BLS paused data collection from March 18 to May 9, 2020 because of the pandemic. The ATUS is a deidentified, publicly available data, not requiring institutional review board approval.

We investigated trends in self-reported data for respondents aged 15–18 interviewed in January 1, 2019 to March 17, 2020 (N = 398) and those interviewed in May 10, 2020 to December 31, 2020 (N = 241). We then focused on a subsample of those interviewed in the same months as the beginning of the pandemic (May 10, 2019 to December 31, 2019; N = 196) to compare the total number of minutes and binary measures of activities for time at locations other than home (including school), with nonhousehold people (including friends), sleeping, and sleeplessness pre- and during the pandemic.

Results

Table 1 shows that, on average, adolescents’ time spent outside of the home (Outside of the home refers to locations other than the respondent’s home at location that may be either inside or outside of a building.) or with nonhousehold individuals decreased dramatically during the first months of the pandemic (See Figure A1 online for an arrow plot of changes in sample composition and time use pre- v. during pandemic.). Although in May-December 2019 adolescents spent an average of 345 minutes a day (standard deviation [SD] = 274; median = 300) outside of the home, they did so for 205 minutes a day (SD = 255; median = 90) in May-December 2020 (a 41% decrease). This was driven by less time at school; in May-December 2019, adolescents averaged about 77 minutes a day (SD = 154) at school, but about one-third that time—just 25 minutes—in the same period in 2020 (SD = 100), when only 13% spent any time at school. Similarly, adolescents spent about an hour less with nonhousehold individuals (a 24% decrease), particularly with friends; average time with friends decreased from 80 to 58 minutes (a 28% decrease). In contrast, average time spent sleeping and sleepless remained stable (sleep time medians = 600 and 580) (Despite seeming high in both periods, means of time spent sleeping are consistent with estimates reported in other studies derived from time diary data. It is possible that respondents overreport sleep time as they include time spent in bed doing other activities, like reading, watching tv, and using social media [[13], [14], [15]].).

Table 1.

Weighted descriptive statistics: background characteristics and time use for sample aged 15–18 (N = 437)

| Same period pre-pandemic: May 10, 2019 to December 31, 2019 | During pandemic: May 10, 2020 to December 31, 2020 | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Background characteristics | (%) | (%) | (pp) |

| Male | 51.0 | 49.0 | −2.0 |

| White or other | 60.6 | 63.3 | 2.7 |

| Black | 9.7 | 10.0 | 0.3 |

| Hispanic | 29.6 | 26.7 | −2.9 |

| Employed part- or full-time | 26.8 | 25.4 | −1.4 |

| <200% FPL | 34.3 | 28.5 | −5.8 |

| Mean FPL | 318.9 | 354.8 | 35.9∗ |

| Mean age (years) | 16.7 | 16.5 | −0.2 |

| Time use | |||

| Percent who spent any time | (%) | (%) | (pp) |

| At school | 35.8 (0.5) | 13.4 (0.4) | −22.4∗∗∗ |

| Outside of the home | 85.5 (0.3) | 64.5 (0.5) | −21.0∗∗∗ |

| With nonhousehold person | 71.4 (0.4) | 55.0 (0.5) | −16.4∗∗∗ |

| With friends | 38.5 (0.5) | 19.4 (0.4) | −19.1∗∗∗ |

| Sleeplessness | 7.6 (0.3) | 8.0 (0.3) | 0.4 |

| Average minutes per day spent | (minutes) | (minutes) | (minutes) |

| At school | 77 (154) | 25 (100) | −52∗∗∗ |

| Outside of the home | 345 (274) | 205 (255) | −139∗∗∗ |

| With nonhousehold person | 235 (251) | 179 (233) | −56∗ |

| With friends | 80 (154) | 58 (161) | −22 |

| Sleeping | 592 (132) | 589 (136) | −3 |

| Sleepless | 5 (21) | 3 (13) | −2 |

| N | 196 | 241 |

Authors’ analysis using data from the 2019 and 2020 waves of the ATUS. Figures use ATUS weights and are nationally representative. Pre-pandemic includes data collected in May-December of 2019 and during pandemic includes data collected in May-December of 2020 to provide comparable time periods and seasons. Percent of adolescents aged 15–18 years who spent any time at school, outside of their home, with nonhousehold individuals, and with friends and average number of minutes per day adolescents aged 15–18 years spent at school, outside of their home, with nonhousehold individuals, and with friends in pre- and during the pandemic. ∗∗∗p < .01 and ∗p < .1 signify significant differences pre-pandemic versus during pandemic calculated using t-tests. Analyses conducted with regressions produced similar significant differences (results available upon request). See Figure A1 for an arrow plot of the information provided in Table 1.

ATUS = American Time Use Survey; FPL = Federal Poverty Level.

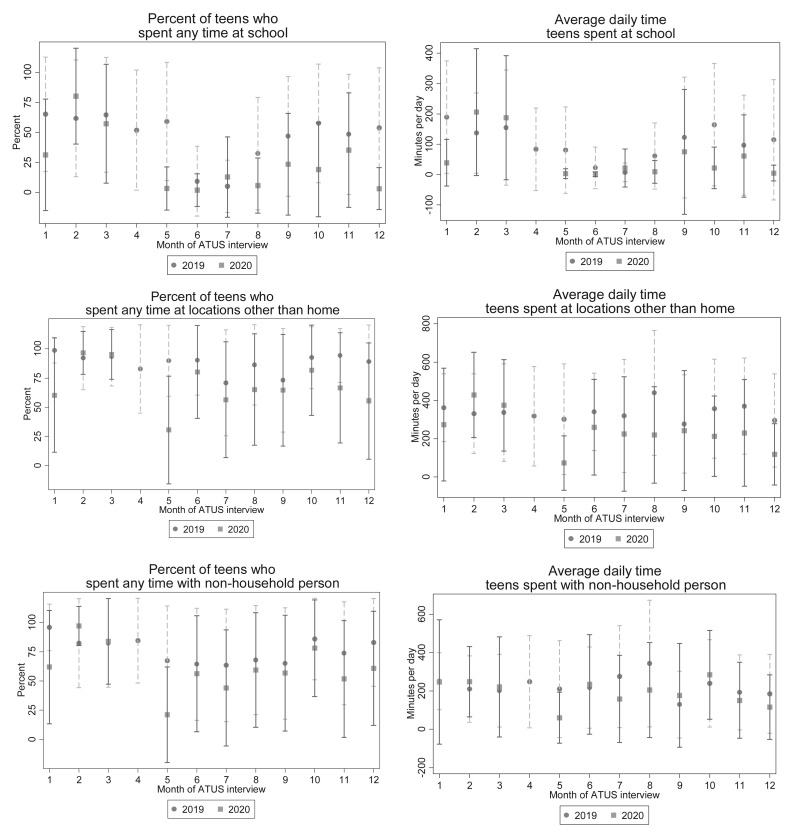

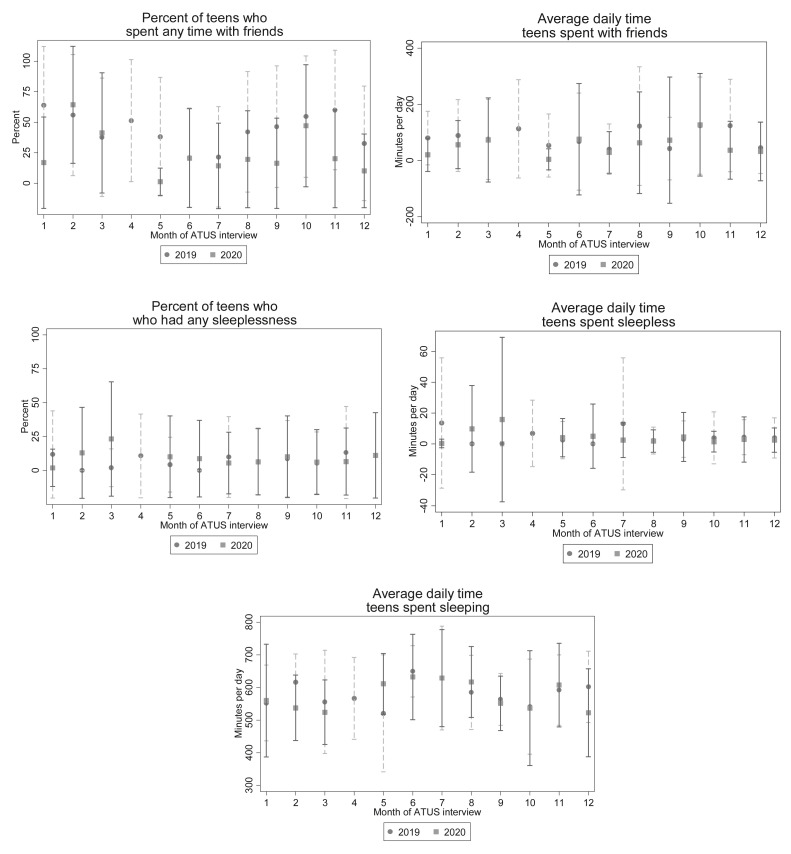

Figure 1 displays the means and SDs for the number of minutes and percent of individuals spending any time in an activity by month for January 2019 to December 2020. The distributions overlap across 2019 and 2020, but means for time spent at school, at any location outside of the home, and with nonhousehold individuals were lower in 2020 relative to 2019, particularly in May 2020. Notably, the average time and the percent of adolescents in school increased in September and decreased again in October such that means in December 2020 hovered close to zero.

Figure 1.

Percent who spent any time and average number of minutes per day adolescents aged 15–18 years spent at school, at locations other than their homes, with nonhousehold individuals, and sleeping from January 2019 to December 2020 (N = 639). Authors’ analysis using data from the 2019 and 2020 waves of the ATUS. Figures use ATUS weights and are nationally representative. The gap in April 2020 data represents a pause in data collection in March 18, 2020 to May 9, 2020. March 2020 figures represent reports gathered prior to March 18 and May 2020 figures represent reports gathered after May 9. ATUS = American Time Use Survey.

Discussion

Understanding how adolescents spend time is key to developing strategies that support their well-being and mitigate the harms of the pandemic. This study finds that where and with whom adolescents spent time in 2020 and 2019 were dramatically different, likely due to virtual schooling and public health measures. The proportion of adolescents aged 15–18 who spent any time at locations other than home decreased by 21 percentage points in spring, summer, and fall of 2020 relative to the same period in 2019 (86% vs. 65%). Much of this decrease was driven by less time at school, which decreased by one-third. With whom adolescents spent time also changed. The proportion of adolescents spending any time with friends was half of what it was in 2019, and the average time spent with friends decreased by more than one-quarter. Over the 7.5-month period, this amounts to an average of 203.7 fewer hours or 33.9 fewer days at school and 86.2 fewer hours with friends relative to 2019.

Given the importance of school and peers during adolescence, these dramatic changes in time use may have important implications for well-being. School closures were associated with learning loss [11], and time out of school may have further harmful implications for children facing adversity for whom schools serve as safe havens. The lack of in-person time with peers may exacerbate mental health problems, now at crisis levels [12].

Unlike previous research [3], however, we found sleep time and sleeplessness to be similar to pre-pandemic figures. It is possible the pandemic had a short-term, temporary effect on sleep, but the brief pause in data collection prevents our analysis of this immediate effect, or that the self-reported measures here do not capture these changes.

Data limitations prevent the exploration of whether adolescents’ time was spent outdoors, in small groups, or physically distanced and how time use patterns varied by individual characteristics like race and income. Further research is needed to explore these changes and their implications for well-being.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dave Marcotte for his insights and Sarah Timmerman for research assistance on this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.08.018.

Funding Sources

None.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.American Time Use Survey — May to December 2019 and 2020 results. ATUS News Release.

- 2.Center for Reinventing Public Education School district responses to COVID-19 closures. 2021. https://www.crpe.org/current-research/covid-19-school-closures Available at:

- 3.Albrecht J.N., Werner H., Rieger N., et al. Association of adolescent sleep duration during COVID pandemic high school closure. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:1–12. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer C.A., Oosterhoff B., Massey A., Bawden H. Daily Associations between adolescent sleep and socioemotional experiences during an ongoing stressor. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70:970–977. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2022.01.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiss O., Alzueta E., Yuksel D., et al. The pandemic’s toll on young adolescents: Prevention and intervention targets to preserve their mental health. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70:387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oosterhoff B., Palmer C.A., Wilson J., Shook N. Adolescents’ Motivations to engage in social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Associations with mental and social health. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murillo-Llorente M.T., Perez-Bermejo M. COVID-19: Social irresponsibility of teenagers towards the second wave in Spain. J Epidemiol. 2020;30:483. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20200360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrews J.L., Foulkes L., Blakemore S.J. Peer influence in adolescence: Public-health implications for COVID-19. Trends Cogn Sci. 2020;24:585–587. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. American Time Use Survey.

- 10.Hofferth S.L., Flood S.M., Sobek M. University of Maryland and Minneapolis, MN; College Park, MD: 2018. American Time Use Survey data extract builder: Version 2.7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorn E., Hancock B., Sarakatsannis J., Viruleg E. COVID-19 and Education: The lingering effects of unfinished learning. 2021. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-education-the-lingering-effects-of-unfinished-learning Available at:

- 12.The U.S. Surgeon General Protecting youth mental health. 2021. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-youth-mental-health-advisory.pdf Available at:

- 13.Basner M., Dinges D.F. Sleep duration in the United States 2003-2016: First signs of success in the fight against sleep deficiency? Sleep. 2018;41:1–16. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basner M., Fomberstein K.M., Razavi F.M., et al. American Time Use Survey: Sleep time and its relationship to waking activities. Sleep. 2007;30:1085–1095. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Charts by topic: Sleep. American Time Use Survey. 2016. https://www.bls.gov/tus/charts/sleep.htm Available at:

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.