Abstract

Background:

Sexual child abuse is a form of anti-social behavior with the children that cause potential harm to the health, development and dignity of the child. Knowledge of children about these issues can help to protect themselves against sexual abuse. This study aimed to review systematically available documents about the importance of knowledge on self-protection of sexual abuse in children.

Methods:

In this systematic review, “sexual abuse”, “self-protection” and “knowledge” were searched in Scopus, Google Scholar, Ovid, PubMed, and Science Direct as the search words, and after considering the inclusion criteria and excluding irrelevant articles, the relevant articles were included for data extraction. In the included studies, children were educated about sexual abuse, and questionnaires were designed to compare the impact of education and the level of knowledge in children before and after education.

Results:

Overall, 19 articles with overall 6582 children were found that were published from 1987–2020. The main awareness of children was from parents, educators and then the media. Age of the child, education level of family, good relationship between family members, adequate education by school teachers in the form of educational programs and even media play an important role in increasing knowledge of children about sexual abuse. Education to children, on average, led to 77.43% more awareness and as a results self-protection against sexual abuse and rape.

Conclusion:

Insufficient education or lack of knowledge about sexual abuse is a critical issue in children. Therefore, it is necessary to design educational programs to increase their knowledge about sexual abuse and strategies for self-protection in this age group.

Keywords: Sexual abuse, Self-protection, Knowledge, Children, Child abuse, Systematic review

Introduction

Child abuse is a problem that has always been an indecent behavior in human societies. Children, who are more vulnerable to this issue, are always at risk. Despite the efforts of child support organizations to solve this problem, sexual harassment of children is a global issue (1). Today, despite the scientific and cultural advances of societies in addition to knowledge of parents and families, the number of reported social harms to children continues to increase, led many countries and international organizations to pay more attention to children and their problems and to seek solutions to reduce these issues (2). Child abuse is defined as a behavior that led to harm for a child and typically includes all types of physical, sexual, emotional, and commercial abuse, which may lead to potential harm to the health, development and dignity of the child (1, 2).

Child sexual abuse means any sexual contact or interaction with a child by an adult or adolescent who has reached puberty. It may range from sexual intercourse to showing an adult’s genitals to a child, forcing a child to show his or her body, sex jokes, any violation of the child’s privacy, use of the child in pornographic films and magazines, and forcing the child to engage in any form of prostitution (3). In a simpler term, sexual abuse of a child is a child’s involvement in sexual activities that he/she cannot understand and is not ready for it in terms of physical and sexual development and is not satisfied with the involvement. Sexual abuse may occur for a single time, but it is usually chronic and occurs frequently. Most perpetrators are adults (over 18 yr old) who are familiar with the child (relatives or family friends) and usually abuse them by pressuring and using force or by deceiving and seducing the child (2). The age of the victims varies from newborns to 18 yr, but it is often at age of 8 to 11 yr and the average age is 9 years. Although strangers also commit such acts, but 60% of children are sexually abused by familiar and trusted family members and 30% to 40% by relatives (4).

The consequences of child abuse can be severe, leading to both short- and long-term effects on physical, social, and psychological functioning (4, 5). Short-term effects may include medical problems, neurological, cognitive, behavioral-social, emotional, and psychiatric disorders, such as psychosis, aggression, antisocial behaviors, destructive behavioral disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder (6). Long-term psychological consequences include depression, anxiety, physical complaints, drug use, and an increased risk of crime in older children (7). Education and training of children to increase their awareness about sexual abuse can minimize the incidence of abuse in children, which may subsequently reduce the risk of emotional and psychiatric disorders in the future. Accordingly, knowledge and awareness include acquiring information about the sexual abuse, behaviors of rapist or sexual predators, prevention programs, and empowerment skills (8).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the significance of knowledge, and the importance of the source of acquiring awareness about the sexual abuse and strategies for self-protection against sexual abuse in childhood. Self-protection can be defined as every activity by the child that disallows the abuse or shows discomfort of the child, leading to termination of abuse by the sexual assailant (9).

Materials and Methods

Methodology and selection criteria

A systematic search was performed in Scopus, Google Scholar, Ovid, PubMed, and Science Direct in Nov 2021 to evaluate the rate of knowledge about sexual abuse among children. For this purpose, we followed PICO framework for qualitative reviews and used “sexual abuse”, “self-protection” and “knowledge” including all their equivalent terms in the title, keywords, and abstracts of articles. The records were limited to original articles with English language. The search method using the AND/OR logical operators was as follow: (((Sexual abuse OR sexual harassment OR sexual molestation OR Sexual Violence) AND (self-care OR self-protection OR self-care OR self-protection)) AND (knowledge OR awareness OR information)) AND (children OR child). To include almost all potentially eligible documents, not very strict inclusion criteria were defined, but letters, and review articles were excluded from further assessment. All procedures including article search and selection, in addition to data extraction were performed by two authors independently, as recommended by PRISMA Checklist 2009 for reporting systematic reviews. Moreover, any possible disagreements between the authors were checked and resolved in each step by a Fifth author.

Data collection and the variable in the included literature

All necessary data including the bibliographic information, number and the mean age of participants in each study were recorded. Moreover, the type of sexual abuse, knowledge rate of children and the source of knowledge that they acquired were recorded and used for qualitative data description.

Quality assessment of included studies

Since no single types of studies were included in this literature review, quality assessment was performed according to an appropriate quality scale of each type of study. Accordingly, the CARE (Case Report guidelines) Checklist (2016) was used to evaluate the quality of case reports. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) quality assessment scale specialized for observational and cross-sectional studies was used to evaluate the quality of these observational studies. And Newcastle-Ottawa scoring tool was used for quality assessment of included controlled trials. The questions of these scores focus on the key concepts for evaluating the validity of a study, the risk of bias, measurement, follow up and confounding factors, and finally describe the quality of individual studies as a quality number. Accordingly, the CARE score has 14 items and a report can obtain up to 28 score. The NIH checklist includes 14 items and describes the quality of individual studies as a number of up to 14. Newcastle-Ottawa scoring scale has three different parts including “selection”, “comparability”, and “outcome” with overall 8 questions, and every study can obtain maximum 9 stars based on the items in this scale. The questions of CARE Checklist, Newcastle-Ottawa, and NIH quality assessment are provided as supplementary data.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Research and Ethics Council of Iran University of Medical. Sciences (code: IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1399.193).

Results

Study selection (flow chart)

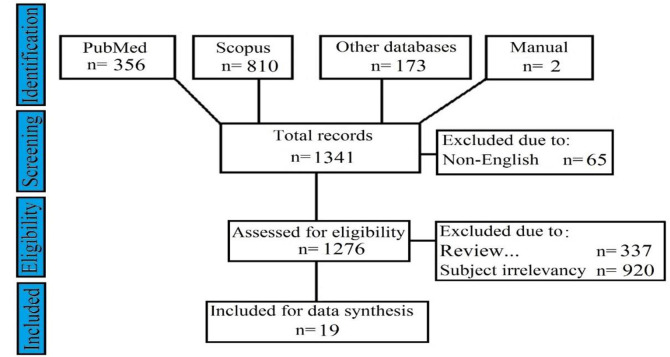

In this study, we systematically reviewed studies that measured the level and impact of children and adolescents’ awareness and knowledge on protection against sexual abuse. Overall, 1341 articles were collected, of which only 19 relevant documents with study population consisted of 6582 children with age range of 4–16 were included. The included articles were published between 1987 and 2020. Selection process of included articles is depicted in Fig. 1. Of these participants 3030 were boys and 3552 were girls. Statistically, gender had no effect on the main findings and the difference in number of male or female participants was not significant.

Fig. 1:

Flow diagram of article selection procedure

Quality assessment

Quality assessment of articles also showed that the included article have good quality of reporting, which is demonstrated in Table 1.

Table 1:

Quality assessment of included articles

| No | Reference | Checklist | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hornor et al (2020) | NIH Checklist | 9/14 |

| 2 | Khoori et al (2020) | NIH Checklist | 12/14 |

| 3 | Wulandari et al (2020) | NIH Checklist | 10/14 |

| 4 | Urbann et al (2020) | Newcastle-Ottawa | 8/9 |

| 5 | Huang et al (2020) | NIH Checklist | 10/14 |

| 6 | Jordan et al (2019) | NIH Checklist | 8/14 |

| 7 | Ha Ngoc et al (2019) | NIH Checklist | 13/14 |

| 8 | Bustamante et al (2019) | Newcastle-Ottawa | 7/9 |

| 9 | Czerwinski et al (2018) | NIH Checklist | 12/14 |

| 10 | Alsaif et al (2018) | The CARE Checklist | 17/28 |

| 11 | Jin et al (2017) | Newcastle-Ottawa | 13/14 |

| 12 | Yu et al (2017) | NIH Checklist | 8/14 |

| 13 | Jin et al (2016) | NIH Checklist | 10/14 |

| 14 | Zhan et al (2013) | NIH Checklist | 10/14 |

| 15 | Chen et al (2012) | NIH Checklist | 11/14 |

| 16 | Tang et al (1999) | NIH Checklist | 9/14 |

| 17 | Finkelhor et al (1995) | NIH Checklist | 10/14 |

| 18 | Wurtele et al (1992) | NIH Checklist | 11/14 |

| 19 | Sigurdson et al (1987) | NIH Checklist | 9/14 |

Predisposing factors of child abuse

Numerous factors play role in child abuse, the most important of which are inappropriate and stressful relationships and behaviors of parents at home, economic and cultural problems, child personality traits, and lack of parenting skills by parents. However, the most important item can be the lack of proper sex education in children (10). According to various studies, low level of parental literacy, overcrowding of families, addiction, inefficiency of parents in appropriate controlling the behavior of family members, limited social relationships, social isolation of the family, and conflict among family members are other predisposing factors for child abuse (11, 12).

Study findings

Children in the included studies have been given the necessary training to protect themselves against sexual abuse. The training in the articles included knowledge on the correct recognition of a reasonable request to see or touch the child’s sexual organ (for example, by a doctor for treatment) or an inappropriate request by an adult or older child for sexual purpose, secret kisses or sexual intercourse with a child, methods of disagreement in cases of unreasonable sexual demands and how to deal with and prevent sexual harassment, and finally informing the parents or trusted person by the child if there are any cases of sexual harassment. These training have been provided by parents, school teachers, and sometimes movies and television programs to examine the impact of different types of training on protecting the child against rape, and to evaluate to what extent this type of training has been useful and effective.

Majority of studies used related questionnaires such as ‘What If’ Situations Test (WIST), approved by the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. The questionnaire includes the following items: appropriate, inappropriate, and skills such as say, do, tell and report, which includes a number of questions about how to respond in a hypothetical sexual abuse situation. If the child’s answer to these items is “no”, it will be checked how his/her ability to prevent unreasonable requests and self-protection has been achieved and how long the child has been educated by parents or educators. About 43% of children recognize a reasonable request to touch sexual organ (E.g.examination by a doctor) and also recognize an unreasonable request. Among the students participating in a study, 2% received excellent knowledge grades and knew how to recognize, deal with and prevent sexual abuse, and majority of children had acceptable knowledge, but 21% of them did not have knowledge for self-protection against any types of sexual abuse (13).

The WIST test showed that there is a gender difference in the response to some of the items in this questionnaire and boys had better knowledge than girls about a reasonable request. However, there is no significant difference between the boys and girls in identifying unreasonable sexual touch. There was also a significant difference in resistance to unreasonable demands between the boys and girls, with higher rate of resistance to sexual demands in girls. Moreover, about 58% of girls talk about this issue with their trusted people (13). Children were questioned whether an adult or older child touched the child’s genitals, or have been asked to touch the sexual organ of an older person. Children aged 9 to 11 yr had more knowledge than children aged 6 to 8 yr, except in cases where the child had obtained the necessary knowledge from the parents, in which boys had more knowledge about sexual abuse and strategies for self-protection (14).

Another study on deaf people revealed that 56.9% of these children recognized a reasonable request from a doctor, and similar to other studies, boys performed better than girls in identifying a reasonable request (70% vs. 38%), which was statistically significant. In addition, 33% of these deaf children leave the scene and report to parents whenever every person show their sexual organ to them, and this knowledge and behavior was more prominent in girls than in boys (52% vs. 20%). However, the results were not satisfactory and children did not response completely to the questionnaire and only 5.9% of them answered all the items correctly (15). Another study using the WIST questionnaire performed on mentally retarded girls found that 93.5% of these children could identify reasonable and unreasonable requests, but only 24% fully responded to all 24 questions. Children with mental disabilities do not have enough knowledge regarding sexual issues and were unfamiliar with self-care strategies. Only 61% of these children had information about sexual abuse, and 16.9% of them did not recognize sexual touch (16). Another study reported that 30% of children enrolled in the study had knowledge about rape and sexual abuse. Besides, 60% of the children in the study stated that they had experienced a suspicious touch from an older person in the past 6 months. However, after completing the school training for these children, the results were surprisingly different, and the majority of children (88.8%) were able to identify reasonable and unreasonable requests and gained the necessary knowledge about self-protection against any unreasonable requests for body touch by an adult (10).

Children who participated in the “STARK mit SAM” (Strong with Sam, SmS) sexual abuse training program showed an increase in knowledge about sexual abuse with no significant difference between the different age group or between boys and girls. The study was conducted as a pre-test post-test with the aim of evaluating the practicality of sexual abuse prevention program for the deaf children. SmS is an effective sexual abuse prevention program for deaf and hard of hearing children, provided without causing anxiety in these children. Evaluation of the effectiveness of picture books in preventing sexual abuse in children demonstrated that the skill of identifying sexual abuse was significantly higher among the children in the test group compared to control group (P<.001) (17).

97.5% (n= 117) of the participants in the experimental group did not consider it appropriate to be touch by an older person, while in the control group only 63.33% (n=38) of the participants responded correctly. Moreover, refusal skill was significantly higher among children who were trained with picture book than those who were not (P<.001) (9).

In addition to school programs, a very small number of children (4%) reported receiving education programs elsewhere, such as churches, although most of these children had already participated in a school programs. Non-school programs for training children accounted for only 1% of the total curriculum (18). Educational programs to teach children how to protect themselves from sexual abuse can significantly reduce the rate of rape and abuse among children. In addition, education from parents, school teachers, church and religious settings, and the media can be an effective intervention in children’s learning to protect themselves against rape (11, 19,–26) (Table 2).

Table 2:

Demographic information, source of knowledge and the rate of awareness among children

| No | Reference | Participants (female/male) | Age | Study type | Data type | Knowledge rate or mean pre-test vs. post-test) | Type of knowledge | Source of knowledge | Sexual abuse type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hornor et al (2020) (27) | 223 (188/35) | 14.29 | Observational | Electronic questionnaire | 87% | Human labor and sex trafficking | Media, family/friends | Alleged sexual abuse |

| 2 | Khoori et al (2020) (24) | 56 (56/-) | 5–8 | A cross-sectional study | WIST, PSQ | 4.73±3.04 Vs. 8.15±2.92 | Body safety training | Mother-daughter pairs | Appropriate-touch requests |

| 3 | Wulandari et al (2020) (13) | 301 (163/138) | 10–11 | Observational | WIST questionnaire | 92% | Self-protection, appropriate touching | School | Touch children’s genitals |

| 4 | Urbann et al (2020) (17) | 92 DHH Children (42/50) | 8–12 | Randomly control trial | WIST Questionnaire | 50% vs. 72% | Self-protection, anxiety | Family, parents | Touching |

| 5 | Huang et al (2020) (28) | 180 (93/87) | 5–6 | Observational | WIST Questionnaire | 63.33% vs. 97.5% | Recognize and refuse touch | Picture Books, parents | Touching |

| 6 | Jordan et al (2019) (10) | 36 (36/-) | 5–10 | Observational | Questionnaire | 88% vs. 62.2% | Educational program, confidence | physicians, nurses, and a consultant | Alleged sexual abuse |

| 7 | Ha Ngoc et al (2019) (9) | 800 (469/331) | 9–15 | A cross-sectional study | Attitude questionnaire | 97.13 % | Self-protection | School and home | Touch, kiss, hug |

| 8 | Bustamante et al (2019) (19) | 939 (488/451) | 6–14 | Cluster-randomized control trial | Questionnaire | 69.6% vs. 76.7% | Self-protection | School and home | Appropriate and inappropriate touching |

| 9 | Czerwinski et al (2018) (22) | 291(151/140) | 8–12 | A cross-sectional study | CKAQ | 39.15±8.74 vs. 45.23±7.65 | Self-protection skills | Theater-based intervention | Anxiety and touch aversion of the children |

| 10 | Alsaif et al (2018) (25) | 2 (2/-) | 5 and 9 | Case report | Questionnaire | - | Sexual education | Parents | Hurt her private parts |

| 11 | Jin et al (2017) (23) | 484 (259/225) | 6–11 | A cross-sectional study | BST program | 6.69±2.36 Vs. 9.24±1.25 | Self-protection skills | Teacher and parents | Appropriate/inappropriate touch |

| 12 | Yu et al (2017) (15) | 51 (21/30) | 10–16 | Observational | Questionnaire | 52.9% vs. 39.2% | Self-protection | Parent, trustworthy adults | Abusive situation |

| 13 | Jin et al (2016) (14) | 559 (293/266) | 6–11 | Observational | Questionnaire | 80% vs. 60% | Self-protection | Parents | Touch private parts |

| 14 | Zhan et al (2013) (26) | 136 (62/74) | 3–5 | Observational | WIST, PQ and PSQ | 58% | Sexual education | Parents | Inappropriate Request and touch children’s genitals |

| 15 | Chen et al (2012) (21) | 46 (22/24) | 6–13 | A cross-sectional study | CSKQ | 61.24% vs. 75.38 | Self-protection skills | School, parents | Kiss, inappropriate touching |

| CASSQ | 77.16% vs. 89.78 | ||||||||

| WIST | 86.23% vs.87.9% | ||||||||

| 16 | Tang et al (1999) (16) | 77 (77/-) | 11–15 | Observational | WIST, PSQ Questionnaire | 24.7% vs. 62.1% | Self-protection | Media | Look or touch one’s genitals |

| 17 | Finkelhor et al (1995) (18) | 2000 (958/1042) | 10–16 | Observational | Questionnaire and Telephone interviews | 67% | Comprehensive instruction | Parental instruction | Touching, kiss, hug |

| 18 | Wurtele et al (1992) (11) | 172 (99/73) | 4–6 | A cross-sectional study | WIST, PSQ | 3.65± 2.52 vs. 5.94±3.11 | Self-protection skills | Teachers, parents, or both | Inappropriate touch |

| 19 | Sigurdson et al (1987) (20) | 137 (73/64) | 9–13 | Observational | Personal safety questionnaire | 21.89% vs. 78.1% | Self-protection | Family theatre, films, video, booklets, pamphlets and coloring books | Kiss, inappropriate touching |

WIST: What If Situation Test, PSQ: Personal Safety Questionnaire, DHH: Deaf and Hard of Hearing Children, SMS: STARK mit SAM, CSKQ: Children’s Sexual Knowledge Questionnaire, CASSQ: Children ’S Awareness of Scary Secrets Questionnaire, CKAQ: Children’s Knowledge of Abuse Questionnaire, BST: Body Safe Training, PQ: Parents Questionnaire

Discussion

Sexual abuse of children is a global problem that can be seen all around the world in every economic, social, ethnic and educational level (3). In 2009, about 24% of child sexual abused were reported in the United States, and only in 2012, of the 936 reported child sexual abuse cases, 62 were confirmed, while many were unreported (29). Findings suggested that education to the children about sexual issues, such as sexual difference, and different kinds of sexual abuse in addition to strategies for self-protection against sexual predators can help to minimize these antisocial behaviors in a society (10). Accordingly, the results of studies evaluated in the present systematic review confirmed that improvements in knowledge and protective behaviors among children against sexual abuse is a very effective strategy to protect this age group from consequences of sexual abuse, which was consistent with other reports (30). According to our results, family and the school-based educational programs have the highest rate of successful outcomes on both knowledge and self-protection skills among children. Educational programs have positive effects, but it is also necessary to implement specific components and techniques such as social-emotional skills of children, and games or quizzes to improve the effectiveness of educational programs, indicating that individual techniques may not lead to satisfactory and effective outcomes (8).

The important thing for preventing sexual harassment in children, regardless of gender, is proper education by parents at home and educators at school (31). Over the past 30 years, a number of evaluations of prevention programs for parents and educators have been conducted.

Overall, education can lead to increased knowledge about the warning signs of abuse, appropriate ways to respond to the child who reports abuse, and information about who to talk and report about sexual abuse (32). By giving education and knowledge, children will have a correct understanding of their body. For this purpose, it is better for parents to spend more time answering the questions of their children, patiently and correctly. In previous decades, parents themselves had little knowledge about sexual abuse in children and the necessity of child’s knowledge and education programs (33). However, over time, parents also acquired knowledge about sexual abuse in children and the importance of education, emotional support to the victim, and involvement in the prevention of child abuse (34). Parents should avoid using slang words for the child’s genitals and make the child aware of any abuse so that the child fully understands the difference between an innocent and inappropriate body touch. The child should be informed that no one has the right to touch his/her body and the child is not also allowed to touch the body of another person or child. The child must learn to respond with negative answer to defend her- or himself against the inappropriate demands of other people. Family boundaries must be defined, and in the family, each person’s privacy must be respected, such as clothing, bathing, sleeping, or other personal activities. Safe environment and appropriate behaviors of family members help the child to easily share anything that causes her/him discomfort and fear with the people she/he trusts. Awareness of children about sexual issues should not be forced and should be done with care and calm constantly. The child must learn that his/her body belongs to him/her and that no one is allowed to do anything that embarrasses the child and says no firmly to any unwanted behavior. Finally, if something unwanted and upsetting happens to her/him, she/he can easily talk to the parents or trusted people and inform them about the issue (15).

Teenagers have more knowledge about sexual trafficking, and the television has a 74% effect on this awareness. Children and adolescents mainly acquired the necessary knowledge first from the media and secondly from the family (13). The age of the child, his/her ability to learn and the level of knowledge have a significant effect on identifying rape and how to protect themselves from sexual abuse (5). It is expected that the awareness given to children from all sides plays important role in protecting the child from unreasonable sexual requests. Most children are familiar with this type of relationship, but it is important to teach the child about self-protection and resistance to unreasonable touch or sexual conversation with other people (14).

Studies of exceptional children, such as hearing-impaired and mentally retarded children, have shown that hearing-impaired children have very few knowledge and skills in self-protection in relation to sexual issues. Moreover, in children with mental retardation, there is less education about sexual boundaries and these children are less aware of self-protection in relation to sexual issues. Therefore, this issue requires more education of these children, especially by the educators. Culture and even family income play an important role in better educating exceptional children, and the fact that these children need the right education program to self-protect and resist against rape and sexual abuse is non-negligible. Although the age is an important factor in child’s knowledge about sexual issues, and older children have more awareness about strategies to protect himself or herself, appropriate and friendly training of awareness from parents, the media and school educators plays a very important role in this regard (15, 16). Prevention programs as curriculum have been successful for the child to identify dangerous situations and strategies for self-protection of sexual abuse (6). Children aged 6 to 7 under training for self-protection strategies in cases of sexual abuse have a better chance of protecting themselves than those who had no training, signifying the role of education in knowledge of children. Parents, teachers, educators and those who have an educational role can play a significant role in the education of children’s sexual education through practical measures and planning (31). In this regard, there should be a good and intimate relationship between educators and students, and education should include appropriate curricula with respect to the body privacy and the ability to self-support, in addition to how to inform adults and trusted members about sexual abuse. Collectively, in addition to the family, the school also has an important role in improving the knowledge of children about sexual abuse and will help children by designing various programs aimed at teaching safety skills and personal care. The education system should teach the child how to get rid of dangerous situations and how to talk with trusted people to get advice about sexual issues (16).

Strategies to manage or primary care setting when sexual abuse is suspected in children

To prevent sexual abuse in children, several strategies are suggested. The first and most important suggested strategy is parents who should be vigilant and pay more attention to the behavioral symptoms of suspected sexual abuse in children. The following items may be considered as some of these signs. 1. Nightmares, sleep problems or fears without a clear explanation in the child, 2. Sudden changes in the child’s mood such as anger, shortness of breath or significant changes in eating habits, 3. Occurrence of childhood behaviors such as enuresis or finger sucking, 4. Refuse to be in a certain place or be alone with an adult or resist for any unknown reason, 5. Resist daily bathing and toileting, 6. Existence of sexual and scary themed images in games, paintings, and writings of the child, 7. Avoid talking about the secrets of an adult or teenager person, 8. Stomach pain and diseases for an unknown reason, 9. Repeating words that are usually used by adults for sexual organs, 10. Physical symptoms such as bruising around the mouth, and sudden pain in the genital area (35, 36).

Few numbers of studies were the major limitations of this study. In addition, sexual victims are much less reported and recorded, as a result, these numbers can only represent a small community; therefore, it is suggested to perform several well-designed population-based studies with large study participants to conclude with more reliability with minimized risk of bias.

Conclusion

Insufficient knowledge about sexual abuse in children is a problematic issue, so it seems necessary to design educational programs for the children to increase their knowledge about sexual abuse and strategies for self-protection. Given the growing number of child sexual abuse cases and the lack of awareness among children, parents, educators, and media have critical role in improving the knowledge of children and the society about the sexual abuse in children, and subsequent social and health consequences. It is important to teach the children to identify possible situations of abuse and learn to use of self-protection skills.

Journalism Ethics considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

We thanks Research Council of Iran University of Medical for financial support the Research

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Al Odhayani A, Watson WJ, Watson L. (2013). Behavioural consequences of child abuse. Can Fam Physician, 59:831–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonald KC. (2007). Child abuse: approach and management. Am Fam Physician, 75:221–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Smailes EM, et al. (2001). Childhood verbal abuse and risk for personality disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. Compr Psychiatry, 42:16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray LK, Nguyen A, Cohen JA. (2014). Child sexual abuse. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am, 23:321–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kashani JH, Daniel AE, Dandoy AC, Holcomb WR. (1992). Family violence: impact on children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 31:181–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beitchman JH, Zucker KJ, Hood JE, daCosta GA, Akman D. (1991). A review of the short-term effects of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl, 15:537–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Springer KW, Sheridan J, Kuo D, Carnes M. (2007). Long-term physical and mental health consequences of childhood physical abuse: results from a large population-based sample of men and women. Child Abuse Negl, 31:517–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gubbels J, van der Put CE, Stams GJM, Assink M. (2021). Effective Components of School-Based Prevention Programs for Child Abuse: A Meta-Analytic Review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev, 24:553–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Do HN, Nguyen HQT, Nguyen LTT, et al. (2019). Perception and Attitude about Child Sexual Abuse among Vietnamese School-Age Children. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 16(20):3973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jordan KS, Steelman SH, Leary M, et al. (2019). Pediatric Sexual Abuse: An Interprofessional Approach to Optimizing Emergency Care. J Forensic Nurs, 15:18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wurtele SK, Kast LC, Melzer AM. (1992). Sexual abuse prevention education for young children: a comparison of teachers and parents as instructors. Child Abuse Negl, 16:865–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker CK, Gleason K, Naai R, Mitchell J, Trecker C. (2012). Increasing Knowledge of Sexual Abuse. Research on Social Work Practice, 23:167–178. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wulandari MD, Hanurawan F, Chusniyah T, Sudjiono (2020). Children’s Knowledge and Skills Related to Self-Protection from Sexual Abuse in Central Java Indonesia. J Child Sex Abus, 29:499–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin Y, Chen J, Yu B. (2016). Knowledge and Skills of Sexual Abuse Prevention: A Study on School-Aged Children in Beijing, China. J Child Sex Abus, 25:686–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu B, Chen J, Jin Y, et al. (2017). The knowledge and skills related to sexual abuse prevention among Chinese children with hearing loss in Beijing. Disabil Health J, 10:344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang CS, Lee YK. (1999). Knowledge on sexual abuse and self-protection skills: a study on female Chinese adolescents with mild mental retardation. Child Abuse Negl, 23:269–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Urbann K, Bienstein P, Kaul T. (2020). The Evidence-Based Sexual Abuse Prevention Program: Strong With Sam. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ, 25:421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finkelhor D, Asdigian N, Dziuba-Leatherman J. (1995). The effectiveness of victimization prevention instruction: an evaluation of children’s responses to actual threats and assaults. Child Abuse Negl, 19:141–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bustamante G, Andrade MS, Mikesell C, et al. (2019). “I have the right to feel safe”: Evaluation of a school-based child sexual abuse prevention program in Ecuador. Child Abuse Negl, 91:31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sigurdson E, Strang M, Doig T. (1987). What do children know about preventing sexual assault? How can their awareness be increased? Can J Psychiatry, 32:551–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen YC, Fortson BL, Tseng KW. (2012). Pilot evaluation of a sexual abuse prevention program for Taiwanese children. J Child Sex Abus, 21:621–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Czerwinski F, Finne E, Alfes J, Kolip P. (2018). Effectiveness of a school-based intervention to prevent child sexual abuse-Evaluation of the German IGEL program. Child Abuse Negl, 86:109–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin Y, Chen J, Jiang Y, Yu B. (2017). Evaluation of a sexual abuse prevention education program for school-age children in China: a comparison of teachers and parents as instructors. Health Educ Res, 32:364–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khoori E, Gholamfarkhani S, Tatari M, Wurtele SK. (2020). Parents as Teachers: Mothers’ Roles in Sexual Abuse Prevention Education in Gorgan, Iran. Child Abuse Negl, 109:104695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alsaif DM, Almadani OM, Almoghannam SA, et al. (2018). Teaching children about self-protection from sexual abuse: could it be a cause for source monitoring errors and fantasy? (Two case reports). Egypt J Forensic Sci, 8:27. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang W, Chen J, Feng Y, et al. (2013). Young children’s knowledge and skills related to sexual abuse prevention: a pilot study in Beijing, China. Child Abuse Negl, 37:623–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hornor G, Sherfield J, Tscholl J. (2020). Teen Knowledge of Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children. J Pediatr Health Care, 34:239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang S, Cui C. (2020). Preventing Child Sexual Abuse Using Picture Books: The Effect of Book Character and Message Framing. J Child Sex Abus, 29:448–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Euser S, Alink LR, Pannebakker F, et al. (2013). The prevalence of child maltreatment in the Netherlands across a 5-year period. Child Abuse Negl, 37:841–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zwi KJ, Woolfenden SR, Wheeler DM, et al. (2007). School-based education programmes for the prevention of child sexual abuse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, (3):CD004380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leung H, Shek DTL, Leung E, Shek EYW. (2019). Development of Contextually-relevant Sexuality Education: Lessons from a Comprehensive Review of Adolescent Sexuality Education Across Cultures. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 16(4):621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hazzard A, Webb C, Kleemeier C, Angert L, Pohl J. (1991). Child sexual abuse prevention: evaluation and one-year follow-up. Child Abuse Negl, 15:123–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berrick JD. (1988). Parental involvement in child abuse prevention training: what do they learn? Child Abuse Negl, 12:543–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hebert M, Lavoie F, Parent N. (2002). An assessment of outcomes following parents’ participation in a child abuse prevention program. Violence Vict, 17:355–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strathearn L, Giannotti M, Mills R, et al. (2020). Long-term Cognitive, Psychological, and Health Outcomes Associated With Child Abuse and Neglect. Pediatrics, 146(4):e20200438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitchell KJ, Wolak J, Finkelhor D. (2007). Trends in youth reports of sexual solicitations, harassment and unwanted exposure to pornography on the Internet. J Adolesc Health, 40:116–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]