Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to elucidate the effect of methyltransferase-like enzyme 3 (METTL3) on inflammation and the NF-κB signaling pathway in fungal keratitis (FK).

Methods

We established corneal stromal cell models and FK mouse models by incubation with Fusarium solani. The overall RNA N6-methyladenosine (m6A) level was determined using an m6A RNA methylation assay kit. The expression of METTL3 was quantified via real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR), Western blotting, and immunofluorescence. Subsequently, the level of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) was identified by Western blotting and immunofluorescence. Moreover, we assessed the effect of METTL3 by transfecting cells with siRNA (in vitro) or adeno-associated virus (in vivo). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and slit-lamp biomicroscopy were performed to evaluate corneal damage. Furthermore, the state of NF-κB signaling pathway activation was examined by Western blotting. In addition, RT–PCR and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were performed to evaluate levels of the pro-inflammatory factors interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and TNF-ɑ.

Results

Our data demonstrated that the levels of the RNA m6A methylation and METTL3 were dramatically increased and that the NF-κB signaling pathway was activated in Fusarium solani-induced keratitis. Inhibition of METTL3 decreased the level of TRAF6, downregulated the phospho-p65(p-p65)/p65 and phospho-IκB(p-IκB)/IκB protein ratios, simultaneously attenuating the inflammatory response and fungal burden in FK.

Conclusions

Our research suggests that the m6A methyltransferase METTL3 regulates the inflammatory response in FK by modulating the NF-κB signaling pathway.

Keywords: fungal keratitis (FK), Fusarium solani, METTL3, m6A, NF-κB pathway

Fungal keratitis (FK) is an infectious corneal disease that can severely undermine visual function.1 It has high morbidity in tropical agricultural countries.2 Nevertheless, its incidence has recently increased in developed countries with the widespread use of immunosuppressants and antibiotics on the ocular surface.3 Previous studies have found that Fusarium solani was the prominent etiological agent in fungal keratitis.4,5 Currently, this infectious disease has a poor prognosis, predominantly due to the limited penetration of antifungal drugs and the lack of corneal donors for keratoplasty.2,6 The exact mechanism underlying FK and innovative treatments await elucidation.

N6-methyladenine (m6A) is closely associated with the genesis and progression of infectious diseases.7,8 The m6A modification is dynamically established and maintained by methyltransferases and demethylases. As an essential m6A methylation enzyme, METTL3 regulates various cellular functions by altering the methylation level of RNAs.9 Our previous research revealed that the level of METTL3 was obviously increased in mouse corneal tissues infected with F. solani.10 Previous reports have indicated that METTL3 can cause an inflammatory response that is essential for pathogen clearance.11,12 Aberrant expression of inflammatory factors can lead to corneal ulcers, dissolution, and even perforation.13 Nevertheless, the potential mechanism and functional role of METTL3 in inflammation during FK have not been well illuminated.

The nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) signaling pathway is typically involved in inflammatory response and plays an indispensable role in the physiological and pathological mechanisms of infectious keratitis.14,15 However, the upstream regulator of the NF-κB signaling pathway in FK remains elusive. Recent research has demonstrated that METTL3 can modulate the inflammatory response in macrophages via the NF-κB signaling pathway in rheumatoid arthritis.16 Hence, we wondered whether METTL3 can also regulate the NF-κB signaling pathway in FK.

In the current study, the overall RNA m6A level and METTL3, inflammatory factors, and NF-κB signaling expression levels were evaluated in FK. Furthermore, the efficacy and mechanisms of METTL3 inhibition in FK were explored. We aimed to provide an innovative approach for treatment of FK from the perspective of epigenetic regulation.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Fungal Suspensions

The standard Fusarium solani (F. solani) strain (AS 3.1829) was obtained from the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC, Beijing, China) and inoculated on Sabouroud medium (Sigma–Aldrich, St, Louis, MO, USA) at 28°C for 5 to 7 days. The concentration of F. solani suspension was adjusted to 1 × 108 conidia/mL by the addition of distilled water for use.

Animals and Corneal Infection

Male BALB/C mice aged 6 weeks were purchased from the Laboratory Animal Center (Charles River, Beijing, China). All animals were managed based on the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) were developed and obtained from Hanbio Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Prior to infection with the fungus, the mice were randomly divided into the following 3 groups (n = 6/group): AAV-siNC group (subconjunctival injection of 2 µL HBAAV2/DJ-EGFP NC), AAV-siMETTL3 group (subconjunctival injection of 2 µL HBAAV2/DJ-m-Mettl3 shRNA1-EGFP), and F. solani group (subconjunctival injection of 2 µL sterile PBS). After 2 weeks, the FK models were established as described in our previous study.17 In brief, intraperitoneal injection with 0.6% pentobarbital sodium was applied for general anesthesia, and 0.5% proparacaine hydrochloride was used for topical anesthesia in mice. Subsequently, the corneal epithelium (2.5 mm in diameter) was removed with an electric scraper. Next, soft contact lenses (approximately 5 mm in diameter) prepared from the rat cornea were applied to cover the mouse corneas. Afterward, 5 µL of fungal suspension was injected between the corneal wound and the rat corneal button. Next, 5-0 silk sutures were used for temporary eyelid closure. Finally, the sutures were removed after infection for 24 hours. Corneas were harvested at the appropriate time for subsequent experiments.

Clinical Scoring

The phenotype of mouse corneas was assessed daily via photographs obtained using slit-lamp biomicroscopy. According to a previously published scoring system,18 the severity of FK was assessed using a clinical score from 0 to 12. The 3 criteria, opacity area, opacity density, and surface regularity, were assigned a score of 0 to 4 depending on the severity. A clinical score of 0 to 5 was assessed as mild, 6 to 9 as moderate, and more than 9 as severe.

Primary Cell Culture

Mouse eyeballs were extracted and digested with 0.2 mL dispase II enzyme (Sigma–Aldrich) at 4°C overnight. After the loose corneal epithelium and endothelium were removed, the tissues were gently minced and homogenized with 0.5 mL collagenase A (Sigma–Aldrich) at 37°C for 1 hour. The digestion was terminated with DMEM F-12 medium (Sigma–Aldrich) containing 10% fetal bovine serum. The cell suspension was inoculated in a cell culture flask. Eventually, the corneal stromal cells were adhered to the culture flask wall and passaged every 3 to 5 days.

Cell Transfection

Corneal stromal cells (2 × 105 cells/well) in 6-well plates were cultured with 1 mL of serum-free DMEM overnight before transfection. The cells were divided randomly into three groups: the siCTRL (siR NC, lot: siN000000 1-1-5; RiboBio Co., Guangzhou, China) group, the siMETTL3 (si-m-METTL3, lot: siB170206094444) group, and the F. solani group (non-transfected). According to the manufacturer's protocol, we transfected corneal stromal cells with the corresponding siRNA at 100 nM mixed with Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). After 48 hours of transfection with siRNA, the cells were infected with or without F. solani (multiplicity of infection = 3) for 6 hours.

Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was extracted from corneal stromal cells or mouse corneas using an isolation kit (Trans Biotech, Beijing, China). Complementary deoxyribonucleic acids (cDNAs) were generated using a cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) was performed by ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Mix (Vazyme), with GAPDH as an internal reference. The primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Finally, the relative mRNA expression levels were determined using the 2−∆∆CT method.

Western Blotting

Sample proteins (30 µg) extracted from mouse corneal tissues or corneal stromal cells were separated on 12.5% SDS–PAGE gels and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Boston, MA, USA). Afterward, the protein was blocked with 5% BSA (Solarbio, Beijing, China) for 2 hours. Next, the samples were incubated with the corresponding primary antibodies on a shaker platform at 4°C overnight. The antibodies used are detailed in Supplementary Table S2. After three rinses, the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibodies (Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA). Eventually, the membranes were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (Millipore).

Immunofluorescence

Mouse eyeballs were harvested and embedded in O.C.T. gel (Sakura Finetek, Tokyo, Japan). For use, corneas were sectioned into 7 µm slices and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma–Aldrich). Then, the sections were incubated with the corresponding antibody at 4°C on a shaker overnight. All antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Table S2. Tissue slides were visualized using secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 (Abcam) for 1 hour. Finally, all images were analyzed using a TE2000-U microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Hematoxylin and Eosin Staining

Mouse eyeballs were harvested and fixed in 4% formalin overnight. Samples were embedded with paraffin and sectioned (5 µm thickness) using an ultramicrotome. Corneal slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin reagents. Afterward, the samples were fixed with neutral resin and then subjected to examination under a microscope.

Quantification of Overall m6A Levels

The overall m6A content in RNA was examined using an m6A RNA Methylation Assay kit (ab185912; Abcam). Following the manufacturer's instructions, 200 ng of RNA sample was added to the assay plate. Then, the capture antibody (1:1000), detection antibody (1:2000) and enhancer solution (1:5000) were diluted into each well. The reaction was terminated by adding 100 µL of stop solution. At last, the absorbance was tested at 450 nm using a SpectraMax M2 multimode reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

The IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α protein levels in mouse corneas or corneal stromal cells were detected using commercially available ELISA kits (Proteintech, Wuhan, China) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Then, the absorbance was detected at 450 nm using a SpectraMax M2 multimode reader (Molecular Devices).

Colony Counts

Fungal burden was assessed by counting colony forming units (CFUs). Corneas were collected on day 5 postinfection and homogenized in 1 mL PBS. Then, 25 µL of homogenate was inoculated uniformly onto Sabouroud medium plates after a 1:10 dilution. After 3 days of culture, the fungal colonies were counted manually, and the count was adjusted by the dilution factor.

We used a procedure similar to the CFU tests above to investigate the effect of macrophage-phagocytosis. After 48 hours of transfection with the corresponding siRNA, the primary macrophages were infected with F. solani for 2 hours. Then, 10 µL of supernatant containing spore suspensions was inoculated uniformly onto Sabouroud medium plates after a 1:100 dilution. After 2 days of culture, the fungal colonies were counted manually, and the count was adjusted by the dilution factor.

Cell Counting Kit-8 Assay

Cell viability was tested via cell counting kit-8 (CCK8). After 48 hours of transfection with the corresponding siRNA, corneal stromal cells (2 × 103 cells/well) were added into 96-well plates overnight, and then infected with F. solani for 4 hours, followed by incubating with 10 µL of CCK8 reagents (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) for 2 hours. Subsequently, the absorbance at 450 nm was detected through a microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

Primary Macrophage Culture

Briefly, BALB/C mice were euthanized at the suitable time. After stripping the skeletal muscle with forceps, the femur and tibia were surgically removed. The bone marrow cavity was rinsed three times with sterile PBS until it turned white. The suspension was carefully collected in a 15 mL centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 minutes, discarding the supernatant at the end. Then, 1.5 mL of erythrocyte lysis solution (Solaibao, Beijing, China) was added to the precipitate. Then, an equal volume of PBS was added to terminate the reaction. After centrifugation for 5 minutes, the supernatant was discarded and macrophages were added to RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS, recombinant mouse MCSF (10 ng/mL, 315-02-10, PeproTech, Eching, Germany) for culture.

Periodic Acid-Schiff Staining

After 48 hours of transfection with the corresponding siRNA, the primary macrophages were infected with F. solani for 2 hours. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining was done according to the PAS staining kit protocol (Cat. G1360, Solaibao). Stained slides were mounted using a TE2000-U microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and imaged at 1000 times magnification.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical data are expressed as the mean ± SD (standard deviation) and were analyzed using GraphPad software (GraphPad Prism version 8.0; GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). Each experiment described above was performed at least three times. Significant differences were confirmed using an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test for two groups and 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc correction for multiple groups. P < 0.05 was declared statistically significant.

Results

Models Were Successfully Established, and the m6A Methyltransferase METTL3 Was Identified in Murine Fungal Keratitis

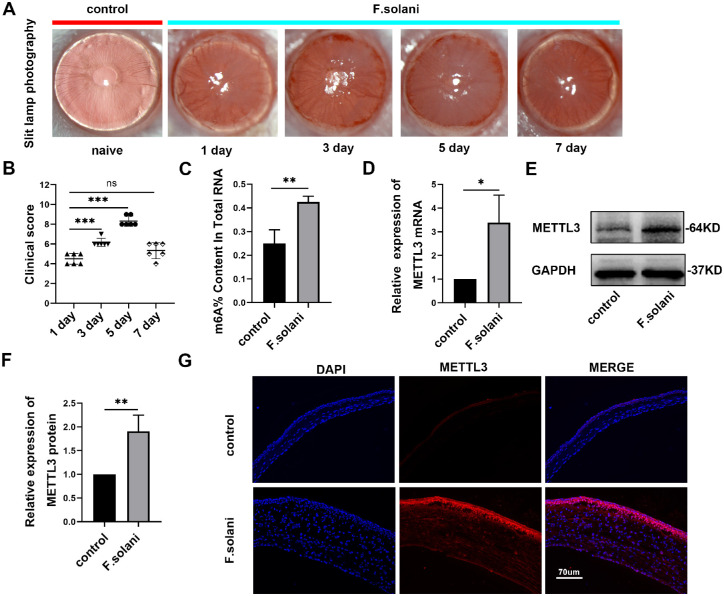

To observe the typical phenotype and pathological process of FK in mice, we successfully established a murine FK model by infecting mice with Fusarium solani. Through slit lamp photography, we found that the cornea became infected on the first day after model establishment, manifesting as corneal opacity and edema. On day 3, numerous neovascularizations appeared at the edge of the cornea. Following that, the ocular structure was severely injured, with cloudy corneas, localized ulcerations, or even perforations on day 5. On day 7, the condition was improved, with reduced corneal congestion and healing ulcers (Fig. 1A). Consistent with the above results, clinical scores increased gradually as the disease progressed, peaked on day 5, and then decreased on day 7. Therefore, we chose the fifth day post-infection as the time point for the following tests (Fig. 1B). Using an m6A RNA methylation quantification kit, we found that the m6A methylation level of RNAs extracted from corneal tissues was markedly increased after fungal infection (P < 0.01; Fig. 1C). Moreover, we used RT–PCR to evaluate METTL3, an essential m6A methyltransferase,19–21 and found that METTL3 expression was significantly upregulated in the fungal infection group (Fig. 1D). This finding was further supported by Western blotting (Figs. 1E, 1F) and immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 1G) results.

Figure 1.

The models were successfully established, and the m6A methyltransferase METTL3 was identified in murine fungal keratitis. (A) Slit-lamp observation of the corneas at 1, 3, 5, and 7 days post-infection. (B) Clinical scores showing that inflammation peaked on day 5. (C) The m6A content in total RNAs in both groups. (D) METTL3 expression was noticeably increased in mouse fungal keratitis, as shown by RT–PCR analysis. (E, F) METTL3 protein levels were assessed via Western blotting. (G) Immunofluorescence was performed to determine METTL3 levels; n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. The scale bar indicates 70 µm.

Inflammatory Cell Infiltration Was Elevated and Inflammatory Factor Levels Were Increased in the Fungal Keratitis Model

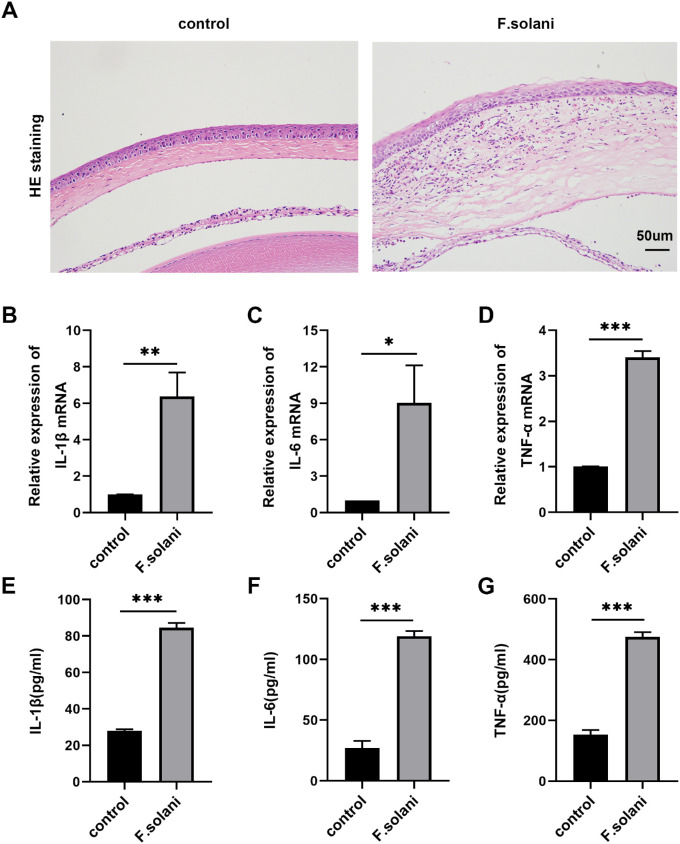

The m6A methylation is closely related to the inflammatory response in infectious diseases.8,22 We further examined the infiltration of inflammatory cells into the cornea via H&E staining and changes in the inflammatory signaling pathway via RT–PCR and ELISAs. The entire cornea became edematous and thickened after fungal infection, with epithelial defects and irregularity. Many inflammatory cells, accompanied by neovascularization, infiltrated the corneal stroma, with some cells entering the anterior chamber (Fig. 2A). Moreover, through RT–PCR (Figs. 2B–D) and ELISA (Figs. 2E–G) analyses, the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were found to be elevated in the fungal infection group compared with the control group.

Figure 2.

Inflammatory cell infiltration was elevated and inflammatory factor levels were increased in the fungal keratitis model. (A) Histopathological analysis after HE staining of mouse corneas from the F. solani and control groups. Scale bar = 50 µm. (B-D) The levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α mRNA were analyzed by RT–PCR. (E-G) ELISA results showing IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α protein levels in mouse fungal corneas in each group; n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

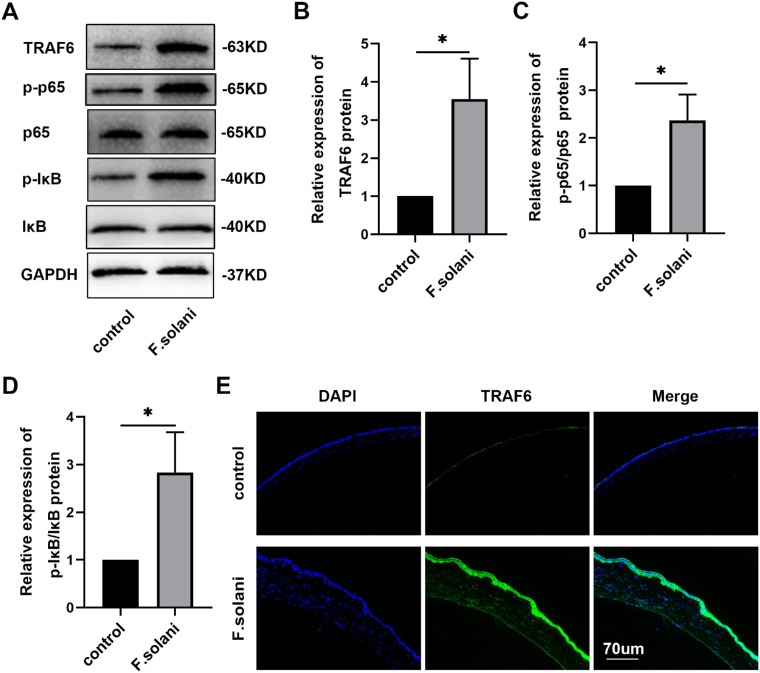

The NF-κB Signaling Pathway Was Activated in the Cornea of the Murine Fungal Keratitis Model

To explore the underlying mechanisms of the METTL3 effect in FK, we investigated the activation of the classic NF-κB inflammatory pathway. Using Western blotting, we found that the expression levels of TRAF6, p-IκB/IκB and p-p65/p65 were notably increased in the F. solani group in comparison with the control group (Figs. 3A–D). Furthermore, immunofluorescence staining demonstrated that TRAF6 protein levels were obviously elevated post-infection (Fig. 3E). These results demonstrate that m6A modification may function in FK by activating the NF-κB signaling pathway.

Figure 3.

The NF-κB signaling pathway was activated in corneas from the murine fungal keratitis model. (A–D) Western blotting results revealed the levels of TRAF6, p-IκB/IκB, and p-p65/p65 protein in the mouse corneas 5 days after infection. (E) Immunofluorescence was performed to detect the TRAF6 protein expression level in the FK group and the control group. The scale bar indicates 70 µm; n = 6; *P < 0.05.

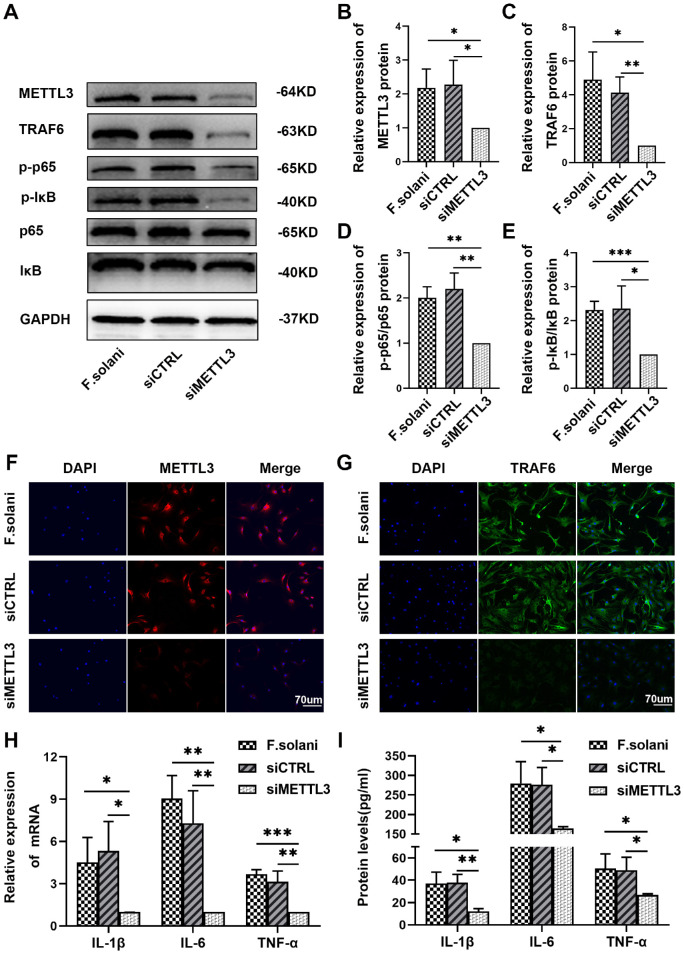

Suppression of METTL3 Attenuated Inflammation Through the NF-κB Signaling Pathway in Mouse Corneal Stromal Cells Incubated With Fungi

To investigate the role of METTL3 in the regulation of inflammation in vitro, we transfected mouse corneal stromal cells incubated with fungi with the corresponding siCTRL (siR NC) or siMETTL3 (si-m-METTL3) constructs. Through Western blotting, we found a significant decrease in the levels of METTL3, TRAF6, p-IκB/IκB, and p-p65/p65 in the siMETTL3 group compared to the F. solani and siCTRL groups (Figs. 4A–E). Further immunofluorescence staining revealed that METTL3 and TRAF6 protein expression was remarkably reduced following METTL3 silencing (Figs. 4F, 4G). Then, the expression levels of inflammatory cytokines were determined by RT-PCR and ELISAs. The PCR experiments indicated that the levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α mRNA in the siMETTL3 group were clearly reduced compared to levels in the F. solani and the siCTRL groups after exogenous downregulation of METTL3 (Fig. 4H). In addition, the ELISA results showed a corresponding trend with the PCR outcomes in mouse corneal stromal cells (Fig. 4I). These findings indicate that inhibition of METTL3 in fungus-infected cells in vitro can attenuate the inflammatory response via the NF-κB signaling pathway.

Figure 4.

Suppression of METTL3 attenuated inflammation through the NF-κB signaling pathway in mouse corneal stromal cells incubated with fungi. (A-E) The protein expression levels of METTL3, TRAF6, p-IκB/IκB and p-p65/p65 in corneal stromal cells infected with fungi were measured via western blotting. (F, G) Immunofluorescence staining was used to evaluate METTL3 and TRAF6 protein expression in corneal stromal cells treated with F. solani. The scale bar indicates 70 µm. (H) Quantification of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α by RT–PCR. (I) The protein levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were determined by ELISAs; n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

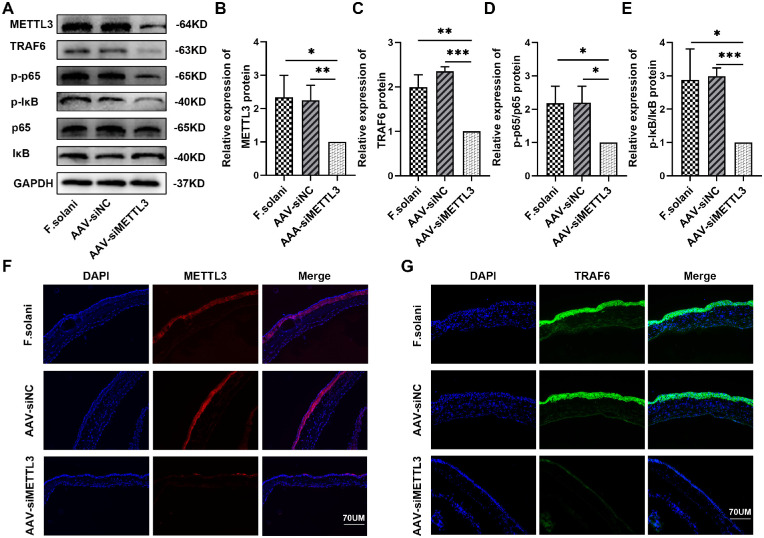

Inhibition of METTL3 Alleviated Inflammation via the NF-κB Signaling Pathway in the Mouse Fungal Keratitis Model

To evaluate the effect of METTL3 knockdown on the modulation of inflammatory responses in vivo, we subconjunctivally injected mice with an AAV vector expressing a short hairpin RNA against METTL3 mRNA 2 weeks before fungal infection (AAV-siNC refers to AAV2/DJ-EGFP NC; AAV-siMETTL3 refers to AAV2/DJ-m-Mettl3 shRNA1-EGFP; and F. solani refers to the negative control). Western blotting results demonstrated that, in contrast with the F. solani and AAV-siNC groups, the levels of METTL3, TRAF6, p-IκB/IκB, and p-p65/p65 were dramatically decreased in the AAV-siMETTL3 group (Figs. 5A–E). The trend in METTL3 and TRAF6 expression was further verified by immunofluorescence staining (Figs. 5F, 5G).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of METTL3 suppressed the state of the NF-κB signaling pathway in the mouse model of fungal keratitis. (A–E) The METTL3, TRAF6, p-IκB/IκB, and p-p65/p65 protein expression levels in corneal tissues from FK models were analyzed via western blotting. (F) Immunofluorescence staining of METTL3 protein in the murine FK model. (G) Immunofluorescence images of TRAF6 protein in corneal tissues; n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. The scale bar indicates 70 µm.

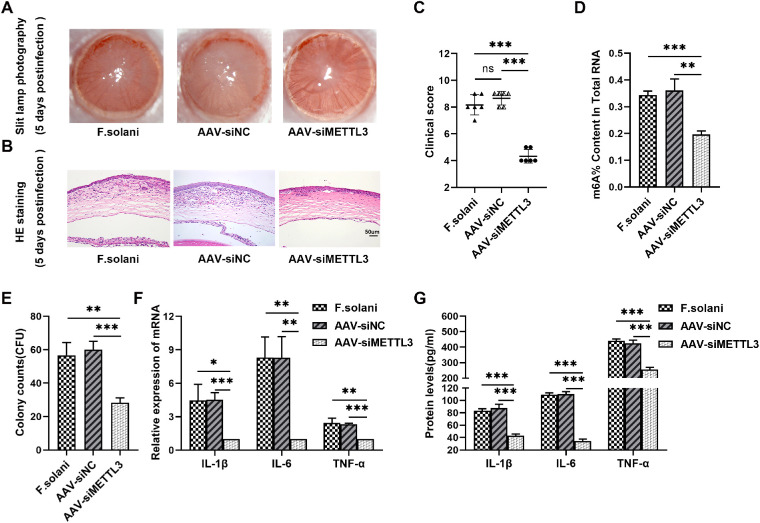

Through slit lamp photographic observation, we found that edema and opacity in mouse corneas were alleviated after exogenous downregulation of METTL3. In addition, H&E staining identified less inflammatory cell infiltration and milder corneal edema in the AAV-siMETTL3-treated group (Figs. 6A, 6B). Correspondingly, compared to the F. solani and the AAV-siNC groups, the clinical scores were markedly decreased in the AAV-siMETTL3 group (Fig. 6C). Meanwhile, we found that the level of total RNA m6A modification in mouse corneas was downregulated after transfection with AAV encoding siMETTL3 (Fig. 6D). Next, CFU counts indicated that treatment with AAV-siMETTL3 apparently reduced the fungal burden in keratitis (Fig. 6E). CCK8 assay showed that the viability of corneal stromal cells treated with AAV-siMETTL3 was significantly enhanced (Supplementary Fig. S1D). PAS staining displayed that phagocytosis of spores by macrophages was considerably enhanced in the siMETTL3 group compared to the F. solani and the siCTRL groups (Supplementary Figs. S1A, S1B). Then, the ability of macrophages to clear fungal spores in vitro was quantified by CFU counts. The CFU counts indicated that the fungal burden in the siMETTL3 group was clearly reduced compared to the F. solani and siCTRL groups (see Supplementary Fig. S1C). Finally, using RT–PCR, we found that the levels of the IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α genes were obviously reduced in the AAV-siMETTL3 group compared with the F. solani and the AAV-siNC groups (Fig. 6F), with corresponding results showing a declining trend detected in ELISAs (Fig. 6G). These results suggest that exogenous knockdown of METTL3 can attenuate the corneal inflammatory response and promote fungal clearance by modulating the NF-κB signaling pathway in murine FK.

Figure 6.

METTL3 silencing reduced inflammation and fungal burden in fungal keratitis. (A) Representative photographs of mouse corneas at 5 days after fungal infection. (B) Pathological alterations in the corneas of mice observed via H&E staining. The scale bar indicates 50 µm. (C) Clinical scores showing the inflammation in corneas among the F. solani, the AAV-siNC, and the AAV-siMETTL3 groups. (D) Comparison of the m6A content in total RNAs among the F. solani, the AAV-siNC, and the AAV-siMETTL3 groups. (E) Fungal burden was quantified by counting the colony forming units. (F, G) The levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α were evaluated via RT–PCR and ELISAs; n = 6; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

FK is a severe corneal disease that can cause visual impairment, blindness, and irritation or pain in the eyes,23 with a high morbidity of more than 1 million cases each year worldwide.6 Studies have shown that a vigorous and rapid inflammatory response to microbial infection is triggered for pathogen clearance, whereas an excessive response can cause corneal damage.13,24 In particular, m6A RNA methylation may play an indispensable role during the inflammatory response to infectious diseases.25 The detailed mechanism of FK and potential targets for treatment strategies await elucidation. In the current study, we identified elevated m6A levels in FK and found that METTL3 intervention could mediate FK pathogenesis and affect prognosis by regulating inflammatory pathways.

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most abundant internal epigenetic RNA modification among all posttranscriptional mRNA modifications.26 METTL3, the first essential methyltransferase identified, can catalyze m6A methylation in mammalian mRNA and affect RNA metabolism.27 Wang et al. noted that Mettl3-mediated m6A modification can promote the activation of dendritic cells and induce the immune response of T cells.28 Recent studies have revealed that METTL3-mediated m6A modifications play a critical regulatory role in infection and inflammation.8,11 The literature indicates that downregulation of METTL3 inhibits the LPS-induced inflammatory response and apoptosis in pediatric patients with pneumonia and cell models.29 In addition, Li et al. reported that the m6A modification levels of mRNA were upregulated in macrophages in an atherosclerosis model and that knockdown of METTL3 reduced m6A modification levels and attenuated the inflammatory response.30 Consistently, we found that the m6A RNA methylation level was increased, whereas the expression levels of METTL3 and inflammatory factors were elevated after fungal infection. Therefore, we hypothesized that METTL3 might play a pro-inflammatory role in FK.

The NF-κB signaling pathway is reported to be one of the classical pathways for regulating immunity and producing inflammatory cytokines in various diseases.31,32 When the NF-κB pathway is rapidly activated, inhibitor of kappa B (IκB) is phosphorylated by IκB kinase (IKK) and degraded by ubiquitination, leading to the release and nuclear translocation of NF-κB (p65), which allows inflammatory gene transcription.33 Recent evidence suggests that the NF-κB pathway is activated in murine Aspergillus fumigatus keratitis.15,34 However, the upstream regulators of the NF-κB pathway in FK remain obscure. Notably, our study found that the expression of inflammatory factors was elevated and that the NF-κB pathway was activated in FK. Previous reports have demonstrated that METTL3 is involved in regulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway.16,35 Inspired by these findings, we further investigated the regulatory effects of METTL3 inhibition on the NF-κB signaling pathway in vitro and in vivo. We found that inhibiting METTL3 in FK suppressed activation of the NF-κB pathway. This may provide innovative targets for the treatment of FK.

TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) is a critical upstream regulator of the NF-κB signaling pathway36 and plays an essential role in infectious diseases.37,38 In this study, we found elevated TRAF6 expression and NF-κB signaling pathway activation in FK and that silencing METTL3 resulted in a reduction in TRAF6 expression and inhibition of the NF-κB pathway. Consistently, a recent study demonstrated that the METTL3 and TRAF6 proteins can be combined and are positively correlated with each other.22 Mechanistic studies have shown that METTL3 can upregulate the methylation level of TRAF6 mRNA and promote nuclear export of RNA, leading to increased TRAF6 protein expression.39,40 Therefore, it is speculated that TRAF6 might be a potential target of m6A methylation in FK, affecting the NF-κB signaling pathway.

Increasing evidence suggested that METTL3 is involved in many inflammatory diseases.20,30 We further investigated whether METTL3 plays a functional role in the inflammatory response in FK. Our study revealed that METTL3 silencing attenuated inflammatory cell infiltration and reduced clinical scores in vivo. METTL3 suppression has been reported to decrease viral replication and promote pathogen clearance.41 As expected, our study demonstrated reduced fungal burden in FK after exogenous knockdown of METTL3. Previous studies have reported that corneal stromal cell, once activated, can phagocytose fungal spores.42–44 Our study revealed that downregulation of METTL3 enhanced the viability of corneal stromal cells, which may also promote fungal clearance. In addition, our previous study revealed that in murine FK, autophagic activity of keratocytes is inhibited, protective inflammatory response is diminished, and damaging inflammatory response is enhanced. After activation of autophagy, corneal stromal cells are more activated and the clearance of fungus is accelerated, which is helpful for the repair of keratitis.17,24,45 METTL3-mediated m6A methylation can negatively regulate autophagy, and downregulation of METTL3 can promote the expression of autophagy-related genes and enhance autophagy.46,47 Therefore, we speculate that downregulation of METTL3 may promote fungal clearance by increasing autophagy flux, and further experimental validation is needed. Interestingly, we found that knockdown of METTL3 improved the ability of macrophages to clear fungal spores. The exact mechanism of action needs to be further investigated. Furthermore, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, critical proinflammatory factors, are involved in the activation of immune cells and regulation of the inflammatory response.48 Accordingly, we found that the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α was reduced after METTL3 inhibition. Similarly, silencing METTL3 in dental pulp inflammation suppressed the NF-κB signaling pathway and reduced the expression of inflammatory cytokines.49 Therefore, METTL3 might function as a pro-inflammatory factor in FK. Downregulation of METTL3 can alter the inflammatory response in FK, which might provide new therapeutic insights for antimicrobial treatments.

Conclusion

In this study, we demonstrated for the first time that METTL3 was upregulated in experimental Fusarium solani keratitis, whereas reducing METTL3 expression could alleviate the inflammatory response by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway. We believe that METTL3 could be a feasible therapeutic target for FK treatment. Our research reveals innovative mechanisms that shed new light on FK occurrence and development. However, further studies are needed to determine the expression profile and mechanisms associated with METTL3 inhibition in microbial infection and other diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Beijing, China (grant 81870636). The author(s) have no proprietary or commercial interest in any materials discussed in this article.

Disclosure: H. Tang, None; L. Huang, None; J. Hu, None

References

- 1. Sharma N, Bagga B, Singhal D, et al.. Fungal keratitis: A review of clinical presentations, treatment strategies and outcomes. Ocul Surf. 2021; 24: 22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mills B, Radhakrishnan N, Karthikeyan Rajapandian SG, Rameshkumar G, Lalitha P, Prajna NV.. The role of fungi in fungal keratitis. Exp Eye Res. 2021; 202: 108372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Oliveira Dos Santos C, Kolwijck E, van Rooij J, et al.. Epidemiology and Clinical Management of Fusarium keratitis in the Netherlands, 2005-2016. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020; 10: 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Todokoro D, Suzuki T, Tamura T, et al.. Efficacy of Luliconazole Against Broad-Range Filamentous Fungi Including Fusarium solani Species Complex Causing Fungal Keratitis. Cornea. 2019; 38: 238–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lin Y, Zhang J, Han X, Hu J.. A retrospective study of the spectrum of fungal keratitis in southeastern China. Ann Palliat Med. 2021; 10: 9480–9487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown L, Leck AK, Gichangi M, Burton MJ, Denning DW.. The global incidence and diagnosis of fungal keratitis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021; 21: e49–e57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang A, Tao W, Tong J, et al.. m6A modifications regulate intestinal immunity and rotavirus infection. Elife. 2022; 11: e73628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wu C, Chen W, He J, et al.. Interplay of m6A and H3K27 trimethylation restrains inflammation during bacterial infection. Sci Adv. 2020; 6: eaba0647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chong W, Shang L, Liu J, et al.. m6A regulator-based methylation modification patterns characterized by distinct tumor microenvironment immune profiles in colon cancer. Theranostics. 2021; 11: 2201–2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hu J, Lin Y.. Fusarium infection alters the m6A-modified transcript landscape in the cornea. Exp Eye Res. 2020; 200: 108216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burgess HM, Depledge DP, Thompson L, et al.. Targeting the m6A RNA modification pathway blocks SARS-CoV-2 and HCoV-OC43 replication. Genes Dev. 2021; 35: 1005–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Price AM, Hayer KE, McIntyre ABR, et al.. Direct RNA sequencing reveals m6A modifications on adenovirus RNA are necessary for efficient splicing. Nat Commun. 2020; 11: 6016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hu J, Hu Y, Chen S, et al.. Role of activated macrophages in experimental Fusarium solani keratitis. Exp Eye Res. 2014; 129: 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Deng QC, Deng CT, Li WS, Shu SW, Zhou MR, Kuang WB.. NLRP12 promotes host resistance against Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis inflammatory responses through the negative regulation of NF-κB signaling. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018; 22: 8063–8075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Niu Y, Ren C, Peng X, et al.. IL-36α Exerts Proinflammatory Effects in Aspergillus fumigatus Keratitis of Mice Through the Pathway of IL-36α/IL-36R/NF-κB. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021; 62: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang J, Yan S, Lu H, Wang S, Xu D.. METTL3 Attenuates LPS-Induced Inflammatory Response in Macrophages via NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Mediators of Inflammation. 2019; 2019: 3120391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tang H, Lin Y, Huang L, Hu J.. MiR-223-3p Regulates Autophagy and Inflammation by Targeting ATG16L1 in Fusarium solani-Induced Keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2022; 63: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wu TG, Wilhelmus KR, Mitchell BM.. Experimental keratomycosis in a mouse model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003; 44: 210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gong R, Wang X, Li H, et al.. Loss of m6A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes heart regeneration and repair after myocardial injury. Pharmacol Res. 2021; 174: 105845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pan J, Liu F, Xiao X, et al.. METTL3 promotes colorectal carcinoma progression by regulating the m6A-CRB3-Hippo axis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022; 41: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xu Y, Lv D, Yan C, et al.. METTL3 promotes lung adenocarcinoma tumor growth and inhibits ferroptosis by stabilizing SLC7A11 m6A modification. Cancer Cell Int. 2022; 22: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wen L, Sun W, Xia D, Wang Y, Li J, Yang S.. The m6A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes LPS-induced microglia inflammation through TRAF6/NF-κB pathway. Neuroreport. 2022; 33: 243–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prajna NV, Radhakrishnan N, Lalitha P, et al.. Cross-Linking Assisted Infection Reduction: One-year Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial Evaluating Cross-Linking for Fungal Keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2021; 128: 950–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guo Q, Lin Y, Hu J.. Inhibition of miR-665-3p Enhances Autophagy and Alleviates Inflammation in Fusarium solani-Induced Keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021; 62: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Panneerdoss S, Eedunuri VK, Yadav P, et al.. Cross-talk among writers, readers, and erasers of m6A regulates cancer growth and progression. Sci Adv. 2018; 4: eaar8263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yue Y, Liu J, He C.. RNA N6-methyladenosine methylation in post-transcriptional gene expression regulation. Genes Dev. 2015; 29: 1343–1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Liu J, Yue Y, Han D, et al.. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol. 2014; 10: 93–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang H, Hu X, Huang M, et al.. Mettl3-mediated mRNA m6A methylation promotes dendritic cell activation. Nat Commun. 2019; 10: 1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang Y, Yang X, Wu Y, Fu M.. METTL3 promotes inflammation and cell apoptosis in a pediatric pneumonia model by regulating EZH2. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2021; 49: 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li Z, Xu Q, Huangfu N, Chen X, Zhu J.. Mettl3 promotes oxLDL-mediated inflammation through activating STAT1 signaling. J Clin Lab Anal. 2022; 36: e24019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Banoth B, Chatterjee B, Vijayaragavan B, Prasad MV, Roy P, Basak S.. Stimulus-selective crosstalk via the NF-κB signaling system reinforces innate immune response to alleviate gut infection. Elife. 2015; 4: e05648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cao F, Huang C, Cheng J, He Z. β-arrestin-2 alleviates rheumatoid arthritis injury by suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome activation and NF-κB pathway in macrophages. Bioengineered. 2022; 13: 38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Piao W, Xiong Y, Famulski K, et al.. Regulation of T cell afferent lymphatic migration by targeting LTβR-mediated non-classical NFκB signaling. Nat Commun. 2018; 9: 3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Qin Q, Hu K, He Z, et al.. Resolvin D1 protects against Aspergillus fumigatus keratitis in diabetes by blocking the MAPK-NF-κB pathway. Exp Eye Res. 2022; 216: 108941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu E, Lv L, Zhan Y, et al.. METTL3/N6-methyladenosine/miR-21-5p promotes obstructive renal fibrosis by regulating inflammation through SPRY1/ERK/ NF-κB pathway activation. J Cell Molec Med. 2021; 25: 7660–7674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li Y, Zhang L, Zhang P, Hao Z.. Dehydrocorydaline Protects Against Sepsis-Induced Myocardial Injury Through Modulating the TRAF6/NF-κB Pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2021; 12: 709604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fang J, Muto T, Kleppe M, et al.. TRAF6 Mediates Basal Activation of NF-κB Necessary for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2018; 22: 1250–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu E, Sun J, Yang J, et al.. ZDHHC11 Positively Regulates NF-κB Activation by Enhancing TRAF6 Oligomerization. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021; 9: 710967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li D, Cai L, Meng R, Feng Z, Xu Q.. METTL3 Modulates Osteoclast Differentiation and Function by Controlling RNA Stability and Nuclear Export. Int J Mol Sci. 2020; 21: 1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zong X, Zhao J, Wang H, et al.. Mettl3 Deficiency Sustains Long-Chain Fatty Acid Absorption through Suppressing Traf6-Dependent Inflammation Response. J Immunol. 2019; 202: 567–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hao H, Hao S, Chen H, et al.. N6-methyladenosine modification and METTL3 modulate enterovirus 71 replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47: 362–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brown ME, Montgomery ML, Kamath MM, et al.. A novel 3D culture model of fungal keratitis to explore host-pathogen interactions within the stromal environment. Exp Eye Res. 2021; 207: 108581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chakravarti S, Wu F, Vij N, Roberts L, Joyce S.. Microarray studies reveal macrophage-like function of stromal keratocytes in the cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004; 45: 3475–3484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sato T, Sugioka K, Kodama-Takahashi A, et al.. Stimulation of Phagocytic Activity in Cultured Human Corneal Fibroblasts by Plasminogen. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019; 60: 4205–4214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lin J, Lin Y, Huang Y, Hu J.. Inhibiting miR-129-5p alleviates inflammation and modulates autophagy by targeting ATG14 in fungal keratitis. Exp Eye Res. 2021; 211: 108731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cao Z, Zhang L, Hong R, et al.. METTL3-mediated m6A methylation negatively modulates autophagy to support porcine blastocyst development. Biology of Reproduction. 2021; 104: 1008–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen X, Gong W, Shao X, et al.. METTL3-mediated m6A modification of ATG7 regulates autophagy-GATA4 axis to promote cellular senescence and osteoarthritis progression. Ann Rheumatic Dis. 2022; 81: 87–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yeung K, Mraz V, Geisler C, Skov L, Bonefeld CM.. The role of interleukin-1β in the immune response to contact allergens. Contact Dermatitis. 2021; 85: 387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Feng Z, Li Q, Meng R, Yi B, Xu Q.. METTL3 regulates alternative splicing of MyD88 upon the lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response in human dental pulp cells. J Cell Molec Med. 2018; 22: 2558–2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.