Abstract

Recent advances in in vitro display screening of thioether-closed macrocyclic peptide libraries have made possible the discovery of potent peptide ligands against protein targets of interest. However, conventional libraries sometimes result in the identification of undersigned, lariat-shaped peptide ligands with a protease-accessible tail region. In the present study, we have constructed an mRNA-encoded library of macrocyclic peptides by means of a cyclopropane-containing exotic initiator. The use of the structurally constrained initiator reduced the population of lariat-shaped species in the library, and successfully led to the discovery of a cyclopropane-containing macrocyclic peptide that inhibited phosphoglycerate mutase via a different mode of action from a previously identified macrocyclic peptide.

Macrocyclic peptides are an attractive class of potential pharmaceutical agents able to interact with a variety of protein targets[1–5]. Ribosomal construction and selection-based screening of peptide libraries has proven to be a promising strategy to identify cyclic peptide ligands with high affinity to designated targets[6–20]. Although there are various methodologies reported to date, the combination of mRNA display method[21–22] with genetic code reprogramming, which we refer to as the RaPID (Random nonstandard Peptides Integrated Discovery) system, has enabled us to rapidly discover de novo macrocyclic peptide ligands from vast libraries (over 1012 molecules) against protein targets of interest[20, 23–25]. In particular, its versatility for encoding diverse exotic building blocks (e.g. D-[13], N-methylated[13], carborane-containing amino acids[26], and even non-amino acids[27]), and various macrocyclization modes (e.g., N-terminus-to-sidechain[28], sidechain-to-sidechain[29–30], and N-terminus-to-C-terminus[31–32]) is extraordinarily useful for the discovery of a wide range of macrocycles.

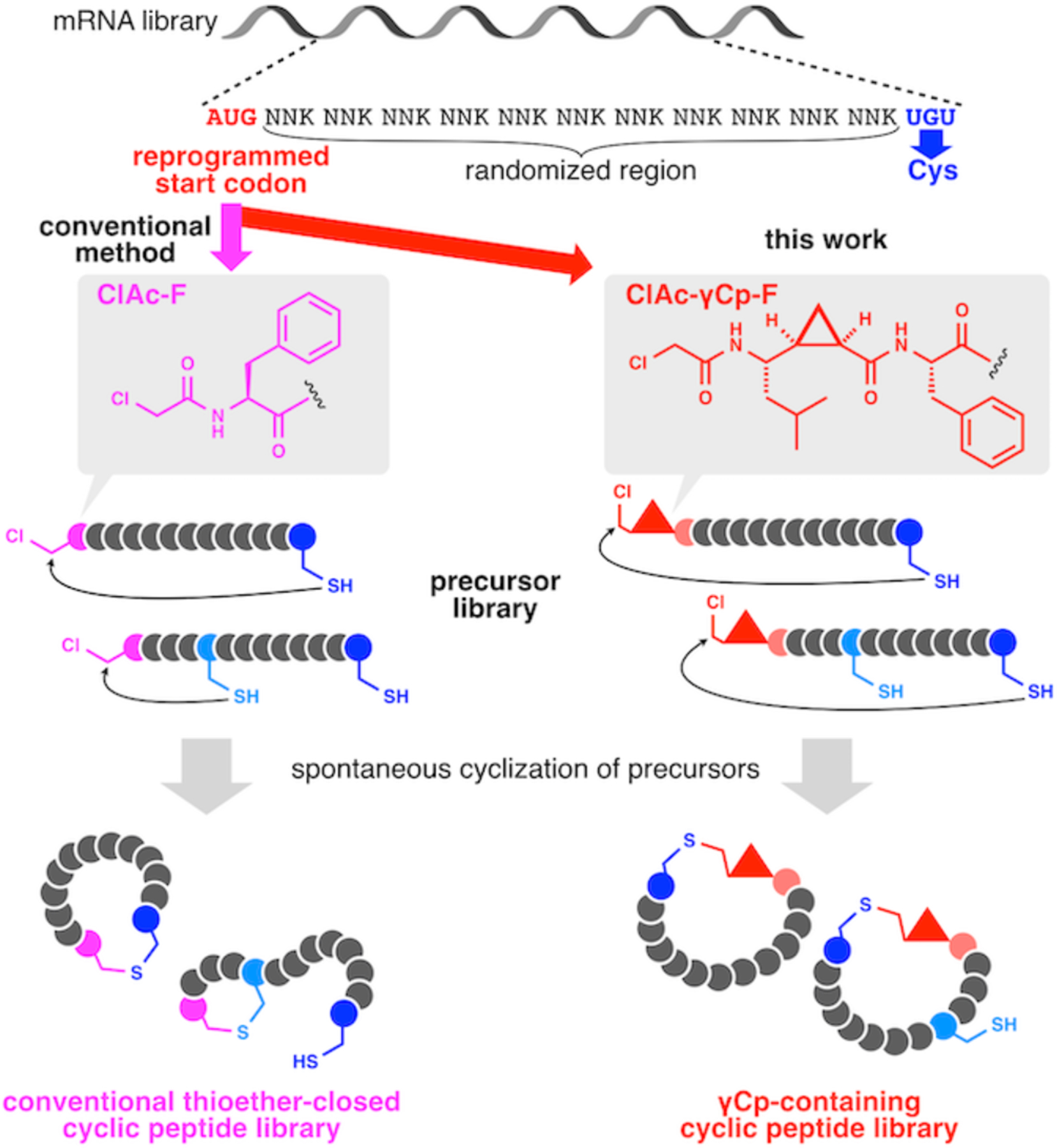

The RaPID system utilizes genetic code reprogramming powered by the flexible in vitro translation (FIT) system[33] as a synthetic method to generate macrocyclic peptide libraries. A typical design of precursor libraries includes AUG-(NNK)n-UGU sequences, in which the AUG start codon is reprogrammed with an N-chloroacetylated (ClAc) α-amino acid (Fig. 1, left) such as ClAc-phenylalanine (ClAc-F), and the repeats of NNK mixed codons and the UGU codon encode random amino acid sequences and a Cys, respectively. The N-terminal ClAc group in the expressed precursors acts as a chemical handle for spontaneous posttranslational cyclization with the thiol side chain of the designated C-terminal Cys residue to yield thioether-closed macrocyclic peptide libraries[28]. The precursor libraries potentially contain sequences with additional internal Cys residues encoded by UGU appearing in the NNK random region. We have previously verified that in such precursor peptides with two or more Cys residues, the ClAc-α-amino acid generally dictates the spontaneous cyclization with the nearest upstream Cys residue to form lariat-shaped peptides with a small N-terminal cycle and a C-terminal tail with an intact downstream Cys residue[34]. Indeed, some previous RaPID selection campaigns have yielded peptide ligands having such lariat-shaped structures[35–36].

Figure 1.

Ribosomal synthesis of cyclic peptide libraries by means of the reprogrammed FIT system using conventional ClAc-α-amino acid initiator (left) or ClAc-γCp-F demonstrated in this study (right).

We hypothesized that if a ClAc group was installed in a structurally constrained initiator, the above mode of macrocyclization might be altered to yield a different set of macrocycle libraries from the conventional macrocyclic peptide libraries. Cyclopropane-containing amino acids are structurally unique building blocks compared with ordinary α-amino acids or dipeptide units[37]. Conformation of such amino acid units is fixed by the rigid, smallest ring structure of cyclopropane. Furthermore, the side chain orientation is largely restricted depending on the stereochemistry of the asymmetric carbon adjacent to cyclopropane by the cyclopropylic strain[38–39]. Here we report construction of a cyclopropane-containing macrocyclic peptide library aiming at reducing the probability of the formation of lariat-peptide species and its application for in vitro selection against a phosphoglycerate mutase, demonstrating the development of macrocyclic peptides inhibiting the enzyme with a different mode of action from the previously reported peptide[36].

We designed a cyclopropane-containing γ-amino acid (γCp), which had a cis-configurated backbone and an anti-oriented isobutyl group[40] as a sidechain. To adapt the γCp moiety to an exotic initiator inducing posttranslational cyclization, we devised a γCp-bearing dipeptide unit (ClAc-γCp-F), in which the amino and carboxyl groups of the γCp were modified with ClAc and ligated to phenylalanine (F), respectively (Fig. 1, right). In order to make ClAc-γCp-F usable in the FIT system, the dipeptide unit was derived to cyanomethyl ester (see Scheme S1 for the synthetic scheme of a diastero-mixture of ClAc-γCp-F-CME). To verify that ClAc-γCp-F-CME can be used as an acyl-donor in the reaction using the artificial tRNA aminoacylation ribozyme, flexizyme[41], we used our conventional assay system using a tRNA analog, microhelix RNA (µhRNA). The ClAc-γCp-F-CME substrate was incubated with µhRNA in the presence of flexizyme, and the products were analyzed using acidic polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis to evaluate the aminoacylation efficiency (Fig. S1a). The gel showed a mobility-shifted band corresponding to the ClAc-γCp-F-µhRNA product. This indicated that the flexizyme system allowed the preparation of ClAc-γCp-F-tRNA under the same conditions.

To ribosomally synthesize a model peptide bearing an N-terminal ClAc-γCp-F residue (linPep1-γCp), ClAc-γCp-F-tRNAfMetCAU was prepared using flexizyme and added to a Met-depleted FIT system[33], in which the AUG start codon was reprogrammed with ClAc-γCp-F (Fig. S1b). Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) of the translation product showed a peak corresponding to the expected macrocyclic peptide closed by a thioether linking the N-terminal γCp and the downstream Cys (Fig. S1c). This result indicated that ClAc-γCp-F was successfully incorporated into the N-terminus of nascent peptide chains employing the FIT system, and subsequently underwent spontaneous cyclization to afford γCp-containing macrocyclic peptides.

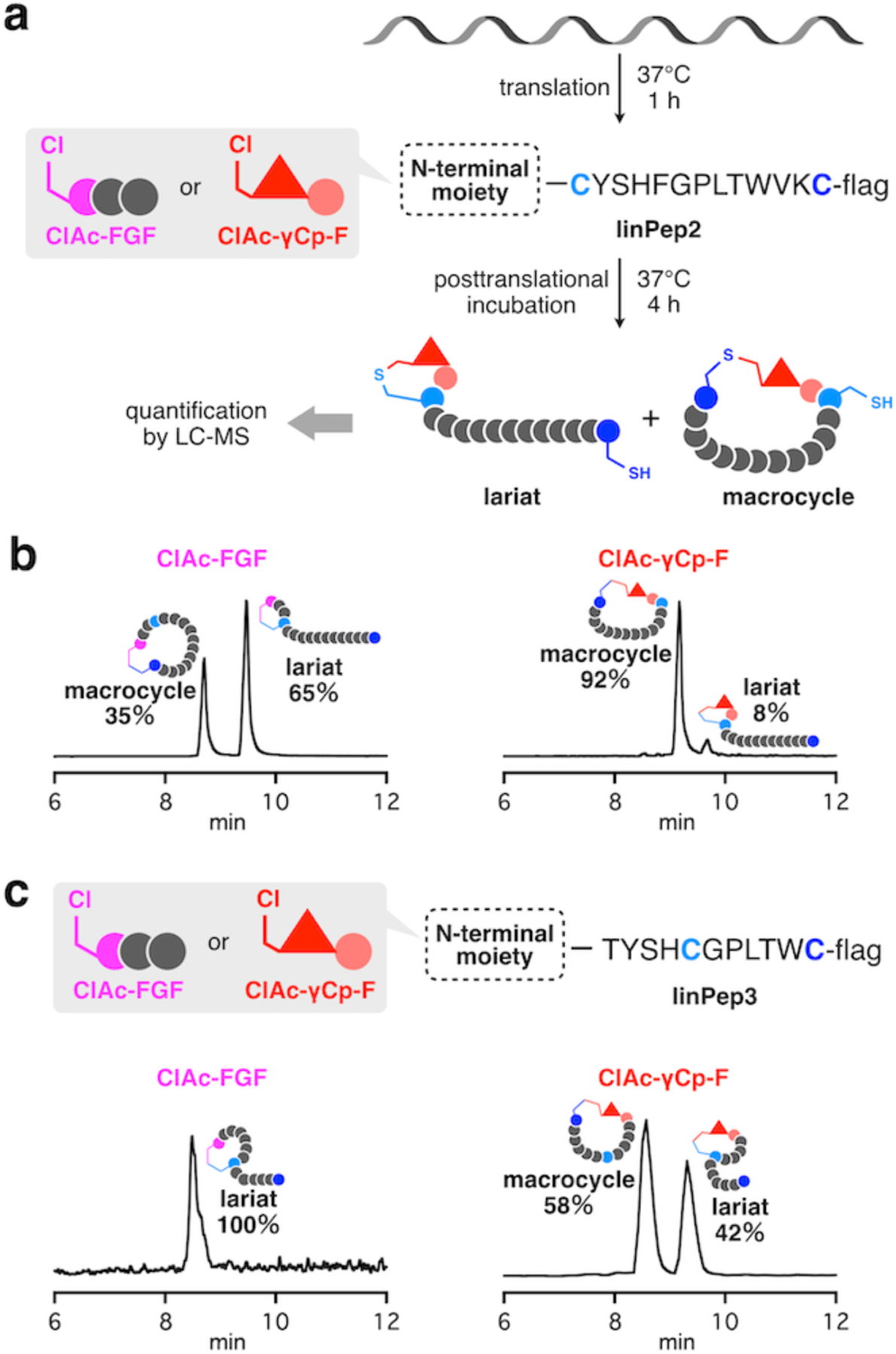

To assess the propensity of the ClAc-mediated posttranslational cyclization of precursors bearing the N-terminal γCp residue, model precursors with two Cys residues, which have ClAc-γCp-F or ClAc-FGF (an α-peptide control bearing the same atom length; G is glycine) as the N-terminal moiety, were expressed in the FIT system. The cyclization products were analyzed using liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy (LC-MS), and their cyclization modes (macrocycle or lariat) were determined using LC-MSMS (Fig. 2 and Fig. S2-5). In a representative sequence (linPep2), the ClAc-FGF-precursor gave a 35:65 mixture of macrocycle and lariat products, which was consistent with the previously described preference in ClAc-α-amino acids. In contrast, in the ClAc-γCp-precursor, the N-terminal ClAc mostly reacted with the downstream Cys to predominantly (92%) give the macrocycle product (Fig. 2b). Even in another sequence (linPep3), which quantitatively gave the lariat product in the ClAc-FGF-precursor, the ClAc-γCp-precursor could preferentially yield the macrocyclic product (Fig. 2c). In all other tested sequences (Table S1), precursors initiated with ClAc-γCp-F favorably underwent cyclization with the downstream Cys, compared with the ClAc-α-amino acid counterparts. These results indicated that the use of the ClAc-γCp initiator could reduce the frequencies of formation of the lariat-shaped peptides in sequences containing multiple Cys residues and advantageously produce peptides with large macrocycles designated by the mRNA library design.

Figure 2.

Posttranslational cyclization of model peptides bearing two Cys residues. (a) Schematic illustration of the cyclization of linPep2 derivatives containing ClAc-FGF and ClAc-γCp-F. The linPep2 derivatives, bearing ClAc-FGF or ClAc-γCp-F as the N-terminal moiety, were expressed in the FIT system and subjected to posttranslational cyclization. The resulting cyclized products were analyzed using LC-MS. (b) LC-ESI-MS analysis to monitor the posttranslational cyclization of linPep2 derivatives. Extracted-ion chromatograms (EICs) of m/z values corresponding to the cyclized peptides are shown. (c) LC-ESI-MS analysis to monitor the posttranslational cyclization of linPep3 derivatives. EICs of m/z values corresponding to the cyclized peptides are shown.

We previously carried out a conventional RaPID selection against a species-selective potential drug target in filarial parasites, cofactor-independent phosphoglycerate mutase from Caenorhabditis elegans (CeiPGM)[42–43], and successfully discover a lariat-shaped peptidic inhibitor of CeiPGM, ipglycermide B[36]. Ipglycermide B has an N-terminal macrocycle ‘head’ consisting of eight residues and a ‘tail’ peptide consisting of seven residues (Fig. S7a). The Cys residue at the C-terminus (a part of the tail peptide) was originally allocated to react with the N-terminal ClAc group in the library design, but instead an internal Cys residue appeared in the random region and macrocyclized with the ClAc group; therefore, the designated C-terminal Cys was left intact with a free thiol. Interestingly, this Cys residue was essential for the sub-nanomolar inhibitory activity. Although the crystal structure of a complex of iPGM and the ipglycermide itself is currently being elucidated, the co-crystal structure of CeiPGM and the small macrocycle head has allowed us to speculate that the tail’s Cys thiol (likely thiolate) is able to coordinate with the transition metal ion cluster in the catalytic center. However, the linear tail peptide region bearing the Cys essential for high affinity was proteolytically labile (Fig. S7b) and the free thiol might be susceptible to oxidation. This motivated us to investigate whether a ClAc-γCp-initiated macrocycle library could yield different families of macrocyclic peptide inhibitors against CeiPGM owing to less probability of the formation of lariat-shaped peptides and possibly lead to those with a different mode of inhibitory action. We thus conceived the display of the macrocycle library using the ClAc-γCp initiator in the RaPID system and performed the selection campaign against CeiPGM.

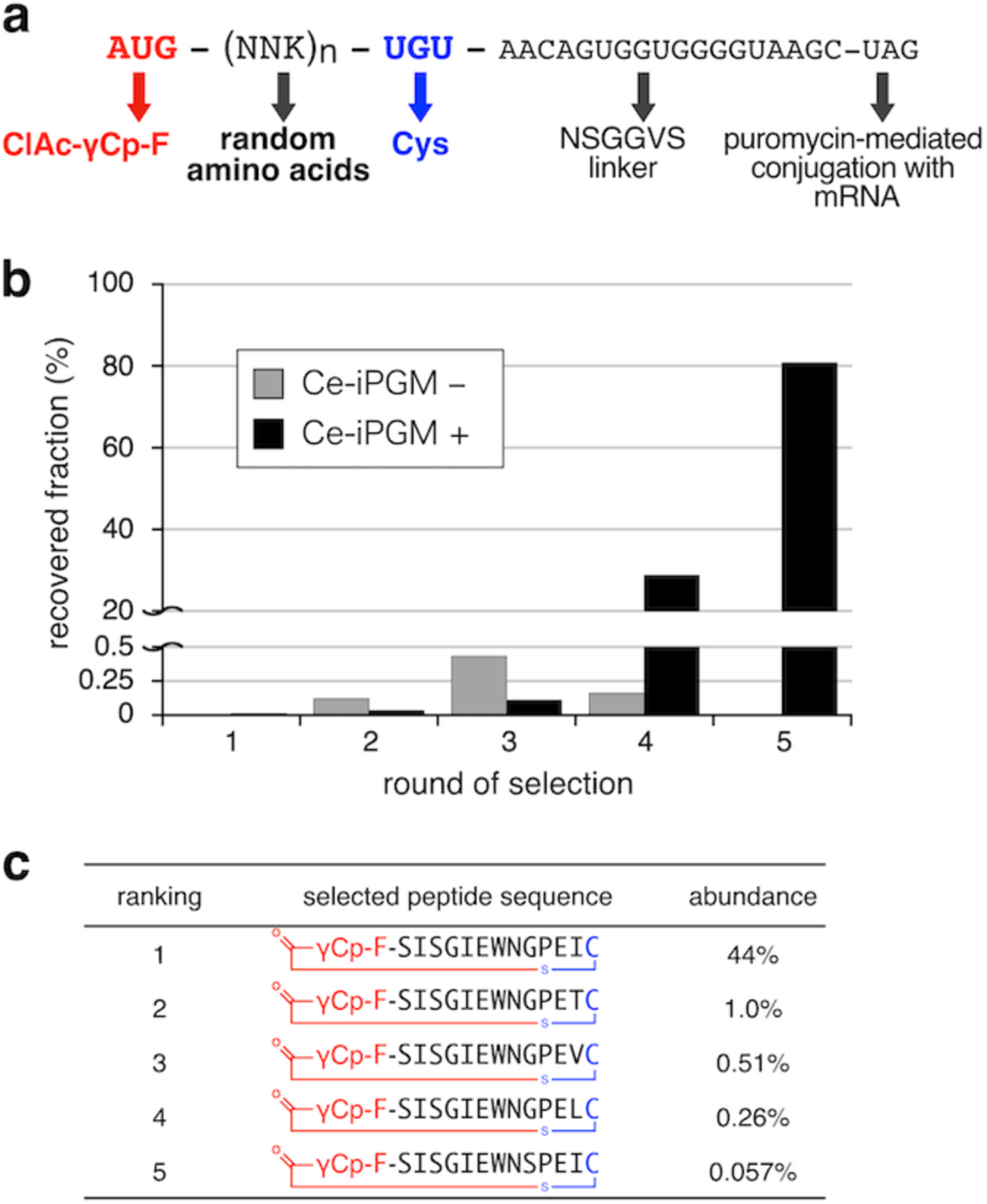

An mRNA library consisting of AUG-(NNK)n-UGU, where n is the number of repeats between 6 and 12, followed by a linker sequence and a UAG codon (Fig. 3a), were ligated to a puromycin-containing DNA oligomer, enabling the specific fusion of the peptides with their cognate mRNA templates. The linker region encodes an “NSGGVS” spacer sequence in the designated reading frame, while it includes a UAA stop codon in the undesignated reading frames, i.e. the frame-shifted peptides without the designated C-terminal Cys would not be displayed on mRNA templates (see Fig. S8 for more details). The mRNA library was expressed in the presence of ClAc-γCp-F-tRNAfMetCAU in an RF1/Met-depleted FIT system, so that the AUG was reprogrammed with ClAc-γCp-F and the UAG induced ribosome stalling that promoted efficient puromycin fusion. Subsequently, the displayed γCp-macrocycle library with over 1012 unique sequences was subjected to five rounds of affinity selection against CeiPGM, and the cDNA library after the 5th round was analyzed using deep sequencing (Fig. 3b and S9). The library was highly enriched with a family of peptides bearing a conserved “SISGIEWNGPEI” motif (Fig. 3c and S10). The RaPID selection using the γCp-containing initiator successfully led to the discovery of macrocyclic peptide sequences without a Cys-containing tail region.

Figure 3.

In vitro selection of γCp-containing macrocyclic peptides against CeiPGM. (a) mRNA sequence encoding the ClAc-γCp-F-initiated peptide library. (b) Progress of the selection. Recovery rates of cDNA at each round were calculated from the initial and recovered amounts of cDNAs determined using quantitative real time PCR. The recovery rates in the positive selection against CeiPGM-immobilized beads are shown in black while those in the negative selection against free beads are shown in gray. (c) Top 5 peptide sequences identified using deep sequencing of the cDNA library after 5 rounds of the selection.

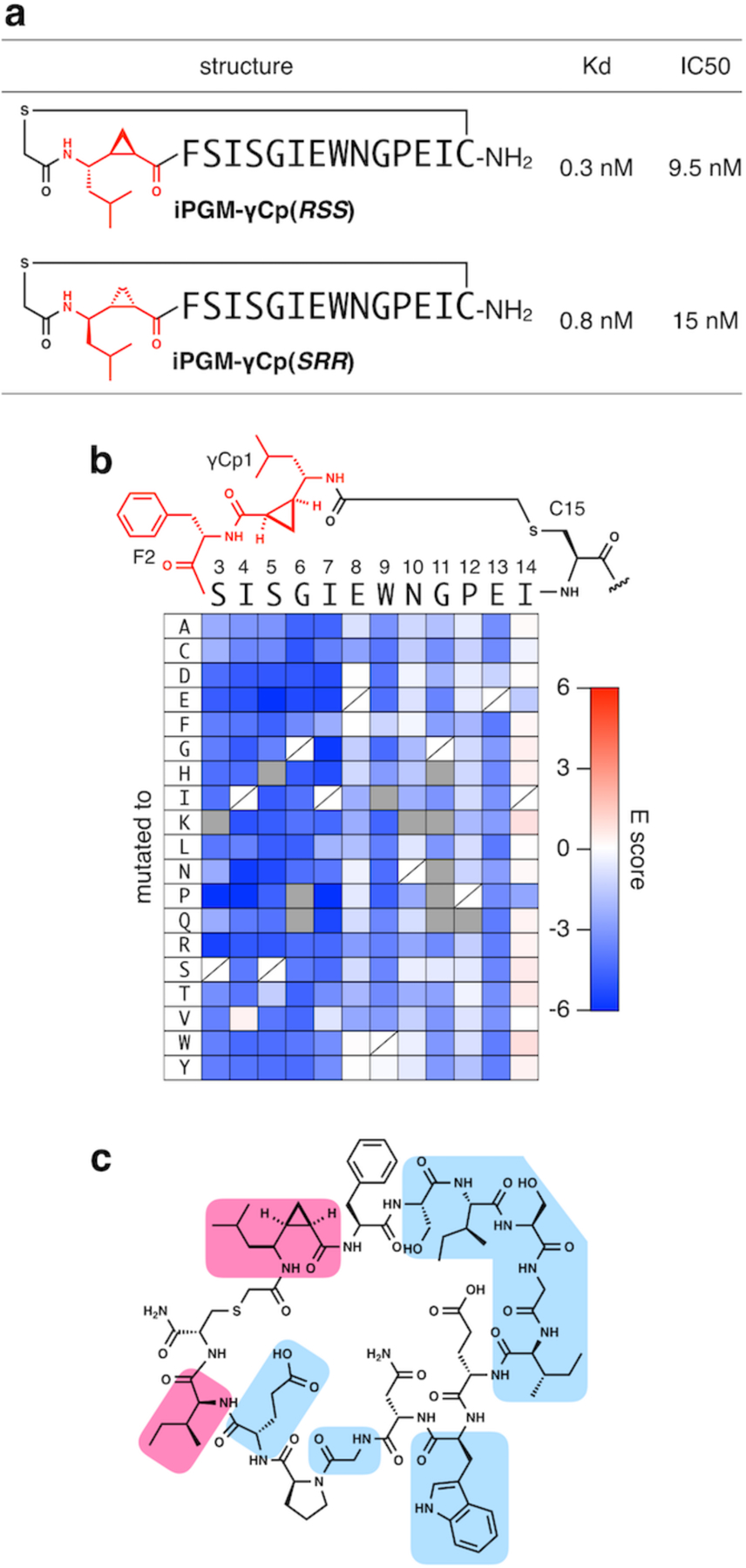

We then chemically synthesized a representative sequence in the conserved family and evaluated its binding and inhibitory activity for CeiPGM. In order to assess the importance of the configuration of the γCp group, we used the specific enantiomers (Fmoc-(R,S,S)-γCp-OH and Fmoc-(S,R,R)-γCp-OH; see Scheme S2) in the solid-phase chemical synthesis, yielding CeiPGM-γCp(RSS) and CeiPGM-γCp(SRR), respectively. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis has revealed that both enantiomerically pure peptides exhibit the dissociation constants (Kd) of 0.3 nM and 0.8 nM, respectively, where the difference was very subtle (Fig. 4a and S11a). Although the peptide with each stereoisomer of γCp could have distinct local spatial arrangement at the ring-fused region, both isomer-peptides showed similar binding ability, implying that the γCp moiety unlikely forms direct contacts with CeiPGM. As a reflection of their binding ability, they also showed potent inhibitory activity for the CeiPGM-catalyzed isomerization of 3-phosphoglycerate to 2-phosphoglycerate with IC50 values of 9.5 nM and 15 nM, respectively, which are consistent with the observation that CeiPGM-γCp(RSS) exhibits slightly higher affinity than the sister peptide (Fig. 4a and S11b). Most importantly, the γCp-macrocycles likely inhibit CeiPGM via a thiol-independent mode of action, though the exact mechanism must be defined by further investigation. Moreover, the γCp-macrocycle exhibited remarkable proteolytic stability. Upon treatment with proteinase K, ipglycermide B underwent complete decomposition in 0.5 h. In contrast, the γCp-macrocycle did not show any significant degradation after 5 h; following 96 h incubation approximately 20% of the peptide remained intact (Fig. S7b). This illuminates the advantage of the macrocyclic scaffold without a protease-accessible tail region.

Figure 4.

γCp-containing macrocyclic peptides that bind and inhibit CeiPGM. (a) Dissociation constants and half-maximal inhibitory concentrations of CeiPGM-γCp(RSS) and CeiPGM-γCp(SRR). (b) Saturation mutagenesis of CeiPGM-γCp through mRNA display. E scores for single mutants of CeiPGM-γCp are shown according to the color code. Blue and red matrices indicate that the corresponding mutants demonstrated a worse (negative E score) and better (positive E score) pull-down by CeiPGM-immobilized beads compared with the original CeiPGM-γCp. Mutants whose standard deviation of E value were over 0.5 were shown in gray. (c) Indispensable (blue) and dispensable (red) residues mapping in CeiPGM-γCp for CeiPGM binding.

To obtain insights into essential residues for CeiPGM binding, we carried out mRNA display-mediated saturation mutagenesis[44–45] of the original CeiPGM-γCp. An mRNA-displayed library of single mutants of CeiPGM-γCp, in which every position was replaced with all proteinogenic amino acids except for Met, was expressed in the FIT system. While mRNA molecules included in the expressed library were analyzed using deep sequencing, the CeiPGM-binding fraction of the library was pulled down by CeiPGM-immobilized beads, and the mRNAs tagged to the bound peptides were also quantified using deep sequencing. For each mutant, an “E score” was calculated by comparing the sequence population in the initial library and the bound fraction (see Methods section for more details), where negative and positive E scores indicated that the mutants showed worse and better binding abilities than the original sequence, respectively (Fig. 4b). This mutagenesis study revealed that the residues in S3–I7 were critical, as substitutions at these positions generally resulted in loss of binding except for I-to-V substitutions. Moreover, it appeared that aromatic residues (W, Y, or F), small residues (G or S), and acidic residues (E or D) at 9th, 11th, and 13th positions, respectively, were also required for efficient CeiPGM binding. On the other hand, Ile14, adjacent to the γCp-Cys thioether linkage, turned out to be highly variable, which was consistent with the observation that the γCp moiety was not involved in direct contact with CeiPGM. These results successfully determined indispensable/dispensable residues in CeiPGM-γCp (Fig. 4c).

In summary, we have demonstrated that a unique cyclopropane-containing building block can be incorporated into the N-terminal position of ribosomally synthesized peptides via initiation reprogramming. This has led to the construction of macrocyclic peptide libraries depleted of lariat-shaped peptides. The use of the ClAc-γCp-F-initiated macrocyclic peptide library allowed us to survey chemical spaces that were hardly accessed via conventional RaPID libraries, making it possible to identify γCp-containing macrocycles that inhibits CeiPGM with a different mode of action from a macrocycle bearing a tail peptide with a free Cys residue reported previously[36]. It has been demonstrated that the initiation of translation exhibits remarkable substrate tolerance and a wide variety of non-peptidic building blocks, such as artificial foldamer units, can be incorporated via initiation reprogramming[26–27, 46–53]. Utilization of such anthropogenic initiators, including cyclopropane-containing amino acids demonstrated in this study, will further expand the structural diversity of ribosomally expressed peptide libraries and create exciting opportunities for the development of new peptide ligands with unique conformations and modes of action.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research) under JP19am0101090 to H.S., and KAKENHI (JP 19H01014 to S.S, M.W. and Y.G.; 16H06444, JP17H04762, JP18H04382, JP19K22243, and JP20H02866 to Y.G.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), and by the intramural program of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (NIH), project 1ZIATR000247 to J.I. We thank Dr. M.K. Aitha for CeiPGM.

References

- [1].Northfield SE, Wang CK, Schroeder CI, Durek T, Kan MW, Swedberg JE, Craik DJ, Eur. J. Med. Chem 2014, 77, 248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dougherty PG, Qian Z, Pei D, Biochem. J 2017, 474, 1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Valeur E, Gueret SM, Adihou H, Gopalakrishnan R, Lemurell M, Waldmann H, Grossmann TN, Plowright AT, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2017, 56, 10294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zorzi A, Deyle K, Heinis C, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2017, 38, 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Vinogradov AA, Yin YZ, Suga H, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 4167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tavassoli A, Benkovic SJ, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2005, 44, 2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Heinis C, Rutherford T, Freund S, Winter G, Nat. Chem. Biol 2009, 5, 502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fukunaga K, Hatanaka T, Ito Y, Minami M, Taki M, Chem. Commun 2014, 50, 3921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Jafari MR, Deng L, Kitov PI, Ng S, Matochko WL, Tjhung KF, Zeberoff A, Elias A, Klassen JS, Derda R, ACS Chem. Biol 2014, 9, 443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Urban JH, Moosmeier MA, Aumuller T, Thein M, Bosma T, Rink R, Groth K, Zulley M, Siegers K, Tissot K, Moll GN, Prassler J, Nat. Commun 2017, 8, 1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hetrick KJ, Walker MC, van der Donk WA, ACS Cent. Sci 2018, 4, 458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yang X, Lennard KR, He C, Walker MC, Ball AT, Doigneaux C, Tavassoli A, van der Donk WA, Nat. Chem. Biol 2018, 14, 375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yamagishi Y, Shoji I, Miyagawa S, Kawakami T, Katoh T, Goto Y, Suga H, Chem. Biol 2011, 18, 1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hofmann FT, Szostak JW, Seebeck FP, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 8038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Schlippe YV, Hartman MC, Josephson K, Szostak JW, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 10469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kawakami T, Ishizawa T, Fujino T, Reid PC, Suga H, Murakami H, ACS Chem. Biol 2013, 8, 1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hacker DE, Hoinka J, Iqbal ES, Przytycka TM, Hartman MC, ACS Chem. Biol 2017, 12, 795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Johansen-Leete J, Passioura T, Foster SR, Bhusal RP, Ford DJ, Liu M, Jongkees SAK, Suga H, Stone MJ, Payne RJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 9141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Richardson SL, Dods KK, Abrigo NA, Iqbal ES, Hartman MC, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2018, 46, 172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Huang YC, Wiedmann MM, Suga H, Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 10360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Roberts RW, Szostak JW, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1997, 94, 12297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Nemoto N, Miyamoto-Sato E, Husimi Y, Yanagawa H, FEBS Lett 1997, 414, 405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Passioura T, Katoh T, Goto Y, Suga H, Annu. Rev. Biochem 2014, 83, 727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Passioura T, Suga H, Chem. Commun 2017, 53, 1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tsiamantas C, Otero-Ramirez ME, Suga H, Methods Mol. Biol 2019, 2001, 299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Yin Y, Ochi N, Craven TW, Baker D, Takigawa N, Suga H, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 19193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Suga H, Brik A, Huang Y, Nawatha M, Chem. Eur. J 2020.

- [28].Goto Y, Ohta A, Sako Y, Yamagishi Y, Murakami H, Suga H, ACS Chem. Biol 2008, 3, 120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sako Y, Goto Y, Murakami H, Suga H, ACS Chem. Biol 2008, 3, 241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sako Y, Morimoto J, Murakami H, Suga H, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 7232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kawakami T, Ohta A, Ohuchi M, Ashigai H, Murakami H, Suga H, Nat. Chem. Biol 2009, 5, 888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Takatsuji R, Shinbara K, Katoh T, Goto Y, Passioura T, Yajima R, Komatsu Y, Suga H, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Goto Y, Katoh T, Suga H, Nat. Protoc 2011, 6, 779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Iwasaki K, Goto Y, Katoh T, Suga H, Org. Biomol. Chem 2012, 10, 5783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Tanaka Y, Hipolito CJ, Maturana AD, Ito K, Kuroda T, Higuchi T, Katoh T, Kato HE, Hattori M, Kumazaki K, Tsukazaki T, Ishitani R, Suga H, Nureki O, Nature 2013, 496, 247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Yu H, Dranchak P, Li Z, MacArthur R, Munson MS, Mehzabeen N, Baird NJ, Battalie KP, Ross D, Lovell S, Carlow CK, Suga H, Inglese J, Nat. Commun 2017, 8, 14932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Mizuno A, Matsui K, Shuto S, Chem. Eur. J 2017, 23, 14394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Mizuno A, Miura S, Watanabe M, Ito Y, Yamada S, Odagami T, Kogami Y, Arisawa M, Shuto S, Org. Lett 2013, 15, 1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Mizuno A, Kameda T, Kuwahara T, Endoh H, Ito Y, Yamada S, Hasegawa K, Yamano A, Watanabe M, Arisawa M, Shuto S, Chem. Eur. J 2017, 23, 3159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40]. “anti” means on the opposite side to cyclopropane ring when the peptide backbone is on the plane of the paper.

- [41].Murakami H, Ohta A, Ashigai H, Suga H, Nat. Methods 2006, 3, 357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Zhang Y, Foster JM, Kumar S, Fougere M, Carlow CK, J. Biol. Chem 2004, 279, 37185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Kumar S, Chaudhary K, Foster JM, Novelli JF, Zhang Y, Wang S, Spiro D, Ghedin E, Carlow CK, PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Rogers JM, Passioura T, Suga H, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2018, 115, 10959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Fleming SR, Himes PM, Ghodge SV, Goto Y, Suga H, Bowers AA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 5024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Goto Y, Murakami H, Suga H, RNA 2008, 14, 1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Goto Y, Suga H, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 5040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ohshiro Y, Nakajima E, Goto Y, Fuse S, Takahashi T, Doi T, Suga H, ChemBioChem 2011, 12, 1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Rogers JM, Kwon S, Dawson SJ, Mandal PK, Suga H, Huc I, Nat. Chem 2018, 10, 405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ad O, Hoffman KS, Cairns AG, Featherston AL, Miller SJ, Soll D, Schepartz A, ACS Cent. Sci 2019, 5, 1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Tsiamantas C, Kwon S, Douat C, Huc I, Suga H, Chem. Commun 2019, 55, 7366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Lee J, Schwieter KE, Watkins AM, Kim DS, Yu H, Schwarz KJ, Lim J, Coronado J, Byrom M, Anslyn EV, Ellington AD, Moore JS, Jewett MC, Nat. Commun 2019, 10, 5097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Tsiamantas C, Rogers JM, Suga H, Chem Commun 2020, 56, 4265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.