Abstract

The article offers a qualitative examination of compounded precarity in creative work during the Covid-19 pandemic. Drawing on repeated in-depth interviews with twelve creative workers operating in the creative industries in Ghana, we examine one of the most prevalent practices for navigating, coping with, and managing compounded precarity: that of hustling. We empirically identify and discuss three interrelated practices of hustling in creative work: digitalization, diversification, and social engagement. We present a new way of conceptualizing creative work in precarious geographies by theorizing hustling, and the associated worker resourcefulness, improvisation, savviness, hopefulness, and caring not merely as an individualized survival strategy, but rather as an agentic and ethical effort to turn the vicissitudes of life into situated advantages and opportunities, and even social change.

Keywords: Covid-19, Creative industries, Hustle, Precarity, Creative work, Ghana

1. Introduction

There is widespread agreement that the cultural and creative industries have been one of the economic sectors most severely affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. Although the dynamics of the impact varies significantly across different types of organizations, creative subsectors, and countries, scholars studying creative labour during the pandemic argue that the pandemic has compounded—complicated, intensified and exacerbated—already existing high levels of precarity in the creative sector (Comunian and England, 2020, Eikhof, 2020, Flore et al., 2021). The pandemic, as Banks (2020, p. 650), for example, notes, rather than instigating precarity, “has helped amplify some long-instituted feelings of precariousness.” Assessing the impact of the pandemic on the African creative industries, Joffe (2021, p. 30) asserts that the pandemic “did more than bring regular income streams to a complete standstill; it has made visible the fragility of cultural work and project-based income generation in Africa’s CCIs.”

Many of the current explorations of the compounded precarity of creative labour during the pandemic, come, however, in the form of either informed scholarly commentary on an ongoing affliction (Banks, 2020, Joffe, 2021), or impact assessment reports based on evidence generated from trade organisations, employer associations, or labour unions (Comunian and England, 2020, Eikhof, 2020, Unesco, 2021). In this paper, we offer one of the first empirical examinations of compounded precarity in creative work during the pandemic based on original qualitative research. We draw on repeated in-depth interviews conducted before and during the pandemic with 12 creative workers operating in Ghana’s film and theatre industries in order to empirically examine how Covid-19 has affected their experiences of creative workers and how they navigate precarity.

We found that rather than facing an acute shock from which they must be resilient and bounce-back, workers in the creative industries in Ghana, rather reimagined and reinvigorated already established, well-rehearsed, and durable, yet informal and fragmented, practices of a hopeful going-forward in spite of precarity. In this article, we empirically focus on and theorize the most prevalent practice of navigating, coping with, and managing compounded precarity: that of hustling. When focussing on hustling, the analytical attention is put on the hopeful, resourceful, and inventive actions workers in precarious contexts take to create meaningful lives in spite of daunting economic hardships and health emergencies (Thieme, 2018, Amankwaa et al., 2020, Chułek, 2020). We, thus, theorize the resourcefulness, improvisation, and savviness displayed by creative workers not merely as a survival reaction, but an agentic effort to turn the vicissitudes of life into both individual and communal advantage and opportunity. In so doing, we contribute a novel empirical exploration of coping with compounded precarity during the pandemic to the growing literature on creative work that has examined the multifarious, informal, and hopeful ways in which creative workers deal with heightened patterns of precarity in conditions of protracted crisis such as abject societal fallout, enduring war, and post-industrial economic disintegration (Alacovska, 2019, Chen, 2021, Jamal and Lavie, 2021).

The paper is structured as follows. First, we provide a brief review of the literature on precarious work in the creative industries and the concepts of hustling as a getting-by practice in conditions of enduring and chronic crisis. Second, we present the setting of the research and the methods used. We then proceed to examine the experiences of creative workers during the pandemic. We outline three key practices of hustling—digitalization, diversification, and social engagement—and theorize the underlying characteristics of hustling in compounded precarity.

2. Literature review

2.1. Precarious work in the creative industries

While many forms of work under neoliberal market conditions have become increasingly insecure, work in the creative industries is often presented as a model of precarity due to the prevalence of freelance, temporary, short-term, casual, and undocumented employment (Hesmondhalgh and Baker, 2010, McRobbie, 2016). The focus on precarity within the creative industries emerged in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis (Comunian et al. 2021). Comunian et al. (2021) argue that precarity is connected to four pervasive features of creative work. The first relates to uncertainty in the duration of employment. The nature of work in the creative industries often means that skills are needed for a very limited time, which leads to the widespread use of short-term contracts. The second feature concerns the lack of unions and collectives associated with the increasingly fragmented and individualized nature of work. The third element concerns the policy frameworks for the sector, which have been shown to be inadequate in terms of providing effective regulation and protection for creative workers. The final feature concerns issues of payment for work and the widespread experience among creative workers that contracts do not provide a living wage, this is exacerbated by the widespread use of practices such as “unpaid internships” or “work as opportunity” especially in the early stages of creative careers. These different features of creative work are interwoven and reinforce each other and have important ramifications for the livelihoods of creative workers (Comunian et al., 2021).

Emerging research reveals that issues of precarity within the creative industries have been intensified due to the Covid-19 pandemic (Comunian and England, 2020, Comunian et al., 2021, Joffe, 2021, Banks and O’Connor, 2021, Flore et al., 2021). The closure of theatres, museums, and studios and the cancellation or postponement of festivals and concerts and other events have resulted in “a very rapid drop in employment in the cultural and creative industries” (UNESCO, 2021, p. 5). Generally, the precarious nature of their work has made artists and cultural professionals particularly vulnerable to the economic shocks that the pandemic has triggered (Khlystova et al., 2022). The pandemic has also exacerbated existing disparities. Emerging evidence suggests that around the world “the self-employed have experienced higher levels of income loss and unemployment than other categories of cultural and creative workers” (UNESCO 2021, p. 6).

During the pandemic different countries introduced a variety of governmental support measures to mitigate the negative economic and social impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic (Banks and O’Connor, 2021, Joffe, 2021, Serafini and Novosel, 2020). Several studies, however, point to the inadequacy of this support, arguing that governmental support has been too limited, and too narrowly focused on providing short term relief support such as bailouts (Banks and O’Connor, 2021, Comunian and England, 2020). Moreover, because of the precarious nature of the work and the prevalence of freelancing along with casual, temporary, and part-time work, many creative and cultural workers are ineligible for such support programs as they often do not meet the qualifying criteria (Khlystova et al., 2022).

Research suggests that some cultural organisations, such as certain museums and libraries, have responded by developing different digital responses and/or by temporarily closing down and by using a combination of cost reduction measures and government support to survive under the restrictions of Covid-19 (Raimo et al., 2021, Agostino et al., 2020, Machovec, 2020, Khlystova et al., 2022). Yet, concerns have been raised that “the majority of small businesses, freelancers, and self-employed in the creative industries struggled to adapt to new changes and be resilient” (Khlystova et al. 2022, 1195). Khlystova et al. (2022) suggest that workers within certain subsectors of the creative industries (such as the music industry, festivals, cultural events, and theatres), were especially ill-equipped to cope with the pandemic. Due to a lack of response capacity (including lack of digital capabilities) and because of the precarious nature of their work, many of these creative workers were ostensibly “forced to suspend their business activities temporarily or indefinitely, and/or had to seek temporary employment to replace the loss of income” (Khlystova et al. 2022, p. 1203).

In this paper, we mobilize the concept of hustling to understand how creative workers have navigated the compounded precarity of Covid-19 and what actions they have taken to overcome challenges and seize new opportunities. In the following section, we outline what hustling is and why it is a useful analytical lens.

2.2. Navigating precarity: Hustling

Recent research on creative work, especially on “precarious geographies” (Waite, 2009) has shown that despite abominable levels of precarity and radically uncertain conditions of work in the sector, creative workers develop and pursue hopeful and agentic strategies for coping with precarity (Alacovska, 2019, Chen, 2021, Jamal and Lavie, 2021). Such scholarship has refused to cast creative workers as endlessly bounce-backable, resilient, and pliable subjects able to overcome crises by effortlessly dealing with precarity and returning to a state of stability, plenty, and fame. Instead, emphasis has been put on the mundane, diverse, and informal array of making do practices, getting-by tactics, and efforts at sustaining a life worth living (Alacovska et al., 2021b) in conditions of chronic, protracted, and all-pervading precarity, economic vicissitudes, and hardship. In this article, we conceptualize hustling by drawing on geography, business studies, and sociology scholarship to elucidate the practices of making do and getting by in spite of debilitating systemic and structural conditions.

Hustling is the skill of getting by in precarious situations. Above all, the concept has been used to show how marginalized people creatively and entrepreneurially work with the resources they have available to them to build lives that they personally find meaningful—whether that is through semi-legal dealings and small-time crime in urban “ghettoes” (Hall et al., 1978) or gig work in the platform economy (Carter, 2016, van Doorn and Velthuis, 2018). What unites these diverse activities as hustling is the savvy resourcefulness and hopeful future-orientation displayed by the actors who navigate their precarious present to both create a life worth living in the present and build a better future. Hustling is not simply coping, but rather a way of actively working to find beneficial outcomes in uncertain situations (Alacovska et al., 2021a). The ability to improvise including “the ingenuity and flexibility to maintain and enhance self-respect through economic activity” is critical to hustling (Chułek, 2020, p. 343). Thus, hustling is “more than mere opportunism rooted in social and economic survival” (Thieme et al., 2021, p. 10). A cornerstone of the hustling approach is to recognize both the precarious conditions through which workers hustle and their agency to build meaningful lives and careers through their practices of hustling. It, thus, avoids either victimizing or romanticizing marginalized workers (Chułek, 2020, Thieme, 2018).

Within the geography literature, hustling has been most strongly associated with young people navigating uncertainty in African urban environments (Amankwaa et al., 2020, Munive, 2010, Muthoni Mwaura, 2017, Thieme, 2013, Thieme, 2015, Thieme, 2018), and how they “seize opportunities to navigate uncertainty, earn an income, and follow‐up desired aspirations or occupational choices” (Amankwaa et al., 2020, p. 364). Through hustling, marginalized workers—whether marginalized by age, poverty, race, gender, or other attribute—claim the space to work and succeed on their own terms (Thieme, 2013). While they may be looked down upon (by authorities, by society, by their families) hustlers “view hustling as offering them a good life on their own terms, and enabling them to maintain a status in society even in difficult circumstances” (Muthoni Mwaura, 2017, p. 54).

Business scholars have recently deployed the concept of “entrepreneurial hustle” to describe entrepreneurs’ immediate actions that “are intended to be useful in addressing immediate challenges and opportunities under conditions of uncertainty” (Fisher et al., 2020, p. 1002). Here the concept is, thus, not confined to the actions taken by “marginalised” actors but is used to include the actions taken by entrepreneurs, who are operating under conditions of uncertainty in their business operations. This conceptualization includes the sense that “probabilities of alternative outcomes are impossible to quantify” and “the future is unknowable” (Fisher et al., 2020, p. 1003). Entrepreneurial action usually takes place under conditions of great uncertainty. Not only is the decision to pursue an entrepreneurial opportunity highly uncertain, so too are the outcomes from each action along the way.

The concept of hustling has also been deployed in creative industries research (Idriss, 2021, Mehta, 2017, Steedman, In press, Alacovska et al., 2021a, Steedman and Brydges, In Press), particularly to counteract the negativity that has characterised much of the creative industries scholarship that has depicted creative workers as hopeless dupes caught-up in a vicious-cycle of bad jobs (Duffy, 2017, McRobbie, 2016). However, despite the growing interest in understanding the role of hustling in creative work, there is a need to further deepen our understanding of hustling as a particular response to the Covid-19 pandemic. In this paper, we identify-three interrelated modes of hustling as responses to the pandemic.

2.3. Covid-19 and precarity in the Ghanaian CCIs

The first Covid-19 positive cases in Ghana were officially reported in early March 2020. The government of Ghana eventually closed its air, sea, and land borders (Khoo, 2020). The government also implemented a three-week lockdown of major cities: the Greater Accra Region where the capital city is located and Kumasi, its second largest commercial city. Following a total lockdown, schools in Ghana were ordered to close, church and social gatherings including live events were banned (Nyabor 2020). As a consequence, museums, performing arts, live music, festivals, cinema, etc. were severely affected by social distancing measures (Madichie et al., 2020, Khoo, 2020). The abrupt drop in revenues put their financial sustainability at risk and resulted in reduced earnings for workers and lay-offs with repercussions for the value chain of the industries (Khoo, 2020). Creative entrepreneurs began to speak out about the crippling effects of the local (as well as global) lockdown and social distancing measures on their businesses through various forums and seminars as well as news outlets.

Despite the severe impact on the creative industries, economic support programs for the sector in Ghana have been inadequate to protect its workers and entrepreneurs. The “Nkosuo” program, with an initial capital of GHS90 million (approximately 8,883,000USD) from the Mastercard Foundation and NBSSI, and additional investment from other donors and institutions provided financial assistance, in the form of grants and soft loans to eligible enterprises via participating institutions like banks, microfinance, mobile lenders, NGOs, and Business Development Services. Even though the “Nkosuo” program had a one-year moratorium and a two-year repayment, most “qualified” creative entrepreneurs were hesitant to take the loans available, because of uncertainties about their ability to pay them back. These sentiments were expressed during a forum organized by the Ghana Culture Forum and the UNESCO Mission in Ghana on the challenges of Covid-19 on creative entrepreneurs. As creative industries in Ghana are largely informal, the various formal measures put in place were unfavourable to creative entrepreneurs.

The weak support of the creative industries during Covid-19 compounded the already limited support they received prior to the pandemic. Over the years, stakeholders in the industry have seen the interest of government in the creative industries increase and wane, with each successive government unable to put the required foundational structures in place to enable sustainable growth (Bosco, 2017). Even though creative entrepreneurs through their individual efforts have created and sustained what looks like a sprawling creative industry, the lack of structural support and understanding of the industry’s contribution to the Ghanaian economy is a major challenge. As a result, the creative industries in Ghana occupy a position described as “emerging,” with no consistent structures (policy and industrial), across the cycles of artistic production and commercialisation of output (Langevang, 2017, Bosco, 2017, Alacovska et al., 2021a).

3. Methods

The paper is based on repeat interviews with 12 creative entrepreneurs operating in three cities in Ghana: Accra, Kumasi, and Tamale. Immediately prior to the large-scale global lockdowns in March 2020, we were conducting a qualitative study of creative entrepreneurs in film and theatre across four regions in Ghana, with a particular focus on the cities of Accra, Kumasi, and Tamale. For this larger study, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 55 creative workers. As the crisis continued, we saw an urgent need to follow-up with these participants in Ghana to understand how the pandemic was affecting them and how they were responding to it. Thus, we began this study, which ended with a total of 12 interviewees, each of whom had been interviewed previously as part of the larger study.

When selecting interviewees for the follow-up study, we aimed for as much demographic diversity as possible (see Table 1 ) and, more importantly, we selected creative workers using a diversity of business models in the film and theatre industries. For example, we included creative workers using highly digital business models and those without digital experience, and creative workers running businesses that were profitable before Covid-19 as well as those with struggling and/or developing businesses.

Table 1.

Participant demographics.

| Pseudonym | Age | Gender | Education | Marital Status | Children | Primary Creative Field | Years of Practice | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rami | 28 | Male | Film school certificate | Single | 0 | Film | 5 | Tamale |

| Antonia | 40 | Female | Master’s degree | Married | 1 | Theatre | 3 | Tamale |

| Jacob | 32 | Male | Polytechnic | Single | 1 | Film | 8 | Tamale |

| Lucas | 38 | Male | Master’s student | Married | 2 | Theatre | 13 | Kumasi |

| Esther | 35 | Female | Undergraduate student | Divorced | 3 | Film | 8 | Kumasi and Zuarungu |

| Selwyn | 45 | Male | Undergraduate degree | Married | 4 | Media | 15 | Kumasi |

| John | 50 | Male | Polytechnic | Married | 2 | Film | 24 | Kumasi |

| Sheila | 43 | Female | Undergraduate degree | Partnership | 1 | Film | 12 | Accra |

| Commander | 33 | Male | Undergraduate degree | Single | 0 | Theatre | 10 | Accra |

| Paul | 34 | Male | Undergraduate degree | Single | 0 | Film | 15 | Accra |

| Christopher | 28 | Male | Undergraduate degree | Single | 0 | Theatre | 6 | Accra |

| Adwoa | 29 | Female | Master’s degree | Single | 0 | Theatre | 8 | Accra |

Recruitment for the initial large study was mainly done through snowballing with the assistance of key gatekeepers. Interviewees for the follow-up study were purposively selected. Not every-one who initially agreed to an interview was interviewed due to scheduling difficulties. The interviews took place during May and June 2021. During this period, the lockdown had been lifted but a range of restrictions such as social distancing and a limit to the size of public gatherings were still in effect. Interviews were all conducted remotely either using WhatsApp voice calls or regular phone calls. Interviews lasted from 45 to 60 min. Network difficulties presented some challenges for the interviews as calls were frequently interrupted due to poor data connections and sometimes had to be re-scheduled for alternate days to establish a working connection. Conversation sometimes flowed less smoothly because of these technical difficulties. However, because the researchers had already established a rapport with the interviewees through previous in-person interviews, these technical challenges could be overcome.

A semi-structured interview guide was used and was structured around key themes such as: how the pandemic had changed work in film/theatre in their cities, how the pandemic had affected their businesses, opportunities presented by the pandemic, how they were navigating the new situation created by the pandemic and what had helped them get through difficult/uncertain times, how the pandemic had made them feel, and their outlook for the future. Because we had interviewed these participants before in detail about their businesses and entrepreneurial strategies, we could also ask specific follow-up questions and see how activities and plans that were taking place in January-March had changed as a result of the pandemic.

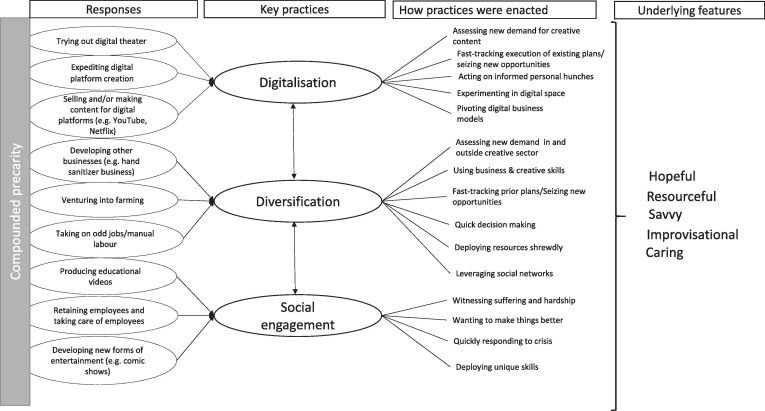

All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were analyzed thematically using NVivo. We first coded the data with attention to how the creatives experienced Covid-19 and how they responded to the crisis. The various responses identified were then aggregated into three pervasive practices: digitalization, diversification, and social engagement. While exploring these practices further, the concept of hustle emerged as a key theme. Going back and forth between the data and the theoretical concept of hustling we reiteratively coded the data to tease out firstly how the practices were enacted, including the key skills and resources needed to make hustling happen, and secondly, the key characteristics and underlying features of hustling in the context of compounded precarity. The process of data analysis is presented in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Coding chart.

The research participants ranged in age from 28 to 50 and included 4 women and 8 men. In the Ghanaian context, the participants are relatively well-educated with the majority having pursued post-secondary education at universities or polytechnics. Half of the respondents worked mostly in film while the other half worked mainly in theatre. However, the boundaries between occupations in these industries in Ghana are highly porous and it was extremely common for a producer to also be director, an actor, an editor, or any number of other activities. Additionally, the boundaries between film and theatre were also highly porous—this was especially true for those who defined their primary business as a theatre business. Most primary theatre producers also worked in filmmaking at least some of the time. On the other hand, those who defined themselves primarily as filmmakers often did not work in theatre. All the respondents were self-employed while a few were also engaged in waged employment. Studying the responses to Covid-19 by creative workers in film and theatre in Ghana is interesting since both sectors are very significant to the Ghanaian society. While it is the case that both sectors have been affected, the assumption is that they may have been differently affected, with theatre being particularly affected as “the more physical presence and social interaction are central to the cultural experience, the more badly hit they will be” (UNESCO, 2021, p. 15).

3.1. Findings: Hustling in the compounded precarity of Covid-19

All the creative workers we spoke to expressed that the Covid crisis had impacted their work adversely and significantly disrupted their businesses. For the theatre practitioners, who all depended on live audiences, the lockdown completely challenged their ways of operating. Commander, who had 10 years of experience in theatre both as an actor and producer, explained that because of measures enacted to curb the spread of the virus people were not supposed to meet and thus “you can’t do any shows for now” which “has really had a very bad effect on our business because, you know, the kind of work that we do has to do with social gathering.” At the time of the second round of interviews, it had just been announced that public gatherings of up to 100 people would be allowed. This news was, however, little consolation for theatre practitioners, like creative director Christopher, who usually engaged with much bigger crowds (and needed bigger crowds for his shows to be profitable):

On a personal level now, every day I pray that one day this whole thing will be over and I can go back and be doing what I do. Because recently when they announced that we could have events, other programs and so on, that we were allowed to gather 100 people, for me I laughed because the smallest number of people you can have at a program of our magnitude is maybe three to four hundred.

Filmmakers also expressed the view that they had been adversely affected by the pandemic, although in slightly different ways. The closure of the cinemas had an effect on the few that had films featured there, but it was more the inability to shoot movies under the Covid restrictions, which implied that they had to halt production and change their plans.

Covid-19 is by no means the first crisis that Ghanaians have had to deal with, and the creative industries were already fragile and weak prior to the onset of the pandemic. The creatives often remarked that even before Covid-19 they were already in a recovery mode. In describing the “protracted hustling” of youth in two Ghanaian cities, Amankwaa et al. (2020, p. 366) found that youth “are often caught in a cycle of recovery and strategising. They have to recover from a setback to their plans, using time and resources to establish a new strategy to achieve their goals, only to fall prone to another setback they need to recover from. This is invariably followed by an attempt to establish a new strategy.” Likewise, for the participants in our study, Covid-19 was the latest setback from which they had to recover, and their response of hustling to develop new strategies and opportunities was also in line with longstanding ways of dealing with uncertainty and precarity. In response to questions about how they coped with Covid-19, many of the participants, such as Esther, responded “What can we do? We’re managing!” The expression “we’re managing” is a common expression among Ghanaians—especially among the young generation—used to express their efforts to make the best of their situation and navigate the uncertain situations of their everyday lives and their futures (Langevang, 2008). Christopher, like many others, had initially felt paralyzed by the pandemic situation.

It has really affected me because most at times, I feel like I’ve been at home. I take my laptop and say 'oh, let me write something' and I just realize that when I write and I get somewhere I get stuck. It’s like I can’t even think. Like nothing comes. You see for we writers we are moved by things that are around us. And this happen to be that majority of my time is spent being indoors. Which is even having an effect on my health.

With time, however, despite the extremely challenging situation, they all emphasized that they had to find ways to keep going. While uncertainty was extreme during Covid-19 and most participants spoke at length about increased stress levels, anxieties, and a deep sense of uncertainty these creative workers were nevertheless confident that they would find a way through the crisis. They were not ready to give up. In the words of Lucas:

Now what I’ve come to accept is that there are no certainties. You know, but what I am also sure of is that my team and I are not going to quit, we are not going to go give up. We are in it for the long course so we just have to figure… we will figure it out. There are no certainties.

Rather than look to the future with fear, Lucas saw it as a space of possibility because he was willing to bet on himself and his team and believe that they would “figure it out.” This kind of actively hopeful orientation is a key characteristic of hustlers (Alacovska et al., 2021a), and it was a key resource they could mobilize to cope with the extreme crisis of Covid.

Hustling requires a certain attitude, one that can be summarized as “a stomach for risk, a heart for challenge, and an eye for opportunity” (Steedman and Brydges, In press). Ghanaian creatives clearly had this attitude, as we can see with Sheila:

I think one of the things that this period has really challenged me to do is to do some writing in a way that I can still go back on set and shoot. As a writer I’m using the pandemic as a backdrop to some of my stories and so if I could shoot with people still wearing mask, I mean and still practicing social distancing and still shooting my story. So it is forcing me to be able to come up with all these ideas. So I am very hopeful.

She was “forced” to come up with new ideas but through her improvisation and resourcefulness (e.g. shooting a Covid story so all mandatory Covid precautions could be observed) she could keep her business going. She saw precarity as a space of creative possibility and thus was hopeful rather than despairing.

With this hopeful mode of being, our participants were able to recognize that the Covid-19 pandemic presented them with opportunities and thus they pivoted their business models in order to seize these opportunities and keep “the show going.” Commander said:

I have always been tough from day one. I believe that there’s nothing that happens that should bring you down. You should just have the mentality to keep pushing, to keep going […] I think it got to a point me myself I was scared, I was like that ‘wow!’ These businesses are going to shut down and it’s gonna be lockdown, you can’t go anywhere, and you can’t do anything. But then, after some time we started seeing another way to go over things instead of just staying home and behaving like everything has come to a standstill. We can’t complain but rather look at the alternative way to solve the whole thing.

Our participants described experiencing a pressure and impetus to remain active, stay relevant, and find some kind of response to the crisis. Like Commander, they shared a mentality to “keep pushing, to keep going.” With their attitudes of hopeful opportunism in place, they took action. That is, they began hustling.

The three most widespread responses to the radical uncertainty of Covid-19 identified in the data were fortified attempts at digitalization, greater diversification, and deepened community engagement. We will discuss each response in turn while also noting that these responses are entwined in the practices of each creative. They needed to enact each mode of hustling in order to sustain a liveable life in compounded precarity.

3.2. Digitalization

Amidst the crisis, creative workers were all compelled to either initiate or enhance their digital presence. They digitalized in an attempt to find new revenue streams for their businesses (often continuing existing attempts from before the pandemic). Digitalization was a key mode of improvisation (Chułek, 2020) to capitalize on new opportunities. As Hinson et al. (2020) assert, for creative workers in Ghana during Covid-19: “It is either you join, or you go hungry.” Jeannotte (2021, p. 4) describes how globally “both creators and audiences made a rapid pivot to digital means of creation and distribution.” Across the world, “the digital capabilities of firms and their ability to adapt were crucial components of resilience strategies for the Covid-19 pandemic” (Khlystova et al., 2022, p. 1201).

The filmmakers in Ghana gauged the film distribution environment and thought that the Covid-19 crisis had increased the demand for creative content since people were spending considerably more time at home due to governmental restrictions and fear of contracting and spreading the virus. Sheila said:

It has been really brutal, and then the cinemas are still shut, but the good side is if you do have content now, you know, there is a possibility you are able to sell it and sell it to some very good platforms. People are at home and they are watching stuff. I’m sure a lot of people get on Netflix every day to watch and Netflix would need content to feed the demand.

This increase in demand for new content presented an opportunity for those who had already made content, which was ready for distribution. Sheila seized this opportunity immediately by selling her latest film to Netflix, where it had its worldwide premiere during the pandemic. John, the head of a film producers association, also saw an opportunity in the pandemic. He thought most Ghanaian consumers would have difficulty accessing existing streaming platforms such as Netflix because of their prohibitive cost both in terms of subscription fees and data usage (Dovey, 2018, Lobato, 2019). He, thus, saw an opportunity in creating a Ghanaian specific film platform, targeting a mass Ghanaian market. Prior to the pandemic he had plans to launch such a platform, but the pandemic provided the impetus for him to take immediate action:

So I realized that because those Ghanaians who have a Netflix subscription belong to the elite class. […] So we reckoned that with a local alternative, we will ensure that a lot of Ghanaians subscribe to it. […] Covid has taught us that now is the time; we can no longer wait. Let’s us get our platform so that the average Ghanaian can pay a token and watch which ever film he or she wants to watch.

John fast-tracked the execution of his existing plans to create a new online platform for average Ghanaian viewers. Uncertainty “is generative in the sense that it opens opportunities for entrepreneurial action, stimulating market innovation and value creation” (van Doorn & Velthuis, 2018, p. 189), and this was true of both Sheila and John who were strategic about seizing new opportunities or fast-tracking existing plans in the face of compounded precarity.

Likewise, in the radical uncertainty of Covid-19, creatives developed new innovations in theatre. Some theatre producers were experimenting with staging plays digitally—for example on social media platforms such as Facebook and YouTube—since it was impossible for them to stage plays in theatres with live audiences. Showing theatre online was a completely new avenue for the theatre producers in our study. At the time of our interview, Commander was about to stage a virtual play:

People are going to see it on social media, on Facebook, on YouTube and then we are doing collaboration with some TV stations to pick it up to show it. So, people can see it right in the comfort of their homes and still enjoy theatre.

Commander quickly pivoted from making live theatre to experimenting with digital theatre. Antonia, a theatre producer in Tamale, was of the same view as Commander, and felt that although “for theatre you need an audience” it could be possible to change the way theatre was presented, potentially even over the longer term: “Can we do a virtual theatre? Can we do something else? And even after Covid can we do something for the audience, something virtual, even if they are not there?”, she pondered. Attracting paying audiences for dramatic theatre is very difficult in Ghana and even before the pandemic theatre was only profitable in Accra (no theatre producer in Tamale or Kumasi was making a profit staging plays). Some of our interviewees felt that expanding the audience through virtual theatre thus could be an interesting new revenue stream—one that could both help them through the short-term crisis of Covid-19 and address the longstanding industry precarity caused by the lack of paying audiences for theatre. This attempt at creating new revenue streams was forward looking and a means of hustling through precarity to build the foundation for later success in the creative industries (Mehta, 2017) while their efforts were characterized by a high degree of improvisation, trial-and error, with limited prior preparation or planning.

However, digitalization proved not to be a panacea for the creative workers but rather presented a range of challenges because they were operating under severe resource constraints with completely new technologies and unfamiliar business models in unproven and uncertain markets. They needed to rely on their own resourcefulness to create new content and their own savvy to assess what kind of content would be most profitable. Before Covid-19, filmmakers had found it nearly impossible to monetize online distribution, except for a handful of upmarket filmmakers such as Sheila. Most filmmakers in Ghana “do not have access to the resources and expertise required to produce, promote, or stream cinema-quality DV [digital video] movies” (Garritano, 2017, p. 201). Challenges that predated the pandemic endure—such difficulties include, for example, accessing the equipment needed to make Netflix-quality films.

Theatre producers also had challenges. They spoke about how their performances are usually ignited by the intimacy and spontaneity of their live audience and the “the vibe and the energy” of their co-presence and interactions, which they were not convinced would be possible in virtual theatre. Some also voiced concerns that, if they were not successful with their online ventures, this could negatively affect their name in the industry in the long run. The largest challenges, however, concerned how to make money out of virtual theatre.

The negative part of the whole thing is that you don’t do it for the money but then for the love of the theatre. You know, to keep people happy, to make sure that people don’t stop falling in love with the theatre, we keep the show going. So, in all it is good. We are still making people happy. The disadvantage part is that we are not getting any money because we don’t get to collect any gate fee. We don’t get to do anything. (Commander)

While some, such as Commander, felt they could create theatre online, others were not convinced. Christopher had pivoted, instead, to making digital content unrelated to theatre. He had never previously made content for the internet, but said as a result of the pandemic “we are being forced to move online.” At the time of the interview, he was about to start shooting a web series while being fully cognizant that digital distribution was not a magical solution but would require “very good camera men,” a large amount of equipment, and capital investment all of which could jeopardize an already insecure income. Christopher assessed that there was demand in the market for online content and he had a hunch online theatre would not fill this demand (because the magic of theatre is in its liveness, for him), and on the basis of this informed hunch (rather than e.g. market research) he pivoted to producing digital content unrelated to theatre. In the face of uncertainty, Christopher and Commander improvised on the basis of informed personal hunches—hunches that took them in different directions.

Importantly, while potential viewers may have been at home during lockdown and in need of new content, that did not mean they had the ability to access digital content. Even before the pandemic, maintaining airtime and data on one’s phone could be a serious challenge (Amankwaa et al., 2020, p. 367), and streaming services are often prohibitively expensive, as mentioned above. This situation was exacerbated by the pandemic. As Christopher noted:

…this is a situation where people are mostly indoors, their source of income has been cut off. So, people are very, I think people are very careful the kind of stuff they need their internet for, their data for.

Common to the efforts of online hustling was the improvised and rapid nature of the actions undertaken. The online hustle was largely haphazard; unfolding without long-term planning, developed strategy, or market research. This type of hustling represents “hustling for learning” (Fisher et al, 2020, p. 1019) in which new things are rapidly experimented with on the basis of quick feedback and informed personal hunches. Each creative rapidly assessed the digital market and then drew upon their own skills, experience, and resources to take the immediate action that they all individually assessed would be best for themselves and their businesses in both the crisis and over the long term.

3.3. Diversification

Hustling emerges in the absence of state and institutional support and involves adding new activities to the work portfolio to manage risk, making the most of scarce resources, and developing a safety net (Muthoni Mwaura, 2017, Thieme, 2013). A common practice among creative workers in Ghana is to diversify their business portfolios and income streams (Alacovska et al., 2021a). This involves both “related diversification” whereby the creative workers hold multiple jobs or businesses within the creative industries or closely related industries (such as the event and entertainment industry) as well as “unrelated diversification” through which creative workers venture into completely different industries (such as trade and farming). While reliance on a portfolio of different incomes was pervasive prior to Covid-19, the pandemic seems to have pushed creative workers into relying more on unrelated diversification.

The creative workers, whose activities were concentrated within the CCIs and related industries, were particularly hard hit financially, since their ancillary jobs were also halted due to the pandemic. When we first spoke to Christopher, prior to the pandemic, he presented himself as “a creative director” rather than just a “theatre director” to emphasize that he does “everything creative” so as not to rely on a single income, as is characteristic of hustlers in African creative industries (Steedman, In press). In the theatre group he is part of, Christopher is responsible for multiple jobs (directing, acting, lighting), and on the side he would also organize the lighting at ceremonies and events such as weddings as well as, on occasion, direct videos and short films for corporations. The pandemic had put a hold on all these activities leaving Christopher in a very difficult financial situation, which forced him to look for opportunities in other sectors:

It [the pandemic] has made me realize that having a source of income in one particular industry, surrounded at one particular place is… as much as I am a theatre person and most of my stuff are around the theatre industry, I should also look for something outside the entertainment sector.

The creative workers who prior to the pandemic had relied on income streams from the film or theatre industry in addition to unrelated industries, focused their energies on their non-creative businesses during the pandemic. Paul, a filmmaker who aside from his film and acting work, had been engaged in various other businesses, put his focus on his real estate activities since these had not been affected by the pandemic:

So right now, the only thing that’s still here is the real estate. I’ve been spending quite a bit of time on that. That’s my biggest investment outside my film and apart from that acting as well, which does well when it comes. So I’ve been in the real estate now just waiting that things will come back to normal.

Creatives with more resources were able to diversify more effectively e.g. focusing on a real estate business is predicated on having a real estate business in the first place. Others were dependent on providing informal labour in order to feed themselves and their families. Filmmaker, Esther, a single mother of three children, narrated how she would accept any kind of casual job to make ends meet during the pandemic.

I have three girls. I told you I have three girls. The money I spend on them in a month is compared to the salary I receive. I spend more than what I receive. So, during this crisis I didn’t get any support from any family member. It’s just my own small, small things I do that’s supporting me. ….for me any work I do, even if you are doing construction work and you call me and you are doing construction, I will come and do. I will come and carry mortar and concrete all to get money and support myself.

Although Esther’s situation was extremely precarious, she was still hopeful and willing to hustle to continue being a filmmaker. No matter what, “I will still do film,” she said. She felt even extreme precarity posed an opportunity because “even when there is crisis, that is when we even get new stories, we get new ideas to create and then to write about it.” Paul and Esther had very different material circumstances, but they shared the same hope for the future and the same willingness to act now to try to make sure that envisioned creative future could come to fruition.

Most of the creative workers who had not already ventured into other industries, were looking for opportunities to do so. During the first interview prior to the pandemic, filmmaker Jacob talked about his plans of entering the farming business to expand his income streams. The advent of the pandemic had intensified this need since he was in a dire financial situation. At the time of the second interview, he was, therefore, in the process of implementing these plans:

Ah, it’s not easy! Prior to this I’ve not had a lot of savings because I’m still growing my company […] So for now I’m just living on the little I have, which is almost exhausted. But what I’m doing is that I’m going into farming, yeah I want to try some maize and some groundnut alongside this thing [filmmaking] hoping things get better. Yeah that’s what I’m doing right now. I’ve seen the chiefs they are working on my land.

Jacob fast-tracked his existing plans to diversify into farming. The creative workers were savvy and opportunistic regarding the sectors they ventured into. Farming and the selling of food stuffs were common areas for diversification, since they saw that the demand for food was not going down as a result of the pandemic.

The pandemic also gave rise to completely new market demands that entrepreneurs could cater to. Selwyn told us how his media house, which includes a satellite television station and an app for local language film content, had ventured into first the advertising of—and later also the selling of—hand-sanitizers. Asked why he would venture into this completely different kind of business, he explained that in a situation where there was no institutional support, people needed to seize opportunities and diversify their businesses in order to stay afloat. As Selwyn stated “if you are a businessman or businesswoman, you need to also focus on certain things because that is where the attention is now.” In the context of Covid-19, attention was on hygiene, and, thus, he made a quick decision to sell hand-sanitizer. The decision was opportunistic, but also grounded in care for his employees:

We are just diverting a bit but still we are doing the [media] business. And we are just diverting a little bit to also get something to pay our workers. Other than that, you have to let some of the workers go home […] With this, you can be able to gather something and also pay them.

Selwyn identified a new demand (enhanced hygiene) and through deploying his resources shrewdly (redeploying his workers to new tasks) he could seize the opportunity provided by that demand. Selwyn knew he needed to do whatever it took to keep his business going. He put it plainly: “it’s either you do a different job or eat all your money.” Achieving his goal of keeping his station open required a multi-pronged approach. In addition to diversifying into sales, he also drew on his social network to develop new TV content to compensate for the content he could not film because of pandemic restrictions (e.g. he could not film reality programs that required crowds). Specifically, he drew on his religious network to have pastors speak on his channel, sometimes for several hours a day. As he said, “we are going to intensify all the strategies we have to make it work,” to survive and grow the business. Maintaining a creative business required diversifying outside the creative industries during the pandemic, and creatives needed savvy and resourcefulness to make it happen.

Making rapid decisions and taking swift actions when diversifying their business portfolios also included leveraging their social networks. Commander was able to open up a new line in his theatre business because he could draw on a very strong network of contacts through a theatre group he had been part of for more than a decade. In his case he was able to shoot a 13 episode comedic TV series. They were able to cooperate to fund the production without a guaranteed sale (money would come only if a TV station bought the show and got sponsors onboard) because of their long-established relationship where “we all know that in the beginning nobody is going to pay anyone. So, we do what we call sacrificial work.” They could also bring in a media school to provide the equipment and welfare for the actors because a group member knew the head of that media school. Commander had a tactic of “testing the waters” with new concepts (e.g. a virtual play), he acted on his own hunches but also paid attention to what others in the field were doing and evaluated the response to their actions. This required a close engagement with the field and knowledge of the actors within it.

Diversifying into unrelated industries required them to engage with new people and stakeholders outside the creative sector (e.g. the chiefs for acquiring land for farming, workers knowledgeable about farming), which posed challenges. The importance of social contacts was made clear by Lucas’s failed efforts at diversifying from before the pandemic. He previously had a small-scale gold buying and selling business and a poultry farm. But he did not have the trusted staff necessary to manage multiple businesses properly: “if you are doing poultry and you are not there the boys, they don’t clean the feeding troughs and you come and the birds are dying. So, all of them required me to be present.” From then on, he focused his attention on related diversification in the media industry.

Our findings echo those of Thieme (2018, p. 540) who notes that “hustling assumes the struggle as a condition of urban life, a possibility in its own right.” Although most creatives sought to diversify their business portfolios and jobs so as not to be solely dependent on filmmaking or theatre, they all asserted that they wanted to remain in the industry. At first glance, film and theatre making appear very different from farming and hand sanitizer selling, for example. Farming and selling seem like deviations from a linear creative career, but through the lens of hustling, we can see that they are a vital part of sustaining a meaningful life. Navigating precarity in the creative industries requires mobilizing both creative and business skills (Steedman, In press). The creatives relied on their business savvy to get through the crisis—with their creative skills (e.g. directing and writing abilities) on standby because of the pandemic they seized other business opportunities to keep their businesses afloat until the point in the future where they could return to making creative content. Diversification was not a measure employed to escape the precariousness of the industry but a way to cope with its uncertainty and to be able to weather future crises.

3.4. Social engagement

Many of the creatives perceived that having a positive impact on society was a key aspect of their profession. Socially engaged theatre/film has a long history in Ghana and, for example, was a key component of Nkrumahist nation building in the 1960s (Garritano, 2013, Shipley, 2015). Traditional healing systems in Ghanaian communities have actively engaged the arts through the use of singing, drumming, and theatre, and the arts have a long history of being incorporated into contemporary public health promotion and interventions (Aikins and Akoi-Jackson, 2020). Both before and during Covid-19, the creatives in our study saw their businesses as having a social mission alongside the goals of artistic expression and profit making (see also Langevang et al., 2021). If hustling is a way of building a meaningful life in the precarious present (Muthoni Mwaura, 2017, Thieme, 2018), then caring for others was part of having a meaningful life for Ghanaian creatives. For example, if profit creation had been the (only) goal, Lucas would have closed his theatre division because only the other divisions of his media business are profitable.

The many challenges arising from Covid-19 fortified their determination to make a difference through hustling rather than just staying idle. They were not content to passively witness suffering, but rather wanted to make things better for others through deploying their unique creative skills. Antonia, a theatre practitioner in Tamale explained:

Sometimes it feels weird just sitting without doing anything. Because we always want to be on the run, we always want to impact lives so it’s difficult when you are not working, and you are just sitting down and you feel there’s somethings wrong with you. So, whether we have sponsorship or not, those we can do without the sponsorship, we try to do, yes. So, those are just our little contributions we are putting out there hoping that it will change a life or two.

Several of the creatives we spoke to saw it as their duty to use their creative media to help educate the people about the pandemic and spread information about the directives of the health authorities and the government. To fulfil this obligation, they provided free content for TV, radio, and online distribution. Rami, a filmmaker and the founder of a creative media studio in Tamale, recognised a gap in the information flow concerning Covid-19 in the northern regions of Ghana at the onset of the pandemic and without much planning decided immediately to quickly produce a series of videos to educate people, especially in rural communities:

I consulted my team and we had to remove from our budget the last of our money that was Ghc1500 to produce some videos on Covid-19 and we translated them into twelve Ghanaian languages. So, right now we’ve exhausted our budget.

Rami relies on irregular revenue and donations to run his creative media studio and does not have any systemic support or consistent funding. Despite the significant cost and impact on his ability to carry out the studios’ regular activities, he felt the need to help vulnerable members of his community. The videos highlight what Covid-19 is, its symptoms, means of contraction, and ways of preventing infection. They sought to break “the language barrier in the understanding of the pandemic and reducing fear among people.” The videos were posted on Facebook, distributed via WhatsApp, and audio versions were broadcast on radio to reach those without internet access. Hustling “is an entrepreneurial form of labour which requires the acceptance, and often the embracement, of precarity in the pursuit of personally-defined success” (Steedman and Brydges, In press). Rami embraced precarity because his personally-defined version of success was strongly associated with caring for his community. Rami used up valuable scarce resources because helping others was essential to his idea of good life.

Jacob decided to let 20 local artists, who make educational songs about Covid-19, come to his recording studio and make videos for free as part of their “contribution to creating awareness in the five northern regions” and because they “didn’t want to be idle.” He proudly spoke about the educational effects of these productions. In addition, they had made sign language videos “to also communicate with the deaf and dumb community.” Hustling is an agentic and hopeful way of building a meaningful life in the present while simultaneously trying to build a better future (Alacovska et al., 2021a; Steedman and Brydges, In press; Mehta 2017). We can see this clearly in Jacob’s case. Making a social contribution made his present better (and that of his community), while not staying idle meant he and his employees could keep their skills fresh, potentially gain exposure, and be prepared for income generating opportunities in the future.

While the creatives were severely constrained financially as a result of Covid-19, their social responsibilities towards their extended families, staff, and communities remained. This sense of care and responsibility towards others was at times perceived to be a considerable burden:

You have to continue to buy food, then you have to buy clothing, you have to continue to pay school fees, and if you are running a company you have to continue to pay salary. Because this is the time your people will actually come up to you and they need your help. So there is a lot of anxiety, I have that a lot and sometimes it is scary to look forth and not see anything. Like you don’t know how this is coming together but somehow you will have to find the answers. So it is especially scary (Sheila).

Several of the creatives we spoke to, who employed staff and/or engaged casual labour, said they would go to great lengths in order not to lay off people, and those who were forced to do so regretted this situation. They felt responsible for helping others—both close contacts such as their employees and distant others such as Ghanaians in need of education in a time of radical uncertainty—and quickly responded.

As previously mentioned, Selwyn diversified his media business to also sell hand sanitizer in part to make sure he could retain his workers. Selwyn, also recounted that he was making programs to support the governmental Covid-19 campaign. He said:

You need to work. You can’t close the station. You have to use what is around. So now, everybody is talking about the disease so we are also campaigning and educating our viewers on how they can be able to control themselves and then use their sanitisers, face masks and other things. So, that’s what we are also doing.

While hustling was opportunistic, it did not have to be individualistic. For example, Selwyn’s hustling had multiple objectives: first, to help his community and second, to seize the content generation opportunities provided by the pandemic.

The abrupt closure of activities resulted in sudden loss of revenue opportunities which implied reduced cashflows and difficulties paying for staff and/or other expenditures. However, it was not only the financial losses that were of concern to the creatives, they also lamented the inability to entertain people and help them to deal with the difficult situation.

So, that’s the problem and it has been a huge problem because uhm, that’s what brings the money and that’s what makes people happy. Not the monetary aspect alone but you know, entertaining people and making sure people forget about their problems. Making sure that you share with people to release stress and all that and this is the case we are not able to meet them, we are not able to do anything and it’s very sad (Commander).

Several of the creative workers also saw a role in instilling hope and releasing stress and tensions among people in Ghana. With this aim, Commander had quickly developed a new “comic discussion” concept for TV:

A lot of people’s, you know, their businesses have gone down. […] Some people have been laid off […]. So, we think that we have to get some comic something on tv for people to laugh and to ease tension for people to just laugh and then just believe that life goes on. Covid-19 is here, it will stay for some time. Definitely it is going to go, and life will pick up again.

Commander deployed his unique skills (creating comic programing for entertainment) to make things better for others.

The practices of social engagement that we have identified confirm the findings from other studies examining creative work in precarious geographies. Alacovska (2019) shows that one main way in which creative workers coped with personal economic hardship in the face of post-socialist institutional breakdown and financial crisis was through socially engaged arts where hope for social change abounded and a quest for a better life together persisted despite paralyzing conditions. Thus, hustling can be seen as not merely an individualistic effort at surviving but also at thriving: a solidaristic, caring, and ethical commitment to improve present and future communal life. Similarly, Jamal and Lavie (2021) who studied creative work in zones of protracted conflict in the Middle East, argue that the Palestinian actors do not accept work in the Israeli creative industries merely as a “personal-professional” mode of countering precarity, but as an ethical and agentic opportunity to collectively and hopefully introduce incremental structural and social changes in the cinematic and television representation of national identities and war conflicts.

4. Conclusion

Rather than giving rise to unprecedented forms of precarity, the Covid-19 pandemic has compounded, exacerbated, and amplified patterns of economic hardship and uncertainties long entrenched in creative industries sectors. This paper has examined how creative workers in Ghana have responded to the Covid-19 crisis and coped with the ensuing compounded precarity. Based on the analysis of our empirical material, we have shown how creative workers operating in the Ghanaian film and theatre industries have advanced, intensified and further refined practices of hustling; practices that have long been the mainstay of creative workers’ efforts at attaining sustainable livelihoods and making ends meet, especially in conditions of “precarious geographies” which are marked by chronic precarity and long-term economic and societal crises. Ghanaian creatives were used to entrepreneurially navigating the precarious circumstances of creative work long before Covid-19, which proved to be a key ingredient in their struggle against the compounded precarity brought about by the pandemic.

In emphasizing hustling, we focus on the agentic endeavours undertaken by creative workers who seek to build a liveable present and a hopeful future in spite of a protracted health crisis and economic vicissitudes. Although the severity of the pandemic, and the resulting anxiety, was acknowledged by all our informants, they all refused to “give up” and resign fatalistically to the economic hardship brought about by the health emergency. Instead of being paralyzed by the gravity of these challenges, they swiftly reoriented resources, knowledge, and efforts so that they could capitalize on situated and immediate opportunities. We have shed light on three distinct, yet overlapping and interrelated, practices of hustling: digitalization, diversification, and social engagement. In so doing, we have made four contributions.

First, by providing one of the first empirical explorations based on original data-gathering of how creative workers have coped during the pandemic, we have contributed a contextualized and in-depth qualitative account of coping with compounded precarity, to the rapidly expanding literature seeking to understand the effects of the pandemic on creative work (Comunian & England, 2020; Joffee, 2021; Khlystova et al., 2022). In particular, we have emphasized the processes of hustling as vital mechanisms for enduring in spite of a protracted health emergency and the ensuing financial adversity.

Second, we have emphasized the empirical, analytical, and theoretical usefulness of the concept of hustling for the study of compounded precarity triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic. Practices of hustling have so far remained obscured in the scholarship of creative labour in light of the pandemic, which mainly focuses on Euro-American creative industries. By elucidating the diverse patterns of coping with compounded precarity during the pandemic in “precarious geographies” of the global South, we bring forth knowledge about hustling to existing studies. By employing the concept of hustling we have elucidated the lived and situated dynamics of improvisation, resourcefulness, savvy, hopefulness, and caring that characterise creative work under conditions of deep precarity. As we have shown, hustling is rooted in hope and the desire to act upon that hope in order to effectuate not only individual economic prosperity, but also induce social change and practice care for others. Through the lens of hustling then, coping with compounded precarity necessitates improvisation and openness to experiment with new ways of acting, savvy to identify new demands in the market, and resourcefulness to act on those newly identified opportunities.

Third, we have highlighted the multifarious ways in which creative workers deal with compounded precarity. We have argued that although the practices of hustling are seemingly disparate and diverse, they all constitute the unifying core of creative work. Pursuing work outside of the creative sectors has been common for creative workers (Adler, 2021, Duffy, 2017, Hesmondhalgh and Baker, 2010, Alacovska et al., 2021a), and we have shown that all this varied work must be considered within the parameters of creative industry work. The lens of hustling, with its emphasis on the agentic re-creation of a meaningful life as opposed to the narrower parameters of business or entrepreneurial success allows us to see this. We thus contribute a new way of approaching creative careers and a new path for scholars to follow when studying them.

Fourth, we have brought the socially engaged side of hustling to the fore, something that has been under-examined in the hustling literature to date. Hustling is opportunistic, but as we have shown, it does not have to be individualistic. Part of achieving a meaningful life is caring for others and the creatives in our study were invested in these acts of care (and often made use of the other two key hustling practices of diversifying and digitalizing to support this care work). We have thus foregrounded how hustling can also be an act of care. While certainly being a distinct mode of economic sustenance in times of crisis, hustling is not merely a survival strategy. It is also a communal and ethical commitment to a better life in the face of adversity. The creative workers we interviewed also hustled “for social good” and the collaborative creation of better and enhanced communal life in the face of the pandemic. As Joffe (2021) indeed has suggested, “culture and the arts help us negotiate the human condition in times of crisis and of grief and mourning.”

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Thilde Langevang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Robin Steedman: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Ana Alacovska: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Rashida Resario: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Rufai H. Kilu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Mohammed-Aminu Sanda: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark [grant number 18-05-CBS] (Advancing Creative Industries for Development in Ghana).

We wish to thank all the creative workers in Ghana who participated in the research. We are grateful to the two reviewers and the editor of Geoforum for their valuable comments.

Data availability

The data that has been used is confidential.

References

- Adler L. Choosing bad jobs: the use of nonstandard work as a commitment device. Work Occupat. 2021;48(2):207–242. [Google Scholar]

- Agostino D., Arnaboldi M., Lampis A. Italian state museums during the COVID-19 crisis: from onsite closure to online openness. Museum Manage. Curatorship. 2020;35(4):362–372. [Google Scholar]

- Aikins A.D.G., Akoi-Jackson B. “Colonial Virus”: COVID-19, creative arts and public health communication in Ghana. Ghana Med. J. 2020;54(4s):86–96. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v54i4s.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alacovska A., Langevang T., Steedman R. The work of hope: Spiritualizing, hustling and waiting in the creative industries in Ghana. Environ. Plann. A: Econ. Sp. 2021;53(4):619–637. doi: 10.1177/0308518X20962810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alacovska A., Fieseler C., Wong S.I. ‘Thriving instead of surviving’: A capability approach to geographical career transitions in the creative industries. Hum. Relat. 2021;74(5):751–780. [Google Scholar]

- Alacovska A. Keep hoping, keep going’: Towards a hopeful sociology of creative work. Sociol. Rev. 2019;67(5):1118–1136. doi: 10.1177/0038026118779014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amankwaa E.F., Esson J., Gough K.V. Geographies of youth, mobile phones, and the urban hustle. Geogr. J. 2020;186(4):362–374. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banks M. The work of culture and C-19. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 2020;23(4):648–654. doi: 10.1177/1367549420924687. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banks M., O’Connor J. “A plague upon your howling”: art and culture in the viral emergency. Cultural Trends. 2021;30(1):3–18. doi: 10.1080/09548963.2020.1827931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco, A., 2017. Conversations On the Creative Arts in Ghana eBook. BKC Consulting. https://www.amazon.com/Conversations-Creative-Ghana-Ahuma-Ocansey-ebook/dp/B077NSNVXM.

- Carter, D., 2016. Hustle and Brand: The Sociotechnical Shaping of Influence. Social Media + Society, 2(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305116666305.

- Chen S. Hoping amidst precarity: changing modes of hope in the vicissitudes of a Chinese art village. Sociol. Rev. 2021;69(6):1277–1292. [Google Scholar]

- Chułek M. Hustling the mtaa way: the brain work of the garbage business in Nairobi’s slums. African Stud. Rev. 2020;63(2):331–352. doi: 10.1017/asr.2019.46. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comunian R., England L. Creative and cultural work without filters: Covid-19 and exposed precarity in the creative economy. Cult. Trends. 2020;29(2):112–128. doi: 10.1080/09548963.2020.1770577. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comunian R., England L., Faggian A., Mellander C. Precarity and the Creative Economy; Springer Nature: 2021. The Economics of Talent: Human Capital. [Google Scholar]

- Dovey L. Entertaining Africans: creative innovation in the (Internet) television space. Media Industries Journal. 2018;5(2) doi: 10.3998/mij.15031809.0005.206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy B.E. Yale University Press; 2017. (Not) Getting Paid to Do What You Love: Gender, Social Media, and Aspirational Work. [Google Scholar]

- Eikhof D.R. COVID-19, inclusion and workforce diversity in the cultural economy: what now, what next? Cultural Trends. 2020;29(3):234–250. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher G., Stevenson R., Neubert E., Burnell D., Kuratko D.F. Entrepreneurial hustle: Navigating uncertainty and enrolling venture stakeholders through urgent and unorthodox action. J. Manage. Stud. 2020;57(5):1002–1036. [Google Scholar]

- Flore J., Hendry N.A., Gaylor A. Creative arts workers during the Covid-19 pandemic: Social imaginaries in lockdown. J. Sociol. 2021;14407833211036757 doi: 10.1177/14407833211036757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garritano C. Ohio University Press; 2013. African Video Movies and Global Desires: A Ghanaian History. [Google Scholar]

- Garritano C. The materiality of genre: Analog and digital ghosts in video movies from Ghana. Cambridge J. Postcol. Literary Inquiry. 2017;4(2):191–206. doi: 10.1017/pli.2017.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall S., Critcher C., Jefferson T., Clarke J., Roberts B. Macmillan; 1978. Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order. [Google Scholar]

- Hesmondhalgh D., Baker S. ‘A very complicated version of freedom’: Conditions and experiences of creative labour in three cultural industries. Poetics. 2010;38(1):4–20. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2009.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson, R.E., Madichie, N.O., Asiedu, B.B., 2020. The Impact of Covid-19 on the Creative Industries in Ghana (Article 3; COVID-19 BUSINESS AND SOCIETY SERIES, pp. 1–3). Center for Strategic and Defense Studies, Africa. www.csdsafrica.org.

- Idriss S. The ethnicised hustle: narratives of enterprise and postfeminism among young migrant women. Eur. J. Cult. Stud. 2021;136754942198894 doi: 10.1177/1367549421988948. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A., Lavie N. Hope and creative work in conflict zones: theoretical insights from Israel. Sociology. 2021;00380385211056218 [Google Scholar]

- Jeannotte M.S. When the gigs are gone: valuing arts, culture and media in the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Sci. Humanities Open. 2021;3(1) doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joffe A. Covid-19 and the African cultural economy: an opportunity to reimagine and reinvigorate? Cultural Trends. 2021;30(1):28–39. doi: 10.1080/09548963.2020.1857211. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khlystova O., Kalyuzhnova Y., Belitski M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the creative industries: a literature review and future research agenda. J. Business Res. 2022;139:1192–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.09.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo A. Ghana in COVID-19 pandemic. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies. 2020;21(4):542–556. doi: 10.1080/14649373.2020.1832300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Langevang T. We are managing!’ Uncertain paths to respectable adulthoods in Accra, Ghana. Geoforum. 2008;39(6):2039–2047. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2008.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Langevang T. Fashioning the future: Entrepreneuring in Africa’s emerging fashion industry. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2017;29:893–910. doi: 10.1057/s41287-016-0066-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Langevang T., Resario R., Alacovska A., et al. Care in creative work: exploring the ethics and aesthetics of care through arts-based methods. Cult. Trends. 2021;1–22 doi: 10.1080/09548963.2021.2016351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lobato R. New York University Press; 2019. Netflix Nations: The Geography of Digital Distribution. [Google Scholar]

- Machovec G. Pandemic impacts on library consortia and their sustainability. J. Library Administ. 2020;60(5):543–549. [Google Scholar]

- Madichie, N., Hinson, R., Asiedu, B., 2020. CSDS Africa - Impact Of Covid-19 On The Creative Business In Ghana. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.28825.24168.

- McRobbie, A., 2016. Be Creative: Making a Living in the New Culture Industries. Polity.

- Mehta R. “Hustling” in film school as socialization for early career work in media industries. Poetics. 2017;63:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2017.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Munive J. The army of ‘unemployed’ young people. YOUNG. 2010;18(3):321–338. doi: 10.1177/110330881001800305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthoni Mwaura G. The side-hustle: diversified livelihoods of kenyan educated young farmers. IDS Bulletin. 2017;47(3):51–66. doi: 10.19088/1968-2017.126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nyabor, Jonas, 2020. Coronavirus: Government Bans Religious Activities, Funerals, All Other Public Gatherings. Citi Newsroom, March 15. https://citinewsroom.com/2020/03/governmentbans-church-activities-funerals-all-other-publicgatherings/.

- Raimo N., De Turi I., Ricciardelli A., Vitolla F. Digitalization in the cultural industry: Evidence from Italian museums. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Serafini P., Novosel N. Culture as care: Argentina’s cultural policy response to Covid-19. Cultural Trends. 2020;1–11 doi: 10.1080/09548963.2020.1823821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley J.W. Indiana University Press; 2015. Trickster Theatre: The Poetics of Freedom in Urban Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Steedman, R., In press. Creative Hustling: Women Making and Distributing Films from Nairobi. MIT Press.

- Steedman, R., Brydges, T., In press. Hustling in the creative industries: Narratives and work practices of female filmmakers and fashion designers. Gender, Work Organ. 10.1111/gwao.12916. [DOI]

- Thieme T. The “hustle” amongst youth entrepreneurs in Mathare’s informal waste economy. J. Eastern African Stud. 2013;7(3):389–412. doi: 10.1080/17531055.2013.770678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thieme T. Turning hustlers into entrepreneurs, and social needs into market demands: corporate-community encounters in Nairobi, Kenya. Geoforum. 2015;59:228–239. [Google Scholar]

- Thieme T. The Hustle economy: informality, uncertainty and the geographies of getting by. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2018;42(4):529–548. doi: 10.1177/0309132517690039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]