Abstract

Critical care nurses manage complex patient care interventions under dynamic, time sensitive and constrained conditions, yet clinical decision support systems for nurses are limited compared to advanced practice healthcare providers. In this work, we study and analyze nurses’ information-seeking behaviors to inform the development of a clinical decision support system that supports nurses. Nurses from an urban midwestern hospital were recruited to complete an online survey containing eight open-ended questions about resource utilization for various nursing tasks and open space for additional insights. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for resource type, bivariate analyses using Pearson’s Chi square test were conducted for differences in resources utilization by years of experience, and content analysis of free text was completed.

Forty-five nurses (response rate 19.6%) identified 38 unique resources, that we organized into a resource taxonomy. Institutional applications were the most common type of resource used (35.6% of all responses), but only accounted for 15.4% of respondents’ “go-to resources” suggesting potential areas for improvement. Our findings highlight that knowing where to look for information, the existence of comprehensive information, and fast and easy retrieval of information are key resource seeking attributes that must be considered when designing a clinical decision support system.

Keywords: Nurse, information-seeking behavior, nurse resource utilization, clinical decision support, knowledge repository

Introduction

With an explosion of information and digitization of healthcare systems, new challenges and opportunities have emerged in clinical decision making for critical care nurses, particularly, leveraging updated high-quality evidence in clinical decision making. Nurses play a paramount role in the delivery of patient care.1 Critical care nurses are required to quickly make complex decisions, prioritize patient needs, and coordinate the team of healthcare professionals, often while faced with sub-optimal conditions. Nurse decision-making in the critical care environment is influenced by a myriad of factors including time limits, situational awareness, varying degrees of uncertainty, peer support, nurse experience, nurse education, interruptions in workflow, and roles of other healthcare team members to name a few.2–6

Patients are also becoming more complex with over a third of older patients having multimorbid conditions. 7 The impact of clinical decision making can be life-saving or life-threatening, particularly in hospital-based settings where nurses care for patients at their most complex and vulnerable states.8 Nurses are also vulnerable in that clinical errors may lead to greater incidence of nurse anxiety, stress, burnout, regret, and leaving the profession. 9 Given the importance of nurses’ decisions, the complexity of the patients, the conditions in which nurses work, and the rapid generation of new knowledge, nurses are prime targets for clinical decision support systems (CDSSs). One important factor in designing and implementing an effective CDSS is that the designers understand what information and resources the end-users (i.e., the nurses) utilize and how they utilize it. Thus, the purpose of this study was to survey and analyze the information-seeking behaviors of critical care nurses in an urban level two trauma hospital as an initial step towards creating a knowledge repository for a critical care nurse-based CDSS.

Background

A CDSS is a cognitive aid used to facilitate decision making and may take on many forms including alerts, reminders, monitoring, guideline recommendations, differential diagnosis, or surveillance. 4,8,10 It leverages evidence and links it to patient data to help make real-time decisions. Design and usability have been identified as predominant factors that determine whether the system is harmful or helpful to patients and nurses.8 Though several barriers exist with CDSS implementation, there are several key considerations that may affect nursing systems specifically.

Preceptorship Training and Preference for Peer Resources

One consideration is that a significant portion of nurse’s training is through preceptorships as students and as new nurses. These one-on-one relationships establish information-culling practices and information-seeking behaviors, which heavily rely on their preceptor’s experience, to inform decision making practice. This is one of the contributing reasons why researchers have found that many nurses are reluctant to adopt CDSS’s.11 A recurring theme in the literature is that nurses, nurse practitioners, medical doctors and physicians’ assistants, prefer colleagues as a primary source of information. Peers and colleagues are consistently reported to be the most useful, most accessible, and fastest source of information. 6,12–16 A recent systematic review of information-seeking behavior in hospital nurses found that nurses predominantly relied on Google and peers for patient care information.17 The structure of this apprenticeship-style training in the healthcare profession reinforces this penchant for utilizing peers as a first-line resource.

Complex Decision-Making Among Healthcare Professionals

Another consideration is that the types of decisions that nurses make are nuanced, dynamic, and almost always require knowledge that is operational and logistical, in addition to task-specific and pathophysiologic. Predicting resource use based on profession alone can be inaccurate though as patient care settings, years of experience, availability of resources, and retrieval skills impact all healthcare professionals.18 The question of whether nurses’ information-seeking behavior differs from other healthcare professionals has been raised before and yielded conflicting results.16,19–22 Many have found that there is a significant overlap in the types of information nurses, nurse practitioners, physicians assistants, and medical doctors utilize including information related to patient diagnosis, drugs, treatment, therapy, patient data, education material and instructions for patient, and information about other healthcare providers (e.g. when to seek advice).16,22 Gschwandtner et al. found a notable difference between nurses and medical doctors, that nurses were unique in looking for additional information on psycho-social support of patients.20 Peltonen et al. reports that in day-to-day operations, nurses are responsible for patients, personnel, and materials rather than patient care alone.19 This intuitively makes sense, that a medical doctor must identify the correct diagnosis and treatment, involving an in-depth look at the patient’s cases as well as prognosis, epidemiology, calculations, symptoms, and diagnostic laboratory testing.16 Nurses must coordinate patient care, execute the medical orders as well as determine nursing diagnoses and interventions, provide education, continuously monitor their patients, and assess for changes. Therefore, nurses necessarily draw from different sources of knowledge compared to other professionals and there are differences in how and when resources are accessed. These complex decision-making considerations must be factored into the development of a well-functioning knowledge repository for a CDSS.

Variability of Education in Nursing

Nursing education and training are more variable compared to other professions with considerable differences in pre-licensure educational requirements. For example, some new nurses graduate with a two-year associates degree, a two-year registered nurse degree, a baccalaureate registered nurse degree, or a masters level pre-licensure degree. Differences in education, as well as in years of experience, all factor into how nurses seek information. This variability in nursing highlights the importance of ensuring that a CDSS is designed with specific end-users and context in mind.

Given the rapid expanse of web-based resources, sophisticated applications, and an explosion of new information available, effective clinical decision support is essential to keep abreast of evolving evidence and prevent information overload. However, prior to developing a CDSS to improve decision making, it is imperative to understand how and what information is currently being used. Thus, the purpose of this study was to survey and analyze the information-seeking behaviors of critical care nurses in an urban hospital setting.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Sample

This was a prospective cross-sectional study. Critical care nurses from an urban level two trauma hospital were recruited to complete an online survey, called the Nursing Resource Utilization Survey. Nurses performing in high acuity settings including a cardiovascular intensive care unit and high acuity intermediate/transplant and telemetry step down/transplant units were invited to complete the survey. The target number was 30 respondents. Each unit employs at least 50 nurses (targeted survey response rate 19.6%). Nurse managers from the three units distributed the survey link via email to their roster of nurse employees. Nurses received one follow up reminder email. No compensation was provided for completing the survey. All nurses were informed that participation was optional and did not impact their relationship with the institution, management, or the university. Data collection occurred between March and May of 2020. All data was collected remotely in REDCap, a secure web-based data collection platform hosted at the University of Minnesota. 23,24

Nursing Resource Survey

The survey was designed by the principal investigator and a practicing cardiovascular nurse. The questionnaire was pretested by four practicing nurses. There are no existing resources surrounding nursing decision making, particularly for a specialized area of nursing. This was an exploratory assessment to gain a broad sense of critical care nurses’ responses that could later be used to inform future tool development. There were eight open-ended questions aimed at identifying resources used by practicing critical care nurses, specifically, resources used for medications, evidence-based practice, wound care; health promotion, patient education, and counseling; and population-tasks (such as left ventricular device cares). Additionally, nurses were asked, “Are there any “go-to resources” that you use to help guide your nursing practice?” followed by “Please describe these resources” for a positive response. The final question was free text space for nurses to provide any additional insights (“What other information would you like us to know?”). Survey respondents also reported their unit and numbers of years in practice. No identifiable information was collected. This study was deemed exempt from research by the University’s Institutional Review Board and approved by the hospital’s Nursing Research Committee Board and the health system’s Research Administration team.

Statistical Analysis

Survey responses were collated and reported in frequencies or percentages. Resource types, frequency of reported use, and the percentage of nurses who reported multiple resources per question were analyzed. Bivariate analyses using Pearson’s Chi square test were conducted to investigate the differences in resources utilization based on years of experience as a nurse. Statistical significance was set at 0.05. Quantitative analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY). The open text responses were analyzed using content analysis. All responses provided were analyzed regardless of whether the participant completed the entire survey (11 possible questions).

Results

Sample Characteristics

The response rate was 19.6% (n = 45), including 18 (40.0%) from intermediate care, 16 (35.5%) from telemetry/transplant and 11 (24.4%) from the intensive care unit (ICU). Nurses were asked to indicate years of nursing experience selecting from categorical variables: 0 – 2 years (13.3%), 3–5 years (42.2%), 6–10 years (31.1%), or more than 10 years (15.6%). As expected, there were no nurses with less than two years of experience working in the ICU, given new nurses are often not hired in ICUs. Of the 11 ICU nurses who completed the survey, 45.5% had 3–5 years of experience, 36.5% had 6–10 years of experience, and 18.2% had more than 10 years of experience. From the Intermediate care unit, 18 nurses completed the survey, 16.7% reported 0–2 years of experience, 44.4% had 3–5 years of experience, 22.2% had 6–10 years, and 16.7% had greater than 10 years of experience. Finally, 16 nurses from the telemetry step down unit completed the survey. Of those, 18.8% had 0–2 years of experience, 31.1% had 3–5 years of experience, 37.5% had 6–10 years of experience, and 13.3% had more than 10 years of experience.

Taxonomy of responses

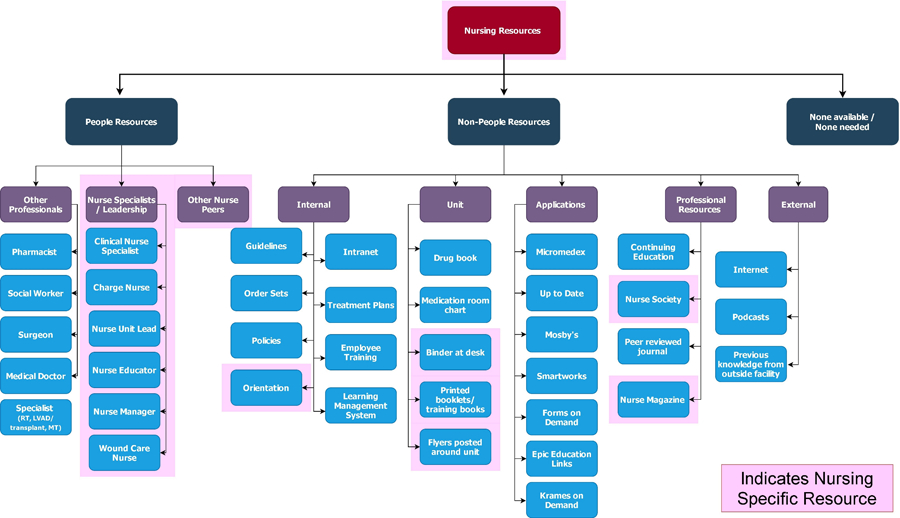

Nurses identified 38 unique resources they utilized for different patient care situations, or patient care domains. These 38 resources were referenced 430 times by the respondents. We collated these responses and organized them into a resource taxonomy consisting of three distinct levels of resources (Figure 1). At Level 1 of the taxonomy, three top-level groups emerged from the data identifying resource categories as: People, Non-People, and None available/None needed. The None available/None needed top-level group represents a group of nurses who feel they either do not have the resources they need or do not require additional resources.

Figure 1:

Resource Taxonomy

At Level 2, under the People group, resource categories were divided into Nursing Specialists / Leadership, Other Professionals, and Other Nurse Peers. Under Non-People, they were Internal resources, Unit resources, Applications, Professional resources, and External resources. At Level 3 are the 38 resources. Twelve resources were nursing specific (as highlighted in Figure 1) including nursing professionals, nursing magazines, societies, and nurse-created training materials (such as unit materials and orientation).

Number of Resources Identified Per Patient Care Domain

Nurses utilized the highest number of resources to find information related to population-specific tasks (e.g., protocols for ventricular assist device cares, atrial fibrillation or other arrhythmias, transplant pre- or post-operative care) identifying 22 different resources. The patient care domain with the second highest number of resources listed was evidence-based practice with 21 different resources identified. Nurses listed the fewest number of resources for oral and intravenous medications (8 and 9 different resources identified, respectively).

Applications Are Most Commonly Used

Institutional applications were the most common type of resource identified by critical care nurses representing 35.6% of all responses. Specifically, these included Micromedex (Truven Health Analytics, Ann Arbor, Michigan), UpToDate (Wolters Kluwer Health, Waltham, MA), SMARTworks (Taylor Communications, Fridley, MN), Krames on Demand (StayWell Company LLC, Yardley, PA), EPIC extensions (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI), and Mosby’s Clinical Skills (Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Nurses with 0–2 years reported the highest percentage of application usage (44.7%) and steadily declining with years of experience (36.7, 33.6, and 30.8% for 3–5, 6–10, and 10+ years; respectively). All respondents reported using an application for at least one patient care domain (Table 1). Of the six patient care domains, applications were the top reported resource for four of them (oral and intravenous medication administration, evidence-based practice guidelines, and health promotion/patient education/counseling) as shown in Table 2. Despite applications being the most utilized (or reported) resource, applications accounted for only 15.4% of respondents’ “Go to” Resources (Table 2). The second highest reported resource were internal institutional resources such as the intranet, internal policies, and procedures followed by specialized, advanced practice, or leadership nurses. This included charge nurses, nurse unit leads (NULs), nurse managers, Clinical Nurse Specialists (CNS), transplant coordinators, LVAD coordinators, nurse educators; wound, ostomy, and continence (WOC) nurses, and advanced practice nurses.

Table 1:

Resource Utilization by Years of Experience

| 0–2 Years | 3–5 Years | 6–10 Years | 10+ Years | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (% of responses) | |||||

| Resource Type | |||||

|

| |||||

| Peers | 2.1 | 5.3 | 8.1 | 7.7 | 6.3 |

| Advanced Practice, specialty, or leadership RNs | 21.3 | 10.7 | 14.1 | 10.8 | 13.0 |

| Non-nurses | 2.1 | 7.7 | 8.1 | 12.3 | 7.9 |

| Internal/Intranet | 12.8 | 18.3 | 16.1 | 16.9 | 16.7 |

| Application-based | 44.7 | 36.7 | 33.6 | 30.8 | 35.6 |

| External | 12.8 | 6.5 | 10.1 | 7.7 | 8.4 |

| Unit Specific | 4.3 | 7.7 | 6 | 1.5 | 5.8 |

| Nat’l Org | 0 | 3 | 1.3 | 12.3 | 3.5 |

| None or not needed | 0 | 4.1 | 2.7 | 0 | 2.6 |

|

| |||||

| Total Responses (n) | 47 | 169 | 149 | 65 | 430 |

Bolded items are maximum percentages by resource type (row)

Table 2:

Resource Utilization Across Patient Care Domains

| Survey Question/ Resource Type | Oral | IV | EBP | Dress / WC | Education | Population specific | “Go-to” Resources | Other Info |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | ||||||||

| Peers | 4.9 | 4.7 | 3.3 | 6.9 | 8.8 | 5.3 | 15.4 | 7.7 |

| APRN, CNS, specialty, or leadership RNs | 1.6 | 1.6 | 18.3 | 36.1 | 0 | 17.3 | 11.5 | 0 |

| Non-nurses | 9.8 | 14.1 | 0 | 13.9 | 3.5 | 6.7 | 7.7 | 0 |

| Internal/Intranet | 4.9 | 3.1 | 21.7 | 20.8 | 21.1 | 32.0 | 7.7 | 7.7 |

| Applications | 73.8 | 67.2 | 31.7 | 11.1 | 45.6 | 9.3 | 15.4 | 7.7 |

| External | 4.9 | 4.7 | 13.3 | 5.6 | 8.8 | 4 | 23.1 | 30.8 |

| Unit Specific | 0 | 4.7 | 3.3 | 4.2 | 1.8 | 17.3 | 7.7 | 7.7 |

| National Organization | 0 | 0 | 8.3 | 0 | 5.3 | 6.7 | 7.7 | 0 |

| None or not needed | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.4 | 5.3 | 1.3 | 3.8 | 38.5 |

| Total Responses (n) | 61 | 64 | 60 | 72 | 57 | 75 | 26 | 13 |

Bolded items are maximum percentages by patient care domain (column);

Oral = Oral medication administration; IV = Intravenous medication administration; EBP = Evidence Based Practice; Dress/WC = Dressing changes and wound care; Education = Health promotion, education, and counseling; APRN = Advanced practice nurse; CNS = Clinical Nurse Specialist

Years of Experience and Resource Utilization

Years of experience had an impact on the different types of resource utilization (Table 1). Newer nurses (with 0–2 years of experience) relied more on external sources, chiefly browsing the internet, whereas those with more years of experience were more likely to use other professionals (e.g., pharmacists, physicians, social workers) and more likely to draw from information obtained from professional organizations (e.g., American Heart Association).

Internet sites included institutional healthcare websites such as the Mayo Clinic and Johns Hopkins, healthcare sites such as WebMD or Medscape, and searches such as Google, Wikipedia, and articles posted on nursing Facebook groups. New nurses reported using higher-level nursing staff (i.e., leadership, specialty, and advanced practice nurses) more than nurses with 3–5, 6–10, and 10+ years. With greater years of experience, there is a shift in resources reported. Nurses with ten or more years of experience relied on non-nurses (surgeons, pharmacists, cardiologists, and social workers) more often than any other experience group (12.3% vs. 8.1%, 7.7% and 2.1% in those 6–10, 3–5, and 0–2 years of experience, respectively). Nurses with ten or more years of experience also cited national and other accredited professional organizations or continuing education as their resources (12.3% vs.1.3%, 3%, and 0% in those 6–10, 3–5, and 0–2 years of experience, respectively). No unit-specific differences were found.

Multiple Resources

Differences in the number of resources reported were tested for significance. There were no statistically significant differences between how many resources nurses listed based on the number of years in practice, though nurses with ten or more experience listed more resources for specific tasks related to their patient population (i.e., cardiovascular specialty resources) compared to nurses with fewer years of experience. Across questions, there was a statistically significant difference in the number of respondents who listed one resource vs. multiple resources, irrespective of years in practice with most nurses supplying just one resource. Nurses reported the highest number of resources for issues related to wound care and dressing changes (question 3) and population specific resources (question 5), regardless of years of experience. Nurses with 3–5 and 6–10 years of experience had the most resources for wound care and dressing changes. No nurses with ten or more years of experience listed multiple resources for wound care/dressing changes or health promotion/patient education/counseling.

Qualitative results

Although the purpose of the nursing resource survey was to identify and quantify which resources were most often utilized, nurses provided additional rich data in the open response section. Nurses identified several areas of improvement including knowing where to look for information, retrieving information, finding information quickly, and finding reliable and comprehensive information for many different types of patients cared for on the unit. Nurses need to have reliable information that is easily accessible and retrievable. These quotes provide insights about the desired attributes nurses seek in their resources. Several nurses indicated that they either needed or provided help finding resources as illustrated in the quotes below.

“Knowing where to look for these resources when starting at the hospital was not part of my orientation process, therefore I don’t know what resources we have other than our policies section on the intranet”

“Often my co-workers are my greatest resource; either directly or to help point my search for information in the right direction.”

“I consider myself rather connected with the hospital’s education resources and am rather proud of the resources available. Many of my coworkers admit to struggling with navigating these resources and rely often on peer guidance and printed resources.”

The quotes below highlight a logistical problem retrieving information that is sent via email.

“We are sent emails with updates about a certain population of patients, but unless we can remember that email or we save the email when we actually encounter this scenario months later there is no actual place we can refer back to.”

“We are sent emails quite frequently about these topics, I archive them so I can reference back to them but there is nowhere that all this information is compiled, in fact we used to have a reference book for much of this that was removed because no one keeps it updated”

Finally, nurses provided salient quotes articulating remaining gaps in reliable and comprehensive information that spans the scope of the patient conditions that they encounter.

“I think it’s helpful to know that there are resources out there, but it has been difficult to find the proper policies for certain procedures.”

“Our institution specific protocols are lacking. Intranet most often utilized as an access point to the lab guide, or outside databases (Micromedex, UpToDate).”

“I feel that there is a significant lack of a reliable place to get information about the many different types of patients that we care for on the unit.”

To summarize, the qualitative responses collected from the open response section of the survey (final question of survey) yielded three important findings: (1) resources are difficult to find; (2) email can present logistical problems with retrieval, and (3) there remain gaps in institutional policies, protocols, and unit/population-specific resources.

Discussion

Nurses have a cognitively demanding role caring for diverse and complex patients. From this study, we have identified 38 different resources critical care nurses utilize in their daily practice. Critical care nurses must efficiently and competently manage these resources in a rapidly changing and critical environment. Assistance navigating these resources, particularly for new nurses, is warranted based on these results. Nurses stated that resources must be reliable, easily accessible, and provide references across a wide span of various procedures and conditions, which has also been found in the literature.17

Peers

It is not surprising then that nurses utilize and value peers as their primary resources in the literature over other resources.4,6,13,25,26 Peers can provide immediate feedback across dynamic patient situations using analytic decision-making, critical thinking, and intuition to inform behavior. 27 For example, Micromedex, the resource mentioned most frequently in this study’s survey results, will quickly provide extensive information on a medication, it’s interactions with other medications, and how to prepare it. A peer will likely know this as well in addition to knowing where the medication is stored, the policy for using the medication, the appropriate tubing to use and where it is stored, and the number for the pharmacy. Peers are not only rich sources of information that span multiple domains of knowledge but also provide operational and logistical-level information.

Contrary to the literature however, in this study, peers (labeled as “other nurses”) only represented 6.3% of the survey responses across the six domains of care, however, when asked about “go-to resources”, peers were the second most reported resource (tied with applications). Thus, there remains a question as to why nurses are not mentioned more frequently in the patient care domain questions but are otherwise frequently utilized. This could be a survey design issue, or a phenomenon related to workflow, peer accessibility, or any number of information culling practices and highlights the need for further investigation. Also, of note, nearly 50% of respondents stated that their “go-to” was a person, the unit, or outside the pool of traditional resources available to them (Table 2). This is evidence that we need a better clinical support system.

Resource Utilization by Years of Experience

Nurses with fewer years of experience reported using external sources, such as the internet, as a resource. Higher utilization of the internet as a resource suggests that newer nurses have less familiarity with either the existence of other resources or how to access them. Without knowledge that a resource exists or if time is limited, it is easier to access the internet rather than search for an application or policy. This practice may yield suboptimal content depending on the credibility of the websites referenced. Utilization of suboptimal online content has been reported elsewhere in the literature citing lack of time and retrieval skills as major barriers to locating high quality resources and evidence. 28 There were 38 resources identified for only six patient care domains. There are likely even more resources yet that critical care nurses utilize in their practice. To learn and remember how to navigate that many resources is overwhelming. It is reasonable that new nurses would turn to the internet for credible information while gaining familiarity with the resources. This cognitive burden and lack of training is reported in literature.16,21

Critical care nurses with the most experience had the highest frequency of reporting use of non-nursing staff. This is likely related to comfort or confidence with other staff. Nurses with more experience are more familiar with non-nursing staff and have a broader perspective on other professionals’ roles and contributions to the care team. It is logical that critical care nurses with more years of experience engage in professional organizations and thus have a depth and breadth of knowledge. Information gathered from conferences and professional organizations are more difficult to access and translate into practice, but likely possessed by critical care nurses who are more experienced and have gained expertise in their specific area of nursing. Thus, years of experience plays a role in resource utilization and must be considered in the design of decision support systems.

Unit Specific Differences

Unit-specific differences were examined, though none were found. One factor that may have influenced this finding is the movement of nurses between the units that were included in this study. Nurses float to the neighboring units (intermediate care and step-down telemetry) and many step-down telemetry nurses move to the cardiovascular ICU and vice versa. Thus, there is likely a cross-training effect, however, the purpose of this exploratory pilot was not to be powered to detect unit-specific differences.

Qualitative Results

The qualitative responses support the notion that critical care nurses benefit from easy to access centralized clinical decision support system that distills and organizes information including unit and population specific data. This survey examined resources used in six patient care scenario and yielded 38 resources. We know that the number of patient care scenarios is greater than what we surveyed, and thus, we can assume that critical care nurses utilize more than these 38 resources in their clinical practice. Despite listing numerous resources, 38.5% of respondents (n = 13) of the final question, “What else would you like us to know?” stated that there were insufficient resources available to nurses (Table 2).

Resource utilization can be a juggling act. A clinical decision support system that is easy to access, easy to use, and unit and population specific will reduce the burden of managing resources as opposed to being one more resource to try to navigate. These results underscore the importance of usability and acceptability in resource design and clinical decision support. Younger identifies barriers to utilizing resources in their 2010 review of the literature citing lack of searching skills and database training were consistently mentioned as barriers to utilizing online information.22 The literature and our findings support the need for an integration of resources, improved usability and accessibility, and information retrieval training.28,29

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Survey respondents were anonymous, therefore any ambiguity in responses was not verifiable. For example, one respondent stated that “email” was a common resource they used. This could be an email from a social worker, nurse educator, clinical nurse specialist, or anyone else. We were unable to determine the exact meaning of this response other than it was a personnel resource.

Nurses who responded may not be representative of all the nurses on the units. Those who responded may check their email more often, have more stretches of downtime during their shifts (as can occasionally occur during night shifts or on weekends), or any number of other reasons. We do not know who completed the survey and if there are distinguishing characteristics between respondents and non-respondents.

Also, there are likely additional resources not captured by this survey. The survey was not exhaustive as to minimize burden and as such, the respondents were asked about specific patient care domains (i.e., medication administration, wound care, population-specific tasks like caring for a left ventricular assist device, etc.). Therefore, there are additional resources critical care nurses utilize regularly for patient care tasks not included in the survey (e.g., resources used specifically for discharging a patient). Though the purpose of this study was exploratory, the above limitation should still be considered in the interpretation of the findings.

Lastly, these results were collected from three units at one urban institution and are not generalizable to other institutions. Further research across institutions and with larger sample sizes are needed to better understand nurse resource utilization. Furthermore, a qualitative research approach in the form of focus groups would contextualize the data and gain greater depth in understanding how these resources are being used.

Conclusion

The resource taxonomy created from the data reveal a wide breadth of resources that critical care nurses use to inform care. Interestingly, the most common types of resources used are not necessarily nurses’ “go-to resources” suggesting potential areas for improvement in the creation and availability of nursing resources used for decision support. Further, nurses highlighted several key features of an effective resource including one that is easy to find, comprehensive, and affords fast and easy retrieval of information. All these elements must be considered in the next steps in designing a clinical decision support system for nurses.

Further investigation into critical care nurses’ information-seeking behavior and resource utilization is necessary to create a robust knowledge repository needed in clinical decision support systems. An efficacious clinical decision support system is, in large part, dependent upon providing the knowledge repository with sufficient information. Contextualizing nurses’ experiences utilizing common resources will enhance usability and transferability across patient care scenarios. The results suggest that further qualitative assessment is needed to gain insight into what resources are used, when, by whom, and why.

Additionally, it is unknown whether these results are reproducible in other settings. Further research is needed across healthcare systems, in non-urban teaching institutions for external validation of these results and to use those findings towards creating a centralized, dynamic, and usable CDSS to support nursing practice. We are working towards this end by incorporating our findings into the CDSS design process.30

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the clinical nurse specialist and nurse managers for their collaboration disseminating the survey. Thank you to all the nurses who took the time to complete this survey.

Source of Funding

This research and REDCap were supported by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grants TL1R002493 and UL1TR002494. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. This study was supported by the Office of the Vice President for Research, University of Minnesota and the University of Minnesota Grant-in-Aid (Proposal #292917). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agency.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arslanian-Engoren C, Scott LD. Clinical decision regret among critical care nurses: A qualitative analysis. Hear Lung J Acute Crit Care 2014;43(5):416–419. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cappelletti A, Engel JK, Prentice D. Systematic review of clinical judgment and reasoning in nursing. J Nurs Educ 2014;53(8):453–458. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20140724-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dougherty L, Sque M, Crouch R. Decision-making processes used by nurses during intravenous drug preparation and administration. J Adv Nurs 2012;68(6):1302–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05838.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nibbelink CW, Brewer BB. Decision-making in nursing practice: An integrative literature review. J Clin Nurs 2018;27(5–6):917–928. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stubbings L, Chaboyer W, McMurray A. Nurses’ use of situation awareness in decision-making: An integrative review. J Adv Nurs 2012;68(7):1443–1453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05989.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seright TJ. Clinical decision-making of rural novice nurses. Rural Remote Health 2011;11(3):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: A cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012;380(9836):37–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60240-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piscotty R, Kalisch B. Nurses’ use of clinical decision support: A literature review. CIN - Comput Informatics Nurs 2014;32(12):562–568. doi: 10.1097/CIN.0000000000000110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boswell S, Lowry LW, Wilhoit K. New nurses’ perceptions of nursing practice and quality patient care. J Nurs Care Qual 2004;19(1):76–81. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200401000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Middleton B, Sittig DF, Wright A. Clinical Decision Support: a 25 Year Retrospective and a 25 Year Vision. Yearb Med Inform Published online 2016:S103–S116. doi: 10.15265/IYS-2016-s034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Piscotty RJ, Kalisch B, Gracey-Thomas A. Impact of Healthcare Information Technology on Nursing Practice. J Nurs Scholarsh 2015;47(4):287–293. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nibbelink CW, Young JR, Carrington JM, Brewer BB. Informatics Solutions for Application of Decision-Making Skills. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 2018;30(2):237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cnc.2018.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall AP, West SH, Aitken LM. Clinical credibility and trustworthiness are key characteristics used to identify colleagues from whom to seek information. J Clin Nurs 2013;22(9–10):1424–1433. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin F, Gillespie BM, Chaboyer W, et al. Preventing surgical site infections: Facilitators and barriers to nurses’ adherence to clinical practice guidelines—A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs 2019;28(9–10):1643–1652. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall AP, West SH, Aitken LM. Preferred Information Sources for Clinical Decision Making: Critical Care Nurses’ Perceptions of Information Accessibility and Usefulness. Worldviews Evidence-Based Nurs 2011;8(4):224–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2011.00221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke MA, Belden JL, Koopman RJ, et al. Information needs and information-seeking behaviour analysis of primary care physicians and nurses: A literature review. Health Info Libr J 2013;30(3):178–190. doi: 10.1111/hir.12036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alving BE, Christensen JB, Thrysøe L. Hospital nurses’ information retrieval behaviours in relation to evidence based nursing: a literature review. Health Info Libr J 2018;35(1):3–23. doi: 10.1111/hir.12204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunt S, Cimino JJ, Koziol DE. A comparison of clinicians’ access to online knowledge resources using two types of information retrieval applications in an academic hospital setting. J Med Libr Assoc 2013;101(1):26–31. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.101.1.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peltonen LM, Siirala E, Junttila K, et al. Information needs in day-to-day operations management in hospital units: A cross-sectional national survey. J Nurs Manag 2019;27(2):233–244. doi: 10.1111/jonm.12700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gschwandtner T, Kaiser K, Miksch S. Information requisition is the core of guideline-based medical care: Which information is needed for whom? J Eval Clin Pract 2011;17(4):713–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01527.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kannampallil TG, Jones LK, Patel VL, Buchman TG, Franklin A. Comparing the information seeking strategies of residents, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants in critical care settings. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2014;21(e2):249–256. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Younger P Internet-based information-seeking behaviour amongst doctors and nurses: A short review of the literature: Review Article. Health Info Libr J 2010;27(1):2–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2010.00883.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)-A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 2019;95(April):103208. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rycroft-Malone J, Fontenla M, Seers K, Bick D. Protocol-based care: The standardisation of decision-making? J Clin Nurs 2009;18(10):1490–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02605.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Offredy M, Kendall S, Goodman C. The use of cognitive continuum theory and patient scenarios to explore nurse prescribers’ pharmacological knowledge and decision-making. Int J Nurs Stud 2008;45(6):855–868. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hicks FD, Merritt SL, Elstein AS. Critical thinking and clinical decision making in critical care nursing: A pilot study. Hear Lung J Acute Crit Care 2003;32(3):169–180. doi: 10.1016/S0147-9563(03)00038-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zigdon A, Zigdon T, Moran DS. Attitudes of nurses towards searching online for medical information for personal health needs: Cross-sectional questionnaire study. J Med Internet Res 2020;22(3):1–11. doi: 10.2196/16133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maggio LA, Aakre CA, Del Fiol G, Shellum J, Cook DA. Impact of electronic knowledge resources on clinical and learning outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res 2019;21(7):1–17. doi: 10.2196/13315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu S-C, Brown RJ, Michalowski M. A Clinical Decision Support System Design Framework for Nursing Practice. ACI Open 2021;05(02):e84–e93. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1736470 [DOI] [Google Scholar]