Abstract

Nanoparticle assembly paves the way for unanticipated properties and applications from the nanoscale to the macroscopic world. However, the study of such material systems is greatly inhibited due to the obscure compositions and structures of nanoparticles (especially the surface structures). The assembly of atomically precise nanoparticles is challenging, and such an assembly of nanoparticles with metal core sizes strictly larger than 1 nm has not been achieved yet. Here, we introduced an on-site synthesis-and-assembly strategy, and successfully obtained a straight-chain assembly structure consisting of Ag77Cu22(CHT)48 (CHT: cyclohexanethiolate) nanoparticles with two nanoparticles separated by one S atom, as revealed by mass spectrometry and single crystal X-ray crystallography. Although Ag77Cu22(CHT)48 bears one unpaired shell-closing electron, the magnetic moment is found to be mainly localized at the S linker with magnetic isotropy, and the sulfur radicals were experimentally verified and found to be unstable after disassembly, demonstrating assembly-induced spin transfer. Besides, spin nanoparticles are found to couple and lose their paramagnetism at sufficiently short inter-nanoparticle distance, namely, the spin coupling depends on the inter-nanoparticle distance. However, it is not found that the spin coupling leads to the nanoparticle growth.

Subject terms: Nanoparticles, Structural properties, Magnetic materials

The assembly of atomically precise clusters into ordered superstructures enables new functional material designs. Here, the authors propose a strategy for linear arrangements of AgCu clusters and explore the consequent transfer and coupling of magnetic spins.

Introduction

Metal nanoparticles can be regarded as an assembly of metal atoms and surface-protecting ligands1,2. The further assembly of nanoparticles enhances or even enriches the properties of sole metal nanoparticles and constitutes a novel type of promising material that is significant not only for fundamental research but also for practical applications2–17. Due to numerous atoms and complex structures as well as instability, it is generally difficult to assemble metal nanoparticles in a controlled and atomically precise way18–20. Even the controlled and atomically precise synthesis of metal nanoparticles has long been a target for the scientific community, and this target has only come into becoming a reality recently after many trials21. Atomically precise nanoparticle assemblies provide excellent opportunities for structure (composition)-property correlation and rational tailoring of their performances, thus attracting extensive interest in recent years22–32. Unfortunately, despite the successful assembly of small metal nanoclusters (NCs) with sizes less than 1 nm33–38, the assembly of atomically precise metal nanoparticles with metal core sizes strictly larger than 1 nm has not yet been reported due to the increasing challenge in synthesis and characterization (assembly without linkers in crystalline phases is not considered herein). To resolve these challenging issues, the linker is one critical factor for consideration. A relatively short (simple) linker is preferred in simplifying assembly and facilitating characterization, and the most ideal linker in this context is a single atom (including charged and uncharged atoms). Cations have been widely applied in previous assemblies;11,17 however, anions such as S2– and N3– have rarely been employed as linkers, especially for the assembly of particles. S2– has a good affinity to metal atoms39,40 and it can be in-situ produced during the synthesis of thiolated metal nanoclusters41. It is possible that the on-site produced sulfur anion acts as a linker to stick the concurrently produced nanoparticles during the synthesis of nanoparticles (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Another advantage of S2– as a linker is that the good affinity of S2– towards metal atoms can enhance or even give rise to new properties for the nanoparticles. Fortunately, for the first time, we successfully assembled nanoparticles into straight chains by using S2– as a linker, resolved the atomic structure by using mass spectrometry and single crystal X-ray crystallography (SCXC), and, more importantly, revealed interesting spin transfer and coupling phenomena, which will be discussed below.

Results

Synthesis and structure characterization

Silver salt was employed as the major metal precursor due to its accessibility, and a second metal, copper salt, was added to strengthen the stability and enrich the properties of the metal nanoparticles. Cyclohexanethiol (CHTH) was employed as a protecting ligand due to its relative flexibility, which is beneficial for S2– access to the metal surface. A kinetical control and thermodynamic selection strategy was applied to synthesize atomically precise bimetal nanoparticles42. Briefly, the synthesis and assembly processes are shown below: a freshly prepared solution of NaBH4 and PPh4Br was added dropwise to a dichloromethane suspension containing AgCHT and CuCl in the presence of triethylamine. After stirring for 6 h at 0 °C, a dark brown solution was obtained, which was rotary evaporated to give a dark solid. This solid was washed with methanol and then dissolved in a mixed solvent of dichloromethane/hexane for crystallization (assembly) (see Methods for details).

The UV/Vis/NIR spectra for the as-prepared materials and the crystals both show a prominent peak at 655 nm and a shoulder peak at 410 nm (Supplementary Fig. 2). Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) was employed to determine the exact formula of the components. The full range of the ESI-MS spectrum (acquired in positive ion mode) is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3a. A series of peaks were observed at approximately 4900 and 7400 Da bearing 3+ and 2+ charges, respectively. Detailed assignments are revealed in Supplementary Fig. 3b, and the isotope patterns for the parent cluster and its fragments match well with the calculated patterns (see Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). The peak of intact cluster ion was found at m/z = 7617.7 Da, corresponding to [Ag77Cu22(CHT)48]2+, and the peak of 3+ charged cluster ion with one missing CHT ligand was located at m/z = 5040.6 Da. The other peaks can be rationally assigned to the fragments, among which two peaks are assigned to [Ag76Cu21(CHT)47 + S]3+ and [Ag76Cu21(CHT)48 + S]2+ (Supplementary Fig. 6), indicating the possible existence of surface S2–. The replacement of the reducing reagent NaBH4 with NaBD4 in the synthesis does not lead to the notable change of m/z in the mass spectrum of Ag77Cu22 (Supplementary Fig. 7), excluding the existence of hydrides in the metallic core. SCXC (vide infra) was used to determine the nanoparticle composition [Ag77Cu22(CHT)48]2+, which was also supported by additional EDX measurements (Ag/Cu/S atomic ratio 1: 0.285: 0.637, in good agreement with the expected ratio 1: 0.286: 0.623, see Supplementary Fig. 8). Below, we will focus on the structure revealed by SCXC.

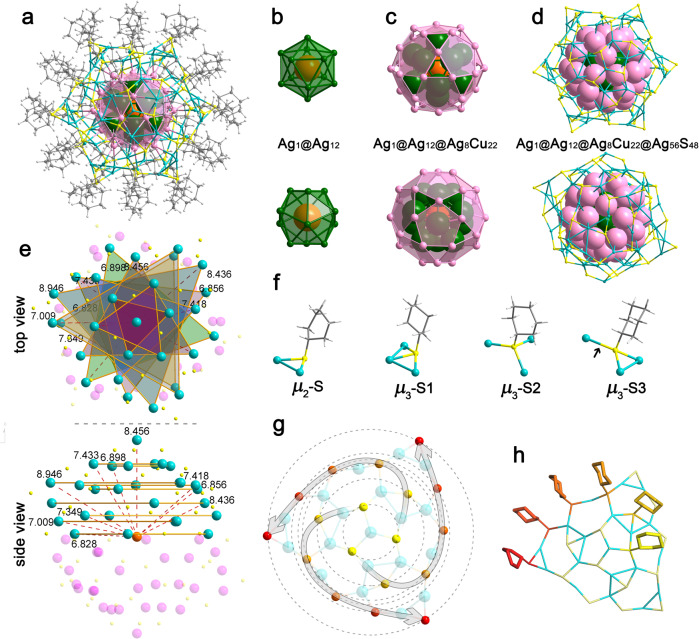

The crystal adopts a trigonal space group of P−3, and the 99 metal atoms are distributed in four shells peripherally protected by 48 CHT ligands (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Fig. 1a). Since the dissociation energy of the Cu−Cu bond is higher than that of the Ag−Ag or Ag−Cu bond, Cu atoms generally prefer to form a pure shell without enclosing Ag atoms in AgCu alloy NCs. Herein, we found that 22 copper atoms and eight silver atoms are distributed in the second outermost of the nanoparticle, probably because the quantity of Cu atoms in Ag77Cu22 is not enough to form a separate shell. The other three shells are fully occupied by silver atoms, and the nanoparticle has the structure of Ag1@Ag12@M30@Ag56(SR)48, as illustrated in Fig. 1b–e (the carbon and hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity). The central Ag atom and the second shell form a conventional 13-atom icosahedron (Fig. 1b), which is enclosed by a 30-atom icosidodecahedron. The icosidodecahedron shell can be described as 20 triangular faces and 12 pentagonal faces joined together (see Fig. 1c), and every center of the pentagonal face corresponds to each vertex of the 12-atom icosahedron (Fig. 1c). The outermost shell consists of 56 Ag atoms and 48 S atoms with three gradients viewed from the side (Supplementary Fig. 10). Gradient 1 shows a dendritic growth mode to form a cone-like shape that is composed of 19 Ag atoms and 18 S atoms (Ag19S18 for short). Gradient 3 is the inverted shape of gradient 1, which appears as a mutual mirror from the top view. Six Ag3S2 units constitute gradient 2, which sews up gradients 1 and 3. Ten sets of equivalent Ag-atom sites are found in the half shell via the measurement of the radial distances and marked by nine triangles and one Ag on the apex (Fig. 1e). The other half (purple) has the same Ag-atom sites and thus is not marked. 24 atoms in the (AgCu)30 shell are coordinated to the Ag atoms in the Ag56S48 outer shell (every Ag or Cu atom in the (AgCu)30 shell bonds 2 or 3 Ag atoms in the Ag56S48 outer shell) except for the six metal atoms closed to the six vertexes (Supplementary Fig. 11). This shell can also be described as a combination of 36 distorted cyclic staples through edge- or vertex-sharing, including one type of Ag3S3 (1 × 6) staple and five types of Ag4S4 (5 × 6) staples (see Supplementary Fig. 12). These cyclic staples, with Ag and S atoms arranged alternately, are pieced together like different patches. Ag3S3 staples are located around the vertex of the gradient 1 or 3 cone, and two types of Ag4S4 staples (b, c in Supplementary Fig. 12) surround the Ag3S3 staples in a stepwise manner to form the Ag19S18 cone. Gradient 2 consists of the other three Ag4S4 staples (d, e, f in Supplementary Fig. 12). Ag3S3 staples are planar structures, while Ag4S4 staples are all distorted with zigzag or boat shapes. Generally, the S atoms in the staples protrude from the surface of thiolated nanoparticles, and, thus, can be viewed as a protected shell. However, the S atoms in the Ag56S48 shell almost lie in the same planes as the Ag atoms. In other words, S atoms are interlaced with Ag atoms in this shell except for the six vertices S (red atoms in Supplementary Fig. 10). This can also be proven by the fact that 73% of the Ag–S–Ag angle on the Ag56S48 shell exceeds 90°, and that such a ratio is the highest among the investigated thiolated nanoparticles (nanoclusters) in the crystal phase (Supplementary Fig. 13), probably due to the strong repulsion from the especially close nanoparticles (vide infra).

Fig. 1. Crystal structure of Ag77Cu22(CHT)48.

a Top view along the C3-axis of Ag77Cu22(CHT)48. Top and side views of each shell: b Ag12 shell, c Ag8Cu22 shell, d Ag56S48 shell. e The radial distances from the center Ag atom (orange) to the Ag atoms (cyan) on the outer shell. f The interface bonding motifs for AgCHT and g, h the ripple-like pattern of S atoms in Ag19S18 units. The colors of the S atoms change from yellow to red with ripple diffusion. The distorted arrows indicate the rotation of the helical stripes. Color codes: orange, green, cyan, pale pink, purple, Ag; pale pink, Cu; gray, C; light gray, H; others, S.

Surface morphology

The surface motifs consist of 48 thiolates, including six two-coordinated and 42 three-coordinated thiolates, with an average Ag–S bond length of 2.4125 Å. μ3-S can be further categorized into three classes (μ3-S1, μ3-S2, and μ3-S3) in terms of the Ag–S–Ag angle (Fig. 1f). The thiolate ligand in the μ3-S1 type binds to the shell deviating from the Ag3 unit with small Ag–S–Ag angles, while the thiolate ligands in the μ3-S2 and μ3-S3 types bind to the Ag3 unit at relatively large angles. The difference between the μ3-S2 and μ3-S3 types is that the three Ag–S–Ag angles in μ3-S2 are all approximately equal to 110°, while one of the three angles in μ3-S3 turns to ca. 81°. It is worth noting that with the angle decreasing in μ3-S3, one Ag–S bond (indicated by a black arrow) is elongated to 2.835 Å, which is obviously longer than the common Ag–S bond (2.3–2.7 Å) (see the statistics in Supplementary Fig. 14) and rarely found in Ag nanoparticles (nanoclusters). Interestingly, a ripple-like arrangement was found for the Ag19S18 cone (gradient 1) in the outermost shell of Ag77Cu22, which has not been reported previously in silver nanoparticles (nanoclusters). Every three S atoms are assembled into a ring with one Ag atom at the center, leading to a ripple-like pattern with six rings (the six groups of S atoms are gradually marked from yellow to red, see Fig. 1g). Moreover, the S atoms, as well as the cyclohexyl tails with varying orientations (Fig. 1h), adopt a helical anticlockwise stripe pattern along the six rings. The same pattern is also observed on the opposite pole (gradient 3) but with a clockwise rotation.

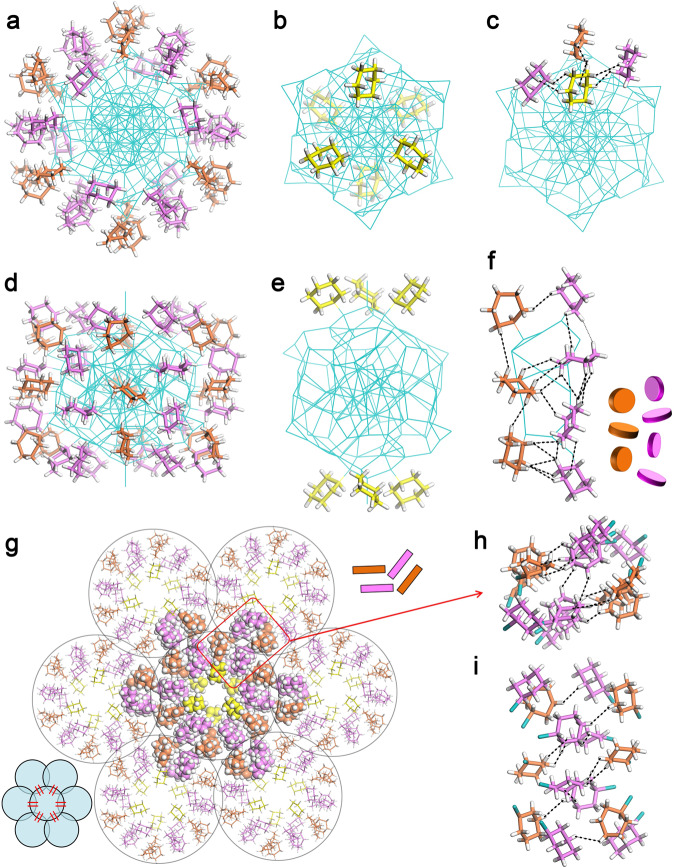

Recently, hierarchically ordered patterns formed by the self-assembly of Au–SR on the surface of NCs have attracted extensive interest in manipulating property-related complex structures43. Here, the 48 ligands can be further divided into three sorts (Fig. 2a, b): six ligands (yellow in Fig. 2b) are equally distributed into two groups on the poles with ca. 60° rotation; 24 ligands in six groups (pink in Fig. 2a) are arranged on the surface perpendicular to the waist; and the remaining 18 ligands (orange in Fig. 2a) are aligned into six parallel groups to form an alternating pattern with the abovementioned 24 ligands (like a clock dial). A complete H···H interaction network is formed inside the Ag77Cu22 nanoparticle. For example, every ligand (yellow) around the poles shows H···H interactions with three adjacent ligands (Fig. 2c), and the 12 groups of ligands across the waist also show H···H interactions in two dimensions (see Fig. 2d–f, H···H spacing in Supplementary Table 1). Notably, the H···H spacing across the waist is very short (average value of 2.714 Å), which can influence the formation of interlocked ligands via the cyclohexane orientation. When the two neighboring groups (including seven ligands) are regarded as one unit, it is found that every cluster connects with the surrounding clusters through the six abovementioned units (Fig. 2g). As shown in Fig. 2h, i and Supplementary Table 1, the H···H interactions between clusters intersect between four contacting groups of ligands, indicating dense packing among clusters.

Fig. 2. Surface pattern of the ligands on Ag77Cu22 NCs.

The ligands are distributed perpendicular to the waist (a) or on the poles (b). c Interactions between the pole ligands and their surrounding ligands. d, e side views of a and b. f Interactions between the ligands perpendicular to the waist. g Seven close-packed Ag77Cu22 NCs with interactions in six directions. h Top view and i side view of the interparticle interactions point-by-point. Color codes: orange, pink, yellow, C; white, H; cyan, S, Ag, Cu.

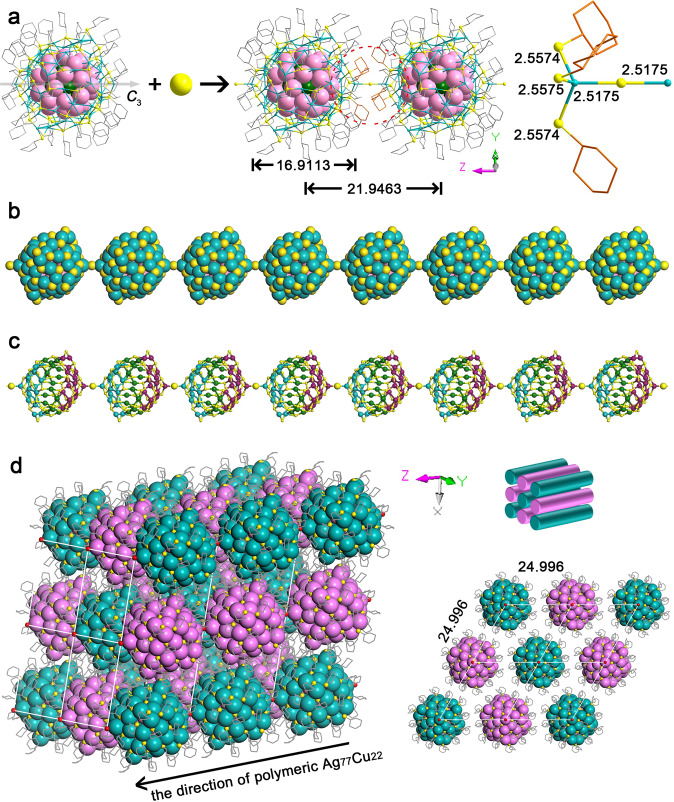

Polymeric structure

Another unusual feature of the crystal structure is the straight S-linked nanoparticle chains along the z-axis (Fig. 3) formed by connecting the pole Ag atoms with S ions. The linker “X” can be “S”, “SH”, “Cl”, or “Br” on the basis of the starting materials used in this reaction, however, both X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Supplementary Fig. 15) and energy dispersive spectrometer (EDX) (Supplementary Fig. 8) exclude the existence of Cl or Br. Ion chromatography (IC) and precipitation experiments (PEs) further exclude the existence of Cl– or Br–, and identify the “X” to be “S2–” (Supplementary Fig. 16). The strong alkaline reaction solution (NaBH4) does not prefer the forming of HS–, too. IR spectrum further excludes the existence of HS– since the feature signal of HS– at ~2550 cm–1 was not found in the IR spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 17). The bridging S2– ions are probably produced from the C–S bond cleavage of thiol or thiolate, as was studied by us44 and some other groups45–48. As shown in Fig. 3a, b, the Ag–S–Ag angle formed by the two pole silver atoms and the linker S is equal to exactly 180° and the radial direction of such chains coincides with the C3-axis of every single Ag77Cu22 NC, perpendicular to the x–y plane in the crystal packing. Therefore, the chains are perfectly straight lines without any rotation of the NCs. Note that to make room for the S linker, the three thiolates around the Ag pole stretch out compared with other ligands, forming a “hole” or an “open” Ag for the linkage (Fig. 3a). As shown in Fig. 3c, the two mirrored Ag19S18 cones on the shell marked with cyan and purple are also arranged alternately in the chains. The lengths of the Ag–S bonds for every sulfur atom linking two NCs are both equal to 2.5175 Å, which is even shorter than that of some typical Ag–S bonds (2.356–2.835 Å) in the shell. The metal core diameter of Ag77Cu22 is ca. 1.69 nm, and the interparticle distance along the chain is ca. 2.19 nm (Fig. 3a). However, the interparticle distances along the x- and y-axes are both ca. 2.5 nm (Fig. 3d), implying a stronger interaction between the neighboring nanoparticles along the chain direction, as also demonstrated by the inter-nanoparticle H···H interactions. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 18, the close inter-nanoparticle H···H spacings, such as 2.288, 2.561, and 2.642 Å, are observed along the chain direction, while the shortest inter-nanoparticle H···H spacing along the perpendicular direction (x- and y-axes) is 2.422 Å (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 3. Polymeric structure of Ag77Cu22 NCs.

a The linkage of Ag77Cu22 NCs (H atoms are omitted for clarity). b Space-filling view of the Ag77Cu22 chain (C and H atoms are omitted for clarity). c The arrangement of Ag56S48 shells along the Ag77Cu22 chain (C and H atoms are omitted for clarity). d 3D framework of Ag77Cu22 nanowires and view of the superlattice from the z-axis (note that the two-color scheme in Fig. 3d does not indicate the chirality, but means different chains in the crystal packing). H atoms are omitted for clarity. The length unit is Å. Color codes: cyan, green, pink, purple, Ag; pale pink, Cu; yellow, red, S; gray, orange, C.

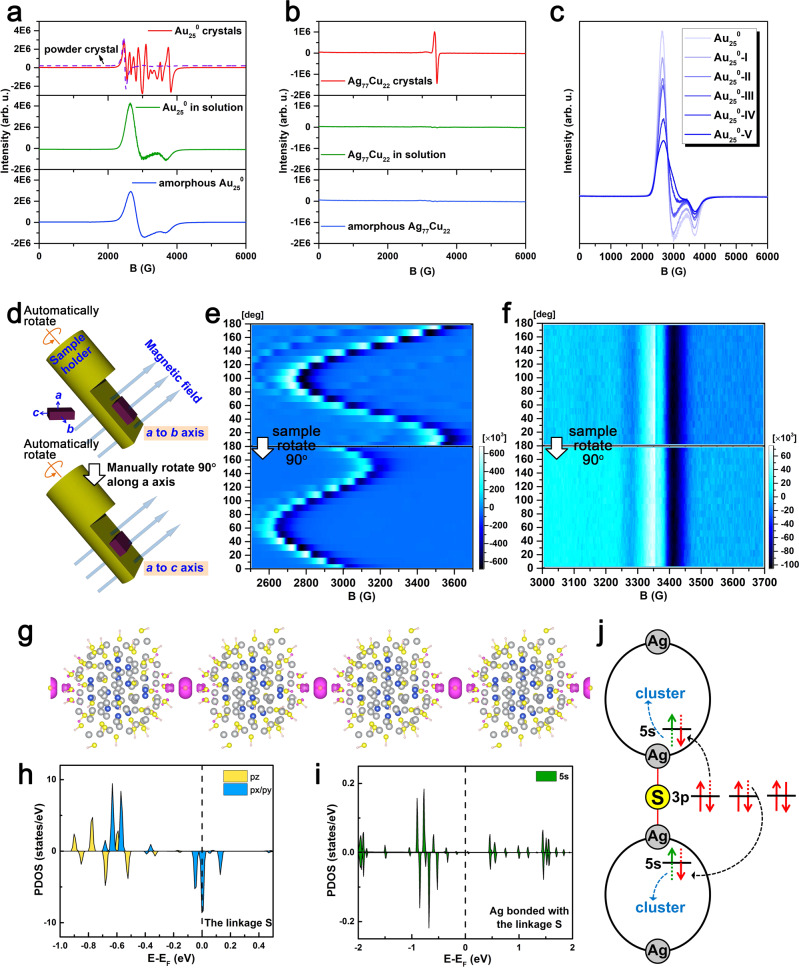

Magnetism performance

The nominal shell-closing electron count (n*) for the Ag77Cu22 nanoparticle is 49 (n* = NvA − M − z = 77 × 1 + 22 × 1 – 48 − 2 = 49)49, reminding one of its paramagnetism50, which was confirmed by experiments. For comparison, the paramagnetism of neutral Au25 was also investigated. As shown in Fig. 4a, the EPR spectrum for a small amount of neutral Au25 single crystals shows multiple peaks (red curve). When the large crystals are broken into microcrystals by ultrasonication, the refined peaks disappear, and broadband (identical to the reported spectrum51,52) appears, indicating the influence of the crystal orientation and the magnetic anisotropy of the Au25 crystal. The EPR measurement was conducted by automatically or manually rotating the single crystal sample (illustrated in Fig. 4d) to further probe the magnetic anisotropy. As shown in Fig. 4e, the intensity and position of the EPR signals for the Au25 single crystal change stepwise as the sample is rotated, further confirming the magnetic anisotropy of neutral Au25 crystals. In contrast, the Ag77Cu22 nanoparticle assembly shows a different EPR spectrum from that of a single Au250 crystal (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 19), indicating different origins for the magnetism. The blank experiments exclude the external introduction of magnetic impurities, see Supplementary Fig. 20. The simulated results (g = 2.0072, 1.9671, and 1.9659) are well consistent with the experimental observations (Supplementary Fig. 21). Particularly and interestingly, the EPR spectra remain the same after rotating the single crystal sample (Fig. 4f), indicating magnetic isotropy. Such magnetic isotropy is unusual and has rarely been reported in metal nanoparticles53,54, which inspires our enthusiasm for further investigation. Due to the difficulty of experimentally mapping the magnetism resource, DFT calculations were performed to acquire the spin distribution using the crystal structure with simplified ligands to reduce the computational cost55. The crystal structure is preserved (other than replacing R=cyclohexyl groups by R=H-atoms), and the collinearity of C3, the linker, and the z-axis is preserved when relaxed, see Supplementary Fig. 22. The spin density distribution is shown in Fig. 4g. Remarkably, the magnetic moment is found to be mainly localized at the S2– linker rather than the metal atoms (Ag or Cu). Only weak spin density is revealed on the surface or kernel atoms adjacent to S2–, and the magnetic moment of the linker S2– is almost 12 times larger than that of the Ag atom with the largest magnetic moment. The detailed spin distribution is given in Supplementary Table 2. In strong contrast, the magnetic moment of Au25 is found to be mainly localized at the kernel Au atom (see Supplementary Fig. 23 and Supplementary Table 3), similar to the results reported by ref. 50. It is generally believed that magnetic anisotropy has diverse origins53,56, such as spin–orbit coupling (SOC), exchange interaction, etc. For Au25, the magnetic anisotropy can be attributed to the strong SOC of Au atoms since the noncollinear calculation reveals large magnetic anisotropy energy (MAE, ca. 200 μeV). The torque method was further applied for analysis57, and it was revealed that the positive uu (27.78 meV) and dd (27.96 meV) channels contribute more (97 μeV) than the negative ud + du (–55.65 meV) channel, leading to a positive MAE, which provides further support for the SOC mechanism for the magnetic anisotropy. For the Ag77Cu22 assembly, given the consideration of the major spin on S2–, the SOC mechanism is not applicable since the SOC parameter for S (288 cm–1) with a relatively small atomic number is much lower than that for Cu (1150 cm–1) or Ag (3540 cm–1)58, and, thus, the SOC effect is negligible; the exchange interaction can also be excluded given the large distances between S spins (2.2 nm along the chain direction; 2.5 nm perpendicular to the chain direction); magnetic measurements using a Quantum Design MPMS3 SQUID magnetometer were used to also exclude the magnetic interaction since the Curie-Weiss temperature obtained by fitting variable temperature magnetic susceptibility was close to 0 (see Supplementary Fig. 24), implying an absence of spin interaction. The temperature-dependent EPR further confirms the noninteraction of the spins, see Supplementary Fig. 25. The magnetic isotropy of the assembly can be ascribed to the major spin on sulfur confined in such a special structure. Note that the g-factor and specific magnetization (emu/g) are shown in Supplementary Figs. 21 and 24, respectively. The g-value (1.9790) was close to 2.0023 (g-value of a free electron) and the obtained effective moment μeff = 1.62 μB is also consistent with S = ½ per cluster molecule (1.73 μB), supporting the notion that the magnetism of Ag77Cu22 assembly originates from the unpaired shell electron of the Ag77Cu22 nanoparticle. Notably, the hyperfine splitting (fine structure) was not observed in the EPR spectra, which might be interpreted by the delocalization33,50,59,60 of the unpaired spin or the weak spin–nuclei interaction due to the extremely low abundance of magnetic 33S nuclei61,62. A natural question arises: why the magnetic moment mainly locates at S2–. It is possible that electron transfer occurs from linker S2– to the metal atom. Such electron transfer between sulfur and the nanoparticle core was revealed in our previous photoluminescence study63. The close linker (Ag–S distance) also provides support for such a phenomenon. A study of the projected density of states (PDOS) revealed that the linker S shows a magnetic moment of ~1 μB with half-occupied spin-down states of px/py orbitals, while the connected Ag exhibits a very small moment with partially occupied spin-up and spin-down states of 5s orbitals (see Fig. 4h, i), providing further support for the above proposal. Considering the bonding of every S2– linker with two nanoparticles, we suggest that the electron transfer for S2– is divided between the two connected silver atoms (Fig. 4j), forming one unpaired spin, and the electron on Ag can further transfer to the neighboring atoms, resulting in a distribution of the magnetic moment for the nanoparticle (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Table 2). The g = 1.9790 determined from the EPR spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 21) reminds one of the existence of sulfur radicals64. To further verify the electron transfer from sulfur to the connected silver (i.e., formation of the sulfur radical), DMPO was used to capture the radical. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 26 and 27, strong radical signals were observed for the case of Ag77Cu22 assembly, but no significant signals were detected for the case of Au25, confirming the presence of sulfur radicals in the Ag77Cu22 assembly and the absence of sulfur radicals in Au25, since that the sulfur radicals can be captured by DMPO and lead to the emergence of the EPR signal of the trap adducts as well as the decrease of the paramagnetism signal.

Fig. 4. Magnetic performance of Ag77Cu22 and Au250.

EPR spectra for a Au250 and b Ag77Cu22 in different states (note: the solution samples were aged for 1 h before measurements, and the amorphous samples were prepared from the above-aged solutions by fast precipitation and drying). c EPR spectra measured for Au250 NCs with different CHT substitution numbers. d Schematic depiction of the rotational EPR experiment. 2D EPR density plots of e Au250 and f Ag77Cu22. g Spin distribution of polymeric Ag77Cu22 (magenta: spin density). Spin-polarized PDOS of the h 3p orbitals of the S linkage and i 5 s orbitals of Ag bonded with the S linkage. j Schematic representation of the electronic structures of the linkage.

Although the monosulfur radical signal was once detected under some specific conditions, the precise structure involving monosulfur radicals was undocumented64–66. Herein, the active sulfur radical might be stabilized by the assembly structure, which was confirmed by subsequent experimental results. When the assembled crystals are dissolved in dichloromethane, the EPR intensity decreases with increasing time (see the time evolution of the integrated EPR intensity in Supplementary Fig. 28 and the green line in Fig. 4b), and the EPR signal remains weak in the amorphous state after the solvent is removed (see blue line in Fig. 4b). In contrast, the EPR intensity for neutral Au25 crystals is not quite influenced by dissolution (green line in Fig. 4a). Taken together, these facts demonstrate that the sulfur radical is stabilized by the specific assembly structure, which has important implications for novel functional development based on the assembly of atomically precise nanoparticles. It is concluded that chain structure disassembly can lead to electron return and the recovery of S2–, which was verified by ion chromatography: no other sulfur ion species except for S2– is detected in the extract of the disassembly solution (Supplementary Fig. 16b). After the electron returns to sulfur, the Ag77Cu22 nanoparticle is expected to bear an unpaired shell-closing electron, and thus, exhibits paramagnetism in solution (Supplementary Fig. 29). However, unlike the neutral Au25 nanocluster, Ag77Cu22 shows a decreasing EPR intensity with increasing time in the solution, as mentioned above. A plausible reason for this is the spin pairing of Ag77Cu22 nanoparticles due to the short and flexible ligands that enable the nanoparticles to approach each other. However, the Au25 nanoclusters cannot couple in solution due to the interference of the relatively long and rigid ligands, which is verified by TEM images since nanoparticle pairs are found for Ag77Cu22 but not for 2-phenylethanethiolated Au25, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 30, 31a. Previous work also provides support: polymeric Au25 capped by n-butanethiolates was proven to be antiferromagnetic due to spin coupling along the polymer chain33. Au25 clusters along the chain (z-direction) are connected directly via Au−Au interactions, and the interparticle distance is 1.3001 nm, which is significantly shorter than that in the x- and y-directions (1.6131 nm and 1.7982 nm, respectively). To further probe the influence of the ligand on nanoparticle coupling, we conducted an EPR test for neutral Au25 protected by a stiffer ligand (naphthalenethiolate, Nap) or a more flexible ligand (CHT) than 2-phenylethanethiolate (PET). Note that the 2-phenylethanethiolates on the Au25 nanocluster are fully exchanged by naphthalenethiolates but not by cyclohexanethiolates, as identified by SCXC or mass spectra (Supplementary Figs. 32 and 33), and five samples with varying content of cyclohexanethiolates were prepared. All five samples share UV−Vis spectra that are similar to that of Au25(PET)180 (Supplementary Fig. 34), implying structural similarity with Au25(PET)180. The substitution numbers (Xs) were estimated from ESI-MS as follows: Au25-I, x = 2–4; Au25-II, x = 3–6; Au25-III, x = 5–9; Au25-IV, x = 11–15; Au25-V, x = 13–17 (Supplementary Fig. 33). The experimental results reveal that naphthalenethiolated Au25 shows similar EPR signals in both solution and crystals without the time-dependent intensity observed in solution (Supplementary Fig. 35), while cyclohexanethiolated Au25 exhibits cyclohexanethiolate content and a time-dependent EPR intensity in solution (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 36). Furthermore, the decrease in the EPR intensity corresponds to the nanoparticle pairing degree observed in TEM images (that is, the larger the decrease in the EPR intensity, the denser nanoparticle pairing, see Supplementary Fig. 31). Similarly, Maran et al. previously revealed that the EPR intensity of ethanethiolated Au25 is influenced more by its state (crystal or solution) than n-butanethiolated Au2533. Taken together, these facts demonstrate that the inter-nanoparticle distance (M: metal atom) is critical for spin coupling (i.e., spin coupling only occurs when the inter-nanoparticle distance is short enough). It is worth noting that such spin coupling does not result in the growth of nanoparticles since no large nanoparticles (or dimers) were detected by ESI-MS, UV-Vis spectrometry, and TEM (see Supplementary Figs. 37 and 38).

Discussion

In summary, we introduced an on-site synthesis-and-assembly strategy to solve the challenge of assembling atomically precise metal nanoparticles. A straight-chain structure composed of [Ag77Cu22(CHT)48]2+ nanoparticles and linker S2– was obtained, and it was precisely characterized by using ESI-MS and SCXC. Interestingly, a rare Ag/Cu alloy shell was observed in the nanoparticles, and cyclic staples and a ripple-like thiolate distribution on the nanoparticles were, to the best of our knowledge, also reported for the first time. In particular, both calculations and experiments such as EPR and DMPO probing were used to reveal that the linker is sulfur radical with magnetic isotropy, which is formed by 2p electron transfer from S2– to the connected silver atoms and stabilized by the chain structure. The disassembly of the straight-chain structure in solution leads to the return of the electron to S2– and restoration of the paramagnetism of the Ag77Cu22 nanoparticles. However, the EPR intensity for Ag77Cu22 decreases with increasing time, which is ascribed to the spin coupling of Ag77Cu22 nanoparticles in solution. Further experiments reveal that the inter-nanoparticle distance is critical to the nanoparticle (nanocluster) spin coupling (i.e., coupling only occurs when the inter-M-M distance is short enough). Such an assembly-induced spin transfer and inter-nanoparticle distance-dependent spin coupling are not only interesting and surprising but also have important implications for the novel functional development of nanoparticles and the understanding of the shell-closing electron behavior of superatoms. It is expected that our work will extend a promising but still challenging field−the assembly of metal nanoparticles with atomic precision.

Methods

Chemicals

All chemicals were commercially available and used as received. Silver nitrate (AgNO3, 99.99%), cuprous chloride (CuCl, 95%), cyclohexanethiol (CHT, 98%), tetraphenylphosphonium bromide (TPPB, 98%), naphthalenethiol (Nap, 99%), 2-phenylethanethiol (97%), and sodium borohydride (NaBH4, 98.0%) were purchased from Aladdin. 5, 5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) was obtained from Dojindo. Triethylamine (99%), ethanol (AR), dichloromethane (AR), hexane (AR), Toluene (AR), and ethanol (AR) were purchased from Sinopharm chemical reagent co., ltd.

Synthesis of AgCu nanoclusters

AgCHT complexes were prepared by mixing 120 mg of AgNO3 and 200 μl of CHT in MeOH. Then, 22 mg of the washed AgCHT complexes and 10 mg of CuCl were dissolved in 40 ml of CH2Cl2 in a 100 ml of single-neck round-bottom flask under vigorous stirring. Then, 20 μl of triethylamine was immediately added to the reaction solution. After that, 4 ml of an ethanol solution of NaBH4 (38 mg) and TPPB (42 mg) was added dropwise to the mixture, which showed a color change from yellow to dark brown. The reaction was then kept under continuous stirring for 6 h under ice-cold conditions in the absence of light. The mixture was rotary evaporated to dryness to give a dark solid, which was washed with methanol three times. The as-obtained precipitate was extracted using 15 ml of CH2Cl2, and the supernatant was aged for over a week at room temperature to form a green solution. Finally, a concentrated green solution (0.5 ml) was placed into a clean NMR tube layered with ca. 2 ml of hexane. Then, the tube was carefully capped and stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C. Black crystals were obtained after approximately 1 month.

Ligand exchange of Au25(PET)18

Neutral Au25 NCs were first prepared according to the previous literature:67,68 10 mg Au25 anions were dissolved in 8 ml CH2Cl2 and treated with 200 μl H2O2 (30%) for 20 min at room temperature, then the organic solution was extracted and purified using preparative thin-layer chromatography to obtain Au250 NCs. Six milligrams of neutral Au25 was dissolved in 300 μl of toluene and then reacted with different amounts of CHT at room temperature for 30 min or 60 min. The products were precipitated and washed with methanol. Au25(Nap)18 was synthesized at 70° by mixing neutral Au25 with excess Nap. The final product was purified using preparative thin-layer chromatography69–71.

Characterization

Optical absorption spectra were acquired in the wavelength range of 190–900 nm using a Shimadzu UV-2600 spectrophotometer. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) was performed on a Waters Q-TOF mass spectrometer equipped with a Z-spray source. Single crystal X-ray diffraction data were collected on a Bruker D8 Venture X-ray diffractometer (Bruker, Germany). The possible reasons for the high residual density are the inadequate absorption correction of silver which strongly absorbs X-rays or the uncertainty of the metal atoms (Ag or Cu), resulting in unreal residual Q peaks. The low C-C bond precision originates from the restraints on the hexyl ligands (S2 and S5) due to their varied configuration and weak diffraction intensity. X-band CW-EPR spectra were collected using a Bruker EMX plus 10/12 X-band EPR spectrometer equipped with an ER4119HS (TE011) high-Q cavity. Cryogenic temperatures were achieved using an Oxford Instruments ESR910 liquid helium flow cryostat and an Oxford Instruments ITC503 temperature controller. A programmable one-axis goniometer was used for the sample rotation. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were recorded using a Tecnai G2 TF20 instrument (FEI Co., USA). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS) was performed on an Autoflex Speed TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker) in positive ionization mode. Magnetization measurements were carried out for the NCs (sealed into nonmagnetic capsules) as a function of temperature and field by using a SQUID magnetometer (Quantum Design MPMS3).

Theoretical methods

Ab initio calculations were performed based on spin-polarized density functional theory (DFT), as implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)72. The ion-electron interaction was described by the projector augmented wave (PAW) approach73,74. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) in the scheme of the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) functional was used to describe the exchange-correlation interaction75,76. The force and energy convergence criteria used for the electronic structure calculations were less than 0.02 eV/Å and 10–5 eV, respectively. Given the consideration of the strong correlation effect on the d orbitals of Au, Ag, and Cu, GGA + U calculations with effective U values of 1.5 eV (Au) and 1 eV (Ag and Cu) were performed by including a Hubbard U term77,78. The spin moment and MAE were calculated by taking into consideration of spin-orbital coupling and magnetic noncollinearity79. EPR simulations were carried out by assuming a distribution of randomly oriented S = 1/2 spin centers with a Lorentzian lineshape using the EasySpin toolbox working on the MatLab software platform.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21925303, 21771186, 21829501, 21222301, 21528303, and 21171170 to Z.W., No. 91961204 to J. Zhao, and Nos. 21701179, 22171268 to N.X.), Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Nos. 1708085QB36, 2108085MB56 to N.X.), the Special Foundation of President of HFIPS (No. YZJJ202102 to N.X.), CASHIPS Director’s Fund (No. BJPY2019A02 to Z.W.), Key Program of 13th five-year plan, CASHIPS (No. KP-2017-16 to Z.W.), Collaborative Innovation Program of Hefei Science Center, CAS (No. 2020HSC-CIP005 to Z.W.), and CAS/SAFEA International Partnership Program for Creative Research Teams(to Z.W.). We thank Prof. Wei Tong and Dr. Jingxin Li for their help with EPR measurements and discussions. EPR was performed on the Steady High Magnetic Field Facilities, High Magnetic Field Laboratory, CAS.

Author contributions

Z.W. conceived the project and analyzed the data. J. Zhao. and Z.Z. co-supervised the project and discussed the structure-magnetism correlation. N.X. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. J.X. carried out the DFT calculations. D.P. carried out the magnetism experiments. S.J., J. Zha, and N.Y. performed the TEM and SEM measurements and analyzed the crystal structure. Y.S. and X.J. contributed to discussions on the calculation results.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Robert Whetten and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this work have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC) under deposition numbers 2207144 for the polymeric Ag77Cu22 nanoclusters, respectively. These data can be obtained free of charge from the CCDC via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. Checkcif file for Ag77Cu22 CIF file is given as Supplementary Dataset. All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Data were available from the first author and the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Nan Xia, Jianpei Xing, Di Peng.

Contributor Information

Zhi Zeng, Email: zzeng@theory.issp.ac.cn.

Jijun Zhao, Email: zhaojj@dlut.edu.cn.

Zhikun Wu, Email: zkwu@issp.ac.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-022-33651-9.

References

- 1.Burda C, Chen X, Narayanan R, El-Sayed MA. Chemistry and properties of nanocrystals of different shapes. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:1025–1102. doi: 10.1021/cr030063a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang H, et al. Stabilization of silver and gold nanoparticles: preservation and improvement of plasmonic functionalities. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:664–699. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeng H, et al. Exchange-coupled nanocomposite magnets by nanoparticle self-assembly. Nature. 2002;420:395–398. doi: 10.1038/nature01208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeVries GA, et al. Divalent metal nanoparticles. Science. 2007;315:358–361. doi: 10.1126/science.1133162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan JA, et al. Self-Assembled plasmonic nanoparticle clusters. Science. 2010;328:1135–1138. doi: 10.1126/science.1187949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xia Y, et al. Self-assembly of self-limiting monodisperse supraparticles from polydisperse nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011;6:580–587. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2011.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuzyk A, et al. DNA-based self-assembly of chiral plasmonic nanostructures with tailored optical response. Nature. 2012;483:311–314. doi: 10.1038/nature10889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan C, Wang T. A new view for nanoparticle assemblies: from crystalline to binary cooperative complementarity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017;46:1483–1509. doi: 10.1039/C6CS00696E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X, Liu X, Liu X. Self-assembly of colloidal inorganic nanocrystals: nanoscale forces, emergent properties and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021;50:2074–2101. doi: 10.1039/D0CS00436G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lv J, et al. Self-assembled inorganic chiral superstructures. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2022;6:125–145. doi: 10.1038/s41570-021-00350-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Z, Fan Q, Yin Y. Colloidal self-assembly approaches to smart nanostructured materials. Chem. Rev. 2022;122:4976–5067. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang M, et al. Self-assembly of nanoparticles into biomimetic capsid-like nanoshells. Nat. Chem. 2017;9:287–294. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bian T, et al. Electrostatic co-assembly of nanoparticles with oppositely charged small molecules into static and dynamic superstructures. Nat. Chem. 2021;13:940–949. doi: 10.1038/s41557-021-00752-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniel M-C, Astruc D. Gold nanoparticles: assembly, supramolecular chemistry, quantum-size-related properties, and applications toward biology, catalysis, and nanotechnology. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:293–346. doi: 10.1021/cr030698+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nie Z, Petukhova A, Kumacheva E. Properties and emerging applications of self-assembled structures made from inorganic nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010;5:15–25. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grzelczak M, Vermant J, Furst EM, Liz-Marzán LM. Directed self-assembly of nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2010;4:3591–3605. doi: 10.1021/nn100869j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Brien MN, Jones MR, Mirkin CA. The nature and implications of uniformity in the hierarchical organization of nanomaterials. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:11717–11725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605289113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Billinge SJL, Levin I. The problem with determining atomic structure at the nanoscale. Science. 2007;316:561–565. doi: 10.1126/science.1135080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boles MA, Engel M, Talapin DV. Self-assembly of colloidal nanocrystals: from intricate structures to functional materials. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:11220–11289. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gong J, Li G, Tang Z. Self-assembly of noble metal nanocrystals: fabrication, optical property, and application. Nano Today. 2012;7:564–585. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2012.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia N, Wu Z. Controlling ultrasmall gold nanoparticles with atomic precision. Chem. Sci. 2021;12:2368–2380. doi: 10.1039/D0SC05363E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Claridge SA, et al. Cluster-assembled materials. ACS Nano. 2009;3:244–255. doi: 10.1021/nn800820e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Z, Yao Q, Zang S, Xie J. Directed self-assembly of ultrasmall metal nanoclusters. ACS Mater. Lett. 2019;1:237–248. doi: 10.1021/acsmaterialslett.9b00136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kang X, Zhu M. Intra-cluster growth meets inter-cluster assembly: the molecular and supramolecular chemistry of atomically precise nanoclusters. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019;394:1–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2019.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ebina A, et al. One-, two-, and three-dimensional self-assembly of atomically precise metal nanoclusters. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:1105. doi: 10.3390/nano10061105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, et al. Double-helical assembly of heterodimeric nanoclusters into supercrystals. Nature. 2021;594:380–384. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03564-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoon B, et al. Hydrogen-bonded structure and mechanical chiral response of a silver nanoparticle superlattice. Nat. Mater. 2014;13:807–811. doi: 10.1038/nmat3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nonappa, et al. Template-free supracolloidal self-assembly of atomically precise gold nanoclusters: from 2D colloidal crystals to spherical capsids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:16035–16038. doi: 10.1002/anie.201609036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang R-W, et al. Hypersensitive dual-function luminescence switching of a silver-chalcogenolate cluster-based metal–organic framework. Nat. Chem. 2017;9:689–697. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chakraborty A, et al. Atomically precise nanocluster assemblies encapsulating plasmonic gold nanorods. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:6522–6526. doi: 10.1002/anie.201802420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Z, et al. Aurophilic interactions in the self-assembly of gold nanoclusters into nanoribbons with enhanced luminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:8139–8144. doi: 10.1002/anie.201903584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen, S. et al.Assembly of the thiolated [Au1Ag22(S-Adm)12]3+ superatom complex into a framework material through direct linkage by SbF6− anions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 7542–7547 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.De Nardi M, et al. Gold Nanowired: a linear (Au25)n polymer from Au25 molecular clusters. ACS Nano. 2014;8:8505–8512. doi: 10.1021/nn5031143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Z-Y, et al. Atomically precise site-specific tailoring and directional assembly of superatomic silver nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:1069–1076. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b11338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Q, et al. Modulating the hierarchical fibrous assembly of Au nanoparticles with atomic precision. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:3871. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06395-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hossain S, et al. Understanding and designing one-dimensional assemblies of ligand-protected metal nanoclusters. Mater. Horiz. 2020;7:796–803. doi: 10.1039/C9MH01691K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wen Z-R, et al. [Au7Ag9(dppf)3(CF3CO2)7BF4]n: a linear nanocluster polymer from molecular Au7Ag8 clusters covalently linked by silver atoms. Chem. Commun. 2019;55:12992–12995. doi: 10.1039/C9CC05924E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan P, et al. Solvent-mediated assembly of atom-precise gold–silver nanoclusters to semiconducting one-dimensional materials. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2229. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16062-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laibinis PE, et al. Comparison of the structures and wetting properties of self-assembled monolayers of n-alkanethiols on the coinage metal surfaces, copper, silver, and gold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:7152–7167. doi: 10.1021/ja00019a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sellers H, Ulman A, Shnidman Y, Eilers JE. Structure and binding of alkanethiolates on gold and silver surfaces: implications for self-assembled monolayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:9389–9401. doi: 10.1021/ja00074a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gan Z, et al. The fourth crystallographic closest packing unveiled in the gold nanocluster crystal. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:14739. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu Z, et al. Kinetic control and thermodynamic selection in the synthesis of atomically precise gold nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:9670–9673. doi: 10.1021/ja2028102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeng C, et al. Emergence of hierarchical structural complexities in nanoparticles and their assembly. Science. 2016;354:1580–1584. doi: 10.1126/science.aak9750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gan Z, et al. Surface single-atom tailoring of a gold nanoparticle. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018;9:204–208. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b02982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Su, W. et al. A cleavage of the S–C bond in 2-aminothiophenal: Synthesis and crystal structure of [Ag11(μ5-S) (μ4-S2CNEt2)6 (μ3-S2CNEt2)3]. Polyhedron15, 4047–4051 (1996).

- 46.Fenske D, Persau C, Dehnen S, Anson CE. Syntheses and crystal structures of the Ag–S cluster compounds [Ag70S20(SPh)28(dppm)10](CF3CO2)2 and [Ag262S100(StBu)62(dppb)6] Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:305–309. doi: 10.1002/anie.200352351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li G, Lei Z, Wang Q-M. Luminescent molecular Ag−S nanocluster [Ag62S13(SBut)32](BF4)4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:17678–17679. doi: 10.1021/ja108684m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu J-W, et al. Anisotropic assembly of Ag52 and Ag76 nanoclusters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:1600–1603. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b12777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walter M, et al. A unified view of ligand-protected gold clusters as superatom complexes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:9157–9162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801001105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu M, et al. Reversible switching of magnetism in thiolate-protected Au25 superatoms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:2490–2492. doi: 10.1021/ja809157f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Antonello S, et al. Interplay of charge state, lability, and magnetism in the molecule-like Au25(SR)18 cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:15585–15594. doi: 10.1021/ja407887d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agrachev M, et al. Magnetic ordering in gold nanoclusters. ACS Omega. 2017;2:2607–2617. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.7b00472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lisjak D, Mertelj A. Anisotropic magnetic nanoparticles: a review of their properties, syntheses and potential applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018;95:286–328. doi: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2018.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Karotsis G, et al. [MnIII4LnIII4] Calix[4]arene clusters as enhanced magnetic coolers and molecular magnets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12983–12990. doi: 10.1021/ja104848m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Garzón IL, et al. Chirality in bare and passivated gold nanoclusters. Phys. Rev. B. 2002;66:073403. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.66.073403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernando, G. W. In Handbook of Metal Physics (ed. Fernando, G. W.) Vol. 4, 89–110 (Elsevier, 2008).

- 57.Hu J, Wu R. Control of the magnetism and magnetic anisotropy of a single-molecule magnet with an electric field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013;110:097202. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.097202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin WC. Table of spin-orbit energies for p-electrons in neutral atomic (core) np configurations. J. Res. Natl Bur. Stand. A Phys. Chem. 1971;75A:109–111. doi: 10.6028/jres.075A.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zeng C, et al. Controlling magnetism of Au133(TBBT)52 nanoclusters at single electron level and implication for nonmetal to metal transition. Chem. Sci. 2019;10:9684–9691. doi: 10.1039/C9SC02736J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ma X, et al. Rhombicuboctahedral Ag100: four-layered octahedral silver nanocluster adopting the Russian Nesting Doll Model. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:17234–17238. doi: 10.1002/anie.202006447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klein EL, Astashkin AV, Raitsimring AM, Enemark JH. Applications of pulsed EPR spectroscopy to structural studies of sulfite oxidizing enzymes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013;257:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramirez Cohen M, et al. Thiolate spin population of type I copper in azurin derived from 33S hyperfine coupling. Inorg. Chem. 2017;56:6163–6174. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b00167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu Z, Jin R. On the ligand’s role in the fluorescence of gold nanoclusters. Nano Lett. 2010;10:2568–2573. doi: 10.1021/nl101225f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu J, et al. Reactions of HS•– and S•– with molecular oxygen, H2S, HS–, and S2–: formation of SO2•–, HSSH•–, HSS•2– and HSS•. J. Phys. Chem. 1991;95:3676–3681. doi: 10.1021/j100162a044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vannotti LE, Morton JR. Paramagnetic-resonance spectra of S– trapped in alkali halide crystals. Phys. Rev. 1968;174:448–453. doi: 10.1103/PhysRev.174.448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steudel R, Chivers T. The role of polysulfide dianions and radical anions in the chemical, physical and biological sciences, including sulfur-based batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019;48:3279–3319. doi: 10.1039/C8CS00826D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhu M, Eckenhoff WT, Pintauer T, Jin R. Conversion of anionic [Au25(SCH2CH2Ph)18]− cluster to charge neutral cluster via air oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2008;112:14221–14224. doi: 10.1021/jp805786p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu Z, Suhan J, Jin R. One-pot synthesis of atomically monodisperse, thiol-functionalized Au25 nanoclusters. J. Mater. Chem. 2009;19:622–626. doi: 10.1039/B815983A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tian S, et al. Structural isomserism in gold nanoparticles revealed by X-ray crystallography. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8667. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tian S, et al. Ion-precursor and ion-dose dependent anti-galvanic reduction. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:11773–11776. doi: 10.1039/C5CC03267A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liao L, et al. Quantitatively monitoring the size-focusing of Au nanoclusters and revealing what promotes the size transformation from Au44(TBBT)28 to Au36(TBBT)24. Anal. Chem. 2016;88:11297–11301. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kresse G, Furthmüller J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B. 1996;54:11169–11186. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.54.11169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Blöchl PE. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 1994;50:17953–17979. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.50.17953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kresse G, Joubert D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 1999;59:1758–1775. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.59.1758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Perdew JP, Burke K, Ernzerhof M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996;77:3865–3868. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Perdew JP, Wang Y. Accurate and simple analytic representation of the electron-gas correlation energy. Phys. Rev. B. 1992;45:13244–13249. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.45.13244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang M, Guo H-m, Lv J, Wu H-s. Electronic and magnetic properties of 5d transition metal substitution doping monolayer antimonene: within GGA and GGA + U framework. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020;508:145197. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.145197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Volnianska O, et al. Theory of doping properties of Ag acceptors in ZnO. Phys. Rev. B. 2009;80:245212. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.80.245212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hobbs D, Kresse G, Hafner J. Fully unconstrained noncollinear magnetism within the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B. 2000;62:11556–11570. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.62.11556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this work have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC) under deposition numbers 2207144 for the polymeric Ag77Cu22 nanoclusters, respectively. These data can be obtained free of charge from the CCDC via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. Checkcif file for Ag77Cu22 CIF file is given as Supplementary Dataset. All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Data were available from the first author and the corresponding author upon request.