Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 utilizes agmatine as the sole carbon and nitrogen source via two reactions catalyzed successively by agmatine deiminase (encoded by aguA; also called agmatine iminohydrolase) and N-carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase (encoded by aguB). The aguBA and adjacent aguR genes were cloned and characterized. The predicted AguB protein (Mr 32,759; 292 amino acids) displayed sequence similarity (≤60% identity) to enzymes of the β-alanine synthase/nitrilase family. While the deduced AguA protein (Mr 41,190; 368 amino acids) showed no significant similarity to any protein of known function, assignment of agmatine deiminase to AguA in this report discovered a new family of carbon-nitrogen hydrolases widely distributed in organisms ranging from bacteria to Arabidopsis. The aguR gene encoded a putative regulatory protein (Mr 24,424; 221 amino acids) of the TetR protein family. Measurements of agmatine deiminase and N-carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase activities indicated the induction effect of agmatine and N-carbamoylputrescine on expression of the aguBA operon. The presence of an inducible promoter for the aguBA operon in the aguR-aguB intergenic region was demonstrated by lacZ fusion experiments, and the transcription start of this promoter was localized 99 bp upstream from the initiation codon of aguB by S1 nuclease mapping. Experiments with knockout mutants of aguR established that expression of the aguBA operon became constitutive in the aguR background. Interaction of AguR overproduced in Escherichia coli with the aguBA regulatory region was demonstrated by gel retardation assays, supporting the hypothesis that AguR serves as the negative regulator of the aguBA operon, and binding of agmatine and N-carbamoylputrescine to AguR would antagonize its repressor function.

A broad range of microorganisms can utilize arginine very efficiently as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen (7). Arginine also serves as the precursor for polyamines (putrescine, spermidine, and spermine), a group of ubiquitous polycations necessary for cell growth (11, 41). Arginine catabolism in pseudomonads is of particular interest because of the presence of four different pathways (14). In Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the arginine succinyltransferase pathway (19, 20, 33) and the arginine deiminase pathway (1, 9, 23, 26) serve as the major routes of arginine catabolism under aerobic and anaerobic conditions, respectively. While the arginine oxidase pathway in Pseudomonas putida also contributes significantly to arginine catabolism under aerobic growth conditions (14, 38), the absence of l-arginine oxidase activity and the presence of d-arginine hydrolase activity in P. aeruginosa suggest a potential catabolic role of this pathway for d-arginine but not l-arginine via 2-ketoarginine and 4-guanidinobutyrate in this organism (14, 38, 42).

The role of the fourth pathway, the arginine decarboxylase (ADC) pathway, in arginine utilization in pseudomonads remains unclear. In P. aeruginosa, the ADC pathway is initiated by arginine decarboxylase, which is inducible by exogenous arginine (25). Agmatine, the resulting product of arginine decarboxylation, is subsequently converted into putrescine, 4-aminobutyrate, and then succinate to channel into the tricarboxylic acid cycle, with the concomitant release of four ammonium molecules and one molecule of carbon dioxide (Fig. 1). Except for arginine decarboxylase, enzymes of the ADC pathway are induced by agmatine or its intermediate compounds, but not by arginine (16, 25). Since agmatine can serve as the precursor of polyamines (Fig. 1), it was assumed that the ADC pathway supplies polyamines when arginine is abundant and is in fact a route of agmatine utilization as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen (25).

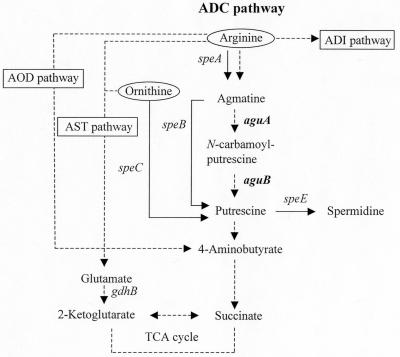

FIG. 1.

Schematic presentation of pathways for arginine catabolism and polyamine biosynthesis. Only key compounds and genes in the ADC pathway and polyamine biosynthesis are shown. The catabolic genes between putrescine and glutamate have not been identified. Solid and broken arrows represent biosynthetic and catabolic pathways, respectively. ADI, arginine deiminase; AST, arginine succinyltransferase; AOD, arginine oxidase; TCA, tricarboxylic acid. The speA, speB, speC, and speE genes encode biosynthetic arginine decarboxylase, agmatine ureidohydrolase, ornithine decarboxylase, and spermidine synthase, respectively (11). The aguAB genes encode agmatine deiminase and N-carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase, as characterized in this study, and the catabolic glutamate dehydrogenase is encoded by gdhB (22).

In the ADC pathway of P. aeruginosa, conversion of agmatine into putrescine requires two distinct enzymes: agmatine deiminase and N-carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase. This process is different from that in putrescine biosynthesis, where the conversion is catalyzed by agmatine ureohydrolase, encoded by speB (11), a member of the arginase/agmatinase family of carbon-nitrogen hydrolases (32, 35). Haas and coworkers (16) have isolated agmatine deiminase (aguA) and N-carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase (aguB) mutants, which are defective in agmatine utilization. The high percentage of cotransduction between these two genes and the parallel induction of their encoding enzymes by exogenous agmatine strongly suggest the presence of a single transcriptional unit for aguA and aguB (16).

We initiated this study to further understand the role and regulatory mechanism of the ADC pathway in arginine and agmatine utilization by P. aeruginosa. In this report, we cloned the aguBA operon and established its expression from an agmatine-inducible promoter. Regulation of aguBA by exogenous agmatine was abolished in a strain carrying a mutation in the adjacent upstream aguR gene. We demonstrated the possible interactions between AguR and the regulatory region of the aguBA operon in vitro. In addition, the assignment of agmatine deiminase activity to the AguA protein led to the discovery of a new family of carbon-nitrogen hydrolases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

Strains and plasmids used in this study are given in Table 1. Nutrient yeast broth (NYB) or Luria-Bertani (LB) medium was used to grow P. aeruginosa PAO and Escherichia coli with supplementation with antibiotics when appropriate (24). For enzyme and fusion assays, P. aeruginosa strains were grown in minimal medium P (MMP) with supplements of the indicated carbon and nitrogen sources at 20 mM as described previously (15).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| PAO1 | Wild type | 30 |

| PAO1-Sm | Spontaneous Smr of PAO1 | This study |

| PAO4151 | aguA9001 | 16 |

| PAO4179 | aguB9001 arcA9001 | 16 |

| PAO4495 | aguR::ΩSp/Sm | This study |

| PAO4505 | aguB::Gm | This study |

| PAO5001 | aguA::Tc | This study |

| PAO5002 | aguB::Tc | This study |

| PAO5003 | aguR::Tc | This study |

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | F−/endA1 hsdR17(rK− mK+) supE44 thi-1 recA1 gyrA relA1 Δ(lacIZYA-argF)U169 deoR [φ80dlacΔ(lacZ)M15] | Bethesda Research Laboratories |

| HB101 | supE44 hsdS20(rB− mB−) recA13 ara-14 proA2 lacY galK2 rpsL20 xyl-5 mtl-1 | 24 |

| S17-1 | pro thi hsdR Tpr Smr; chromosome::RP4-2 Rc::Mu-Km::Tn7 | 36 |

| SM10 | thi-1 thr leu tonA lacY supE recA::RP4-2-Tc::Mu (Kmr) | 17 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEX18Ap | Apr, ColE1 replicon, oriT sucB | 17 |

| pHP45ΩSp/Sm | Apr, pBR322 derivative, ΩSp/Sm | 8 |

| pGU2 | Apr, cosmid clone carrying agu locus | This study |

| pGU103 | Apr, pQF52 derivative carrying Pagu-lacZ fusion | This study |

| pNIC6011 | Apr, pACYC177 and pVS1 replicons | 29 |

| pQF52 | Apr, lacZ translational fusion vector derived from broad-host-range plasmid pQF50 | 34 |

| pRK2013 | Kmr, tra (RK2) | 6 |

| pRTP1 | Apr, conjugation vector | 39 |

| pSP858 | Apr, pBR322 derivative carrying Gm-GFP cassette | 17 |

| pYJ101 | Apr, pNIC6011 derivative carrying aguRBA | This study |

| pYJ102 | Apr, pNIC6011 derivative carrying aguRBA | This study |

| pBAD-HisA | Apr, protein expression vector by arabinose induction | Invitrogen |

| pGU300 | Apr, for overproduction of AguR | This study |

Antibiotic resistance: Apr, ampicillin for E. coli and carbenicillin for P. aeruginosa; Gmr, gentamicin; Kmr, kanamycin; Smr, streptomycin; Spr, spectinomycin, Tcr, tetracycline.

Cloning of agu locus.

The chromosomal DNA of strain PAO1 (20 μg) was digested partially with 0.5 U of restriction endonuclease Sau3AI (Toyobo Biochemicals) in 1 ml of the reaction buffer recommended by the supplier. The DNA fragments were separated through agarose gel electrophoresis, and the DNA fragments of 5 to 10 kb were extracted from the gel using a GFX PCR and gel band purification kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The DNA fragments were then ligated to the BglII site on the shuttle vector pNIC6011 (1 μg) (accession no. AB043581). The ligated DNA was subsequently introduced into E. coli XL1-Blue electrocompetent cells (Stratagene) by electroporation (200 Ω, 1.8 V, 250 μF) using a Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad). The electroporated cells were then incubated in 1 ml of SOC medium (24) at 37°C for 60 min, and incubation was continued overnight after addition of ampicillin (100 μg/ml) with shaking.

A portion (100 μl) of the culture was mixed with the same volume of strain PAO4151 (aguA9001) culture, which was grown in NYB at 43°C overnight without shaking, and of the helper E. coli HB101/pRK2013 (6) culture grown at 37°C overnight. Cells were spun down, suspended in 30 μl of NYB, and placed on NYB agar. Triparental mating was performed at 37°C for 2 h. The mated cells on NYB agar were patched off and suspended in sterilized saline at a cell concentration of about 5 × 108/ml. A portion (100 μl) was spread onto MMP agar medium supplemented with 20 mM agmatine as the sole carbon and nitrogen source. Colonies that appeared on MMP-agmatine plates (4.7 × 10−7 per recipient cell) were tested for carbenicillin resistance. Plasmids were recovered from the Cbr/Agu+ clones and reintroduced into strain PAO4151 via E. coli S17-1 (36). Two plasmids, pYJ101 and pYJ102, were chosen, and the nucleotide sequences of their inserts were determined.

An aguRBA cosmid clone, pGU2, was identified from a P. aeruginosa PAO1 genomic library (21) by colony hybridization using a DNA fragment covering the aguR-aguB intergenic region (see below) as a probe. Labeling of the probe with digoxigenin-11-dUTP and detection of the hybridized colonies were performed using a Genius System as described by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim). The chromosomal content of pGU2 was analyzed by nucleotide sequencing with flanking primers of the cosmid vector Supercos 1 (Stratagene) and confirmed by sequence comparison with the genomic sequence of P. aeruginosa PAO1 (www.pseudomonas.com).

Complementation tests.

A variety of plasmids derived from pYJ102 were constructed by deletion and/or insertion of the ΩSp/Sm cassette (8) as summarized in Fig. 2 and Table 1. The ΩSp/Sm cassette carrying a streptomycin resistance gene and two flanking transcriptional terminators was inserted as a BamHI fragment between the BglII sites on aguR to produce pYI1000. Plasmid pYI1001, having a 972-bp deletion in the 3′ half of aguA, was obtained by XhoI digestion and subsequent self-ligation. Removal of the 288-bp MulI-Eco81I fragment at the 3′ half of aguB resulted in pYI1002. Insertion of ΩSp/Sm between the same MulI and Eco81I sites gave rise to pYI1003. These plasmids were transformed into PAO4151 (aguA) and PAO4179 (aguB), and the resulting transformants were tested for their ability to grow on MMP plates with agmatine (10 mM) as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen after incubation at 37°C for 24 h.

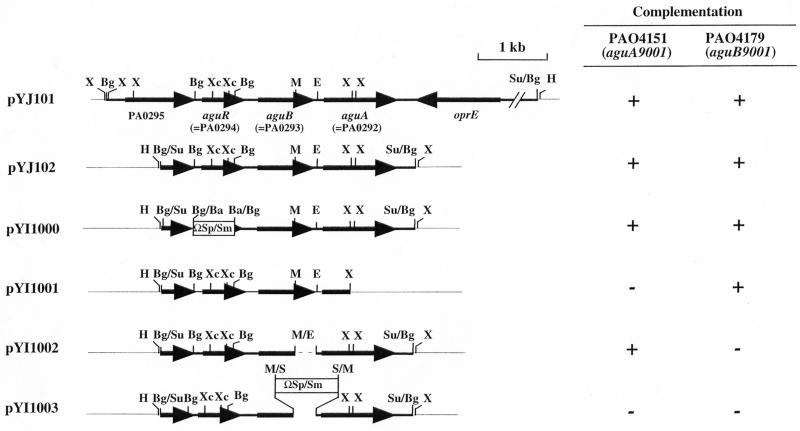

FIG. 2.

Organization of agu locus and complementation tests of aguA and aguB mutants. Plasmid pYJ102 and its deletion derivatives were introduced into strains PAO4151 (aguA9001) and PAO4179 (aguB9001) by triparental conjugation as described in Materials and Methods. Growth of the resulting strains was tested on MMP agar plates containing 20 mM agmatine as the sole carbon and nitrogen source. +, growth of single colonies in 24 h; −, no growth in 24 h. Abbreviations for restriction sites: Ba, BamHI; Bg, BglII; E, Eco81II; H, HindIII; M, MluI; S, SmaI; Su, Sau3AI; X, XhoI; Xc, XcmI. Only distal Sau3AI sites of inserts are shown, and right junction of the vector and insert in pYJ101 produced an XhoI site. ΩSp/Sm, the interposon cassette carrying the spectinomycin/streptomycin resistance gene (8). The PA gene numbers in the figure are in accordance with the current genome annotation project (www.pseudomonas.com).

Construction of mutant strains.

Knockout mutants of aguR and aguB were constructed by gene replacement according to the procedure of Hoang et al. (17). The 3.2-kb XhoI fragment containing aguRBA′ was first cloned into the conjugation vector pEX18Ap (mob+ sucB) (17) at the SalI site, resulting in pYI1004. The SmaI ΩSp/Sm cassette (8) was inserted between two XcmI sites of aguR on pYI1004. Likewise, the gentamicin resistance (Gmr) cassette (17) was inserted as an SmaI fragment at the flush MluI site on aguB. The resulting plasmids were then conjugated into strain PAO1 via E. coli S17-1, and transconjugants having a plasmid integrated into the chromosome by single crossover were selected on MMP-glutamate plates containing 125 μg of carbenicillin/ml. After confirming the inheritance of the Smr or Gmr marker, strains PAO4495 (aguR::ΩSp/Sm) and PAO4505 (aguB::Gm) that had lost the plasmid sequence in the chromosome by second crossover were selected on LB agar containing 5% sucrose. Correct insertions of the ΩSp/Sm or Gm cassette into the target genes were verified by Southern blot (24).

The EZ::TN <TET-1> insertion system (Epicentre), based on in vitro Tn5 transposition (12), was used for the generation of insertion mutants of aguA, aguB, and aguR. An 11-kb EcoRI fragment harboring the aguRBA locus was purified from cosmid pGU2 and subcloned into the EcoRI site of conjugation vector pRTP1 (39). The resulting plasmid was incubated with transposase and an artificial transposon with a tetracycline resistance marker in the conditions suggested by the manufacturer. After the reaction, the reaction mixture was used to transform E. coli DH5α, and Tcr transformants were selected on LB plates with 10 μg of tetracycline/ml. The transposon insertion sites of mutant clones were mapped by NcoI restriction endonuclease digestion and subsequently by nucleotide sequencing with a transposon-specific flanking primer. For gene replacement, the resulting transposon insertion plasmids were introduced into E. coli SM10 by transformation and then mobilized into strain PAO1-Sm, a spontaneous streptomycin-resistant mutant of strain PAO1, by conjugation as described by Gambello and Iglewski (10). Following incubation at 37°C overnight, Tcr Smr transconjugants were selected on LB plates supplemented with tetracycline (50 μg/ml) and streptomycin (300 μg/ml).

Construction of aguB::lacZ translational fusion.

Plasmid pQF52, a broad-host-range lacZ translational fusion vector (34), was used to construct an aguB promoter-lacZ fusion. The 318-bp aguR-aguB intergenic region (Fig. 3B) was amplified by PCR with two oligonucleotide primers, 5′-CGCCTGGCGGAAGAAGGC-3′ (forward primer; nucleotides [nt] 1 to 18 of Fig. 3B) and 5′-GGCATCTGGGTGGCGG-3′ (reverse primer; complementary to nt 303 to 318 of Fig. 3B). The amplified DNA fragment was then cloned into the SmaI site of pQF52 so that the 13th codon of aguB was fused in frame to lacZ of the vector, giving rise to pGU103. The orientation and nucleotide sequence of the insert on this plasmid were confirmed by nucleotide sequencing.

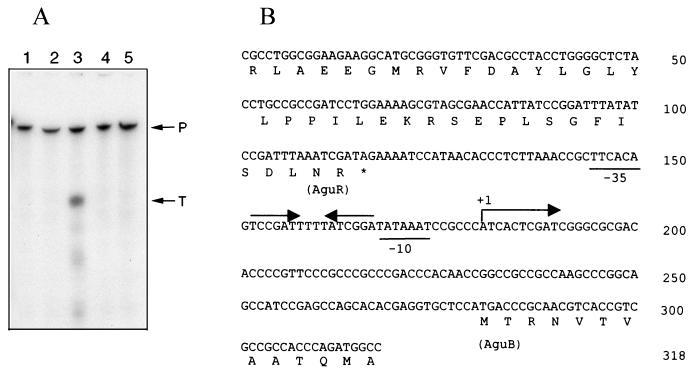

FIG. 3.

(A) S1 nuclease mapping of aguBA transcripts. RNA samples and the radioactive probe for S1 nuclease mapping were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Lane 1, negative control with yeast tRNA; lanes 2 to 5, RNA samples from cells grown in arginine, agmatine, putrescine, and spermidine, respectively. P, intact DNA probe (318 bp); T, a protected DNA probe (138 bp) from hybridization with the aguBA transcript and thus resistance to S1 nuclease digestion. (B) The nucleotide sequence of the aguBA promoter and its flanking regions. The 5′ end of the aguBA transcript is indicated as +1, and the possible −10 and −35 sequences for the corresponding promoter are underlined. The inverse arrows above the sequence indicate a putative palindromic operator site for AguR.

S1 nuclease mapping.

RNA samples were prepared from P. aeruginosa PAO1 growing exponentially in MMP supplemented with the indicated carbon and nitrogen sources. A 30-ml portion of the culture was collected by centrifugation at 12,000 × g at 4°C for 5 min, and RNA was purified from the suspended cell pellet as previously described (30). For S1 nuclease mapping, a 318-bp DNA fragment covering the aguR-aguB intergenic region (Fig. 3B) was generated by PCR and radioactively labeled. The forward and reverse primers described above for the construction of pGU103 were used in the amplification reaction, with the reverse primer end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England BioLabs). The resulting radioactive probe was purified after agarose gel electrophoresis. Procedures for hybridization and S1 nuclease digestion were followed as described by Greene and Struhl (13). The size of the transcript was determined against a nucleotide sequencing ladder.

Enzyme assays.

P. aeruginosa strains were grown to an optical absorbance at 600 nm of 0.5 in MMP medium containing the indicated carbon and nitrogen sources at 20 mM and harvested by centrifugation. Cell extracts were prepared by passing cells through a French pressure cell at 8,000 lb/in2. The agmatine deiminase was measured by colorimetric determination of N-carbamoylputrescine according to Mercenier et al. (25). The reaction for N-carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase activity assay was also performed as described by Mercenier et al. (25), and the amount of ammonia generated from the reaction was determined using an ammonia test kit (Wako Chemicals). One unit of enzyme activity was defined as the amount of the enzyme that yielded 1 μmol of product per min.

For determination of lacZ fusion expression, the levels of β-galactosidase activity in logarithmically growing cells were measured using ο-nitrophenyl-β-galactopyranoside as the substrate (27) with cell extracts prepared as described above. Protein concentration was determined using a protein assay kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Expression of aguR in E. coli.

The pBAD protein expression system by arabinose induction (Invitrogen) was employed for overproduction of the AguR protein. The aguR structural gene and its ribosome-binding site were amplified by PCR with two flanking oligonucleotide primers. The resulting PCR product was digested with NcoI and EcoRI, which are unique restriction sites flanking the PCR product as introduced by the primers, and cloned into the same restriction sites of the expression vector pBAD-HisA. The resulting plasmid, pGU300, was introduced into E. coli Top10. For overexpression of aguR, the recombinant strain of E. coli was growing logarithmically in LB medium, and 0.2% (wt/vol; final concentration) arabinose was added to the culture for induction. The culture growth was continued for another 4 h, and cells were collected by centrifugation. To detect overproduction of AguR, the cell pellet was suspended in 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 1 mM EDTA, and the cells were ruptured by an Aminco French pressure cell. The cell-free crude extract was prepared after centrifugation at 48,000 × g for 30 min. A small fraction of the crude extract was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on a 10% polyacrylamide gel, and the protein profile was visualized by Coomassie blue staining.

Gel retardation experiments.

A DNA fragment carrying the regulatory region of the aguBA operon was obtained from pGU103 by digestion with HindIII and BamHI endonucleases and radioactively labeled by DNA polymerase Klenow fragment with [α-32P]dATP. The radioactively labeled DNA probe (5 × 10−10 M) was allowed to interact with different amounts of the cell-free crude extract as described above in 20 μl of the reaction buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 50 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 50 μg of bovine serum albumin/ml. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 20 min at 25°C and then applied to a 5% polyacrylamide gel while the gel was running. The gel was dried and autoradiographed.

Synthesis of N-carbamoylputrescine.

N-Carbamoylputrescine was synthesized from putrescine and cyanate and purified according to Smith and Garraway (37). Molecular mass (132 Da; N-carbamoylputrescine + H+) of the synthetic N-carbamoylputrescine was confirmed by a matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometer (Reflex II; Brucker Daltonics) using α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid as the matrix. Purity of the synthetic N-carbamoylputrescine was over 97% as estimated by high-pressure liquid chromatography using a 5-μm C18 3,000-Å column (Waters) with 5% acetonitrile (pH 3.5) as the running solution (1 ml/min).

RESULTS

Cloning and characterization of aguBA genes. P. aeruginosa mutants PAO4151 (aguA9001) and PAO4179 (aguB9001), defective in agmatine utilization, have been isolated (16). The affected genes encoding agmatine deiminase (aguA) and N-carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase (aguB) were 98% cotransducible (16) and mapped in the 19-min region of the P. aeruginosa chromosome (18).

To clone the agu locus, a shotgun genomic library of P. aeruginosa PAO1 was constructed and used for clone identification by complementation as described in Materials and Methods. Two plasmids, pYJ101 and pYJ102, that restored the agmatine-utilizing (Agu+) phenotype of strain PAO4151 (aguA9001) were obtained. As anticipated from the high cotransduction frequency between aguA and aguB, these plasmids also restored the Agu+ phenotype of strain PAO4179 (aguB9001). Sequencing the inserts revealed that plasmids pYJ101 and pYJ102 both have a 3.8-kb region (Fig. 2), and the nucleotide sequence of this region is identical to that of the corresponding region of the P. aeruginosa PAO1 chromosome determined by the Pseudomonas Genome Project (40). According to the annotation of the Pseudomonas Genome Project, this DNA region contains three putative genes, PA0292, PA0293, and PA0294, of unknown function (accession no. AE004467) (Fig. 2).

Knockout mutations of genes PA0294, PA0293, and PA0292 were constructed by in vitro transposon mutagenesis followed by biparental conjugation as described in Materials and Methods, yielding strains PAO5003 (PA0294), PAO5002 (PA0293), and PAO5001 (PA0292). Utilization of agmatine by these mutants as the sole C and N source was checked on MMP plates. It was found that PAO5001 and PAO5002 exhibited a growth defect on agmatine, while PAO5003 grew normally in comparison to the wild-type parent strain. Furthermore, PAO5001 was totally defective in growth, while PAO5002 gave faint growth on the agmatine plates and showed no growth in the liquid medium with agmatine as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen. All three mutants grew normally on other compounds, including glutamate, arginine, and putrescine, as the sole sources of carbon and nitrogen in the minimal medium. These results indicated the importance of the PA0292 and PA0293 genes in agmatine utilization.

To further identify the aguA and aguB genes among these three putative genes, a series of mutant plasmids derived from pYJ102 by deletion or insertion were constructed and used for complementation tests, as summarized in Fig. 2. Plasmid pYI1000 (PA0294::ΩSp/Sm) with intact PA0293 and PA0292 retained the ability to complement both the aguA9001 and aguB9001 mutations. Plasmid pYI1001, having a deletion in PA0292, restored only aguB9001. In contrast, plasmid pYI1002,having a deletion in PA0293, conferred the Agu+ phenotype on aguA9001. These results indicated that the aguA9001 and aguB9001 mutations are localized in the PA0292 and PA0293 genes, respectively. Therefore, PA0292 and PA0293 were designated aguA and aguB, respectively.

Sequence analyses of proteins encoded by aguA and aguB.

As deduced from the nucleic acid sequence, the aguA gene encodes a polypeptide of 368 residues with a calculated molecular mass of 41,190 Da. While the AguA protein was expected to have agmatine deiminase activity, its amino acid sequence showed no significant similarity to any known carbon-nitrogen hydrolase, including arginine deiminase (the arcA product) in the arginine deiminase pathway of this strain (4). However, the Blast search (2, 3) did indicate the presence of several orthologues of AguA in other bacteria with no suggested function: Cj0949c of Campylobacter jejuni (27% identity, accession no. AL139076), CC0211 of Caulobacter crescentus (33% identity, AE005695), DR2359 of Deinococcus radiodurans (36% identity, AE002066), HP0049 of Helicobacter pylori (28% identity, AE000526), SC1C2.08 of Streptomyces coelicolor (38% identity, AL031124), XF2442 of Xylella fastidiosa (32% identity, AE004053), Zmorf3 of Zymomonas mobilis (33% identity, AF124349), and YrfC of Lactococcus lactis (53% identity, AE006400). Orthologues with higher similarities also occur in Arabidopsis (T22D6_110; 56% identity, AL357612) and in chlorella virus PBCV-1 (A638R; 49% identity, AAC96446).

On the other hand, the deduced AguB protein (292 residues; molecular mass, 32,759 Da), with an expected N-carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase activity, displayed significant sequence homology to plant hydrolases such as putative β-ureidopropionases (= β-alanine synthases) of tomato (63% identity; accession no. CAB45873) and Arabidopsis thaliana (67% identity, AC006232) and of chlorella virus PBCV-1 (A78R; 47% identity, AAC96446). In addition, it also had moderate homology to nitrilase/Nit protein 2 (31% identity, AF260334) and β-ureidopropionase (30% identity, BAA88634) of humans and other animals, as well as to bacterial N-carbamoyl-d-amino acid amidohydrolase (32% identity, JW0083). These findings showed that the aguB product is a member of the β-alanine synthase/nitrilase family of carbon-nitrogen hydrolases (5, 28).

Specific induction of aguBA operon by agmatine and N-carbamoylputrescine.

The following evidences supported the structure of the aguBA operon and the expression of aguBA as a single transcriptional unit from a promoter in the intergenic region between aguB and PA0294. First, a secondary structure resembling a bidirectional rho-independent transcriptional terminator was found in the intergenic region of aguA and the convergent oprE (data not shown). Second, no rho-independent transcription terminator was found in the aguB-aguA intergenic region of 86 bp. Third, insertion of an ΩSp/Sm interposon carrying two flanking transcriptional terminators into aguB abolished the expression of downstream aguA (pYI1003, Fig. 2). And fourth, expression of aguBA was not affected by insertion of an ΩSp/Sm interposon into the upstream PA0294 gene (pYI1000, Fig. 2).

The expression profile of aguBA was analyzed by measurements of agmatine deiminase and N-carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase activities. In the wild-type strain P. aeruginosa PAO1, both enzymes were induced coordinately in media containing either agmatine or N-carbamoylputrescine (Table 2). In addition, the induction effect of agmatine is about twofold higher than that of N-carbamoylputrescine, and the induction patterns persisted in the aguA (PAO4151) and aguB (PAO4179) backgrounds despite their respective agmatine deiminase and carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase deficiencies. Exogenous arginine and putrescine had no apparent effect on the levels of these two enzyme activities (data not shown). These results were consistent with those in the previous reports (16, 25) and were in accordance with the operon structure of aguBA.

TABLE 2.

Regulation of agmatine deiminase and N-carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase synthesis

| Enzyme source | Supplementsa | Sp act

(U/mg of protein)b

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Agmatine deiminase | N-Carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase | ||

| PAO1 (wild type) | Suc + NH4 | 2 ± 0 | 3 ± 1 |

| Glu | 3 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | |

| Agm | 50 ± 3 | 17 ± 3 | |

| N-CP | 26 ± 2 | 8 ± 0 | |

| Glu + Agm | 31 ± 2 | 11 ± 1 | |

| Glu + N-CP | 22 ± 0 | 6 ± 2 | |

| Suc + Agm | 25 ± 1 | 8 ± 0 | |

| Suc + N-CP | 21 ± 0 | 5 ± 1 | |

| PAO4151 (aguA9001) | Glu | <1 | 2 ± 1 |

| Glu + Agm | <1 | 11 ± 4 | |

| Glu + N-CP | <1 | 5 ± 0 | |

| PAO4179 (aguB9001) | Glu | 2 ± 1 | <1 |

| Glu + Agm | 42 ± 5 | <1 | |

| Glu + N-CP | 26 ± 2 | 1 ± 0 | |

| PAO4495 (aguR::ΩSp/Sm) | Suc + NH4 | 52 ± 4 | 19 ± 2 |

| Glu | 56 ± 2 | 20 ± 1 | |

| Agm | 73 ± 7 | 25 ± 1 | |

| N-CP | 57 ± 3 | 20 ± 2 | |

Cells were grown to an optical density at 660 nm of 0.5 in MMP containing the indicated supplements as the C and N sources at 20 mM. Cell extracts and enzyme assays were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Agm, agmatine; Glu, glutamate; N-CP, N-carbamoylputrescine; Suc, succinate.

Values are averages of three independent measurements with standard errors.

Identification of a promoter for aguBA operon.

The expression of aguBA from an inducible promoter was further investigated using plasmid pGU103, which carries the 318-bp intergenic region between PA0294 and aguB fused in frame to lacZ at the 13th codon of aguB. Cells were grown in MMP-glutamate medium in the presence of other supplements as indicated in Table 3. In the wild-type strain PAO1 harboring pGU103, the level of β-galactosidase activity was induced sevenfold by agmatine, and no significant effect of either arginine or polyamines (putrescine and spermidine) was observed. These results demonstrated the presence of an agmatine-inducible promoter in the 318-bp regulatory region upstream of the aguBA operon.

TABLE 3.

Measurements of β-galactosidase activity in strains of P. aeruginosa harboring the aguB::lacZ translational fusion pGU103

| Strain (genotype) | Supplementsa | β-Galactosidase sp actb (nmol/min/mg) |

|---|---|---|

| PAO1 (wild type) | Glu | 88 |

| Glu + Agm | 703 | |

| Glu + Put | 100 | |

| Glu + Spd | 86 | |

| Glu + Arg | 133 | |

| PAO5003 (aguR) | Glu | 1,026 |

| Glu + Agm | 1,111 | |

| Glu + Put | 1,294 | |

| Glu + Spd | 1,000 | |

| Glu + Arg | 1,063 |

Cells were grown in MMP medium with supplements as indicated at 20 mM. Glu, glutamate; Agm, agmatine; Put, putrescine; Spd, spermidine; Arg, arginine.

Values are the averages of two measurements for each growth condition. The standard errors (not shown) were all below 5% of the corresponding averages.

The location and the expression profile of the aguBA promoter were further investigated by nuclease S1 mapping. The regulatory region of aguBA in pGU103 was radioactively labeled to serve as the probe. When hybridized with RNA samples, a protected DNA probe of 138 bp was detected only with the RNA sample from the agmatine-grown cells (Fig. 3A). These results indicated the presence of a transcript that is inducible by agmatine but not by arginine or polyamines and that starts 99 bp upstream from the ATG initiation codon of aguB (Fig. 3B). The canonical −10 and −35 sequences of ς70 promoters were found at the expected locations from the transcription initiation site of this promoter (Fig. 3B). A palindromic sequence was found overlapping the promoter, which might serve as the binding site for the regulatory protein AguR (see below).

Abolishment of agmatine- and N-carbamoylputrescine-dependent induction of aguBA in aguR (PA0294) mutants.

As described earlier, inactivation of gene PA0294 (strain PAO5003) immediately upstream of aguBA does not affect the ability to use agmatine, and plasmid pYI1000 with an ΩSp/Sm interposon inserted in PA0294 still complements the aguA9001 and aguB9001 mutations (Table 2). The PA0294 gene encodes a potential polypeptide of 221 amino acid residues with a calculated molecular mass of 24,424 Da that shows low but apparent homology (overall identity of 22% or less) with repressor proteins of the TetR family (31) by Blast search against the protein database. As described below, inactivation of PA0294 indeed resulted in constitutive expression of the aguBA operon, and therefore this gene was designated aguR.

To investigate the potential repressor function of AguR on regulation of the aguBA operon, the levels of agmatine deiminase and N-carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase activities in the aguR null mutant PAO4495 were measured in different growth conditions. As shown in Table 2, while agmatine deiminase and N-carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase activities were induced by agmatine and N-carbamoylputrescine in the wild-type strain PAO1, these two enzymes became constitutively induced in PAO4495 under all growth conditions tested. The effect of aguR was also examined using the aguB::lacZ translational fusion pGU103. As shown in Table 3, strain PAO5003 harboring pGU103 produced constitutively high levels of β-galactosidase activity in all growth media tested (in comparison to those in the wild-type strain PAO1). These results support that the AguR protein could serve as a repressor protein of the aguBA operon.

Binding of AguR to regulatory region of aguBA.

For overproduction of the AguR protein, a recombinant strain of E. coli Top10 harboring pGU300 was constructed as described in Materials and Methods. After induction by exogenous arabinose, the cell-free crude extract of this recombinant strain was prepared, and overproduction of AguR was confirmed by SDS-PAGE following Coomassie blue staining (data not shown). Gel retardation assays were employed to demonstrate the binding of recombinant AguR to the aguBA regulatory region (Fig. 3B) and the results are shown in Fig. 4. When mixed with increasing amounts of the E. coli extract containing AguR, corresponding increases in the retarded aguBA probe were observed, indicating specific interactions between AguR and the aguBA regulatory region.

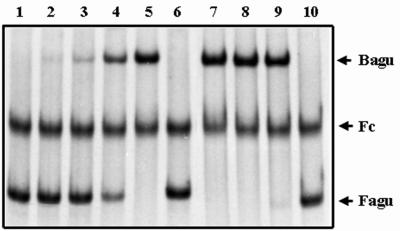

FIG. 4.

Gel retardation assays of AguR and the regulatory region of aguBA. The cell-fee crude extract from an AguR-overproducing strain of E. coli was prepared and employed in the binding reactions as described in Materials and Methods. Fagu, the unbound probe of the aguBA regulatory region; Fc, the unbound probe of a control DNA fragment; Bagu, the bound probe of the aguBA regulatory region. Lanes 1 to 5 contained 0, 25, 50, 100, and 200 ng of proteins from the crude extract, respectively. Lane 6, 200 ng of proteins from the crude extract of E. coli harboring vector pBAD-HisA. Lanes 7 to 10, 200 ng of AguR-containing crude extracts in the presence of 1 mM arginine, putrescine, spermidine, and agmatine, respectively.

The potential effects of agmatine, putrescine, spermidine, and arginine on the DNA-binding activity of AguR were also analyzed in vitro. It was found that when included in the reaction mixtures (final concentration, 1 mM), only agmatine (lane 10 of Fig. 4) significantly inhibited the formation of an AguR-DNA complex, while no apparent effect was observed with the other three compounds (lanes 7 to 9).

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have identified the aguBA operon encoding N-carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase and agmatine deiminase for agmatine utilization in P. aeruginosa. The assignment of AguA as an agmatine deiminase led to the discovery of a new family of carbon-nitrogen hydrolases. Except for Lactococcus lactis, all organisms ranging from bacteria to Arabidopsis that possess an AguA orthologue tend to conserve the AguB counterpart on the same genome. The aguA and aguB genes are contiguous or very close in some of these organisms, including C. jejuni, C. crescentus, X. fastidiosa, and Z. mobilis. In lactic bacteria, N-carbamoylputrescine formed from agmatine by agmatine deiminase is converted by putrescine carbamoyltransferase, but not by N-carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase, with the concomitant formation of carbamoylphosphate, which is then used to generate ATP by carbamate kinase (7). Although the functions of these AguA and AguB orthologues remain to be demonstrated, wide distribution of the aguAB homologues as a pair implies their participation in agmatine metabolism in these organisms.

The aguBA operon is essential for agmatine utilization as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen, and aguBA mutants do not show any growth defect with other compounds in the minimal medium. However, this does not rule out a possible involvement of aguBA in the biosynthesis of polyamines (putrescine and spermidine) from arginine via the arginine decarboxylase pathway in P. aeruginosa. Although little research has been done on polyamine biosynthesis in P. aeruginosa PAO1, this organism appears to possess homologues of the E. coli speA (PA4839) and speC (PA4519) genes and two putative speB genes (PA0288 and PA1421) as well as the speE gene (PA1687) for polyamine synthesis (11). Experiments with speB and speC mutants of P. aeruginosa are needed to clarify the function of aguBA in polyamine biosynthesis.

In contrast to a tight block by aguA mutations, a leaky growth defect on agar plates caused by aguB mutations on agmatine and N-carbamoylputrescine utilization has been observed in this study and a previous report (16). This leaky growth phenotype of aguB mutants on agar plates was detected in both a chemically induced mutant (PAO4179) and transposon insertion mutants (PAO4505 and PAO5003). This might be due to the presence of another hydrolase with some affinity for N-carbamoylputrescine and/or by autohydrolysis of N-carbamoylputrescine to support limited growth of aguB mutants on agmatine and N-carbamoylputrescine.

Expression of aguBA is induced specifically by agmatine and N-carbamoylputrescine from a promoter in the aguR-aguB intergenic region. The aguBA promoter is not regulated by arginine or polyamines (Table 3 and Fig. 3A), supporting the function of aguBA in agmatine catabolism. In addition, this promoter activity contributes most if not all of the aguBA expression, as insertion of an ΩSp/Sm cassette in the upstream aguR gene did not reduce the levels of agmatine deiminase and N-carbamoylputrescine amidohydrolase activities (Table 2). Instead, we have found that the aguBA promoter became constitutive in the aguR mutants. As suggested by the results of sequence comparison, the AguR protein could serve as the repressor protein in regulation of the aguBA operon. The results of gel retardation experiments (Fig. 4) indicated the interactions of AguR overexpressed in E. coli and the aguBA regulatory region. A palindromic sequence overlapping the agu promoter (Fig. 3B) might serve as a good candidate for the AguR operator yet to be identified. Our results (Fig. 4) also suggested an agmatine-specific inhibition effect on the DNA-binding activity of AguR. It is tempting to hypothesize that the DNA-binding activity of AguR is modulated by the intracellular concentrations of agmatine and N-carbamoylputrescine. Binding of either of these two sensor compounds to AguR would abolish the interactions of AguR with its target operator on the aguBA promoter region and thus induce expression of the aguBA operon. Studies to demonstrate the binding of agmatine and N-carbamoylputrescine to purified AguR and their effects on AguR-DNA interactions are currently in progress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. Haas and H. P. Sweizer for strains and plasmids, respectively, and Ahmed T. Abdelal for careful review of the manuscript. We also appreciate M. O-Kameyama for help in MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry analysis.

This work was supported in part by research grant MCB-9985660 from the National Science Foundation to C.D.L.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdelal A T, Bibb W F, Nainan O. Carbamate kinase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: purification, characterization, physiological role, and regulation. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:1411–1419. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.3.1411-1419.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baur H, Luethi E, Stalon V, Mercenier A, Haas D. Sequence analysis and expression of the arginine deiminase and carbamate kinase genes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Eur J Biochem. 1989;179:53–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bork P, Koonin E V. A new family of carbon-nitrogen hydrolases. Protein Sci. 1994;3:1344–1346. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comai L, Schilling-Cordaro C, Mergia A, Houck C M. A new technique for genetic engineering of AgrobacteriumTi plasmid. Plasmid. 1983;10:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(83)90054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunin R, Glansdorff N, Pierard A, Stalon V. Arginine biosynthesis and metabolism in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:314–352. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.3.314-352.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fellay R, Frey J, Krisch H. Interposon mutagenesis of soil and water bacteria: a family of DNA fragments designed for in vivoinsertional mutagenesis of Gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 1987;52:147–154. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galimand M, Gamper M, Zimmermann A, Haas D. Positive FNR-like control of anaerobic arginine degradation and nitrate respiration in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1598–1606. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.5.1598-1606.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gambello J R, Iglewski B H. Cloning and characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasRgene, a transcriptional activator of elastase expression. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3000–3009. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.3000-3009.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glansdorff N. Biosynthesis of arginine and polyamines. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 408–433. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goryshin I Y, Reznikoff W S. Tn5 in vitrotransposition. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7367–7374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greene J M, Struhl K. S1 analysis of mRNA using M13 template. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1993. pp. 4.6.2–4.6.13. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haas D, Galimands M, Gamper M, Zimmermann A. Arginine network of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: specific and global controls. In: Silver S, Chakrabarty A-M, Iglewski B, Kaplan S, editors. Pseudomonas: biotransformations, pathogenesis, and evolving biotechnology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1990. pp. 303–316. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haas D, Holloway B W, Schambock A, Leisinger T. The genetic organization of arginine biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Gen Genet. 1977;154:7–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00265571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haas D, Matsumoto H, Moretti P, Stalon V, Mercenier A. Arginine degradation in Pseudomonas aeruginosamutants blocked in two arginine catabolic pathways. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;193:437–444. doi: 10.1007/BF00382081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoang T T, Karhoff-Schweizer R R, Kutchma A J, Schweizer H P. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequence: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosamutants. Gene. 1998;212:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holloway B W, Romling U, Tummler B. Genomic mapping of Pseudomonas aeruginosaPAO. Microbiology. 1994;140:2907–2929. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-11-2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itoh Y. Cloning and characterization of the aru genes encoding enzymes of the catabolic arginine succinyltransferase pathway in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7280–7290. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7280-7290.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jann A, Stalon V, Vander Wauven C, Leisinger T, Haas D. N2-succinylated intermediates in an arginine catabolic pathway of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4937–4941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwon D H, Lu C D, Walthall D A, Brown T M, Houghton J E, Abdelal A T. Structure and regulation of the carAB operon in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas stutzeri: no untranslated region exists. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2532–2542. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.9.2532-2542.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu C-D, Abdelal A T. The gdhB gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa encodes an arginine-inducible NAD+-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase which is subject to allosteric regulation. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:490–499. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.2.490-499.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu C-D, Winteler H, Abdelal A, Haas D. The ArgR regulatory protein, a helper to the anaerobic regulator ANR during transcriptional activation of the arcD promoter in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2459–2464. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.8.2459-2464.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mercenier A, Simon J P, Haas D, Stalon V. Catabolism of L-arginine by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Gen Microbiol. 1980;116:381–389. doi: 10.1099/00221287-116-2-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mercenier A, Simon J P, Vander Wauven C, Haas D, Stalon V. Regulation of enzyme synthesis in the arginine deiminase pathway of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1980;144:159–163. doi: 10.1128/jb.144.1.159-163.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakai T, Hasegawa T, Yamashita E, Yamamoto M, Kumasaka T, Ueki T, Nanba H, Ikenaka Y, Takahashi S, Sato M, Tsukihara T. Crystal structure of N-carbamoyl-D-amino acid amidohydrolase with a novel catalytic framework common to amidohydrolases. Structure Fold Des. 2000;8:729–737. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00160-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishijyo T, Haas D, Itoh Y. The cbrA-cbrB two-component regulatory system controls the utilization of multiple carbon and nitrogen sources in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:917–931. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishijyo T, Park S M, Lu C D, Itoh Y, Abdelal A T. Molecular characterization and regulation of an operon encoding a system for transport of arginine and ornithine and the ArgR regulatory protein in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5559–5566. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.21.5559-5566.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orth P, Schnappinger D, Hillen W, Saenger W, Hinrichs W. Structural basis of gene regulation by the tetracycline inducible Tet receptor operator system. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:215–219. doi: 10.1038/73324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ouzounis C A, Kyrpides N C. On the evolution of arginase and related enzymes. J Mol Evol. 1994;39:101–104. doi: 10.1007/BF00178255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park S-M, Lu C-D, Abdelal A T. Cloning and characterization of argR, a gene that participates in regulation of arginine biosynthesis and catabolism in Pseudomonas aeruginosaPAO1. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5300–5308. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5300-5308.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park S-M, Lu C-D, Abdelal A T. Purification and characterization of an arginine regulatory protein, ArgR, from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and its interactions with the control regions for the car, argF, and aruoperons. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5309–5317. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5309-5317.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sekowska A, Danchin A, Risler J L. Phylogeny of related functions: the case of polyamine biosynthetic enzymes. Microbiology. 2000;146:1815–1828. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-8-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simon R, Priefer U, Puhler A. A broad-host range mobilization system for in vivogenetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in Gram-negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–790. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith T A, Garraway J L. N-Carbamoylputrescine, an intermediate in the formation of putrescine by barley. Phytochemistry. 1964;3:23–26. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stalon V, Mercenier A. l-Arginine utilization by Pseudomonasspecies. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:69–76. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-1-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stibitz S, Black W, Falkow S. The construction of a cloning vector designed for gene replacement in Bordetella pertussis. Gene. 1986;50:133–140. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stover C V, et al. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosaPAO1, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature. 2000;406:959–964. doi: 10.1038/35023079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tabor C W, Tabor H. Polyamines in microorganisms. Microbiol Rev. 1984;49:81–99. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.1.81-99.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tricot C, Pierard A, Stalon V. Comparative studies on the degradation of guanidino and ureido compounds by Pseudomonas. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:2307–2317. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-11-2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]