Abstract

Diagnosis of bovine viral diarrhea (BVD) relies on the detection of antibodies against its viral causing agent, bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV). Here, we designed a novel competitive ELISA (cELISA) using the most immunogenic part of BVDV nonstructural protein 3 (NS3), as a single ELISA recombinant antigen, along with a monoclonal antibody to detect antibodies against BVDV in sera of infected animals. Hence, 197 serum samples were tested by this cELISA and the results were compared to the results obtained from virus neutralization test (VNT) as the gold standard method for diagnosis of BVD. McNemar’s test indicated that there was no significant difference between the results of this newly designed cELISA and VNT. Meanwhile, kappa coefficients showed that there was a high correlation between these two assays. The relative sensitivity and specificity of cELISA with respect to VNT were 93.90% and 100%, respectively, suggesting that this newly designed cELISA could be a useful diagnostic tool for detection of BVDV infection. Moreover, as NS3 is highly conserved among Pestiviruses and the developed ELISA is a competitive one, it could potentially be applied to detect BVDV infection in other domestic and wildlife species.

Key Words: Bovine viral diarrhea, Competitive ELISA, Nonstructural protein 3

Introduction

Bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) is one of the major pathogens of cattle that belongs to the Pestivirus genus within the Flaviviridae family. Infection with this virus can result in a variety of economically important reproductive disorders including abortions, fetal resorption or congenital malformation of the fetus, and diseases like mucosal disease in persistently infected (PI) animals.1 The BVDV infection can considerably affect cattle industries and starting eradication or control programs by several European countries is proof of this claim.2,3

The viral genome encodes a large polyprotein leading to the production of at least 12 individual structural and nonstructural proteins by post-translational cleavages.4 Among these proteins, nonstructural protein 3 (NS3) has a crucial role in the replication of the viral RNA genome which is attributed to its serine protease and RNA helicase activities.5,6 This 80.00 kDa nonstructural protein is highly conserved among Pestiviruses and is also known to be one of the most immunogenic proteins of the virus.7 Consistently, it was shown that NS3 could induce a strong humoral immune response in cattle exposed to the virus or modified live vaccines.8 Although these antibodies do not neutralize infectivity, they can be readily used in serological assays to identify BVDV infection.9 This makes NS3 an excellent candidate antigen for the development of antibody ELISA assays to detect antibodies against viral infection in sera of infected animals.10

As ELISA is among the most commonly used methods for detection of BVDV antibodies in sera of infected cattle and several ELISA assays have recently been developed to detect BVDV infections using recombinant NS3 protein.7,11-13 Although it has been shown that developed ELISAs using eukaryotically expressed NS3 have higher sensitivity and specificity,12 prokaryotic expression of NS3 is still considered because of the simplicity and less costly process of prokaryotic expression systems with respect to eukaryotic ones. However, because of the nature of the protein and its relatively high molecular weight (~ 75.00 kDa), there are also some complications in the expression of the whole NS3 molecule. As a result, we tried to develop a novel competitive ELISA (cELISA) with a recombinant part of the NS3 molecule, as a single ELISA detector antigen. This part of the NS3 molecule is a 122 amino-acid region (~13.50 kDa) from residue 335 to 456 and has been previously expressed and determined as the most immunogenic part of the NS3 molecule.14 Moreover, a previously produced monoclonal antibody against this part of the NS3 molecule was used as a competitor antibody in this newly developed cELISA. Finally, the results of the cELISA were compared to the results of the virus neutralization test (VNT) and a commercial ELISA kit for corresponding serum samples.

Materials and Methods

Bovine serum samples. A total number of 197 bovine serum samples were collected out of which 123 sera were previously tested by VNT and a commercial ELISA kit (IDEXX Laboratories, Lenexa, USA). Newly collected serum samples (n = 74) in this study were also examined by VNT. All serum samples were first inactivated at 56.00 ˚C for 30 min.

Virus neutralization test. All serum samples were duplicately examined for the presence of virus-neutralizing antibodies against BVDV according to the standard microtitration procedure described in the OIE manual.15 Briefly, 50.00 μL of 1:5 dilution of each serum sample was added into two wells of a 96-wells cell culture microplate. Then, 50.00 μL (150 TCID50) of BVDV-1 (cytopathic NADL strain) was added into each well and the plate was incubated at 37.00 ˚C for 1 hr in a humidified CO2 incubator. Finally, 1.50 × 104 BT cells were added to each well and the microplate was incubated at 37.00 ˚C for five days. The plate was observed daily for the presence of virus cytopathic effects. Four wells were allocated to each of the cell and virus controls and the results were documented comparing to these control.

Preparation of ELISA antigen. A purified recombinant fragment (from amino acid 335 to 456) of whole NS3 protein was used as ELISA single antigen for the development of the present cELISA assay. This protein was a 122 amino-acid peptide (~13.50 kDa) and has been previously shown to be the most immunogenic part of the NS3 molecule. As this fragment was the fourth consecutive fragment (from the beginning of the molecule), it was called F4.14 Coding region DNA of this fragment (from nucleotide 1003 to 1368 of NS3 coding DNA, accession number NC_001461) was previously cloned into pMAL-c2X prokaryotic expression vector. This recombinant vector was expressed (fused with a maltose-binding protein (MBP) at N terminal) in BL21 strain of Escherichia coli (E. coli) followed by purification of the protein with amylose-resin column chromatography.

Monoclonal antibody (MAbs). A panel of six monoclonal antibodies (9N, 13N, 15N, 80N, 172N, and 186N) which had been previously produced against whole recombinant NS3 molecule in our laboratory (data are not shown) were assessed by an indirect ELISA to find the most reactive monoclonal antibody against the purified recombinant F4 fragment of the NS3 molecule.

Competitive ELISA. The optimum concentration of the recombinant F4 fragment as the ELISA antigen, dilution of the monoclonal antibody and conjugated anti-antibody were determined using the checkerboard titration method. The purified recombinant MBP-F4 fusion protein was applied at different concentrations from 690 to 115 ng per well into 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates as ELISA antigen and incubated for 16 hr at 4.00 ˚C. All subsequent incubations were at room temperature and the plates were washed four times with PBST (phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20: all from Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) after each step. Blocking of unreacted sites was carried out for 3 hr using PBST containing 1.00% bovine serum albumin (Merck). After washing the plate, a 1:5 dilution of previously examined positive and negative bovine serum samples in PBST containing prepared 10.00% chicken serum were added to the wells and the plate was incubated for 45 min. Afterward, different dilutions (1:50, 1:100, 1:200, 1:300, 1:400, 1:600, 1:800, 1:1,600) of the determined most reactive monoclonal antibody were added to the wells and the plate was incubated for 30 min. After further washing, a 1:5,000 dilution of anti-mouse IgG-peroxidase conjugate (Sigma, St. Louis, USA) in PBST was added to the wells and incubated for 30 min. The ELISA plate was washed again with PBST and tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Sigma, St. Louis, USA) solution was added to the wells for 10 min incubation. The reactions were then stopped by the addition of 0.10 M HCl (Merck) and finally optical density (OD) values were measured at 450 nm with a plate reader (Pishtaz Teb Co., Tehran, Iran).

Evaluation of serum samples by cELISA. All serum samples were duplicately examined by the newly developed cELISA using the purified recombinant F4 fragment of NS3 molecule as ELISA detector antigen and monoclonal antibody 172N as the competitor antibody.

Statistical analyses. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics software (version 16.0; IBM, Chicago, USA). The OD values of serum sample were used to calculate a sample/negative (S/N) index for each of the tested samples as S/N index = (mean OD value of sample / mean OD value of the negative sample) × 100. Thereafter, the results of the newly developed cELISA were compared to the results obtained from VNT as the gold standard method16 for the corresponding serum samples to determine the cut-off value of cELISA using receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analytical method. The cut-off value was determined as the highest sensitivity, specificity and correlation could be achieved between the results of cELISA compared to the results of VNT. Meanwhile, qualitative analyses of the results of cELISA with those obtained from VNT and the commercial ELISA kit were performed using McNemar’s statistical test. Besides, kappa coefficients (κ) were calculated to assess the degree of agreement between cELISA and two other methods. Thereafter, the relative sensitivity and specificity of cELISA comparing to VNT and the commercial ELISA kit were calculated and analyzed statistically.

Results

Virus neutralization test. Eighty-two (41.62%) out of 197 serum samples could inhibit replication of 150 TCID50 of BVDV-1 (cytopathic NADL strain) in cell culture.

Monoclonal antibody (MAbs). Among examined monoclonal antibodies, 172N was the most reactive monoclonal antibody against the purified recombinant F4 fragment of NS3 molecule. Thus, 100 mL of the supernatant of the corresponding hybridoma was harvested as the monoclonal antibody source for the development and examination of the cELISA.

Competitive ELISA. After using the checkerboard titration method, the optimum concentration of the recombinant F4 fragment as ELISA antigen and dilution of the monoclonal antibody as competitor ELISA antibody were determined as 115 ng per well and 1:300, respectively. Meanwhile, the optimum dilution of anti-mouse IgG peroxidase-conjugated was 1:5,000 dilution of this molecule in PBST.

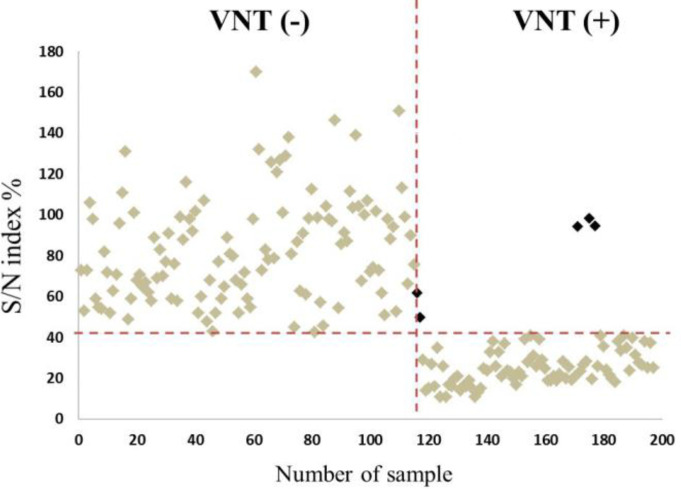

Evaluation of serum samples by cELISA. After examination of all serum samples by the cELISA the S/N index was calculated for each sample. Predictably, as there was no antibody molecule against BVDV in sera of uninfected animals, negative serum samples had the highest OD values and in contrast, positive samples showed the lowest OD values. This is clearly shown in Figure 1 where the mean S/N indexes of VNT positive and negative samples are compared to each other. On the other hand, the ROC method showed that the maximum correlation between the results of cELISA and VNT was achieved when the cut-off value of the S/N index was equal to 41.88%. As a result, serum samples with an S/N index higher than 41.88% were considered as negative serum samples and those with an S/N index less than 41.88% were considered as positive sera containing antibodies against BVDV.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of all VNT positive and negative serum samples based on their S/N index percentages. The horizontal dashed line represents the cut-off value of S/N index (= 41.88%) and divides 197 tested samples into two groups of negative (S/N index > 41.88%) and positive (S/N index < 41.88%) serum samples, while the vertical dashed line divides the examined serum samples into two groups based on their VNT results

Out of all 197 serum samples, 120 sera were negative in cELISA. However, 5 of these negative samples were found to be positive in VNT. Meanwhile, all positive serum samples in cELISA were also positive in VNT. The detailed statistical results of the cELISA, VN, and the commercial ELISA kit are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Statistics obtained from the cELISA in comparison with the results of VNT and the commercial ELISA kit

| Item | Competitive ELISA | ELISA kit | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VN | Positive | Negative | Total | Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Total | 77 | 120 | 197 | 45 | 78 | 123 | |

| Positive | 77 | 5 | 82 | 39 | 9 | 48 | |

| Negative | 0 | 115 | 115 | 6 | 69 | 75 | |

Discussion

Bovine viral diarrhea is one of the most important viral diseases of cattle which can considerably affect the yield of herds since, despite its name, it is a reproductive disease. This has necessitated many countries to begin prevention programs or to try to eradicate the disease.2,3 The first step of prevention programs is the diagnosis of the disease which determines the presence or absence of the virus infection in herds followed by detection of PI animals. Diagnosis of this disease can be done using different assays among which serological assays are the most common methods. One of these methods is antibody ELISAs which detect antibodies against BVDV infection. As NS3 is a highly conserved and immunogenic protein of BVDV different ELISAs have been developed using this antigen as ELISA detector antigen. Although it has been shown that the prokaryotically expressed recombinant NS3, as an ELISA detector antigen, has some advantages over the extract of the propagated virus in the cell culture, there are also some complications on using this recombinant protein. NS3 is relatively a large protein consisting of 683 amino acids and achieving a high amount of this protein may not be easy. Besides, a major problem is that generally recombinant NS3 is insoluble and aggregates as inclusion bodies in recombinant bacterial cells. Thus, the purification process of the recombinant NS3 needs special steps to have a good yield (e.g., treatment with urea).11-13,17 Therefore, determining the most immunogenic part of the NS3 molecule could introduce a proper substitute instead of the whole NS3 protein. This was attempted in a previous study in which it was determined that the most immunogenic domain of NS3 protein was a 122 amino-acid region (about 13.50 kDa), from residue 335 to 456, designated as the fourth fragment (F4) in that study.14 Developed ELISA with this recombinant fragment of NS3 molecule (F4-ELISA) did not show enough sensitivity and specificity compared to another ELISA with whole NS3 molecule as ELISA antigen and statistical analyses showed a medium correlation between results of F4-ELISA and virus neutralization test (κ = 0.63, p < 0.001) with relative sensitivity and specificity of 78.05% and 84.91%, respectively.14 Consequently, the present study was conducted to develop a more sensitive and specific ELISA using this immunogenic domain of NS3 molecule as a single ELISA antigen along with a monoclonal antibody in a novel cELISA. After delineating proper concentration and dilution of the antigen and antibody, all serum samples (197) were examined by this new cELISA. The results of this cELISA were compared to the results of VNT, as the gold standard method for identification of BVDV infection,16 and a commercial ELISA kit. McNemar’s test indicated that there was no significant difference between the results of cELISA and VNT (p > 0.05). Meanwhile, κ showed that there was a high correlation between the results of cELISA and VNT (κ = 0.947; p < 0.001). The relative sensitivity and specificity of cELISA with respect to VNT were 93.90% and 100%, respectively. Also, positive and negative predictive values (PPV, NPV) were 1.00 and 95.83, respectively. No significant difference was observed between the results of the commercial ELISA kit (for those 123 tested serum samples) and VNT (p > 0.05), and κ showed a lower correlation between the results of these two assays (κ = 0.74; p < 0.001) with respect to the previous comparison (κ = 0.947; p < 0.001). The relative sensitivity and specificity of the commercial ELISA kit with respect to VNT were 81.00% and 92.00%, respectively, indicating lower sensitivity and specificity compared to the present cELISA. However, there were five discrepancies between the results of cELISA and VNT. These serum samples were negative in cELISA and they were found to be positive in VNT. This was probably because of 1) different epitope recognition of the monoclonal antibody with respect to antibody molecules in sera of those infected animals which means that there was not any competition between these two to bind to the antigen or, 2) unspecific inhibition of viral replication due to presence of inhibitor materials in those false-negative serum samples in cELISA.

The results of the present study were in agreement with previous studies. Lecomte et al. cloned the DNA coding region of the 80.00 kDa antigen of BVDV/Osloss virus strain and successfully used the purified recombinant protein for ELISA detection of BVDV specific antibodies in a competitive ELISA using MAbs. It was shown that this competitive ELISA was more specific than a direct assay.11 In another study performed by Reddy et al., a 917-bp segment of NS3 (BVDV-NADL vaccine strain) was cloned into a pGex-2T plasmid vector contained the glutathione-S-transferase (GST) gene followed by the expression in E. coli. The recombinant protein was then used in ELISA to detect BVDV infection by testing 54 independent bovine serum samples. Statistical analysis showed a high degree of correlation between the reactivity of the recombinant protein and natural antigens in ELISA and also between the results of the ELISA and VNT.13 Chimeno and Tobaga, using eukaryotically, expressed most immunogenic proteins (E0, E2, and NS3) of BVDV (NADL strain) to design ELISAs for the detection of specific antibodies in cattle sera. The results showed that designed ELISAs were highly sensitive and specific in comparison with VNT.7 Bhatia et al. developed a competitive inhibition ELISA (CI-ELISA) for detection of antibodies against BVDV using the prokaryotically, and expressed helicase domain of NS3 protein, two-thirds of NS3 protein from C-terminus (45.00 kDa) and a monoclonal antibody, and compared their results with results obtained from two commercial ELISA kits. 914 field serum samples of cattle (810) and buffaloes (104) were tested by this CI-ELISA and the results showed a relative specificity of 95.75% and 97.38% and sensitivity of 96.00% and 94.43% in comparison with the Ingenesa kit and Institut Pourquier kit, respectively. This study proved that the use of the helicase domain of NS3 was equally good as the whole NS3 protein (80.00 kDa) used in commercial kits for the detection of BVDV antibodies in cattle and buffaloes. However, the results of this CI-ELISA were not directly compared to VNT as the gold standard method for diagnosis of BVD.18

The results of the present study showed that this newly designed cELISA had high sensitivity and specificity for the detection of antibodies against BVDV. On the other hand, as NS3 was highly conserved among Pestiviruses and the developed ELISA was a competitive one, and it could potentially be applied to detect BVDV infection not only in cattle but also in other domestic and wildlife species. However, it has yet to be examined. Design and development of such new ELISA assays which are more sensitive and specific can provide valuable diagnostic tools to detect BVDV infections followed by prevention, control and even eradication of the disease.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by research grants from the Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Ahvaz, Iran.

References

- 1.Baker JC. The clinical manifestations of bovine viral diarrhea infection. Vet Clin North Am: Food Anim Pract. 1995;11(3):425–445. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0720(15)30460-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greiser-Wilke I, Grummer B, Moennig V. Bovine viral diarrhea eradication and control programmes in Europe. Biologicals. 2003;31(2):113–118. doi: 10.1016/s1045-1056(03)00025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Presi P, Heim D. BVD eradication in Switzerland--a new approach. Vet Microbiol. 2010;142(1-2):137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collett MS, Wiskerchen M, Welniak E, et al. Bovine viral diarrhea virus genomic organization. Arch Virol Suppl. 1991;3:19–27. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9153-8_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorbalenya AE, Koonin EV, Donchenko AP, et al. Two related superfamilies of putative helicases involved in replication, recombination, repair and expression of DNA and RNA genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17(12):4713–4730. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.12.4713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiskerchen M, Collett MS. Pestivirus gene expression: protein p80 of bovine viral diarrhea virus is a proteinase involved in polyprotein processing. Virology. 1991;184(1):341–350. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90850-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chimeno Zoth S, Taboga O. Multiple recombinant ELISA for the detection of bovine viral diarrhoea virus antibodies in cattle sera. J Virol Methods. 2006;138(1-2):99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolin SR, Ridpath JF. Specificity of neutralizing and precipitating antibodies induced in healthy calves by monovalent modified-live bovine viral diarrhea virus vaccines. Am J Vet Res. 1989;50(6):817–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donis RO, Corapi WV, Dubovi EJ. Bovine viral diarrhea virus proteins and their antigenic analyses. Arch Virol Suppl. 1991;3:29–40. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9153-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandvik T. Laboratory diagnostic investigations for bovine viral diarrhoea virus infections in cattle. Vet Microbiol. 1999;64(2-3):123–134. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(98)00264-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lecomte C, Pin JJ, De Moerlooze L, et al. ELISA detection of bovine viral diarrhoea virus specific antibodies using recombinant antigen and monoclonal antibodies. Vet Microbiol. 1990;23(1-4):193–201. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(90)90149-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanderheijden N, De Moerlooze L, Vandenbergh D, et al. Expression of the bovine viral diarrhea virus Osloss p80 protein: its use as ELISA antigen for cattle serum antibody detection. J Gen Virol. 1993;74(Pt 7):1427–1431. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-7-1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy JR, Kwang J, Okwumabua O, et al. Application of recombinant bovine viral diarrhea virus proteins in the diagnosis of bovine viral diarrhea infection in cattle. Vet Microbiol. 1997;57(2-3):119–133. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(97)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahmoodi P, Shapouri MR, Ghorbanpour M, et al. Epitope mapping of bovine viral diarrhea virus nonstructural protein 3. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2014;161(3-4):232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) Manual of diagnostic tests and vaccines for terrestrial animals 2021, Chapter 3.4.7. [Accessed July 11, 2022]. Available at: https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/3.04.07_BVD.pdf.

- 16.Edwards S. The diagnosis of bovine virus diarrhea-mucosal disease in cattle. Rev Sci Tech. 1990;9(1):115–130. doi: 10.20506/rst.9.1.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deregt D, Dubovi EJ, Jolley ME, et al. Mapping of two antigenic domains on the NS3 protein of the pestivirus bovine viral diarrhea virus. Vet Microbiol. 2005;108(1-2):13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatia S, Sood R, Mishra N, et al. Development and evaluation of a MAb based competitive-ELISA using helicase domain of NS3 protein for sero-diagnosis of bovine viral diarrhea in cattle and buffaloes. Res Vet Sci. 2008;85(1):39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]