Abstract

Structural studies of membrane proteins in native-like environments require the development of diverse membrane mimetics. Currently there is a need for nanodiscs formed with non-ionic belt molecules to avoid non-physiological electrostatic interactions between the membrane system and protein of interest. Here, we describe the formation of lipid nanodiscs from the phospholipid DMPC and a class of non-ionic glycoside natural products called saponins. The morphology, surface characteristics, and magnetic alignment properties of the saponin nanodiscs were characterized by light scattering and solid-state NMR experiments. We determined that preparing nanodiscs with high saponin:lipid ratios reduced their size, diminished their ability to spontaneously align in a magnetic field, and favored insertion of individual saponin molecules in the lipid bilayer surface. Further, purification of saponin nanodiscs allowed flipping of the orientation of aligned nanodiscs by 90°. Finally, we found that aligned saponin nanodiscs provide a sufficient alignment medium to allow the measurement of residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) in aqueous cytochrome c.

Keywords: Nanodisc, Saponin, Membrane protein, NMR, Residual Dipolar Couplings

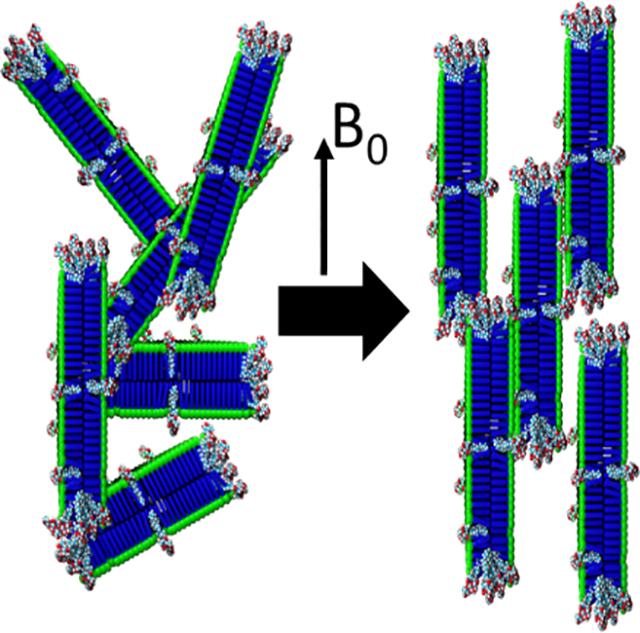

Graphical Abstract

Membrane proteins comprise more than half of all known targets for approved drugs.1,2 However, crystallization of membrane proteins is notoriously difficult and so they are vastly underrepresented in available high-resolution structures.3,4 Even when crystallographic techniques have afforded atomic-resolution structures of membrane proteins, the conditions required for crystallization are non-native, so there is uncertainty that these structures are physiologically relevant. Cryo-EM similarly requires fixation of samples in non-native environments and struggles to resolve high resolution structures of low molecular weight proteins. On the other hand, NMR offers an alternative approach to determine high-resolution structures in native-like conditions and is additionally able to probe dynamics and conformational ensembles. To reproduce native membrane conditions for NMR experiments, a broad selection of membrane mimetics is necessary to accommodate the structural and functional diversity of membrane proteins.5 For example, discoidal lipid bilayers, called nanodiscs or bicelles, have emerged as exciting systems to replicate a cell membrane environment for reconstitution of membrane proteins.6,7 Their flat surfaces model the cell membrane surface better than highly curved vesicles or micelles, and their optical transparency allows their use in a wide variety of biophysical and spectroscopic techniques. Additionally, because many nanodisc systems can be spontaneously aligned in a magnetic field, they enable the measurement of residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) by solution NMR experiments for structural characterizations of biomolecules, such as membrane and soluble proteins and nucleic acids.8–10

Nanodiscs are structurally characterized as flat, discoidal lipid bilayers encircled by an amphiphilic belt molecule. The first reported synthetic nanodisc was constructed from a membrane scaffold protein (MSP) belt and there are now a wide variety of peptides, synthetic polymers, and detergents reported to act as nanodisc belts.11–13 It is important to carefully select an appropriate belt that maintains native structure, dynamics, and function for protein structural studies. For example, electrostatic interactions due to highly-charged belts have been reported to disrupt functional reconstitution of membrane proteins.14,15 As such, there is considerable interest in the development of uncharged belt molecules to study complexes of oppositely charged proteins like the REDOX complexes. But there is a general lack of belt molecules with net neutral charges, and most of those that exist are zwitterionic detergents, such as DHPC and DPS, which are known to denature some membrane and solution-phase proteins.16–18 Non-ionic surfactants are also uncharged and have been shown to be less perturbative to membrane protein structure than charged and zwitterionic surfactants and as such are attractive targets to find non-ionic, non-denaturing belt molecules.16

Here, we identify saponins as a particularly interesting class of non-ionic amphiphilic molecules. Structurally, they are defined by a steroid or triterpenoid hydrophobic aglycone core bound to one or more sugar moieties. As natural products, saponins have been extensively studied for biomedical applications.19 Of note, saponins have been shown to enhance immune system response and to improve bioavailability of small molecules as components of nanoparticles for drug delivery.20–22 Consequently, several vaccines include saponin-based adjuvants, including a vaccine for Covid-19 recently developed by Novavax.23 Several saponins also show anti-cancer activity and are under study as potential therapeutics.24 Other applications of saponins include as agricultural soil and wastewater treatment, as food additives, and as cosmetics.25,26 However, the tendency of saponins to induce haemolysis limits their broad use in biological applications.27 This ability to lyse cell membranes emphasizes the general benefit of investigating saponin-lipid interactions. Recently, the saponin β-aescin has been shown to form nanodisc-like lipid nanoparticles with the phospholipid 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC).28–30 However, despite such great potential for saponin-based lipid membrane systems, very few studies of saponin-lipid interactions exist in the literature. Here, we employ static solid-state NMR experiments to thoroughly characterize lipid bilayers formed from DMPC and a heterogeneous mixture of saponins extracted from Quillaja Molina trees (Sigma 84510, Sigma-Aldrich). Our results suggest that saponin forms discoidal lipid bilayers which are able to align in the presence of an external magnetic field.

Approximately 100 structurally distinct Quillaja-derived saponin molecules have been described.25 Typically, they contain the hydrophobic triterpene quillaic acid attached to two sugar moieties which vary in their monosaccharide compositions. Quillaja saponins generally have a single carboxylic acid group with a pKa above 6 and which provides a single possible charge. To gain an understanding of the saponin structures present in this mixture of Quillaja saponins, we performed 2D 1H-13C HSQC and 13C-DEPT solution-state NMR experiments (Figure S1). The 13C NMR spectra showed strong signal in the chemical shift region from 60–80 ppm, and the 2D HSQC spectrum showed correlations between these peaks and 1H nuclei with chemical shifts in the range 3–4.5 ppm. Two strong peaks also appeared in the 13C NMR spectra near 115 and 135 ppm. The strong overlapping signals in the 13C and 2D HSQC NMR spectra are consistent with carbohydrate moieties, and the two strong 13C peaks above 100 ppm are consistent with the alkene carbon atoms of a saponin aglycone.31 Other signal arising from the saponin aglycone would be expected to appear below 40 ppm in the 13C NMR spectra and below 2 ppm in the 1H NMR spectrum. However, our spectra showed very few peaks in these regions. These results are consistent with saponin structures with high carbohydrate content, such as the Quillaja saponin QS-21.32 Although this structure has several carbonyl groups and the 1D 13C NMR spectra did not show clear carbonyl peaks, there is a cross-peak in the 2D HSQC spectrum which correlates a 1H chemical shift of 8.35 ppm with a 13C chemical shift of 170.8 ppm, consistent with an aldehyde group.

When saponin was added to aqueous DMPC liposomes in a DMPC:saponin mass ratio greater than 1:0.5, the solution went from milky white and opaque to transparent, which indicated the formation of smaller lipid nanoparticles. Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images showed primarily discoidal particles with diameters around 20 nm (Figure S2). The presence of larger structures in the images suggested a high degree of polydispersity in the saponin nanodiscs compared to other nanodisc systems. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was also used to characterize the size distributions of these nanoparticles (Figure S3) formed at different saponin mass ratios. Nanodiscs formed under each condition showed multimodal light scattering, consistent with the small and large particles in the TEM images. We attributed the small radius peak (~10 nm) to nanodiscs and the large radius peak (>100 nm) to structures formed from fused and stacked nanodiscs. The nanodisc size distribution depended on the saponin mass fraction, with more saponin (relative to DMPC) leading to smaller and more polydisperse nanodiscs. Though the observed change in size is small, these results suggest that saponin allows the design of size-tunable nanodiscs. This is consistent with observations of nanodiscs formed from other belt molecules.12,15

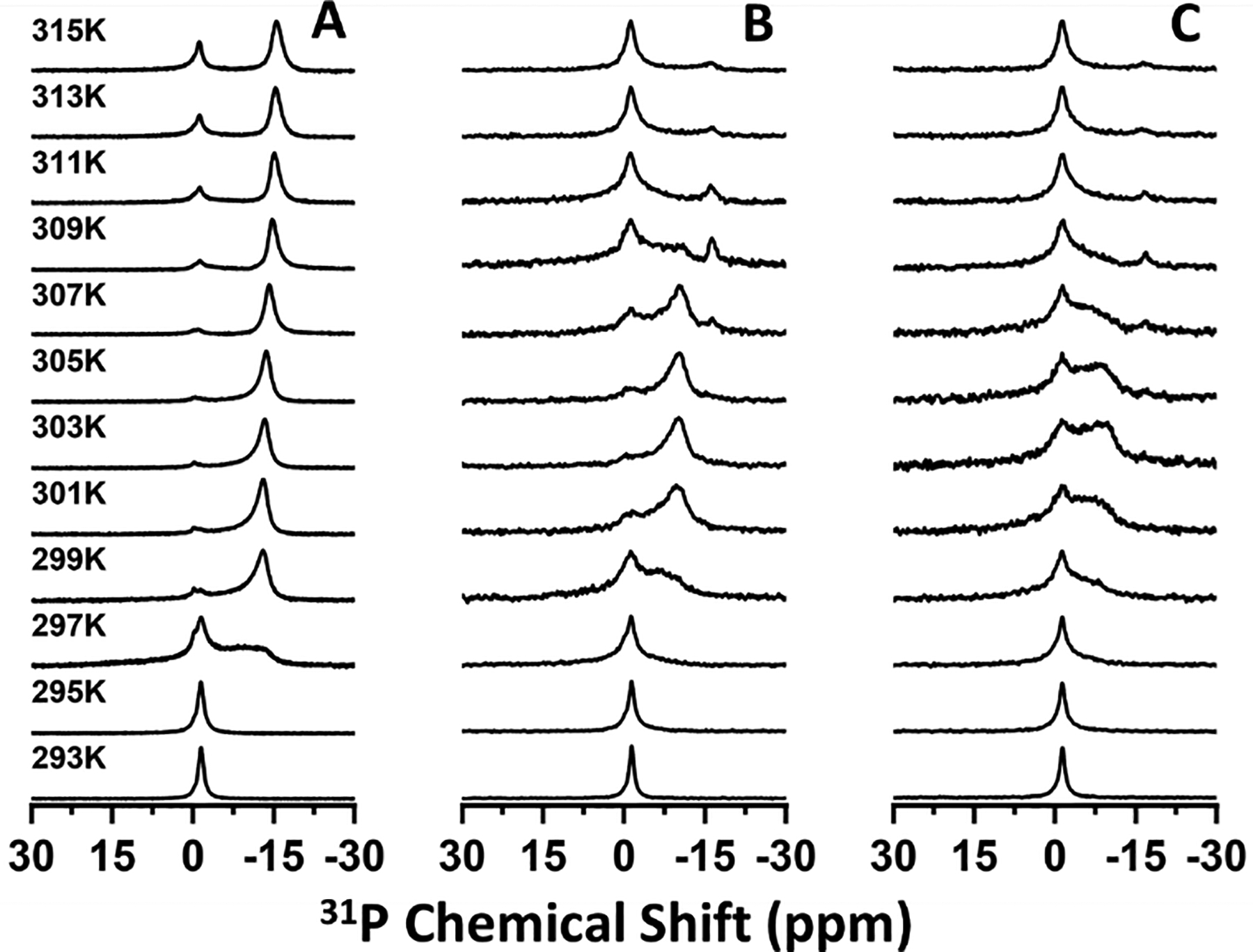

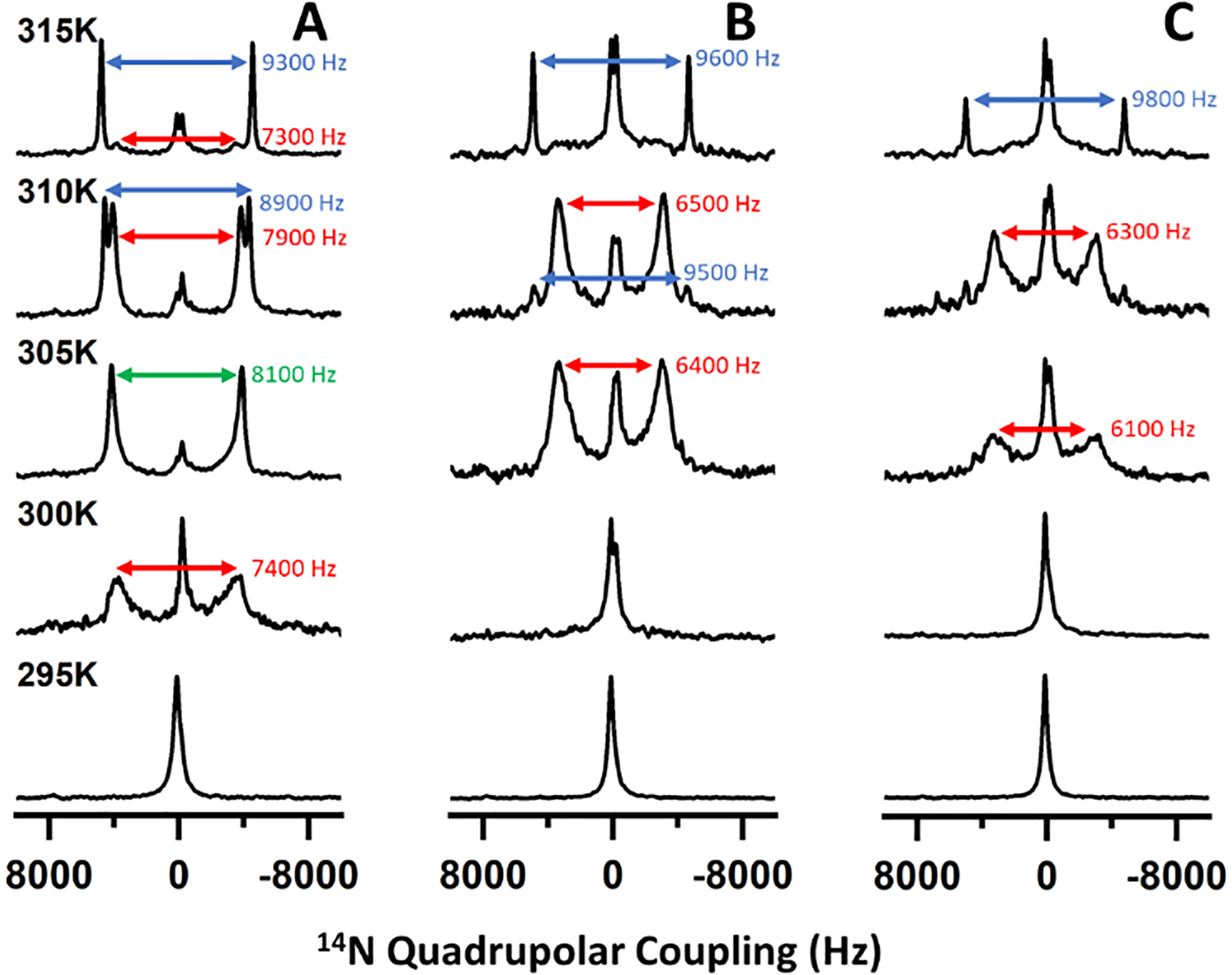

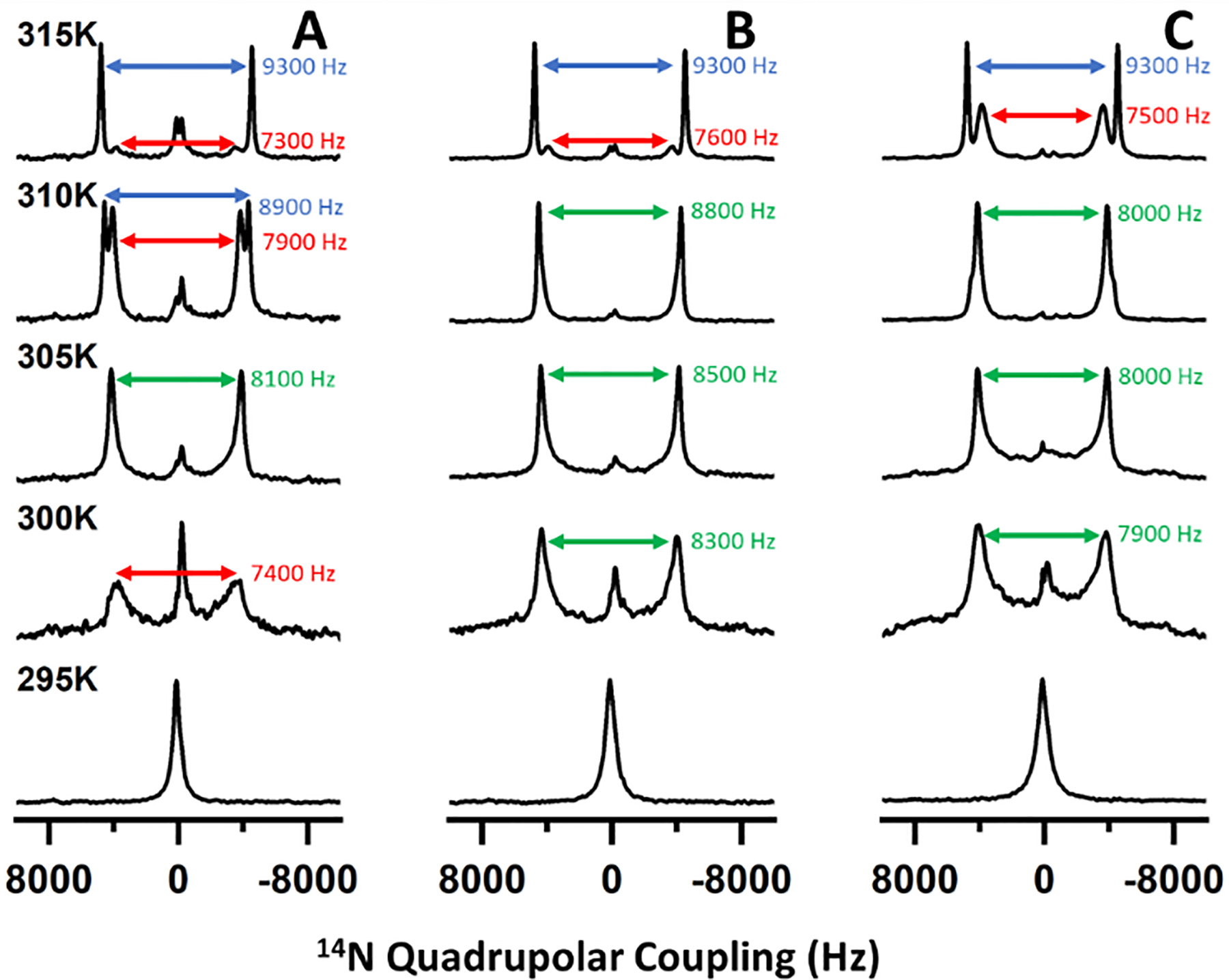

We then performed temperature-dependent 31P (Figure 1) and 14N (Figure 2) solid-state NMR experiments under static conditions to assess the magnetic alignment properties of nanodiscs formed with different DMPC:saponin mass ratios. At 293 K, a single peak appeared near −1 ppm (referenced to H3PO4) in the 31P NMR. As the temperature increased, this peak broadened to resemble a combination of the −1 ppm peak and a motionally averaged powder pattern spanning from 22 to −20 ppm (Figure 1A). When the temperature rose above the main phase transition temperature (Tm ~297 K) of DMPC, a single dominant peak appeared around −15 ppm. Above 307 K, the −1 ppm peak reappeared and increased in intensity relative to the peak near −15 ppm. The 14N NMR spectra also showed a temperature-dependent behavior (Figure 2). A single peak appeared at low temperature and split into two peaks at higher temperatures.

Figure 1.

Temperature-dependent 31P NMR spectra of saponin nanodiscs with DMPC:Saponin mass ratios of 1:0.5 (A), 1:0.75 (B), and 1:1 (C).

Figure 2.

Temperature-dependent 14N NMR spectra of saponin nanodiscs with DMPC:saponin mass ratios of 1:0.5 (A), 1:0.75 (B), and 1:1 (C). Quadrupolar coupling values are presented from saponin-rich (red), saponin-poor (blue), and ambiguous or averaged lipid domains (green).

The 31P chemical shift and 14N quadrupolar coupling both report on the orientation of the lipid headgroup with respect to the external magnetic field direction. It has previously been shown that in magnetically aligned lipid nanodiscs, structural anisotropy causes the DMPC 31P chemical shift to move from −1 ppm to −15 ppm as the nanodiscs align with their bilayer normal oriented perpendicularly to the magnetic field axis. Similarly, anisotropy in the aligned state causes quadrupolar coupling to be observed in 14N NMR spectra of DMPC-containing nanodiscs while no coupling is observed in isotropic lipid systems. In the 31P NMR spectra presented here, the peak near 0 ppm arose from isotropically tumbling nanodiscs, indicating that at low temperature the nanodiscs were unaligned. As the temperature increased above the Tm of DMPC, the appearance of the peak near −15 ppm demonstrated the spontaneous alignment of nanodiscs with their bilayer normal oriented perpendicular to the magnetic field direction. The combination of isotropic and aligned peaks at high temperature is consistent with phase separation of a population of DMPC vesicles or small micellar saponin-DMPC structures which have been described previously for mixtures of DMPC and β-aescin.30

Our results also show that nanodiscs with higher mass fractions of saponin possessed a diminished ability to align in the magnetic field. While the 31P NMR spectra of 1:0.5 DMPC:saponin w/w nanodiscs showed prominent aligned peaks from 299 K to at least 315 K, those from 1:0.75 nanodiscs showed prominent aligned peaks in a narrower temperature range from 301 K to 307 K, and the spectra from 1:1 nanodiscs did not clearly resolv an aligned peak. The 14N spectra presented quadrupolar couplings which depended on the extent of alignment and showed the same trends observed in the 31P NMR spectra, with no coupling for isotropic nanodiscs and couplings around 9.3 kHz for aligned nanodiscs. Previous studies of polymer, peptide, detergent, and β-aescin nanodiscs found that increasing the mass/molar fraction of the belt molecule led to the formation of smaller nanodiscs and that larger nanodiscs have a greater capacity for magnetic alignment.5,12 Because the alignment of a nanodisc arises from the total magnetic susceptibility anisotropy of the lipids comprising the nanodisc, the torque exerted on small nanodiscs by the magnetic field is less than that exerted on larger nanodiscs and less capable of overcoming isotropic tumbling motions. By DLS, the saponin nanodiscs also showed a size dependence on the saponin mass fraction (Figure S3), so it could be expected that the larger saponin nanodiscs would exhibit greater magnetic alignment.33–35 It is also possible that the greater size polydispersity at high saponin mass fraction interfered with homogeneous alignment in the magnetic field. Thus, our results are consistent with saponin forming size-tunable nanodiscs which have variable ability to align in a magnetic field.

Saponin nanodiscs with higher saponin mass ratios also displayed additional 31P NMR peaks with a chemical shift between −1 and −15 ppm and 14N quadrupolar couplings smaller than 9300 Hz. Because both the 31P chemical shift and 14N quadrupolar coupling depended on the orientation of the lipid head group with respect to the magnetic field, intermediate shifts and couplings indicated lipid orientations which are not exactly perpendicular to the magnetic field axis. This could have resulted from saponin molecules that inserted in the bilayer surface and caused the surrounding lipid molecules to tilt away from parallel to the bilayer normal. SAXS studies suggested this occurred in β-aescin bicelles.28,30 DSC-based studies of β-aescin inserted in lipid membranes showed two distinct melting temperatures which the authors also attributed to saponin-rich and saponin-poor domains.36 Tilted lipid molecules near the rim of the nanodiscs might also have contributed to the signal we attributed to saponin-rich domains but would not be a full explanation. Our results are therefore consistent with insertion of saponin into the bilayer surface, forming saponin-rich and saponin-poor domains, with the extent of surface insertion determined by saponin mass fraction.

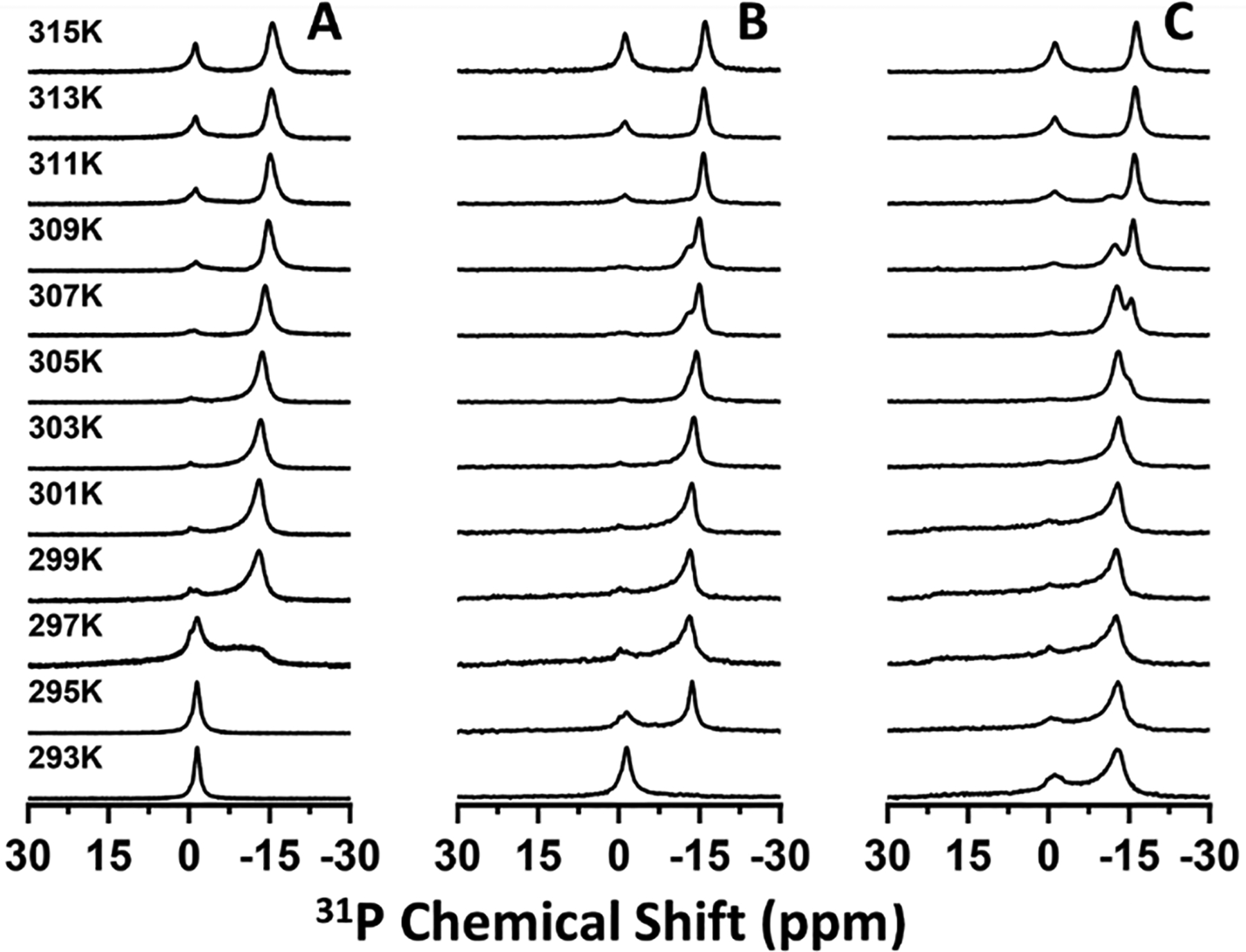

We also collected 31P (Figure 3) and 14N (Figure 4) NMR spectra of saponin nanodiscs at various nanodisc concentrations. Both sets of spectra demonstrated that increasing the concentration extended the temperature range in which magnetic alignment occurred. The 31P NMR spectra also showed saponin-rich aligned peaks at low temperature and high concentration but saponin-poor aligned peaks at high temperature and low concentration. Below 315 K, the 14N NMR spectra did not resolve the saponin-rich peaks clearly for high nanodisc concentrations (Figure 4B,C), in contrast to the 31P NMR spectra. It is possible that because the observed quadrupolar couplings at 310 K for 15% and 25% w/w nanodiscs were only slightly smaller than the saponin-poor couplings, the data indicate more restricted motion of the phosphate portion of the DMPC headgroup than the choline group in these samples. Still, these results are consistent with a temperature-dependent equilibrium between aqueous micellar and bilayer-inserted saponin. Increasing the temperature pushed the equilibrium towards the aqueous micellar phase and increasing the nanodisc concentration effectively decreased the amount of water which pushed the equilibrium towards the bilayer-inserted phase.

Figure 3.

Temperature-dependent 31P NMR spectra of saponin nanodiscs with lipid/water mass ratios of 10% (A), 15% (B), and 25% (C) w/w.

Figure 4.

Temperature-dependent 14N NMR spectra of saponin nanodiscs with lipid/water mass ratios of 10% (A), 15% (B), and 25% (C) w/w. Quadrupolar coupling values are presented from saponin-rich (red), saponin-poor (blue), and ambiguous or averaged lipid domains (green).

For protein structural studies, saponin not associated with the belt could be undesirable due to potential protein-saponin interactions on the bilayer surface. Therefore, size exclusion chromatography (SEC) was used to remove saponin in the aqueous phase and loosely bound to the lipid surface. The SEC profile and 1H NMR spectra of the low mass SEC peak showed clear separation of low molecular weight (MW) saponin micelles and free molecules from high MW nanodiscs (Figure S4). Consistent with removal of saponin molecules from the bilayer surface, comparison of 31P NMR spectra also showed narrower lineshapes for the purified nanodiscs (Figures S5 and S6). As an additional note, while unpurified nanodiscs were stable for at least one month at 4 °C and after repeated heating cycles, purified nanodiscs did not remain stable for more than a week at 4 °C or for repeated heating cycles, likely due to the absence of excess saponin to drive the reformation of disrupted nanodiscs.

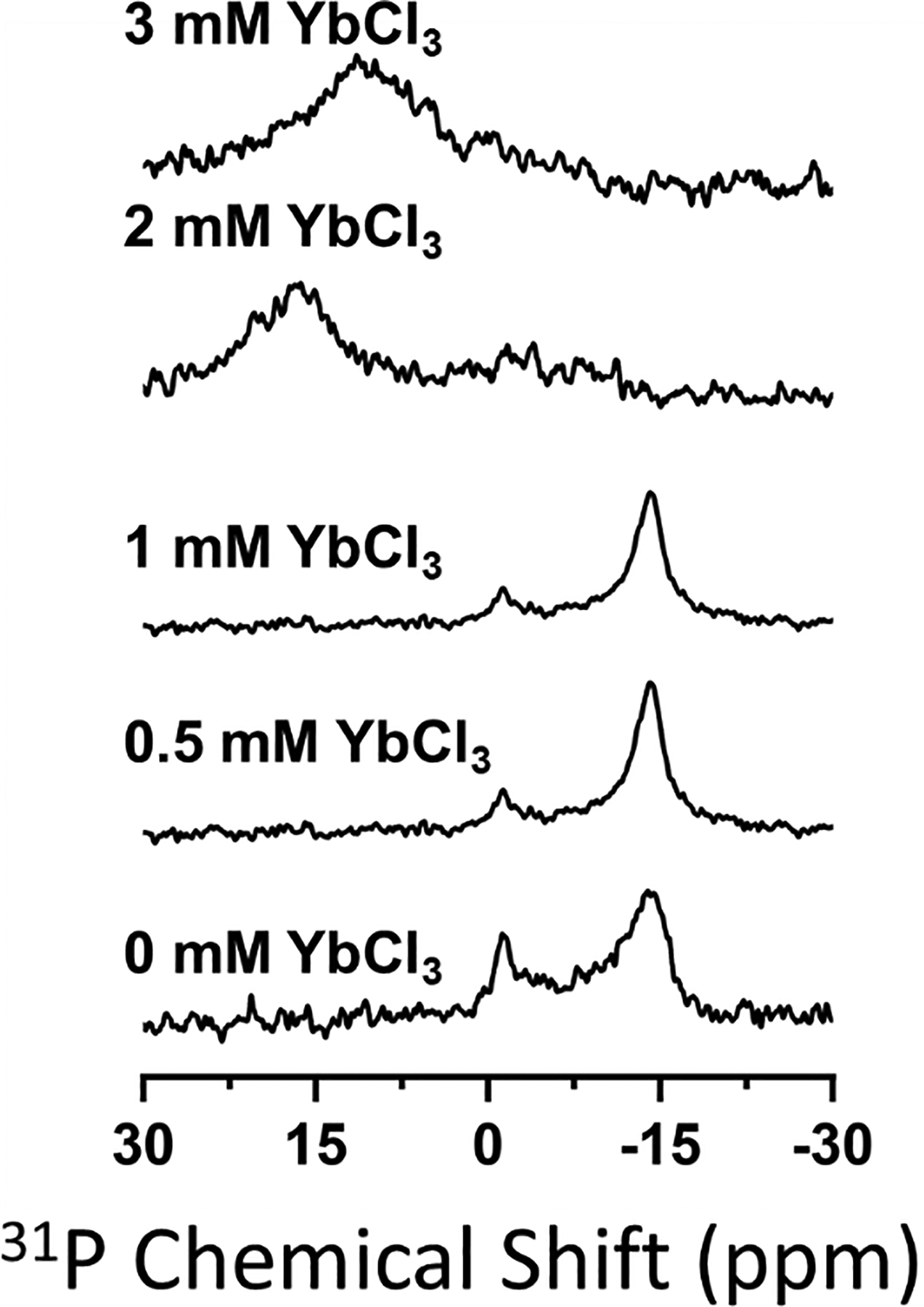

Addition of paramagnetic lanthanide ions that have a positive magnetic susceptibility anisotropy can flip the magnetic alignment of nanodiscs by 90°.34,37 Nanodiscs aligned with their bilayer normal parallel rather than perpendicular to the magnetic field provide higher spectral resolution for molecules which do not undergo fast axially symmetric motion.34 There is also no concern that proteins with transmembrane helices (which have a positive magnetic susceptibility anisotropy) will disrupt a parallel alignment. To determine if saponin nanodiscs can adopt a flipped orientation, we titrated samples with Yb3+ ions. Titration up to 8 mM YbCl3 did not flip the orientation of unpurified saponin nanodiscs (Figure S7). For reference, the orientations of polymer nanodiscs and DHPC bicelles undergo a 90° flip at less than 2 mM YbCl3.34,37 However, we also did not observe the paramagnetic broadening of 31P spectral lines one would expect upon binding of Yb3+ to the lipids. We hypothesized that free saponin molecules present in the aqueous phase chelated the added Yb3+ metal ions, preventing them from binding to lipids in the nanodiscs. Accordingly, when we titrated purified nanodiscs (which do not have excess aqueous saponin) with YbCl3, the orientation flipped at 2 mM Yb3+ (Figure 5). We observed that titration of YbCl3 also affected the 31P chemical shift; addition of the lanthanide ions shifted the aligned peak low-field and the flipped peak high-field. To understand the opposite effects of the metal ions on each peak, we added YbCl3 to DMPC MLVs. Upon addition of the metal ions, the span of the DMPC 31P powder pattern decreased and the lineshape was distorted (Figure S8). A metal-induced contraction of the DMPC 31P CSA tensor span would explain the observed changes in the 31P chemical shifts in Figure 5, but further research is needed to fully understand this effect.

Figure 5.

31P NMR spectra of purified 1:0.5, 10% w/w DMPC:saponin nanodiscs titrated with YbCl3. Spectra with the full spectral width are included in the supporting information (Figure S7).

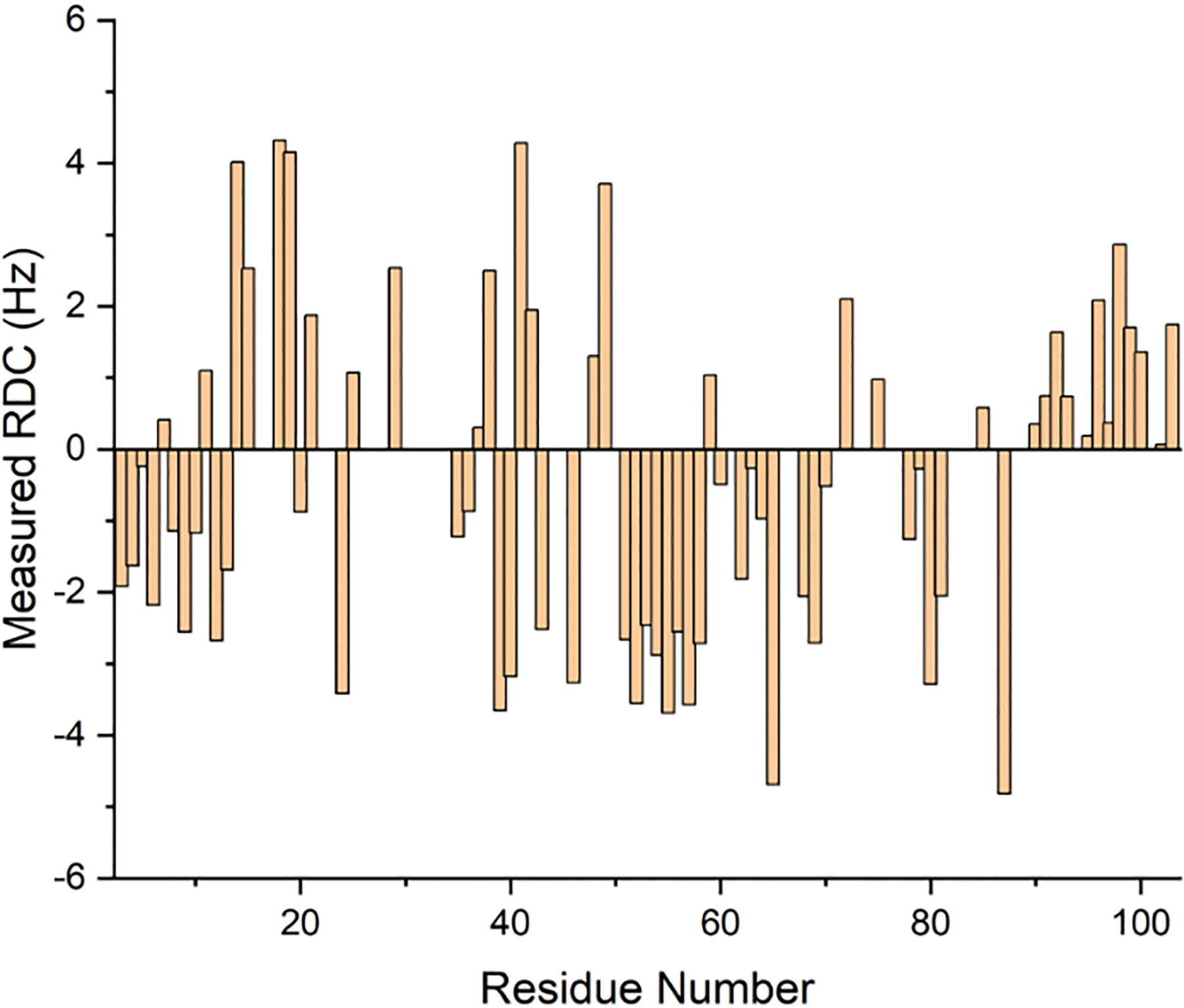

To demonstrate the utility of saponin nanodiscs for protein structural studies, we used purified saponin nanodiscs as an alignment medium for the measurement of RDCs from 15N-labelled cytochrome c. We performed 2D 1H-15N in-phase anti-phase HSQC (IPAP-HSQC) at 32° C to measure NH (scalar ± dipolar) coupling values (Figure 6) in an anisotropic saponin nanodisc-based alignment medium. These couplings were compared to previously-measured cytochrome c isotropic JNH couplings to determine the RDCs. At a lipid concentration of 70 mg/mL we were able to measure ±6 Hz RDCs which is comparable to RDCs measured previously using peptide nanodiscs.9 To validate the structure of the protein in our sample, we compared our experimentally measured RDCs to those calculated from several structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Correlation R values were obtained from each structure and ranged from 0.78 to 0.85 for high-resolution crystal structures (Figure S9, Table S1). For comparison, cytochrome c RDCs measured using polymer nanodiscs rendered R values greater than 0.95 for the same structures.8 It is likely that higher polydispersity in the saponin nanodiscs resulted in a lower order parameter than that of the polymer nanodiscs and that this lower order parameter caused the measured RDCs to be of a smaller magnitude. The lower correlations then stemmed from RDCs which were small relative to 15N spectral linewidths.

Figure 6.

Experimentally measured RDCs of cytochrome c with purified 1:0.5, 7% w/w DMPC:saponin nanodiscs.

These results demonstrate that, with appropriate sample optimization, saponin nanodiscs can act as an alignment medium to enable protein structural studies by solution NMR. While this point implicitly assumes that saponins are non-perturbative to native protein structure, there is evidence to believe this is the case. A Quillaja saponin extract was shown to have no effect on the secondary structure of bovine serum albumin (BSA) and several individual saponin molecules have shown an ability to protect BSA against heat denaturation.38–40 Therefore, non-ionic nanodiscs such as these will be an essential tool to study proteins for which electrostatic interactions with a highly charged polymer or peptide belt or a zwitterionic detergent belt are prohibitively perturbative to the native structure.

In conclusion, we have characterized the magnetic alignment properties and surface characteristics of nanodiscs formed from DMPC and a mixture of naturally extracted saponins. Depending on the concentration and DMPC:saponin mass ratio, the nanodiscs spontaneously align in a magnetic field within the temperature range 295–315 K. Free and bilayer surface-inserted saponin molecules can be removed by size-based filtration which also enables the nanodisc alignment to flip 90° upon addition of paramagnetic lanthanide ions. We further showed that aligned saponin nanodiscs act as an anisotropic alignment medium to allow the measurement of RDCs of water-soluble cytochrome c.

It is remarkable that a heterogeneous mixture of naturally extracted saponin molecules forms size-tunable nanodiscs that align in a magnetic field. Careful selection and design of individual, structurally diverse saponin molecules should allow the development of an entire class of membrane systems with desired properties such as tunable size, magnetic alignment properties, surface characteristics, lipid compositions, protection against structural denaturation, and tolerance to pH and divalent cations. Because saponins are generally non-ionic, such tailored nanodiscs would not only be suitable for functional reconstitution of both positively and negatively charged proteins and protein complexes with other biomolecules for biophysical and functional studies. X-ray crystallography and Cryo-EM studies would also benefit from the use saponin nanodisc technology to study lipid membrane systems. Further, the biological activity of many saponins and their successful implementation in vaccines inspires the investigation of saponin nanodiscs as nontoxic and biologically-degradable nanoparticle drug delivery platforms.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Materials.

1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc. Saponin (Product No. 84510), Ytterbium trichloride hexahydrate (YbCl3), sodium chloride, and Tris were purchased from Sigma Aldrich USA. Uniformly 15N-labelled equine cytochrome c was expressed and purified as described previously.41

Preparation of Saponin Nanodiscs.

Stocks of DMPC (200 mg/mL) and Saponin (200 mg/mL) were prepared by weighing and dissolving powder in an appropriate volume of buffer (10 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl). The DMPC stock solution was subjected to 3–5 freeze-thaw cycles before addition of saponin. DMPC and saponin were mixed to achieve several mass ratios. The resulting solution was subjected to 3–5 more freeze-thaw cycles.

Purified samples were passed through size-based filters, either a size exclusion chromatography (SEC) column or a 100k MWCO ultracentrifugation filter (Amicon). SEC filtration was performed on an AKTA FPLC system (GE Healthcare) equipped with a Superdex column and fraction collector. The sample was diluted to 10 mg/mL lipids and loaded on a 5 mL loop. Nanodiscs were eluted using the same buffer with a flow rate of 3 mL/min. Eluate was monitored by absorbance at 214 nm. Fractions corresponding to each peak were analyzed by 1H NMR to confirm separation of saponin from nanodiscs. Nanodisc-containing fractions were collected and concentrated by spinning 30K MWCO Amicon centrifugal filters at 4000 × g for 1–2 hr.

Flipped samples were prepared as above and titrated with YbCl3 from a 100 mM stock in H2O.

Transmission Electron Microscopy.

Saponin nanodiscs were prepared as above with 1:0.5 DMPC:Saponin and 100 mg/mL lipids. The nanodiscs were then diluted to 0.5 mg/mL and stained with 1% uranyl acetate on a glow discharged copper grid. Images were taken with a JEOL JEM 1400 Plus TEM.

Dynamic Light Scattering.

Samples for DLS were prepared as above and diluted to 5 mg/mL DMPC. Measurements were made at 298 K with a DynaPro Nanostar instrument (Wyatt Technology) and a 1 μL quartz microcuvette.

Solution NMR Experiments.

Saponin was dissolved in buffer and 10% D2O to 50 mg/mL. 1H-13C HSQC and 13C-DEPT experiments were performed on this sample using an 800 MHz Bruker NMR spectrometer. HSQC spectra were acquired with 2048 t2*512 t1 points, 8 scans, a 2 s recycle delay, and 10.5 and 12 μs 90° pulse widths for 1H and 13C respectively. DEPT spectra were acquired with 256 scans, a 2 s recycle delay, and a 12 μs 13C 90° pulse.

31P NMR Experiments.

31P NMR experiments were performed on a 400 MHz Bruker solid-state NMR spectrometer. Spectra were acquired under static conditions using 5 mm double- and triple-resonance HX and HXY MAS probes (Chemagnetics/Agilent Ltd) tuned to resonance frequencies of 161.97 MHz for 31P nuclei and 400.11 MHz for 1H nuclei. The acquisition parameters were a 5 μs 90° pulse (80 W), a 3.0 s recycle delay, and 20 W spinal64 proton decoupling.42 Signal was averaged over 512 scans and 31P chemical shifts were referenced by setting the chemical shift of liquid H3PO4 to 0 ppm. Data was processed using 20 Hz line broadening. In temperature-dependent experiments, the sample was allowed to equilibrate for one hour at each temperature.

14N NMR Experiments.

14N NMR experiments were performed on a 400 MHz Bruker solid-state NMR spectrometer. Spectra were acquired under static conditions using a 5 mm double-resonance HX MAS probe (Chemagnetics) with the X-channel tuned to the 14N resonance frequency 28.92 MHz. A 90–90 solid echo pulse sequence was used with an 8 μs 90° pulse (130 W), a 120 μs echo delay, a 200 ms recycle delay, and no proton decoupling.43 Signal was averaged over 30720 scans and data was processed using 100 Hz line broadening. In temperature-dependent experiments, the sample was allowed to equilibrate for 30 minutes at each temperature.

Measurement of Cytochrome C RDCs.

Powdered 15N-labelled cytochrome c was dissolved to 700 μM in a 10 mM Tris, 50 mM NaCl buffer. Protein concentration was determined by absorbance at 410 nm assuming a molar extinction coefficient of 106 mM−1 cm−1. Saponin nanodiscs were prepared with 2:1 DMPC:saponin by mass and purified as detailed above. Nanodiscs were added to the dissolved cytochrome c to achieve a final protein concentration of 200 μM and a final lipid concentration of 70 mg/mL. D2O was also added to 10% for locking.

RDCs were measured from 1H-15N IPAP-HSQC spectra collected with an 800 MHz Bruker NMR spectrometer and a 5 mm triple resonance TCI cryoprobe. The acquisition parameters were 2048 t2*400 t1 points, 16 scans, a 1.2 s recycle delay, and 9.8 and 32 μs 90° pulse widths for 1H and 15N respectively. The spectrum was processed using the splitipap2 macro in topspin and the resulting IP and AP spectra were exported to Sparky.44 Peaks were assigned as previously.45 Ambiguously assigned peaks and peaks with S/N ratio below 10 were excluded from further analysis. RDCs were calculated by finding the difference between anisotropic and isotropic J-coupling values. To compare measured RDCs to previously published structures, structural coordinates were taken from the RCSB protein data bank (PDB)46 and hydrogen coordinates were added through the PDB Utilities server.47 Correlations between measured RDCs and RDCs calculated from the PDB structures were made by the PALES software.48

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was conducted with funding from the NIH (Grant R35GM139573 to A.R.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available:

Solution-state NMR spectra of saponin; DLS size distribution profiles of saponin nanodiscs; SEC profile and 1H NMR spectrum associated with purification of saponin nanodiscs by SEC; NMR-based comparison of alignment in purified and unpurified saponin nanodiscs; NMR spectra of purified and unpurified saponin nanodiscs titrated with YbCl3; NMR spectra of DMPC liposomes with and without YbCl3 to show effect of metal ions on DMPC CSA; Correlation plots of experimentally measured RDCs and predicted RDCs from the PDB structures of cytochrome c; PDB codes, descriptions, and RDC correlations for the PDB structures used in the analysis of experimentally measured cytochrome c RDCs (PDF).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Arinaminpathy Y; Khurana E; Engelman DM; Gerstein MB Computational Analysis of Membrane Proteins: The Largest Class of Drug Targets. Drug Discovery Today 2009, 14, 1130–1135. DOI: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Santos R; Ursu O; Gaulton A; Bento AP; Donadi RS; Bologa CG; Karlsson A; Al-Lazikani B; Hersey A; Oprea TI; Overington JP A Comprehensive Map of Molecular Drug Targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2017, 16, 19–34. DOI: 10.1038/nrd.2016.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Johansson LC; Wöhri AB; Katona G; Engström S; Neutze R Membrane Protein Crystallization from Lipidic Phases. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2009, 19, 372–378. DOI: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Overton IM; Barton GJ Computational Approaches to Selecting and Optimising Targets for Structural Biology. Methods 2011, 55, 3–11. DOI: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Warschawski DE; Arnold AA; Beaugrand M; Gravel A; Chartrand É; Marcotte I Choosing Membrane Mimetics for NMR Structural Studies of Transmembrane Proteins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2011, 1808, 1957–1974. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Marcotte I; Auger M Bicelles as Model Membranes for Solid- and Solution-State NMR Studies of Membrane Peptides and Proteins. Concepts in Magnetic Resonance Part A 2005, 24A, 17–37. DOI: 10.1002/cmr.a.20025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Viegas A; Viennet T; Etzkorn M The Power, Pitfalls and Potential of the Nanodisc System for NMR-Based Studies. Biological Chemistry 2016, 397, 1335–1354. DOI: 10.1515/hsz-2016-0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ravula T; Ramamoorthy A Magnetic Alignment of Polymer Macro-Nanodiscs Enables Residual-Dipolar-Coupling-Based High-Resolution Structural Studies by NMR Spectroscopy. Angewandte Chemie 2019, 131, 15067–15070. DOI: 10.1002/ange.201907655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Bibow S; Carneiro MG; Sabo TM; Schwiegk C; Becker S; Riek R; Lee D Measuring Membrane Protein Bond Orientations in Nanodiscs via Residual Dipolar Couplings. Protein Science 2014, 23, 851–856. DOI: 10.1002/pro.2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Hagn F; Nasr ML; Wagner G Assembly of Phospholipid Nanodiscs of Controlled Size for Structural Studies of Membrane Proteins by NMR. Nat Protoc 2018, 13, 79–98. DOI: 10.1038/nprot.2017.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Bayburt TH; Grinkova YV; Sligar SG Self-Assembly of Discoidal Phospholipid Bilayer Nanoparticles with Membrane Scaffold Proteins. Nano Lett. 2002, 2, 853–856. DOI: 10.1021/nl025623k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Ravula T; Ramadugu SK; Di Mauro G; Ramamoorthy A Bioinspired, Size-Tunable Self-Assembly of Polymer–Lipid Bilayer Nanodiscs. Angewandte Chemie 2017, 129, 11624–11628. DOI: 10.1002/ange.201705569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- (13).Sanders CR; Schwonek JP Characterization of Magnetically Orientable Bilayers in Mixtures of Dihexanoylphosphatidylcholine and Dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine by Solid-State NMR. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 8898–8905. DOI: 10.1021/bi00152a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Ravula T; Z. Hardin N; Bai J; Im S-C; Waskell L; Ramamoorthy A Effect of Polymer Charge on Functional Reconstitution of Membrane Proteins in Polymer Nanodiscs. Chemical Communications 2018, 54, 9615–9618. DOI: 10.1039/C8CC04184A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Ravula T; Ramamoorthy A Synthesis, Characterization, and Nanodisc Formation of Non-Ionic Polymers**. Angewandte Chemie 2021, 133, 17022–17025. DOI: 10.1002/ange.202101950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Yang Z; Wang C; Zhou Q; An J; Hildebrandt E; Aleksandrov LA; Kappes JC; DeLucas LJ; Riordan JR; Urbatsch IL; Hunt JF; Brouillette CG Membrane Protein Stability Can Be Compromised by Detergent Interactions with the Extramembranous Soluble Domains. Protein Science 2014, 23, 769–789. DOI: 10.1002/pro.2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Sehgal P; Otzen DE Thermodynamics of Unfolding of an Integral Membrane Protein in Mixed Micelles. Protein Science 2006, 15, 890–899. DOI: 10.1110/ps.052031306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Sehgal P; Mogensen JE; Otzen DE Using Micellar Mole Fractions to Assess Membrane Protein Stability in Mixed Micelles. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2005, 1716, 59–68. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Balandrin MF Commercial Utilization of Plant-Derived Saponins: An Overview of Medicinal, Pharmaceutical, and Industrial Applications. In Saponins Used in Traditional and Modern Medicine; Waller GR, Yamasaki K, Eds.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1996; pp 1–14. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1367-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Peng S; Li Z; Zou L; Liu W; Liu C; Julian McClements D Improving Curcumin Solubility and Bioavailability by Encapsulation in Saponin-Coated Curcumin Nanoparticles Prepared Using a Simple PH-Driven Loading Method. Food & Function 2018, 9, 1829–1839. DOI: 10.1039/C7FO01814B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Rajput ZI; Hu S; Xiao C; Arijo AG Adjuvant Effects of Saponins on Animal Immune Responses. J. Zhejiang Univ. - Sci. B 2007, 8, 153–161. DOI: 10.1631/jzus.2007.B0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Reimer JM; Karlsson KH; Lövgren-Bengtsson K; Magnusson SE; Fuentes A; Stertman L Matrix-M™ Adjuvant Induces Local Recruitment, Activation and Maturation of Central Immune Cells in Absence of Antigen. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e41451. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Tian J-H; Patel N; Haupt R; Zhou H; Weston S; Hammond H; Logue J; Portnoff AD; Norton J; Guebre-Xabier M; Zhou B; Jacobson K; Maciejewski S; Khatoon R; Wisniewska M; Moffitt W; Kluepfel-Stahl S; Ekechukwu B; Papin J; Boddapati S; Jason Wong C; Piedra PA; Frieman MB; Massare MJ; Fries L; Bengtsson KL; Stertman L; Ellingsworth L; Glenn G; Smith G SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein Vaccine Candidate NVX-CoV2373 Immunogenicity in Baboons and Protection in Mice. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 372. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-20653-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Man S; Gao W; Zhang Y; Huang L; Liu C Chemical Study and Medical Application of Saponins as Anti-Cancer Agents. Fitoterapia 2010, 81, 703–714. DOI: 10.1016/j.fitote.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Reichert CL; Salminen H; Weiss J Quillaja Saponin Characteristics and Functional Properties. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology 2019, 10, 43–73. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-food-032818-122010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Oakenfull D Saponins in Food—A Review. Food Chemistry 1981, 7, 19–40. DOI: 10.1016/0308-8146(81)90019-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Gauthier C; Legault J; Girard-Lalancette K; Mshvildadze V; Pichette A Haemolytic Activity, Cytotoxicity and Membrane Cell Permeabilization of Semi-Synthetic and Natural Lupane- and Oleanane-Type Saponins. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2009, 17, 2002–2008. DOI: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Geisler R; Pedersen MC; Hannappel Y; Schweins R; Prévost S; Dattani R; Arleth L; Hellweg T Aescin-Induced Conversion of Gel-Phase Lipid Membranes into Bicelle-like Lipid Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2019, 35, 16244–16255. DOI: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b02077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Geisler R; Prévost S; Dattani R; Hellweg T Effect of Cholesterol and Ibuprofen on DMPC-β-Aescin Bicelles: A Temperature-Dependent Wide-Angle X-Ray Scattering Study. Crystals 2020, 10, 401. DOI: 10.3390/cryst10050401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Geisler R; Cramer Pedersen M; Preisig N; Hannappel Y; Prévost S; Dattani R; Arleth L; Hellweg T Aescin – a Natural Soap for the Formation of Lipid Nanodiscs with Tunable Size. Soft Matter 2021, 17, 1888–1900. DOI: 10.1039/D0SM02043E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Delay C; Gavin JoséA; Aumelas A; Bonnet P-A; Roumestand C Isolation and Structure Elucidation of a Highly Haemolytic Saponin from the Merck Saponin Extract Using High-Field Gradient-Enhanced NMR Techniques. Carbohydrate Research 1997, 302, 67–78. DOI: 10.1016/S0008-6215(97)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kensil CR; Kammer R QS-21: A Water-Soluble Triterpene Glycoside Adjuvant. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 1998, 7, 1475–1482. DOI: 10.1517/13543784.7.9.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Boroske E; Helfrich W Magnetic Anisotropy of Egg Lecithin Membranes. Biophysical Journal 1978, 24 (3), 863–868. DOI: 10.1016/S0006-3495(78)85425-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Prosser RS; Hwang JS; Vold RR Magnetically Aligned Phospholipid Bilayers with Positive Ordering: A New Model Membrane System. Biophysical Journal 1998, 74, 2405–2418. DOI: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77949-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Naito A; Nagao T; Obata M; Shindo Y; Okamoto M; Yokoyama S; Tuzi S; Saitô H Dynorphin Induced Magnetic Ordering in Lipid Bilayers as Studied by 31P NMR Spectroscopy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2002, 1558, 34–44. DOI: 10.1016/S0005-2736(01)00420-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Sreij R; Dargel C; Schweins R; Prévost S; Dattani R; Hellweg T Aescin-Cholesterol Complexes in DMPC Model Membranes: A DSC and Temperature-Dependent Scattering Study. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 5542. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-019-41865-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Ravula T; Kim J; Lee D-K; Ramamoorthy A Magnetic Alignment of Polymer Nanodiscs Probed by Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. Langmuir 2020, 36, 1258–1265. DOI: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b03538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Kaspchak E; Misugi Kayukawa CT; Meira Silveira JL; Igarashi-Mafra L; Mafra MR Interaction of Quillaja Bark Saponin and Bovine Serum Albumin: Effect on Secondary and Tertiary Structure, Gelation and in Vitro Digestibility of the Protein. LWT 2020, 121, 108970. DOI: 10.1016/j.lwt.2019.108970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Baharara J; Amini E; Salek-Abdollahi F Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Saponin Fraction from Ophiocoma Erinaceus. Iranian Journal of Fisheries Sciences 2020, 19, 638–652. DOI: 10.22092/ijfs.2019.118961.0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Toukam PD; Tagatsing MF; Tchokouaha Yamthe LR; Baishya G; Barua NC; Tchinda AT; Mbafor JT Novel Saponin and Benzofuran Isoflavonoid with in Vitro Anti-Inflammatory and Free Radical Scavenging Activities from the Stem Bark of Pterocarpus Erinaceus (Poir). Phytochemistry Letters 2018, 28, 69–75. DOI: 10.1016/j.phytol.2018.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Kobayashi H; Nagao S; Hirota S Characterization of the Cytochrome c Membrane-Binding Site Using Cardiolipin-Containing Bicelles with NMR. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2016, 55, 14019–14022. DOI: 10.1002/anie.201607419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Fung BM; Khitrin AK; Ermolaev K An Improved Broadband Decoupling Sequence for Liquid Crystals and Solids. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2000, 142, 97–101. DOI: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Powles JG; Mansfield P Double-Pulse Nuclear-Resonance Transients in Solids. Physics Letters 1962, 2 (2), 58–59. DOI: 10.1016/0031-9163(62)90147-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Lee W; Tonelli M; Markley JL NMRFAM-SPARKY: Enhanced Software for Biomolecular NMR Spectroscopy. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1325–1327. DOI: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Gentry KA; Prade E; Barnaba C; Zhang M; Mahajan M; Im S-C; Anantharamaiah GM; Nagao S; Waskell L; Ramamoorthy A Kinetic and Structural Characterization of the Effects of Membrane on the Complex of Cytochrome b 5 and Cytochrome c. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 7793. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-017-08130-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Bank RP D. RCSB PDB: Homepage https://www.rcsb.org/ (accessed 2021 -12 -15).

- (47).Bax Group PDB Utility Server - Add Protons to an Existing PDB Structure https://spin.niddk.nih.gov/bax/nmrserver/pdbutil/sa.html (accessed 2021 -12 -15).

- (48).Zweckstetter M NMR: Prediction of Molecular Alignment from Structure Using the PALES Software. Nat Protoc 2008, 3, 679–690. DOI: 10.1038/nprot.2008.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.