1 |. INTRODUCTION

What would it take for you to leave your home and everything you know? What if you left knowing you might not be able to return? If you had to leave quickly, what would you take with you? These are questions that many immigrants must grapple with because of their circumstances. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the global migration of humans had reached the highest levels in recorded human history. International Organization for Migration (IOM) is the global institution that studies and helps inform international laws regarding human migration. This organization posits that 1 in every 30 persons globally is classified broadly as a migrant (IOM, 2022). As the world transitions into the COVID-19 postpandemic phase, it is estimated that the number of global migrants will return to prepandemic levels within a decade, if not sooner (IOM, 2021).

The IOM has promulgated a set of internationally standardized definitions for people who have migrated in Table 1. Although the broadest term is migrant, other terms may be useful to clinicians and researchers, and appreciated by clients and participants, because they classify migrants into various terms that convey the basis for the migration or the migrant’s status. Examples are migrant worker, asylum seeker, refugee, undocumented migrant, and immigrant. Notably, IOM stresses that no human being should be classified as illegal in reference to their residential status in a country. The term illegal is reductive, dehumanizing, xenophobic, and oftentimes rooted in racist ideas.

TABLE 1.

Definitions of migrants and related terms (International Organization for Migration, 2019)

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Migrant | An umbrella term, not defined under international law, reflecting the common lay understanding of a person who moves away from his or her place of usual residence, whether within a country or across an international border, temporarily or permanently, and for a variety of reasons. The term includes a number of well-defined legal categories of people, such as migrant workers; persons whose particular types of movements are legally-defined, such as smuggled migrants; as well as those whose status or means of movement are not specifically defined under international law, such as international students. |

| Note: At the international level, no universally accepted definition for “migrant” exists. The present definition was developed by IOM for its own purposes and it is not meant to imply or create any new legal category. | |

| Asylum seeker | An individual who is seeking international protection. In countries with individualized procedures, an asylum seeker is someone whose claim has not yet been finally decided on by the country in which he or she has submitted it. Not every asylum seeker will ultimately be recognized as a refugee, but every recognized refugee is initially an asylum seeker. |

| Emigrant | From the perspective of the country of departure, a person who moves from his or her country of nationality or usual residence to another country, so that the country of destination effectively becomes his or her new country of usual residence. |

| Immigrant | From the perspective of the country of arrival, a person who moves into a country other than that of his or her nationality or usual residence, so that the country of destination effectively becomes his or her new country of usual residence. |

| Migrant worker | A person who is to be engaged, is engaged, or has been engaged in a remunerated activity in a State of which he or she is not a national. |

| Migration health | A public health topic which refers to the theory and practice of assessing and addressing migration-associated factors that can potentially affect the physical, social and mental well-being of migrants and the public health of host communities. |

| Naturalization | When an immigrant becomes a citizen of the country to which they migrated. |

| Refugee | A person who qualifies for the protection of the United Nations provided by the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), in accordance with UNHCR’s Statute and, notably, subsequent General Assembly’s resolutions clarifying the scope of UNHCR’s competency, regardless of whether or not he or she is in a country that is a party to the 1951 Convention or the 1967 Protocol—or a relevant regional refugee instrument—or whether or not he or she has been recognized by his or her host country as a refugee under either of these instruments. |

| Undocumented migrant | A nonnational who enters or stays in a country without the appropriate documentation. |

Immigrants face many challenges when adapting to life in the host country, including when navigating the healthcare system. Common challenges immigrants experience when navigating the healthcare system are language barriers, changes in socioeconomic status, changes in social support networks, barriers with acculturation, and lack of health insurance and access to quality healthcare services (Bridgewater & Buzzanell, 2010; Cárdenas & de la Sablonnière, 2017; Covington-Ward et al., 2018; Derr, 2016; Gimeno-Feliu et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2012; Li et al., 2019; Matsunaga et al., 2010; Rudmin, 2010; Stimpson et al., 2013; Tartakovsky et al., 2017; Tegegne, 2018).

This editorial will broaden our understanding of the intersections of migration and health outcomes, with implications for nursing and midwifery practice and health researchers. Specifically, we will emphasize how researchers can improve equitable inclusion in research of people who have immigrant status. Consistent with previous editorials in the “Learning the Language of Health Equity” series, our examples will focus on the context in the United States. The international readers of Research in Nursing & Health, however, will find common themes that are relevant to migrant populations in their home countries. All the authors on this team are either immigrants, children of immigrants, or partners to them.

2 |. DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF IMMIGRANTS IN THE UNITED STATES

Immigrants comprised 15% of the US population by 2019, which totaled 44 million individuals (Gelatt & Muzaffar, 2022; Schmidt, 2019). Among adult immigrants (ages ≥18 years) in this group, 21.9 versus 20.3 million were females compared to males, respectively, and 2.5 million children were present. One in seven US residents are immigrants, while one in eight residents is a US-born citizen with at least one immigrant parent (Health Coverage of Immigrants & KFF, 2022). The road to US citizenship is oftentimes challenging and may take between 3 and 10 years depending on immigrants’ birth countries (Wong & Bonaguro, 2020). In 2018, although similar proportions of immigrants and native-born people living in the United States had obtained at least a college degree (one-third), the fractions differ markedly for those having less than a high school diploma: 27% of immigrants versus 9% of those born in this country (Table 2). These statistics have implications for health literacy.

TABLE 2.

Educational profile of immigrants in the United States

| Education Level | Share (%) of all immigrants | Share (%) of all natives |

|---|---|---|

| College degree or more | 32 | 33 |

| Some college | 19 | 31 |

| High school diploma only | 22 | 28 |

| Less than a high-school diploma | 27 | 8 |

Source: US Census Bureau, 2018 American Community Survey 1-year estimates. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/immigrants-in-the-united-states#:%7E:text=In%202018%2C%2044.7%20million%20immigrants,million%20children%20who%20were%20immigrants

Immigrants comprise a sizable fraction of the country’s labor force in many industries, comprising 1/6 of US workers (28.4 million) by 2018. Immigrants account for over one-third of all farming, fishing, and forestry workers—as well as nearly 25% of individuals working in information technology and the mathematical sciences (American Immigration Council, 2020). The largest number of immigrants work in the healthcare and social service industries, which employed >4 million immigrants (Table 3). Further, about 7% of the US nursing and midwifery is workforce comprised of internationally educated nurses (Ghazal et al., 2020).

TABLE 3.

Top industries employing immigrant workers in the United States

| Industry | Number of immigrant workers |

|---|---|

| Health care and social assistance | 4,124,557 |

| Manufacturing | 3,437,569 |

| Accommodation and food services | 3,022,991 |

| Retail trade | 2,979,800 |

| Construction | 2,858,953 |

Source: Analysis of the US Census Bureau’s 2018 American Community Survey 1-year PUMS data by the American Immigration Council.

As immigrants’ children become working adults, some lack documentation of their birth or legal status because they were brought to the United States by their parents at very young ages. These individuals became temporarily protected from deportation through the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) Act (Venkataramani et al., 2017). Among DACA recipients, about 14,000 are enrolled in health professions education programs; however, in most US states they are barred from licensure examinations which would allow in them in clinical practice (Sofer, 2019).

According to the American Immigration Council (2020), immigrants in the United States also contribute billions of dollars in taxes. Immigrant-led households across the United States contributed a total of US$308.6 billion in federal taxes and US$150.0 billion in combined state and local taxes in 2018. Undocumented immigrants in the United States paid an estimated US$20.1 billion in federal taxes and US$11.8 billion in combined state and local taxes in 2018. DACA recipients and those meeting its eligibility requirements paid an estimated US$1.7 billion in combined state and local taxes in 2018 (Legido-Quigley et al., 2019).

3 |. IMMIGRANTS’ ACCESS TO HEALTH INSURANCE IN THE US

Immigrants’ health is impacted by their eligibility for health insurance in the United States. Rules about immigrants’ access to health insurance are set by the states and vary widely (Hacker et al., 2015). These variations affect immigrants of all ages and their access to primary, secondary, and tertiary health services—which sometimes contribute to inequities in health and healthcare outcomes based on geography (Woolhandler & Himmelstein, 2017). All individuals lawfully present in the United States meet certain eligibilities for Medicaid and can purchase insurance through the Affordable Care Act which also has the moniker Obamacare (Health Coverage for Immigrants & HealthCare.gov, 2022). Nurses, midwives, and researchers should be cognizant that, depending on the state, individuals eligible for Medicaid would include but not be limited to low-income families, certain qualified pregnant women and children, those receiving supplemental security income, children and adults at or below 133% of the poverty level, and those with citizenship or lawful resident status (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, [Medicaid, 2022]).

Twenty-nine states provide Medicaid coverage for all pregnant women as well as all children (Health Coverage of Immigrants & KFF, 2022). Immigrants, whether they are citizens or not, become eligible for Medicare at age 65 so long as they have worked the requisite 40 calendar quarters (3-month period) in the United States (Zallman et al., 2013). Among older adult immigrants, 24% have no insurance coverage and are oftentimes restricted by the eligibility criteria for Medicare or Medicaid. Immigrants without employer-sponsored health insurance have challenges affording the private health insurance market since they are not eligible for the federal insurance exchange (Health Coverage of Immigrants & KFF, 2022; Reyes & Hardy, 2015; Sadarangani & Kovner, 2017). Yet immigrants of working age are net contributors to private insurance pools as well as Medicare—meaning they contribute more money than they spend on services (Choi, 2006; Lu & Myerson, 2020; Zallman et al., 2018). Because insured adult US citizens use more health services as compared to immigrants with insurance, the insurance pools are dependent upon immigrants’ contributions for their financial solvency (Himmelstein et al., 2021).

Undocumented immigrants in the United States have few options for health insurance coverage, even if they can afford private insurance (Cohen & Schpero, 2018; Health Coverage of Immigrants & KFF, 2022). One misconception about health insurance coverage for undocumented immigrants is that they can receive Medicaid or other forms of government-sponsored health insurance or benefits. In fact, undocumented individuals are not eligible for any kind of federally sponsored health insurance or welfare benefits (Health Coverage for Immigrants & HealthCare.Gov, 2022). Being an undocumented immigrant reduces access to health insurance and delays access to health services, resulting in poorer health outcomes (Chi & Handcock, 2014; Joseph, 2017; Martinez et al., 2015; Perreira et al., 2018). The only exception is that in some states a pregnant woman may receive health insurance through Medicaid (Health Coverage of Immigrants & KFF, 2022).

4 |. THE IMPACT OF MIGRATION ON IMMIGRANTS’ HEALTH

An individual’s process of migration will have an impact on their health across their lifespan (Abubakar et al., 2018). The impact of migration on immigrants’ health outcomes differs based on their birth country, which is known as the social determinant of the health of “nativity,” the time in their life when they migrated, and the geography and living conditions where they settle (Wickramage et al., 2018). For example, an individual who migrates voluntarily compared to another who has little to no choice (e.g., refugees, asylum seekers) will have very different health profiles and outcomes. The stress of forced migration experienced by many undocumented immigrants has a long-term impact on their physical, emotional, and psychological well-being (Aspinall, 2007; Chen et al., 2017; Jannesari et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2016; Mendelsohn et al., 2014; Willen, 2012).

Empirical studies on immigrants’ health reveal paradoxes and inconsistencies that reflect heterogeneity in health outcomes and the origins of health inequities. Immigrants are generally healthier with lower mortality relative to their US-born counterparts, however, these advantages diminish or disappear over time—a phenomenon known as the Immigrant Health Effect or Paradox (Antecol & Bedard, 2006; Fuller Thomson et al., 2013; Markides & Rote, 2019; Palloni & Arias, 2004; Shor et al., 2017). For example, Black immigrants ages 50–60 years living in the United States >15 years were 4.3 times more likely to develop hypertension relative to those who emigrated <5 years (Hamilton & Hagos, 2020). Immigrants living in the United States >15 years were 17% more likely to have serious psychological distress versus their US-born counterparts. Immigrants’ length of time of residence in the United States was positively associated with a higher prevalence of depression and serious psychological distress (Ikonte et al., 2020). Foreign-born Latinos and other immigrants had a higher risk of developing diabetes versus US-born Latinos. Additionally, the length of time living in the United States was positively associated with higher diabetes incidence among foreign-born non-Hispanic immigrants (Weber et al., 2012). Similarly, foreign-born Asian adults have significant diabetes disadvantages compared to native-born Asian counterparts (Dias et al., 2020; Engelman & Ye, 2019; Gee et al., 2009).

For noncommunicable diseases, the prevalence of cardiovascular disease, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, and some cancers (especially those associated with infectious agents) is often higher among some immigrants relative to their US-born counterparts; while in other groups, the rates of cardiovascular disease and stroke are substantially lower (Castañeda et al., 2015; Gimeno-Feliu et al., 2019; Luiking et al., 2019; Morey, 2018; Rodriguez et al., 2021; Vargas et al., 2017; Yeo, 2017). Evidence also highlighted progressively poorer overall health status among older immigrants such as the increasing prevalence of diabetes found among middle-aged Latino men in California (Engelman & Ye, 2019; Vega et al., 2009). This paradox also emerges among children of immigrants after several generations of residing in the United States. Health outcomes for immigrant children ages <18 are worse relative to native US counterparts and these patterns persist into adulthood and span across generations, regardless of immigrants’ birth countries or culture (Andre & Dronkers, 2017; Cobo et al., 2010; Docquier et al., 2009; Gee et al., 2009; Gelatt, 2020; Ichou & Wallace, 2019; Sadarangani & Kovner, 2017; Salami et al., 2021; Siemons et al., 2017; Singh et al., 2013; Stimpson et al., 2013; Vargas & Ybarra, 2017). Poorer health outcomes may also relate to biases of “grouping” immigrant populations by common identifiers, such as ethnicity (e.g., Asian) or language, as we have stressed in previous editorials (Amburg et al., 2022; Nava et al., 2022; Niles et al., 2022).

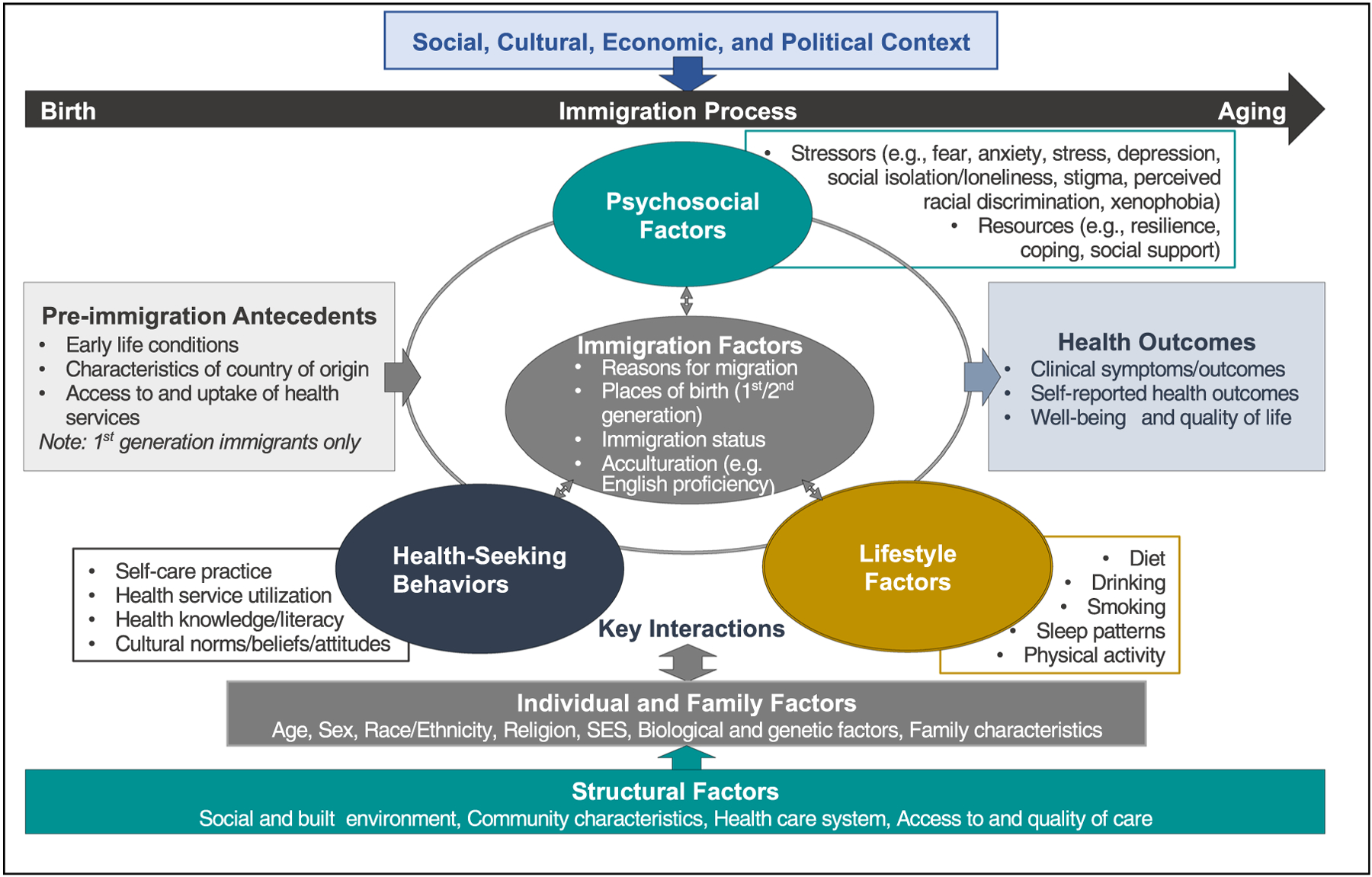

Wu et al. (2021) developed one of the first comprehensive frameworks for immigrant health with a specific focus on oral health-associated outcomes. We have adapted the model to apply to any disease or condition an immigrant may experience. It helps deepen our understanding about immigrant health using a lifespan approach (Figure 1). This conceptual model underscores the specific considerations for healthcare providers as well as researchers.

FIGURE 1.

Immigration and health across the lifespan—An adapted framework from Wu et al. (2021).

5 |. RESEARCH CONSIDERATIONS WHEN WORKING WITH IMMIGRANT POPULATIONS

Research with immigrant populations requires different strategies for engagement and other considerations. The first is the integration of cross-language research methods into the study’s design if the immigrant population does not already speak English or the language of their destination country. Researchers should not assume there are reliable and valid translations of standardized survey instruments and measures; in fact, it is more often the case that translations have been poorly done and not tested for variations associated with dialects and nativity. The qualifications of, timing, use of, and roles of interpreters in the research study need to be planned for well in advance.

For those pursuing precision health studies that rely on technology to track personal health data of any kind, there are multiple ethical challenges to overcome and plan for when designing a research study. First, understanding how technology is used by the population is critical. Many immigrant populations may rely on prepaid minutes for cell phones and may be reluctant to use said minutes for research purposes. Second, any technology that can involve location tracking can present problems for immigrants, regardless of their legal status. While data privacy laws in the European Union are quite strict, they are not in the United States. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) services have been known to use cellphone data to track immigrants regardless of their legal status or whether or not they have a history of justice engagement. Researchers relying on wearable devices or cell phones for their data collection purposes may increase the risk of immigrant populations or their households as persons residing in immigrant households frequently have mixed legal statuses of the residents residing there.

Finally, as with all underrepresented and marginalized populations, researchers need to be aware of “health equity tourism” with immigrant populations. Dr. Elle Lett was the first to name the phenomenon of “health equity tourism” (Garcia, 2022). It occurs when historically privileged researchers decide to conduct studies with the aforementioned populations with no previous training in health equity research methods or track record of working with the community of interest, let alone acknowledgment of the work already completed by scholars from these communities (Garcia, 2022). This practice reinforces the historical sources of structural factors that contribute to health inequities and reflects the entitlement researchers often feel they have to conduct research with any person or group. As with all the groups, we have referred to in this editorial series along with the ones who will be the topic of future editorials, partnering with expert researchers is key for culturally humble research practices.

6 |. IMPROVING EQUITABLE HEALTH CARE ACCESS FOR AND PRACTICES WITH IMMIGRANT POPULATIONS

The first clue about a migrant’s health status can come from their migration story (asked as part of a health assessment), or how they categorize themselves based on the terms defined in Table 1. One key factor unique to immigrant populations that most health professionals will not often integrate into their assessment practices is asking about an individuals’ country of origin and their previous experiences with healthcare services. Knowing the country of origin of the immigrant is important for the healthcare provider to provide person-centered care and gauge health risks. For example, many immigrants may come from areas of the world where exposures to toxic chemicals are common, such as pesticides long banned in the United States at sensitive windows of development that may pose risk for future health conditions or disease processes (Adjei et al., 2019; Bowe et al., 2017; Durand & Massey, 2010; Everett et al., 2017; Garip & Asad, 2016; Kamimura et al., 2018).

In clinical practice, nurses and midwives can adopt and advocate for improving immigrant health in several ways through intentional changes in how they work with the population. Culturally humble practices with immigrants that will enhance assessment data include asking about their heritage and noting that in the chart. For example, dispelling myths about access to insurance coverage can be an incredibly helpful action nurses and midwives can take to develop productive provider–patient relationships as well.

Another important part of a health assessment is verifying the person’s language preference. Even if the person speaks some English (the most commonly spoken language in the United States and that spoken by most healthcare providers), they may not have the vocabulary or comprehension to fully understand what happens during a healthcare encounter without the use of an interpreter.

Once language preference is captured accurately, it becomes easier for healthcare teams to meet the person’s civil right to an interpreter—something that has been codified into law in the United States since the 1960s (Squires & Youdelman, 2019). Accurate language preference data in the chart helps improve the chance that an interpreter can be accessed at important points, like for patient education about medications. Ensuring that only certified interpreters are used (meaning please do not pull in your “bilingual” colleague unless it is an emergency) also helps reduce the risk of adverse events and inequities in health outcomes. Inconsistent or inappropriate use of language access services contributes to said inequities, which include but are not limited to delayed access to healthcare services, medication errors, increased length of stay, increased readmissions to the hospital, and higher rates of adverse events—across all points of the lifespan (Barwise et al., 2019; Dilworth et al., 2009; Flores, 2005; Gerchow et al., 2021; Harris et al., 2017; Hoek et al., 2020; Ju et al., 2017; Narayan & Scafide, 2017; Ramirez et al., 2008; Rocque & Leanza, 2015; Shommu et al., 2016; Silva et al., 2016; Tam et al., 2020; Terui, 2017). Nurses, midwives, and other healthcare professionals who fail to engage interpreters appropriately may also increase their organization’s risk for legal liability (Squires & Youdelman, 2019).

A final action nurses, midwives, and researchers can take to foster culturally humble practices with immigrants that reduce health inequities is ensuring that this population is part of antiracism trainings offered by healthcare organizations. We acknowledge that antiracist training is necessary because the electronic and print media is saturated with negative images and deficit framing of immigrants. For example, immigrants from some racial and ethnic groups are oftentimes stereotyped in the media as poor and dependent on public assistance; coming to the United States to “take” jobs; and portrayed as being more prone to criminality. Conversely, they may also be portrayed as a “model minority”—as is often the case with Asian immigrants—which may cause healthcare providers to underestimate health issues. Since all healthcare professionals are vulnerable to these media stereotypes, antiracism training could mitigate inequitable treatment of immigrants in healthcare settings. Partnering with community-based groups (e.g., religious organizations, schools, cultural centers, etc.) for these trainings can be a productive relationship-building step that builds trust and may draw more people to seek health services when they need them, instead of at a later point when their needs have become more urgent.

7 |. CONCLUSION

Among populations at risk to experience health inequities, immigrants should be considered a unique group. Their identities are the product of multiple intersecting factors and are strongly influenced by their migration experiences. Through intentional clinical and research practices tailored to the complexity of their identities, nurses, midwives, and researchers have the potential to make a significant contribution to reducing healthcare inequities experienced by immigrants across their lifespans.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

No data are available for this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Abubakar I, Aldridge RW, Devakumar D, Orcutt M, Burns R, Barreto ML, Dhavan P, Fouad FM, Groce N, Guo Y, Hargreaves S, Knipper M, Miranda JJ, Madise N, Kumar B, Mosca D, McGovern T, Rubenstein L, Sammonds P, … The UCL–Lancet Commission on Migration and Health. (2018). The health of a world on the move. The Lancet, 392(10164), 2606–2654. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32114-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adjei DN, Stronks K, Adu D, Beune E, Meeks K, Smeeth L, Addo J, Owusu-Dabo E, Klipstein-Grobusch K, Mockenhaupt F, Schulze M, Danquah I, Spranger J, Bahendeka SK, & Agyemang C (2019). Cross-sectional study of association between psychosocial stressors with chronic kidney disease among migrant and non-migrant Ghanaians living in Europe and Ghana: The RODAM study. BMJ Open, 9(8), e027931. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amburg P, Thompson RA, Curtis CA, & Squires A (2022). Different countries and cultures, same language: How registered nurses and midwives can provide culturally humble care to Russian-speaking immigrants. Research in Nursing & Health, 45, 405–409. 10.1002/NUR.22252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andre S, & Dronkers J (2017). Perceived in-group discrimination by first and second generation immigrants from different countries of origin in 27 EU member-states. International Sociology, 32(1), 105–129. 10.1177/0268580916676915 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antecol H, & Bedard K (2006). Unhealthy assimilation: Why do immigrants converge to American health status levels? Demography, 43(2), 337–360. 10.1353/dem.2006.0011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspinall P (2007). The extent of collection of information on migrant and asylum seeker status in routine health and social care data sources in England. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 3(4), 3–13. 10.1108/17479894200700020/FULL/HTML [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barwise AK, Nyquist CA, Suarez NRE, Jaramillo C, Thorsteinsdottir B, Gajic O, & Wilson ME (2019). End-of-Life Decision-Making for ICU patients with limited English proficiency: A qualitative study of healthcare team insights. Critical Care Medicine, 47(10), 1380–1387. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowe B, Xie Y, Xian H, & Al-Aly Z (2017). Geographic variation and US county characteristics associated with rapid kidney function decline. Kidney International Reports, 2(1), 5–17. 10.1016/j.ekir.2016.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridgewater MJ, & Buzzanell PM (2010). Caribbean immigrants’ discourses: Cultural, moral, and personal stories about workplace communication in the United States. Journal of Business Communication, 47(3), 235–265. 10.1177/0021943610369789 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas D, & de la Sablonnière R (2017). Understanding the relation between participating in the new culture and identification: Two studies with Latin American immigrants. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(6), 854–873. 10.1177/0022022117709983 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda H, Holmes SM, Madrigal DS, Young M-ED, Beyeler N, & Quesada J (2015). Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annual Review of Public Health, 36(1), 375–392. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Hall BJ, Ling L, & Renzaho AM (2017). Pre-migration and post-migration factors associated with mental health in humanitarian migrants in Australia and the moderation effect of post-migration stressors: Findings from the first wave data of the BNLA cohort study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(3), 218–229. 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30032-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi JT, & Handcock MS (2014). Identifying sources of health care underutilization among California’s immigrants. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 1(3), 207–218. 10.1007/s40615-014-0028-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S (2006). Insurance status and health service utilization among newly-arrived older immigrants. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 8(2), 149–161. 10.1007/s10903-006-8523-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobo SD, Giorguli SE, & Alba F (2010). Occupational mobility among returned migrants in Latin America: A comparative analysis. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 630(1), 245–268. 10.1177/0002716210368286 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, & Schpero WL (2018). Household immigration status had differential impact on medicaid enrollment in expansion and nonexpansion states. Health Affairs, 37(3), 394–402. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington-Ward Y, Agbemenu K, & Matambanadzo A (2018). “We feel like it was better back home”: Stress, coping, and health in a U.S. dwelling African immigrant community. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 29(1), 253–265. 10.1353/hpu.2018.0018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derr AS (2016). Mental health service use among immigrants in the United States: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services, 67(3), 265–274. 10.1176/appi.ps.201500004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias J, Echeverria S, Mayer V, & Janevic T (2020). Diabetes risk and control in multi-ethnic US immigrant populations. Current Diabetes Reports, 20(12), 73. 10.1007/s11892-020-01358-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth TJ, Mott D, & Young H (2009). Pharmacists’ communication with Spanish-speaking patients: A review of the literature to establish an agenda for future research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 5(2), 108–120. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2008.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docquier F, Lowell BL, & Marfouk A (2009). A gendered assessment of highly skilled emigration. Population and Development Review, 35(2), 297–321. [Google Scholar]

- Durand J, & Massey DS (2010). New world orders: Continuities and changes in Latin American migration. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 630(1), 20–52. 10.1177/0002716210368102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman M, & Ye LZ (2019). The immigrant health differential in the context of racial and ethnic disparities: The case of diabetes. Advances in Medical Sociology, 19, 147–171. 10.1108/S1057-629020190000019008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett CJ, Thompson OM, & Dismuke CE (2017). Exposure to DDT and diabetic nephropathy among Mexican Americans in the 1999–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Environmental Pollution, 222, 132–137. 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.12.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores G (2005). The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care: A systematic review. Medical Care Research and Review, 62(3), 255–299. 10.1177/1077558705275416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller Thomson E, Nuru-Jeter A, Richardson D, Raza F, & Minkler M (2013). The Hispanic paradox and older adults’ disabilities: Is there a healthy migrant effect? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(5), 1786–1814. 10.3390/ijerph10051786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia G (2022). Health equity tourism: Who should be engaging in equity scholarship? AcademyHealth, AcademyHealth Blog. https://academyhealth.org/blog/2022-07/health-equity-tourism-who-should-be-engaging-equity-scholarship [Google Scholar]

- Garip F, & Asad AL (2016). Network effects in Mexico-U.S. migration: Disentangling the underlying social mechanisms. American Behavioral Scientist, 60(10), 1168–1193. 10.1177/0002764216643131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Ro A, Shariff-Marco S, & Chae D (2009). Racial discrimination and health among Asian Americans: Evidence, assessment, and directions for future research. Epidemiologic Reviews, 31(1), 130–151. 10.1093/epirev/mxp009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelatt J (2020). Do employer-sponsored immigrants fare better in labor markets than family-sponsored immigrants? RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 6(3), 70–93. 10.7758/RSF.2020.6.3.04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gelatt J, & Muzaffar C (2022). COVID-19’s effects on U.S. immigration. Migrationpolicy.org. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/covid19-effects-us-immigration [Google Scholar]

- Gerchow L, Burka LR, Miner S, & Squires A (2021). Language barriers between nurses and patients: A scoping review. Patient Education and Counseling, 104(3), 534–553. 10.1016/j.pec.2020.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazal LV, Ma C, Djukic M, & Squires A (2020). Transition-to-U.S. practice experiences of internationally educated nurses: An integrative review. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 42(5), 373–392. 10.1177/0193945919860855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno-Feliu LA, Calderón-Larrañaga A, Díaz E, Laguna-Berna C, Poblador-Plou B, Coscollar-Santaliestra C, & Prados-Torres A (2019). The definition of immigrant status matters: Impact of nationality, country of origin, and length of stay in host country on mortality estimates. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 247. 10.1186/s12889-019-6555-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker K, Anies M, Folb BL, & Zallman L (2015). Barriers to health care for undocumented immigrants: A literature review. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 8, 175–183. 10.2147/RMHP.S70173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton TG, & Hagos R (2020). Race and the healthy immigrant effect. Public Policy & Aging Report, 31(1), 14–18. 10.1093/ppar/praa042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LM, Dreyer BP, Mendelsohn AL, Bailey SC, Sanders LM, Wolf MS, Parker RM, Patel DA, Kim KYA, Jimenez JJ, Jacobson K, Smith M, & Yin HS (2017). Liquid medication dosing errors by Hispanic parents: Role of health literacy and English proficiency. Academic Pediatrics, 17(4), 403–410. 10.1016/j.acap.2016.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Coverage for Immigrants and HealthCare.gov. (2022). https://www.healthcare.gov/immigrants/coverage/

- Health Coverage of Immigrants and KFF. (2022). https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-of-immigrants/

- Himmelstein J, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, Gaffney A, Zallman L, Dickman S, & McCormick D (2021). Health care spending and use among hispanic adults with and without limited English proficiency, 1999–2018. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 40(7), 1126–1134. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek AE, Anker SCP, van Beeck EF, Burdorf A, Rood PPM, & Haagsma JA (2020). Patient discharge instructions in the emergency department and their effects on comprehension and recall of discharge instructions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 75(3), 435–444. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichou M, & Wallace M (2019). The healthy immigrant effect: The role of educational selectivity in the good health of migrants. Demographic Research, 40, 61–94. 10.4054/DEMRES.2019.40.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonte CO, Prigmore HL, Dawson AZ, & Egede LE (2020). Trends in prevalence of depression and serious psychological distress in United States immigrant and non-immigrant populations, 2010–2016. Journal of Affective Disorders, 274, 719–725. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration. (2019). Glossary of migration. https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/iml_34_glossary.pdf

- International Organization for Migration. (2021). Global migration indicators 2021. https://publications.iom.int/books/global-migration-indicators-2021

- International Organization on Migration. (2022). World migration report 2022. International Organization on Migration. https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2022 [Google Scholar]

- Jannesari S, Hatch S, Prina M, & Oram S (2020). Post-migration social–environmental factors associated with mental health problems among asylum seekers: A systematic review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 22(5), 1055–1064. 10.1007/S10903-020-01025-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph TD (2017). Falling through the coverage cracks: How documentation status minimizes immigrants’ access to health care. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 42(5), 961–984. 10.1215/03616878-3940495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju M, Luna N, & Park KT (2017). The effect of limited English proficiency on pediatric hospital readmissions. Hospital Pediatrics, 7(1), 1–8. 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura A, Pye M, Sin K, Nourian MM, Assasnik N, Stoddard M, & Frost CJ (2018). Health and well-being of women migrating from predominantly muslim countries to the United States. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 29(1), 337–348. 10.1353/hpu.2018.0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Suh W, Kim S, & Gopalan H (2012). Coping strategies to manage acculturative stress: Meaningful activity participation, social support, and positive emotion among Korean immigrant adolescents in the USA. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 7(1), 18870. 10.3402/qhw.v7i0.18870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Cho S, Kim YK, & Kim JH (2016). Is there disparity in cardiovascular health between migrant workers and native workers? Workplace Health and Safety, 64(8), 350–358. 10.1177/2165079916633222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legido-Quigley H, Pocock N, Tan ST, Pajin L, Suphanchaimat R, Wickramage K, McKee M, & Pottie K (2019). Healthcare is not universal if undocumented migrants are excluded. BMJ, 366, l4160. 10.1136/bmj.l4160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Lin H-C, Li LMW, & Frieze IH (2019). Cross-cultural study of community engagement in second-generation immigrants. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 50(6), 763–788. 10.1177/0022022119846558 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, & Myerson R (2020). Disparities in health insurance coverage and access to care by English language proficiency in the USA, 2006–2016. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(5), 1490–1497. 10.1007/s11606-019-05609-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luiking M-L, Heckemann B, Ali P, Dekker-van Doorn C, Ghosh S, Kydd A, Watson R, & Patel H (2019). Migrants’ healthcare experience: A meta-ethnography review of the literature. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 51(1), 58–67. 10.1111/jnu.12442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS, & Rote S (2019). The healthy immigrant effect and aging in the United States and other Western countries. Gerontologist, 59(2), 205–214. 10.1093/geront/gny136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez O, Wu E, Sandfort T, Dodge B, Carballo-Dieguez A, Pinto R, Rhodes S, Moya E, & Chavez-Baray S (2015). Evaluating the impact of immigration policies on health status among undocumented immigrants: A systematic review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 17(3), 947–970. 10.1007/s10903-013-9968-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga M, Hecht ML, Elek E, & Ndiaye K (2010). Ethnic identity development and acculturation: A longitudinal analysis of Mexican-heritage youth in the southwest United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 41(3), 410–427. 10.1177/0022022109359689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicaid. (2022). Medicaid eligibility. Accessed September 9, 2022. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/eligibility/index.html

- Mendelsohn JB, Schilperoord M, Spiegel P, Balasundaram S, Radhakrishnan A, Lee CKC, Larke N, Grant AD, Sondorp E, & Ross DA (2014). Is forced migration a barrier to treatment success? Similar HIV treatment outcomes among refugees and a surrounding host community in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. AIDS and Behavior, 18(2), 323–334. 10.1007/s10461-013-0494-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey BN (2018). Mechanisms by which anti-immigrant stigma exacerbates racial/ethnic health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 108(4), 460–463. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan MC, & Scafide KN (2017). Systematic review of racial/ethnic outcome disparities in home health care. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 28(6), 598–607. 10.1177/1043659617700710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nava A, Estrada L, Gerchow L, Scott J, Thompson R, & Squires A (2022). Grouping people by language exacerbates health inequities–The case of Latinx/Hispanic populations in the US. Research in Nursing & Health, 45(2), 142–147. 10.1002/nur.22221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niles PM, Jun J, Lor M, Ma C, Sadarangani T, Thompson R, & Squires A (2022). Honoring Asian diversity by collecting Asian subpopulation data in health research. Research in Nursing & Health, 45(3), 265–269. 10.1002/nur.22229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palloni A, & Arias E (2004). Paradox lost: Explaining the Hispanic adult mortality advantage. Demography, 41(3), 385–415. 10.1353/dem.2004.0024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreira KM, Yoshikawa H, & Oberlander J (2018). A new threat to immigrants’ health–The public-charge rule. New England Journal of Medicine, 379(10), 901–903. 10.1056/nejmp1808020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez D, Engel KG, & Tang TS (2008). Language interpreter utilization in the emergency department setting: A clinical review. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 19(2), 352–362. 10.1353/hpu.0.0019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes AM, & Hardy M (2015). Health insurance instability among older immigrants: Region of origin disparities in coverage. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70(2), gbu218. 10.1093/geronb/gbu218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocque R, & Leanza Y (2015). A systematic review of patients’ experiences in communicating with primary care physicians: Inter-cultural encounters and a balance between vulnerability and integrity. PLoS One, 10(10), e0139577. 10.1371/journal.pone.0139577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez DX, Hill J, & McDaniel PN (2021). A scoping review of literature about mental health and well-being among immigrant communities in the United States. Health Promotion Practice, 22(2), 181–192. 10.1177/1524839920942511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudmin FW (2010). Phenomenology of acculturation: Retrospective reports from the Philippines, Japan, Quebec, and Norway. Culture & Psychology, 16(3), 313–332. 10.1177/1354067X10371139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadarangani TR, & Kovner C (2017). Medicaid for newly resettled legal immigrants. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice, 18(1), 3–5. 10.1177/1527154417704850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salami B, Fernandez-Sanchez H, Fouche C, Evans C, Sibeko L, Tulli M, Bulaong A, Kwankye SO, Ani-Amponsah M, Okeke-Ihejirika P, Gommaa H, Agbemenu K, Ndikom CM, & Richter S (2021). A scoping review of the health of African immigrant and refugee children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3514. 10.3390/ijerph18073514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt PW (2019). An overview and critique of US immigration and asylum policies in the Trump era. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 7(3), 92–102. 10.1177/2331502419866203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shommu NS, Ahmed S, Rumana N, Barron GRS, McBrien KA, & Turin TC (2016). What is the scope of improving immigrant and ethnic minority healthcare using community navigators: A systematic scoping review. International Journal for Equity in Health, 15(1), 6. 10.1186/s12939-016-0298-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shor E, Roelfs D, & Vang ZM (2017). The “hispanic mortality paradox” revisited: Meta-analysis and meta-regression of life-course differentials in Latin American and Caribbean immigrants’ mortality. Social Science and Medicine, 186, 20–33. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemons R, Raymond-Flesch M, Auerswald CL, & Brindis CD (2017). Erratum to: Coming of Age on the Margins: Mental Health and Wellbeing Among Latino Immigrant Young Adults Eligible for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 19(4), 1000. 10.1007/s10903-016-0395-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva MD, Genoff M, Zaballa A, Jewell S, Stabler S, Gany FM, & Diamond LC (2016). Interpreting at the end of life: A systematic review of the impact of interpreters on the delivery of palliative care services to cancer patients with limited English proficiency. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 51(3), 569–580. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh GK, Yu SM, & Kogan MD (2013). Health, chronic conditions, and behavioral risk disparities among U.S. immigrant children and adolescents. Public Health Reports, 128(6), 463–479. 10.1177/003335491312800606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofer D (2019). DACA recipients seeking RN licensure: On a road to nowhere? American Journal of Nursing, 119(10), 12. 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000586092.25369.FF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires A, & Youdelman M (2019). Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act: Strengthening language access rights for patients with limited English proficiency. Journal of Nursing Regulation, 10(1), 65–67. 10.1016/S2155-8256(19)30085-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stimpson JP, Wilson FA, & Su D (2013). Unauthorized immigrants spend less than other immigrants and us natives on health care. Health Affairs, 32(7), 1313–1318. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam I, Huang MZ, Patel A, Rhee KE, & Fisher E (2020). Spanish interpreter services for the hospitalized pediatric patient: Provider and interpreter perceptions. Academic Pediatrics, 20(2), 216–224. 10.1016/j.acap.2019.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartakovsky E, Walsh SD, Patrakov E, & Nikulina M (2017). Between two worlds? Value preferences of immigrants compared to local-born populations in the receiving country and in the country of origin. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(6), 835–853. 10.1177/0022022117709534 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tegegne MA (2018). Linguistic integration and immigrant health: The longitudinal effects of interethnic social capital. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 59(2), 215–230. 10.1177/0022146518757198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terui S (2017). Conceptualizing the pathways and processes between language barriers and health disparities: Review, synthesis, and extension. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 19(1), 215–224. 10.1007/s10903-015-0322-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas ED, Sanchez GR, & Juárez MD (2017). The impact of punitive immigrant laws on the health of Latina/o populations. Politics and Policy, 45(3), 312–337. 10.1111/polp.12203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas ED, & Ybarra VD (2017). U.S. citizen children of undocumented parents: The link between state immigration policy and the health of Latino children. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 19(4), 913–920. 10.1007/s10903-016-0463-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Rodriguez MA, & Gruskin E (2009). Health disparities in the Latino population. Epidemiologic Reviews, 31(1), 99–112. 10.1093/epirev/mxp008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataramani AS, Shah SJ, O’Brien R, Kawachi I, & Tsai AC (2017). Health consequences of the US Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) immigration programme: A quasi-experimental study. The Lancet Public Health, 2(4), e175–e181. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30047-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber MB, Oza-Frank R, Staimez LR, Ali MK, & Venkat Narayan KM (2012). Type 2 diabetes in Asians: Prevalence, risk factors, and effectiveness of behavioral intervention at individual and population levels. Annual Review of Nutrition, 32, 417–439. 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071811-150630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickramage K, Vearey J, Zwi AB, Robinson C, & Knipper M (2018). Migration and health: A global public health research priority. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 987. 10.1186/s12889-018-5932-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willen SS (2012). Migration, “illegality,” and health: Mapping embodied vulnerability and debating health-related deservingness. Social Science and Medicine, 74(6), 805–811. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong C, & Bonaguro J (2020). The value of citizenship and service to the nation. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 6(3), 96. 10.7758/rsf.2020.6.3.05 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woolhandler S, & Himmelstein DU (2017). The relationship of health insurance and mortality: Is lack of insurance deadly? Annals of Internal Medicine, 167(6), 424–431. 10.7326/M17-1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B, Mao W, Qi X, & Pei Y (2021). Immigration and oral health in older adults: An integrative approach. Journal of Dental Research, 100(7), 686–692. 10.1177/0022034521990649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo Y (2017). Healthcare inequality issues among immigrant elders after neoliberal welfare reform: Empirical findings from the United States. European Journal of Health Economics, 18(5), 547–565. 10.1007/s10198-016-0809-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein D, Bor D, & McCormick D (2013). Immigrants contributed an estimated $115.2 billion more to the medicare trust fund than they took out in 2002–09. Health Affairs, 32(6), 1153–1160. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Touw S, Himmelstein DU, & Finnegan KE (2018). Immigrants pay more in private insurance premiums than they receive in benefits. Health Affairs, 37(10), 1663–1668. 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data are available for this manuscript.