Abstract

There is increasing literature examining the use of problematic internet in the context of psychological factors. Most of these studies are focused on the young population. On the other hand, the prolongation of human life and the increasing rate of adult individuals in society’s population cannot be ignored. It is seen that the number of research examining the use of problematic internet in the context of psychological factors is quite limited. In this current study, the problematic internet usage of primary and secondary school students’ parents was examined in happiness, psychological resilience, dispositional hope, self-control and self-management. The research was conducted on 1123 parents. Path analysis was performed to discover the relations between the structures. As a result of the path analysis, it was determined that there is a significant negative relationship between problematic internet use and happiness, problematic internet use and psychological resilience, problematic internet use, and dispositional hope. According to these findings, adults’ high happiness levels, psychological resilience, and hope levels will reduce their problematic internet use. It has been determined that there is a significant indirect relationship between self-control and self-management and problematic internet use. Happiness, psychological resilience, and dispositional hope mediating role in this relationship. Increasing parents’ happiness levels, developing psychological resilience, increasing dispositional hope levels, and developing self-control and self-management skills will reduce problematic internet use. In line with the findings, what can be done to reduce the use of problematic internet has been discussed.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10942-022-00482-y.

Keywords: Adults, parents, problematic internet use, happiness, psychological resilience, dispositional hope, self-control and self-management

Introduction

While the developments in the field of health in the world, the increase in living standards and welfare levels, the decrease in birth and mortality rates, and the average age of the population increase. According to the United Nations (2020) report, the ratio of the adult population to the total population is increasing. It is seen that the continents with the highest rate of adult population in the European continent are led (Statista, 2021). While the number of individuals accepted as adults in the global population structure increases day by day, it is stated that this affects almost every aspect of society. One of the areas where the adult population is concerned is about their problematic internet use (Heo et al., 2015; Sum et al., 2008). Factors such as an increase in technology usage rates and the development of lifelong learning skills cause problems such as problematic internet use in adults (Busch et al., 2021; Devine et al., 2022).

It is seen that the current research on the subject focus on the problematic use of the internet, especially by adolescence and early adult individuals. Less is known about adults’ problematic internet use behaviors and practices (Devine et al., 2022). In addition, it is seen that studies on problematic internet use are mostly conducted in far eastern countries (Chia et al., 2020; Devine et al., 2022; Su et al., 2020). However, it is stated that cultural factors are also influential in problematic internet use (Błachnio et al., 2019; Cheng & Li, 2014; Kuss et al., 2021). Therefore, there is a need for research results in different cultural contexts regarding the generalizability of the results. In this current study, the problematic internet use situations of adults living in Turkey were investigated in the context of psychological factors. This direction aims to explore the structural relationships between problematic internet use, happiness, psychological resilience, dispositional hope, self-control and self-management structures. This current study revealed important information about the psychological connections of problematic internet use. It also raised questions about the generalizability of these results to adults in other national and cultural contexts.

Internet Usage and Adults

Studies show that adults’ rate of internet use, especially due to social media use, has increased (Malaeb et al., 2021; Ng et al., 2021; Statista 2021, 2022). These individuals use the internet to search for information, shop online, follow news sites, follow their friends on social media, listen to music, and watch videos on video-sharing sites (Hunsaker & Hargittai, 2018; Schehl et al., 2019; Foong et al., 2022) reveal that during the Covid 19 pandemic, adults frequently used the internet to search for information about Covid 19. It is stated that factors such as educational status, socioeconomic status, adoption, and use of technology by adults are influential on the internet use status of adults (Yoon et al., 2020). The Pew Research Center (2020) report reveals that 93% of adults in the United States are internet users. In the Statista (2021) report, it is stated that 98% of adults aged 30–49, 96% of adults aged 50–64, and 75% of adults over 65 years old are internet users in the United States. According to the Statista (2022) report, by 2020, 89% of adults aged 25–34, 82% of adults aged 35–44, 66% of adults aged 45–54, and 55–64 years old in Turkey It is stated that 42% of adults in the range of internet users are active internet users. It is noted that this rate in adults will increase as the socio-economic status of countries improves (Busch et al., 2021; Devine et al., 2022). For this reason, it is necessary to pay attention to research on adult internet use. One of the research areas that should be focused on is the problematic internet use behaviors that occur with increasing internet use, especially in adults.

Problematic Internet use and Happiness

Happiness is defined as the abundance of positive emotions, the scarcity of negative emotions, and high life satisfaction (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005; Sheldon & Lyubomirsky, 2021). It is also related to how the individual sees their life and their attitude towards life (Veenhoven, 2003). In other words, happiness is the state of reflecting positive emotions and being cheerful (Datu & Valdez, 2012). Welfare levels and living conditions have a significant impact on the happiness of the individual (Brockmann et al., 2009; Toshkov, 2022). At the same time, there may be essential factors on happiness in cognitive and psychological processes (Lyubomirsky, 2001; Yakushko & Blodgett, 2021). While the content of the goals that the individual sets for themself and the effort they make in this direction increase their happiness, the level of happiness can also be increased by meeting the basic needs of individuals such as security, shelter, and belonging (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005).

Many factors can affect the happiness of adults. Many factors such as family relations, socioeconomic status of the family, and friendly relations can affect the level of happiness of adults (Ford et al., 2022; Gong et al., 2021; Lin et al., 2020; Srivastava & Muhammad, 2021). It is common for adults with low happiness levels to tend to excessive internet use. Because adults who have access to the internet anytime and from anywhere may turn to surf the internet to escape from the problems they experience in their daily lives, therefore, this situation may lead to the development of problematic internet use in them. According to the cognitive-behavioral model developed by Davis (2001), cognitive and behavioral factors are emphasized together when explaining problematic internet use. According to this model, psychopathology factors are considered as factors that have a distal effect on problematic internet use. According to the model, the psychopathology factors of individuals may pose a risk in terms of problematic internet use. This situation may cause the individual to be vulnerable in terms of problematic internet use. Studies say that happiness in adults may be related to psychopathological factors (Karris Bachik et al., 2021; Nikolakakis et al., 2019). Therefore, it is thought that the happiness status of individuals may affect problematic internet use. This is an assumption that needs to be explored. According to the cognitive-behavioral model, an individual’s maladaptive cognitions can affect problematic internet use (Davis, 2001). Accordingly, individuals who are not happy in real life may have maladaptive cognitions such as “I am only happy on the Internet” related to internet use. Therefore, this situation may affect problematic internet use in individuals.

For this reason, it is thought that the real-life happiness of individuals is effective on problematic internet use. According to the problematic internet use model put forward by Caplan (2010), mood regulation, which is the cognitive component of the model, is defined as an individual’s use of the Internet to regulate their mood. An example is the individual’s use of the Internet to eliminate the feeling of unhappiness. When evaluated in terms of this model, individuals’ use of the Internet to avoid their real-life unhappiness may increase their problematic internet use situations. According to researchers, negative personality traits and psychological problems are among the risk factors that lead to problematic internet use behaviors (Tam & Walter, 2013). Unhappiness is seen between negative personality traits and psychological problems (Furnham & Christoforou, 2007; Romito et al., 1999). Accordingly, it is thought that the unhappiness experienced by adults may affect problematic internet use behaviors. No study has been found in the existing literature that examines the relationship between happiness and problematic internet use in adults. Therefore, the present study investigates whether there is a significant relationship between problematic internet use and happiness.

Problematic Internet use and Psychological Resilience

According to Murphy (1987), psychological resilience is a concept related to how a person copes with pressure and how they recover from the trauma. Psychological resilience is about adapting to the situation and being competent due to positive struggle. On the other hand, Fraser et al., (1999) define psychological resilience as the ability to achieve positive and surprising success under challenging conditions and adapt to extraordinary needs and situations. As the individual’s level of psychological resilience increases, their power to cope with the problems they encounter in life will increase, and they will be able to adapt themself better to changing life conditions (Labrague, 2021; Yoruk & Güler, 2021).

Psychological resilience is thought to be very important for adults. Because these individuals may face many problems due to the environment and living conditions, they live in, and they try to adapt to them and overcome them (Gong et al., 2021; Jopp & Rott, 2006). Individuals who have difficulties in adaptation, in other words, those with low psychological resilience, may seek ways to escape from the current conditions. At this point, the internet can be seen as one of the most easily accessible escape routes. Accordingly, excessive internet use may lead to problematic internet use in these individuals. According to the cognitive-behavioral model, psychopathology factors influence problematic internet use (Davis, 2001). According to the model, the psychological states of the individual may have a distal effect on problematic internet use. When the literature is examined, resilience is seen among the psychopathology factors (Collishaw et al., 2007; Kim Cohen, 2007). Therefore, the resilience status of adults may have a distal effect on problematic internet use according to the cognitive-behavioral model. However, this is an assumption that needs to be explored. According to the social cognitive model, the individual’s self-reactive outcome expectations about the internet can directly affect problematic internet use. For example, using the internet to eliminate depression, loneliness or anxiety may pose a risk in problematic internet use (LaRose et al., 2003). Studies reveal significant relationships between self-reactive outcome expectations and resilience (Shapero et al., 2019). Therefore, it is thought that the self-reactive outcome expectations of individuals who have not developed resilience will be higher, affecting problematic internet use according to the social cognitive model. According to the problematic internet use model developed by Caplan (2010), it has been argued that individuals’ poor social skills and psychological problems may cause problematic internet use. According to this model, individuals think that they can avoid the problems they encounter in real life through the internet, which will make them feel safe. According to this, it is thought that since the resilience of individuals will reduce the possibility of individuals experiencing psychological problems, it may also lead to a decrease in problematic internet use. In the existing literature, no research on this subject in adults. This is a gap in the literature that needs to be explored. Therefore, the present study examines how problematic internet use is related to psychological resilience.

Problematic Internet use and Dispositional Hope

Hope includes a positive expectation for the future. The inherent uncertainty of the future is the prerequisite for forming hope (Bruininks & Malle, 2005). From this point of view, dispositional hope can be evaluated as a concept whose realization is not certain but contains a belief about its realization (Niles et al., 2022). Dispositional hope is closely related to the individual’s ability to set goals, cope with and make change even in situations in which they are in darkness and impasse (Bruininks & Malle, 2005; Tarhan & Bacanlı, 2015) see dispositional hope as a shield that is valuable enough to ensure the survival of the individual and supports the well-being of the individual. According to Moulden & Marshall (2005), individuals with high hope levels set goals faster than others, draw plans for the purposes created, and are confident in their abilities. For this reason, the individual needs to have hope to stay connected to life.

Adults are expected to have high hope levels. Because as long as these individuals have hopes, they can set new goals for life, make an effort to reach these goals, and waste their time on them (Di Maggio et al., 2022; Duggleby et al., 2012). On the contrary, there is uncertainty for individuals with a high level of hope; these individuals may not have goals and do not spend time and effort to reach these goals. Therefore, individuals with low hope levels may turn to excessive internet use because they do not have any activities to spend their time on. This may lead to the development of problematic internet use in them. According to the cognitive-behavioral model, psychopathology factors may have a distal effect on problematic internet use (Davis, 2001; Fouladi et al., 2014) revealed in their research that individuals’ hope states are related to psychopathology factors as a psychological variable. Therefore, the hope or hopelessness states of the individuals may affect their psychopathology states of the individuals. Accordingly, according to the cognitive-behavioral model, it is expected to affect individuals’ problematic internet use situations significantly. However, this assumption needs to be investigated when the literature is examined. According to the cognitive-behavioral model, the hope or hopelessness states of individuals can affect problematic internet use as maladaptive cognitions (Davis, 2001). For example, an adult who is desperate to find a job in real life (due to factors such as face-to-face interviews, etc.) may think that he expresses himself better in the internet environment and may have maladaptive cognitions such as “I am only hopeful on the internet” related to internet use. Therefore, this situation may affect problematic internet use in individuals. For this reason, it is thought that individuals’ hope or hopelessness about real life is effective on problematic internet use. According to the problematic internet use model put forward by Caplan (2010), hope/hopelessness is associated with mood regulation, which is one of the cognitive elements of the model. Accordingly, a person experiencing hopelessness in real life may turn to the use of the internet to avoid this emotional state. According to the model, mood regulation directly affects problematic internet use. Accordingly, it is thought that the feelings of hopelessness experienced by the individual in real life will lead to an increase in problematic internet use behaviors. No research examines the relationship between problematic internet use and dispositional hope for adults in the existing literature. Therefore, the present study examines how problematic internet use is related to dispositional hope.

Problematic Internet Use and Self-control and Self-management

Self-control is a person’s ability to prevent, change or avoid undesirable behavioral tendencies (Hofmann et al., 2014). Self-control and self-management are task-oriented cognitive skills that enable people to reach their goals, overcome difficulties related to their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, delay instant pleasures and cope with pressures (Agbaria et al., 2012). Self-control and self-management are people’s ability to decide for themselves when and how to accomplish set tasks or goals. Peterson et al., (2021) state that self-control and self-management determine an individual’s self-determination. Studies have shown that self-control and self-management skills are highly effective factors in individuals’ addictions (Griffin et al., 2021). An individual with advanced self-control and self-management skills is aware of their own situation regarding any factor that will create addiction. If there is excessive use of the factor in question, then the individual will be able to limit themself by controlling themself. However, individuals who have not developed self-control and self-management skills may not be aware of their own situation. Therefore, addiction can develop. Tang et al., (2015) reveal that self-control has a valuable role in reducing addiction. Błachnio & Przepiorka (2016) showed that there is a relationship between self-control and Facebook addiction and that self-control has a functional role in reducing Facebook addiction. Özdemir, Kuzucu, and Ak (2014) revealed in their research that low self-control is associated with internet addiction. Adult individuals with advanced self-control and self-management skills may be aware of their excessive Internet use. Thinking that this will harm them, they may limit their internet use. However, this is a hypothetical situation. LaRose et al., (2003) according to the social cognitive model proposed. The fact that individuals have insufficient self-regulation skills related to the internet is seen as a factor that increases their problematic internet use. According to the model put forward by Caplan (2010), insufficient self-regulation skill, which is one of the cognitive elements of the model, refers to the individual’s difficulty in monitoring, evaluating, and controlling internet use, and inability to organize their lives in a healthy way. Self-control and self-management are self-regulation skills (Haslaman, 2011). Therefore, individuals’ self-control and self-management situations may have an impact on their problematic internet use behaviors. There is no study examining the relationship between problematic internet use and self-control and self-management for adults when the literature is examined. Therefore, the present study examines how problematic internet use is related to self-control and self-management.

Current Study

It is reported in the studies in the literature that internet use by adults is becoming more and more widespread. Although there are many advantages that adults’ internet use provides for them, research reveals that behavioral addictions such as problematic internet use develop in them. It is seen that the current studies in recent years have focused on determining the psychological factors affecting the problematic internet use of adults. However, it is stated that research on this subject is still new, and there are many dimensions that need to be investigated. In this research, the relationships between problematic internet use and happiness, psychological resilience, dispositional hope, self-control and self-management structures have been revealed. This current research, carried out on adults in the context of the variables it deals with, provides an original contribution to the literature. Another unique aspect of the research is that the adults who are the research participants are the parents of primary and secondary school students. It is about investigating the problematic internet use situations of parents. Because parents are the people who will set an example for their children in the correct use of technology, train them on this issue, and supervise them. For this reason, parents with developed problematic internet use may not be able to guide their children in this regard adequately. The number and variety of studies conducted on parents on this subject are few in the literature. It is thought that the research results will expand the flow and depth of research on this subject.

Method

Participants and Process

The research was carried out according to the correlational study. The relational screening method examines the relationships between dependent and independent variables (Creswell, 2003). In the research, the structural relations between problematic internet use and happiness, psychological resilience, dispositional hope, and self-control and self-management structures were revealed.

The research participants are the parents of students studying in a primary school and a secondary school in a city center in Turkey. Paper-based data collection tools prepared by the researchers were applied to this participant group. The prepared questionnaires were sent to the parents of the students by interviewing the school guidance service, and they were asked to answer the questionnaire. The questionnaires answered by the parents were sent back to the school guidance service. The researchers took the questionnaires answered from the school guidance service.

The survey consists of three main parts. In the first part, information was given about the research objectives, ethics, and voluntary participation. In the second part of the questionnaire, demographic information such as the age and gender of the participants were obtained. In the third part of the questionnaire, there are scales related to problematic internet use, happiness, psychological resilience, dispositional hope, self-control and self-management.

The research was conducted on 1123 parents. Of the adults who responded to the questionnaire, 58% were men, and 42% were women. It has been determined that all the participants in the research have a smartphone. The participants stated that 7% of the participants use the internet less than 1 h a day, 33% use the internet for 1–2 h a day, 45% use the internet for 2–3 h a day, and 15% use the internet more than 3 h a day. It is seen that the age range of the adults responding to the questionnaire varies between 29 and 64.

To determine whether the number of participants reached within the scope of the research is sufficient for the study, a sample size calculation was made using the G*Power program (Faul et al., 2009). For the sample size calculation made in the G*Power program, it was seen that the number of participants reached for the sample with a power of 0.99 was sufficient. N:q ratio was considered to examine the relationship between sample size and model complexity (Kline, 2005). Considering the 20:1 ratio for the N:q ratio, it was determined that the number of participants obtained as a result of snowball sampling was sufficient.

Data Collection Tools

The research data were obtained through the questionnaire used by the researchers. In the demographic information section of the questionnaire, data about age, gender, having a smartphone, and daily internet use was obtained from the participants. In the scales section of the questionnaire, the scales are used in the research. These are given below.

Young’s Internet Addiction Test-Short Form: Young’s internet addiction test is a scale used to determine individuals’ Internet addiction. Young developed the form (1998), and Pawlikowski et al., (2013) converted to the short form. Adaptation of this form to Turkish was made by Kutlu et al., (2016). The scale has 12 items and a single factor structure. The scale is in a 5-point Likert structure, varying from 1-never … 5-always. In the third item of the questionnaire, the phrase “Your work related to school or course…” was arranged as “Your work related to your daily work…” for adults. The reliability of the scale was recalculated for this study. The reliability value was found to be 0.83. Some of the items in the scale are as follows: “How often do you find that you stay on-line longer than you intended?”, “How often do you find yourself saying ‘‘just a few more minutes’’ when on-line?”.

Oxford Happiness Questionnaire: The Oxford happiness scale was developed to determine the happiness status of individuals. The scale was developed by Hills & Argyle (2002). The scale was adapted into Turkish by Dogan & Cotok (2011). The scale is a single factor and consists of 7 items. The recalculated reliability value of the scale for this study was.72. Some of the items in the scale are as follows: “I don’t feel particularly pleased with the way I am”, “I feel that life is very rewarding.”.

Brief Resilience Scale: The scale was developed by Smith et al. (2008) to determine the resilience levels of individuals. The scale was adapted into Turkish by Dogan (2015). The scale has two factors. It consists of 6 items in total. The scale is in a 5-point Likert structure. The recalculated reliability value of the scale for this study was.79. Some of the items in the scale are as follows: “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times”, “It does not take me long to recover from a stressful event”.

Dispositional Hope Scale: The scale was developed by Snyder et al., (1991) to determine the hope levels of individuals. The scale was adapted into Turkish by Tarhan and Bacanli (2015). The scale has two factors. It consists of 12 items in total. The scale is in an 8-point Likert structure. The recalculated reliability value of the scale for this study was.79. Some of the items in the scale are as follows: “I can think of many ways to get out of a jam.”, “I feel tired most of the time.”

Self-Control and Self-Management Scale: The scale was developed by Mezo (2009) to determine individuals’ self-control and self-management levels. The scale was adapted into Turkish by Ercoskun (2016). The scale has three factors. It consists of 16 items in total. The scale is in a 6-point Likert structure. The recalculated reliability value of the scale for this study was.83. Some of the items in the scale are as follows: “When I work toward something, it gets all my attention.”, “I have learned that it is useless to make plans.”.

Data Analysis

The research, it is aimed to explore the structural relations between problematic internet use and happiness, psychological resilience, dispositional hope, and self-control and self-management structures for adults. Path analysis was performed to discover the relationships between these structures. The suitability of the data obtained from the study participants for path analysis was tested. For this purpose, it was examined whether the data met the univariate and multivariate normality assumptions. For univariate normality analysis, skewness and kurtosis values were examined. As a result of the study, it was seen that the data changed within the range of ± 1. From this point of view, it can be said that the data meet the univariate normality assumption (Schumacker & Lomax, 2004). VIF and tolerance (T) indices were examined for the multivariate normality assumption. As a result of the analysis, it was determined that the data met the assumption of multivariate normality (VIF < 10, T value was different than zero) (Hair et al., 2014). Based on these findings, it was evaluated that the data obtained from the participants were suitable for path analysis. In the evaluation of the model’s fit revealed in the path analysis, fit indices were considered. The fit index values obtained for the model as a result of the path analysis, the reference ranges of these values, and the comments regarding them are given in the findings section of the article.

Findings

Adults’ Responses to Problematic Internet use, Happiness, Brief Resilience, Dispositional hope, self-control, and self-management Scales

Descriptive statistics are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics

| Scales | Number of items | The lowest score | The highest score |

|

sd | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problematic internet use | 12 | 12.00 | 60.00 | 26.61 | 9.17 | 0.601 | 0.252 | 2.22 |

| Happiness | 7 | 12.00 | 35.00 | 23.76 | 4.51 | 0.232 | − 0.078 | 3.39 |

| Psychological resilience | 12 | 7.00 | 30.00 | 18.87 | 4.09 | 0.475 | 0.954 | 1.57 |

| Dispositional hope | 12 | 8.00 | 64.00 | 44.03 | 13.76 | − 0.368 | − 0.821 | 3.67 |

| Self-control and self-management | 16 | 17.00 | 80.00 | 51.82 | 13.36 | 0.066 | − 0.705 | 3.24 |

As shown in Table 1, the mean score of adults on the problematic internet use scale is 26.61 (2.22 out of 5), the mean score for the happiness questionnaire is 23.76 (3.39 out of 5), the mean score for the brief resilience scale is 18.87 (1.57 out of 8), mean score of dispositional hope scale is 44.03 (3.67 out of 8), mean score for self-control and self-management scale is 51.82 (3.24 out of 6). These results determined that adults’ problematic internet use, and brief resilience scores were low; happiness, dispositional hope, and self-control and self-management scores were moderate.

Relations Between Adults’ Problematic Internet use, Happiness, Brief Resilience, Dispositional hope, self-control, and self-management Scales

The Pearson correlation has investigated relationships between problematic internet use, happiness, brief resilience, dispositional hope, self-control and self-management hope scales.

As given in Table 2, there is a strong and positive correlation between self-control and self-management – dispositional hope (r = .767, p < .01) and self-control and self-management – happiness (r = .603, p < .01) (Pallant, 2001). Also, there is a moderate and positive correlation between happiness — brief resilience (r = .487, p < .01), happiness — dispositional hope (r = .485, p < .01), brief resilience — dispositional hope, (r = .385, p < .01) and brief resilience — self-control and self-management (r = .380, p < .01) (Pallant, 2001). In addition, there is a moderate and negative correlation between problematic internet use — happiness (r=-.396, p < .01), problematic internet use — brief resilience (r=-.346, p < .01), problematic internet use — dispositional hope (r=-.341, p < .01), and problematic internet use — self-control and self-management (r=-.405, p < .01) (Pallant, 2001).

Table 2.

Correlations between variables

| Problematic internet use | Happiness | Psychological resilience | Dispositional hope | Self-control and self-management | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problematic internet use | r | - | ||||

| Happiness | r | − 0.396** | - | |||

| Psychological resilience | r | − 0.346** | 0.487** | - | ||

| Dispositional hope | r | − 0.341** | 0.485** | 0.385** | - | |

| Self-control and self-management | − 0.405** | 0.603** | 0.380** | 0.767** | - |

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

*. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Path Analyses Results

Path analysis was conducted to explore the relationships between the structures of the theoretical model. The model fit indices used to evaluate the findings resulting from the path analysis and their acceptable ranges are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Values of the goodness of fit index in model

| Model value | Perfect fit | Acceptable fit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 /df | 2.783 | 0 ≤ χ2 /df ≤ 3 | 3 <χ2 /df ≤ 5 |

| CFI | 0.99 | 0.95 ≤ CFI ≤ 1 | 0.90 ≤ CFI < 0.95 |

| GFI | 0.99 | 0.95 ≤ GFI ≤ 1 | 0.90 ≤ GFI<0.95 |

| AGFI | 0.94 | 0.90 ≤ AGFI ≤ 1.00 | 0.85 ≤ AGFI <0.90 |

| IFI | 0.99 | 0.95 ≤ IFI ≤ 1 | 0.90 ≤ IFI <0.95 |

| TLI | 0.96 | 0.95 ≤ TLI ≤ 1 | 0.90 ≤ TLI <0.95 |

| NFI | 0.99 | 0.95 ≤ NFI ≤ 1 | 0.90 ≤ NFI <0.95 |

| RMSEA | 0.08 | 0.00 ≤ RMSEA ≤ 0.05 | 0.05< RMSEA ≤ 0.08 |

| SRMR | 0.0193 | 0.00 ≤ SRMR ≤ 0.05 | 0.05< SRMR ≤ 0.10 |

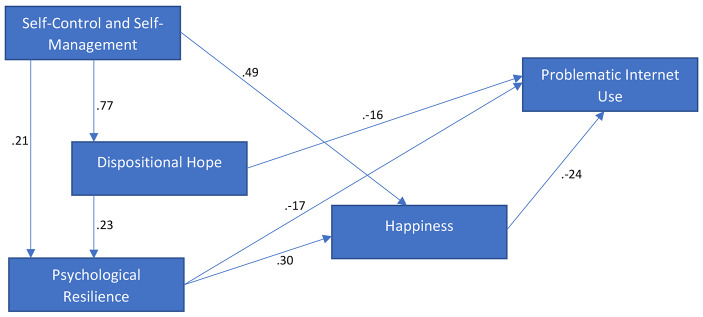

The model fit index values for the research model were calculated for the reliability level of 0.05. The model fit index results calculated in this context are shown in Table 3. It is seen that model fit indices provide the perfect fit, and RMSEA value is an acceptable fit. In this respect, it can be said that the model fit of the research model is good (Hooper et al., 2008; Kline, 2005). The model revealed by path analysis is given in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Path analyses results

As shown in Fig. 1, self-control and self-management directly affected brief resilience (β = 0.21), happiness (β = 0.49), and dispositional hope (β = 0.77). Also, dispositional hope directly affected brief resilience (β = 0.23) and problematic internet use (β=-0.16). Besides that, brief resilience directly affected happiness (β = 0.30) and problematic internet use (β=-0.17). In addition, happiness directly affects problematic internet use (β=-0.24).

Discussion and Conclusion

This current study, it is aimed to determine the factors related to problematic internet use of adult individuals. For this purpose, the structural relationships between problematic internet use and happiness, psychological resilience, dispositional hope, and self-control and self-management were examined. These relationships were tried to be discovered by performing path analysis. As a result of the path analysis, it was determined that there is a significant negative relationship between problematic internet use and happiness, problematic internet use and psychological resilience, problematic internet use and dispositional hope. According to these findings, adults’ high happiness levels, psychological resilience, and hope levels will reduce their problematic internet use.

When the research findings are examined, happiness, psychological resilience, and dispositional hope also play a mediating role. According to these findings, happiness, psychological resilience, and dispositional hope plays a mediating role between self-control and self-management and problematic internet use. Therefore, the development of adults’ self-control and self-management levels increases their happiness, psychological resilience, and dispositional hope levels. Problematic internet use can be reduced depending on the increase in happiness, psychological resilience, and dispositional hope.

Based on the research findings, measures can be taken to increase adult individuals’ levels of happiness, psychological resilience, dispositional hope, self-control and self-management to reduce problematic internet use. An et al., (2020) concluded that the increase in adults’ life satisfaction improves their happiness levels. According to the researchers, it is essential to enhance adults’ cognitive and affective subjective well-being to increase their happiness (Kun & Gadanecz, 2019; Yang & Ma, 2020). According to the researchers, improving their physical activity will improve their happiness levels (Pengpid & Peltzer, 2019; Zhang & Chen, 2019). Based on these findings in the literature, measures can be taken to increase adults’ life satisfaction, improve their cognitive and affective subjective well-being, and enable them to engage in physical activities. Thus, these individuals can be engaged cognitively, emotionally, and physically. This, in turn, will improve their happiness levels. Depending on the increase in happiness, the probability of problematic internet use may decrease. In this context, family ministries and municipalities can make plans for adults.

The results of our study show that resilience is effective in reducing problematic internet use. Therefore, it is essential to take measures to improve the psychological resilience levels of individuals. In Killgore et al., (2020) research, it has been seen that going out more often, doing more exercise, getting more social support from family, friends, and other important people, sleeping better, and praying more often are influential factors in improving the psychological resilience of adults. Studies indicate that keeping the individual busy with a job, providing cognitive preoccupation, and reducing stress levels may be effective in improving the resilience levels of individuals (Brooks et al., 2020; O’Dowd et al., 2018; Riehm et al., 2021). Based on these findings, precautions can be taken to increase the psychological resilience of adults. In particular, it can be effective for the ministry of family and the guidance services of municipalities to support adults in this regard and provide awareness-raising training. Thus, it will be possible to increase the psychological resilience of adults and reduce their problematic internet use.

According to the results of our research, problematic internet use decreases as adults’ hope levels increase. Based on this finding, it is essential to take precautions to improve the hope levels of individuals. On the other hand, Ersoy et al., (2020) found a significant correlation between dispositional hope and psychological well-being. Accordingly, improving the psychological well-being levels of individuals will contribute to increasing their hope levels. Merolla et al., (2021) revealed that hope is associated with day quality and everyday interpersonal interaction in their research. Accordingly, making improvements to increase the quality of the individual’s daily life, and training individuals on managing interpersonal relations and conflict resolution will contribute to the development of the level of hope. In this regard, it may be adequate to provide support to adults by providing guidance services. Thus, by increasing the hope levels of adults, problematic internet users will also be reduced.

According to the results of our research, it was seen that self-control and self-management did not have a direct effect on adults’ problematic internet use. However, it was seen that self-control and self-management had a mediating effect. Therefore, improving individuals’ self-control and self-management skills will enhance their happiness, psychological resilience, and dispositional hope levels. This will reduce problematic internet use. According to studies, individuals’ self-control and self-management skills can be developed from an early age (Duckworth et al., 2014). For this reason, teachers and parents must educate children from an early age to enable them to take responsibility and gain self-regulation skills (Mezo, 2009; Peterson et al., 2021). Thus, when children reach adulthood, they can better control and manage their lives.

This current research includes some limitations. Firstly, the results presented in the research model are valid for adults in Turkey. Internet use of individuals and their psychosocial status may differ according to their culture. Therefore, the generalizability of the results can be investigated by conducting studies on adults from different cultural contexts in future studies. In future studies, the research model presented in this current study can be tested for participants of different ages and education levels, such as high school students and university students. The model results can be compared with the results of adults.

Implications

The results of this research, which was carried out in order to determine the factors affecting the problematic internet use behaviors of adults; revealed that happiness, dispositional hope, and psychological resilience had a direct effect on problematic internet use. Accordingly, it can be said that as the happiness, hope, and psychological resilience levels of adults in real life increase, there may be a decrease in problematic internet usage situations. For this reason, it may be useful for therapists to examine the happiness, hope, and psychological resilience of individuals with problematic internet use behavior disorder, and to focus on the solution of problems related to these variables. On the other hand, research results show that adults’ self-control and self-management skills have an indirect effect on problematic internet use. In other words, happiness, hope, and resilience play a role between self-control and self-management and problematic internet use. In addition, the results of the research reveal that adults’ self-control and self-management skills have a direct effect on their happiness, hope, and resilience. Accordingly, as individuals’ self-control and self-management skills improve, their happiness, hope, and psychological resilience levels increase, and indirectly problematic internet usage situations decrease. Therefore, in clinical cases, it would be appropriate for therapists to measure the self-control and self-management skills of individuals. Behavioral interventions can be planned to eliminate the deficiency of individuals who have deficiencies in these skills. On the other hand, considering the need for individuals to acquire self-regulation skills from an early age, it would be beneficial to carry out plans for students to gain these skills through guidance services at schools and to continue screening and monitoring studies at regular intervals.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Data Availability

The authors are willing to share their data, analytics methods, and study materials with other researchers upon request.

Code Availability

The authors used AMOS functions for their statistical analyses.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in these studies were in accordance with the APA ethical guidelines, the ethical standards of the institutional research committee, and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicting or competing interests to declare.

Informed Consent to Participate

All participants gave full informed consent to participate.

Consent for Publication

All participants gave consent for their data to be used in publication.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ramazan Yilmaz, Email: ramazanyilmaz067@gmail.com.

Fatma Gizem Karaoglan Yilmaz, Email: gkaraoglanyilmaz@gmail.com.

References

- Agbaria Q, Ronen T, Hamama L. The link between developmental components (age and gender), need to belong and resources of self-control and feelings of happiness, and frequency of symptoms among Arab adolescents in Israel. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34(10):2018–2027. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- An HY, Chen W, Wang CW, Yang HF, Huang WT, Fan SY. The relationships between physical activity and life satisfaction and happiness among young, middle-aged, and older adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(13):4817. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Błachnio A, Przepiorka A. Dysfunction of self-regulation and self-control in Facebook addiction. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2016;87(3):493–500. doi: 10.1007/s11126-015-9403-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Błachnio A, Przepiórka A, Gorbaniuk O, Benvenuti M, Ciobanu AM, Senol-Durak E, Ben-Ezra M. Cultural correlates of internet addiction. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking. 2019;22(4):258–263. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2018.0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks S, Amlot R, Rubin GJ, Greenberg N. Psychological resilience and post-traumatic growth in disaster-exposed organisations: overview of the literature. BMJ Mil Health. 2020;166(1):52–56. doi: 10.1136/jramc-2017-000876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruininks P, Malle BF. Distinguishing hope from optimism and related affective states. Motivation and Emotion. 2005;29(4):327–355. doi: 10.1007/s11031-006-9010-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brockmann H, Delhey J, Welzel C, Yuan H. The China puzzle: Falling happiness in a rising economy. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2009;10(4):387–405. doi: 10.1007/s10902-008-9095-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Busch PA, Hausvik GI, Ropstad OK, Pettersen D. Smartphone usage among older adults. Computers in Human Behavior. 2021;121:106783. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan SE. Theory and measurement of generalized problematic internet use: A two-step approach. Computers in Human Behavior. 2010;26(5):1089–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chia DX, Ng CW, Kandasami G, Seow MY, Choo CC, Chew PK, Zhang MW. Prevalence of internet addiction and gaming disorders in Southeast Asia: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(7):2582. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collishaw S, Pickles A, Messer J, Rutter M, Shearer C, Maughan B. Resilience to adult psychopathology following childhood maltreatment: Evidence from a community sample. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31(3):211–229. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Datu JAD, Valdez JP. Exploring filipino adolescents’ conception of happiness. International Journal of Research Studies in Psychology. 2012;3:21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Davis RA. A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior. 2001;17(2):187–195. doi: 10.1016/S0747-5632(00)00041-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devine D, Ogletree AM, Shah P, Katz B. Internet addiction, cognitive, and dispositional factors among US adults. Computers in Human Behavior Reports. 2022;6:100180. doi: 10.1016/j.chbr.2022.100180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Maggio I, Montenegro E, Little TD, Nota L, Ginevra MC. Career adaptability, hope, and life satisfaction: An analysis of adults with and without substance use disorder. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2022;23(2):439–454. doi: 10.1007/s10902-021-00405-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan T, Cotok NA. Adaptation of the short form of the Oxford Happiness Questionnaire into Turkish: A validity and reliability study. Turkish Psychological Counseling and Guidance Journal. 2011;4(36):165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Dogan T. Adaptation of the brief resilience scale into turkish: a validity and reliability study. The Journal of Happiness & Well-Being. 2015;3(1):93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth AL, Gendler TS, Gross JJ. Self-control in school-age children. Educational Psychologist. 2014;49(3):199–217. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2014.926225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duggleby W, Hicks D, Nekolaichuk C, Holtslander L, Williams A, Chambers T, Eby J. Hope, older adults, and chronic illness: a metasynthesis of qualitative research. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2012;68(6):1211–1223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ercoskun MH. Adaptation of self-control and self-management scale (scms) in turkish culture: a study on reliability and validity. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice. 2016;16:1125–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Ersoy K, Altın B, Sarıkaya BB, Özkardaş OG. The comparison of impact of health anxiety on dispositional hope and psychological well-being of mothers who have children diagnosed with autism and mothers who have normal children, in Covid-19 pandemic. Social Sciences Research Journal. 2020;9(2):117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41(4):1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foong HF, Lim SY, Rokhani FZ, Bagat MF, Abdullah SFZ, Hamid TA, Ahmad SA. For better or for worse? a scoping review of the relationship between internet use and mental health in older adults during the co covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(6):3658. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19063658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Jampaklay A, Chamratrithirong A. A multilevel longitudinal study of individual, household and village factors associated with happiness among adults in the southernmost provinces of Thailand. Applied Research in Quality of Life. 2022;17(3):1459–1476. doi: 10.1007/s11482-021-09973-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fouladi Z, Ebrahimi A, Manshaei G, Afshar H, Fouladi M. Investigation of relationship between positive psychological variables (spirituality and hope) psychopathology (depression, stress, anxiety) and quality of life in hemodialysis patients Isfahan–2012. Journal of Research in Behavioural Sciences. 2014;11:567–577. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser MW, Richman JM, Galinsky MJ. Risk, protection and resilience: toward a conceptual framework for social work practice. Social Work Research. 1999;23:129–208. doi: 10.1093/swr/23.3.131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furnham A, Christoforou I. Personality Traits, Emotional Intelligence, and Multiple Happiness. North American Journal of Psychology. 2007;9(3):339–462. [Google Scholar]

- Gong WJ, Wong BYM, Ho SY, Lai AYK, Zhao SZ, Wang MP, Lam TH. Family e-Chat group use was associated with family wellbeing and personal happiness in Hong Kong adults amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(17):9139. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KW, Scheier LM, Komarc M, Botvin GJ. Adolescent transitions in self-management strategies and young adult alcohol use. Evaluation & The Health Professions. 2021;44(1):25–41. doi: 10.1177/0163278720983432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE, Tatham RL. Multivariate data analysis. 7. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Haslaman, T. (2011). Effect of an online learning environment on teachers’ and students’ self-regulated learning skills. Doctoral Dissertation, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey

- Heo J, Chun S, Lee S, Lee KH, Kim J. Internet use and well-being in older adults. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking. 2015;18(5):268–272. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hills P, Argyle M. The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire: a compact scale for the measurement of psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;33(7):1073–1082. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00213-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Luhmann M, Fisher RR, Vohs KD, Baumeister RF. Yes, but are they happy? Effects of trait self-control on affective well‐being and life satisfaction. Journal of Personality. 2014;82(4):265–277. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen MR. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining modelfit. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods. 2008;6(1):53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hunsaker A, Hargittai E. A review of Internet use among older adults. New Media & Society. 2018;20(10):3937–3954. doi: 10.1177/1461444818787348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jopp D, Rott C. Adaptation in very old age: exploring the role of resources, beliefs, and attitudes for centenarians’ happiness. Psychology and Aging. 2006;21(2):266. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karris Bachik MA, Carey G, Craighead WE. VIA character strengths among US college students and their associations with happiness, well-being, resiliency, academic success and psychopathology. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2021;16(4):512–525. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1752785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore WD, Taylor EC, Cloonan SA, Dailey NS. Psychological resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown. Psychiatry Research. 2020;291:113216. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Cohen J. Resilience and developmental psychopathology. Child and adolescent psychiatric clinics of North America. 2007;16(2):271–283. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principle and practice of structural equation modelling. New York, NY: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kun A, Gadanecz P. Workplace happiness, well-being and their relationship with psychological capital: A study of Hungarian Teachers. Current Psychology. 2019;41:185–199. doi: 10.1007/s12144-019-00550-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuss DJ, Kristensen AM, Lopez-Fernandez O. Internet addictions outside of Europe: A systematic literature review. Computers in Human Behavior. 2021;115:106621. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kutlu M, Savcı M, Demir Y, Aysan F. Turkish adaptation of Young’s Internet Addiction Test-Short Form: a reliability and validity study on university students and adolescents. Anatolian Journal of Psychiatry. 2016;17(1):69–76. doi: 10.5455/apd.190501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Labrague LJ. Psychological resilience, coping behaviours and social support among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review of quantitative studies. Journal of Nursing Management. 2021;29(7):1893–1905. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRose R, Lin CA, Eastin MS. Unregulated Internet usage: Addiction, habit, or deficient self-regulation? Media Psychology. 2003;5(3):225–253. doi: 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0503_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YT, Chen M, Ho CC, Lee TS. Relationships among leisure physical activity, sedentary lifestyle, physical fitness, and happiness in adults 65 years or older in Taiwan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(14):5235. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17145235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S. The role of cognitive and motivational processes in well-being. American Psychologist. 2001;3:239–249. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Sheldon KM, Schkade D. Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology. 2005;9:111–131. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.9.2.111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malaeb D, Salameh P, Barbar S, Awad E, Haddad C, Hallit R, Hallit S. Problematic social media use and mental health (depression, anxiety, and insomnia) among Lebanese adults: Any mediating effect of stress? Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2021;57(2):539–549. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merolla AJ, Bernhold Q, Peterson C. Pathways to connection: An intensive longitudinal examination of state and dispositional hope, day quality, and everyday interpersonal interaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2021;38(7):1961–1986. doi: 10.1177/02654075211001933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mezo PG. The self-control and self-management scale (SCMS): Development of an adaptive self-regulatory coping skills instrument. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2009;31(2):83–93. doi: 10.1007/s10862-008-9104-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moulden, Marshall Hope in the treatment of sexual offenders: The potential application of hope theory. Psychology Crime & Law. 2005;11(3):329–342. doi: 10.1080/10683160512331316361. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, L. B. (1987). Further reflections on resilience. (Ed: E. J. Anthony & B. J. Cohler) The Invulnerable Child. New York: The Guilford Press

- Ng Fat L, Cable N, Kelly Y. Associations between social media usage and alcohol use among youths and young adults: findings from Understanding Society. Addiction. 2021;116(11):2995–3005. doi: 10.1111/add.15482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolakakis N, Dragioti E, Paritsis N, Tsamakis K, Christodoulou NG, Rizos EN. Association between happiness and psychopathology in an elderly regional rural population in Crete. Psychiatriki. 2019;30(4):299–310. doi: 10.22365/jpsych.2019.304.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niles JK, Gutierrez D, Dukes AT, Mullen PR, Goode CD. Understanding the relationships between personal growth initiative, hope, and abstinence self-efficacy. Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling. 2022;43:15–25. doi: 10.1002/jaoc.12099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dowd E, O’Connor P, Lydon S, Mongan O, Connolly F, Diskin C, Byrne D. Stress, coping, and psychological resilience among physicians. BMC Health Services Research. 2018;18(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3541-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallant, J. (2001). SPSS: survival manual. McPherson

- Pawlikowski M, Altstötter-Gleich C, Brand M. Validation and psychometric properties of a short version of Young’s Internet Addiction Test. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29(3):1212–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pengpid, S., & Peltzer, K. (2019). Sedentary behaviour, physical activity and life satisfaction, happiness and perceived health status in university students from 24 countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(12), 2084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Peterson SM, Aljadeff-Abergel E, Eldridge RR, VanderWeele NJ, Acker NS. Conceptualizing self-determination from a behavioral perspective: The Role of choice, self-control, and self-management. Journal of Behavioral Education. 2021;30(2):299–318. doi: 10.1007/s10864-020-09368-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center (2020). Internet use over time. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/

- Riehm KE, Brenneke SG, Adams LB, Gilan D, Lieb K, Kunzler AM, Thrul J. Association between psychological resilience and changes in mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;282:381–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romito P, Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Lelong N. What makes new mothers unhappy: psychological distress one year after birth in Italy and France. Social Science & Medicine. 1999;49(12):1651–1661. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schehl B, Leukel J, Sugumaran V. Understanding differentiated internet use in older adults: A study of informational, social, and instrumental online activities. Computers in Human Behavior. 2019;97:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2019.03.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacker RE, Lomax RG. A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Shapero BG, Farabaugh A, Terechina O, DeCross S, Cheung JC, Fava M, Holt DJ. Understanding the effects of emotional reactivity on depression and suicidal thoughts and behaviors: Moderating effects of childhood adversity and resilience. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2019;245:419–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon KM, Lyubomirsky S. Revisiting the sustainable happiness model and pie chart: can happiness be successfully pursued? The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2021;16(2):145–154. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2019.1689421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, Holleran SA, Irving LM, Sigmon ST, Yoshinobu L, Gibb J, Langelle C, Harney P. The will and ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60(4):570–585. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, S., & Muhammad, T. (2021). In pursuit of happiness: Changes in living arrangement and subjective well-being among older adults in India. Journal of Population Ageing, 1–17. 10.1007/s12062-021-09327-5

- Statista (2021). World population by age and region. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/265759/world-population-by-age-and-region/#:~:text=Globally%2C%20about%2026%20percent%20of,over%2065%20years%20of%20age

- Statista (2021). Percentage of internet users by age groups in the US. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/266587/percentage-of-internet-users-by-age-groups-in-the-us/

- Statista (2022). Turkey internet users use accessed internet daily age. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1241887/turkey-internet-users-use-accessed-internet-daily-age/

- Su W, Han X, Yu H, Wu Y, Potenza MN. Do men become addicted to internet gaming and women to social media? A meta-analysis examining gender-related differences in specific internet addiction. Computers in Human Behavior. 2020;113:106480. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sum S, Mathews RM, Hughes I, Campbell A. Internet use and loneliness in older adults. CyberPsychology & Behavior. 2008;11(2):208–211. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YY, Posner MI, Rothbart MK, Volkow ND. Circuitry of self-control and its role in reducing addiction. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2015;19(8):439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarhan S, Bacanlı H. Adaptation of dispositional hope scale into turkish: validity and reliability study. The Journal of Happiness & Well-Being. 2015;3(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Toshkov D. The relationship between age and happiness varies by ıncome. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2022;23(3):1169–1188. doi: 10.1007/s10902-021-00445-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (2020). World population ageing 2020. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Highlights.pdf

- Veenhoven R. Arts of living. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2003;4:373–384. doi: 10.1023/B:JOHS.0000005773.08898.ae. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yakushko O, Blodgett E. Negative reflections about positive psychology: On constraining the field to a focus on happiness and personal achievement. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 2021;61(1):104–131. doi: 10.1177/0022167818794551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Ma J. How an epidemic outbreak impacts happiness: Factors that worsen (vs. protect) emotional well-being during the coronavirus pandemic. Psychiatry Research. 2020;289:113045. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon H, Jang Y, Vaughan PW, Garcia M. Older adults’ internet use for health information: digital divide by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2020;39(1):105–110. doi: 10.1177/0733464818770772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, K. S. (1998). Caught in the net: How to recognize the signs of internet addiction–and a winning strategy for recovery. John Wiley & Sons

- Yoruk S, Guler D. The relationship between psychological resilience, burnout, stress, and sociodemographic factors with depression in nurses and midwives during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross‐sectional study in Turkey. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2021;57(1):390–398. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Chen W. A systematic review of the relationship between physical activity and happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2019;20(4):1305–1322. doi: 10.1007/s10902-018-9976-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors are willing to share their data, analytics methods, and study materials with other researchers upon request.

The authors used AMOS functions for their statistical analyses.