Abstract

Background

As the United States continues to tackle the opioid epidemic, it is imperative for digital healthcare organizations to provide Internet users with accurate and accessible online resources so that they can make informed decisions with regards to their health.

Objective

The primary objectives were to adapt and modify a previously established usability methodology from literature, apply this modified methodology in order to perform usability analysis of opioid-use-disorder (OUD)-related websites, and make important recommendations that OUD-related digital health organizations may utilize to improve their online presence.

Methods

A list of 208 websites (later refined) was generated for usability testing using a modified Google Search methodology. Four keywords were chosen and used in the search: “DEA-X Waiver Training”, “opioid-use-disorder (OUD) Initiatives”, “Buprenorphine Assisted Treatment”, and “Opioid-Use Disorder Websites”. Usability analysis was performed concurrently with optimization of the methodology. OUD websites were analyzed and scored on several usability categories established by previous literature.

Results

“DEA-X Waiver Training” yielded websites that scored the highest average in “Accessibility” (0.84), while “Opioid-Use Disorder Websites” yielded websites that scored the highest average in “Content Quality” (0.67). “Buprenorphine Assisted Treatment” yielded websites that scored the highest average across “Marketing” (0.52), “Technology” (0.89), “General Usability” (0.69), and “Overall Usability” (0.68). “Technology” and “Marketing” were the highest and lowest scoring usability categories, respectively. T-test analysis revealed that each usability, except “Marketing” had a pair of one or more keywords that were significantly different with a p-value that was equal to or less than 0.05.

Conclusions

Based on the study findings, we recommend that digital organizations in the OUD space should improve their “General Usability” score by making their websites easier to find online. Doing so, may allow users, especially individuals in the OUD space, to discover accurate information that they are seeking. Based on the study findings, we also made important recommendations that OUD-related digital organizations may utilize in order to improve website usability as well as overall reach.

Keywords: Opioid epidemic, opioid-use disorder, usability testing

Introduction

Background

The United States continues to tackle an ongoing public health crisis: the opioid epidemic.1 According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), opioid-related overdoses accounted for approximately 500,000 deaths between the years 1999 and 2019.2 This highlights the urgency of developing high-yield interventions targeted toward mitigating the opioid epidemic.

The Internet acts as an important resource that individuals can utilize in order to manage their health.3 However, several barriers exist that people encounter with regards to health information access through the Internet such as sociodemographic factors, users’ skill levels on how to effectively search for information, as well as the accuracy of the information that is available to users on the Internet.4

Healthcare organizations, therefore, play a critical role in providing accurate and accessible online resources where users can make informed decisions for their health.5 In this digital age, people are increasingly turning to the Internet as the primary source of information and to address their healthcare needs.6,7 The information search engine, Google, is considered to be “the most popular search engine within the United States”.8 A scholarly work by Scherr et al. advocated for proportionate dissemination of digital health information through the use of search engines such as Google.9 Scherr and colleagues analyzed the search engine, Google, and found that word-choice played an important role in widening this digital information gap; sometimes with detrimental outcomes.9 Addressing some of this concern in the opioid-use-disorder (OUD) space through website usability analysis became the motivation for our study. Website usability refers to the user experience as a whole; websites that are not only user-friendly and easily accessible but present information that is easily understandable for all online users.5

Objective

The main objectives of this study were based on the objectives by Calvano et al. but were adapted toward analyzing the usability of OUD-related websites.5 Therefore, the primary objectives were to adapt and modify a previously established usability methodology by Calvano et al., apply this modified usability methodology for the analysis of OUD-related websites, and based on the results of the analysis of OUD websites, make important recommendations that digital health organizations in the OUD space may utilize in order to improve their online presence.5

Methods

Study design

In order to generate a list of OUD-related websites for usability testing, the search methodology by Wang et al. was adapted and modified.10 Using the Google Search engine, the following keywords were chosen: “OUD Initiatives”, “DEA-X Waiver Training”, “Buprenorphine Assisted Treatment”, and “Opioid-Use Disorder Websites” to generate a list of websites. These four terms were chosen based on Google Trends. Starting broadly by analyzing Google Trends for Opioid-Use Disorder, the first trending search term was “Opioid-Use Disorder Websites.” We then assessed the trends associated with this term and found “OUD Initiatives” to be most closely trending with the category of websites. In a stepwise approach, we chose the closest trending topic of buprenorphine treatment followed by DEA-X Waiver Training which aids in the prescription of buprenorphine. This input–output selection effort helped isolate search terms that could be used is replicated from Calvano et al. As per Wang et al., the top 200 Google Search results for each keyword were identified for usability analysis.10 Websites that were irrelevant and outdated were manually excluded from the search criteria. A list of 208 websites using the four search keywords was compiled between 20 April 2021 and 23 April 2021. This compiled list of 208 websites can be found in (Multimedia Appendix 1: Compiled list of OUD websites using keyword methodology). This list was subsequently refined to a final list of 96 websites to exclude sites that did not yield certain usability metrics. Sites that did not meet usability metrics were excluded based on redundancy or irrelevancy. Redundant sites were those that shared the same URL as another site. Irrelevant sites were those that were outdated or focused on topics outside OUD. The final sample size for this study was “n = 96” websites. The refined list of 96 websites can be found in (Multimedia Appendix 2: Refined list of OUD websites using keyword methodology).

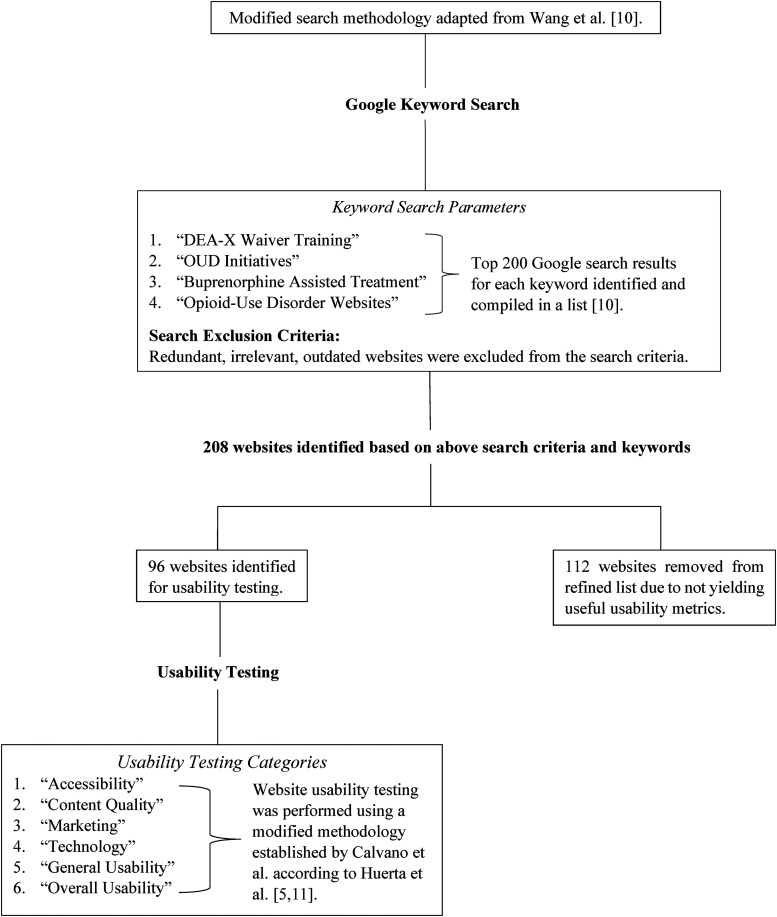

Website usability testing was performed from April 24, 2021 to May 19, 2021 with the methodology established by Calvano et al. according to Huerta et al.; analysis was performed concurrently with optimization of the methodology.5,11 More details on the updated methodology used can be found in (Multimedia Appendix 3: Optimized website usability analysis methodology). The most notable modifications included the automation of data compilation for several usability metrics in addition to the integration of the “Spelling” metric into search engine optimization (SEO) Screaming Frog capabilities as well as the utilization of Google Pagespeed Insights performance score as the sole metric for web page speed (given the capacity for automation via API and its robustness in evaluating web page performance). The overall methodology of this study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overall methodological flowchart illustrating the adapted and modified search and usability testing methodologies.

Usability was organized and scored on several categories described briefly in Table 1; these categories were “Accessibility”, “Content Quality”, “Marketing”, “Technology”, “General Usability”, and “Overall Usability”.5

Table 1.

Usability testing categories used for the analysis of OUD websites.5

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| “Accessibility” | This category evaluates the ability of users that have different computer literacy levels to easily access the information on a website that they are seeking5. |

| “Content Quality” | This category evaluates factors such as content on the website, how often the content on the website is updated, relevancy of the available content, and website layout that can be easily read5. |

| “Marketing” | This category evaluates the ability of users using search engines to easily find websites that they are seeking5. |

| “Technology” | This category evaluates factors in overall website infrastructure like the speed of a website, etc.5. |

| “General Usability” | In this category, the general usability score was determined based on an overall score from the four categories described above5. This category aims to evaluate the overall quality of a website5. |

| “Overall Usability” | In this category, the overall usability score was determined by rank order calculation based on the five categories described above and a weighted percentage was then applied5. |

Results

Table 2 provides the average usability scores, SD, and standard error (SE) for each category from websites using keywords.

Table 2.

Keyword Google searches score summary statistics from usability analysis.

| Category | “DEA-X Waiver Training” | “OUD Initiatives” | “Buprenorphine Assisted Treatment” | “Opioid-Use Disorder Websites” | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | SD | SE | Score | SD | SE | Score | SD | SE | Score | SD | SE | |

| “Accessibility” | 0.84 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.74 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.80 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.78 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| “Content Quality” | 0.52 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.55 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.61 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.67 | 0.18 | 0.04 |

| “Marketing” | 0.46 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.52 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.48 | 0.12 | 0.03 |

| “Technology” | 0.83 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.80 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.89 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.81 | 0.12 | 0.03 |

| “General Usability” | 0.67 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.65 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.69 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.65 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| “Overall Usability” | 0.65 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.63 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.68 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.65 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

SE: standard error.

Figures 2 to 5 indicate the average usability range for each category from websites using keywords.

Figure 2.

Average maximum and minimum usability score based on “DEA-X Waiver Training” keyword Google Search.

Figure 5.

Average maximum and minimum usability score based on “Opioid-Use Disorder Websites” keyword Google Search.

Figure 3.

Average maximum and minimum usability score based on “OUD Initiatives” keyword Google Search.

Figure 4.

Average maximum and minimum usability score based on “Buprenorphine Assisted Treatment” keyword Google Search.

Figures 2 to 5 show (1) Average maximum and minimum usability score based on “DEA-X Waiver Training” keyword Google Search; (2) Average maximum and minimum usability score based on “OUD Initiatives” keyword Google Search; (3) Average maximum and minimum usability score based on “Buprenorphine Assisted Treatment” keyword Google Search; and (4) Average maximum and minimum usability score based on “Opioid-Use Disorder Websites” keyword Google Search.

Figure 6 highlights the average usability scores from websites using the keywords. Usability scores ranged from 0 to 1. A score of 0 indicates that a website performed poorly while a score of 1 indicates good performance. The keyword “DEA-X Waiver Training” yielded websites that scored the highest average in the “Accessibility” category (0.84), while the keyword “Opioid-Use Disorder Websites” yielded websites that scored the highest average in the “Content Quality” category (0.67). The keyword “Buprenorphine Assisted Treatment” yielded websites that scored the highest average across four categories: “Marketing” (0.52), “Technology” (0.89), “General Usability” (0.69), and “Overall Usability” (0.68). “Buprenorphine Assisted Treatment” or “Opioid-Use Disorder Websites” scored similarly across “Accessibility” and “Content Quality” usability categories. For “Content Quality”, “Opioid-Use Disorder Websites” scored the highest

Figure 6.

Average usability scores based on keyword Google searches with significant p-values indicated.

Complete results of T-test analysis can be found in Table 3 in (Multimedia Appendix 4: T-test analysis of usability categories and scores). The p-values highlighted yielded keywords with usability scores that are significant (with a calculated P-value that was equal to or less than 0.05) in comparison with other keywords. Conversely, p-values not highlighted yielded keywords with usability scores that are not significant (with a calculated p-value that was greater than 0.05) in comparison with other keywords.

A graphical representation of the average usability scores along with significant p-values from T-test analysis is also shown in Figure 6. Complete results of the optimized usability testing of the refined list of 96 websites can be found in Table 4 in (Multimedia Appendix 5: Usability analysis results (websites’ rank and score)).

Figure 6 represents average usability scores based on keyword Google searches with significant p-values indicated. For “Accessibility”, keywords (“DEA-X Waiver Training” and “OUD Initiatives”) and (“Opioid-Use Disorder Websites” and ” Buprenorphine Assisted Treatment”) usability scores were significant. For “Content Quality”, keywords (“DEA-X Waiver Training” and “Opioid-Use Disorder Websites”) usability scores were significant. For “Marketing”, no keywords and their respective usability scores were significant. For “Technology”, keywords (“OUD Initiatives” and “Buprenorphine Assisted Treatment”) and (“Opioid-Use Disorder Websites” and “Buprenorphine Assisted Treatment”) usability scores were significant. For “General Usability”, keywords (“Opioid-Use Disorder Websites” and “Buprenorphine Assisted Treatment”) usability scores were significant. Lastly, for “Overall Usability”, keywords (“OUD Initiatives” and “Buprenorphine Assisted Treatment”) usability scores were significant.

Discussion

Principal findings

The data suggests that “Technology” was the highest scoring usability category among all four keywords. This could be attributed to an improved and consistent maintenance of website infrastructure (based on the definition of this usability category described earlier) among OUD-related digital health organizations.5 The keyword, “DEA-X Waiver Training” scored the highest in the “Accessibility” category. This metric could be especially useful for healthcare providers looking for information on how to obtain their DEA-X Waiver. For example, a healthcare provider can easily search using this keyword and navigate the website to obtain information such as the next waiver training date or steps that need to be completed in order to obtain a waiver. Ensuring that websites score high in the “Accessibility” category may pave the way for more healthcare providers to learn about the waiver process and obtain their DEA-X waiver.

The lowest scoring usability category among all of the keywords was “Marketing”. This finding is critical for OUD-related digital health organizations as it could mean that across all the keywords, websites were not easily found among top-search results when users used a search engine such as Google (based on the definition of this usability category described earlier).5 By investing in resources that promote websites such as through social media marketing, this usability metric can be improved.12 This may lead to a wider reach among the national target audience.

Comparison to prior work

This study includes methods that were replicated and modified from previous literature. As previously mentioned, a study by Wang et al. evaluated multiple search engines on their effectiveness.10 The study indicated that the Google Search engine had the best search validity and that it was effective in delivering health-information results.10 The outcomes of this study prompted us to develop a modified methodology centered around these results that utilized the Google Search engine to generate a list of OUD-related websites.10

In addition to the search methodology, website usability testing has been conducted in several studies as well. Most recently, a study looked at evaluating the usability of websites in the digital health centers space.5 Using the methodology developed by Calvano et al., we modified and applied the same usability testing criteria that was used for evaluating digital health centers, in order to evaluate OUD websites generated by the Google Search engine5

Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. Some of the concerns that arise involve accuracy of the search results based on the introduction of bias and personalized preference. There may have been unintended bias in what keywords were chosen to obtain the list of OUD websites.

Another limitation was based on the exclusion criteria of the search results. If the same website result was populated in more than one keyword search queries, it was manually excluded from the initial website compilation list (Multimedia Appendix 1: Compiled list of OUD websites using keyword methodology) and in the refined website list (Multimedia Appendix 2: Refined list of OUD websites using keyword methodology). This was an unfortunate limitation in the study as there was a possibility of error being introduced into the website exclusion list Similarly, in this study, irrelevancy was also subject to user discretion. This may have added unintended bias into the dataset based on what the user personally determines to be irrelevant to them.

Furthermore, another limitation would be that the search results obtained using Google Search could be impacted by regional and location differences of the user. For example, one user may obtain more relevant search results if his/her location and region have more OUD resources and tools compared to another user in a location where OUD resources are limited. Due to this reason, it was difficult to acquire a comprehensive list of search results that accounts for all these differences and unintended bias, which might have affected data acquisition and analysis. However, in our case, we referred to previous literature and methodologies to minimize bias as much as possible in order to generate a list of OUD websites. For future directions to address some of the search limitations, we may consider compiling an alternative list of websites to obtain more location-specific results. Using the same four keywords used in the study, we can perform Google Search from the highest OUD-stricken locations in the United States to give a more focused/relevant OUD website analysis.

As well, over the course of analysis, it was discovered that the usability analysis methodology utilized was susceptible to outliers in the metrics that skewed the overall website scoring, and thus, ranking. Websites with URLs closer to their root domain (e.g. www.getwaivered.com vs. www.getwaivered.com/subfolder/subfolder) naturally yielded higher values for backlink metrics and certain web pages that contained links to social media pages associated with their larger parent organizations registered significantly higher social media metrics (particularly skewing the “Marketing” and “Technology” usability scores). This was a notable limitation in the study and remains an important point for consideration in future modifications to the overall website usability analysis methodology, particularly with regards to the weight of certain metrics in contributing to usability scores.

The optimization and automation of the website usability analysis process is an ever pertinent objective given the rise of the role of online resources in the context of treating opioid-use disorder as well as healthcare at large. There were several usability metrics that proved to be obstacles in the efficient execution of usability testing and remain to be fully optimized and automated; chief among the metrics that emerged as limiting factors in efficient testing were those obtained through the Screaming Frog SEO Spider Web crawler application. While the Web crawler is an invaluable tool with its ability to crawl websites in versatile manners, some inflexibility was encountered in the context of automating the execution of and extraction of desired data from web crawls. Potential future updates to the methodology include the development of a coded script that will execute Screaming Frog crawls for URL lists with the necessary settings and specifications as well as extract the target data points for usability analysis; alternatively, the development of a customized web scraping tool specifically for the desired SEO metrics could serve to complete the optimization of this particular process. Also notable among the time-consuming processes in the usability analysis were metrics obtained from the Ahrefs tool as well as from social media outlets Facebook and Twitter; automation proved difficult without API access to these sources and optimization of this process could be addressed by purchase and use of the respective APIs.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the primary objectives of this study were addressed. A previously established usability testing methodology was adapted from previous literature and modified for the analysis of OUD websites, which led to important recommendations.5 It is important to note, however, that much progress is still needed with regards to further optimization of the website usability analysis process. Many sites included in this study do not update their interface regularly. If these sites performed regular audits and updates, then accessibility should improve. For example, to tackle the issue of marketing, sites could begin advertising online or promoting their content on social media to expand outreach. This, in turn, would benefit the site’s overall usability. Despite limitations, the application of the usability tools presented in this study may be used by digital health organizations in the OUD space to create effective, easily accessible, and accurate websites for all users. We believe that doing so may help to mitigate the opioid epidemic.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076221121529 for Analyzing opioid-use disorder websites in the United States: An optimized website usability study by Shuhan He, Saishravan Shyamsundar, Paul Chong, Jasmine Kannika, Joshua Calvano, Neha Balapa, Nick Kallenberg, Adarsh Balaji, Amala Ankem and Alister Martin in Digital Health

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts (FORE). The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies or stance, either expressed or implied, of FORE. FORE is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Foundation purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation hereon. The authors would also like to acknowledge Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Providers Clinical Support System (PCSS), American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), and the California Bridge Program for their continued support of our organization, Get Waivered, and our efforts to address the opioid epidemic.

Footnotes

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: SH Disclosure: Advisory Board: Covid Act Now, Safeter.App. Co-Founder: Cofounder, Executive Board Director GetUsPPE (unpaid), Co-Founder, Executive Board ConductScience Inc. Committees: American College of Emergency Physician Supply Chain Task Force. Research Funding: Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts (FORE). Personal Fees: Withings Inc., Boston Globe, American College of Emergency Physicians, MazeEngineers LLC, ConductScience Inc., Curative Medical Associates. No other disclosures are reported,

Contributorship: A.M. and S.H. conceived of the concept for this paper. S.H. designed the methodology, S.S. and P.C. oversaw the data collection and analysis. J.K., J.C., and N.B. A.A. performed data analyses. All authors reviewed the data analyses, provided critical feedback, advanced the concepts in the paper, and drafted the manuscript.

Ethical approval: This project was undertaken as a Quality Improvement Initiative at the Massachusetts General Hospital, and as such was not formally supervised by the Institutional Review Board per their policies. Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was funded by the Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts (FORE). The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies or stance, either expressed or implied, of FORE. FORE is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Foundation purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation hereon

Guarantor: Shuhan He.

ORCID iD: Adarsh Balaji https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5995-8115

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Trecki J. A perspective regarding the current state of the opioid epidemic. JAMA Netw Open 2019; 2: e187104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.“Understanding the Epidemic.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 19 Mar. 2020, www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html. Accessed June 16, 2021.

- 3.Alpay LL, Overberg RI, Zwetsloot-Schonk B. Empowering citizens in assessing health related websites: a driving factor for healthcare governance. Int J Healthc Technol Manag 2007; 8: 141 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke MA, Moore JL, Steege LM, et al. Health information needs, sources, and barriers of primary care patients to achieve patient-centered care: a literature review. Health Informatics J 2016; 22: 992–1016.. Epub 2015 Sep 15. PMID: 26377952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calvano JD, Fundingsland EL, Jr, Lai D, et al. Applying website rankings to digital health centers in the United States to assess public engagement: website usability study. JMIR Hum Factors 2021; 8: e20721.. PMID: 33779564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan SS, Goonawardene N. Internet health information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2017; 19: e9.. Published 2017 Jan 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hesse BW, Nelson DE, Kreps GL, et al. Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first health information national trends survey. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165: 2618–2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Husain I, Briggs B, Lefebvre C, et al. Fluctuation of public interest in COVID-19 in the United States: retrospective analysis of google trends search data. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2020; 6: e19969.. PMID: 32501806. PMCID: 7371405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scherr S, Haim M, Arendt F. Equal access to online information? Google‘s suicide-prevention disparities may amplify a global digital divide. New Media & Society 2019; 21: 562–582 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L, Wang J, Wang M, et al. Using internet search engines to obtain medical information: a comparative study. J Med Internet Res 2012; 14: 74.. PMID: 22672889. PMCID: PMC379956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huerta TR, Walker DM, Ford EW. An evaluation and ranking of children‘s hospital websites in the United States. J Med Internet Res 2016; 18: e228.. PMID: 27549074. PMCID: 5011553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schiro JL, Shan LC, Tatlow-Golden M, et al. #Healthy: smart digital food safety and nutrition communication strategies-a critical commentary. NPJ Sci Food 2020; 4: 14.. Published 2020 Oct 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076221121529 for Analyzing opioid-use disorder websites in the United States: An optimized website usability study by Shuhan He, Saishravan Shyamsundar, Paul Chong, Jasmine Kannika, Joshua Calvano, Neha Balapa, Nick Kallenberg, Adarsh Balaji, Amala Ankem and Alister Martin in Digital Health