Abstract

Patient decision aids can support shared decision making and improve decision quality. However, decision aids are not widely used in clinical practice due to multiple barriers. Integrating patient decision aids into the electronic health record (EHR) can increase their use by making them more clinically relevant, personalized, and actionable. In this article, we describe the procedures and considerations for integrating a patient decision aid into the EHR, based on the example of BREASTChoice, a decision aid for breast reconstruction after mastectomy. BREASTChoice’s unique features include 1) personalized risk prediction using clinical data from the EHR, 2) clinician- and patient-facing components, and 3) an interactive format. Integrating a decision aid with patient- and clinician-facing components plus interactive sections presents unique deployment issues. Based on this experience, we outline 5 key implementation recommendations: 1) engage all relevant stakeholders, including patients, clinicians, and informatics experts; 2) explicitly and continually map all persons and processes; 3) actively seek out pertinent institutional policies and procedures; 4) plan for integration to take longer than development of a stand-alone decision aid or one with static components; and 5) transfer knowledge about the software programming from one institution to another but expect local and context-specific changes. Integration of patient decision aids into the EHR is feasible and scalable but requires preparation for specific challenges and a flexible mindset focused on implementation.

Highlights

Integrating an interactive decision aid with patient- and clinician-facing components into the electronic health record could advance shared decision making but presents unique implementation challenges.

We successfully integrated a decision aid for breast reconstruction after mastectomy called BREASTChoice into the electronic health record.

Based on this experience, we offer these implementation recommendations: 1) engage relevant stakeholders, 2) explicitly and continually map persons and processes, 3) seek out institutional policies and procedures, 4) plan for it to take longer than for a stand-alone decision aid, and 5) transfer software programming from one site to another but expect local changes.

Keywords: breast reconstruction, decision aid, decision support, electronic health record, mastectomy, shared decision making

Patient decision aids support shared decision making (SDM) and are highly effective at improving the quality of decisions. Across numerous randomized controlled trials, patients who use decision aids have more knowledge, greater clarity about their values, less decisional conflict, and greater engagement in clinical conversations.1 Facilitators of decision aid use include evidence of better patient outcomes, co-production of decision aid content and processes, and local adaptation for end users.2,3 However, patient decision aids are not widely used in clinical practice due to multiple barriers, including time constraints, lack of clinician or patient awareness of them, and perceived lack of clinical relevance.4,5

One way to encourage SDM during the encounter is to integrate patient and clinician components of decision aids into the electronic health record (EHR) in ways that respect the 5 “rights” of clinical decision support. The 5 rights framework offers considerations for the implementation of EHR alerts, encouraging the provision of 1) the right information, 2) to the right person, 3) in the right intervention format, 4) through the right channel, and 5) at the right time in the workflow.6 Following these guidelines for EHR integration provides opportunities to address and evaluate potential barriers by automating the delivery process, personalizing information, and fitting decision aids into existing workflows.7 Many platforms and institutions support clinical decision support tools for clinicians (e.g., to alert them about patients’ eligibility for screening, vaccination, or to prompt them about clinical practice guidelines).8–11 Despite the potential advantages of EHR integration of patient decision aids, though, relatively limited evidence exists about how best to support their integration.12–14

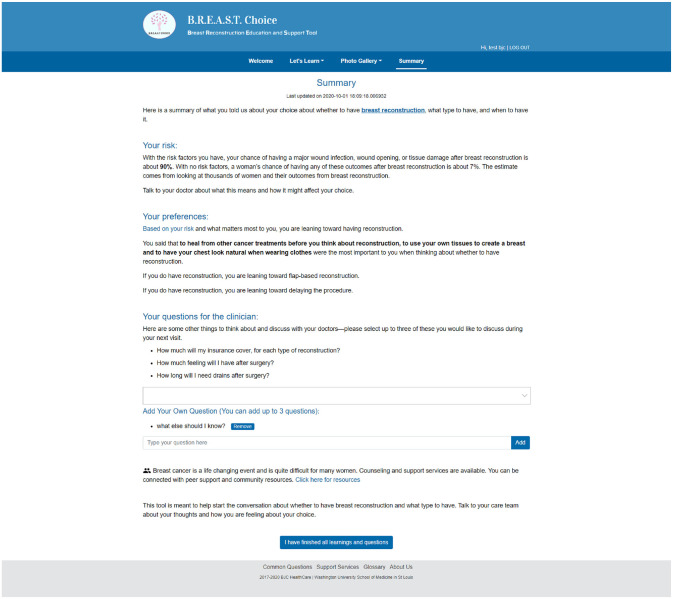

BREASTChoice is a decision aid designed to support both patient and clinician decision making about breast reconstruction after mastectomy. Breast reconstruction is a surgical procedure used to re-create the shape of a breast after mastectomy. The decision to undergo breast reconstruction can benefit from patient and clinician engagement because it is “preference sensitive”; that is, the choice depends greatly on the patient’s personal preferences.15 BREASTChoice was originally developed as a web-based decision aid hosted on a platform outside of the EHR (Figure 1). It was co-developed with formal stakeholder engagement of patients, surgeons, and nurses, and it underwent several iterations. Like all decision aids, BREASTChoice informs patients about the advantages and disadvantages of various options, helps them clarify their personal preferences, and prepares them to make a choice.16 It also incorporates separate patient- and clinician-facing components and a risk-prediction model that estimates the patient’s risk of a major surgical infection or wound complication. It delivers a summary of the patient’s personalized risk estimate, preferences, and questions for the patient to share with a surgeon (Figure 2). In a randomized controlled trial, an earlier version of BREASTChoice resulted in higher knowledge without adding to the encounter length, and patients and clinicians found BREASTChoice highly usable.16

Figure 1.

BREASTChoice welcome page.

Figure 2.

BREASTChoice summary page.

A major limitation of the original tool was that clinicians did not consistently know when patients had used it or what their risks and preferences were.17 Clinicians did not consistently view the patient summary because of the lack of integration into their workflow in the electronic medical record. Thus, we chose to integrate BREASTChoice into the electronic medical record for clinicians and the patient portal for patients. The goals were to 1) automatically incorporate patient risk factor data (including comorbidities and medications) from the EHR into BREASTChoice, 2) share the personalized risk information with patients via the patient-facing component of the decision aid, and 3) seamlessly deliver patients’ risk and preference information to clinicians electronically at the point of care.

This article describes our experience with integrating BREASTChoice into the EHR at 2 academic medical centers. The process posed unique challenges, particularly from an implementation perspective. The lessons learned may help to inform others about the challenges of deploying technology-based decision aids. We provide a case study of those challenges with specific examples from the BREASTChoice integration process. Recommendations are given for addressing each challenge, to inform future work and dissemination of decision aids. Recommendations 4 and 5 are related to the transfer of a build between sites, which is a particularly salient issue in the dissemination of decision aids using the EHR. For decision aids and other tools to reach a broad audience through EHRs, they have to be transferable between sites. Most of the recommendations are consistent with best practices of project management. However, informatics teams, clinical teams, and research teams often have different cultures, with unique languages, workflows, and languages, and they do not have a long history of working together. Thus, it is especially important for projects involving EHR integration to focus on clear and frequent communication, documentation, road maps, and resilience, in the face of barriers and challenges that inevitably arise.

Overview of EHR Integration of BREASTChoice

Integrating BREASTChoice into the EHR was part of a larger randomized study of the implementation of decision support for breast reconstruction.18 The EHR integration process involved 5 main steps and took approximately 18 mo to complete (Table 1). These steps included 1) stakeholder engagement about necessary modifications to the decision aid, 2) programming the modifications to the decision aid website, 3) institutional approval for EHR integration, 4) design of an EHR integration approach, and 5) programming of the decision aid software and its integration into the EHR, often referred to as the “build.” We took the approach of designing, programming, and implementing BREASTChoice at one site and transferring it to the second site, to minimize redundant effort and maximize future dissemination feasibility.

Table 1.

BREASTChoice EHR Integration Overview

| EHR Integration Step | Parties Involved | Approximate Time Required (Excluding Maintenance/Updates) |

|---|---|---|

| Obtain stakeholder feedback about the BREASTChoice tool | Study team | 6 mo |

| Modify/update the BREASTChoice tool based on feedback | Study team Research informatics team |

3 mo |

| Obtain institutional approvals for EHR integration | Study team Medical center informatics review committees |

3 to 6 mo |

| Design the approach to EHR integration of BREASTChoice | Medical center informatics team Research informatics team Epic staff Study team |

2 mo |

| Program and test the build for EHR integration of BREASTChoice | Research informatics team Medical center informatics team Study team |

6 mo |

EHR, electronic health record.

Several teams collaborated on these processes. Each site had a study team, which was involved in all procedures and facilitated stakeholder engagement and institutional approvals. Research informatics teams at each site led the design of an EHR integration approach. In addition, one of the sites also involved the medical center’s clinical informatics team and the EHR company’s (Epic) staff.

Transfer of data between the EHR and the BREASTChoice tool used Healthcare Level Seven (HL7) Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) standard Application Program Interfaces (APIs). HL7 FHIR is a standard for describing data, resources, and APIs for exchange of EHR information, using modern, web-based technologies. One site had BREASTChoice “pull” data from the EHR, and the other site had the EHR “push” data to the decision aid. Both sites used FHIR APIs to push patient-related data from BREASTChoice back into the EHR.

Challenges of EHR Integration, Recommendations, and Examples from BREASTChoice

We learned several important lessons and have developed recommendations to address the challenges we experienced, which are applicable to other decision aid EHR integration projects (Table 2).

Table 2.

Recommendations for Integrating a Decision Aid into the EHR

| Challenge | Recommendation | Example Solution from BREASTChoice |

|---|---|---|

| Unique and changing patient, clinician, and informatics needs and activities | Engage patient, clinician, and informatics stakeholders at all stages | Best practice alert (BPA) was developed to remind surgeons to view BREASTChoice summary at the start of clinic or just before the encounter. Patient receives portal message with link to tool when surgical appointment is scheduled. Patients can complete or edit their health data in case of inaccuracies or missing data. |

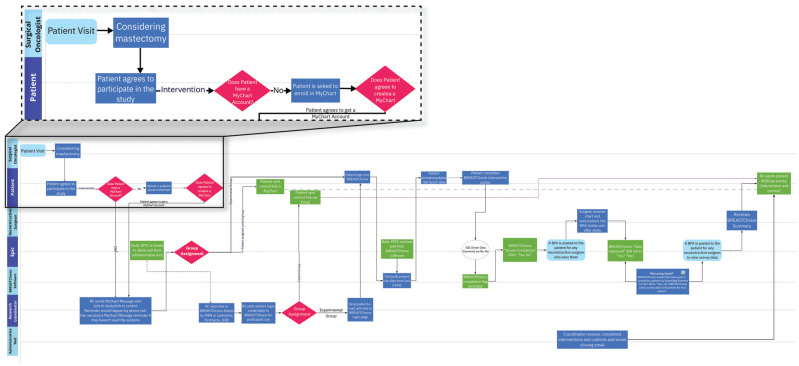

| Merging clinical workflow with informatics programming and involving multiple parties result in highly complex processes | Explicitly and continually map all clinical, research, and informatics processes | Swimlane diagram was used to map out timing, involved parties, and guide the EHR integration process (Figure 4) |

| Policies and procedures governing EHR integration of decision aids can be difficult to find and are institution specific | Actively seek out all policies and procedures regarding EHR integration before starting. Institutions could create an accessible website or repository with steps and contact personnel, much like policies and procedures available for investigators about IRBs. | One site allowed an external tool to “push” data to the EHR, while the other site required the clinician to authorize the EHR to “pull” data from the tool. |

| Because integrating a decision aid into the EHR is novel, institutions are still developing policies and procedures for implementation. | Plan for the process to take longer than development of a

stand-alone decision aid, CDS tool, or BPA; budget appropriately

with detailed processes and expected hours in

advance. Keep patient-facing components outside of the EHR, delivered through a patient portal or website, not integrated into the medical record. |

Regular meetings with the study team, medical center IT team, and research informatics team when building the integration |

| Local characteristics can complicate transferring a build between sites. | Transfer a build from another site, but plan for local changes. Track adaptations for future dissemination. | BREASTChoice had clear documentation and coding for Epic integration, which facilitated transfer. The second site developed a new approach to how data flowed from the EHR to BREASTChoice. |

CDS, clinical decision support; EHR, electronic health record; IRB, institutional review board; IT, information technology.

Challenge 1: Unique and Changing Patient, Clinician, and Informatics Needs and Activities

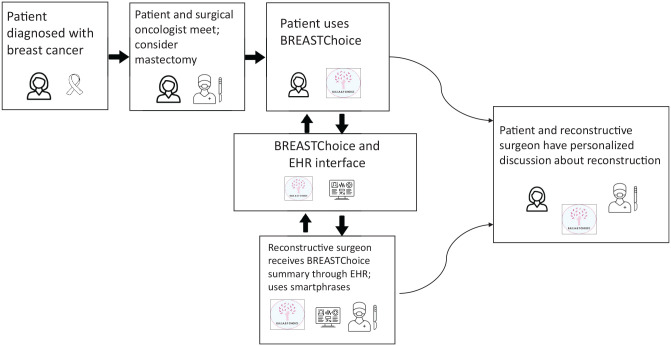

EHR integration of a patient- and clinician-facing decision aid requires careful consideration of clinical workflows, privacy, confidentiality, information accuracy, and stakeholder goals. The setting of use was important to our patient stakeholders who preferred to use BREASTChoice at home, rather than in the clinic. Clinician stakeholders expressed concern that EHR data on patient risk factors could be incomplete or inaccurate, which would subvert the availability of having the right information at the right time in the workflow.6 The timing of decision aid delivery is critical and may be complex. Patients must be identified as 1) eligible, 2) making a decision, and 3) aware of their diagnosis but ideally not yet through discussing treatment options with a clinician (Figure 3). BREASTChoice also had to be delivered to the correct reconstructive surgeon. Informatics stakeholders advised that the most important aspects of EHR integration would be the timing of transferring patient data from the EHR to BREASTChoice and then back into the EHR. Surgeons told us that they wanted to know whether their patient had used BREASTChoice before the visit. They also wanted to view the BREASTChoice summary early enough to use it in treatment decision making but not so early that they would forget it. Many surgeons wanted to receive an electronic reminder to view the BREASTChoice summary.

Figure 3.

Timing of delivery of BREASTChoice to patients and clinicians.

Recommendation 1: Engage Patient, Clinician, and Informatics Stakeholders at All Stages

We consulted stakeholders at the start of this project and throughout the EHR integration process. Specifically, we conducted semistructured interviews with 13 breast cancer survivors, 8 breast/general/surgical oncology clinicians, 6 reconstructive surgery clinicians, and 9 informatics experts. Interview questions were based on the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Details on this stakeholder engagement process and results have been published previously.17

To address the issue of proper timing, we leveraged the EHR’s ability to automatically track each discrete step in the clinical workflow. Patients received a notification through the EHR patient portal or through email if a patient was not enrolled in the patient portal. The notification triggered after the oncologic surgeon encounter but before the reconstructive surgeon encounter. Clinicians received a best practice alert (BPA), which launched after the patient completed BREASTChoice and contained the BREASTChoice summary with the patient’s risk estimate, preferences, and questions (Figure 2). This design allowed the informatics team to ensure that the alert provided 1) the right information, 2) to the right person, 3) at the right time in the workflow, per the five rights framework.6 These design decisions are being evaluated in the ongoing randomized controlled trial.

To address clinician concerns about accuracy, we designed BREASTChoice to give patients an opportunity to edit their risk data. For example, patients could delete, change, or add diagnoses or medications. To accommodate clinicians’ EHR documentation needs, we developed an EHR “smartphrase” (a short piece of text that pulls in a longer piece text into a note)19 specific to BREASTChoice. This allowed clinicians to specifically document that they used information from the BREASTChoice summary during the clinical encounter.

Challenge 2: Merging Clinical Workflow with Informatics Programming

Our earliest discussions with informatics teams focused on programming of the decision aid, where and how data would be stored, and how data would be transferred between BREASTChoice and the EHR. They did not explicitly make clinical workflow central to planning. Because clinical data from the EHR is so central to BREASTChoice’s design, many unresolved issues subsequently arose about clinical workflow and how it intersected with the flow of data and data security.

Recommendation 2: Explicitly and Continually Map All Clinical, Research, and Informatics Participants and Processes

We constructed a swimlane diagram20 to map all individuals, groups, structures, procedures, and timing that were involved in the clinical workflow and the use of BREASTChoice (Figure 4). The swimlane diagram served as a guide for the EHR integration process and as a communication tool among all parties involved. The medical center research informatics program at one of the sites has since required a swimlane diagram for all EHR integration projects. We recommend using process-mapping tools (e.g., swimlane, process flow diagrams, mind mapping) to explicitly communicate and document about the clinical workflow and its implications for EHR integration. These tools facilitate intentional planning by multiple responsible parties of simultaneous processes, some of which are dependent on each other and some of which are not. It allows for, but does not require, a depiction of the chronology of events and processes, including iterative or nested processes.

Figure 4.

Part of the swimlane diagram of clinical workflow and BREASTChoice use (Miro), with a portion magnified for illustration.

An example of the value of the swimlane diagram is determining when the patient-clinician relationship is “established,” which can affect decision support delivery timing. Many patient portals require that the patient-clinician relationship be established before the patient can contact the clinician via the portal or an external decision aid can send patient information to the clinician. That requirement ensures that information is routed to the correct clinician, to prevent its being overlooked or reaching the wrong person. When we used the swimlane diagram, we mapped out this decision point and created solutions for sending patients the BREASTChoice link via the patient portal and for sending clinicians the BREASTChoice summary using a BPA.

Challenge 3: Unclear Governance Policies and Procedures

A major issue for EHR integration of decision aids is that policies and procedures governing the process are often in flux or not yet established. They fall under the domains of legal, medical information management, compliance, and privacy/security offices. Thus, they may not be explicitly stated or straightforward to find. If study teams are not aware of all policies and procedures before proceeding with implementation, study processes can be delayed.

We encountered such a policy-related delay in managing the flow of data from BREASTChoice into the EHR. Because BREASTChoice includes a risk prediction model, clinical data must flow from the EHR to BREASTChoice and back into the EHR (Figure 3). While many decision aids extract data from EHRs, for example, those relying on FHIR to pull data from the record, the procedures for pulling data into the EHR are not as clear. At 1 of our 2 sites, an external tool is allowed to push patient information into the EHR flowsheet.19 In contrast, the second site does not allow an external decision aid to enter patient data into the EHR without the patient’s clinician allowing the EHR to pull those data from the aid. Because the first site had programmed BREASTChoice, the second site had to redesign this aspect of the build.19

Many institutions have governing committees that must approve EHR integration of decision aids. There may be separate committees and procedures for clinical and research projects, and the distinction between clinical versus research is not always clear. Some institutions also have a separate committee to approve BPAs. Furthermore, many institutions bundle the production of new EHR projects and will not allow completed builds to go live until scheduled dates. Knowing requirements ahead of time may enable the planning of parallel study processes to continue progress on one part of the project while waiting for approval on another. Such planning could be particularly important for adhering to a grant timeline.

Recommendation 3: Actively Seek out All Local Policies and Procedures Regarding EHR Integration before Starting

These experiences lead us to recommend that institutions develop a central, easy-to-identify repository for policies and procedures governing EHR integration projects. Such a resource could benefit many types of clinical decision support tools and not just decision aids. The repository ought to be available institution-wide and include procedures for its own updating and modification. Ideally, there would be personnel for its maintenance. Awareness of these policies and procedures by investigators should be comparable to the awareness of institutional review board requirements for human subjects research.

Challenge 4: Limited Experience with EHR Integration of Patient Decision Aids

Integrating a patient decision aid into the EHR is still novel, and institutions are developing policies and procedures for its implementation. The integration process, especially for a research study, can require different personnel, resources, and procedures than usual for decision aid development, EHR upgrades, stand-alone decision aids, or BPAs. Although an institution’s information technology department will already have personnel for clinical decision support, EHR integration of a patient decision aid and research about it require unique expertise. We found that our study was one of the first of such projects to be conducted at our institutions. This meant that it had potential value but that the informatics teams needed to investigate pertinent policies and procedures while working on the build for the study. We recommend determining the institution’s experience in EHR integration of patient decision aids and informatics research early in planning, including during grant development if applicable. If they do not, plan for processes to take longer, and budget accordingly.

Although our institutions’ new research informatics programs found the project important, their ability to devote personnel to the project was sometimes limited. One reason for this limitation was the project’s scope, affecting only breast cancer patients undergoing mastectomy (compared, for example, to a clinician-facing BPA for vaccination). Thus, if one person’s expertise was unavailable due to an absence or demand from another project, progress often paused. We found that such demands on informatics personnel were somewhat common, because urgent issues facing a medical center often require substantial informatics effort.

Recommendation 4: Plan for the Process to Take Longer Than Development of a Stand-Alone or Static Decision Aid, Clinical Decision Support Tool, or BPA

We recommend building in flexibility by planning parallel study processes, so that progress can continue on one process while another is delayed. We also found that because of the novelty of the project and its multiple stakeholder groups, effective communication modalities did not yet exist. Thus, we recommend explicit planning for both standing communication (e.g., a weekly multidisciplinary meeting) and ad hoc messaging (e.g., chat software, bug-tracking software). Alternatively, some might conclude that this build is too large and prefer that the patient-facing components remain outside of the EHR, such as through patient portal delivery or a website that is not integrated into the medical record. Those approaches could allow other sites to use the decision aid without needing to complete a local build.

Challenge 5: Local Characteristics Can Complicate Transferring a Build between Sites

We programmed BREASTChoice as a standalone website and designed the EHR integration to be somewhat generalizable. Effective adaptation from one site to the other relied on careful documentation of all programming by the first site and transferring this documentation to the second site. We used a coding repository for these purposes. It also relied on direct and regular communication between programmers from the 2 sites. Such communication was less needed after the first 3 mo of transferring to the second site but was still necessary on an ad hoc basis. Programming changes sometimes resulted in “downtime,” when patients could not access the tool, which resulted in some confusion among patients.

We had not budgeted for continued informatics involvement by the first site beyond the project’s reaching stability there. Also, because the different local policies about data flow and decision support timing required programming changes, we had to arrange for more funds and personnel for the informatics groups after initial EHR integration of BREASTChoice. Although the transfer of the build worked for our 2 planned academic sites, it was not feasible for a third planned site at a community hospital.

We recorded all changes to BREASTChoice using the expanded Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications (FRAME).21 This included FRAME process domains (modification timing, whether it was planned or not, who participated, modification content, modification nature) and reasons (goal of the modification, sociopolitical, organization/setting, provider, or recipient reasons). Tracking of modifications helped the transfer from the first site to the second and will support future dissemination of BREASTChoice.

Recommendation 5: Plan for Local Changes When Transferring a Build between Sites

To facilitate transferability of programming, we recommend clear documentation of all programming by the first site and a reliable coding repository and transfer procedures prior to agreement about extent of responsibility for programming by each site. We also recommend clear communication methods between teams about bugs and code updates and with patient participants when there is decision aid downtime related to code updates. Because informatics maintenance and adaptation occur beyond the point of the successful build, we recommend anticipating those needs when budgeting. Finally, we recommend using a tool such as FRAME to track all modifications.

Conclusion

EHR integration of a patient decision aid that 1) provides personalized risk estimates using EHR data, 2) faces both patients and clinicians, and 3) has an interactive design has the potential to enhance SDM and can be accomplished by planning for and addressing key challenges. These challenges include the need to accommodate many stakeholders with different priorities and workflows, variable and rapidly changing policies regarding EHR security, relative novelty of this process for most institutions, and the need to balance local requirements with future dissemination potential. When implementing the BREASTChoice decision aid into 2 EHR environments, we learned valuable lessons that can benefit other investigators: 1) engage all relevant stakeholders, 2) explicitly and continually map all persons and processes, 3) actively seek out all pertinent institutional policies and procedures, 4) plan for integration to take longer than development of a stand-alone decision aid, and 5) transfer knowledge about a build from one institution to another but expect local changes.

In addition to our 5 specific recommendations, we advise that investigators remain highly flexible and recognize that unforeseen obstacles and accompanying delays are part of the discovery and implementation process. Similarly, engage with all collaborators and stakeholders as they learn about the EHR integration process and develop their own best practices. For every obstacle, facilitator, or innovation, document all adaptations using a reliable theory-based implementation framework. Start the entire process early and build in parallel processes for presentations, approvals, modifications, and programming. Plan resource allocation and budgeting based on all of these processes, which may differ from what is customary for other types of research. Measure as many processes and outcomes as possible, including opinions of stakeholders, adaptations, usability, and adoption metrics. Although many of these practices are part of good project management, they become even more important for an EHR integration project, with new procedures and teams and complex technology and governance. Integration of decision aids into the EHR is feasible and scalable but requires preparation for specific challenges and a flexible mindset focused on implementation.

Future Directions

Efforts to integrate patient decision aids into the EHR are growing. Many of those efforts, however, have focused on 1 or a few components of SDM, rather than the entire process, and relatively few studies have fully leveraged the automation available with the EHR, such as through delivery of personalized information.12 Our randomized controlled trial is testing the effects of the EHR-integrated BREASTChoice, with its personalized risk estimates, on patient and clinician behaviors. EHRs have not been designed with SDM in mind and can therefore become an additional barrier to the process. Research is needed on ways to redesign the EHR to optimally support SDM.14 For example, a patient’s preferences could be elicited by and stored within the EHR, along with other health data, which could then be communicated automatically to the clinician. Methods are needed for alerting clinicians without causing alert fatigue and in ways that fit into clinicians’ mindsets and habits.22 Future implementation research should leverage the EHR to encourage and enhance the use of patient decision aids in clinical practice, ultimately leading to more effective application of SDM at the point of care.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients, clinicians, and informatics experts who participated in this study.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Financial support for this study was provided in part by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and in part by internal funding from The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center. The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing, and publishing the report.

Authors’ Note: The authors adhere to best practices of research transparency. Data, analytical methods, and other research materials are available upon request to Dr. Lee.

ORCID iDs: Clara N. Lee  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0514-9448

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0514-9448

Janessa Sullivan  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1095-6412

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1095-6412

Margaret A. Olsen  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7070-9320

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7070-9320

Jessica Boateng  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0393-7897

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0393-7897

Contributor Information

Clara N. Lee, Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, College of Medicine, Division of Health Services Management and Policy, College of Public Health, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA; OSU Comprehensive Cancer Center; The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA.

Janessa Sullivan, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USA.

Randi Foraker, Division of General Medical Sciences, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USA.

Terence M. Myckatyn, Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USA Division of General Medical Sciences, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USA.

Margaret A. Olsen, Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USA Department of Family and Community Medicine, Department of Biomedical Informatics, College of Medicine, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA.

Crystal Phommasathit, OSU Comprehensive Cancer Center; The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA.

Jessica Boateng, Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USA.

Katelyn L. Parrish, Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USA

Milisa Rizer, Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USA.

Tim Huerta, Department of Biomedical Informatics, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USA.

Mary C. Politi, Division of Public Health Sciences, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, Saint Louis, MO, USA

References

- 1. Stacey D, Legare F, Lewis K, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Joseph-Williams N, Abhyankar P, Boland L, et al. What works in implementing patient decision aids in routine clinical settings? A rapid realist review and update from the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration. Med Decis Making. 2021;41(7):907–37. DOI: 10.1177/0272989x20978208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Scholl I, LaRussa A, Hahlweg P, et al. Organizational- and system-level characteristics that influence implementation of shared decision-making and strategies to address them—a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2018;13:40. DOI: 10.1186/s13012-018-0731-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A. Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94:291–309. DOI: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Légaré F, Witteman HO. Shared decision making: examining key elements and barriers to adoption into routine clinical practice. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:276–84. DOI: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sirajuddin AM, Osheroff JA, Sittig DF, et al. Implementation pearls from a new guidebook on improving medication use and outcomes with clinical decision support. Effective CDS is essential for addressing healthcare performance improvement imperatives. J Healthc Inf Manag. 2009;23:38–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kuo AM, Thavalathil B, Elwyn G, et al. The promise of electronic health records to promote shared decision making: a narrative review and a look ahead. Med Decis Making. 2018;38:1040–5. DOI: 10.1177/0272989x18796223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sutton RT, Pincock D, Baumgart DC, et al. An overview of clinical decision support systems: benefits, risks, and strategies for success. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:17. DOI: 10.1038/s41746-020-0221-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kubben P, Dumontier M, Dekker A. Fundamentals of Clinical Data Science. New York: Springer International; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McGinn TG, McCullagh L, Kannry J, et al. Efficacy of an evidence-based clinical decision support in primary care practices: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1584–91. DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.8980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patterson BW, Pulia MS, Ravi S, et al. Scope and influence of electronic health record–integrated clinical decision support in the emergency department: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;74:285–96. DOI: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.10.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davis S, Roudsari A, Raworth R, et al. Shared decision-making using personal health record technology: a scoping review at the crossroads. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24:857–66. DOI: 10.1093/jamia/ocw172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Day FC, Pourhomayoun M, Keeves D, et al. Feasibility study of an EHR-integrated mobile shared decision making application. Int J Med Inform. 2019;124:24–30. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2019.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lenert L, Dunlea R, Del Fiol G, et al. A model to support shared decision making in electronic health records systems. Med Decis Making. 2014;34:987–95. DOI: 10.1177/0272989x14550102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Myckatyn TM, Parikh RP, Lee C, et al. Challenges and solutions for the implementation of shared decision-making in breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8:e2645. DOI: 10.1097/gox.0000000000002645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Politi MC, Lee CN, Philpott-Streiff SE, et al. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the BREASTChoice tool for personalized decision support about breast reconstruction after mastectomy. Ann Surg. 2020;271:230–7. DOI: 10.1097/sla.0000000000003444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boateng J, Lee CN, Foraker RE, et al. Implementing an electronic clinical decision support tool into routine care: a qualitative study of stakeholders’ perceptions of a post-mastectomy breast reconstruction tool. MDM Policy Pract. 2021;6:23814683211042010. DOI: 10.1177/23814683211042010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clinicaltrials.gov. Implementing BREASTChoice into practice, Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04491591

- 19. Epic. Epic SmartForm guide. 2021. Available from: https://www.getepichelp.com/guides/epic-smartform-guide. Accessed August 21, 2021.

- 20. Rummler GA, Brache A. Improving Performance: How to Manage the White Space on the Organization Chart. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wiltsey Stirman S, Baumann AA, Miller CJ. The FRAME: an expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implement Sci. 2019;14:58. DOI: 10.1186/s13012-019-0898-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Horsky J, Phansalkar S, Desai A, et al. Design of decision support interventions for medication prescribing. Int J Med Inform. 2013;82:492–503. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2013.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]