Abstract

Gardnerella overgrowth is the primary cause of bacterial vaginosis (BV), a common vaginal infection with incidences as high as 23–29% worldwide. Here, we studied the pathogenicity, drug resistance, and prevalence of varying Gardnerella spp. We isolated 20 Gardnerella strains from vaginal samples of 31 women in local China. Ten strains were then selected via phylogenetic analysis of cpn60 and vly gene sequences to carry out genome sequencing and comparative genomic analysis. Biofilm-formation, sialidase, and antibiotic resistance activities of the strains were characterized. All strains showed striking heterogeneity in genomic structure, biofilm formation and drug resistance. Two of the ten strains, JNFY3 and JNFY15, were classified as Gardnerella swidsinskii and Gardnerella piotii, respectively, according to their phenotypic characteristics and genome sequences. In particular, seven out of the ten strains exhibited super resistance (≥ 128 μg/mL) to metronidazole, which is the first line of treatment for BV in China. Based on the biochemical and genomic results of the strains, we proposed a treatment protocol of prevalent Gardnerella strains in local China, which provides the basis for accurate diagnosis and therapy.

Keywords: Gardnerella vaginalis, prevalent strains, comparative genomics, antibiotic resistance, accurate diagnosis and therapy

Introduction

Gardnerella vaginalis is a facultatively anaerobic bacterium of the Bifidobacteriaceae family and part of the normal vaginal microbiome. Often described as a Gram variable organism with a Gram-positive wall type, the genome size of the type strain ATCC 14018 is remarkably small compared to other facultative anaerobes (Greenwood and Pickett, 1980). At only 1.6 M, it is one-third and one-fifth that of E. coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, respectively. In addition, no plasmids nor phages have been characterized in any identified strains thus far (Yeoman et al., 2010). As such, the metabolic pathway of G. vaginalis is also relatively simple, with only succinic acid dehydrogenase and malate dehydrogenase remaining in the TCA cycle (Greenwood and Pickett, 1980).

As a conditional pathogen, G. vaginalis has a very simple cell signaling system and a relatively rich virulence system, which leads to differences in pathogenicity amongst various strains. The type strain, for example, does not contain signaling molecules such as c-di-NMP and cNMP (He et al., 2016), thus lacking the second messenger system of cyclic nucleotides commonly used in most strains. It only has six pairs of two-component systems (TCS), which is rather simple compared to the 130 pairs of TCS in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Francis et al., 2017). Regarding the virulence system, strain ATCC 14019 has no typical secretory system (Hood et al., 2010) and does not contain flagella, and its adhesion to the epithelial cell mainly relies on type I and type II pili (Punsalang and Sawyer, 1973). It secretes vaginolysin, a cholesterol-dependent cytotoxin (Rottini et al., 1990; Gelber et al., 2008). As for other genes associated with pathogenicity, it has two high-affinity iron transporters and is resistant to bleomycin, methicillin and lanthionine antibiotics (Berger-Bachi et al., 1989; Jarosik et al., 1998). The mechanism of immune escape mainly involves changing the molecular weight of its surface antigen (Lindahl et al., 2005). Previously, it has been observed that G. vaginalis can form a dense biofilm structure and stick to the surface of the vaginal epithelial cells, resulting in stubborn drug resistance (McGregor and French, 2000; Workowski et al., 2010; Rosca et al., 2020).

Although G. vaginalis commonly occurs in the vaginal microbiota of healthy individuals (Fredricks et al., 2005; Hyman et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2009), it is also one of the most frequent and predominant vaginal tract colonists in women diagnosed with bacterial vaginosis (BV) (Fredricks et al., 2005; Menard et al., 2010; Patterson et al., 2010). BV is the most common bacterial inflammatory reproductive tract disease amongst females of reproductive age, with incidence rates as high as 23–29% worldwide (Peebles et al., 2019). BV results in a range of symptoms such as vaginal itching, odor, and abnormal vaginal discharge, and it is caused by the disruption of the dynamic balance between the bacterial microflora in the vagina, the host, and the environment. This involves the overgrowth of various anaerobic bacteria in the vaginal microbiome relative to Lactobacilli, with G. vaginalis overgrowth in particular being implicated in the formation of a stubborn biofilm that is indicative of BV (Anahtar et al., 2018; Rosca et al., 2020). This biofilm can adhere to the vaginal epithelium, forming clue cells for the diagnostic basis of BV (Swidsinski et al., 2005). Additionally, G. vaginalis infections have been associated with various clinical presentations. Many G. vaginalis infections can cause pelvic inflammatory disease, salpingitis, infertility, and gynecological tumors. G. vaginalis infections have also been associated with adverse outcomes in pregnancy—incidences of premature rupture of membranes, premature delivery and intrauterine infection were 25, 31.67, and 32%, respectively, which were significantly higher than those in normal pregnant women (Cauci et al., 2008; Gelber et al., 2008; Fettweis et al., 2019).

In recent years, comparative genomics studies on G. vaginalis have emerged. Whole genome DNA-DNA hybridization of vaginal samples from women presenting varying phenotypes led to a reclassification of several G. vaginalis strains (UGent 06.41, UGent 18.01, GS9838-1). These strains have been reclassified to G. leopoldii, G. piotii, and G. swidsinskii, respectively (Vaneechoutte et al., 2019). Further genome sequencing and comparative analyses of three G. vaginalis strains (ATCC 14018, ATCC 14019, and 409-05) showed the high genetic diversity of this species, with only 846 genes out of more than 1,300 genes in the genome being identical. All three strains are able to thrive in vaginal environments, thus allowing the BV isolates ATCC 14018 and 14019 to occupy a niche that is unique from 409-05. Each strain has significant virulence potential, although genomic and metabolic differences, such as the ability to degrade mucin, indicate that the detection of G. vaginalis in the vaginal tract provides only partial information on the physiological potential of the organism (Yeoman et al., 2010). Comparative genomic analyses of strains 5-1 (from healthy hosts) and AMD (from bacterial vaginosis) showed that the copy number and amino acid sequence of vaginolysin in these two strains were almost identical, with only one amino acid difference. Strain AMD contains more toxin-antitoxin (TA) systems; Strain 5-1 lacks two key adhesion proteins, Rib, significantly reduced ability to adhere to epithelial cells, and is more sensitive to erythromycin, leading to weakened pathogenicity (Harwich et al., 2010). All these studies have provided a solid basis for the development of novel diagnostics and treatments against Gardnerella infections. However, given the high heterogenicity of Gardnerella, and the large population with high BV infection rates in China, the lack of in-depth research on varying Gardnerella strains poses a concern for the treatment of patients in China.

Therefore, this study investigates ten epidemic strains of Gardnerella in local China. First, we used molecular biology and biochemistry techniques to classify and determine the epidemic percentage of each subtype. Then, we analyzed both common and unique pathogenic genes of different Gardnerella strains through comparative genomics. Based on these results, we constructed a database of epidemic Gardnerella strains in local China, which may act as a foundation for developing accurate diagnostics and therapeutics for Gardnerella-induced BV.

Materials and methods

Selection of patients

Samples were obtained from 31 women who attended private gynecology clinics in Jinan Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital, China. The study was approved by the Jinan Health Committee (approval no. 2019-1-25). Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants prior to enrollment. All were Han Chinese > 18 years of age (range, 21–55 years; mean, 31.2 years). All had come to the clinic for a routine gynecological examination, with self-reported complaints of vaginal itching/burning sensations, or with increased and/or malodorous vaginal discharge. All participants were asked to complete a questionnaire on the current use of hormonal contraceptives, menstrual cycle, and frequency of vaginal infections. Exclusion criteria included menstruation at the time of enrollment, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, and antibiotic/antimicrobial treatment within 14 days of sampling.

Examination of vaginal samples, Gardnerella vaginalis isolation

All samples were subjected to Gram-staining and microscopy to assess their Nugent score (NS) (Nugent et al., 1991). BV diagnosis was also defined by the clinician. BV diagnosis included the mandatory satisfaction of three out of the four Amsel criteria (elevated pH, clue cells, fishy odor, and characteristic vaginal discharge); this was supplemented by chemical analysis results (H2O2 concentration, activity of leucocyte esterase, sialidase, coagulase and beta-glucosidase) (Amsel et al., 1983; Workowski et al., 2010). A sample was considered as BV-positive if the NS ranged from 7 to 10 and at least three Amsel criteria were present (Workowski et al., 2010). In the case of any inconsistency between the results of chemical analysis and morphology, it should be subjected to morphology. For G. vaginalis isolation, a swab taken near mid-vagina was placed in a BHI liquid medium and then the 10 × gradient dilution was spread on a Chocolate Agar Medium (Haibo, Qingdao, China). Chocolate agar plates were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 48 h. Colonies of G. vaginalis were identified as described previously (Pleckaityte et al., 2012).

Growth condition

Planktonic cells were grown in sBHI [Brain-heart infusion supplemented with 2% (wt/wt) gelatin (Aladdin, Shanghai, China), 0.5% (wt/wt) yeast extract (Oxford, UK), 0.1% (wt/wt) glucose and 0.1% (wt/wt) soluble starch (Aladdin, Shanghai, China)] for 24 h at 37°C with 5% CO2. For biofilm formation, the glucose was replaced by maltose, and 5% (v/v) goat blood was added. 2% mid-log phase seed was inoculated to a fresh medium for the following tests.

Gene-specific PCR assays and phylogeny construction

Gardnerella vaginalis identification was confirmed by PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene (Rainey et al., 1996) and sequencing of the obtained PCR product. G. vaginalis subtypes were classified through phylogenetic tree construction using cpn60 and vly gene sequences according to previous studies (Janulaitiene et al., 2017, 2018). The primers are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Sialidase assay

To further characterize the virulence factors of Gardnerella clinical isolates, we investigated the presence and expression of the sialidase gene. The presence of the sialidase gene in clinical isolates of Gardnerella was identified by PCR using specific primers (Supplementary Table 1). In addition, The Gardnerella cultures were diluted to an OD600 value of 0.8 with 50 mM MES buffer (pH 5.5). The reaction system contained 2.2 mM NBT (Nitrotetrazolium Blue chloride, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 146 mM sucrose, 10.5 mM MgCl2, 6.3 mM BCIN (5-Bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl α-D-N-acetylneuraminic acid sodium salt, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), with 0.5% sulfonyl 440 added to avoid bubbles. The mixture was then incubated at 37°C for 20 min and 100 μL of the incubated mixture was added to the wells of black polystyrene microplates (Nunc, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The plates were sealed with an optically clear seal, and BCIN hydrolysis was monitored by measuring the fluorescence at a wavelength of 616 nm using a SynergyH4 hybrid multi-mode microplate reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT, USA) (Zhang and Rochefort, 2013; Janulaitiene et al., 2018). The fluorescence of each supernatant was analyzed in triplicate.

Biofilm assay

For biofilm formation, the cell concentration of 24 h-old cultures was assessed by measuring the optical density of the cultures at 600 nm (Model Sunrise, Tecan, Switzerland). The cultures were further diluted to obtain a final concentration of approximately 106 CFU/mL. After homogenization, 200 μL of G. vaginalis suspensions were dispensed into each well of three 96-well flat-bottom tissue culture plates (Orange Scientific, Braine L’Alleud, Belgium). The tissue culture plates were incubated at 37°C in 10% CO2. After 24 h, the culture medium covering the biofilm was removed, then replaced by fresh sBHI and allowed to grow under the same conditions for an additional 24 h. The biofilm produced was quantified by crystal violet staining and then scanned at OD 570 (Jayaprakash et al., 2012; Janulaitiene et al., 2018).

Antibiotic resistance

All antibiotic reserve fluids were prepared at a concentration of 5,120 μg/mL, filtered by a filter membrane to ensure sterility, and stored separately at –20°C. The final antimicrobial concentration was obtained by double dilution with sBHI broth, which was diluted to 512, 256, 128, 64, 32, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1, 0.5, 0.25, and 0.125 μg/mL, respectively. The microdilution plate was made of a 96-well plate with 100 μL of prepared working fluid added to each well. At least one well containing only 100 μL of the antimicrobial-free broth was used as a growth control for the test strain. At the same time, at least one well containing only 100 μL of antimicrobial-free broth was used as an unvaccinated negative control well. Three to five colonies were selected from the blood plate medium with a sterile inoculation loop and placed in a sBHI liquid medium. The broth was incubated at 37°C, until it reached a turbidity of at least 0.5 McFarland (spectrophotometer 625 nm wavelength, 1 cm path, absorption rate 0.08–0.13). To maintain the stability of the cell concentration in the inoculation suspension, the microdilution plate must be inoculated within 30 min after preparation of the inoculation suspension. In the microdilution plate containing 100 μL of diluted antimicrobial agents, 5 μL of cell suspension was added to each well so that the number of cells in each well was approximately 5 × 105 CFU/mL. The microdilution plate was placed in an incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 18 ± 2 h. When the bacteria in the growth control hole had sufficient growth and the negative control hole without inoculation did not grow, MIC was determined as the minimum drug concentration that could significantly inhibit bacterial growth (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2020a,b).

Genome sequencing

The strains were cultured to the middle and late logarithmic stage, and cells were collected. The QIAGEN Genomic DNA extraction kit (QIAGEN, Dusseldorf, Germany) was used for Genomic DNA extraction of the samples according to the standard operating procedure provided by the manufacturer. The extracted genomic DNA was determined with the NanoDrop One UV-vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA). OD260/280 was within 1.8–2.0, and OD 260/230 was between 2.0 and 2.2. DNA was subsequently quantified using the Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, California, USA).

After quality inspection, the Blue Pippin automatic nucleic acid recycling instrument (Sage Science, Massachusetts, USA) was used to cut and recycle large fragments. Then, the connectors in the LSK108 linking kit (Oxford, UK) were used for the linkage reaction. Finally, the Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, California, USA) was used for accurate quantitative testing of the established DNA libraries. After completion of database construction, a DNA library of a certain concentration and volume was added into one flow cell, and the flow cell was transferred to the Nanopore GridION X5 (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK) for real-time single-molecule sequencing.

Genome analysis and phylogenomic tree construction of Gardnerella taxon

After quality control, the data was assembled with CANU1 and corrected with PILON (Walker et al., 2014) combined with second-generation sequencing data. The corrected genome uses its own script to detect whether it is ringed or not. After the redundant parts are removed, the origin of the ringed sequence is moved to the replication starting site of the genome with Circlator (parameter: Fixstart) to obtain the final genome sequence.

The coding gene was predicted by Prodigal2 and the complete CDS was retained. The tRNA gene was predicted by Transcan-SE, and the rRNA gene was predicted by RNAmmer. Other ncRNA searched the RFAM database for predictions using Infernal, retaining the predicted length (Kalvari et al., 2020). CRISPR was predicted with MinCED (Bland et al., 2007) and Islander was predicted with IslandViewer.3

Genome-encoded proteins were extracted and annotated with InterPro4 to extract annotation information from TIGRFAMs, Pfam and GO databases. Blastp was used to compare the coded proteins to KEGG and Refseq databases, and the best result of the comparison coverage > 30% was kept as the annotation result. The encoding protein was compared with the COG database for COG annotation by RPSBLAST. ABRicate could obtain resistance genes from contig, which correlated with databases such as NCBI, CARD [The Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (mcmaster.ca)] and ARG-Annot (Gupta et al., 2014). ABRicate software was also used to predict the resistance genes in the genome. Sequencing strain genes were compared with the Pathogenic Bacteria Virulence factor database (VFDB).5 The VFDB database, developed by the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, is widely used in the identification of virulence factor genes. VFDB collected the sequence information of bacterial virulence genes from 30 genera (74 pathogens). The bacterial genes were predicted using AntiSMASH.6 AntiSMASH used a rules-based clustering method to identify 45 different types of secondary metabolite biosynthesis pathways through its core biosynthesis enzyme.

To assess genome differences between Gardnerella strains, a phylogenetic analysis involving 22 genome sequences retrieved from NCBI and our data was performed. For this purpose, the genome sequences were aligned using MAFFT, and the phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method in Clustal W v2.1; the image was produced using FigTree software.7

Results

Collection and phylogenetic analysis of Gardnerella isolates

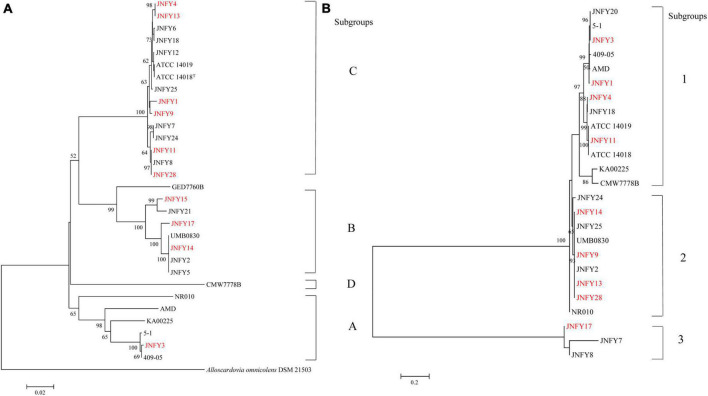

Twenty Gardnerella clinical strains were isolated from characterized vaginal samples of 31 women in local China. Each plate was inoculated from a single vaginal swab. Gardnerella strains were identified as described in Methods. Isolates from individual colonies were then subtyped by clade-specific PCR. Based on cpn60 gene sequences, 13 isolates were defined as belonging to clade C, six isolates belonged to clade B, and one isolate belonged to clade A. We found no Gardnerella strains belonging to clade D (Figure 1A). Two isolates (JNFY3 and JNFY13) originated from vaginal samples with normal vaginal microflora (NS = 1 and 0, respectively), whereas the other 29 vaginal swabs with NS values ranging from 4-10 (Table 1). The 20 Gardnerella clinical strains were divided into four clades based on their vly gene sequences (Figure 1B), and strains without the vly gene (JNFY15 and JNFY21) were classified as subtype 4.

FIGURE 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of Gardnerella strains based on cpn60(a) and vly(b) sequences. (A) Phylogenetic tree of Gardnerella cpn60 sequences comprising four distinct clades: (A–D). Bootstrap values for each node are indicated. ATCC 14018T, ATCC 14019, 41V, 101, 1500E, AMD, 409-05, JCP8066, and JCP7719 are G. vaginalis isolates with whole genome sequence information available in Genbank (Accession numbers ADNB00000000, CP002104, AEJE00000000, AEJD00000000, GCA_000263595, ADAM00000000, CP001849, GCA_000414565, and GCA_000414625, respectively). (B) Phylogenetic tree of Gardnerella vly sequences comprising four distinct clades: 1, 2, 3, and 4 (no vly gene).

TABLE 1.

Polyphasic comparison of the Gardnerella strains.

| Strains | Nugent score | Biofilm intensity | Phylogenetic subgroups | to Mid-log phase (h) | Sialidase activity | Vaginolysin-encoding gene | Antibiotic resistance genes | MID = 16 μ g/ml |

| ATCC 14019 | ND | 1.69 | C1 | 10 h | ND | + | lsaC | GM, TO |

| JNFY1 | 4 | 1.42 | C1 | 14 h | 0.29±0.009 | + | ermX, lsaC | CIP, TO, MTZ |

| JNFY3 | 1 | 0.48 | A1 | 8 h | ND | + | ermX | AZM, CIP, GM, TO, MTZ |

| JNFY4 | 8 | 1.06 | C1 | 9 h | ND | + | ermX, lsaC, tetL, tetM | AZM, TE, CIP, GM, ERM, TO, CLI, MTZ |

| JNFY9 | 7 | 1.03 | C2 | 15 h | ND | + | ermX, lsaC, tetL, tetM | TE, CIP, TO |

| JNFY11 | 8 | 1.29 | C1 | 10 h | ND | + | ermX, lsaC | CLI, CIP, TO, AZM |

| JNFY13 | 0 | 1.1 | C2 | 12 h | ND | + | lsaC, tetL, tetM | GM, TE, TO, MTZ |

| JNFY14 | 8 | 2.57 | B2 | 11 h | 0.38±0.008 | + | 2*lsaC | CIP, GM, TO, MTZ |

| JNFY15 | 8 | 0.59 | B4 | 20 h | ND | - | ermX, lsaC | CIP, GM, ERM, CLI, TO |

| JNFY17 | 4 | 0.52 | B3 | 13 h | 0.27±0.014 | + | lsaC | CIP, GM, TO, MTZ |

| JNFY28 | 8 | 1.13 | C2 | 14 h | ND | + | lsaC | GM, DNR, TO, MTZ |

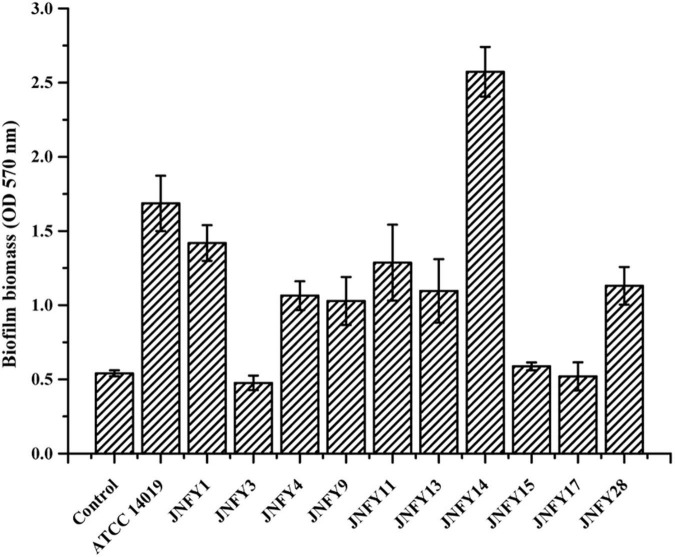

Biofilm, biomass, and sialidase activity in Gardnerella strains

The measurement of biofilm formation capacity of 10 strains showed that, except for JNFY3, JNFY15, and JNFY17, other prevalent strains could form biofilm with varied thickness. JNFY14 produced the largest amount of biofilm, and cpn60 subtype C prevalent strains generally formed a certain amount of biofilm (Table 1, Figure 2, and Supplementary Figure 2). Sialidase activity was detected in strains JNFY3, JNFY4, JNFY11, and JNFY17. Moreover, strain JNFY14 exhibited weak sialidase activity (Table 1).

FIGURE 2.

Biofilm formation by Gardnerella strains. Isolates were cultured in 96-well plate in BHI medium, stained at 48 h, after removal of planktonic cells.

General genome features and phylogenomic tree of Gardnerella strains

The genome size of Gardnerella was between 1.5 and 1.8 Mb, which was smaller than other members of the Bifidobacteriaceae family, one-third the size of E. coli and one-fifth the size of P. aeruginosa. The genomes of these ten strains contained about 1,300 genes, with a GC content of about 41–43%. The basic features of the ten prevalent GV strains were similar to those of the American strain ATCC 14019 isolated from BV patients (genome size 1,667,350 bp, GC content 41%). No obvious plasmid sequence was found in any of the ten strains. One genomic island was predicted in JNFY1, JNFY11, and JNFY17, and two genomic islands were predicted in JNFY3. No genomic island was predicted in other strains. A CRISPR sequence was predicted in JNFY1, JNFY3, JNFY4, JNFY13, and JNFY28, but not in other prevalent strains (Table 2). The phylogenomic tree showed that the Gardnerella strains were generally divided into four groups, which was similar to the cpn60 phylogenetic tree (Figure 1A). Strains JNFY1, 4, 9, 11, 13, 28, and ATCC 14019 were located in the same group in both trees; likewise, strains 409-05, JNFY3, 5-1, and JNFY15, 17, UMB0830 located to the same groups. Strains JNFY3 and JNFY15 were classified as Gardnerella swidsinskii and Gardnerella piotii, respectively, according to their genome sequences (Supplementary Figure 1). On the basis of the distance from the position of each strain to the root of the phylogenomic tree (Supplementary Figure 1), we calculated that the evolutionary order of each strain is as follows: ATCC 14018, JNFY3, 409-05, 5-1, JNFY14, JNFY15, JNFY17, JNFY4, JNFY11, JNFY9, JNFY13, JNFY1, and ATCC 14019.

TABLE 2.

The general features of the 10 Gardnerella genomes.

| Strains | Size (bp) | CDS number | Plasmid | Island | GC % | tRNA | rRNA | CRISPR | Accession No. |

| JNFY1 | 1,711,437 | 1,316 | NO | 1 | 41.61 | 45 | 6 | 1 | CP083177 |

| JNFY3 | 1,602,355 | 1,245 | NO | 2 | 42.02 | 45 | 6 | 1 | CP083176 |

| JNFY4 | 1,742,450 | 1,359 | NO | NO | 41.56 | 45 | 6 | 1 | CP083175 |

| JNFY9 | 1,640,523 | 1,243 | NO | NO | 41.41 | 45 | 6 | NO | CP083174 |

| JNFY11 | 1,743,456 | 1,357 | NO | 1 | 41.82 | 45 | 6 | NO | CP083173 |

| JNFY13 | 1,682,566 | 1,290 | NO | NO | 41.64 | 45 | 6 | 1 | CP083172 |

| JNFY14 | 1,680,963 | 1,290 | NO | NO | 41.67 | 45 | 6 | NO | CP083171 |

| JNFY15 | 1,541,442 | 1,164 | NO | NO | 42.55 | 45 | 6 | NO | CP083170 |

| JNFY17 | 1,595,814 | 1,236 | NO | 1 | 42.74 | 45 | 6 | NO | CP083169 |

| JNFY28 | 1,542,082 | 1,392 | NO | NO | 42.23 | 45 | 6 | 1 | CP083168 |

Carbohydrate transport and metabolism

In general, biofilm formation is tightly related to carbohydrate transport and metabolism. Compared with the biofilm-rich strain JNFY14, the biofilm-lacking strains JNFY3, JNFY15, JNFY17, and JNFY28 lacked many genes involved in polysaccharides synthesis and sugar transport. Absent genes included afuC, araD, fucP, galM, galT, lacZ, mglA, xylB, and xylF. In addition, there were fewer copies of nagC, ugpA, ugpB, and ugpE in biofilm-lacking strains, compared to the biofilm-rich strain JNFY14 (Supplementary Table 2). The absence and reduced copy numbers of these genes may explain why the strains of this group cannot form normal biofilm.

Antibiotic resistance

According to the genomic data, all of the ten Gardnerella isolates contained antibiotic resistance genes, with a total of four detected antibiotic resistance genes. JNFY1, JNFY3, JNFY4, JNFY9, JNFY11, and JNFY15 contained the macrolide erythromycin resistance gene ermX. Strains JNFY1, JNFY4, JNFY9, JNFY11, JNFY13, JNFY14, JNFY15, JNFY17, and JNFY28 contained the lincosamide antibiotic resistance gene lsaC, while strains JNFY4, JNFY9, and JNFY13 contained the tetracycline resistance genes tetL and tetM. The comparative genomics data also showed that all strains contain the daunorubicin resistance protein (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Antibiotic-resistance genes predicted in genome of the Gardnerella strains.

| Strains | Macrolides-resistant |

Tetracyclines-resistant |

||

| ermX | lsaC | tetL | tetM | |

| ATCC 14019 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| JNFY1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| JNFY3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| JNFY4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| JNFY9 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| JNFY11 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| JNFY13 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| JNFY14 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| JNFY15 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| JNFY17 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| JNFY28 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Resistance tests showed that Gardnerella strains containing erythromycin resistance genes were resistant to macrolide azithromycin. Similarly, prevalent strains containing tetracycline resistance genes were resistant to tetracycline. Strains JNFY13 and JNFY28 showed weak resistance to erythromycin, despite their lack of ermX. Alternatively, strain JNFY3 showed strong resistance to lincosamide, despite its lack of lsaC. YadH (ABC-type multidrug transport system) and McrA (5-methylcytosine-specific restriction endonuclease) existed only in metronidazole-resistant strains JNFY3, JNFY4, JNFY14, JNFY17, and JNFY28 (Table 4), thus these genes are likely involved in metronidazole resistance.

TABLE 4.

MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) of the Gardnerella strains on common antibiotics in clinic.

| Antibiotics-resistant genes |

MIC(μg/mL) |

|||||||||||

| First-line |

Second-line |

Third-line |

||||||||||

| Beta-lactam | Tetracycline | Macrolide |

Quinolone | Nitroimidazole | Aminoglycoside | Macrolide | Aminoglycoside | Beta-lactam | Glycopeptide | |||

| AMP | TE | AZM | ERM | CLI | CIP | MTZ | GM | DNR | TO | CMR | VA | |

| ATCC 14019 | <0.25 | <0.25 | <0.25 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 16 | 2 | 64 | 0.25 | 1 |

| JNFY1 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 4 | 0.5 | 0 | 16 | 128 | 8 | 0 | 16 | 0.25 | 1 |

| JNFY3 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 16 | 0.125 | 0.0625 | 16 | >128 | 16 | 8 | 32 | 0.5 | 1 |

| JNFY4 | 0.5 | 16 | 16 | 32 | 128 | 16 | >128 | 16 | 2 | 32 | 0.5 | 1 |

| JNFY9 | 0.25 | 16 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 4 | 4 | 0.125 | 16 | 0.5 | 1 |

| JNFY11 | 1 | 0.25 | 64 | 0.125 | 16 | 16 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 32 | 1 | 1 |

| JNFY13 | 0.25 | 32 | 0.25 | 0.125 | 0 | 1 | >128 | 16 | 2 | 128 | 1 | 1 |

| JNFY14 | 4 | 0⋅125 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0625 | 32 | >128 | 32 | 0⋅5 | 32 | 1 | 1 |

| JNFY15 | 0.5 | <0.25 | 8 | 128 | 128 | 16 | 16 | 32 | 1 | 128 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| JNFY17 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 32 | >128 | 32 | 0 | 64 | 2 | 1 |

| JNFY28 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0 | 8 | >128 | 16 | 32 | 128 | 0.5 | 1 |

AMP, ampicillin; TE, tetracycline; AZM, azithromycin; ERM, erythromycin; CLI, clindamycin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; MTZ, metronidazole; GM, gentamicin; DNR, daunorubicin; TO, tobramycin; CMR, chloramphenicol; VA, vancomycin.

Virulence

Typically, epithelial cell adhesion is mediated by pili. All ten strains of Gardnerella contained ppK, a gene encoding for type IV pili. Some Gardnerella strains share virulence factors involved in pathogenic mechanisms like epithelial cell adhesion, iron absorption, secretion, acting as toxins and endotoxins, and immune escape; virulence factors can also have regulatory functions (Supplementary Table 3). Strains lacking these virulence factors such as JNFY3, JNFY15, and JNFY17 have the common feature of impaired biofilm formation. Gardnerella produces vaginolysin, which plays a critical role in BV pathogenesis. The gene encoding vaginolysin was detected in nine strains, with the exception of JNFY15 (Supplementary Table 4). Strains JNFY3 and JNFY4 exhibited nine and one unique virulence factor(s), respectively, with virulence factors having roles in allantoin utilization, adhesion, secretion and iron uptake (Supplementary Table 5). The TA components and other competitive exclusion genes of the Gardnerella strains are listed in Table 5. There are mainly four TA systems in Gardnerella genomes including HicAB family, PHD-RelE family, ParE family, and RelB-Txe family, with various distribution in the 11 strains. However, the other genes related to competitive exclusion showed a similar pattern in each strain.

TABLE 5.

TA system components and other competitive exclusion genes.

| TA system | ATCC 14019 | JNFY1 | JNFY3 | JNFY4 | JNFY9 | JNFY11 | JNFY13 | JNFY14 | JNFY15 | JNFY17 | JNFY28 |

| HicA-family TA system toxin HicB-family TA system antitoxin |

1 | 2 | HicB only | n/a | 1 | 2 | n/a | 2 | 1 | 1 | n/a |

| PHD/YefM family TA system antitoxin RelE/StbE family TA system toxin |

1 | n/a | PHD only | PHD only | n/a | PHD only | n/a | PHD only | 1 | PHD only | n/a |

| ParE-family TA system toxin TA system antitoxin |

3 | 1 | 1 | n/a | 1 | n/a | 1 | ParE only | 1 | 2 | n/a |

| RelB/DinJ family TA system antitoxin Txe/YoeB family TA system toxin |

5 | 1 | 3 | RelB only | RelB only | 1 | RelB only | 1 | n/a | RelB only | 1 |

| Other genes with potential roles in competitive exclusion | |||||||||||

| Abi-like protein | n/a | 3 | 1 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| CHAP domain protein | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| GH25 enzyme | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| SalY-family antimicrobial peptide ABC transport system, ATP-binding protein | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

n/a indicates protein was not identified within the genome.

Secondary metabolites biosynthesis

Analysis of secondary metabolite gene clusters in ten isolates of Gardnerella demonstrated the presence of polyketosynthase (PKS)-related secondary metabolite gene clusters in the Gardnerella genome. PKS genes encode an enzyme, or enzyme complex with multiple domains, capable of synthesizing polyketo compounds, including common antibiotics such as erythromycin, tetracycline and so on. Type I, type II, and type III PKS synthesize T1PKS, T2PKS, and T3PKS, respectively. The T3PKS gene cluster was predicted in all strains except JNFY3.

Discussion

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a common vaginal infection in women of child-bearing age, with Gardnerella spp. being the main pathogen of BV. Alongside BV, Gardnerella spp. has also been associated with vertebral osteomyelitis and discitis (Graham et al., 2009), retinal vasculitis (Neri et al., 2009), acute hip arthritis (Sivadon-Tardy et al., 2009), and bacteremia (Chen et al., 2018). While the vaginal overgrowth of several anaerobic bacteria has been associated with BV, Gardnerella spp. has a stronger adhesion to vaginal epithelium and a stronger tendency to form biofilm compared to other BV-related microorganisms. It can be used as a scaffold to attach other anaerobic bacteria and is associated with the onset and recurrence of BV (Anahtar et al., 2018). The treatment of recurrent BV is difficult, and existing treatment measures include the prolongation of an antibiotic course and consolidation treatment. However, due to biofilm formation and strain differences in Gardnerella, antibiotics cannot eliminate the bacteria, making the current treatment of BV unable to achieve ideal therapeutic effect (Cohen et al., 2020; Laniewski et al., 2020). Therefore, it is of great significance to construct a database detailing prevalent Gardnerella strains in local China, which can provide the basis for the accurate diagnosis and therapy of BV and allow for the development of more effective antibacterial drugs targeting prevalent strains.

In this study, 20 prevalent strains of Gardnerella from local China were collected from clinical specimens to study the differences in their pathogenicity and drug resistance. This would provide a theoretical basis for the accurate diagnosis and treatment of BV. First, based on cpn60 sequence genotyping, the 20 prevalent strains were divided into subtypes A, B, and C. Based on vly sequence genotyping, prevalent strains were divided into subtypes 1, 2, 3, and 4. Ten strains of subtypes C1 (JNFY9, 13 and 28), C2 (JNFY1,4 and 11), B1 (JNFY14 and 17), A1 (JNFY3), and B4 (JNFY15) were selected for comparative genomics. The genome size of the 10 strains ranged from 1.54 to 1.74 Mb, and the GC content was about 41–43%. No plasmid was observed, and 1–2 gene islands were predicted in 4 strains. The phylogenomic tree of the Gardnerella strains showed that strains JNFY3, JNFY15,17, and JNFY1,4,9,11,13,14,28 were located in three different branches. This was almost identical to the cpn60 phylogenetic tree, except for the position of strain JNFY14. Therefore, the cpn60 distribution could represent genomic classification to some extent. The G. vaginalis strains 5-1, 409-05 and JNFY3 were grouped in the same branch in all three trees, further indicating the weak pathogenicity of these strains in healthy hosts.

Virulence factors associated with microbial pathogenesis were found in the genome of prevalent strains, including factors for adhesion, secretion, iron and magnesium absorption, immune escape, and toxins. Common virulence factors were found in the ten prevalent strains, although differences also exist amongst the strains. It is worth noting that JNFY3 had nine specific virulence factors while JNFY4 had one. In addition, JNFY3, JNFY15, and JNFY17 had severely hindered abilities in biofilm formation. These three strains not only lacked certain carbohydrate metabolism genes (Supplementary Table 2), but also lacked virulence factors related to adhesion, iron absorption and toxins, which might be conductive to biofilm formation in the comparative genomic analysis.

Subsequent biochemical experiments were conducted to preliminarily investigate the pathogenic mechanism of Gardnerella. Experiments on the biofilm-forming capabilities of Gardnerella showed variable abilities to form biofilm amongst different prevalent strains with cpn60 subtype C displaying weak to moderate biofilm-forming abilities. Sialidases are enzymes associated with bacterial invasion of the host and are implicated as virulence factors in diseases such as meningitis, glomerulonephritis, and periodontal disease (Corfield, 1992). Previous studies have shown that BV-associated bacteria produce sialidase, and its activity is inversely related to vaginal IgA response against vaginolysin produced by Gardnerella (Cauci et al., 2003). The sialidase assay showed that most strains lacked sialidase activity despite some strains having a higher NS; thus, there is no association between sialidase and pathogenicity.

Resistance tests showed that Gardnerella was sensitive to antibiotics, including tetracycline, nitroimidazoles, macrolide and aminoglycosides. Meanwhile, the macrolide erythromycin resistance genes ermX and lsaC, and the tetracycline resistance genes tetL and tetM were also predicted in the ten strains. It is worth noting that seven out of the ten strains exhibited strong resistance (≥ 128 μg/mL) to metronidazole, which is the first line of treatment for BV in China. In addition to nitroreductase, YadH and McrA may also have roles in metronidazole resistance, with YadH involved in metronidazole excretion and McrA hydrolyzing the methyl-nitryl group from metronidazole (Lorca et al., 2007; Lubelski et al., 2007).

Additionally, we compared pathogenic genes of the prevalent strain in local China and the American type strain ATCC 14019. According to the phylogenetic analysis, strain ATCC 14019 belonged to the subtype C1, and possessed fairly thick biofilm and tobramycin resistance. Compared to strain ATCC 14019, the Chinese prevalent strains contained poor and incomplete TA systems with only antitoxin genes included, suggesting that the antitoxins may be essential to neutralize the toxins secreted by other microbes in the vaginal biome. The strains JNFY4, JNFY9, JNFY11, JNFY13, and JNFY14 without Abi-like proteins lack means of defense to a broad-range of bacteriocins produced by opponents, which probably is complemented by the single antitoxins (Kjos et al., 2010). Although there was no intact secretion system in Gardnerella, it was speculated that Gardnerella secreted toxic proteins to injure other bacteria, such as Lactobacillus, to enhance their survivability and displace the balance of the normal vaginal microflora. Strain ATCC 14019 encodes a methicillin resistance protein not found in the ten Chinese prevalent strains. Carbohydrate transport and metabolism genes of the 11 Gardnerella strains, including the genes associated with biofilm formation, were also analyzed and combined with biofilm thickness data (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 2). AraD, GalM, and GalT may be responsible for constructing biofilm, while FucP, MalA, and XylF are involved in monosaccharide transport. The additional monosaccharide units in the biofilm of strain JNFY14, arabinose and galactose hydrochloride, may play the role of connective elements which help to build a thicker biofilm.

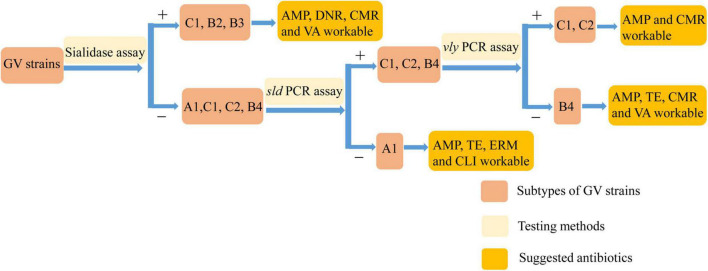

Previous treatment standards involving clindamycin and metronidazole cannot account for all prevalent strains with sufficient efficacy to achieve complete recovery. Therefore, we need targeted treatments for diseases caused by different prevalent strains of Gardnerella to obtain the best results. Although the pathogenic genes of Gardnerella were previously characterized, the pathogenesis of BV is not yet understood. Through genomic and biochemical data analysis, we found that strains of subtype C could generally form biofilm, with varying degrees of antibiotic resistance (apart from invariable tobramycin resistance). Strain G. swidsinskii JNFY3 had a NS of 1, impaired ability to form biofilm, and lacked the sld and lsaC genes. G. vaginalis JNFY14 had the thickest biofilm, whereas strains JNFY17 and G. piotii JNFY15 rarely produced biofilm. On the whole, with the exception of strain JNFY14, the evolutionary trend appears to be the development of a progressively thicker biofilm from JNFY3 to ATCC 14019. All three strains (JNFY14, JNFY17, and JNFY15) showed some resistance to ciprofloxacin, gentamicin and tobramycin. Additionally, G. piotii JNFY15 lacked the vly gene and grew slower than other Gardnerella strains (Table 1). Based on this study, we constructed an initial database of Gardnerella prevalent strains in local China, which can be used as a reference to elucidate more accurate diagnostic pathways and treatments for BV (Table 1 and Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

The diagnose pathway of Gardnerella strains.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Jinan Maternity and Child Care Hospital. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

LG, KZ, and RL conceptualized and designed the study. KZ and XZ analyzed the data. ML, KZ, KW, and HD accessed and verified the data. XJ collected samples from participants. KZ, FZ, and TL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to drafting of the manuscript and read and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission, had full access to all data in the study, and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Xiaodi Chen from the Jinan Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital for providing references about therapy of bacterial vaginosis cited in this article and Carina Muyao Gu at CBe-Learn School for proofreading.

Footnotes

Funding

This study was funded by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2018M642648), the State Key Laboratory of Microbial Technology Open Projects Fund (No. M2021-17), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (No. ZR2021MC038), and the Science and Technology Project of Jinan Municipal Health Commission (No. 2019-1-25).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2022.1009798/full#supplementary-material

References

- Amsel R., Totten P. A., Spiegel C. A., Chen K. C. S., Eschenbach D., Holmes K. K. (1983). Nonspecific vaginitis - diagnostic-criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am. J. Med. 74 14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anahtar M. N., Gootenberg D. B., Mitchell C. M., Kwon D. S. (2018). Cervicovaginal microbiota and reproductive health: The virtue of simplicity. Cell Host Microbe 23 159–168. 10.1016/j.chom.2018.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger-Bachi B., Barberis-Maino L., Strassle A., Kayser F. H. (1989). FemA, a host-mediated factor essential for methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: Molecular cloning and characterization. Mol. Gen. Genet. 219 263–269. 10.1007/BF00261186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland C., Ramsey T. L., Sabree F., Lowe M., Brown K., Kyrpides N. C., et al. (2007). CRISPR recognition tool (CRT): A tool for automatic detection of clustered regularly interspaced palindromic repeats. BMC Bioinformatics 8:209. 10.1186/1471-2105-8-209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauci S., Culhane J. F., Di Santolo M., McCollum K. (2008). Among pregnant women with bacterial vaginosis, the hydrolytic enzymes sialidase and prolidase are positively associated with interleukin-1 beta. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 198 132.e1–132.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauci S., Thorsen P., Schendel D. E., Bremmelgaard A., Quadrifoglio F., Guaschino S. (2003). Determination of immunoglobulin A against Gardnerella vaginalis hemolysin, sialidase, and prolidase activities in vaginal fluid: Implications for adverse pregnancy outcomes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41 435–438. 10.1128/JCM.41.1.435-438.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Han X., Guo P., Huang H., Wu Z., Liao K. (2018). Bacteramia caused by Gardnerella vaginalis in a cesarean section patient. Clin. Lab. 64 379–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2020a). Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard-eleventh edition, Document M07-A11. Wayne, PA: CLSI. [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (2020b). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: Twenty-eighth informational supplement M100-S30. Wayne, PA: CLSI. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen C. R., Wierzbicki M. R., French A. L., Morris S., Newmann S., Reno H., et al. (2020). Randomized trial of lactin-V to prevent recurrence of bacterial vaginosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 382 1906–1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corfield T. (1992). Bacterial sialidases - roles in pathogenicity and nutrition. Glycobiology 2 509–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fettweis J. M., Serrano M. G., Brooks J. P., Edwards D. J., Girerd P. H., Parikh H. I., et al. (2019). The vaginal microbiome and preterm birth. Nat. Med. 25 1012–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis V. I., Stevenson E. C., Porter S. L. (2017). Two-component systems required for virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 364:fnx104. 10.1093/femsle/fnx104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks D. N., Fiedler T. L., Marrazzo J. M. (2005). Molecular identification of bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 353 1899–1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelber S. E., Aguilar J. L., Lewis K. L., Ratner A. J. (2008). Functional and phylogenetic characterization of Vaginolysin, the human-specific cytolysin from Gardnerella vaginalis. J. Bacteriol. 190 3896–3903. 10.1128/JB.01965-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S., Howes C., Dunsmuir R., Sandoe J. (2009). Vertebral osteomyelitis and discitis due to Gardnerella vaginalis. J. Med. Microbiol. 58 1382–1384. 10.1099/jmm.0.007781-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood J. R., Pickett M. J. (1980). Transfer of Hemophilus vaginalis gardner and dukes to a new genus, Gardnerella, G. vaginalis (gardner and dukes) comb nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 30 170–178. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S. K., Padmanabhan B. R., Diene S. M., Lopez-Rojas R., Kempf M., Landraud L., et al. (2014). ARG-ANNOT, a new bioinformatic tool to discover antibiotic resistance genes in bacterial genomes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 212–220. 10.1128/AAC.01310-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwich M. D., Alves J. M., Buck G. A., Strauss J. F., Patterson J. L., Oki A. T., et al. (2010). Drawing the line between commensal and pathogenic Gardnerella vaginalis through genome analysis and virulence studies. BMC Genomics 11:375. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Q., Wang F., Liu S. H., Zhu D. Y., Cong H. J., Gao F., et al. (2016). Structural and biochemical insight into the mechanism of Rv2837c from Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a c-di-NMP phosphodiesterase (vol 291, pg 3668, 2016). J. Biol. Chem. 291 14386–14387. 10.1074/jbc.M115.699801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood R. D., Singh P., Hsu F., Guvener T., Carl M. A., Trinidad R. R., et al. (2010). A type VI secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa targets a toxin to bacteria. Cell Host Microbe 7 25–37. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman R. W., Fukushima M., Diamond L., Kumm J., Giudice L. C., Davis R. W. (2005). Microbes on the human vaginal epithelium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 7952–7957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janulaitiene M., Gegzna V., Baranauskiene L., Bulavaite A., Simanavicius M., Pleckaityte M. (2018). Phenotypic characterization of Gardnerella vaginalis subgroups suggests differences in their virulence potential. PLoS One 13:e0200625. 10.1371/journal.pone.0200625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janulaitiene M., Paliulyte V., Grinceviciene S., Zakareviciene J., Vladisauskiene A., Marcinkute A., et al. (2017). Prevalence and distribution of Gardnerella vaginalis subgroups in women with and without bacterial vaginosis. BMC Infect. Dis. 17:394. 10.1186/s12879-017-2501-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarosik G. P., Land C. B., Duhon P., Chandler R., Jr., Mercer T. (1998). Acquisition of iron by Gardnerella vaginalis. Infect. Immun. 66 5041–5047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaprakash T. P., Schellenberg J. J., Hill J. E. (2012). Resolution and characterization of distinct cpn60-based subgroups of Gardnerella vaginalis in the vaginal microbiota. PLoS One 7:e43009. 10.1371/journal.pone.0043009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalvari I., Nawrocki E. P., Ontiveros-Palacios N., Argasinska J., Lamkiewicz K., Marz M., et al. (2020). Rfam 14: Expanded coverage of metagenomic, viral and microRNA families. Nucleic Acids Res. 49 D192–D200. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. K., Thomas S. M., Ho M. F., Sharma S., Reich C. I., Frank J. A., et al. (2009). Heterogeneity of vaginal microbial communities within individuals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47 1181–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjos M., Snipen L., Salehian Z., Nes I. F., Diep D. B. (2010). The abi proteins and their involvement in bacteriocin self-immunity. J. Bacteriol. 192 2068–2076. 10.1128/JB.01553-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laniewski P., Ilhan Z. E., Herbst-Kralovetz M. M. (2020). The microbiome and gynaecological cancer development, prevention and therapy. Nat. Rev. Urol. 17 232–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl G., Stalhammar-Carlemalm M., Areschoug T. (2005). Surface proteins of Streptococcus agalactiae and related proteins in other bacterial pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 18 102–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorca G. L., Barabote R. D., Zlotopolski V., Tran C., Winnen B., Hvorup R. N., et al. (2007). Transport capabilities of eleven gram-positive bacteria: Comparative genomic analyses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1768 1342–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubelski J., Konings W. N., Driessen A. J. (2007). Distribution and physiology of ABC-type transporters contributing to multidrug resistance in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71 463–476. 10.1128/MMBR.00001-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor J. A., French J. I. (2000). Bacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 55(5 Suppl. 1), S1–S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menard J. P., Mazouni C., Salem-Cherif I., Fenollar F., Raoult D., Boubli L., et al. (2010). High vaginal concentrations of Atopobium vaginae and Gardnerella vaginalis in women undergoing preterm labor. Obstet. Gynecol. 115 134–140. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c391d7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neri P., Salvolini S., Giovannini A., Mariotti C. (2009). Retinal vasculitis associated with asymptomatic Gardnerella vaginalis infection: A new clinical entity. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 17 36–40. 10.1080/09273940802491876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nugent R. P., Krohn M. A., Hillier S. L. (1991). Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29 297–301. 10.1128/jcm.29.2.297-301.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson J. L., Stull-Lane A., Girerd P. H., Jefferson K. K. (2010). Analysis of adherence, biofilm formation and cytotoxicity suggests a greater virulence potential of Gardnerella vaginalis relative to other bacterial-vaginosis-associated anaerobes. Microbiology 156 392–399. 10.1099/mic.0.034280-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peebles K., Velloza J., Balkus J. E., McClelland R. S., Barnabas R. V. (2019). High global burden and costs of bacterial vaginosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex. Transm. Dis. 46 304–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleckaityte M., Janulaitiene M., Lasickiene R., Zvirbliene A. (2012). Genetic and biochemical diversity of Gardnerella vaginalis strains isolated from women with bacterial vaginosis. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 65 69–77. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00940.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punsalang A. P., Jr., Sawyer W. D. (1973). Role of pili in the virulence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Infect. Immun. 8 255–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainey F. A., Ward-Rainey N., Kroppenstedt R. M., Stackebrandt E. (1996). The genus Nocardiopsis represents a phylogenetically coherent taxon and a distinct actinomycete lineage: Proposal of Nocardiopsaceae fam. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 46 1088–1092. 10.1099/00207713-46-4-1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosca A. S., Castro J., Sousa L. G. V., Cerca N. (2020). Gardnerella and vaginal health: The truth is out there. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 44 73–105. 10.1093/femsre/fuz027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottini G., Dobrina A., Forgiarini O., Nardon E., Amirante G. A., Patriarca P. (1990). Identification and partial characterization of a cytolytic toxin produced by Gardnerella vaginalis. Infect. Immun. 58 3751–3758. 10.1128/iai.58.11.3751-3758.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivadon-Tardy V., Roux A. L., Piriou P., Herrmann J. L., Gaillard J. L., Rottman M. (2009). Gardnerella vaginalis acute hip arthritis in a renal transplant recipient. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47 264–265. 10.1128/JCM.01854-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swidsinski A., Mendling W., Loening-Baucke V., Ladhoff A., Swidsinski S., Hale L. P., et al. (2005). Adherent biofilms in bacterial vaginosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 106(5 Pt 1), 1013–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaneechoutte M., Guschin A., Van Simaey L., Gansemans Y., Van Nieuwerburgh F., Cools P. (2019). Emended description of Gardnerella vaginalis and description of Gardnerella leopoldii sp. nov., Gardnerella piotii sp. nov. and Gardnerella swidsinskii sp. nov., with delineation of 13 genomic species within the genus Gardnerella. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 69 679–687. 10.1099/ijsem.0.003200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker B. J., Abeel T., Shea T., Priest M., Abouelliel A., Sakthikumar S., et al. (2014). Pilon: An integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One 9:e112963. 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workowski K. A., Berman S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 59 1–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeoman C. J., Yildirim S., Thomas S. M., Durkin A. S., Torralba M., Sutton G., et al. (2010). Comparative genomics of Gardnerella vaginalis strains reveals substantial differences in metabolic and virulence potential. PLoS One 5:e12411. 10.1371/journal.pone.0012411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Rochefort D. (2013). Fast and effective paper based sensor for self-diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis. Anal. Chim. Acta 800 87–94. 10.1016/j.aca.2013.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.