Abstract

Glycosylation was catalyzed by UDP-glycosyltransferase (UGT) and was important for enriching diversity of flavonoids. Chinese bayberry (Morella rubra) has significant nutritional and medical values because of diverse natural flavonoid glycosides. However, information of UGT gene family was quite limited in M. rubra. In the present study, a total of 152 MrUGT genes clustered into 13 groups were identified in M. rubra genome. Among them, 139 MrUGT genes were marked on eight chromosomes and 13 members located on unmapped scaffolds. Gene duplication analysis indicated that expansion of MrUGT gene family was mainly forced by tandem and proximal duplication events. Gene expression patterns in different tissues and under UV-B treatment were analyzed by transcriptome. Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside (C3Glc) and quercetin 3-O-glucoside (Q3Glc) were two main flavonoid glucosides accumulated in M. rubra. UV-B treatment significantly induced C3Glc and Q3Glc accumulation in fruit. Based on comprehensively analysis of transcriptomic data and phylogenetic homology together with flavonoid accumulation patterns, MrUFGT (MrUGT78A26) and MrUGT72B67 were identified as UDP-glucosyltransferases. MrUFGT was mainly involved in C3Glc and Q3Glc accumulation in fruit, while MrUGT72B67 was mainly involved in Q3Glc accumulation in leaves and flowers. Gln375 and Gln391 were identified as important amino acids for glucosyl transfer activity of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67 by site-directed mutagenesis, respectively. Transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana tested the function of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67 as glucosyltransferases. The present study provided valuable source for identification of functional UGTs involved in secondary metabolites biosynthesis in M. rubra.

Keywords: Morella rubra, UGT, anthocyanin, flavonol, UDP-glucosyltransferase

Introduction

Diverse plant secondary metabolites such as flavonoids play important roles in plant development and human health (Yin et al., 2014; Bondonno et al., 2019; Alseekh et al., 2020). Glycosylation usually occurs during later stages in many secondary metabolite biosynthesis pathways. Glycosylation could improve solubility, stability, transferability, and diversity of many plant secondary metabolites like flavonoids (Bowles et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2018; Naeem et al., 2021).

UDP-glycosyltransferase (UGT) family was the largest family in plants among GT super families reported in CAZy1 database. It catalyzed glycosylation formation of many small molecules, including flavonoids, hormones, and xenobiotics (Vogt and Jones, 2000; Bowles et al., 2006). With the rapid development in bioinformatics and plant genomics, UGT gene families have been identified in many plants, from algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii to vascular plants like Selaginella moellendorffii and Prunus persica (Caputi et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2017). In model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, 107 UGT members were identified in genome, and were clustered into 14 groups (A-N) based on phylogenetic relationship analysis (Ross et al., 2001). Subsequently, four new phylogenetic groups, named O, P, Q, and R, that were not presented in Arabidopsis were discovered in Malus × domestica (Caputi et al., 2012), Zea mays (Li et al., 2014), and Camellia sinensis (Cui et al., 2016). Gene family identification facilitates discovery of functional UGT genes. CsUGT78A14 and CsUGT78A15 were found to be involved in astringent taste compounds biosynthesis by analysis of C. sinensis UGT gene family (Cui et al., 2016). And several UGTs involved in biosynthesis of anti-diabetic plant metabolite Montbretin A were discovered based on UGT gene family analysis (Irmisch et al., 2018; Irmisch et al., 2020).

UDP-glycosyltransferase family contains a conserved motif close to C-terminal, named the plant secondary product glycosyltransferase (PSPG) box. Amino acids in PSPG-box were important for glycosyl transfer activity of UGTs (Shao et al., 2005; Offen et al., 2006; Osmani et al., 2009). For example, last amino acid residue of PSPG-box for UDP-glucosyltransferases usually was glutamine (Gln), and examples include VvGT1 (Ford et al., 1998), MdUGT71B1 (Xie et al., 2020), and PpUGT78T3 (Xie et al., 2022). However, other amino acids could also influence UGT sugar donor preference and more UGTs with different functions should be identified to elucidate the mechanism of sugar donor preference of UGTs.

Chinese bayberry (Morella rubra), a member of the Myricaceae, has significant nutritional and medical values due to high content of diverse natural flavonoids such as flavonol glycosides and anthocyanins (Sun et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2022). It was reported that flavonoid-rich extracts of fruit and leaves had diverse bioactivities such as antioxidant (Sun et al., 2013; Yan et al., 2016), anti-diabetes (Sun et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2020), and anti-cancer (Sun et al., 2012). However, information of UGT gene family and identification of UGTs related to flavonoid glycosylation in M. rubra were limited. Recently, both transcriptome and genome information with high-quality have been published in M. rubra (Feng et al., 2013; Jia et al., 2019), which makes identification of UGT gene family in this plant available.

In the present study, a comprehensive genome-wide identification of UGT gene family was carried out in M. rubra. A total of 152 MrUGT putative proteins were identified from M. rubra genome. Genome-wide analysis was performed including phylogenetic relationship, gene structure, chromosome distribution, and gene duplication. Furthermore, expression patterns of MrUGT genes were analyzed by Ribonucleic Acid (RNA)-seq in different tissues and ultraviolet (UV) B-treated fruit. Base on MrUGT gene family analysis, MrUFGT (MrUGT78A26) and MrUGT72B67 were identified as flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferases by in vitro and in vivo investigations. In addition, important amino acids were identified for glucosyl transfer activity of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67 by site-direct mutagenesis.

Materials and methods

Identification and phylogenetic analysis of MrUGT gene family

A Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profile for UGT (PF00201) downloaded from Pfam2 database was used as a query file to identify UGT proteins in M. rubra genome using simple HMM search program in TBtools (Jia et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2020). Multiple EM for Motif Elicitationv (MEME, suite 5.0.3) website and CDD3 were used to check completeness of MrUGT sequences. Incomplete coding sequences were manually corrected based on RNA-Seq database (PRJNA714192). MrUGT protein sequences and other plant UGTs were aligned with MUSCLE program. Phylogenetic tree was constructed using neighbor-joining method in MEGA-X with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Genbank accession numbers could be found in Supplementary Table 1. Multiple sequence alignment was carried out using MUSCLE program between MrUGTs and other glucosyltransferases. Sequence alignment was visualized using GeneDoc software.

Analysis of conserved motif and gene structure

Conserved motifs in MrUGT proteins were analyzed by simple MEME Wrapper program in TBtools with default parameters. Results of conserved motifs were visualized by TBtools (Chen et al., 2020). Sequences of conserved motifs were visualized by WebLogo4 website (Crooks et al., 2004). Intron-exon map of MrUGT was constructed according to genome annotation file. Gene Structure Display Server 2.05 was used to investigate intron-exon structure in MrUGT gene family using sequence format (Hu et al., 2014).

Chromosome distribution and syntenic analysis of MrUGT gene family

Gene Location Visualize program of TBtools was used to investigate and visualize chromosome distribution of MrUGT genes according to genome annotation file (Chen et al., 2020). To investigate the evolutionary relationship between MrUGTs and UGTs of other species, synteny analysis was performed within three Rosids species, i.e., Arabidopsis, walnut (Juglans regia), and peach (P. persica). Synteny relationship was analyzed by One Step MCScanX program and visualized by DualSyntePlot program with the help of TBtools (Chen et al., 2020). DupGen_finder program was used to analyze gene duplication events in M. rubra genome (Qiao et al., 2019).

Chemicals reagents

Quercetin (Q), kaempferol (K), quercetin 3-O-glucoside (Q3Glc), flavanones (naringenin and hesperetin), flavanols (epicatechin and catechin), flavones (apigenin and luteolin), and isoflavones (genistein and daidzein) were purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). Cyanidin (C) and pelargonidin (P) were purchased from Extrasynthese (Lyon, France). Gradient grade for liquid chromatography of methanol and acetonitrile as well as cyanidin 3-O-glucoside (C3Glc) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). UDP-glucose (UDP-Glc), UDP-rhamnose (UDP-Rha), and UDP-galactose (UDP-Gal) were obtained from Yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd., (Shanghai, China).

Plant materials and ultraviolet-B treatment

Flowers, leaves, and fruit of different development stages of M. rubra cv. Biqi were obtained from an orchard in Lanxi (Zhejiang, China). Four fruit development stages were: S1 for 45 days after flowering (DAF); S2 for 75 DAF; S3 for 80 DAF; S4 for 85 DAF. All materials were uniform in size and free from mechanical damage. Samples were cut into small pieces, frozen with liquid nitrogen immediately, and stored at −80°C for further analysis. All samples were collected for three biological replicates.

UV-B treatment was carried out as reported (Xie et al., 2020) with some modifications. Treatments were carried out at different layers in the same climatic chambers under controlled conditions with a relative humidity of 90–96% and constant temperature at 20°C. Fruit of ‘Biqi’ cultivar at 70 DAF were selected to treated with UV-B irradiation. Fruit were divided into two groups, and one group was exposed to UV-B irradiation (280–315 nm, 50 μW cm–2) for 2 and 6 days. Fruit of control group were put in the dark. Incubator was covered with black cloth to avoid light pollution. Three biological replicates were used and each replicate contained five to eight fruits.

RNA-seq and gene expression

Total RNA was isolated using cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method as reported (Feng et al., 2013). Integrity of total RNA was detected using nanodrop and gel electrophoresis. RNA-Seq of UV-B-treated fruit was carried out by Novogene Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). RNA-Seq platform was Illumina Novaseq. Library was prepared using NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina. Gene expression levels were assessed by FPKM values. Different expression analysis was carried out using DESeq2 (1.20.0). Heatmap of transcript profiles was presented by TBtools (Chen et al., 2020). Gene expression was performed by reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) as reported (Cao et al., 2019) using primers showed in Supplementary Table 2. Actin gene (MrACT, GQ340770) was used as internal reference gene. Relative gene expression was calculated using 2–ΔΔCt method.

HPLC analysis of flavonoid glycosides

Flavonoid glycosides were extracted and analyzed as reported (Downey et al., 2007; Cao et al., 2019) with some modifications. Sample powder with 0.1 g was sonicated in 1 ml 50% methanol/water (v/v) for 30 min at room temperature. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 min, precipitates were extracted one more time. Both supernatants were combined and then analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) after centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 min as previous reported (Cao et al., 2019). Standard curves were used to quantitate Q3Glc at 350 nm and C3Glc at 520 nm.

Protein recombination and purification

Coding sequences of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67 were subcloned into expression vector pET-32a (+) using specific primers listed in Supplementary Table 3. Recombination plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Protein recombination was carried out as reported with some modifications (Xie et al., 2020). Recombinant proteins were induced by adding 500 μM IPTG and cultured at 16°C for 20–24 h. HisTALON Gravity Columns (Takara Bio Inc., Beijing, China) was used to purify His-tagged proteins according to manual. PD-10 columns (GE Healthcare, UK) was used to desalt of His-tagged proteins. Recombinant proteins were monitored by SDS-PAGE and quantitated by BCA kit (FUDE, Hangzhou, China).

Enzyme assay

Enzymatic activity assay was carried out as reported with some modifications (Ren et al., 2022). Reactions were performed in a total volume of 100 μl mixture containing 0.1 M Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.5), 1 mM sugar donors (UDP-Glc/UDP-Gal/UDP-Rha), 60 μM sugar acceptors (Q/C), and 1–2 μg recombinant proteins at 30°C for 20 min. Enzyme reactions were stopped by adding 100 μl methanol, and analyzed by HPLC after centrifugation (12,000 rpm for 15 min) as reported (Xie et al., 2020). Enzyme products were detected at 350 nm for flavonol glycosides and at 520 nm for anthocyanins. Enzyme products were analyzed by LC-MS/MS as reported (Ren et al., 2022).

Site-directed mutagenesis analysis

Mutant proteins were generated by overlapping PCR using primers listed in Supplementary Table 4. Mutant sequences were confirmed by sequencing. Recombinant mutant proteins were monitored by SDS-PAGE. Reaction for site-directed mutagenesis analysis was carried out as mentioned above, and 1–2 μg recombinant mutated proteins were contained in reaction mixture. Relative activity of mutant enzyme was quantified using HPLC.

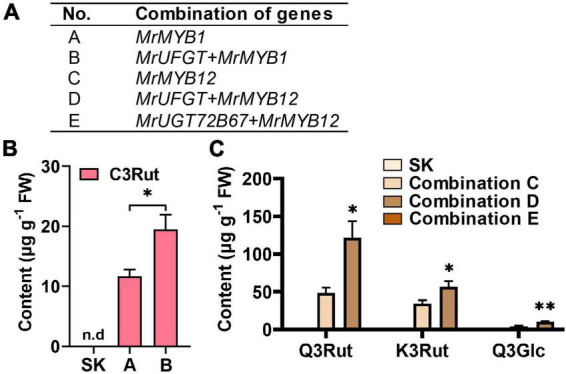

Transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana

Transient expression in N. benthamiana was performed as reported (Cao et al., 2019). Coding sequences of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67 were subcloned into pGreenII0029 62-SK (SK) vector. Specific primers were listed in Supplementary Table 5. All recombinant plasmids were electroporated into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. Bacteria were resuspended in infiltration bufefr (150 μM acetosyringone, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES, pH 5.6) to OD600 of 0.75. Mixtures were prepared according to combination information in Figure 8A. Each combination contained A. tumefaciens strain p19. Four-week-old N. benthamiana leaves were infiltrated with different combination mixtures. Flavonoid glycosides were analyzed by LC-MS/MS after 5 days infiltration as previous reported (Ren et al., 2022). Data were collected from at least three independent N. benthamiana plants.

FIGURE 8.

Transient expression of MrUGTs in Nicotiana benthamiana. (A) Transient expression information of combination mixtures. (B) Analysis of anthocyanins in N. benthamiana leaves infiltrated with combinations contained MrUFGT. (C) Analysis of flavonol glucosides in N. benthamiana leaves infiltrated with combinations contained MrUFGT or MrUGT72B67. Leaves infiltrated with empty SK vector were used as control. Products were confirmed by LC-MS/MS. Data are mean ± SE (n = 3).

Statistical analysis

One-way ANOVA followed Tukey test was performed to analyze significant differences among different groups at a significance level of 0.05 using DPS 9.01. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to analyze two-sample statistical significance. Experimental data were analyzed and presented by Origin 9.0 (Northampton, MA, USA) and GraphPad Prism 9 (San Diego, CA, USA). All experimental data were collected from at least three biological replicates. Error bar was presented as standard error (SE).

Results

Identification and phylogenetic analysis of MrUGT gene family

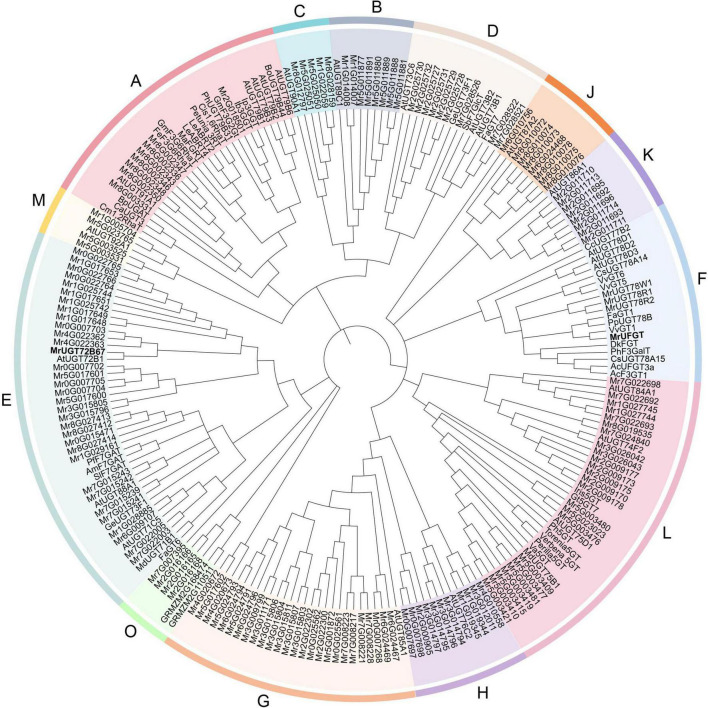

To identify UGT gene family in M. rubra genome, an HMM profile (PF00201) was used as a query file to find MrUGT proteins. The screening criteria was that the E-value < 1. After manual correction of incomplete sequences based on RNA-Seq database, sequences containing more than 350 amino acids were chosen for further analysis. A total of 152 predicted amino acid sequences with conserved PSPG-box were obtained. A phylogenetic tree was constructed with other plant UGTs to investigate functional UGT in M. rubra. Results showed that MrUGTs were phylogenetically divided into 13 major groups, i.e., A–H, J–M, and O (Figure 1). Among them, 12 groups (A–H, J–M) were identified in Arabidopsis (Ross et al., 2001) and one group (group O) was newly identified (Caputi et al., 2012). Group I and N were absent in M. rubra genome (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of Morella rubra UDP-glycosyltransferase (UGT) gene family. Phylogenetic tree was constructed by neighbor-joining method. Groups are shown in different colors. Abbreviations of species names are follows: AC, Aralia cordata; Am, Antirrhinum majus; At, Arabidopsis thaliana; Bo, Brassica oleracea; Bp, Bellis perennis; Ca, Catharanthus roseus; Cc, Crocosmia × crocosmiiflora; Cm, Citrus maxima; Cis, Citrus sinensis; Cs, Camellia sinensis; Dk, Diospyros kaki; Fa, Fragaria × ananassa; Fe, Fagopyrum esculentum; Ge, Glycyrrhiza echinata; Gm, Glycine max; Gt, Gentiana triflora; Iris, Iris hollandica; Ib, Ipomoea batatas; Ip, Ipomoea nil; Le, Lobelia erinus; Ma, Morus alba; Md, Malus × domestica; Perilla, Perilla frutescens; Ph, Petunia hybrida; Pf, Perilla frutescens; Pp, Prunus persica; Sb, Scutellaria baicalensis; Sl, Scutellaria laeteviolacea; Torenia, Torenia hybrid; Va, Vitis amurensis; Verbena, Verbena hybrida; Vv, Vitis vinifera. Accession numbers of UGTs from other species are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

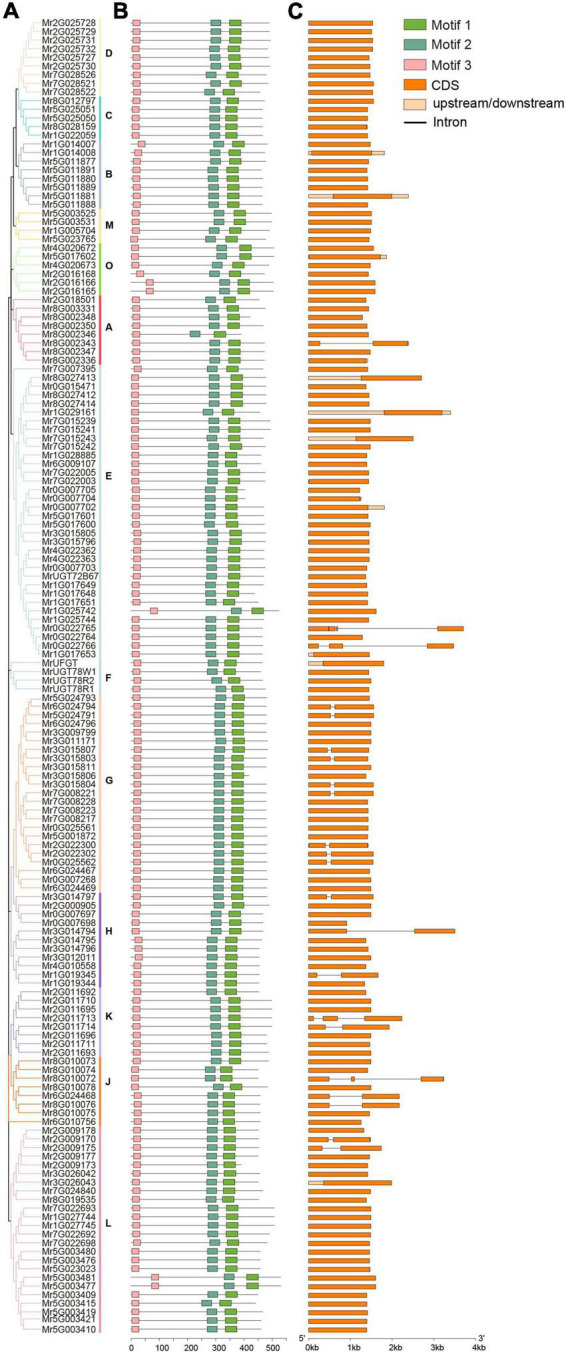

Analysis of conserved motif and gene structure of MrUGT gene family

To investigate characteristics of MrUGT gene family, conserved motifs and intron-exon structure were analyzed. Number of MrUGT proteins was different in each group. Group E contained the largest members in MrUGT gene family, i.e., 34 MrUGT members (22%) (Figure 2). Followed by group L and group G, the MrUGT number was 24 (16%) and 23 (15%), respectively (Figure 2). Groups F and M contained the least MrUGT members, both were four UGT members (Figure 2). Three conserved motifs were predicted in MrUGT family based on MEME analysis. Motif 1 was conserved PSPG-box, and motif 2 and 3 were conserved in all MrUGT proteins (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 1). This indicating that UGT also has other conserved motif in addition to PSPG-box.

FIGURE 2.

Analysis of phylogenetic relationship (A), conserved motif (B), and gene structure (C) of MrUGT gene family. The 14 groups are shown with different colors. Three conserved motifs were shown with different colors. Orange box represented exons and black lines represented introns.

Intron-exon structure was investigated to understand gene function and evolutionary relationships within MrUGT gene family. Results showed that 22 MrUGT members contained introns, accounting for about 15% (Figure 2). In terms of intron numbers, 18 MrUGTs contained one intron, three MrUGTs had two introns, and one MrUGT had three introns (Figure 2). For UGT groups, the largest number of UGTs with introns was observed in group G, and that was nine members. Followed by group H and J, both groups had three UGTs with introns (Figure 2). Most of MrUGTs does not had introns, and gene structure was relatively conservative.

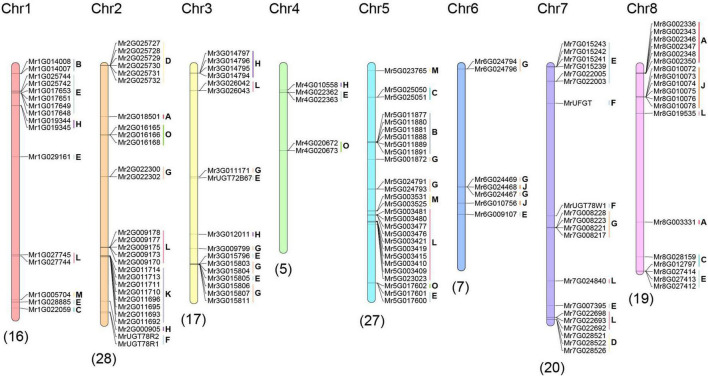

Chromosome distribution and synteny analysis of MrUGT gene family

To investigate the distribution of MrUGT genes, genomic positions of each MrUGT were marked on chromosomes (Figure 3). A total of 139 MrUGT genes were marked on eight chromosomes of M. rubra and 13 MrUGT genes located on unmapped scaffolds (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 6). There were largest MrUGT numbers (28) located on chromosome 2, followed by 27 MrUGTs on chromosome 5 and 20 MrUGTs on chromosome 7. Only five MrUGT genes located on chromosome 4. For the largest MrUGT group (Group E), eight members were distributed on chromosome 1, three members were distributed on chromosome 3, two members were distributed on chromosome 4, two members were distributed on chromosome 5, one member was distributed on chromosome 6, seven members were distributed on chromosome 7, three members were distributed on chromosome 8, and eight members were distributed on unmapped scaffolds (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 6).

FIGURE 3.

Chromosome distribution of MrUGT genes. Numbers of chromosomes were labeled at the top of each chromosome. Numbers of MrUGTs on chromosome were labeled at the bottom of each chromosome. Group of MrUGTs is labeled next to MrUGT accession numbers.

Gene duplication was one of driven forces for gene family expansion (Qiao et al., 2019). Four gene duplication modes were identified in MrUGT gene family based on method reported by Qiao et al. (2019), including whole-genome duplication (WGD), dispersed duplication (DSD), tandem duplication (TD), and proximal duplication (PD). A total of 29 TD events were observed in MrUGT gene family, followed by 28 PD events. Only eight DSD events and three WGD events were observed in MrUGT gene family (Supplementary Table 7). Group L contained the largest number of gene duplication events, and it was 14. Followed by groups E and G, number of gene duplication events was nine and eight, respectively (Supplementary Table 7).

To further explore evolutionary relationships of MrUGT, syntenic maps were constructed between M. rubra and three Rosid species, including Arabidopsis, J. regia, and P. persica (Supplementary Figure 2). A total of 22, 41, and 40 homologous UGT gene pairs were identified between M. rubra and Arabidopsis, J. regia, and P. persica. It indicated that M. rubra has a closer evolutionary relationship with J. regia and P. persica, which was consistent with the study of M. rubra genome (Jia et al., 2019).

Tissue and temporal expression pattern of MrUGT genes in Morella rubra

RNA-seq was performed to analyze expression pattern of MrUGT genes in flowers, leaves, and fruit development stages of ‘BQ’ cultivar. A total of 29 MrUGT genes showed the highest expression level in flowers (Figure 4). All UGT members in group C exhibited highest expression level in flowers (Figure 4). The other MrUGT genes expressed highest in flowers were mainly from group E, G, and H (Figure 4). A total of 30 MrUGT genes showed the highest expression level in leaves. More than half of members in group D and H were mainly expressed in leaves (Figure 4). Notably, a total of 99 MrUGT members were mainly expressed in fruit, accounting for 65% of total MrUGT. Among them, 31 MrUGT members had the highest expression level in S1 stage, 23 MrUGTs showed the highest expression level in S2 stage, 11 MrUGTs showed the highest expression level in S3 stage, and 34 MrUGTs showed the highest expression level in S4 stage (Figure 4). 22 members of the largest group (group E) showed the highest expression level in fruit (Figure 4). All members of group K and group O had the highest expression level in fruit (Figure 4). Expression pattern analysis indicated that MrUGTs played important roles in metabolic pathways related to fruit development and ripening.

FIGURE 4.

Expression pattern of MrUGT genes in different tissues of Morella rubra. Expression of MrUGT genes in flowers (F), leaves (L), and fruit development (S1–S4) are shown. Color scale represents –2 to 2. (A–H), (J–M), and (O) mean different phylogenetic groups of MrUGT genes.

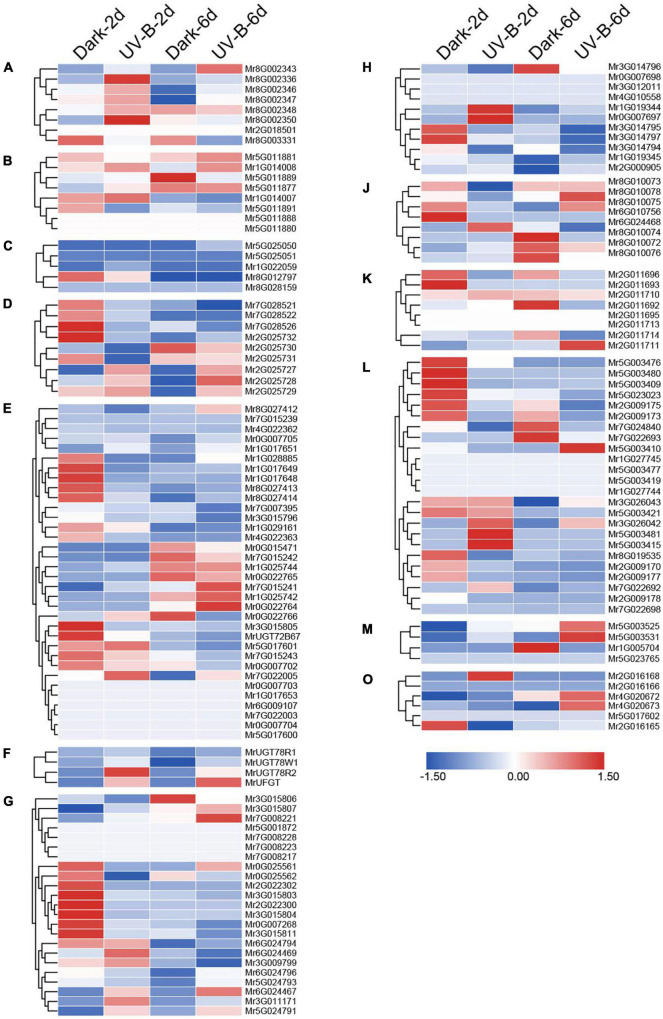

Expression pattern of MrUGT genes in response to ultraviolet-B irradiation

UV-B stress is an efficient treatment for induction of flavonoid glycosides accumulation in plants (Kolb et al., 2001; Stracke et al., 2010; Henry-Kirk et al., 2018; Xie et al., 2022). Therefore, we carried out UV-B treatment for investigation and identification of MrUGTs involved in flavonoid glucosylation (Figure 5). Based on transcriptomic analysis, gene expression of 13 MrUGT genes were significantly induced (log2FC >1, p < 0.05) by UV-B treatment. Among them, seven MrUGT genes were significantly induced after 2 days UV-B treatment, and ten MrUGT genes were significantly induced after 6 days UV-B treatment (Supplementary Table 8). Four MrUGT genes were significantly induced by UV-B treatment after both 2 and 6 days.

FIGURE 5.

Expression pattern of MrUGT genes in response to UV-B irradiation. Color scale represents –1.5 to 1.5. (A–H), (J–M), and (O) mean different phylogenetic groups of MrUGT genes.

Based on current knowledge, UGTs in group F were closely related to flavonoid 3-O-glycoside formation. Among the UV-B induced MrUGTs, only four members belong to group F, i.e., MrUGT78R1, MrUGT78R2, MrUGT78W1, and MrUFGT (Supplementary Table 8). Recently, MrUGT78R1 and MrUGT78R2 were identified as UDP-rhamnosyltransferases while MrUGT78W1 was identified as UDP-galactosyltransferase involved in flavonol glycosylation in M. rubra by our group (Ren et al., 2022). Therefore, MrUFGT was chosen as one of potential candidate UGTs for flavonoid glucosylation.

Identification of MrUGTs related to flavonoid glucoside accumulation

Flavonoid glucoside profiles in different tissues of M. rubra were analyzed by HPLC. Flavonoid glucosides accumulation exhibited tissue specificity in M. rubra. C3Glc was mainly accumulated in mature fruit (S4) and flowers (Figure 6A). While Q3Glc was mainly accumulated in leaves and flowers (Figure 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Flavonoid glucosides accumulation and gene expression of MrUGTs in different tissues and UV-B-treated fruit. (A) Accumulation of cyanidin 3-O-glucoside (C3Glc) and quercetin 3-O-glucoside (Q3Glc) in flowers (F), leaves (L), and fruit development stages (S1–S4) of Morella rubra. (B) Gene expression of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67 in different tissues. Different letters indicate significant difference between different groups (P < 0.05). (C) Effects of UV-B irradiation on content of C3Glc and Q3Glc in M. rubra fruit. (D) Gene expression of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67 in response to UV-B irradiation. Student’s t-test is used for statistical analyses between two samples (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05). All data are presented as the mean ± SE (n = 3).

Correlation analysis between C3Glc content and expression of MrUGTs in different tissues was performed. A total of 12 MrUGT genes showed high correlation coefficient (r > 0.8) with C3Glc content, where only MrUFGT belongs to group F of UGT family (Supplementary Figure 3A). Similarly, correlation analysis between Q3Glc content and expression of MrUGTs in different tissues was performed. A total of 9 MrUGT genes showed high correlation coefficient (r > 0.8) with Q3Glc content (Supplementary Figure 3B). However, none of these 9 MrUGTs belongs to group F of UGT family. MrUGT72B67 in group E showed the highest expression in leaves and flowers, and was thus chosen for recombinant protein expression and enzymatic assay.

Gene expression of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67 was confirmed by RT-qPCR (Figure 6B). Results showed that MrUFGT was mainly expressed in fruit and flowers, and increased during fruit development (Figure 6B), which was consistent with C3Glc accumulation pattern. While MrUGT72B67 was mainly expressed in leaves and flowers (Figure 6B), which was consistent with Q3Glc accumulation pattern in leaves and flowers. UV-B treatment could significantly induce C3Glc and Q3Glc accumulation in ‘Biqi’ fruit (Figure 6C). And gene expression of MrUFGT was significantly induced by UV-B, while MrUGT72B67 were not (Figure 6D).

Enzymatic assays of recombinant MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67

MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67 were isolated from cDNA libraries of ‘Biqi’ cultivar. ORFs of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67 were 1,389 and 1,422 bp, which encoded predicted proteins composed of 462 and 473 amino acids, respectively. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67 exhibited the highest homology with VvGT1 and AtUGT72B1, respectively (Supplementary Figure 4). Sequence alignment analysis showed that PSPG-box of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67 was conserved and closed to C-terminal (Supplementary Figure 5). Recombinant proteins of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67 were verified by SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Figure 6). Enzymatic assays were performed to verify functions of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67. Results showed that MrUFGT could only transfer UDP-Glc to anthocyanidin or flavonol aglycones. Product peaks with m/z 448 and m/z 463 tentatively identified as C3Glc and Q3Glc based on fragmentation information (Figures 7A,B and Supplementary Figure 7). MrUFGT could not transfer UDP-Rha or UDP-Gal to anthocyanidins or flavonol aglycones such as C or Q (Figures 7A,B). MrUGT72B67 could only transfer UDP-Glc to flavonol aglycones, resulting in formation of peak with m/z 463 which was tentatively identified as Q3Glc (Figure 7C and Supplementary Figure 7). MrUGT72B67 could not transfer UDP-Rha or UDP-Gal to flavonol aglycone such as Q (Figure 7C).

FIGURE 7.

Enzymatic assay of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67. Enzyme activity analysis of recombinant MrUFGT with cyanidin (A) and quercetin (B) as sugar acceptors, UDP-glucoside (UDP-Glc), UDP-galactoside (UDP-Gal), and UDP-rhamnoside (UDP-Rha) as sugar donors. (C) Enzyme activity analysis of recombinant MrUGT72B67 with quercetin as sugar acceptor, UDP-Glc, UDP-Gal, and UDP-Rha as sugar donors. Relative activities of recombinant MrUFGT with UDP-Glc (D) and MrUGT72B67 with UDP-Glc (E) toward various flavonoids. Site-directed mutagenesis analysis of MrUFGT (F) and MrUGT72B67 (G) with quercetin as acceptor and UDP-Glc as sugar donor. Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 3). n.d, not detected.

Enzyme activity of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67 for different flavonoid aglycones were also investigated. For MrUFGT, C was the best substrate since MrUFGT showed the highest activity toward it. For different substrates (flavonoid aglycones), relative enzyme activities of MrUFGT were calculated by comparison of enzyme activity toward each substrate with that of C. As a result, MrUFGT showed relative lower activity for flavonol aglycones (M, Q, and K) compared to anthocyanidin aglycones (Figure 7D). MrUFGT did not exhibit glucosyl transfer activity toward naringenin, hesperetin, epicatechin, catechin, luteolin, apigenin, genistein, and daidzein (Figure 7D). For MrUGT72B67, Q was the best substrate since MrUGT72B67 showed the highest activity toward it. For different substrates (flavonoid aglycones), relative enzyme activities of MrUGT72B67 were calculated by comparison of enzyme activity toward each substrate with that of Q. As a result, MrUGT72B67 showed relative lower activity for C, P, naringenin, hesperetin, luteolin, apigenin, and daidzein compared to Q (Figure 7E). It indicated that MrUGT72B67 displayed a relatively broad substrate preference toward flavonoid.

To explore the role of last amino acid residue in PSPG-box for glucosyl transfer activity of MrUGTs, site-directed mutagenesis was carried out. Two mutant proteins (Q375H of MrUFGT and Q391H of MrUGT72B67) were generated by overlapping PCR (Supplementary Figure 8). Q375H mutation and Q391H mutation completely lost the glucosyltransferase activity of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67, respectively (Figures 7F,G). No mutations resulted in additional galactosyltransferase or rhamnosyltransferase activity (Supplementary Figure 9).

Transient expression of MrUGTs in Nicotiana benthamiana

To validate functions of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67 in vivo, transient expression was carried out in N. benthamiana plants. Anthocyanin- and flavonol-specific transcription factors MrMYB1 (Niu et al., 2010) and MrMYB12 (Cao et al., 2021) were introduced to transient expression system to enhance substrates level of UGT according to reported (Irmisch et al., 2019; Figure 8A).

Nicotiana benthamiana leaves accumulated cyanidin 3-O-rutinoside (m/z 593 with MS2 fragmentation at m/z 285, C3Rut) when only expressed with MrMYB1 (combination A) (Figure 8B and Supplementary Figure 10). And level of C3Rut was significantly enhanced when MrUFGT was added (combination B) (Figure 8B and Supplementary Figure 10). And flavonol glucoside derivatives, i.e., Q3Rut (m/z 609 with MS2 fragmentation at m/z 300), K3Rut (m/z 593 with MS2 fragmentation at m/z 258), and Q3Glc (m/z 463 with MS2 fragmentation at m/z 300), were significantly accumulated in N. benthamiana leaves infiltrated with MrUFGT (combination D) compared to infiltrated MrMYB12 only (combination C) (Figure 8C and Supplementary Figure 10). Like MrUFGT, flavonol glucoside derivatives (Q3Rut, K3Rut, and Q3Glc) were significantly accumulated in N. benthamiana leaves with addition of MrUGT72B67 (combination E) compared to expressed MrMYB12 only (combination C) (Figure 8C and Supplementary Figure 10). Control leaves did not accumulate anthocyanins or flavonol glycosides at detectable level (Figure 8 and Supplementary Figure 10). These results tested the functional glucosyltransferase activity of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67.

Discussion

UDP-glycosyltransferase gene family contribute to diversity of secondary metabolites

Morella rubra is rich in flavonoid glycosides, and different tissues have been used historically as folk medicines. Here we reported the genome-wide analysis of UGT gene family and identified two MrUGTs involved in the accumulation of flavonoid glucosides.

The first plant reported UGT gene family was Arabidopsis and 107 UGT genes was identified in genome (Li et al., 2014). In the present study, a total of 152 UGT genes were identified in M. rubra genome. Number of MrUGT gene was little difference compared to other species, examples include 241 UGTs in M. domestica (Caputi et al., 2012), 147 UGTs in Z. mays (Li et al., 2014), and 168 UGTs in P. persica (Wu et al., 2017). It indicated that MrUGT gene family did not exhibit significant expansion compared with other plants, which may be related to the lack of recent genome-wide duplication events in M. rubra (Jia et al., 2019). Based on phylogenetic relationship, UGTs in Arabidopsis were clustered into 14 groups (A-N) (Li et al., 2001). And four new groups, i.e., O, P, Q, and R, were discovered subsequently in M. domestica (Caputi et al., 2012), Z. mays (Li et al., 2014), and C. sinensis (Cui et al., 2016). MrUGT gene family contained 13 groups (Figure 1), including 12 groups discovered in Arabidopsis and one newly discovered group O, and with absent of group I, N, P, Q, and R compared to 18 groups (A-R) reported in plants. This indicated that gene loss events occurred during UGT gene family expansion in M. rubra.

UDP-glycosyltransferases prefer to be clustered by regiospecificity rather than species and sugar donor specificity (Yonekura-Sakakibara and Hanada, 2011; Hsu et al., 2017). Therefore, it is considered that sugar donor specificity differentiation was later than divergence of regiospecificity (Hsu et al., 2017). This makes it possible to predict functional UGTs by phylogenetic analysis. For example, UGT members in group A were considered to be related to biosynthesis of flavonoid disaccharides, and examples include Cis1,6RhaT (Frydman et al., 2004), Cm1,2RhaT (Frydman et al., 2013), and PpUGT79AK6 (Xie et al., 2022). UGT members in group O usually exhibited activity toward plant hormone zeatin. For example, PvZOX1 from Phaseolus vulgaris was identified as a zeatin O-xylosyltransferase involved in O-xylosylzeatin formation (Martin et al., 1999). And cisZOG1 from Z. mays was identified as a glucosyltransferase specific to cis-zeatin (Martin et al., 2001). Phylogenetic homology analysis of UGTs would facilitate the discovery of more functional UGTs in plants with specialized metabolites.

Gene duplication is important for gene family expansion, and results in gene clusters on chromosomes. Gene duplication events include five modes according to Qiao et al. (2019), i.e., WGD, TD, DSD, PD, and transposed duplication (TRD). Four modes except TRD were found in MrUGT family. About 19% and 18% MrUGT genes occurred TD and PD events, respectively, indicating that both TD and PD were ongoing processes throughout evolutionary of MrUGT gene family. In Broussonetia papyrifera, TD was primary driving force for expansion of BpUGT gene family (Wang et al., 2021). In higher plants, it was found that groups A, D, E, G, and L expanded more than other groups during plant evolution (Caputi et al., 2012). In M. rubra, groups E, G, and L were expanded significantly compared with other groups, which was mainly related to gene duplication events in these groups.

MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67 involved in flavonoid glucosylation

Various anthocyanins and flavonol glycosides are of interest to researchers because of their importance in plant physiology and human health. To date, many plant UGTs involved in biosynthesis of anthocyanins and flavonol glycosides are reported. Flavonoid 3-O-glycosyltransferase (UFGT) bronze1 from maize was the first identified UGT in plant that only used UDP-Glc for the biosynthesis of anthocyanins, which were important for pigment accumulation in maize (Dooner and Nelson, 1977). In grape, VvGT1 was a flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase that catalyzed anthocyanins formation during grape fruit ripening (Ford et al., 1998). In model plant Arabidopsis, AtUGT78D2 was identified as flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase by enzymatic activity analysis and T-DNA-inserted mutants (Tohge et al., 2005). Recently, PpUGT78T3 was identified as UDP-glucosyltransferase involved in regulation of flavonol glucosides in response to UV-B (Xie et al., 2022).

In this work, both transcriptomic data and phylogenetic homology of UGT subgroups together with their correlation with flavonoid accumulation patterns in different tissues or under UV-B treatment were comprehensively analyzed for screen of candidate UGTs involved in flavonoid glucosides accumulation. MrUFGT was mainly screened based on phylogenetic homology analysis with group F and correlation relationship between flavonoid glucosides contents and its expression, while MrUGT72B67 was screened based on tissue specific accumulation of flavonoid glucosides and its transcriptomic analysis. Here we demonstrated that MrUFGT was involved in C3Glc accumulation by in vitro and in vivo experimental data. In addition, MrUFGT exhibited activity toward Q resulting in Q3Glc formation. However, Q3Glc accumulation pattern in flowers and leaves was not correlation with gene expression pattern of MrUFGT. This indicating that there might be another UGT member involved in Q3Glc accumulation in flowers and leaves. MrUGT72B67 in group E was found to be involved in Q3Glc accumulation in leaves and flowers by gene expression analysis as well as in vitro and in vivo data. Taken together the results of C3Glc and Q3Glc induced by UV-B treatment (Figure 6C), we concluded that MrUFGT mainly involved in accumulation of C3Glc and Q3Glc in fruit, while MrUGT72B67 mainly involved in accumulation of Q3Glc in flowers and leaves.

UDP-glycosyltransferase members in group F were closely related to flavonoid 3-O-glycoside formation (Ono et al., 2010; Cheng et al., 2014; Cui et al., 2016; Xie et al., 2022). For example, VvGT5 and VvGT6 in group F from Vitis vinifera were identified as flavonol 3-O-glucuronosyltransferase and bifunctional flavonol 3-O-glucosyltransferase/galactosyltransferase in grapevines (Ono et al., 2010). In C. sinensis, CsUGT78A14 and CsUGT78A15 in group F were reported to be responsible for biosynthesis of flavonol 3-O-glucosides and flavonol 3-O-galactosides, respectively (Cui et al., 2016). PpUGT78A2 in group F was identified as a flavonoid 3-O-glycosyltransferase involved in different glycosylation of anthocyanin and flavonol in P. persica (Cheng et al., 2014; Xie et al., 2022). And in M. rubra, four UGT members in group F, i.e., MrUGT78R1, MrUGT78R2, MrUGT78W1, and MrUFGT in the present study, were identified as flavonoid 3-O-glycosyltransferases involved in accumulation of diverse flavonoid glycosides (Ren et al., 2022).

UDP-glycosyltransferase members in group E have been reported with diverse functions in many plants. In Arabidopsis, AtUGT72B1 was identified as a bifunctional O-glucosyltransferase and N-glucosyltransferase involved in metabolism of pollutant 3,4-dichloroaniline (Loutre et al., 2003), and it was also involved in glucose conjugation of monolignols, which play an important role in cell wall lignification in Arabidopsis (Lin et al., 2016). In Lotus japonicus, three UGTs from group E, i.e., UGT72AD1, UGT72AH1, and UGT72Z2, were identified as glucosyltransferases involved in flavonol glucoside/rhamnoside biosynthesis in L. japonicus seeds (Yin et al., 2017).

Key amino acids in glucosyltransferases

Crystal structure analysis of UGTs have showed that last amino acid residue in PSPG-box was critical for glycosyl transfer activity of UGT (Shao et al., 2005; Offen et al., 2006; Osmani et al., 2009). Last amino acid residue of PSPG-box in UDP-glucosyltransferases usually was glutamine (Gln), such as observed in UGT78D2 from Arabidopsis (Tohge et al., 2005), CsUGT78A14 from tea plant (Cui et al., 2016), and FaGT6 and FaGT7 from strawberry (Griesser et al., 2008). Some site-directed mutagenesis indicated the important role of Gln as last amino acid residue in PSPG-box. For example, by replacing Gln382 with His in UBGT from Scutellaria baicalensis, UBGT exhibited remarkable decrease in glucosyltransferase activity (Kubo et al., 2004). In VvGT1, Q375H mutation completely abolished glucosyl transfer activity, and did not improve galactosyl transfer activity (Offen et al., 2006). Q378H substitution for CsUGT78A14 resulted in glucosyl transfer activity markedly reduced, which indicated that Gln was important for flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase activity (Cui et al., 2016).

In the present study, last amino acid residues in PSPG-box were both Gln in MrUFGT (Gln375) and MrUGT72B67 (Gln391). To investigate whether last amino acid residue in PSPG-box was important for glucosyl transfer activity, site-directed mutagenesis of Q375H mutation for MrUFGT and Q391H mutation for MrUGT72B67 were analyzed by enzymatic assay. Results showed that both mutation of Q375H for MrUFGT and Q391H for MrUGT72B67 abolished glucosyl transfer activity. It indicated that Gln as last amino acid residue in PSPG-box were critical for glucosyl transfer activity for MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67.

Conclusion

In the present study, genome-wide analysis was performed for UGT gene family in M. rubra, including polygenetic information, chromosomal distribution, gene duplication mode, and expression pattern. A total of 152 UGT family members were identified in M. rubra genome and clustered into 13 groups based on polygenetic analysis. 139 MrUGT genes marked on eight chromosomes and 13 MrUGT genes located on unmapped scaffolds. Gene duplication analysis indicated that both tandem and proximal duplication were major drivers for MrUGT gene family expansion. Expression analysis indicated MrUGTs played important roles during fruit development and ripening. MrUFGT (MrUGT78A26) and MrUGT72B67 were identified as UDP-glucosyltransferases by in vitro and in vivo experiment which were involved in C3Glc and Q3Glc accumulation in different tissues of M. rubra. In addition, Gln375 and Gln391 were identified as important amino acids for glucosyltransferase activity of MrUFGT and MrUGT72B67, respectively.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are publicly available. This data can be found here: NCBI, SRP386597 and SRP310482.

Author contributions

XL and CR designed the project and drafted the manuscript. CR carried out analyses and experiments with the help of YC, MX, YG, JL, and LX. CS, CX, and KC provided supports to the M. rubra project. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Liang Yan for providing A. tumefaciens p19 strain.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31872067), the Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang Province (2021C02001), and the 111 project (B17039).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.998985/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alseekh S., Perez de Souza L., Benina M., Fernie A. R. (2020). The style and substance of plant flavonoid decoration; towards defining both structure and function. Phytochemistry 174:112347. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2020.112347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondonno N. P., Dalgaard F., Kyro C., Murray K., Bondonno C. P., Lewis J. R., et al. (2019). Flavonoid intake is associated with lower mortality in the Danish Diet Cancer and Health Cohort. Nat. Commun. 10:3651. 10.1038/s41467-019-11622-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles D., Lim E. K., Poppenberger B., Vaistij F. E. (2006). Glycosyltransferases of lipophilic small molecules. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57 567–597. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Jia H., Xing M., Jin R., Grierson D., Gao Z., et al. (2021). Genome-wide analysis of MYB gene family in Chinese bayberry (Morella rubra) and identification of members regulating flavonoid biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 12:691384. 10.3389/fpls.2021.691384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Xie L., Ma Y., Ren C., Xing M., Fu Z., et al. (2019). PpMYB15 and PpMYBF1 transcription factors are involved in regulating flavonol biosynthesis in peach fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67 644–652. 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b04810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputi L., Malnoy M., Goremykin V., Nikiforova S., Martens S. (2012). A genome-wide phylogenetic reconstruction of family 1 UDP-glycosyltransferases revealed the expansion of the family during the adaptation of plants to life on land. Plant J. 69 1030–1042. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04853.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Chen H., Zhang Y., Thomas H. R., Frank M. H., He Y., et al. (2020). TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13 1194–1202. 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J., Wei G., Zhou H., Gu C., Vimolmangkang S., Liao L., et al. (2014). Unraveling the mechanism underlying the glycosylation and methylation of anthocyanins in peach. Plant Physiol. 166 1044–1058. 10.1104/pp.114.246876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks G. E., Hon G., Chandonia J. M., Brenner S. E. (2004). WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14 1188–1190. 10.1101/gr.849004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L., Yao S., Dai X., Yin Q., Liu Y., Jiang X., et al. (2016). Identification of UDP-glycosyltransferases involved in the biosynthesis of astringent taste compounds in tea (Camellia sinensis). J. Exp. Bot. 67 2285–2297. 10.1093/jxb/erw053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooner H. K., Nelson O. E. (1977). Controlling element-induced alterations in UDPglucose: Flavonoid glucosyltransferase, the enzyme specified by the bronze locus in maize. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74 5623–5627. 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey M. O., Mazza M., Krstic M. P. (2007). Development of a stable extract for anthocyanins and flavonols from grape skin. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 58 358–364. 10.1111/1750-3841.12108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C., Xu C. J., Wang Y., Liu W. L., Yin X. R., Li X., et al. (2013). Codon usage patterns in Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra) based on RNA-Seq data. BMC Genomics 14:732. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford C. M., Boss P. K., Hoj P. B. (1998). Cloning and characterization of Vitis vinifera UDP-glucose: Flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase, a homologue of the enzyme encoded by the maize bronze-1 locus that may primarily serve to glucosylate anthocyanidins in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 273 9224–9233. 10.1074/jbc.273.15.9224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman A., Liberman R., Huhman D. V., Carmeli-Weissberg M., Sapir-Mir M., Ophir R., et al. (2013). The molecular and enzymatic basis of bitter/non-bitter flavor of citrus fruit: Evolution of branch-forming rhamnosyltransferases under domestication. Plant J. 73 166–178. 10.1111/tpj.12030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman A., Weisshaus O., Bar-Peled M., Huhman D. V., Sumner L. W., Marin F. R., et al. (2004). Citrus fruit bitter flavors: Isolation and functional characterization of the gene Cm1,2RhaT encoding a 1,2 rhamnosyltransferase, a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of the bitter flavonoids of citrus. Plant J. 40 88–100. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02193.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesser M., Vitzthum F., Fink B., Bellido M. L., Raasch C., Munoz-Blanco J., et al. (2008). Multi-substrate flavonol O-glucosyltransferases from strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) achene and receptacle. J. Exp. Bot. 59 2611–2625. 10.1093/jxb/ern117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry-Kirk R. A., Plunkett B., Hall M., McGhie T., Allan A. C., Wargent J. J., et al. (2018). Solar UV light regulates flavonoid metabolism in apple (Malus × domestica). Plant Cell Environ. 41 675–688. 10.1111/pce.13125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu Y. H., Tagami T., Matsunaga K., Okuyama M., Suzuki T., Noda N., et al. (2017). Functional characterization of UDP-rhamnose-dependent rhamnosyltransferase involved in anthocyanin modification, a key enzyme determining blue coloration in Lobelia erinus. Plant J. 89 325–337. 10.1111/tpj.13387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B., Jin J., Guo A.-Y., Zhang H., Luo J., Gao G. (2014). GSDS 2.0: An upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 31 1296–1297. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irmisch S., Jancsik S., Man Saint Yuen M., Madilao L. L., Bohlmann J. (2020). Complete biosynthesis of the anti-diabetic plant metabolite Montbretin A. Plant Physiol. 184 97–109. 10.1104/pp.20.00522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irmisch S., Jo S., Roach C. R., Jancsik S., Man Saint Yuen M., Madilao L. L., et al. (2018). Discovery of UDP-glycosyltransferases and BAHD-acyltransferases involved in the biosynthesis of the antidiabetic plant metabolite Montbretin A. Plant Cell 30 1864–1886. 10.1105/tpc.18.00406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irmisch S., Ruebsam H., Jancsik S., Man Saint Yuen M., Madilao L. L., Bohlmann J. (2019). Flavonol biosynthesis genes and their use in engineering the plant antidiabetic metabolite Montbretin A. Plant Physiol. 180 1277–1290. 10.1104/pp.19.00254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia H. M., Jia H. J., Cai Q. L., Wang Y., Zhao H. B., Yang W. F., et al. (2019). The red bayberry genome and genetic basis of sex determination. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17 397–409. 10.1111/pbi.12985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb C. A., Kaäser M. A., Kopeckyì J., Zotz G., Riederer M., Pfündel E. E. (2001). Effects of Natural intensities of visible and ultraviolet radiation on epidermal ultraviolet screening and photosynthesis in grape leaves. Plant Physiol. 127 863–875. 10.1104/pp.010373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo A., Arai Y., Nagashima S., Yoshikawa T. (2004). Alteration of sugar donor specificities of plant glycosyltransferases by a single point mutation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 429 198–203. 10.1016/j.abb.2004.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Baldauf S., Lim E. K., Bowles D. J. (2001). Phylogenetic analysis of the UDP-glycosyltransferase multigene family of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 276 4338–4343. 10.1074/jbc.M007447200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Li P., Wang Y., Dong R., Yu H., Hou B. (2014). Genome-wide identification and phylogenetic analysis of Family-1 UDP glycosyltransferases in maize (Zea mays). Planta 239 1265–1279. 10.1007/s00425-014-2050-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. S., Huang X. X., Li Q., Cao Y., Bao Y., Meng X. F., et al. (2016). UDP-glycosyltransferase 72B1 catalyzes the glucose conjugation of monolignols and is essential for the normal cell wall lignification in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 88 26–42. 10.1111/tpj.13229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Wang R., Ren C., Pan Y., Li J., Zhao X., et al. (2022). Two Myricetin-derived flavonols from Morella rubra leaves as potent alpha-glucosidase inhibitors and structure-activity relationship study by computational chemistry. Oxid Med. Cell Longev. 2022:9012943. 10.1155/2022/9012943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Liu Y., Zhan L., Xu C., Jiang H., Zhu C., Sun L., et al. (2020). alpha-Glucosidase inhibitors from Chinese bayberry (Morella rubra Sieb. et Zucc.) fruit: Molecular docking and interaction mechanism of flavonols with different B-ring hydroxylations. RSC Adv. 10 29347–29361. 10.1039/d0ra05015f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loutre C., Dixon D. P., Brazier M., Slater M., Cole D. J., Edwards R. (2003). Isolation of a glucosyltransferase from Arabidopsis thaliana active in the metabolism of the persistent pollutant 3,4-dichloroaniline. Plant J. 34 485–493. 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01742.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R. C., Mok M. C., Mok D. W. S. (1999). A gene encoding the cytokinin enzyme zeatin O-xylosyltransferase of Phaseolus vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 120 553–558. 10.1104/pp.120.2.553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R. C., Mok M. C., Habben J. E., Mok D. W. S. (2001). A maize cytokinin gene encoding an O-glucosyltransferase specific to cis-zeatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 5922–5926. 10.1073/pnas.101128798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeem A., Ming Y., Pengyi H., Jie K. Y., Yali L., Haiyan Z., et al. (2021). The fate of flavonoids after oral administration: A comprehensive overview of its bioavailability. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62 6169–6186. 10.1080/10408398.2021.1898333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu S. S., Xu C. J., Zhang W. S., Zhang B., Li X., Lin-Wang K., et al. (2010). Coordinated regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra) fruit by a R2R3 MYB transcription factor. Planta 231 887–899. 10.1007/s00425-009-1095-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Offen W., Martinez-Fleites C., Yang M., Kiat-Lim E., Davis B. G., Tarling C. A., et al. (2006). Structure of a flavonoid glucosyltransferase reveals the basis for plant natural product modification. EMBO J. 25 1396–1405. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono E., Homma Y., Horikawa M., Kunikane-Doi S., Imai H., Takahashi S., et al. (2010). Functional differentiation of the glycosyltransferases that contribute to the chemical diversity of bioactive flavonol glycosides in grapevines (Vitis vinifera). Plant Cell 22 2856–2871. 10.1105/tpc.110.074625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmani S. A., Bak S., Moller B. L. (2009). Substrate specificity of plant UDP-dependent glycosyltransferases predicted from crystal structures and homology modeling. Phytochemistry 70 325–347. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao X., Li Q., Yin H., Qi K., Li L., Wang R., et al. (2019). Gene duplication and evolution in recurring polyploidization-diploidization cycles in plants. Genome Biol. 20:38. 10.1186/s13059-019-1650-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren C., Guo Y., Xie L., Zhao Z., Xing M., Cao Y., et al. (2022). Identification of UDP-rhamnosyltransferases and UDP-galactosyltransferase involved in flavonol glycosylation in Morella rubra. Hortic. Res. 9:uhac138. 10.1093/hr/uhac138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J., Li Y., Lim E. K., Bowles D. J. (2001). Higher plant glycosyltransferases. Genome Biol. 2 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao H., He X., Achnine L., Blount J. W., Dixon R. A., Wang X. (2005). Crystal structures of a multifunctional triterpene/flavonoid glycosyltransferase from Medicago truncatula. Plant Cell 17 3141–3154. 10.1105/tpc.105.035055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stracke R., Favory J. J., Gruber H., Bartelniewoehner L., Bartels S., Binkert M., et al. (2010). The Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factor HY5 regulates expression of the PFG1/MYB12 gene in response to light and ultraviolet-B radiation. Plant Cell Environ. 33 88–103. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02061.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C., Huang H., Xu C., Li X., Chen K. (2013). Biological activities of extracts from Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra Sieb. et Zucc.): A review. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 68 97–106. 10.1007/s11130-013-0349-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C., Zheng Y., Chen Q., Tang X., Jiang M., Zhang J., et al. (2012). Purification and anti-tumour activity of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside from Chinese bayberry fruit. Food Chem. 131 1287–1294. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.09.121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tohge T., Nishiyama Y., Hirai M. Y., Yano M., Nakajima J., Awazuhara M., et al. (2005). Functional genomics by integrated analysis of metabolome and transcriptome of Arabidopsis plants over-expressing an MYB transcription factor. Plant J. 42 218–235. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02371.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt T., Jones P. (2000). Glycosyltransferases in plant natural product synthesis: Characterization of a supergene family. Trends Plant Sci. 5 1360–1385. 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01720-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F., Su Y., Chen N., Shen S. (2021). Genome-wide analysis of the UGT gene family and identification of flavonoids in Broussonetia papyrifera. Molecules 26:3449. 10.3390/molecules26113449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B., Gao L., Gao J., Xu Y., Liu H., Cao X., et al. (2017). Genome-wide identification, expression patterns, and functional analysis of UDP glycosyltransferase family in peach (Prunus persica L. Batsch). Front. Plant Sci. 8:389. 10.3389/fpls.2017.00389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L., Cao Y., Zhao Z., Ren C., Xing M., Wu B., et al. (2020). Involvement of MdUGT75B1 and MdUGT71B1 in flavonol galactoside/glucoside biosynthesis in apple fruit. Food Chem. 312:126124. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.126124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L., Guo Y., Ren C., Cao Y., Li J., Lin J., et al. (2022). Unravelling the consecutive glycosylation and methylation of flavonols in peach in response to UV-B irradiation. Plant Cell Environ. 45 2158–2175. 10.1111/pce.14323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S., Zhang X., Wen X., Lv Q., Xu C., Sun C., et al. (2016). Purification of flavonoids from Chinese bayberry (Morella rubra Sieb. et Zucc.) fruit extracts and alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activities of different fractionations. Molecules 21:1148. 10.3390/molecules21091148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B., Liu H., Yang J., Gupta V. K., Jiang Y. (2018). New insights on bioactivities and biosynthesis of flavonoid glycosides. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 79 116–124. 10.1016/j.tifs.2018.07.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Q., Shen G., Chang Z., Tang Y., Gao H., Pang Y. (2017). Involvement of three putative glucosyltransferases from the UGT72 family in flavonol glucoside/rhamnoside biosynthesis in Lotus japonicus seeds. J. Exp. Bot. 68 597–612. 10.1093/jxb/erw420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin R., Han K., Heller W., Albert A., Dobrev P. I., Zazimalova E., et al. (2014). Kaempferol 3-O-rhamnoside-7-O-rhamnoside is an endogenous flavonol inhibitor of polar auxin transport in Arabidopsis shoots. New Phytol. 201 466–475. 10.1111/nph.12558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonekura-Sakakibara K., Hanada K. (2011). An evolutionary view of functional diversity in family 1 glycosyltransferases. Plant J. 66 182–193. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04493.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Huang H., Zhang Q., Fan F., Xu C., Sun C., et al. (2015). Phytochemical characterization of Chinese bayberry (Myrica rubra Sieb. et Zucc.) of 17 cultivars and their antioxidant properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16 12467–12481. 10.3390/ijms160612467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are publicly available. This data can be found here: NCBI, SRP386597 and SRP310482.