Abstract

Childhood adversity and its structural causes drive lifelong and intergenerational inequities in health and well-being. Health care systems increasingly understand the influence of childhood adversity on health outcomes but cannot treat these deep and complex issues alone. Cross-sector partnerships, which integrate health care, food support, legal, housing, and financial services among others, are becoming increasingly recognized as effective approaches address health inequities. What principles should guide the design of cross-sector partnerships that address childhood adversity and promote Life Course Health Development (LCHD)? The complex effects of childhood adversity on health development are explained by LCHD concepts, which serve as the foundation for a cross-sector partnership that optimizes lifelong health. We review the evolution of cross-sector partnerships in health care to inform the development of an LCHD-informed partnership framework geared to address childhood adversity and LCHD. This framework outlines guiding principles to direct partnerships toward life course–oriented action: (1) proactive, developmental, and longitudinal investment; (2) integration and codesign of care networks; (3) collective, community and systemic impact; and (4) equity in praxis and outcomes. Additionally, the framework articulates foundational structures necessary for implementation: (1) a shared cross-sector theory of change; (2) relational structures enabling shared leadership, trust, and learning; (3) linked data and communication platforms; and (4) alternative funding models for shared savings and prospective investment. The LCHD-informed cross-sector partnership framework presented here can be a guide for the design and implementation of cross-sector partnerships that effectively address childhood adversity and advance health equity through individual-, family-, community-, and system-level intervention.

Cross-sector partnerships are becoming an essential component of health system efforts to combat health inequities and improve population health and well-being.1,2 The National Academy of Science, Engineering, and Medicine,3 the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation,4 and the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation5 have each recognized that health care alone cannot fully address childhood adversity or achieve health equity across the life course. Health care must partner with other sectors, including public health, education, housing, food, legal, and directly with community organizations, among others, to meaningfully prevent the lifelong consequences of childhood adversity.1

What principles should guide the design of cross-sector partnerships to better address childhood adversity and promote life course health? What foundational structures allow cross-sector partnerships to optimally align services and incentives? What approaches are likely to achieve the greatest impact? Currently, no framework has been widely adopted for designing, implementing, or standardizing cross-sector partnerships to specifically address the lifelong impact of childhood adversity.

Childhood adversity drives inequities in health and well-being across the life course.6–8 The root causes of childhood adversity also are driven by inequities that span generations and are shaped by structural racism and disparities in access to resources, privilege, and power.9,10 The authors of Life Course Health Development (LCHD) theory explain the compounding effects of adversity experienced in childhood on longitudinal health development, positing that health development (1) begins before birth and is sensitive to the quality, intensity, timing, and accumulation of environmental and generational exposures; (2) spans the domains of physical, cognitive, emotional, and social health and integrates these to a unified whole; and (3) is driven by reciprocal interactions among individuals, families, communities, systems, physical and social environments, and historical context.11 Accordingly, interventions to prevent and address the lifelong effects of childhood adversity will be most effective if they integrate services across sectors and move beyond disease prevention to actively develop the health and well-being of children, families, and communities to improve health equity.11–13

It follows from LCHD concepts that cross-sector partnerships and interventions for life course health promotion should be prioritized as follows:14

Timing: Interventions are developmentally and longitudinally focused, and strategically timed.

Focus and scope: Interventions take a holistic, strengths-based, and family-centered approach to building health capacity.

Scale: Interventions act across individuals, families, communities, and systems (eg, health, social, economic, cultural).

Equity: Interventions are designed for equity, incorporate antiracist principles, and redistribute power across sectors and to marginalized communities.

Coordination and funding: Codesigned approaches are coordinated and funded with sustainable integration across sectors.

Together, these concepts can be used to lay a foundation for delivering proactive, holistic, integrated, and equitable services to address adversity and its health consequences.

In this article, we propose an LCHD-informed framework for cross-sector partnerships to address childhood adversity and its lifelong health effects. We review the evolution of cross-sector partnerships to inform the development of a cross-sector partnership model focused on addressing early adversity and improving life course health. We outline core partnership principles rooted in this LCHD view and the foundational structures needed for their implementation. Finally, we identify research priorities to advance cross-sector partnerships aimed at promoting health and well-being across the life course.

LCHD-Informed Cross-Sector Partnerships Solve Problems Health Care Alone Cannot

The health care sector reaches nearly all children and families beginning prenatally, during early childhood, and throughout the life course. This degree of early, continuous reach is unique among child- and family-facing service sectors and positions health care as a hub for cross-sector partnerships. This potential is largely unrealized, however, and health care (like any lone sector) has limitations that prevent its providers from addressing all the causes and longitudinal consequences of childhood adversity. Collaboration between institutions and organizations across multiple sectors is needed to address adversity and optimize life course health trajectories more fully.

Health care traditionally has a narrow scope bounded by identified medical diagnoses, is delivered individually, and is incentivized around episodes of “sick care” rather than health development early in life.13 The majority of resources in health care go to the end of life, likely blunting their impact on outcomes relative to resources invested early in life.15 These limitations of traditional health care are at odds with the LCHD intervention approach, which invests early and longitudinally to optimize health capacity; recognizes that individual outcomes are shaped by family, household, community, historical, and policy environments; and requires cross-sector partnerships capable of addressing a broad range of individual, social, and structural health determinants.11–13

Pediatric and obstetric clinicians have pioneered various cross-sector partnerships from within health care and alongside experts from other fields.16–20 Although the promise of innovative cross-sector models has generated enthusiasm to address childhood adversity and social health determinants, the absence of a standard framework has limited the comparability, scale, and spread of successful models. Without more robust tools to design cross-sector partnerships and coordinated service delivery, health care’s approach to addressing childhood adversity has, in many instances, resembled the traditional medical model of diagnosis and referral for subspecialty treatment.

There has been a recent growth of cross-sector approaches, including clinical screening for social risks and referral to resources outside the health care system (eg, through the development of social needs screening tools and compilation of community resource libraries).21–23 Such “awareness and assistance” approaches, as defined by the 2019 proceedings on social care from the National Academy of Science, Engineering, and Medicine,3 help health care providers to address social risks and needs. However, without structural changes to address the root causes of childhood adversity, which require partnership across relevant sectors, this approach may be hamstrung by traditional health care’s limitations and fall short of improving health along the life course.

Limitations with many prevailing approaches to addressing childhood adversity and upstream health determinants include the following:

Timing (reactive and sporadic): The effects of adversity on health and development begin before birth, become chronic, and compound throughout the life course. However, current tools designed for awareness of and assistance for child adversity (eg, referral to behavioral health specialists) are geared to respond to existing trauma.21 This approach leads to missed opportunities to target certain critical periods of development, preempt adversity, and prevent adversity’s effects on life course health and well-being. Moreover, routine health care encounters alone are too brief and episodic to allow for meaningful prevention of the complex longitudinal effects of childhood trauma, poverty, and racism.

Focus and scope (narrow, downstream, deficit-based): Authors of existing screening tools flatten the many dimensions of social health into narrow, downstream, deficit-based categories (eg, housing instability, food insecurity) in an attempt to “diagnose” varieties of childhood adversity. Although tools designed for awareness and assistance may be necessary or helpful, they are not sufficient to address whole people, families, or communities and their changing goals over time. Screening for specific social conditions could lead to narrow, condition-specific responses, devalue a holistic experience, and fail to build on existing protective factors that strengthen LCHD.

Scale (individuals not communities): Individualizing the assessment of and response to adversity limits opportunities to center family and community as partners in health development interventions and fails to act on the macrosystems and structures that perpetuate adversity and inequities. Aggregating individual-level data and reframing it to unveil family- and community-level phenomena can also unveil opportunities to identify and address systemic root causes of population health risk, such as inequitable policies and structural racism.

Equity (goal, not practice): By addressing adversity and social needs, health care providers aim to close equity gaps created by systemic injustice and oppression and prevent their downstream effects on health. However, this intent is rarely integrated throughout the approach. Without meaningful connection and coordination with community organizations, power and resource sharing across sectors, centering families and community voices, or clearly understanding and addressing their own contributions to inequity, health care providers cannot expect to meaningfully address adversity and contribute to building equity.

Additional problems with overly medicalized approaches stem from limitations in how they are structured:

5. Coordination (siloed, not integrated): Greater coordination and capacity for communication across sectors is often needed to ensure that families successfully connect to quality services. Referrals made without capacity for communication between partners can lead to a misunderstanding of eligibility criteria or capacity to assist. This practice may amplify structural navigational barriers and prevent individuals from accessing supports because of mismatched expectations among clinician, family, and resource partners around the process and outcome of referrals. These barriers can lead to so-called “lose-lose-lose scenarios,”24 particularly for high-demand, low-capacity needs, including housing insecurity where families are sent to seek services that may not be aligned with addressing their needs; community agencies, already stretched thin, bear the responsibility of turning these families away; and families, health care professionals, and service partners waste time because of the mismatched expectations. This experience can ultimately weaken patients’ trust in all systems involved without substantively addressing their needs.

6. Funding (short term, wrong incentives): Sectors outside health care address various aspects of childhood adversity to produce health care value, among many other benefits (eg, the lifelong impacts that education has on health).25 Yet, the resulting cost savings to health care are not shared, which is termed the “wrong-pocket problem.”26 Sectors that do not share in the savings have limited capacity to partner beyond their core services. Preventive investments made early in an individual’s life lead to downstream cost savings, but there are few effective mechanisms to reinvest dividends upstream where most effective, termed the “long-pocket problem.”

In short, health care systems cannot diagnose and treat the myriad of life course health risks in isolation. Approaches that do not meaningfully, equitably, and sustainably align across sectors will be similarly unsuccessful. Health care and the funding and service structures that shape it must move toward a more seamless partnership across sectors to preventively and holistically address early adversity and other risks to LCHD.

Life Course Health Concepts and Emerging Cross-Sector Partnership Models

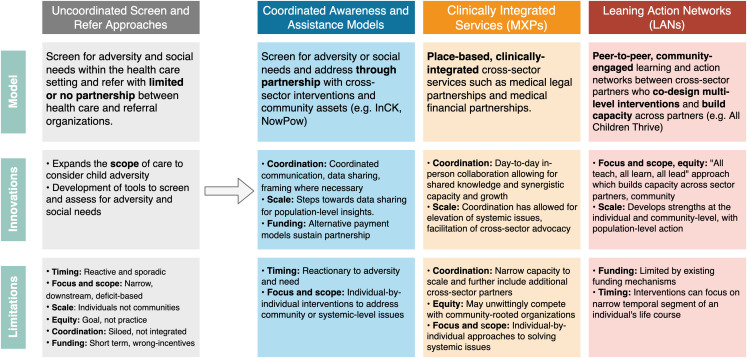

Attempts to address the aforementioned limitations have led to the emergence of promising cross-sector models aimed at curbing the lifelong consequences of childhood adversity. Key innovations used in these models align with several LCHD concepts. Figure 1 is a summary of prominent cross-sector partnership models and how they innovate beyond traditional health care’s limitations around the timing, focus, scope, scale, equity of interventions, and the coordination and funding to support them.

FIGURE 1.

Innovations and limitations of prevailing cross-sector partnership models. InCK, Integrated Care for Kids.

Coordinated Awareness and Assistance Models

Coordinated awareness and assistance models are used to leverage deeper relationships with partner organizations across sectors to address the complex nature of adversity and need for personalization. The models take on different forms, depending on the needs of communities and capabilities of partners involved, but they follow the general approach of screening for adversity from within health care followed by coordination of services with cross-sector partners. Examples of these models include the Accountable Health Communities Model, funded by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation, which has emerged as a flagship approach for structuring cross-sector relationships and coordinating referrals to address health inequities5; NowPow, a community-driven digital referral platform that uses evidence-based matching and referrals (1-way, tracked, and coordinated) of patients to a curated network of nonmedical resources and organizations16; and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services–funded Integrated Care for Kids program, which aims to address child adversity by bolstering care coordination through reimbursable bundles of physical, behavioral, and social health services.27

Strengths of these models include improved multidirectional communication between medical and nonmedical partners and mutual understanding of service capacity, care processes, and data sharing. Communication and alignment allow for shared framing of problems and solutions and can inform innovative funding mechanisms, such as pooled funding for population health outcomes. The digital community resource platforms that have emerged from these partnerships have the potential to generate actionable population and policy-relevant insights that health systems and community-based organizations can use to broaden their impact.

Despite these innovations, many models retain the same limitations around timing, scope, and scale as the traditional medical model. With some important exceptions of models with prevention built into their approaches, they are typically positioned to mitigate harm only once it has already occurred and they continue to address individual patient needs driven by structural causes.

Clinically Integrated Services: Medical-X-Partnerships

Clinically integrated cross-sector partnerships bring nonmedical professionals directly into the clinical setting. The intent is to better coordinate services and more immediately address adversity with minimal referral barriers by leveraging time, space, funding, and trust afforded by integration with health care. Examples include medical teams partnering with legal services (medical legal partnerships),28 financial services (medical financial partnerships),18 and early developmental intervention services (eg, HealthySteps).29 By being physically colocated and connected with the health system, medical-X-partnerships (MXPs) address many of the service coordination, resource sharing, and integration barriers faced by external community partnerships.18 In this way, certain MXPs can partner more closely and significantly scale action to identify actionable population-level patterns, elevate systemic issues, and facilitate cross-sector advocacy and policy change.30

The key limitations of MXPs stem from a narrow capacity to scale how space, time, and funding are shared, which limits capacity to scale partnerships and their impact. To further scale MXPs, additional resources, flexible funding approaches that overcome funding limitations (eg, restrictions on the use of health system community benefit dollars), and more equitable power sharing where incentives are not aligned to support these efforts are required.18 Moreover, by being clinically integrated, services may not have a direct presence in the community, as health care often does not, and may unwittingly compete with resources that promote investment and growth from within the community. Although there are clear exceptions, as previously indicated, the scale of interventions is commonly limited to individual approaches.

Learning Action Networks

The approach of learning action networks (LANs) is to address child adversity by first building effective relationships across sectors and conceptualize shared problems, solutions, and outcomes. With those outcomes in mind, key stakeholders turn shared frameworks into action through codesigned interventions. Taking an “all teach, all learn, all lead” approach, many LANs center on and uplift youth, family, and community voices. By design, they frame and foster an operating model that is population focused, community engaged, and equity oriented.

All Children Thrive (ACT) networks across the country and internationally exemplify this model of cross-sector codesign and shared action aimed at addressing population-level health development and equity.19 For example, ACT-Long Beach is a partnership among families, local nonprofits, schools, government, and health care that aims 1) to increase the health of children from birth until age 8; 2) to improve their ability to learn successfully; 3) to ensure children grow up in safe environments; and 4) to support the social, emotional and mental health needs of children and their families.31

ACT-Cincinnati has the shared purpose to “help Cincinnati’s 66 000 children be the healthiest in the nation through strong community partnerships.”32 Aligned on this shared objective, the learning network builds capacity among partners and distributes responsibility and accountability. Approaches include proactive patient outreach to prevent adverse outcomes, cross-sector patient handoffs, and use of real-time data streams for population-level hotspotting. Through these efforts, the ACT-Cincinnati network realized an ∼20% decrease in bed-days for children from historically marginalized neighborhoods.19 The network now is providing a scaffold to spread and scale their learnings.

Although effective at building more meaningful partnerships across sectors and facilitating multilevel responses, LANs retain challenges around timing and funding of action. Activities build capacity across sectors and may target upstream drivers of adversity, but many still focus on narrow temporal segments of the life course. Moreover, prevailing funding models are not geared to support such partnerships, leading to reliance on philanthropy or grants and active partners to sustain function or further innovation.

A Framework for LCHD-Informed Cross-Sector Partnerships: Guiding Principles and Foundational Structures

Emerging cross-sector partnership models reflect how aligning the timing, focus, scope, scale, equity, coordination, and funding of interventions with longitudinal health development mitigate some of the limitations of traditional health care approaches. Several key advances in cross-sector partnerships, including a greater focus on prevention, more equitable relational structures, and population-level action, align well with core LCHD concepts. The LCHD paradigm, therefore, offers a useful structure for a fuller framework to guide the further development of cross-sector partnerships in addressing childhood adversity.

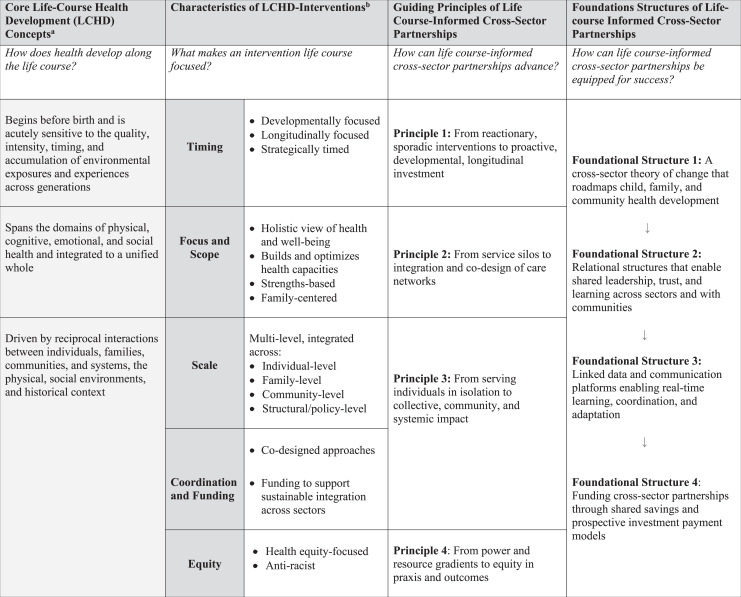

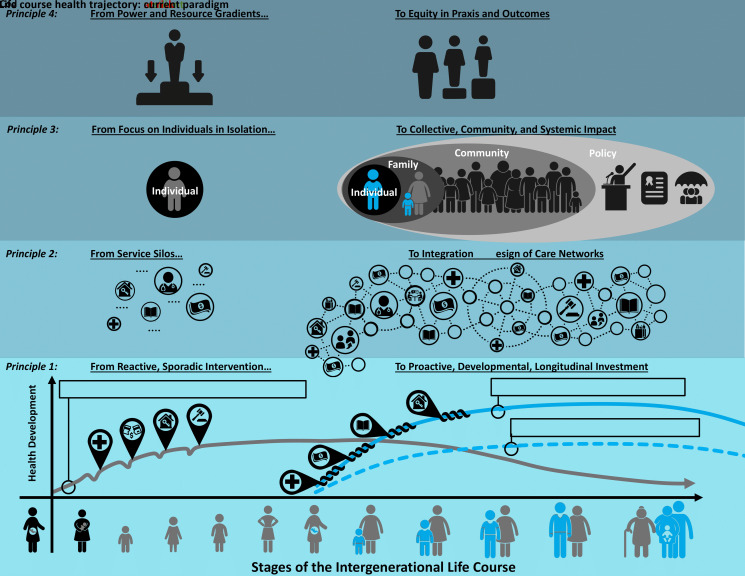

Next, we propose principles to guide how cross-sector partnerships can approach their work to be more life course informed and the foundational structures needed to optimize and sustain their implementation. Together, the principles and foundational structures constitute a proposed framework meant to guide the implementation of, and organize further research and innovation around, LCHD-informed cross-sector partnerships to address child adversity and promote equity (Figs 2 and 3).

FIGURE 2.

Principles to guide the conceptual design of LCHD-informed cross-sector partnerships.

FIGURE 3.

Framework for LCHD-informed cross-sector partnerships: principles and foundational structures. 14

Principle 1: Move From Reactive, Sporadic Intervention to Proactive, Developmental, Longitudinal Investment

Cross-sector partnerships should broaden the focus and timing of interventions to invest proactively and act longitudinally to develop health throughout the life course. Interventions to address child adversity should therefore move from sick care (eg, responding to trauma) to anticipate, invest, and prevent (eg, preventing the drivers of trauma). Aligning with LCHD principles, systems of care should move from episodic interactions with families with limited continuity to longitudinal partnerships and action. Through aligning the timing and focus, cross-sector partners will be better positioned to prevent the consequences of adversity and promote health equity throughout the life course.

Principle 2: Move From Service Silos to Integration and Codesign of Care Networks

To form systems that buffer against multiple drivers of adversity, individual sectors can no longer afford to work in functional silos. Cross-sector partners must identify meaningful approaches to broaden their scope and coordination to integrate missions and services through codesigned networks of care. Although leveraging existing assets in communities is critical for building trust and sustainability,33 simply cobbling together existing interventions across sectors is not enough. Borrowing from the lessons of ACT networks, careful thought should be given to redesigning and codesigning strengths-based approaches that address adversity and promote holistic health development across domains of physical, behavioral, and social health.

Principle 3: Move From Serving Individuals in Isolation to Having a Collective, Community, and Systemic Impact

The root causes of individual life course health inequity cannot be addressed without broadening the scale of action to reshape the household, community, social, and policy environments in which individuals develop or the historical context they are rooted in. Cross-sector partnerships should therefore include collective impact approaches that uplift individuals-, families-, and communities-in-environment and prioritize an all teach, all learn, all lead mentality. Policy-level structural approaches to promote equitable lifelong health development (eg, the Earned Income Tax Credit) should also be prioritized as LCHD-informed cross-sector interventions.34,35 To guide action across the multiple environments that shape health, partnerships will be best served to listen closely to and prioritize the lived experience, voice, and goals of communities.

Principle 4: Move From Power and Resource Gradients to Equity in Praxis and Outcomes

Achieving equity should be conceived as operational processes in addition to aiming cross-sector partnerships toward the outcome of health equity. In this sense, equity and antiracism practices should be embedded throughout how cross-sector partnerships operate, including deciding (1) who is involved (eg, centering the voices of communities), (2) who holds power and how power is distributed (eg, distributed leadership and governance), (3) partnership aims (eg, equity-based process measures), (4) how success is measured (eg, equity-based outcome measures), and (5) how resources are shared.36,37 Partnerships must aim to also focus directly on structural drivers of adversity, including structural racism, which involves taking steps to recognize and address partners’ own contributions to systemic inequities.36

Although the guiding principles help to conceptually define the aims of cross-sector partnerships in our LCHD-informed framework, foundational structures are necessary to address how cross-sector partners “roadmap” their activities, relate to one another, share information, and are funded (Fig 3). We illustrate next the key structures needed to equip cross-sector partnerships for success and sustainable scale.

Foundational Structure 1: A Cross-Sector Theory of Change That Roadmaps Child, Family, and Community Health Development

As sectors shift from silos to integrated partnerships, there must first be an intentional conversation between partners to develop a shared theory of change. A theory of change should explain the evidence-based processes for how to achieve and measure aligned, coordinated, efficient, and effective action. Key domains in the theory should include how partners (1) conceptualize life course adversities, their drivers, and their impact; (2) define roles in addressing adversities and how they are integrated; (3) expect to influence outcomes; (4) define metrics of progress; and (5) maintain accountability to organizational, power, and resource equity. This theory of change is a shared roadmap partners can use to identify, prioritize, implement, and evaluate cross-sector interventions for families along the life course. Integrating family and community voices in the development and ownership of the theory of change is essential to create a common language shared by all parties and to ensure that priorities align with the needs and goals of families.

Foundational Structure 2: Relational Structures That Enable Shared Leadership, Trust, and Learning Across Sectors and With Communities

Leaders of cross-sector partnership and accountability structures should more equitably distribute resources, representation, and power across sectors and with communities. Implementation of distributed relational structures (eg, horizontal coordination, networked governance)37 allows for an all teach, all learn, all lead practice that fosters (1) understanding and respect for how partners and the community currently operate and their respective priorities; (2) trust across sectors and rebuilding of trust with communities where lost; (3) learning that leads to codesigned, co-owned innovations; and (4) opportunities for reflection, shared decision-making, and accountability to stakeholders and communities. Establishment of leadership, trust, and shared accountability is not a one-time activity at the outset of partnership. Instead, this intentional partnership requires active, continuous investment that revisits partnership foundations and resists natural tendencies for inequitable shifts in power.

Foundational Structure 3: Linked Data and Communication Platforms Enabling Real-Time Learning, Coordination, and Adaptation

Mechanisms for real-time data sharing, communication, coordination, and adaptation are essential to the effectiveness of LCHD-informed cross-sector partnerships. Innovation and incentives are needed to further the use of digital platforms not only to align daily operations but also to support partnered impact evaluation, evidence generation for policy change, and population-level monitoring to identify shifts in community needs requiring adaptation.3 The data collected and shared (from health care, education, mental health, social services) should be accessible where appropriate and actionable to partners while maintaining rights to and respect of individual privacy.38 New infrastructures and approaches will be needed to address challenges around data consistency, interoperability, and differing legal requirements across sectors (eg, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act).39 Regular reflection on shared data can form the foundation for data-driven growth and evolution of LCHD-informed cross-sector partnerships.40

Foundational Structure 4: Funding Cross-Sector Partnerships Through Shared Savings and Prospective Investment Payment Models

Innovative funding structures are needed to sustain cross-sector partnerships and should be designed to avoid additional power inequities while efficiently distributing resources for impact. Directions for cross-sector funding models should assure that returns accrue to sectors making the initial investments, addressing the "wrong-pocket" and "long-pocket problems."41,42 Alternative payment models may use mechanisms such as bundled payments that target life course health promotion processes and outcomes, capitation to maintain funding continuity, risk adjustment to ensure payment equity relative to service complexity, or strategically targeted investments in key infrastructure to enhance cross-sector service capacity and capability.41,42 The latter mechanism requires a funder that understands not only the costs and value of each sector partner (including community members) but also the potential value of activities only possible through new applications of the partnership and long-term returns that might take decades to realize. The shared data platforms described previously can be a guide for determining this cross-sector and longitudinal value and transparent funding distribution.

Measuring Impact: Implications for Future Research and Innovation

Despite broad enthusiasm for cross-sector partnerships to address childhood adversity and promote population health equity, comparable data linked to collaboration outcomes are sparse, limiting the ability to compare the efficacy of partnerships’ design, implementation, and scale.43 As highlighted here, innovations and incentives are needed, particularly around digital platforms and funding infrastructures, to support the impact and sustainability of cross-sector partnerships. We offer with this framework a foundation and directions for future evidence generation around optimal partnership design, implementation, resourcing, and impact over the short, intermediate, and long term. To ensure rigorous evaluation of LCHD-informed cross-sector partnerships, guidelines (similar to Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence)37,44,8,45 could help to standardize reporting of partnership aims, composition, implementation, outcomes, and equity metrics. Such a research agenda is essential to advance the science of LCHD-informed cross-sector partnerships and scale what works to mitigate adversity and promote population health equity.

Conclusions

LCHD-informed cross-sector partnerships hold great promise that has yet to be fully realized in the absence of a standard framework to guide their design, implementation, and scale. The framework presented in this article is a starting point for this nascent field of multisector life course interventions. We envision that this kind of partnership could be especially valuable in the delivery of preventive, holistic, and equitable services to address adversity and its health consequences at the individual, family, community, and system levels.

Glossary

- ACT

All Children Thrive

- LAN

learning action network

- LCHD

Life Course Health Development

- MXP

medical-X-partnership

Footnotes

FUNDING: This work was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services under award UA6MC32492, the Life Course Intervention Research Network. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Dr Schickedanz was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (grant K23HD099308). Dr Lindau was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01AG064949, R01MD012630, R01AG064949, R01MD012630, R01DK127961-01, and R01HL150909. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of any of the sponsors.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES: Dr Lindau directed a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Innovation Health Care Innovation Award (1C1CMS330997-03) called CommunityRx. This award required development of a sustainable business model to support the model test after award funding ended. To this end, Dr Lindau is founder and co-owner of NowPow, LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Unite Us, LLC. Neither The University of Chicago nor University of Chicago Medicine endorses or promotes any NowPow Entity or its business, products, or services. The other authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Mr Liu and Dr Schickedanz conceptualized the manuscript, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Beck, Lindau, Holguin, Kahn, Fleegeler, and Halfon, and Ms Henize conceptualized the manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1. Yaeger JP, Kaczorowski J, Brophy PD. Leveraging cross-sector partnerships to preserve child health: a call to action in a time of crisis. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(12):1137–1138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Towe VL, Leviton L, Chandra A, Sloan JC, Tait M, Orleans T. Cross-sector collaborations and partnerships: essential ingredients to help shape health and well-being. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(11):1964–1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Integrating Social Needs Care into the Delivery of Health Care to Improve the Nation’s Health . Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2019 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chandra A, Acosta J, Carman KG, et al. Building a national culture of health: background, action framework, measures, and next steps. Rand Health Q. 2017;6(2):3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alley DE, Asomugha CN, Conway PH, %Sanghavi DM. Accountable health communities--addressing social needs through Medicare and Medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(1):8–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shonkoff JP, Garner AS; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care; Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics . The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):e232–e246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nelson CA, Scott RD, Bhutta ZA, Harris NB, Danese A, Samara M. Adversity in childhood is linked to mental and physical health throughout life. BMJ. 2020;371: m3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Metzler M, Merrick MT, Klevens J, Ports KA, Ford DC. Adverse childhood experiences and life opportunities: Shifting the narrative. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2017;72:141–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Giano Z, Wheeler DL, Hubach RD. The frequencies and disparities of adverse childhood experiences in the US. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shonkoff JP, Slopen N, Williams DR. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the impacts of racism on the foundations of health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;42: 115–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Halfon N, Forrest CB. The emerging theoretical framework of life course health development. In: Halfon N, Forrest CB, Lerner RM, Faustman EM, eds.. Handbook of Life Course Health Development. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018:19–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Halfon N, Hochstein M. Life course health development: an integrated framework for developing health, policy, and research. Milbank Q. 2002;80(3):433–479, iii [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Halfon N, Larson K, Lu M, Tullis E, Russ S. Lifecourse health development: past, present and future. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(2):344–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Russ S. What makes an intervention a life course intervention? Pediatrics. 2022;149(suppl 5):e2021053509D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alemayehu B, Warner KE. The lifetime distribution of health care costs. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(3):627–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tung EL, Abramsohn EM, Boyd K, et al. Impact of a low-intensity resource referral intervention on patients’ knowledge, beliefs, and use of community resources: results from the CommunityRx trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(3):815–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kelleher K, Reece J, Sandel M. The Healthy Neighborhood, Healthy Families initiative. Pediatrics. 2018;142(3): e20180261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bell ON, Hole MK, Johnson K, Marcil LE, Solomon BS, Schickedanz A. Medical-financial partnerships: cross-sector collaborations between medical and financial services to improve health. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(2):166–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beck AF, Anderson KL, Rich K, et al. Cooling the hot spots where child hospitalization rates are high: a neighborhood approach to population health. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(9): 1433–1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beck AF, Tschudy MM, Coker TR, et al. Determinants of health and pediatric primary care practices. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e201553673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Garg A, Cull W, Olson L, et al. Screening and referral for low-income families’ social determinants of health by US pediatricians. Acad Pediatr. 2019; 19(8):875–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gottlieb LM, DeSalvo K, Adler NE. Healthcare sector activities to identify and intervene on social risk: an introduction to the American Journal of Preventive Medicine supplement. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6 suppl 1):S1–S5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fleegler EW, Bottino CJ, Pikcilingis A, Baker B, Kistler E, Hassan A. Referral system collaboration between public health and medical systems: a population health case report. In: NAM Perspectives. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; 2016. Available at: https://nam.edu/referral-system-collaboration- between-public-health-and-medical- systems-a-population-health-case-report/. Accessed June 12, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kreuter M, Garg R, Thompson T, et al. Assessing the capacity of local social services agencies to respond to referrals from health care providers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(4):679–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hahn RA, Truman BI. Education improves public health and promotes health equity. Int J Health Serv. 2015;45(4):657–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Butler S. How “wrong pockets” hurt health. Available at: https://jamanetwork.com/channels/health-forum/fullarticle/2760141?resultClick=1. Accessed April 6, 2022

- 27. Integrated Care for Kids (InCK) Model . Available at: https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/integrated-care-for-kids-model. Accessed June 12, 2021

- 28. Gutierrez G, Saleeby E, Celaya A, Clouse J, Hoffman C, Kornberg J. Medical-legal partnerships: supporting the legal needs of women in their perinatal care [16F]. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(1):64S–65S [Google Scholar]

- 29. Valado T, Tracey J, Goldfinger J, Briggs R. HealthySteps: transforming the promise of pediatric care. Future Child. 2019;29:99–122 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Beck AF, Klein MD, Schaffzin JK, Tallent V, Gillam M, Kahn RS. Identifying and treating a substandard housing cluster using a medical-legal partnership. Pediatrics. 2012;13(5):831–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. California Accountable Communities for Health Initiative . All Children Thrive Long Beach. Available at: https://cachi.org/profiles/long-beach. Accessed June 30, 2021

- 32. Kahn RS, Iyer SB, Kotagal UR. Development of a child health learning network to improve population health outcomes; presented in honor of Dr Robert Haggerty. Acad Pediatr. 2017; 17(6):607–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lindau ST, Makelarski JA, Chin MH, et al. Building community-engaged health research and discovery infrastructure on the South Side of Chicago: science in service to community priorities. Prev Med. 2011;52(3–4): 200–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brown AF, Ma GX, Miranda J, et al. Structural interventions to reduce and eliminate health disparities. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S1):S72–S78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Simon D, McInerney M, Goodell S. The earned income tax credit, poverty, and health. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20180817.769687/full/. Accessed October 11, 2021

- 36. Parsons A, Unaka NI, Stewart C, et al. Seven practices for pursuing equity through learning health systems: notes from the field. Learning Health Syst. 2021;5(3):e10279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mendoza X. Relational strategies for bridging and promoting cross-sector collaboration [abstract]. Int J Integr Care. 2009;9(5). [Google Scholar]

- 38. Price WN II, Cohen IG. Privacy in the age of medical big data. Nat Med. 2019;25(1): 37–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schmit C, Kelly K, Bernstein J. Cross sector data sharing: necessity, challenge, and hope. J Law Med Ethics. 2019; 47(suppl 2):83–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Beck AF, Hartley DM, Kahn RS, et al. Rapid, bottom-up design of a regional learning health system in response to COVID-19. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(4):849–855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Counts NZ, Roiland RA, Halfon N. Proposing the ideal alternative payment model for children. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(7):669–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Counts NZ, Ge D, Hawkins JD, Leslie LK, et al. Redesigning provider payments to reduce long-term costs by promoting healthy development [discussion paper]. In: NAM Perspectives. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; 2018:11 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Alderwick H, Hutchings A, Briggs A, Mays N. The impacts of collaboration between local health care and non-health care organizations and factors shaping how they work: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D; CONSORT Group . CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(11):726–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(12): 986–992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]