Abstract

POGZ is a pogo transposable element derived protein with multiple zinc finger domains. Many de novo loss-of-function (LoF) variants of the POGZ gene are associated with autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders. However, the role of POGZ in human cortical development remains poorly understood. Here we generated multiple POGZ LoF lines in H9 human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) using CRISPR/CAS9 genome editing. These lines were then differentiated into neural structures, similar to those found in early to mid-fetal human brain, a critical developmental stage for studying disease mechanisms of neurodevelopmental disorders. We found that the loss of POGZ reduced neural stem cell proliferation in excitatory cortex-patterned neural rosettes, structures analogous to the cortical ventricular zone in human fetal brain. As a result, fewer intermediate progenitor cells and early born neurons were generated. In addition, neuronal migration from the apical center to the basal surface of neural rosettes was perturbed due to the loss of POGZ. Furthermore, cortical-like excitatory neurons derived from multiple POGZ homozygous knockout lines exhibited a more simplified dendritic architecture compared to wild type lines. Our findings demonstrate how POGZ regulates early neurodevelopment in the context of human cells, and provide further understanding of the cellular pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental disorders associated with POGZ variants.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders, CRISPR/CAS9 genome editing, neurodevelopment, neuronal differentiation, neuronal migration

1. Introduction

The pogo transposable element derived with zinc finger domains (POGZ) gene encodes a heterochromatin protein 1α (HP1α) binding protein1-3. It contains a cluster of zinc finger domains, a helix-turn-helix (HTH) centromere protein-B-like DNA binding (CENP-DB) domain, an HP1-binding zinc finger binding motif (HPZ), and a DDE domain2. The HPZ motif is essential for binding of HP1α (also known as CBX5) during mitosis. When POGZ expression is knocked down in HeLa cells, the dissociation of HP1 from the chromosome is suppressed2, which in turn inhibits both cell division and growth, likely leading to microcephaly among some patients4-8. The transposase-derived DDE domain near the C-terminal end interacts directly with lens epithelium-derived growth factor (PSIP1; a.k.a., LEDGF or p75)9, a transcriptional co-activator highly expressed in both fetal and adult brain10. POGZ also interacts with a repressive histone modification marker histone 3 lysine 9 trimethylation (H3K9me3)3,11, a chromatin state that is inaccessible to transcription factors and arises upon stem cell differentiation and lineage specification12.

POGZ is constitutively expressed in most tissues, with especially strong expression in the human fetal and adult central nervous system (CNS), including cerebral cortex, cerebellum, spinal cord, hippocampus and basal ganglia6,13,14. POGZ is co-expressed with other autism risk associated genes involved in chromatin remodeling and transcriptional regulation in the human fetal brain15,16. These expression profiles reinforce the important roles of POGZ during human cortical development. Moreover, recent studies suggest that POGZ regulates neural differentiation of mouse neural stem cells (NSCs) through chromatin-silencing pathways14,17. Collectively, these findings indicate that POGZ is an integral part of heterochromatin binding protein complexes required for cell cycle progression and gene regulation during human cortical development.

POGZ is one of the genes most commonly associated with recurrent de novo variants in patients with neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs)18, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and intellectual disability6-8,19-21, as well as psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia22. POGZ variants are also associated with White–Sutton syndrome (WHSUS), a rare NDD characterized by developmental delay, intellectual disability (ID), dysmorphisms, autistic features, brain anomalies and obesity23. Microcephaly has been reported in some individuals with POGZ mutations6,8, as has epilepsy5. Despite some clinical similarities, there is large phenotypic heterogeneity even among individuals with similar types of POGZ mutations17. Human POGZ gene variants have been found in nearly all exons except 1-4 and 116,23. The vast majority of de novo POGZ mutations identified in patients with NDDs are either nonsense or frameshift6,8,14 resulting in decreased POGZ protein levels. Recent studies using mouse models have shown that loss of POGZ impairs embryonic cortical development through distinct cellular mechanisms14,17,24. POGZ shRNA knockdown using in utero electroporated mouse models reduces the intermediate neural progenitor cell pool and upper layer neurons14. Homozygous null mice with conditional deletion of POGZ in NSCs develop increased intermediate neural progenitor cells but reduced cell survival during neural differentiation17. Notably, some heterozygous mice show only subtle phenotypes17,24. A patient iPSC model with a POGZ de novo missense mutation has shown increased NSC proliferation and neurosphere size14. These findings have expanded our knowledge of POGZ function in neurodevelopment, but show variable phenotypes in different model systems.

Human brain development differs from that of rodent in important aspects. These differences include larger brain volume, greater diversity of cell types, and an expanded forebrain subventricular zone (SVZ) in humans25-27. Human-based and mouse-based models do not always show cohesive phenotypes when modeling human brain development and neuronal activities14,28,29. To better understand the role of POGZ in human neurodevelopment and related disorders, human-based model systems that can recapitulate human cortical developmental processes are needed to complement animal models29. The goal of this study is to determine the impact of a complete loss of POGZ on hESC-derived cortical neuron development. Similar approaches have been taken to study other ASD associated genes such as CHD8, which lays a foundation for further functional studies of patient mutations30,31.

Here we generated a set of POGZ LoF hESC models including heterozygous and homozygous knockouts using CRISPR/CAS9 genome editing. We subsequently differentiated them into neural structures similar to the neural architecture of the early to mid-fetal human brain, a key stage for studying NDD mechanisms. We found that POGZ is critical for proliferation and lineage progression of NSCs in human cortical-like rosettes. POGZ is also essential for the subsequent migration and process outgrowth of their neuronal progeny.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. hESC culture

H9 (WA09; WiCell) hESC lines were maintained in feeder-free conditions on Geltrex-coated plates in TeSR-E8 maintenance medium (05940; STEMCELL technologies, Vancouver, Canada) at 37 °C with controlled humidity and 5% CO2. Cells were routinely passaged with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, Lonza) at ~80% confluency. Briefly, cells were washed with 1×DPBS without calcium and magnesium and incubated with 1 mM EDTA for 2 min. After EDTA was removed, cells were suspended with TeSR-E8 medium supplemented with 10 μM ROCK inhibitor Y27632 (Tocris Bioscience) and transferred to freshly coated plates at a dilution of 1:10 to 1:20. ROCK inhibitor was removed from the culture 24 h after each passage. Mycoplasma testing was carried out periodically by PCR amplifying ribosome DNA of mycoplasma using the primer set (5’-TGCACCATCTGTCATTCTGTT-3’ and 5’-GGGAGCAAACAGGATTAGATA-3’). Two isogenic controls lines (CTL1/WA09 and CTL3/PG22-4), one heterozygous knockout line (POGZ+/−/PG3), and three homozygous knockout lines (POGZ −/−-1/PG9-3, POGZ −/−-2/PG9-4, POGZ −/−-3/PG22-13) were used in the current study. All cell lines used underwent single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array using the Illumina Infinium CoreExome-24 v1.2 kit. Data analyses were done using genome studio.

2.2. CRISPR/CAS9 genome editing

We followed an established CRISPR gene editing protocol to generate both POGZ homozygous and heterozygous insertions/deletions (indels) in H9 hESCs32. Single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting two different exons of the POGZ gene were designed using the UCSC genome browser on Human Feb. 2009 (GRCh37/hg19) Assembly (https://genome.ucsc.edu/), and were cloned into either pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP vector (PX458; Addgene #48138) or pSpCas9(BB)-2A-Puro V2.0 vector (PX459, Addgene#62988).

To make homozygous mutations, we used two sgRNA sequences: 5’-TCGCTCCTCACTCTACTCTG-3’ and 5’-ATCTACCTCAGAGTAGAGTG -3’, each targeting exon 12 separately. H9 hESCs were dissociated into single cells using accutase (Innovative cell, AT104) and plated at ~30% confluency in TeSR-E8 medium supplemented with 10 μM Y27632 on Matrigel-coated plates (Corning, 354230). The next day H9 hESCs were pre-incubated in mTeSR1 (Stemcell Technologies, 85850) with 10 μM Y27632 for 2 h prior to transfection with 1.8 μg of sgRNA and 0.2 μg of puromycin selection vector using Mirus Bio TransIT-LT1 Transfection Reagent (Fisher, MIR 2300) in each well of a 6-well plate. Cells positive for the PX459 vector were selected in TeSR-E8 with 0.5 μg/ml of puromycin (ThermoFisher scientific, A1113803) at 48 h after transfection. Puromycin selected cells were cultured in TeSR-E8 for 7-10 days allowing colonies to form. Well-defined colonies (24) were manually passaged onto two Matrigel coated 24-well plates. Once cells reached the desired confluency, we extracted genomic DNA (gDNA) from one 24-well plate and PCR-amplified the genomic regions that flank the sgRNA site for sequence confirmation by Sanger sequencing. To ensure the purity of each clonal colony, we performed single-cell cloning for two gene edited clones. Briefly, each clone was dissociated into single cells, and then single cells were picked into each well of a Laminin-521 (StemCell Technologies, 77003) coated 96-well plate using a stripper micropipetter (Cooper Surgical). Cells were cultured in TeSR-E8 medium containing CloneR (StemCell Technologies, 05888) for 3 days and then cultured in TeSR-E8 for 7-10 days until colonies formed. Colonies were passaged with 1 mM EDTA to Matrigel coated 24-well plates, expanded and cryopreserved. We validated three homozygous mutations using a CRISPR next generation sequencing (NGS) platform (MGH CCIB DNA Core; Massachusetts General Hospital).

To make heterozygous mutations, we used the sgRNA sequence 5’-CCTCCTCACATTCCATGAAC-3’, targeting exon 2. The PX458 vector was transfected into H9 hESCs plated at 20~30% confluency using Mirus TransIT-LT1 (Mirus Bio). We used fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) to select cells positive for the pX458 vector at 48 hours after transfection and sorted single cells into each well of a 96-well plate. To promote single cell survival, we added CloneR and rock inhibitor to TeSR-E8 medium for 24 h after sorting. After 10 days of culture, we picked clones with well-defined stem cell morphology and passaged them to two 24-well plates for gDNA extraction, sequence confirmation, and clonal expansion. We validated the heterozygous mutation using the CRISPR NGS platform (MGH CCIB DNA Core).

Primers for confirmation of the heterozygous mutations are 5’-TCAGAAGAGCTTTTGTTACCTGTG-3’ (forward) and 5’-CCAAGGAGGTAGGTTACCAATG-3’ (reverse). A second primer set (5’-GCCTAGTACCTGGTGCCTCA-3’ and 5’-GGCCTCTCAGTTGTTCACTTC-3’) was used to confirm the homozygous mutations. Serial Cloner software and ICE CRISPR analysis tool from Synthego Inc. were used to analyze indel efficiency and patterns.

2.3. Differentiation of hESCs to excitatory cortical neurons

We modified a previously published protocol for differentiating hESCs to excitatory cortical neurons33. At day −1, hESCs at 80% confluency were dissociated to single cells with accutase. Viable cells (1.8×106) were plated onto one well of a Matrigel-coated 12-well plate containing TeSR-E8 with 10 μM Y27632. The next day (day 0) a monolayer of cells formed and was cultured with neural induction medium which contained neural maintenance media (3N) supplemented with 1 μM Dorsomorphin (Tocris Biosciences) and 10 μM SB431542 (Tocris Biosciences). 3N media contains a 1:1 mixture of DMEM/F12 (Fisher, 11330-032) and Neurobasal medium (Fisher, 21103-049) with 1×N2 (Fisher, 17502-048), 1×B27 (without Vitamin A) (Fisher, 12587010), 1×MEM non-essential amino acids (NEAA; Fisher, 11140-050), 1×GlutaMAX (Fisher, 35050-061), 50 U/ml Penicillin/Streptomycin (P/S; Fisher, 15140-122), 5 μg/ml insulin (Sigma, I9278) and 1×β-mercaptoethanol (BME; Fisher, 21985023). Cells were maintained in neural induction medium with daily medium changes for 10-12 days to form primitive neuroepithelium. At day 12, neuroepithelium was dissociated to clumps with 2 U/ml Dispase (ThermoFisher) for 5 min at 37 °C, and re-plated on Matrigel-coated 6-well plates in 3N media. When the neural epithelium formed rosettes, 3N medium was supplemented with 20 ng/ml fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF2; Peprotech) for 4 days for the expansion of NSCs. At ~day 19, rosettes were either dissociated to single cells using accutase to isolate NSCs, or were dissociated to small rosettes with Dispase and re-plated on Matrigel-coated 6-well plates to continue neuronal differentiation.

Rosettes were cultured in 3N medium with medium changes every other day for 7 days. At day 26, rosettes were dissociated to single cells with accutase, re-plated to Matrigel coated 6-well plates, and maintained in 3N medium (with vitamin A) for 7 days to form neurons. At day 33, young neurons were dissociated with accutase again and re-plated to polyethylenimine-laminin coated 6-well plates at a density of 5×104 cells/cm2. Medium was replaced every other day and was supplemented with 0.4 mM dbcAMP (Sigma, D0627-1) and 200 nM γ-Secretase Inhibitor XXI (Compound E; EMD Millipore) for the first 7 days to inhibit cell division and promote neuronal maturation. At day 48, neurons were cultured in BrainPhys neuronal medium (STEMCELL Technologies, 05790) supplemented with 20 μg/ml GDNF (PeproTech, 450-10), 20 μg/ml BDNF (PeproTech, 450-02), and 0.2 mM ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, A4544). Media was changed every other day from day 34. We transfected some neurons with CaMKIIα-GFP lentivirus34 at day 51-53 to label cortical excitatory neurons. For other experiments, NSCs isolated from neural rosettes at day 19 were plated at a density of 5×104 cells/cm2 and cultured with 3N medium supplemented with 20 ng/mL FGF2 with daily media changes. NSCs were passaged using 100% accutase every 2-3 days. Then NSCs were maintained in 3N medium supplemented with 20ng/ml FGF2 and 20 ng/ml EGF and were passaged using 25% accutase. After 3-4 passages, NSCs were differentiated to neurons by withdrawing both growth factors from the 3N medium.

2.4. RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated with miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized with the SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix kit (Thermofisher). RT-qPCR was carried out with Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermofisher, 4367659) using primers listed in Supplementary Table 1. Fold changes/fold enrichment were calculated using the 2^−ΔΔCt method: ΔΔCt = [(Ct gene of interest - Ct internal control) KO - (Ct gene of interest - Ct internal control) WT], with GAPDH being an internal control.

2.5. Immunoblotting

All tissues were lysed in ice-cold whole cell lysis buffer supplemented with 1×protease and phosphatase inhibitors. The whole cell lysis buffer contained 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 140 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5% NP-40 and 0.25% Triton X-100. The concentration of protein in the lysate was determined using BCA Protein Assay Reagent. Protein (50 μg) was separated on 4-12% gradient Bis-Tris gels (ThermoFisher, NW04125BOX), and transferred onto 0.45-μm polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Thermofisher, LC2005). The membranes were blocked in 1×PBS with 5% non-fat dry milk, incubated with primary antibodies (Supplementary Table 2) at 4 °C overnight, washed three times with 1×TBS, then incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (CST) for 2 h at room temperature (RT). Signal was detected using Clarity™ and Clarity Max™ Western ECL Blotting Substrates (Bio-Rad) and captured using a ChemiDoc™ Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

2.6. Immunocytochemistry and microscopy

hESCs, neural rosettes, NSCs or neurons grown on Nunc Lab-Tek III 8-well chamber slides (Thermo Scientific) were fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min at RT. After permeabilization with 0.2% Triton-X 100 for 20 min at RT, cells were incubated with blocking buffer (5% normal goat serum, 1% BSA, and 0.05% Tween-20 in 1×PBS) for one hour at RT before incubation with primary antibodies at 4°C. After overnight incubation, cells were washed three times with washing buffer (0.05% Tween-20 in 1×PBS), and then incubated with secondary antibodies in the same blocking buffer for 1-2 h at RT. Cells were washed twice with the washing buffer and incubated with bisbenzimide (BB) in 1×PBS for 5 min. After two washes with washing buffer and once with 1×PBS, slides were mounted with Prolong Gold anti-fade reagent (ThermoFisher, P36934). Antibodies used in this study were obtained commercially (see Supplementary Table 2). Images were acquired using a Leica SP5 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc) or an EVOS FL Auto Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). IncuCyte Live Cell Analysis System (IncuCyte S3 2018C, Essen Bioscience) was used for acquiring the time lapse of rosette formation.

2.7. Image quantification

Confocal images acquired using a Leica SP5 confocal microscope were analyzed using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). The individual who performed the analyses was blinded to genotype. In Fig. 3, we outlined rosettes based on the bisbenzimide DNA staining and used this as a region of interest (ROI). The mean intensity of MKI67 was measured for each ROI. These values were then normalized to the BB signal to obtain relative fluorescence levels for MKI67; a similar method was used for quantification of TBR2 and TBR1 intensity inside rosettes. For counting the number of PHH3+ cells inside rosettes, we counted the number of cells in each ROI and then normalized by the area of each ROI. For counting TBR2+ and TBR1+ cells outside rosettes, we outlined each nucleus and the percentages of bisbenzimide-stained nuclei that co-expressed TBR2 or TBR1 were measured. In Fig. 4, we generated a binary mask from the bisbenzimide staining, outlined each nucleus, and used them as ROIs. The percentage of nuclei that co-expressed PAX6 was measured. We manually counted PHH3+ cells and then normalized by the number of ROIs outlined by the bisbenzimide DNA staining. For TUBB3 quantification, we converted each TUBB3 image to binary mode, traced TUBB3+ area using ImageJ for use as a ROI, then measured the mean fluorescence intensity of TUBB3 and normalized to number of nuclei. In Fig. 5, for quantification of PAX6 and DCX intensity inside rosettes, we outlined rosettes based on the bisbenzimide DNA staining as a ROI. The mean intensity of PAX6 or DCX was measured for each ROI. These values were then normalized to the bisbenzimide signal to obtain relative fluorescence level for PAX6 or DCX. For comparing TUBB3 area outside of neural rosettes between different cell lines, neural rosette area was first manually outlined based on the bisbenzimide staining and added as a ROI. The ROI outside of rosettes was defined as the area of a given image with TUBB3 immunoreactivity minus the rosette ROI. The ratio of the area outside of neural rosettes over total area was used in each plot to measure the migration distance of TUBB3+ neurons. Quantification of each marker was performed on at least three biological replicates, with analyses of at least three images per replicate.

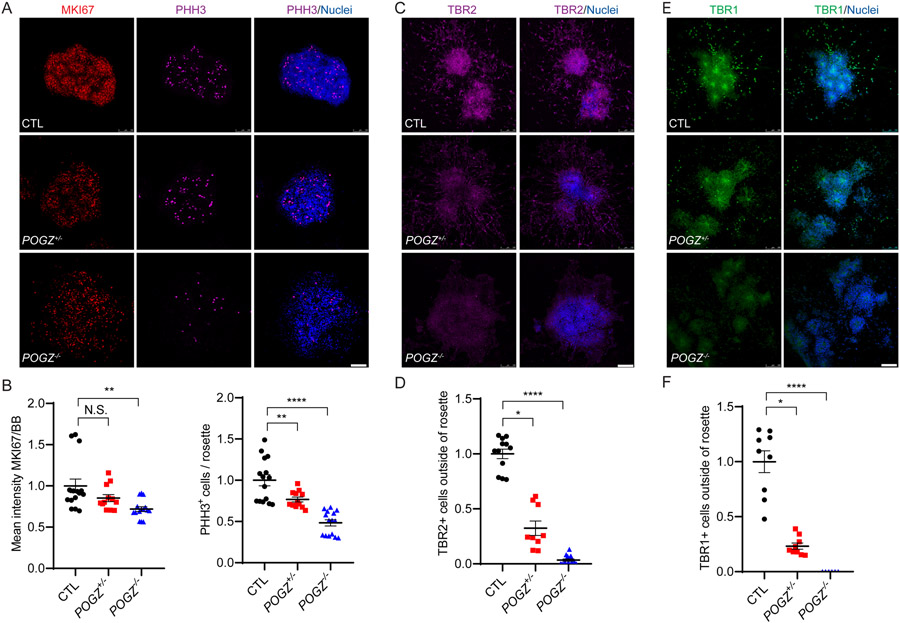

Fig. 3: The loss of POGZ reduces cell proliferation in neural rosettes.

(A) Fluorescence micrographs of neural rosettes from isogenic control (top), heterozygous KO (middle) and homozygous KO (bottom) lines immunostained for phosphorylated histone H3 (PHH3; magenta) and MKI67 (red) at day 21 (3 days after neural rosette picking). Neural rosettes differentiated from control, heterozygous, and homozygous lines have active cell proliferation in neural rosettes that were differentiated from all cell lines, but with decreased proliferation in POGZ−/− lines. BB: nuclear stain (blue). Scale bar: 100 μm. (B) Scatter plots of the fluorescence intensity ratios of MK167:BB (left) and number of PHH3+ cells per rosette (right). MKI67 level was significantly reduced in POGZ−/− lines, and PHH3-positive mitotic cells were reduced in both POGZ−/− and POGZ+/− lines. (C) Fluorescence micrographs of neural rosettes from isogenic control (top), heterozygous KO (middle) and homozygous KO (bottom) lines immunostained for TBR2 (magenta) at day 26 (7 days after neural rosette picking). The POGZ−/− line shows reduced TBR2+ intermediate progenitor cells (magenta). Scale bar represents 100 μm. (D) Scatter plots of the number of TBR2+ cells outside of neural rosettes. The number of TBR2+ cells in either homozygous or heterozygous KO lines is significantly lower than in controls. (E) Fluorescence micrographs of neural rosettes immunostained with TBR1 (green) at day 26. The POGZ−/− line shows reduced TBR1+ early born neurons (green). (F) Scatter plots of number of TBR1+ cells outside of neural rosettes. The number of TBR1+ cells in either homozygous or heterozygous KO lines is significantly lower than in controls. Scale bar represents 100 μm. Images of KI67, PHH3, and TBR2 were acquired from two isogenic control lines, one heterozygous line, and three homozygous lines. Images of TBR1 were acquired from one isogenic control (CTL1), one heterozygous, and one homozygous (POGZ−/− −2) line. At least two biological replicates were carried out for each marker and line. The control line was shown as 1 in all graphs, and POGZ+/− and POGZ−/− were normalized to the control line. Error bars represent SEM. N.S.: P > 0.05; *: P < 0.05; ***: P < 0.001; ****: P < 0.0001.

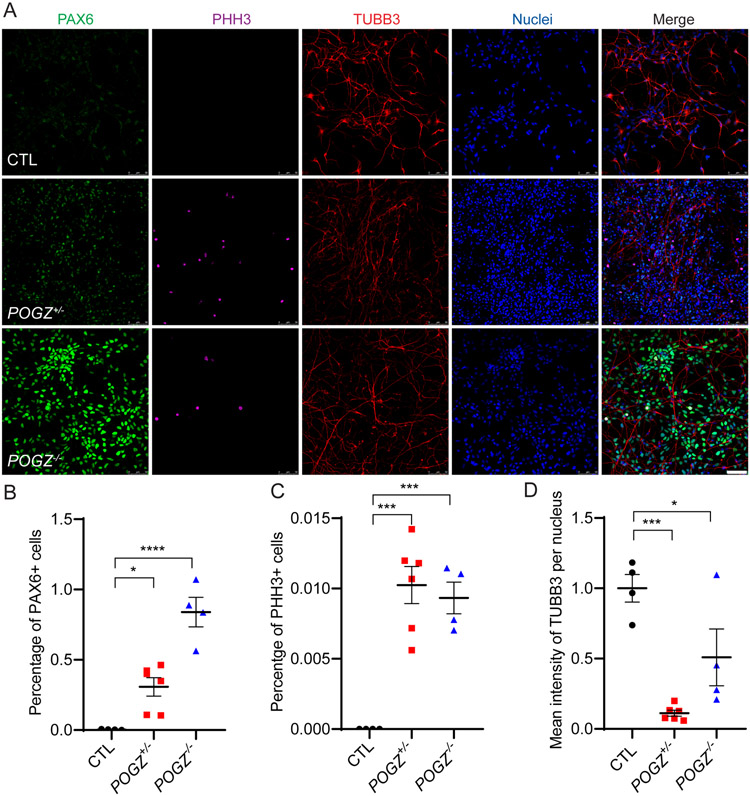

Fig. 4: Loss of POGZ disrupts cell cycle exit of NSCs during neural differentiation.

(A) Micrographs of NSCs differentiated for 14 days from isogenic control (top), heterozygous (middle), and homozygous (bottom) POGZ KO lines immunostained for PAX6 (green), PHH3 (magenta) or TUBB3 (red). POGZ−/− and POGZ+/− neurons maintained PAX6 expression levels while control neurons have the expected decrease in PAX6 expression as they differentiate. In addition, PHH3-positive mitotic cells were present in POGZ+/− and POGZ−/− neurons, but not in control neurons. (B-C) Scatter plot of percentages of PAX6+ or PHH3+ cells at day14. There were significantly more PAX6+ and PHH3+ cells in both heterozygous and homozygous KO neurons than in control neurons at day 14. One-way ANOVA test with adjusted p-values calculated by Brown-Forsythe test. (D) Scatter plot of mean intensity of TUBB3 immunoreactivity per cell. Mean intensity of TUBB3 in either homozygous or heterozygous KO lines was significantly lower than in the control line. Scale bar: 50 μm. The control line was designated as 1 in (D), and the POGZ+/− and POGZ−/− lines were normalized to control. Images were acquired from one isogenic control (CTL1), one heterozygous, and one homozygous (POGZ−/− −2) line. Data were pooled from two biological replicates. Error bars: SEM. N.S.: P > 0.05; *: P < 0.05; ***: P < 0.001; ****: P < 0.0001.

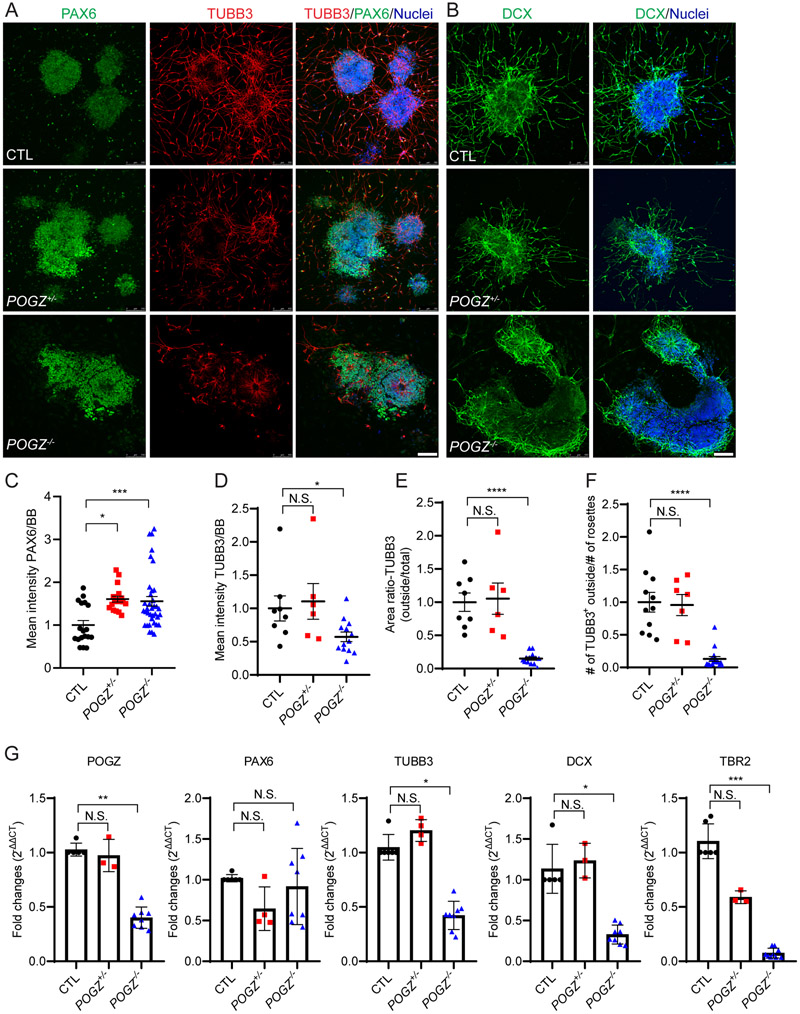

Fig. 5: The loss of POGZ decreases neuronal migration in differentiating neural rosettes.

(A-B) Fluorescence micrographs of neural rosettes from isogenic control (top), POGZ+/− (middle) and POGZ−/− (bottom) lines at day 24 (5 days after neural rosette picking) immunostained for TUBB3 (A, red) and PAX6 (A, green), or for Doublecortin (DCX; B, green). BB: nuclear stain (blue). Neurons in control and POGZ+/− rosettes extended out of the neural rosettes. In contrast, most POGZ−/− neurons are still present either inside or close to rosettes. Scale bar represents 50 μm. (C) Scatter plot of mean intensity of PAX6 normalized to BB nuclear staining. The mean intensity of PAX6 in both homozygous and heterozygous KO lines is significantly greater than in isogenic control lines. (D) Scatter plot of mean intensity of TUBB3 normalized by BB nuclear staining. The intensity of TUBB3 in homozygous lines, but not in the heterozygous KO line, is significantly lower than in isogenic control lines. Both the TUBB3 distribution area ratio (outside rosette: total area) (E) and the number of TUBB3+ cells outside of rosettes (F) are significantly lower in the homozygous condition than in control or heterozygous condition. Data were acquired from two isogenic control lines, one heterozygous line, and three homozygous lines. (G) Bar graphs of the mRNA expression levels of selected genes. In neural rosettes, mRNA expression levels of TUBB3, DCX, and TBR2 are significantly lower in POGZ−/− neural rosettes than in control rosettes. There are no significant changes of PAX6 mRNA levels between mutants and controls. Rosette samples were collected at 3~6 days after rosette picking (day 21~25). Fold changes were calculated using 2−ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH as an internal control. RT-qPCRs were acquired from two isogenic control lines, one heterozygous line, and three homozygous lines. Each line was repeated at least two times. Control line was shown as 1 in all graphs, and then POGZ+/− and POGZ−/− normalized to control lines. Error bars are SEM. N.S.: P > 0.05; *: P < 0.05; ***: P < 0.001; ****: P < 0.0001.

2.8. Sholl analysis

Phase images were obtained with an EVOS FL Auto Imaging System. All the images were processed using ImageJ/Fiji or Adobe Photoshop CS3 software. Images of isolated neurons that were transfected with CaMKIIα-GFP lentivirus were chosen for illustration, and two-dimensional reconstructions were made to trace dendritic or axonal arbors for measurement of neurite length. Simple neurite tracer in ImageJ/Fiji software was used to generate tracings (i.e. paths) to measure neurite length and perform Sholl analysis. Neurite complexity was quantified with Sholl analysis by counting the number of neurite intersections of concentric circles of gradually increased radius centered at the cell body with ImageJ/Fiji35,36. For each neuron, we measured intersections at every 10 μm radius from the soma (defined as one distance point), up to 500 μm radius, therefore there were 50 distance points. Mean intersections per neuron (Fig. 6C) is defined as the number of all intersections of a given neuron normalized by number of distance points (50) in the measurement. Total length (Fig. 6D) is the total length of neurites in all paths traced by ImageJ FiJi for a given neuron. Mean length (Fig. 6E) is the average length of neurites in a given neuron (i.e. total length of neurites in all paths normalized by number of paths in a given neuron). Image acquisition and data analysis were performed in a blinded manner. At least three biological replicates were used for the current study.

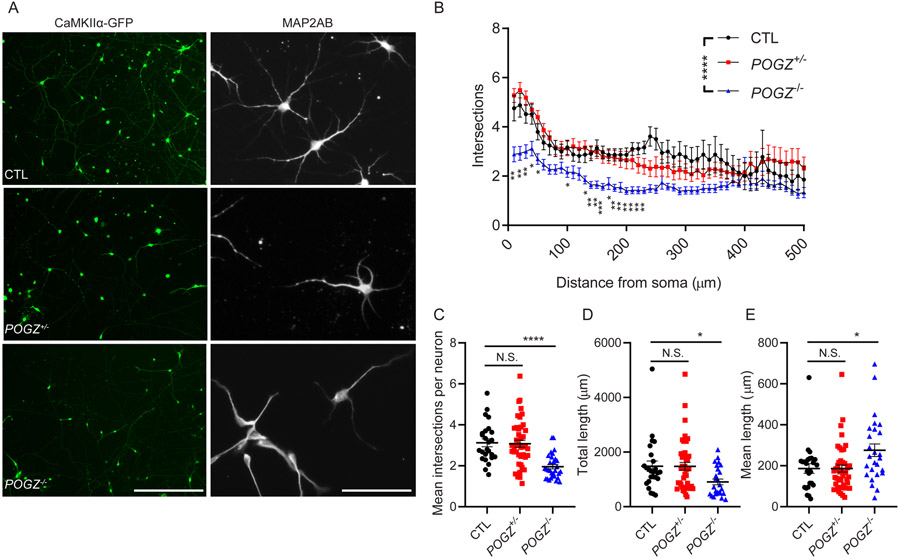

Fig. 6: Cortical-like excitatory neurons derived from POGZ knockout stem cells display simplified dendritic architecture.

(A) Micrographs of cortical-like excitatory neurons that were differentiated to day 58~60 from control, POGZ+/− and POGZ−/− lines. Left: neurons were labelled with lentivirus containing a CaMKIIα-driven GFP reporter of excitatory cortical neurons at day 51 and then imaged at day 58. These images were used for the Sholl analysis in B. Scale bar represents 400 μm. Right: Day 58 neurons were immunostained with an antibody against a mature neuron marker, MAP2ab. Note decreased dendritic complexity in POGZ−/− neurons. Scale bar represents 100 μm. (B) Line plots of the quantification of dendritic complexity using Sholl analysis. y-axis is total intersections; x-axis is distance from the soma. (C) Scatter plots of the mean intersections per neuron within a 500 μm radius from the soma. CTL, 3.126 ± 0.192; POGZ+/− (one line), 3.077 ± 0.175; POGZ−/−, 1.957 ± 0.108. P < 0.0001 by ANOVA, with post hoc Dunnett’s test showing P = 0.9683 for POGZ+/− vs CTL, P < 0.0001 for POGZ−/− vs CTL. (D) Scatter plots of the total dendritic length of all neurons. For total dendritic length: CTL, 1484 ± 190.2 μm; POGZ+/− (one line), 1480 ± 142.8 μm; POGZ−/−, 908.3 ± 105 μm. For ANOVA, P = 0.0167. For post hoc Dunnett’s test, P = 0.9998 for POGZ+/− vs CTL, P = 0.0323 for POGZ−/− vs CTL. (E) Scatter plots of mean dendritic length per neuron. CTL, 186.6 ± 23.34 μm; POGZ+/−, 186.3 ± 17.44 μm; POGZ−/−, 275.7 ± 30.85 μm. A minimum of 25 neurons were analyzed for each genotype. Images were acquired from one isogenic control (CTL1), one heterozygous, and one homozygous (POGZ−/− −2) line. For ANOVA with post hoc Dunnett’s test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Error bar represents SEM.

2.9. Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., LaJolla, California, USA). Prism was used for generating all the statistical graphs displayed. We first performed a normality test for each dataset. Analyses of RT-qPCR and immunoblotting results were performed using a Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparisons post hoc test. Fluorescent intensity of PHH3, MKI67, TBR2, TBR1, TUBB3, and PAX6 were analyzed using non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparisons test unless specified otherwise in the figure legends. For Sholl analysis, the statistical comparisons were made with one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparisons test. Graphs are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A confidence interval of 95% (P < 0.05) was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Generation of POGZ LoF models of human cortical development

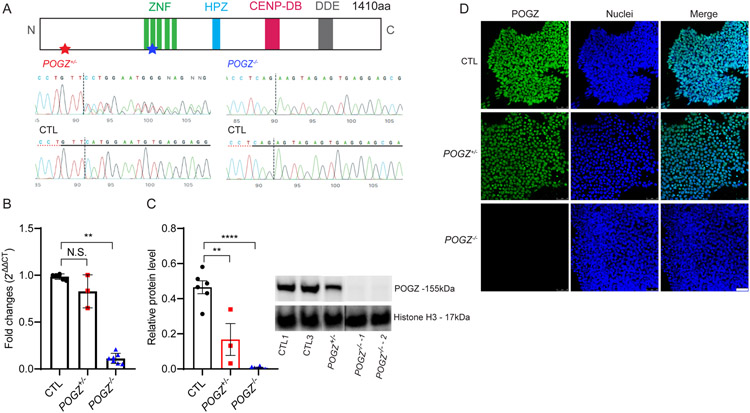

We generated multiple homozygous and one heterozygous POGZ LoF hESC lines using CRISPR/CAS9 genome editing. The majority of de novo POGZ variants identified in patients with NDDs are nonsense and/or frameshift mutations, likely leading to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) that results in loss of the POGZ protein6,14. However, few rodent or human stem cell POGZ LoF models are available to interrogate its function in brain development. First, we examined the isoform expression of POGZ in the human brain (https://www.gtexportal.org/home/). There are twenty-one different isoforms annotated in the human genome to date, and eight of them are expressed at a substantial level in the human brain (Supplementary Fig. 1). To achieve the maximum knockout efficiency of the POGZ protein, we designed t three sgRNAs targeting two exonic regions (using transcript ENST00000271715.6/RefSeq NM_015100), which are common to all major protein coding isoforms (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1). We obtained multiple CRISPR edited lines and isogenic control lines. One heterozygous knockout line (POGZ+/−) that contains a one base pair insertion in exon 2, three homozygous POGZ knockout (POGZ−/−) lines, each of which carried a one base pair insertion in exon 12, and two isogenic control lines were used in the current study (Fig. 1A). Indel patterns and predicted frameshift outcomes are listed in Supplemental Table 3. All the edited and control lines maintained pluripotency (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Fig. 1: Confirmation of POGZ knockout hESC lines.

(A) Top: A schematic diagram of the POGZ protein. ZNF: zinc finger DNA binding domain; HPZ: HP1α binding zinc finger-like domain; CENP-DB: centromere protein-B-like DNA-binding domain; DDE: domain originated from a transposase encoded by a pogo like DNA transposon. Bottom: Chromatograms from the sequencing of POGZ mutants. Heterozygous mutation (POGZ+/−, left) is located at the beginning of the N-terminus (red star at the top), and homozygous mutation (POGZ−/− −1 & −2, right) is located in the C2H2 Zn domain (blue star at the top). Dashed lines represent Cas9 cleavage site. (B) Bar graphs of POGZ RT-qPCR in control (CTL) and POGZ knockout lines. Fold changes were calculated using 2−ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH as an internal control. RT-qPCR confirms significant loss of POGZ mRNA expression in POGZ−/− lines, while the difference between POGZ+/− and control lines is not significant. (C) Immunoblots of control and knockout lines. Whole cell lysates were blotted against anti-POGZ (residue 1-100aa) and anti-Histone H3 antibodies. Histone H3 served as a loading control. Equal amounts of protein lysates were used. Relative protein level was calculated as POGZ protein level/Histone H3 level. POGZ protein was absent in POGZ−/− lines and it was significantly reduced in the POGZ+/− line. (D) Fluorescence micrographs of immunostained cells from isogenic control and mutant lines. POGZ (green) was detected with an antibody against its N-terminus residues. Immunostaining confirms the absence of nuclear POGZ localization in POGZ−/− cells and reduced expression of POGZ in the POGZ+/− cells. bisbenzimide (BB): nuclei (blue); CTL: control line; POGZ+/−: heterozygous line; POGZ−/−: homozygous line. Scale bar: 50 μm. Data were collected from two isogenic control lines, one heterozygous line, and three homozygous lines. Representative results from three or more biological replicates are shown. Error Bar is SEM. N.S.: not significant. **: P < 0.01; ***: P < 0.001; ****: P < 0.0001.

We used RT-qPCR and immunoblotting to determine mRNA and protein levels of POGZ, respectively. A single base pair insertion in exon 12 resulted in a frameshift and introduction of an early stop codon, leading to a decrease in POGZ mRNA levels by ~90% in POGZ−/− lines. However, a single base pair insertion in exon 2 in the POGZ+/− line caused only a minimal, non-significant reduction of mRNA transcript levels (Fig. 1B, Supplementary Fig. 3a). Immunoblotting cell lysate from all cell lines with anti-POGZ antibody showed that almost no POGZ protein was present in POGZ−/− lines. In comparison, the protein level was reduced by more than 50% in the POGZ+/− line (Fig. 1C, and Supplementary Fig. 3b). The reduction of nuclear POGZ protein in mutant lines was also readily apparent by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 1D). Although potential NMD caused by these frameshift mutations was not tested in the current study, our CRISPR knockout lines showed complete loss (POGZ−/− line) or partial loss ( POGZ+/− line) of the POGZ protein, providing valid stem cell models of POGZ LoF.

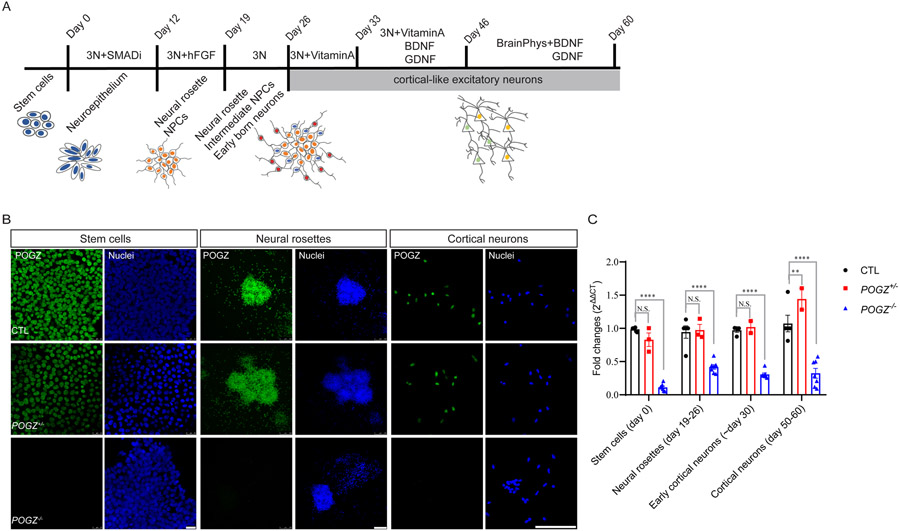

To examine the function of POGZ during early human neurodevelopment, we differentiated mutant and control hESC lines to neural structures that model early fetal human brain development, including neural rosettes and cortical-like excitatory neurons (schematic shown in Fig. 2A)33. Briefly, we first applied small molecules to hESC monolayers to induce formation of a neuroepithelial sheet. A definitive neuroectoderm develops and organizes into neural rosette-like structures, similar to the forebrain ventricular zone (VZ)/subventricular zone (SVZ) in vivo, containing proliferating cortical stem and intermediate progenitor cells (collectively termed NSCs here). Following rosette selection, cortical development of the monolayer cultures is coupled with sequential expression of markers for the appropriate cortical laminar projection neurons, with the deep layer, early-generated neurons migrating out from the apical to the basal surface of cortical rosettes, and upper layer neurons generated later. In the developing human brain, POGZ is expressed at a constant level from early to late fetal stages (https://portal.brain-map.org/). We observed a similar pattern of POGZ protein and transcript expression throughout the differentiation process in isogenic control lines (Fig. 2B). POGZ transcripts remained at significantly low levels and protein levels were absent at all stages in the POGZ−/− lines, although the POGZ+/− line transcript levels were not significantly different than the control levels (Fig. 2C, Supplementary Fig. 4).

Fig. 2: In vitro neural differentiation of POGZ heterozygous KO, homozygous KO, and isogenic control lines.

(A) A schematic of the directed neural differentiation following dual SMAD inhibition. In brief, stem cells self-organize into neuroepithelial sheets followed by twelve days of inhibition of the dual SMAD pathway. At day 12, neuroepithelial sheets were then dissociated into smaller pieces and cultured with fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF2). Upon removal of FGF2 at day 19, neural rosettes were dissociated again to smaller clumps and continue to differentiate into more complex neural structures where intermediate neural progenitor cells and early born neurons reside (blue and red, respectively). At day 26, neural rosettes were dissociated and further differentiated into neurons. (B) Fluorescence micrographs of cells from KO and isogenic control lines immunostained for POGZ show POGZ (green) protein expression at different differentiation stages (stem cells, rosettes and neurons). BB: bisbenzimide nuclear stain (blue). Scale bar of stem cell panel is 50 μm; neural rosette panel is 100 μm; cortical neuron panel is 100 μm. (C) Bar graphs of POGZ RT-qPCR of KO and control lines at different stages. Fold changes were calculated using 2−ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH as an internal control. RT-qPCR confirms significant loss of POGZ mRNA expression in POGZ−/− lines, while the difference between POGZ+/− and control lines is not significant. Error Bar is SEM. N.S.: not significant. **: P < 0.01; ***: P < 0.001; ****: P < 0.0001.

3.2. POGZ regulates NSC proliferation and lineage progression in human cortical rosettes

During early stages of neural rosette formation, the NSC population expands through active cell proliferation. Phosphorylated histone H3 serves as a critical signal to recruit protein complexes to the mitotic chromatin for cells to complete mitosis. To examine the role of POGZ in mitosis and NSC proliferation at the neural rosette stage, we immunostained day 21 neural rosettes for markers of mitosis (phosphorylated histone H3; PHH3) or cell proliferation (MKI67). PHH3 and MKI67 levels were significantly reduced in POGZ−/− lines, while only a moderate reduction of PHH3+ cells appeared in the POGZ+/− line (Fig. 3A, B, Supplementary Fig. 5a-b). As neural rosettes continue to develop, PAX6+ NSCs in the VZ give rise to TBR2+ intermediate progenitors in the SVZ and also early born, deep layer TBR1+ neurons. We immunostained day 26 neural rosettes with TBR2 and TBR1, measured the number of TBR2+ or TBR1+ cells in each rosette, and found that rosettes derived from both POGZ+/− and POGZ−/− lines showed reduced numbers of TBR2+ and TBR1+ cells compared to the isogenic control lines (Fig. 3C-F, Supplementary Fig. 5c-d). These findings indicate that POGZ deficiency impairs cell proliferation in early neural rosettes and may alter NSC lineage progression in later neural rosettes.

3.3. The loss of POGZ disrupts the cell cycle exit of NSCs

Proper cell cycle exit plays an important role in controlling cell number and cell fate in the normal context of mammalian cortical development37. To examine if loss of POGZ affects cell cycle exit during NSC lineage progression, we dissociated day 19 neural rosettes from all the lines to single cells, purified NSCs, and then differentiated them into neurons. This monolayer culture system generates more homogenous neuronal cultures and allows for easy quantification of different cell markers after differentiation. The NSCs from all mutant and control lines expressed the NSC marker NESTIN while they completely lost their hESC pluripotency (Supplementary Fig. 6). We plated these NSCs into neural differentiation medium at equivalent densities and analyzed the resulting neurons after 14 days by immunostaining for the NSC marker PAX6, mitotic marker PHH3, and immature neuron marker βIII-tubulin (TUBB3). NSCs from the control line exited cell cycle and became post mitotic neurons, as demonstrated by nearly no immunoreactivity for PAX6 and PHH3, and substantial TUBB3 immunostaining (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the number of PAX6+ and PHH3+ neurons in POGZ−/− lines were significantly higher than in the control line (Fig. 4B, C), while the mean intensity of TUBB3 per cell was significantly reduced (Fig. 4D). Since quantification of TUBB3 was difficult due to greater process clumping of POGZ−/− neurons than wild type neurons, we performed immunoblotting at a similar stage (day 21-26 rosettes), and found that TUBB3 levels in POGZ−/− lines were significantly lower than the levels in the control lines (Supplementary Fig. 7a). The POGZ+/− line showed intermediate but significantly increased levels of PAX6 and PHH3 (Fig. 4B,C); however, TUBB3 levels were not consistent between immunostaining and immunoblotting (Fig. 4D, Supplementary Fig. 7a). These data suggest that POGZ is critical for NSCs to exit the proliferative cell cycle and differentiate into post-mitotic neurons.

3.4. Loss of POGZ delays neuronal migration

We next tracked the differentiation process from the NSC stage to the late neural rosette stage using live-cell imaging. Neural rosettes formed normally in all mutant lines and exhibited similar morphologies within the first few days (day 15-20) of rosette formation (Supplementary Fig. 8). Shortly after rosette formation (day 21 onwards), fewer neurons appeared outside of POGZ−/− neural rosettes, although process outgrowth was evident at day 21, while many neurons extended away from the rosettes derived from isogenic control and POGZ+/− lines (Supplementary Fig. 9b, Supplementary video 1). The rosette size was similar between CTL and POGZ−/− lines; however, POGZ+/− rosettes were slightly bigger than CTL rosettes (Supplementary Fig. 10a). Immunostaining of day 24 rosettes for the immature neuronal marker TUBB3 confirmed the impaired migration of POGZ−/− neurons (Fig. 5A). First, cell proliferation as suggested by PAX6 immunostaining was significantly higher in both heterozygous and homozygous lines than in control lines (Fig. 5C, Supplementary Fig. 10b). Second, not only was the mean intensity of TUBB3 lower in POGZ−/− than in control neurons (Fig. 5D, Supplementary Fig. 10c), but also the number of TUBB3+ neurons outside of POGZ−/− rosettes were significantly lower than that seen in both control and heterozygous rosettes (Fig. 5E, F, Supplementary Fig. 10d,e). Lastly, immunostaining of day 24 rosettes for the young neuronal marker doublecortin (DCX) further confirmed that the loss of POGZ influences the apical-basal migration of neurons within and then outside of the neural rosettes (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Fig. 10f). Moreover, the transcript levels of TBR2, TUBB3 and DCX were significantly lower in POGZ−/− rosettes than in control rosettes (Fig. 5D, Supplementary Fig. 10f). Together with our findings above, these data suggest that POGZ regulates the differentiation and migration of human cortical-like neurons.

3.5. The loss of POGZ affects neurite outgrowth and dendritic complexity

To assess the impact of POGZ loss on neuronal maturation, we examined neurite outgrowth of cortical-like excitatory neurons generated from control, POGZ+/− and POGZ−/− neurons. Measuring neurite outgrowth is one of the most common phenotypic assays to study neuronal maturation in vitro38. We dissociated day 26 neural rosette/neuron mixed cultures to single cells, plated them onto PEI-Laminin-coated dishes, and cultured them in medium containing neurotrophic factors to promote neuronal maturation. We then labeled cortical neurons with lentiviral particles containing a CaMKIIα-driven GFP reporter construct at day 51 to visualize the processes of excitatory neurons, and then imaged them at day 58 for Sholl analyses (Fig. 6A, B). Neuronal phenotype was confirmed by expression of the mature neuronal marker MAP2AB (Fig. 6B). We found that neurons from all the lines expressed VGLUT1, but VGLUT1 mRNA transcript levels were significantly reduced in POGZ−/− neurons compared to control lines (Supplementary Fig. 11). We then used Sholl analysis to measure the number of dendritic intersections against the radial distance from the soma center38,39, and measured neurite length by image segmentation. We found that the number of intersections of all neurons at distances between 10 and 250 μm from the cell body of POGZ−/− neurons was significantly lower than in control neurons (Fig. 6B), as was the mean number of total intersections at each measured distance per neuron (Fig. 6C, POGZ−/−, 1.957 ± 0.108; CTL, 3.126 ± 0.192, P < 0.0001). No significant differences were detected between POGZ+/− and control neurons (Fig. 6B, C; 3.077 ± 0.175, P = 0.9683). The combined length of all neurites was significantly reduced in POGZ−/− neurons compared to control lines (Fig. 6D; POGZ−/−, 908.3 ± 105 μm; CTL, 1484 ± 190.2 μm, P = 0.0323), while the mean neurite length of POGZ−/− neurons was longer than the length of control neurons (Fig. 6E; CTL, 186.6 ± 23.34 μm; POGZ−/−, 275.7 ± 30.85 μm, P = 0.0129). For POGZ+/− neurons, neither total nor mean neurite length were significantly different from the length of control neurons (Fig. 6D). These data suggest that loss of POGZ impairs neurite outgrowth and branching during neuronal maturation.

4. Discussion

Most de novo LoF POGZ mutations identified in patients with NDDs are either nonsense or frameshift mutations6,14 which are thought to lead to LoF of the POGZ protein6,14. Surprisingly, this hypothesis has not been experimentally tested for most POGZ disease variants in human-based models. Adding to the ambiguity is that iPSC or rodent models of LoF variants are not widely available yet. One recent study reported that human iPSC models were generated from a patient and a healthy individual, but this missense variant showed only a subtle differentiation and migration phenotype14. We developed the first CRISPR hESC models of POGZ frameshift mutations that lead to complete or partial loss of the POGZ protein, including both heterozygous and homozygous mutants with isogenic controls. Using CRISPR/CAS9 genome editing to generate POGZ LoF lines in the same genetic background circumvents difficulties in obtaining multiple patient tissues for iPSC reprogramming and allows for comparison with an isogenic control. Taking advantage of highly efficient in vitro neural differentiation approaches33, we have established powerful tools for modeling the impact of the loss of POGZ on human cortical development.

We found that POGZ is an important regulator of NSC proliferation and lineage progression during the development of cortical rosettes. Previous work showed that loss of POGZ failed to release the HP1α binding protein from heterochromatin during G2-M transition and disrupted cell cycle progression2,17. During mitosis, phosphorylated histone H3 levels serve as a critical signal to recruit protein complexes to the mitotic chromatin for cells to complete G2-M transition and mitosis40. Our findings of decreased phosphorylated histone and MKI67 levels in early stage POGZ−/− cortical rosettes (day 21) suggest that the loss of POGZ disrupts G2-M transition in NSCs of early neural rosettes, possibly leading to decreased NSC proliferation and subsequent reduced neurogenesis. Consistent with this idea, we observed decreased mRNA and protein levels of the intermediate progenitor marker TBR2 and deep layer cortical neuron maker TBR1 in day 24-26 neural rosettes. When we differentiated homogeneous NSC populations to neurons, large number of neurons with complete or partial loss of POGZ maintained high expression levels of the NSC marker PAX6 and/or the mitotic maker phosphorylated histone H3, indicating that the neurons failed to properly exit the cell cycle. Taken together, the reduction of NSC proliferation in early cortical rosettes and the subsequent disrupted cell cycle exit in differentiated neurons resulted in decreased neurogenesis.

These results suggest a possible cellular mechanism underlying the microcephaly feature seen in individuals with POGZ LoF variants6,8. Our findings are also in line with overall microcephaly phenotypes from two different mouse POGZ models, but likely through different cellular mechanisms14,17. Notably, our NSC proliferation phenotype is different from the one found in a patient iPSC line carrying a missense mutation, which showed increased proliferation and neurosphere size14. One possibility for this discrepancy is that the missense heterozygous mutation caused a gain of function or dominant-negative effect. Varying severity of phenotypes from cell lines or rodent models with different genomic contexts have previously been reported24,41. This discrepancy is consistent with documented interindividual variability42. As many ASD risk gene variants including POGZ variants show variable clinical features in humans17, there may be multiple underlying pathological mechanisms caused by different types of POGZ mutations, with or without varied effects based on the specific background genomic context.

In addition to cell proliferation, we discovered that POGZ is important for neuronal migration and maturation including the dendritic outgrowth and branching of cortical-like excitatory neurons. As reported previously14, many POGZ−/− newly born neurons failed to migrate out of VZ/SVZ-like regions in neural rosettes. With continued neuronal differentiation, we found that POGZ−/− neurons possessed less complex dendrites with reduced branching compared to isogenic wild-type neurons, a phenotype that has not been reported. A previous study found that POGZ is present in synaptic fractions in the adult mouse brain13. This finding suggests that POGZ is important for neuronal maturation and synaptogenesis or synapse maintenance. Future studies are necessary for determining the roles of POGZ in synaptic development or function. We also found that the mRNA transcript levels of several critical neuronal markers were reduced at both the neural rosette and mature neuronal stages, suggesting that POGZ also regulates neuronal differentiation through transcriptional regulation14,17. Future molecular characterization such as transcriptome and regulatory element analyses will be important for further elucidating the molecular mechanisms of POGZ in neuronal differentiation.

One of the limitations of the current study is that we were only able to generate one heterozygous line. This line showed subtle and inconsistent effects on neural differentiation of stem cells, which limit our ability to make conclusions of ASD pathology resulting from POGZ haploinsufficiency. Although heterozygous autism risk gene models show subtle and varying phenotypes24,41, these differences underscore the importance of investigating autism risk genes across multiple cells lines and model systems. Future studies combining the use of patient iPSCs carrying deleterious heterozygous variants in POGZ with CRISPR knockout or variant-corrected cells will be useful to further illuminate the underlying causes of ASD.

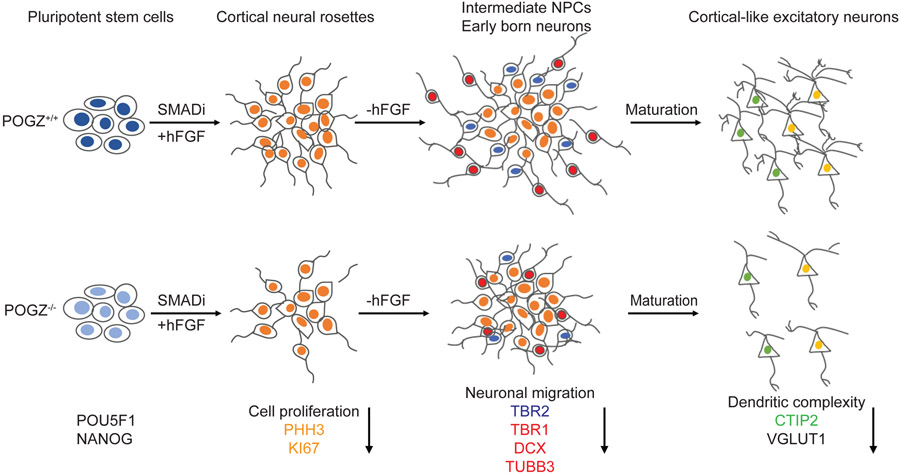

In summary, although POGZ haploinsufficiency has only subtle phenotypes, the complete loss of POGZ leads to robust abnormalities during neural differentiation (Fig. 7). POGZ−/− stem cells are able to differentiate to cortical rosettes that are similar to isogenic controls morphologically, but they exhibit reduced proliferation. While going through differentiation, POGZ−/− NSCs fail to exit the cell cycle, resulting in the generation of fewer neurons. This phenotype is consistent with the microcephalic phenotype in some patients with POGZ LoF variants6,8. During early neurogenesis, many POGZ−/− neurons fail to migrate out of VZ/SVZ-like regions in our model. Furthermore, at later stages of neural differentiation, the loss of POGZ impairs neuronal maturation as shown by reduced dendritic complexity. Collectively, we provide the strongest evidence to date that loss of POGZ impacts multiple stages of early human cortical development.

Fig. 7: POGZ regulates neural progenitor cell proliferation, migration, neuronal differentiation, and dendritic complexity.

(Top) Schematic of normal neurodevelopment. Pluripotent stem cells are differentiated to cortical rosettes containing proliferating cortical stem and then intermediate neural progenitor cells (NPCs) using a combination of dual SMAD inhibition and FGF2 treatments. Upon the removal of FGF2, neural stem cells then follow a similar developmental progression in the genesis of cortical projection neurons that occurs in vivo, with deep layer neurons generated early, and migrating out to the basal surface and outside of cortical rosettes, and upper layer neurons generated later. Cortical projections neurons of all layers eventually form networks of functional excitatory, glutamatergic synaptic connections through their complex dendritic structures. (Bottom) Schematic of abnormal neurodevelopment due to loss of POGZ. Pluripotent stem cells that lack POGZ are able to differentiate to cortical rosettes similar to the wildtype cells, but with reduced cell proliferation that results in less intermediate progenitor cells. In addition, POGZ−/− neural stem cells fail to exit cell cycle while going through differentiation, which results in reduced numbers of cortical neurons. During early neurogenesis when neurons are born, many POGZ−/− neurons fail to migrate out of VZ/SVZ-like regions. Furthermore, at the later stages of differentiation, the loss of POGZ also affects the dendritic structure as cortical neurons mature and form synapses.

5. Conclusion

The goal of this study was to uncover the consequences of POGZ deficiency in a cell culture model of cortical development. We generated the first POGZ LoF human stem cell models using CRISPR/CAS9 genome editing and successfully modeled how the loss of POGZ influences the developmental trajectory of corticogenesis in vitro. We found that the loss of POGZ mis-regulates NSC proliferation and differentiation, delays neurogenesis, and impairs the migration of developing neurons. We also found that the lack of POGZ alters mRNA expression levels of multiple critical neuronal markers during neurogenesis. Furthermore, we discovered simplified dendrites in neurons derived from homozygous POGZ knockout hESCs, a novel phenotype. In conclusion, our results demonstrated the impact of POGZ LoF on human neurodevelopment, shedding light on the pathophysiology of POGZ-associated NDDs.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig. 1: POGZ isoform expression information in GTEx portal. The CRISPR-generated heterozygous mutation (POGZ+/−, red) is located at the beginning of the 5’ end of the POGZ transcript, and the homozygous mutation (POGZ−/−, blue) is located in the middle of the transcript.

Supplementary Fig. 2: Immunolabeling confirmation of pluripotency of stem cells lines used in the current study. POU5F1 (a), SOX2 (b) and NANOG (c) are nuclear proteins (green), and SSEA4 (d) is a cell surface marker (red). CTL: control. Scale bar: 50 μm.

Supplementary Fig. 3: Confirmation of isogenic control (CTL) and POGZ mutant lines by RT-qPCR and immunoblotting (data shown for each clone). (a) Bar graphs of POGZ RT-qPCR in 2 control (CTL), 1 heterozygous, and 3 homozygous POGZ knockout lines. Fold changes were calculated using 2−ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH as an internal control. The PCR primers are located at the 5’end, middle, and 3’ end of POGZ cDNA. (b) Whole cell lysate was blotted against POGZ and actin antibodies, respectively. Nuclear protein lysate was blotted against Anti-histone H3. The 4th homozygous line (POGZ−/− −4) was not used in the current study due to incomplete knockout of the POGZ protein. Anti-actin and anti-histone H3 blots served as loading controls. Equal amounts of protein lysates were used.

Supplementary Fig. 4: Bar graphs of POGZ RT-qPCR of KO and control lines at different stages (data shown for each clone). Bar graphs of POGZ RT-qPCR in 2 control (CTL), 1 heterozygous, and 3 homozygous POGZ knockout lines. Fold changes were calculated using 2−ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH as an internal control.

Supplementary Fig. 5: The loss of POGZ reduces cell proliferation in neural rosettes (data shown for each clone). Scatter plots of the fluorescence intensity ratios of MK167:BB (a) and number of PHH3+ cells per rosette (b). Quantification of TBR2+ cells inside (c) or outside of rosettes (d). 2 control (CTL), 1 heterozygous, and 3 homozygous POGZ knockout lines were used in these analyses. CTL1 was designated as 1 in all graphs, and other clones were normalized to CTL1.

Supplementary Fig. 6: NSCs lose stem cell pluripotency and express the NSC marker Nestin. POU5F1 is a stem cell pluripotency marker (green), NESTIN is a NSC marker (red). BB stains nuclei. Scale bar: 50 μm. 2 control (CTL), 1 heterozygous, and 3 homozygous POGZ knockout lines were used in these analyses. Scale bar: 50 μm.

Supplementary Fig. 7: Whole cell lysates from day 21-26 rosettes were blotted against POGZ, TUBB3, Vinculin, and Actin antibodies. Anti-Actin and anti-Vinculin served as a loading control. Equal amounts of protein lysates were used. 2 controls (CTL1/WA09 and CTL3/PG22-4), 1 heterozygous line (POGZ+/−/PG3), and 3 homozygous POGZ knockout lines (POGZ−/−-1/PG9-3, POGZ−/−-2/PG9-4, POGZ−/−-3/PG22-13) were used in these analyses. Selected immunoblot images from two biological replicates (iN#5 and #7) were shown in the current figure for anti-TUBB3 (a) and anti-POGZ (b). Data were pooled from three biological replicates (iN#5, 7, 10). CTL was designated as 1 in all graphs, and then other clones normalized to CTL.

Supplementary Fig. 8: Time lapse images show the development of neural rosettes. Phase images of neural rosettes (day 15~23) from control (top), heterozygous KO (middle) and homozygous KO (bottom) lines. Phase images of neural rosettes at day 15 were acquired using EVOS imaging system and from days 20~23 using an Incucyte live imaging system. Arrows show migrating neurons. Scale bar: 400 μm.

Supplementary Fig. 9: Neuronal migration in differentiating neural rosettes. Fluorescence micrographs of neural rosettes from control (top), POGZ+/− (middle), and POGZ−/− (bottom) lines at day 15 (a) and day 21 (b) immunostained for TUBB3 (red) and PAX6 (green). BB: nuclear stain (blue). Neuronal migration was less in neural rosettes derived from the POGZ−/− line at day 21 (b). Arrows show migrating neurons. Dotted circles outline neural rosettes. (a) Scale bar: 200 μm. (b) Scale bar: 100 μm.

Supplementary Fig. 10: The loss of POGZ decreases neuronal migration in differentiating neural rosettes (data shown in each clone). (a) Rosette size measured by diameter. (b) Mean intensity of PAX6 normalized by BB. (c) Mean intensity of TUBB3 normalized by BB. (d) TUBB3+ area outside of rosettes vs total area. (e) Average number of TUBB3+ neurons outside of rosettes. (f) DCX+ area outside of rosettes vs total area (CTL1, POGZ+/− and POGZ−/− −2 included in the graph). (g) Bar graphs of the mRNA expression levels of selected neuronal marker genes. Fold changes were calculated using 2−ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH as an internal control. 2 control (CTL), 1 heterozygous, and 3 homozygous POGZ knockout lines were used in these analyses. CTL1 was designated as 1 in all graphs, and then other clones normalized to CTL1.

Supplementary Fig. 11: mRNA levels of neuronal markers were reduced in cortical neurons derived from POGZ−/− lines. (a) Bar graphs of the mRNA expression levels of POGZ, deep layer cortical neuron markers, TBR1 and CTIP2, and a glutamatergic neuronal marker, VGLUT1 (Clones grouped by genotype in each graph). (b) Bar graphs of POGZ RT-qPCRs shown separately for 2 control (CTL), 1 heterozygous, and 3 homozygous POGZ knockout lines. Three biological replicates were performed. Fold enrichments were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH as an internal control. Error bar represents SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Supplementary Table 3. Information on mutations in CRISPR gene edited human embryonic stem cell lines

Supplementary Table 1: List of primers used in RT-qPCRs

Supplementary Table 2: List of antibodies used in immunocytochemistry and immunoblotting

Supplementary Video 1: Live imaging of neural rosette differentiation from day 20– day 27.

Acknowledgments

We appreciated the thoughtful comments on this manuscript and image analysis from Drs. Qian Chen (University of Toledo) and Louis Dang (University of Michigan). We also thank Dr. Gemma Carvill (Northwestern University) for her help in predicting the outcome of CRISPR mutations.

Funding sources

This work was supported by the Taubman Institute Scholars Fund at Michigan Medicine.

Footnotes

Author footnotes/contributions

Overall conceptualization and experiment design by W.N. with input from J.P.M. Experimental methodology and data collection: Generation of cell lines and RT-qPCRs by L.D., S.P.M., and W.N. Neural differentiation and imaging by L.D. Immunoblotting by L.D., R.A., and M.S. Data analysis by L.D., and W.N. Writing: original draft by L.D and W.N; manuscript editing by J.P.M. The authors had no conflicts of interest to declare to this work.

Reference

- 1.Rosnoblet C, Vandamme J, Volkel P & Angrand PO Analysis of the human HP1 interactome reveals novel binding partners. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 413, 206–211 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nozawa RS, et al. Human POGZ modulates dissociation of HP1alpha from mitotic chromosome arms through Aurora B activation. Nat Cell Biol 12, 719–727 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vermeulen M, et al. Quantitative interaction proteomics and genome-wide profiling of epigenetic histone marks and their readers. Cell 142, 967–980 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dentici ML, et al. Expanding the phenotypic spectrum of truncating POGZ mutations: Association with CNS malformations, skeletal abnormalities, and distinctive facial dysmorphism. Am J Med Genet A 173, 1965–1969 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferretti A, et al. POGZ-related epilepsy: Case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Genet A 179, 1631–1636 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stessman HAF, et al. Disruption of POGZ Is Associated with Intellectual Disability and Autism Spectrum Disorders. Am J Hum Genet 98, 541–552 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White J, et al. POGZ truncating alleles cause syndromic intellectual disability. Genome Med 8, 3 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ye Y, et al. De novo POGZ mutations are associated with neurodevelopmental disorders and microcephaly. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud 1, a000455 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartholomeeusen K, et al. Lens epithelium-derived growth factor/p75 interacts with the transposase-derived DDE domain of PogZ. J Biol Chem 284, 11467–11477 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chylack LT Jr., et al. Lens epithelium-derived growth factor (LEDGF/p75) expression in fetal and adult human brain. Exp Eye Res 79, 941–948 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bluhm A, Casas-Vila N, Scheibe M & Butter F Reader interactome of epigenetic histone marks in birds. Proteomics 16, 427–436 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawkins RD, et al. Distinct epigenomic landscapes of pluripotent and lineage-committed human cells. Cell Stem Cell 6, 479–491 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ibaraki K, et al. Expression Analyses of POGZ, A Responsible Gene for Neurodevelopmental Disorders, during Mouse Brain Development. Dev Neurosci 41, 139–148 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsumura K, et al. Pathogenic POGZ mutation causes impaired cortical development and reversible autism-like phenotypes. Nat Commun 11, 859 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hormozdiari F, Penn O, Borenstein E & Eichler EE The discovery of integrated gene networks for autism and related disorders. Genome Res 25, 142–154 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willsey AJ, et al. Coexpression networks implicate human midfetal deep cortical projection neurons in the pathogenesis of autism. Cell 155, 997–1007 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suliman-Lavie R, et al. Pogz deficiency leads to transcription dysregulation and impaired cerebellar activity underlying autism-like behavior in mice. Nat Commun 11, 5836 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsumura K, et al. De novo POGZ mutations in sporadic autism disrupt the DNA-binding activity of POGZ. J Mol Psychiatry 4, 1 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Rubeis S, et al. Synaptic, transcriptional and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature 515, 209–215 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanders SJ, et al. De novo mutations revealed by whole-exome sequencing are strongly associated with autism. Nature 485, 237–241 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan B, et al. A novel de novo POGZ mutation in a patient with intellectual disability. J Hum Genet 61, 357–359 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fromer M, et al. De novo mutations in schizophrenia implicate synaptic networks. Nature 506, 179–184 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Assia Batzir N, et al. Phenotypic expansion of POGZ-related intellectual disability syndrome (White-Sutton syndrome). Am J Med Genet A 182, 38–52 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markenscoff-Papadimitriou E, et al. Autism risk gene POGZ promotes chromatin accessibility and expression of clustered synaptic genes. Cell Rep 37, 110089 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lui JH, Hansen DV & Kriegstein AR Development and evolution of the human neocortex. Cell 146, 18–36 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seto Y & Eiraku M Human brain development and its in vitro recapitulation. Neurosci Res 138, 33–42 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller DJ, Bhaduri A, Sestan N & Kriegstein A Shared and derived features of cellular diversity in the human cerebral cortex. Curr Opin Neurobiol 56, 117–124 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klofas LK, et al. DEPDC5 haploinsufficiency drives increased mTORC1 signaling and abnormal morphology in human iPSC-derived cortical neurons. Neurobiol Dis 143, 104975 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niu W & Parent JM Modeling genetic epilepsies in a dish. Dev Dyn 249, 56–75 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Fusco A, et al. Acute knockdown of Depdc5 leads to synaptic defects in mTOR-related epileptogenesis. Neurobiol Dis 139, 104822 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkinson B, et al. The autism-associated gene chromodomain helicase DNA-binding protein 8 (CHD8) regulates noncoding RNAs and autism-related genes. Transl Psychiatry 5, e568 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ran FA, et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc 8, 2281–2308 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi Y, Kirwan P, Smith J, Robinson HP & Livesey FJ Human cerebral cortex development from pluripotent stem cells to functional excitatory synapses. Nat Neurosci 15, 477–486, S471 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tidball AM, et al. Variant-specific changes in persistent or resurgent sodium current in SCN8A-related epilepsy patient-derived neurons. Brain 143, 3025–3040 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Binley KE, Ng WS, Tribble JR, Song B & Morgan JE Sholl analysis: a quantitative comparison of semi-automated methods. J Neurosci Methods 225, 65–70 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferreira TA, et al. Neuronal morphometry directly from bitmap images. Nat Methods 11, 982–984 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamaguchi Y & Miura M Programmed cell death in neurodevelopment. Dev Cell 32, 478–490 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yeyeodu ST, Witherspoon SM, Gilyazova N & Ibeanu GC A rapid, inexpensive high throughput screen method for neurite outgrowth. Curr Chem Genomics 4, 74–83 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scholl AJ Prostatectomy; an evaluation of methods. Surg Clin North Am, 1719-1728 (1954). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee LH, Yang H & Bigras G Current breast cancer proliferative markers correlate variably based on decoupled duration of cell cycle phases. Sci Rep 4, 5122 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paulsen B, et al. Autism genes converge on asynchronous development of shared neuron classes. Nature 602, 268–273 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cooper DN, Krawczak M, Polychronakos C, Tyler-Smith C & Kehrer-Sawatzki H Where genotype is not predictive of phenotype: towards an understanding of the molecular basis of reduced penetrance in human inherited disease. Hum Genet 132, 1077–1130 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1: POGZ isoform expression information in GTEx portal. The CRISPR-generated heterozygous mutation (POGZ+/−, red) is located at the beginning of the 5’ end of the POGZ transcript, and the homozygous mutation (POGZ−/−, blue) is located in the middle of the transcript.

Supplementary Fig. 2: Immunolabeling confirmation of pluripotency of stem cells lines used in the current study. POU5F1 (a), SOX2 (b) and NANOG (c) are nuclear proteins (green), and SSEA4 (d) is a cell surface marker (red). CTL: control. Scale bar: 50 μm.

Supplementary Fig. 3: Confirmation of isogenic control (CTL) and POGZ mutant lines by RT-qPCR and immunoblotting (data shown for each clone). (a) Bar graphs of POGZ RT-qPCR in 2 control (CTL), 1 heterozygous, and 3 homozygous POGZ knockout lines. Fold changes were calculated using 2−ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH as an internal control. The PCR primers are located at the 5’end, middle, and 3’ end of POGZ cDNA. (b) Whole cell lysate was blotted against POGZ and actin antibodies, respectively. Nuclear protein lysate was blotted against Anti-histone H3. The 4th homozygous line (POGZ−/− −4) was not used in the current study due to incomplete knockout of the POGZ protein. Anti-actin and anti-histone H3 blots served as loading controls. Equal amounts of protein lysates were used.

Supplementary Fig. 4: Bar graphs of POGZ RT-qPCR of KO and control lines at different stages (data shown for each clone). Bar graphs of POGZ RT-qPCR in 2 control (CTL), 1 heterozygous, and 3 homozygous POGZ knockout lines. Fold changes were calculated using 2−ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH as an internal control.

Supplementary Fig. 5: The loss of POGZ reduces cell proliferation in neural rosettes (data shown for each clone). Scatter plots of the fluorescence intensity ratios of MK167:BB (a) and number of PHH3+ cells per rosette (b). Quantification of TBR2+ cells inside (c) or outside of rosettes (d). 2 control (CTL), 1 heterozygous, and 3 homozygous POGZ knockout lines were used in these analyses. CTL1 was designated as 1 in all graphs, and other clones were normalized to CTL1.

Supplementary Fig. 6: NSCs lose stem cell pluripotency and express the NSC marker Nestin. POU5F1 is a stem cell pluripotency marker (green), NESTIN is a NSC marker (red). BB stains nuclei. Scale bar: 50 μm. 2 control (CTL), 1 heterozygous, and 3 homozygous POGZ knockout lines were used in these analyses. Scale bar: 50 μm.

Supplementary Fig. 7: Whole cell lysates from day 21-26 rosettes were blotted against POGZ, TUBB3, Vinculin, and Actin antibodies. Anti-Actin and anti-Vinculin served as a loading control. Equal amounts of protein lysates were used. 2 controls (CTL1/WA09 and CTL3/PG22-4), 1 heterozygous line (POGZ+/−/PG3), and 3 homozygous POGZ knockout lines (POGZ−/−-1/PG9-3, POGZ−/−-2/PG9-4, POGZ−/−-3/PG22-13) were used in these analyses. Selected immunoblot images from two biological replicates (iN#5 and #7) were shown in the current figure for anti-TUBB3 (a) and anti-POGZ (b). Data were pooled from three biological replicates (iN#5, 7, 10). CTL was designated as 1 in all graphs, and then other clones normalized to CTL.

Supplementary Fig. 8: Time lapse images show the development of neural rosettes. Phase images of neural rosettes (day 15~23) from control (top), heterozygous KO (middle) and homozygous KO (bottom) lines. Phase images of neural rosettes at day 15 were acquired using EVOS imaging system and from days 20~23 using an Incucyte live imaging system. Arrows show migrating neurons. Scale bar: 400 μm.

Supplementary Fig. 9: Neuronal migration in differentiating neural rosettes. Fluorescence micrographs of neural rosettes from control (top), POGZ+/− (middle), and POGZ−/− (bottom) lines at day 15 (a) and day 21 (b) immunostained for TUBB3 (red) and PAX6 (green). BB: nuclear stain (blue). Neuronal migration was less in neural rosettes derived from the POGZ−/− line at day 21 (b). Arrows show migrating neurons. Dotted circles outline neural rosettes. (a) Scale bar: 200 μm. (b) Scale bar: 100 μm.

Supplementary Fig. 10: The loss of POGZ decreases neuronal migration in differentiating neural rosettes (data shown in each clone). (a) Rosette size measured by diameter. (b) Mean intensity of PAX6 normalized by BB. (c) Mean intensity of TUBB3 normalized by BB. (d) TUBB3+ area outside of rosettes vs total area. (e) Average number of TUBB3+ neurons outside of rosettes. (f) DCX+ area outside of rosettes vs total area (CTL1, POGZ+/− and POGZ−/− −2 included in the graph). (g) Bar graphs of the mRNA expression levels of selected neuronal marker genes. Fold changes were calculated using 2−ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH as an internal control. 2 control (CTL), 1 heterozygous, and 3 homozygous POGZ knockout lines were used in these analyses. CTL1 was designated as 1 in all graphs, and then other clones normalized to CTL1.

Supplementary Fig. 11: mRNA levels of neuronal markers were reduced in cortical neurons derived from POGZ−/− lines. (a) Bar graphs of the mRNA expression levels of POGZ, deep layer cortical neuron markers, TBR1 and CTIP2, and a glutamatergic neuronal marker, VGLUT1 (Clones grouped by genotype in each graph). (b) Bar graphs of POGZ RT-qPCRs shown separately for 2 control (CTL), 1 heterozygous, and 3 homozygous POGZ knockout lines. Three biological replicates were performed. Fold enrichments were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH as an internal control. Error bar represents SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Supplementary Table 3. Information on mutations in CRISPR gene edited human embryonic stem cell lines

Supplementary Table 1: List of primers used in RT-qPCRs

Supplementary Table 2: List of antibodies used in immunocytochemistry and immunoblotting

Supplementary Video 1: Live imaging of neural rosette differentiation from day 20– day 27.