Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused unprecedented turmoil necessitating nations to impose lockdowns. Thus, organizations forced employees to work from home (WFH) by leveraging information technology. We explored the impact of WFH on employees during the lockdown. We conducted in-depth interviews of 24 employees across manufacturing and technology-enabled sectors in India and analyzed the data using Gioia’s methodology. Four dimensions emerged from the impact of WFH on employees: role improvisation, stress, isolation, and self-initiated creativity. While some themes were common between the two industrial sectors, other themes varied. For instance, service sector employees reported current work-related stress, whereas manufacturing sector employees reported future-related stress. Interestingly, we discovered sparks of creativity among employees during this period either towards nurturing themselves (technology-enabled sector) or towards solving long-pending organizational issues (manufacturing sector). Most importantly, these creativity sparks were self-initiated. The study is novel as it explores the impact of large-scale WFH enforced during crisis.

Keywords: COVID-19, Work from home, Stress, Creativity, Isolation

Introduction

Mankind has faced the scourge of epidemics and pandemics on numerous occasions in history. The scale of the devastation took on enormous proportions, such as during the Black death of 1350, the Spanish Flu of 1918, and the SARS outbreak of 2003 (Liu & Froese, 2020; Patterson & Pyle, 1991). The present outbreak of COVID-19 involves a novel virus that evades detection in a large fraction of people due to its asymptomatic nature. Further, in the initial stages, the virus uncontrollably spread owing to the extensive movement of people across the globe. Most affected countries imposed partial or total lockdown of their economies towards time-boxing the Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19) (Lau et al., 2020; Remuzzi & Remuzzi, 2020; Tønnessen et al., 2021). Despite its identifiable nature, its mechanisms of action remained largely unknown. Thus, we invoked the typology of crises (Gundel, 2005) to classify COVID-19 as an intractable crisis. The present study is set in the context of the nationwide lockdown imposed by the Indian government from March 26, 2020, during the early stages of the outbreak of COVID-19 in the country. According to Gupta et al. (2020), the Indian economy functioned at only 49–57% of its full activity which led to heightened anxiety among employers regarding the future organizational functioning and among employees regarding their employment security and productivity.

The nature of the crisis was such that it generated emotions of despair, helplessness, and physiological and psychological issues among people (Malik & Sanders, 2021). On a positive note, the current global outbreak was different from the outbreaks of the previous decades and centuries as it was the first to emerge in the backdrop of unprecedented advancements in information and communication technology (Okuda & Karazhanova, 2020). Leveraging the technological revolution, industries could function to varying degrees by using facilities such as remote access and online communication. When employees across the globe were affected with regard to changes in work modalities, it was a good opportunity to investigate the nature and extent of the impact of the crisis on employees. Thus, we draw upon the literature on work from home (WFH) and examine its various impacts on employees for the present study.

Past studies have demonstrated that employees who chose to WFH reported feelings of professional and social isolation due to a lack of sense of belongingness (Ashforth et al., 2000; Cooper & Kurland, 2002; Golden et al., 2008; Mulki & Jaramillo, 2011; Shamir & Salomon, 1985). Trust and camaraderie engender due to physical presence and interpersonal interactions. The psychological feelings of detachment and isolation may be more profound in the lockdown situation as compared to the normal WFH scenario due to the ambiguity of the pandemic itself, several insecurities in the minds of employees, and the overall uncertain economic condition. In the present situation, when WFH was thrust upon a large number of employees in India, the relevance of this scholarship is timely and paramount. In addition, organizations are contemplating that work from anywhere would become the norm in the post-pandemic era, thus, the current investigation assumes significance by providing a succinct description of the challenges faced by employees while working from home. Thus, the present study is guided by the research question: What is the impact of work from home during the COVID-19 lockdown on employees in manufacturing and technology-enabled service sectors?

We contribute to the extant WFH literature by exploring the impact of WFH on employees in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. WFH during the pandemic provides insights for extending the pre-pandemic WFH literature as WFH at such a massive scale had not happened in the industrial history. Though WFH policy existed in many organizations, it was not practiced extensively before the pandemic. However, the scale and rate at which WFH happened during the pandemic signify the biggest organizational design shock (Varma et al., 2022). Moreover, WFH pre-pandemic was a choice wherein the terms and conditions of WFH were unambiguous for the employee and employer (Golden et al., 2008), whereas during the pandemic, employees were forced to WFH with no preparation or guidelines. According to Slavković et al. (2022), for the successful implementation of WFH, the main individual factors are the ability to work alone, self-motivation, and organizational skills. In the present case, when people were suddenly forced to WFH, not all employees had the above skillsets and there was a lack of clarity with respect to rules and procedures, business models, operational activities, job design, organizational cultures, leadership, and HR practices in the WFH context (Slavković et al., 2022). Wang et al. (2021) identified four challenges (work–home interference, ineffective communication, procrastination, and loneliness) as people worked from home during the pandemic. Thus, we extend the call for more research by Ingusci et al. (2022) regarding the impact of WFH on employees by understanding how the characteristics of home-based work and work environment shape employee experience.

In the following sections, we briefly review the literature on crisis, how organizations have responded to the present crisis by encouraging work from home, and the various impacts of WFH on employees. We present our qualitative research design and findings. Finally, we discuss the practical implications of our study findings, theoretical contributions, and avenues for future research.

Theoretical background

Organizational crisis and response

Organizational crises often impact aspects of human resource management (Malik, 2017). The complex and multi-level influences of organizational crises impact people's psychological resources and their work performance (Nguyen et al., 2022). For instance, Malik (2013) examined the impact of the global financial crisis on people practices in the Indian information technology industry and found that the financial crisis had both positive and negative outcomes with regard to people practices. Since human capital is a key determinant of organizational success, organizations must proceed with cautious optimism during times of crisis (Malik, 2013; Malik et al., 2019).

The present crisis of COVID-19 impacted the economic, political, and social life of people across the globe (Malik & Sanders, 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic started as a health crisis but became the greatest global humanitarian crisis since World War II (UNDP, 2020). According to the typology of crises (Gundel, 2005), we classify COVID-19 as an intractable crisis. Intractable crises are sufficiently predictable but almost impossible to influence as their mechanisms of action cannot be explored in-depth due to their complexity. Thus, an intractable crisis makes response difficult, preparedness hard, and impedes countermeasures due to conflicts of interest of stakeholders facing the crisis. Amidst the COVID-19 situation, societies have deployed safety protocols of physical distancing and mobility reduction through the lockdown. Lockdown is considered an emergency protocol that restricts an individual’s movement except for procuring essential supplies. The aim of lockdown is isolation, i.e., the separation of people who have been diagnosed with a contagious disease from people who are not sick (Brooks et al., 2020).

When an unprecedented crisis hits individuals, organizations, or societies, ‘resilience’ or the ability to bounce back deems critical to survive and thrive in the difficult times. Likewise, in the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of resilience surfaced requiring an organization’s systemic change and psychological readiness of individuals (Liu et al., 2020). Businesses were least prepared for a black swan event such as the current pandemic which led to a sudden and complete closure of offices worldwide. In the past organizational crises, many organizations had to shut down, merge, downsize, or restructure to survive (Nguyen et al., 2022). To survive the present economic crisis caused by COVID-19, most organizations (where possible) required their employees to WFH. This was a practical business continuity response of organizations to the mounting economic pressure caused by the pandemic. While under normal circumstances WFH was an option provided by some employers to a sizeable number of employees, the COVID-19 lockdown left WFH as the only viable option for organizations to survive.

Work from home and its effects

The mode of working from any space other than the office has been available in organizations for the past few decades albeit not practiced to a large extent. This mode is often referred to in the literature as work from home, telework, work in third spaces, or smart work hubs (Malik, 2018; Malik et al., 2016a, 2016b). Teleworking is essentially working away from the normal place of work (i.e., office) and working from home or a satellite office or hotel. More recently, smart work hubs have been created as alternate workspace locations or a third space that provides teleworkers geographical and temporal flexibility (Malik et al., 2016a, 2016b). Further, this work modality accommodates employee flexibility in the design of compensation and benefits such as flexible scheduling and differential pay package (Malik, 2018). Employees can also exercise personal agency to achieve favorable work–life balance outcomes (Ali et al., 2017; Malik et al., 2017). While it is interesting to note the above remote work modalities, since employees were asked to WFH during the COVID-19 crisis, we will focus on WFH for the present study.

Work from home is known to create various positive and negative impacts on employees. On the positive side, employees enjoy flexibility with regard to time and space. Employees save time spent on commuting to and from the office and have the flexibility to work at their preferred time (Varma et al., 2022). Employee's level of autonomy is increased due to lack of supervision; hence, the employee can enjoy more flexibility in the choice of working hours and work patterns (Shamir & Solomon, 1985). They can also attend to their personal needs and demands and work as per their convenience, thereby, managing their personal and professional lives. On the flip side, the literature on WFH is replete with its negative impact on social relations such as feelings of isolation, reduced amount of feedback from the supervisor and co-workers, impaired socialization, and lack of belongingness (Golden et al., 2008; Mulki & Jaramillo, 2011; Shamir & Solomon, 1985). Further, Varma et al. (2022) highlight how the level of leader-member exchange (LMX) determines the quality of the employee–leader relationship and trust between them while working from home. Employees who had a high-quality LMX relationship enjoyed more discretion and made fewer adjustments to their personal commitments for work reasons. However, they had a greater sense of obligation and were under constant pressure to reciprocate managerial trust.

We will now focus on employees’ feelings of isolation while working from home. Isolation is a psychological construct that describes employees’ perception of the lack of opportunities for social and emotional interaction with other organizational members (Mulki & Jaramillo, 2011). Workplace interactions help employees assimilate into the organizational culture and enable coordination and cooperation, whereas, in virtual work environments, employees often perceive themselves as a sole entity rather than as part of an organizational framework. Isolation could be perceived professionally and/or socially by the employee (Cooper & Kurland, 2002). Feelings of professional isolation create a fear that being out of sight will limit opportunities for career advancement, whereas social isolation is felt when employees miss the informal interaction they garner by being around others at the workplace. Interpersonal networking, spontaneous discussions, and face-to-face communication facilitate information sharing and build trust. These key mechanisms are thwarted during isolation (Cooper & Kurland, 2002; Gajendran & Harrison, 2007). Feelings of isolation, thus, diminish employees’ self-efficacy and confidence in their abilities (Golden et al., 2008; Mulki & Jaramillo, 2011).

The present study context is very different from WFH as examined in the past literature as there is no historical precedence where employees were required by their organizations to WFH on such a large scale. The impact of reduced social relations on employees will be amplified during the lockdown since employees cannot fulfill their need for relatedness in work and work-related social domains. Further, there is a lack of physical boundary between work and home while working from home. There is psychological disengagement from one role to another without concomitant changes in the physical environment that employees working from home have to deal with, thereby, triggering internal emotional conflict (Ashforth et al., 2000; Shamir & Salomon, 1985). Thus, we believe that the impacts of WFH will hold greater significance on employees during COVID-19 times. Confinement, loss of usual routine, and reduced interpersonal contact will engender feelings of work-related isolation (Brooks et al., 2020; Varma et al., 2022). These effects will be exacerbated by the blurring of work–life boundaries. Such perceptions coupled with anxiety about career progression, doubts of employment security, risk of infection, and fear of death or of losing loved ones, will influence employees’ stress and well-being.

The Indian context

The Indian contextual environment is unique as certain cultural and business singularities typify Indianness. For instance, Laleman et al. (2015) highlight the principle of Karma Yoga meaning our actions affect our lives. Karma Yoga represents a near-zero boundary between ‘work’ and ‘life’ as work is considered worship in the value system of Indians. Further, as highlighted by Malik and Pereira (2016), the Indian culture is greatly influenced by the Vedantic philosophy of dharma (virtue). The effect of dharma is also witnessed in Indian business settings which signifies general welfare (lokasangraha) over personal welfare.

From the business perspective, India is emerging as an economic superpower due to the spectacular growth in industries such as information technology, pharmaceutical, and telecommunications, and several multinational corporations have established their footprints in India (Jaiswal et al., 2022; Pereira & Malik, 2013). India is poised to be Asia’s second-largest economy by 2030 (The Hindu, 2022), however, there is a large void in the literature when it comes to an understanding of people practices (more specifically, WFH in the present study) and its profound impact on people and organizations in the Indian context. Indian business diaspora is unique as India is the world’s largest and most diverse democracy making organizations operate within a particular cultural milieu (Pereira & Malik, 2015a). Since India is a diverse, complex, and economically re-emerging nation (Pereira & Malik, 2015b), this scholarship in the COVID-19 context is imperative and timely.

Method

Sample and data collection

The data collection for the present study was done during the initial weeks of the COVID-19 lockdown in India. To address our research question, we interviewed 24 experienced executives in large private sector organizations in India. We chose participants from both manufacturing and technology-enabled service sectors in order to understand the different ways in which the two broad industrial sectors were coping with the pandemic. Twelve participants in the manufacturing sector were employed in industries such as automobile and fast-moving consumer goods, whereas the remaining participants were employed in industries such as banking and information technology. We interviewed employees in different sectors to gauge the extent to which WFH was prevalent and the impact it had on employees. We expected that while some impact of WFH on employees would be common across sectors, there may be some interesting differences across the two industrial sectors.

We chose participants with at least 10 years of work experience as employees with such experience would be fairly conversant with their own work, subordinates’ work, and the overall business functioning. We believed that experienced employees who so far mostly worked from the office would be able to share deeper insights into how WFH impacted their lives. Participants were employed in different companies spread across different industrial and metropolitan locations in India such as Chennai, Bangalore, Gurugram, and Pune. Though the whole country was in a state of lockdown, we collected data from varied locations to understand how WFH impacted employees living across India. Table 1 summarizes the participants’ and their company’s characteristics. We sought an appointment for conducting the interview after providing the purpose of the study. The participants were assured of anonymity of their responses. All interviews were conducted over the telephone as face-to-face interviews were not possible in the lockdown situation. The interview design was semi-structured in nature (see Appendix). Each interview lasted for 25–30 min and was transcribed within 24 h.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Participant number | Sector | Gender | Experience (in years) | Job function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Metals and mining | Male | 13 | Operations |

| 2 | Renewable energy | Male | 11 | Engineering Design |

| 3 | Information technology | Female | 10 | Human Resources |

| 4 | Financial services | Male | 11 | Business Development |

| 5 | Financial technology | Female | 12 | Program Management |

| 6 | Information technology | Female | 10 | Technology advisory |

| 7 | Paint manufacturing | Male | 10 | Human Resources |

| 8 | Automobile | Male | 10 | Sales |

| 9 | Banking | Male | 10 | Marketing |

| 10 | Financial services | Male | 11 | Market research |

| 11 | Banking | Female | 10 | Finance |

| 12 | Banking | Male | 10 | Sales |

| 13 | Technology for marine logistics | Female | 25 | Human Resources |

| 14 | Banking | Male | 12 | Sales |

| 15 | Auto ancillary | Female | 28 | Human Resources |

| 16 | Technology education | Male | 12 | Teaching & Research |

| 17 | Professional services | Female | 11 | Project Manager |

| 18 | Fast Moving Consumer Goods | Male | 14 | Marketing |

| 19 | Automobile | Male | 10 | Human Resources |

| 20 | Auto ancillary | Female | 12 | Human Resources |

| 21 | Mining & Power generation | Male | 15 | Human Resources |

| 22 | Oil & gas | Female | 13 | Safety |

| 23 | Industrial chemical manufacturing | Male | 10 | Marketing |

| 24 | Electronics | Male | 15 | Supply Chain |

Data analysis

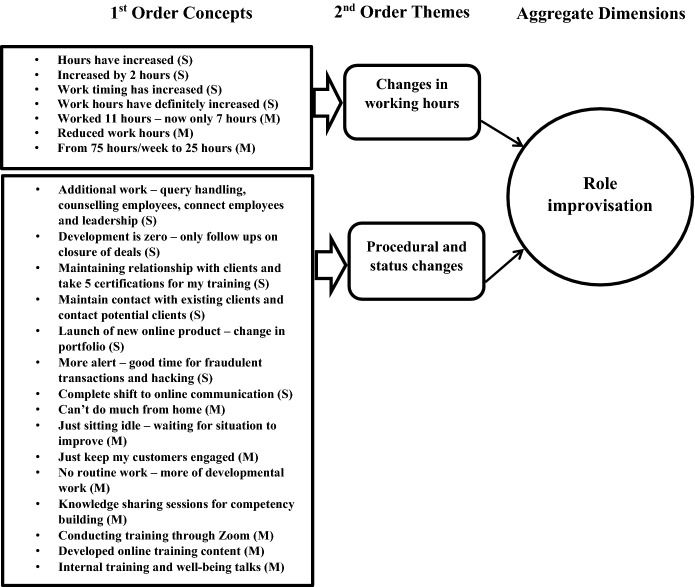

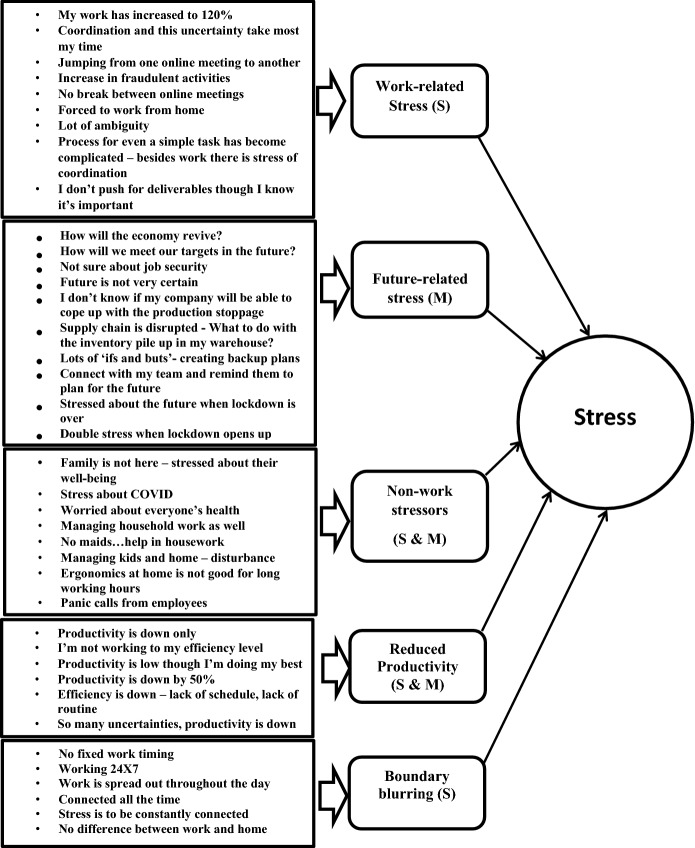

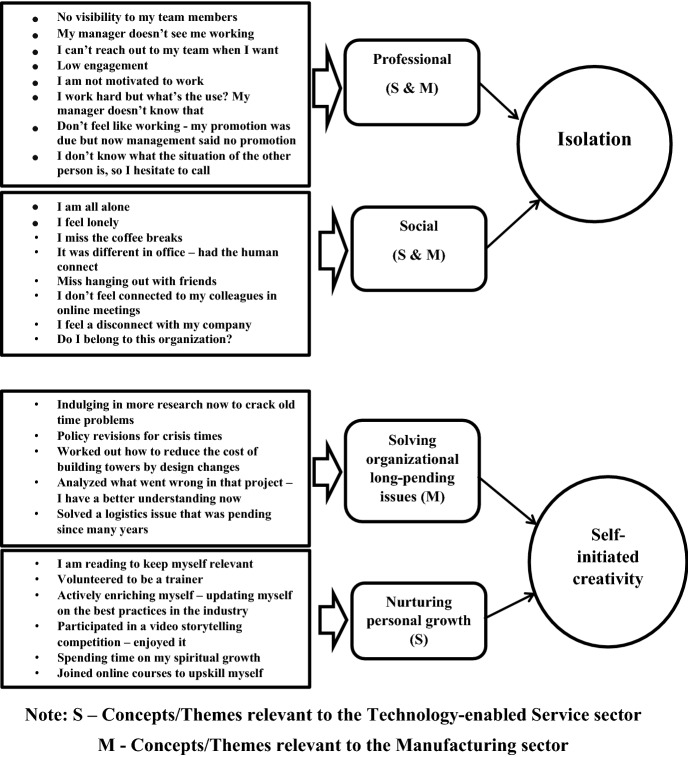

Given the inductive nature of the study, we coded the transcripts following Gioia et al. (2013) methodology, popularly known as Gioia’s methodology. Gioia’s methodology is a systematic approach for bringing rigor to qualitative research. This robust methodology helps in credible interpretations of data, thus convincing the readers that the conclusions are plausible and defensible (Gioia et al., 2013). Group of words, phrases, and terms spoken by the participants emerge early in the research process. This stage is referred to as ‘1st-order concepts’ wherein the participants’ terms are retained verbatim and little attempt is made to distill categories. As the research progresses, categories and themes emerge along with similarities and differences among the categories, thus, leading to a deeper structure in the array called the ‘2nd-order themes.’ At this stage, labels or phrasal descriptors are given to the categories. As compared to the 1st-order concepts, these 2nd-order theoretical themes are abstract in nature. Once the culmination of concepts and themes is done leading to theoretical saturation (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), the themes are distilled into ‘aggregate dimensions.’ Gioia’s methodology presents the research findings through a visual representation called the ‘data structure.’ The 1st-order concepts, 2nd-order themes, and aggregate dimensions form the basis for drawing the data structure. The data structure visually demonstrates the link between the data and the emerging concepts, themes, and dimensions.

Following the systematic procedure for qualitative data analysis by Gioia’s methodology, we transcribed the data by inductively developing a coding scheme including 1st-order concepts, 2nd-order themes, and aggregate dimensions. First, we split the transcripts into manufacturing and technology-enabled service sectors to gain in-depth insights into the impact of WFH on employees in both sectors during the lockdown. Next, we familiarized ourselves with the data by repeatedly reading the transcripts. From the transcripts, we identified the initial ideas representing distinct and raw terms used by the participants, i.e., 1st-order concepts. Next, we created different 2nd-order themes by theoretically clubbing together similar 1st-order concepts. Finally, similar themes were clubbed together to form meaningful aggregate dimensions. Investigator triangulation was done for the study which involves the participation of multiple researchers to provide multiple observations and conclusions. Investigator triangulation not only confirms the study findings but also helps unearth different perspectives, thus, adding breadth to the phenomenon of interest (Carter et al., 2014; Denzin, 1978). The coding process included several iterations to obtain a refined data structure (Fig. 1). Table 2 provides an illustration of the coding system including 1st-order concepts, 2nd-order themes, and aggregate dimensions.

Fig. 1.

Data structure. Note S—Concepts/themes relevant to the technology-enabled service sector. M—Concepts/themes relevant to the manufacturing sector

Table 2.

Data supporting interpretations of the impact of work from home on employees during COVID-19

| Dimensions and themes | Representative quotations from the transcripts |

|---|---|

| 1. Role improvisation | |

| Changes in working hours |

Work is the same but timing has increased…now I login at 9 am and logout at 10 pm …about 3 h more than usual (Service sector, Participant 6) Work hours have definitely increased…I am connected through technology all the time (Service sector, Participant 3) |

| Typically my job is from 10 am-7 pm focusing on selling…now in a typical day my sales divisional head gives instructions to us…then I need to delegate work to my team of 45 members…I also have to call customers and dealers to maintain relationships….that’s all not much work (Manufacturing sector, Participant 8) | |

| Usually, I worked for about 75 h/week but now it’s about 25 h/week (Manufacturing sector, Participant 1) | |

| Procedural and status changes | Reaching out to new clients and client-end delivery has slowed down but other things are going on as usual. (Service sector, Participant 17) |

| We cannot call default customers according to government instructions….so… nowadays online training has increased…how to reduce TAT [turnaround time], about different financial products, policy learning, etc. (Service sector, Participant 11) | |

| As a usual business practice, we used to gift our clients complimentary passes to concerts. Now, we fix an appointment with the client and surprise them with a video call with their favourite artist who would sing songs as requested by the client. Clients are very happy. (Service sector, Participant 9) | |

| I meet 70 HR managers daily over Zoom who in turn check on 8000 employees …we are conducting online training…this was never done before…(Manufacturing sector, Participant 15) | |

| I am in the supply chain so no logistics work now….we spend time mostly in brainstorming and problem solving as there is global pressure to plan the inventory in the warehouse. (Manufacturing sector, Participant 24) | |

| I'm working on policy revision due to this COVID-19 crisis …related to compensation and talent management (Manufacturing sector, Participant 19) | |

| 2. Stress | |

| Work-related stress | This is a good time for fraudulent transactions, hacking and malicious intentions….so I need to be alert and extra cautious…this has increased my stress….Plus, the process for a simple task has increased. Usually, you physically go to a colleague and talk. Now, they either don’t take the call or there is a poor net connection…so apart from work, there is an added stress of coordination. (Service sector, Participant 14) |

| Stress is definitely high…there’s a lot of ambiguity….engagement in the office is easy but now due to the Covid situation, I can’t push for deliverables (Service sector, Participant 13) | |

| Future-related stress | Stress is due to uncertainty—will temporary employees come back? What will the situation be when the market opens up? (Manufacturing sector, Participant 20) |

| “….we don’t know what the market psyche would be after lockdown?” (Manufacturing sector, Participant 23) | |

| “I am stressed about the future when the lockdown is over and the market opens up…. I have heard about 25% pay cuts and job loss.” (Manufacturing sector, Participant 2) | |

| All of us are working on “if–then” scenarios…when lockdown opens how will the market react? (Manufacturing sector, Participant 24) | |

| Non-work stressors | There is tension around COVID…I’m concerned about my parents as they are far away… they are worried about me as I am alone and in the COVID hotspot. (Manufacturing sector, Participant 23) |

| Work-related stress I can handle but I am worried about my team’s health and feel that I have a social responsibility. (Manufacturing sector, Participant 18) | |

| …no maids….I have to help with the household work…my kid thinks I’m on a holiday so I should play with him all the time! (Service sector, Participant 9) | |

| Reduced productivity | …down by almost 50%…but we understand…I have asked the leadership team to think of this situation as “people agenda” and not drive the business agenda. (Service sector, Participant 13) |

|

Productivity is a little low…I’m doing my best but the regular physical meetings give a better picture of what the client is thinking…now I’m not sure… (Service sector, Participant 10) What can I do sitting at home? I don’t have much work….my productivity is very low…(Manufacturing sector, Participant 23) |

|

| Boundary blurring |

There is no difference between work and home (Service sector, Participant 13) I get calls from stressed employees even in the middle of the night (Service sector, Participant 3) I am working 24 × 7 due to this technology….no break at all (Service sector, Participant 10) |

| 3. Isolation | |

| Professional |

I’m working so hard but my manager doesn’t know that….he thinks I am not working properly from home (Service sector, Participant 12) Many times internet connectivity is an issue…this is going to affect my promotion despite my hard work….my team members don’t get to see how I’m struggling (Service sector, Participant 17) Training has increased from once a month to thrice a week….but I don’t feel connected with my colleagues the way it was in the office (Manufacturing sector, Participant 24) |

| Social |

I miss the casual talks I had with my colleagues and friends in the office (Service sector, Participant 16) I feel very lonely….my family is not here….and I don’t feel the same about my work and colleagues as it was before…(Manufacturing sector, Participant 23) I am scared of this loneliness (Manufacturing sector, Participant 24) |

| 4. Self-initiated creativity | |

| Solving organizational long-pending issues | Every year we hire summer interns but this time only I am working closely with them for the first time….we are analyzing survey data that we collected but was kept as it is…now we are getting deeper insights from the data (Manufacturing sector, Participant 7) |

|

With BS6 technology change, most companies have diesel models but we want to keep our product line running with the petrol model. How to do it is a challenge? And what should be the sales pitch to the customers? I have time to think about these now. (Manufacturing sector, Participant 8) I got the time to review the gap between my company policies and actual practices…I need to revamp the policies now (Manufacturing sector, Participant 19) |

|

| Nurturing personal growth | I wanted to have a good command over the best practices in the payment industry but hardly got about 30 min/week. Now, I am spending about 4 h/week reading and learning about it. (Service sector, Participant 4) |

| I am learning how to handle data, clearing my doubts about the policies and products and I am doing a module on big data and analytics (Service sector, Participant 11) | |

| I am indulging in more research now…and taking online classes to update myself and learn better methods of sales negotiation, sales pitch, and credit management. (Service sector, Participant 10) | |

Results

As a result of the above data analysis, several themes and dimensions emerged related to the impact of WFH on employees during the COVID-19 lockdown. The four dimensions are role improvisation, stress, isolation, and self-initiated creativity.

Role improvisation

Due to the closure of offices and factories, there were changes witnessed in the work characteristics of both manufacturing and service industries during the COVID-19 lockdown. These modifications were primarily in terms of the number of working hours of employees and changes in their roles, theoretically referred to as role improvisation.

Changes in working hours

Most participants in the technology-enabled service sector reported an increase in the number of hours they worked. Participant 13 said, I am constantly in touch with employees to understand their concerns regarding COVID…counsel them, keep track of their health status…People's safety is most important right now…usually, I worked from 9 am-6 pm…now I work from 9–9. On the contrary, manufacturing sector employees had limited scope to WFH, and thus, reported a significant reduction in the number of working hours.

Procedural and status changes

Since the technology-enabled service sector continued to work as usual to a large extent, participants indicated minor specific changes in their role with an enhanced focus on employee training and customer relationship management. Most participants noted that they were able to work partially including client engagement and product designing, whereas client-side testing and implementation were suffering due to the lockdown. Further, while training is critical for all employees, the usual workdays keep them extremely busy with very little time for training. Thus, organizations were coaxing employees to train themselves online, attend webinars by subject matter experts, and volunteer for knowledge-sharing sessions. Participants in the marketing and sales function reported customer engagement as the key focus because organizations are concerned about retaining customers post lockdown.

On the contrary, employees in the manufacturing sector reported major changes in their work. For instance, participant 18 who worked in a company manufacturing essential items said, My work has become complicated due to restrictions in movement of goods. Usually, the company manufactures and through distributors and retailers, products reach the customer. Now I am in direct contact with the customers. This was never a part of my portfolio. Participants in the HR function also reported major changes in their work including counseling, stress management, and ensuring employee well-being. Conducting online training to upskill employees and monitoring hygiene practices in plants (which were partially functioning) were major additions to their role. Other participants reported spending a considerable amount of time on research-related activities, building strategies, and brainstorming. Most manufacturing sector participants noted working on if–then scenarios to prepare themselves for the post-lockdown situation. Stress-testing the portfolio across multiple scenarios, brainstorming through assumptions, and creating a dashboard of strategic actions would perhaps help organizations adapt in the future when business restarts.

Stress

Work-related stress

High levels of work-related stress were reported by most participants in the technology-enabled service sector. Even a simple task that could be easily completed in a physical work scenario, had become complicated to accomplish in the WFH mode. This was due to the increased need for coordination and synchronization, thus, increasing employee stress. Further, participants reported that when meetings happened in the office, they would move around and get adequate breaks. However, in the online mode, they just jump from one meeting to another without any break.

Future-related stress

Manufacturing sector employees reported stress primarily related to the future. Since most of the plants and operations had come to a grinding halt due to the lockdown, participants in this sector could not do much from home in terms of tangible work. However, they were stressed thinking about the future of the economy, the future of their sector, the future of their organization, and the future of their jobs once the closure is lifted. Participant 24 said, the stress will be double when the lockdown is over.

Non-work stressors

Besides work-related and future-related stress, non-work stressors were also at play across the two sectors. There was a widespread fear of the COVID-19 virus, ambiguity related to its nature, a lack of conclusive information about its impact, and an increasing number of reported cases and deaths across the globe. Further, a key support system for the Indian working-class families which was not available during the lockdown was domestic help for the household work. Most middle and upper-class Indian houses that are heavily dependent on housemaids for domestic work, found it difficult to perform household chores. These non-work-related stressors contributed to the overall stress among employees.

Reduced productivity

Unsurprisingly, most participants reported reduced levels of productivity as compared to working from the office. Technology-enabled service sector participants noted that despite working for longer hours than usual, poor internet connectivity, lack of adequate ergonomics, uncertainty related to work outcomes, lack of schedule, and lack of motivation were some of the reasons for low levels of productivity. Participants in the manufacturing sector also reported reduced productivity as productivity in this sector is determined by physical production, movement of goods, and sale of tangible products (most of which were not happening in the lockdown).

Boundary blurring

Participants in the technology-enabled service sector reported a blurring of the work–life boundary. Work timings easily spilled over into early morning or late evening hours as employees were connected via technology. Employees experienced stress because they were connected or ‘expected to be connected’ most of the time. Most participants were continuously engaged in telephonic conversations, online meetings, or training sessions throughout the day. Some participants even said that they were connected 24X7. Employees with working spouses, children, and dependents were finding it difficult to balance their work and family demands. The blurring of boundaries between personal and professional lives was a major source of stress reported by employees.

Isolation

Professional

Employees in the technology-enabled service sector had grave concerns regarding their work not gaining visibility in the eyes of their team members and more importantly, their manager. Despite working for longer hours, their productivity was low due to reasons beyond their control; however, the hard work of the employees was going unnoticed due to a lack of supervision mechanisms while working from home. Thus, some respondents felt professionally isolated. Participant 11 said, what’s the use of working so hard when my manager doesn’t see my work? In the manufacturing sector, several online trainings were being organized by the companies, but participants reported a lack of engagement and lack of motivation to participate in the online trainings.

Social

Participants in both sectors shared that they felt lonely, disconnected, and isolated. Virtual meetings did not fulfill the interpersonal bonding, commitment, team spirit, and trust that are fostered from physical presence at the workplace. Employees reported feelings of social disconnection and isolation due to a lack of communication and personal interaction with other organizational members. Employees also felt that their sense of belongingness with the organization had reduced. Participant 4 noted, I feel like I am doing a robotic job….there is no human connect.

Self-initiated creativity

Solving organizational long-pending issues

We found sparks of creativity among the participants while operating from their altered work environment. Several manufacturing sector employees shared that their organizations were grappling with long-pending issues that required cost-optimization, better planning, and research. However, these important parameters were often brushed aside while attending to matters that required quick decision-making. Participant 1 said, We had to build a logistics channel to reach north India. This was there in my mind for many years, but I could never do anything. I had the data but no time to analyze it. Now, I got 8 h of undisturbed time…and I created a proposal. This was done by me. Top management didn’t ask for it. Another participant (number 23) expressed, We do a lot of surveys but never get the time to get deeper into the data…I picked up one such project… spent 2 days on it…I not only got good insights for the company but also realized where we had made mistakes…how could we do things better…This wouldn’t have happened but for this lockdown.

Nurturing personal growth

Technology-enabled service sector employees predominantly utilized their time in nurturing themselves. They deliberated on how to enrich themselves with skills relevant to their future career growth. They used the lockdown time productively to learn about the industry best practices, read subject-related content to keep themselves abreast of current trends, and enrolled themselves in trainings or courses over online educational platforms. Most importantly, investment in nurturing themselves was a self-initiative.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought forth unprecedented global humanitarian challenges. As businesses were shut down, organizations tried operating to the maximum extent possible by directing employees to work from home. In this context, we designed the present study to assess the impact of WFH during the COVID-19 lockdown on employees in the manufacturing and technology-enabled service sectors.

Past scholarly work has demonstrated that role improvisation is a central aspect of managing crises faced by organizations (Crossan, 1998; Lundberg & Rankin, 2014; Rankin et al., 2011; Webb, 2004). Lundberg and Rankin (2014) argue that changes in occupational roles rarely happen during regular work, however, role improvisations often happen in crises as they are necessary for enabling work continuity and success. Invoking the types of role improvisations (Webb, 2004), we believe that changes in working hours and changes in work itself signify procedural and status changes. Procedural changes happen when there are alterations in the way the role is actually performed in order to meet the demands of the crisis while status changes occur when the employee conducts new activities that broaden the scope of their roles. Employees found significant changes in their working hours and changes in their roles itself due to the immediacy of the situation.

Most participants reported high levels of stress and were finding it difficult to cope with the multitude of stressors (work-related and non-work-related) during the lockdown. Our findings are in line with recent works during the COVID-19 pandemic (see, Galanti et al., 2021; Hoff, 2021; Malhotra, 2021). For technology-enabled sectors, the major stressors were low productivity despite increased working hours, increased need for coordination and synchronization, and process-related ambiguity. There was also a blurring of work–life boundaries as reported by technology-enabled service sector employees. They felt that their company expected them to remain connected virtually throughout the day leading to a severe breach in their personal and professional boundaries, thus, causing them stress. For manufacturing sector employees, there was no stress related to work (as they were hardly able to work from home), however, their stress was related to the future. Since the manufacturing sector companies were not able to work during the lockdown, their production and supply chain was badly disrupted. Hence, their concern was primarily around the revival of the industry post the lifting of the lockdown. They were also worried about the uncertain future of the organization and their own employment status. Besides these, the non-work stressors included the ambiguity about the pandemic, the fear of the disease itself, managing household work due to lack of domestic help, lack of appropriate ergonomics to work at home, and managing family responsibilities (home-schooling and elderly care).

Working from home during the lockdown led to feelings of professional and social isolation among employees. Our findings corroborated not only with past works of scholars (such as Cooper & Kurland, 2002; Gajendran & Harrison, 2007; Golden et al., 2008; Mulki & Jaramillo, 2011) but also with recent works (such as Ashforth, 2020; Galanti et al., 2021; Hoff, 2021). Colleagues hesitated to call each other for work because they did not know what the situation of the other person was. They also felt that despite their long working hours, their team members and manager could not ‘see’ their hard work. They feared that lack of visibility of work to the manager will lead to the ‘out-of-sight-out-of-mind’ situation. They also felt socially isolated due to a lack of physical interaction with colleagues and team members. Virtual meetings did not fulfill the need for human interaction and belongingness. Casual conversations in the corridors or coffee rooms are an important part of an employee’s work as it builds a sense of connection with others and most importantly belongingness with the organization. Most employees felt disconnected from their work, team, or organization, as they worked from home.

Creativity boost among employees during the lockdown was an intriguing and novel finding of the study. A remarkable characteristic outcome of some of the historical lockdowns associated with epidemic outbreaks has been the ability of a few individuals to achieve unprecedented heights in their domain. The renowned historian Toynbee (1972) discussed this ability within a ‘challenge-response’ theoretical framework. Massive disruptions such as those caused by COVID-19 qualify as a ‘challenge,’ and the response to a challenge is likely to be unpredictable. While one response to the challenge could be surrender, challenges can also push human creativity to the highest levels. Thus, the ability to leverage information technology and communication to continue business operations despite the challenge of COVID-19 itself represents a collective and creative response of mankind to the challenge.

At an individual level, for instance, Isaac Newton discovered the law of gravitation and calculus in 1666 while living in isolation, when the University of Cambridge was shut on account of the bubonic plague. This year came to be known as ‘Annus Mirabilis’ (the miraculous year) in Newton’s honor (Manuel, 1968). While this is an example of an extreme human achievement in the backdrop of adversity, our study findings demonstrate that it is plausible for creative tendencies to be ignited in individuals when they are subjected to challenging times such as the present situation caused by the pandemic. Further, employees found some quality time to ‘think’ and engage themselves creatively. In the normal course of business, though employees were aware of organizational problems that were important but not urgent, they did not have enough time to deliberate on problem-solving. During the lockdown, employees got some time to think about such long-pending problems and design creative solutions. Likewise, employees were aware of their upskilling needs; however, the lockdown provided them with the opportunity to nurture themselves by enrolling in online courses and training for their upskilling. Our findings support recent studies in the COVID-19 context (for instance, Beghetto, 2021; Du et al., 2021; Impey & Formanek, 2021; Tønnessen et al., 2021).

Practical implications

Managing crises in organizations require a significant amount of effort and collaboration among multiple internal stakeholders including managers, leaders, and employees. As highlighted by Malik and Sanders (2021), meticulous planning by the leaders, decisive action by the managers, and execution by the employees are invaluable competencies required during crisis times. In order to overcome the WFH stress and feelings of isolation experienced by employees, managers must develop the skills of empathy, flexibility, and communicate managerial trust to employees. These will not only reduce employee stress but also develop a sense of consolation that the manager (and the organization) cares for them. Consequently, this will enable a sense of obligation among employees working from home to reciprocate the managerial trust and enhance work performance.

Next, leadership must promote and communicate the organization’s focus on employee well-being and resilience. While this may require investments in human capital and realistic performance management expectations, communication of the same by leaders to employees is extremely critical. Leadership’s ability in handling ambiguity, agility in decision-making, empathy, and creating an organizational culture that facilitates remote work are important competencies to be developed by leaders to lead their organizations through the crisis. At the individual level, skillsets that need to be developed for WFH during (and after) the crisis include the ability to work independently, enhance personal accountability, self-motivation, collaboration, and the mindset to learn continuously (Shankar, 2020; Slavković et al., 2022). Building these skills and behaviors are the thrust areas for individuals and organizations to work smoothly remotely even in the post-pandemic era.

While role improvisation is a foundation of emergency management (Webb, 2004), it is challenging for practitioners to balance the organizational need to survive the crisis times and individuals’ issues during the crisis. Although role improvisation may be necessary to meet organizational demands, managers must be able to manage its side effects on employees. Thus, in the present context, organizations will have to reflect upon their current policies and processes related to WFH and redefine overall functioning to reflect and conform to the changes happening in the larger societal context. The adaptation process would include taking cues from the general and economic conditions, the changing nature of employees’ work, their readiness to return to work, and the impact of the crisis on their attitude and well-being. In the new India post-pandemic phase, organizations will have to adapt themselves to the drastically changing ecosystem by becoming increasingly agile.

Manufacturing sector

In the present pandemic, we found sparks of creativity among employees while coping with their altered work environment. This finding holds practical significance in that organizations should provide a certain amount of liberty in space and time to their employees. This freedom may enable employees to come up with actionable ideas to either improve the existing processes or resolve important issues that had previously not attracted attention due to their non-urgent nature. This was found more relevant in the manufacturing sector where a large fraction of the workforce was not equipped to WFH. While creativity in such an isolated situation may demonstrate itself as a limited benefit for industries, managers should be aware of such possibilities to tap into the creative skills of employees. Identifying creative employees and allowing them solitude to experiment and deeply focus may result in tangible, inspiring, and worthwhile pursuits.

Further, the pandemic has forced manufacturing sector organizations to rethink their workforce models in terms of adapting the roles and required skill sets of employees to optimally function in the post-lockdown situation. Current considerations have brought forth a good opportunity before leaders to assess the roles of all employees in the organization: roles critical for physical presence on-site, flexible roles for on-site presence, and roles that can fully work remotely. For on-site employees, line managers must account for maintaining adequate physical distancing and ensuring that all safety protocols are being strictly followed. Since WFH saves commute time for employees and reduces infrastructure costs for employers, leaders should encourage employees who are willing to continue WFH to develop the abovementioned skillsets to swiftly shift into flexible arrangements (on-site or remote roles) as needed in the new India in the post-pandemic phase.

Technology-enabled service sector

A large fraction of this sector can adequately function virtually via technology, thus, WFH to a considerable extent may continue in the post-pandemic India Inc. However, stress among employees must be alleviated. In their attempt to maintain desired levels of productivity and efficiency, employees tend to overwork. Further, coordinating activities, reaching the right person for troubleshooting, approaching the higher-ups in the organization for guidance, etc., become difficult as people work remotely. While these problems may be brushed aside as hiccups in the sudden response to pandemic lockdown, they highlight actionable areas for smooth business functioning in the post-pandemic scenario. Employees must have the right infrastructure, appropriate ergonomics, access to information and resources, and proper protocols to work efficiently from home.

Further, with the blurring of boundaries between work and home, employers must increase flexibility to account for employees’ work–life balance, while employees themselves must be accountable for their work. Managerial trust in employees is a key consideration in this regard. With limited control/supervision/face-to-face interactions, managers must have faith in their subordinates and should boost their self-confidence. Regular communication of work-related goals would help employees stay focused on the purpose, motivate them to perform, and remain connected to the organizational core. This is critical given that feelings of isolation can become a persistent challenge in a WFH environment. Processes such as interpersonal interactions, unscheduled discussions, and informal learning build trust among organizational members. These key mechanisms are severed during isolation. Thus, leaders need to check the synchronicity of WFH arrangements with an individual’s need to nurture a sense of belonging with the organization. While video meetings may diminish the sense of isolation to some extent, in the new India post-pandemic phase, a hybrid model could be proposed to employees. This model would provide employees an option to work remotely as well as on-site in an alternate timeframe basis as required by the project. This flexible arrangement will not only provide an optimal balance of productivity, efficiency, morale, and connectivity, but also ease the infrastructure, logistics, and maintenance costs for organizations.

Theoretical contributions

This study makes two important contributions to the existing literature. First, we contribute to the growing literature on WFH triggered at a mass scale due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite numerous challenges, the unexpected implementation of the work-from-home model during the pandemic has been a revelation for employees and organizations. Our qualitative study findings help in providing insights into the crisis originated WFH model and its impacts on employees. First, while WFH was an immediate organizational response to the unprecedented crisis, it was forced upon the employees, thus causing them various kinds of stress. Second, the new WFH model created several work-related demands and changed the nature of the work itself. Third, employees had a heightened sense of isolation and lack of belongingness with the organization and its members. Thus, the new theoretical WFH model must take these outcomes into account in order to reap the benefits of WFH.

Second, we contribute to the literature on creativity. While there is evidence of creativity in aloneness or voluntary isolation (Bowker et al., 2017), ours is one of the first studies to find people’s creative tendencies when they were forced to work from home by their employers under conditions of forced isolation. This is because individuals spent uninterrupted and quality time on a task of their choice. Solitude engendered their intellectual capabilities and creative thinking. Thus, time spent in mandatory seclusion enhanced employees’ involvement with the task and fostered creative outcomes. Our study also supports and augments the creativity literature by underscoring the importance of intrinsic motivation (i.e., self-initiated creativity) during the lockdown caused by the pandemic.

Limitations and future directions

An important aspect that future researchers should consider is the individual’s disposition towards remote work. Individuals with personality traits such as conscientiousness and agreeableness may contribute positively while working in remote environments (Neill et al., 2014). Further, not everyone has the ability to work independently, be self-motivated, and collaborate/network effectively remotely. Thus, employees along with their managers must determine whether they can function optimally in a virtual or physical, or hybrid environment. Future research must also measure an individual’s propensity to WFH considering the above skillsets.

Next, with regard to evidence, our study findings are based on employees working from home in India. Since it has been more than two years since the COVID-19 pandemic affected the globe with its multiple waves, future research can compare the outlook of employees WFH in those countries that more were affected by the pandemic with those countries that were relatively less affected.

Further, as more employees and organizations shift to the WFH/hybrid model, several changes will be necessitated in the human resource management policies and practices. For instance, what will be the hiring criterion and service conditions for employees working on-site, working remotely, or in a hybrid arrangement? How will managers measure employee productivity and review the performance of these different segments of the workforce? How will trust be engendered among organizational members? How will the social relations at work change? How will leaders include, value, and lead this mix of the physical and virtual workforce? How will leaders motivate employees to embrace and trust new technologies such as artificial intelligence-mediated knowledge-sharing platforms? How will leaders develop behaviors to deal with the upsurge of negative outcomes among employees such as stress, isolation, exclusion, and lack of belongingness? How will the leaders build and reinforce the culture and values of the organization (especially among the new recruits)? We believe that these avenues are well worthy of further examination and quantitative studies can investigate the phenomenon in depth.

Conclusion

The outbreak of coronavirus, COVID-19 becoming a pandemic, shutdown of economic activities, and confinement of people to their homes—a lot has all happened since 2020. However, rather than meekly succumbing to the crisis, the human spirit was collectively emboldened by continuing their vocation in capacities as much as possible. Individuals working in the home-based virtual environment in India Inc. expressed several modifications in their roles and work itself due to the pandemic demands. Stress levels increased due to work and non-work-related stressors primarily around balancing work and family responsibilities, synchronization of work remotely, uncertainties related to the future, and the deadly nature of the COVID-19 disease. Heightened levels of isolation and lack of belongingness were also experienced by employees as they worked from home. However, on the positive side, sparks of creativity were ignited in these individuals who were forced to WFH. Employees spent quality time upskilling themselves or solving long-pending organizational issues. Most importantly, the creativity was self-initiated. While we did not witness the fruition of creativity within the study’s limited timeframe, we hope organizations will continue to leverage their employees’ creative instincts. With several waves of the COVID-19 pandemic disrupting organizational functioning repeatedly, we believe that a hybrid work-from-home model will be an ideal choice for organizations in the future. Our study provides key insights to managers and leaders towards developing an optimal work-from-home model that will enable resilient business functioning in the post-pandemic new India.

Appendix: Interview schedule

What changes have happened in your work as a consequence of the lockdown?

As compared to your usual levels of stress, how stressed are you these days?

What is your level of productivity these days?

How connected do you feel with your colleagues?

Did you embark upon any new tasks during the lockdown?

Company’s information: Sector.

Personal information: Gender, job function, and total years of work experience.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Akanksha Jaiswal, Email: akanksha.jaiswal@liba.edu.

C. J. Arun, Email: joe.arun@liba.edu

References

- Ali F, Malik A, Pereira V, Al Ariss A. A relational understanding of work-life balance of Muslim migrant women in the west: Future research agenda. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2017;28(8):1163–1181. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2016.1166784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth BE. Identity and identification during and after the pandemic: How might COVID-19 change the research questions we ask? Journal of Management Studies. 2020;57(8):1763–1766. doi: 10.1111/joms.12629. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth BE, Kreiner GE, Fugate M. All in a day's work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Academy of Management Review. 2000;25(3):472–491. doi: 10.2307/259305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beghetto RA. How times of crisis serve as a catalyst for creative action: An agentic perspective. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;11:3735. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.600685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowker JC, Stotsky MT, Etkin RG. How BIS/BAS and psycho-behavioral variables distinguish between social withdrawal subtypes during emerging adulthood. Personality and Individual Differences. 2017;119:283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.07.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter NRN, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2014;41(5):545–547. doi: 10.1188/14.ONF.545-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CD, Kurland NB. Telecommuting, professional isolation, and employee development in public and private organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2002;23:511–532. doi: 10.1002/job.145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crossan MM. Improvisation in action. Organization Science. 1998;9(5):593–599. doi: 10.1287/orsc.9.5.593. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK. Sociological methods: A sourcebook. McGraw-Hill; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Yang Y, Wang X, Xie C, Liu C, Hu W, Li Y. A positive role of negative mood on creativity: The opportunity in the crisis of the COVID-19 epidemic. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;11:3853. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.600837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajendran RS, Harrison DA. The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2007;92(6):1524–1541. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanti T, Guidetti G, Mazzei E, Zappalà S, Toscano F. Work from home during the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine. 2021 doi: 10.1097/jom.0000000000002236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioia TD, Corley JF, Hamilton RN. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational research methods. 2013;16(1):15–31. doi: 10.1037/a0012722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory. Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Golden TD, Veiga JF, Dino RN. The impact of professional isolation on teleworker job performance and turnover intentions: Does time spent teleworking, interacting face-to-face, or having access to communication-enhancing technology matter? Journal of Applied Psychology. 2008;93(6):1412–1421. doi: 10.1037/a0012722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundel S. Towards a new typology of crises. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 2005;13(3):106–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5973.2005.00465.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R., Madgavkar, A., & Yadav, H. (2020). Reopening India: Implications for economic activity and workers. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/india/reopening-india-implications-for-economic-activity-and-workers#

- The Hindu. (2022). ‘India to surpass Japan as Asia’s 2nd largest economy by 2030’—The Hindu. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- Hoff T. Covid-19 and the study of professionals and professional work. Journal of Management Studies. 2021;58(5):1395–1399. doi: 10.1111/joms.12694. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Impey C, Formanek M. MOOCS and 100 Days of COVID: Enrollment surges in massive open online astronomy classes during the coronavirus pandemic. Social Sciences & Humanities Open. 2021;4(1):100177. doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingusci E, Signore F, Cortese CG, Molino M, Pasca P, Ciavolino E. Development and validation of the Remote Working Benefits & Disadvantages scale. Quality & Quantity. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s11135-022-01364-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal A, Arun CJ, Varma A. Rebooting employees: Upskilling for artificial intelligence in multinational corporations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2022;33(6):1179–1208. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2021.1891114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laleman F, Pereira V, Malik A. Understanding cultural singularities of 'Indianness' in an intercultural business setting. Culture and Organization. 2015;21(5):427–447. doi: 10.1080/14759551.2015.1060232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lau H, Khosrawipour V, Kocbach P, Mikolajczyk A, Schubert J, Bania J, Khosrawipour T. The positive impact of lockdown in Wuhan on containing the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Journal of Travel Medicine. 2020;27(3):taaa037. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Froese FJ. Crisis management, global challenges, and sustainable development from an Asian perspective. Asian Business & Management. 2020;19:271–276. doi: 10.1057/s41291-020-00124-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Lee JM, Lee C. The challenges and opportunities of a global health crisis: The management and business implications of COVID-19 from an Asian perspective. Asian Business & Management. 2020;19:277–297. doi: 10.1057/s41291-020-00119-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg J, Rankin A. Resilience and vulnerability of small flexible crisis response teams: Implications for training and preparation. Cognition, Technology & Work. 2014;16(2):143–155. doi: 10.1007/s10111-013-0253-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra A. The postpandemic future of work. Journal of Management. 2021;47(5):1091–1102. doi: 10.1177/01492063211000435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malik A. Post-GFC people management challenges: A study of India's information technology sector. Asia Pacific Business Review. 2013;19(2):230–246. doi: 10.1080/13602381.2013.767638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malik A. Human resource management and the global financial crisis: Evidence from India's IT/BPO industry. Taylor & Francis; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Malik A. Strategic human resource management and employment relations. Springer Nature; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Malik A, Pereira V, editors. Indian culture and work organisations in transition. Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Malik A, Sanders K. managing human resources during a global crisis: A multilevel perspective. British Journal of Management. 2021 doi: 10.1111/1467-8551.12484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malik A, Rosenberger PJ, Fitzgerald M, Houlcroft L. Factors affecting smart working: Evidence from Australia. International Journal of Manpower. 2016;37(6):1042–1066. doi: 10.1108/IJM-12-2015-0225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malik A, Sinha P, Pereira V, Rowley C. Implementing global-local strategies in a post-GFC era: Creating an ambidextrous context through strategic choice and HRM. Journal of Business Research. 2019;103:557–569. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.09.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manuel FE. A portrait of Isaac Newton. Frederick Muller Limited; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Mulki JP, Jaramillo F. Workplace isolation: Salespeople and supervisors in USA. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2011;22(4):902–923. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2011.555133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neill TAO, Hambley LA, Chatellier GS. Cyberslacking, engagement, and personality in distributed work environments. Computers in Human Behavior. 2014;40:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TM, Malik A, Budhwar P. Knowledge hiding in organizational crisis: The moderating role of leadership. Journal of Business Research. 2022;139:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda, A., & Karazhanova, A. (2020). Digital Resilience against COVID-19. Retrieved from https://www.unescap.org/blog/digital-resilience-against-covid-19

- Patterson KD, Pyle GF. The geography and mortality of the 1918 Influenza pandemic. Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 1991;65(1):4–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira V, Malik A. East is East?: Understanding aspects of Indian culture (s) within organisations: A special issue of Culture and Organization 21(5), 2015. Culture and Organization. 2013;19(5):453–456. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira V, Malik A. Investigating cultural aspects in Indian organizations. Springer; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira V, Malik A. Making sense and identifying aspects of Indian culture (s) in organisations: Demystifying through empirical evidence. Culture and Organization. 2015;21(5):355–365. doi: 10.1080/14759551.2015.1082265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin A, Dahlbäck N, Lundberg J. A case study of factor influencing role improvisation in crisis response teams. Cognition, Technology & Work. 2011;15(1):79–93. doi: 10.1007/s10111-011-0186-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: What next? The Lancet. 2020;395:1225–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamir B, Salomon I. Work-at-home and the quality of working life. Academy of Management Review. 1985;10(3):455–464. doi: 10.2307/258127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar K. The impact of COVID-19 on IT services industry-expected transformations. British Journal of Management. 2020;31(3):450. doi: 10.1111/1467-8551.12423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slavković M, Sretenović S, Bugarčić M. Remote working for sustainability of organization during the covid-19 pandemic: The mediator-moderator role of social support. Sustainability. 2022;14(1):70. doi: 10.3390/su14010070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tønnessen Ø, Dhir A, Flåten BT. Digital knowledge sharing and creative performance: Work from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 2021;170:120866. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toynbee A. A study of history: Illustrated. Oxford University Press and Thames and Hudson Ltd; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic: Humanity needs leadership and solidarity to defeat the coronavirus. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/coronavirus.html

- Varma A, Jaiswal A, Pereira V, Kumar YLN. Leader-member exchange in the age of remote work. Human Resource Development International. 2022 doi: 10.1080/13678868.2022.2047873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Liu Y, Qian J, Parker SK. Achieving effective remote working during the covid-19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Applied Psychology. 2021;70(1):16–59. doi: 10.1111/apps.12290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb G. Role improvisation during crises situations. International Journal of Emergency Management. 2004;2:47–61. doi: 10.1504/IJEM.2004.005230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]