Abstract

Titin, the largest single chain protein known so far, has long been known to play a critical role in passive muscle function but recent studies have highlighted titin’s role in active muscle function. One of the key elements in this role is the Ca2+-dependent interaction between titin’s N2A region and the thin filament. An important element in this interaction is I83, the terminal immunoglobulin domain in the N2A region. There is limited structural information about this domain, but experimental evidence suggests that it plays a critical role in the N2A-actin binding interaction. We now report the solution NMR structure of I83 and characterize its dynamics and metal binding properties in detail. Its structure shows interesting relationships to other I-band Ig domains. Metal binding and dynamics data point towards the way the domain is evolutionarily optimized to interact with neighbouring domains. We also identify a calcium binding site on the N-terminal side of I83, which is expected to impact the interdomain interaction with the I82 domain. Together these results provide a first step towards a better understanding of the physiological effects associated with deletion of most of the I83 domain, as occurs in the mdm mouse model, as well as for future investigations of the N2A region.

Keywords: muscle, cardiomyopathy, protein dynamics, protein stability, contraction

Introduction

The contractile unit of striated muscle consists of three filaments, the well-established thin and thick filaments as well as the lesser known titin protein.1–3 Titin is the largest known protein and a single copy of this protein is about 1 μm long and spans an entire half sarcomere with its N terminus in the Z-disk and its C terminus in the M-band. The protein is highly modular with the majority of the sequence composed of multiple copies of intracellular immunoglobulin (IgI4)11 or fibronectin type III (fnIII5) folds (small beta sheet rich domains). These two structural elements are supplemented by non-repetitive segments of protein with undefined structure and a kinase domain at the C terminus.

Titin is thought to act as a molecular ruler in the M-band, Z-disk and A-band by providing a template for multiple protein–protein interactions that define the size and compositions of these sarcomeric regions. In contrast, I-band titin varies significantly between muscle types - mainly due to numerous splice isoforms and the presence of large spans of highly irregular segments. In short, it is postulated that I-band titin acts as an extensible and elastic tether to maintain a link between the thick filaments and the Z-disks.2 This elasticity is provided mainly by stretches of irregular sequence called the PEVK in both cardiac and skeletal muscle and N2B region in cardiac titin (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of I-band titin layout, isoforms and phosphorylation sites. Red boxes: Ig domains; blue boxes: unique, non-repetitive sequences; yellow boxes: PEVK region; pink spheres: phosphorylation sites. All three isoforms of I-band titin in skeletal and cardiac muscle are shown. As the isoform name suggests, the N2A region is found in the N2A and the N2BA isoforms. The N2A region is shown in more detail with individual domains labelled at the bottom. The green bar below indicates the N2A construct used in previous work to investigate I-band titin binding to thin filaments.36 The Purple bar indicates the portion of N2A deleted in the mdm mouse.15

Titin’s I-band region, and especially the PEVK region, undergoes significant levels of differential splicing during development and also as a response to some muscle and heart diseases.6,7 In skeletal muscle, the predominant isoform is N2A, which contains four IgI domains (I80-I83) plus a longer (106 AA) linker sequence connecting I80 with I81 called UN2A just proximal to the PEVK region (see Figure 1). In cardiac muscle, the two most significant isoforms are known as N2B and N2BA. Both isoforms contain the disordered N2B region but the N2BA isoform contains the N2A region as well as more Ig domains between the N2B and PEVK regions, making this isoform significantly larger than the N2B isoform.

There is currently only one well defined structure available for the N2A region, that of Ig81 (PDB 5JOE).8 In addition, it was shown that the UN2A segment assumes an extended, helical conformation even though no structure has yet been determined for this region.8,9 The N2A region acts as a signaling hub3 and interacts with calpains10,11 and the MARP proteins.12 The interaction of the cardiac member of the MARP family (CARP) was mapped onto the UN2A/I81 part of the N2A region.8

In addition to interactions with small regulatory proteins, I-band titin was long assumed to interact with thin filaments in a calcium dependent fashion.13 Initial investigations looking for this interaction had skipped over the N2A region, but recent studies have identified a binding site for F-actin in the N2A region that exhibits increased affinity in the presence of calcium.14 While this study did not isolate the specific domains within N2A associated with this binding interaction, it is speculated that the I83 domain plays a critical role as deletion of most of I83 coding sequence is found in muscular dystrophy with myositis (mdm) mice which leads to early muscle degeneration and death.15 This deletion prevents the increase in titin stiffness that is normally seen upon activation of wild type muscle, potentially because of an interruption of titinactin interactions.16 These observations therefore put the spotlight on N2A IgI I83 and recent results have shown that physiological calcium levels increase the stability of this domain,17 providing a potential mechanism for the calcium sensitivity of the N2A-titin binding. As there is at present no structure available for this domain, we have embarked on its characterization by NMR spectroscopy and have identified the putative Ca2+ binding site suggested to exist in other studies.

Results

NMR spectroscopy & NMR assignment

The I83 domain construct comprises 93 genuine I83 amino acids (residues 8825–8917 in the mouse N2A titin isoform plus additional residues GIDPF at the N terminus following TEV cleavage and GELRSGC at the C terminus resulting from cloning, making the protein in solution a total of 105 amino acids). To keep the residue numbering straightforward for this paper, we simply start with the first residue in the construct. As a consequence, the N-terminal glycine has number 1 while the first genuine residue is T8825 in position 6 and the last genuine residue is K8917 in position 98. As expected for IgI domains,18 the 15N-HSQC of titin I83 is of an excellent quality with a broad spread of peaks in both dimensions and mostly uniform line shapes and peak intensities, facilitating resonance assignment and structure calculation (Figure S1). With the exception of the N-terminal glycine, it was possible to find assignments for all residues.

Of the assigned residues, backbone amide peaks were missing for only three of the non-proline residues (I2, N59 and C63). Out of a total of 105 backbone nitrogens, 105 α carbons, 98 β carbons, 96 γ carbons, 60 δ carbons, 19 ε carbons and 105 backbone carbonyls, a total of 97 (92.4%), 103 (98.1%), 98 (99.0%), 73 (76.0%), 45 (75.0%) and 16 (84.2%), respectively, could be assigned. For some residues (see Figure S2), minor species could also be observed in the 15N HSQC experiment (residues D3-E8 where T6 and E8 appear twice and F35, I39, A83-L85, G89-Q90). It is also noticeable that some peaks in the 15N HSQC are significantly weaker than the average (see Figure S1), such as H24, D36, A38, Q53, H64 and Y65.

Chemical shifts and other NMR parameters were analysed to determine the cis or trans configuration of the prolines (Table 1). The difference of the Cβ and Cγ chemical shifts is the best indicator of cis/trans configuration.19 It points to standard trans configurations for P4, P9 and P73 (expected value for trans: 4.51 ± 1. 37 ppm). The values of P46 (6.89 ppm) and P87 (7.22 ppm) were substantially larger but not sufficiently close to the expected value (9.64 ± 1.62 ppm) to be sure of a cis-configuration. The analysis of regular backbone distances20 in the NOESY experiments shows clearly that P46 is in a trans configuration while no conclusive evidence for either configuration could be identified for P87. The assignment has been deposited with the BMRB, accession code 50015. The secondary structure of I83 was analysed using the backbone secondary chemical shifts allowing the identification of 8 β-strands in agreement with the known fold of domains belonging to the IgI subset of the immunoglobulin family18,21 (see Figure S3).

Table 1. Cis/Trans proline NMR parameters.

NOESY Peak intensities are described in semi-quantitative terms: s = strong, m = medium, w = weak, 0 = genuinely undetectable, n.a. = peak could not be detected for technical reasons e.g. crowding, baseline distortions or overlap with water signal.

| AA | δCβ – δCγ/ppm | Hα – Hα(i-1) | Hα – Hα(i-1) | HN(i-1) – Ha | Hδ – HN(i-1) | Hδ – HN (i+1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P4 | 4.98 ppm | m | 0 | 0 | 0 | m |

| P9 | 4.33 ppm | s | n.a. | 0 | s | 0 |

| P46 | 6.89 ppm | w | 0 | w | w | s |

| P73 | 3.19 ppm | s | 0 | 0 | m | s |

| P87 | 7.22 ppm | 0 | 0 | m | 0 | w |

Structure calculation & validation

The structure calculation was performed as described in the Methods. Distinct sets of structures were calculated with P87 either in cis or in trans using the same distance, H-bond and dihedral constraints. A family of the 20 best energy minimized structures were calculated by Xplor comprising energy penalties based on experimental restraints and the chosen force field. Dihedral restraints were not used in the initial rounds of structure calculations and were only introduced where the NOE based structure gave values for ϕ & ψ values roughly in the area predicted by DANGLE and for the residues in the structured core of the protein (T6-R102). Out of a total of these 95 residues, good agreement between NOE-based and chemical shift-based phi/psi angles was observed for 89 residues with only E23, Q25, A38, K54, N70 and G77 being incompatible. For E23, Q25, A38 and N70 no dihedral constraints were used. The quality of the structure was explored using CCPNMR analysis 2.4 and Procheck.22 A Ramachandran analysis was performed and showed that about 86% (91) of all residues were in the core allowed region with around 11% (10) in the allowed region indicating a good quality backbone structure (Figure S4). Furthermore, the two outliers are G77 and G89, which can accommodate a broader range of backbone conformations. Finally, a global analysis in Procheck demonstrated that packing, contacts and H-bond energies were within allowable parameters and that the structure was built accurately and represents the experimental data (For a summary of all structural statistics see Table 2).

Table 2.

Structure statistics including numbers of restraints and violations as well as summary of PROCHECK analysis of structure quality. G-factors are listed for various quality parameters which indicate the deviation from the expected distribution of values. Values below −0.5 suggest something unusual, values below −1.0 suggest something very unusual.

| NOE derived distances | 3218 |

|---|---|

| Dihedral constraints (ϕ,ψ) | 189 |

| H-bond constraints | 41 |

| Maximal NOE violation | 0.4 Å |

| Maximal dihedral constraint violation | 6.0° |

| ϕ-ψ distribution G | −0.40 |

| χ1-χ2 distribution G | 0.36 |

| χ1 only G | 0.14 |

| χ3 & χ4 G | 0.67 |

| Ω G | 0.32 |

| H-Bond energy G | 0.9 |

| Overall G | 1.4 |

The structure was deposited in the PDB, accession number 6YJ0, with structure families for both configurations of P87.

Structure description

The structure of I83 is well defined according to the experimental NMR restraints as demonstrated by the good agreement amongst the 20 members of the structural family (see Figure 2(A)) with a RMSD of 0.13 Å for the backbone and 0.44 Å for all atoms (for individual residues see Figure S5). Domain I83 has the typical structure of a member of the intramolecular (I-set or IgI) immunoglobulin fold4,18,21 with a total of eight β-strands which are organized into two sheets (A′, B, E, D and A, G, F, C – see Figure 2(B)). In some members of the family, short β-strands are found in the long CD-loop that crosses over one flank of the β-sandwich structure. In I83, some of the hydrogen bonds for these strands are present in the CD-loop but the overall geometry does not quite confirm the existence of fully formed β-strands. Similarly, β-strand A comprises essentially only a β-bulge, another typical feature of IgI domains. Finally, the 310-helix that is often seen in the long EF-loop in other members of IgI domains is very well defined in this structure (see Figure 2(B)). The structural differences between cis and trans configurations at P87 are very limited with only very small variations in the overall shape of the FG-loop. The main difference is in the orientation of E86 (Figure S6).

Figure 2. The structure of I83 is well-defined with unique features.

(A) Multiple superposition of the family of 20 structures. Only the backbone atoms (N, HN, Ca, C, O) are shown. Atoms are coloured in rainbow mode following the polypeptide chain from blue at the N terminus to red at the C terminus. (B) Cartoon view of the best member of the structure family in the same orientation and colours as in A. The positions of the β-strands are indicated. (C) The hydrophobic core and key conserved residues. All non-hydrogen atoms are shown as sticks. Aromatic side chains are coloured in yellow, aliphatic side chains are coloured in green, negatively charged side chains are coloured in red, positively charged side chains are coloured in blue, hydrophilic side chains are coloured in magenta, special residues (Gly, Cys) are coloured in orange, backbone atoms are coloured in grey. Selected residues in the hydrophobic core are labelled. Both figures created with PyMOL.

The hydrophobic core is very well defined (see Figure 2(C)) with the central highly conserved W42 surrounded by numerous aromatic (F12, F29, F35, Y55, F57, Y79) and aliphatic (I10, I16, I19, V21, V33, V40, L49, M66, I68, V71, V81, L85, L97) amino acids (underlined residues indicate high levels of conservation in the sequence alignment (Figure 3(A))) that make for a compact hydrophobic core. The majority of these hydrophobic residues correspond to the key residues defining the I-set.4 The only aberrant amino acid is C31 (also well conserved), whose side chain is fully buried. Its sulfhydryl group is near the ring of W42 and is well positioned to make a hydrogen bond to the backbone oxygen of H64 (see Figure S7) in a manner similar to that seen in titin domain M5.18,23 In addition to the hydrophobic interactions, there is a noticeable number of well defined (K14-E30: Nz-Oe 2.6 Å; K44-D75 Nz-Od 3.4 Å; K54-D75 Nz-Od 4.0 Å; R58-D60 Ne-Od 2.8 Å; E76-K98 Oe-Nz 4.0 Å) or potential (E32-R62; D36-R62; D36-H64; D37-R88; R84-E86, R88-E86, E90-R92) salt bridges on the surface of the protein (see Figure S8). These polar interactions are much less conserved than the hydrophobic interactions. Only K44-D75 (23/26 & 23/26) and K54-D75 (21/26 & 23/26) are somewhat conserved in the alignment in (Figure 3(A)).

Figure 3. Comparison of I83 to similar IgI domains.

(A) Sequence alignment of I83 to a selected set of 26 IgI domains obtained either from structure similarity or sequence similarity searches. Note that the four IgI domains of the N2A region are at the top in inverse order. Conservation is indicated by colours of different intensity based on the level of conservation: strong colour = high level of conservation; faint colour = low level of conservation; threshold for colouring is 25% similarity.57 Green: hydrophobic; Magenta: polar; Grey: glycine; Yellow: cysteine; Blue: positively charged. Residue numbering is given for I83. The position of β-strands and longer loops is indicated by grey bars and lines. The three negatively charged residues in the N-terminal calcium binding site are indicated by red stars. The unsual P87 is indicated by a blue bar. (B) Superposition of similar structures identified by DALI on the structure of I83. Blue: Ti-I83 ; Red: Tw-Ig26 (3UTO); Green: Ti-I27 (1WAA); Magenta: Ti-I1 (1G1C); Cyan: Ti-M4 (3QP3); Orange: Ti-A168 (2J8H); Pink: Ti-M10 (2WWK); Light Blue: Ti-I1 (2A38); Hot-Pink: Ti-I9 (5JDD); Pale blue: Ti-I11 (5JDE); Yellow: Ti-M7 (3PUC); Gray: Ti-I10 (5JDJ); Dark green: Ti-I66 (3B43); White: Tlk (1FHG); Purple: APEP (1U2H); Pale green: Ti-81 (5JOE). Selected amino acids in I83 are labelled and β-strands are shown with labels in boxes. The focus is on the FG-loop on the left and on the BC-loop on the right. Structures were superposed with the matchmaker function in UCSF Chimera and the figure was created with PyMOL.

Sequence and structure comparison

The family of titin IgI domain structures has been studied extensively since the first experimental structures became available.18,24 Given their large number and high levels of conservation of key residues, computational approaches were used extensively to get a good overview and to extract general features.25 With the recent recognition of titin itself as a major source of mutations causing heart and skeletal muscle diseases,26,27 a good understanding of the structures of all domains in titin becomes ever more important.28

Some time ago, the structures of I-band tandem IgI domains (Figure 1) were analysed systematically and were categorized with regards to (i) the presence of a PPxf motif at the N terminus of the domain, (ii) the presence of a lengthened FG-hairpin containing a conserved NxxG motif at its turn, (iii) the conservation of a negatively charged group in linker sequences and (iv) the length of the linkers.29 Based on this analysis, two groups of tandem IgI domains emerged which are distinct in these characteristics: The ‘N-conserved type’ with a long FG hairpin, a PP motif in strand A in at least 60% or at least one proline in at least 90% of domains, a longer BC-loop which, in the case of a PP motif in strand A, also contains a PPh or PxP motif. Most known structures of titin I-band IgI domains18 fall in this category. The second group termed ‘N-variable’ exhibits a broader range of features. It is mainly characterized by shortened BC- and FG-loops that do not pack to each other. Furthermore, there is a reduced number of prolines at the N terminus of the domain (A-strand, BC & FG-loops). This group is represented by the structure of I91 (previously known as I27).24

Based on sequence analysis alone, IgI domain I83 cannot be clearly assigned to either group,8 I83 is predicted by sequence analysis to possess an elongated FG-loop which, however, lacks the conserved NxxG motif. It also does not have any of the PxP or PPx motifs in the BC-loop and has only one proline in the A-strand (Figure 3(A)).

The varying lengths of the key BC and FG loops are apparent in the structural and sequence superposition of I83 (Figure 3). In the sequence alignment (Figure 3(A)), we can see that the BC-loop of I83 is on the short side in strong contrast to I81 which has two residues more in this loop. Conversely, amongst all the aligned IgI domains, the FG-loop of I83 is the longest with the other IgI domains of titin only slightly shorter while those from MyBP-C and obscurin are significantly shorter. In the structure comparison (Figure 3(B)), this increased size of the FG-loop is quite apparent with I83 (blue) being the longest one. Only a small subset of structures shows a significantly shorter FG-loop (titin I1, I10, I11, I27, I81). The structure of the BC-loop of I83 is amongst a group of domains with a ‘down’ conformation (also interestingly observed in titin I1, I10, I11, I27) in which there is little interaction with the FG-loop, a hallmark of the ‘N-variable’ group. All the other IgI domains in this comparison have the BC-loop in an ‘up’ conformation which brings it close to the FG-loop. The BC-loop ‘down’ conformation in I83 opens up a large surface between the FG- and the BC-loops which could be available for a variety of interactions, in the case of I83 most likely with I82 given the very short linker length between them. Intriguingly, the BC-loop in I81 does not match either of these two conformations.

To explore the value of experimental structure determination of a well-established domain fold we compared the experimental structure of I83 with the corresponding homology model from TitinDB.28 The overall agreement, especially with regards to the secondary structure elements is relatively good (RMSD 1.3 Å, Z-score 13.4). However, this is not the case for the long FG-loop which looks completely different in the model and in the experimental structure. In the experimental structure, the FG-loop is very extended while in the model the F- and G strands are much shorter. The correspondingly longer loop in the model structure is folded back over the G-strand towards the β-bulge in the A-strand (Figure S9).

Metal binding

Previous studies have shown that calcium promoted binding of N2A fragments to F-actin14,30 and more recent work17 has shown that 50 μM calcium stabilizes the I83 domain. We therefore investigated calcium and magnesium binding to I83 using NMR and CD spectroscopy. For some residues we can see significant chemical shift perturbations (CSP) in the NMR titration (Figure S10). The CSP values for 10 mM calcium versus buffer control are plotted against the amino acid sequence in Figure 4(A). To explore the positions of residues with substantial CSPs on the surface of the protein, residues with CSPs over 2 * sigma and 4 * sigma were mapped onto the structure of I83 (Figure 4 (B)). We can clearly see two distinct CSP clusters: One is around the end of the CD-loop and the beginning of strand D, the other is at the interface of the FG- and BC-loops. It is interesting to note that the FG-/BC-loop site contains three negatively charged residues close to each other (D36, D37 & E86) amongst the amino acids with increased CSPs (Figure S11).

Figure 4. Metal binding of I83.

(A) Plot of calcium induced chemical shift perturbations (CSP) against the sequence. Thresholds for mapping on the structure are indicated by red lines. Stars indicate residues for which no data could be collected in this experiment. (B) Mapping of calcium induced CSPs on the structure of I83. Cβ atoms are shown for all residues as vdW spheres. Residues coloured in orange are between 2 and 4 sigma, residues coloured in red are >4 sigma, residues coloured in pale cyan are <2 sigma, residues coloured in grey have no values. Figure created with PyMOL. (C) NMR Titration curves for two selected residues for calcium and magnesium titrations. (D) CD titration curves over a broad concentration range of calcium. Curves are shown for wt I83 (squares) and the binding site mutant of I83 (crosses).

The changes in chemical shifts as a function of addition of calcium and magnesium were fitted for the two residues with the largest CSP (D37, F57) to estimate the binding affinity (Figure 4(C)). There is good agreement for the KD values which are 2.2 ± 1.1 and 2.7 ± 1.3 mM for calcium and 34 ± 2.4 and 37 ± 3.1 mM for magnesium.

The calcium titration monitored with far-UV CD spectroscopy (Figure 4(D)) shows a response of the protein at much lower concentrations for wild type I83. The curve was fitted to a two-state equilibrium with a binding affinity of kD = 7.5 ± 1.1 μM.

To explore the discrepancy of calcium binding at high concentration as observed by NMR and at low concentration by CD and previous stability measurements17 we created a mutant version of I83 that should have reduced calcium binding ability. We replaced the three negatively charged amino acids in the N-terminal calcium binding site identified by NMR (Figures 4 and S11) – D36, D37 and E86 by asparagine and glutamine, respectively, in the same construct to create the “Ca-site” mutant. Calcium had a much reduced effect on the CD spectra of the Ca-site mutant with a formal binding affinity of kD = ~90 μM, with a more suspect fit (R2 = 0.76).

We explored other NMR parameters to see if binding could be observed at lower concentrations. Plotting changes in the peak intensity for the first two calcium concentrations (Figure S12) against the sequence gives a noisy picture. However, we can see very small changes to the peak intensity in some residues in the BC and FG loops, overlapping with amino acids that show calcium dependent CSPs at higher concentrations. Interestingly, no such intensity changes are seen for the calcium binding site in the CD-loop.

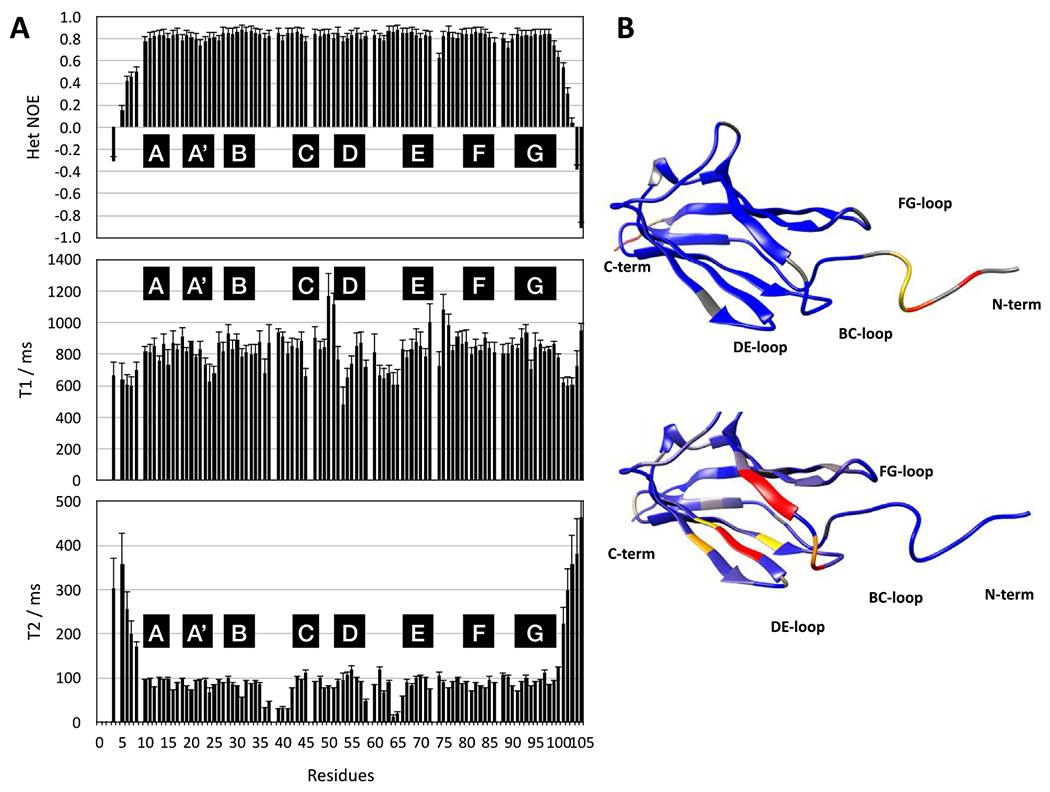

Protein dynamics

The local and overall dynamics was studied by 15N relaxation (1H-15N-heteronuclear NOE, 15N T1, 15N T2) (Figure 5(A)). Initially, the values were used to calculate the rotational correlation time for I83 which came out at 7.9 ± 0.4 ns. This is reasonably close to the value of about 6 ns estimated for a MW of 12kD from the Stokes-Einstein relationship when we consider that the shape of the protein and its hydration shell usually lead to higher values.

Figure 5. 15N relaxation data for I83.

(A) NMR dynamics data with top to bottom 1H-15N heteronuclear NOE, 15N T1. and 15N T2. Secondary structure elements are indicated by black boxes. (B) Dynamics mapped on the structure of I83 using UCSF Chimera.58 Heteronuclear NOE values are mapped on the top, colour coded as Blue: 0.8, Yellow: 0.4, Red: 0.1. On the bottom the T2 values are mapped on the structure, colour coded as Blue: 100 ms, Yellow: 55 ms, Red: 35 ms.

Most apparent in Figure 5(A) is the highly dynamic nature of the termini with low/negative values of the heteronuclear NOE and high values of T2, in good agreement with the RMSD values of the NMR structure (Figure S5). For the main body (residues E8–E100) of the protein, the values of the heteronuclear NOE are very homogeneous around 0.8 as expected for a rigid protein. This suggests that at least on the fast ps time scale, most of the protein assumes a rigid, compact structure. However, some significant variations of the T2 values for residues 35–40 (BC-loop) and 64–65 (DE-hairpin) suggest the presence of slower dynamics on the ms time scale (see Figure 7(B)). To this should be added the observation of minor species for a number of residues at the N terminus, the BC loop and the FG-hairpin (Figure S2) suggesting slow conformational exchange on the time scale of seconds. Interestingly, almost the entire BC-loop appears to be affected and indeed its structure is slightly less well defined than the rest. This loop forms part of one of the two calcium binding sites (Figure S11).

Figure 7. Ca-site mutant I83 is not stabilized at pCa4.3 during chemical denaturation.

The fraction folded as determined by chemical denaturation and measured by tryptophan fluorescence shows a calcium-dependent stabilization for I83 WT. (A) I83 WT exhibits minor stabilization at pCa 6 (open squares) as compared to a Ca-free environment (open circles) by a small increase in the fraction folded at [urea] < 3.5 M. Stabilization at pCa 4.3 (filled circles) is similar to the stabilization at pCa 2 (filled squares), with a larger fraction folded at [urea] ≤ 4 M than a Ca-free environment. An arrow indicates the impact of calcium on I83 WT. (B) The calcium-site mutant demonstrates very small changes to the fraction folded at different calcium concentrations.

Ca2+ binds to the N-terminal end of the I83 domain

If the Ca2+-induced stabilization of I83 observed in our previous studies is due to binding to D36, D37 and E86, this stabilization should be lost if those residues are mutated. This hypothesis was tested using the “Ca-site” mutant described earlier. To ensure that the mutations did not compromise the stability of the protein, fluorescence spectra of each individual mutant were collected. They did not show significant structural differences (Figure S13).

The free energy of unfolding was used to further validate that the substitutions do not impact the structure of I83 and to give a baseline stability for each construct. Chemical and thermal denaturation experiments were conducted on the native I83 and each of the mutant I83 domains. Denaturation experiments yielded similar unfolding curves and free energy values for all derivatives of the I83 domain (Figure 6, Table 4) in the absence of calcium. Small differences are observed in both the thermal and chemical unfolding curves for the E86Q domain. Unfolding begins at lower temperatures and lower concentrations of urea compared to the other domains. The transition for E86Q also demonstrates a more gradual unfolding, resulting in a lower slope for the transition between the folded and unfolded state, resulting in a decrease in both the chemical and thermal stability of I83. Interestingly, the triple mutant is slightly more stable than E86Q, though not completely back to wild-type stability, suggesting that the D36N and D37N mutants help compensate for any instability introduced by the E86Q mutation.

Figure 6. Denaturation curves for I83 WT and I83 with substitutions yield similar unfolding curves.

(A) Overlapping unfolding curves from thermal melts for I83 WT (●), D36N (∎), D37N (◆), E86Q (▲), and Ca-site (x) show similar unfolding despite substitutions. E86 demonstrated a slight decrease in stability, unfolding at lower temperatures with a more gradual transition from the folded to the unfolded state. (B) Unfolding curves from urea denaturation for I83 WT (●), D36N (∎), D37N (◆), E86Q (▲), and Ca-site (x) show similar pattern of unfolding, though E86Q exhibits a slight decrease in stability.

Table 4. Free energy values show that chemical stability is not enhanced for mutant I83 construct at [Ca2+] ≤ 50 μm.

Changes in free energy were determined by comparing the chemical stability of I83 in a calcium-free environment to the stability at a range of calcium concentrations.

| I83 WT | Ca-site Mutant | |

|---|---|---|

| ΔGchem, (kcal/mol) Ca-free | 3.35 ± 0.20 | 3.24 ± 0.14 |

| ΔGchem, (kcal/mol) pCa 6 (1 μM) | 4.02 ± 0.14 | 3.36 ± 0.13 |

| ΔGchem, (kcal/mol) pCa 4.3 (50 μM) | 4.86 ± 0.05 | 3.13 ± 0.19 |

| ΔGchem, (kcal/mol) pCa 2 (10 mM) | 5.64 ± 0.17 | 3.85 ± 0.22 |

| p-Value, 0 vs. pCa 6 (1 μM) | p < 0.01 | p > 0.20 |

| p-Value, pCa 6 vs. pCa 4.3 (50 μM) | p < 0.01 | p < 0.50 |

| p-Value, pCa 4.3 vs. pCa 2 (10 mM) | p < 0.01 | p < 0.02 |

Previous work demonstrated that the I83 domain is stabilized at pCa = 4.317 and we predicted that this stabilization will be altered for the mutants if the BC-/FG-loop is the primary calcium binding site. The wild-type I83 domain is stabilized by almost 1 kcal/mol at pCa = 4.3. In contrast, none of the mutants showed any statistically significant stabilization at the same calcium concentration (Table 4), consistent with our hypothesis that D36, D37 and E86 form the primary calcium binding site.

Calcium stabilization of I83 occurs over a range of concentrations

Our initial stabilization tests were conducted at pCa = 4.3, which is at the upper limit of physiological calcium levels in skeletal muscle, and the calcium level used in the NMR experiments was significantly higher (pCa = 2). We wanted to assess the impact of calcium on stability of this domain and therefore tested the stability of I83 at three different concentrations of calcium. We tested the two pCa’s used in our previous experiments as well as pCa = 6, which is around the activation threshold for muscle. All three concentrations of calcium increased the stability of I83 to varying degrees (Figure 7, Table 4), with higher calcium concentrations having a larger effect on the domain stability. A similar effect was not observed with the Ca-site mutant, further supporting that calcium binding to the BC-/FG-loop region has an overall stabilizing effect on the I83 domain.

Discussion

Titin has long been known to play a critical role in passive tension, but recent studies have highlighted its important role in active force as well. These results, combined with the rise in known disease-related mutations within titin, has made it increasingly important to understand the structural characteristics of the various domains in titin. Recent studies have shown that the N2A region, found in skeletal titin and in one of the two predominant isoforms of cardiac titin, binds to the thin filament in a calcium dependent manner and that the I83 domain in the N2A region is stabilized by physiological levels of calcium. These studies have highlighted the potential importance of this domain and we have determined its structure to help understand its function.

Structural analysis of I83

This domain has a typical IgI structure, though it does not clearly fall into either of the two IgI classifications for I-band IgI domains in titin. I83 contains the elongated FG-loop associated with the ‘N-conserved type’ IgI domains but it lacks the conserved NxxG motif. It also lacks the PxP or PPx motifs associated with this family. While there is currently not a structure of this domain, I82 appears to belong to the group of ‘N-variable’ tandem IgI domains based on sequence analysis (Figure 3(A)). Conversely, domain I81 from the N2A region doesn’t clearly fall into either family of structures in particular concerning its very unusual BC-loop conformation (Figure 3(B)). This suggests that the IgI domains in the N2A region show a high level of heterogeneity, distinct from the neighbouring regions of tandem IgI domains (Figures 1 and 3). A comparison of the experimental structure of I83 with its homology model in TitinDB (Figure S9) also illustrates the value of experimental structures even for well-known folds. While the overall shape of the domain is well represented in the model, the important details, in particular in the loops, are only poorly represented in the model. This is of particular importance for I83 where the N-terminal BC and FG loops are involved in calcium binding which could not be rationalised with the homology model.

Analysis of the experimental structure of I83 also serves to resolve a conundrum regarding the fluorescence spectra of the N2A IgI domains I81, I82 and I83: It was found that fluorescence of the highly conserved tryptophan of the IgI fold decreases in intensity upon unfolding in I81 while it increases for I82 and I83.17 It is well established that contact of tryptophan side chains with polar environments such as that provided by solvents but also neighbouring amino acids can effectively quench fluorescence.31 In the structure of I83 there is a close contact of C31 to the tryptophan indole ring (C31 Sγ – W42 Cη: 3.1 Å, see Figure S7). C31 is missing in I81 but it is present in I82 and one would expect it to be also close to the conserved tryptophan. It is well established that cysteines and disulphide bonds can quench tryptophan fluorescence32 so that the recent experimental observations can be elegantly explained on the base of the structure of I83.

This divergence in structure and function amongst the Ig domains of the N2A region is also reflected in their sequences (I81-I83 Ident: 25%, Sim: 45%; I83-I82: Ident: 22%, Sim: 43%; I82-I81: Ident: 20%, Sim 40%). However, most of the key residues of the hydrophobic core are well conserved (Figures 2(C) and 3(A)) so that the large divergence of stabilities amongst these domains is likely caused by very subtle variations that remain to be elucidated. Beyond protein stability, these structural divergences could reflect distinct functional requirements of this portion of titin that might have evolved independently from the remaining Ig domains in the I-band region. These differences are most likely related to the multitude of both intra- and intermolecular protein–protein interactions made by these four Ig domains. Interestingly, analysis of the surface of the structure of I83 does not immediately provide suggestions for suitable patches for protein–protein interactions. For example, one would normally expect there to be a prevalence of positively charged amino acids to match the overall acidic surface of actin.33 However, there is only a narrow ribbon of positive charges wound around the protein (R84-R92-R15-K14-R58).

It should be noted that both the N- and C-termini contain additional sequence due to the cloning procedures used to make the expression constructs. We used an N-terminal 6-HIS tag for purification with a TEV cleavage site to remove the HIS-tag following purification. This resulted in an additional 5 amino acids on the N terminus. The C terminus also included an additional 7 amino acids due to the absence of a stop codon immediately following the predicted end of the I83 domain to ensure that we did not prematurely truncate the G strand on the domain. We have tested a construct with a stop codon immediately following the G-strand residues using our structure as a guide and there is less than a 0.2 kcal/mol effect on the stability, so we believe that this additional sequence is not perturbing the structure in any significant way. In fact, it should be pointed out that some of the residues added at the C terminus are part of the rigid, well folded structural core. As can be seen (Figures 2(A) and 5(A)) residues G99, E100 and L101, which are not part of the native sequence of I83, extend the G-strand for a short bit. This illustrates well the adaptability of the β-sheet structure and suggests that as long as the overall sequence is long enough to make all essential backbone contacts, the domain is stable.23

Calcium binding and role of I83 in active muscle

As evidence has mounted that titin has a role in active force, it has been postulated that N2A might play a critical role in this function. This is supported by the mdm mouse, which contains an 83 amino acid deletion that begins in the I83 domain of N2A and extends into the PEVK region (Figure 1).16,30,34 Unpublished work from our own lab has shown that the remaining I83 sequence is too short to fold, so that I83 is effectively deleted. Muscle fibres from these mice show that the deletion has little effect on passive tension but active force is severely diminished. The importance of N2A for active force generation is further supported by recent results showing that N2A binds thin filaments and this binding is enhanced by Ca2+,14 even though there are also differing views on this subject.35 The specific binding site for this interaction has not been identified but it is speculated to include the I83 domain. I83 could make a major contribution to N2A binding to the thin filament because N2A constructs containing it bind to thin filaments14 while those lacking it, do not.36 Additionally, stabilisation of I83 by physiological calcium concentrations17 suggests that N2A binding to thin filaments is enhanced by increased stability of I83. However, the deletion at the N2A/PEVK boundary in the mdm mouse is so substantial that other explanations for its effect are currently equally plausible.

The increase of I83 stability by calcium binding is well supported by the observation of direct binding by CD and NMR spectroscopy (Figure 4). Unexpectedly, the calcium concentrations at which binding is observed vary by several orders of magnitude between the two spectroscopic methods. Both sets of experiments were repeated several times using fresh samples so that a technical error as the cause of the discrepancy would appear unlikely. The CD data are rather noisy and it is unusual to see an effect of calcium binding on the level of secondary structure. On the other hand, mutation of residues identified as being involved in binding to calcium at high (mM) concentrations by NMR were shown to have an effect on both binding at low, physiologically relevant concentrations (μM) observed by CD and stabilisation (Figures 4 and 6). It is therefore at present impossible to be certain of calcium binding to I83 at physiological concentrations, but it is equally difficult to completely rule it out.

There is at present no obvious explanation that would reconcile these discrepancies without creating other problems. One could nevertheless speculate that calcium binding does indeed occur at low, physiological concentrations but that NMR has problems to make this visible. The reason for this NMR ‘blindness’ could be caused by the conformational dynamics in the N-terminal binding site formed by the BC and FG loops. Line broadening and multiple species already in the absence of calcium (Figures 5 and S2) and further line broadening already at low calcium concentration (Figure S12) could obscure the existence of any calcium bound species because its peaks could be broadened beyond detection. It remains unclear at present why such species become observable at higher calcium concentrations and more work will be needed to clarify these findings.

One way of doing so would be to observe such ‘invisible’ species using recently developed NMR methods.43 These experiments could characterise low populated conformations by e.g. comparison of carbon chemical shifts to see if the conformation of the BC and/or the FG loop in those states are different from the major form of I83. For a more functional exploration of the calcium binding site identified by NMR it would be intriguing to introduce the three mutations for the N-terminal binding site into cells or whole animals and to explore the effects that these have on the active and passive force development in muscle.

In this context it is important to consider what the structure of I83 tells us about potential binding sites for calcium. Classical binding motifs for calcium include e.g. EF-hand motifs (Figure S14) or clusters of glutamates and neither exist in I83. Nevertheless, the NMR titration identifies two potential binding sites: Firstly, the group of two aspartic (D36, D37) and one glutamic acid (E86) residues on the open surface comprising the BC and FG loops (Figure 4(B)).37 Loops are often a necessary component of calcium-binding sites, in both structures containing EF-hand motifs and those which do not.38 Loops containing glutamic and aspartic acid residues, similar to that found on the I83 domain, can be found in the calciumbinding pockets of calmodulin39 and cadherin40 (Figure S14). Secondly, part of the CD-loop, from T50 to F57, where two backbone carbonyls (T50, E51) could form part of a binding site together with the side chain hydroxyls of T50 & S52. Neither of these sites would be considered optimal for calcium binding. However, proximity of a calcium cation could induce small conformational changes in the relevant side chains which in turn could cause modest rearrangements in the backbone conformation to facilitate calcium binding.

To our knowledge this is the first time that an experimental calcium binding affinity has been reported for a titin IgI domain together with the identification and validation of the binding site. There has been some speculation regarding titin domains I27 (now called I91) and I10 but calcium binding for these domains was only studied indirectly41 or by computer simulation.42 Interestingly, I27 is one of the few titin IgI domains related to I83 with a double negative charge in the BC-loop (see red stars in Figure 3(A)) even though not in identical positions. Otherwise, only some IgI domains of MyBP-C have an identical (C3) or similar (C4) arrangement of negatively charged residues in the BC-loop. However, in these domains the structure of the BC-loop is very different from that of I83. The calcium binding ability of I83 therefore appears to be a unique property of I83 in common with the very individual characteristics of the IgI domains in the N2A region.

Both the BC and the FG-loops, part of the N-terminal binding site, are less well defined than the rest of the protein (Figures 2(A), S5 and S11). In addition, there are minor species observed for both in the HSQC spectrum (Figure S2) and the 15N relaxation experiments indicate μs-ms timescale dynamics in the BC and the neighbouring DE-loop (Figure 5). The N-terminal calcium binding site appears therefore to undergo conformational exchange on multiple time scales. The conformations sampled in this matter could include some that are more suitable for the binding to calcium than the major species which we see in the NMR structure. The multitude of interchanging conformations could be underpinned by a number of different and competing electrostatic interactions amongst the charged residues in the N-terminal binding site (Figure S11). A further contribution to the dynamics at the N terminus of I83 could come from the long FG-loop which adopts an unusual conformation which could be causing the peculiar chemical shifts of P87 making it difficult to define unambiguously its cis/trans configuration. P87 would be unlikely to undergo cis/trans isomerization as part of the N-terminal dynamics of I83 but would allow the FG-loop to adopt a conformation that supports the conformational exchange. The odd behaviour of the FG-loop could also explain the distinct effects of the E86Q mutation on the stability of I83 (Table 3). There are only few structures of titin IgI domains with a proline in the FG hairpin in a similar position to P87, e.g. titin domain I66 (PDB entry: 3B43) has a proline in exactly the same position as in I83 (Figure 3). However, in this case the FG-loop is shorter and forms a proper, tight hairpin with the proline in a trans configuration and a type I β-turn. Furthermore, there is very little NMR data available for titin IgI domains and none for one with a proline in this position.

Table 3.

Changes in free energy (ΔG) values and equilibrium temperatures (ΔTm) for I83 WT and mutants in the absence and presence of calcium. Changes in free energy and equilibrium temperature are shown for thermal denaturation in 1 mM EDTA (Ca-free) or 50 μM Ca2+. Significance of change in the presence of calcium is demonstrated by p-value. All results are reported ± one standard deviation.

| Ca-free |

pCa 4.3 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔGchem (kcal/mol) | ΔGtherm (kcal/mol) | Tm (°C) | ΔGtherm (kcal/mol) | Tm (°C) | |

| I83 WT | 3.35 ± 0.20 | 3.22 ± 0.12 | 53.2 ± 0.6 | 4.19 ± 0.11 p < 0.01 | 57.1 ± 0.4 p < 0.01 |

| D36N | 3.51 ± 0.21 | 3.38 ± 0.14 | 53.2 ± 0.5 | 3.60 ± 0.17 p < 0.10 | 56.1 ± 0.8 p < 0.01 |

| D37N | 3.58 ± 0.13 | 3.48 ± 0.12 | 54.0 ± 1.4 | 3.65 ± 0.18 p < 0.20 | 55.7 ± 0.7 p < 0.10 |

| E86Q | 3.08 ± 0.23 | 2.68 ± 0.16 | 51.8 ± 0.9 | 2.88 ± 0.23 p > 0.20 | 53.4 ± 1.0 p > 0.05 |

| Ca-site | 3.24 ± 0.14 | 3.03 ± 0.18 | 54.4 ± 0.7 | 3.13 ± 0.22 p > 0.50 | 54.6 ± 0.4 p > 0.50 |

Therefore, it can be hypothesized that at least the N-terminal calcium binding site in I83 can adapt by small conformational changes which is supported by the observation of conformational exchange. It is very well possible that the conformational space thus sampled could contain conformations suitable for binding Ca2+ preferentially over Mg2+ but this is still speculative. The location of this putative binding site would put it in proximity of the I82 domain as well so there might be a bridging interaction between the two domains. Such contacts between tandem domains define precisely their relative orientation. It is possible to see almost any possible tandem Ig domain arrangement in the PDB from essentially linear (e.g. 2RIK or with a light kink 3LPW) via an arrangement at a right angle (3B43) to fully antiparallel (4LLA or 3PXH). We could therefore speculate that calcium binding in this area could influence the structure or stability of the I82-I83 domain-domain interface. This could be indirect via stabilisation of the BC and FG loops of I83 in a conformation suitable for specific domain-domain contacts or by stabilising the I82-I83 interface by making bridging contacts between the domains. As we have not observed an effect of calcium on the stability of I8217 the former appears more likely. The precise arrangement of the I82-I83 tandem in the context of the entire N2A region could be important for its physiological role.

In contrast to the N-terminal binding site the hypothetical binding site in the CD-loop is much more likely to be non-physiological. In the first place, we do not see anything unusual in the NMR spectra that would explain why no calcium binding is seen at μM concentration. Furthermore, the effects on the CD spectra of the Ca-site mutant of I83 by calcium are very weak and close to noise. Finally, the Ca-site mutant does not show any stabilisation by calcium at μM concentrations. At higher calcium concentrations (50 μM to 10 mM) it experiences an increase in stability of about 0.72 kcal/mol. This stabilisation is similar to that of wildtype (0.82 kcal/mol) seen over the same concentration range. This extra, low affinity stabilisation can therefore be attributed to the second putative calcium binding site formed by part of the CD-loop (T50-F57, Figure 4(B)). The hypothetical binding site in the CD-loop is therefore, according to all our data, too weak to be relevant at physiological conditions.

In summary, the structure of IgI domain I83 is rather unusual, in particular in the BC & FG loops where it additionally exhibits peculiar conformational dynamics. This part of the protein hosts a calcium binding site where binding helps stabilising the protein, possibly by interfering with the dynamics of the BC & FG-loops. The biological relevance of conformation, dynamics and calcium binding in this part of the protein is very likely related to the formation of a specific interface for the tandem IgI interaction with the preceding domain I82. It is interesting to speculate that the resulting overall shape of this IgI domain tandem is important for the physiological function of the N2A region. However, the difficulty to establish calcium binding at physiologically relevant concentrations makes this a hypothesis that will require further studies.

Materials & Methods

Protein expression and purification

The expression construct for mouse titin IgI domain Ig83, comprising residues 8825–8917 (according to GenBank entry NM_0011652.3 for mouse titin; the equivalent residues in the inferred complete (IC) sequence of human titin are 10074–10167 corresponding to domain Ig-86.28 was cloned into vector pET151/D-TOPO using Invitrogen’s TOPO cloning system. To produce 15N- or 15N-13C-labelled protein, E. coli (BL21*, Invitrogen) cells were grown in M9 minimal media as described previously44,45 supplemented with 15NH4Cl or 15-NH4Cl and 13C D-glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories), respectively, following the protocol of Marley and colleagues.46 Briefly, freshly transformed bacteria were grown at 37 °C in 2 L of standard LB media containing carbenicillin (50 μg/mL) until they reached an OD600 of 0.6–0.8. At this point, cells were transferred into M9 minimal media containing appropriate isotope(s) by collecting cells by centrifugation and resuspending them in 0.5 L of the final M9 minimal media. The culture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour to allow the cells to recover, and protein expression was induced by addition of 0.5 mM IPTG. Protein expression was carried out at 20 °C for 16 hours. Cells were next harvested by centrifugation, and the pellet was stored at −80 °C until purification. Cells were opened by three cycles of French press at 20,000 psi followed by removal of cell debris by centrifugation for 2 h at 9000 rpm in a Sorvall F13S-14x50cy rotor. The supernatant was purified on a 5 mL HisTrap column (GE Healthcare) as per the manufacturers protocol using an Akta Pure chromatography system. Initial purified protein was treated with TEV protease to remove the His-tag and dialysed against three times 1L of wash buffer. The solution was purified again using the same 5 mL HisTrap column with the domain now emerging in the flow through with very high purity and no need for further purification. Approximately 15 mg of pure, labelled protein were obtained from 0.5 L of minimal medium.

To produce I83 WT and mutant constructs for stability tests, plasmids were prepared using site directed mutagenesis (ThermoFisher). Plasmids were transformed into chemically competent Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells and grown overnight at 30 °C. Autoinduction media cultures were inoculated with 0.5% (v/v) of the overnight cultures and grown at 30 °C for 16–18 hours while being shaken at 230 rpm. Autoinduction media cultures for I83 were grown at 20 °C for up to 24 hours. All bacterial cultures were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in lysing buffer containing IMAC wash buffer (25 mM imidazole, 250 mM NaCl, 50 mM K2HPO4), with lysing reagents: 40 μg/ml DNase, 10 mM MgCl2, 200 μg/mg lysozyme, 1% Triton X-100. The cells were lysed using a combination of chemical lysing, freeze–thaw, and French press. The suspension extracted from the French press was spun at 10,000 rpm for 20 minutes at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was passed over a GE HisTrap HP column (GE Healthcare, immobilized metal affinity column (IMAC)) using an imidazole gradient from 50 to 200 mM imidazole to purify the expressed Ig domain. Fractions containing the protein of interest were exchanged into IMAC wash buffer (25 mM imidazole, 250 mM NaCl, 50 mM K2HPO4) and incubated with 1% TEV protease at 4 °C for 48 hours to cleave the HIS-tag. The IMAC purification was repeated following TEV cleavage with the protein without the HIS-tag eluting in the wash. The IgΔHIS protein was further purified by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) on a Superdex-200 analytical column using Ig storage buffer (20 mM HEPES, 138 mM KCl, 12 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) as the mobile phase. Purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE and SEC. Fractions were pooled and flash-frozen in 20% glycerol and stored at −80 °C. Protein quantitation was measured by Bradford assay.

NMR sample preparation, data collection and assignment

NMR samples were prepared in a buffer of 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.2, 100 mM sodium chloride, 2 mM DTT and 0.02% NaN3 with a protein concentration of ~0.8 mM for assignment and 100–200 μM for titrations. Backbone and sidechain assignment of the domain was obtained from a combination of 3D HNCACB, (H)C(CCO)NH, HNCO, HN(CA)CO, 15N and 13C resolved 3D NOESY-HSQCs and a HCCH-TOCSY experiment recorded at 700 and 800 MHz on Bruker Avance spectrometers at 25 ° C. Interproton distances for structure calculation were extracted from 15N and 13C resolved 3D NOESY spectra recorded with 80 ms mixing time at 800 MHz. Metal binding was monitored using 15N HSQC experiments with gradient coherence selection and sensitivity improvement.47 Stock solutions of 1.0 M MgCl2 and CaCl2 were prepared in NMR buffer with the pH adjusted to 7.2. Small aliquots of these stocks were added to 15N labelled protein samples for the titration. Spectra were processed with Topspin 4.0.6 (Bruker) and all assignments were performed with CCPN analysis 2.4.48

Structure calculation & validation

Structure calculation was initiated with Aria 2.3.249 using default parameters from a point were only intraresidual peaks were assigned manually in the 13C resolved 3D NOESY and only intraresidual and sequential peaks were assigned manually in the 15N resolved 3D NOESY. Several rounds of Aria calculations were performed until all NOEs had been assigned or discarded and were checked against the structure. Structure calculation was finalised with XPLOR-NIH 2.3550 installed on a LINUX Beowulf cluster with 128 nodes. Experimental restraints were backbone dihedrals calculated from chemical shifts using DANGLE51 in CCPNMR 2.448,52 and proton-proton distances extracted from 3D 15N NOESY-HSQC as well as aliphatic and aromatic 3D 13C NOESY-HSQC experiments collected with a mixing time of 80 ms. Furthermore, H-bond constraints were added for the last rounds where analysis of the structures of previous rounds identified them in more than 75% of structures. Simulated annealing parameters were mostly the default ones coming as example with the Xplor-NIH installation. Additionally, the RAMA option was used to ensure that residues fit into allowable regions in the ϕ/ψ plot. For detailed numbers and structural statistics see Table 1. The structure was validated using the inbuilt tools of CCPNM 2.4 and PROCHECK.22

Accession numbers

The sequence for the I83 construct was taken from GenBank entry NM_0011652.3 (mouse titin).

The NMR assignment has been deposited with the BMRB, accession code 50015.

The structure was deposited in the PDB, accession number 6YJ0.

Circular Dichroism

Circular Dichroism (CD) spectra of 100 μg/ml samples of I83 were measured at 20 °C with a JASCO CD Spectrophotometer, model J-1500 (JASCO International Co., Tokyo, Japan). Far-UV measurements in the 190 to 250-nm range were made every 0.1 nm at a rate of 100 nm/min using a quartz cuvette with a 0.1 cm path length. Temperature was regulated using a Koolance water circulator. Spectra are the average of four scans and were background subtracted before deconvolution. The signal (mdeg) was converted to molar ellipticity (θ) using Eq. (1):

| (1) |

in which M is the molecular weight, L is the path length of the cell in centimeters, and C is the concentration of the protein in g/L. Secondary structure analysis of CD spectra were completed using K2D3.53

The free energy for the two-state folding processes was determined by using a derivation of the Gibbs-Helmholtz,54 in which the specific heat capacity (Cp) of the folded and unfolded state are assumed to be the same. CD data was fit to values for enthalpy (ΔHm0) and unfolding midpoint (Tm) modelled after published analysis of similar experiments,55 using Eq. (2):

| (2) |

where T is the melting temperature of the protein, such that the midpoint temperature (Tm) yields a free energy of zero.54

Chemical stability

Purified I83 was diluted to a final concentration of 100 μg/ml in storage buffer (±50 μM Ca2+) with varying urea concentrations (0–7.8 M urea). All samples were incubated for one hours at room temperature (~22 °C) prior to data collection. Samples were analyzed in a quartz 96-well plate. Samples were excited at 280 nm and the emission spectra were collected in 1 nm steps from 300 to 450 nm at 20 °C using a SpectraMax M3 plate reader. The Center of Mass (CoM) of each spectrum was calculated using Eq. (3), where I is intensity and ⊽ is the wavenumber:

| (3) |

CoM was plotted as a function of urea concentration and fit using linear extrapolation to determine the ΔGunfolding using Eq. (4):

| (4) |

where x is the concentration of urea. A comparison of a two-state and a three-state unfolding model was applied to stability data and the folding model of best fit was applied to the system.56 A two-way t-test analysis of variance was used to determine statistical differences between the stability of the individual domains. Statistical significance was determined by a value of p < 0.01 when comparing four trials for each domain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

NMR spectra for assignment and structure calculation were recorded at the KCL biomolecular spectroscopy facility and in the MRC national NMR facility at the Francis Crick Institute. The authors want to thank Andrew Atkinson (KCL) and Geoff Kelly (MRC) for help with selection and setting up of experiments. This work was in part supported by a grant from the British Heart Foundation (BHF), PG/15/22/31360.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Colleen Kelly: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization. Nicola Pace: Investigation, Methodology, Validation. Matthew Gage: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision. Mark Pfuhl: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2021.166977.

Abbreviations used: IgI: intracellular immunoglobulin domain; fnIII: fibronectin type three domain; MARP: Muscle Ankryin Repeat Protein; CARP: Cardiac Ankryin Repeat Protein; mdm: muscular dystrophy with myositis; NMR: nuclear magnetic resonance; HSQC: heteronuclear single quantum spectroscopy; NOESY: nuclear overhauser spectroscopy;

References

- 1.Herzog W, (2018). The multiple roles of titin in muscle contraction and force production. Biophys. Rev, 10, 1187–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindstedt S, Nishikawa K, (2017). Huxleys’ missing filament: Form and function of titin in vertebrate striated muscle. Annu. Rev. Physiol, 79, 145–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Myhre JL, Pilgrim D, (2014). A Titan but not necessarily a ruler: assessing the role of titin during thick filament patterning and assembly. Anat. Rec. (Hoboken), 297, 1604–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harpaz Y, Chothia C, (1994). Many of the immunoglobulin superfamily domains in cell adhesion molecules and surface receptors belong to a new structural set which is close to that containing variable domains. J. Mol. Biol, 238, 528–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cota E, Steward A, Fowler SB, Clarke J, (2001). The folding nucleus of a fibronectin type III domain is composed of core residues of the immunoglobulin-like fold. J. Mol. Biol, 305, 1185–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cazorla O, Freiburg A, Helmes M, Centner T, McNabb M, Wu Y, et al. , (2000). Differential expression of cardiac titin isoforms and modulation of cellular stiffness. Circ. Res, 86, 59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotter S, Gout L, Von Frieling-Salewsky M, Muller AE, Helling S, Marcus K, et al. , (2013). Differential changes in titin domain phosphorylation increase myofilament stiffness in failing human hearts. Cardiovasc. Res, 99, 648–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou T, Fleming JR, Franke B, Bogomolovas J, Barsukov I, Rigden DJ, et al. , (2016). CARP interacts with titin at a unique helical N2A sequence and at the domain Ig81 to form a structured complex. FEBS Lett, 590, 3098–3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tiffany H, Sonkar K, Gage MJ, (2017). The insertion sequence of the N2A region of titin exists in an extended structure with helical characteristics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom, 1865, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayashi C, Ono Y, Doi N, Kitamura F, Tagami M, Mineki R, et al. , (2008). Multiple molecular interactions implicate the connectin/titin N2A region as a modulating scaffold for p94/calpain 3 activity in skeletal muscle. J. Biol. Chem,. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raynaud F, Fernandez E, Coulis G, Aubry L, Vignon X, Bleimling N, et al. , (2005). Calpain 1-titin interactions concentrate calpain 1 in the Z-band edges and in the N2-line region within the skeletal myofibril. FEBS J, 272, 2578–2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller MK, Bang ML, Witt CC, Labeit D, Trombitas C, Watanabe K, et al. , (2003). The muscle ankyrin repeat proteins: CARP, ankrd2/Arpp and DARP as a family of titin filament-based stress response molecules. J. Mol. Biol, 333, 951–964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kellermayer MS, Granzier HL, (1996). Calcium-dependent inhibition of in vitro thin-filament motility by native titin. FEBS Lett, 380, 281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dutta S, Tsiros C, Sundar SL, Athar H, Moore J, Nelson B, et al. , (2018). Calcium increases titin N2A binding to F-actin and regulated thin filaments. Sci. Rep, 8, 14575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garvey SM, Rajan C, Lerner AP, Frankel WN, Cox GA, (2002). The muscular dystrophy with myositis (mdm) mouse mutation disrupts a skeletal muscle-specific domain of titin. Genomics, 79, 146–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powers K, Nishikawa K, Joumaa V, Herzog W, (2016). Decreased force enhancement in skeletal muscle sarcomeres with a deletion in titin. J. Exp. Biol, 219, 1311–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly CM, Manukian S, Kim E, Gage MJ, (2020). Differences in stability and calcium sensitivity of the Ig domains in titin’s N2A region. Protein Sci,. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfuhl M, Pastore A, (1995). Tertiary structure of an immunoglobulin-like domain from the giant muscle protein titin: a new member of the I set. Structure, 3, 391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schubert M, Labudde D, Oschkinat H, Schmieder P, (2002). A software tool for the prediction of Xaa-Pro peptide bond conformations in proteins based on 13C chemical shift statistics. J. Biomol. NMR, 24, 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wuthrich K, (1991). NMR of Proteins and Nucleic Acids. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holden HM, Ito M, Hartshorne DJ, Rayment I, (1992). X-ray structure determination of telokin, the C-terminal domain of myosin light chain kinase, at 2.8 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol, 227, 840–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laskowski RA, Rullmannn JA, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM, (1996). AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR, 8, 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pfuhl M, Improta S, Politou AS, Pastore A, (1997). When a module is also a domain: the role of the N terminus in the stability and the dynamics of immunoglobulin domains from titin. J. Mol. Biol, 265, 242–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Improta S, Politou AS, Pastore A, (1996). Immunoglobulin-like modules from titin I-band: extensible components of muscle elasticity. Structure, 4, 323–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fraternali F, Pastore A, (1999). Modularity and homology: modelling of the type II module family from titin. J. Mol. Biol, 290, 581–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoorntje ET, van Spaendonck-Zwarts KY, Te Rijdt WP, Boven L, Vink A, van der Smagt JJ, et al. , (2018). The first titin (c.59926 + 1G > A) founder mutation associated with dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur. J. Heart Fail, 20, 803–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rees M, Nikoopour R, Fukuzawa A, Kho AL, Fernandez-Garcia MA, Wraige E, et al. , (2021). Making sense of missense variants in TTN-related congenital myopathies. Acta Neuropathol, 141, 431–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laddach A, Gautel M, Fraternali F, (2017). TITINdb-a computational tool to assess titin’s role as a disease gene. Bioinformatics, 33, 3482–3485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marino M, Svergun DI, Kreplak L, Konarev PV, Maco B, Labeit D, et al. , (2005). Poly-Ig tandems from I-band titin share extended domain arrangements irrespective of the distinct features of their modular constituents. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil, 26, 355–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nishikawa K, Dutta S, DuVall M, Nelson B, Gage MJ, Monroy JA, (2020). Calcium-dependent titin-thin filament interactions in muscle: observations and theory. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil, 41, 125–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y, Barkley MD, (1998). Toward understanding tryptophan fluorescence in proteins. Biochemistry, 37, 9976–9982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hennecke J, Sillen A, Huber-Wunderlich M, Engelborghs Y, Glockshuber R, (1997). Quenching of tryptophan fluorescence by the active-site disulfide bridge in the DsbA protein from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry, 36, 6391–6400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von der Ecken J, Muller M, Lehman W, Manstein DJ, Penczek PA, Raunser S, (2015). Structure of the F-actin-tropomyosin complex. Nature, 519, 114–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monroy JA, Powers KL, Pace CM, Uyeno T, Nishikawa KC, (2017). Effects of activation on the elastic properties of intact soleus muscles with a deletion in titin. J. Exp. Biol, 220, 828–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cornachione AS, Leite F, Bagni MA, Rassier DE, (2016). The increase in non-cross-bridge forces after stretch of activated striated muscle is related to titin isoforms. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol, 310, C19–C26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linke WA, Ivemeyer M, Labeit S, Hinssen H, Ruegg JC, Gautel M, (1997). Actin-titin interaction in cardiac myofibrils: probing a physiological role. Biophys. J , 73, 905–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nara M, Morii H, Tanokura M, (2013). Coordination to divalent cations by calcium-binding proteins studied by FTIR spectroscopy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1828, 2319–2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu T, Altman RB, (2009). Prediction of calcium-binding sites by combining loop-modeling with machine learning. BMC Struct. Biol, 9, 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beccia MR, Sauge-Merle S, Lemaire D, Bremond N, Pardoux R, Blangy S, et al. , (2015). Thermodynamics of Calcium binding to the Calmodulin N-terminal domain to evaluate site-specific affinity constants and cooperativity. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem.: JBIC: Publ. Soc. Biol. Inorg. Chem, 20, 905–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sotomayor M, Schulten K, (2008). The allosteric role of the Ca2+ switch in adhesion and elasticity of C-cadherin. Biophys. J , 94, 4621–4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu H, Isralewitz B, Krammer A, Vogel V, Schulten K, (1998). Unfolding of titin immunoglobulin domains by steered molecular dynamics simulation. Biophys. J, 75, 662–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DuVall MM, Gifford JL, Amrein M, Herzog W, (2013). Altered mechanical properties of titin immunoglobulin domain 27 in the presence of calcium. Eur. Biophys. J, 42, 301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alderson TR, Kay LE, (2020). Unveiling invisible protein states with NMR spectroscopy. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol, 60, 39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rostkova E, Burgess SG, Bayliss R, Pfuhl M, (2018). Solution NMR assignment of the C-terminal domain of human chTOG. Biomol NMR Assign, 12, 221–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaleska M, Pollock K, Collins I, Guettler S, Pfuhl M, (2019). Solution NMR assignment of the ARC4 domain of human tankyrase 2. Biomol. NMR Assign, 13, 255–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marley J, Lu M, Bracken C, (2001). A method for efficient isotopic labeling of recombinant proteins. J. Biomol. NMR, 20, 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kay L, Keifer P, Saarinen T, (1992). Pure absorption gradient enhanced heteronuclear single quantum correlation spectroscopy with improved sensitivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc, 114, 10663–11665. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vranken WF, Boucher W, Stevens TJ, Fogh RH, Pajon A, Llinas M, et al. , (2005). The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins, 59, 687–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Linge JP, O’Donoghue SI, Nilges M, (2001). Automated assignment of ambiguous nuclear overhauser effects with ARIA. Methods Enzymol, 339, 71–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Tjandra N, Clore GM, (2003). The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J. Magn. Reson, 160, 65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheung MS, Maguire ML, Stevens TJ, Broadhurst RW, (2010). DANGLE: A Bayesian inferential method for predicting protein backbone dihedral angles and secondary structure. J. Magn. Reson, 202, 223–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skinner SP, Goult BT, Fogh RH, Boucher W, Stevens TJ, Laue ED, et al. , (2015). Structure calculation, refinement and validation using CcpNmr Analysis. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr, 71,154–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Louis-Jeune C, Andrade-Navarro MA, Perez-Iratxeta C, (2012). Prediction of protein secondary structure from circular dichroism using theoretically derived spectra. Proteins, 80, 374–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Physical Society of L, Helmholtz HV, (1891). Physical Memoirs Selected and Translated from Foreign Sources, Under the Direction of the Physical Society of London,, vol. 1 Taylor and Francis, London. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Greenfield NJ, (2006). Using circular dichroism collected as a function of temperature to determine the thermodynamics of protein unfolding and binding interactions. Nature Protoc., 1, 2527–2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harder ME, Deinzer ML, Leid ME, Schimerlik MI, (2004). Global analysis of three-state protein unfolding data. Protein Sci.: Publ. Protein Soc, 13, 2207–2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Taylor AC, Graves JM, Murray ND, O’Brien SJ, Yuhki N, Sherwin B, (1997). Conservation genetics of the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus): low mitochondrial DNA variation amongst southern Australian populations. Genet. Res, 69, 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, et al. , (2004). UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem, 25, 1605–1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.