Abstract

Background

Physician referrals are a critical step in directing patients to high-quality specialists. Despite efforts to encourage referrals to high-volume hospitals, many patients receive treatment at low-volume centers with worse outcomes. We aimed to determine the most important factors considered by referring providers when selecting specialists for their patients through a systematic review of medical and surgical literature.

Methods

PubMed and Embase were searched from January 2000 to July 2021 using terms related to referrals, specialty, surgery, primary care, and decision-making. We included survey and interview studies reporting the factors considered by healthcare providers as they refer patients to specialists in the USA. Studies were screened by two independent reviewers. Quality was assessed using the CASP Checklist. A qualitative thematic analysis was performed to synthesize common decision factors across studies.

Results

We screened 1,972 abstracts and identified 7 studies for inclusion, reporting on 1,575 providers. Thematic analysis showed that referring providers consider factors related to the specialist’s clinical expertise (skill, training, outcomes, and assessments), interactions between the patient and specialist (prior experience, rapport, location, scheduling, preference, and insurance), and interactions between the referring physician and specialist (personal relationships, communication, reputation, reciprocity, and practice or system affiliation). Notably, studies did not describe how providers assess clinical or technical skills.

Conclusions

Referring providers rely on subjective factors and assessments to evaluate quality when selecting a specialist. There may be a role for guidelines and objective measures of quality to inform the choice of specialist by referring providers.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-022-07574-6.

KEY WORDS: referrals, specialist, surgery, decision, review

INTRODUCTION

Patients often rely on their primary care provider to recommend high-quality physicians for specialty care1. When selecting a surgeon to perform high-risk surgery, 31% of patients depend exclusively on the recommendation of their primary physician, while 42% consider their physician an equal decision partner2. Similarly, 77% of women with breast cancer select their surgeon based exclusively on their primary physician’s referral3. Among urban patients, patients of color, and those with limited internet access, the referring provider’s recommendation is often the only factor considered when selecting a surgeon3,4.

With large variations in the quality of specialists, the referring provider’s recommendation directly impacts patient outcomes. High-volume, specialized hospitals and surgeons foster better outcomes for patients undergoing complex procedures5–7. Despite initiatives to promote use of high-quality providers8, approximately 30–70% of patients in the USA are treated at low-volume centers for complex oncologic surgery9,10, leading to potentially avoidable complications and mortality11. Variation in outcomes among providers is not limited to the realm of surgical oncology. Provider level variation has also been identified in cardiac surgery12,13, cardiology14,15, advanced endoscopy16, orthopedic surgery17, hernia repair18,19, and bariatric surgery20,21. Given surgical conditions are among the most common indications for referral22,23, the ability of a referring provider to recommend the best available specialist is an essential component of high-quality care.

Utilization of low-quality providers also contributes to racial-ethnic disparities in outcomes. Minorities are less likely to use high-volume hospitals for elective procedures with established volume-outcome relationships24–27. The observed differences in utilization are not entirely explained by a lack of local high-volume hospitals. Black patients are more likely to use a low-quality hospital than White patients even when they live closer to a higher quality hospital28. Improving the sub-optimal outcomes that result from selection of low-quality hospitals and specialists requires a better understanding of the factors considered when choosing among specialists.

Patients place their trust in referring physicians to compare the many options for specialty care and recommend the best specialist. Guidelines facilitate optimal decision-making for when to refer to specialists and how to communicate about mutual patients29, but there is little formal guidance on how to select the best available specialist. While referring providers care deeply about their patients’ outcomes, their choice of specialist does not appear to be driven by outcomes alone. We aimed to synthesize the literature on the factors considered by referring providers when selecting specialists for their patients.

METHODS

Search Strategy

We performed a systematic review of studies examining the factors considered by referring providers when selecting a referral destination for their patients. Relevant articles were identified through a search of PubMed and Embase on July 27, 2021, with guidance from a professional research librarian. We searched for studies containing terms related to referrals (“Referral and Consultation”[MAJR] OR referral* OR consult*), specialty (surgeon* OR surgery OR specialist*), referring providers (“primary care” OR “referring physician” OR “physician referral”), and decision-making (“Decision making”[MAJR] OR choice OR decision OR selection). A search of gray literature was also performed. Titles, abstracts, and full texts were screened by two independent reviewers with disagreements resolved by consensus (CBF, JKT). Covidence software was used to collect and screen studies for inclusion30. The search terms and protocol were specified in advance but not registered. The study was performed in accordance with guidelines set forth by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement31 and Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) recommendations32.

Eligibility Criteria

Our population of interest was healthcare providers who make referrals to specialists. Studies were eligible for inclusion in our systematic review if they asked providers to describe or assess the importance of factors considered in their referral decision, such as in a survey or interview. We included full-text studies describing referrals to any type of medical specialist or surgeon to capture the strategies used across a provider’s referral network. We focused our analysis on recent studies performed within the USA to examine the current practices in our unique healthcare environment in which insurance networks have a strong influence on the specialists available for each patient. We therefore excluded studies reporting on populations outside of the USA, studies written in languages other than English, studies published prior to the year 2000, and review articles. Conference abstracts without a corresponding full-text publication were excluded. For studies using the same cohort of respondents, we selected the most recent study with the highest relevance to our research question.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The primary outcomes of interest were the factors listed in selection of a specialist and the ratings of each factor by referring providers. We extracted data including the stated aims, study design, recruitment strategy, inclusion criteria, enrollment period, number of participants, response rate, participant characteristics, factors described in specialist selection, method for weighing factors, weight given to each factor, and the percentage of physicians who rated each factor highly. Referring provider specialization was classified according to self-reported specialty. The corresponding author was contacted via email if the data were unclear or if additional information was required for analysis. Data were extracted by two researchers (CBF and HEA). Quality assessment was performed by two investigators (CBF and HEA) using the CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist33. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (RRK).

Qualitative Synthesis

To synthesize the factors considered by referring physicians, a convergent integrated approach was used to generate common themes between studies34. Factors described in each study were grouped by similarity of meaning, coded by an overarching theme to describe each group, and categorized according to whether they were related to the specialist’s clinical expertise, interactions between the patient and specialist, or interactions between the referring physician and specialist35. The factor coding and categorization were performed by one investigator (CBF) with consensus by two additional investigators (JKT, RRK). Disagreements were resolved via discussion and group consensus.

RESULTS

Study Selection and Participant Characteristics

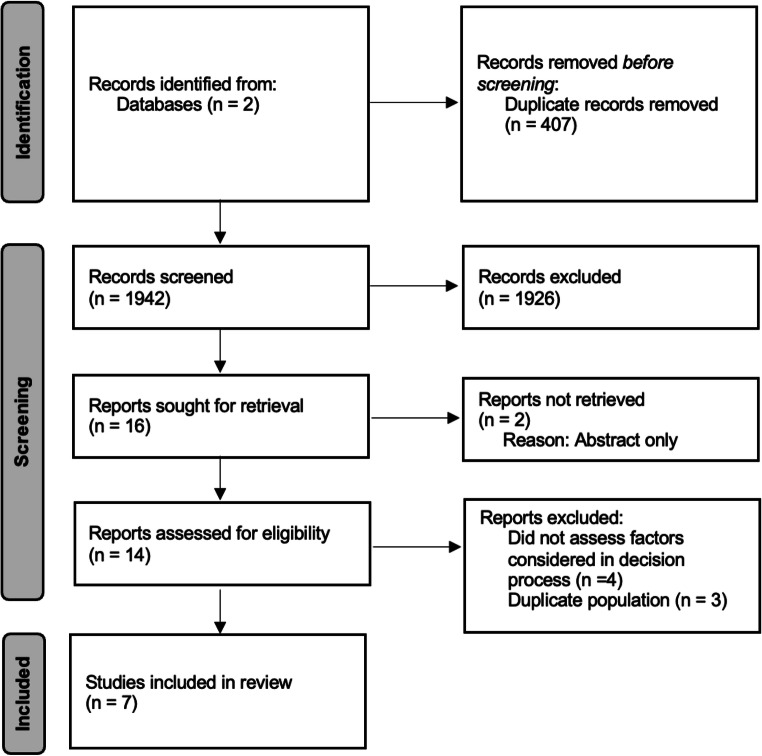

We screened the titles and abstracts of 1,942 studies and identified 16 studies for full-text review (Fig. 1). Two were excluded due to availability only as a conference abstract36,37. Of the 14 studies eligible for full-text review, four were excluded because they did not assess factors considered in the referral decision process38–41, and three were excluded due to a duplicate population22,42,43. The final systematic review included seven studies that met all inclusion and exclusion criteria23,44–49. Five studies consisted of surveys to referring providers rating the relative importance of different factors in their decision process23,44–47. Two studies were semi-structured interviews evaluating referral practices48,49 (Table 1). Four studies investigated referral practices broadly23,44,45,49, while others focused on referrals to certain specialist groups: cardiac surgeons47, hematologists46, and colorectal surgeons48. Quality assessment showed the studies were of acceptable quality overall (Table 1 in Supplement).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Reference | Aims | Study design | Recruitment strategy | Inclusion criteria | Enrollment period | Population (response rate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forrest et al. 2002 | “To examine family physicians’ referral decisions as occurring in two phases: whether to refer followed by to whom to refer” | Phone survey, questionnaire completed each time enrolled physician made a referral | Direct mailings to physicians, articles and notices in newsletters and journals, and presentations at conferences | Physician members of ASPN, Medical Group Management Association, local and regional networks (Minnesota Academy of Family Physicians Research Network, the Wisconsin Research Network, the Dartmouth Primary Cooperative Research Network (COOP), and the larger community of primary care physicians, who practice in US, and are finished with training | 1997–1998 | 141 (41%) |

| Kinchen et al. 2004 | “To determine the importance of factors in primary care physician’s choice of specialist when referring patients and to compare importance ratings by physician’s race and sex” | Cross-sectional survey with 17-item questionnaire asking about importance of factors when choosing a specialist | Stratified random sample to obtain equal numbers of black female, black male, white female, and white male physicians. Mailed survey instrument. | National sample of primary care physicians who see adult patients, drawn from the American Medical Association Physicians Professional Data | 2000 | 558 (59.1%) |

| Abel et al. 2012 | “To survey a broad sample of PCPs as to their referral practices for suspected hematologic malignancies” | Surveys to primary care physicians in Massachusetts regarding referral practices for suspected hematologic malignancies | Random sample of PCPs mailed survey with follow up by phone | Primary care physicians in Massachusetts provided by American Medical Association | 2010 | 134 (70.5%) |

| Barnett et al. 2012 | “To examine the reason why primary care and specialist physicians choose certain specific colleagues to refer to and how those reasons differ by specialty” | Cross-sectional survey. Physicians were given list of specialists in their professional network (who shared Medicare patients in 2006), asked to give two reasons other than clinical skill for referral to each physician | Invited by mail to complete web-based survey. Non-responders contacted by email and phone | Physicians in office-based specialties who were members of an academic physician’s organization in Boston area, who treated Medicare patients in 2006 | 2010 | 386 (63%) |

| Brown et al. 2013 | “To understand current opinions on cardiac surgery report cards and their use 20 years after their introduction in New York State” | Survey to cardiologists in New York who made referrals to cardiac surgeons to assess use of report cards in making referrals to cardiac surgeons | Mailed questionnaire followed by email and phone calls | Cardiologists who were members of the American College of Cardiology in New York who made ≥ one referral to cardiac surgeons | 2011 | 317 (23%) |

| Gao et al. 2021 | “To investigate the factors that guide provider management and referral of patients with rectal cancer” | Semi-structured interviews with gastroenterologists and community-based general surgeons with open-ended questions with probes for clarification | Letters mailed, phone calls to sample, followed by purposeful and snowball sampling through networking at institutions | Gastroenterologists and general surgeons who perform colonoscopies in Iowa. Contact information obtained from Iowa Health Professions Inventory | 2018–2019 | 16 |

| Makovkina and Kern 2021 | “To determine how PCPs, nurses, and staff members at primary care practices choose specific specialists for their patients and to determine how the organizational affiliation of the specialist is considered, if at all” | Interviews with staff at two primary care practices in NYC | Recruited at in person meetings at each practice | Internists, pediatricians, and nurses at two primary care practices that are part of an academically affiliated physician organization in New York, NY | 2019 | 23 (50%) |

In total, the seven included studies accounted for 1,575 referring providers. The population of referring providers classified their specialization as primary care or family practice (n=552), internal medicine (n=317), and medical specialties (n=511), with the remainder of the participants in other disciplines including nursing and administrative staff. Respondents across all studies were 65.1% male and 34.9% female. Of the studies that reported the race of participants, the population of respondents was 67.8% White, 22.6% Black, 2.4% Asian, and 7.3% other races or declined to list race. Of studies that listed time in practice, providers had a mean of 13.5 years of experience following residency training. Of studies that reported practice location, referring providers worked in the Northeast (69%), South (13.1%), Midwest (10.9%), and West (6.9%). The majority worked as part of a group practice (79.6%) with a minority working in solo practice (20.4%).

Qualitative Synthesis

We included themes elicited in all seven studies in the qualitative synthesis. Thematic analysis revealed several common factors across studies (Table 2). When reasons for selecting a specialist were clustered, sixteen unique factors were considered by referring providers during their decision-making process (Table 2 in Supplement). Several notable factors related to the clinical expertise of the consultant, such as clinical skill23,44,47,49, training44, communication skills44,47, clinical outcomes47, summative assessment44, and affiliation with specialized hospital systems46,49. Other factors emphasized the interactions between the referring provider and the consultant, such as a pre-existing personal relationship23,44,46,49, ease and quality of communication (e.g., shared medical records system)44,49, reciprocity44,45, expectation of patient returning to the referring provider44,46, reputation44, and practice affiliation44–49. Finally, some considerations related to interactions between the patient and the consultant, such as prior patient experiences23,44,45,47, rapport44,45, convenience of location23,44–46,48,49 and scheduling23,44,45,49, preferences23,44–46,49, and insurance coverage23,44,46,49.

Table 2.

Range of Factors Considered by Participants of Each Study When Making Referrals by Relational Domain

| Factor considered when making referral decision | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Specialist’s clinical expertise | Interactions between patient and specialist | Interactions between referring physician and specialist | |

| Forrest et al. 2002 | Technical capacity |

Quality of prior feedback Appointment availability Patient request Requirement of patient’s health plan Proximity of specialist to patient’s home |

Personal knowledge of the specialist |

| Kinchen et al. 2004 |

Medical skill Board certification Quality of communication Medical school Fellowship training institution |

Previous experience with specialist Patient convenience Office location Appointment timeliness Likelihood of good patient-physician rapport Insurance coverage Patient preference for particular specialist |

Specialist returns to primary physician PCP relationship with specialist Hospital affiliation Attitudes of colleagues towards specialist Specialist refers patients to primary physician |

| Abel et al. 2012 |

Reputation of specialist/facility Specialist’s affiliation with cancer center Availability of clinical trials at referral site |

Patient’s preference for site of care Distance of site from patient’s home Patient’s ability to pay |

Practice’s affiliation with specialist Personal relationship with specialist Possibility of losing patient to specialist |

| Barnett et al. 2012 |

My patients have good experiences with this physician Physician has good patient rapport Timely availability of appointments Location convenient for patient Patient request Speaks patient’s language |

Quality of communication with me Shares my medical record system Physician refers to me Works in my hospital or practice |

|

| Brown et al. 2013 |

Report cards Technical skill Clinical judgement Post-operative care Risk-adjusted mortality Outcomes other than mortality Effective communication |

Patient satisfaction | Hospital affiliation |

| Gao et al. 2021 |

Patient complexity Surgeon experience and volume GIs would refer a family member to a trusted colorectal surgeon. Surgeons would refer a family member to a large or academic center. |

Preference for care to be received locally Specialist availability Patient preference |

GIs preferred to refer to colorectal surgeons while most general surgeons perform surgery on patients they diagnose Preference to remain in health system |

| Makovkina and Kern 2021 |

Clinical judgement Clinical reputation of physician’s organization |

Geographic preference Ease of scheduling Patient feedback Insurance coverage Patient preference Flexibility in accommodating urgent referrals |

Preference or institutional pressure to refer within organization Cost containment Personal knowledge and trust of specialist Ease of communication and coordination of care Shared EMR |

The most commonly cited factors across studies were personal knowledge of the specialist, desire to remain within a practice or hospital system, and factors related to patient convenience, such as location, scheduling, and preference. When evaluating the highest rated factors across the five studies asking physicians to compare importance, the perceived skill of the specialist as well as prior experiences of the referring provider and their patients was consistently ranked highly across studies (Supplemental Table 3). Notably, insurance acceptance or financial considerations were only mentioned in four studies23,44,46,49. Insurance acceptance had moderate importance in the studies where it was mentioned, but it did not rank among the five factors with the highest rating in any study.

The factors cited in the survey studies were echoed in the interview studies of referring physicians. Example quotations can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Example Quotations from Interviews with Referring Physicians

| Theme | Referring provider type | Specialist type | Example quotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical expertise | Gastroenterologist | Surgeon | “One, I make sure that they are board certified in colorectal surgery. And I also, kind of, see where they had their training. And then, the third, how long they’ve been practicing. I have no idea how many [rectal cancer surgeries the surgeons I refer to] do in a year.” |

| Clinical expertise | Gastroenterologist | Surgeon | “I just accept the premise that if they’re performing surgeries at a tertiary center such as [X], they’ve been vetted and they’re able to do that, and they belong there.” |

| Communication | Primary care physician | Not specified | “If it’s somebody who I’m particularly concerned about or has something a little bit more complicated ... it’s easy for me to pick up the phone or when I see him next say, “Hey, that patient, you know, this is what I want you to be thinking about.” So there is ... definitely something to be said about knowing the people that you’re working with.” |

| Personal knowledge/relationships | Primary care physician | Not specified | “I may try to move [patients] to somebody that I trust, um, and know rather than the person they may have seen before ... because then I’ll be able to trust the judgment of the person that I’ve chosen.” |

| Personal knowledge/relationships | Primary care physician | Not specified | “If I happen to know the particular personality of the specialist and I think that that might not be a great fit for a particular family, I might send them to someone else in the group or even possibly to a different practice based on that as well.” |

| Hospital/practice affiliation | Gastroenterologist | Surgeon | “The networks are so integrated that there is this – you know, there is a lot of pressure on the referral patterns, which, you know– which are dictated by the system that you’re working for or working with.” |

| Hospital/practice affiliation | Primary care physician | Not specified | “I think we’re also encouraged as primary care doctors to refer within [the PO] to support our own institution and its, um, you know, revenue. So I think we do get ... I won’t say pressure, but recommendations from our leadership that it’s preferable for us to refer within [the PO].” |

| Location | Primary care physician | Not specified | “If someone is here, is in our office at our location, which is convenient ... most of our patients [who] are coming to us work or live nearby, so usually by default this location [where patients can also see specialists] is convenient for them.” |

| Insurance acceptance | Primary care physician | Not specified | “Well, what I mean is that the [PO] specialists ... the group of insurances that they cover is pretty much ... similar to the group of insurances that we cover.... [It] is very rare that I send somebody to a [PO] doctor and I take their insurance but it turns out that a [PO] doctor does not take their insurance.” |

DISCUSSION

Referring providers consider several related factors when selecting specialists for care. Of the five studies that ranked the relative importance of different factors, referring providers consistently placed a high value on their prior experiences, their ability to communicate with the specialist, and the specialist’s clinical skill. These factors were echoed by statements provided by referring providers in interviews. In addition to clinical skill, relational factors, such as rapport and ease of communication, were commonly cited across studies. The decision process when making referrals highlights the high value of trust and relationships among primary providers, specialists, and patients.

Across all studies, referring providers reported that clinical expertise and skill were among the most important factors when selecting a referral destination for their patients. None of the studies commented on how the referring providers assessed the clinical and technical skills of their consultants. One might speculate that referring providers gauge a consultant’s skill based on clinically objective outcome measures. However, in one study examining the impact of outcomes data on referral decisions, Brown et al. showed that cardiologists do not consider cardiac surgery report cards documenting risk-adjusted morbidity and mortality statistics to have high importance or influence47. Notably, 71% had not discussed the report cards with a single patient in the preceding year.

These findings support voiced concerns regarding potential methodological flaws in other publicly available sources of surgeon-specific data50,51. For example, websites to aid in physician selection, such as Physician Compare, report training history and board certification but not case volume or patient outcomes52. The absence of trusted objective data on a specialist’s quality forces physicians to rely on reputation as a proxy for quality despite the poor correlation between the two constructs53–57. For example, subjective assessments of hospital reputation are poorly correlated with measured patient outcomes with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient of 0.0356. A surgeon’s reputation among physicians similarly does not predict risk-adjusted mortality53. Online physician reviews are often not correlated with individual physician’s measured outcomes55,57 or validated measures of patient satisfaction54.

Our synthesis of the existing literature highlights the subjective nature of the referral process and the importance of the referring doctors’ experiences when making recommendations to patients. However, some referring providers may lack access to the interpersonal experiences or professional networks to offer their patients high-quality specialists58. For example, one survey showed that primary care physicians who more often treat Black patients are more likely to report lacking access to high-quality specialists59. Additionally, network analysis of claims data shows that referral patterns differ for Black and White patients with Black patients seeing fewer specialists than White patients60. These data suggest that referral patterns reflect the broader economic and social context in which patients receive care. Important factors like geographic location, affiliation with a larger health system, patient income, and insurance status may all contribute to the observed disparities in both referral practices and outcomes. Facilitating access to and awareness of higher quality specialists and hospitals may therefore represent an opportunity to mitigate observed disparities in care.

Restrictive insurance networks may be a second important consideration that limits access to specialists. Insurance acceptance was only discussed in four studies as an important factor influencing referral choice. Compared to clinical skill, prior experiences, and communication, insurance-related concerns appeared relatively less important to referring providers. It is possible, however, that referring providers may limit their set of possible specialists to those within their own institution or physician’s organization, as illustrated by Makovkina and Kern49. Referring providers may thus share a common set of insurance networks with the specialists to whom they frequently refer patients, which may explain the limited influence of insurance as a factor in the studies reviewed.

Our analysis shows the importance of professional networks and convenience in the selection of specialists, as well as the relative underuse of objective data related to provider-specific outcomes. Due to the importance and high frequency of referrals for primary care providers, skills related to referrals have been recognized as an Entrustable Professional Activity for trainees in internal medicine61, family medicine62, and pediatrics63. Physicians only receive training on when to consult a specialist and how to communicate about mutual patients. However, there is little to no formal training and a lack of guidelines on how to select the best available specialist35,64. A high patient load and the relative rarity of some surgical diagnoses among primary care patients may hinder the ability of a referring provider to maintain a network of strong specialists.

Future studies should move beyond surveys of referring providers to leverage mixed-method techniques to measure the impact of incorporating quantitative data on patient outcomes or specialty-specific performance metrics 65 into the referral process. For example, referring providers can be given patient outcomes from the specialists in their referral network to help them consider options for future referrals, measuring the relative influence of outcomes data on future referral actions. These studies would move the field towards better understanding which decision factors can be modified to facilitate selection of the optimal specialist.

Our study has several limitations. First, this systematic review was limited by the small body of published literature on decision-making in the referral process, precluding a quantitative synthesis of the data. However, our qualitative synthesis incorporates information from a large number of referring providers across seven studies. Given the representation of a limited range of referring provider specialties, the strategies for making referrals may not generalize across specialties. For example, an internist may rely more heavily on personal relationships for referrals to medical specialists than to surgeons given their common training pathway.

Second, all included studies relied on self-reported factors that are considered in the referral process. It is possible that these studies mismeasure referring provider actions if the self-reported reason for choosing a specialist differs from the actual reason. For example, social desirability bias may lead a referring provider to report that they primarily refer based on clinical skill when they actually refer based on personal relationships. Notably, only two studies discussed in detail the role of the health system in the referral process48,49. There may be tension between the desire to refer patients to the highest quality specialist and institutional pressure to keep patients within their own health system, especially for highly reimbursed surgical procedures.

Our study highlights the need for an objective framework to assess the quality of all specialist referrals, guidelines to inform specialist choice, and training to assist new physicians in building a robust referral network. The referral process itself may present an opportunity to reduce healthcare-related disparities for patients and providers. According to our findings, the availability of objective data on specialist outcomes may need to be paired with resources for referring providers to easily identify the specialist best suited to their patient’s needs and for patients to overcome inequitable access to care.

Supplementary Information

(PDF 507 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to recognize and thank Drs. Christopher B. Forrest, Bruce E. Landon, and Michael L. Barnett for providing previously unpublished data.

Funding

Dr. Finn receives grant support from the National Institutes of Health T32 Training Program, 5T32CA251063-02. Dr. Wachtel receives grant support from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, #KL2-TR001879. Dr. Guerra receives grant support from the National Cancer Institute, P30CA016520.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Yahanda AT, Lafaro KJ, Spolverato G, Pawlik TM. A Systematic Review of the Factors that Patients Use to Choose their Surgeon. World J Surg. 2016;40(1):45–55. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-3246-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson CT, Woloshin S, Schwartz LM. Choosing Where to Have Major Surgery: Who Makes the Decision? Arch Surg. 2007;142(3):242–246. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.3.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freedman RA, Kouri EM, West DW, Keating NL. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Patients’ Selection of Surgeons and Hospitals for Breast Cancer Surgery. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(2):222–230. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlin CS, Kralewski J, Savage M. Sources of information used in selection of surgeons. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(8):e293–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birkmeyer MDJD, Siewers MPHAE, Finlayson MDEVA, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(15):1128–1137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finlayson EVA, Goodney PP, Birkmeyer JD. Hospital Volume and Operative Mortality in Cancer Surgery: A National Study. Arch Surg. 2003;138(7):721–725. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.7.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chowdhury MM, Dagash H, Pierro A, Chowdhury MMM. Systematic review A systematic review of the impact of volume of surgery and specialization on patient outcome. Br J Surg. 2007;94(2):145–61. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urbach DR. Pledging to Eliminate Low-Volume Surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(15):1388–1390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1508472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheetz KH, Chhabra KR, Smith ME, Dimick JB, Nathan H. Association of Discretionary Hospital Volume Standards for High-risk Cancer Surgery with Patient Outcomes and Access, 2005-2016. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(11):1005–1012. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.3017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finks JF, Osborne NH, Birkmeyer JD. Trends in Hospital Volume and Operative Mortality for High-Risk Surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(22):2128–2137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1010705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudley RA, Johansen KL, Brand R, Rennie DJ, Milstein A. Selective Referral to High-Volume HospitalsEstimating Potentially Avoidable Deaths. JAMA. 2000;283(9):1159–1166. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.9.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salemi A, Sedrakyan A, Mao J, et al. Individual Operator Experience and Outcomes in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC: Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12(1):90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dewey TM, Herbert MA, Ryan WH, et al. Influence of Surgeon Volume on Outcomes With Aortic Valve Replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93(4):1107–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Physician volume, specialty, and outcomes of care for patients with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(5):890–897. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kleiman NS, Welt FGP, Truesdell AG, et al. Should Interventional Cardiologists Super-Subspecialize?: Moving From Patient Selection to Operator Selection. JACC: Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14(1):97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keswani RN, Qumseya BJ, O’Dwyer LC, Wani S. Association Between Endoscopist and Center Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Volume With Procedure Success and Adverse Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol: the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2017;15(12):1866–1875.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malik AT, Jain N, Scharschmidt TJ, Li M, Glassman AH, Khan SN. Does Surgeon Volume Affect Outcomes Following Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty? A Systematic Review. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33(10):3329–3342. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aquina CT, Probst CP, Kelly KN, et al. The pitfalls of inguinal herniorrhaphy: Surgeon volume matters. Surgery. 2015;158(3):736–746. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aquina CT, Kelly KN, Probst CP, et al. Surgeon volume plays a significant role in outcomes and cost following open incisional hernia repair. J Gastrointest Surg: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2015;19(1):100–110. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2627-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith MD, Patterson E, Wahed AS, et al. Relationship between surgeon volume and adverse outcomes after RYGB in Longitudinal Assessment of Bariatric Surgery (LABS) study. Surg Obes Relat Dis: official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2010;6(2):118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouchard P, Demyttenaere S, Court O, Franco EL, Andalib A. Surgeon and hospital volume outcomes in bariatric surgery: a population-level study. Surg Obes Relat Dis: official journal of the American Society for Bariatric Surgery. 2020;16(5):674–681. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2020.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Starfield B, Forrest CB, Nutting PA, von Schrader S. Variability in physician referral decisions. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15(6):473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forrest CB, Nutting PA, Starfield B, von Schrader S. Family physicians’ referral decisions. J Fam Pract. 2002;51(3):215–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epstein AJ, Gray BH, Schlesinger M. Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Use of High-Volume Hospitals and Surgeons. Arch Surg. 2010;145(2):179–186. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu JH, Zingmond DS, McGory ML, et al. Disparities in the Utilization of High-Volume Hospitals for Complex Surgery. JAMA. 2006;296(16):1973–1980. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.16.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang LC, Ma Y, Ngo J. v, Rhoads KF. What factors influence minority use of National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers? Cancer. 2014;120(3):399–407. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boudourakis LD, Wang TS, Roman SA, Desai R, Sosa JA. Evolution of the Surgeon-Volume, Patient-Outcome Relationship. Ann Surg. 2009;250(1):159–65. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181a77cb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dimick J, Ruhter J, Sarrazin MV, Birkmeyer JD. Black patients more likely than whites to undergo surgery at low-quality hospitals in segregated regions. Health Affairs. 2013;32(6):1046–1053. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reichman M. Optimizing Referrals & Consults With a Standardized Process. Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14(10):38–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org. Accessed July 27, 2021.

- 31.Page MJ, Mckenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in EpidemiologyA Proposal for Reporting. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018). CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist. [online] Available at: https://casp-uk.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf. Accessed: 8/3/2021.

- 34.Stern C, Lizarondo L, Carrier J, et al. Methodological guidance for the conduct of mixed methods systematic reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2108–2118. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choudhry NK, Liao JM, Detsky AS. Selecting a Specialist: Adding Evidence to the Clinical Practice of Making Referrals. JAMA. 2014;312(18):1861–1862. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.12963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langberg K, Solad YV, Teslya P, Chowdhury M, Aslanian HR. Tu1030 Primary Care Physician’s Perception of Colonoscopy Quality Measures and Their Influence on Colonoscopy Referral Patterns. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(5):AB537. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.03.1091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schreiner A, Zhang J, Mauldin PD, Moran WP. Specialty referrals: A case of who you know versus what you know? J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(2):S402–S403. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wood ME, Flynn BS, Stockdale A. Primary care physician management, referral, and relations with specialists concerning patients at risk for cancer due to family history. Public Health Genomics. 2013;16(3):75–82. doi: 10.1159/000343790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mukamel DB, Weimer DL, Zwanziger J, Gorthy SFH, Mushlin AI. Quality Report Cards, Selection of Cardiac Surgeons, and Racial Disparities: A Study of the Publication of the New York State Cardiac Surgery Reports. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing. 2004;41(4):435–446. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_41.4.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schreiner AD, Holmes-Maybank KT, Zhang J, Marsden J, Mauldin PD, Moran WP. Specialty Physician Designation in Referrals from a Vertically Integrated PCMH. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol. 2019;6:2333392819850389–2333392819850389. doi: 10.1177/2333392819850389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jain A, Hermiz S, Suliman A, Herrera FA. Hand Surgery Referral Pattern Preferences Among Primary Care Physicians in Academic Centers in the Southeastern United States. Ann Plast Surg. 2020;85(6):622–625. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000002549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kinchen KS, Cooper LA, Wang NY, Levine D, Powe NR. The Impact of International Medical Graduate Status on Primary Care Physicians’ Choice of Specialist. Medical Care. 2004;42(8):747–55. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000132352.06741.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Forrest CB, Nutting PA, von Schrader S, Rohde C, Starfield B. Primary Care Physician Specialty Referral Decision Making: Patient, Physician, and Health Care System Determinants. Med Decis Making. 2006;26(1):76–85. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05284110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kinchen KS, Cooper LA, Levine D, Wang NY, Powe NR. Referral of Patients to Specialists: Factors Affecting Choice of Specialist by Primary Care Physicians. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(3):245. doi: 10.1370/afm.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barnett ML, Keating NL, Christakis NA, James O’malley A, Landon BE. Reasons for Choice of Referral Physician Among Primary Care and Specialist Physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;27(5):506–512. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1861-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Abel GA, Friese CR, Neville BA, et al. Referrals for suspected hematologic malignancy: a survey of primary care physicians. Am J Hematol. 2012;87(6):634–636. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown DL, Epstein AM, Schneider EC. Influence of Cardiac Surgeon Report Cards on Patient Referral by Cardiologists in New York State After 20 Years of Public Reporting. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(6):643–648. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao X, Weeks KS, Gribovskaja-Rupp I, Hassan I, Ward MM, Charlton ME. Provider Viewpoints in the Management and Referral of Rectal Cancer. J Surg Res. 2021;258:370–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.08.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Makovkina E, Kern LM. Understanding How Providers and Staff Make Decisions About Where to Refer Their Patients: A Qualitative Study. J Ambul Care Manage. 2021;44(1):21–30. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xu LW, Li A, Swinney C, et al. An assessment of data and methodology of online surgeon scorecards. J Neurosurg Spine SPI. 2017;26(2):235–242. doi: 10.3171/2016.7.SPINE16183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ban KA, Cohen ME, Ko CY, et al. Evaluation of the ProPublica Surgeon Scorecard “Adjusted Complication Rate” Measure Specifications. Ann Surg. 2016;264(4):566–74. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Physician Compare. Available at https://www.medicare.gov/care-compare/. Accessed August 19, 2021.

- 53.Hartz AJ, Pulido JS, Kuhn EM. Are the best coronary artery bypass surgeons identified by physician surveys? Am J Public Health. 1997;87(10):1645–1648. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.10.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen J, Presson A, Zhang C, Ray D, Finlayson S, Glasgow R. Online physician review websites poorly correlate to a validated metric of patient satisfaction. J Surg Res. 2018;227:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Daskivich TJ, Houman J, Fuller G, Black JT, Kim HL, Spiegel B. Online physician ratings fail to predict actual performance on measures of quality, value, and peer review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018;25(4):401–407. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocx083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sehgal AR. The role of reputation in U.S. News & World Report’s rankings of the top 50 American hospitals. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(8):521–525. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-8-201004200-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trehan SK, Nguyen JT, Marx R, et al. Online Patient Ratings Are Not Correlated with Total Knee Replacement Surgeon–Specific Outcomes. HSS J. 2018;14(2):177–180. doi: 10.1007/s11420-017-9600-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hollingsworth JM, Funk RJ, Garrison SA, et al. Differences Between Physician Social Networks for Cardiac Surgery Serving Communities With High Versus Low Proportions of Black Residents. Med Care. 2015;53(2):160–7. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL. Primary Care Physicians Who Treat Blacks and Whites. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(6):575–584. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa040609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Landon BE, Onnela JP, Meneades L, O’Malley AJ, Keating NL. Assessment of Racial Disparities in Primary Care Physician Specialty Referrals. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2029238–e2029238. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hauer KE, Kohlwes J, Cornett P, et al. Identifying entrustable professional activities in internal medicine training. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(1):54–59. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00060.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors. Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs). Resources. Available at https://www.afmrd.org/page/epa. Accessed August 19, 2021.

- 63.Hamburger EK, Lane JL, Agrawal D, et al. The Referral and Consultation Entrustable Professional Activity: Defining the Components in Order to Develop a Curriculum for Pediatric Residents. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(1):5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Slavin MJ, Rajan M, Kern LM. Internal medicine residents identify gaps in medical education on outpatient referrals. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):243. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02177-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krumholz HM, Brass LM, Every NR, et al. Measuring and Improving Quality of Care. Circulation. 2000;101(12):1483–1493. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.12.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 507 kb)