Abstract

We have formulated a numerical model that simulates the accumulation of green fluorescent protein (GFP) in bacterial cells from a generic promoter-gfp fusion. The model takes into account the activity of the promoter, the time it takes GFP to mature into its fluorescent form, the susceptibility of GFP to proteolytic degradation, and the growth rate of the bacteria. From the model, we derived a simple formula with which promoter activity can be inferred easily and quantitatively from actual measurements of GFP fluorescence in growing bacterial cultures. To test the usefulness of the formula, we determined the activity of the LacI-repressible promoter PA1/O4/O3 in response to increasing concentrations of the inducer IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) and were able to predict cooperativity between the LacI repressors on each of the two operator sites within PA1/O4/O3. Aided by the model, we also quantified the proteolytic degradation of GFP[AAV], GFP[ASV], and GFP[LVA], which are popular variants of GFP with reduced stability in bacteria. Best described by Michaelis-Menten kinetics, the rate at which these variants were degraded was a function of the activity of the promoter that drives their synthesis: a weak promoter yielded proportionally less GFP fluorescence than a strong one. The degree of disproportionality is species dependent: the effect was more pronounced in Erwinia herbicola than in Escherichia coli. This phenomenon has important implications for the interpretation of fluorescence from bacterial reporters based on these GFP variants. The model furthermore predicted a significant effect of growth rate on the GFP content of individual bacteria, which if not accounted for might lead to misinterpretation of GFP data. In practice, our model will be helpful for prior testing of different combinations of promoter-gfp fusions that best fit the application of a particular bacterial reporter strain, and also for the interpretation of actual GFP fluorescence data that are obtained with that reporter.

Green fluorescent protein (GFP) has become a popular reporter for gene activity in bacteria. In this capacity, it is generally being used in one of two ways: either to establish the conditional expression of a gene in response to a specific substance, growth condition, or habitat (5, 6, 15, 21, 23, 40, 45, 48) or to analyze a sample or habitat for a substance or condition to which a particular gene is known to be responsive (3, 8, 10, 16, 17, 22, 26, 35). In both cases, the assessment of whether or not a particular gene or its promoter is responsive is based on the comparison of GFP fluorescence in cells from two populations: for example, one grown in the presence of a substance and the other grown in its absence or one grown in vivo compared to the other in vitro.

The experimental set-up usually dictates the method by which GFP fluorescence is quantified. Cell suspensions or culture aliquots are commonly analyzed by fluorimetry. Fluorescence measured this way is normalized for the number of cells in the sample to obtain an average fluorescence per cell, which can then be compared to that of other cell suspensions. Using fluorescent flow cytometry or image cytometry, which are more sensitive methods, it is possible to measure GFP fluorescence emitted from individual bacteria. Such approaches become necessary when cells have to be analyzed directly in situ, e.g., to establish habitat-specific gene expression (46), when cells are so few that their combined fluorescence drops below the detection capacity of a fluorimeter, or when it is anticipated that the bacterial population under investigation is divided into subpopulations that are exposed to different conditions (26). Single-cell GFP contents are often represented in histograms or normal probability plots, which offer the advantage of instant appreciation for the variation among cells within the same population and present a convenient way of comparing GFP content in cells from different populations.

Ideally, the output of a reporter protein should reflect as closely as possible the activity of the promoter that drives its expression. GFP fluorescence has been validated as a reporter output by direct comparison to more traditional reporter proteins such as β-galactosidase (28, 39) and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (1). Still, two properties that are unique to GFP have been recognized as less desirable when trying to infer promoter activity from fluorescence measurements. First, newly synthesized GFP must undergo a series of self-modifications in order to become fluorescent (44). The rate-limiting step in this maturation process requires oxygen and occurs with pseudo-first-order kinetics (18), which means for the wild-type GFP from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria (11) that the appearance of fluorescence lags some 3.5 h behind the actual synthesis of the protein (2). Second, GFP is unusually resistant to proteolysis (44), with a half-life time reported as >1 day in vivo (4). This means that once made, GFP will persist in a cell even after the promoter that drives its expression is shut down. Both these properties have been addressed by the creation of GFP variants such as enhanced GFP (EGFP) (34) and GFPmut3 (12), which have significantly reduced maturation times, and unstable variants GFP[ASV], GFP[AAV], and GFP[LVA] (4), which were engineered to become susceptible to degradation by ClpXP-type proteases (14, 24).

With the need for GFP variants such as those described above comes the realization that promoter activity is not the only factor governing a cell's GFP content. Conversely, a shift in GFP content is not necessarily indicative of a change in promoter activity. For example, a decrease in protease activity may well cause an accumulation of GFP in bacterial reporter cells, which in turn could easily be misinterpreted as an increase in promoter activity. Another important factor to consider is growth rate: the faster cells divide, the faster GFP is diluted. Therefore, growth rate should be expected to have a considerable impact on GFP content. It was mentioned, for example, that Pseudoalteromonas cells expressing GFP appeared dimmer on rich medium than on minimal medium (42).

We set out to understand how exactly promoter activity, maturation rate, proteolytic degradation, and cell division rate in combination determine GFP content. Our approach was based on the formulation of a structured numerical model that describes the accumulation of fluorescent GFP from a promoter-gfp fusion in a single bacterial cell. The model proved to be very useful by providing us with a set of formulas that made it possible to extract parameter values from actual fluorescence measurements. These parameters then allowed us to accurately predict and interpret the accumulation of fluorescent GFP, both in bacterial cultures and in individual bacterial cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, culture conditions, and promoter-gfp constructs.

Escherichia coli DH5α (38) and Erwinia herbicola 299R (9) were grown aerobically in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or M9 minimal medium (38) supplemented with 0.2% Casamino Acids (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) plus 0.4% galactose or fructose. Where appropriate, kanamycin (Km) and tetracycline (Tc) were added at final concentrations of 50 and 15 μg/ml, respectively.

Plasmid pJBA28 (4) contains a mini-Tn5-Km cassette (13) that encompasses a fusion of the LacI-repressible promoter PA1/O4/O3 (Bujard laboratory, unpublished) (also referred to as PA1lacO-1 in reference 29) to an S2R-modified version of the gfpmut3 gene (12). Plasmids pJBA116, pJBA118, and pJBA120 (4) differ from pJBA28 in that they carry gfp[AAV], gfp[ASV], and gfp[LVA], respectively, which code for unstable variants of GFPmut3. The PA1/O4/O3-gfp fusions were inserted as mini-Tn5 cassettes on the chromosome of E. herbicola 299R by triparental mating with donor strain E. coli MV1190(λ-pir) (19) and helper E. coli DH5α(pRK2073) (7). Each of the resulting strains of 299R was then transformed with plasmid pCPP39 (D. Bauer, unpublished), which confers resistance to Tc and harbors the lacIq gene (32) for control of PA1/O4/O3 activity by isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Plasmids pPfruB-gfp[tagless], pPfruB- gfp[AAV], pPfruB-gfp[ASV], and pPfruB-gfp[LVA] contain the E. coli DH5α fruB promoter (36) in promoter-probe vectors pPROBE-gfp[tagless], -gfp[AAV], -gfp[ASV], and -gfp[LVA], respectively (31). Plasmid pPfruB-gfp[AAV] has been described elsewhere (26) and expresses an unstable variant of EGFP (18) in response to fructose. Plasmids pPfruB-gfp[tagless], -gfp[ASV], and -gfp[LVA] are identical to pPfruB-gfp[AAV] except for the stability of the GFP that they express.

Determination of culture growth and GFP fluorescence in bacterial cultures and in individual cells.

Bacterial growth was followed as optical density (OD) at 600 nm using a Perkin-Elmer Lambda 3A UV/VIS spectrophotometer (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.). GFP fluorescence in bacterial cultures was determined in a Perkin-Elmer LS50B luminescence spectrometer that was set at an excitation wavelength of 490 nm and an emission wavelength of 510 nm (with a slit width of 8 nm in both cases). GFP content of individual cells was determined as described previously (26) by epifluorescence microscopy on a Zeiss Axiophot microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and quantitative image analysis using IPLab software (Scanalytics, Fairfax, Va.).

Simulations and best-fit procedures.

All simulations of the model were performed with Gepasi software version 3.21 (30) or in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Wash.). The response of the PA1/O4/O3 promoter to different concentrations of IPTG was fitted to the Hill equation using GraphPad Prism version 3.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif.).

RESULTS

Formulation of a model for GFP accumulation in single bacterial cells.

We formulated a structured model that is similar to but differs in important ways from the one described by Subramanian and Srienc for GFP accumulation in transfected mammalian cells (43). Consider a bacterial cell that harbors a gene for GFP fused to promoter P. Its fluorescent GFP content (fGFP) will depend on the rate at which nonfluorescent GFP (nGFP) is synthesized from P, on the rate of maturation from nGFP to fGFP, on the growth rate of the bacterium, and on the rate with which both nGFP and fGFP are degraded by proteases (Fig. 1). Changes in nGFP and fGFP over time can be expressed as follows:

|

1 |

and

|

2 |

in which n is nGFP content (nGFP per cell), t is time (hours), P is promoter activity (nGFP per cell per hour), m is the maturation constant (per hour), μ is the growth rate (per hour), Dn is the degradation rate of nGFP (nGFP per cell per hour), f is fGFP content (fGFP per cell), and Df is the degradation rate of fGFP (fGFP per cell per hour). Whereas Subramanian and Srienc dissected the output from promoter P into single-component parameters such as transcription initiation rate, mRNA stability, and translation efficiency, we combined the kinetics of transcription and translation into the single value P.

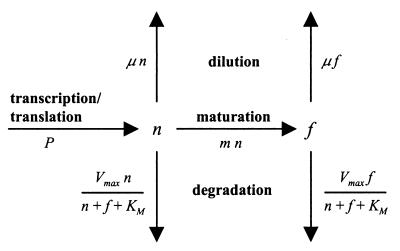

FIG. 1.

Flow diagram showing how a bacterium's fluorescent GFP content (f) is a function of maturation from a pool of nonfluorescent GFP (n), degradation by proteases, and dilution by cell division. The pool of n is depleted by maturation, degradation, and dilution and replenished by transcription and translation from a promoter-gfp fusion.

Maturation can be described as a first-order reaction (18), and constant m can be calculated as ln(2) divided by the time constant of GFP maturation, which has been determined as 2.0 h for wild-type GFP (wtGFP) and 0.45 h for faster-folding S65T mutants such as EGFP (18). For an S65G mutant like GFPmut3, a time constant has not been determined but probably closely resembles that of S65T mutants (44). We further assumed that degradation of GFP obeys Michaelis-Menten kinetics and that the protease responsible for degradation would not discriminate between nGFP and fGFP:

|

3 |

and

|

4 |

in which Dmax represents the maximal proteolytic activity (GFP per cell per hour) and KM represents the combined GFP content per cell (i.e., nGFP + fGFP per cell) at which the sum of Dn and Df equals 1/2 · Dmax.

Others (4, 43) have expressed the degradation of GFP and its unstable variants not in terms of Michaelis-Menten kinetics but instead as a first-order reaction. Under this assumption, the rate of degradation of n and f, i.e., Dn and Df, equals k · n and k · f, respectively, in which k is the rate constant, which amounts to ln(2) divided by the half-life time of the protein. There is a crucial distinction between the two ways of describing GFP degradation that has important implications for how much fluorescent GFP will actually accumulate in a cell. With first-order kinetics, there is no limit on the rate of degradation: the higher n or f, the faster they are degraded. With Michaelis-Menten kinetics, degradation is dependent on the abundance of n and f as well, but there is a limit to the rate of degradation, which is set as Dmax. This Dmax may be thought of as the maximal capacity of the proteases that are present in a bacterial cell. Beyond a certain concentration of GFP, which is determined by the KM value, their combined proteolytic activity is not influenced by further increases in GFP content. Later on (Fig. 4), we will present experimental data that strongly favor the Michaelis-Menten model for degradation of GFP variants such as GFP[ASV], GFP[AAV], and GFP[LVA].

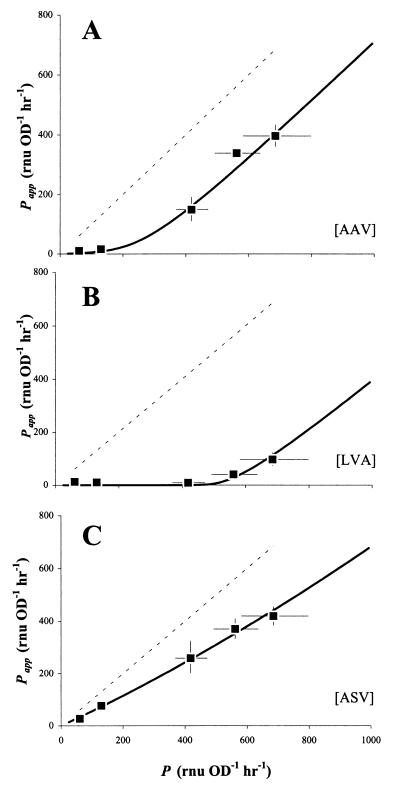

FIG. 4.

Comparison of apparent and true promoter activities (Papp and P, respectively) as a test for the degradation kinetics of unstable variants GFP[AAV] (A), GFP[LVA] (B), and GFP[ASV] (C). Cultures of E. herbicola 299R::PA1/O4/O3-gfp(pCPP39) expressing GFP[AAV], GFP[LVA], or GFP[ASV] were grown in LB in the presence of 80, 160, 320, 640, or 1,280 μM IPTG. From F,OD plots, we determined values for δF/δOD and calculated corresponding apparent values for P from equation 13. These values of Papp were plotted as a function of the corresponding values for true promoter activity P, which were determined from a culture of 299R::PA1/O4/O3-gfp(pCPP39) expressing stable GFP in response to the same concentrations of IPTG. The dashed line represents the reference line Papp = P, whereas the solid lines represent a Gepasi simulation of Papp as a function of P, assuming experimentally determined estimates for Dmax and KM for each of the unstable GFP variants (see Fig. 5 and text).

In steady state, both δn/δt and δf/δt equal zero, so that from equations 1 and 2 it follows that:

|

5 |

and

|

6 |

in which nss, fss, Dnss, and Dfss represent steady-state values for n, f, Dn, and Df, respectively. Equations 5 and 6 can be combined with equations 3 and 4 to eliminate μ, Dnss, Dfss, Dmax, and KM and produce:

|

7 |

and

|

8 |

which describe nss as a function of fss or vice versa. From these equations, it is apparent that the ratio of fluorescent to nonfluorescent GFP in a balanced cell is dependent only on the rate at which nonfluorescent GFP appears and matures, not on the rate of degradation or growth. This implies that if f, P, and m are known, n can be calculated.

Adoption of single-cell model to describe GFP accumulation in bacterial cultures.

With the model we describe above, it is possible to simulate the dynamics of fluorescent GFP expression in a single bacterial cell with the help of a spreadsheet program like Microsoft Excel or a more sophisticated application like Gepasi (30). In these simulations, parameters such as promoter strength, degradation capacity, and growth rate can be changed freely to assess how they affect, individually or in combination, the rates and levels of GFP accumulation. In this and the following sections, we will describe how parameter values for P, Dmax, and KM can be approximated from fluorescence measurements on growing bacterial cultures, and go on to show how these values can be used to accurately predict patterns of GFP accumulation in bacterial individuals or populations.

In practice, the GFP content of a bacterial culture is measured as fluorescence (F, in relative light units [RLU]) and the cell density usually as optical density (OD). If we assume that F is proportional to the amount of fGFP per unit of volume and OD to the number of cells per unit of volume (33), then the quotient F/OD (or cell density-normalized fluorescence, RLU per OD unit) is proportional to the amount of fGFP per cell, i.e., f in the single-cell model above. Similarly, n is proportional to the nonfluorescence (N) of a culture normalized for cell density, i.e., N/OD (relative nonlight units [RNU] per OD unit). This means that the single-cell model can be adopted to predict accumulation of GFP in culture simply by changing units from fGFP or nGFP per cell to RLU or RNU per OD unit. Changes in F and OD can be described as:

|

9 |

and

|

10 |

Combined, these equations result in

|

11 |

This quotient, δF/δOD, is essentially the slope of the tangent line through each point of the curve in a plot of F as a function of OD. Comparison of equations 11 and 6 reveals that δF/δOD equals fss. Since fss is a constant, we predict that the F,OD plot should produce a straight line with slope δF/δOD.

Estimation of promoter activities from experimental GFP fluorescence data using F,OD plots.

Equations 5 and 6 can be combined as:

|

12 |

If GFP is stable and not subject to proteolytic degradation, Dnss and Dfss equal zero, so that equation 12 can be simplified to:

|

13 |

Note how a reduction in μ would cause an increase in fss given a constant value for P. In other words, a cell expressing GFP from a promoter with constant activity will appear brighter if it is growing more slowly. If not corrected for this growth effect, the promoter activity in this cell would be overestimated based on GFP fluorescence alone.

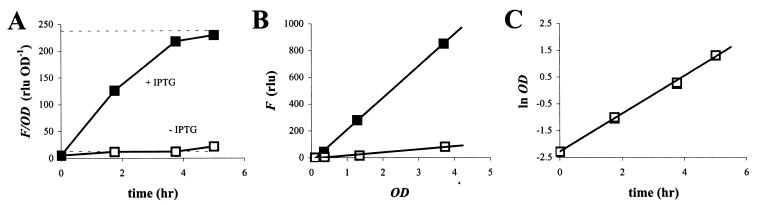

Using formula 13, promoter strength P can be estimated from experimentally determined values for δF/δOD and μ. This is illustrated in Fig. 2 for cultures of E. herbicola 299R::PA1/O4/O3-gfpmut3(pCPP39). This strain harbors a chromosomal fusion of the LacI-repressible promoter PA1/O4/O3 to a gene for GFPmut3. In the absence of IPTG, the culture appeared no more fluorescent (Fig. 2A) than a culture of wt 299R that carried no gfp fusion at all (not shown). This is due to the LacI repressor protein, which is expressed from plasmid pCPP39 and binds to two operator sites, O4 and O3, in the PA1/O4/O3 promoter region (29), thereby preventing transcription of the gfpmut3 gene. In the presence of IPTG, LacI loses its affinity to O4 and O3, which allows transcription to occur. Indeed, we saw GFP fluorescence accumulate steadily towards an apparent plateau (Fig. 2A). As predicted, an F,OD plot of the same data revealed two straight lines (Fig. 2B) with slopes of 238 ± 3 and 12.6 ± 0.4 RLU OD−1 in the presence and absence of IPTG, respectively. Incidentally, these values nicely predicted the apparent steady-state levels for fluorescent GFP content (Fig. 2A, broken horizontal lines), as would be expected since δF/δOD equals fss.

FIG. 2.

Accumulation of GFP fluorescence in cultures of E. herbicola 299R::PA1/O4/O3-gfpmut3(pCPP39) growing on galactose in the presence (solid squares) or absence (open squares) of IPTG. Fluorescence was normalized for cell density and plotted as a function of time (A). Broken horizontal lines indicate steady-state levels of fluorescent GFP that were predicted from the slopes in a corresponding F,OD plot (B). Growth was exponential in both cultures and occurred at the same fast rate (C; open squares largely overlap solid squares).

To calculate the activities of PA1/O4/O3 in the presence and absence of IPTG (P+IPTG and P−IPTG), we first corrected the δF/δOD values for background fluorescence. This was determined as the δF/δOD of a wt E. herbicola 299R culture growing under the same conditions (not shown), and amounted to 11.7 ± 0.2 RLU OD−1. Corrected δF/δOD values were then substituted for fss in equation 13, together with 0.71 ± 0.02 h−1 for growth rate μ (Fig. 2C) and ln(2)/0.45 = 1.54 h−1 for maturation constant m. The values of P+IPTG and P−IPTG thus computed were 235 ± 12 and 1 ± 1 RNU OD−1 h−1, respectively. Note that the units for promoter activity reflect the synthesis rate of immature GFP or nonfluorescence, hence the number of RNU per OD unit per hour. From these values for P, we conclude that the activity of promoter P was induced by a factor of 235 in the presence of IPTG.

This experiment illustrates quite well another reason why it is not always appropriate to interpret GFP content as a quantitative measure of promoter activity. Because it takes the induced cells much longer to achieve steady state than the uninduced cells (Fig. 2A), the time of sampling becomes critical: the data at t = 1.8 h would have suggested an induction factor that is about twofold lower than at t = 3.8 h. Only when steady state is achieved in both cultures would a comparison of GFP content be justified to compare promoter activities. This follows from equation 13: since μ and m are the same for the uninduced and induced cultures, fss+IPTG/fss−IPTG equals P+IPTG/P−IPTG. In some experiments, however, a steady state may never be reached because the culture enters stationary phase long before that. The great advantage of an F,OD plot is that steady state can be predicted before it is established.

Application of the model: quantitative description of the PA1/O4/O3 promoter.

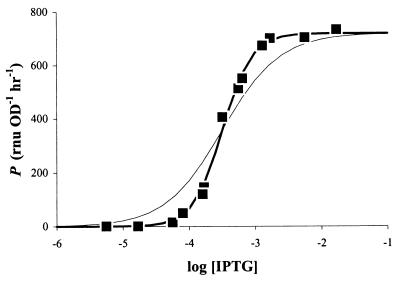

We grew cultures of E. herbicola 299R::PA1/O4/O3-gfpmut3(pCPP39) in the presence of increasing amounts of IPTG and determined in each case a corresponding value for P, as described above. The resulting curve had a sigmoidal shape that is typical of a saturable response (Fig. 3). The range of IPTG concentrations over which PA1/O4/O3 activity could be modulated was quite narrow, between 0.1 and 1 mM. We fitted the observed data points to the Hill equation (20):

|

14 |

in which Pmax is the maximal promoter activity (RNU per OD unit per hour), [IPTG] is the concentration of IPTG in the culture medium (micromolar), h is the Hill coefficient (unitless), and K is the IPTG concentration at which P equals 1/2 · Pmax. The fit (Fig. 3, bold line) revealed that Pmax equaled 720 ± 13 RNU OD−1 h−1 and K = 323 ± 15 μM. We measured P[IPTG]=0 = 1 ± 1 RNU OD−1 h−1, which means that PA1/O4/O3 activity was adjustable over a >720-fold range.

FIG. 3.

Modulation of PA1/O4/O3 activity by IPTG. Cultures of E. herbicola 299R::PA1/O4/O3-gfpmut3(pCPP39) were grown in LB broth supplemented with different concentrations of IPTG (molar). The corresponding promoter activities were plotted as a function of log[IPTG]. The bold line shows the best fit through the data points using the Hill equation (see text for parameters). The thin line represents the same function but with a Hill coefficient of 1.

In E. coli, the same promoter has been shown to be inducible 350-fold (29). Quite to our surprise, we found a value of 2.0 ± 0.1 for the Hill coefficient. This suggests that LacI repressors at the O4 and O3 binding sites act cooperatively in response to IPTG. In the absence of such cooperativity, h would be closer to 1, the dose-response curve would appear flatter (Fig. 3, thin line), and the window for modulation by IPTG would be much wider, i.e., from 10 μM to 10 mM. No cooperativity has been reported for IPTG-induced activation of PA1/O4/O3, so our prediction remains to be verified. This example shows the utility of our approach to obtain accurate and quantitative information on the activity of inducible promoter-gfp fusions.

Accumulation of fluorescence in cultures expressing unstable variants of GFP.

To investigate the effect of GFP stability on the accumulation of fluorescence, we repeated the IPTG induction experiments with cells of E. herbicola 299R::PA1/O4/O3-gfp(pCPP39) that had the gene for stable GFP replaced with that for one of the unstable variants GFP[AAV], GFP[ASV], or GFP[LVA] (4). From the resulting F,OD plots (not shown), we obtained estimates for steady-state fluorescence fss and calculated corresponding values for P using equation 13. Under the assumption that degradation of GFP obeys Michaelis-Menten kinetics, this apparent P, or Papp, is equal to P − Dnss − Dfss · (1 + μ/m) and quantifies how much of promoter activity P actually goes into making fluorescent GFP. The rest, i.e., P − Papp, or Dnss + Dfss · (1 + μ/m), is wasted on proteolytic degradation. This “waste” can also be written as Dnss + Dfss + Dfss · μ/m, or Dmax · (nss + fss + μ · fss/m)/(nss + fss + KM). At high values of P, when GFP content is much larger than the Michaelis-Menten constant (nss + fss ≫ KM), this approximates to Dmax · (nss + fss + μ · fss/m)/(nss + fss), or Dmax · (1 + a · μ/m), in which a is the fraction fss/(nss + fss). As a must lie between 0 and 1, P − Papp amounts to anywhere between Dmax (if a = 0) and (1 + μ/m) · Dmax (if a = 1), and because a tends to change relatively little in the range of high promoter activities, P − Papp is essentially constant. If, on the other hand, the degradation of GFP is a first-order reaction with constant k, then Papp would be equal to P · b/c · (b + m)/(c + m), in which b = μ and c = μ + k. The waste in this case would be equal to P − Papp = P · [1 − b/c · (b + m)/(c + m)], which is not constant but proportional to P.

This difference provides a good test for whether the degradation of unstable GFP in E. herbicola 299R occurs via Michaelis-Menten or first-order kinetics. In the latter case, we would expect that a plot of Papp as a function of P would produce a straight line through the origin and with a slope equal to b/c · (b + m)/(c + m). In the case of Michaelis-Menten kinetics, we instead expect a curve that at higher values of P turns into a line that is more or less parallel to the one described by Papp = P but shifted to the right over a distance of Dmax · (1 + a · μ/m). In Fig. 4, we plotted Papp as a function of P for each of the E. herbicola 299R::PA1/O4/O3-gfp(pCPP39) cultures expressing unstable GFP. Based on the shapes of the curves obtained with GFP[AAV] and GFP[LVA], we reject the hypothesis that the degradation of these variants in strain 299R is a first-order reaction. Instead, the points fall into a pattern that is consistent with the prediction for Michaelis-Menten kinetics.

Comparison of GFP[AAV] and GFP[LVA] suggests that the latter is more susceptible to proteolytic activity, as the data points are shifted to the right over a greater distance. Interestingly, the results we obtained with the GFP[ASV] variant could actually be explained with first-order kinetics: a best-fit line through the data points indicates a slope of 0.63, which corresponds to k = 0.29 h−1, or a half-life of 2.4 h. This is close to the half-life value of 110 min estimated for GFP[ASV] in E. coli (4). However, we must assume that this variant too is degraded according to Michaelis-Menten kinetics. The flatness of the curve simply indicates that GFP[ASV] is more resistant to protease degradation than GFP[AAV] and GFP[LVA] and that the degradation of this variant is not yet saturated at the promoter activities that were tested here.

Estimation of parameters that determine the proteolytic degradation of unstable GFP variants.

The F,OD plot of a culture expressing unstable GFP from a promoter with known activity P can be used to derive steady-state values for Dn and Df, which can then be used to estimate Dmax and KM for the unstable variant, as follows. First, slope δF/δOD supplies the value for fss, which is used to calculate nss using equation 7. Next, Dnss and Dfss are obtained from equations 5 and 6. By combination of equations 3 and 4, it follows that during steady state:

|

15 |

which is essentially a Michaelis-Menten equation that describes the sum of Dnss and Dfss as a function of the sum of nss and fss. This equation can be transformed into a Lineweaver-Burk equation:

|

16 |

A plot of 1/(Dnss + Dfss) versus 1/(nss + fss) should yield a line with a slope of KM/Dmax and a vertical intercept of 1/Dmax. From the slope and intercept, values for Dmax and KM can be computed. However, it should be noted that a single value of P yields only one value of nss, fss, Dnss, and Dfss, i.e., only one value for 1/(Dnss + Dfss) and one for 1/(nss + fss), which together produce a single point, not a line, on the Lineweaver-Burk plot. To obtain more points, promoter activity P will have to be varied to produce for each value P a set of cognate values for nss, fss, Dnss, and Dfss.

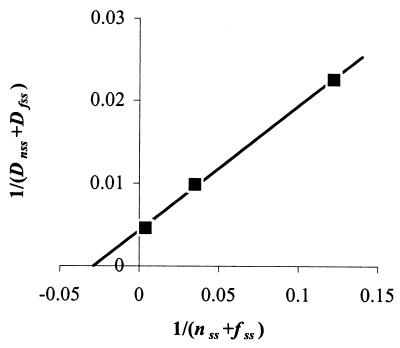

We applied this theory to F,OD plots from E. herbicola 299R cultures that expressed unstable GFP[ASV], GFP[AAV], or GFP[LVA] from the IPTG-modulated promoter PA1/O4/O3. Figure 5 shows, as an example, the Lineweaver-Burk plot that was obtained for 299R::PA1/O4/O3-gfp[AAV](pCPP39). The three points in the plot represent the three cultures of this strain that were grown in the presence of 80, 160, or 320 μM IPTG. From slope KM/Dmax = 1.50 ± 0.05 · 10−1 and intercept 1/Dmax = 4.31 ± 0.36 · 10−3 of the straight line through all three points, we computed Dmax = 232 RNU (or RLU) OD−1 h−1, and KM = 35 RNU (or RLU) OD−1. Similarly, we found Dmax = 490 and KM = 2 for GFP[LVA], and Dmax = 592 and KM = 1.50 · 103 for GFP[ASV] (not shown). These values were used to simulate, using Gepasi software, Papp as a function of P for each of the unstable GFP variants. These simulations are drawn in Fig. 4 as solid lines and fit the observed data as expected.

FIG. 5.

Lineweaver-Burk plot to extract values for Dmax and KM that determine GFP[AAV] degradation in E. herbicola 299R. Cultures of 299R::PA1/O4/O3-gfp[AAV](pCPP39) were grown in LB in the presence of 80, 160, or 320 μM IPTG. From F,OD plots, we determined δF/δOD values of 1.7, 7.71, and 128 RLU OD−1 h−1, respectively. These were substituted for fss in equation 8, together with the respective values for P from Fig. 3, to calculate nss. From equations 5 and 6, we then calculated cognate values for Dnss and Dfss, substituting μ with observed values of 0.69, 0.69, and 0.73 h−1, respectively. The inverse of the sum of nss and fss was plotted as a function of the inverse of (Dnss + Dfss) to produce this graph. From the best fit through the data points, Dmax was calculated as 232 RNU (or RLU) OD−1 h−1, and KM as 35 RNU (or RLU) OD−1. The Dmax and KM parameters for GFP[ASV] and GFP[LVA] were determined the same way using strains 299R::PA1/O4/O3-gfp[ASV](pCPP39) and 299R::PA1/O4/O3-gfp[LVA](pCPP39), respectively.

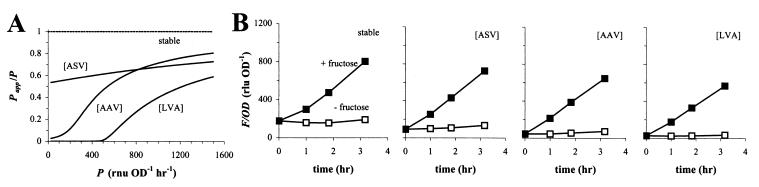

Instead of plotting simulations of Papp as a function of P, we can also plot Papp/P as a function of P (Fig. 6A). The quotient Papp/P expresses the “effective” promoter activity as a fraction of P, whereas 1 − Papp/P denotes the fraction of P lost to proteolytic degradation. From the left-to-right upward trend of all curves in Fig. 6A, it follows that weak promoters in 299R lose a proportionally larger fraction of their activity to degradation than stronger promoters. This effect of disproportional reduction is most evident with GFP[AAV] and GFP[LVA] and has interesting consequences for any promoter fusion that is inducible. It means that an x-fold induction in promoter activity results in an increase in GFP fluorescence that would be greater than x-fold. For example, while a shift in IPTG concentration from 80 to 320 μM raised the activity of PA1/O4/O3 in 299R::PA1/O4/O3-gfp[AAV](pCPP39) approximately 8-fold from 50 to 406 RNU OD−1 h−1, steady-state levels of normalized fluorescence increased from 2 to 128 RLU OD−1, i.e., 64-fold. We observed this effect also with another promoter, PfruB. The activity of PfruB in 299R is induced approximately 7-fold from 168 ± 46 RNU OD−1 h−1 during growth on galactose (from two independent growth experiments) to 1.16 ± 0.22 · 103 RNU OD−1 h−1 on fructose (from two independent growth experiments). Yet cells expressing GFP[AAV] and GFP[ASV] were more than 7-fold brighter on fructose than on galactose (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

Combined effect of promoter strength and GFP stability on the accumulation of fluorescence in E. herbicola 299R. (A) Using Gepasi, we simulated steady-state levels of fluorescent GFP for a range of promoter strengths and determined the corresponding apparent promoter activities (see text for details). For the simulations, we assumed experimentally observed values for growth rate μ of 0.65 to 0.67 h−1, and for m we used a value of 1.54 h−1. Shown is a plot of Papp/P as a function of P. (B) Cell density-normalized fluorescence in cultures of 299R carrying pPfruB-gfp[tagless], -gfp[ASV], -gfp[AAV], or -gfp[LVA] grown on fructose (solid squares) or galactose (open squares). Galactose-grown cells in mid-exponential phase were transferred to fresh medium with fructose or galactose at t = 0 h.

From corresponding F,OD plots (not shown), we estimated steady-state fluorescence levels for GFP[AAV] as 10 to 12 times higher on fructose than on galactose and for GFP[LVA] even 20 to 25 times higher. In contrast, cells expressing GFP[ASV] were only six to eight times brighter on fructose than on galactose, comparable to cells expressing stable GFP (Fig. 6B). This is as expected from the relatively flat line for GFP[ASV] in Fig. 6A, which indicates that accumulation of this variant is much less a function of promoter activity, as is the case for GFP[AAV] and GFP[LVA].

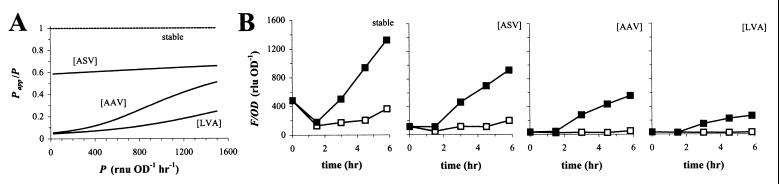

To assess whether the dynamics of GFP degradation are species specific, we also prepared a Papp/P versus P plot for strain E. coli DH5α (Fig. 7A). Comparison to Fig. 6A revealed clear differences with E. herbicola 299R. The curves for GFP[AAV] and GFP[ASV] appeared lower in DH5α, suggesting that the difference between DH5α cells expressing these variants and stable GFP would be greater than for 299R cells. Also, the flatness of the curves for variants GFP[AAV] and GFP[ASV] suggests a less pronounced effect of disproportional reduction for these variants, especially for GFP[ASV]. In DH5α, the fruB promoter is expressed at a rate of 867 RNU OD−1 h−1 during growth on fructose, which is about four times higher than the 233 RNU OD−1 h−1 on galactose (single growth experiments). Indeed, fructose-grown cells expressing stable GFP accumulated three to four times more fluorescence than those grown on galactose (Fig. 7B). For cells expressing GFP[ASV], this ratio was similar, as would be expected from the relatively flat curve in Fig. 7A. For cells that carried the gene for GFP[AAV] or GFP[LVA], we estimated from F,OD plots (not shown) that the steady-state fluorescence levels on fructose were approximately six or seven times higher, respectively, than on galactose.

FIG. 7.

Combined effect of promoter strength and GFP stability on the accumulation of fluorescence in E. coli DH5α. (A) Papp/P versus P plot for DH5α. Simulations were done as described for Fig. 5. Values for Dmax and KM used were 1,781 RNU (or RLU) OD−1 h−1 and 9,272 RNU (or RLU) OD−1 for GFP[ASV], 699 and 262 for GFP[AAV], and 1,311 and 390 for GFP[LVA], respectively. These values were obtained as described for Fig. 5, except that instead of the IPTG-responsive PA1/04/03 promoter, we used the fructose-responsive PfruB promoter to drive expression of unstable GFPs. For the simulations, we assumed experimentally observed values for growth rate μ of 0.35 to 0.46 h−1, and for m we used a value of 1.54 h−1. (B) Cell density-normalized fluorescence in cultures of DH5α carrying pPfruB-gfp[tagless], -gfp[ASV], -gfp[AAV], or -gfp[LVA] grown on fructose (solid squares) or galactose (open squares). Overnight LB-grown cells were transferred to fresh M9 medium with fructose or galactose at t = 0 h.

GFP accumulation in single cells within a bacterial population.

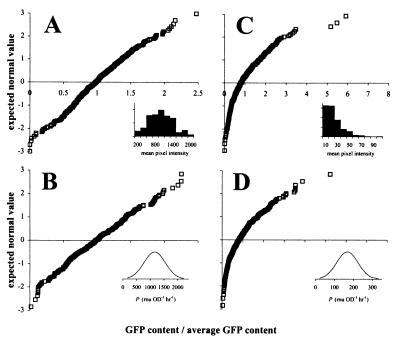

Many applications of GFP as a reporter of promoter activity are concerned with GFP expression at the level of single cells rather than bacterial cultures. We have previously examined the GFP content of individual cells from fructose-induced and uninduced cultures of E. herbicola 299R carrying a PfruB-gfp[AAV] fusion (26). Single-cell GFP content in cultures exposed to fructose appeared to be almost normally distributed (Fig. 8A). We could easily simulate this distribution assuming that promoter activity is not exactly the same for each cell in the population but instead normally distributed around an average value (Fig. 8B). The source of this variability in promoter activity may be intrinsic to the promoter itself or may be attributed to variation in copy number of the plasmid carrying the PfruB-gfp[AAV] fusion.

FIG. 8.

Actual and simulated distributions of single-cell GFP content in fructose-induced (A and B) and uninduced (C and D) cells of E. herbicola 299R carrying plasmid pPfruB-gfp[AAV]. In the normal probability plots shown here, GFP fluorescence of individual cells is expressed on the horizontal axis as the fraction of the population's average single-cell GFP content. In this representation, normally distributed GFP content would yield a straight line. Panels A and C represent the results from actual induction experiments published elsewhere (26). The insets in both of these panels show the corresponding data in histogram format, with GFP content expressed in units of mean pixel intensity. For the simulation of fructose-induced GFP accumulation (B), we determined by using the model the steady-state GFP content (fss) for a collection of 300 individual cells, assuming that the promoter activity varied between cells around an average value of 1,160 RNU OD−1 h−1 with a standard deviation equal to one-third of the average, i.e, 387 RNU OD−1 h−1 (see inset). For the uninduced simulation (D), we assumed the same proportional variation (i.e., one-third) in promoter activity, i.e., P = 168 ± 56 RNU OD−1 h−1. In both simulations, we assumed μ = 0.67 h−1, and for GFP[AAV] Dmax = 232 RNU (or RLU) OD−1 h−1 and KM = 35 RNU (or RLU) OD−1.

When we assumed that uninduced PfruB activity varies in the same proportional way as when the promoter was induced with fructose, we saw a surprising effect in our simulations: the distribution curve of single-cell GFP content was no longer symmetrical but appeared skewed to the right, meaning that the right tail of the curve was longer than the left one (Fig. 8D). This matched quite well our observation of uninduced E. herbicola 299R cells harboring PfruB-gfp[AAV] (Fig. 8C). We may explain this effect as a result of disproportional reduction discussed before: within a group of cells expressing GFP[AAV] from a weak promoter, those with the highest activity are proportionally less affected by degradation and are therefore brighter than cells with the lowest promoter activity. With strong promoters, e.g., PfruB on fructose, this effect is much less pronounced because degradation is already at its maximal capacity and therefore less responsive to variations in GFP content. So far, we have seen skewed distributions only in populations of cells that express unstable variants from weak promoters (not shown). Cells that carry the same promoters fused to the gene for stable GFP yielded normal distributions of GFP content (not shown).

Effect of growth rate on accumulation of fluorescent GFP.

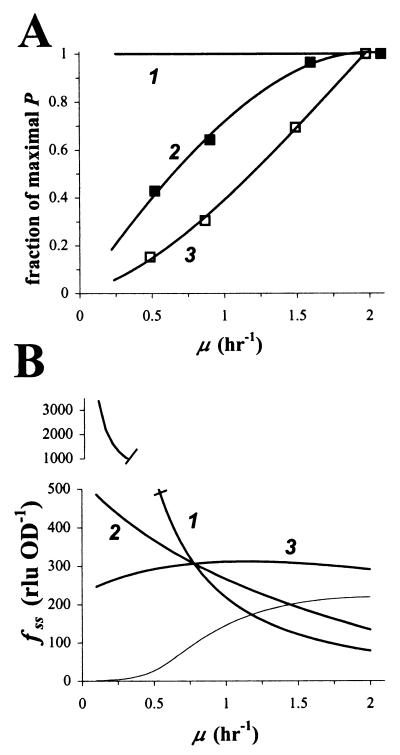

We have mentioned several times already that growth rate is an important determinant of a cell's GFP content. We performed a series of simulations that demonstrate this. If we assume that promoter activity is independent of growth rate μ (Fig. 9A, line marked 1), steady-state fluorescent GFP content becomes inversely proportional to μ (Fig. 9B, curve marked 1). The shape of the curve suggests that when cells are growing slowly, small changes in μ will have a much greater effect on GFP fluorescence than when cells are growing faster. It is probably unjustified to assume that P is independent of μ: it has been established that the activity of many promoters is in fact a function of growth rate (27). But even when we assume a more realistic dependency of P on μ, such as that for the constitutive promoter Pspc in E. coli (from reference 27) (Fig. 9A, line marked 2), GFP content remains inversely proportional to growth rate (Fig. 9B, curve marked 2). The same effect has been observed in E. coli using β-galactosidase as a reporter protein (27).

FIG. 9.

Effect of growth rate on accumulation of GFP fluorescence. (A) We assumed three different dependencies of promoter activity P on growth rate μ: 1, none; 2, as for constitutive promoter Pspc (27); and 3, as for growth rate-responsive promoter Prrn (27). Data points for 2 and 3 were estimated from reference 27, with the following modification: the promoter activity at a given growth rate was expressed as the fraction of the maximal attainable promoter activity. (B) With the help of the model, steady-state GFP content fss was simulated as a function of growth rate μ, assuming the interdependencies given in panel A. As a reference point, we arbitrarily chose a growth rate of μ = 0.78 h−1 and a promoter activity P = 360 RNU OD−1 h−1, which corresponds to E. herbicola 299R::PA1/O4/O3-gfpmut3(pCPP39) cells exposed to 323 μM IPTG (Fig. 3). The thin line represents a simulation of fluorescent GFP accumulation from a Prrn-gfp[AAV] fusion.

This observation demonstrates how a change in μ can alter GFP content without a change in promoter activity. Without consideration for this change in μ, such a shift in GFP content will be explained wrongly as a response of the promoter to whatever caused the cells to adjust their growth rate. The observation also suggests that a constitutive promoter might actually do a good job as an indicator of growth rate, due to the fact that its fluorescent output in combination with stable GFP yields an unambiguous (albeit inverse) correlation with growth rate. When we repeated the simulation using the P, μ curve for the growth rate-dependent promoter Prrn (from reference 27) (Fig. 9A, curve marked 3), GFP content appeared independent of growth rate (Fig. 9B, curve marked 3). This confirms its function as a growth rate-dependent promoter to keep cellular levels of rRNA more or less constant regardless of growth rate. Interestingly, when we did the Prrn simulation in combination with unstable variant GFP[AAV], we observed a clearly positive yet not linear relationship between GFP content and growth rate for values of μ up to 1.5 h−1 (Fig. 9, thin line). This prediction shows a response that is very similar to the one found experimentally with a Prrn-gfp[AAV] fusion in Pseudomonas putida (41).

DISCUSSION

We have presented a theoretical model for GFP accumulation in bacterial cells that is in good agreement with experimental observations. The model can be adopted in its present state to describe, predict, and interpret fluorescence data from any GFP-based reporter system other than the ones described in this paper. In fact, with the proper modifications, it can be put to use right away to model the expression of other reporter proteins as well.

Our model comes with several unique practical properties. First, we derived a set of formulas and tools from the model that allow easy extraction of parameter values from experimental data. For example, an estimate for promoter activity P can be readily obtained from a simple F,OD plot in combination with equation 13. Similarly, values for Dmax and KM of an unstable GFP variant can be estimated from a limited number of data points. Such a hands-on approach should be generally applicable to obtain similar quantitative information for any other promoter-gfp fusion. And once such information is available, simulation of GFP expression using a program like Gepasi is no longer an abstract exercise, but can be related directly to experimental observations. For those who are interested, a copy of the Gepasi file that was used for our GFP simulations will be made available upon request. This practical orientation of our model circumvents the need for more complicated means of data fitting that are often less accessible to those who have no or little familiarity with modeling practices. For example, it would be possible to extract values for P from the plot of F/OD as a function of time t in Fig. 2A by nonlinear curve fitting, but this is no trivial task. We should acknowledge, however, that we were able to implement our approach because the model is relatively simple, i.e., there are a limited number of parameters and variables involved.

Unstable GFP variants such as GFP[AAV], GFP[ASV], and GFP[LVA] have been used with great success as reporters of transiently expressed genes (3, 26, 35, 41). When they were originally reported (4), the unstability of these GFPs was described in terms of half-life times. This does not justify their performance in bacterial cells, as we have demonstrated here, both theoretically and experimentally. Instead of first-order kinetics, the degradation of these variants appears to follow Michaelis-Menten kinetics, and GFP fluorescence needs to be interpreted accordingly. In combination with an inducible promoter, an observed increase in GFP content actually overestimates the real increase in promoter activity, as Fig. 6A and 7A suggest. Depending on the GFP variant that is being used and on the bacterial host that harbors the fusion, that overestimation might become large enough to critically misconstrue GFP fluorescence data. The number of fusions constructed to date that harbor unstable GFPs as reporters of gene expression is still limited, so it will be interesting to see if our hypothesis will hold up as more reports on the use of these variants come out.

There is another good reason for caution with the use of unstable GFPs in reporter fusions. It was recently shown that the activity of the proteases that are thought to be responsible for the degradation of unstable variants like GFP[AAV] is modulated by an auxiliary protein whose expression appears to vary with growth rate (25). This suggests that the parameter Dmax which describes proteolytic activity might be intimately correlated with growth rate. We believe that the increasing popularity of these unstable GFP variants in bacterial reporters (3, 26, 35, 41) invites a closer look into exactly how variations in protease activity quantitatively influence the translation of GFP signal into promoter activity. Certainly, the model described herein provides a valuable framework to start exploring and addressing these questions.

An important lesson from the model is that GFP fluorescence is a function of more than just promoter activity. One important determinant is growth rate, as the simulations in Fig. 9A made clear. We pointed out that small changes in low growth rates have a proportionally large impact on GFP content. This becomes especially relevant, for example, when bacterial bioreporters are employed in complex environments such as soil, where bacterial growth is generally slow and different from one spot to the next. Microlocalities that permit slightly faster growth will contain significantly dimmer bacteria. This effect of growth on GFP content might partially or entirely mask an increase in promoter activity, so that the reporter signal will be effectively underestimated. On the other hand, cells growing slightly slower will have significantly increased GFP levels that might be interpreted falsely as gene induction.

Unfortunately, an accurate determination of growth rate is not always possible. For cells growing in a culture flask, growth rate can be estimated quite easily by monitoring the population increase over time. Many GFP-based bacterial reporter cells, however, are used in an environmental setting that does not allow this approach, e.g., due to substantial heterogeneity in growth rate within the population. Fluorescent in situ hybridization offers a means to quantify ribosome content in individual cells and can provide a reasonable rough estimate of growth rate (37, 47). Such an approach was successfully employed to interpret GFP data from bacterial bioreporters of sugars on plant leaf surfaces (26). Another approach to assess the effect of growth rate may be to relate the output of a bioreporter strain to the inversely proportional fluorescent signal of a control bioreporter that expresses GFP from a constitutive promoter.

The model and its predictions have already proven very useful in our present work. One way it has been informative is in the approximation of plasmid copy number. For example, by comparison of promoter activity in cells that carry plasmid pPfruB-gfp with that in cells carrying the same fusion in monocopy on the chromosome (not shown), we were able to estimate that the plasmid is present in 10 to 30 copies per cell in E. herbicola 299R. We routinely turn to Fig. 6 and 7 to decide which variant of GFP to choose in combination with a particular promoter. For example, Fig. 6 cautions against the use of gfp[LVA] in combination with a promoter activity of less than 400 RNU OD−1 h−1 in 299R because the cells would not be fluorescent. In bacterial strains that do not tolerate very high levels of GFP, like 299R, we commonly use strong promoters in combination with GFP[ASV] instead of stable GFP in order to somewhat reduce GFP content.

We regularly exploit the disproportional degradation of GFP[AAV] and GFP[LVA] in E. herbicola 299R to maximize apparent induction levels, as was shown for the PfruB promoter (Fig. 6). Conceptually, this should work for every promoter with an already high level of expression when uninduced. By artificially decreasing this basal level using unstable variants, the interpretation of GFP fluorescence as an indicator for increased promoter activity will be facilitated considerably. However, as Fig. 8 shows, the use of unstable GFP variants may come at a price at the level of individual cells. At low promoter activities, GFP content is no longer normally distributed among cells, so that it becomes harder to translate a single cell's GFP content back into a corresponding promoter activity. Depending on the promoter that is being used, this may or may not be a problem. With promoters of the on/off type, the difference between the brightest uninduced cell and the dimmest induced cell may be large enough to state unambiguously whether or not a particular reporter cell is exposed to a stimulus. Other promoters are more graded in their response, and in that case, nonnormal overlapping frequency distributions will make it very difficult to assign a promoter activity to the observed fluorescent state of a single bacterium. Possibly, the model will be able to serve an interpretive function in the analysis of such complex GFP data.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank John Casida for access to the fluorimeter in the Environmental Chemistry and Toxicology Laboratory; Jens Bo Andersen for providing us with plasmids pJBA28, pJBA116, pJBA118, and pJBA120; H. Bujard for permission to publish our results on PA1/O4/O3; and Chris Rao for his suggestion to use Gepasi software for our simulations. We are also grateful to Maria Marco, Wally van Heeswijk, and two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on the manuscript.

This research was funded in part by U.S. Department of Agriculture NRI grant 96-35303-3377 and grant no. DE-FG03-86ER13518 from the U.S. Department of Energy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albano C R, Randers-Eichhorn L, Bentley W E, Rao G. Green fluorescent protein as a real time quantitative reporter of heterologous protein production. Biotechnol Prog. 1998;14:351–354. doi: 10.1021/bp970121b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albano C R, Randers-Eichhorn L, Chang Q, Bentley W E, Rao G. Quantitative measurement of green fluorescent protein expression. Biotechnol Tech. 1996;10:953–958. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen J, Heydorn A, Hentzer M, Eberl L, Geisenberger O, Christensen B, Molin S, Givskov M. gfp-based N-acyl homoserine-lactone sensor systems for detection of bacterial communication. J Bacteriol. 2001;67:575–585. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.2.575-585.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersen J B, Sternberg C, Poulsen L K, Petersen-Bjørn S, Givskov M, Molin S. New unstable variants of green fluorescent protein for studies of transient gene expression in bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2240–2246. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.6.2240-2246.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barker L P, Brooks D M, Small P L C. The identification of Mycobacterium marinum genes differentially expressed in macrophage phagosomes using promoter fusions to green fluorescent protein. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1167–1177. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baty A M, Eastburn C C, Diwu Z, Techkarnjanaruk S, Goodman A E, Geesey G G. Differentiation of chitinase-active and non-chitinase-active subpopulations of a marine bacterium during chitin degradation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:3566–3573. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.8.3566-3573.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Better M, Helinski D R. Isolation and characterization of the recA gene of Rhizobium meliloti. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:311–316. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.1.311-316.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bogs J, Geider K. Molecular analysis of sucrose metabolism of Erwinia amylovora and influence on bacterial virulence. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:5351–5358. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.19.5351-5358.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandl M T, Lindow S E. Cloning and characterization of a locus encoding an indolepyruvate decarboxylase involved in indole-3-acetic acid synthesis in Erwinia herbicola. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4121–4128. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4121-4128.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cha H J, Srivastava R, Vakharia V N, Rao G, Bentley W E. Green fluorescent protein as a noninvasive stress probe in resting Escherichia coli cells. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:409–414. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.2.409-414.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward W W, Prasher D C. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cormack B P, Valdivia R H, Falkow S. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) Gene. 1996;173:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeLorenzo V, Herrero M, Jakubzik U, Timmis K. Mini-Tn5 transposon derivatives for insertion mutagenesis, promoter probing, and chromosomal insertion of cloned DNA in gram-negative eubacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6568–6572. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6568-6572.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottesman S, Roche E, Zhou Y, Sauer R T. The ClpXP and ClpAP proteases degrade proteins with carboxy-terminal peptide tails added by the SsrA-tagging system. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1338–1347. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han L, Khetan A, Hu W-S, Sherman D H. Time-lapsed confocal microscopy reveals temporal and spatial expression of the lysine β-aminotransferase gene in Streptomyces clavuligerus. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:878–886. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen L H, Ferrari B, Sørensen A H, Veal D, Sørensen S J. Detection of oxytetracycline production by Streptomyces rimosus in soil microcosms by combining whole-cell biosensors and flow cytometry. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:239–244. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.1.239-244.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen L H, Sørensen S J. Versatile biosensor vectors for detection and quantification of mercury. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;193:123–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heim R, Cubitt A B, Tsien R Y. Improved green fluorescence. Nature. 1995;373:663–664. doi: 10.1038/373663b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrero M, DeLorenzo V, Timmis K N. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:6557–6567. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.11.6557-6567.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill C, Waight R, Bardsley W. Does any enzyme follow Michaelis-Menten equation? Mol Cell Biochem. 1977;15:173–178. doi: 10.1007/BF01734107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobi C A, Roggenkamp A, Rakin A, Zumbihl R, Leitritz L, Heesemann J. In vitro and in vivo expression studies of yopE from Yersinia enterocolitica using the gfp reporter gene. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:865–882. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joyner D C, Lindow S E. Heterogeneity of iron bioavailability on plants assessed with a whole-cell GFP-based bacterial biosensor. Microbiology. 2000;146:2435–2445. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-10-2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kataoka M, Kosono S, Tsujimoto G. Spatial and temporal regulation of protein expression by bldA within a Streptomyces lividans colony. FEBS Lett. 1999;462:425–429. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01569-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keiler K C, Waller P R H, Sauer R T. Role of a peptide tagging system in degradation of proteins synthesized from damaged messenger RNA. Science. 1996;271:990–993. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levchenko I, Seidel M, Sauer R, Baker T. A specificity-enhancing factor for the ClpXP degradation machine. Science. 2000;289:2354–2356. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leveau J H J, Lindow S E. Appetite of an epiphyte: quantitative monitoring of bacterial sugar consumption in the phyllosphere. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3446–3453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061629598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang S T, Bipatnath M, Xu Y C, Chen S L, Dennis P, Ehrenberg M, Bremer H. Activities of constitutive promoters in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:19–37. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lissemore J L, Jankowski J T, Thomas C B, Mascotti D P, deHaseth P L. Green fluorescent protein as a quantitative reporter of relative promoter activity. BioTechniques. 2000;28:82–89. doi: 10.2144/00281st02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lutz R, Bujard H. Independent and tight regulation of transcriptional units in Escherichia coli via the LacR/O, the TetR/O and AraC/I-1-I-2 regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1203–1210. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mendes P. GEPASI: a software package for modelling the dynamics, steady states and control of biochemical and other systems. Comput Appl Biosci. 1993;9:563–571. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/9.5.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller W G, Leveau J H J, Lindow S E. Improved gfp and inaZ broad-host-range promoter-probe vectors. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2000;13:1243–1250. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.11.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Müller-Hill B, Crapo L, Gilbert W. Mutants that make more Lac repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;59:1259–1264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.59.4.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neidhardt F C, Ingraham J L, Schaechter M. Physiology of the bacterial cell: a molecular approach. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patterson G H, Knobel S M, Sharif W D, Kain S R, Piston D W. Use of the green fluorescent protein and its mutants in quantitative fluorescence microscopy. Biophys J. 1997;73:2782–2790. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78307-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramos C, Molbak L, Molin S. Bacterial activity in the rhizosphere analyzed at the single-cell level by monitoring ribosome contents and synthesis rates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:801–809. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.2.801-809.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reizer J, Reizer A, Kornberg H L, Saier M H. Sequence of the fruB gene of Escherichia coli encoding the diphosphoryl transfer protein (DTP) of the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;118:159–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruimy R, Breittmayer V, Boivin V, Christen R. Assessment of the state of activity of individual bacterial cells by hybridization with a ribosomal RNA targeted fluorescently labelled oligonucleotidic probe. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1994;15:207–213. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sambrook J, Maniatis T, Fritsch E F. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scholz O, Thiel A, Hillen W, Niederweis M. Quantitative analysis of gene expression with an improved green fluorescent protein. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:1565–1570. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shetty R, Ramanathan S, Badr I, Wolford J, Daunert S. Green fluorescent protein in the design of a living biosensing system for l-arabinose. Anal Chem. 1999;71:763–768. doi: 10.1021/ac9811928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sternberg C, Christensen B B, Johansen T, Nielsen A T, Andersen J B, Givskov M, Molin S. Distribution of bacterial growth activity in flow-chamber biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4108–4117. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.9.4108-4117.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stretton S, Techkarnjanaruk S, McLennan A M, Goodman A E. Use of green fluorescent protein to tag and investigate gene expression in marine bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2554–2559. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2554-2559.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Subramanian S, Srienc F. Quantitative analysis of transient gene expression in mammalian cells using the green fluorescent protein. J Biotechnol. 1996;49:137–151. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(96)01536-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsien R Y. The green fluorescent protein. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:509–544. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valdivia R H, Falkow S. Bacterial genetics by flow cytometry: rapid isolation of Salmonella typhimurium acid-inducible promoters by differential fluorescence induction. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:367–378. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valdivia R H, Hromockyj A E, Monack D, Ramakrishnan L, Falkow S. Applications for green fluorescent protein (GFP) in the study of host-pathogen interactions. Gene. 1996;173:47–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wallner G, Amann R, Beisker W. Optimizing fluorescent in situ hybridization with rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes for flow cytometric identification of microorganisms. Cytometry. 1993;14:136–143. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990140205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao H, Thompson R B, Lockatell V, Johnson D E, Mobley H L T. Use of green fluorescent protein to assess urease gene expression by uropathogenic Proteus mirabilis during experimental ascending urinary tract infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:330–335. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.330-335.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]