Abstract

The sensory cells of the inner ear, called hair cells, do not regenerate spontaneously and therefore, hair cell loss and subsequent hearing loss are permanent in humans. Conversely, functional hair cell regeneration can be observed in non-mammalian vertebrate species like birds and fish. Also, during postnatal development in mice, limited regenerative capacity and the potential to isolate stem cells were reported. Together, these findings spurred the interest of current research aiming to investigate the endogenous regenerative potential in mammals. In this review, we summarize current in vitro based approaches and briefly introduce different in vivo model organisms utilized to study hair cell regeneration. Furthermore, we present an overview of the findings that were made synergistically using both, the in vitro and in vivo based tools.

Keywords: hair cell regeneration, stem cells, organoids, cell lines, model organisms

Introduction

Genetic and acquired hearing loss affects 1 in 5 people translating to approximately 1.57 billion globally (GBD-Hearing-Loss-Collaborators, 2021). Furthermore, global disease burden is expected to continually rise as life expectancy and societal noise burdens increase. For many patients with sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) two options are available to overcome the limitations associated with the disease. The first option is a hearing aid, which is effective in supporting residual hearing. However, acceptance among patients is low and only approximately 20% of people with hearing loss use hearing aids (Larson et al., 2000). The second option is a cochlear implant for those with severe hearing loss, but outcomes are variable and cannot fully restore hearing. Both options are technical solutions to a biological problem and a medical treatment to cure hearing loss remains to be developed.

Hearing loss, specifically SNHL, is due to loss or damage of mechanosensory cells within the organ of Corti of the cochlea. The organ of Corti is constituted by two cell types, hair cells (HCs) and supporting cells (SCs). Upon HC loss, SCs remain and have been identified as the major target in HC regeneration. However, with the expression of the cell cycle inhibitor p27Kip1 (Chen and Segil, 1999; Löwenheim et al., 1999), SCs become postmitotic and are deemed nonregenerative in mammals (Corwin and Cotanche, 1988). Therefore, numerous efforts are underway to examine the mechanisms regulating inner ear specification, endogenous repair, and the potential of cell replacement therapies.

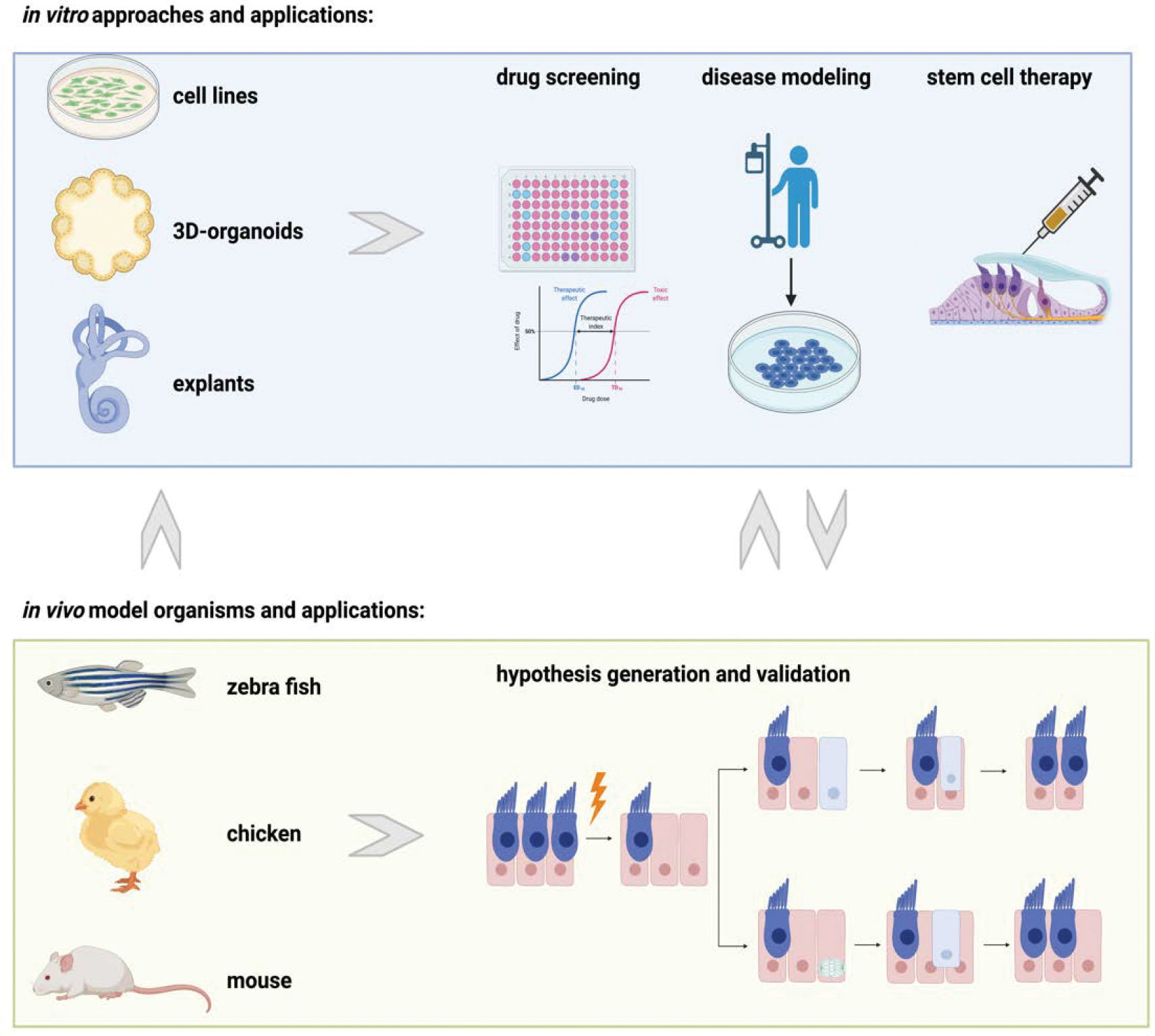

Research efforts have used various in vitro and in vivo models to study inner ear regeneration. In vivo based approaches have encountered challenges owing to the limited number of HCs available. In contrast, in vitro based approaches may be able to overcome the small cell numbers; however, efficient differentiation of SCs and HCs reaching adult-like stages has been challenging. Nevertheless, many signaling pathways and biological processes critical for inner ear specification, proliferation, and differentiation have been identified. Both in vitro and in vivo experiments have utilized various mammalian and nonmammalian species, such as zebrafish, chicken, and mice. In the first half of this review, we will provide an overview of the current in vitro and in vivo based approaches (Figure 1). In the second half of the review, we will summarize what we have learnt about HC regeneration, which is based on experiments synergistically utilizing in vitro and in vivo based approaches.

Figure 1. Approaches and Model Organisms in Regenerative Research of the Inner Ear.

Cell lines, 3D-organoids, and explants are in vitro approaches used to perform drug screening, disease modeling, and to explore stem cell therapies. In vivo model organisms like fish, chicken, and the mouse are used to study development and endogenous regeneration to develop new hypotheses and validate findings from in vitro based experiments.

In vitro Approaches

Scalability and the potential for high throughput applications are the two hallmarks of in vitro based experiments that allow for screening of drug libraries and small molecules. Additionally, available in vitro protocols have been translated to study ototoxicity and different aspects of regeneration, which will be discussed below.

Immortalized Cell Lines

Inner ear cell lines, like UB/OC-1/2 (Rivolta et al., 1998) or the HEI-OC1 (Kalinec et al., 2003), were first developed to provide screening tools for ototoxic reagents. To generate cell lines representing different levels of inner ear maturation, relevant tissues were isolated from the Immortomouse (Jat et al., 1991) at various developmental time points. Generally, cell culture conditions at 33°C with media supplemented with γ-interferon support stable proliferation, whereas increasing the temperature to 39°C and withdrawal of γ-interferon induces differentiation of the inner ear cell line. Differentiation of UB/OC-1/2 or HEI-OC1 cell lines does not generate specific inner ear cell types, like outer HCs or Deiters’ cells, but the transcriptomic profiles are reminiscent of inner ear tissue. Although differentiation (Carpena et al., 2021) has been studied with this model, the majority of studies examine ototoxicity (Cho et al., 2021; Dhukhwa et al., 2021; Gonçalves et al., 2019) and numerous other topics like apoptotic pathways, autophagy (Zhu et al. 2021), senescence (Zhu et al., 2021), and mechanisms of cell protection (Ingersoll et al., 2020; Kather et al., 2021; Wen et al., 2020).

In contrast, immortalized multipotent otic progenitor (iMOP) cells (Kwan et al., 2015) were generated by viral overexpression of C-MYC and supplemented with bFGF. iMOPs have been used to investigate self-renewal potential, differentiation of inner ear cell types (Azadeh et al., 2016), and the interplay between C-MYC and SOX2 (Kwan et al., 2015). In summary, inner ear cell lines provide valuable tools in inner ear research. However, the lack of resemblance of specific inner ear cell types upon differentiation, limits their use in regenerative research. Furthermore, stem cell-based approaches and directed differentiation of HCs have evolved as widely used alternatives.

Stem Cell-Based Approaches

A multitude of different stem cell types have been utilized to generate inner ear cell types. More recently, research has focused on tissue specific stem cells (Kubota et al., 2021; Oshima et al., 2007; White et al., 2006) and pluripotent stem cells (Koehler et al., 2013; Li et al., 2003b), while neuronal stem cells (Wei et al., 2008) and mesenchymal stem cells (Jeon et al., 2007) were explored to a lesser extent. Generally, compared to explant culture or in vivo applications, stem cell-based approaches hold the promise to provide larger quantities of HCs for analysis.

Tissue Specific Stem Cells

The majority of tissue specific stem cells are isolated from mouse inner ears (Diensthuber et al., 2014; Li et al., 2003a; McLean et al., 2016; Oshima et al., 2007; Rousset et al., 2020a) and less frequently from human organ of Corti, utricle, and spiral ganglion (Chen et al., 2009; Roccio et al., 2018; Senn et al., 2020). Sphere forming culture conditions allow for propagation of the cells, and differentiation occurs under adherent culture conditions combined with growth factor withdrawal or co-culture with feeder cells (Oshima et al., 2007; White et al., 2006). HC-like cells surrounded by SC-like cells can be created under these culture conditions. Initially, this approach suffered from low HC numbers, but later iterations of the protocol increased the HC yield through use of small molecules or flow sorting of defined cell populations (Kubota et al., 2021; McLean et al., 2017). Although the assay relies on primary tissue, which implies regular use of animals to generate new HC-like cells, several regenerative studies use this model. For example, Notch inhibitors and glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) inhibitors were examined and shown to increase the potential to generate HCs from oto-spheres (McLean et al., 2017; Mizutari et al., 2013; Roccio et al., 2015). The sphere assay was also used to study the impact of reactive oxygen species on neurons (Rousset et al., 2020b) and DNA methylation at the Sox2 locus (Waldhaus et al., 2012).

Pluripotent Stem Cells

While the use of tissue specific stem cells has evolved over the past two decades, pluripotent stem cell-based protocols were developed in parallel. Early versions started with the induction of ectoderm and non-neuronal ectoderm and continued differentiation toward otic fates under adherent culture conditions (Chen et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2012; Ealy et al., 2016; Oshima et al., 2010; Ronaghi et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2016). Generally, those protocols resulted in the generation of HC-like cells or their respective progenitor cells in a 2D-culture environment. More recently, robust differentiation of HCs in 3D-organoids has been reported (Koehler et al., 2013). The aggregate based protocols allow for the study of HCs in a tissue-like context together with SCs and neurons (Chen et al., 2012; Jeong et al., 2018; Koehler et al., 2017; Matsuoka et al., 2017; Shi et al., 2007). Some of the major advantages of the pluripotent stem cell approaches are the reduced use of laboratory animals in comparison to all alternative approaches, and readily available protocols for mouse (Abboud et al., 2017; Koehler et al., 2013; Li et al., 2003b; Nie et al., 2017; Oshima et al., 2010; Ouji et al., 2012) and human embryonic stem cells (ESC) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) (Chen et al., 2012; Ding et al., 2016; Ealy et al., 2016; Gunewardene et al., 2014; Hosoya et al., 2017; Jeong et al., 2018; Koehler et al., 2017; Lahlou et al., 2018; Matsuoka et al., 2017; Mattei et al., 2019; Nie and Hashino, 2020; Ohnishi et al., 2015; Ronaghi et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2007). Specifically, human iPSCs aggregates were used to study deafness genes and mutations for genes like USH2A (Liu et al., 2021), MYO15A (Chen et al., 2016), MYO7A (Tang et al., 2016), and SLC26A4 (Chen et al., 2020). As methods advance, the use of human iPSCs will likely allow for the modeling of complex diseases, like the Waardenburg syndrome (Huang et al., 2021).

Current limitations of the pluripotent stem cell-based approaches relate to the cellular output of the current protocols. Several studies show that most HCs generated appear to be of vestibular phenotype (Jeong et al., 2018; Koehler et al., 2017; Mattei et al., 2019). However, with respect to modeling SNHL or age-related hearing loss, auditory HCs have yet to be generated. Therefore, protocol variations that could tip the balance from vestibular toward auditory HCs remain to be developed. Furthermore, HC-like cells generated in 3D-culture are encapsulated in vesicles that develop from the aggregate. This hinders the use of aggregates in high throughput imaging-based approaches as needed for drug development.

Direct Programming

As mentioned above, challenges with organoids are related to the encapsulation of the HCs. To overcome the need for the 3D-aggregates, HCs generated in a single epithelial layer would allow for automated imaging-based screens, especially when used in connection with fluorescent reporter expression (Costa et al., 2015; Menendez et al., 2020). Menendez et al., were able to directly program embryonic fibroblasts, adult tail tip fibroblasts, and postnatal murine SCs with a 4-transcription factor cocktail (SIX1, ATOH1, POU4f3, and GFI1) that reprograms target cells into HCs (Menendez et al., 2020). Furthermore, these induced HCs (iHCs) are a promising model that can be scaled up to identify ototoxic agents, factors significant for HC maturation, regeneration, and function.

Tissue & Organ Culture

Ex vivo organ culture models provide two major advantages compared to stem cell-based approaches. 1) The complex cellular architecture of the sensory epithelium is preserved and 2) cells of the explant represent a relatively homogenous maturation stage as compared to the developmental variability seen in stem cell-based approaches. Different protocols have been developed starting with the culture of embryonic (Haque et al., 2015) and postnatal sensory inner ear organs of mouse, human, and chicken (Landegger et al., 2017; Oesterle et al., 1993; Ogier et al., 2019). Specifically, a variation of the protocol was established to preserve the 3D-tissue context during culture and individual sensory organs were embedded and cultured in gels (Gnedeva et al., 2018). Alternatively, whole inner ear bony labyrinths (Arnold et al., 2010; Hahn et al., 2008) can be cultured as well. To create culture conditions that recapitulate in vivo conditions most accurately, the bony labyrinths were supported with buoyancy beads to generate a microgravity environment. Generally, ex vivo organ culture protocols allow for the culture of sensory epithelia for up to 7 days in vitro. However, a maximum culture duration of 14 days with surviving HCs has been reported (Nayagam et al., 2013; Sobkowicz et al., 1975). Due to its versatility, the assay was used in many studies covering ototoxicity and oto-protection (Ingersoll et al., 2020; Kopke et al., 1997; O’Sullivan et al., 2020; Perny et al., 2017; Tropitzsch et al., 2014; Tropitzsch et al., 2019). Furthermore, the effects of different inhibitors on cell differentiation and regeneration for LATS kinases (Kastan et al., 2021; Rudolf et al., 2020), p27Kip1 (Walters et al., 2014), GSK3β (Ellis et al., 2019; Roccio et al., 2015), and Notch pathway (Mizutari et al., 2013) were tested ex vivo.

Current protocols face two challenges for the future: 1) the limited duration of culture period for primary cultures and 2) the inability to culture adult inner ear tissues. Furthermore, the presence of resident macrophages from isolated tissues may interfere with experimental outcomes (Francis and Cunningham, 2017). However, the ability to overcome the limited number of progenitor cells and screen both ototoxic and regenerative compounds before moving in vivo are the largest advantage to in vitro experimentation.

In vivo Regeneration

Humans lack the capacity to regenerate lost HCs. In contrast, non-mammalian vertebrate species and neonatal mice show the capacity to regenerate lost HCs after trauma. While this is not an exhaustive list of model organisms employed, the following section will review some common vertebrate model organisms used to study HC regeneration in vivo.

Zebrafish

Zebrafish are a classic model system for developmental biology, molecular biology, regeneration, and with increasing frequency, drug screens (Koleilat et al., 2020; Ou et al., 2009; Teitz et al., 2018; Thomas et al., 2015). Just like in mammals, fish utilize mechanosensitive HCs in the inner ear for hearing (Pickett and Raible, 2019). Additionally, HCs can be found in the lateral line organ distributed along the body’s surface, and these HCs are turned over throughout the life cycle of the fish (Baxendale and Whitfield, 2016; Pickett and Raible, 2019). Following damage, lateral line HC regeneration occurs within 48 hours. Besides the direct accessibility of HCs in the lateral line, the major advantages of the zebrafish as a model organism for functional HC regeneration are owing to the large amount of offspring at a single time, optical clarity for imaging, and access to a vast number of genetic mutants. Numerous studies examining regeneration and ototoxicity have been performed owing to the ease in modeling genetic hearing loss and drug delivery through the water (Koleilat et al., 2020; Ou et al., 2009; Teitz et al., 2018; Thomas et al., 2015). Additionally, high throughput in vivo screening of otoprotective and ototoxic compounds is feasible in the zebrafish model system due to their small size and ability to fit into 96-well plates. Limitations faced when using zebrafish are the lack of different HC phenotypes, like inner and outer HCs, and the evolutionary distance to the mammalian counterparts. Notwithstanding, zebrafish studies have contributed to better understanding genetic and acquired hearing loss and regenerative mechanisms.

Chicken

Like zebrafish, birds have the capacity to regenerate lost HCs in the auditory and vestibular organs as well (Girod et al., 1991; Morest and Cotanche, 2004; Oesterle et al., 1993; Warchol and Corwin, 1996). Unlike in zebrafish, HCs are not constantly turned over throughout life and must first undergo damage in order to regenerate (Corwin and Cotanche, 1988; Girod et al., 1991). Chick embryos have classically been a strong model system for developmental biology owing to the ease of access to the embryo during development through shell windowing (Amprino and Camosso, 1959; Kieny, 1959; Waddington, 1950). Like the murine cochlea (Son et al., 2012), the avian basilar papilla is tonotopically organized (Girod et al., 1991; Son et al., 2015). More recent mechanistic studies of avian inner ear cells using single-cell sequencing during development and regeneration have helped to resolve much of the molecular basis of HC regeneration (Alvarado et al., 2011; Benkafadar et al., 2021; Janesick et al., 2021). Furthermore, comparative examination of mouse vs. chicken SCs after damage holds promise to highlight the differences in the cellular response between both species. The shorter evolutionary distance between birds and humans and the accessibility of the embryo in ovo has spurred additional interest in the chicken as model organism for HC regeneration (Alvarado et al., 2011; Benkafadar et al., 2021; Girod et al., 1991; Perl et al., 2018; Son et al., 2015).

Mouse

Mice were extensively studied as a mammalian model system for HC regeneration or the lack thereof. While neonatal mice show the ability to regenerate HCs (Chai et al., 2012; Cox et al., 2014; Oshima et al., 2007; Shi et al., 2012; White et al., 2006), the organ of Corti in adult mice does not regenerate spontaneously (Mizutari et al., 2013). Furthermore, mice exhibit age related hearing loss similarly to humans (Shone et al., 1991). Additional experimental advantages include the potential to isolate inner ear stem cells from neonatal mice as discussed earlier (Cox et al., 2014; Oshima et al., 2007; White et al., 2006). Furthermore, genetically modified mouse strains have paved the way to examine the molecular basis of human disease. For example, the shaker-1 mouse carries a mutation in MyoVIIa-gene and therefore served as a model for Usher syndrome (el-Amraoui et al., 1996; Gibson et al., 1995). Comparing the findings from different model organisms suggest that the molecular machinery necessary to regenerate HCs may be present in adult mammals; nevertheless, strategies to activate the regenerative potential remain to be determined.

What have we learnt about hair cell regeneration?

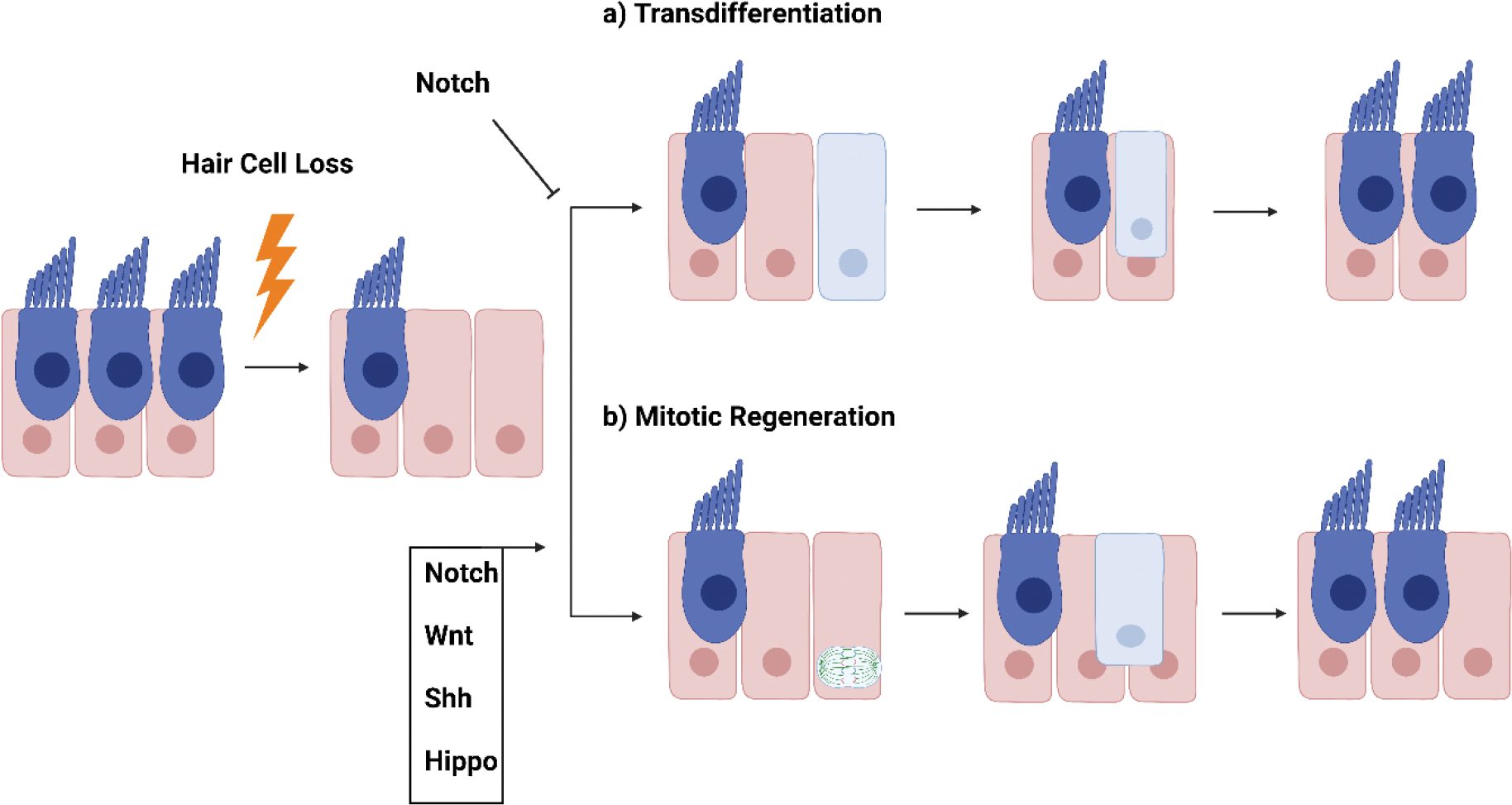

Our current knowledge about cell biological processes and the molecular pathways controlling regeneration is supported by various in vivo and in vitro based experiments. In the following section, findings will be summarized. Mechanosensory HCs are embedded in a layer of SCs. This conformation of cells is conserved across various model organisms from fish to humans. Both HCs and SCs share a common progenitor cell during cochlear development (Xu et al., 2017), and following damage the presence of SCs is required for HC regeneration (Bhatt et al., 2001; Izumikawa et al., 2008). HC regeneration occurring in fish, birds, and postnatal mammals relies on two cellular mechanisms (Figure 2):

Figure 2. Mechanisms of Hair Cell Regeneration.

HCs regenerate through a) transdifferentiation, where a SC directly converts into a HC or b) through mitotic regeneration, where SCs first proliferate, then the daughter cells differentiate into new HCs and/or SCs. Different molecular pathways involved were identified.

1) Transdifferentiation occurs when HC damage results in a direct conversion of SCs into HCs or 2) through mitotic regeneration when SCs re-enter the cell cycle, divide, and the daughter cells differentiate into new HCs as well as SCs. While HC regeneration at the cellular level has been studied for decades, the molecular mechanisms controlling the regenerative process are still not fully understood. Below, we discuss several signaling pathways, such as Wnt, Notch, Shh, and Hippo, which have been shown to be involved in HC development and regeneration.

Notch Signaling

Notch signaling within the organ of Corti was first examined for its contribution to prosensory domain specification and HC differentiation (Daudet and Lewis, 2005; Kiernan et al., 2001; Lanford et al., 1999; Maass et al., 2015; Woods et al., 2004). Specifically, the molecular mechanism controlling HC differentiation spurred the interest in potential regenerative applications. During HC differentiation, Notch singling functions through lateral inhibition; HCs express the Notch-ligand, that upon binding to its receptor inhibits SCs from differentiating into HCs. Mechanistic analysis has identified the bHLH transcription factor Atoh1 as a downstream target, which is negatively regulated by Notch signaling (Driver et al., 2013; Jones et al., 2006). Inhibition of Notch signaling was found to enhance existing regenerative capacity in avian (Alvarado et al., 2011), zebrafish (Jiang et al., 2014), and perinatal mice (Yamamoto et al., 2006) through trans-differentiation and mitotic regeneration. In contrast, neonatal HC differentiation was decreased in a murine conditional Notch overexpression model (McGovern et al., 2018). Related to these findings, delivery of γ-secretase inhibitor aiming to block Notch signaling after noise damage in the adult mouse ear was explored (Mizutari et al., 2013) and clinical trials for several γ-secretase inhibitors followed (Nakajima, 2015).

Wnt Signaling

Canonical Wnt signaling contributes to inner ear development controlling progenitor cell proliferation and HC differentiation (Bok et al., 2007a; Chai et al., 2012; Dabdoub et al., 2003; Jacques et al., 2012). Ectopic activation of Wnt signaling induces proliferation of prosensory cells and induces regeneration of HCs in perinatal mice (Chai et al., 2012; Song and Wang, 2020). Conversely, pharmacologic blocking of Wnt signaling or genetic targeting decreases proliferation in the prosensory domain. Lgr5 was identified as a downstream target of Wnt-signaling and successfully established as Wnt-reporter (Chai et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2012). Flow sorting of Lgr5+ cells allows for enrichment of a defined progenitor pool from the postnatal cochlea, which were found to possess the capacity of self-renewal and to differentiate into new HCs (Bramhall et al., 2014; Chai et al., 2012). These studies suggest that the Lgr5+ cells possess the capacity for regeneration. Like other tissues during development, the Wnt and Notch pathways intersect during tissue specification (Chen et al., 2002; Clevers, 2006; Johnson Chacko et al., 2020; Lanford et al., 1999). Specifically, both Wnt and Notch pathways regulate expression of key HC transcription factor, Atoh1, although in a converse manner (Chen et al., 2002; Jeon et al., 2011; Nakajima, 2015). This emphasizes the need for precise temporal control of signaling pathway activity for correct specification and differentiation.

Sonic Hedgehog Signaling

Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling plays an important role in patterning the otocyst and, together with Wnt signaling, defines the dorsal ventral axis of the developing cochlea. (Bok et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2002). Shh knock out mice demonstrate that Shh signaling is not required for otic vesicle formation but required for induction and specification of the sensory organs (Riccomagno et al., 2002). Additionally, Shh has roles in regulating the tonotopic patterning of cells along the longitudinal axis of the cochlea (Son et al., 2015) and in supporting the undifferentiated prosensory progenitor state in the cochlear apex (Bok et al., 2007b; Bok et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2010; Tateya et al., 2013). In neonatal mice following HC damage, overexpression of Shh induces SC proliferation and HC regeneration (Chen et al., 2017). Additionally, the newly formed HCs were derived from Lgr5+ progenitors, which further emphasizes the interconnectivity of signaling pathways during cochlear development and regeneration.

Hippo Signaling

Hippo signaling through YAP/TEAD transcriptional regulators is a conserved regulatory pathway in numerous tissues and across species (Calses et al., 2019; Dey et al., 2020; Galli et al., 2015; Gnedeva et al., 2020; Rudolf et al., 2020; Zanconato et al., 2015). Although the transcriptional targets of YAP/TEAD are largely cell type specific, similar functions in controlling proliferation, apoptosis, tissue regeneration, and organ size have been observed (Galli et al., 2015; Gnedeva et al., 2020; Zanconato et al., 2015). Recently, studies have highlighted the role of Hippo signaling in both murine and avian inner ear size (Gnedeva et al., 2020; Rudolf et al., 2020). In the developing murine organ of Corti, TEAD target gene expression was observed to decrease sharply as the organ of Corti exit cell cycle around E14.5 (Gnedeva et al., 2020). Additionally, conditional knock-out of YAP reduces the size of the utricle and organ of Corti at E18.5. Within the adult avian utricle, nuclear YAP protein and proliferation were observed, while sequestered YAP was found in adult murine utricular SCs (Rudolf et al., 2020). Additionally, conditional overexpression of YAP in mice at P10 resulted in cell cycle reentry following damage (Gnedeva et al., 2020). Recently, the small molecule TRULI was identified as a compound that inhibits Lats kinases (LATS1/2), which are responsible for YAP cytoplasmic sequestration and inactivation (Kastan et al., 2021). Adult mice treated with TRULI exhibited proliferation in utricle SCs but not the organ of Corti. These studies emphasize the importance of Hippo signaling in inner ear proliferation, organ size regulation, and as a potential target for HC regeneration.

Strategies in Treatment of Hearing Loss

Cell Replacement Therapy

Cell replacement therapy is an area of research located at the intersection of in vitro and in vivo based experimentation. The success in differentiating stem cells into inner ear cell types raised the interest in regeneration of lost HCs or spiral ganglion neurons by transplanting undifferentiated stem cells or partly differentiated stem cells into damaged ears. However, studies in mice have faced challenges since the high potassium concentration in the endolymph poses a challenge for stem cell survival (Hu et al., 2004). When mESCs were transplanted into undamaged rat cochlea only about 1% of the stem cells survived and integrated. Improvements were made by transplanting stem cells into damaged ears, which resulted in 25% of the cells surviving for up to 4 weeks (Regala et al., 2005). Further progress was made with supplementation with BDNF and chondroitinase ABC enzyme (ChABC) to improve survival and migration, respectively (Palmgren et al., 2012). Further challenges are being addressed regarding differentiation into functional HCs or neurons (Gokcan et al., 2016). Generally, injection of undifferentiated ESCs is associated with the formation of teratomas (Chen et al., 2018; Fukuda et al., 2006). However, the use of differentiated stem cells is intended to mitigate both problems. Differentiation of neural cell types that are subsequently implanted with outgrowing neurites resulted in improved auditory brainstem responses (Chen et al., 2012; Fukuda et al., 2006; Ishikawa et al., 2017; Lopez-Juarez et al., 2019). In summary, functional recovery of spiral ganglion neurons or HCs by replacement remains a promising strategy but outcomes need to be improved.

Gene Therapy

Gene therapy including, gene transfer and gene editing, holds promise in treating both genetic and acquired deafness. Recent years have seen immense progress in developing methodologies for gene delivery to the cochlea to induce regeneration. In the following section we will briefly summarize some advances in gene therapy in mammals and highlight studies using Atoh1 gene delivery.

Studies have used in vivo viral delivery of genes, such as neurotropic factor-9, TGF-beta 1, and GDNF, following ototoxic damage in rats and guinea pigs (Kawamoto et al., 2003; Zheng et al., 2011; Zheng et al., 2013). Additionally, mice with genetic mutations in Tmc1, a gene associated with genetic deafness, were able to largely recover hearing when treated with Tmc1 in an adeno-associated virus (AAV) based approach (Nist-Lund et al., 2019; Valentini et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2021). Delivery of reagents through the round window of the cochlea allows for a more directed delivery of gene therapy in vivo (Ivanchenko et al., 2021; Valentini et al., 2020). Mice with Usher syndrome treated with AAVs delivering Clarin-1 (Dulon et al., 2018) or sans (Emptoz et al., 2017) through the intracochlear route both display some preservation of hearing. Variations of AAVs have been developed in order to increase the safety and efficacy for human treatment (Valentini et al., 2020). Additionally, nonviral approaches are being developed using liposomes, peptides, and polymers in order to deliver genes for expression or for genetic alteration with CRISPR/CAS9 (Dong et al., 2019; Farooq et al., 2020). Specific mutations associated with hearing loss have been successfully corrected in stem cells derived from patients with genetic hearing loss (Chen et al., 2016; Dong et al., 2019; Farooq et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2021; Omichi et al., 2019). CRISPR/CAS9 correction of gene mutations could address the challenges faced with multigenic conditions and some hereditary mutations have the potential to be corrected before implantations of a blastocyst or in utero. However, the efficacy and specificity must first be improved before it is employed for treatment of humans.

While numerous genes are candidates for gene therapy, we will discuss one gene of importance, ATOH1. Atonal homolog 1 (ATOH1) is a transcription factor expressed in the early progenitors of the Organ of Corti and has been described as the master regulator of HC fate (Woods et al., 2004). ATOH1 is essential for HC differentiation and is regulated by Wnt and NOTCH signaling, as described above (Bai et al., 2021; Driver et al., 2013; Ellis et al., 2019; Jeon et al., 2011; Woods et al., 2004). Deafness causing mutations for the human ATOH1 gene have not been reported; however, due to its role as master regulator in hair cell development, initial gene therapeutic approaches focused on the transcription factor. Studies in mice have found that in utero gene delivery of Atoh1 resulted in excessive HCs within the cochlea (Gubbels et al., 2008). Furthermore, these excess HCs were functional in the postnatal animal. In both genetically deaf mice and those with HC damage from ototoxic drugs, Atoh1 gene delivery was able to induce HC regeneration (Izumikawa et al., 2008; Izumikawa et al., 2005; Staecker et al., 2007). These studies demonstrate the importance of Atoh1 in HC differentiation and regeneration. Further examination of Atoh1 transcriptome and interactome may provide more targeted therapies and open the possibilities for pathway specific small molecules.

While gene therapy isn’t available for human patients with genetic and acquired hearing loss at this time, research is steadily moving forward. Gene therapy has historically faced the challenge of viral vector safety, specific cell type delivery, and off target effects. Overcoming these challenges will be key in developing effective and safe clinical treatments.

Conclusions and Future Directions

A variety of protocols and methods have been established to overcome experimental limitations like encapsulation and sparsity of the inner ear cell types. Various in vivo and in vitro approaches were combined to identify multiple pathways enhancing the regenerative potential of the inner ear in perinatal mice. However, regeneration of HCs in the adult mammalian cochlea resulting in restored function remains elusive. To date, molecular mechanisms resulting in the loss of the regenerative potential, specifically in the mammalian cochlea, are still under investigation. Similarly, the translational potential related to differentiation of stem cell aggregates being utilized in personalized medicine or cell replacement therapies remains to be determined.

Acknowledgements

Figures generated with Biorender.com. We thank members of J.W. Lab for the discussion of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abboud N, Fontbonne A, Watabe I, Tonetto A, Brezun JM, Feron F, Zine A, 2017. Culture conditions have an impact on the maturation of traceable, transplantable mouse embryonic stem cell-derived otic progenitor cells. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 11, 2629–2642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado DM, Hawkins RD, Bashiardes S, Veile RA, Ku YC, Powder KE, Spriggs MK, Speck JD, Warchol ME, Lovett M, 2011. An RNA interference-based screen of transcription factor genes identifies pathways necessary for sensory regeneration in the avian inner ear. J Neurosci 31, 4535–4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amprino R, Camosso M, 1959. On the role of the “apical ridge” in the development of the chick embryo limb bud. Acta Anat (Basel) 38, 280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold HJ, Müller M, Waldhaus J, Hahn H, Löwenheim H, 2010. A novel buoyancy technique optimizes simulated microgravity conditions for whole sensory organ culture in rotating bioreactors. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 16, 51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azadeh J, Song Z, Laureano AS, Toro-Ramos A, Kwan K, 2016. Initiating Differentiation in Immortalized Multipotent Otic Progenitor Cells. J Vis Exp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai H, Yang S, Xi C, Wang X, Xu J, Weng M, Zhao R, Jiang L, Gao X, Bing J, Zhang M, Zhang X, Han Z, Zeng S, 2021. Signaling pathways (Notch, Wnt, Bmp and Fgf) have additive effects on hair cell regeneration in the chick basilar papilla after streptomycin injury in vitro: Additive effects of signaling pathways on hair cell regeneration. Hear Res 401, 108161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baxendale S, Whitfield TT, 2016. Methods to study the development, anatomy, and function of the zebrafish inner ear across the life course. Methods Cell Biol 134, 165–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benkafadar N, Janesick A, Scheibinger M, Ling AH, Jan TA, Heller S, 2021. Transcriptomic characterization of dying hair cells in the avian cochlea. Cell Rep 34, 108902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt KA, Liberman MC, Nadol JB, 2001. Morphometric analysis of age-related changes in the human basilar membrane. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 110, 1147–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok J, Bronner-Fraser M, Wu DK, 2005. Role of the hindbrain in dorsoventral but not anteroposterior axial specification of the inner ear. Development 132, 2115–2124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok J, Chang W, Wu DK, 2007a. Patterning and morphogenesis of the vertebrate inner ear. Int J Dev Biol 51, 521–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok J, Dolson DK, Hill P, Ruther U, Epstein DJ, Wu DK, 2007b. Opposing gradients of Gli repressor and activators mediate Shh signaling along the dorsoventral axis of the inner ear. Development 134, 1713–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok J, Zenczak C, Hwang CH, Wu DK, 2013. Auditory ganglion source of Sonic hedgehog regulates timing of cell cycle exit and differentiation of mammalian cochlear hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110, 13869–13874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramhall NF, Shi F, Arnold K, Hochedlinger K, Edge AS, 2014. Lgr5-positive supporting cells generate new hair cells in the postnatal cochlea. Stem Cell Reports 2, 311–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calses PC, Crawford JJ, Lill JR, Dey A, 2019. Hippo Pathway in Cancer: Aberrant Regulation and Therapeutic Opportunities. Trends Cancer 5, 297–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpena NT, Chang SY, Abueva CDG, Jung JY, Lee MY, 2021. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells into a putative hair cell-progenitor cells via co-culture with HEI-OC1 cells. Sci Rep 11, 13893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai R, Kuo B, Wang T, Liaw EJ, Xia A, Jan TA, Liu Z, Taketo MM, Oghalai JS, Nusse R, Zuo J, Cheng AG, 2012. Wnt signaling induces proliferation of sensory precursors in the postnatal mouse cochlea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109, 8167–8172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai R, Xia A, Wang T, Jan TA, Hayashi T, Bermingham-McDonogh O, Cheng AG, 2011. Dynamic expression of Lgr5, a Wnt target gene, in the developing and mature mouse cochlea. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 12, 455–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Hong F, Zhang C, Li L, Wang C, Shi H, Fu Y, Wang J, 2018. Differentiation and transplantation of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived otic epithelial progenitors in mouse cochlea. Stem Cell Res Ther 9, 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JR, Tang ZH, Zheng J, Shi HS, Ding J, Qian XD, Zhang C, Chen JL, Wang CC, Li L, Chen JZ, Yin SK, Shao JZ, Huang TS, Chen P, Guan MX, Wang JF, 2016. Effects of genetic correction on the differentiation of hair cell-like cells from iPSCs with MYO15A mutation. Cell Death Differ 23, 1347–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Johnson JE, Zoghbi HY, Segil N, 2002. The role of Math1 in inner ear development: Uncoupling the establishment of the sensory primordium from hair cell fate determination. Development 129, 2495–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Segil N, 1999. p27(Kip1) links cell proliferation to morphogenesis in the developing organ of Corti. Development 126, 1581–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Johnson SL, Marcotti W, Andrews PW, Moore HD, Rivolta MN, 2009. Human fetal auditory stem cells can be expanded in vitro and differentiate into functional auditory neurons and hair cell-like cells. Stem Cells 27, 1196–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Jongkamonwiwat N, Abbas L, Eshtan SJ, Johnson SL, Kuhn S, Milo M, Thurlow JK, Andrews PW, Marcotti W, Moore HD, Rivolta MN, 2012. Restoration of auditory evoked responses by human ES-cell-derived otic progenitors. Nature 490, 278–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Yang Y, Luo L, Xu L, Liu B, Jiang G, Hu X, Zeng Y, Wang Z, 2020. An iPSC line (TYWHSTi002-A) derived from a patient with Pendred syndrome caused by compound heterozygous mutations in the SLC26A4 gene. Stem Cell Res 47, 101919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Lu X, Guo L, Ni W, Zhang Y, Zhao L, Wu L, Sun S, Zhang S, Tang M, Li W, Chai R, Li H, 2017. Hedgehog Signaling Promotes the Proliferation and Subsequent Hair Cell Formation of Progenitor Cells in the Neonatal Mouse Cochlea. Front Mol Neurosci 10, 426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SI, Jo ER, Song H, 2021. Mitophagy Impairment Aggravates Cisplatin-Induced Ototoxicity. Biomed Res Int 2021, 5590973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clevers H, 2006. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell 127, 469–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin JT, Cotanche DA, 1988. Regeneration of sensory hair cells after acoustic trauma. Science 240, 1772–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa A, Sanchez-Guardado L, Juniat S, Gale JE, Daudet N, Henrique D, 2015. Generation of sensory hair cells by genetic programming with a combination of transcription factors. Development 142, 1948–1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox BC, Chai R, Lenoir A, Liu Z, Zhang L, Nguyen DH, Chalasani K, Steigelman KA, Fang J, Rubel EW, Cheng AG, Zuo J, 2014. Spontaneous hair cell regeneration in the neonatal mouse cochlea in vivo. Development 141, 816–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabdoub A, Donohue MJ, Brennan A, Wolf V, Montcouquiol M, Sassoon DA, Hseih JC, Rubin JS, Salinas PC, Kelley MW, 2003. Wnt signaling mediates reorientation of outer hair cell stereociliary bundles in the mammalian cochlea. Development 130, 2375–2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daudet N, Lewis J, 2005. Two contrasting roles for Notch activity in chick inner ear development: specification of prosensory patches and lateral inhibition of hair-cell differentiation. Development 132, 541–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey A, Varelas X, Guan KL, 2020. Targeting the Hippo pathway in cancer, fibrosis, wound healing and regenerative medicine. Nat Rev Drug Discov 19, 480–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhukhwa A, Al Aameri RFH, Sheth S, Mukherjea D, Rybak L, Ramkumar V, 2021. Regulator of G protein signaling 17 represents a novel target for treating cisplatin induced hearing loss. Sci Rep 11, 8116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diensthuber M, Zecha V, Wagenblast J, Arnhold S, Edge AS, Stöver T, 2014. Spiral ganglion stem cells can be propagated and differentiated into neurons and glia. Biores Open Access 3, 88–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, Tang Z, Chen J, Shi H, Wang C, Zhang C, Li L, Chen P, Wang J, 2016. Induction of differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into functional hair-cell-like cells in the absence of stromal cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 81, 208–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Peng T, Wu W, Tan D, Liu X, Xie D, 2019. Efficient introduction of an isogenic homozygous mutation to induced pluripotent stem cells from a hereditary hearing loss family using CRISPR/Cas9 and single-stranded donor oligonucleotides. J Int Med Res 47, 1717–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver EC, Sillers L, Coate TM, Rose MF, Kelley MW, 2013. The Atoh1-lineage gives rise to hair cells and supporting cells within the mammalian cochlea. Dev Biol 376, 86–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulon D, Papal S, Patni P, Cortese M, Vincent PF, Tertrais M, Emptoz A, Tlili A, Bouleau Y, Michel V, Delmaghani S, Aghaie A, Pepermans E, Alegria-Prevot O, Akil O, Lustig L, Avan P, Safieddine S, Petit C, El-Amraoui A, 2018. Clarin-1 gene transfer rescues auditory synaptopathy in model of Usher syndrome. J Clin Invest 128, 3382–3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ealy M, Ellwanger DC, Kosaric N, Stapper AP, Heller S, 2016. Single-cell analysis delineates a trajectory toward the human early otic lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, 8508–8513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Amraoui A, Sahly I, Picaud S, Sahel J, Abitbol M, Petit C, 1996. Human Usher 1B/mouse shaker-1: the retinal phenotype discrepancy explained by the presence/absence of myosin VIIA in the photoreceptor cells. Hum Mol Genet 5, 1171–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis K, Driver EC, Okano T, Lemons A, Kelley MW, 2019. GSK3 regulates hair cell fate in the developing mammalian cochlea. Dev Biol 453, 191–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emptoz A, Michel V, Lelli A, Akil O, Boutet de Monvel J, Lahlou G, Meyer A, Dupont T, Nouaille S, Ey E, Franca de Barros F, Beraneck M, Dulon D, Hardelin JP, Lustig L, Avan P, Petit C, Safieddine S, 2017. Local gene therapy durably restores vestibular function in a mouse model of Usher syndrome type 1G. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, 9695–9700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooq R, Hussain K, Tariq M, Farooq A, Mustafa M, 2020. CRISPR/Cas9: targeted genome editing for the treatment of hereditary hearing loss. J Appl Genet 61, 51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis SP, Cunningham LL, 2017. Non-autonomous Cellular Responses to Ototoxic Drug-Induced Stress and Death. Front Cell Neurosci 11, 252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda H, Takahashi J, Watanabe K, Hayashi H, Morizane A, Koyanagi M, Sasai Y, Hashimoto N, 2006. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting-based purification of embryonic stem cell-derived neural precursors averts tumor formation after transplantation. Stem Cells 24, 763–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli GG, Carrara M, Yuan WC, Valdes-Quezada C, Gurung B, Pepe-Mooney B, Zhang T, Geeven G, Gray NS, de Laat W, Calogero RA, Camargo FD, 2015. YAP Drives Growth by Controlling Transcriptional Pause Release from Dynamic Enhancers. Mol Cell 60, 328–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD-Hearing-Loss-Collaborators, 2021. Hearing loss prevalence and years lived with diability, 1990–2019: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 397, 996–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson F, Walsh J, Mburu P, Varela A, Brown KA, Antonio M, Beisel KW, Steel KP, Brown SD, 1995. A type VII myosin encoded by the mouse deafness gene shaker-1. Nature 374, 62–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girod DA, Tucci DL, Rubel EW, 1991. Anatomical correlates of functional recovery in the avian inner ear following aminoglycoside ototoxicity. Laryngoscope 101, 1139–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnedeva K, Hudspeth AJ, Segil N, 2018. Three-dimensional Organotypic Cultures of Vestibular and Auditory Sensory Organs. J Vis Exp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnedeva K, Wang X, McGovern MM, Barton M, Tao L, Trecek T, Monroe TO, Llamas J, Makmura W, Martin JF, Groves AK, Warchol M, Segil N, 2020. Organ of Corti size is governed by Yap/Tead-mediated progenitor self-renewal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117, 13552–13561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokcan MK, Mulazimoglu S, Ocak E, Can P, Caliskan M, Besalti O, Dizbay Sak S, Kaygusuz G, 2016. Study of mouse induced pluripotent stem cell transplantation intoWistar albino rat cochleae after hair cell damage. Turk J Med Sci 46, 1603–1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves AC, Towers ER, Haq N, Porco JA, Pelletier J, Dawson SJ, Gale JE, 2019. Drug-induced Stress Granule Formation Protects Sensory Hair Cells in Mouse Cochlear Explants During Ototoxicity. Sci Rep 9, 12501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubbels SP, Woessner DW, Mitchell JC, Ricci AJ, Brigande JV, 2008. Functional auditory hair cells produced in the mammalian cochlea by in utero gene transfer. Nature 455, 537–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunewardene N, Bergen NV, Crombie D, Needham K, Dottori M, Nayagam BA, 2014. Directing human induced pluripotent stem cells into a neurosensory lineage for auditory neuron replacement. Biores Open Access 3, 162–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn H, Müller M, Löwenheim H, 2008. Whole organ culture of the postnatal sensory inner ear in simulated microgravity. J Neurosci Methods 171, 60–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque KD, Pandey AK, Kelley MW, Puligilla C, 2015. Culture of embryonic mouse cochlear explants and gene transfer by electroporation. J Vis Exp, 52260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoya M, Fujioka M, Sone T, Okamoto S, Akamatsu W, Ukai H, Ueda HR, Ogawa K, Matsunaga T, Okano H, 2017. Cochlear Cell Modeling Using Disease-Specific iPSCs Unveils a Degenerative Phenotype and Suggests Treatments for Congenital Progressive Hearing Loss. Cell Rep 18, 68–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Ulfendahl M, Olivius NP, 2004. Central migration of neuronal tissue and embryonic stem cells following transplantation along the adult auditory nerve. Brain Res 1026, 68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Song J, He C, Cai X, Yuan K, Mei L, Feng Y, 2021. Genetic insights, disease mechanisms, and biological therapeutics for Waardenburg syndrome. Gene Ther. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll MA, Malloy EA, Caster LE, Holland EM, Xu Z, Zallocchi M, Currier D, Liu H, He DZZ, Min J, Chen T, Zuo J, Teitz T, 2020. BRAF inhibition protects against hearing loss in mice. Sci Adv 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa M, Ohnishi H, Skerleva D, Sakamoto T, Yamamoto N, Hotta A, Ito J, Nakagawa T, 2017. Transplantation of neurons derived from human iPS cells cultured on collagen matrix into guinea-pig cochleae. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 11, 1766–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanchenko MV, Hanlon KS, Hathaway DM, Klein AJ, Peters CW, Li Y, Tamvakologos PI, Nammour J, Maguire CA, Corey DP, 2021. AAV-S: A versatile capsid variant for transduction of mouse and primate inner ear. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 21, 382–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumikawa M, Batts SA, Miyazawa T, Swiderski DL, Raphael Y, 2008. Response of the flat cochlear epithelium to forced expression of Atoh1. Hear Res 240, 52–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izumikawa M, Minoda R, Kawamoto K, Abrashkin KA, Swiderski DL, Dolan DF, Brough DE, Raphael Y, 2005. Auditory hair cell replacement and hearing improvement by Atoh1 gene therapy in deaf mammals. Nat Med 11, 271–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacques BE, Puligilla C, Weichert RM, Ferrer-Vaquer A, Hadjantonakis AK, Kelley MW, Dabdoub A, 2012. A dual function for canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in the developing mammalian cochlea. Development 139, 4395–4404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janesick A, Scheibinger M, Benkafadar N, Kirti S, Ellwanger DC, Heller S, 2021. Cell-type identity of the avian cochlea. Cell Rep 34, 108900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jat PS, Noble MD, Ataliotis P, Tanaka Y, Yannoutsos N, Larsen L, Kioussis D, 1991. Direct derivation of conditionally immortal cell lines from an H-2Kb-tsA58 transgenic mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88, 5096–5100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon SJ, Fujioka M, Kim SC, Edge AS, 2011. Notch signaling alters sensory or neuronal cell fate specification of inner ear stem cells. J Neurosci 31, 8351–8358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon SJ, Oshima K, Heller S, Edge AS, 2007. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells are progenitors in vitro for inner ear hair cells. Mol Cell Neurosci 34, 59–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong M, O’Reilly M, Kirkwood NK, Al-Aama J, Lako M, Kros CJ, Armstrong L, 2018. Generating inner ear organoids containing putative cochlear hair cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Death Dis 9, 922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Romero-Carvajal A, Haug JS, Seidel CW, Piotrowski T, 2014. Gene-expression analysis of hair cell regeneration in the zebrafish lateral line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, E1383–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Chacko L, Sergi C, Eberharter T, Dudas J, Rask-Andersen H, Hoermann R, Fritsch H, Fischer N, Glueckert R, Schrott-Fischer A, 2020. Early appearance of key transcription factors influence the spatiotemporal development of the human inner ear. Cell Tissue Res 379, 459–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JM, Montcouquiol M, Dabdoub A, Woods C, Kelley MW, 2006. Inhibitors of differentiation and DNA binding (Ids) regulate Math1 and hair cell formation during the development of the organ of Corti. J Neurosci 26, 550–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinec GM, Webster P, Lim DJ, Kalinec F, 2003. A cochlear cell line as an in vitro system for drug ototoxicity screening. Audiol Neurootol 8, 177–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastan N, Gnedeva K, Alisch T, Petelski AA, Huggins DJ, Chiaravalli J, Aharanov A, Shakked A, Tzahor E, Nagiel A, Segil N, Hudspeth AJ, 2021. Small-molecule inhibition of Lats kinases may promote Yap-dependent proliferation in postmitotic mammalian tissues. Nat Commun 12, 3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kather M, Koitzsch S, Breit B, Plontke S, Kammerer B, Liebau A, 2021. Metabolic reprogramming of inner ear cell line HEI-OC1 after dexamethasone application. Metabolomics 17, 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamoto K, Yagi M, Stover T, Kanzaki S, Raphael Y, 2003. Hearing and hair cells are protected by adenoviral gene therapy with TGF-beta1 and GDNF. Mol Ther 7, 484–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieny M, 1959. [Role of the mesoderm in the development of the limb bud in the chick embryo]. C R Hebd Seances Acad Sci 249, 1571–1573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan AE, Ahituv N, Fuchs H, Balling R, Avraham KB, Steel KP, Hrabé de Angelis M, 2001. The Notch ligand Jagged1 is required for inner ear sensory development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98, 3873–3878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler KR, Mikosz AM, Molosh AI, Patel D, Hashino E, 2013. Generation of inner ear sensory epithelia from pluripotent stem cells in 3D culture. Nature 500, 217–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler KR, Nie J, Longworth-Mills E, Liu XP, Lee J, Holt JR, Hashino E, 2017. Generation of inner ear organoids containing functional hair cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 35, 583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koleilat A, Dugdale JA, Christenson TA, Bellah JL, Lambert AM, Masino MA, Ekker SC, Schimmenti LA, 2020. L-type voltage-gated calcium channel agonists mitigate hearing loss and modify ribbon synapse morphology in the zebrafish model of Usher syndrome type 1. Dis Model Mech 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopke RD, Liu W, Gabaizadeh R, Jacono A, Feghali J, Spray D, Garcia P, Steinman H, Malgrange B, Ruben RJ, Rybak L, Van de Water TR, 1997. Use of organotypic cultures of Corti’s organ to study the protective effects of antioxidant molecules on cisplatin-induced damage of auditory hair cells. Am J Otol 18, 559–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota M, Scheibinger M, Jan TA, Heller S, 2021. Greater epithelial ridge cells are the principal organoid-forming progenitors of the mouse cochlea. Cell Rep 34, 108646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan KY, Shen J, Corey DP, 2015. C-MYC transcriptionally amplifies SOX2 target genes to regulate self-renewal in multipotent otic progenitor cells. Stem Cell Reports 4, 47–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahlou H, Nivet E, Lopez-Juarez A, Fontbonne A, Assou S, Zine A, 2018. Enriched Differentiation of Human Otic Sensory Progenitor Cells Derived From Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Front Mol Neurosci 11, 452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landegger LD, Dilwali S, Stankovic KM, 2017. Neonatal Murine Cochlear Explant Technique as an In Vitro Screening Tool in Hearing Research. J Vis Exp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanford PJ, Lan Y, Jiang R, Lindsell C, Weinmaster G, Gridley T, Kelley MW, 1999. Notch signalling pathway mediates hair cell development in mammalian cochlea. Nat Genet 21, 289–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson VD, Williams DW, Henderson WG, Luethke LE, Beck LB, Noffsinger D, Wilson RH, Dobie RA, Haskell GB, Bratt GW, Shanks JE, Stelmachowicz P, Studebaker GA, Boysen AE, Donahue A, Canalis R, Fausti SA, Rappaport BZ, 2000. Efficacy of 3 commonly used hearing aid circuits: A crossover trial. NIDCD/VA Hearing Aid Clinical Trial Group. JAMA 284, 1806–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Liu H, Heller S, 2003a. Pluripotent stem cells from the adult mouse inner ear. Nat Med 9, 1293–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Roblin G, Liu H, Heller S, 2003b. Generation of hair cells by stepwise differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 13495–13500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Li G, Chien JS, Raft S, Zhang H, Chiang C, Frenz DA, 2002. Sonic hedgehog regulates otic capsule chondrogenesis and inner ear development in the mouse embryo. Dev Biol 248, 240–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Lillywhite J, Zhu W, Huang Z, Clark AM, Gosstola N, Maguire CT, Dykxhoorn D, Chen ZY, Yang J, 2021. Generation and Genetic Correction of USH2A c.2299delG Mutation in Patient-Derived Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Genes (Basel) 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Owen T, Zhang L, Zuo J, 2010. Dynamic expression pattern of Sonic hedgehog in developing cochlear spiral ganglion neurons. Dev Dyn 239, 1674–1683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Juarez A, Lahlou H, Ripoll C, Cazals Y, Brezun JM, Wang Q, Edge A, Zine A, 2019. Engraftment of Human Stem Cell-Derived Otic Progenitors in the Damaged Cochlea. Mol Ther 27, 1101–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löwenheim H, Furness DN, Kil J, Zinn C, Gültig K, Fero ML, Frost D, Gummer AW, Roberts JM, Rubel EW, Hackney CM, Zenner HP, 1999. Gene disruption of p27(Kip1) allows cell proliferation in the postnatal and adult organ of corti. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96, 4084–4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maass JC, Gu R, Basch ML, Waldhaus J, Lopez EM, Xia A, Oghalai JS, Heller S, Groves AK, 2015. Changes in the regulation of the Notch signaling pathway are temporally correlated with regenerative failure in the mouse cochlea. Front Cell Neurosci 9, 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka AJ, Morrissey ZD, Zhang C, Homma K, Belmadani A, Miller CA, Chadly DM, Kobayashi S, Edelbrock AN, Tanaka-Matakatsu M, Whitlon DS, Lyass L, McGuire TL, Stupp SI, Kessler JA, 2017. Directed Differentiation of Human Embryonic Stem Cells Toward Placode-Derived Spiral Ganglion-Like Sensory Neurons. Stem Cells Transl Med 6, 923–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattei C, Lim R, Drury H, Nasr B, Li Z, Tadros MA, D’Abaco GM, Stok KS, Nayagam BA, Dottori M, 2019. Generation of Vestibular Tissue-Like Organoids From Human Pluripotent Stem Cells Using the Rotary Cell Culture System. Front Cell Dev Biol 7, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern MM, Zhou L, Randle MR, Cox BC, 2018. Spontaneous Hair Cell Regeneration Is Prevented by Increased Notch Signaling in Supporting Cells. Front Cell Neurosci 12, 120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean WJ, McLean DT, Eatock RA, Edge AS, 2016. Distinct capacity for differentiation to inner ear cell types by progenitor cells of the cochlea and vestibular organs. Development 143, 4381–4393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean WJ, Yin X, Lu L, Lenz DR, McLean D, Langer R, Karp JM, Edge ASB, 2017. Clonal Expansion of Lgr5-Positive Cells from Mammalian Cochlea and High-Purity Generation of Sensory Hair Cells. Cell Rep 18, 1917–1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez L, Trecek T, Gopalakrishnan S, Tao L, Markowitz AL, Yu HV, Wang X, Llamas J, Huang C, Lee J, Kalluri R, Ichida J, Segil N, 2020. Generation of inner ear hair cells by direct lineage conversion of primary somatic cells. Elife 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizutari K, Fujioka M, Hosoya M, Bramhall N, Okano HJ, Okano H, Edge AS, 2013. Notch inhibition induces cochlear hair cell regeneration and recovery of hearing after acoustic trauma. Neuron 77, 58–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morest DK, Cotanche DA, 2004. Regeneration of the inner ear as a model of neural plasticity. J Neurosci Res 78, 455–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima Y, 2015. Signaling regulating inner ear development: cell fate determination, patterning, morphogenesis, and defects. Congenit Anom (Kyoto) 55, 17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayagam BA, Edge AS, Needham K, Hyakumura T, Leung J, Nayagam DA, Dottori M, 2013. An in vitro model of developmental synaptogenesis using cocultures of human neural progenitors and cochlear explants. Stem Cells Dev 22, 901–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie J, Hashino E, 2020. Generation of inner ear organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Methods Cell Biol 159, 303–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie J, Koehler KR, Hashino E, 2017. Directed Differentiation of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells Into Inner Ear Sensory Epithelia in 3D Culture. Methods Mol Biol 1597, 67–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nist-Lund CA, Pan B, Patterson A, Asai Y, Chen T, Zhou W, Zhu H, Romero S, Resnik J, Polley DB, Geleoc GS, Holt JR, 2019. Improved TMC1 gene therapy restores hearing and balance in mice with genetic inner ear disorders. Nat Commun 10, 236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan ME, Song Y, Greenhouse R, Lin R, Perez A, Atkinson PJ, MacDonald JP, Siddiqui Z, Lagasca D, Comstock K, Huth ME, Cheng AG, Ricci AJ, 2020. Dissociating antibacterial from ototoxic effects of gentamicin C-subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117, 32423–32432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oesterle EC, Tsue TT, Reh TA, Rubel EW, 1993. Hair-cell regeneration in organ cultures of the postnatal chicken inner ear. Hear Res 70, 85–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogier JM, Burt RA, Drury HR, Lim R, Nayagam BA, 2019. Organotypic Culture of Neonatal Murine Inner Ear Explants. Front Cell Neurosci 13, 170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi H, Skerleva D, Kitajiri S, Sakamoto T, Yamamoto N, Ito J, Nakagawa T, 2015. Limited hair cell induction from human induced pluripotent stem cells using a simple stepwise method. Neurosci Lett 599, 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omichi R, Shibata SB, Morton CC, Smith RJH, 2019. Gene therapy for hearing loss. Hum Mol Genet 28, R65–R79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima K, Grimm CM, Corrales CE, Senn P, Martinez Monedero R, Géléoc GS, Edge A, Holt JR, Heller S, 2007. Differential distribution of stem cells in the auditory and vestibular organs of the inner ear. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 8, 18–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima K, Shin K, Diensthuber M, Peng AW, Ricci AJ, Heller S, 2010. Mechanosensitive hair cell-like cells from embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell 141, 704–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou HC, Cunningham LL, Francis SP, Brandon CS, Simon JA, Raible DW, Rubel EW, 2009. Identification of FDA-approved drugs and bioactives that protect hair cells in the zebrafish (Danio rerio) lateral line and mouse (Mus musculus) utricle. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 10, 191–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouji Y, Ishizaka S, Nakamura-Uchiyama F, Yoshikawa M, 2012. In vitro differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into inner ear hair cell-like cells using stromal cell conditioned medium. Cell Death Dis 3, e314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmgren B, Jiao Y, Novozhilova E, Stupp SI, Olivius P, 2012. Survival, migration and differentiation of mouse tau-GFP embryonic stem cells transplanted into the rat auditory nerve. Exp Neurol 235, 599–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perl K, Shamir R, Avraham KB, 2018. Computational analysis of mRNA expression profiling in the inner ear reveals candidate transcription factors associated with proliferation, differentiation, and deafness. Hum Genomics 12, 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perny M, Solyga M, Grandgirard D, Roccio M, Leib SL, Senn P, 2017. Streptococcus pneumoniae-induced ototoxicity in organ of Corti explant cultures. Hear Res 350, 100–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett SB, Raible DW, 2019. Water Waves to Sound Waves: Using Zebrafish to Explore Hair Cell Biology. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 20, 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regala C, Duan M, Zou J, Salminen M, Olivius P, 2005. Xenografted fetal dorsal root ganglion, embryonic stem cell and adult neural stem cell survival following implantation into the adult vestibulocochlear nerve. Exp Neurol 193, 326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccomagno MM, Martinu L, Mulheisen M, Wu DK, Epstein DJ, 2002. Specification of the mammalian cochlea is dependent on Sonic hedgehog. Genes Dev 16, 2365–2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivolta MN, Grix N, Lawlor P, Ashmore JF, Jagger DJ, Holley MC, 1998. Auditory hair cell precursors immortalized from the mammalian inner ear. Proc Biol Sci 265, 1595–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roccio M, Hahnewald S, Perny M, Senn P, 2015. Cell cycle reactivation of cochlear progenitor cells in neonatal FUCCI mice by a GSK3 small molecule inhibitor. Sci Rep 5, 17886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roccio M, Perny M, Ealy M, Widmer HR, Heller S, Senn P, 2018. Molecular characterization and prospective isolation of human fetal cochlear hair cell progenitors. Nat Commun 9, 4027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronaghi M, Nasr M, Ealy M, Durruthy-Durruthy R, Waldhaus J, Diaz GH, Joubert LM, Oshima K, Heller S, 2014. Inner ear hair cell-like cells from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 23, 1275–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousset F, B C Kokje V, Sipione R, Schmidbauer D, Nacher-Soler G, Ilmjärv S, Coelho M, Fink S, Voruz F, El Chemaly A, Marteyn A, Löwenheim H, Krause KH, Müller M, Glückert R, Senn P, 2020a. Intrinsically Self-renewing Neuroprogenitors From the A/J Mouse Spiral Ganglion as Virtually Unlimited Source of Mature Auditory Neurons. Front Cell Neurosci 14, 395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousset F, Nacher-Soler G, Coelho M, Ilmjarv S, Kokje VBC, Marteyn A, Cambet Y, Perny M, Roccio M, Jaquet V, Senn P, Krause KH, 2020b. Redox activation of excitatory pathways in auditory neurons as mechanism of age-related hearing loss. Redox Biol 30, 101434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolf MA, Andreeva A, Kozlowski MM, Kim CE, Moskowitz BA, Anaya-Rocha A, Kelley MW, Corwin JT, 2020. YAP Mediates Hair Cell Regeneration in Balance Organs of Chickens, But LATS Kinases Suppress Its Activity in Mice. J Neurosci 40, 3915–3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn P, Mina A, Volkenstein S, Kranebitter V, Oshima K, Heller S, 2020. Progenitor Cells from the Adult Human Inner Ear. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 303, 461–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi F, Corrales CE, Liberman MC, Edge AS, 2007. BMP4 induction of sensory neurons from human embryonic stem cells and reinnervation of sensory epithelium. Eur J Neurosci 26, 3016–3023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi F, Kempfle JS, Edge AS, 2012. Wnt-responsive Lgr5-expressing stem cells are hair cell progenitors in the cochlea. J Neurosci 32, 9639–9648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shone G, Raphael Y, Miller JM, 1991. Hereditary deafness occurring in cd/1 mice. Hear Res 57, 153–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobkowicz HM, Bereman B, Rose JE, 1975. Organotypic development of the organ of Corti in culture. J Neurocytol 4, 543–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son EJ, Ma JH, Ankamreddy H, Shin JO, Choi JY, Wu DK, Bok J, 2015. Conserved role of Sonic Hedgehog in tonotopic organization of the avian basilar papilla and mammalian cochlea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112, 3746–3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son EJ, Wu L, Yoon H, Kim S, Choi JY, Bok J, 2012. Developmental gene expression profiling along the tonotopic axis of the mouse cochlea. PLoS One 7, e40735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Q, Wang J, 2020. Effects of the lignan compound (+)-Guaiacin on hair cell survival by activating Wnt/beta-Catenin signaling in mouse cochlea. Tissue Cell 66, 101393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staecker H, Praetorius M, Baker K, Brough DE, 2007. Vestibular hair cell regeneration and restoration of balance function induced by math1 gene transfer. Otol Neurotol 28, 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang ZH, Chen JR, Zheng J, Shi HS, Ding J, Qian XD, Zhang C, Chen JL, Wang CC, Li L, Chen JZ, Yin SK, Huang TS, Chen P, Guan MX, Wang JF, 2016. Genetic Correction of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells From a Deaf Patient With MYO7A Mutation Results in Morphologic and Functional Recovery of the Derived Hair Cell-Like Cells. Stem Cells Transl Med 5, 561–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tateya T, Imayoshi I, Tateya I, Hamaguchi K, Torii H, Ito J, Kageyama R, 2013. Hedgehog signaling regulates prosensory cell properties during the basal-to-apical wave of hair cell differentiation in the mammalian cochlea. Development 140, 3848–3857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitz T, Fang J, Goktug AN, Bonga JD, Diao S, Hazlitt RA, Iconaru L, Morfouace M, Currier D, Zhou Y, Umans RA, Taylor MR, Cheng C, Min J, Freeman B, Peng J, Roussel MF, Kriwacki R, Guy RK, Chen T, Zuo J, 2018. CDK2 inhibitors as candidate therapeutics for cisplatin- and noise-induced hearing loss. J Exp Med 215, 1187–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AJ, Wu P, Raible DW, Rubel EW, Simon JA, Ou HC, 2015. Identification of small molecule inhibitors of cisplatin-induced hair cell death: results of a 10,000 compound screen in the zebrafish lateral line. Otol Neurotol 36, 519–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropitzsch A, Arnold H, Bassiouni M, Müller A, Eckhard A, Müller M, Löwenheim H, 2014. Assessing cisplatin-induced ototoxicity and otoprotection in whole organ culture of the mouse inner ear in simulated microgravity. Toxicol Lett 227, 203–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropitzsch A, Müller M, Paquet-Durand F, Mayer F, Kopp HG, Schrattenholz A, Müller A, Löwenheim H, 2019. Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase-1 (PARP1) Deficiency and Pharmacological Inhibition by Pirenzepine Protects From Cisplatin-Induced Ototoxicity Without Affecting Antitumor Efficacy. Front Cell Neurosci 13, 406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentini C, Szeto B, Kysar JW, Lalwani AK, 2020. Inner Ear Gene Delivery: Vectors and Routes. Hearing Balance Commun 18, 278–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddington CH, 1950. Processes of induction in the early development of the chick. Annee Biol 54, 711–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldhaus J, Cimerman J, Gohlke H, Ehrich M, Müller M, Löwenheim H, 2012. Stemness of the organ of Corti relates to the epigenetic status of Sox2 enhancers. PLoS One 7, e36066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters BJ, Lin W, Diao S, Brimble M, Iconaru LI, Dearman J, Goktug A, Chen T, Zuo J, 2014. High-throughput screening reveals alsterpaullone, 2-cyanoethyl as a potent p27Kip1 transcriptional inhibitor. PLoS One 9, e91173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warchol ME, Corwin JT, 1996. Regenerative proliferation in organ cultures of the avian cochlea: identification of the initial progenitors and determination of the latency of the proliferative response. J Neurosci 16, 5466–5477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei D, Levic S, Nie L, Gao WQ, Petit C, Jones EG, Yamoah EN, 2008. Cells of adult brain germinal zone have properties akin to hair cells and can be used to replace inner ear sensory cells after damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 21000–21005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen YH, Lin JN, Wu RS, Yu SH, Hsu CJ, Tseng GF, Wu HP, 2020. Otoprotective Effect of 2,3,4’,5-Tetrahydroxystilbene-2-. Molecules 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White PM, Doetzlhofer A, Lee YS, Groves AK, Segil N, 2006. Mammalian cochlear supporting cells can divide and trans-differentiate into hair cells. Nature 441, 984–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods C, Montcouquiol M, Kelley MW, 2004. Math1 regulates development of the sensory epithelium in the mammalian cochlea. Nat Neurosci 7, 1310–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Solanes P, Nist-Lund C, Spataro S, Shubina-Oleinik O, Marcovich I, Goldberg H, Schneider BL, Holt JR, 2021. Single and Dual Vector Gene Therapy with AAV9-PHP.B Rescues Hearing in Tmc1 Mutant Mice. Mol Ther 29, 973–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Ueno H, Xu CY, Chen B, Weissman IL, Xu PX, 2017. Identification of mouse cochlear progenitors that develop hair and supporting cells in the organ of Corti. Nat Commun 8, 15046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto N, Tanigaki K, Tsuji M, Yabe D, Ito J, Honjo T, 2006. Inhibition of Notch/RBP-J signaling induces hair cell formation in neonate mouse cochleas. J Mol Med (Berl) 84, 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanconato F, Forcato M, Battilana G, Azzolin L, Quaranta E, Bodega B, Rosato A, Bicciato S, Cordenonsi M, Piccolo S, 2015. Genome-wide association between YAP/TAZ/TEAD and AP-1 at enhancers drives oncogenic growth. Nat Cell Biol 17, 1218–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G, Zhu K, Wei J, Jin Z, Duan M, 2011. Adeno-associated viral vector-mediated expression of NT4-ADNF-9 fusion gene protects against aminoglycoside-induced auditory hair cell loss in vitro. Acta Otolaryngol 131, 136–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G, Zhu Z, Zhu K, Wei J, Jing Y, Duan M, 2013. Therapeutic effect of adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated ADNF-9 expression on cochlea of kanamycin-deafened guinea pigs. Acta Otolaryngol 133, 1022–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu RZ, Li BS, Gao SS, Seo JH, Choi BM, 2021. Luteolin inhibits H. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol 25, 297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]