Abstract

An important goal of the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. initiative is the timely diagnosis of all people with HIV as early as possible after infection. To end the HIV epidemic, health departments were encouraged to propose new and innovative HIV testing strategies and improve the reach of existing programs. These activities were divided into 3 core strategies: expansion of routine screening in healthcare settings, locally tailored HIV testing initiatives in nonhealthcare settings, and specific efforts to increase the frequency of testing for individuals with increased potential for acquiring HIV. Because HIV testing is such a crucial part of the core activities of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s HIV prevention programs, there are many examples of evidence-based programs and best practices for HIV testing in both clinical and nonclinical settings. This article reviews the evidence base for these strategies and some of the activities proposed under the Diagnose pillar to achieve the goal of diagnosing all HIV infections as early as possible. All other Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. activities start with an awareness of HIV status, which is actually the indicator for which most health departments are closest to the proposed targets. There are both proven and emerging approaches to increasing HIV screening and increasing the frequency of HIV screening available. The Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. initiative provides the motivation, the resources, and a coordinated plan to bring them to scale.

BACKGROUND

Since 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recommended that adolescents and adults be screened for HIV infection in healthcare settings at least once in their lifetimes, as well as at least annual rescreening of individuals with increased potential for HIV acquisition.1,2 However, data from national surveys and HIV surveillance show that these recommendations have not been implemented fully.3–7 An important goal of the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. (EHE) initiative is the timely diagnosis of all people with HIV as early as possible after infection8,9; yet, the promise of routine testing has not been realized. A CDC analysis in 2019 using data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System5 assessed the percentage of adults tested for HIV in the U.S. nationwide, compared with the percentage in 50 counties and 7 states that are the focus of Phase 1 of the EHE initiative. This analysis validated that there is much work to be done to meet the 2006 recommendations because testing percentages were low overall and varied widely by jurisdiction, with rates of both ever and past-year testing being lowest in rural areas. A similar analysis of another nationally representative data source3 found that only 62.2% of persons who reported HIV-related behaviors in the past 12 months were ever tested for HIV, and the median interval since the last test in this group was 512 days (1.4 years). The local differences in observed HIV testing history suggest that to achieve national goals and end the HIV epidemic in the U.S., strategies to increase testing must be tailored to meet local needs.

This article provides a broad overview of the landscape of strategies that have been proposed by health departments (HDs) preparing to implement EHE. Other articles in this special supplement provide concrete examples of how these strategies are being implemented in specific jurisdictions. CDC has traditionally provided funding to HDs and directly to community-based organizations for HIV testing through a variety of cooperative agreements, which support both clinical and nonclinical HIV testing activities. A recent analysis10 found that from 2010 to 2017, tests directly funded by CDC accounted for roughly one third of all new HIV diagnoses annually. However, under EHE, CDC further emphasized the need to develop new and innovative HIV testing strategies as well as further expansion of the reach of existing HIV testing programs.8,9,11 The local jurisdictions have been encouraged to develop a mixture of testing options to make HIV testing both accessible and routine.

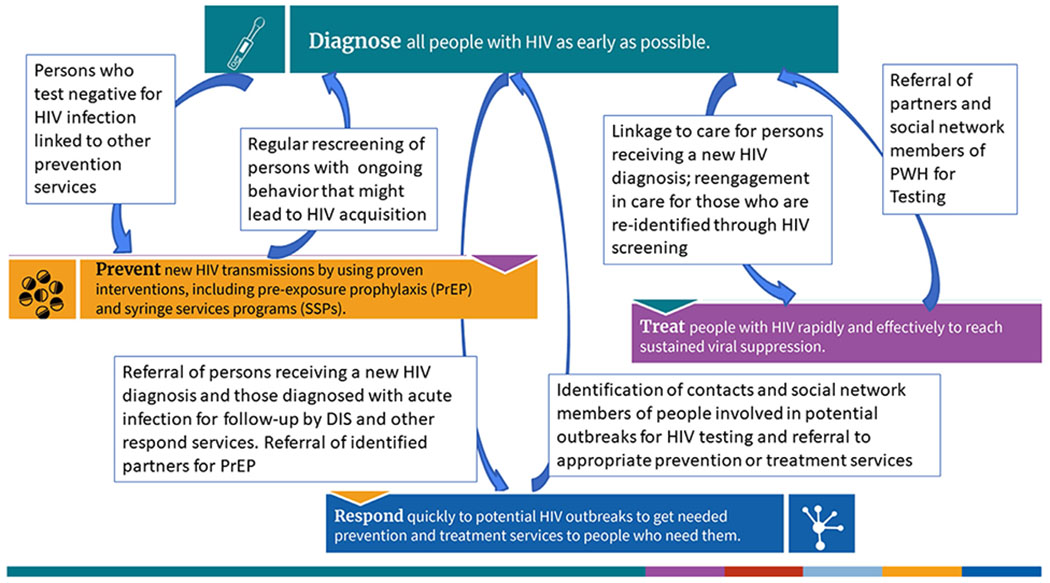

An HIV test is the first step to HIV medical care and treatment for those who receive a positive test result and provides a gateway to HIV prevention services such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for those who test negative but would benefit from PrEP. Thus, activities under the Diagnose pillar represent a jumping off point for other pillar activities. The Prevent, Treat, and Respond pillars are described in the introduction to this supplement.12 Figure 1 is similar to the graphical representation of a status-neutral approach to HIV prevention,13 by which an individual’s needs for prevention and care services are adequately addressed regardless of their HIV infection status. However, in the context of the EHE initiative, the figure highlights the way pillars (rather than individuals) are connected to create an integrated view of HIV prevention, care, treatment, and control. Strategies to expand access to HIV testing to anyone who needs it must incorporate tools to engage the next steps after an HIV test result is obtained. Figure 1 shows this by including not only prevention services to people who test negative but also integrating approaches to offer rescreening for HIV for individuals with increased potential for HIV acquisition. Likewise, a positive test result must be followed by linkage to HIV care and initiation of antiretroviral therapy, leading to viral suppression. For people with HIV who are not engaged in care, community testing strategies such as those implemented in East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana and described in this issue14 represent an opportunity to offer HIV care re-engagement to achieve viral suppression. The integrated approach also includes the role HIV care providers have in offering HIV tests, PrEP, and other prevention services to their patient’s sex or drug-using partners. A first positive test result is also a starting point for Respond pillar activities related to outbreak detection and cluster response15 because an investigation of clusters may identify a need for targeted testing strategies in communities with active HIV transmission.16–20 Better integration of activities related to the Diagnose pillar with the other pillars will be key to EHE.

Figure 1.

The integration of the 4 pillars of the initiative to End the HIV Epidemic in the U.S.

DIS, Disease Intervention Specialist; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; PWH, People with HIV; SSP, syringe services program.

The Ending the Epidemic CDC funding announcement11 provided recommendations to HDs to develop locally relevant and tailored programs for all pillars. Because HIV testing is such a crucial part of the core activities of CDC’s HIV prevention programs, there are many examples of evidence-based programs and best practices for HIV testing in both clinical and nonclinical settings. To end the HIV epidemic, HDs were encouraged to propose new and innovative HIV testing strategies and improve the reach of existing programs. These activities were divided into 3 core strategies: expansion of routine screening in institutional settings, locally tailored HIV testing initiatives in nonhealthcare settings, and specific efforts to increase the frequency of testing for people with ongoing potential for HIV acquisition.

STRATEGY 1: EXPAND OR IMPLEMENT ROUTINE OPT-OUT HIV SCREENING IN HEALTH CARE OR OTHER SETTINGS

Healthcare encounters provide critical opportunities to promote HIV screening. In addition to CDC’s 2006 recommendations to screen all individuals at least once in healthcare settings,1 in 2014 (updated in 2019), the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that clinicians screen for HIV infection in adolescents and adults aged 15–65 years.21 Younger adolescents and older adults who experience an increased potential for HIV acquisition should also be screened. This recommendation received a Grade A rating, which covers cost sharing for tests performed in clinical settings.

Although both CDC and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations provide strong incentives to promote routine screening in clinical settings, several reports have found lower than the desired uptake. In 2020, CDC analyzed HIV testing trends at visits to physicians’ offices, community health centers (CHCs), and emergency departments during 2009–2017 and found that HIV screening occurred at <1% of visits to physicians’ offices and in emergency departments and <3% at CHCs.6 These missed opportunities are critical to overcome if EHE goals are to be met.

Public health experts and health clinic professionals have identified several areas for improvement. Rizza et al.22 described several barriers, including competing clinical priorities, laws and regulations that support optin rather than opt-out testing, assumptions that behavioral risk–based screening is optimal, and third-party billing. Others23–25 have more recently suggested that coupling screenings for HIV with comprehensive care for other routine screenings, integrating screening into the normal clinical flow, being client driven, and using automated computer systems can greatly increase the uptake of healthcare screening.

To address these concerns, CDC and others are investing in systems and methods that can decrease the burden of screening on patients and clinicians, that make HIV testing less exceptional and stigmatized, and that increase uptake. A growing number of healthcare programs have explored the use of clinical decision support systems, which are computer-based information systems designed to help healthcare providers implement clinical guidelines at the point of care.26 Clinical decision support systems can generate specific patient assessments and evidence-based treatment recommendations on the basis of patient data and use an electronic medical record or electronic health record system to populate this information and make it accessible to patient care providers.

The use of clinical decision support systems has been shown to increase HIV screening by using patient data to identify patients eligible for HIV screening and alert or remind their healthcare providers to order HIV tests.27–32 There have been a variety of governmental efforts to expand these systems, by the CDC, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and their public health partners. The Public Health Institute of Metropolitan Chicago partnered with 7 healthcare systems in Illinois to implement routine HIV screening during 2013–2015, using support from the HHS Secretary’s Minority AIDS Initiative Fund’s Care and Prevention in the United States (CAPUS) program, and led by CDC.28 Public Health Institute of Metropolitan Chicago healthcare systems used this project to more fully implement routine HIV screening by integrating HIV screening orders and consent documentation into the electronic health record. The transformation of their systems led to a 46% increase in HIV tests performed during 2013–2016. CDC and the HRSA have also worked together to promote the provision of routine HIV screening in CHCs through Partnerships for Care (P4C), a program implemented during 2014–2017. P4C funded HDs and CHCs in jurisdictions funded by the HRSA’s Bureau of Primary Health Care.31 For example, within the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (MDPH), the P4C program demonstrated the improvements that can be made not only to HIV screening but also to linkage to medical care by moving from earlier models wherein testing, linkage, and care coordination operate as stand-alone programs to models that integrate these into routine, primary care clinical services. P4C CHC providers in MDPH used electronic health record data to generate lists of out-of-care patients, which they then reviewed with MDPH surveillance epidemiologists to identify opportunities to link these patients back to care. The P4C system fostered stronger public health–CHC partnerships and significantly improved MDPH’s capacity to link and re-engage people in HIV medical care.

There are also locally funded programs that have implemented improved systems for HIV screening. The Harris Health System in Houston, Texas implemented the Routine Universal Screening for HIV initiative in 2009 with funding from the Texas Department of State Health Services and the City of Houston.29 They provided standing orders for HIV testing for any patient receiving a blood draw unless the patient refused. This system led to an immediate increase in the percentage of patients ever tested for HIV and tested in the past year. In 2016, 35.4% of the >200,000 unique patients in Houston’s largest public safety-net healthcare system received an HIV test. Another example is the HIV on the Frontlines of Communities in the U.S. (FOCUS) program, launched in 2010 by Gilead Sciences, Inc. The goals of FOCUS are to facilitate electronic medical records modifications, data management, and continuous quality improvement to make HIV screening a routine practice in clinical and community settings. From the launch of the FOCUS program during 2010–2013, a total of 153 partnerships were developed in 10 cities,32 resulting in large increases in the number of people screened.

An EHE site in East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana provides another example.30 HHS Minority HIV/AIDS funds were used to invest $4.5 million in 3 jump-start sites to implement key foundational activities to accelerate progress toward EHE in their communities.12,30 Ochsner Medical Center in Baton Rouge used this opportunity to accelerate its opt-out HIV testing program in 2019; they and other hospitals in the area worked with electronic medical record providers to create a flag for testing so that triage nurses would be automatically notified when a patient is eligible (i.e., aged 13–64 years) to be tested. The program has been so successful that HIV screening is now a part of the day-to-day workflow.

In addition to traditional healthcare settings, there are other clinical settings into which HIV screening can and should be integrated. As part of the EHE initiative, CDC specifically recommended routine opt-out screening in jails. This recommendation is based on years of data33–38 showing that routine screening in these settings identifies previously undiagnosed infections and that routine screening at medical intake, in particular, can be effective at identifying undiagnosed HIV in individuals who otherwise may not access health care routinely. This strategy has been shown to be cost effective,38,39 and the cost per identified infection is actually lower than that in most other settings.40–43 CDC has developed guidance for developing HIV screening programs in correctional settings.44 In this issue, Hutchinson and colleagues45 provide an example of the impact of a jail screening program and not being able to maintain routine HIV screening in a jail in an EHE Phase 1 jurisdiction.

Likewise, better integration of HIV screening in sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics is needed. CDC’s HIV screening recommendations1 specifically highlight STD clinics as a healthcare setting in which routine screening should be implemented. CDC’s STD treatment guidelines also recommend that all individuals seeking evaluation or treatment for STDs be tested for HIV.46 Among CDC-funded testing sites, STD clinics diagnose more new HIV infections annually than any other healthcare setting.47,48 A CDC study of HIV testing in a sample of the U.S. population49 found that there are many missed opportunities for better integration of HIV and STD screening. Methods to better integrate HIV screening into STD clinic flow are needed and are specifically being piloted in the EHE jump-start sites.50

STRATEGY 2: DEVELOP LOCALLY TAILORED HIV TESTING PROGRAMS TO REACH PEOPLE IN NONHEALTHCARE SETTINGS

HIV Self-Testing

Self-testing allows people to take an HIV test and find out their results in their own home or other private location. Although HIV self-tests are available for retail purchase by consumers, CDC encourages HDs to consider HIV self-testing as an additional testing strategy to reach people most affected by HIV. There are 2 types of HIV self-tests: rapid self-tests and mail-in self-tests.

A rapid self-test is done entirely at home or in a private location and can produce results within 20 minutes. The CDC-funded evaluation of HIV Self-Testing Among Men who have sex with men Project (eSTAMP)51 was a national RCT designed to evaluate the public health benefits of mailing rapid self-tests to internet-recruited gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) in the U.S., conducted during 2015–2016. Men who were mailed HIV self-tests tested themselves more frequently and identified significantly more prevalent HIV infections than men in the control arm. Importantly, the study did not find any increase in sexual behaviors with potential for HIV acquisition reported by participants who received HIV self-tests. Furthermore, the eSTAMP study allowed participants to share HIV self-tests with members of their social network, resulting in many more people becoming aware of their HIV infection. There are many examples of HD programs that have successfully distributed HIV self-tests.52–55 As part of CDC’s HIV Capacity Building Assistance for Health Departments, the New York City Department of Health provided a description of their rapid self-test distribution programs and considerations for other HDs that want to set up similar programs.56 A compendium of rapid self-test protocols collected from both HDs and community-based organizations is available from the Denver Prevention Training Centers,57 and a summary of these protocols and lessons learned will soon be available on the CDC Capacity Building website.58

In addition to rapid home self-tests, there are many publicly available options for mail-in HIV self-tests. A mail-in self-test includes a specimen collection kit that contains supplies to collect dried blood from a fingerstick at home. The sample is then sent to a laboratory for testing, and the results are provided by a healthcare provider. Mail-in self-tests can be ordered through various online merchant sites. Healthcare providers can also order a mail-in self-test for their patients. One benefit of mail-in self-tests is the option to couple collection of samples for HIV and other STDs. Some laboratories have validated protocols for testing home-collected samples for the panel of tests required for those initiating or continuing PrEP. The National Coalition of STD directors has developed a series of webinars59 covering a variety of issues related to HIV and STD testing of self-collected samples. In this issue, Fistonich et al.60 describe the program GetCheckedDC, which includes both distributions of rapid HIV self-tests and mail-in sample collection kits for testing for gonorrhea and chlamydia.

HIV Testing in Retail Pharmacies

Rapid self-tests and commercially available mail-in self-tests for HIV can both be purchased at retail pharmacies. However, there are benefits to pharmacist-led testing in these settings, including the possibility for active linkage to HIV care. Another demonstration project from Virginia, funded under the CAPUS program during 2014–2016,61 showed that a public–private partnership between the HD and a retail pharmacy chain could effectively implement the offer of HIV screening in pharmacies, identifying individuals who had never previously tested and new HIV infections, and could through the HD collaboration provide successful linkage to HIV medical care. As with HIV self-testing, this project built on previously funded CDC research piloting HIV screening in retail pharmacies,62,63 and CDC has developed training for HDs and community-based organizations seeking to partner with retail pharmacies to conduct HIV testing.64

Mobile/Outreach Testing Strategies

Mobile/outreach testing has been a cornerstone of HIV prevention for decades. Since the approval of the first rapid HIV test for use outside a laboratory, CDC has sponsored a variety of demonstration projects that have shown the effectiveness of providing targeted outreach testing in numerous settings.65–69 Examples of nonclinical settings where HIV testing may be offered include but are not limited to community-based organizations, mobile testing units, churches, bathhouses, parks, shelters, syringe services programs, health-related storefronts, homes, and other social-service organizations. CDC has also developed and piloted interventions such as the social network strategy for recruiting peers who would benefit from HIV testing70,71 and has developed trainings for community-based organizations to implement this strategy.72 A specific, innovative use of a cohort of peer community health workers to conduct outreach and testing in community settings that was implemented as part of the EHE jump-start in East Baton Rouge Parrish, Louisiana14 is included in this issue. There are a wide variety of adaptations of these methods, and therefore, there is a need for more implementation science73 to identify the best new strategies to increase testing in outreach settings.

STRATEGY 3: INCREASE AT LEAST YEARLY RESCREENING OF PEOPLE AT ELEVATED RISK FOR HIV PER CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION TESTING GUIDELINES IN HEALTHCARE AND NONHEALTHCARE SETTINGS

Although CDC estimates that approximately 1.2 million people in the U.S. have indications for HIV PrEP,74 estimates from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System indicate that there may be >12 million people with past-year risk for HIV and that only 34.2% of this group were tested in the past 12 months.4,5 CDC recommends that people who participate in activities that increase the possibility of HIV acquisition test at least annually, but another CDC analysis3 indicated that even among sexually active MSM, only 42% reported testing in the past year, and therefore, the mean time since the last test even among this group was >1 year. This is consistent with a systematic review examining studies from 2005 through 2014 that found that 63%–91% of MSM had ever tested for HIV, but only 39%–67% were being tested annually.75 One strategy for increasing the frequency of testing is the provision of HIV self-tests. In the eSTAMP study,51 participants who were randomized to receive HIV self-tests by mail reported testing more frequently than control participants (mean number of tests over 12 months: 5.3 vs 1.5, p<0.001). Other observational studies have shown that public health programs perceive benefits of strategies to encourage frequent retesting, particularly among MSM.75 In Seattle, observational data from programs that promote retesting on a regular schedule and through short message service reminders have been shown to increase the frequency of testing.76,77 In a recent randomized trial in Thailand,78 the combination of both short message service text message reminders and scheduling of the next HIV test at the time of a negative result was shown to maximize the frequency of rescreening. Evaluation of other modalities, including phone applications that provide reminders to rescreen, the ability to communicate HIV testing information in online profiles, and other methods of reminding people to rescreen for HIV, have shown promise.79

The challenge for encouraging rescreening in healthcare settings is that most clinical decision support tools do not routinely collect information indicative of HIV risk, and many patients do not disclose this information to clinicians.80 Likewise, in settings such as emergency departments where prevention is not the primary focus of the medical encounter, identifying and testing people engaging in behaviors with potential for HIV acquisition may not be top of mind for either the clinician or the patient. The impact of clinical decision support tools, including a supplemental electronic collection of behavioral risk81 that can initiate HIV rescreening for individuals who have not been tested in the past year, is another area of active implementation science research that deserves more attention.73

MEASURING IMPACT OF TESTING PROGRAMS

As with other EHE pillars, the indicators used to measure national progress on the Diagnose pillar82,83 are derived from data reported to the National HIV Surveillance System and reported quarterly on America’s HIV Epidemic Analysis Dashboard.84 The most proximal of the 6 EHE indicators for the Diagnose pillar is knowledge of HIV status, which is estimated from the National HIV Surveillance System data as the percentage of people with HIV who have received a diagnosis. The 2025 and 2030 targets for this indicator are for 95% of people with HIV to know that they are infected. Similarly, the Healthy People 2030 HIV objectives and targets85 are aligned with indicators in the EHE initiative; Target 02 is to increase the proportion of people who know their HIV status to 95% by 2030. Baseline data for EHE as presented for 2017 and 2018 indicate that the knowledge of status varied between 71.1% in Nevada and 93.2% in the District of Columbia before the start of the EHE initiative. However, as with other EHE indicators, disparities exist by race and age, with a lower proportion of Black and Hispanic individuals being aware of their infection, particularly in the youngest age groups. As the EHE initiative gains momentum, new diagnoses will decrease,86 and other measures such as PrEP prescriptions and total tests performed may be more important measures of progress. CDC is working with national data vendors and state and local HDs to evaluate other process measures for the Diagnose pillar86 (e.g., the estimated time from infection to diagnosis87 and laboratory testing volumes88).

COVID-19 AND BEYOND

Plans for the first year of implementation of the EHE initiative were disrupted by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Many states and localities issued shelter-in-place or stay-at-home orders to reduce the spread of COVID-19, limiting movement outside the home to essential activities. Social distancing also led to disruptions of routine healthcare and nonclinical services such as community-based HIV testing. However, this public health crisis has catalyzed the rapid implementation of new strategies for HIV testing, particularly the distribution of HIV rapid self-tests and mail-in HIV home sample collection kits. In this issue, Fistonich and colleagues60 describe how they stood up the GetTestedDC program with great success in the middle of the pandemic. Other models,57 such as the combined offer of HIV and COVID-19 testing at drive-through test sites, and online counselor-led HIV self-testing have shown promise. Hammack et al.14 describe how they adapted their novel outreach model during the pandemic, including information about options for COVID-19 testing, in a way that makes the entire encounter with the community health workers less about HIV and more about health, a strategy that may reduce the stigma associated with HIV testing. Leveraging the lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic to improve access to and uptake of HIV testing is an opportunity. Models that have grown out of necessity during the pandemic should be further evaluated for their impact on efforts to end the HIV epidemic in the U.S. after the COVID-19 pandemic.

CONCLUSIONS

Ending the HIV epidemic in the U.S. by 2030 is an ambitious goal. The COVID-19 pandemic has slowed initial progress but has also taught valuable lessons about both disparities in access to health care and public health services. All other EHE activities start with an awareness of HIV status, which is the EHE indicator for which the U.S. is closest to its targets. There are proven and emerging approaches to both increasing HIV screening and increasing the frequency of HIV screening available. The EHE initiative provides the motivation, the resources, and a coordinated plan to bring them to scale.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

KPD contributed to the study conceptualization and visualization and to the writing (original draft preparation and review and editing) of this paper. EAD contributed to the study conceptualization and to the writing (original draft preparation and review and editing) of this paper.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENT NOTE

This article is part of a supplement entitled The Evidence Base for Initial Intervention Strategies for Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S., which is sponsored by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC or HHS.

REFERENCES

- 1.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR–14). 1–CE4 https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5514a1.htm. Accessed August 19, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiNenno EA, Prejean J, Irwin K, et al. Recommendations for HIV screening of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(31):830–832. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6631a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pitasi MA, Delaney KP, Oraka E, et al. Interval since last HIV test for men and women with recent risk for HIV infection - United States, 2006-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(24):677–681. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6724a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pitasi MA, Delaney KP, Brooks JT, DiNenno EA, Johnson SD, Prejean J. HIV testing in 50 local jurisdictions accounting for the majority of new HIV diagnoses and seven states with disproportionate occurrence of HIV in rural areas, 2016-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(25):561–567. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6825a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel D, Johnson CH, Krueger A, et al. Trends in HIV testing among U.S. adults, aged 18-64 years, 2011-2017. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(2):532–539. 10.1007/s10461-019-02689-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoover KW, Huang YA, Tanner ML, et al. HIV testing trends at visits to physician offices, community health centers, and emergency departments - United States, 2009-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(25):776–780. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6925a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark HA, Oraka E, DiNenno EA, et al. Men who have sex with men (MSM) who have not previously tested for HIV: results from the MSM testing initiative, United States (2012-2015). AIDS Behav. 2019;23(2):359–365. 10.1007/s10461-018-2266-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV Epidemic: a plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019;321(9):844–845. 10.1001/jama.2019.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ending the HIV Epidemic in the US: overview. HIV.gov. https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/ending-the-hiv-epidemic/overview. Updated June 2, 2021. Accessed August 21, 2021.

- 10.Williams W, Krueger A, Wang G, Patel D, Belcher L. The contribution of HIV testing funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to HIV diagnoses in the United States, 2010–2017. J Community Health. 2021;46(4):832–841. 10.1007/s10900-020-00960-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funding opportunity announcement PS20-2010: integrated HIV programs for Health Departments to Support Ending the HIV epidemic in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 20, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/funding/announcements/ps20-2010/index.html. Accessed January 29, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith D The evidence base for initial intervention strategies for Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(5S1):S1–S5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Myers JE, Braunstein SL, Xia Q, et al. Redefining prevention and care: a status-neutral approach to HIV. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(6):ofy097. 10.1093/ofid/ofy097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammack AY, Bickham JN, Gilliard I III, Robinson WT. A community health worker approach for ending the HIV epidemic. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(5S1):S26–S31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oster AM, Lyss SB, McClung RP, et al. HIV cluster and outbreak detection and response: the science and experience. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(5S1):S130–S142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alpren C, Dawson EL, John B, et al. Opioid use fueling HIV transmission in an urban setting: an outbreak of HIV infection among people who inject drugs-Massachusetts, 2015-2018. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(1):37–44. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim MM, Conyngham SC, Smith C, et al. Understanding the intersection of behavioral risk and social determinants of health and the impact on an outbreak of human immunodeficiency virus among persons who inject drugs in Philadelphia. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(suppl 5):S250–S258. 10.1093/infdis/jiaa128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duwve J, Stover D. Abstract 5735 – HIV outbreak related to injection of prescription opioids in Scott County, Indiana: an updated emphasizing the power of partnerships. 2019 National HIV Prevention Conference; Atlanta, Georgia; March 18–21, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nhpc/pdf/NHPC-2019-Abstract-Book.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pack A, Venegas Y, Ortega J, Taylor B, Woo C. Abstract 5581 - Community response to HIV clusters in San Antonio, Texas, 2017–2018. 2019 National HIV Prevention Conference; Atlanta, Georgia; March 18–21, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/nhpc/pdf/NHPC-2019-Abstract-Book.pdf. Accessed September 13, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golden MR, Lechtenberg R, Glick SN, et al. Outbreak of human immunodeficiency virus infection among heterosexual persons who are living homeless and inject drugs - Seattle, Washington, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(15):344–349. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6815a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Owens DK, Davidson KW, et al. Screening for HIV infection: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2019;321(23):2326–2336. 10.1001/jama.2019.6587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rizza SA, MacGowan RJ, Purcell DW, Branson BM, Temesgen Z. HIV screening in the health care setting: status, barriers, and potential solutions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(9):915–924. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White BL, Walsh J, Rayasam S, Pathman DE, Adimora AA, Golin CE. What makes me screen for HIV? Perceived barriers and facilitators to conducting recommended routine HIV testing among primary care physicians in the Southeastern United States. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14(2):127–135. 10.1177/2325957414524025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sison N, Yolken A, Poceta J, et al. Healthcare provider attitudes, practices, and recommendations for enhancing routine HIV testing and linkage to care in the Mississippi Delta region. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(9):511–517. 10.1089/apc.2013.0169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crumby NS, Arrezola E, Brown EH, Brazzeal A, Sanchez TH. Experiences implementing a routine HIV screening program in two federally qualified health centers in the Southern United States. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(suppl 1):21–29. 10.1177/00333549161310S104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Implementing clinical decision support systems. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/pubs/guides/best-practices/clinical-decision-support.htm. Updated July 22, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nunn A, Towey C, Chan PA, et al. Routine HIV screening in an urban community health center: results from a geographically focused implementation science program. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(suppl 1):30–40. 10.1177/00333549161310S105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roche L, Zepeda S, Harvey B, Reitan KA, Taylor RD. Routine HIV screening as a standard of care: implementing HIV screening in general medical settings, 2013-2015. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(2):52S–59S (suppl). 10.1177/0033354918801833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arya M, Marren RE, Marek HG, Pasalar S, Hemmige V, Giordano TP. Success of supplementing national HIV testing recommendations with a local initiative in a large health care system in the U.S. South. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;83(2):e6–e9. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ending the HIV epidemic in East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana: jumpstarting success. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated May 11, 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/endhiv/action/stories/east-baton-rouge-intro.html. Accessed February 11, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis S, Morrison M, Randall LM, Roosevelt K. The Partnerships for Care Project in Massachusetts: developing partnerships and data systems to increase linkage and engagement in care for individuals living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;82(suppl 1):S47–S52. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanchez TH, Sullivan PS, Rothman RE, et al. A novel approach to realizing routine HIV screening and enhancing linkage to care in the United States: protocol of the FOCUS program and early results. JMIR Res Protoc. 2014;3(3):e39. 10.2196/resprot.3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macgowan R, Margolis A, Richardson-Moore A, et al. Voluntary rapid human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing in jails. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(suppl 2):S9–S13. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318148b6b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates of and releasees from U.S. correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PLoS One. 2009;4(11):e7558. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Routine jail-based HIV testing - Rhode Island, 2000-2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(24):742–745. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5924a3.htm. Accessed August 19, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HIV screening of male inmates during prison intake medical evaluation–Washington, 2006-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(24):811–813. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6024a3.htm. Accessed August 19, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Routine HIV screening during intake medical evaluation at a County Jail - Fulton County, Georgia, 2011-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(24):495–497. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6224a3.htm. Accessed August 19, 2021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lederman E, Blackwell A, Tomkus G, et al. Opt-out testing pilot for sexually transmitted infections among immigrant detainees at 2 immigration and customs enforcement Health Service Corps-staffed detention facilities, 2018. Public Health Rep. 2020;135(suppl 1):82S–89S. 10.1177/0033354920928491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shrestha RK, Sansom SL, Richardson-Moore A, et al. Costs of voluntary rapid HIV testing and counseling in jails in 4 states–advancing HIV Prevention Demonstration Project, 2003-2006. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(suppl 2):S5–S8. 10.1097/olq.0b013e318148b69f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shrestha RK, Chavez PR, Noble M, et al. Estimating the costs and cost-effectiveness of HIV self-testing among men who have sex with men, United States. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(1):e25445. 10.1002/jia2.25445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shrestha RK, Sansom SL, Kimbrough L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of using social networks to identify undiagnosed HIV infection among minority populations. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010;16(5):457–464. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181cb433b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shrestha RK, Clark HA, Sansom SL, et al. Cost-effectiveness of finding new HIV diagnoses using rapid HIV testing in community-based organizations. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(suppl 3):94–100. 10.1177/00333549081230S312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spaulding AC, MacGowan RJ, Copeland B, et al. Costs of rapid HIV screening in an urban emergency department and a nearby county jail in the Southeastern United States. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128408. 10.1371/journal.pone.0128408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Testing Implementation Guidance for Correctional Settings. www.cdc.gov/correctionalhealth/rec-guide.html. Published January 2009. Accessed February 12, 2021.

- 45.Hutchinson AB, MacGowan RJ, Margolis AD, Adee MG, Wen W, Bowden CJ, Spaulding AC. Costs and consequences of eliminating a routine, point-of-care HIV screening program in a high prevalence jail. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(5S1):S32–S38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015;64(No. RR-3). https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/rr/rr6043.pdf. Accessed August 18, 2021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seth P, Wang G, Collins NT, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Identifying new positives and linkage to HIV medical care—23 testing site types, United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(24):663–667. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6424a3.htm. Accessed August 19, 2021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seth P, Wang G, Sizemore E, Hogben M. HIV testing and HIV service delivery to populations at high risk attending sexually transmitted disease clinics in the United States, 2011-2013. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(11):2374–2381. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patel SN, Delaney KP, Pitasi MA, et al. Self-reported prevalence of HIV testing among those reporting having been diagnosed with selected STIs or HCV, United States, 2005-2016. Sex Transm Dis. 2020;47(5S suppl 1):S53–S60. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STD prevention success stories – turning the page on HIV: new CDC initiative fuels progress in STD clinics. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/std/products/success/SuccessStory-EHE-2020-cleared.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 51.MacGowan RJ, Chavez PR, Borkowf CB, et al. Effect of internet-distributed HIV self-tests on HIV diagnosis and behavioral outcomes in men who have sex with men: a randomized clinical trial [published correction appears in JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(8):1134]. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(1):117–125. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.5222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Edelstein ZR, Wahnich A, Purpura LJ, et al. Five waves of an online HIV self-test giveaway in New York City, 2015 to 2018. Sex Transm Dis. 2020;47(5S):S41–S47 suppl 1). 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosengren AL, Huang E, Daniels J, Young SD, Marlin RW, Klausner JD. Feasibility of using Grindr™ to distribute HIV self-test kits to men who have sex with men in Los Angeles, California. Sex Health. 2016;13(4):389–392. 10.1071/SH15236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.National Association of State and Territorial AIDS Directors. Utilizing HIV self-testing to End the HIV Epidemic. Washington, DC: National Association of State and Territorial AIDS Directors. https://www.nastad.org/webinars/utilizing-hiv-self-testing-end-hiv-epidemic. Published March 9, 2020. Accessed August 21, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Katz DA, Golden MR, Hughes JP, Farquhar C, Stekler JD. HIV self-testing increases HIV testing frequency in high-risk men who have sex with men: a randomized controlled trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;78(5):505–512. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Edelstein Z, Wahnich A. Introduction to the online home HIV test giveaway. New York, NY: New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. https://zoom.us/recording/play/JVlh0q-DR5hK7MLeWwCv_Kvw2jdDQvSAoFYgIxUk8kVM-rOHwMVvM8JIxZDBdED66?startTime=1553799193000. Published March 28, 2019. Accessed August 21, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clinical Protocols. Denver Prevention Training Center. https://www.denverptc.org/resource_search.html?pub_type_id=4. Accessed August 20, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Compendium of Evidence-Based Interventions and Best Practices for HIV Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/interventionresearch/compendium/index.html. Updated June 28, 2021. Accessed August 18, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Testing beyond the clinic webinar series. National coalition of STD Directors. https://www.ncsddc.org/resource/at-home-testing-webinar-series/. Updated August 6, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fistonich GM, Troutman KM, AJ Visconti AJ. A pilot of mail-out HIV and sexually transmitted infection testing in Washington, District of Columbia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Prev Med. 2021;61(5S1):S16–S25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Collins B, Bronson H, Elamin F, Yerkes L, Martin E. The “No Wrong Door” approach to HIV testing: results from a statewide retail pharmacy-based HIV testing program in Virginia, 2014-2016. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(suppl 2):34S–42S. 10.1177/0033354918801026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weidle PJ, Lecher S, Botts LW, et al. HIV testing in community pharmacies and retail clinics: a model to expand access to screening for HIV infection. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2014;54(5):486–492 (2003). 10.1331/JAPhA.2014.14045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lecher SL, Shrestha RK, Botts LW, et al. Cost analysis of a novel HIV testing strategy in community pharmacies and retail clinics. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2015;55(5):488–492 (2003). 10.1331/JAPhA.2015.150630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.HIV testing in retail pharmacies. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/effective-interventions/diagnose/hiv-testing-in-retail-pharmacies?sort=title%3a%3aasc&intervention%20name=hiv%20testing%20in%20retail%20pharmacies. Updated August 2, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heffelfinger JD, Sullivan PS, Branson BM, et al. Advancing HIV prevention demonstration projects: new strategies for a changing epidemic. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(suppl 3):5–15. 10.1177/00333549081230S302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bowles KE, Clark HA, Tai E, et al. Implementing rapid HIV testing in outreach and community settings: results from an advancing HIV prevention demonstration project conducted in seven U.S. cities. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(suppl 3):78–85. 10.1177/00333549081230S310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Begley EB, Oster AM, Song B, et al. Incorporating rapid HIV testing into partner counseling and referral services [published correction appears in Public Health Rep. 2009;124(5):624]. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(suppl 3):126–135. 10.1177/00333549081230s315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schulden JD, Song B, Barros A, et al. Rapid HIV testing in transgender communities by community-based organizations in three cities. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(suppl 3):101–114. 10.1177/00333549081230S313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Clark HA, Bowles KE, Song B, Heffelfinger JD. Implementation of rapid HIV testing programs in community and outreach settings: perspectives from staff at eight community-based organizations in seven U.S. cities. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(suppl 3):86–93. 10.1177/00333549081230S311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of social networks to identify persons with undiagnosed HIV infection–seven U.S. cities, October 2003-September 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(24):601–605. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5424a3.htm. Accessed August 19, 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McGoy SL, Pettit AC, Morrison M, et al. Use of social network strategy among young black men who have sex with men for HIV testing, linkage to care, and reengagement in care, Tennessee, 2013-2016. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(2):43S–51S (suppl). 10.1177/0033354918801893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Social network strategy for HIV testing recruitment. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/effective-interventions/diagnose/social-network-strategy/index.html?sort=title%3a%3aasc&intervention%20name=social%20network%20strategy. Updated August 2, 2021. Accessed August 20, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 73.CFAR/ARC Ending the HIV Epidemic supplement awards. NIH, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/research/cfar-arc-ending-hiv-epidemic-supplement-awards#:~:text=ending%20the%20hiv%20epidemic%202020%20supplements:%20two-year%20awards,prep%20implement%20…%20%208%20more%20rows. Updated September 28, 2020. Accessed August 21, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Harris NS, Johnson AS, Huang YA, et al. Vital signs: status of human immunodeficiency virus testing, viral suppression, and HIV preexposure prophylaxis - United States, 2013-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(48):1117–1123. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6848e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.DiNenno EA, Prejean J, Delaney KP, et al. Evaluating the evidence for more frequent than annual HIV screening of gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in the United States: results from a systematic review and CDC expert consultation. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(1):3–21. 10.1177/0033354917738769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Katz DA, Swanson F, Stekler JD. Why do men who have sex with men test for HIV infection? Results from a community-based testing program in Seattle. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(9):724–728. 10.1097/01.olq.0000431068.61471.af. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Katz DA, Dombrowski JC, Swanson F, Buskin SE, Golden MR, Stekler JD. HIV intertest interval among MSM in King County, Washington. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(1):32–37. 10.1136/sex-trans-2011-050470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Salvadori N, Adam P, Mary JY, et al. Appointment reminders to increase uptake of HIV retesting by at-risk individuals: a randomized controlled study in Thailand. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(4):e25478. 10.1002/jia2.25478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Veronese V, Ryan KE, Hughes C, Lim MS, Pedrana A, Stoové M. Using digital communication technology to increase HIV testing among men who have sex with men and transgender women: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(7):e14230. 10.2196/14230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Qiao S, Zhou G, Li X. Disclosure of same-sex behaviors to health-care providers and uptake of HIV testing for men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Am J Mens Health. 2018;12(5):1197–1214. 10.1177/1557988318784149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.John SA, Petroll AE, Walsh JL, Quinn KG, Patel VV, Grov C. Reducing the discussion divide by digital questionnaires in health care settings: disruptive innovation for HIV testing and PrEP screening. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;85(3):302–308. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC HIV prevention progress report, 2019. Atlanta, GA: Center’s for Disease Control and Prevention; Published March 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies/progressreports/cdc-hiv-preventionprogressreport.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas. 2018. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-25-2.pdf. Published May 2020. Accessed January 6, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 84.The six EHE indicators. America’s HIV Epidemic Analysis Dashboard (AHEAD), HHS. https://ahead.hiv.gov/indicators/knowledge-of-status/. Accessed August 21, 2021.

- 85.HIV workgroup. Healthy People 2030, HHS, Office of Disease Prevention and Health promotion. https://health.gov/healthypeople/about/workgroups/hiv-workgroup#about. Accessed August 21, 2021.

- 86.Delaney KP, Jenness S, Johnson JA, et al. How should we prioritize and monitor interventions to End the HIV Epidemic in America? Paper presentend at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; March 8–11, 2020. https://www.croiconference.org/abstract/how-should-we-prioritize-and-monitor-interventions-to-end-hiv-epidemic-in-america/. Accessed August 21, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hall HI, Song R, Szwarcwald CL, Green T. Brief report: time from infection with the human immunodeficiency virus to diagnosis, United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(2):248–251. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Delaney KP, Jayanthi P, Emerson B, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on commercial laboratory testing for HIV in the United States. Top Antivir Med. 2021;29(1):288. http://iasusa.org/tam/March-2021/. Accessed August 21, 2021. [Google Scholar]