Key Points

Question

Does increased familiarity on resident-nurse medical teams improve team performance, psychological safety, or communication?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 33 medical residents and 91 nurses in an inpatient general medical service at a large academic medical center, increased familiarity was found to improve team performance on standardized medical simulations, increase the likelihood that a nurse was present and contributing to inpatient rounds, and enhance nursing perception of teamwork culture earlier in the academic year.

Meaning

Given the increased reliance on interprofessional teams in health care delivery, understanding metrics that drive team performance is important; therefore, medical centers should consider team familiarity as a potential metric to improve physician-nursing teamwork and patient care.

Abstract

Importance

In large academic centers, medical residents work on multiple clinical floors with transient interactions with nursing colleagues. Although teamwork is critical in delivering high-quality medical care, little research has evaluated the effect of interprofessional familiarity on inpatient team performance.

Objective

To determine the effectiveness of increased familiarity between medical residents and nurses on team performance, psychological safety, and communication.

Design, Setting, and Participants

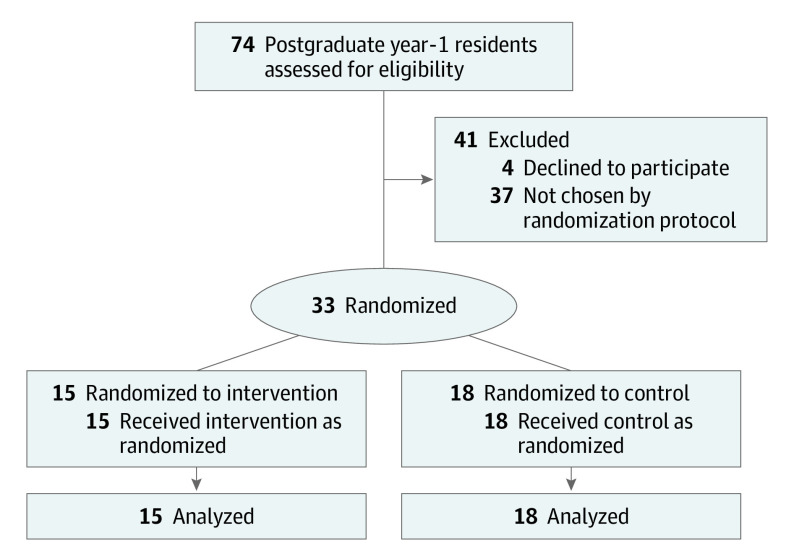

A 12-month randomized clinical trial in an inpatient general medical service at a large academic medical center was completed from June 25, 2019, to June 24, 2020. Participants included 33 postgraduate year (PGY)–1 residents in an internal medicine residency program and 91 general medicine nurses.

Interventions

Fifteen PGY-1 residents were randomized to complete all 16 weeks of their general medicine inpatient time on 1 medical nursing floor (intervention group with 43 nurses). Eighteen PGY-1 residents completed 16 weeks on 4 different general medical floors as per usual care (control group with 48 nurses).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was an assessment of team performance in physician-nurse simulation scenarios completed at 6 and 12 months. Interprofessional communication was assessed via a time-motion study of both work rounds and individual resident clinical work. Psychological safety and teamwork culture were assessed via surveys of both residents and nurses at multiple time points.

Results

Of the intervention and control PGY-1 residents, 8 of 15 (54%) and 8 of 18 (44%) were women, respectively. Of the nurses in the intervention and control groups with information available, 37 of 40 (93%) and 34 of 38 (90%) were women, respectively, and more than 70% had less than 10 years of clinical experience. There was no difference in overall team performance during the first simulation. At the 12-month simulation, the intervention teams received a higher mean overall score in leadership and management (mean [SD], 2.47 [0.53] vs 2.17 [0.39]; P = .045, Cohen d = 0.65) and on individually rated items were more likely to work as 1 unit (100% vs 62%; P = .003), negotiate with the patient (61% vs 10%; P = .001), support other team members (61% vs 24%; P = .02), and communicate as a team (56% vs 19%; P = .02). The intervention teams were more successful in achieving the correct simulation case outcome of negotiating a specific insulin dose with the patient (67% vs 14%; P = .001). Time-motion analysis noted intervention teams were more likely to have a nurse present on work rounds (47% vs 28%; P = .03). At 6 months, nurses in the intervention group were more likely to report their relationship with PGY-1 residents to be excellent to outstanding (74% vs 40%; P = .003), feel that the input of all clinical practitioners was valued (95% vs 53%; P < .001), and say that feedback between practitioners was delivered in a way to promote positive interactions (90% vs 60%; P = .003). These differences diminished at the 12-month survey.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this randomized clinical trial, increased familiarity between nurses and residents promoted more rapid improvement of nursing perception of team relationships and, over time, led to higher team performance on complex cognitive tasks in medical simulations. Medical centers should consider team familiarity as a potential metric to improve physician-nursing teamwork and patient care.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05213117

This randomized clinical trial determines the effect of increased interprofessional familiarity between medical residents and nurses on inpatient medical team performance, communication, and psychological safety.

Introduction

Teamwork is critical in delivering quality medical care. Failures in team communication and coordination have been cited as substantial contributors to medical errors.1,2,3,4 In large teaching hospitals, patients receive care from transiently formed interprofessional teams as residents rotate through clinical floors, each with its own nursing staff. These time-limited resident-nurse care groups work via teaming, a process where a group of diverse practitioners transiently come together to complete a complex task, such as the care of patients.5

A risk in frequent changes of clinical staff is the lack of familiarity among team members, as studies suggest familiarity promotes an environment of psychological safety, where members feel safe speaking up, asking for help, and admitting errors.6,7 Speaking up is critical for patient safety, as failure to identify or synthesize relevant clinical information often comes from fear of disclosing poor understanding.8 Open discussion of problems among team members may account for why familiar teams acquire new knowledge more quickly when working on complex tasks requiring the sharing of expertise.9

Geographic localization of hospitalists and residents to promote interdisciplinary rounds allows more efficient physician-nurse communication and familiarity.4,7,10,11,12 Similarly, localization can increase the percentage of time nurses join rounds, yet it is unclear if increased time together enhances the quality of communication and teamwork.4,10

To better understand the effect of familiarity on resident-nurse inpatient medical teams, we implemented a randomized clinical trial of increased team familiarity. We hypothesized that increasing the frequency with which groups of residents and nurses worked together would enhance performance, communication, psychological safety, and patient-related outcomes.

Methods

Setting

This randomized clinical trial was conducted on the medicine teaching service at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), an 1100-bed quaternary medical facility in Boston (Supplement 1). The resident medical service is located on 6 different inpatient medical floors. This study was approved by the MGH Institutional Review Board. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline was followed.

The internal medicine residency program at MGH has more than 200 residents. Medical resident teams consist of 1 postgraduate year (PGY)–2 resident, 4 PGY-1 residents, and 2 teaching attendings caring for 16 patients geographically located on 1 medical floor. Patients are cared for by the entire medical team, and PGY-1 residents divide patient-related tasks based on rotating roles and thus do not have an individualized patient list. This team-based model is standard of care and was the same for both control and intervention teams. The PGY-1 residents are scheduled for 4 general medicine team rotations split into four 4-week blocks during the academic year. Although a team is geographically located on 1 floor, residents’ 4 team rotations are randomly assigned to any of the 6 medical floors. The majority of PGY-1 residents work on 4 different floors during the year.

The study was completed over 12 months, from June 25, 2019, to June 24, 2020. Fifteen randomly selected PGY-1 residents were assigned to the intervention group to spend all 16 weeks of their medical rotations on the same inpatient medical floor. A second inpatient floor was designated as the control where 18 randomly selected PGY-1 residents spent their first rotation. Their remaining 3 rotations were randomly assigned across 5 medical floors. Medical attendings work 2-week blocks and were not preferentially assigned to the same floor. The PGY-2 residents in the intervention group were assigned to the same floor; however, PGY-2 residents work only 4 weeks on the service and, because of their limited presence, were not included in the results. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the study was paused from March 10 to May 13, 2020, and resumed when staffing models reinstated usual team structure. As a result, intervention PGY-1s spent a total of 12 weeks on the same inpatient medical floor instead of the intended 16 weeks in the original study design.

Participants

A total of 74 incoming PGY-1 residents for the 2019 to 2020 academic year were invited to participate. Of the 70 who agreed, 15 were randomly chosen for the intervention group and the first 18 scheduled to the control floor were deemed control (Figure). There were 91 general medical nurses in the study, 43 on the intervention floor and 48 on the control floor. Each floor was managed by a nurse and physician director as per usual protocol. Physician-nurse patient rounds and multidisciplinary rounds were the same on both floors. There were no new interdisciplinary initiatives started during the trial. General medical patients were randomly assigned to floors based on bed availability by admitting services. There were no exclusion criteria for residents or nursing staff, and all participants provided informed consent in accordance with the institutional review board protocol and could decline participation at any time. Residents were invited to participate in the study via email and were offered the opportunity to opt out from the overall study. For both residents and nurses, survey consent was implied via survey completion, and written and oral consent was obtained for all simulation participants.

Figure. CONSORT Flow Diagram.

Flow diagram of participant enrollment and randomization.

Outcomes

We explored team performance, interprofessional communication, psychological safety, and patient-related outcomes.9

1. Team performance was evaluated via blinded rated observations of study teams in medical simulations created to mimic realistic encounters on the medical wards. Two medical scenarios were created by the research team. The first, a case of anaphylaxis, tested the team’s ability to diagnose a medical emergency and respond to a protocol-driven algorithm. The second simulation involved negotiation around a dose of insulin with an angry patient. Here, the actor, blinded to the study group assignment, was instructed to test team cohesiveness by confronting 1 team member and to only de-escalate their demands if the team was responsive to their concerns. This simulation was a more difficult stress of team dynamics given the ambiguity in the correct approach and the feedback loop provided by the actor’s performance. The team’s response to the actor’s prompts was integrated into the evaluation of their performance (eMethods 1-3 in Supplement 2).

Each simulation was 20 minutes long, and each team was composed of 2 PGY-1s and 2 nurses paired based on the study group. Simulations were run for 7 intervention and 7 control teams involving a total of 28 interns and 28 nurses at the 6-month and 12-month simulations. Detailed prebrief and debriefing sessions were held during the simulation sessions consistent with established norms.13 The first simulation was performed in January 2020 using a Laerdal SimMan 3G high-fidelity simulator. The second in June/July 2020 used a standardized actor.

All simulations were video recorded, and team performance was rated by 3 clinicians not involved in the study and blinded to study group using a modified Oxford Non-Technical Skills (NOTECHS) scale.14,15,16 The NOTECHS scale was designed to assess interdisciplinary teamwork on nontechnical skills in the operating room; this was adapted to assess intern-nurse teamwork during simulated patient encounters in inpatient medical settings. Reviewers rated team performance on individual items, each on a 4-point scale, that were linked to the domains of communication and interaction, cooperation and team skills, decision-making, and leadership and management.14 Interrater reliability for the 2 simulations was moderate (κ = 0.47; 95% CI, 0.46-0.48).17 Top box responses for prespecified individually rated items in NOTECHS that were applicable to medical patient encounters were included in the statistical analysis.

Because of technical difficulties, analysis was completed on only 5 intervention and control teams for the first simulations and 6 intervention and 7 control for the second simulation.

2. Interprofessional communication was assessed via time-motion observation of teams by a trained independent observer. Participants were followed on patient work rounds and while completing medical tasks to determine nursing participation and communication between nurses and PGY-1 residents. The duration of rounds, number of patients seen by team, and mode of communication were recorded using an iPad (Apple) running Microsoft Access timing program.10

3. Psychological safety and teamwork culture were assessed via survey of resident and nurses. The PGY-1 residents were surveyed 3 times during the study, at the end of each 4-week block on the inpatient service. Nurses were surveyed at 6 months and 12 months. Surveys were modified from prior published surveys on psychological safety and teamwork5,18 (eMethods 4 and 5 in Supplement 2).

4. Patient-related metrics were established via interrogation of the medical record. Patient length of stay and the number of intensive care unit transfers on study teams were determined.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine trends in team performance, interprofessional communication, psychological safety, teamwork culture, patient-related metrics, and time-motion observation. We used bivariate analysis using t tests and χ2 tests to examine group differences for means and proportions, as appropriate. In particular, team performance by group (control vs intervention), the proportions of the rated observations for the individually scored items, were analyzed using χ2 tests, and the NOTECHS categories were analyzed using 2-sample t tests, examining mean differences, following the development of the specific construct score. For interprofessional communication by group (control vs intervention), time-motion observation data were analyzed descriptively via totals, as well as via bivariate comparisons using both χ2 tests related to comparing proportions of specific occurrences on the floor (such as the number of nurse–PGY-1 interactions) and 2-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) tests, testing for differences on specific time variables (such as time in seconds that members of the team spoke on work rounds). Psychological safety and teamwork culture by group (control vs intervention) were analyzed using χ2 tests to compare the proportions of responses to specific questions on the surveys. Finally, for patient-related metrics by floor, data were obtained via an internal data warehouse and were analyzed descriptively via total count of patients, as well as via bivariate comparisons using a 2-sample t test for age, 2-sample Wilcoxon (Mann-Whitney) rank-sum test for length of stay, and χ2 for categorical variables (such as sex, race and ethnicity, etc). Race and ethnicity data were collected as a standardized metric in quality reports for the hospital and were reported to demonstrate the patient populations on both floors were similar. Study data were collected using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). The 2-sided level of significance assessed was P < .05. Data compilation and analyses were conducted using statistical software Stata 17 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

Study Participants and Patients

Fifteen PGY-1 residents were randomized to complete all 16 weeks of their general medicine inpatient time on 1 medical nursing floor (intervention group). Eighteen PGY-1 residents completed 16 weeks on 4 different general medical floors as per usual care (control group). Forty-three nurses on the intervention floor and 48 nurses on the control floor participated.

Of the intervention and control PGY-1 residents, 8 of 15 (54%) and 8 of 18 (44%) were women, respectively. The majority of the nursing staff was women with more than 70% having less than 10 years of clinical experience (Table 1). During the study, there were 957 and 917 patients admitted to the control and intervention floors, respectively. There was no difference in patient characteristics, including comorbidity index, between the study groups except for sex (Table 2).

Table 1. Participant Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | |

| PGY-1 residents, No. | 18 | 15 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 8 (44) | 8 (53) |

| Male | 10 (56) | 7 (47) |

| Nurses, No. | ||

| On floor | 48 | 43 |

| With available information | 40 | 38 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 37 (93) | 34 (90) |

| Male | 3 (7) | 4 (10) |

| Experience, y | ||

| <3 | 9 (23) | 17 (45) |

| 3-10 | 22 (55) | 10 (26) |

| >10 | 9 (23) | 11 (29) |

Abbreviation: PGY, postgraduate year.

Table 2. Patient Characteristics.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | ||

| No. | 957 | 917 | NA |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 65.4 (18.1) | 66.1 (19.1) | .46 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 420 (43.9) | 497 (54.2) | <.001 |

| Male | 537 (56.1) | 420 (45.8) | |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 29 (3.0) | 35 (3.8) | .49 |

| Black non-Hispanic | 63 (6.6) | 58 (6.3) | |

| Hispanic | 84 (8.8) | 74 (8.1) | |

| Multiracial | 16 (1.7) | 7 (0.8) | |

| White non-Hispanic | 722 (75.4) | 701 (76.4) | |

| Unknown | 43 (4.6) | 42 (4.6) | |

| Insurance | |||

| Medicare | 474 (49.5) | 482 (52.6) | .32 |

| Medicaid | 187 (19.5) | 150 (16.4) | |

| Private | 286 (29.9) | 276 (30.1) | |

| Null | 10 (1.0) | 9 (1.0) | |

| Comorbidity index | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.59 (1.60) | 1.65 (1.66) | .43 |

| Median (SD) | 1.10 (1.60) | 1.16 (1.66) | |

| Length of stay, median (IQR), d | 5.0 (3.0-8.0) | 5.0 (3.0-8.0) | .56 |

| Deathsa | 16 (1.7) | 22 (2.4) | .26 |

| Transfer to ICUb | 24 (2.5) | 32 (3.5) | .21 |

| Discharge dispositionc | |||

| Home | 413 (43.9) | 370 (41.3) | .67 |

| Home with services | 280 (29.8) | 271 (30.3) | |

| Facility | 223 (23.7) | 226 (25.3) | |

| Against medical advice | 25 (2.7) | 28 (3.1) | |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; NA, not applicable.

Test included both death and other, but other is not shown in the table.

Test included both ICU and no ICU transfers, but no ICU transfers is not shown in the table.

Excludes death.

Team Performance

In the first simulation, anaphylaxis, there was no difference between intervention and control teams on composite NOTECHS assessment scores (Table 3). For individually rated metrics, the intervention teams were more likely to ask the patient appropriate questions (60% vs 20%; P = .03) and anticipate problems (73% vs 27%; P = .01). There was no statistical difference between intervention and control teams in correctly diagnosing anaphylaxis (53% vs 67%; P = .46).

Table 3. Simulation Results.

| NOTECHS category | No. of items rated in construct | Mean (SD)a | Effect size, SMD | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 5) | Intervention (n = 5) | ||||

| Ratings and individual scoring items for simulation 1 at 6 mo (anaphylaxis) | |||||

| Communication and interaction | 6 | 3.14 (0.36) | 3.19 (0.44) | 0.13 | .77 |

| Cooperation and team skills | 7 | 3.32 (0.45) | 3.04 (0.38) | −0.67 | .07 |

| Decision-making | 3 | 3.13 (0.55) | 3.22 (0.70) | 0.14 | .70 |

| Leadership and management | 5 | 3.03 (0.29) | 3.04 (0.40) | 0.03 | .92 |

| Individually scored items | Top box, No. (%) | Difference, % | P value | ||

| Total No. of reviewer scores (3 reviewers for each simulation) | 15 | 15 | NA | NA | |

| Asks patient appropriate questionsb | 3 (20.0) | 9 (60.0) | 40 | .03 | |

| Anticipates potential problems and prepares contingency when considering anaphylaxis or allergic responsec | 4 (26.7) | 11 (73.3) | 47 | .01 | |

| Correct diagnosis of anaphylaxis | 10 (66.7) | 8 (53.3) | −13 | .46 | |

| Ratings and individual scoring items for simulation 2 at 1 y (insulin dose negotiation) | Control (n = 7) | Intervention (n = 6) | Effect size | P value | |

| Communication and interaction | 10 | 3.15 (0.55) | 3.26 (0.45) | 0.22 | .49 |

| Cooperation and team skills | 5 | 2.78 (0.62) | 3.08 (0.65) | 0.47 | .16 |

| Decision-making | 3 | 2.37 (0.65) | 2.61 (0.90) | 0.31 | .33 |

| Leadership and management | 4 | 2.17 (0.39) | 2.47 (0.53) | 0.65 | .045 |

| Individually scored items | Top box, No. (%) | Difference, % | P value | ||

| Total No. of reviewer scores (3 reviewers for each simulation) | 21 | 18 | NA | NA | |

| Team worked as 1 unitd | 13 (61.9) | 18 (100) | 38.1 | .003 | |

| Acknowledges contribution from other team memberse | 6 (28.6) | 10 (55.6) | 27.0 | .09 | |

| Negotiates with patient about insulinf | 2 (9.52) | 11 (61.1) | 51.6 | .001 | |

| Supports other team membersg | 5 (23.8) | 11 (61.1) | 37.3 | .02 | |

| Team communication (workload management)h | 4 (19.1) | 10 (55.6) | 36.5 | .02 | |

| 22 Units of insulin negotiated (correct answer)i | 3 (14.3) | 12 (66.7) | 52.4 | .001 | |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; NOTECHS, Non-Technical Skills scale; RN, registered nurse; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Scoring system of 1-4.

Score 1-4: 1 = does not ask patient any history questions; 2 = asks a few questions but not about allergies; 3 = asks a few history questions, including allergies; 4 = asks about allergies, prior blood pressure, and other history questions.

Score 1-4: 1 = no contingency plan; 2 = asks for rapid response team; 3 = asks for medications (anaphylaxis kit); 4 = asks for backup and medications (anaphylaxis kit).

Score 1-4: Number of team members who go into the room: 1, 2, 3, or 4.

Score 1-4: 1 = team members do not acknowledge that patient care requires teamwork; 2 = team members acknowledge RN’s role in giving insulin; 3 = team members acknowledge physician’s role in writing for insulin that RN gave; 4 = team members inform patient that physicians and RNs work together closely and that RN was not acting alone.

Score 1-4: 1 = does not negotiate with patient about dose; 2 = minimally negotiates with patient about dose; 3 = some negotiation with patient about dose; 4 = fully negotiates and convinces patient to take full amount of insulin.

Score 1-4: 1 = ignores patient’s accusation against RN; 2 = acknowledges accusation but does nothing; 3 = acknowledges accusation and attempts to address; 4 = acknowledges patient accusation of RN and supports team member.

Score 1-4: Number of team members who communicate with the patient: 1, 2, 3, or 4.

Question compared correct diagnoses (22 units) with any other amount or no agreement.

In the second simulation, insulin negotiation, the intervention team was rated higher in the NOTECHS composite teamwork score for leadership and management (mean [SD], 2.47 [0.53] vs 2.17 [0.39]; P = .045; Cohen d = 0.65) (Table 3). For individually rated metrics, intervention teams were more likely to work as 1 unit (100% vs 62%; P = .003), negotiate with the patient regarding their insulin dosage (61% vs 10%; P = .001), and communicate as a team (56% vs 19%; P = .02). Intervention teams were also more likely to convince the patient to take the correct dose of insulin as outlined in the case (67% vs 14%; P = .001).

Interprofessional Communication

Intervention and control team patient work-rounds were observed for 5 days for a mean of 156 minutes per day and 152 minutes per day, respectively (eTable in Supplement 2). Intervention teams were more likely to have nurses present when rounding on patients (47% vs 28%; P = .03). Approximately 8 different intervention and 8 control PGY-1s were observed while completing patient tasks and interacting with nurses over 16 days for a total of 2496 minutes and 2770 minutes, respectively. During this time, interns in the intervention group were paged 68 times and control interns 96 times. There was no statistically significant difference between the 2 groups in the number of times a nurse initiated an interaction or when personal names were used, although the percentage was consistently higher in the intervention group. Intervention PGY-1s and nurses were significantly more likely to have a personal conversation (14% vs 4%; P = .03).

Psychological Safety and Teamwork

The PGY-1 residents were surveyed 3 times, but only results from surveys 1 and 3 are reported because survey 2 and 3 results were similar. The mean survey response rate for all surveys was 88.1% (Table 419).

Table 4. Intern and Nursing Survey Responsesa.

| Top 2 boxes responseb | No. (%) | Difference, % | P value | No. (%) | Difference, % | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | |||||

| Intern surveys | Intern survey No. 1 c | Intern survey No. 3 d | ||||||

| No. | 17 | 15 | NA | NA | 18 | 12 | NA | NA |

| Psychological safety | ||||||||

| I felt safe to admit I did not know something | 16 (94) | 11 (73) | −21 | .11 | 16 (89) | 10 (83) | −6 | .66 |

| I felt safe to ask questions | 16 (94) | 13 (93) | −1 | .89 | 18 (100) | 11 (92) | −8 | .21 |

| I felt safe to voice my opinion | 15 (94) | 13 (87) | −7 | .51 | 16 (89) | 12 (100) | 11 | .23 |

| I was afraid of being judged | 1 (6) | 7 (47) | 41 | .008 | 1 (6) | 1 (8) | 2 | .77 |

| Teamwork | ||||||||

| How would you describe your relationship with the nurses on the floor?e | 11 (65) | 9 (60) | −5 | .78 | 14 (78) | 11 (92) | 14 | .32 |

| I consistently knew the names of all the nurses on the unitf | 3 (18) | 8 (53) | 35 | .03 | 5 (28) | 10 (83) | 55 | .003 |

| When hurdles were encountered, all practitioners were able to work through them together | 17 (100) | 12 (80) | −20 | .05 | 17 (94) | 11 (92) | −2 | .77 |

| The input of all clinical practitioners was valued when making decisions about patient care | 16 (94) | 12 (80) | −14 | .23 | 16 (89) | 10 (83) | −6 | .66 |

| Clinical practitioners on unit were free to raise concerns about patient plans or decisions | 16 (94) | 13 (87) | −7 | .47 | 18 (100) | 12 (100) | 0 | NA |

| It was easy to discuss difficult issues and problems with clinical practitioners on the floor | 15 (88) | 10 (67) | −21 | .14 | 17 (94) | 10 (83) | −11 | .32 |

| Feedback between individual clinical practitioners was delivered in a way that promotes positive interactions | 12 (71) | 9 (60) | −11 | .53 | 14 (78) | 10 (83) | 5 | .71 |

| Burnout scoreg | 7 (41) | 6 (43) | 2 | .95 | 12 (71) | 7 (58) | −13 | .49 |

| Nurse (RN) surveys | RN survey No. 1 (6 mo) | RN survey No. 2 (1 y) | ||||||

| No. | 40 | 38 | NA | NA | 34 | 37 | NA | NA |

| Psychological safety | ||||||||

| I felt safe to admit I did not know something | 36 (90) | 37 (97) | 7 | .18 | 34 (100) | 34 (92) | −8 | .09 |

| I felt safe to ask questions | 37 (93) | 38 (100) | 7 | .09 | 32 (94) | 37 (100) | 6 | .14 |

| I felt safe to voice my opinion | 36 (90) | 36 (95) | 5 | .43 | 31 (91) | 36 (97) | 6 | .26 |

| I was afraid of being judged | 5 (13) | 0 | −13 | .02 | 2 (6) | 2 (5) | −1 | .93 |

| Teamwork | ||||||||

| How would you describe your relationship with the interns on the floor?e | 16 (40) | 28 (74) | 34 | .003 | 21 (62) | 29 (78) | 16 | .13 |

| I consistently knew the names of all the interns on the unitf | 13 (33) | 32 (84) | 51 | <.001 | 19 (56) | 36 (97) | 41 | <.001 |

| When hurdles were encountered, all practitioners were able to work through them together | 28 (70) | 35 (92) | 22 | .01 | 29 (85) | 31 (84) | −1 | .86 |

| The input of all clinical practitioners was valued when making decisions about patient care | 21 (53) | 36 (95) | 42 | <.001 | 26 (71) | 31 (84) | 13 | .18 |

| Clinical practitioners on unit were free to raise concerns about patient plans or decisions | 30 (75) | 38 (100) | 25 | .001 | 29 (85) | 35 (95) | 9 | .19 |

| It was easy to discuss difficult issues and problems with clinical practitioners on the floor | 25 (64) | 36 (95) | 31 | .001 | 25 (68) | 33 (92) | 24 | .01 |

| Feedback between individual clinical practitioners was delivered in a way that promotes positive interactions | 24 (60) | 34 (90) | 30 | .003 | 28 (82) | 31 (86) | 4 | .67 |

| Burnout scoreg | 18 (45) | 17 (45) | 0 | .98 | 17 (50) | 19 (51) | 1 | .91 |

Abbreviations: PGY, postgraduate year; RN, registered nurse.

The survey response rates for PGY-1 residents were 100% (15 of 15; survey 1, intervention), 94.4% (17 of 18; survey 1, control), 80% (12 of 15; survey 3, intervention), and 100% (18 of 18; survey 3, control). The survey response rates for nurses were 88.4% (38 of 43; survey 1, intervention), 83.3% (40 of 48; survey 1, control), 86.0% (37 of 43; survey 3, intervention), and 72.3% (34 of 47; survey 3, control).

For survey data, we compared the percentage of respondents choosing the top 2 boxes of a 5-point scale from interns and nursing surveys using χ2 tests. Scale was “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” unless otherwise indicated.

Intern survey No. 1 was administered after the interns’ first rotation on the clinical floor.

Intern survey No. 3 was administered after the interns’ last rotation on the clinical floor (which may have occurred before or after the March-May 2020 COVID-19 survey at the hospital).

Question responses: inferior, below average, average, excellent, outstanding (top 2 boxes).

Question responses: very seldom, seldom, moderate, frequently, very frequently (top 2 boxes).

Burnout score reflects those with a combined score of 4-12 based on 2 questions asked about feeling burned out from work and being callous toward others.19

There was no difference between intervention and control PGY-1s in questions related to psychological safety except intervention PGY-1s were more likely to feel afraid of being judged at the start of the study compared with controls (47% vs 6%; P = .008; Table 419). This effect extinguished on follow-up surveys. Intervention PGY-1s reported frequently to very frequently knowing the names of nurses compared with controls throughout the duration of the study. Although 11 of 12 (92%) interns in the intervention group described their relationship with nursing as excellent to outstanding compared with 14 of 18 (78%) control interns, this was not statistically significant.

In nursing surveys, there was no difference in questions related to psychological safety between the intervention and control groups. In questions related to teamwork and team culture at 6 months, nurses in the intervention group were more likely to describe their relationship with PGY-1s as excellent to outstanding (74% vs 40%; P = .003), to report all practitioners worked together to overcome hurdles (92% vs 70%; P = .01), believed input of all practitioners was valued (95% vs 53%; P < .001), and that feedback between practitioners was positive (90% vs 60%; P = .003) (Table 419). These differences diminished at the 12-month survey. Nurses in the intervention group at both 6 months and 12 months were more likely to know the names of the residents and felt it was easy to discuss difficult issues and problems.

Patient-Related Metrics

There were no differences in patient outcomes, including length of stay, transfer to the intensive care unit, deaths, or discharge disposition.

Discussion

In this randomized trial on the effect of familiarity on interprofessional medical teams, we used simulations of medical events, direct observation of teams, and longitudinal participant surveys to develop an in-depth assessment of team performance and communication. Geographic localization of clinicians and its effect on physician-nurse communication has been published; however, to our knowledge, this study was the first to assess multiple metrics of both team performance and communication in a year-long randomized trial.4,7,12,20 We found that familiar teams performed better on advanced medical simulations, were more likely to have nurses present on patient rounds, and had nurses who reported improved teamwork earlier in the year.

We used simulation as both a training and evaluation tool to mimic realistic interprofessional team problem-solving and communication.15,21 The first simulation performed approximately 6 months into the study found no difference in summative performance metrics. However, in the second simulation, after a year of familiarity, intervention teams were more successful in working together, negotiating with the patient, supporting team members, and convincing the patient to take the ideal dose of insulin.

The improved performance of the intervention teams on the second, more emotionally complex simulation is potentially due to their accumulated learning over the academic year and the translation of group knowledge into task execution.9 This proved consistent with prior research that suggests that collective experiential work may improve a team’s ability to learn, identify, and apply knowledge.22 The benefits may be particularly valuable for teams working in highly complex cognitive situations requiring multiple competing knowledge tasks and especially true to teams with less experienced members, such as trainees and new nurses.9,23

As with other studies on geographic localization of medical teams, we found increased time together allowed individuals to get to know each other, resulting in perceived enhanced communication and familiarty.4,7,12 The nurses and physicians in the intervention group of this study knew each other’s names and time-motion data found intervention teams were more likely to have a nurse present during team rounds. In contrast with existing communication norms, we found familiar teams had more personal conversations, representing an overall shift in communication dynamics. Previous research of standard modes of physician-nurse communication found face-to-face communication to be both rare and terse, and that outside of structured events, interprofessional communication only occurred in 12% of patient cases.24,25 This overall shift in communication dynamics is clinically relevant because poor interprofessional communication has been cited as a root cause of medical errors and collaboration between colleagues is directly tied to improved patient outcomes.3,26,27

Psychological safety is considered an important component of effective teamwork.28 Yet, when queried about aspects of psychological safety, more than 90% of physicians and nurses in both groups chose the top 2 box responses, suggesting that these questions may not be nuanced enough. High response rates to questions on psychological safety were similar to previously published literature on residents.8 It is noteworthy that more residents in the intervention group reported fear of being judged on the first survey, a difference which resolved on subsequent questionaries. Although not clear why, committing to returning to the same floor may have challenged the hierarchy of relationships and the advantage of anonymity, resulting in increased fear.20,29 With the increased familiarity that comes with working together, residents’ fear of being judged waned with time.

The nurses in the intervention group were more likely to describe a positive environment and approach to teamwork within the first 6 months of the study. They reported feeling like a valued team member and more easily discussing difficult clinical issues with practitioners. This matched research on relationship formation between nurses and interns, which identified nurses’ desire to be valued team members and treated with respect.30 The residents in the intervention group in the first month on service committed to learning the nurses’ names, suggesting the knowledge of returning to the floor provided incentive to learning names and thus demonstrated respect. In addition, studies have suggested that nurses more involved in clinical decision-making rate teamwork higher.31

At 6 months, the nurses in the intervention group’s perception of teamwork was significantly higher, suggesting familiarity may help more quickly achieve nursing sense of value, respect, and autonomy with new residents. At 12 months, the nurses in the control group’s assessment of teamwork increased and matched nurses in the intervention group’s responses. This may reflect improved relationships between nurses and interns who were more experienced in interprofessional teamwork in the second half of the study or enhanced team relationships in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. Importantly, these data suggest, in the formation of teams with inexperienced parties, there was a critical period when familiarity was crucial; however, the effect of familiarity may have waned as general work experience accumulated.

Limitations

This study had limitations. It was performed at a single institution with a small number of physician participants, which may have limited detection of statistically significant differences in some study measures. Similarly, we did not see a difference in patient-related outcomes likely because of the sample size. The study was interrupted because of COVID-19, and team dispersion may have influenced the treatment effect. The number of simulations available for rating was limited by study size and technical difficulties. The NOTECHS scale adapted to assess simulation was designed for nontechnical teamwork in the operating room and may have not translated as well to teamwork in medical patient encounters. We were not powered to do multiple group comparisons between outcomes, and the interrater reliability of simulation reviewers was only moderate, which may have affected the results. In addition, survey results are subject to recall bias, and later surveys may have been affected by the pandemic.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this randomized clinical trial was one of the first of its kind to evaluate the effect of familiarity on interprofessional team performance in both a real medical environment and in structured performance evaluations. Despite limitations, the results emphasized the important relationship between familiarity and team performance and suggest both early and late benefits. Factors that promote team familiarity should be considered when staffing and building medical teams, especially in training programs.

Trial Protocol.

eMethods 1. Pre-briefing script for simulation

eMethods 2. Simulation 1

eMethods 3. Simulation 2

eMethods 4. Intern Survey

eMethods 5. Nurses Survey

eTable. Time Motion Results

Data Sharing Statement.

References

- 1.Reader TW, Flin R, Cuthbertson BH. Communication skills and error in the intensive care unit. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13(6):732-736. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282f1bb0e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N, et al. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients—results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):377-384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199102073240605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutcliffe KM, Lewton E, Rosenthal MM. Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186-194. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200402000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Leary KJ, Wayne DB, Landler MP, et al. Impact of localizing physicians to hospital units on nurse-physician communication and agreement on the plan of care. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(11):1223-1227. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1113-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edmondson AC. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm Sci Q. 1999;44(2):350-383. doi: 10.2307/2666999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weller J, Frengley R, Torrie J, et al. Evaluation of an instrument to measure teamwork in multidisciplinary critical care teams. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(3):216-222. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.041913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams A, DeMott C, Whicker S, et al. The impact of resident geographic rounding on rapid responses. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(7):1077-1078. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05012-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Torralba KD, Loo LK, Byrne JM, et al. Does psychological safety impact the clinical learning environment for resident physicians: results from the VA’s Learners’ Perceptions Survey. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):699-707. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00719.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Staats BR, Gino F, Pisano GP. Varied experience, team familiarity, and learning: the mediating role of psychological safety. January 2009. Accessed August 26, 2022. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/46475748_Varied_Experience_Team_Familiarity_and_Learning_The_Mediating_Role_of_Psychological_Safety

- 10.Huang KT, Minahan J, Brita-Rossi P, et al. All together now: impact of a regionalization and bedside rounding initiative on the efficiency and inclusiveness of clinical rounds. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(3):150-156. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S, Tarima S, Rana V, et al. Impact of localizing general medical teams to a single nursing unit. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(7):551-556. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bryson C, Boynton G, Stepczynski A, et al. Geographical assignment of hospitalists in an urban teaching hospital: feasibility and impact on efficiency and provider satisfaction. Hosp Pract (1995). 2017;45(4):135-142. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2017.1353884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudolph JW, Raemer DB, Simon R. Establishing a safe container for learning in simulation: the role of the presimulation briefing. Simul Healthc. 2014;9(6):339-349. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sevdalis N, Davis R, Koutantji M, Undre S, Darzi A, Vincent CA. Reliability of a revised NOTECHS scale for use in surgical teams. Am J Surg. 2008;196(2):184-190. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.08.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicksa GA, Anderson C, Fidler R, Stewart L. Innovative approach using interprofessional simulation to educate surgical residents in technical and nontechnical skills in high-risk clinical scenarios. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(3):201-207. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.2235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mishra A, Catchpole K, McCulloch P. The Oxford NOTECHS System: reliability and validity of a tool for measuring teamwork behaviour in the operating theatre. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(2):104-108. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.024760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159-174. doi: 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henkin S, Chon TY, Christopherson ML, Halvorsen AJ, Worden LM, Ratelle JT. Improving nurse-physician teamwork through interprofessional bedside rounding. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:201-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Single item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization are useful for assessing burnout in medical professionals. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(12):1318-1321. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1129-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh S, Fletcher KE. A qualitative evaluation of geographical localization of hospitalists: how unintended consequences may impact quality. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1009-1016. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2780-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riskin A, Erez A, Foulk TA, et al. The impact of rudeness on medical team performance: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;136(3):487-495. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis K, Lange D, Gillis L. Transactive memory systems, learning, and learning transfer. Organ Sci. 2005;16(6):581-598. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1050.0143 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kearney E, Gebert D, Voelpel SC. When and how diversity benefits teams: the importance of team members’ need for cognition. Acad Manage J. 2009;52:581-598. doi: 10.5465/amj.2009.41331431 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zwarenstein M, Rice K, Gotlib-Conn L, Kenaszchuk C, Reeves S. Disengaged: a qualitative study of communication and collaboration between physicians and other professions on general internal medicine wards. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:494. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crumlish CM, Yialamas MA, McMahon GT. Quantification of bedside teaching by an academic hospitalist group. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(5):304-307. doi: 10.1002/jhm.540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(suppl 1):i85-i90. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.010033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baggs JG, Schmitt MH, Mushlin AI, et al. Association between nurse-physician collaboration and patient outcomes in three intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(9):1991-1998. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199909000-00045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinberg DB, Cooney-Miner D, Perloff JN, Babington L, Avgar AC. Building collaborative capacity: promoting interdisciplinary teamwork in the absence of formal teams. Med Care. 2011;49(8):716-723. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318215da3f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lemieux-Charles L, McGuire WL. What do we know about health care team effectiveness: a review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(3):263-300. doi: 10.1177/1077558706287003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pugsley L, Frey-Vogel AS, Dzara K. A qualitative investigation to identify factors influencing relationship formation between pediatric nurses and pediatric interns. J Interprof Educ Pract. 2021;22(8):100404. doi: 10.1016/j.xjep.2020.100404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rafferty AM, Ball J, Aiken LH. Are teamwork and professional autonomy compatible, and do they result in improved hospital care? Qual Health Care. 2001;10(suppl 2):ii32-ii37. doi: 10.1136/qhc.0100032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol.

eMethods 1. Pre-briefing script for simulation

eMethods 2. Simulation 1

eMethods 3. Simulation 2

eMethods 4. Intern Survey

eMethods 5. Nurses Survey

eTable. Time Motion Results

Data Sharing Statement.