Abstract

Introduction

A 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) was licensed to protect against emerging Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes. Healthcare services, including routine childhood immunizations, were disrupted as a result of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). This study compared PCV13 routine vaccination completion and adherence among US infants before and during the COVID-19 pandemic and the relationship between primary and booster dose completion and adherence.

Methods

Retrospective data from Optum’s de-identified Clinformatics® Data Mart were used to create three cohorts using data collected between January 2017 and December 2020: cohort 1 (C1), pre-COVID; cohort 2 (C2), cross-COVID; and cohort 3 (C3), during COVID. Study endpoints were completion and adherence to the primary PCV13 series (analyzed using univariate logistic regression) and completion of and adherence to the booster dose (analyzed descriptively).

Results

The analysis included 142,853 infants in C1, 27,211 infants in C2, and 53,306 infants in C3. Among infants with at least 8 months of follow-up from birth, three-primary-dose completion (receipt of all three doses within 8 months after birth) and adherence (receipt of doses at recommended times) were significantly higher before (C1 and C2) versus during (C3) COVID-19 (odds ratio [OR] 1.12 [95% confidence interval [CI] 1.07, 1.16] and OR 1.10 [95% CI 1.05, 1.15], respectively). A significantly higher percentage of infants received a booster dose before versus during COVID-19 (83.2% vs. 80.2%; OR 1.23; 95% CI 1.17, 1.29); similarly, booster dose adherence was higher before than during COVID-19 (51.2% vs. 47.4%; OR 1.17; 95% CI 1.13, 1.21). The odds of booster dose completion were 8.26 (95% CI 7.92, 8.60) and 7.90 (95% CI 7.14, 8.74) times as likely in infants who completed all three primary doses than in infants who did not complete primary doses before COVID-19 and during COVID-19, respectively.

Conclusions

PCV13 full completion was lower during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with pre-pandemic (79.0% vs. 77.1%).

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40121-022-00699-5.

Keywords: Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, Completion, Adherence, COVID-19, Pediatric vaccination

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Healthcare services, including routine well-child visits and childhood immunizations, were disrupted as a result of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). |

| This study compared routine vaccination completion and adherence of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) among US infants before and during the COVID-19 pandemic and the relationship between primary dose and booster dose completion and adherence. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Among infants with at least 8 months of follow-up from birth, three-primary-dose completion (79.0% vs. 77.1%) and adherence (9.9% vs. 9.1%) were statistically significantly higher before compared with during COVID-19. |

| Among US infants, rates of PCV13 completion and adherence were statistically lower during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with before the pandemic, and primary series completion and adherence were associated with higher booster completion and adherence. |

Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) is a major cause of pneumonia, bacteremia, meningitis, and acute otitis media among children worldwide [1, 2]. Before the routine use of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCVs) in the USA, a substantial burden of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) was observed in children less than 5 years of age; approximately 17,000 cases of IPD and 200 related deaths occurred annually, and children who suffered with certain chronic medical conditions were at increased risk [2, 3].

Following the implementation of routine vaccination with the seven-valent PCV (PCV7) among infants and children in the USA in 2000, the incidence of IPD dropped sharply in both vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals [4]. In 2010, a 13-valent PCV (PCV13) was licensed to protect against emerging serotypes not covered in PCV7, and consequently the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended replacement of PCV7 with PCV13 and provision of PCV13 as a 3 + 1 dose schedule (a three-dose primary series at 2, 4, and 6 months of age, and booster dose at 12–15 months of age) to infants and young children in the USA [5]. These recommendations are consistent with current guidelines [6]. After the introduction of PCV13 into the childhood immunization program, the annual incidence of IPD in the USA continued to decline, from 22 per 100,000 in 2009 to 7 per 100,000 in 2018 among children less than 5 years of age [7, 8]. By 2012, childhood vaccination with PCV13 was associated with a 21% reduction in hospital admissions due to all-cause pneumonia among children less than 2 years of age [9]. Between 2011 and 2016, annual reductions in the incidence of acute otitis media were also observed among children 9 years of age or younger in the USA, with an overall reduction of 25% over this period [10]. Similar to those observed with PCV7, indirect effects of PCV13 infant vaccination were also observed among unvaccinated adults [11, 12].

Infants are at higher risk of pneumococcal disease than children in other age groups [13]. Adherence to age-appropriate recommended vaccination dosing schedule is essential for ensuring full protection against vaccine-preventable disease. For PCV13, the current 3 + 1 dose schedule was recommended by ACIP on the basis of accumulating evidence, including clinical efficacy and effectiveness demonstrated by 3 + 1 dose schedule of PCV7 and a greater immune response induced by three-dose schedule of PCV13 than a two-dose schedule for most serotypes and that a booster dose further enhances the immune response and affords greater long-term protection against IPD [2, 5, 14–17]. Additionally, delaying completion of the primary series may place young infants at increased risk for disease [14]. According to the most recent CDC National Immunization Survey of children born between 2017 and 2018, 92.4% had received at least three doses of PCV13 and only 82.3% had received four doses or more by 24 months of age [18]. Although PCV13 vaccination coverage is higher than for some other ACIP-recommended childhood vaccines (e.g., hepatitis A, rotavirus, and influenza [two doses or more]) [18], coverage does not meet the goal set by the US Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (Healthy People 2020), which targets at least 90% of children 19 to 35 months of age receiving all four PCV13 doses [19].

On March 13, 2020, the USA declared a national state of emergency concerning coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, mitigation measures, such as social distancing and stay-at-home orders, were put in place to prevent the community spread of the disease. Nearly all aspects of society have been disrupted since then, including healthcare services such as routine well-child visits and childhood immunizations [20]. For example, data from the CDC indicated a steep decline in physician orders of ACIP-recommended non-influenza childhood vaccines after the national emergency was declared [20].

The aims of the study were to compare PCV13 routine vaccination completion and adherence among US infants before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the relationship between primary dose and booster dose completion and adherence. The potential effects of demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical factors on changes in vaccination completion and adherence during the COVID-19 era were also evaluated.

Methods

Study Design and Data Source

This retrospective, observational, longitudinal cohort study was performed using de-identified data from the Optum Clinformatics® Data Mart (CDM) database. The CDM is derived from an administrative commercial claims database for members of commercial and Medicare Advantage health plans. The database includes enrollees from all 50 US states. In addition to medical and pharmacy claims, the CDM contains information on patient characteristics. Because all patient-level data in this database were de-identified, use for health services research was fully compliant with US federal law and, accordingly, institutional review board/ethical approval was not needed. The study was conducted in accordance with legal and regulatory requirements, as well as with scientific purpose, value, and rigor and followed generally accepted research practices described in Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices issued by the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology [21] and Good Practices for Outcomes Research issued by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research [22].

Study Periods and Study Population

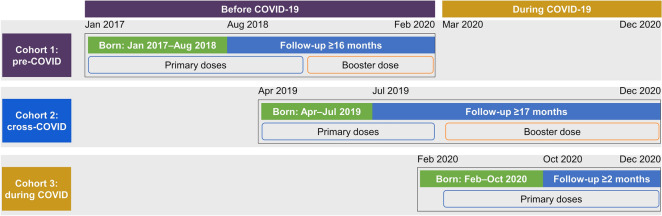

The study population comprised three cohorts (Fig. 1). Study cohort 1 (pre-COVID) included participants born between January 1, 2017 and August 31, 2018 who were scheduled to complete both the PCV13 primary series and booster dose by the end of February 2020, before COVID-19, according to ACIP recommendations. Study cohort 2 (cross-COVID) included participants born between April 1, 2019 and July 31, 2019 who were scheduled to have their primary series before COVID-19 (by the end of February 2020) and to have their booster during the COVID-19 era, between March and December 2020. Study cohort 3 (during COVID) included participants born between February 1, 2020 and October 31, 2020 who were scheduled to complete at least one dose of the PCV13 primary series by the end of December 2020.

Fig. 1.

Study cohorts. COVID/COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019

The study index date was defined as the date of the first healthcare encounter for care of newborns 28 days of age or younger. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth and Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis and current procedural terminology codes indicating newborn and neonatal healthcare encounters (e.g., routine examinations, neonatal care) were used to assign index dates (Supplemental Table 1). Across all three cohorts, a minimum follow-up period of 42 days was required for inclusion in the study. Infants were followed for up to 20 months or until they were lost to follow-up or died, whichever occurred first. Infants were excluded if they were identified as coming from the same household or family.

Endpoints of Interest

Study endpoints were completion of and adherence to the primary PCV13 series and completion of and adherence to the booster dose. Completion of the primary series was defined as receiving all three doses in the series within the first 8 months (42–245 days) after birth; partial completion was defined as receiving one or two doses. Adherence to the primary series was defined as receiving the doses (one, two, or all three) according to the dosing schedule recommended by ACIP (at 2, 4, and 6 months of age; at 42–65, 85–125, and 145–185 days, respectively). Completion of the booster dose was defined as receiving a booster within 12–18 months of age (between 335 and 545 days), and adherence to the booster dose was defined as receiving a booster within 12–15 months of age (between 335 and 455 days), as recommended by ACIP.

Disparity analyses were also performed in this study that evaluated the effects of demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics on the aforementioned endpoints to determine whether PCV13 vaccination rates were disproportionately affected by COVID-19 within certain subgroups. Characteristics of interest included sex, parent/caregiver age, race/ethnicity, US census division, insurance type, number of children in the household, median neighborhood education level (per census block), and household annual income. Analysis was also performed according to whether infants had any medical conditions putting them at increased risk of pneumococcal disease. Three risk groups were evaluated: (1) sickle cell disease, asplenia, HIV, or cancer; (2) diabetes type 1 or 2; nephrotic syndrome; chronic heart, lung, or kidney disease; or cerebrospinal fluid leaks; and (3) birth defects, preterm birth, or low birth weight.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics were summarized using means and standard deviations or medians and ranges for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. No statistical hypotheses were formulated because the analyses were primarily descriptive.

For the analyses on completion of and adherence to the primary series, univariate logistic regression was conducted to calculate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI of primary dose completion or adherence in cohorts 1 and 2 (pre-COVID and cross-COVID, respectively) versus cohort 3 (during COVID). Descriptive analyses were performed to describe booster dose completion and adherence in relation to primary dose completion and adherence.

To explore disparities, multivariable binomial logistic regression was used to calculate ORs and 95% CIs of full completion versus not full (partial completion [one or two doses] or no vaccine) adjusting for demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics. Final multivariable models were generated using backward stepwise selection and a 0.10 significance level. To compare the odds of full completion of the primary PCV13 series before and during COVID-19 in different subgroups, separate logistic regression models were generated, including the cohort indicator, the characteristic, and their interaction. Analyses were performed using non-missing observations for each characteristic, except for number of children in household, race/ethnicity, neighborhood education level, and annual household income, where missing categories were included.

Results

Participants

There were 142,853 infants in cohort 1 (pre-COVID), 27,211 infants in cohort 2 (cross-COVID), and 53,306 infants in cohort 3 (during COVID; Table 1, Supplemental Fig. 1) extracted on the basis of the study criteria. Across all three cohorts, nearly all participants (more than 97%) had at least 2 months of follow-up. Percentages of participants with sufficient follow-up to assess primary dose series completion (at least 8 months) were 76.9%, 27.8%, and 73.7% across cohorts 1 to 3, respectively. In cohorts 1 and 3, 55.7% and 44.5% of participants, respectively, had sufficient follow-up to assess booster dose completion (at least 18 months).

Table 1.

Social and demographic characteristics of infants in cohorts 1, 2, and 3

| Characteristica | Cohort 1: Pre-COVID-19 (n = 142,853) |

Cohort 2: Cross-COVID-19 (n = 27,211) |

Cohort 3: During COVID-19 (n = 53,306) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of follow-up, days | |||

| Mean (SD) | 445.5 (195.4) | 426.5 (186.5) | 185.4 (80.0) |

| ≥ 65 (2 months) | 97.6 | 98.0 | 97.2 |

| ≥ 125 (4 months) | 90.4 | 91.6 | 71.3 |

| ≥ 185 (6 months) | 83.2 | 83.0 | 47.7 |

| ≥ 245 (8 months) | 76.9 | 73.7 | 27.8 |

| ≥ 455 (15 months) | 61.2 | 60.0 | 0.0 |

| ≥ 545 (18 months) | 55.7 | 44.5 | 0.0 |

| Caregiver age | |||

| Mean (SD), years | 32.5 (4.8) | 32.5 (4.8) | 32.5 (4.8) |

| ≤ 24 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 3.8 |

| 25–34 | 64.4 | 63.8 | 63.9 |

| ≥ 35 | 31.8 | 32.2 | 32.2 |

| Missing/unknown | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 51.2 | 51.8 | 51.5 |

| Female | 48.8 | 48.2 | 48.5 |

| Other/unknown | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 9.4 | 7.9 | 7.1 |

| Black | 7.0 | 6.3 | 6.4 |

| Hispanic | 11.7 | 11.0 | 9.9 |

| White | 67.1 | 60.1 | 56.9 |

| Multiple | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 |

| Missing/unknown | 4.8 | 14.7 | 19.7 |

| Census division | |||

| East North Central | 15.8 | 14.7 | 15.2 |

| East South Central | 3.5 | 3.4 | 3.6 |

| Middle Atlantic | 7.5 | 7.4 | 7.3 |

| Mountain | 11.5 | 11.8 | 11.4 |

| New England | 2.5 | 3.0 | 2.8 |

| Pacific | 10.5 | 10.8 | 10.2 |

| South Atlantic | 19.8 | 20.8 | 20.9 |

| West North Central | 12.7 | 13.3 | 13.9 |

| West South Central | 15.6 | 14.5 | 14.4 |

| Multiple | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Other/unknown | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Insurance type | |||

| EPO | 10.4 | 11.6 | 11.4 |

| PPO or POS | 79.1 | 77.6 | 77.5 |

| HMOb | 10.5 | 10.8 | 11.1 |

| Unknown | < 0.1 | < 0.1 | < 0.1 |

| Number of children in household | |||

| 1 | 38.2 | 43.7 | 43.9 |

| 2 | 38.1 | 28.5 | 24.7 |

| ≥ 3 | 20.6 | 14.8 | 13.3 |

| Missing/unknown | 3.1 | 13.0 | 18.1 |

| Neighborhood education level, medianc | |||

| High school or less | 12.1 | 11.3 | 10.6 |

| Less than bachelor degree | 51.7 | 46.7 | 44.1 |

| Bachelor degree or higher | 32.9 | 28.9 | 27.0 |

| Missing/unknown | 3.3 | 13.2 | 18.3 |

| Household income, USD | |||

| < 40,000 | 8.1 | 7.9 | 7.9 |

| 40,000–74,000 | 18.0 | 16.9 | 16.5 |

| 75,000–99,000 | 12.6 | 11.9 | 10.8 |

| ≥ 100,000 | 45.7 | 37.3 | 34.4 |

| Missing/unknown | 15.5 | 25.9 | 30.4 |

| With sickle cell disease, asplenia, HIV, or cancer | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| With diabetes; nephrotic syndrome; chronic heart, lung, or kidney disease; or CSF | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.4 |

| Had birth defects, preterm birth, or low birth weight | 14.4 | 14.8 | 14.3 |

COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, EPO exclusive provider organization, HMO health maintenance organization, POS point of service, PPO preferred provider organization

aData are presented as percentages unless otherwise noted

bIncludes HMO, indemnity insurance, and other

cData from US census block

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics were relatively comparable across the three cohorts (Table 1). Approximately 51% of infants were male, and the mean age of parents/caregivers was approximately 32 years. The majority of infants were White (cohort percentages ranged from 56.9% to 67.1%); 7.1–9.4% were Asian, 6.3–7.0% were Black, and 9.9–11.7% were Hispanic. Across the three cohorts, 10.6–12.1% of participants had a neighborhood education level of high school completion or less per census block median value, and 34.4–45.7% of participants had an annual household income of at least 100,000 USD. Most infants were from families with one child (38.2–43.9%) or two children (24.7–38.1%).

Dose Completion and Adherence

The percentage of infants who completed the full three-dose primary series was higher before COVID-19 (79.0% in cohorts 1 and 2) than during COVID-19 (77.1% in cohort 3; OR 1.12; 95% CI 1.07, 1.16; Table 2). Before COVID-19, infants were also more likely to have full adherence to the primary dosing schedule (9.9% before COVID-19 vs. 9.1% during COVID-19; OR 1.10; 95% CI 1.05, 1.15). The percentage of infants who received a booster dose was significantly higher before COVID-19 than during COVID-19 (83.2% vs. 80.2%; OR 1.23; 95% CI 1.17, 1.29; Table 3); similarly, booster dose adherence was higher before COVID-19 than during COVID-19 (51.2% vs. 47.4%; OR 1.17; 95% CI 1.13, 1.21).

Table 2.

Primary dose completion and adherence before and during COVID-19

| Cohorts 1 & 2: Before COVID-19, n (%) | Cohort 3: During COVID-19, n (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI), before COVID-19 vs. during COVID-19 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary dose completion | |||

| Na | 129,868 | 14,808 | |

| Full completion | 102,533 (79.0) | 11,413 (77.1) | 1.12 (1.07, 1.16) |

| ≥ 2 doses | 117,637 (90.6) | 13,180 (89.0) | 1.19 (1.12, 1.25) |

| ≥ 1 dose | 121,915 (93.9) | 13,702 (92.5) | 1.24 (1.16, 1.32) |

| Primary dose adherence | |||

| Nb | 141,483 | 25,442 | |

| Full adherence | 13,980 (9.9) | 2311 (9.1) | 1.10 (1.05, 1.15) |

| ≥ 2 doses | 54,421 (38.5) | 9957 (39.1) | 0.97 (0.95, 1.00) |

| ≥ 1 dose | 105,464 (74.5) | 18,947 (74.5) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) |

| Individual dose adherence | |||

| Nc | 166,104 | 51,822 | |

| First dose adherence | 95,013 (57.2) | 29,370 (56.7) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) |

| Nd | 154,116 | 38,002 | |

| Second dose adherence | 59,972 (38.9) | 14,565 (38.3) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.05) |

| Nb | 141,483 | 25,442 | |

| Third dose adherence | 37,187 (26.3) | 6147 (24.2) | 1.12 (1.08, 1.15) |

COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019

aParticipants with ≥ 245 days follow-up

bParticipants with ≥ 185 days follow-up

cParticipants with ≥ 65 days follow-up

dParticipants with ≥ 125 days follow-up

Table 3.

Booster dose completion and adherence before and during COVID-19

| Booster dose | Cohorts 1 & 2: Before COVID-19 | Cohort 3: During COVID-19 | Odds ratio (95% CI), before COVID-19 vs. during COVID-19 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completion, Na | 79,552 | 12,116 | |

| Completion, n (%) | 66,226 (83.2) | 9720 (80.2) | 1.23 (1.17, 1.29) |

| Adherence, Nb | 87,454 | 16,313 | |

| Adherence, n (%) | 44,818 (51.2) | 7728 (47.4) | 1.17 (1.13, 1.21) |

COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019

aParticipants with ≥ 545 days follow-up

bParticipants with ≥ 455 days follow-up

Among infants who completed the booster dose, 86.6% and 87.9% completed primary dosing series before COVID and cross-COVID, respectively; among infants who did not complete the booster dose, 43.9% and 48.0% completed the primary dosing series (Table 4). The odds of booster dose completion were 8.26 (95% CI 7.92, 8.60) and 7.90 (95% CI 7.14, 8.74) times as likely in infants who completed all three primary doses than in infants who did not complete all three primary doses before COVID-19 and cross-COVID-19, respectively. Additionally, booster dose adherence was significantly higher in infants who completed all three primary doses than in infants who did not complete all three primary doses before COVID-19 (OR 2.34; 95% CI 2.27, 2.43) and cross-COVID-19 (OR 2.74; 95% CI 2.52, 2.97; Table 5). Booster dose completion and adherence were also higher in infants who adhered to all three primary doses.

Table 4.

Associations between primary completion and adherence and booster dose completion: likelihood of booster dose completion before and during COVID-19 given different levels of primary dose completion and adherence

| Cohort 1: Before COVID-19 | Cohort 2: Cross-COVID-19 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Booster dose completed, % (N = 66,226) | Booster dose not completed, % (N = 13,326) | Odds ratio (95% CI): booster dose completed vs. not completed | Booster dose completed, % (N = 9720) | Booster dose not completed, % (N = 2396) |

Odds ratio (95% CI): booster dose completed vs. not completed |

|

| Primary dose completion | ||||||

| All 3 doses | 86.6 | 43.9 | 8.26 (7.92, 8.60) | 87.9 | 48.0 | 7.90 (7.14, 8.74) |

| 2 doses only | 10.4 | 17.5 | 0.54 (0.52, 0.57) | 9.5 | 13.6 | 0.67 (0.58, 0.76) |

| 1 dose only | 2.1 | 8.8 | 0.22 (0.21, 0.24) | 1.9 | 5.9 | 0.31 (0.24, 0.38) |

| Primary dose adherence | ||||||

| All 3 doses | 11.5 | 4.6 | 2.68 (2.46, 2.92) | 8.2 | 3.8 | 2.24 (1.79, 2.79) |

| 2 doses only | 31.1 | 19.0 | 1.93 (1.84, 2.02) | 30.5 | 17.2 | 2.11 (1.88, 2.36) |

| 1 dose only | 37.1 | 29.4 | 1.42 (1.36, 1.47) | 39.5 | 28.7 | 1.62 (1.47, 1.78) |

COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019

Table 5.

Association between primary completion and adherence and booster dose adherence: likelihood of booster dose adherence before and during COVID-19 given different levels of primary dose completion and adherence

| Cohort 1: before COVID-19 | Cohort 2: cross-COVID-19 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Booster dose adhered, % (N = 44,818) | Booster dose not adhered, % (N = 42,636) | Odds ratio (95% CI): booster dose adhered vs. not adhered | Booster dose adhered, % (N = 7728) | Booster dose adhered, % (N = 8585) | Odds ratio (95% CI): booster dose adhered vs. not adhered | |

| Primary dose completion | ||||||

| All 3 doses | 86.0 | 72.3 | 2.34 (2.27, 2.43) | 88.0 | 72.7 | 2.74 (2.52, 2.97) |

| 2 doses only | 10.7 | 12.6 | 0.84 (0.80, 0.87) | 9.5 | 11.0 | 0.85 (0.77, 0.94) |

| 1 dose only | 2.3 | 4.3 | 0.53 (0.49, 0.57) | 1.9 | 3.5 | 0.52 (0.43, 0.64) |

| Primary dose adherence | ||||||

| All 3 doses | 11.5 | 9.1 | 1.29 (1.23, 1.35) | 7.4 | 6.1 | 1.21 (1.07, 1.37) |

| 2 doses only | 30.8 | 27.0 | 1.20 (1.17, 1.24) | 29.2 | 25.1 | 1.23 (1.14, 1.31) |

| 1 dose only | 37.1 | 34.7 | 1.11 (1.08, 1.14) | 40.0 | 35.9 | 1.19 (1.12, 1.27) |

COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019

Disparity Analyses

Overall, adjusting for COVID-19, the vaccine completion rates varied according to demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics (Fig. 2). Compared with infants who completed the full vaccination schedule, those who either partially completed or did not receive the vaccine were more likely to be Black, have parents/caregivers less than 25 years of age, come from households with at least two children and less than 100,000 USD in annual income, and come from neighborhoods with a median education level of high school or less. The highest likelihood of full completion was observed among infants in the West North Central region of the USA, and the lowest likelihood was observed in New England. In the analysis of medical comorbidities, infants were significantly less likely to complete the full vaccination series if they had sickle cell disease; asplenia; HIV; cancer; diabetes; nephrotic syndrome; chronic heart, lung, or kidney disease; birth defects; preterm birth; or low birth weight. In the multivariable models including demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics comparing full versus partial or no adherence, trends were similar to those observed with full completion with respect to age, number of children, household income, and medical comorbidities (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Adjusted odds ratios (95% CI) of PCV13 primary series full completion: likelihood of PCV13 primary series full completion according to demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics. Odds ratios were obtained from a multivariable model after backward stepwise selection. Infants with a minimum of 245 days of follow-up are included in the model; missing/unknown categories for race/ethnicity, number of children in household, neighborhood educational level, and household income are not presented. aHigh risk group with sickle cell disease, asplenia, HIV, or cancer. N = 143,865. bHigh risk group with diabetes type 1 or 2, nephrotic syndrome, chronic heart, lung, or kidney disease, or cerebrospinal fluid leaks. cHigh risk group with birth defects, preterm, or low birth weight. COVID/COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, EPO exclusive provider organization, HMO health maintenance organization, PCV13 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, POS point of service, PPO preferred provider organization

Fig. 3.

Adjusted odds ratios (95% CI) of PCV13 primary series full adherence: likelihood of PCV13 primary series full adherence according to demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics. Odds ratios were obtained from a multivariable model after backward stepwise selection. Infants with a minimum of 185 days of follow-up are included in the model; missing/unknown categories for number of children in household, neighborhood educational level, and household income are not presented. N = 166,026. aHigh risk group with sickle cell disease, asplenia, HIV, or cancer. bHigh risk group with diabetes type 1 or 2, nephrotic syndrome, chronic heart, lung, or kidney disease, or cerebrospinal fluid leaks. cHigh risk group with birth defects, preterm, or low birth weight. COVID/COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, PCV13 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

The effect of COVID-19 on PCV13 series completion varied according to demographic and socioeconomic characteristics (Fig. 4), with COVID-19 having the greatest impact on infants from households with two children and annual income of at least 100,000 USD. Regionally, the greatest effects of COVID-19 on series completion were observed in New England and the Mountain and Pacific census divisions. Vaccination rates were also higher before COVID compared with during COVID among those who were White, had a primary parent/caregiver at least 25 years of age, and were from neighborhoods with greater than high school education levels.

Fig. 4.

Odds ratios (95% CI) of PCV13 primary series full completion before vs. during COVID by demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics. Infants with a minimum of 245 days of follow-up are included; missing/unknown categories for race/ethnicity, number of children in household, neighborhood educational level, and household income are not presented. Odds ratios were obtained from models including cohort, characteristic, and their interaction, with no further adjustment. aWith (high risk) or without (low risk) sickle cell disease, asplenia, HIV, or cancer. bWith (high risk) or without (low risk) diabetes type 1 or 2, nephrotic syndrome, chronic heart, lung, or kidney disease, or cerebrospinal fluid leaks. cWith (high risk) or without (low risk) birth defects, preterm, or low birth weight. COVID/COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, EPO exclusive provider organization, HMO health maintenance organization, IND indemnity, OTH other, PCV13 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, POS point of service, PPO preferred provider organization

Discussion

In this study of commercially insured US infants, small but statistically significant reductions in rates of PCV13 series completion and adherence were observed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Decreases were consistent across primary series and booster dose completion and adherence. Furthermore, booster completion and adherence were also significantly more likely among infants who had completed or adhered to the three-dose primary series. This observation highlights the importance of primary dose series completion or adherence as a critical factor impacting booster dose completion and adherence.

Demographic and socioeconomic disparities in PCV13 uptake before COVID-19 were generally consistent with disparities in uptake during COVID-19, with a lower likelihood of series completion among those who were Black, had a household income of less than 100,000 USD, and were from neighborhoods with lower median education levels. However, declines in vaccine completion rates during the COVID-19 era were primarily observed in those with household incomes of at least 100,000 USD. These results are consistent with previous reports in the USA and elsewhere indicating that the use of basic medical care, including routine childhood immunizations, decreased during the COVID-19 era [20, 23, 24]. These declines may be related to a variety of factors, including stay-at-home orders, parental fears of their children contracting COVID-19, shifting priorities among healthcare providers and facilities, and logistical issues, such as vaccine transport delays. Global estimates suggest that approximately 80 million children from more than 68 countries worldwide have likely been affected by these delays in immunization, which may have substantial consequences for the global burden of vaccine-preventable infectious diseases, such as IPD [24]. Although breakthrough infections may occur as a result of lower uptake of or adherence to PCV13 and potentially other routine vaccines, declines in the incidence of IPD, streptococcal pharyngitis, and acute otitis media in US children during the COVID-19 pandemic have been observed, presumably attributable to school closures, quarantines, and other measures taken to prevent COVID-19 transmission [25–27]. Although levels of IPD remain lower in 2022 (cumulative year-to-date week 24: aged less than 5 years, n = 313; all ages, n = 6327) compared with pre-pandemic levels (2019 cumulative year-to-date week 24: aged less than 5 years, n = 461; all ages, n = 10,184), they are higher compared with IPD levels in 2021 (cumulative year-to-date week 24: aged less than 5 years, n = 188; all ages, n = 3940) [28]. As this increasing trend continues, we will only begin to understand the effects of decreased uptake of PCV13 on the rate of infection in the near future.

Health inequities in PCV13 primary series completion and other childhood vaccines existed before COVID-19 and have remained during the pandemic [29–31]. For example, rates of series completion with diphtheria, tetanus toxins, and acellular pertussis (DTaP); Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib); and rotavirus vaccines have historically been lower among non-Hispanic Black children compared with non-Hispanic White children, and among children from families below the poverty level [30]. Similarly, lower rates of series completion with DTaP, Hib, rotavirus, and other childhood vaccines have been reported among children living outside of metropolitan areas and those with Medicaid or no insurance [32]. Such disparities have often been attributed to economic, psychological, and access-related barriers, and various strategies to improve uptake have been proposed, such as reminders/recall systems, provider and parent education, patient outreach/home visits, walk-in and after-hours vaccination clinics, and provision of vaccines free of charge/Vaccines for Children programs [30, 32, 33].

In contrast to disparities in vaccine uptake in general, our results suggest that during the COVID-19 pandemic, groups traditionally considered to have greater access to healthcare (e.g., those who are White, have higher household income, and have a higher neighborhood education level) experienced a greater impact on the declines in vaccine uptake observed during the COVID-19 era. This was unexpected because it is inconsistent with the common observation that COVID-19 has had a disproportionately large impact on traditionally disadvantaged demographic groups. Specifically, individuals of Black and Latino race/ethnicity, women, and low-income families have faced greater hardships in the USA during COVID-19 compared with other racial/ethnic groups, men, and high-income families [31, 34, 35]. Additionally, many of these individuals are essential workers and therefore play a critical role in the economy [34]. Because these groups of people were more likely to have had jobs that required them to travel to work outside of the home, they may have been less likely to view bringing children for vaccinations as an unnecessary exposure risk than people with certain jobs who were able to work from home and avoid travel. Another possible explanation for the results observed here is that because PCV13 uptake was already lower among traditionally disadvantaged groups before COVID-19, it was less likely to decline further among those groups. Additionally, low-income families who managed to prioritize childhood immunizations despite economic and social barriers may have been highly motivated to continue to do so during the pandemic. Further research is warranted to determine the most likely driver of these observations.

Strengths of this study included the use of the large CDM database, which allowed access to several relevant sociodemographic and clinical factors as well as vaccine uptake data. Use of the CDM also posed limitations, given that data were retrospective and limited to secondary database research capturing only a portion of the commercially insured US population. As such, the analyses were unable to consider the potential effects of factors not captured in the databases, such as accessibility to healthcare and attitudes toward vaccination, on vaccine uptake and adherence. Additionally, individual patient files were not reviewed to confirm medical or vaccination history because of patient privacy and data protection imperatives. Information on race/ethnicity was available in the mutually exclusive categories of Asian, Black, Hispanic, White, or missing, which may misclassify individuals falling into two or more racial/ethnic groups.

Conclusion

Results from this study indicated that PCV13 full series completion among infants was lower during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with pre-pandemic (79.0% versus 77.1%). The difference was small but statistically significant (OR 1.12; 95% CI 1.07, 1.16). Infants who completed or adhered to all three doses of the primary series were significantly more likely to complete and adhere to the booster dose. The socioeconomic disparities in PCV13 uptake that existed before COVID-19 continued during the pandemic, but effects of COVID-19 on PCV13 uptake were primarily observed among those with traditionally greater access to healthcare. Further research is warranted as structured data sets mature to capture the full time span of COVID-19 mitigation measures.

This study furthers our understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic impact on all other ACIP routinely recommended pediatric vaccines and the findings will help inform strategies aimed at reducing inequities in vaccine uptake in target demographic and socioeconomic populations. Efforts to encourage vaccination acceptance and adherence have helped reduce hesitancy and associated disparities during the pandemic. Joint efforts are needed among policymakers, healthcare providers, and the public to proactively establish programs to promote vaccine acceptance for other vaccine-preventable diseases, including PCV13 in infants.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study and the journal’s Rapid Service Fee were funded by Pfizer Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Author Contributions

LH and JP were involved in conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis and investigation, writing (reviewing and editing), resources, and supervision of this manuscript. JLN was involved in conceptualization, methodology, writing (reviewing and editing), resources, and supervision of this manuscript. TA was involved in methodology, formal analysis and investigation, and writing (reviewing and editing). AC and AA were involved in conceptualization, writing (reviewing and editing), resources, and supervision of this manuscript.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Editorial/medical writing support was provided by Allison Gillies, PhD, and Anna Stern, PhD, of ICON (Blue Bell, PA) and was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Disclosures

Liping Huang, Jennifer L. Nguyen, Tamuno Alfred, Johnna Perdrizet, Alejandro Cane, and Adriano Arguedas are employees of Pfizer Inc and may hold stock or stock options.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Because all patient-level data in this database were de-identified, use for health services research was fully compliant with US federal law and, accordingly, institutional review board/ethical approval was not needed. The study was conducted in accordance with legal and regulatory requirements, as well as with scientific purpose, value and rigor and followed generally accepted research practices described in Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices issued by the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology and Good Practices for Outcomes Research issued by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research.

Data Availability

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

References

- 1.Wahl B, O'Brien KL, Greenbaum A, et al. Burden of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type B disease in children in the era of conjugate vaccines: global, regional, and national estimates for 2000–15. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(7):e744–e757. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30247-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Preventing pneumococcal disease among infants and young children. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2000;49(RR-9):1–35. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11055835. [PubMed]

- 3.Gierke R, Wodi AP, Kobayashi M. Pneumococcal disease. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/pneumo.html. Accessed Sep 12, 2021.

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Direct and indirect effects of routine vaccination of children with 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease–United States, 1998–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(36):893–7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=16163262. [PubMed]

- 5.Nuorti JP, Whitney CG. Prevention of pneumococcal disease among infants and children—use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-11):1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended child and adolescent immunization schedule for ages 18 years or younger. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/downloads/child/0-18yrs-child-combined-schedule.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2022.

- 7.Wiese AD, Griffin MR, Grijalva CG. Impact of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines on hospitalizations for pneumonia in the United States. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2019;18(4):327–341. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2019.1582337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pneumococcal disease surveillance and reporting. https://www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/surveillance.html. Accessed Feb 10, 2022.

- 9.Simonsen L, Taylor RJ, Schuck-Paim C, Lustig R, Haber M, Klugman KP. Effect of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on admissions to hospital 2 years after its introduction in the USA: a time series analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(5):387–394. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suaya JA, Gessner BD, Fung S, et al. Acute otitis media, antimicrobial prescriptions, and medical expenses among children in the United States during 2011–2016. Vaccine. 2018;36(49):7479–7486. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Active bacterial core surveillance report. Emerging Infections Program Network, Streptococcus pneumoniae, 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/abcs/reports-findings/survreports/spneu18.html. Accessed May 3, 2021.

- 12.Matanock A, Lee G, Gierke R, Kobayashi M, Leidner A, Pilishvili T. Use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine among adults aged ≥65 years: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(46):1069–1075. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6846a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Active bacterial core surveillance report. Emerging Infections Program Network, Streptococcus pneumoniae, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/abcs/downloads/SPN_Surveillance_Report_2019.pdf. Accessed Jul 18, 2022.

- 14.Deloria Knoll M, Park DE, Johnson TS, et al. Systematic review of the effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine dosing schedules on immunogenicity. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33 Suppl 2:S119–29. 10.1097/inf.0000000000000079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Jayasinghe S, Chiu C, Quinn H, Menzies R, Gilmour R, McIntyre P. Effectiveness of 7- and 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines in a schedule without a booster dose: a 10-year observational study. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(3):367–374. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farrar JL, Nsofor C, Childs L, Koboyashi M, Pilishvili T. Systematic review of 13-valent penumococcal conjugate vaccine effectiveness against vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease among children. International Symposium on Pneumococci and Pneumococcal Diseases. Toronto, Canada; 2022.

- 17.Perdrizet J, Pustulka I, Forbes C, Horn E, Gessner BD, Hayford K. Systematic literature review of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) effectiveness against invasive pneumococcal disease in children globally. Infectious Disease Week. Washington, D.C.; 2022.

- 18.Hill HA, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, Sterrett N. Vaccination coverage by age 24 months among children born in 2017 and 2018—National Immunization Survey-Child, United States, 2018–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(41):1435–1440. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7041a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy people 2020 immunization and infectious diseases: objectives. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases/objectives. Accessed Dec 1, 2021.

- 20.Santoli JM, Lindley MC, DeSilva MB, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on routine pediatric vaccine ordering and administration—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(19):591–593. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6919e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Public Policy Committee, International Society of Pharmacoepidemiology. Guidelines for good pharmacoepidemiology practice (GPP). Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(1):2–10. 10.1002/pds.3891. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Walton MK, Powers JH, 3rd, Hobart J, et al. Clinical outcome assessments: conceptual foundation-report of the ISPOR clinical outcomes assessment—emerging good practices for outcomes research task force. Value Health. 2015;18(6):741–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saxena S, Skirrow H, Bedford H. Routine vaccination during COVID-19 pandemic response. BMJ. 2020;369:m2392. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dinleyici EC, Borrow R, Safadi MAP, van Damme P, Munoz FM. Vaccines and routine immunization strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(2):400–407. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1804776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McBride JA, Eickhoff J, Wald ER. Impact of COVID-19 quarantine and school cancelation on other common infectious diseases. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(12):e449–e452. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McNeil JC, Flores AR, Kaplan SL, Hulten KG. The indirect impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on invasive group a Streptococcus, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus infections in Houston area children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40(8):e313–e316. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000003195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Groningen KM, Dao BL, Gounder P. Declines in invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) during the COVID-19 pandemic in Los Angeles county. J Infect. 2022;85(2):174–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2022.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, Weekly Tables of Infectious Disease Data. Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance. https://www.cdc.gov/nndss/data-statistics/index.html.

- 29.McLaughlin JM, Utt EA, Hill NM, Welch VL, Power E, Sylvester GC. A current and historical perspective on disparities in US childhood pneumococcal conjugate vaccine adherence and in rates of invasive pneumococcal disease: considerations for the routinely-recommended, pediatric PCV dosing schedule in the United States. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12(1):206–212. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1069452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill HA, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Singleton JA, Kolasa M. National, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among children aged 19–35 months—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(33):889–896. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6433a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeSilva MB, Haapala J, Vazquez-Benitez G, et al. Association of the COVID-19 pandemic with routine childhood vaccination rates and proportion up to date with vaccinations across 8 US health systems in the vaccine safety datalink. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(1):68–77. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hill HA, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Singleton JA, Kang Y. Vaccination coverage among children aged 19–35 months—United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(40):1123–1128. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6740a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frew PM, Lutz CS. Interventions to increase pediatric vaccine uptake: an overview of recent findings. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(11):2503–2511. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1367069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The Commonwealth Fund. Beyond the case count: the wide-ranging disparities of COVID-19 in the United States. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/sep/beyond-case-count-disparities-covid-19-united-states. Accessed October 15, 2021.

- 35.Tai DBG, Sia IG, Doubeni CA, Wieland M. Disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States: a 2021 update. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-01170-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.