Abstract

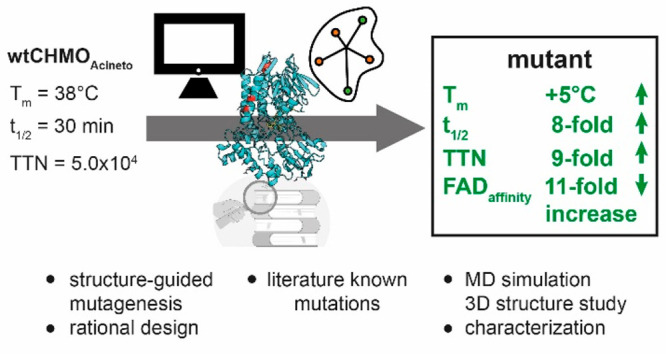

The typically low thermodynamic and kinetic stability of enzymes is a bottleneck for their application in industrial synthesis. Baeyer–Villiger monooxygenases, which oxidize ketones to lactones using aerial oxygen, among other activities, suffer particularly from these instabilities. Previous efforts in protein engineering have increased thermodynamic stability but at the price of decreased activity. Here, we solved this trade-off by introducing mutations in a cyclohexanone monooxygenase from Acinetobacter sp., guided by a combination of rational and structure-guided consensus approaches. We developed variants with improved activity (1.5- to 2.5-fold) and increased thermodynamic (+5 °C Tm) and kinetic stability (8-fold). Our analysis revealed a crucial position in the cofactor binding domain, responsible for an 11-fold increase in affinity to the flavin cofactor, and explained using MD simulations. This gain in affinity was compatible with other mutations. While our study focused on a particular model enzyme, previous studies indicate that these findings are plausibly applicable to other BVMOs, and possibly to other flavin-dependent monooxygenases. These new design principles can inform the development of industrially robust, flavin-dependent biocatalysts for various oxidations.

Keywords: protein engineering, enzyme stabilization, cyclohexanone monooxygenase, structure-guided consensus approach, oxidation, mutagenesis

The need and demand for more sustainable methods of producing bulk and fine chemicals derived from renewable resources have been significant driving forces in biocatalysis. Lately, many industrially relevant processes, including enzymes as catalysts, have been established.1 Proteins often outcompete chemical counterparts by their chemo-, regio-, and enantioselectivity.2 Despite these advantages, they often show reduced stability3 in the presence of organic solvents, high substrate or product concentration, and elevated temperatures. The ability to stabilize proteins means manipulating the physicochemical properties to obtain a thermodynamically stable scaffold.4,5 One hurdle is to improve thermodynamic stability but not to lose its activity or selectivity. Many efforts have been made to tackle this challenge, but there is no one-size-fits-all strategy. Known strategies are directed evolution6,7 and sequence-based phylogenetic analysis to identify thermostable analogous and structure-guided site-directed mutagenesis.8,9 Increased protein stability will result in lower process costs per unit of product and make biocatalytic transformations a real alternative to chemical processes.

A prominent example of the enzyme outperforming conventional chemical catalysis is the Baeyer–Villiger oxidation.10−12 In chemical synthesis, ketones are oxidized to the corresponding esters or lactones by peracids or peroxides. These strong oxidants are often explosive, are sometimes toxic, are needed in stoichiometric amounts, often do not tolerate other functional groups, and are not as stereoselective as enzymes.13,14 A “greener” and a catalytic alternative is the use of Baeyer–Villiger monooxygenases (BVMOs).15 These enzymes require nicotinamide and flavin cofactors (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, NADPH, and flavin adenine dinucleotide, FAD) and aerial oxygen to perform Baeyer–Villiger oxidations. BVMOs are outperforming traditional catalysis due to their excellent chemo-, regio-, and enantioselectivity.16,17 BVMOs are highly valued for their synthetic potential, but their poor stability under process conditions has so far prevented their industrial applications.18 BVMOs often get inactivated within a few minutes at elevated temperatures and in the presence of organic solvents.

A few stable BVMOs are known from the literature: phenylacetone monooxygenase (PAMO), thermostable cyclohexanone monooxygenase (TmCHMO), and polycyclic ketone monooxygenase (PockeMO).19,20 Although their stability is high, they have either poor enantio-/regioselectivity, limited substrate scope (PAMO),21 or low catalytic efficiency (TmCHMO, PockeMO) in contrast to others (e.g., cyclohexanone monooxygenase from Acinetobacter sp. NCIMB 9871, CHMOAcineto).18−20,22−24 Thus, there is an unsolved problem in engineering highly stable and active BVMOs for industrial applications.

We chose CHMOAcineto as the model catalyst for applying our approach to stabilization. CHMOAcineto accepts a wide range of substrates, has high selectivity for Baeyer–Villiger oxidations,25 and is efficient.18,26 Although the catalyzed activity and selectivity of this enzyme would be valuable for industrial applications,16,27−30 its insufficient stability remains uncured.22,31

Several studies have used protein engineering to address this limitation: Schmidt et al. and Van Beek et al. introduced disulfide bridges,32,33 resulting in an improvement of the transition midpoint temperature (ΔT50) of thermal denaturation by 5 and 6 °C, respectively. Opperman et al. substituted amino acids susceptible to oxidation, resulting in an increase in T50 by 7 °C.34 Despite the improved stability, all variants had lower activity than the wild-type (WT) enzyme. Engel et al. indicated that none of these mutants could outperform the wild-type enzyme in the production of ε-caprolactone,35,36 an important polymer building block for the synthesis of polyesters, thermoplastic polyurethanes, acrylic resins, printing inks, plasticizers, and precursor to nylon-6.37,38 Previous thermostability engineering efforts have not yet achieved the desired outcomes of high stability and activity.

We designed our engineering strategy using a combination of (i) a rational-design approach that increases the affinity to the FAD cofactor, (ii) applying a structure-guided consensus approach that compares 31 sequences (motif, FxGxxxHxxxW; x = any canonical amino acid) of BVMOs,8,9 and (iii) including “hot-spots” in the sequence that are known for improving stability and activity of CHMOAcineto.39

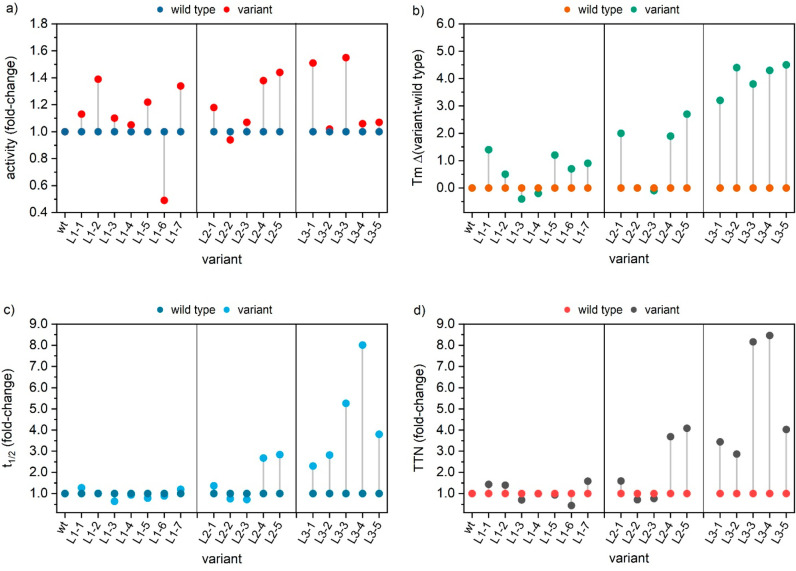

This leads to three generations of mutant libraries (L1–L3, Figure 1). The variants were always fully characterized in their activity, selectivity, and catalytic efficiency, as well as their thermodynamic (Tm) and kinetic stability (t1/2).

Figure 1.

Overview of the individual steps followed in the CHMOAcineto stabilization workflow. Three generations of libraries created with 17 individual variants. Mutations are labeled in red.

First (L1), we addressed the low affinity for the cofactor FAD, which we had determined at Kd = 1–3 μM in an earlier study.26 For catalytic activity, it is required to be noncovalently bound to the apoenzyme via the so-called Rossmann fold, a binding domain located at the N-terminus of the enzyme (Figure S1). We had shown that addition of FAD increased the kinetic stability of the wild-type up to 7-fold and that this effect was synergistic with improvements caused by other additives.26 No previous study, including ours, has investigated the effect of mutations in the Rossman fold on the binding affinity to FAD.

Following up on this finding, we hypothesized that increased affinity to FAD achieved by protein engineering might also contribute positively to enzyme stability. We studied multiple sequences of BVMOs, specifically their Rossmann fold (Figure S2). We found that BVMOs with high stability (e.g., TmCHMO, PAMO) carry an alanine at position 14 (the second position in the Rossmann fold). CHMOAcineto has a glycine at that position. This finding prompted us to choose G14A as the first mutation (L1-1). We measured the thermodynamic and kinetic stability and the activity using differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) and an NADPH-depletion assay, respectively,26 of CHMO-L1-1 (Figure 2, Table S3): activity increased by 13%, thermodynamic stability by 1.4 °C (quantified as Tm), and kinetic stability by 30% over the wild-type.

Figure 2.

Characterization of best variants. (a) Enzyme activity was measured by monitoring the decrease of NADPH absorbance at 340 nm. Standard assays contained the enzyme (0.05 μM), cyclohexanone (0.5 mM), and NADPH (100 μM) in 50 mM TrisHCl pH 8.5. CHMOwt = 16.4 ± 1.1 U mg–1. (b) Thermodynamic stability measured by nanodifferential scanning fluorimetry (nanoDSF): 50 mM TrisHCl, 10 μM FAD, 2 mg mL–1 enzyme. CHMOwt = 38.2 °C. (c) Kinetic stability of 1 μM isolated CHMOAcineto at 30 °C in 50 mM TrisHCl buffer, pH 8.5. CHMOwt = 34.4 ± 4.6 min. (d) Total turnover number (TTN) values were obtained from the exponential fit of catalytic enzyme activity under turnover conditions, CHMOwt = 5.04 × 104.43

The binding affinity of the G14A variant to FAD was ∼8-fold tighter than in the wild-type (Table S4), determined using our statistically reliable deflavination–titration assay reported previously.31 These results supported our hypothesis that position 14 is a critical residue for stability and that stability and activity can be increased simultaneously. High kinetic stability and specific activity (from initial rate measurements) are good predictors for a high total turnover number (“activity”), individually or combined. Our experiments were not designed to distinguish between these cases. Given the large difference between the relative time scales of deactivation (half-life >0.5 h) and of the measurements to determine specific activity (seconds to minutes), it is unlikely that increases in kinetic stability would significantly confound these measurements. With less stable enzymes, that is indeed a problem, as we have reported earlier.31

We decided to explore the potential of position 14 and created mutants with the remaining canonical amino acids except methionine, valine, and serine, which failed in the PCR experiments. All variants except G14A and G14R had low or undetectable activity (Table S5). The thermodynamic stability of the additional variants was also much lower than WT (Table S5, Figure S6). These results are compatible with the evolutionary analysis of BVMOs, where only glycine and alanine are found in position 14 (Figure S2).40−42 The introduction of arginine did not abolish activity completely (30% of CHMOAcineto) while creating a thermodynamically stable variant (+0.3 °C over CHMOwt). By inference from the poor or undetectable activity, it is likely that mutations at G14 other than A or W strongly decrease the affinity to FAD, but we cannot exclude other reasons for the lack of activity based on our data.

Next, we envisioned further stabilization by a structure-guided consensus approach, a data-driven method that utilizes structural information and the function of the desired enzyme. It operates on the assumption that the prevalence of amino acids (per position in the sequence) correlates positively with the stability of the protein; a consensus residue will be more stable than the nonconserved amino acids. This method is usually applied to a small family of sequences with low homology, such as BVMOs (Figure 1). All mutations are listed in Table S2.

For the creation of the consensus variants, only positions more than 6 Å away from the active site were allowed in the design (based on a homology model, Figure S3) to not directly interfere with the enzyme activity or affinity for the substrates. Seven mutants were selected and created by these principles, which included the previously tested variant L1-1 (G14A). We found the greatest improvements in activity with substitution N336E (40% higher activity than CHMOwt). The highest thermodynamic stability came from the previously characterized G14A (Tm + 1.4 °C over WT) and L1-7 (+0.9 °C). Kinetic stability of the latter two increased by 30% and 20% over WT. See Figure 2 and Table S3 for details.

We designed the second-generation library of mutants by combining the best variants from the first generation (Table S2), which led to a further improvement in stability (up to 3 °C higher Tm and 3-fold the half-life of the WT) and activity (40% increase over WT; Figure 2). Mutations shared among the successful combinations included G14A, N336E, Q451K, T453A, V454E, Q473R, and N477E.

We created a third library consisting of five variants that combined the best mutations of the second generation with three literature-known mutations that increase stability (Table S2): (i) a pair of mutations (T415C/A463C) that were shown to have a beneficial effect on kinetic stability (3-fold half-life);28 and (ii) a replacement of oxygen-sensitive methionine by isoleucine (M400I), which had been designed to reduce the rate of unfolding.34

In general, all variants of the third generation were more stable (thermodynamically and kinetically) and equally or more active than the wild-type (Table S3)

The best candidates from L3 were 51–55% more active and had +4 °C higher thermodynamic stability than CHMOwt; their half-life was 5–8-fold that of the WT. These improvements were the highest in this study and are outstanding in the field of BVMOs. To quantify the combined effect of improvements in stability and activity, we estimated the total turnover number of the new mutants (Figure 2, Table S3), which were up to 8-fold the value of the WT.

We tested if the mutations had changed the enantioselectivity or substrate scope using a selection of six variants from libraries L2 and L3 and five substituted cyclohexanone and cyclobutanones (Figure S7, Table S6). No significant differences of the variants to the WT were found. The substrate screening was performed by whole-cell biocatalysis in the presence of the desired ketone. Conversions were analyzed via GC measurements to rule out activities based on uncoupling reactions.44 We also determined the Michaelis–Menten parameters for two variants [L1-1 (G14A, improved FAD binding)] and L3-4 best variant in stability (G14A, N336E, M400I, Q451K, Y452Y, T453A, V454E, Q473R, and N477E), showing an increased affinity for the substrate and a higher turnover rate in the mutants (Table 1, Table S4).

Table 1. Characterization of Michaelis–Menten Kinetics of Top Variants.

| variant | Kma (μM) | kcata (s–1) | kcat/Km (mM–1 s–1) | Kdb (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHMOAcineto | 6.7 ± 2.0 | 15.0 ± 1.3 | 2200 | 1.60 ± 0.06 |

| L1-1 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 24.2 ± 1.4 | 7058 | 0.19 ± 0.07 |

| L3-4 | 5.0 ± 1.5 | 16.3 ± 1.8 | 3187 | 0.14 ± 0.02 |

Catalytic rates were obtained via incubation of the isolated enzyme with varying amounts of substrate, and kinetic parameters (Km, kcat) were determined by fitting to the Michaelis–Menten equation.

The Kd value was determined by fitting the data of catalytic activity of the holoenzyme versus concentration of FAD.

To confirm whether our hypothesis for library L1 (tight binding of FAD increases stability) would still hold true in L3, we chose to measure the binding affinity of FAD for the two mutants characterized above, using our statistically reliable assay.31 We found that binding to the cofactor was tighter than in the WT by approximately 1 order of magnitude in both variants (Table 1, Table S4), supporting the hypothesis, and not significantly different between the two. While we cannot determine whether G14A is the only mutation that causes an increase in affinity, we can conclude that the effect of G14A is not significantly perturbed by the combination of the other seven mutations in L3-4 (N336E, M400I, Q451K, T453A, V454E, Q473R, and N477E). Whether that is the result of insignificant participation or mutual canceling (to a mean value that is insignificantly different from G14A) was not a goal of our experimental design.

We used molecular dynamics to elucidate what structural changes caused by the mutations in most stable variants were responsible for the higher affinity to FAD. Simulations (50 ns, 5 replicate calculations; Figure 3) were performed on a homology model of CHMOwt, including the following variants: L1-1 (G14A), G14R (the other active variant from the G14 library), and G14T (an inactive variant from that library).

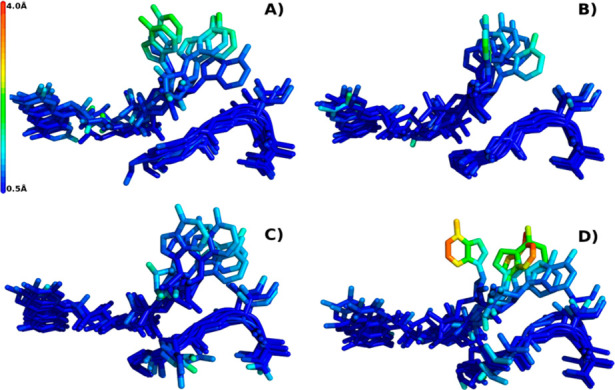

Figure 3.

3D representation of the average position of the mutated loop (bottom) and the FAD cofactor (top) for the (A) CHMOwt, (B) G14A mutant, (C) G14R mutant, and (D) G14T mutant. The root-mean-square fluctuations are represented in a color gradient: blue (small fluctuations), red (higher fluctuations). Each of the panels shows a superposition of the five MD simulations.

The simulations predicted no significant differences in the backbone or orientations of side chains on the mutated region in any of the variants. The predicted fluctuations for the mutated region were small (∼0.6 Å) and not significantly different between variants, suggesting that it is static.

For the WT and the variant G14T, the simulations positioned the adenosine of FAD detached from its original position and predicted significantly larger fluctuations than for the variants G14A and G14R (Figure 3). This result indicates that the holoenzyme G14A-FAD and G14R-FAD are more rigid than the WT or G14T.

Our structural analysis suggests that the side chain of residue 14 is in close proximity to the FAD cofactor but pointing away from it. We conclude that there is no direct interaction between the side chain and FAD and speculate that the observed stabilization might be achieved by a more complex interaction with the adjacent amino acids. This explanation is compatible with our finding that two drastically different amino acids (alanine and arginine) both lead to an increase in enzymatic activity.

We increased the thermodynamic- (+5 °C Tm), and kinetic stability (8-fold half-life), and the activity (1.5–2.5-fold) of CHMOAcineto by introducing mutations designed with a combination of a rational and structure-guided consensus principles. The changes to the structure had no measurable effect on substrate scope or regio- and enantioselectivity. A single mutation introduced by our design increased the affinity toward the cofactor FAD by ∼11-fold—an increase that was compatible with other mutations introduced later. Previous studies, by ourselves and by others, did not evaluate the influence of mutations on the affinity to the flavin cofactor. Our results show that the model BVMO cyclohexanone monooxygenase from Acinetobacter can be stabilized while preserving its catalytic activity and substrate promiscuity. Based on general knowledge in the field, it is plausible that similar improvements could be achieved by this design with closely related BVMOs, and potentially also with other flavin-dependent oxygenases. Many industrially relevant oxidations are catalyzed by these and other enzymes and would benefit from new principles to develop catalysts with high operational stability.

Acknowledgments

Financial support by TU Wien (M.D.M., J.J., F.R.), ABC-Top Anschubfinanzierung, Austrian agency for international cooperation in education and research (OeaD), and WWTF Project LS17-069 (H.R.M.) is gratefully acknowledged. M.J.F. acknowledges funding by OxyGreen (FP7 EU Grant 212281). Doctoral program Biomolecular Technology of Proteins (BioToP) funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), grant number W1224. L.C.P.G. was funded by Austrian Science Fund (FWF M1948-N28). D.V.R. was funded by the Austrian Science Fund FWF (Project P-18945). At present, D.V.R. is a staff member of CONICET and UNR, Argentina, and thanks CONICET, UNR, and Agencia I+D+i, Argentina.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.2c03225.

Additional experimental data as well as detailed experimental procedures (PDF)

Author Contributions

F.R. and M.D.M. led the project, conceived the research, and designed the experiments. D.V.R. shaped the initial research design, constructed the wild-type and some mutant plasmids, and set up preliminary studies. S.F. and H.R.M. performed the mutation studies, the stability measurements, and the enzyme kinetics. L.C.P.G. established the activity and stability studies. J.J. performed the site saturation mutagenesis study. O.G.C. ran the MD simulations, and A.S.B. worked on the structure-guided consensus approach. M.J.F. established the statistical basis for activity and stability assays. R.L., A.S.B., and O.G.C. advised on all aspects of the research. H.R.M., J.J., F.R., C.O., and M.J.F. cowrote the manuscript and designed figures. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Open Access is funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Wu S. K.; Snajdrova R.; Moore J. C.; Baldenius K.; Bornscheuer U. T. Biocatalysis: Enzymatic Synthesis for Industrial Applications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (1), 88–119. 10.1002/anie.202006648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hönig M.; Sondermann P.; Turner N. J.; Carreira E. M. Enantioselective Chemo- and Biocatalysis: Partners in Retrosynthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56 (31), 8942–8973. 10.1002/anie.201612462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modarres H. P.; Mofrad M. R.; Sanati-Nezhad A. Protein Thermostability Engineering. RSC Adv. 2016, 6 (116), 115252–115270. 10.1039/C6RA16992A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler P. G.; Broendum S. S.; Riley B. T.; Spence M. A.; Jackson C. J.; McGowan S.; Buckle A. M. Strategies for Increasing Protein Stability. Protein Nanotechnology; Methods Mol. Biol. (N. Y., NY, U. S.) 2020, 2073, 163–181. 10.1007/978-1-4939-9869-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommarius A. S.; Paye M. F. Stabilizing Biocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42 (15), 6534–6565. 10.1039/c3cs60137d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom J. D.; Meyer M. M.; Meinhold P.; Otey C. R.; MacMillan D.; Arnold F. H. Evolving Strategies for Enzyme Engineering. Curr. Opin. Struc. Biol. 2005, 15 (4), 447–452. 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victorino da Silva Amatto I.; Gonsales da Rosa-Garzon N.; Antônio de Oliveira Simões F.; Santiago F.; Pereira da Silva Leite N.; Raspante Martins J.; Cabral H. Enzyme Engineering and Its Industrial Applications. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2022, 69 (2), 389–409. 10.1002/bab.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dror A.; Shemesh E.; Dayan N.; Fishman A. Protein Engineering by Random Mutagenesis and Structure-Guided Consensus of Geobacillus Stearothermophilus Lipase T6 for Enhanced Stability in Methanol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80 (4), 1515–1527. 10.1128/AEM.03371-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Figueroa E.; Chaparro-Riggers J.; Bommarius A. S. Development of a Thermostable Glucose Dehydrogenase by a Structure-Guided Consensus Concept. ChemBioChem. 2007, 8 (18), 2295–2301. 10.1002/cbic.200700500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bong Y. K.; Song S.; Nazor J.; Vogel M.; Widegren M.; Smith D.; Collier S. J.; Wilson R.; Palanivel S. M.; Narayanaswamy K.; Mijts B.; Clay M. D.; Fong R.; Colbeck J.; Appaswami A.; Muley S.; Zhu J.; Zhang X.; Liang J.; Entwistle D. Baeyer–Villiger Monooxygenase-Mediated Synthesis of Esomeprazole as an Alternative for Kagan Sulfoxidation. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83 (14), 7453–7458. 10.1021/acs.joc.8b00468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milker S.; Fink M. J.; Rudroff F.; Mihovilovic M. D. Non-Hazardous Biocatalytic Oxidation in Nylon-9 Monomer Synthesis on a 40 G Scale with Efficient Downstream Processing. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 114 (8), 1670–1678. 10.1002/bit.26312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fürst M. J. L. J.; Gran-Scheuch A.; Aalbers F. S.; Fraaije M. W. Baeyer-Villiger Monooxygenases: Tunable Oxidative Biocatalysts. ACS Catal. 2019, 9 (12), 11207–11241. 10.1021/acscatal.9b03396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert H.; Kuznetsov A.. Detection and Disposal of Improvised Explosives, 1st ed.; Springer, 2006; p 230. [Google Scholar]

- Kamerbeek N. M.; Janssen D. B.; van Berkel W. J. H.; Fraaije M. W. Baeyer-Villiger Monooxygenases, an Emerging Family of Flavindependent Biocatalysts. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2003, 345, 667–678. 10.1002/adsc.200303014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S.; Bornscheuer U. T. Baeyer-Villiger Monooxygenases: From Protein Engineering to Biocatalytic Applications. Enzymes 2020, 47, 231–281. 10.1016/bs.enz.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leisch H.; Morley K.; Lau P. C. K. Baeyer-Villiger Monooxygenases: More Than Just Green Chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 111, 4165–4222. 10.1021/cr1003437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balke K.; Marcus B.; Bornscheuer U. T. Controlling the Regioselectivity of Baeyer – Villiger Monooxygenases by Mutation of Active-Site Residues. ChemBioChem. 2017, 18, 1627–1638. 10.1002/cbic.201700223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fürst M. J. L. J.; Boonstra M.; Bandstra S.; Fraaije M. W. Stabilization of Cyclohexanone Monooxygenase by Computational and Experimental Library Design. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2019, 116 (9), 2167–2177. 10.1002/bit.27022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero E.; Rub J. Ø.; Mattevi A.; Fraaije M. W. Characterization and Crystal Structure of a Robust Cyclohexanone Monooxygenase. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 15852–15855. 10.1002/anie.201608951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fürst M. J. L. J.; Savino S.; Dudek H. M.; Gomez Castellanos J. R.; Gutierrez de Souza C.; Rovida S.; Fraaije M. W.; Mattevi A. Polycyclic Ketone Monooxygenase from the Thermophilic Fungus Thermothelomyces Thermophila: A Structurally Distinct Biocatalyst for Bulky Substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (2), 627–630. 10.1021/jacs.6b12246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraaije M. W.; Wu J.; Heuts D. P. H. M.; van Hellemond E. W.; Spelberg J. H. L.; Janssen D. B. Discovery of a Thermostable Baeyer-Villiger Monooxygenase by Genome Mining. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 66 (4), 393–400. 10.1007/s00253-004-1749-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansouri H. R.; Mihovilovic M. D.; Rudroff F. Investigation of a Novel Type I Baeyer-Villiger Monooxygenase from Amycolatopsis Thermoflava Revealed High Thermodynamic- but Limited Kinetic Stability. ChemBioChem. 2020, 21 (7), 971–977. 10.1002/cbic.201900501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. C. J.; Peoples O. P.; Walsh C. T. Acinetobacter Cyclohexanone Monooxygenase - Gene Cloning and Sequence Determination. J. Bacteriol. 1988, 170 (2), 781–789. 10.1128/jb.170.2.781-789.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue N. A.; Peter D. B. N.; Trudgill W. The Purification and Properties of Cyclohexanone Oxygenase from Nocardia Globerula Cl1 and Acinetobacter Ncib 9871. Eur. J. Biochem. 1976, 63 (1), 175–192. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink M. J.; Rial D. V.; Kapitanova P.; Lengar A.; Rehdorf J.; Cheng Q.; Rudroff F.; Mihovilovic M. D. Quantitative Comparison of Chiral Catalysts Selectivity and Performance: A Generic Concept Illustrated with Cyclododecanone Monooxygenase as Baeyer-Villiger Biocatalyst. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354 (18), 3491–3500. 10.1002/adsc.201200453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abril O.; Ryerson C. C.; Walsh C.; Whitesides G. M. Enzymatic Baeyer-Villiger Type Oxidations of Ketones Catalyzed by Cyclohexanone Oxygenase. Bioorg. Chem. 1989, 17 (1), 41–52. 10.1016/0045-2068(89)90006-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beneventi E.; Ottolina G.; Carrea G.; Panzeri W.; Fronza G.; Lau P. C. K. Enzymatic Baeyer–Villiger Oxidation of Steroids with Cyclopentadecanone Monooxygenase. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzymatic 2009, 58 (1), 164–168. 10.1016/j.molcatb.2008.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudroff F.; Rydz J.; Ogink F. H.; Fink M.; Mihovilovic M. D. Comparing the Stereoselective Biooxidation of Cyclobutanones by Recombinant Strains Expressing Bacterial Baeyer–Villiger Monooxygenases. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2007, 349 (8–9), 1436–1444. 10.1002/adsc.200700072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fink M. J.; Rudroff F.; Mihovilovic M. D. Baeyer–Villiger Monooxygenases in Aroma Compound Synthesis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21 (20), 6135–6138. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink M. J.; Mihovilovic M. D. Non-Hazardous Baeyer–Villiger Oxidation of Levulinic Acid Derivatives: Alternative Renewable Access to 3-Hydroxypropionates. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51 (14), 2874–2877. 10.1039/C4CC08734H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves L. C. P.; Kracher D.; Milker S.; Mihovilovic M. D.; Fink M. J.; Rudroff F.; Ludwig R.; Bommarius A. S. Mutagenesis-Independent Stabilization of Class B Flavin Monooxygenases in Operation. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 2121–2131. 10.1002/adsc.201700585. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S.; Genz M.; Balke K.; Bornscheuer U. T. The Effect of Disulfide Bond Introduction and Related Cys/Ser Mutations on the Stability of a Cyclohexanone Monooxygenase. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 214, 199–211. 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beek H. L.; Wijma H. J.; Fromont L.; Janssen D. B.; Fraaije M. W. Stabilization of Cyclohexanone Monooxygenase by a Computationally Designed Disulfide Bond Spanning Only One Residue. FEBS Open Bio 2014, 4, 168–174. 10.1016/j.fob.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opperman D. J.; Reetz M. T. Towards Practical Baeyer-Villiger-Monooxygenases: Design of Cyclohexanone Monooxygenase Mutants with Enhanced Oxidative Stability. ChemBioChem. 2010, 11 (18), 2589–96. 10.1002/cbic.201000464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel J.; Mthethwa K. S.; Opperman D. J.; Kara S. Characterization of New Baeyer-Villiger Monooxygenases for Lactonizations in Redox-Neutral Cascades. Mol. Catal. 2019, 468, 44–51. 10.1016/j.mcat.2019.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T.-H.; Kang S.-H.; Han J.-E.; Seo E.-J.; Jeon E.-Y.; Choi G.-E.; Park J.-B.; Oh D.-K. Multilayer Engineering of Enzyme Cascade Catalysis for One-Pot Preparation of Nylon Monomers from Renewable Fatty Acids. ACS Catal. 2020, 10 (9), 4871–4878. 10.1021/acscatal.9b05426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence S. A.Amines: Synthesis, Properties and Applications; Cambridge University Press, 2004; pp 119–167. [Google Scholar]

- Beerthuis R.; Rothenberg G.; Shiju N. R. Catalytic Routes Towards Acrylic Acid, Adipic Acid and ε-Caprolactam Starting from Biorenewables. Green Chem. 2015, 17 (3), 1341–1361. 10.1039/C4GC02076F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balke K.; Beier A.; Bornscheuer U. T. Hot Spots for the Protein Engineering of Baeyer-Villiger Monooxygenases. Biotechnol Adv. 2018, 36 (1), 247–263. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dym O.; Eisenberg D. Sequence-Structure Analysis of Fad-Containing Proteins. Protein Sci. 2001, 10 (9), 1712–1728. 10.1110/ps.12801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanukoglu I. Conservation of the Enzyme-Coenzyme Interfaces in Fad and Nadp Binding Adrenodoxin Reductase-a Ubiquitous Enzyme. J. Mol. Evol. 2017, 85 (5–6), 205–218. 10.1007/s00239-017-9821-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojha S.; Meng E. C.; Babbitt P. C. Evolution of Function in the ″Two Dinucleotide Binding Domains″ Flavoproteins. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2007, 3 (7), e121–e121. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers T. A.; Bommarius A. S. Utilizing Simple Biochemical Measurements to Predict Lifetime Output of Biocatalysts in Continuous Isothermal Processes. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2010, 65 (6), 2118–2124. 10.1016/j.ces.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier A.; Bordewick S.; Genz M.; Schmidt S.; van den Bergh T.; Peters C.; Joosten H. J.; Bornscheuer U. T. Switch in Cofactor Specificity of a Baeyer-Villiger Monooxygenase. ChemBioChem. 2016, 17 (24), 2312–2315. 10.1002/cbic.201600484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.