Abstract

Bacillus subtilis grows under anaerobic conditions utilizing nitrate ammonification and various fermentative processes. The two-component regulatory system ResDE and the redox regulator Fnr are the currently known parts of the regulatory system for anaerobic adaptation. Mutation of the open reading frame ywiD located upstream of the respiratory nitrate reductase operon narGHJI resulted in elimination of the contribution of nitrite dissimilation to anaerobic nitrate respiratory growth. Significantly reduced nitrite reductase (NasDE) activity was detected, while respiratory nitrate reductase activity was unchanged. Anaerobic induction of nasDE expression was found to be significantly dependent on intact ywiD, while anaerobic narGHJI expression was ywiD independent. Anaerobic transcription of hmp, encoding a flavohemoglobin-like protein, and of the fermentative operons lctEP and alsSD, responsible for lactate and acetoin formation, was partially dependent on ywiD. Expression of pta, encoding phosphotransacetylase involved in fermentative acetate formation, was not influenced by ywiD. Transcription of the ywiD gene was anaerobically induced by the redox regulator Fnr via the conserved Fnr-box (TGTGA-6N-TCACT) centered 40.5 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site. Anaerobic induction of ywiD by resDE was found to be indirect via resDE-dependent activation of fnr. The ywiD gene is subject to autorepression and nitrite repression. These results suggest a ResDE → Fnr → YwiD regulatory cascade for the modulation of genes involved in the anaerobic metabolism of B. subtilis. Therefore, ywiD was renamed arfM for anaerobic respiration and fermentation modulator.

Under anaerobic growth conditions, Bacillus subtilis can generate ATP via nitrate ammonification or fermentation (2, 5, 14). During nitrate respiration, nitrate is reduced by the respiratory nitrate reductase (NarGHI) to nitrite (2, 5, 9). Nitrite is further reduced to ammonia by a general nitrite reductase (NasDE) (4, 13). The latter enzyme also contributes to the nitrite assimilation process (13). During anaerobic fermentation, carbon sources are transformed via pyruvate into the end products lactate, acetoin, 2,3-butanediol, ethanol, acetate, and succinate (3, 12). NAD+ regeneration is primarily mediated by a cytoplasmic lactate dehydrogenase, encoded by lctE, that converts pyruvate to lactate (3). Acetoin is synthesized from pyruvate in a two-step reaction catalyzed by acetolactate synthase and acetolactate decarboxylase, encoded by the alsSD operon (3, 20). Subsequently, acetoin is converted to 2,3-butanediol by acetoin reductase (12). The third major fermentation product, acetate, is formed from acetyl-coenzyme A in a two-step reaction catalyzed by phosphotransacetylase and acetate kinase, encoded by pta and ack, respectively. The latter step usually leads to the formation of ATP.

Due to the drastically different ATP yields of respiratory and fermentative processes, bacteria usually use a fine-tuned regulatory system to maintain the most efficient mode of ATP generation. In B. subtilis only parts of the anaerobic redox regulatory system are known. The pleiotropic two-component regulating system ResDE, encoded by the resABCDE operon, is activated by an unknown redox-sensing system (21). Activated ResD binds directly to DNA elements (TTTGTGAAT) located within anaerobically induced promoter regions. Activator binding at this conserved promoter element and transcriptional activation were demonstrated for nasDE, the flavohemoglobin gene hmp, and the redox regulatory gene fnr (14, 16, 21). The redox regulator Fnr, possibly containing an iron sulfur cluster similar to its Escherichia coli counterpart, is subsequently responsible for the induction of the narGHJI operon and narK, encoding respiratory nitrate reductase and a potential nitrite extrusion protein, respectively (2).

All known Fnr-regulated genes have a highly conserved potential B. subtilis Fnr-binding site (TGTGA-N6-TCACA) in their promoter regions. Additional potential Fnr-binding sites were found in the 5′ regions of a second potential nitrate/nitrite transporter gene, ywcJ, the fermentation operons lctEP and alsSD, and ywiD, encoding a protein of unknown function (2, 3).

The regulation of genes involved in fermentation was described recently (3). Transcription of alsSD and lctEP is induced anaerobically and repressed by the presence of nitrate (3). However, Fnr is only partially responsible for anaerobic lctEP and alsSD induction. These findings, in combination with the incompletely understood molecular basis for anaerobic nasDE and hmp induction, raise the possibility of additional redox regulatory components in B. subtilis. Here we provide evidence that ywiD, located in the 5′ region of the narGHJI operon, is an important part of the anaerobic regulatory system, responsible for the modulation of anaerobic gene expression. Since ywiD expression is Fnr dependent, a regulatory cascade from an unknown sensor proceeding via resDE through fnr and ywiD to multiple target genes is proposed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

All B. subtilis strains used are listed in Table 1. For the investigation of the expression of the various lacZ fusions, the host strains were grown anaerobically at 37°C on Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with 20 mM K3PO4 (pH 7), 2 mM (NH4)2SO4, 1 mM glutamic acid, 1 mM l-tryptophan, 0.8 mM l-phenylalanine, 0.005% (wt/vol) ammonium iron(III) citrate, 1 mM glucose, and, when indicated, 10 mM nitrite or nitrate (4, 13).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| B. subtilis strain | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| 168 | trpC2 | BGSCa |

| BSIP1104 | trpC2 pheA1pta-lacZ cat | 18 |

| BSIP1204 | trpC2 arfM-lacZ cat | This study |

| BSIP1185 | trpC2 lctE-lacZ cat | 3 |

| BSIP1192 | trpC2 alsS-lacZ cat | 3 |

| JH642 | trpC2 pheA1 | BGSC |

| LAB2000 | trpC2 pheA1 SPβc2del2::Tn917::pML26 (hmp-lacZ) cat | This study |

| LAB2143 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::narG-lacZ cat | 13 |

| LAB2313 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet fnr::pMMN297 (Pspac-fnr) | This study |

| LAB2854 | trpC2 pheA1 SPβc2del2::Tn917::pMMN392 (nasD-lacZ) cat | 13 |

| MH5081 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet | This study |

| MMB2 | trpC2 pheA1 fnr::spc arfM-lacZ cat | This study |

| MMB4 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet arfM-lacZ cat | This study |

| MMB8 | trpC2 pheA1 SPβc2del2::Tn917::pML26 (hmp-lacZ) cat arfM::kan | This study |

| MMB9 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan amyE::narG-lacZ cat | This study |

| MMB10 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan nasD-lacZ cat | This study |

| MMB14 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan alsS-lacZ cat | This study |

| MMB15 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan lctE-lacZ cat | This study |

| MMB20 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet cat fnr::pMMN297 (Pspac-fnr) arfM-lacZ cat | This study |

| MMB21 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan arfM-lacZ cat | This study |

| MMB25 | trpC2 pheA1 arfMΔFnr-lacZ cat | This study |

| MMB38 | trpC2 pheA1pta-lacZ cat arfM::kan | This study |

| MMB40 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan fnr::spc | This study |

| MMB41 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan ΔresDE::tet | This study |

| MMB46 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan fnr::spc lctE-lacZ cat | This study |

| MMB47 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan ΔresDE::tet lctE-lacZ cat | This study |

| MMB48 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan fnr::spc SPβc2del2::Tn917::pMMN392 (nasD-lacZ) cat | This study |

| MMB49 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan fnr::spc SPβc2del2::Tn917::pML26(hmp-lacZ) cat | This study |

| MMB50 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan ΔresDE::tet alsS-lacZ cat | This study |

| MMB51 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan fnr::spc amyE::narG-lacZ cat | This study |

| MMB52 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan fnr::spc arfM-lacZ cat | This study |

| MMB54 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan ΔresDE::tet arfM-lacZ cat | This study |

| MMB55 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan ΔresDE::tet amyE::narG-lacZ cat | This study |

| MMB56 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan ΔresDE::tet SPβc2del2::Tn917::pMMN392(nasD-lacZ) cat | This study |

| MMB57 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan ΔresDE::tet SPβc2del2::Tn917::pML26(hmp-lacZ) cat | This study |

| MMB67 | trpC2 pheA1 lctE-lacZ cat fnr::spc | This study |

| MMB68 | trpC2 pheA1 alsS-lacZ cat fnr::spc | This study |

| MMB70 | trpC2 pheA1 fnr::spc SPβc2del2::Tn917::pMMN392(nasD-lacZ) cat | This study |

| MMB71 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::narG-lacZ cat fnr::spc | This study |

| MMB72 | trpC2 pheA1 fnr::spc SPβc2del2::Tn917::pML26(hmp-lacZ) cat | This study |

| MMB74 | trpC2 pheA1 lctE-lacZ cat ΔresDE::tet | This study |

| MMB75 | trpC2 pheA1 alsS-lacZ cat ΔresDE::tet | This study |

| MMB77 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet SPβc2del2::Tn917::pMMN392(nasD-lacZ) cat | This study |

| MMB78 | trpC2 pheA1 amyE::narG-lacZ cat ΔresDE::tet | This study |

| MMB79 | trpC2 pheA1 ΔresDE::tet SPβc2del2::Tn917::pML26(hmp-lacZ) cat | This study |

| MMB103 | trpC2 pheA1 ywiC::spc | This study |

| MMB104 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM::kan | This study |

| THB2 | trpC2 pheA1 fnr::spc | This study |

| THB216 | trpC2 pheA1 arfM-lacZ cat | This study |

BGSC, Bacillus Genetic Stock Center.

Inoculation of the test culture was performed under the described conditions and started in all experiments with identical amounts of cultured cells. For all strains tested, β-galactosidase activities were followed over the whole growth phase. Values obtained from comparable growth phases are listed. For β-galactosidase assays, cells were harvested at an appropriate optical density at 578 nm (OD578) by centrifugation. The cell pellet was resuspended in 400 μl of Z-buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4 · 2H2O, 40 mM NaH2PO4 · H2O, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4 · 7H2O, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.0). Lysozyme-DNase solution (2 μl; 8 mg of lysozyme in 950 μl of sterile water and 50 μl of DNase [2.5 mg/ml in 3 M sodium acetate]) was added and incubated for 15 min at 37°C. The crude cell extract was centrifuged for 5 min to remove cell debris. The supernatant was recovered. Protein concentration of the cell extract was determined using the Roti-Quant (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) protein detection assay. Then 600 μl of Z-buffer was added to 200 μl of crude cell extract.

The reaction was started by adding 200 μl of ortho-nitrophenylgalactopyranoside stock solution (4 mg/ml). To stop the reaction, 500 μl of 1 M Na2CO3 was added, the reaction time was noted, and the OD420 was determined versus the reference reaction. The specific activity was determined using the following equation: units per milligram of protein = 1,500/[test volume (milliliters) × time (minutes) × protein concentration (milligrams per milliliter)] × OD420.

For the growth experiments, minimal medium containing 80 mM K2HPO4, 44 mM KH2PO4, 0.8 mM MgSO4 · 7H2O, 1.5 mM thiamine, 40 μM CaCl2 · 2H2O, 68 μM FeCl2 · 4H2O, 5 μM MnCl2 · 4H2O, 12.5 μM ZnCl2, 24 μM CuCl2 · 2H2O, 2.5 μM CoCl2 · 6H2O, 2.5 μM Na2MoO4 · 2H2O, 50 mM glucose, and, where indicated, 10 mM nitrate or 10 mM nitrite was used. Antibiotics were added when necessary at the following concentrations (milligrams per liter): ampicillin, 100; chloramphenicol, 5; kanamycin, 10; and spectinomycin, 60. Bacteria were grown at 37°C in all experiments.

DNA manipulations and genetic techniques.

E. coli was transformed as described by Chung and Miller (1). B. subtilis cells were transformed as described before (7). Transcriptional fusions with the E. coli lacZ gene were constructed using integrative plasmid pJM783 (16). A pUC18 derivative was obtained during the pDIA5348 shotgun cloning experiment described before (2), encompassing the complete intergenic region between the ywiC and ywiD genes.

To construct a transcriptional fusion with the ywiD gene, the chromosomal insert from the pUC18 derivative was excised as a ∼0.34-kb HaeIII-BclI fragment and inserted between the SmaI and BamHI sites in pJM783, leading to plasmid pDIA5562. The lacZ gene in this construct was placed after the 38th codon of the ywiD gene. Both transcriptional fusions were introduced into the B. subtilis 168 chromosome by Campbell-type recombination events to generate B. subtilis BSIP1203 and BSIP1204, respectively. The ywiD-lacZ fusion was transferred from BSIP1204 into the B. subtilis JH642-based fnr mutant THB2, the resDE mutant MH5081, the resDE mutant LAB2313 carrying fnr under the control of the IPTG (isopropylthiogalactopyranoside)-inducible Pspac promoter, and the ywiD mutant to generate B. subtilis MMB2, MMB4, MMB20, and MMB21, respectively.

A B. subtilis strain in which ywiD was interrupted by a kanamycin resistance gene (11) was constructed by homologous recombination using pDIA5564. Plasmid pDIA5564 was created from another pUC18 derivative (2), encompassing the 5′ end of the ywiC gene and the complete ywiD gene (pDG782). The plasmid was linearized by BclI and ligated to a BamHI-BglII restriction site-flanked kanamycin cassette, interrupting the ywiD gene after the 38th codon. Plasmid pDIA5564 was linearized and used to transform B. subtilis JH642.

A strain in which the wild-type ywiD gene was replaced by the disrupted copy, ywiD::kan (THB110), was selected as a kanamycin-resistant transformant. The ywiD::kan mutation was transferred into LAB2854 (nasD-lacZ), LAB2143 (narG-lacZ), MMB61 (lctE-lacZ), MMB57 (alsS-lacZ), MMB101 (pta-lacZ), and LAB2000 (hmp-lacZ) to generate MMB10, MMB9, MMB15, MMB14, MMB102, and MMB8, respectively. The ywiD mutation of THB110 was transferred into the fnr mutant THB2 and the resDE mutant MH5081 to generate the ywiD fnr and ywiD resDE double mutants MMB40 and MMB41, respectively. Finally, the nasD-lacZ (from LAB2854), narG-lacZ (LAB2143), lctE-lacZ (BSIP1185), alsS-lacZ (BSIP1192), ywiD-lacZ (BSIP1204), and hmp-lacZ (LAB2000) fusions were transferred to the double mutants, resulting in the strains listed in Table 1. We failed to obtain a strain carrying an alsS-lacZ fusion in a ywiD fnr mutant background.

Mutation of the fnr site upstream of ywiD from 5′-TGTGA-AATACA-TCACT-3′ to 5′-CCTGA-AATACA-TCACT-3′ localized on the ywiD-lacZ fusion-carrying plasmid pDIA5562 was performed using the Quick Change site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Heidelberg, Germany) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The resulting plasmid, pDIA5562ΔFnr, was introduced into JH642 to generate MMB25 (ywiD Δfnr-lacZ).

PCR and Southern blotting experiments were used to confirm the appropriate substitution of the wild-type gene by the mutated copy in mutant strains and to verify that only a single copy of the lacZ fusion was integrated.

Primer extension analysis of 5′ end of ywiD mRNA.

Total cellular RNA was prepared from B. subtilis using the RnEasy minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The 5′ ends of mRNAs encoded by the ywiD gene were mapped with an oligonucleotide that was complementary to positions 55 to 78 (5′-GTGCCTCTATCCATTGTCGAAACC-3′) of the ywiD gene and fluorescence labeled with 5′-indodicarbocyanine (5′-Cy5). For each experiment, 20 to 100 μg of RNA was incubated with 0.2 pmol of labeled primer for 3 min at 70°C in 34 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3)–50 mM NaCl–5 mM MgCl2–5 mM dithiothreitol. The primer-RNA hybrids were extended with 10 U of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase and 0.5 mM each nucleoside triphosphate, 12.5 mM dithiothreitol, 12.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), and 7.5 mM MgCl2 for 1 h at 42°C in the presence of 10 U of RNasin. Extension products were purified by phenol extraction, subjected to denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE), and monitored by the ALF Express system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany). A sequencing reaction performed with the same primer set was run in parallel on the same gel and allowed direct identification of the ywiD mRNA 5′ end.

HPLC analysis of B. subtilis fermentation products.

Analysis of excreted fermentation product by high-pressure liquid chromatography was performed as outlined before (3).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Reduced anaerobic growth of B. subtilis ywiD mutant.

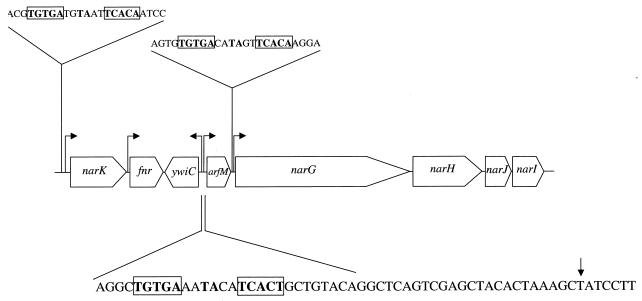

In the 5′ region of the narGHJI operon encoding respiratory nitrate reductase, an open reading frame of unknown function termed ywiD was found (Fig. 1). The open reading frame ywiD would encode a protein of 158 amino acid residues and a calculated molecular mass of 18,137 Da. The deduced protein showed no significant similarity to any other protein of known function in the database. To investigate its potential participation in anaerobic growth processes, a genomic knockout mutation of the gene was constructed and its growth behavior in minimal medium was compared to that of wild-type B. subtilis under aerobic and various anaerobic growth conditions.

FIG. 1.

nar locus of B. subtilis. The fnr gene encodes a redox regulatory protein, narK a putative nitrate/nitrite transporter protein, and narGHJI the respiratory nitrate reductase. The open reading frame arfM is the subject of this investigation. Potential Fnr binding sites are boxed. The 5′ end of the arfM mRNA is indicated by the arrow.

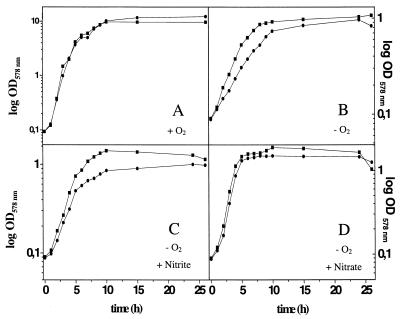

Deletion of ywiD had no obvious influence on aerobic growth (Fig. 2). However, anaerobic growth in minimal medium was significantly reduced in the presence of nitrate or nitrite and under fermentative conditions (Fig. 2). The typical biphasic anaerobic growth curve for wild-type B. subtilis on minimal medium in the presence of nitrate was not observed for the ywiD mutant. The biphasic character of the curve for anaerobic nitrate respiratory growth results from the sequential utilization of first nitrate and then nitrite (4). The observed growth curve of the ywiD mutant mirrored the anaerobic growth behavior of a nasD mutant on nitrate-containing medium, missing the growth enhancement from nitrite dissimilation via nasDE-encoded nitrite reductase (13). In agreement with this observation, reduced anaerobic growth of the ywiD mutant on nitrite-containing medium was observed (Fig. 2). Moreover, a reduction in anaerobic fermentative growth by the ywiD mutant was detected. From these results, we conclude that ywiD is generally important for anaerobic metabolism of B. subtilis. From these results and others presented below, we have renamed ywiD arfM (anaerobic respiration and fermentation modulator).

FIG. 2.

Aerobic (A) and anaerobic fermentative (B) and nitrite (C) and nitrate (D) respiratory growth of B. subtilis wild-type JH642 (▪) and the arfM mutant MMB104 (●). The minimal medium is described in Materials and Methods. Growth was monitored by determination of the OD578 at the indicated time points. Values reported are the averages from at least five independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Mutation of arfM leads to reduced nitrite reductase activity.

To differentiate between the arfM influence on various anaerobic respiratory systems, cell extracts prepared from wild-type B. subtilis and the arfM mutant grown under various anaerobic growth conditions were compared for respiratory nitrate reductase and nitrite reductase activity. No significant influence of arfM on respiratory nitrate reductase activity was observed (Table 2). This is in agreement with the anaerobic growth behavior of the arfM mutant on nitrate-containing medium. Interestingly, reduced nitrate reductase activity was observed in the wild-type and the arfM mutant under nitrite dissimilatory conditions, indicating nitrite repression (data not shown). In contrast to the results of the nitrate reductase activity measurements, the nitrite reductase activity was reduced approximately fivefold in the arfM mutant, indicating the participation of arfM in nasDE expression or nitrite reductase formation or activity (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Respiratory nitrate and nitrite reductase activities in cell extracts prepared from wild-type B. subtilis and the arfM mutanta

| B. subtilis strain | Relevant genotype | Activity ± SD (mU/mg)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrite reductase activity | Nitrate reductase activity | ||

| JH642 | Wild type | 144 ± 10 | 250 ± 10 |

| THB97 | arfM::kan | 29 ± 5 | 256 ± 10 |

NADH-dependent nitrite reductase activities were measured using cell extracts prepared from B. subtilis strains grown anaerobically in minimal medium supplemented with 10 mM nitrite as described in the text. Benzyl viologen-dependent nitrate reductase activities were determined using cell extracts prepared from B. subtilis strains grown anaerobically in minimal medium with 10 mM nitrate as outlined before (4). Values reported are the averages of at least three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

HPLC analysis of fermentation products of arfM mutant.

The amounts of the fermentation products lactate, acetate, and 2,3-butanediol excreted by wild-type B. subtilis and an arfM mutant were compared using HPLC analysis (3). The amount of accumulated lactate and 2,3-butanediol formed under all anaerobic growth conditions tested using glucose and pyruvate as carbon sources was found to be reduced by approximately 60% for the arfM mutant compared to the wild-type strain, taking the difference in growth yield between the two strains into account (data not shown). No obvious change in acetate production was observed. These results indicate an impact of arfM on lactate and 2,3-butanediol formation and provide an explanation for the arfM growth phenotype under anaerobic fermentative conditions.

arfM gene is involved in anaerobic nasDE but not narGHJI expression.

To test the influence of arfM on the transcription of various genes encoding anaerobic metabolism enzymes, the expression of reporter gene fusions of corresponding promoter regions with lacZ were tested. β-Galactosidase activities in wild-type B. subtilis and the arfM mutant grown under various anaerobic conditions were compared. In agreement with the growth phenotypes and enzymatic activities, no significant influence of arfM on narGHJI expression was found (Table 3). In agreement with the enzyme activity measurements, less narGHJI expression was observed in the presence of nitrite, again indicating nitrite inhibition (Table 3). The arfM mutation significantly reduced nasDE expression under all anaerobic growth conditions tested (Table 3). This is in agreement with the observed growth phenotype and reduced nitrite reductase activities of an arfM mutant.

TABLE 3.

Influence of regulatory genes resDE, fnr, and arfM on transcription of the nitrate and nitrite dissimilatory loci narGHJI and nasDE and the flavohemoglobin gene hmpa

| Fusion | Strain (relevant genotype) | β-Galactosidase activity (U/mg of protein)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic | Anaerobic

|

||||

| Fermentative | With nitrate | With nitrite | |||

| narG-lacZ | LAB2143 (wild type) | <10 | 811 | 852 | 455 |

| MMB71 (fnr) | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | |

| MMB78 (resDE) | <10 | 80 | 64 | 42 | |

| MMB9 (arfM) | <10 | 822 | 840 | 468 | |

| MMB51 (arfM fnr) | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 | |

| MMB55 (arfM resDE) | <10 | 42 | 35 | 21 | |

| nasD-lacZ | LAB2854 (wild type) | <10 | 251 | 1,954 | 2,452 |

| MMB70 (fnr) | <10 | 35 | 33 | 1,230 | |

| MMB77 (resDE) | <10 | 33 | 35 | 28 | |

| MMB8 (arfM) | <10 | 73 | 771 | 955 | |

| MMB48 (arfM fnr) | <10 | 25 | 35 | 872 | |

| MMB56 (arfM resDE) | <10 | <10 | <10 | 12 | |

| hmp-lacZ | LAB2000 (wild type) | <10 | 376 | 7,715 | 14,833 |

| MMB72 (fnr) | <10 | <10 | <10 | 4,011 | |

| MMB79 (resDE) | <10 | 49 | 24 | 35 | |

| MMB8 (arfM) | <10 | 211 | 2,714 | 4,212 | |

| MMB49 (arfM fnr) | <10 | 11 | <10 | 4,126 | |

| MMB57 (arfM resDE) | <10 | 25 | 15 | 16 | |

Strains were grown anaerobically, using 50 mM glucose as the carbon source and ammonia as the nitrogen source, with indicated additions (10 mM nitrate or nitrite) to the mid-exponential growth phase as outlined in detail in the text. Results represent the average of at least five independent experiments performed in triplicate, with a standard error of less than 10%.

arfM gene is involved in anaerobic hmp induction.

The hmp gene, encoding a flavohemoglobin-like protein, is another target of redox regulation in B. subtilis. The importance of resDE and nitrite for anaerobic induction of hmp was described previously (8). As outlined by LaCelle et al., the observed anaerobic induction by nitrate is of an indirect nature (8). Respiratory nitrate reductase reduces nitrate to nitrite. The nitrite formed subsequently induces hmp transcription via a still unknown regulatory system. Anaerobic hmp transcription was found to be significantly reduced in an arfM mutant under all growth conditions tested (Table 3).

arfM gene is involved in anaerobic induction of the fermentation loci lctEP and alsSD.

The involvement of fnr, resDE, alsR, and the respiratory nitrate reductase operon narGHJI in oxygen-, pH-, and nitrate-dependent lctEP and alsSD expression control was described previously (3). However, fnr was only partially responsible for anaerobic lctEP and alsSD expression. No obvious oxygen or nitrate regulation was observed for pta (3).

Reporter gene fusions of the promoter regions of the fermentation loci lctEP, alsSD, and pta were tested for the participation of arfM in their anaerobic expression. A significant reduction in anaerobic lctE-lacZ expression in an arfM mutant compared to wild-type B. subtilis was observed (Table 4). The previously observed nitrate repression of lctE transcription remained mainly unchanged (3). alsS-lacZ expression was also found to be reduced in the arfM mutant under conditions of fermentative as well as nitrate and nitrite dissimilatory growth. Again, nitrate repression of alsS-lacZ expression remained mainly unaffected (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Influence of resDE, fnr, and arfM on transcription of the fermentative loci lctEP, alsSD, and plaa

| Fusion | Strain (relevant genotype) | β-Galactosidase activity (U/mg of protein)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic | Anaerobic

|

||||

| Fermentative | With nitrate | With nitrite | |||

| lctE-lacZ | BSIP1185 (wild type) | <10 | 10,121 | 1,523 | 8,744 |

| MMB67 (fnr) | <10 | 3,125 | 2,560 | 2,746 | |

| MMB74 (resDE) | <10 | 1,505 | 1,233 | 1,304 | |

| MMB15 (arfM) | <10 | 3,237 | 782 | 2,536 | |

| MMB46 (arfM fnr) | <10 | 2,924 | 1,828 | 2,127 | |

| MMB47 (arfM resDE) | <10 | 275 | 314 | 199 | |

| alsS-lacZ | BSIP1192 (wild type) | <10 | 5,715 | 1,705 | 5,824 |

| MMB68 (fnr) | <10 | 2,513 | 2,127 | 1,827 | |

| MMB75 (resDE) | <10 | 3,798 | 3,501 | 2,117 | |

| MMB14 (arfM) | <10 | 2,525 | 759 | 1,714 | |

| MMB50 (arfM resDE) | <10 | 1,874 | 1,253 | 1,752 | |

| pta-lacZ | BSIP1104 (wild type) | 1,051 | 874 | 1,116 | 1,081 |

| MMB38 (arfM) | 993 | 1,215 | 1,189 | 1,076 | |

See Table 3, footnote a.

Consequently, arfM contributes to anaerobic lctEP and alsSD induction. No arfM involvement in pta transcription was observed (Table 4). This result was expected because pta transcription lacks obvious redox regulation (3). These results identify arfM as an important component of the redox regulatory system in B. subtilis. To investigate the relationship of arfM to the other known members of the redox system encoded by resDE and fnr, the regulation of arfM transcription was investigated.

resDE-fnr-dependent anaerobic arfM induction.

Redox-dependent arfM transcription was investigated using arfM-lacZ fusions. As shown in Table 5, arfM was exclusively expressed anaerobically. Comparable values of arfM-lacZ expression were obtained for fermentative and nitrate respiratory growth, while the presence of nitrite resulted in a 50% reduction in arfM expression. A similar reduction in anaerobic gene expression by the presence of nitrite was also observed for narGHJI transcription (see above).

TABLE 5.

Influence of resDE, fnr, and arfM on transcription of the arfM genea

| Strain (relevant genotype)b | β-Galactosidase activity (U/mg of protein)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic | Anaerobic

|

|||

| Fermentative | With nitrate | With nitrite | ||

| THB216 (wild type) | <10 | 1,027 | 1,579 | 612 |

| MMB2 (fnr) | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| MMB25 (ΔFnr site) | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| MMB20 (resDE pSpac-fnr) | ||||

| Without IPTG | <10 | 182 | 225 | 85 |

| With IPTG | <10 | 1,035 | 1,483 | 472 |

| MMB4 (resDE) | <10 | 17 | 25 | 27 |

| MMB21 (arfM) | <10 | 2,314 | 3,025 | 3,123 |

| MMB52 (arfM fnr) | <10 | <10 | <10 | <10 |

| MMB54 (arfM resDE) | <10 | 28 | 24 | 22 |

See Table 3, footnote a.

All strains carried the arfM-lacZ fusion.

Anaerobic arfM expression was completely dependent on the presence of intact fnr (Table 5). The involvement of fnr in arfM transcription was expected because the 5′ region of arfM harbors a conserved potential Fnr binding site (TGTGA-6N-TCACT). An arfM promoter analysis is described below. Anaerobic expression of arfM in a resDE mutant was found to be significantly reduced (Table 5). However, resDE-independent expression of fnr from an IPTG-inducible Pspac promoter in a resDE mutant restored anaerobic arfM expression to almost the wild-type level (Table 5). These findings indicate that the observed role of resDE in arfM expression is indirect, via resDE-dependent fnr induction. As observed for various other regulatory genes, arfM represses its own expression (Table 5).

These results suggest that the anaerobic induction of various genes of anaerobic metabolism is mediated by a regulatory cascade consisting of an unknown signal, resDE, fnr, and arfM. Investigation of the contribution of this potential regulatory cascade to the induction of various anaerobic loci using regulatory double mutants in combination with reporter gene fusions is described below.

Analysis of fnr-dependent arfM promoter.

Primer extension analysis revealed a single 5′ end for arfM mRNA (data not shown). A transcriptional start site located 25 bp from the translational start was determined (Fig. 1). Signal intensities during the primer extension experiments varied depending on the growth conditions used for the B. subtilis employed for RNA isolation. In agreement with the reporter gene fusions, primer extension signals were only observed with RNA prepared from anaerobically grown B. subtilis. Centered at 40.5 bp upstream of the transcriptional start, we found a DNA sequence (TGTGA-N6-TCACT) with a high degree of sequence identity to potential B. subtilis Fnr binding sites.

However, no direct experimental proof was available for the function of this promoter element in B. subtilis. Therefore, the upstream half of the palindromic sequence was mutated from 5′-TGTGA-3′ to 5′-CCTGA-3′. As shown in Table 5, the mutations in the putative Fnr-box (strain MMB25) completely abolished anaerobic induction of arfM. These results confirmed the complete fnr dependence of anaerobic arfM induction and experimentally verified the 5′-TGTGA-N6-TCACT-3′ sequence as the Fnr-box.

Role of resDE-fnr-arfM regulatory cascade for differential anaerobic gene expression.

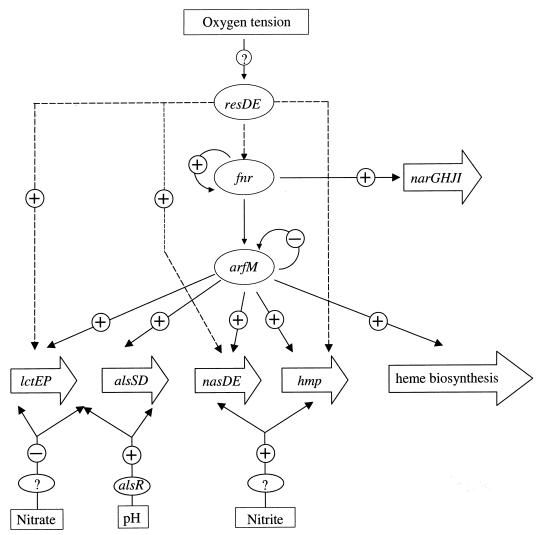

The results from the experiments described above and from a previous study of B. subtilis hemN and hemZ expression led us to propose a model for arfM function (Fig. 3). The protein encoded by arfM is currently the last part of a regulatory chain in B. subtilis responsible for adaptation to anaerobic growth conditions. The signal of low oxygen tension is measured by a still unknown receptor and transferred directly or indirectly to the two-component regulatory system ResDE. Subsequently ResDE directly activates fnr transcription (14). Moreover, several other genes of anaerobic metabolism such as hmp and nasDE are influenced directly in their expression by resDE.

FIG. 3.

Proposed regulatory cascade involved in the induction of gene expression under low oxygen tension conditions in B. subtilis (2, 3, 6, 8, 13, 13, 16, 20, 21). Various stimuli (oxygen tension, nitrate, nitrite, and pH) are transferred and integrated via various regulatory loci (resDE, fnr, arfM, and alsR) to differentially control the expression of various metabolic target genes encoding respiratory nitrate reductase (narGHJI), nitrite reductase (nasDE), flavohemoglobin-like protein (hmp), enzymes of lactate (lctEP) and acetoin (alsSD) fermentation and heme biosynthesis (hemN and hemZ).

Fnr directly activates the most efficient anaerobic mode of ATP generation, nitrate respiration, via induction of the nitrate reductase operon narGHJI and nitrate/nitrite transporter genes. Fnr also activates arfM transcription. Finally, arfM modulates the expression of genes encoding proteins which further sustain nitrate respiration, such as heme biosynthesis genes (6). It also enhances alternative modes of ATP generation to nitrate respiration such as fermentation and nitrite dissimilation. This level of the molecular response to anaerobiosis is further fine tuned by additional environmental and cellular stimuli mediated by additional unknown redox regulatory components, by a pH-responding system, and by nitrate as well as nitrite regulatory systems (15).

In order to obtain further evidence for this regulatory model (Fig. 3), double mutant strains defective in resDE, fnr, or arfM were constructed, and the expression patterns of lacZ reporter gene fusions with all investigated genes were measured (Tables 3 and 4). Combination of the arfM mutation with the fnr or resDE mutation did not significantly change their already detrimental effects on narG-lacZ expression (Table 3). As expected, combining the arfM and fnr mutations resulted in similar β-galactosidase activity values resulting from nasD-lacZ and hmp-lacZ expression compared to expression in a simple fnr mutant (Table 3). Combination of the arfM and resDE mutations led to a complete loss of transcription from the nasD and hmp promoters. These additive effects were expected due to the significant direct role of resDE in nasDE and hmp transcription.

The comparable β-galactosidase activity values derived from the lctE-lacZ fusion in the arfM and fnr single mutants as well as the arfM fnr double mutant are in good agreement with our cascade regulatory model (Table 4). The lower values from the resDE mutants are in agreement with the previously determined independent role of resDE in lctE expression (3). This conclusion is further sustained by the significantly reduced lctE expression in a resDE arfM double mutant. The similar values obtained for alsS-lacZ expression in resDE, fnr, and arfM mutants and the arfM resDE double mutant are in agreement with the proposed regulatory cascade. Surprisingly, no arfM fnr double mutant carrying an alsS-lacZ fusion was obtained. The reason remains unclear.

Previously, we described the nitrate repression of lctE-lacZ and alsS-lacZ mediated by the presence of intact narGHJI. In agreement with the lack of arfM influence on narGHJI transcription, the arfM mutation did not significantly affect nitrate repression. Combination of an arfM mutation with either an fnr or a resDE mutation resulted in the loss of nitrate repression due to decreased narGHJI expression. For similar reasons, anaerobic nasD-lacZ and hmp-lacZ expression in the presence of nitrate was reduced in an arfM mutant and totally abolished in an fnr mutant (Table 3). In the fnr mutant, narGHJI expression is greatly reduced. The synthesis of the strongly stimulatory nitrite from nitrate by nitrate reductase is missing. Since the arfM mutation has no effect on narGHJI expression, the combination of both regulatory mutations resulted in the expected fnr mutant-like expression pattern.

Similar to findings for B. subtilis hemN and hemZ transcription, nasDE, hmp, lctEP, and alsSD transcription is subject to resDE-fnr-arfM cascade regulation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, the Sonderforschungsbereich 388, Fonds der Chemischen Industrie, and the Graduiertenkolleg “Biochemie der Enzyme.” This research was also supported by grants from the Ministère de l'Education Nationale de la Recherche et de la Technologie, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (URA1129), Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Institut Pasteur, Université Paris 7, and European Union Biotech Programme (contracts ERBB102 CT930272 and ERBB104 CT960655).

We are indebted to M. Nakano (Louisiana State University) and F. M. Hulett (University of Illinois in Chicago) for the gift of B. subtilis mutants. We thank R. K. Thauer (Max-Planck-Institut, Marburg, Germany) for continuous support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chung C T, Miller R H. A rapid and convenient method for the preparation and storage of competent bacterial cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:3580. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.8.3580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cruz Ramos H, Boursier L, Moszer I, Kunst F, Danchin A, Glaser P. Anaerobic transcription activation in Bacillus subtilis: identification of distinct FNR-dependent and -independent regulatory mechanisms. EMBO J. 1995;14:5984–5994. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cruz Ramos H, Hoffmann T, Marino M, Presecan-Siedel E, Nedjari H, Dreesen O, Longin R, Glaser P, Jahn D. The fermentative metabolism of Bacillus subtilis: physiology and regulation of gene expression. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3072–3080. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.11.3072-3080.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffmann T, Frankenberg N, Marino M, Jahn D. Ammonification in Bacillus subtilis utilizing dissimilatory nitrite reductase is dependent on resDE. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:186–189. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.1.186-189.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffmann T, Troup B, Szabo A, Hungerer C, Jahn D. The anaerobic life of Bacillus subtilis: cloning and characterization of the genes encoding the respiratory nitrate reductase system. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;131:219–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Homuth G, Rompf A, Schumann W, Jahn D. Characterization of Bacillus subtilis hemZ. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5922–5929. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.5922-5929.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kunst F, Rapoport G. Salt stress is an environmental signal affecting degradative enzyme synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2403–2407. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2403-2407.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaCelle M, Kumano M, Kurita K, Yamane K, Zuber P, Nakano M M. Oxygen-controlled regulation of the flavohemoglobin gene in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3803–3808. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3803-3808.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mach H, Hecker M, Mach F. Physiological studies on cAMP synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1988;52:189–192. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy E. Nucleotide sequence of a spectinomycin adenyltransferase AAD(9) determinant from Staphylococcus aureus and its relationship to AAD(3")(9) Mol Gen Genet. 1985;200:33–39. doi: 10.1007/BF00383309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakano M M, Dailly Y P, Zuber P, Clark D P. Characterization of anaerobic fermentative growth of Bacillus subtilis: identification of fermentation end products and genes required for growth. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6749–6755. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6749-6755.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakano M M, Hoffmann T, Zhu Y, Jahn D. Nitrogen and oxygen regulation of Bacillus subtilis nasDEF encoding NADH-dependent nitrite reductase by TnrA and ResDE. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5344–5350. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.20.5344-5350.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakano M M, Zhu Y, LaCelle M, Zhang X, Hulett F M. Interaction of ResD with regulatory regions of anaerobically induced genes in Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:1198–1207. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakano M M, Zuber P. Anaerobic growth of a “strict aerobe” (Bacillus subtilis) Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:165–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakano M M, Zuber P, Glaser P, Danchin A, Hulett F M. Two-component regulatory proteins ResD-ResE are required for transcriptional activation of fnr upon oxygen limitation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3796–3802. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3796-3802.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perego M. Integrational vectors for genetic manipulation in Bacillus subtilis. In: Sonenshein A L, Hoch J A, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria: biochemistry, physiology, and molecular genetics. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1993. pp. 615–624. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Presecan-Siedel E, Galinier A, Longin R, Deutscher J, Danchin A, Glaser P, Martin-Verstraete I. Catabolite regulation of the pta gene as part of the carbon flow pathways in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6889–6897. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.22.6889-6897.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Presecan E, Moszer I, Boursier L, Cruz Ramos H C, de la Fuente V, Hullo M F, Lelong C, Schleich S, Sedowska A, Song B H, Villani G, Kunst F, Danchin A, Glaser P. The Bacillus subtilis genome from gerBC (311 degrees) to licR (334 degrees) Microbiology. 1997;143:3318–3328. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-10-3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Renna M C, Najimudin N, Winik L R, Zahler S A. Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis alsS, alsD, and alsR genes involved in post-exponential-phase production of acetoin. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3863–3875. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.12.3863-3875.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun G, Sharkova E, Chesnut R, Birkey S, Duggan M F, Sorokin A, Pujic P, Ehrlich S D, Hulett F M. Regulators of aerobic and anaerobic respiration in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1374–1385. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1374-1385.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]