Abstract

Background

Deep learning breast cancer risk models demonstrate improved accuracy compared with traditional risk models but have not been prospectively tested. We compared the accuracy of a deep learning risk score derived from the patient’s prior mammogram to traditional risk scores to prospectively identify patients with cancer in a cohort due for screening.

Methods

We collected data on 119 139 bilateral screening mammograms in 57 617 consecutive patients screened at 5 facilities between September 18, 2017, and February 1, 2021. Patient demographics were retrieved from electronic medical records, cancer outcomes determined through regional tumor registry linkage, and comparisons made across risk models using Wilcoxon and Pearson χ2 2-sided tests. Deep learning, Tyrer-Cuzick, and National Cancer Institute Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool (NCI BCRAT) risk models were compared with respect to performance metrics and area under the receiver operating characteristic curves.

Results

Cancers detected per thousand patients screened were higher in patients at increased risk by the deep learning model (8.6, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 7.9 to 9.4) compared with Tyrer-Cuzick (4.4, 95% CI = 3.9 to 4.9) and NCI BCRAT (3.8, 95% CI = 3.3 to 4.3) models (P < .001). Area under the receiver operating characteristic curves of the deep learning model (0.68, 95% CI = 0.66 to 0.70) was higher compared with Tyrer-Cuzick (0.57, 95% CI = 0.54 to 0.60) and NCI BCRAT (0.57, 95% CI = 0.54 to 0.60) models. Simulated screening of the top 50th percentile risk by the deep learning model captured statistically significantly more patients with cancer compared with Tyrer-Cuzick and NCI BCRAT models (P < .001).

Conclusions

A deep learning model to assess breast cancer risk can support feasible and effective risk-based screening and is superior to traditional models to identify patients destined to develop cancer in large screening cohorts.

Because of limited resources related to the COVID-19 pandemic in early summer 2020, medical experts and state governments urged providers to focus screening efforts on patients at increased risk (1-3). Before the pandemic, risk-based mammography screening was not part of routine clinical practice, partly because of modest performance of traditional risk models. In addition, concerns regarding racial biases of traditional risk models had many health-care centers reluctant to support differential access to screening based on risk models that favor European Caucasian populations over Asian, Black, and Hispanic populations (4-8).

A deep learning risk model, based on the patient’s mammogram images alone, has proven superior predictive accuracy in future breast cancer risk assessment compared with traditional risk models across 7 global institutions, including patients of diverse races and ethnicities (9,10). The deep learning model has advantages beyond accuracy, as it does not require knowledge of the patient’s family history or personal history of prior biopsy and pathology, hormone use, menopausal status, or other risk factors required by traditional risk models (11–14). Traditional risk models have demonstrated modest performance in White non-Hispanic patients and worse performance in Black, Asian, and Hispanic populations (15-19). Traditional risk models are not indicated for use in patients with a personal history of breast cancer or known genetic mutation and may overestimate risk in patients with history of atypia or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) (20,21). The deep learning model has demonstrated equivalent predictive accuracy across diverse patient ages, races, and breast densities and has been trained and validated in all patients undergoing screening, including those with a known genetic mutation and/or personal history of breast cancer (9,10). Despite these advantages, whether a deep learning model can support effective risk-based screening in clinical practice is unknown. We compared the ability of a deep learning risk score, derived solely from a patient’s prior mammogram, with traditional risk scores to identify patients most likely to be diagnosed with cancer in a large cohort due for screening. We then simulated a screening program that first screened patients comprising the top 50th percentile of risk and the subsequent impact on cancers detected and false-positive exams avoided in a population due for screening when using deep learning vs traditional risk models.

Methods

The institutional review board of Mass General Brigham exempted this Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant study from the requirement for written informed consent.

Patients

Our study population included consecutive patients screened with bilateral mammography at 5 facilities on digital mammography units (Hologic, Bedford, MA, USA) from September 18, 2017, to February 1, 2021, and who had a prior screening mammogram in our system. From our electronic medical records, we recorded age, self-reported race and ethnicity, personal and family history of breast cancer, breast density, lifetime and 5-year breast cancer risk determined by Tyrer-Cuzick (v8) and National Cancer Institute Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool (NCI BCRAT) models and 5-year risk determined by the deep learning model. The deep learning risk score was derived from the most recent prior screening mammogram obtained since 2015. Race and ethnicity were self-reported and categorized as African American or Black, Asian or Pacific Islander, Hispanic, White, or as all other races and ethnicities. Given the large percentage of patients who self-identified as White, race and ethnicity were further classified in a binary manner for purposes of data analysis as White or as all other races and ethnicities (hereafter referred to as races other than White).

Deep Learning Image-Based 5-Year Risk Model Evaluation

The deep learning model in this study has been described previously (9,10). For training, the model takes as input the 4 standard, 2-dimensional mammographic views. Each image is processed through the image encoder and passed through the aggregation module to combine information across views for a representation of the entire mammogram. The model is referred to as “image only” as no information outside of the mammogram is provided to the model. Architectural details for the deep learning model are available online, and all code is released and open source (9,10,22).

For every screening mammogram, we recorded the deep learning score based on the mammogram image alone. The mammograms in our study were not used in the original model training, and the model was used as is and was not retrained on the current study cohort.

Deep Learning and Traditional Risk Score Categorizations

For each patient, we assessed deep learning, Tyrer-Cuzick, and NCI BCRAT 5-year and Tyrer-Cuzick and NCI BCRAT lifetime risk scores and divided patients into the top and bottom 50th percentiles (above vs below the median score) based on their scores calculated by each risk model. This resulted in the following thresholds for increased risk: deep learning at least 2.17%, Tyrer-Cuzick at least 1.45%, NCI BCRAT at least 1.40% for 5-year and Tyrer-Cuzick at least 7.90% and NCI BCRAT at least 7.80% for lifetime risk. As opposed to using traditional thresholds, this methodology of defining at-risk patients is more portable across diverse populations, and the quantile that defines the increased risk threshold for a given population can be adjusted to fit local resources and goals for risk-based interventions.

Screening Mammography Outcomes

Screening mammography outcomes, including cancer detection rate (CDR), abnormal interpretation rate, and positive predictive values (1,2,3), were calculated following definitions established by the American College of Radiology and the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (23) with the reference standard of positive for cancer defined as breast cancer (invasive or ductal carcinoma in situ) pathologically verified within 365 days of the screening mammogram.

Statistical Analyses

We compared the distribution of patient characteristics in the top vs bottom 50th percentile of deep learning, Tyrer-Cuzick, and NCI BCRAT risk scores using the Wilcoxon test (for continuous variables) and the Pearson χ2 test (for categorical variables). We compared performance metrics of mammography between the top and bottom 50th percentile risk scores from all risk models, as well as between the Tyrer-Cuzick and NCI BCRAT risk models using traditional thresholds (intermediate 5-year risk ≥ 1.67% and lifetime risk ≥ 20%).

Areas under the receiver-operating-characteristic curve (AUCs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated for each risk model and compared with the DeLong test. Because Tyrer-Cuzick and NCI BCRAT models do not generate risk scores for all patients, such as those with a personal history of breast cancer or LCIS, known genetic mutation, prior therapeutic chest radiation, and/or certain ages, we also estimated and compared AUCs of risk models in the subgroup of patients who had valid risk scores derived from all 5 risk models.

In simulated screening of the top 50th percentile of at-risk patients, we compared the percentage of cancers detected and the number of false-positive exams avoided across the risk models. We performed these comparisons for all patients with any risk scores and in the subgroup of patients who had valid risk scores by all 5 risk models. We performed subgroup analyses based on patient self-report of race and ethnicity (White vs races other than White). A type I error of 5% was used for all confidence intervals and 2-sided hypothesis tests. All data were analyzed with statistical software R version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2018). The packages rms and pROC were used in analyses.

Results

Study Population

From September 18, 2017, to February 1, 2021, 57 635 consecutive patients with a prior mammogram underwent 119 179 bilateral screening mammograms. A total of 40 exams and 18 patients were excluded as they had a nonbreast cancer malignancy (lymphoma) diagnosis after biopsy or had no valid risk scores by any of the models in their medical records, resulting in our final analysis set of 119 139 screening mammograms in 57 617 patients (Supplementary Figure 1, available online).

Patient Characteristics in Top vs Bottom 50th Percentile of Risk Scores

Compared with patients in the bottom 50th percentile of deep learning risk scores, patients assigned deep learning scores in the top 50th percentile were more likely to be older (median age of 6 years, interquartile range [IQR] = 55.0-72.0 vs 58.0 years, IQR = 50.0-66.0; P < .001), self-report being White race (85.8% vs 82.7%; P < .001), have dense breast tissue (43.8% vs 33.3% heterogeneous or extremely dense breast tissue; P < .001), have a personal history of breast cancer (21.2% vs 6.5%; P < .001), and have a family history of breast cancer (24.4% vs 22.0%; P < .001). Patients in the top vs bottom 50th percentile of deep learning risk scores also had higher risk scores by both the Tyrer-Cuzick and the NCI BCRAT 5-year models (1.75%, IQR = 1.25%-2.70% vs 1.55%, IQR = 1.10%-2.25%, and 1.80%, IQR = 1.40%-2.50% vs 1.60%, IQR = 1.20%-2.10%, respectively; P < .001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of mammograms grouped by deep learning risk score in patients with valid scores by all models: top vs bottom 50th percentile

| Characteristic | DL 5-year risk top 50%a | DL 5-year risk bottom 50%a | Combined |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. | 46 261 | 46 261 | 92 522 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 62.0 (53.0-70.0) | 57.0 (50.0-65.0) | 59.0 (51.0-68.0) |

| Race, No. (%)b | |||

| Race other than White | 7464 (16.4) | 8377 (18.5) | 15 841 (17.4) |

| Asian | 2397 (5.3) | 2820 (6.2) | 5217 (5.8) |

| Black | 2252 (5.0) | 2353 (5.2) | 4605 (5.1) |

| Hispanic | 840 (1.9) | 867 (1.9) | 1707 (1.9) |

| Other | 1975 (4.4) | 2337 (5.2) | 4312 (4.8) |

| White | 37 925 (83.6) | 37 009 (81.5) | 74 934 (82.6) |

| Mammographic breast density, No. (%)c | |||

| Fatty | 1392 (3.0) | 4861 (10.5) | 6253 (6.8) |

| Scattered fibroglandular | 23 211 (50.3) | 26 505 (57.4) | 49 716 (53.9) |

| Heterogeneously dense | 19 866 (43.1) | 13 733 (29.7) | 33 599 (36.4) |

| Extremely dense | 1680 (3.6) | 1071 (2.3) | 2751 (3.0) |

| Personal history of breast cancer, No. (%) | |||

| No | 46 207 (99.9) | 46 231 (99.9) | 92 438 (99.9) |

| Yes | 54 (0.1) | 30 (0.1) | 84 (0.1) |

| Family history of breast cancer, No. (%) | |||

| No | 35 429 (76.6) | 36 283 (78.4) | 71 712 (77.5) |

| Yes | 10 832 (23.4) | 9978 (21.6) | 20 810 (22.5) |

| DL 5-year risk score, median (IQR) | 2.89 (2.36-5.22) | 1.49 (1.24-1.77) | 2.05 (1.49-2.89) |

| TC 5-year risk score, median (IQR) | 1.75 (1.25-2.70) | 1.50 (1.10-2.25) | 1.65 (1.15-2.45) |

| NCI BCRAT 5-year risk score, median (IQR) | 1.80 (1.30-2.50) | 1.60 (1.20-2.10) | 1.70 (1.20-2.30) |

| TC lifetime risk score, median (IQR) | 9.20 (5.30-14.30) | 9.30 (6.00-13.70) | 9.20 (5.70-14.00) |

| NCI BCRAT lifetime risk score, median (IQR) | 8.80 (5.90-12.10) | 9.30 (6.70-12.00) | 9.10 (6.30-12.00) |

All comparisons between top and bottom DL 5-year risk groups are statistically significant at P < .01 (Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables, and χ2 test for categorical variables). DL = deep learning; IQR = interquartile range; NCI BCRAT = National Cancer Institute Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool; TC = Tyrer-Cuzick.

Self-reported race and ethnicity unknown in 1747 exams.

Density unknown in 203 exams.

Compared with patients in the bottom 50th percentile, patients in the top 50th percentile of Tyrer-Cuzick and NCI BCRAT 5-year risk scores were more likely to self-report being White (88.2% vs 75.0% for Tyrer-Cuzick, 89.3% vs 67.8% for NCI BCRAT; both P < .001) and more likely to report a family history of breast cancer (32.4% vs 7.8% for Tyrer-Cuzick, 27.4% vs 11.8% for NCI BCRAT; both P < .001). Patients in the top 50th percentile by Tyrer-Cuzick 5-year risk scores were more likely to have dense breast tissue (46.6% vs 27.8%; P < .001); patients in the top 50% by NCI BCRAT 5-year risk were less likely to have dense breast tissue (36.1% vs 46.8%; P < .001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics of mammograms grouped by TC and NCI BCRAT 5-year risk scores in patients with valid scores by all models: top vs bottom 50th percentile

| Characteristic | TC 5-year risk top 50%a | TC 5-year risk bottom 50%a | NCI BCRAT 5-year risk top 50%a | NCI BCRAT 5-year risk bottom 50%a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total No. | 46 665 | 45 857 | 47 662 | 44 860 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 61.0 (54.0-68.0) | 57.0 (49.0-68.0) | 65.0 (59.0-71.0) | 53.0 (47.0-60.0) |

| Race, No. (%)b | ||||

| Race other than White | 4998 (10.9) | 10 843 (24.2) | 4329 (9.2) | 11 512 (26.2) |

| Asian | 1797 (3.9) | 3420 (7.6) | 1141 (2.4) | 4076 (9.3) |

| Black | 1686 (3.7) | 2919 (6.5) | 1656 (3.5) | 2949 (6.7) |

| Hispanic | 425 (0.9) | 1282 (2.9) | 425 (0.9) | 1282 (2.9) |

| Other | 1090 (2.4) | 3222 (7.2) | 1107 (2.4) | 3205 (7.3) |

| White | 40 897 (89.1) | 34 037 (75.8) | 42 571 (90.8) | 32 363 (73.8) |

| Mammographic breast density, No. (%)c | ||||

| Fatty | 1810 (3.9) | 4443 (9.7) | 3461 (7.3) | 2792 (6.2) |

| Scattered fibroglandular | 22 243 (47.8) | 27 473 (60.1) | 26 997 (56.8) | 22 719 (50.8) |

| Heterogeneously dense | 20 416 (43.8) | 13 183 (28.8) | 15 962 (33.6) | 17 637 (39.4) |

| Extremely dense | 2107 (4.5) | 644 (1.4) | 1131 (2.4) | 1620 (3.6) |

| Family history of breast cancer, No. (%) | ||||

| No | 29 669 (63.6) | 42 043 (91.7) | 32 797 (68.8) | 38 915 (86.8) |

| Yes | 16 996 (36.4) | 3814 (8.3) | 14 865 (31.2) | 5945 (13.2) |

All comparisons between top and bottom 5-year risk groups are statistically significant at P < .05 (Wilcoxon rank-sum 2-sided test for continuous variables and χ2 2-sided test for categorical variables). IQR = interquartile range; NCI BCRAT = National Cancer Institute Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool; TC = Tyrer-Cuzick.

Self-reported race and ethnicity unknown in 1747 exams.

Density unknown in 203 exams.

Screening Mammography Performance in Patients by Deep Learning vs Traditional Risk Models

The deep learning model surpassed the Tyrer-Cuzick and NCI BCRAT models in distinguishing patients with higher cancer prevalence in the population due for screening. The CDR for patients in the top half of deep learning risk scores was highest at 8.6 per 1000 (95% CI = 7.9 to 9.4). This yield was statistically significantly higher than that identified by the Tyrer-Cuzick (4.4 per 1000, 95% CI = 3.9 to 4.9) and NCI BCRAT 5-year models (3.8 per 1000, 95% CI = 3.3 to 4.3; P < .001 for both). Neither the Tyrer-Cuzick nor NCI BCRAT lifetime risk models had performance metrics that would support effective strategies in triaging patients with higher cancer risk (Table 3). Similar findings were seen when using traditional risk thresholds of at least 1.67% for 5-year risk and at least 20% for lifetime risk, except that the CDR with NCI BCRAT lifetime risk of at least 20% was statistically significantly higher than that for those with lifetime risk of less than 20% (6.5 per 1000, 95% CI = 4.5 to 9.4, vs 3.4 per 1000, 95% CI = 3.1 to 3.8; P = .001) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Screening mammography performance across deep learning and traditional risk score groups: top vs bottom 50th percentile

| Risk score | Cancer detection rate (per 1000) No. (95% CI) | Abnormal interpretation rate % (95% CI) | PPV1 % (95% CI) | PPV2 % (95% CI) | PPV3 % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DL 5-year risk | |||||

| No. | 118 799 | 118 799 | 6908 | 1369 | 1290 |

| Top 50% | 8.6 (7.9 to 9.4) | 6.8 (6.6 to 7.0) | 12.7 (11.7 to 13.8) | 50.6 (47.5 to 53.8) | 52.4 (49.2 to 55.6) |

| Bottom 50% | 2.8 (2.4 to 3.3) | 4.8 (4.7 to 5.0) | 5.8 (5.0 to 6.8) | 39.2 (34.6 to 44.1) | 40.4 (35.6 to 45.5) |

| Pa | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| TC 5-year risk | |||||

| No. | 101 384 | 101 384 | 5718 | 931 | 871 |

| Top 50% | 4.4 (3.9 to 4.9) | 5.8 (5.7 to 6.0) | 7.4 (6.6 to 8.4) | 39.5 (35.8.8 to 43.4) | 40.3 (36.4 to 44.3) |

| Bottom 50% | 2.7 (2.2 to 3.2) | 5.3 (5.1 to 5.6) | 5.0 (4.2 to 6.0) | 34.5 (29.3 to 40.0) | 37.0 (31.5 to 42.9) |

| Pa | <.001 | .001 | <.001 | .14 | .35 |

| NCI BCRAT 5-year risk | |||||

| No. | 92 787 | 92 787 | 5267 | 835 | 782 |

| Top 50% | 3.8 (3.3 to 4.3) | 5.3 (5.1 to 5.5) | 7.1 (6.3 to 8.1) | 37.1 (33.3 to 41.0) | 38.1 (34.2 to 42.1) |

| Bottom 50% | 2.8 (2.3 to 3.5) | 6.5 (6.3 to 6.8) | 4.4 (3.5 to 5.4) | 34.2 (28.3 to 40.6) | 35.9 (29.7 to 42.5) |

| Pa | .03 | <.001 | <.001 | .45 | .57 |

| TC lifetime risk | |||||

| No. | 101 384 | 101 384 | 5718 | 931 | 871 |

| Top 50% | 3.7 (3.3 to 4.2) | 6.4 (6.2 to 6.6) | 5.8 (5.1 to 6.6) | 34.4 (30.8 to 38.3) | 35.8 (32.0 to 39.9) |

| Bottom 50% | 3.7 (3.1 to 4.3) | 4.6 (4.4 to 4.8) | 8.0 (6.9 to 9.3) | 44.3 (39.1 to 49.8) | 45.6 (40.1 to 51.2) |

| Pa | .86 | <.001 | .002 | .003 | .005 |

| NCI BCRAT lifetime risk | |||||

| No. | 95 805 | 95 805 | 5439 | 861 | 807 |

| Top 50% | 3.3 (2.9 to 3.8) | 6.1 (6.0 to 6.3) | 5.4 (4.8 to 6.2) | 32.2 (28.5 to 36.1) | 33.1 (29.3 to 37.2) |

| Bottom 50% | 3.9 (3.3 to 4.6) | 4.9 (4.7 to 5.1) | 7.9 (6.7 to 9.2) | 46.6 (40.9 to 52.5) | 48.5 (42.6 to 54.5) |

| Pa | .19 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

χ2 2-sided test. CI = confidence interval; DL = deep learning; NCI BCRAT = National Cancer Institute Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool; PPV = positive predicted value; TC = Tyrer-Cuzick.

Table 4.

Screening mammography performance across deep learning and traditional risk score groups at traditional thresholds

| Risk score | Cancer detection rate (per 1000) No. (95% CI) | Abnormal interpretation rate % (95% CI) | PPV1 % (95% CI) | PPV2 % (95% CI) | PPV3 % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TC 5-year risk | |||||

| No. | 101 384 | 101 384 | 5718 | 931 | 871 |

| ≥1.67 | 4.8 (4.2 to 5.4) | 6.0 (5.8 to 6.2) | 8.0 (7.1 to 9.1) | 40.7 (36.7 to 44.9) | 41.9 (37.7 to 46.2) |

| <1.67 | 2.7 (2.3 to 3.2) | 5.3 (5.2 to 5.5) | 5.0 (4.3 to 5.9) | 34.0 (29.5 to 38.9) | 35.5 (30.7 to 40.6) |

| Pa | <.001 | .001 | <.001 | .04 | .06 |

| NCI BCRAT 5-year risk | |||||

| No. | 92 787 | 92 787 | 5267 | 835 | 782 |

| ≥1.67 | 4.0 (3.5 to 4.7) | 5.3 (5.1 to 5.5) | 7.6 (6.6 to 8.7) | 37.6 (33.4 to 42.0) | 38.4 (34.0 to 42.9) |

| <1.67 | 2.9 (2.4 to 3.4) | 6.0 (5.8 to 6.3) | 4.8 (4.1 to 5.7) | 34.5 (29.7 to 39.6) | 36.2 (31.2 to 41.6) |

| Pa | .003 | <.001 | <.001 | .35 | .53 |

| TC lifetime risk | |||||

| No. | 101 384 | 101 384 | 5718 | 931 | 871 |

| ≥20 | 3.6 (3.2 to 4.0) | 5.5 (5.3 to 5.6) | 6.5 (5.9 to 7.3) | 38.5 (35.2 to 41.9) | 40.0 (36.5 to 43.5) |

| <20 | 4.7 (3.6 to 6.2) | 7.2 (6.7 to 7.7) | 6.6 (5.0 to 8.5) | 34.6 (27.1 to 42.9) | 35.2 (27.4 to 43.8) |

| Pa | .06 | <.001 | .98 | .38 | .30 |

| NCI BCRAT lifetime risk | |||||

| No. | 95 805 | 95 805 | 5439 | 861 | 807 |

| ≥20 | 6.5 (4.5 to 9.4) | 6.8 (6.0 to 7.6) | 9.6 (6.7 to 13.6) | 30.9 (21.9 to 41.6) | 32.9 (23.4 to 44.1) |

| <20 | 3.4 (3.1 to 3.8) | 5.6 (5.5 to 5.8) | 6.1 (5.4 to 6.7) | 37.6 (34.2 to 41.0) | 38.7 (35.3 to 42.3) |

| Pa | .001 | .002 | .02 | .23 | .32 |

χ2 2-sided test. CI = confidence interval; NCI BCRAT = National Cancer Institute Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool; PPV = positive predicted value; TC = Tyrer-Cuzick.

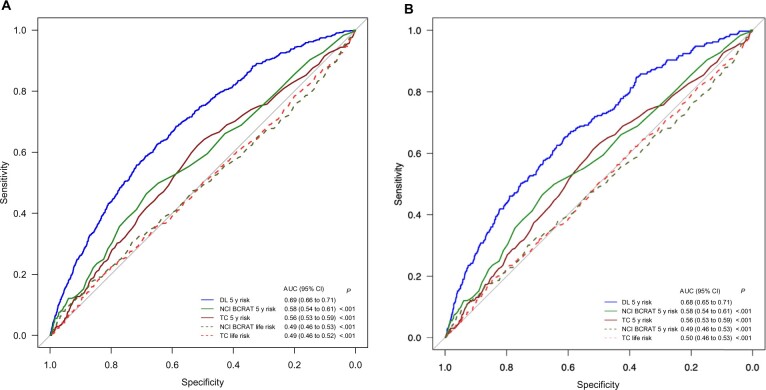

Comparison of Risk Models by Receiver Operating Characteristic Analyses by AUC

The deep learning 5-year risk model had the highest discriminatory performance by AUC (0.68, 95% CI = 0.66 to 0.70), followed by the NCI BCRAT (0.57, 95% CI = 0.54 to 0.60) and the Tyrer-Cuzick 5-year risk model (0.57, 95% CI = 0.54 to 0.60) (Figure 1, A). NCI BCRAT and Tyrer-Cuzick lifetime risk models had poor discriminatory performance, both with AUCs of 0.50. When compared with each traditional risk model, the deep learning 5-year model had statistically significantly better performance (all P < .001). Traditional risk models typically exclude patients with a personal history of breast cancer or LCIS, genetic mutation, prior radiation therapy, and/or certain ages. To address this limitation, we compared AUCs across all models in the subgroup of the population who had risk scores assigned by all 5 models. The deep learning model’s higher discriminatory performance compared with all other models persisted when evaluated in the subgroup of patients who had valid scores from all 5 risk models (Figure 1, B).

Figure 1.

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of breast cancer risk models for (A) all exams and (B) exams with valid scores from all 5 risk models. *Delong 2-sided test comparing AUCs between each risk score and the deep learning 5-year score. CI = confidence interval; DL = deep learning; NCI BCRAT = National Cancer Institute Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool; TC = Tyrer-Cuzick.

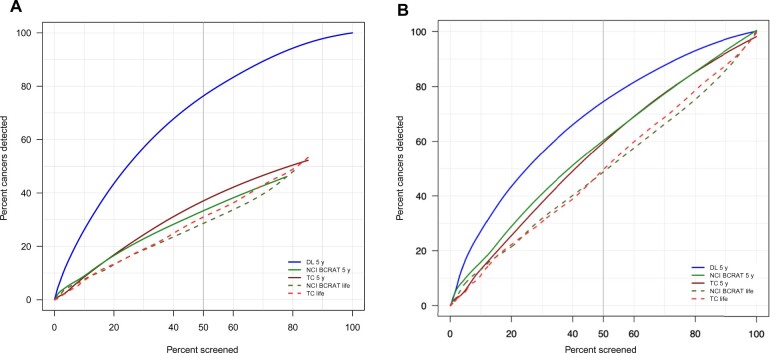

Simulation of Screening Top 50th Percentile of Population Based on Deep Learning vs Traditional Models

When simulating inviting the top 50th percentile patients to be screened based on each risk model, the deep learning risk score captured the highest percentage of cancers (75.2%, 95% CI = 71.8% to 78.3%) compared with 39.2% (95% CI = 35.6% to 42.9%) with the Tyrer-Cuzick 5-year and 35.2% (95% CI = 26.5% to 32.8%) with the NCI BCRAT 5-year risk scores (Table 3). Neither the Tyrer-Cuzick nor NCI BCRAT lifetime risk models effectively identified patients with higher cancer burden. In the subset of patients with valid scores across all 5 risk models, simulating inviting to screen the top 50th percentile of patients based on their deep learning score captured the highest percentage of patients with cancer (72.7%, 95% CI = 67.6% to 77.3%) compared with 63.7% (95% CI = 58.3% to 68.7%) with the Tyrer-Cuzick 5-year model and 59.6% (95% CI = 54.2% to 64.8%) with the NCI BCRAT 5-year model (P < .05 for both). Neither the Tyrer-Cuzick nor the NCI BCRAT lifetime risk models effectively identified patients with higher cancer burden (Table 5, Figure 2).

Table 5.

Outcomes based on simulated priority screening of patients at varying risk score thresholds by deep learning and traditional risk models

| Risk thresholds for patients invited to screening | Invited to screening |

Cancers detected |

False positives avoided |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) | |

| All patients total | 119 139 | 681 | 6246 | |||

| Risk model scoresa | ||||||

| DL 5-year top 50% | 59 334 | 49.8 (49.5 to 50.1) | 512 | 75.2 (71.8 to 78.3) | 2729 | 43.7 (42.5 to 44.9) |

| TC 5-year top 50% | 61 373 | 51.5 (51.2 to 51.8) | 267 | 39.2 (35.6 to 42.9) | 2926 | 46.9 (45.6 to 48.1) |

| NCI BCRAT 5-year top 50% | 63 596 | 53.4 (53.1 to 53.7) | 240 | 35.2 (31.8 to 38.9) | 3124 | 50.0 (48.8 to 51.3) |

| TC lifetime top 50% | 59 990 | 50.4 (50.1 to 50.6) | 223 | 32.8 (29.3 to 36.4) | 2636 | 42.2 (41.0 to 43.4) |

| NCI BCRAT lifetime top 50% | 59 809 | 50.2 (49.9 to 50.5) | 200 | 29.4 (26.1 to 32.9) | 2771 | 44.4 (43.1 to 45.6) |

| TC 5-year ≥1.67% | 48 969 | 41.1 (40.8 to 41.4) | 234 | 34.4 (30.9 to 38.0) | 3559 | 57.0 (55.8 to 58.2) |

| NCI BCRAT 5-year ≥1.67% | 47 795 | 40.1 (39.8 to 40.4) | 193 | 28.3 (25.1 to 31.8) | 3886 | 62.2 (61.0 to 63.4) |

| TC lifetime ≥20% | 11 047 | 9.3 (9.1 to 9.4) | 52 | 7.6 (5.9 to 9.9) | 5506 | 88.2 (87.3 to 88.9) |

| NCI BCRAT lifetime ≥20% | 4153 | 3.5 (3.4 to 3.6) | 27 | 4.0 (2.7 to 5.7) | 5992 | 95.9 (95.4 to 96.4) |

| Patients with valid scores by all risk modelsb | 92 522 | 322 | 4929 | |||

| Risk model scoresc | ||||||

| DL 5-year top 50% | 46 261 | 50.0 (49.7 to 50.3) | 234 | 72.7 (67.6 to 77.3) | 2089 | 42.4 (41.0 to 43.8) |

| TC 5-year top 50% | 46 665 | 50.4 (50.1 to 50.8) | 205 | 63.7 (58.3 to 68.7) | 2353 | 47.7 (46.4 to 49.1) |

| NCI BCRAT 5-year top 50% | 47 662 | 51.5 (51.2 to 51.8) | 192 | 59.6 (54.2 to 64.8) | 2577 | 52.3 (50.9 to 53.7) |

| TC lifetime top 50% | 46 841 | 50.6 (50.3 to 51.0) | 168 | 52.2 (46.7 to 57.6) | 2012 | 40.8 (39.5 to 42.2) |

| NCI BCRAT lifetime top 50% | 46 407 | 50.2 (49.8 to 50.5) | 161 | 50.0 (44.6 to 55.4) | 2112 | 42.9 (41.5 to 44.2) |

| TC 5-year ≥1.67% | 44 595 | 48.2 (47.9 to 48.5) | 199 | 61.8 (56.4 to 66.9) | 2447 | 49.6 (48.3 to 51.0) |

| NCI BCRAT 5-year ≥1.67% | 47 662 | 51.5 (51.2 to 51.8) | 192 | 59.6 (54.2 to 64.8) | 2577 | 52.3 (50.9 to 53.7) |

| TC lifetime ≥20% | 10 034 | 10.8 (10.7 to 11.1) | 46 | 14.3 (10.9 to 18.5) | 4242 | 86.1 (85.1 to 87.0) |

| NCI BCRAT lifetime ≥20% | 4007 | 4.3 (4.2 to 4.5) | 25 | 7.8 (5.3 to 11.2) | 4684 | 95.0 (94.4 to 95.6) |

The 5-year risk thresholds for a patient to be placed in the top half of patients at risk for breast cancer: DL score ≥ 2.17%, TC 5-year score ≥ 1.45%, NCI BCRAT 5-year score ≥ 1.40%, TC lifetime score ≥ 7.90%, and NCI BCRAT lifetime score ≥ 7.80%. CI = confidence interval; DL = deep learning; NCI BCRAT = National Cancer Institute Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool; TC = Tyrer-Cuzick.

Patients excluded based on lacking a valid risk score by TC or NCI BCRAT models (eg, those with a personal history of breast cancer or lobular carcinoma in situ, known genetic mutation for breast cancer, prior radiation therapy, and age restrictions of TC and NCI BCRAT models).

The 5-year risk thresholds for patients with valid scores by all risk models to be placed in the top half of patients at risk for breast cancer: DL score ≥ 2.05%, TC 5-year score ≥ 1.65%, NCI BCRAT 5-year score ≥ 1.70%, TC lifetime score ≥ 9.20%, and NCI BCRAT lifetime score ≥ 9.1%.

Figure 2.

Percent of cancers detected in population by percent invited to screen for breast cancer risk models for (A) all exams and (B) exams with valid scores from all 5 risk models. DL = deep learning; NCI BCRAT = National Cancer Institute Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool; TC = Tyrer-Cuzick.

Screening Based on Deep Learning vs Traditional Models in White vs Races Other Than White

We compared percent of patients invited to screen and percent of cancers captured in the subset of patients who self-reported race and ethnicity and had all risk model scores recorded. There was no evidence of differences in percent cancers captured using our deep learning model, with 73.5% (95% CI = 68.0% to 78.4%) of cancers in White patients vs 70.5% (95% CI = 55.8% to 81.8%) of cancers in races other than White captured when screening the top 50th percentile of patients by the deep learning score. In contrast, Tyrer-Cuzick and NCI BCRAT models captured statistically significantly fewer cancers in patients of races other than White compared with those captured in White patients (38.6%, 95% CI = 25.7% to 53.4%, vs 67.7%, 95% CI = 61.9% to 72.9%, and 40.9%, 95% CI = 27.7% to 55.6%, vs 62.5%, 95% CI = 56.6% to 68.0%, respectively; P < .001) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Outcomes based on simulated priority screening of patients in race and ethnicity subgroups by deep learning and traditional risk modelsa

| Patients self-reporting race and ethnicity | Invited to screening |

Cancers detected |

False positives avoided |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) | No. | % (95% CI) | |

| White | 74 934 | 272 | 4007 | |||

| Risk models | ||||||

| DL 5-year top 50% | 37 925 | 50.6 (50.3 to 51.0) | 200 | 73.5 (68.0 to 78.4) | 1657 | 41.3 (39.8 to 42.9) |

| TC 5-year top 50% | 40 897 | 54.6 (54.2 to 54.9) | 184 | 67.7 (61.9 to 72.9) | 1751 | 43.7 (42.2 to 45.2) |

| NCI BCRAT 5-year top 50% | 42 571 | 56.8 (56.5 to 57.2) | 170 | 62.5 (56.6 to 68.0) | 1893 | 47.2 (45.7 to 48.8) |

| Race other than White | 15 841 | 44 | 829 | |||

| Risk models | ||||||

| DL 5-year top 50% | 7464 | 47.1 (46.3 to 47.9) | 31 | 70.5 (55.8 to 81.8) | 398 | 48.0 (44.6 to 51.4) |

| TC 5-year top 50% | 4998 | 31.6 (30.8 to 32.3) | 17 | 38.6 (25.7 to 53.4) | 554 | 66.8 (63.6 to 70.0) |

| NCI BCRAT 5-year top 50% | 4329 | 27.3 (26.6 to 28.0) | 18 | 40.9 (27.7 to 55.6) | 629 | 75.9 (72.9 to 78.7) |

CI = confidence interval; DL = deep learning; NCI BCRAT = National Cancer Institute Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool; TC = Tyrer-Cuzick.

Discussion

This study compared performance of a deep learning breast cancer risk model to traditional risk models and found, in the clinical setting of individuals due for screening, the deep learning score derived from the patient’s prior mammogram outperformed all traditional risk models in identifying the subgroup of individuals with higher cancer burden. Percent of cancers captured when inviting to screen individuals in the top 50th percentile of risk was highest with deep learning models across race and ethnicity. The lowest cancer capture was associated with traditional risk models, whose use favored cancer capture in White patients.

The intended specific application of a risk model, and specific population targeted for its use, may impact model performance. For example, organizations such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend annual magnetic resonance imaging screening for patients with at least a 20% lifetime risk and consideration of chemoprevention for patients with at least a 1.67% 5-year risk (24). Our findings support prior reports encouraging a shift from lifetime models toward 5-year models to support informed decision making in patients at risk for breast cancer (25). Our findings demonstrate that 5-year risk models are superior to lifetime risk models to identify subgroups of patients with higher prevalence of cancer in patients due for screening, and we found a deep learning model trained to estimate risk based on the prior mammogram alone outperforms traditional risk models in the specific setting of targeted outreach to individuals due for screening.

For the specific purpose of identifying subgroups of patients with higher cancer burden, and prioritizing screening of those at higher risk, the deep learning model offers many advantages. Only a prior mammogram is necessary, a clear advantage for imaging centers without risk factor data previously collected or electronic health systems capable of quickly utilizing these data for risk assessment. The deep learning risk approach is automated with results available immediately after the mammogram. For imaging centers that have not incorporated image-based deep learning risk assessment, rapid processing of prior stored mammograms could be completed in a short period of time. This would enable imaging centers to recruit patients at increased risk quickly and efficiently to return to screening and more safely postpone mammograms for those at lower risk.

Our work is a natural evolution of work to improve breast cancer risk models. Prior research has confirmed that adding breast density to traditional risk models improves their predictive accuracy (11). The deep learning image-only model leverages the full spectrum of digital data from mammograms rather than density alone and, in doing so, statistically significantly improves performance. The radiologist and/or health-care provider can leverage this information to support more informed decision making for personalized screening programs (eg, frequency of screening, potential benefits of supplemental imaging) and more informed decisions regarding genetic testing.

The deep learning model does not incorporate other risk factors to assess an individual’s future risk of breast cancer. Rather, the model relies on the mammographic image alone to assign a risk score. Our prior research found adding traditional risk factors, such as age, hormone use, and prior breast biopsy, did not statistically significantly improve predictive accuracy (9,10). We hypothesize the image itself contains information associated with age, prior breast biopsy, and hormone use, and thus, the patient-reported information regarding these traditional risk factors is redundant. Studies are in progress to use methods such as heat maps to identify the mammogram’s specific features associated with future cancer risk.

Our study has limitations. Although the data were collected across 5 screening facilities, the facilities were within 1 large academic medical center in the United States, which was the center used for the risk model’s historic training to predict future breast cancer risk, and the patient population included a high proportion (82.5%) of White non-Hispanic patients. As with our prior validation of the deep learning model to predict risk, no mammograms used in training were included in the testing of the model in the current study; however, it is possible there was some overlap in patients included in the original training set and the current study. Our prior published work performed external validation of our deep learning risk model across 6 global institutions in the specific setting of predicting 5-year future breast cancer risk from a screening mammogram (9,10). We found robust performance in that application across diverse patient populations and importantly in patient populations outside of the population used to train the model. In this study, we compared the ability of our deep learning model, compared with traditional models, to identify patients with a higher cancer burden in a population due for screening. However, we have not performed external validation of the deep learning model in this specific application of identifying individuals with a higher cancer burden in a population due for screening. We also note only 2-dimensional mammograms were used in model development and testing. Future work may reveal higher accuracy with tomosynthesis images and/or synthetic 2-dimensional mammograms derived from tomosynthesis images. Further, future work will clarify if recommendations for risk-based, targeted, preferential screening of those at highest risk will lead to differential engagement or if other factors (eg, access, social determinants of engagement) will override risk-based screening recommendations.

Risk-based, rather than age-based, screening has clear advantages to increase the benefits of early cancer detection from screening programs while reducing the harms of false positives and unnecessary biopsies. And during the pandemic, government agencies and diverse health-care systems strongly encouraged risk-based mammographic screening (1,2). Effective risk-based screening has proven elusive partly because of the modest performance of traditional risk models and social determinants that drive screening engagement. In the era of artificial intelligence, we may leverage the power of deep learning and computer vision to provide more accurate and more equitable risk models and thus support more effective, equitable, higher value, and precise screening paradigms.

Funding

This research was supported in part by funds provided by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (Lehman, BCRF# 2019A004853).

Notes

Role of the funder: The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, preparation of the manuscript, or decision to submit it for publication.

Disclosures: CL Activities related to the present article: disclosed money to author’s institution for grants from Breast Cancer Research Foundation. Activities not related to the present article: disclosed money to author’s institution for grants from GE Healthcare and Hologic, Inc and is co-founder of Clairity, Inc. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. LL, RT, SM, TK, LE, MS: Nothing to disclose.

Author contributions: CL: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing. LL: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. SM: data curation, methodology of analysis, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. TK, LE, MS, and RT: writing—review and editing.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Constance D Lehman, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Harvard Medical School, Radiology, Boston, MA, USA.

Sarah Mercaldo, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Harvard Medical School, Radiology, Boston, MA, USA.

Leslie R Lamb, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Harvard Medical School, Radiology, Boston, MA, USA.

Tari A King, Harvard Medical School, Surgery, Boston, MA, USA; Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center, Boston, MA, USA.

Leif W Ellisen, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Harvard Medical School, Medicine, Boston, MA, USA.

Michelle Specht, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; Harvard Medical School, Surgery, Boston, MA, USA.

Rulla M Tamimi, Weill Cornell Medicine, Epidemiology and Population Health Sciences, New York, NY, USA.

Data Availability

Information regarding the deep learning model evaluated is available at https://learningtocure.csail.mit.edu, and the deep learning model is openly available upon request for research use. Data to compare performance of risk models were available through the Breast Imaging Data Repository Archive (BIDRA). Investigators interested in using the data can request access, and feasibility will be discussed at an investigators meeting and in accordance with Mass General Brigham institutional data sharing policies and procedures.

References

- 1. U.S. Health and Human Services website. Health and Human Services: re-opening approach. https://www.mass.gov/doc/eohhs-health-care-phase-1-reopening-approach-may-18-0/. Published May 2020. Accessed March 2022.

- 2. Dietz JR, Moran MS, Isakoff SJ, et al. Recommendations for prioritization, treatment, and triage of breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: the COVID-19 pandemic breast cancer consortium. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;181(3):487-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Society of Breast Imaging website. SBI recommendations for a thoughtful return to caring for patients. https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers.aspx?referenceid=2774635. Published July 9, 2020. Accessed July 28, 2022.

- 4. Minnier J, Rajeevan N, Gao L, et al. ; for the VA Million Veteran Program. Polygenic breast cancer risk for women veterans in the Million Veteran Program. J Clin Oncol Precision Oncology. 2021;5(5):1178-1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clift AK, Dodwell D, Lord S, et al. The current status of risk-stratified breast screening. Br J Cancer. 2022;126(4):533-550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Choudhury PP, Wilcox AN, Brook MN, et al. Comparative validation of breast cancer risk prediction models and projections for future risk stratification. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112(3):278-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Terry MB, Liao Y, Whittemore AS, et al. 10-year performance of four models of breast cancer risk: a validation study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(4):504-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Garcia-Closas M, Chatterjee N. Assessment of breast cancer risk: which tools to use? Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(4):463-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yala A, Mikhael PG, Strand F, et al. Toward robust mammography-based models for breast cancer risk. Sci Transl Med . 2021;13(578):eaba4373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yala A, Mikhael PG, Strand F, et al. Multi-institutional validation of a mammography-based breast cancer risk model [published online ahead of print November 12, 2021]. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(16):1732-1740. doi:10.1200/J Clin Oncol.21.01337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brentnall AR, Harkness EF, Astley SM, et al. Mammographic density adds accuracy to both the Tyrer-Cuzick and Gail breast cancer risk models in a prospective UK screening cohort. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17(1):147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Amir E, Freedman O. Underestimation of risk by Gail model extends beyond patients with atypical hyperplasia. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(9):1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jacobi CE, de Bock GH, Siegerink B, et al. Differences and similarities in breast cancer risk assessment models in clinical practice: which model to choose? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;115(2):381-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Quante AS, Whittemore AS, Shriver T, et al. Breast cancer risk assessment across the risk continuum: genetic and nongenetic risk factors contributing to differential model performance. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14(6):R144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gail MH, Costantino JP, Pee D, et al. Projecting individualized absolute invasive breast cancer risk in African American patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(23):1782-1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matsuno RK, Costantino JP, Ziegler RG, et al. Projecting individualized absolute invasive breast cancer risk in Asian and Pacific Islander American patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(12):951-961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Evans DG, Brentnall AR, Harvie M, et al. Breast cancer risk in a screening cohort of Asian and White British/Irish patients from Manchester UK. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yen AM, Tsau HS, Fann JC, et al. Population-based breast cancer screening with risk-based and universal mammography screening compared with clinical breast examination: a propensity score analysis of 1,429,890 Taiwanese patients. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(7):915-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Banegas MP, John EM, Slattery ML, et al. Projecting individualized absolute invasive breast cancer risk in US Hispanic patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(2):djw215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Valero MG, Zabor EC, Park A, et al. The Tyrer-Cuzick model inaccurately predicts invasive breast cancer risk in patients with LCIS. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(3):736-740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boughey JC, Hartmann LC, Anderson SS, et al. Evaluation of the Tyrer-Cuzick (International Breast Cancer Intervention Study) model for breast cancer risk prediction in patients with atypical hyperplasia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(22):3591-3596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MIT Learning to Cure. Machine learning for precise and equitable cancer Care.. http://learningtocure.csail.mit.edu/. Accessed March 2022.

- 23. Sickles EA, D’Orsi CJ, Bassett LW, et al. ACR BI-RADS® mammography. In: ACR BI-RADS® Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis (version 1.2021). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening.pdf. Published May 1, 2021. Accessed December 1, 2021.

- 25. MacInnis RJ, Knight JA, Chung WK, et al. ; for the kConFab Investigators. Comparing 5-year and lifetime risks of breast cancer using the prospective family study cohort. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(6):785-791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Information regarding the deep learning model evaluated is available at https://learningtocure.csail.mit.edu, and the deep learning model is openly available upon request for research use. Data to compare performance of risk models were available through the Breast Imaging Data Repository Archive (BIDRA). Investigators interested in using the data can request access, and feasibility will be discussed at an investigators meeting and in accordance with Mass General Brigham institutional data sharing policies and procedures.