Abstract

Functional identification of cancer stem-like cells (CSCs) is an established method to identify and study this cancer sub-population critical for cancer progression and metastasis. The method is based on the unique capability of single CSCs to survive and grow to tumorspheres in harsh suspension culture environment. Recent advances in microfluidic technology have enabled isolating and culturing thousands of single cells on a chip. However, tumorsphere assay takes a relatively long period of time, limiting the throughput of this assay. In this work, we incorporated machine learning with single-cell analysis to expedite tumorsphere assay. We collected 1,710 single-cell events as the database and trained a convolutional neural network model that predicts whether a single cell can grow to a tumorsphere on Day 14 based on its Day 4 image. With this future-telling model, we precisely estimated the sphere formation rate of SUM159 breast cancer cells to be 17.8% based on Day 4 images. The estimation was close to the ground truth of 17.6% on Day 14. The preliminary work demonstrates not only the feasibility to significantly accelerate tumorsphere assay but also a synergistic combination between single-cell analysis with machine learning, which can be applied to many other biomedical applications.

Keywords: Single-cell, Sphere Culture, Cancer Stem-like Cells, Machine Learning, Convolutional Neural Network

Introduction

Due to the genomic and epigenetic instability of cancer cells, tumor cells are notorious for inter-patient and intra-patient heterogeneity that confounds the fundamental understanding and treatment of cancer1–3. Researchers hypothesize key subsets of cells (e.g. tumor initiating cells (TICs)/cancer stem-like cells (CSCs)) are endowed the capability to seed and develop tumors in metastatic sites and relapse after treatment. In addition, the CSCs can be resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, so therapeutics targeting CSCs holds great promise to improve prognosis of patients4–7. However, tumor heterogeneity creates a formidable challenge to identify and target CSCs. While various markers of CSCs, including membrane proteins (e.g. CD24, CD44, CD90, and CD133), ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters (e.g. ABCG2), oncogenes (e.g. BMI1), enzymatic markers (e.g. aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) isoforms), and stem-cell related transcription factors (e.g. NOTCH, NANOG, octamer-binding transcription factor 4 (Oct-4), and sex determining region Y box 2 (SOX-2)) have been identified, different sets of markers were used to define CSCs in different types of cancers8–17. In addition, CSC markers may not have direct linkage to tumor-initiating and metastatic capability18,19. As an attractive alternative, functional isolation of CSCs using single-cell derived sphere formation was established20,21. The characteristic of cancer cells to grow in harsh suspension environment is correlated with their capability to survive in circulatory system and metastasize in a distant site. As such, single-cell suspension culture is a useful approach to identify CSCs for investigating this critical sub-population in tumor progression.

While single-cell suspension culture for CSC identification has been performed for more than one decade, there are two fundamental difficulties. One issue is how to guarantee sphere is indeed derived from a single cell rather than a cell aggregate. To date, the gold standard is to dilute small number of cells in low-attachment plate/dish for sphere formation. As the cells are sparse, they are less likely to aggregate. However, without physical isolation of single cells, they can accidentally get together by disturbance especially when exchanging media20–22. Thus, this experiment generally suffers from high variation, low reproducibility, and low throughput. The recent development of microfluidics has significantly mitigated this issue. Single cells can be isolated in micro-chambers, micro-wells, or droplet, excluding the event of undesired cell aggregation22–27. The use of 3D matrix (e.g. Matrigel) also represents another strategy to avoid cell aggregation28–29. The other issue of tumorsphere assay is that it runs through a relatively long period of time. As single cancer cells are less proliferative in suspension without support, it takes longer to grow spheres from single cells. There are different protocols for single-cell sphere formation, but it can take up to 14 days15–17, 22, 23, 29–30. Long-term experiment not only decreases the throughput of studies but also increases the risk of mishandling and cell contamination. In addition, hypoxia and cell death in the core of the formed spheres can generate new uncertainties in the long-term culture of spheres. Thus, a method to expedite tumorsphere assay can be very attractive.

There is a recent publication discussing the possibility to estimate final (Day 14) sphere counts using Day 1 images31. In that work, the authors characterized the sphere formation efficiency depending on the number of cells in aggregates. Then, they counted the number of single cells and cell aggregates 24 hours after cell loading for predicting the final sphere counts. While this is an interesting exploration, it does not answer which single cells can form spheres. More importantly, cell aggregates are excluded in microfluidic tumorsphere assays, so the presented method is less useful. The recent progress in machine learning provides new opportunities for biomedical applications32–38. One widely used deep learning method for image classification is convolutional neural network (CNN). CNN has one or more convolutional layers, which slide a filter over the input image to generate output for classification and regression. In our group, we have extracted morphological features from cellular contours and mitochondria for the prediction of cell migratory behaviors (direction and speed)39. Those previous works support the potential to predict tumorsphere formation based on morphological analysis augmented with machine learning.

In this work, we performed single-cell derived sphere formation experiment of SUM159 breast cancer cells using micro-well devices. The micro-wells containing tumor spheres were cropped for image analysis automatically, so we could collect cellular images in high throughput. With the large number of data, we developed and trained a CNN model to correlate the cellular images on Day 4 with their final size on Day 14. In this manner, we accurately estimated the sphere formation rate within 4 days as compared to conventional 14 days (3.5 times faster). The innovative approach significantly reduces the experiment time of tumorsphere assays and potentiate large-scale drug screening using tumorsphere model.

Materials and Methods:

Device design and fabrication

The micro-well device was composed of a single layer of PDMS (Polydimethlysiloxane, Sylgard 184, Dow Corning), which was fabricated on a silicon substrate by standard soft lithography. One device contained 10,000 micro-wells (200 μm diameter for each micro-well, making an array of 100 by 100 micro-wells). The SU-8 (Microchem) mold used for soft-lithography was created by a photolithography process with a 100 μm layer for micro-wells, following the protocol described in the previous work40. The pattern was designed using a computer aided design software (AutoCAD 2018, Autodesk®), and the mask was made by a Desktop Based Lithography μPG 101 tool (Heidelberg instruments). The SU-8 mold was treated by vaporized trichloro(3,3,3-trifluoropropyl)silane (452807 Aldrich) under vacuum for 2 hours to help the release of cured PDMS. PDMS was prepared by mixing with 10 elastomer: 1 curing agent (w/w) ratio, poured on the SU-8 mold, and cured at 100°C overnight before peeling. After peeling the PDMS device, it was then bonded to a 3 by 2-inch glass slide for easy handling using oxygen plasma (80W for 60 seconds). The device after bonding was heated at 80°C overnight to enhance bonding quality. The device was sterilized by UV radiation before experiment. Pluronic® F-108 (BASF, CAS 9003-11-6) solution (5% in DI water) was loaded to the device 12 hours before cell loading to create a non-adherent PDMS substrate.23,40 Device was then rinsed with PBS (Gibco 10010) for one hour to remove residual F-108 solution.

Cell culture

SUM159 mCherry (red fluorescent protein) cells were obtained from Dr. Gary Luker’s Lab (University of Michigan, MI, USA). We cultured SUM159 cells in F-12 (Gibco 11765) media supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco 10082), 1% Pen/Strep (Gibco 15070), 1% GlutaMAX (Gibco 35050), 1 μg/mL hydrocortisone (Sigma H4001), and 5 μg/mL insulin (Sigma I6634). All cells were cultured in regular polystyrene culture dishes and passaged at or before cells reached 80% confluency. We maintained all cells at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

Single-cell derived sphere experiment

SUM159 cancer cells were harvested from a petri-dish with 0.05% Trypsin/EDTA for 5 minutes, centrifuged at 100 × g for 5 minutes, and re-suspended at 1×106 cells/mL in regular SUM159 culture media. Then, 2,000 SUM159 cells were seeded and settled in 10,000 micro-wells within 5 minutes. After loading cancer cells, culture media was replaced with tumor sphere assay media as described in literature41. The tumor sphere media was based on DMEM/F12 (Gibco 11330–032) media and supplemented with 1% Glutamax (Gibco 35050–061), 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Gibco 15240), 1% N-2 Supplement (Gibco 17502–048), 20 ng/mL Recombinant Human EGF (R&D Systems 236-EG-01M), 20 ng/mL Recombinant Human FGF basic (R&D Systems 233-FB-025), 10 ng/mL Insulin (Sigma 11376497001), and 1μM Dexamethasone (Sigma D4902). Media was exchanged every other day. When exchanging media, we first took out all the residual media on the micro-well device and then added 3 mL of fresh sphere media. Cells were cultured for 14 days for sphere formation. The tumor sphere larger than 40 μm in diameter (Area is around 1256 μm2 or 3,000 pixel2) was scored as a sphere22, 42.

Image Acquisition

The micro-well devices were imaged initially after cell loading (Day 0) and on Day 2, Day 4, and Day 14 using an inverted microscope (Nikon TE2000). The brightfield and fluorescence images were taken with a 10x objective lens and a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Coolsnap HQ2, Photometrics). A mCherry filter set was used for the fluorescence imaging of mCherry fluorescent proteins. Brightfield imaging was performed using an exposure time shorter than 10 ms, and the fluorescence imaging was performed using an exposure time shorter than 1 s, minimizing the phototoxic effect on cells. The micro-well array was scanned with a motorized stage (ProScan II, Prior Scientific). Auto-focusing was performed to ensure the image remained in focus throughout the whole imaging area.

Image Processing

For image processing, we aimed to extract individual micro-wells for collecting tumor sphere images. The whole-device image was first rotated to make sure each column is aligned vertically. Then, the whole-device image was partitioned to smaller pieces, so each piece contained exactly one micro-well. To crop circular micro-wells containing cancer spheres, we applied a MATLAB program based on circular Hough transform, which could detect the circular object with defined radius. Since each micro-well had a circular edge with good contrast and fixed radius, the program could reliably detect the micro-well for cropping. After cropping the region of micro-well, we counted the number of cells in each micro-well initially (Day 0).The MATLAB cell counting program was implemented based on the observation that cell center was brighter than its periphery in fluorescence43. We first applied thresholding to the fluorescence images with several intervals and detected connect regions. Thus, we generated a region-adjacency graph representation of the cell image. Finally, a graph mining process searching for “simple-path” node chains was used to identify “local maximum” as cell centers to count the number of cells. The size of cells/spheres was determined by the number of pixels having fluorescence intensity higher than background noise. We processed the Day 0, Day 2, Day 4, and Day 14 images of the whole device, and the number of cells, cell center, and cell/sphere area of each micro-well were recorded. The micro-wells starting (Day 0) with no cell or more than one cell were excluded. The micro-wells capturing debris were also excluded.

Generation of Sphere Formation Database

In this study, we used fluorescence images of cells/spheres on Day 2 and Day 4 for predicting cell/sphere areas on Day 14. For each Day 2 and Day 4 image, we cropped a 61 by 61 pixels area containing cell/sphere for training and prediction. If only one cell was detected, we used the location of cell center as the center for cropping. If multiple cells were detected (e.g. one cell on Day 0 proliferated to multiple cells on Day 2 and Day 4.), we used the mean coordinates of cell centers as the center for cropping. Following common machine learning workflows, we randomly picked 80% of data for training a CNN model (training dataset) and used the other 20% for examining the accuracy of the trained model (independent testing dataset). In this work, we independently picked data for training and testing for 5 times to calculate technical variations. For data augmentation44, we translated (linearly moved) the images by three pixels to 8 directions (upper, upper right, right, lower right, lower, lower left, left, and upper left). We also flipped images both horizontally and vertically. In this manner, we generated 36 variations of a cell image to increase the database size by 36 times. As events of sphere formation were significantly less than the cases of no sphere formation in our database, we oversampled the sphere-forming events once in the training dataset.

Training of Neural Network

After image processing, we made the database for training a CNN network. In this study, we used the fluorescence image of cell/sphere on Day 2 or Day 4 as input predictor variable, and we aimed to correlate the image on Day 2 or Day 4 with its sphere area on Day 14. To minimize the bias caused by outliers, the spheres larger than 10,000 pixel2 were considered 10,000 pixel2, the spheres smaller than 100 pixel2 were considered 100 pixel2. The sphere area was processed by log10 to generate sphere area score (expected output) between 2 to 4. With the database, we used MATLAB 2019 deep learning toolbox to train a CNN model for the correlation between fluorescence image and sphere area score45. The sphere area score from direct observation was deemed correct and called “ground truth” for training and examining machine learning accuracy. Solver of stochastic gradient descent with momentum (SGDM) and data shuffling were used. When testing the accuracy of model, the 36 variations of a cell image were processed by the trained model independently to get 36 expected sphere area scores. The median of 36 expected sphere area scores was considered the final expected sphere area score of that cell.

Neural Network Structure

We designed a three-layer-set neural network structure for machine learning. Within each convolutional layer set, there are 4 different layers: a convolutional layer, a batch normalization layer, a rectifier function layer, and a max pooling layer. The first convolutional layer has 64 filters with the size of 12 by 12 pixels. The second convolutional layer has 32 filters with the size of 6 by 6 pixels. The third convolutional layer has 16 filters with the size of 4 by 4 pixels. The max pooling layer in each convolutional layer set gets the maximum of a 2 by 2 rectangle from the image with the stride size of 2. There is a dropout layer between the third convolutional layer set and the final fully connected layer. The dropout layer can reduce overfitting problem. For regression purpose, a regression layer is added after the fully connected layer. The network structure is illustrated as in Fig. S1.

Results and Discussion

Single-cell derived sphere formation in micro-wells

For single-cell derived sphere formation experiment, we used PDMS devices having micro-wells. The PDMS substrate was coated with F-108 to make it non-adherent, and SUM159 breast cancer cells were loaded into micro-wells. Following Poisson’s distribution, most single cells were isolated individually in micro-wells for tumorsphere assay (Fig. 1(a)). We imaged the micro-wells right after cell loading, counted the number of cells in each micro-well using a custom MATLAB program, and excluded the micro-wells isolating zero or more than one cell. In this manner, we successfully identified 1,710 micro-wells trapping exactly one cells. The cells were cultured in micro-wells for 14 days with sphere media, which could avoid cell adhesion to the substrate for suspension culture, and imaged on Day 2, Day 4, and Day 14. Using the location of micro-wells, we could track the same cells at different time points. After being cultured for 14 days, single cells could either die, be quiescent, or grow to spheres (Fig. 2). The areas of cells/spheres at all time points were measured by a custom MATLAB program, and the spheres larger than 3,000 pixel2 (a sphere with a diameter of 40 μm) on Day 14 were considered spheres. In this study, we got 301 spheres among 1,710 single cells (17.6%).

Figure 1. Early prediction of single-cell derived sphere formation using deep learning.

(a) Single SUM159 breast cancer cells were seeded in non-adherent micro-wells of an 8 by 8 array. Following Poisson’s distribution, 17 micro-wells isolated single cells. The cells were cultured in suspension for sphere formation assay. (scale bar: 200 μm) (b) The Day 2 and Day 4 images of cells in the micro-wells were used to predict the final size of cell/sphere on Day 14. Three layers of CNN filters were used for prediction.

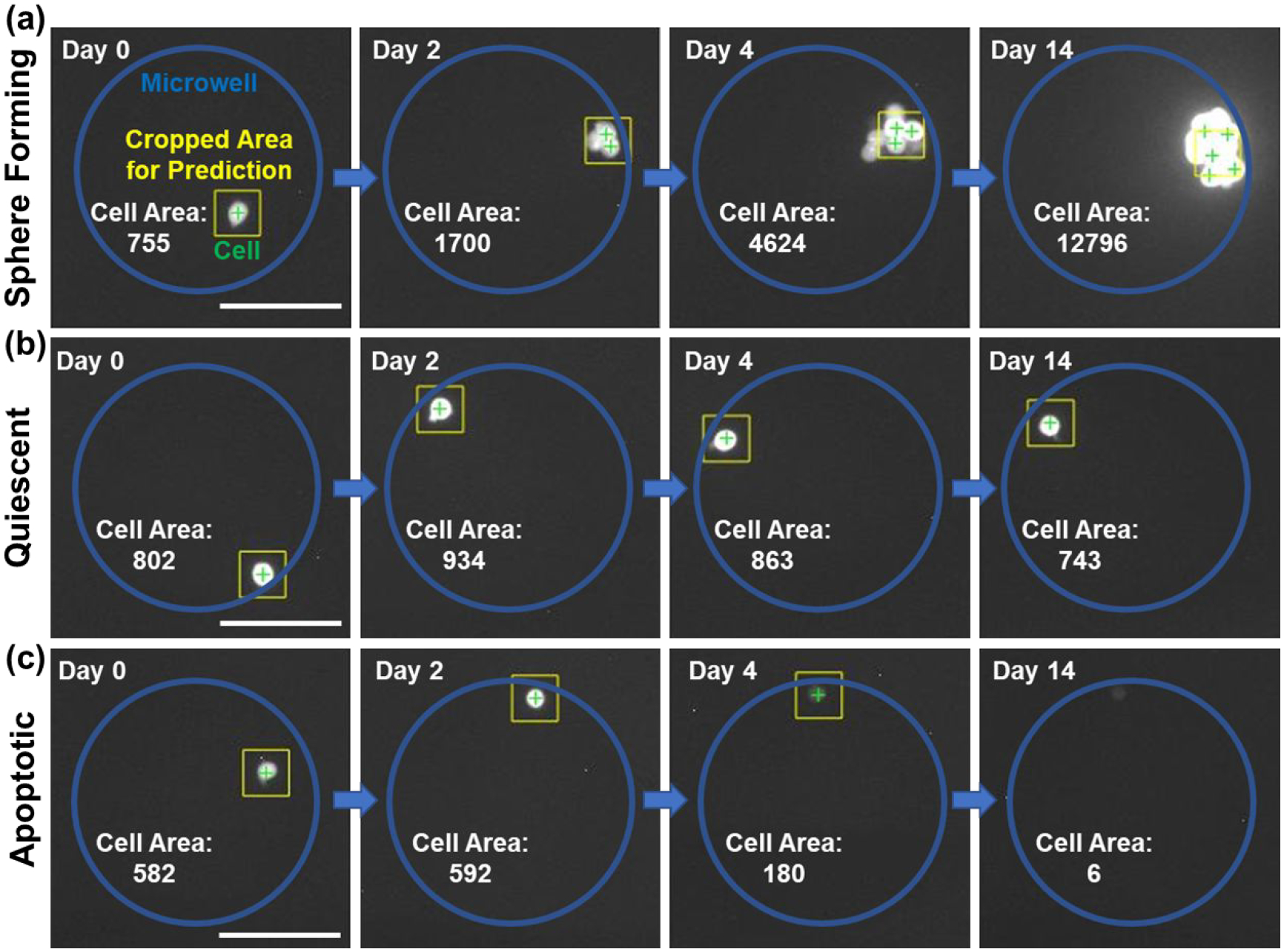

Figure 2. Representative cases of single cells cultured in non-adherent micro-wells.

The fluorescence images of Day 2 and Day 4 were used for prediction. Blue circle represents the boundary of micro-well, yellow square represents the cropped area for prediction, and green cross indicates the center of a cell. The unit of cell area is pixel2 (1 pixel2 is around 0.42 μm2). (scale bar: 100 μm) (a) Sphere-forming cell proliferated on Day 2 and Day 4, indicating good potential for sphere formation. (b) Quiescent cell maintained the cell area and brightness, but it failed to proliferate. (c) Apoptotic cell got significantly dimmer on Day 4 and died.

Distinct cellular morphology of sphere-forming cells on Day 2 and Day 4

Before trying to predict which cells would grow to spheres using CNN, we visualized cellular morphology on Day 2 and Day 4. While brightfield cellular morphology might carry some useful information, that could be interfered by the boundary of micro-well and debris/defects in the micro-well. Thus, we decided to rely on fluorescence image of the stably transfected mCherry SUM159 cell for prediction. As demonstrated in Fig. 2, we observed three different fates of single cancer cells. The sphere-forming cells typically proliferated before Day 4 and then further proliferated to form spheres on Day 14. Quiescent cells maintained single-cell status, and the fluorescence intensity and cell area were stable over time. Apoptotic cells got dimmer and disappeared in the micro-wells on Day 2 or Day 4. The notable differences in cellular morphology between sphere-forming and non-sphere-forming cells on Day 2 and Day 4 support the feasibility of early prediction.

Inaccurate prediction based on cell area on Day 2 and Day 4

Based on the observation in Fig. 2, we hypothesized that the cell area would be a critical feature determining the fate of cell. We calculated the correlation between cell area on Day 0, Day 2, and Day 4 with the final cell/sphere size on Day 14. As shown in Fig. 3(a), weak correlation was observed between cell/sphere size on Day 0 and that on Day 14 (Correlation coefficient R = 0.08). After culturing cells for 2 days or 4 days, some apoptotic cells died, and sphere forming cells grew. As expected, the correlation coefficients got high to 0.26 on Day 2, and 0.32 on Day 4 (Fig. 3(b, c)). However, the correlations were still weak. We examined the events in our database and found that proliferation rather than large area would be a better indicator of sphere formation. As shown in Fig. S2, while the case in Fig. S2(a) had smaller area than that in Fig. S2(b) on Day 2, the former case rather than the latter case formed sphere on Day 14. The observation highlights the limitation of prediction based on an individual morphological feature and suggests the need to apply comprehensive morphological analysis in this application.

Figure 3. The correlation between cell area on Day 0, 2, and 4 with the final cell/sphere area on Day 14.

The X-axis represents the cell area on (a) Day 0, (b) Day 2, and (c) Day 4, and the Y-axis represents the cell area on Day 14. Both axes are in logarithmic scale. Each blue dot represents a cell, and the red dash line represents the trend line. The correlation increases with time, but even the correlation on Day 4 is weak.

Prediction of sphere formation using a CNN model

After unsuccessful trial to predict sphere formation using an individual parameter of cell size, we applied a comprehensive CNN model for prediction. In CNN model, the network learned filters which could be critical features for prediction, and three convolutional layers were used as illustrated in Fig. S1. The method using unbiasedly extracted features by CNN did improve the correlation and prediction (Fig. 4). First, the correct prediction cases (prediction matched the ground truth) significantly outnumbered the wrong prediction cases (prediction did not match the ground truth) (Fig. 4(a, b)). In addition, we got much higher accuracy for non-sphere-forming cells (the first column in the confusion matrix) than sphere-forming cells (the second column). Overall, using Day 2 cellular fluorescence images, we correctly predicted whether a cell would form a sphere for 87.3% of events, and the correlation coefficient between predicted and real cell/sphere size on Day 14 is 0.62 (Fig. 4c). Using the cellular fluorescence images on Day 4, the accuracy got to 88.1%, and the correlation coefficient reached 0.81 (Fig. 4d). The significant improvement of accuracy suggests the value of deep learning model in prediction of sphere formation.

Figure 4. Prediction of sphere formation using cellular fluorescence images of Day 2 and Day 4 with a CNN model.

(a, b) The confusion matrices of prediction based on images of (a) Day 2 and (b) Day 4. The green boxes represent correct prediction, the red boxes represent wrong prediction, and the grey boxes represent summation of a row/column. Both number of prediction events and percentage are described in the box, ± represents the standard deviation from 5 independent sampling, model training, and testing experiments. The events in the first column did not form sphere, and the ones in the second column formed spheres (ground truth). The events in the first row were predicted (by the CNN model) to be non-sphere-forming, and the ones in the second row were predicted to be sphere-forming. (c, d) Prediction of cell/sphere size on Day 14 using images of (c) Day 2 and (d) Day 4 with the CNN model. X-axis represents the ground truth of cell/sphere size on Day 14, and Y-axis represents the predicted cell/sphere size on Day 14 using cellular image of Day 2 and Day 4 with the trained CNN model. Each dot represents a cell. The R-values of linear regression are 0.62 using Day 2 images and 0.81 using Day 4 images, indicating a strong correlation between the ground truth and prediction.

Visualization of critical morphology features in CNN filters

Given the poor interpretability of CNN filters46, we examined the CNN filters to better understand the key features distinguishing sphere-forming and non-sphere-forming cases (Fig. S3). A representative Day 4 fluorescence image (Fig. S3(d)) was processed by convolution layers for demonstration. Fig. S3(a–c) demonstrates the image processed by 64 filters in the first convolutional layer, 32 filters in the second convolutional layer, and 16 filters in the third convolutional layer, respectively. The processed images highlight the effects of filters as critical morphological features. In the first convolutional layer, we found the contrast of image was sharpened, and the outline of cells was enhanced. The effects suggest that the trained filters recognize cells as the critical object and outline of cells as the key feature for prediction. In addition, we found the strips/dots picking up the textures of cellular fluorescence image47. More interestingly, there are filters translated (linearly moved) from another filter, matching with the existence of translated images in our augmented database. While we cannot completely explain the meaning of filters, understandable morphological features exist in the filters. The filters in the second and the third convolutional layers show more abstract and high-order features, so it is even more difficult to interpret them (Fig. S3 (b, c)).

Estimation of sphere number rate using the CNN model

In addition to telling the fate of each individual cell, it is important to precisely estimate the final sphere formation rate as an indicator of the tumor-initiating capability. The major difficulty was that non-sphere-forming cells significantly outnumbered sphere-forming cells in the raw training database, so the CNN model was more likely to predict an ambiguous case to be a non-sphere-forming cell. The imbalance between false positive (a non-sphere-forming cell predicted to be sphere-forming) and false negative cases (a sphere-forming cell predicted to be non-sphere-forming) could under-estimate the sphere formation rate (Fig. 5(a)). To address this issue, we oversampled the sphere-forming cells to generate a more balanced training database48. In this manner, using Day 4 images, we accurately estimated the sphere formation rate to be 17.8%, which was close to the ground truth of 17.6% (Fig. 5(b)). However, using Day 2 images, the estimated sphere formation was 14.3%, which was significantly lower than the ground truth. After examining wrong prediction cases, we found that some sphere-forming cells did not proliferate on Day 2. Thus, there was no hint for the machine to tell it could form sphere. While we cannot make precise prediction using Day 2 images, the failure indirectly suggests the features used for prediction. The successful prediction using Day 4 images validates the feasibility to collect accurate sphere formation rate by performing short-term (4 days) tumorsphere assays rather than conventional long-term (14 days) experiments. The expedited experiment supported by machine learning can enhance the throughput and reduce the turnaround time of tumorsphere assay for identification of CSCs.

Figure 5. The ground truth and estimated sphere formation rates using cellular images on Day 2 and Day 4.

Error bar represents the standard deviation from 5 independent sampling, model training, and testing experiments. Student’s t-test was used for hypothesis testing. (a) Using raw training dataset having significantly more non-sphere-forming cells, the sphere formation rate is under-estimated using both Day 2 and Day 4 images. (b) Using balanced training dataset having comparable number of non-sphere-forming and sphere-forming cells, the estimation using Day 4 cellular images is close to the ground truth.

Conclusion

Tumorsphere assay is a well-established method to identify CSCs, yet it is limited by the difficulties of reliably isolating single cells and long experiment time. Microfluidics has significantly improved the capability to isolate single cells in high throughput, yet there was no effective method to shorten the experiment time of tumorsphere assay. In this work, we successfully integrated machine learning with single-cell analysis to expedite tumorsphere assay from 14 days to 4 days (3.5 times faster). Using high-throughput single-cell suspension culture capability, we collected 1,710 SUM159 single-cell events as our database. Among those single cells, 17.6% grew to spheres, while others were quiescent or died after 14 days. We first tried to use cell area on Day 0, Day 2, and Day 4 as a single parameter to predict whether a cell could grow to sphere on Day 14, yet the correlation was weak. The result suggests the limited prediction power of an individual morphological feature. As compared to that, using a comprehensive CNN model for prediction, we got a high accuracy of 87.3% with Day 2 images and 88.1% with Day 4 images to tell whether a cell could form a sphere on Day 14. More importantly, using Day 4 images, we accurately estimated the sphere formation rate to be 17.8%, which was close to the ground truth of 17.6% on Day 14. In this exploration, we found that single-cell approach naturally generates a large amount of data, which is well-suited for analysis augmented with machine learning. While we only demonstrated the prediction using one breast cancer cell line in this work, we will use the developed single-cell derived sphere formation and computation method for testing more cancer cells in the future. The combination of single-cell analysis and machine learning will create strong synergistic effects to expedite bio-discovery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from National Institute of Health to E.Y. (R01 CA 203810). Y.-C. Chen acknowledges the support from Forbes Institute for Cancer Discovery. We thank the Lurie Nanofabrication Facility of the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI) for device fabrication.

Supporting information

Supporting information includes the structure of neural network, examples of single cells cultured in micro-wells on Day 2, and trained neural network filters for prediction.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Dagogo-Jack I; Shaw AT Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018, 15 (2), 81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frank NY; Schatton T; Frank MH The therapeutic promise of the cancer stem cell concept. J. Clin. Invest 2010, 120, 41–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kreso A; Dick JE Evolution of the cancer stem cell model. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 275–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks MD; Burness ML; Wicha MS Therapeutic implications of cellular heterogeneity and plasticity in breast cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 17, 260–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prieto-Vila M; Takahashi R; Usuba W; Kohama I; and Ochiya T Drug Resistance Driven by Cancer Stem Cells and Their Niche. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18 (12), 2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phi LTH; Sari IN; Yang YG; Lee SH; Jun N; Kim KS; Lee YK; Kwon HY Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) in Drug Resistance and their Therapeutic Implications in Cancer Treatment. Stem Cells Int 2018, 2018, 5416923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bodgi L; Bahmad HF; Araji T; Al Choboq J; Bou-Gharios J; Cheaito K; Zeidan YH; Eid T; Geara F; Abou-Kheir W Assessing Radiosensitivity of Bladder Cancer in vitro: A 2D vs. 3D Approach. Front Oncol 2019, 9, 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karsten U; Goletz S What makes cancer stem cell markers different? Springerplus 2013, 2 (1), 301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomita H; Tanaka K; Tanaka T; Hara A Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 in stem cells and cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7 (10), 11018–11032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takebe N; Miele L; Harris PJ; Jeong W; Bando H; Kahn M; Yang SX; Ivy SP Notch, Hedgehog, and Wnt pathways in cancer stem cells: clinical update. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2015, 12 (8), 445–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeter CR; Yang T; Wang J; Chao HP; Tang DG Concise Review: NANOG in Cancer Stem Cells and Tumor Development: An Update and Outstanding Questions. Stem Cells 2015, 33 (8), 2381–2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang D; Lu P; Zhang H Oct-4 and Nanog promote the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of breast cancer stem cells and are associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer patients. Oncotarget 2014, 5 (21), 10803–10815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W; Ma H; Zhang J; Zhu L; Wang C; Yang Y Unraveling the roles of CD44/CD24 and ALDH1 as cancer stem cell markers in tumorigenesis and metastasis. Sci Rep 2017, 7 (1), 13856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim WT; Ryu CJ Cancer stem cell surface markers on normal stem cells. BMB Rep 2017, 50 (6), 285–298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bahmad HF; Poppiti RJ Medulloblastoma cancer stem cells: molecular signatures and therapeutic targets. J Clin Pathol 2020, 73 (5), 243–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bahmad HF; Chamaa F; Assi S; Chalhoub RM; Abou-Antoun T; Abou-Kheir W Cancer Stem Cells in Neuroblastoma: Expanding the Therapeutic Frontier. Front Mol Neurosci 2019, 12, 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bahmad HF; Mouhieddine TH; Chalhoub RM; Assi S; Araji T; Chamaa F; Itani MM; Nokkari A; Kobeissy F; Daoud G; Abou-Kheir W The Akt/mTOR pathway in cancer stem/progenitor cells is a potential therapeutic target for glioblastoma and neuroblastoma. Oncotarget 2018, 9 (71), 33549–33561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muraro MG; Mele V; Däster S; Han J; Heberer M; Cesare Spagnoli G; Iezzi G CD133+, CD166+CD44+, and CD24+CD44+ Phenotypes Fail to Reliably Identify Cell Populations with Cancer Stem Cell Functional Features in Established Human Colorectal Cancer Cell Lines. Stem Cells Transl. Med 2012, 1, 592–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y; Nenutil R; Appleyard MV; Murray K; Boylan M; Thompson AM; Coates PJ Lack of correlation of stem cell markers in breast cancer stem cells. Br J Cancer 2014, 110 (8), 2063–2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dontu G; Abdallah WM; Foley JM; Jackson KW; Clarke MF; Kawamura MJ; Wicha MS In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev 2003, 17 (10), 1253–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu S; Dontu G; Mantle ID; Patel S; Ahn NS; Jackson KW; Suri P; Wicha MS Hedgehog signaling and Bmi-1 regulate self-renewal of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells. Cancer Res 2006, 66 (12), 6063–6071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen YC; Ingram PN; Fouladdel S; McDermott SP; Azizi E; Wicha MS; Yoon E High-Throughput Single-Cell Derived Sphere Formation for Cancer Stem-Like Cell Identification and Analysis. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 27301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng YH; Chen YC; Brien R; Yoon E Scaling and automation of a high-throughput single-cell-derived tumor sphere assay chip. Lab Chip 2016, 16 (19), 3708–3717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brouzes E Droplet microfluidics for single-cell analysis. Methods Mol Biol 2012, 853, 105–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rettig JR; Folch A Large-scale single-cell trapping and imaging using microwell arrays. Anal Chem 2005, 77 (17), 5628–5634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pang L; Ding J; Ge Y; Fan J; Fan S-K Single-Cell-Derived Tumor-Sphere Formation and Drug-Resistance Assay Using an Integrated Microfluidics. Anal Chem 2019, 91 (13), 8318–8325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen YC; Jung S; Zhang Z; Wicha MS; Yoon E Co-culture of functionally enriched cancer stem-like cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts for single-cell whole transcriptome analysis. Integr Biol (Camb) 2019, 11 (9), 353–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rybak AP; He L; Kapoor A; Cutz JC; Tang D Characterization of sphere-propagating cells with stem-like properties from DU145 prostate cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011, 1813 (5), 683–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bahmad HF; Cheaito K; Chalhoub RM; Hadadeh O; Monzer A; Ballout F; El-Hajj A; Mukherji D; Liu YN; Daoud G; Abou-Kheir W Sphere-Formation Assay: Three-Dimensional in vitro Culturing of Prostate Cancer Stem/Progenitor Sphere-Forming Cells. Front Oncol 2018, 8, 347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee CH; Yu CC; Wang BY; Chang WW Tumorsphere as an effective in vitro platform for screening anti-cancer stem cell drugs. Oncotarget 2016, 7 (2), 1215–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bailey PC; Lee RM; Vitolo MI; Pratt SJP; Ory E; Chakrabarti K; Lee CJ; Thompson KN; Martin SS Single-Cell Tracking of Breast Cancer Cells Enables Prediction of Sphere Formation from Early Cell Divisions. iScience 2018, 8, 29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen CL; Mahjoubfar A; Tai L-C; Blaby IK; Huang A; Niazi KR; Jalali B Deep Learning in Label-free Cell Classification. Sci. Rep 2016, 6, 21471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manak MS; Varsanik JS; Hogan BJ; Whitfield MJ; Su WR; Joshi N; Steinke N; Min A; Berger D; Saphirstein RJ; Dixit G; Meyyappan T; Chu H-M; Knopf KB; Albala DM; Sant GR; Chander AC Live-cell Phenotypic-biomarker Microfluidic Assay for the Risk Stratification of Cancer Patients via Machine Learning. Nat. Biomed. Eng 2018, 2 (10), 761–772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eulenberg P; Köhler N; Blasi T; Filby A; Carpenter AE; Rees P; Theis FJ; Wolf FA Reconstructing Cell Cycle and Disease Progression Using Deep Learning. Nat. Commun 2017, 8 (1), 463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blasi T; Hennig H; Summers HD; Theis FJ; Cerveira J; Patterson JO; Davies D; Filby A; Carpenter AE; Rees P Label-free Cell Cycle Analysis for High-Throughput Imaging Flow Cytometry. Nat. Commun 2016, 7 (1), 10256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pärnamaa T; Parts L Accuracy Classification of Protein Subcellular Localization from High-Throughput Microscopy Images Using Deep Learning. G3 (Bethesda) 2017, 7 (5), 1385–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Christiansen EM; Yang SJ; Ando DM; Javaherian A; Skibinski G; Lipnick S; Mount E; O’Neil A; Shah K; Lee AK; Goyal P; Fedus W; Poplin R; Esteva A; Berndl M; Rubin LL; Nelson P; Finkbeiner S In Silico Labeling: Predicting Fluorescent Labels in Unlabeled Images. Cell 2018, 173 (3), 792–803.e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang N; Liu R; Asmare N; Chu C-H; Sarioglu AF Processing code-multiplexed Coulter signals via deep convolutional neural networks. Lab Chip 2019, 19, 3292–3304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Z, Chen L, Humphries B, Brien R, Wicha MS, Luker KE, Luker GD, Chen YC and Yoon E, Morphology-based prediction of cancer cell migration using an artificial neural network and a random decision forest. Integr Biol (Camb) 2018, 10 (12), 758–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Z; Chen YC; Urs S; Chen L; Simeone DM; Yoon E Scalable Multiplexed Drug-Combination Screening Platforms Using 3D Microtumor Model for Precision Medicine. Small 2018, 14 (42), 1703617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adams A; Warner K; Pearson AT; Zhang Z; Kim HS; Mochizuki D; Basura G; Helman J; Mantesso A; Castilho RM; Wicha MS; Nör JE ALDH/CD44 identifies uniquely tumorigenic cancer stem cells in salivary gland mucoepidermoid carcinomas. Oncotarget 2015, 6 (29), 26633–26650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sart S; Tomasi RF; Amselem G; Baroud CN Multiscale cytometry and regulation of 3D cell cultures on a chip. Nat Commun 2017, 8 (1), 469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Faustino GM; Gattass M; Rehen S; de Lucena CJ Automatic embryonic stem cells detection and counting method in fluorescence microscopy images. in Proc. IEEE Int. Symp. Biomed. Imag, From Nano to Macro 2009, 799–802. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shorten C; Khoshgoftaar TM A Survey of Image Data Augmentation for Deep Learning. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Z; Chen L; Wang Y; Zhang T; Chen Y-C; Yoon E Label-Free Estimation of Therapeutic Efficacy on 3D Cancer Spheres Using Convolutional Neural Network Image Analysis. Anal Chem 2019, 91 (21), 14093–14100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Q-S; Zhu S-C Visual Interpretability for Deep Learning: a Survey. Frontiers of Information Technology & Electronic Engineering 2018, 19 (1), 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu L; Chen J; Fieguth P; Zhao G; Chellappa R; Pietikäinen M From BoW to CNN: Two Decades of Texture Representation for Texture Classification. International Journal of Computer Vision 2018, 127 (1), 74–109. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wei Q; Dunbrack RL Jr. The role of balanced training and testing data sets for binary classifiers in bioinformatics. PLoS One 2013, 8 (7), e67863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.