Abstract

Background: Public awareness about speech-language pathology (SLP) and audiology professions in Jordan is currently unclear.

Methods: A total of 2640 participants took part in this cross-sectional study. A questionnaire was shared and posted on social media (Twitter, Facebook, and WhatsApp). The questionnaire consisted of three parts: demographics, experience with communication and hearing disorders, and SLP and audiology knowledge.

Aim: To investigate public awareness of SLP and audiology professions in Jordan.

Results: Most participants (69.3%) were residents of major Jordanian cities (Amman, Irbid, and Al-Zarqa). Moreover, about a third of participants (32.8%) were employees in health fields. Most participants (70%) reported that the main area of working for speech pathologists (SLPs) and audiologists is private clinics; about 80% indicated audiologists diagnose the severity of hearing loss, and SLPs improve persons’ speech. Participants working in health fields were more aware than participants working in other areas (P < 0.05)

Conclusion: Findings indicated that the levels of public awareness of different aspects of SLP and audiology professions in Jordan are not high. Thus, there is a need to raise public awareness of speech-language pathology and audiology professions through various available ways.

Keywords: Communication Disorders, Dysphagia, Hearing Loss, Voice.

Résumé

Contexte : La sensibilisation du public aux professions d'orthophoniste et d'audiologiste en Jordanie est actuellement inconnue.

Objectif : Enquêter sur la sensibilisation du public aux professions d'orthophoniste et d'audiologiste en Jordanie.

Méthodes : Au total, 2640 participants ont pris part à cette étude transversale. Un questionnaire a été partagé et publié sur les réseaux sociaux (Twitter, Facebook et WhatsApp). Le questionnaire comportait trois parties : données démographiques, expérience des troubles de la communication et de l'audition, et connaissances en orthophonie et en audiologie.

Résultats : La plupart des participants (69,3 %) étaient des résidents des principales villes jordaniennes (Amman, Irbid et Al-Zarqa). De plus, environ le tiers des participants (32,8 %) étaient des employés dans les domaines de la santé. La plupart des participants (70 %) ont déclaré que le principal domaine de travail des orthophonistes et des audiologistes est les cliniques privées. environ 80 % ont indiqué que les audiologistes diagnostiquent la gravité de la perte auditive et que les orthophonistes améliorent la parole des personnes. Les participants travaillant dans les domaines de la santé étaient plus conscients que les participants travaillant dans d'autres domaines (P < 0,05).

Conclusion : Les résultats ont indiqué que les niveaux de sensibilisation du public aux différents aspects des professions d'orthophoniste et d'audiologiste en Jordanie ne sont pas élevés. Ainsi, il est nécessaire de sensibiliser le public aux professions d'orthophoniste et d'audiologiste par divers moyens disponibles.

Mots Clés: Dysphagie, Perte auditive, Troubles de la communication, Voix.

Introduction

The communication process indicates a series of steps taken to communicate successfully (1 ). It involves exchanging ideas, information, needs and desires between individuals (1, 2). Moreover, communication process includes encoding the message by the sender, transmitting the message, and decoding the message by the receiver ( 3, 4). People communicate with one another in several ways such as speech, hearing, writing, reading and signing or other manual means (4, 5, 6).

The American Speech and Hearing Association (ASHA) defines a communication disorder as an impairment or decline in the ability to send, receive, process, and comprehend concepts or verbal or nonverbal and graphic symbol systems. Hearing, language, and/or speech difficulties can be signs of a communication disorder (7 ). Moreover, the severity of a communication disorder may

range from mild to profound (7, 8). It may be developmental or acquired ( 7, 8, 9, 10 ). The speech- language pathology (SLP) or communication sciences and disorders (CSD) is the science concerned with studying human communication and its disorders or impairments ( 1, 8 ). It is concerned with assessing and treating speech-language, cognitive-communication, and swallowing disorders that result in communication disabilities (1, 8, 9, 10 ). The specialist who evaluates and treats these disorders or impairments is called a speech-language pathologist (7 ).

Additionally, ASHA defines audiology is the science of hearing, balance, and related disorders

(11 ). The audiologist is a healthcare professional who provides patient-centered care in the prevention, identification, diagnosis, and treatment of hearing, balance, and other auditory impairments for individuals of all ages (12, 13 ).

Globally, a number of studies have performed on the public awareness of SLP and audiology (14, 15, 16, 17, 18 ). Two studies aimed to investigate public understanding and knowledge of SLP indicated that public awareness of SLP was limited (14, 15 ). In contrast, a study that was conducted in Saudi Arabia showed reasonable public awareness of SLP and audiology (16 ). Moreover, a study that was performed in Malaysia reported that public awareness of communication disorders and speech-language therapy differed based on age, education level, and occupation (17 ). Notably, people with higher levels of education and health professionals tended to have a greater awareness of communication disorders and speech-language therapy. Another study was performed in Jordan about dentists' awareness and knowledge of normal speech-language development and speech-language disorders, and to assess their general attitudes toward speech- language pathology (18 ). The participants showed limited awareness of normal speech-language development and speech-language disorders. However, most participants reported a general impression that speech-language pathologist (SLPs) have a significant role in a health profession team.

To June 27, 2022, insufficient information about the Jordanian community's awareness and knowledge of SLP and audiology professions is available. Therefore, there is a need to investigate public awareness of SLP and audiology professions in Jordan.

This study aimed to (i) investigate public awareness of SLP and audiology professions in Jordan Compare public awareness of SLP and audiology professions based on demographic variables.

Methods

Study design and participants

This cross-sectional, descriptive study was designed to investigate the public awareness of SLP and audiology professionals in Jordan using a questionnaire. This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Jordanian Ministry of Health (approval code: MOH20211297).

The questionnaire was prepared electronically on a Google Form to reach people all over Jordan. In addition, the link to the questionnaire was posted on and shared on social media (Twitter, Facebook, and WhatsApp) of the authors. A total of 2640 participants took part in this study that was performed between December 22, 2021 and May 3, 2022. The inclusion criteria involved all individuals who lived in Jordan and who aged ≥ 18 years old at the time of completing the questionnaire. An electronic informed consent was also obtained in the full-scale study.

Sample size

The sample size was estimated by single proportion formula:

n=(z/∆)2(P(1 − P)

=(1.96/.02) 2(0.4(1 − 0.4)

n = 2305

n = sample size.

z = the value to estimate the 95% confidence interval (1.96).

P = the population proportion.

∆ = detectable difference of expected proportion from true population proportion (precision or effect size).

Additionally, we assumed the drop-out rate would be 20%, so the total sample size became 2766. Our hypothesis was public awareness of SLP and audiology professions is limited, and individuals working in health fields are more aware than others.

Questionnaire

The information was gathered using a questionnaire created in English and validated into Arabic by Alanazi & Al Fraih (16 ). The face validity and internal consistency of the questionnaire was established. Cronbach’s α score was calculated and Principal Components Analysis (PCA) was performed for validation of the questionnaire. A Cronbach’s α score of 0.71 was gotten, KMO and Bartlett’s test yielded results depicting that variables are significantly correlated on PCA. This questionnaire has 22 questions distributed into three sections: demographics, experience with communication and hearing disorders, and knowledge of speech-language pathology and audiology.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS statistics software was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were performed to examine the distribution of responses. Moreover, the Chi-square test was used to measure the

association between participants’ characteristics which included (age, sex, region, level of education, type of occupation, monthly family income and whether the participants have children or not) and their awareness of SLP and audiology professions.

Results

Characteristics of the participants

A total of 2640 individuals participated in this study. Over half of the study participants were female (56.5%). Most of participants lived in major Jordanian cities (Amman, Irbid and Al- Zarqa). In addition, 67.9% of participants reported that they have children (Table 1 ).

Table 1. Table 1. Participants’ characteristics (n=2640).

|

Variable |

Category |

Number |

% |

|

Sex |

Male |

1148 |

43.5 |

|

Female |

1492 |

56.5 |

|

|

Age |

18-30 |

490 |

18.6 |

|

31-40 |

584 |

22.1 |

|

|

41-50 |

908 |

34.4 |

|

|

51-60 |

374 |

14.2 |

|

|

61-70 |

188 |

7.1 |

|

|

Above 71 |

96 |

3.6 |

|

|

Region |

Amman |

845 |

32.0 |

|

Irbid |

516 |

19.5 |

|

|

Al-Zarqa |

470 |

17.8 |

|

|

Al-Balqa |

142 |

5.4 |

|

|

Jerash |

105 |

4 |

|

|

Ajloun |

134 |

5.1 |

|

|

Al-Mafraq |

68 |

2.6 |

|

|

Madaba |

58 |

2.2 |

|

|

Al-Karaq |

78 |

3 |

|

|

Al-Tafila |

70 |

2.6 |

|

|

Ma’an |

56 |

2.1 |

|

|

AL-Aqaba |

98 |

3.7 |

|

|

Have Children |

Yes |

1792 |

67.9 |

|

No |

848 |

32.1 |

|

|

Qualification |

Less than High School Certificate |

266 |

10.1 |

|

High School Certificate |

412 |

15.6 |

|

|

Diploma |

356 |

13.5 |

|

|

Bachelor’s degree |

1270 |

48.1 |

|

|

Graduate degree |

336 |

12.7 |

|

|

Type of occupation |

Health fields |

866 |

32.8 |

|

Other |

1774 |

67.2 |

|

|

Monthly family income (JOD) |

500 or less |

456 |

17.3 |

|

501-1000 |

1136 |

43.0 |

|

|

1001-1500 |

636 |

24.1 |

|

|

1501-2000 |

312 |

11.8 |

|

|

Above 2000 |

100 |

3.8 |

Experience with communication and hearing disorders

Of the total, 87.9% of participants reported that they have never personally visited or had one of their family members saw a speech-language pathologist or an audiologist. Of those who had, 7.6% visited audiologists, 2.5% visited SLPs, whereas 2% of participants visited both specialists.

The majority of participants (96.5 %) have never been evaluated with a communication disorder or hearing loss. Sixty-four participants (2.4%) were diagnosed with hearing loss, 42 participants (1.6%) were diagnosed with communication disorders, and 14 participants (0.5%) were diagnosed with both.

Less than a third of the participants (29.2%) knew someone with hearing loss, 13% of participants knew someone with communication disorders, and 4.2% of participants knew someone with both. Among those who knew, 40.3% had first-degree relatives with communication disorders or hearing diseases, 31.9% had second-degree relatives, 18.8% had third-degree relatives, and 9% had friends or neighbors.

More than half of participants (59.5%) have not seen, heard, or read anything about communication disorders or hearing diseases. Among those who had, 50.4% encountered information for both communication disorders and hearing diseases, 27.9% for hearing diseases only and 21.6% for communication disorders only.

Awareness of speech-language pathology and audiology

Regarding the kind of workplaces for speech-language pathologists and audiologists, most participants (74.6%) believed that private clinics being the main workplace for both specialists. In comparison, the least responses (10.1%) were universities (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 . Figure 1. The distribution of potential workplaces for speech-languagepathologists (SLPs) and audiologists in Jordan indicated by participants(n=2640). Note: the participants were able to choose more than one answer.

Regarding the need for a referral to see an SLP or audiologist, most participants (n=1388; 52.6%) reported that no referral is needed to visit a speech-language pathologist or audiologist

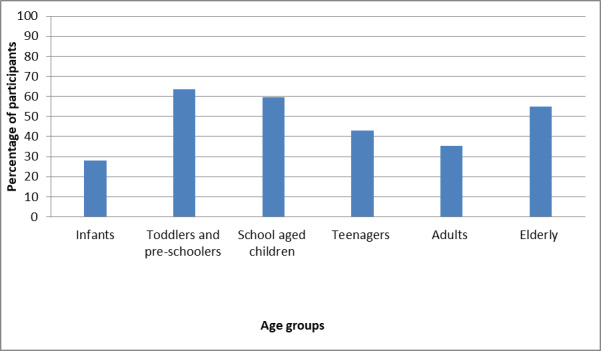

while 770 participants (29.2%) indicated that a referral is needed to see an SLP or audiologist. The remaining participants (n=482; 18.2%) did not know if a referral is required to see an SLP or audiologist. Regarding the age groups SLPs and audiologists work with, only 16.7% of responses correctly reported working with all age groups (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2 . Figure 2. The distribution of the age groups that speech-languagepathologists (SLPs) and audiologists worked with indicated by participants(n=2640). Note: the participants were able to choose more than one answer.

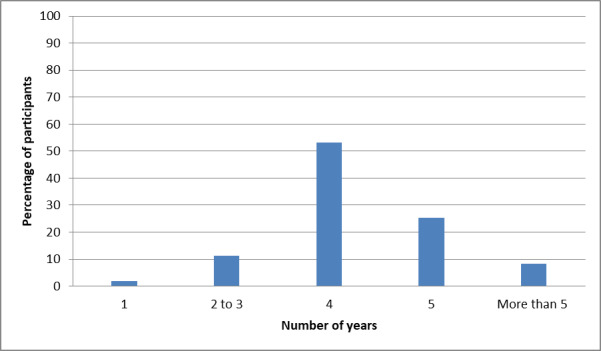

Concerning SLPs and audiologists studying and training, most participants (n=1404 ; 53.2%) reported that SLPs or audiologists need four years of study and training to become SLPs or audiologists (Figure 3 ).

Figure 3 . Figure 3. The duration of studying that speech-languagepathologists (SLPs) and audiologists need indicated by theparticipants (n=2640)..Figure 3. The duration of studying that speech-language pathologists (SLPs) andaudiologists need indicated by th.

Although most of the study participants (74.7%) reported that audiologists and deaf and hard of hearing teachers do not do the same work, 25.3 % believed that they do the same work. Furthermore, 80.5% of the participants reported that speech-language pathologists and special education teachers do not do the same work. In contrast, 19.5% of the participants believed that they do the same work.

The majority of the participants (81.4%) reported that the primary services audiologists conduct is diagnosing hearing loss. Surprisingly, 15.7% of responders did not know what audiologists do (Figure 4 ). Regarding speech-language pathologists' jobs, while most participants (81%) reported that SLPs improve a person's speech, only 17.3% believed that SLPs diagnose and manage swallowing disorders (Figure 5 ).

Figure 4 . Figure 4. The distribution of the job of audiologists in Jordan reported by participants(n=2640). Note: the participants were able to report choose than one answer.

Figure 5 . Figure 5. The distribution of the job of speech-language pathologists(SLPs) in Jordan indicated by the participants (n=2640). Note: theparticipants were able to choose more than one answer.

Impact of personal characteristics on level of awareness

Findings indicated no significant differences in terms of gender, age, region, qualification, whether there are children or not, and family income. In contrast, results showed significant differences in terms of field of occupation.

Participants working in the fields of health were more experience with communication and hearing disorders than participants working in other areas in terms of seeing, listening or reading anything about communication and hearing disorders (P=.013). Moreover, participants working in health fields were more aware of SLP and audiology than others in terms of workplace of SLPs and audiologists (P=.026), needing a referral from a physician to visit a speech-language pathologist or an audiologist (P=.005), and the length of study and training SLPs and audiologists need (P=.003).

Discussion

Our results showed that the levels of public awareness of different aspects of SLP and audiology professions in Jordan are not high. Moreover, findings showed that individuals working in health fields are more aware than others, confirming the hypothesis of our study.

Experience with communication and hearing disorders

Only a few participants were diagnosed with a communication disorder, hearing loss, or both; however, 29.2% of participants knew someone with hearing loss, 13% knew someone with communication disorders, and 4.2% of participants knew someone with both. Most of those who knew someone with a communication and/or hearing disability were first-degree relatives. According to the Canadian Association of Speech-Language Pathologists and Audiologists (19 ), speech and hearing disorders impact tens of thousands of people. Another study performed in Australia on primary and secondary school students across three years showed that the prevalence of communication disorders was 13% and 12.4% in the first and second years, respectively (20 ).

Awareness of speech-language pathology and audiology

Most responders (59.5%) indicated they had not seen, heard, or read anything about communication or hearing disorders. Also, most participants had never met a speech-language pathologist or audiologist. A major reason for this may be the lack of sufficient public awareness programs about communication and hearing disorders.

It is encouraging to find that most survey participants believed that seeing an SLP or audiologist did not require a referral from a physician, which is a good thing because not all physicians are well-versed in the symptoms, assessment, and treatment of communication and hearing disorders. Another finding relating to settings that employed SLPs and audiologists showed that 74.6% of the study participants believed that private clinics were the most workplace for SLPs and audiologists. In contrast, the awareness of other settings was limited. This finding consisted with Alanazi & Al Fraih (16 ). Furthermore, the majority of the participant thought that SLPs and audiologists work with toddlers and pre-schoolers and the elderly. However, most of them believed that SLPs and audiologists do not work with other populations. This may be because the majority of individuals with communication disorders are of preschool and older age. It may be essential to educate the general population that SLPs and audiologists are qualified to deal with individuals of all ages.

Regarding SLPs and audiologists studying and training, more than half of the participants reported that SLPs and audiologists need four years of studying and training. This finding contrast with a study was conducted by Alanazi & Al Fraih (16 ), which showed that SLPs and audiologists need only 2-3 years of studying and training. It was interesting to find a high percentage of participants were able to distinguish audiologists from teachers of deaf and hard of hearing, and speech-language pathologists and special needs teachers. However, SLPs and audiologists should keep working to educate the public about the services that both professions

offer and the significance of carefully seeking SLPs and audiologists to ensure they possess the qualifications required.

Although most of the participants reported that the main services audiologists perform are evaluating hearing loss, improving hearing and prescribing, and fitting hearing aids and assistive listening devices. In contrast, less than half of the participants indicated that audiologists evaluate and manage tinnitus and vestibular diseases. The participants were aware that providing medication and performing surgery are not responsibilities performed by audiologists. Audiologists may wish to make it known that they are trained and qualified to deal with tinnitus and vestibular diseases.

Regarding speech-language pathology, most participants indicated that SLPs provide services relating to verbal communication skills, including improving speech, evaluating, and managing communication disorders and stuttering. All of which are more noticeable disorders given their nature. These areas of practice are the main everyday jobs of SLPs in Jordan, in addition to improving receptive language skills. In contrast, less than 20% of the participants reported that speech-language pathologists diagnose and manage swallowing disorders. Despite the lower percentage of participants that thought swallowing was within the scope of SLPs, it is still a promising rate, as only 4% of registered nurses that participated in a hospital study reported SLPs as the specialists responsible for diagnosing and managing swallowing difficulties (21). The participants were aware that providing medication and performing surgery are not responsibilities performed by SLPs. SLPs may wish to make it known that they are trained and qualified to deal with voice, swallowing and neurogenic communication disorders (14 ).

Impact of personal characteristics on level of awareness

Concerning the association between participants’ personal traits and their awareness of SLP and audiology professions, participants working in health fields were more aware than others.

Finding was in line with Mahmoud et al. (14 ).

Limitation

This study did not investigate community awareness of communication and hearing disorders. Further studies are needed to investigate the community awareness of specific communication and hearing disorders.

In conclusion, this study has investigated public awareness of speech-language pathology and audiology professions in Jordan. For that purpose, a sample of 2640 participants completed the questionnaire. Overall, it seems that the levels of public awareness of different aspects of SLP and audiology professions in Jordan are not high. Therefore, it is essential to raise public awareness of speech-language pathology and audiology services through various available ways (e.g. social media and public education initiatives).

References

- Justice Laura M. Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall Upper Saddle River, NJ; 2006. Communication sciences and disorders: An introduction. [Google Scholar]

- Koegel Lynn Kern, Bryan Katherine M, Su Pumpki L, Vaidya Mohini, Camarata Stephen. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 8. Vol. 50. Springer; 2020. Definitions of nonverbal and minimally verbal in research for autism: A systematic review of the literature; pp. 2957–2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland Audrey L, Nelson Ryan L. Plural Publishing; 2018. Counseling in communication disorders: A wellness perspective. [Google Scholar]

- de Britto Pereira Monica Medeiros, Rossi Jamile Perni, Van Borsel John. Journal of fluency disorders. 1. Vol. 33. Elsevier; 2008. Public awareness and knowledge of stuttering in Rio de Janeiro; pp. 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Utari Alisa, Putri The Respectful Attitude and Communication Ways towards Elderly: Perspective from adolescents. JIPM: Jurnal Ilmiah Psikomuda Connectedness. 2021;1(2):31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Moyle Maura, Long Steven. Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Springer; 2021. Receptive language disorders; pp. 3880–3885. [Google Scholar]

- American Speech-Hearing Association. https:// www.asha.org/policy/rp1993-00208/ https:// www.asha.org/policy/rp1993-00208/

- Powell Rachel K. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2. Vol. 49. ASHA; 2018. Unique contributors to the curriculum: From research to practice for speech-language pathologists in schools; pp. 140–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramage Amy E. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 4. Vol. 29. ASHA; 2020. Potential for cognitive communication impairment in COVID-19 survivors: a call to action for speech-language pathologists; pp. 1821–1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franca Maria Claudia, Smith Linda McCabe, Nichols Jane Luanne, Balan Dianna Santos. Culturally diverse attitudes and beliefs of students majoring in speech-language pathology. CoDAS. 2016;28:533–545. doi: 10.1590/2317-1782/20162015245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Speech-Hearing Association. https:// www.asha.org/students/audiology/ https:// www.asha.org/students/audiology/

- Stach Brad A, Ramachandran Virginia. Plural Publishing; 2021. Clinical audiology: An introduction. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson Vickie, Yoshinaga-Itano Christine. American Journal of Audiology. 3. Vol. 27. ASHA; 2018. The role of audiologists in assuring follow-up to outpatient screening in early hearing detection and intervention systems; pp. 283–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud Hana, Aljazi Aya, Alkhamra Rana. College Student Journal. 3. Vol. 48. Project Innovation; 2014. A study of public awareness of speech-language pathology in Amman; pp. 495–510. [Google Scholar]

- Janes Tina Leann, Zupan Barbra, Signal Tania. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 1. Vol. 29. Wiley; 2021. Community awareness of speech pathology: A regional perspective; pp. 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alanazi Ahmad A, Al Fraih Sarah S. Majmaah Journal of Health Sciences. 2. Vol. 9. Majmaah University; 1970. Public Awareness of Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology in Saudi Arabia; pp. 36–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tang Keng Ping, Chu Shin Ying. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. Vol. 2021. Informa UK Limited; Public Awareness of Communication Disorders and Speech-Language Therapy in Malaysia; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud Hana Nawaf, Mahmoud Abdelhameed N. Journal of Language Teaching and Research. 6. Vol. 10. Academy Publication Co., Ltd.; 2019. Knowledge and attitudes of jordanian dentists toward speech language pathology; pp. 1298–1306. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod Sharynne, McKinnon David H. International journal of language & communication disorders. S1. Vol. 42. Wiley Online Library; 2007. Prevalence of communication disorders compared with other learning needs in 14 500 primary and secondary school students; pp. 37–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoja M A. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance. 8. Vol. 31. Emerald; 2018. Registered nurses’ knowledge and care practices regarding patients with dysphagia in Saudi Arabia; pp. 896–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]