Abstract

Purpose of review

Management for patients with refractory eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) remains a clinical challenge. This review aims to define refractory EoE, explore rates and reasons for nonresponse, and discuss the evidence that informs the approach to these patients.

Recent findings

Many patients will fail first-line therapies for EoE. Longer duration of therapy can increase response rates, and initial nonresponders may respond to alternative first-line therapies. There are ongoing clinical trials evaluating novel therapeutics that hold promise for the future of EoE management. Increasingly, there is recognition of the contribution of oesophageal hypervigilance, symptom-specific anxiety, abnormal motility and oesophageal remodelling to ongoing clinical symptoms in patients with EoE.

Summary

For refractory EoE, clinicians should first assess for adherence to treatment, adequate dosing and correct administration. Extending initial trials of therapy or switching to an alternative first-line therapy can increase rates of remission. Patients who are refractory to first-line therapy can consider elemental diets, combination therapy or clinical trials of new therapeutic agents. Patients with histologic remission but ongoing symptoms should be evaluated for fibrostenotic disease with EGD, barium esophagram or the functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) and should be assessed for the possibility of oesophageal hypervigilance.

Keywords: dysphagia, eosinophilic esophagitis management, eosinophilic esophagitis therapies, refractory eosinophilic esophagitis

INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune-mediated disease defined by symptoms of oesophageal dysfunction and increased eosinophils of at least 15 per high-powered field (hpf) on histopathology in the absence of other diseases that can cause oesophageal eosinophilia [1]. Adults most commonly present with dysphagia, food impactions and chest pain, but children can present with a variety of nonspecific symptoms such as feeding difficulties, failure to thrive and vomiting [2,3]. Unfortunately, there are still no FDA-approved therapies for EoE, and treatment options include dietary approaches, off-label use of medications and oesophageal dilation [4,5]. No currently available treatment approach is completely effective, and the management of patients who are refractory to standard therapy remains a clinical challenge. The goals of this review are to define refractory EoE, explore rates and reasons for nonresponse, and discuss the evidence that informs the current approach to these patients.

HOW DO WE CURRENTLY TREAT EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS?

Treatments for EoE at present include medications, diet and dilation with the goal of clinical and histologic remission. Although none are FDA-approved, current first-line medications are proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and topical corticosteroids [5,6■■]. As there are no oesophageal-specific steroid formulations available in the United States, budesonide or fluticasone formulated for asthma is swallowed instead of inhaled by patients using off-label instructions. EoE can be managed with diet, and the most common approach is the six-food elimination diet (SFED) wherein patients remove the six most common food groups associated with EoE: milk, wheat, eggs, soy, peanuts/tree nuts and fish/shell-fish [7]. Current practice is informed by the 2020 AGA and Joint Task Force (JTF) guideline, the 2018 AGREE consensus, the 2017 European guidelines and the 2013 ACG guidelines [1,4,5,6■■]. There is currently no first-line therapy per se, and treatment decisions should utilize a shared decision-making model based on efficacy, cost, ease of administration and patient preferences. Of note, the only treatment approach to receive a strong recommendation by the AGA/JTF review was topical corticosteroids [6■■]. Endoscopic dilation can remedy symptoms that originate from fibrostenotic disease, but will not treat the underlying inflammation [8–10].

HOW DO WE DEFINE REFRACTORY EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS?

Despite all of the above best practice guidelines, there is still no standardized definition for either what constitutes response to therapy or refractory EoE. Histologic remission has traditionally been defined as eosinophils less than 15/hpf, but this has not been standardized among clinical trials with varying histologic endpoints. Trials requiring regulatory approval by the FDA have utilized co-primary endpoints of histologic remission (eos <6/hpf) and patient-reported outcomes [11,12]. In addition, Greuter et al. [13] have introduced the concept of deep remission, defined as clinical remission (lack of any EoE attributable symptom under unrestricted dietary habits), histological inflammatory remission (eos <5/hpf) and endoscopic inflammatory remission (complete absence of endoscopic inflammatory features). Furthermore, it is well known that improvement in symptoms does not necessarily correlate with endoscopic or histologic measures of disease activity, especially in patients with fibrostenotic disease [14,15]. Finally, oesophageal hypervigilance and symptom-specific anxiety may contribute to patient-reported symptoms [16■].

To date, there has been no standard definition for refractory EoE. In a previous review by Dellon [17] in 2017, their definition was persistent eosinophilia (≥15 eos/hpf), incomplete resolution of primary presenting symptoms and incomplete resolution of endoscopic findings after treatment. A pragmatic definition by Hirano in 2015 included persistent symptoms, persistent inflammation or both after therapy [18]. Recognizing that definitions for response to therapy are not standardized, we will similarly define refractory EoE as persistent symptoms, persistent oesophageal inflammation on histology or endoscopy, or a combination of both after treatment for EoE.

WHAT ARE THE RATES OF NONRESPONSE TO CURRENT THERAPY?

In order to understand refractory EoE, it is critical to understand the response rates to each of the current first-line treatments. The AGA/JTF performed the most recent systematic review that evaluated histologic response rates to therapy, defined as less than 15 eos/hpf at 8 weeks (Table 1). The pooled histologic response rate from 23 observational studies of PPI therapy was 41.7%, 64.9% for corticosteroids based on eight double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs, and 67.9% for empiric SFED from 10 single-arm observational studies [6■■]. Patients on diets with fewer food groups eliminated had lower rates of remission. As such, it is estimated that 32–58% of patients will fail first-line treatments for EoE.

Table 1.

Current therapies for eosinophilic esophagitis and response rates

| Treatment approach | Dose or methods | Pooled histologic response ratea |

|---|---|---|

| Proton pump inhibitors | Omeprazole 20 mg twice daily Pantoprazole 40 mg twice daily Lansoprazole 30 mg twice daily Rabeprazole 20 mg twice daily |

41.7% |

| Topical corticosteroids | Fluticasone 440–880 μg twice daily Budesonide 1 – 2 mg twice daily |

64.9% |

| 6-food elimination diet (SFED) | Eliminated foods consisting of milk, soy, wheat, egg, nut and fish/seafood | 67.9% |

| Elemental diet | Formula made of amino acids | 93.6% |

Histologic response defined as eosinophils <15/hpf after 8 weeks of treatment.

WHAT ARE THE REASONS FOR NONRESPONSE?

The underlying pathophysiology of EoE is complex, and there is no single therapeutic approach that addresses all aspects of immune dysfunction and subsequent cytokine signalling [19]. In patients failing to respond, it is important to first readdress the accuracy of the diagnosis and assess for secondary causes of oesophageal eosinophilia (Table 2) [1]. If the diagnosis remains correct, the next step is to distinguish between patients in histologic remission with ongoing clinical symptoms and patients with both histologic and clinical nonresponse.

Table 2.

Other causes of oesophageal eosinophilia

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) |

| Crohn’s disease |

| Achalasia |

| Hypereosinophilic syndrome |

| Drug hypersensitivity reactions |

| Infections |

| Eosinophilic gastroenteritis |

| Dermatologic conditions with oesophageal involvement |

| Graft versus host disease |

| Connective tissue diseases |

| Autoimmune disorders and vasculitis |

| Pill-induced oesophageal injury |

For patients with ongoing evidence of histologic inflammation, one should first assess for adherence, dosing and appropriate administration of therapy. Insurance coverage and subsequent cost can be a barrier to compliance, as no pharmacologic treatment option for EoE is FDA-approved. Patients can have difficulty with administration of topical corticosteroids using off-label instructions that are not standardized. Timing of medications can be challenging, especially with topical corticosteroids, that should have adequate time to dwell prior to eating or drinking [20]. Adherence with long-term medications is a challenge. For example, over a 5-year period in one observational study, patients were still taking prescribed maintenance swallowed corticosteroid at only 40% of the visits [21]. Adherence to dietary elimination is similarly difficult with one study showing only a 57% compliance rate. Patients cited difficulty with social situations, diet-related anxiety and perceived diet effectiveness for symptomatic relief [22]. Studies have demonstrated seasonal variation in the diagnosis of EoE, with cases more frequently diagnosed during summer months, suggesting that aeroallergens may contribute to flares [23–25].

Patients may also have symptoms of oesophageal dysfunction in the setting of complete histologic remission. Remodelling features such as rings and strictures may contribute to clinical nonresponse. A barium esophagram may be a helpful adjuvant study to evaluate for subtle strictures or narrowed oesophagus, which can be missed at the time of endoscopy[26]. Oesophageal dysmotility may cause ongoing symptoms, which can be evaluated with either manometry or the functional luminal-imaging probe (FLIP). In one study of 199 patients with EoE, the contractile response pattern was characterized by FLIP, and only 34% of EoE patients had a normal contractile response with the remaining patients having abnormal contractile response patterns. An abnormal contractile response was associated with fibrostenotic disease, but there was no difference in levels of eosinophils on histology among the different response patterns [27■]. Oesophageal hypervigilance and symptom-specific anxiety may contribute to ongoing symptoms in EoE patients. Recent work from the Northwestern group found that hypervigilance and symptom-specific anxiety were the only predictors of increased dysphagia symptoms even when accounting for both histologic and endoscopic variables [16■]. Finally, it is important to recognize that patients treated with swallowed steroid preparations may develop odynophagia in the setting of Candida esophagitis, which may be amenable to treatment with antifungal agents.

CAN WE OPTIMIZE CURRENT TREATMENTS?

There is some evidence that changes in dosage and duration of available therapies can impact response rates. In current pract0ice, most providers perform trials of therapy with evaluation for treatment response in approximately 8 weeks. However, emerging data suggest that duration of therapy may favourably impact remission rates. In a 5-year observational study on the Swiss EoE cohort, longer treatment course of budesonide was associated with a higher rate of complete (endoscopic, clinical, histologic) remission [21]. In a randomized clinical trial in Europe, budesonide orodispersible tablets resulted in clinical and histologic remission in 58% of individuals at 6 weeks, which increased to 85% at 12 weeks [28,29]. There was, however, no difference between the budesonide 1 mg twice-daily versus 2 mg twice-daily doses [29]. A randomized clinical trial found that 26% of patients who did not initially respond to fluticasone propionate orally disintegrating tablets at 12 weeks then achieved histologic remission when treatment was extended to 52 weeks [30■]. A large observational study found that 50.4% of patients achieved clinic-histologic remission (eos <15/hpf) after 8–10 weeks on a PPI, which increased to 65.2% with 10–12 weeks of therapy. The histologic remission rate was higher for patients treated with high-dose PPI therapy than standard or low-dose therapy (50.8 versus 35.8%, P = 0.027) with no difference between different PPI formulations [31■]. For dietary therapy, one study found seven patients with a partial reduction in eosinophils (average 38.5 to 21.5 at 6–8 weeks) in response to an elimination diet. These patients then underwent an extended period of dietary elimination (mean of 13 additional weeks), which led to histologic remission (<15 eos per hpf) in all patients [32]. Other work has found no improvement in clinical and histologic response when treatment duration was increased beyond 10 weeks for dietary therapy, 12 weeks for PPIs or 16 weeks for topical steroids [33■]. Overall, the evidence suggests that an increased duration of therapy beyond 8 weeks may be beneficial for a subset of patients who do not achieve histologic remission. For patients on low-dose or standard-dose PPI therapy, an increase to high-dose PPI should be considered.

WHAT IS THE ROLE FOR COMBINING OR TRANSITIONING TO OTHER FIRST-LINE THERAPIES?

There are limited data on the efficacy of transitioning patients to a different first-line therapy. For patients who fail treatment with a topical corticosteroid, a trial of an alternative formulation should be considered, as fluticasone 880 mg twice daily (b.i. d.) and budesonide 1 mg (b.i.d.) have comparable efficacy of 71 and 64% (P = 0.38) as shown in the landmark randomized clinical trial by Dellon et al. [20]. In one study, PPI therapy was less effective in inducing clinical and histologic remission for patients who had previously failed diet or swallowed corticosteroids than when used as a primary therapy [31■]. A European observational study evaluated 344 patients who failed a first-line therapy and were subsequently switched to another therapy. Of these patients, 78.8% of patients who transitioned to topical steroids achieved histologic remission (eos <15/hpf) compared with 64.8% of patients switched to PPIs, and 39.4% of patients switched to diet [33■].

Although commonly done in clinical practice, evidence supporting combination therapy is limited. In theory, a combination of PPIs, diet and topical corticosteroids targets different aspects of the underlying pathophysiology of EoE. An observational study of 23 patients, who did not respond to SFED or topical steroid monotherapy, examined the response of these patients to combination therapy with heterogeneous dietary treatments and a swallowed corticosteroid. At a mean of 4 months, 88% of patients reported global symptomatic improvement with an associated decrease in eosinophil count (54 to 36 eos/hpf). At 30.5 months, 82% of patients had a global symptomatic response, despite having a mean peak eosinophil count similar to baseline (54 versus 46, P = 0.34) [34]. Another observational study of 71 adult and paediatric patients did not show a difference in outcomes for combination therapy of topical corticosteroids and a PPI compared with steroid monotherapy [35]. As such, data to date support transitioning to an alternative first-line therapy with the highest success rates being for topical steroids. The data evaluating combination therapies are limited, but combining a PPI and steroids or diet could be considered in clinical practice if switching to an alternative first-line therapy is not successful.

WHAT ARE OTHER TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR PATIENTS WITH REFRACTORY EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS?

There are a number of options for patients who fail all of the first-line therapeutic options, each with limitations. Systemic corticosteroids are effective, but have multiple adverse effects for long-term administration and have similar response rates to topical corticosteroids [36]. Systemic corticosteroids should be limited to short-term use [4]. Elemental formulas are hypoallergenic formulations of amino acids, simple carbohydrates and medium-chain triglycerides with a high response rate of 93.9% [6■■,37,38]. However, elemental diets are expensive and difficult to tolerate, occasionally requiring feeding tubes to maintain adequate nutrition. There are limited data to support the use of montelukast, cromolyn, immune modulators, anti-IgE or anti-TNFs, and none are currently recommended by the AGA/JTF [6■■,39].

Oesophageal dilation should be considered as an acute or additional therapy, as intervention can improve swallowing dysfunction [6■■]. A systematic review and meta-analysis found 95% clinical improvement with dilation and low rates (<1%) of major complications [8]. Dilation is an option for managing fibrostenotic disease and can provide symptomatic relief for 15–17 months regardless of medical therapy [9,40■,41]. Work from the Northwestern group in a group of patients with severe strictures (oesophageal lumen <10 mm) managed with serial dilations found that 89.4% of patients experienced improvement in oesophageal diameter to at least 13 mm and 65.2% to at least 15 mm. Of note, 85.5% of these patients achieved histologic remission, and only one patient was managed with dilation alone [42].

WHAT ARE POTENTIAL TREATMENT MODALITIES FOR THE FUTURE?

Trials of novel steroid compounds and therapies for targeting immune pathways and cytokine signalling offer considerable potential in the future for more targeted therapy of EoE. In Europe, budesonide orally dissolving tablets, formulated to optimize oesophageal delivery, are already available. Budesonide oral suspension and orally dissolving fluticasone are undergoing clinical trials but are not yet approved by the FDA [30■,43■■]. These formulations eliminate the heterogeneity found with off-label use of corticosteroids and improve ease of administration. A variety of mAbs that target eosinophils or inflammatory signalling pathways have been developed and are under study such as Benralizumab (NCT04543409), Dupilumab (NCT03633617), Cendakimab (NCT04753697), Etrasimod (NCT04682639), IRL 201104 (NCT05084963) and Lirentelimab (NCT04322708). Notably, a phase 2 clinical trial of Cendakimab, an anti-IL13 mAb, demonstrated significant reductions in oesophageal eosinophil counts, histologic features and endoscopic features for a subgroup of enrolled patients with steroid refractory disease [44]. At this time, patients refractory to standard therapy have a variety of clinical trials to consider entering (Table 3) [6■■].

Table 3.

Clinical trials of novel biologics

| Therapy | Target | Clinical trial number |

|---|---|---|

| Benralizumab | IL-5 | NCT04543409 |

| Mepolizumab | IL-5 | NCT03656380 |

| Dupilumab | IL-4 and IL-13 | NCT03633617 |

| Cendakimab | IL-13 | NCT04753697 |

| Etrasimod | selective sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulator | NCT04682639 |

| IRL 201104 | an anti-inflammatory peptide | NCT05084963 |

| Lirentelimab | siglec-8 selectively expressed in eosinophils and mast cells | NCT04322708 |

CONCLUSION

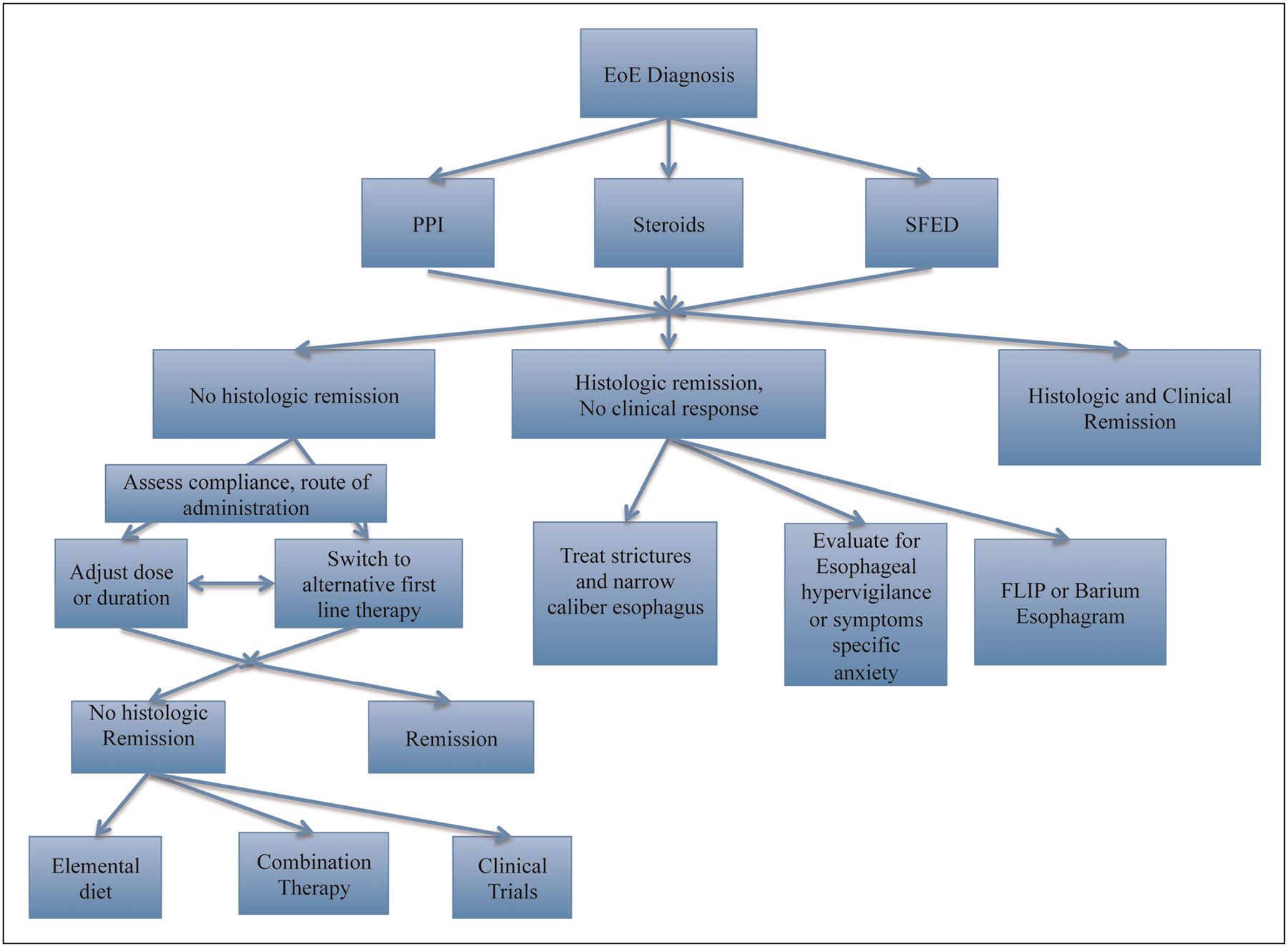

First-line treatments for EoE consist of PPIs, swallowed corticosteroids, diet and oesophageal dilation (see Fig. 1 for management algorithm). However, many patients will not have histologic remission after an initial course of therapy, and with rare exceptions, we are unable to predict who will respond to what therapy. When faced with a patient with refractory EoE, clinicians should assess for an alternative cause of oesophageal eosinophilia, compliance, appropriate route of medication administration and adequate dosage prior to changing therapy. Optimization of current treatment can be considered with extension to 12 weeks. Switching to an alternative first-line therapy can be successful with highest response rates for steroids. Combination therapy is often used in practice, but additional studies are needed to define response rates. An elemental diet or systemic steroids can be considered in patients with refractory EoE with severe symptoms. Patients with histologic remission but ongoing symptoms should have evaluation for fibrostenotic disease with EGD, barium swallow or FLIP and for symptom-specific anxiety and oesophageal hypervigilance. Patients who do not respond to any first-line treatment should consider enrolling in clinical trials on novel therapeutics. At this time, there remain many unanswered questions for managing the patient with refractory disease (Table 4).

FIGURE 1.

This is a suggested treatment algorithm for managing patients with refractory eosinophilic esophagitis. After a trial of a first-line therapy, patients with histologic remission but ongoing symptoms should have evaluation for fibrostenotic disease with EGD, barium swallow or FLIP and for symptom-specific anxiety and oesophageal hypervigilance. After assessing for adherence and correct administration, patients who do not respond to first-line treatments should consider changing duration or dosing of initial therapy or trying alternative first line therapy. With continued nonresponse, one can consider combination therapy, enrolling in clinical trials of novel therapeutics or elemental diets.

Table 4.

Unanswered questions for eosinophilic esophagitis

|

KEY POINTS.

For refractory EoE, clinicians should first assess for appropriate diagnosis, adherence to treatment, adequate dosing and correct administration.

Extending duration of initial trial of therapy or switching to an alternative first-line therapy can increase rates of remission.

Patients with histologic remission but ongoing symptoms should be evaluated for fibrostenotic disease with EGD, barium esophagram or the functional luminal imaging probe (FLIP) and should be assessed for the possibility of oesophageal hypervigilance.

Patients who do not respond to first-line treatments should consider combination therapy or enrolling in clinical trials of novel therapeutics.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported in part by the NIH/NIDDK Center for Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Disease P30DK050306 and by the Consortium for Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Research (CEGIR) U54 AI117804, which is part of the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), an initiative of the Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR), NCATS and is funded through collaboration between NIAID, NIDDK and NCATS. CEGIR is also supported by patient advocacy groups, including American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders (APFED), Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Diseases (CURED) and Eosinophilic Family Coalition (EFC). As a member of the RDCRN, CEGIR is also supported by its Data Management and Coordinating Center (DMCC) (U2CTR002818).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

■ of special interest

■■ of outstanding interest

- 1.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, et al. Updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: proceedings of the AGREE conference. Gastroenterology 2018; 155:1022–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Beausoleil JL, et al. 14 Years of eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical features and prognosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009; 48:30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Croese J, Fairley SK, Masson JW, et al. Clinical and endoscopic features of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. Gastrointest Endosc 2003; 58:516–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, et al. ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:679–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucendo AJ, Molina-Infante J, Arias Á, et al. Guidelines on eosinophilic esophagitis: evidence-based statements and recommendations for diagnosis and management in children and adults. United Eur Gastroenterol J 2017; 5:335–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rank MA, Sharaf RN, Furuta GT, et al. Technical review on the management of eosinophilic esophagitis: a report from the AGA institute and the joint task force on allergy-immunology practice parameters. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2020; 124:424–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ■■ A systematic review that grades evidence for different treatment modalities for EoE.

- 7.Gonsalves N, Yang G, Doerfler B, et al. Elimination diet effectively treats eosinophilic esophagitis in adults; food reintroduction identifies causative factors. Gastroenterology 2012; 142:1451–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moawad FJ, Cheatham JG, DeZee KJ. Meta-analysis: the safety and efficacy of dilation in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013; 38:713–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoepfer AM, Gonsalves N, Bussmann C, et al. Esophageal dilation in eosinophilic esophagitis: effectiveness, safety, and impact on the underlying inflammation. J Am Gastroenterol 2010; 105:1062–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Rubinas TC, et al. Esophageal dilation in eosinophilic esophagitis: safety and predictors of clinical response and complications. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 71:706–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirano I, Furuta GT. Approaches and challenges to management of pediatric and adult patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2020; 158:840–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eosinophilic esophagitis: developing drugs for treatment - FDA [Internet]. FDA; 2020. [cited 7 January 2022]. https://www.fda.gov/media/120089/download. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greuter T, Bussmann C, Safroneeva E, et al. Long-term treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis with swallowed topical corticosteroids: development and evaluation of a therapeutic concept. J Am Gastroenterol 2017; 112:1527–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safroneeva E, Straumann A, Coslovsky M, et al. Symptoms have modest accuracy in detecting endoscopic and histologic remission in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2016; 150:581–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoepfer AM, Simko A, Bussmann C, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: relationship of subepithelial eosinophilic inflammation with epithelial histology, endoscopy, blood eosinophils, and symptoms. J Am Gastroenterol 2018; 113:348–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taft TH, Carlson DA, Simons M, et al. Esophageal hypervigilance and symptom-specific anxiety in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2021; 161:1133–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ■ A retrospective study evaluating rates of oesophageal specific-symptom anxiety and hypervigilance and as predictors for clinical outcomes.

- 17.Dellon ES. Management of refractory eosinophilic oesophagitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 14:479–490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sodikoff J, Hirano I. Therapeutic strategies in eosinophilic esophagitis: induction, maintenance and refractory disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2015; 29:829–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Shea KM, Aceves SS, Dellon ES, et al. Pathophysiology of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2018; 154:333–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dellon ES, Woosley JT, Arrington A. Efficacy of budesonide vs fluticasone for initial treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2019; 157:65–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greuter T, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, et al. Maintenance treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis with swallowed topical steroids alters disease course over a 5-year follow-up period in adult patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 17:419–428.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang R, Hirano I, Doerfler B, et al. Assessing adherence and barriers to long-term elimination diet therapy in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci 2018; 63:1756–1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cianferoni A, Jensen E, Davis CM. The role of the environment in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021; 9:3268–3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jensen ET, Shah ND, Hoffman K, et al. Seasonal variation in detection of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42:461–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spergel J, Aceves SS. Allergic components of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 142:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gentile N, Katzka D, Ravi K, et al. Oesophageal narrowing is common and frequently under-appreciated at endoscopy in patients with oesophageal eosinophilia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 40(11–12):1333–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlson DA, Shehata C, Gonsalves N, et al. Esophageal dysmotility is associated with disease severity in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ■ This study evaluated secondary peristalsis in EoE and found that patients with abnormal contractile reserve were more likely to have increased disease severity and features of fibrostenosis.

- 28.Lucendo AJ, Miehlke S, Schlag C, et al. Efficacy of budesonide orodispersible tablets as induction therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2019; 157:74–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miehlke S, Hruz P, Vieth M, et al. A randomised, double-blind trial comparing budesonide formulations and dosages for short-term treatment of eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut 2016; 65:390–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dellon ES, Lucendo A, Schlag C, et al. S0345 Safety and efficacy of long-term treatment of EoE with fluticasone propionate orally disintegrating tablet (APT-1011): results from 40 weeks treatment in a Phase 2b randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J Am Gastroenterol 2020; 115:S169. [Google Scholar]; ■ This was a randomized control trial evaluating efficacy of novel fluticasone formulation.

- 31.Laserna-Mendieta EJ, Casabona S, Guagnozzi D, et al. Efficacy of proton pump inhibitor therapy for eosinophilic oesophagitis in 630 patients: results from the EoE connect registry. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2020; 52:798–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ■ This cross-sectional study evaluated PPI efficacy on a multicentre cohort in Europe.

- 32.Philpott H, Dellon E. Histologic improvement after 6 weeks of dietary elimination for eosinophilic esophagitis may be insufficient to determine efficacy. Asia Pac Allergy 2018; 8:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laserna-Mendieta EJ, Casabona S, Savarino E, et al. Efficacy of therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis in real-world practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 18:2903–2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ■ This was an observational study of a European database looking at treatment outcomes for a large cohort of patients.

- 34.Reed CC, Tappata M, Eluri S, et al. Combination therapy with elimination diet and corticosteroids is effective for adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 17:2800–2802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heisel M, Min S, Oparaji J-A, et al. Comparing combination therapy with proton pump inhibitor and topical steroid versus topical steroid alone for the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. Pediatrics 2019; 144:893. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaefer ET, Fitzgerald JF, Molleston JP, et al. Comparison of oral prednisone and topical fluticasone in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: a randomized trial in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6:165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peterson KA, Byrne KR, Vinson LA, et al. Elemental diet induces histologic response in adult eosinophilic esophagitis. J Am Gastroenterol 2013; 108:759–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Warners MJ, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Verheij J, et al. Elemental diet decreases inflammation and improves symptoms in adult eosinophilic oesophagitis patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017; 45:777–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alexander JA, Ravi K, Enders FT, et al. Montelukast does not maintain symptom remission after topical steroid therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 15:214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenberg S, Chang NC, Corder SR, et al. Dilation-predominant approach versus routine care in patients with difficult-to-treat eosinophilic esophagitis: a retrospective comparison. Endoscopy 2021. [Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ■ This retrospective cohort study compared patient outcomes with a dilation predominant approach compared with a standard approach.

- 41.Schoepfer A, Gschossmann J, Scheurer U, et al. Esophageal strictures in adult eosinophilic esophagitis: dilation is an effective and safe alternative after failure of topical corticosteroids. Endoscopy 2008; 40:161–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim JP, Weingart G, Hiramoto B, et al. Clinical outcomes of adults with eosinophilic esophagitis with severe stricture. Gastrointest Endosc 2020; 92:44–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dellon ES, Collins MH, Katzka DA, et al. Long-term treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis with budesonide oral suspension. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ■■ A randomized control trial for novel budesonide oral suspension that included extension of therapy to 52 weeks after initial 12–week induction period.

- 44.Hirano I, Collins MH, Assouline-Dayan Y, et al. RPC4046, a monoclonal antibody against IL13, reduces histologic and endoscopic activity in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2019; 156:592–603.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]