Abstract

Background

Guidelines for follow-up after locoregional breast cancer treatment recommend imaging for distant metastases only in the presence of patient signs and/or symptoms. However, guidelines have not been updated to reflect advances in imaging, systemic therapy, or the understanding of biological subtype. We assessed the association between mode of distant recurrence detection and survival.

Methods

In this observational study, a stage-stratified random sample of women with stage II-III breast cancer in 2006-2007 and followed through 2016 was selected, including up to 10 women from each of 1217 Commission on Cancer facilities (n = 10 076). The explanatory variable was mode of recurrence detection (asymptomatic imaging vs signs and/or symptoms). The outcome was time from initial cancer diagnosis to death. Registrars abstracted scan type, intent (cancer-related vs not, asymptomatic surveillance vs not), and recurrence. Data were merged with each patient’s National Cancer Database record.

Results

Surveillance imaging detected 23.3% (284 of 1220) of distant recurrences (76.7%, 936 of 1220 by signs and/or symptoms). Based on propensity-weighted multivariable Cox proportional hazards models, patients with asymptomatic imaging compared with sign and/or symptom detected recurrences had a lower risk of death if estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) negative, HER2 negative (triple negative; hazard ratio [HR] = 0.73, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.54 to 0.99), or HER2 positive (HR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.33 to 0.80). No association was observed for ER- or PR-positive, HER2-negative (HR = 1.14, 95% CI = 0.91 to 1.44) cancers.

Conclusions

Recurrence detection by asymptomatic imaging compared with signs and/or symptoms was associated with lower risk of death for triple-negative and HER2-positive, but not ER- or PR-positive, HER2-negative cancers. A randomized trial is warranted to evaluate imaging surveillance for metastases results in these subgroups.

More than 225 000 women are diagnosed with locoregional breast cancer annually and require follow-up after active treatment (1). Guidelines recommend clinician visits (specifically recommending against any further tests) to detect recurrence (2,3). Imaging is only recommended in the presence of patient signs and/or symptoms (2,3). The same guidelines apply to all locoregional breast cancer patients regardless of stage or molecular subtype.

Four clinical trials conducted in the 1980s provide the evidence to support these guidelines (4-7). A 2005 Cochrane review reported no differences in disease-free or overall survival with intensive systemic imaging compared with annual physician visits alone (8). These trials used liver ultrasound and chest X-rays for intensive systemic imaging as more advanced imaging modalities (magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], computed tomography [CT], positron emission tomography [PET], bone scans) did not yet exist. Further, there was a limited understanding of breast cancer biology with fewer therapeutic options. An updated 2016 Cochrane review again did not support surveillance systemic imaging but acknowledged major limitations in the existing evidence base and concluded “trials incorporating new biological knowledge and improved imaging technologies are needed” (9).

No modern-era randomized trials have assessed the effect of surveillance imaging for distant metastases on survival for women with locoregional breast cancer. This gap has resulted in wide practice variation (10) with studies suggesting patients at highest recurrence risk undergo more intensive follow-up (10). Patient and oncologist stakeholders identified a need for an observational study to justify and inform prospective trial design. To that end, we assessed survival for patients with distant recurrence after locoregional breast cancer detected by asymptomatic imaging vs signs and/or symptoms, stratified by molecular subtype.

Methods

Data Sources

This study combined primary data collection via medical record abstraction with data from the National Cancer Database (NCDB), a national registry (11,12). The NCDB is a joint program of the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (CoC) and the American Cancer Society and captures 70% of diagnosed cancers in the United States (11,13). Accredited facilities are required to follow 90% of patients diagnosed and treated at their facilities irrespective of where they receive follow-up care. Trained facility registrars collect diagnosis and treatment factors and survival using a standard manual (14). Imaging and recurrence were abstracted from medical records from the registrars’ own institutions and other institutions and clinician offices as part of a special study initiative. Deidentified data were provided to investigators for secondary analysis. This study was deemed exempt by the University of Wisconsin-Madison institutional review board.

Sampling

A stage-stratified random sample of up to 10 patients (7 American Joint Committee on Cancer pathologic stage II, 3 stage III) was selected from each of 1231 CoC facilities accredited in 2006-2007. These years were chosen to allow 5 years of data collection to ascertain systemic imaging and recurrence. The sample was limited to stage II-III given the low recurrence and mortality risk for stage I (15). The sampling strategy was designed to achieve a similar ratio of stage II-III patients as observed nationally (70% stage II, 30% stage III) (16). Of the CoC facilities, 99% (n = 1217, n = 11 360) participated. A minority of facilities did not have 10 eligible patients.

Eligibility Criteria

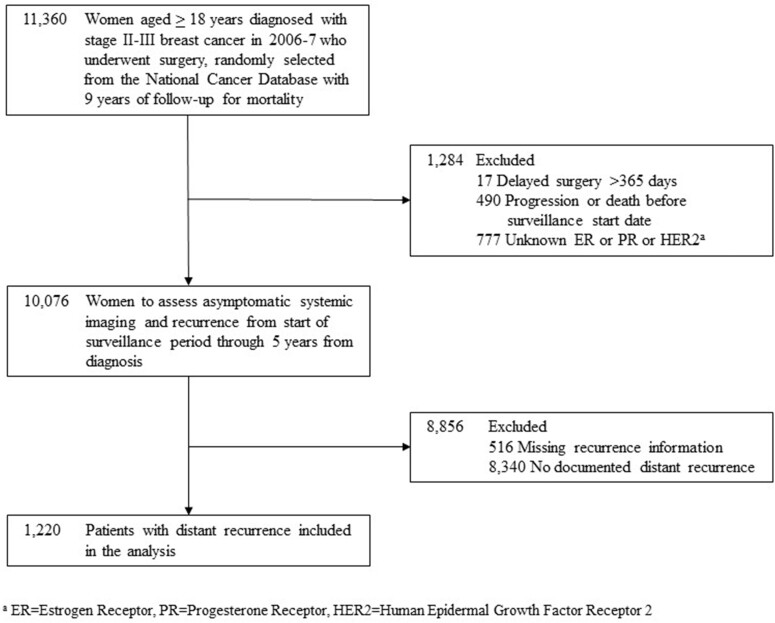

Women aged 18 years and older at diagnosis with stage II-III breast cancer were included. End date of treatment was unknown and approximated by 10 months from diagnosis. The sample size for abstraction was 10 076 patients (see Figure 1). Of 10 076 patients, 9560 had recurrence information (94.8%).

Figure 1.

Patient selection consort diagram.

Data Collection

Registrars at each facility solicited and reviewed records from their own and outside facilities/clinician offices starting at diagnosis for 5 years. Additional survival data was collected through 2016 to allow longer follow-up for this important endpoint. Information was abstracted using a standardized abstraction manual and entered via a secure CoC platform.

Registrars abstracted fields not routinely collected, including recurrence (17) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status. Registrars abstracted systemic imaging scans (chest CT, abdomen and pelvis CT and MRI, head CT and MRI, bone scan, PET or PET and CT) within the first 5 years of diagnosis and classified them as to intent. Systemic imaging was considered to be asymptomatic if classified by registrars as “surveillance imaging in the absence of new signs or symptoms (asymptomatic).” Systemic imaging was considered to be for signs and/or symptoms if imaging was conducted as “follow-up for new sign/symptom or for a suspicious finding on other imaging” or was “imaging performed as a part of staging work-up for a newly detected malignancy (either new primary or recurrence).” Registrars were guided to specific high-yield locations in medical records (eg, pathology reports, radiology and imaging reports, notes from clinic and consult visits) and contacted clinician offices for additional information. Existing NCDB fields (eg, treatment, death date) were confirmed or updated. Recorded data elements were merged with each patient’s corresponding NCDB record and re-encrypted prior to analysis.

Primary Outcome and Explanatory Variable

The primary outcome was overall survival, defined as the number of days from initial cancer diagnosis to death. This interval was chosen, as opposed to the time of distant recurrence detection to death, to reduce the potential for lead-time bias.

The primary explanatory variable was mode of distant recurrence detection for recurrences detected within 5 years of diagnosis, further categorized as follows: 1) asymptomatic imaging for cancer follow-up or as an incidental finding on unrelated imaging for other reason vs 2) “patient detected sign/symptom that prompted non-routine doctor visit,” “physician detected sign/symptom during routine visit,” or “detection as part of work up for a local/regional recurrence or new primary.” Registrars were instructed to code how the distant cancer recurrence was initially detected and not the diagnostic procedures or imaging that may have followed. The power calculation during study design was calculated based on previous cancer-related imaging in the literature (10,18-20). These estimates, derived from insurance claims, could not take into consideration the intent of scans. In a prior investigation based on these data, we found that 48% of patients received 1 or more systemic imaging scans during follow-up, consistent with claims-based studies. Once the intent of the scan was considered, 30% had more than 1 asymptomatic systemic scan, and only 12% had more than 2 asymptomatic systemic imaging scans of the same type (21).

Sociodemographic, Tumor, and Treatment Factors

Sociodemographic factors and comorbidity (22,23) measures are listed in Table 2. Tumor-related factors included tumor size, nodal status, and histology. Estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2 status were combined to create 3 tumor subtypes: 1) ER positive (ER+) or PR positive (PR+) and HER2 negative (HER2-); 2) ER negative (ER-) and PR negative (PR-) and HER2- (triple negative); 3) any ER or PR status and HER2 positive (HER2+) because these groups have been found to strongly predict recurrence and survival (15). Treatment factors included surgery type and receipt of radiation and systemic therapies. Reporting facility type was also included.

Table 2.

Characteristics of stage II-III breast cancer patients with distant recurrence by how recurrence was detected (sign and/or symptom vs asymptomatic imaging detected), overall population (unweighted)

| Patient characteristics | Overall (n= 1220)No. (%) | Symptom detected (n = 936) No. (%) | Asymptomatic imaging detected (n = 284) No. (%) | P a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Age, y | .82 | |||

| Younger than 50 | 401 (32.9) | 311 (33.2) | 90 (31.7) | |

| 50-69 | 552 (45.2) | 419 (44.8) | 133 (46.8) | |

| 70 and older | 267 (21.9) | 206 (22) | 61 (21.5) | |

| Race | .08 | |||

| Black | 191 (15.7) | 135 (14.4) | 56 (19.7) | |

| Other | 53 (4.3) | 43 (4.6) | 10 (3.5) | |

| White | 976 (80) | 758 (81) | 218 (76.8) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity | .59 | |||

| No | 1041 (85.3) | 804 (85.9) | 237 (83.5) | |

| Yes | 61 (5) | 45 (4.8) | 16 (5.6) | |

| Unknown | 118 (9.7) | 87 (9.3) | 31 (10.9) | |

| Mean percent in patient zip code with less than high school degree (SD), % | .37 | |||

| >29 | 237 (19.4) | 173 (18.5) | 64 (22.5) | |

| 20-28.9 | 272 (22.3) | 212 (22.6) | 60 (21.1) | |

| 14-19.9 | 271 (22.2) | 211 (22.5) | 60 (21.1) | |

| <14 | 387 (31.7) | 295 (31.5) | 92 (32.4) | |

| Unknown | 53 (4.3) | 45 (4.8) | 8 (2.8) | |

| Median household income in patient zip code | .47 | |||

| <$30 000 | 193 (15.8) | 147 (15.7) | 46 (16.2) | |

| $30 000-$34 999 | 192 (15.7) | 141 (15.1) | 51 (18) | |

| $35 000-$45 999 | 373 (30.6) | 291 (31.1) | 82 (28.9) | |

| >$46 000 | 409 (33.5) | 312 (33.3) | 97 (34.2) | |

| Unknown | 53 (4.3) | 45 (4.8) | 8 (2.8) | |

| Insurance status | .46 | |||

| Private insurance/managed care | 624 (51.1) | 480 (51.3) | 144 (50.7) | |

| Medicaid | 137 (11.2) | 110 (11.8) | 27 (9.5) | |

| Medicare and other governmentb | 379 (31.1) | 282 (30.1) | 97 (34.2) | |

| Uninsured/self-pay/insurance status unknown | 80 (6.6) | 64 (6.8) | 16 (5.6) | |

| Urban/Rural | .58 | |||

| Rural | 34 (2.8) | 25 (2.7) | 9 (3.2) | |

| Urban | 1140 (93.4) | 873 (93.3) | 267 (94) | |

| Unknown | 46 (3.8) | 38 (4.1) | 8 (2.8) | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Charlson/Deyo score (SD)c | .86 | |||

| 0 | 1014 (83.1) | 777 (83) | 237 (83.5) | |

| >1 | 206 (16.9) | 159 (17) | 47 (16.5) | |

| Tumor characteristics | ||||

| Tumor size, cm | .46 | |||

| <2 | 206 (16.9) | 151 (16.1) | 55 (19.4) | |

| 2-5 | 715 (58.6) | 549 (58.7) | 166 (58.5) | |

| >5 | 272 (22.3) | 216 (23.1) | 56 (19.7) | |

| Missing | 27 (2.2) | 20 (2.1) | 7 (2.5) | |

| Nodal status | .40 | |||

| Negative | 258 (21.1) | 198 (21.2) | 60 (21.1) | |

| 1-3 positive | 382 (31.3) | 305 (32.6) | 77 (27.1) | |

| 4-9 positive | 310 (25.4) | 229 (24.5) | 81 (28.5) | |

| >9 positive | 246 (20.2) | 187 (20) | 59 (20.8) | |

| Uncertain/unsampled/unknown | 24 (2.0) | 17 (1.8) | 7 (2.5) | |

| Histology | .06 | |||

| Ductal | 1034 (84.8) | 781 (83.4) | 253 (89.1) | |

| Lobular | 109 (8.9) | 89 (9.5) | 20 (7.0) | |

| Other | 77 (6.3) | 66 (7.1) | 11 (3.9) | |

| Tumor subtype group | .65 | |||

| ER+ or PR+, HER2- | 610 (50) | 469 (50.1) | 141 (49.6) | |

| ER- and PR-, HER2- | 338 (27.7) | 254 (27.1) | 84 (29.6) | |

| HER2+ | 272 (22.3) | 213 (22.8) | 59 (20.8) | |

| Chemotherapy at diagnosis | .59 | |||

| No | 210 (17.2) | 165 (17.6) | 45 (15.8) | |

| Yes | 1002 (82.1) | 764 (81.6) | 238 (83.8) | |

| Unknown | 8 (0.7) | 7 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | |

| HER2 targeted therapy at diagnosisd | .70 | |||

| No | 1074 (88) | 820 (87.6) | 254 (89.4) | |

| Yes | 128 (10.5) | 102 (10.9) | 26 (9.2) | |

| Unknown | 18 (1.5) | 14 (1.5) | 4 (1.4) | |

| Endocrine therapy at diagnosisd | .54 | |||

| No | 518 (42.5) | 401 (42.8) | 117 (41.2) | |

| Yes | 677 (55.5) | 518 (55.3) | 159 (56.0) | |

| Unknown | 25 (2.0) | 17 (1.8) | 8 (2.8) | |

| Surgery type and radiation therapy | .06 | |||

| Breast-conserving surgery alone | 346 (28.4) | 279 (29.8) | 67 (23.6) | |

| Breast-conserving surgery with radiation | 43 (3.5) | 35 (3.7) | 8 (2.8) | |

| Mastectomy alone | 538 (44.1) | 392 (41.9) | 146 (51.4) | |

| Mastectomy with radiation | 284 (23.3) | 224 (23.9) | 60 (21.1) | |

| Unknown | 9 (0.7) | 6 (0.6) | 3 (1.1) | |

| Facility type | .04 | |||

| Community cancer program/other | 331 (27.1) | 272 (29.1) | 59 (20.8) | |

| Comprehensive community cancer program | 655 (53.7) | 489 (52.2) | 166 (58.5) | |

| Academic/research program | 232 (19) | 174 (18.6) | 58 (20.4) | |

| Other | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.4) |

P values were determined using χ2 test for categorical variables. ER = estrogen receptor; PR = progesterone receptor; HER2 = Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2.

Medicare and other government includes Medicare with or without supplement, Tricare, military, Veterans Affairs, or Indian or Public Health Service.

Charlson-Deyo scores are summed scores for each comorbidity included in the Charlson comorbidity index and grouped to 0 or 1 or more based on the distribution of counts. A higher score is associated with a greater number of comorbid conditions.

Estimates reflect use of HER2-targeted therapy and endocrine therapy at the time of diagnosis across the full sample of patients irrespective of ER, PR, or HER2 status.

Quality Assurance

Pilot Study

Prior to the study, procedures were piloted at 18 CoC facilities with 180 randomly sampled patients (10 per facility). The pilot included breast cancer gene mutation, family history, and smoking as these are critically important prognostic factors. These factors could not be consistently identified in medical records and therefore were not included further.

Reliability Study

A feasibility study tested whether registrars could abstract imaging intent reliably and has been published elsewhere (21). In brief, patients who receive care at multiple CoC facilities have data submitted from each facility where they receive care. We leveraged this duplication to assess abstraction reliability for a random 5% sample. The observed percent agreement for surveillance vs symptom or follow-up advanced imaging was 79.4% (expected = 50%), and the kappa was 0.6 (z = 11.9, P < .001), indicating moderate agreement. It is important to note that record availability may have varied between institutions, therefore this represents a lower limit.

Statistical Analysis

Sociodemographic, tumor, and treatment factors were described for the overall cohort and for patients with distant recurrence. Characteristics between the asymptomatic imaging and sign and/or symptom detected recurrence groups were compared, using t tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables.

The primary analysis assessed survival differences within 5 years based on mode of recurrence detection (asymptomatic imaging vs sign and/or symptom). The relationship between how recurrence was detected and days from initial cancer diagnosis to death was assessed using unweighted and propensity score-weighted multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models stratified by tumor subtype (ER+ or PR+, HER2-; triple negative; HER2+) (15). Analyses were repeated with 9-year survival. Weighted median survival time and their confidence interval values at 3, 5, and 9 years were based on weighted Kaplan-Meier estimation, with each observation weighted by its standardized propensity score. The proportional hazards assumption was tested through graphical examination of Kaplan-Meier curves (no crossing) and log-log plots (approximately parallel straight lines).

Preliminary analyses suggested potential bias in who received asymptomatic imaging. To account for this, 2 propensity score weights were constructed. First, propensity models were constructed based on a patient’s receipt of asymptomatic systemic imaging in the first 3 years following diagnosis under the assumption that accounting for differences between patients who do vs do not receive asymptomatic systemic imaging best reflects the randomization point that would be used in a clinical trial (patient randomly assigned to routine surveillance systemic imaging vs standard of care). This approach is consistent with best practices for constructing propensity score models that include only pretreatment factors (24,25). Separate models were fit for each tumor subtype group to achieve covariate balance. A second set of propensity score weights was constructed based on how a patient’s distant recurrence was first detected (asymptomatic imaging vs patient and clinician detected signs and/or symptoms) to account for sociodemographic and clinical factor differences between these patient groups and to ensure consistent findings.

Propensity score models included the full set of baseline sociodemographic and tumor and treatment factors and were constructed using the approach outlined by Xu et al. (26) to obtain stabilized inverse propensity score weights. Stabilized inverse propensity weights were obtained by multiplying inverse propensity weights by the marginal probability of receiving the actual treatment received. Patients were censored at the time they were lost to follow-up or died. A P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant, and all tests were 2-sided.

Sensitivity analyses assessed the potential for length bias (fast growing tumors and aggressive cancers detected as interval cancers by signs and/or symptoms as opposed to asymptomatic imaging). As the potential for this bias would be greatest for the subgroup with the most aggressive disease (triple negative), models were re-estimated excluding the following: 1) patients who recurred with brain metastases; 2) patients not treated with systemic therapy at the time of distant recurrence; and 3) patients who recurred within 4 months of the start of surveillance. Analyses were conducted using SAS V9.4.

Results

There were 9560 women with locoregional breast cancer in the overall cohort with recurrence information (Table 1); 1220 recurrences were detected. The unadjusted 5-year distant recurrence rate was 12.8% (21.9% for patients with triple negative, 13.9% for HER2+, and 10.1% for ER+ or PR+, HER2- cancers).

Table 1.

Five-year distant recurrence by stage and tumor subtype groupa

| Tumor subtype group | Overall n/No. (%) |

Stage II n/No. (%) |

Stage III n/No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 1220/9560 (12.8) | 559/6787 (8.2) | 661/2773 (23.8) |

| ER+ or PR+, HER2- | 610/6052 (10.1) | 271/4369 (6.2) | 339/1683 (20.1) |

| ER- and PR-, HER2- | 338/1546 (21.9) | 178/1147 (15.5) | 160/399 (40.1) |

| HER2+ | 272/1962 (13.9) | 110/1271 (8.7) | 162/691 (23.4) |

ER = estrogen receptor; PR = progesterone receptor; HER2 = human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

Of women with distant recurrence, 78% were aged younger than 70 years, and 42% had government-provided insurance (Table 2). Recurrences were detected by signs and/or symptoms in 76.7% (936 of 1220) and asymptomatic imaging in 23.3% (284 of 1220). Of recurrences detected by signs and/or symptoms, 51.2% of HER2+ patients, 51.6% of triple-negative patients, and 36.5% of ER+ or PR +, HER2- patients were treated with systemic therapy (data not shown). The proportion receiving systemic therapy among patients diagnosed by asymptomatic systemic imaging was 54.2%, 59.5%, and 45.4%, respectively.

After covariate adjustment and propensity weighting accounting for a patient’s propensity to receive surveillance systemic imaging within 3 years of diagnosis, patients with asymptomatic as compared with sign and/or symptom detected recurrences had a statistically significantly lower risk of death at 5 and 9 years if triple negative (5-year hazard ratio [HR] = 0.66, 95% CI = 0.48 to 0.91; 9-year HR = 0.73, 95% CI = 0.54 to 0.99) or HER2+ (5-year HR = 0.40, 95% CI = 0.24 to 0.68; 9-year HR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.33 to 0.80) with no statistically significant association for ER+ or PR+, HER2- cancer (5-year HR = 1.22, 95% CI = 0.93 to 1.60; 9-year HR = 1.14, 95% CI = 0.91 to 1.44) (Table 3). This translated to an absolute between-group difference in weighted median survival of approximately 5 months for triple-negative and 12 months for HER2+ tumors (Table 4). Findings were consistent between unweighted and propensity score weighted models. Sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the potential for length bias (ie, patients with rapidly progressing disease disproportionately diagnosed on symptoms) in the subgroup with the most aggressive disease (triple negative) yielded a consistent pattern of findings after excluding 1) patients with brain metastasis (HR = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.45 to 0.89), 2) patients not treated with systemic therapy at the time of recurrence (HR = 0.51, 95% CI = 0.32 to 0.82), and 3) patients who recurred within 4 months of the start of surveillance (HR = 0.78, 95% CI = 0.54 to 1.11).

Table 3.

Unweighted and weighted association between asymptomatic vs symptom detected distant recurrences and time to death by molecular subtype risk group for women diagnosed with stage II-III breast cancer (n = 1220)

| Tumor subtype groupc | No.d | 5-year follow-up |

5-year follow-up |

Propensity weight based on receipt of surveillance systemic imaging within 3 years of diagnosisa |

Propensity weight based on how recurrences detected (asymptomatic imaging vs signs and/or symptoms)b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-year follow-up |

5-year follow-up |

9-year follow-up |

5-year follow-up |

9-year follow-up |

||||

| Unweighted HR (95% CI) | Unweighted, covariatese HR (95% CI) | Weighted, no covariates HR (95% CI) | Weighted, covariatese HR (95% CI) | Weighted, covariatese HR (95% CI) | Weighted, covariatese HR (95% CI) | Weighted, covariatese HR (95% CI) | ||

| ER+ or PR+, HER2- | 610 | 1.22 (0.96 to 1.55) | 1.17 (0.89 to 1.53) | 1.21 (0.93 to 1.56) | 1.22 (0.93 to 1.60) | 1.14 (0.91 to 1.44) | 1.14 (0.87 to1.48) | 1.12 (0.90 to 1.40) |

| ER- and PR-, HER2- | 338 | 0.68 (0.51 to 0.90)f | 0.64 (0.46 to 0.89)f | 0.74 (0.55 to 0.98)f | 0.66 (0.48 to 0.91)f | 0.73 (0.54 to 0.99)f | 0.64 (0.47 to 0.88)f | 0.71 (0.53 to 0.96)f |

| HER2+ | 272 | 0.64 (0.43 to 0.94)f | 0.42 (0.25 to 0.69)f | 0.63 (0.41 to 0.98)f | 0.4 (0.24 to 0.68)f | 0.51 (0.33 to 0.80)f | 0.56 (0.36 to 0.87)f | 0.65 (0.44 to 0.95)f |

Propensity weight constructed using full cohort of 10 076 patients. Adjusting for propensity to receive surveillance systemic imaging within 3 years of diagnosis.

Propensity weight constructed using cohort of patients with distant recurrence within 5 years of diagnosis (n = 1220). Adjusting for propensity to have recurrence detected by asymptomatic systemic imaging vs signs and/or symptoms.

ER = estrogen receptor; PR = progesterone receptor; HER2 = human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

Number of death events per person-year in each of the tumor subtype risk groups is as follows: 5-year asymptomatic imaging detected: ER+ or PR+, HER2- = 91 of 561.99 (0.16); ER- and PR-, HER2- = 62 of 333.79 (0.19); HER2+ = 31 of 252.15 (0.12); 5-year sign and/or symptom detected: ER+ or PR+, HER2- = 274 of 1978.43 (0.14); ER- and PR-, HER2- = 219 of 830.78 (0.26), HER2+ = 144 of 816.75 (0.18); 9 years: asymptomatic imaging detected: ER+ or PR+, HER2- = 121 of 643.87 (0.19); ER- and PR-, HER2- = 75 of 333.79 (0.22); HER2+ = 46 of 301.15 (0.15); 9 years sign and/or symptom detected: ER+ or PR+, HER2- = 404 of 2333.69 (0.17); ER- and PR-, HER2- = 238 of 830.78 (0.29); HER2+ = 178 of 951.37 (0.19).

Covariates in adjusted models include the following: age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, insurance, urban or rural, zip code level median household income (quartile) and median percent with high school degree (quartile), histology, nodal status, tumor size, chemotherapy, HER2 and endocrine therapy, surgery and radiation, facility type, and Charlson comorbid conditions.

Statistically significant differences based on Wald test, P < .05.

Table 4.

Percent of patients surviving until years 3, 5, and 9 and median survival for patients with distant recurrence, triple-negative, and HER2-positive stage II-III breast cancer, propensity weighted based on receipt of surveillance within 3 years of diagnosis

| Mode of recurrence detection for each tumor subtype group | No. | Surviving 3 years, % | Surviving 5 years, % | Surviving 9 years, % | Survival in monthsa, median (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER+ or PR+, HER2- | |||||

| Asymptomatic imaging | 141 | 73.7 | 39.3 | 11.1 | 50.2 (43.6 to 58.8) |

| Signs and/or symptoms | 469 | 77.4 | 45.3 | 10.5 | 58.2 (55.2 to 61.1) |

| ER- and PR-, HER2- | |||||

| Asymptomatic imaging | 84 | 54.2 | 24.6 | 8.9 | 39.0 (33.1 to 44.8) |

| Signs and/or symptoms | 254 | 45.3 | 16.2 | 6.5 | 33.7 (30.2 to 37.7) |

| HER2+ | |||||

| Asymptomatic imaging | 59 | 85.1 | 52.5 | 13.8 | 63.9 (49.4 to 72.1) |

| Signs and/or symptoms | 213 | 68.0 | 38.1 | 13.4 | 51.4 (44.2 to 58.2) |

Days converted to months assuming 30 days in each month. ER = estrogen receptor; PR = progesterone receptor; HER2 = human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

Discussion

This study demonstrates an association between asymptomatic detection of metastatic breast cancer by imaging and survival. This association was limited to women with triple-negative and HER2+ tumors and was not evident for women with ER+ or PR+, HER2- cancer. These results support a clinical trial examining the use of surveillance systemic imaging in these subgroups of women, providing additional support to the call for such a trial made in the 2016 Cochrane review (9).

Although this observational study is insufficient to change clinical practice given the potential for residual confounding, it makes several important contributions. It is the first large cohort study to test the possibility that surveillance imaging could offer a survival advantage in 30 years. It is possible the survival advantage observed is attributable to tumor biology. However, multiple analyses conducted to address possible sources of bias using multiple approaches to propensity weighting and findings were consistent. Second, the potential for lead time and length biases were reduced by anchoring survival time from the initial diagnosis date as opposed to recurrence detection date and conducting a series of sensitivity analyses removing from the analysis patients with more rapidly fatal disease. Robust results under varied conditions increase confidence in observational study findings and conclusions.

Breast cancer is no longer considered a single disease, and outcomes vary by tumor phenotype, primarily receptor status. Integration of receptor status into the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging guidelines in 2018 underscores the critical role tumor biology plays in recurrence and mortality risk (27). Consistent with prior investigations, this study demonstrated heightened recurrence and mortality risk for triple negative and HER2+ (15). The study builds on prior work by suggesting there may be a benefit to early distant recurrence detection for patients at highest risk of poor outcomes. These findings are novel, as prior research examining the role of surveillance imaging has not considered biologic markers (4-8). This is the first study to document a survival advantage for a subset of breast cancer patients that deserves further investigation under experimental conditions.

This study found no survival advantage with asymptomatic detection of distant recurrence for women with ER+ or PR+, HER2- disease, a population that comprises more than two-thirds of women diagnosed with locoregional breast cancer (15). This finding is consistent with results reported in prior randomized trials and suggests the majority of women diagnosed with stage II-III breast cancer would not benefit from surveillance systemic imaging during follow-up (4-8). This is important for 3 reasons. First, given the overwhelming number of ER+ or PR+, HER2- patients included in the prior trials that inform current guidelines, it is possible that any advantage among the minority of patients with a triple-negative or HER2+ cancer was masked. Second, it increases the feasibility of a future trial by narrowing the eligible study population to a smaller subset of patients, with shorter recurrence time frames. Finally, it supports the current approach of symptom-based surveillance for this large subset of breast cancer patients. Systemic surveillance testing and imaging for asymptomatic patients has been included as a Choosing Wisely target for overutilization. Our results provide evidence to support this for the majority of patients, while calling for further study of those at highest risk.

This study has several limitations. First, the study included 2006-2007 diagnoses to allow for the collection of 5-year follow-up for recurrence. HER2 status was not recorded consistently, and trastuzumab was not routinely administered for patients with HER2+ tumors during these years and, despite repeat abstraction of this information, it was missing for 7% of patients. Only 39% of the population of patients with HER2+ tumors who were sampled in 2006-2007 received HER2 targeted therapy at the time of initial diagnosis but likely did at the time of recurrence. This leads to an almost certain overestimation of the magnitude of the survival advantage observed for the HER2+ subgroup. Second, observational studies, even with propensity score adjustment, do not allow for the complete control of differences between asymptomatic and symptom-detected recurrences. A related concern is length bias, whereby biological differences between recurrences detected by asymptomatic imaging (ie, slower growing), may confer a survival advantage relative to symptom-detected recurrences. We addressed these limitations of observational studies by conducting a series of sensitivity analyses, including alternative propensity model specifications and restricting the analysis by site of recurrence and to patients who received treatment for their recurrence. Third, because of the need to analyze de-identified data, it was not possible to directly validate abstraction; however, the reliability study that compared patient records abstracted from 2 facilities by different registrars suggests abstracted data were reliable. Fourth, cancer-related survival was not available, though differences in overall survival were found. Fifth, it is important to emphasize that only a minority (12%) of patients in the study sample received regular asymptomatic systemic imaging over the follow-up period (as defined as 2 or more scans for surveillance of the same type) (21). This is why the analysis focused on the mode of distant recurrence detection and survival and not the relationship between receipt of routine surveillance systemic imaging and survival. Improved survival with distant recurrences detected on asymptomatic imaging is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the determination of effectiveness. Study findings should not be interpreted as supporting asymptomatic systemic imaging with regular periodicity without further evaluation under randomized conditions.

Among women with stage II-III breast cancer, detection of recurrence by asymptomatic systemic imaging as compared with signs and/or symptoms was associated with a statistically significantly lower risk of death for patients with triple-negative and HER2+ breast cancer but not ER+ or PR+, HER2- cancer. A randomized trial is needed to determine if surveillance with asymptomatic systemic imaging results in improved survival for triple-negative and/or HER2+ breast cancer; however, these results reinforce the current surveillance approach based on signs and/or symptoms for the majority of breast cancer patients.

Funding

This work was supported by the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) (Greenberg, contract number CE-1304-6543). This publication was further made possible by the University of Wisconsin Carbone Comprehensive Cancer Center Academic Oncologist Training Program (Neuman, NIH 5K12CA087718), the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Scholar Program (Neuman, NIH K12 HD055894), and a Clinical Translational Science Award (Ruddy, grant numbers UL1 TR000135, KL2TR000136-09) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Further support included the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health grant number U10CA180821 (to the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology).

Notes

Role of the funder: The Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, National Cancer Institute, and Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Disclosures: Dr Greenberg reported that she has received support from Johnson & Johnson for educational activities unrelated to the current project. No other disclosures were reported for the other authors. KJR, a JNCI Associate Editor and co-author on this article, was not involved in the editorial review or decision to publish this manuscript.

Author contributions: Conceptualization (JRS, HBN, MY, DJV, ESB, KJR, AHP, DS, SBE, EAJ, DPW, DPM, PAS, BDK, GJC, CCG); Data Curation (JRS, JH); Formal Analysis (YZ, MY); Funding Acquisition (CCG); Investigation (JRS, HBN, MY, DJV, YS, ESB, KJR, AHP, DS, SBE, EAJ, ABF, DPW, DPM, PAS, BDK, GJC, CCG); Methodology (MY, DJV, YS, YZ); Project Administration (JRS, ABF, CCG); Supervision (DPW, DPM, CCG); Validation (YZ, MY, DJV); Visualization (YZ); Writing—Original Draft (JRS); Writing—Review & Editing (JRS; HBN, MY, DJV, YS, ESB, KJR, AHP, DS, SBE, YZ, EAJ, JH, ABF, DPW, DPM, PAS, BDK, GJC, CCG).

Acknowledgements: The data used in the study are derived from a de-identified National Cancer Database file.

Disclaimers: The American College of Surgeons and the Commission on Cancer have not verified and are not responsible for the analytic or statistical methodology employed, or the conclusions drawn from these data by the investigator. Further, the contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute or National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Jessica R Schumacher, Department of Surgery, Wisconsin Surgical Outcomes Research Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA.

Heather B Neuman, Department of Surgery, Wisconsin Surgical Outcomes Research Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA.

Menggang Yu, Department of Biostatistics & Medical Informatics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA.

David J Vanness, Department of Health Policy and Administration, Penn State University, State College, PA, USA.

Yajuan Si, Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Elizabeth S Burnside, Department of Radiology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA.

Kathryn J Ruddy, Department of Oncology, Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Cancer Center, Rochester, MN, USA.

Ann H Partridge, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Deborah Schrag, Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, USA; Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Stephen B Edge, Department of Surgical Oncology, Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center, Buffalo, NY, USA.

Ying Zhang, Department of Biostatistics & Medical Informatics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA.

Elizabeth A Jacobs, Department of Medicine, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA.

Jeffrey Havlena, Department of Surgery, Wisconsin Surgical Outcomes Research Program, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA.

Amanda B Francescatti, Commission on Cancer, American College of Surgeons, Chicago, IL, USA.

David P Winchester, Commission on Cancer, American College of Surgeons, Chicago, IL, USA.

Daniel P McKellar, Commission on Cancer, American College of Surgeons, Chicago, IL, USA; Department of Surgery, Wright State University, Dayton, OH, USA.

Patricia A Spears, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

Benjamin D Kozower, Department of Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, USA.

George J Chang, Department of Colon and Rectal Surgery, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Caprice C Greenberg, Department of Surgery, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

for the Alliance ACS-CRP CCDR Breast Cancer Surveillance Working Group, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

for the Alliance ACS-CRP CCDR Breast Cancer Surveillance Working Group:

Karla Ballman, Patrick Gavin, Bettye Green, Jane Perlmutter, Elizabeth Berger, Rinaa Punglia, Ronald Chen, Nicole Brys, and Taiwo Adesoye

Data Availability

The data included in the current study is from the National Cancer Database, augmented by primary record abstraction by registrars at each site. The Data Use Agreement governing the use of these data specifies that the study PI is not to use or disclose the data beyond use for the approved study.

References

- 1. American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2017-2018. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Khatcheressian JL, Hurley P, Bantug E, et al. ; for the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Breast cancer follow-up and management after primary treatment: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(7):961-965. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gradishar WJ, Anderson BO, Balassanian R, et al. Invasive breast cancer version 1.2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2016;14(3):324-354. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2016.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. GIVIO Investigators. Impact of follow-up testing on survival and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients. A multicenter randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1994;271(20):1587-1592. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03510440047031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grunfeld E, Mant D, Yudkin P, et al. Routine follow up of breast cancer in primary care: randomised trial. BMJ. 1996;313(7058):665-669. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7058.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gulliford T, Opomu M, Wilson E, et al. Popularity of less frequent follow up for breast cancer in randomised study: initial findings from the hotline study. BMJ. 1997;314(7075):174-177. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7075.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rosselli Del Turco M, Palli D, Cariddi A, et al. Intensive diagnostic follow-up after treatment of primary breast cancer. A randomized trial. National Research Council Project on Breast Cancer follow-up. JAMA. 1994;271(20):1593-1597. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.20.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rojas MP, Telaro E, Russo A, et al. Follow-up strategies for women treated for early breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2005(1). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001768.pub2. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moschetti I, Cinquini M, Lambertini M, et al. Follow-up strategies for women treated for early breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(5). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001768.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Panageas KS, Sima CS, Liberman L, et al. Use of high technology imaging for surveillance of early stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131(2):663-670. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1773-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Winchester DP, et al. The National Cancer Data Base: a powerful initiative to improve cancer care in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(3):683-690. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9747-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Williams RT, Stewart AK, Winchester DP. Monitoring the delivery of cancer care: Commission on Cancer and National Cancer Database. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2012;21(3):377-388, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Winchester DP, Stewart AK, Bura C, et al. The National Cancer Data Base: a clinical surveillance and quality improvement tool. J Surg Oncol. 2004;85(1):1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Commission on Cancer. Facility Oncology Registry Data Standards. Chicago, IL: Commission on Cancer; 2013. doi: 10.1002/jso.10320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cossetti RJ, Tyldesley SK, Speers CH, et al. Comparison of breast cancer recurrence and outcome patterns between patients treated from 1986 to 1992 and from 2004 to 2008. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(1):65-73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iqbal J, Ginsburg O, Rochon PA, et al. Differences in breast cancer stage at diagnosis and cancer-specific survival by race and ethnicity in the United States. JAMA. 2015;313(2):165-173. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. In H, Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, et al. Cancer recurrence: an important but missing variable in national cancer registries. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(5):1520-1529. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3516-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grunfeld E, Hodgson DC, Del Giudice ME, et al. Population-based longitudinal study of follow-up care for breast cancer survivors. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6(4):174-181. doi: 10.1200/JOP.200009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hahn EE, Hays RD, Kahn KL, et al. Use of imaging and biomarker tests for posttreatment care of early-stage breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2013;119(24):4316-4324. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Geurts SM, de Vegt F, Siesling S, et al. Pattern of follow-up care and early relapse detection in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;136(3):859-868. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2297-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schumacher JR, Neuman HB, Chang GJ, et al. ; for the Alliance ACS-CRP CCDR Breast Cancer Surveillance Working Group. A national study of the use of asymptomatic systemic imaging for surveillance following breast cancer treatment (AFT-01). Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25(9):2587-2595. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6496-4. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6496-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41-55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/70.1.41. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rosenbaum PR. The consequences of adjustment for a concomitant variable that has been affected by the treatment. J Roy Stat Soc Ser A-Stat Soc. 1984;147(5):656-666. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/2981697. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xu S, Ross C, Raebel MA, et al. Use of stabilized inverse propensity scores as weights to directly estimate relative risk and its confidence intervals. Value Health. 2010;13(2):273-277. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00671.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Giuliano AE, Connolly JL, Edge SB, et al. Breast cancer–major changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(4):290-303. doi: 10.3322/caac.21393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data included in the current study is from the National Cancer Database, augmented by primary record abstraction by registrars at each site. The Data Use Agreement governing the use of these data specifies that the study PI is not to use or disclose the data beyond use for the approved study.