Abstract

That gene transfer to plant cells is a temperature-sensitive process has been known for more than 50 years. Previous work indicated that this sensitivity results from the inability to assemble a functional T pilus required for T-DNA and protein transfer to recipient cells. The studies reported here extend these observations and more clearly define the molecular basis of this assembly and transfer defect. T-pilus assembly and virulence protein accumulation were monitored in Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58 at different temperatures ranging from 20°C to growth-inhibitory 37°C. Incubation at 28°C but not at 26°C strongly inhibited extracellular assembly of the major T-pilus component VirB2 as well as of pilus-associated protein VirB5, and the highest amounts of T pili were detected at 20°C. Analysis of temperature effects on the cell-bound virulence machinery revealed three classes of virulence proteins. Whereas class I proteins (VirB2, VirB7, VirB9, and VirB10) were readily detected at 28°C, class II proteins (VirB1, VirB4, VirB5, VirB6, VirB8, VirB11, VirD2, and VirE2) were only detected after cell growth below 26°C. Significant levels of class III proteins (VirB3 and VirD4) were only detected at 20°C and not at higher temperatures. Shift of virulence-induced agrobacteria from 20 to 28 or 37°C had no immediate effect on cell-bound T pili or on stability of most virulence proteins. However, the temperature shift caused a rapid decrease in the amount of cell-bound VirB3 and VirD4, and VirB4 and VirB11 levels decreased next. To assess whether destabilization of virulence proteins constitutes a general phenomenon, levels of virulence proteins and of extracellular T pili were monitored in different A. tumefaciens and Agrobacterium vitis strains grown at 20 and 28°C. Levels of many virulence proteins were strongly reduced at 28°C compared to 20°C, and T-pilus assembly did not occur in all strains except “temperature-resistant” Ach5 and Chry5. Virulence protein levels correlated well with bacterial virulence at elevated temperature, suggesting that degradation of a limited set of virulence proteins accounts for the temperature sensitivity of gene transfer to plants.

Growth temperature affects the virulence functions of many pathogenic bacteria. In concert with other stimuli, such as pH and ionic composition of the external medium, temperature shifts modulate virulence gene expression in human and animal pathogenic bacteria, reflecting their adaptation to the host environment (2, 14, 21, 28, 36). In the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae, a decrease in growth temperature positively correlates with increased virulence gene expression (43, 44). In most cases, regulation occurs at the level of gene expression by modulation of the activity of specific two-component regulatory systems or DNA binding of global regulators such as HN-S.

Studies early in the last century revealed that tumor formation on wounded and Agrobacterium tumefaciens-infected plants was strongly reduced at temperatures above 29°C compared to 22°C (37). This temperature effect was later shown to occur by inactivation of the tumor-inducing principle in A. tumefaciens and not by effects on the host plant (8). Based on studies of tumor formation at different temperatures, Armin Braun speculated that denaturation of a protein complex may account for this phenomenon (7).

Great efforts have been undertaken to understand the mechanism of gene transfer to plants by A. tumefaciens and to improve its efficiency for applications in research and biotechnology (20, 49). However, until recently, the molecular basis of temperature sensitivity remained obscure, and in spite of early work showing low efficiency of plant transformation at this temperature, many studies were performed in liquid-grown cells at 28°C. Virulence gene induction is triggered by phenylpropanoids and sugars in the acidic exudates of wounded plants via the VirA-VirG two-component system (47). This process proved to be functional at temperatures up to 28°C, showing that reduced efficiency of plant transformation does not rely on regulation at the level of transcription below this temperature (22).

Gene transfer to plants is mediated by a type IV secretion machinery of 12 membrane-bound proteins (VirB1 to VirB11 and VirD4) supposed to span both the inner and outer membrane (10, 11, 27, 50). VirB2 through VirB11 are absolutely required for gene transfer and efficient assembly of extracellular T pili, and VirB1, which may locally lyse the murein cell wall, is an efficiency factor for transmembrane assembly of the complex (29, 33). VirD4 is not required for T-pilus assembly, but it likely plays a role as coupling protein for the transfer of virulence factors (VirD2, VirE2, VirF, and T-DNA) to the membrane-bound components of the type IV transporter (9, 18). This machinery also directs low-efficiency conjugative transfer of IncQ plasmids between bacteria (5). IncQ plasmid transfer is negatively affected at elevated temperatures, suggesting that the type IV transporter may be destabilized (17). This hypothesis was further supported by analysis of VirB9 and VirB10 and their complexes in liquid-grown cells at different temperatures, showing destabilization of VirB10 and reduced abundance of its complexes (3). T-pilus formation and extracellular assembly of major component VirB2 were reduced after incubation of A. tumefaciens on agar plates at 28°C compared to the optimal temperature of 20°C (16, 26).

We recently showed that levels of most VirB proteins and of VirD4 were strongly reduced in strain C58 after induction in liquid culture at 28°C compared to induction under optimized conditions at 20°C on agar plates (19). This analysis was refined here by comparison of T-pilus formation as well as virulence protein accumulation in various A. tumefaciens and A. vitis strains grown on agar plates at different temperatures. This revealed substantial differences in the abundance of virulence proteins and shift of agrobacteria from 20 to 28°C or 37°C led to degradation of a specific subset of virulence proteins. Content of virulence proteins was shown to correlate with bacterial virulence at different temperatures, suggesting that stability of the type IV transporter may determine the temperature range of gene transfer to plants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell growth and fractionation.

Agrobacterium overnight cultures in YEB medium were inoculated to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 in liquid AB medium and grown for 5 h at 20°C, followed by plating of 1 ml per large (15-cm square) petri dish and further incubation at different temperatures for 3 days (19). For T-pilus isolation, cells were washed from the plates with 10 ml of 50 mM Na-K-phosphate buffer (pH 5.5). The cells were sedimented and resuspended in 1 ml of 50 mM Na-K-phosphate buffer, followed by shearing through a 26-gauge needle 10 times to remove surface structures such as flagella and pili from the cells. Pilus-enriched fractions were obtained by differential centrifugation as described (39). For shift experiments, cells were grown on AB agar plates as above for 3 days at 20°C, followed by further incubation at 20°C or transfer to 28 or 37°C, isolation of T pili, and preparation of cell lysates.

Protein analysis.

For protein analysis, cells were washed from the plates with 10 ml of 50 mM Na-K-phosphate buffer, followed by sedimentation of 1-ml aliquots by centrifugation. Cells from 1-ml aliquots were suspended in Laemmli sample buffer in a volume according to the optical density of the sample (microliters of sample buffer = OD600 × 50). To avoid formation of high-molecular-mass aggregates, lysates for analysis of VirB6 and VirD4 content were incubated at 37°C (19); cell lysates for analysis of all other proteins were generated by incubation at 100°C for 5 min. Then 8 μl of the lysates were applied to gel lanes, followed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (25, 38) and silver staining or Western blotting and detection. Virulence protein-specific antisera were described before (19, 41) or newly generated in our lab by immunization of rabbits with purified inclusion bodies of VirD2 and VirE2. β-Glucuronidase-specific antiserum (Molecular Probes) was used in a 1:2,000 dilution as suggested by the manufacturer.

DNA modification procedures.

Standard protocols were used for DNA manipulations (30) using enzymes from MBI Fermentas and New England Biolabs. Sequencing was performed on an ABI Prism 377 sequencer.

A fusion of the β-glucuronidase-coding gusA gene to the virE2 promoter was generated as follows. A 1.9-kb NcoI/BglII gusA fragment was isolated from pRTL2SG-Nla/ΔB+K, and single-stranded overhangs were removed by mung bean nuclease treatment. A 1.1-kb NdeI/EcoRI fragment containing the virE promoter, virE1, and part of virE2 was isolated from pGV0361, and overhanging ends were filled in with Klenow enzyme and ligated to pUC18 which had been linearized with BamHI followed by filling-in of sticky ends. The resulting vector, pUC18virE2, was linearized with BamHI, and overhanging ends were filled in with Klenow enzyme followed by ligation to the gusA fragment. This generated a translational fusion of gusA to the start codon of virE2 at the acetosyringone-inducible promoter, which was introduced into the Ti plasmid of nopaline strain C58 by double recombination essentially as described (6), resulting in strain CB3002. Acetosyringone-inducible β-glucuronidase activity was measured to monitor VirA/VirG-mediated virulence gene expression.

Tumor formation assay.

Agrobacterium overnight cultures in YEB medium were inoculated to an OD600 of 0.1 in liquid AB medium and grown for 5 h at 20°C, followed by dilution to final OD600 values of 0.2, 0.02, and 0.002 in AB medium. Kalanchoë diagremontiana plants were wounded with a sterile needle, and 10 μl was applied to the wound, followed by incubation at 20 or 28°C for 1 week and further incubation at 20°C. Tumor formation was scored after 2, 3, and 4 weeks.

RESULTS

Elevated temperature inhibits T-pilus formation.

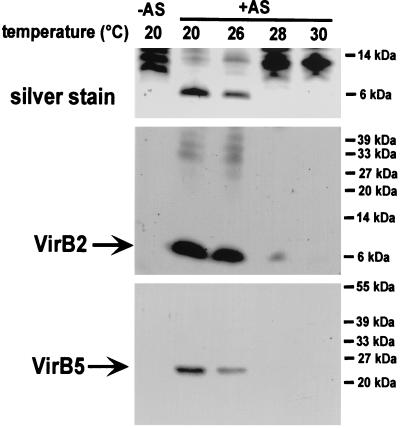

To assess the effect of temperature on the type IV secretion machinery, formation of extracellular T pili was analyzed after virulence gene induction of A. tumefaciens wild-type C58 on agar medium at different temperatures (39). Analysis of T pili released from cells grown at 20°C by shearing revealed maximal extracellular accumulation of the major T-pilus component VirB2 and the pilus-associated protein VirB5, whereas growth at 26°C led to a notable reduction, but T pili were still isolated (Fig. 1). Only marginal amounts of extracellular VirB2 were recovered from cells grown at 28°C, and at 30°C, neither T-pilus component was detected (Fig. 1). These results extended earlier studies (26) by inclusion of T-pilus-associated VirB5, showing that assembly of major and putative minor pilus components were similarly affected. In addition, we showed that the relatively minor temperature difference between 26 and 28°C had a major effect on T-pilus assembly, which is in good accord with earlier results using IncQ plasmid transfer to measure virulence functions (17).

FIG. 1.

Growth temperature affects T-pilus production. T pili were isolated from wild-type strain C58 after growth under non-virulence-inducing conditions (−AS) or virulence-inducing conditions (+AS) on AB minimal medium plates at the given temperatures by shearing of cells and high-speed centrifugation. Pilus fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining or Western blotting and detection with specific antisera as indicated. Molecular masses of reference proteins are indicated on the right.

Elevated temperature differentially affects virulence protein accumulation.

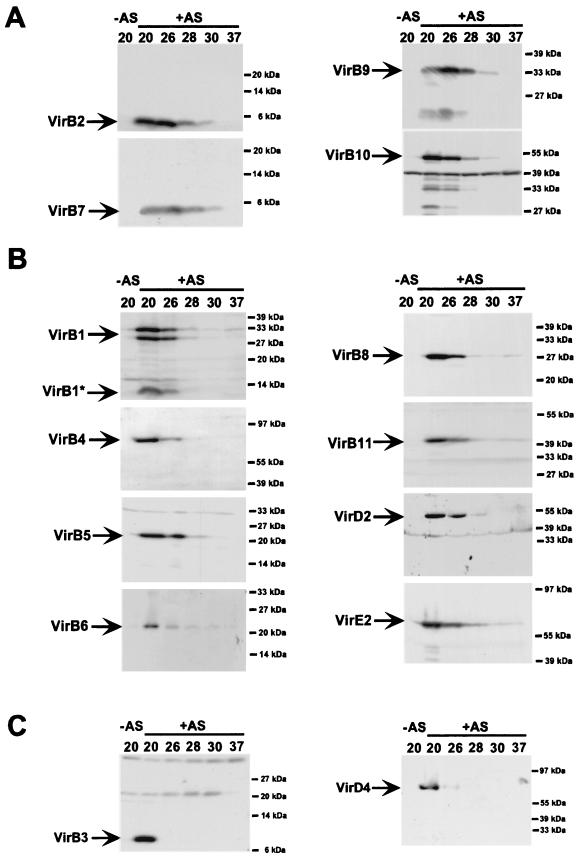

Analysis of extracellular T-pilus assembly probably reflects functionality of the transmembrane protein complex, but it does not necessarily correlate with levels of cell-bound virulence proteins. Lysates from cells grown on agar plates at different temperatures (20, 26, 28, 30, and 37°C) were analyzed with antisera specific for all components of the transmembrane complex (VirB1 through VirB11 and VirD4) as well as the transported substrates VirD2 and VirE2. Based on their accumulation at different temperatures, virulence proteins were assigned to three categories. VirB2, VirB7, VirB9, and VirB10 accumulated to easily detectable amounts even at 28°C, which is nonpermissive for T-pilus assembly, and were designated class I proteins (Fig. 2A). VirB1, VirB4, VirB5, VirB6, VirB8, VirB11, VirD2, and VirE2 were detected after cell growth at temperatures up to 26°C, but levels were strongly reduced or they were not detected at higher temperatures; they were designated class II proteins (Fig. 2B). VirB3 and VirD4, which accumulated to easily detectable amounts only in 20°C-grown cells, were designated class III proteins (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Effect of growth temperature on virulence protein accumulation in strain C58. Wild-type strain C58 was grown under non-virulence-inducing conditions (−AS) or virulence-inducing conditions (+AS) on AB minimal medium plates at the given temperatures, followed by SDS-PAGE, Western blotting and detection with specific antisera as indicated. (A) Class I virulence proteins detected in the cells at elevated temperature. (B) Class II virulence proteins detected in reduced amounts in the cells at elevated temperature. (C) Class III virulence proteins not detected in the cells at elevated temperatures. Molecular masses of reference proteins are indicated on the right.

Temperatures up to 28°C do not affect virulence gene expression.

Earlier reports showed that temperatures up to 28°C do not negatively affect virulence gene expression in A. tumefaciens octopine strains (22). As a control for our induction conditions, we cultivated octopine strain A358 in the presence of acetosyringone at different temperatures and determined acetosyringone-inducible β-galactosidase activity driven from fusion of the lacZ gene to the virE2 promoter. As in previous studies, we did not measure notable differences in acetosyringone-dependent β-galactosidase activities between cells grown at 20 and 28°C, and there was a sharp decrease above 30°C (17, 22), showing that our growth conditions are similar to those used by others.

To monitor acetosyringone-dependent gene expression in nopaline strain C58, we cultivated its derivative CB3002, which carries a translational virE2::gusA fusion, in the presence of acetosyringone at different temperatures as above. Analysis of cell lysates with GusA-specific antiserum showed similar amounts of the protein in cells grown at temperatures between 20 and 28°C (not shown), suggesting that variations in this range do not affect virulence gene regulation in nopaline strain C58. Therefore, other reasons likely account for the reduced accumulation of virulence proteins at elevated temperatures.

Shift to assembly-nonpermissive temperature does not affect T-pilus stability.

Elevated temperatures may result in degradation of a subset of proteins and thereby prevent stable assembly of the type IV transporter. Alternatively, the transmembrane complex may dissociate at elevated temperature, leading to degradation of its components. To differentiate between these two possibilities, temperature shift experiments were performed.

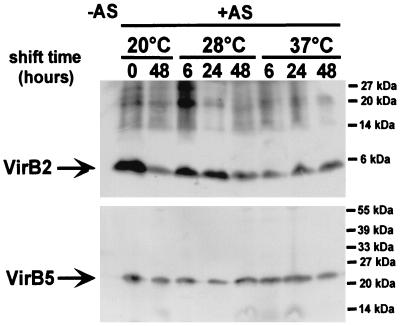

A. tumefaciens strain C58 was cultivated on agar plates for 3 days at 20°C, followed by further incubation at 20°C or a shift to 28 or 37°C, and T-pilus isolation was performed after 6, 24, and 48 h. Analysis with VirB2- and VirB5-specific antisera showed that a shift to 28 or 37°C for up to 48 h did not affect association of VirB2 and VirB5 with extracellular high-molecular-mass structures isolated by shearing and ultracentrifugation (Fig. 3). Thus, T pili were not affected by the shift to temperatures nonpermissive for pilus assembly, indicating that pilus structure and their attachment to the cell are not inherently unstable under these conditions.

FIG. 3.

Temperature shift does not affect T-pilus stability. Wild-type strain C58 was grown under non-virulence-inducing conditions (−AS) or virulence-inducing conditions (+AS) on AB minimal medium plates at 20°C for 3 days, followed by further incubation at 20°C or a shift to 28 or 37°C for the times indicated. T pili were isolated at the given times, and pilus fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting and detection with VirB2- and VirB5-specific antisera. Molecular masses of reference proteins are indicated on the right.

Specific degradation of virulence proteins after temperature shift.

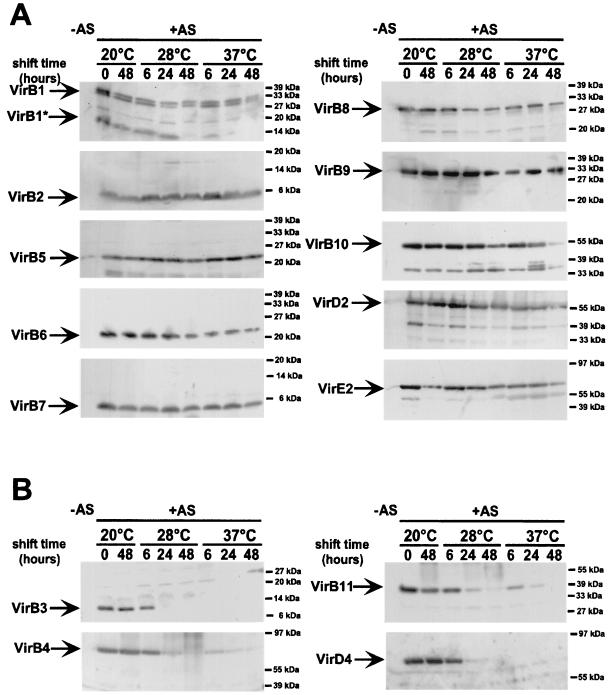

Levels of cell-bound virulence proteins were also compared after a temperature shift as described above to determine their stability in preformed complexes. Most virulence proteins were stable or only modestly degraded after a shift to 28 or 37°C, and the amounts of VirB10 and VirE2 declined only after extended incubation at 37°C (Fig. 4A). In contrast, VirB4 and VirB11 were detectable 6 h after a shift to 28°C, but the levels decreased rapidly below the detection limit upon further incubation (Fig. 4B). The instability was even more pronounced after a shift to 37°C, where strongly reduced levels were observed after 6 h. Temperature shift exerted even more dramatic effects on cell-bound VirB3 and VirD4, which were only detected up until 6 h after being shifted to 28°C but not after being shifted to 37°C (Fig. 4B). As both proteins were not detected after prolonged incubation at a temperature nonpermissive for T-pilus assembly, their degradation might be a key event for the temperature sensitivity of the type IV transporter.

FIG. 4.

Effect of temperature shift on virulence protein levels. Wild-type strain C58 was grown under non-virulence-inducing conditions (−AS) or virulence-inducing conditions (+AS) on AB minimal medium plates at 20°C for 3 days, followed by further incubation at 20°C or a shift to 28 or 37°C for the times indicated. Vir proteins were detected in cell lysates after SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with specific antisera as indicated. (A) Shift-resistant virulence proteins not affected or only modestly degraded after the temperature shift. (B) Shift-sensitive virulence proteins rapidly degraded in the cells after the temperature shift. Molecular masses of reference proteins are indicated on the right.

Elevated temperature affects virulence protein accumulation in different Agrobacterium strains.

To assess whether the reduced stability of virulence proteins at elevated temperature is a general feature of the genus, different agrobacteria were analyzed next. Six A. tumefaciens and eight A. vitis strains (Table 1) were grown on acidic AB agar plates at 20°C, and T pili were isolated by shearing of plate-grown cells through a 26-gauge needle and differential centrifugation (39). Fractions containing extracellular high-molecular-mass structures were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting (25, 38). Major T-pilus component VirB2 was detected by silver staining and Western blotting in samples from all A. tumefaciens strains grown under virulence-inducing conditions, suggesting the formation of T pili similar to strain C58 (not shown). In contrast, neither silver staining nor Western blotting with VirB2- or VirB5-specific antisera gave evidence for the formation of T pili by A. vitis strains (not shown).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| A. tumefaciens | ||

| C58 | A136, pTiC58, nopaline Ti plasmid | 45 |

| CB3002 | A136, pTiC58 (virE2::gusA) | This work |

| A208 | A136, pTiT37, nopaline Ti plasmid | S. Pueppke |

| A281 | A136, pTiBo542, succinamopine Ti plasmid | S. Pueppke |

| Ach5 | Achillea millefolium isolate, octopine Ti plasmid | S. Pueppke |

| A348 | A136, TiA6NC, octopine Ti plasmid | P. Christie |

| A358 | A136, TiA6NC virETn3HoHo1 | 40 |

| Chry5 | Chrysanthemum morifolium isolate, succinamopine Ti plasmid | S. Pueppke |

| A. vitis | ||

| NWW432 | Vitis vinifera isolate | E. Zyprian |

| VS-1 | Vitis vinifera isolate | E. Zyprian |

| NWF408 | Vitis vinifera isolate | E. Zyprian |

| AB-3 | Vitis vinifera isolate, octopine/cucumopine Ti plasmid | E. Zyprian |

| Tm-4 | Vitis vinifera isolate, octopine/cucumopine Ti plasmid | E. Zyprian |

| AT-1 | Vitis vinifera isolate, nopaline Ti plasmid | E. Zyprian |

| S-4 | Vitis vinifera isolate, vitopine Ti plasmid | E. Zyprian |

| LMG 207 | Vitis vinifera isolate | E. Zyprian |

| E. coli | ||

| JM109 | Cloning host | 48 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC18 | Cloning vector | 48 |

| pGVO361 | pBR322 carrying virD, virE, and part of virC from pTiC58 | 13 |

| pRTL2SG-NlaΔB+K | 35S promoter gusA gene for generation of gene fusions | J. Carrington |

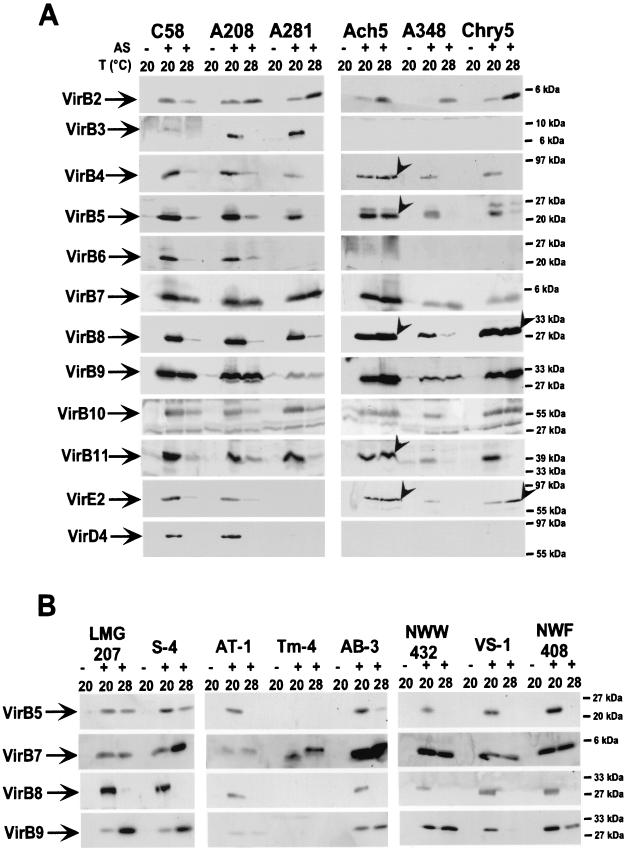

Since T-pilus formation indicated the presence of a functional type IV transporter in all A. tumefaciens strains under standard induction conditions, we next assessed whether temperature affects virulence protein levels. Cells were grown under virulence gene-inducing conditions at 20 and 28°C, and lysates were analyzed with C58 virulence protein-specific antiserum. Similar to earlier observations in strain C58, class I virulence proteins (VirB2, VirB7, VirB9, and VirB10) were detected at both temperatures in A. tumefaciens strains A208, A281, and A348 (Fig. 5A). Also, levels of VirB3, VirB4, VirB5, VirB6, VirB8, VirB11, VirD4, and VirE2 (class II and class III proteins) were strongly reduced at 28°C compared to 20°C in these strains (Fig. 5A). In contrast, all virulence proteins detected were present in equal amounts at 28°C as well as at 20°C in strain Ach5 (Fig. 5A). More virulence proteins were detected at 28°C in strain Chry5 than in C58 (VirB8, VirE2). However, others were not detected at 28°C (VirB4 and VirB11), and results varied between experiments, suggesting an intermediate phenotype concerning the stability of virulence proteins at 28°C. This may be due to minor variations in growth temperature in different experiments, which could have large effects on protein stability.

FIG. 5.

Effect of temperature shift on virulence protein levels in different Agrobacterium species. Strains were grown on AB minimal medium plates under non-virulence-inducing conditions (−AS) or virulence-inducing conditions (+AS) at the given temperatures followed by SDS-PAGE, Western blotting, and detection with specific antisera as indicated. (A) Comparison of virulence proteins in lysates from A. tumefaciens cells grown at 20 versus 28°C. (B) Virulence proteins from A. vitis. Arrowheads indicate virulence proteins detected in equal amounts at 28 and 20°C in strains Ach5 and Chry5. Molecular masses of reference proteins are shown on the right.

C58 protein-specific antiserum detected only a limited number of virulence proteins in A. vitis strains. This suggests either larger evolutionary divergence of the genes or weak induction of the virulence genes on a medium optimized for A. tumefaciens. Typical of class I proteins, VirB7 and VirB9 were present at both temperatures. In contrast, VirB8 levels were strongly reduced in all and VirB5 levels in most A. vitis strains at 28°C, similar to class II proteins in A. tumefaciens (Fig. 5B).

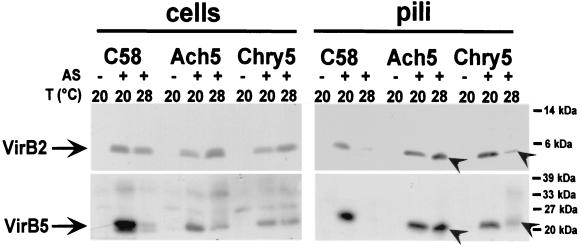

Pilus assembly correlates with virulence protein accumulation at 28°C in strain Ach5.

Antisera generated with virulence proteins from A. tumefaciens strain C58 did not detect VirB3 and VirD4 in most strains. These proteins were previously identified as the most “temperature-sensitive” class III components of the C58 type IV transporter. They could not be detected in “temperature-resistant” strains Ach5 and Chry5, and therefore we chose an indirect method to determine their presence in the cell. Since VirB3 is essential for T-pilus formation (6, 23), we determined the assembly of VirB2 and VirB5 in high-molecular-mass extracellular structures in cells grown at 20 and 28°C to assess the functionality of the type IV transporter under these conditions. Similar to strain C58, A208, A281, and A348 did not form T pili at 28°C (not shown). In contrast, extracellular VirB2 and VirB5 were easily detected in T-pilus fractions of strain Ach5 grown at 28°C (Fig. 6). Both pilus components were also detected in fractions containing extracellular high-molecular-mass structures from strain Chry5, albeit at strongly reduced levels, which is in accord with its intermediate temperature resistance phenotype (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

T-pilus formation of temperature-resistant strains. Strains were grown under non-virulence-inducing conditions (−AS) or virulence-inducing conditions (+AS) on AB minimal medium plates for 3 days at 20 or 28°C. Proteins from cell lysates and extracellular T-pilus fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting and detection with VirB2- and VirB5-specific antisera. Arrowheads indicate VirB2 and VirB5 in pilus fractions at 28°C. Molecular masses of reference proteins are shown on the right.

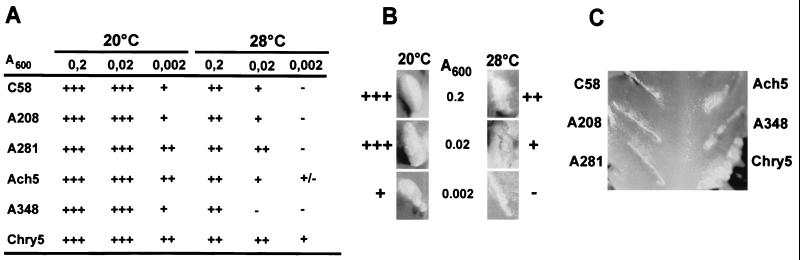

Elevated temperature strongly inhibits virulence.

To assess whether the reduced virulence protein accumulation and the efficiency of T-complex transfer are correlated, different dilutions of strains C58, A208, A281, Ach5, A348, and Chry5 grown in AB minimal medium were applied to freshly wounded K. diagremontiana plants and incubated at 20 or 28°C for 1 week. DNA transfer occurs during that period, and plants were then transferred to 20°C to ensure similar growth conditions. Tumor formation was monitored over a period of several weeks.

Infection with a high dose of bacteria (A600 = 0.2) led to tumor formation irrespective of the infection temperature, but the size of tumors incited at 28°C was reduced (Fig. 7A and 7B). Markedly reduced tumor size at 28°C was observed after a 10-fold reduction of the infectious dose, whereas no difference was observed at 20°C. When 100-fold-diluted cultures were used, tumors occurred with some delay, and their size was reduced after infection at 20°C, indicating that limiting amounts of bacteria were used for the experiment. This allowed more quantitative assessment of transformation efficiency. At 28°C, tumor formation was not observed after infection with 100-fold-diluted cultures of strains C58, A208, A281, and A348, but Ach5 and Chry5 reproducibly incited tumors (Fig. 7A and 7C). This result correlates well with observations made on T-pilus formation and stability of virulence proteins, showing that determination of virulence protein accumulation can be used to monitor functionality of the type IV transporter.

FIG. 7.

Infection temperature determines tumor formation efficiency. Cells were diluted to the optical densities indicated, followed by infection of wounded K. diagremontiana at 20 or 28°C. (A) Tumor formation was monitored for several weeks in four independent experiments, and representative results are shown (+++, strong tumor formation; ++, intermediate tumor formation; +, weak tumor formation; −, no tumors). (B) Tumor formation after infection with different dilutions of strain C58. (C) Tumor formation after infection at 28°C with the lowest infectious dose.

DISCUSSION

The present report constitutes the first comparative analysis of components of the type IV transporter for gene transfer to plants in a wide variety of agrobacteria. Ti plasmids from the six A. tumefaciens and eight A. vitis strains analyzed here were previously characterized to some extent at the DNA level, but inducibility of virulence genes by acetosyringone and production of virulence proteins were not analyzed in most cases (24, 35, 46). Antisera raised by immunization with C58-specific proteins allowed the detection of most virulence proteins in the acetosyringone-induced A. tumefaciens strains (except VirB3, VirB6, and VirD4) and of four virulence proteins in the acetosyringone-induced A. vitis strains (VirB5, VirB7, VirB8, and VirB9). All A. tumefaciens strains formed T pili, showing that the AB minimal medium is appropriate for virulence gene induction and assembly of a functional type IV transporter under these conditions. In contrast, T-pilus formation was not detected in A. vitis strains, and this may either reflect weak induction on the AB induction medium or low cross-reactivity of the VirB2- and VirB5-specific antisera.

Different virulence proteins appear to vary in their susceptibility to high temperatures. Comparative analysis of lysates from cells grown in the presence of acetosyringone at temperatures between 20 and 37°C suggested three groups of virulence proteins. In addition to major T-pilus component VirB2, class I proteins VirB7, VirB9, and VirB10 were easily detected in the cell at 28°C. These proteins are believed to constitute core elements of the transmembrane type IV transporter structure (4, 12, 15), and this may explain their relative persistence under unfavorable conditions. Class II proteins were detected in most strains at 26°C, but were not or detected in small amounts at 28°C. This correlates well with previous observations showing a pronounced reduction in VirB/VirD4-mediated IncQ plasmid transfer in this temperature range (17).

Similar to cell-bound virulence proteins, VirB2 and VirB5 were detected in extracellular high-molecular-mass structures at temperatures up to 26°C, but there was a drastic decrease in T pili in most strains grown at 28°C. Class III proteins VirB3 and VirD4 were detected after virulence gene induction at 20°C and were barely present even at 26°C, which is in accord with optimal tumor formation and IncQ plasmid transfer at 20°C. Interestingly, all class II virulence proteins were detected at 28°C in A. tumefaciens strain Ach5, some of them in strain Chry5, and both strains assembled extracellular T pili under these conditions. Due to the limited specificity of the antisera, the content of VirB3 and VirD4 could not be analyzed, but the formation of T pili suggests that at least VirB3 may have been present at 28°C, showing a strict correlation between accumulation of virulence proteins and functionality of the type IV transporter in a variety of agrobacteria.

The widely different levels of virulence protein accumulation at elevated temperature in most strains may be explained in two ways. First, elevated temperature may lead to disassembly of the transmembrane complex, causing instability and proteolytic degradation of single components. Second, one or more components of the type IV transporter may be degraded at the elevated temperature, hindering correct assembly of the complex. To distinguish between these possibilities, the levels of cell-bound and T-pilus-associated virulence proteins were analyzed after a shift of strain C58 cells grown at 20°C to the T-pilus assembly-nonpermissive temperatures 28 and 37°C. Since virulence gene expression is inhibited at 37°C, replacement of degraded components did not occur. The majority of virulence proteins were apparently stable for up to 48 h after the shift, and VirB2 and VirB5 remained in association with extracellular high-molecular-mass structures, presumably T pili.

Cell-bound VirB3 and VirD4, characterized as class III proteins, however, decreased rapidly after the shift to 28°C. This effect was even more pronounced at 37°C. Depletion of cell-bound VirB4 and VirB11 occurred with similar kinetics, albeit with some delay. VirB3 and VirD4 may not fold properly at elevated temperature, and temperature upshift may cause denaturation even in a preformed type IV transporter complex, followed by degradation by cellular proteases. VirB3 and VirD4 may therefore constitute the Achilles heel of the complex, leading to inactivation of the type IV transporter, followed by further degradation of several other components. Decay of cytoplasmic proteins VirB4 and VirB11 was observed next, suggesting that turnover by cytoplasmic proteases plays a major role, whereas the transmembrane part of the type IV machinery and the extracellular T pili were not notably degraded for up to 48 h after the temperature shift. The results of temperature shift experiments suggest that most virulence proteins and T pili are not temperature sensitive per se and that elevated temperature does not lead to immediate disassembly of the membrane-bound complex, even under heat shock conditions at 37°C.

In cells grown at 28°C, VirB2 and some core (class I) constituents of the complex are detected and may associate in the membranes. A limited set of virulence proteins (class III), however, do not accumulate in the cells to sufficient amounts, precluding correct assembly of many virulence proteins (class II) in the complex. We thus favor the explanation that the degradation of a limited set of virulence proteins prevents assembly of the type IV transporter at elevated temperatures. That other virulence proteins, presumably in a membrane-bound complex, are necessary for mutual stabilization was shown directly in the case of VirB5 (39). Lack of core components VirB7 and VirB9 leads to greatly diminished levels of several VirB proteins in the cell, further supporting the notion that assembly in a complex is necessary for their protection from proteolytic degradation (15).

Interestingly, levels of VirD2 and VirE2 varied similar to other class II proteins, indicating at least transient association of the transported virulence proteins with the membrane-bound type IV transporter. Whereas some of the above results were obtained in strain C58, infection experiments using the other A. tumefaciens strains suggest that similar principles may apply. We used a low infectious dose, which more likely reflects natural infection processes in soil than the standard method using optical densities corresponding to mid-log- or stationary-phase cultures. It was previously shown that use of diluted cultures with limiting amounts of agrobacteria allows semiquantitative assessment of bacterial virulence (33). Using this method, we showed that tumor formation is facilitated at low temperatures in all A. tumefaciens strains investigated. However, there are obvious differences of their temperature sensitivity, and the degree of virulence at 28°C clearly correlates with virulence protein accumulation.

Differential temperature regulation of virB gene transcription, e.g., by internal promoters within the virB operon, may offer an alternative explanation for the differential accumulation of VirB proteins. Whereas we cannot formally exclude this possibility, the results of temperature shift experiments are well in accord with the notion that elevated temperature primarily affects protein stability. Also, previous investigations of different virulence promoters suggested that temperature exerts very similar effects (17, 22), because inactivation of the transmembrane sensor VirA is the primary cause of reduced virulence gene expression.

Temperature upshifts often induce the heat shock response, and production of molecular chaperones and specific proteases for degradation of denatured proteins constitutes part of the adaptation of cells to these conditions (31, 42). Several studies addressed the heat shock response in A. tumefaciens and other α-proteobacteria, such as Bradyrhizobium japonicum, using a shift to the growth-inhibitory temperature 37 or 43°C, respectively (32, 34). Whereas a temperature of 28°C is optimal for growth of A. tumefaciens and not considered a heat shock condition, the apparent degradation of several virulence proteins prompted the analysis of levels of the representative molecular chaperones GroEL and IbpA with antisera generated against E. coli proteins (1).

Incubation of agrobacteria for 3 days at temperatures between 26 and 30°C or a shift from 20 to 28°C did not induce IbpA production. In contrast, incubation at 37°C for 3 days or shift from 20 to 37°C clearly stimulated production of an IbpA-cross-reactive protein, as expected for a heat shock response (not shown). Growth at 28°C thus does not induce a classical heat shock response, indicating that other components of this regulon may not be involved in the heat sensitivity of several components of the type IV transporter. Quite unexpectedly, however, induction of virulence genes at 20°C induced production of an IbpA-cross-reactive protein, albeit not as strongly as during the heat shock response, and increased levels of a GroEL-cross-reactive protein twofold (not shown), indicating that assembly of the type IV transporter may affect the cellular stress response.

However, the results do not explain the reason for the apparent destabilization of the type IV transporter at 28°C, which is an excellent growth temperature for A. tumefaciens. The different heat sensitivities may simply reflect adaptation of the different agrobacteria to conditions in their natural habitats, and some virulence proteins may denature even at relatively low temperatures (31). We could formally exclude the induction of a general heat shock response at 28°C, but different components of the heat shock regulon may be subject to differential regulation. In Coomassie-stained gels from cell lysates, we noticed a prominent protein of 18 kDa at 28°C specifically in strains C58, A208, A281, and A348 (not shown), and this may be a small heat shock protein. Whereas a causal relation to destabilization of the type IV transporter cannot be drawn, the occurrence of this protein in temperature-sensitive strains but not in Ach5 and Chry5 may indicate a temperature response in cells grown at 28°C.

C58, A208, A281, and A348 have the same chromosomal background of strain A136, which is a Ti plasmid-cured derivative of C58. The temperature sensitivity of their type IV transporters may thus be determined by features of the chromosome and/or of small cryptic plasmids. This would be reminiscent of previous findings showing that the chromosomal background of strain Chry5 potentiates the virulence determined by different Ti plasmids compared to that of natural Agrobacterium isolates (24). Further analysis will show whether the temperature lability of the type IV transporter is also determined by genes on the chromosome, or whether it resides in specific features of the virulence proteins. In any case, the temperature sensitivity of gene transfer from different agrobacteria should be carefully considered in the design of plant manipulation experiments.

Many studies on the role of VirB proteins have been performed at 28°C in liquid cultures. Our results imply that levels of several virulence proteins, e.g., VirB3 and VirB4, may have been at least 10-fold lower than those obtained under optimal growth conditions, because such a difference causes loss of the signal after chemiluminescent detection. Our work does not imply that the results of previous work conducted with frequently used agrobacteria is not valid any more or that previous reports of the detection of several virulence proteins were flawed. However, we suggest that care should be taken concerning the evaluation of these results, since the functionality of the type IV transporter may have been negatively affected at 28°C (19).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Steven Pueppke and Eva Zyprian for the donation of A. tumefaciens and A. vitis strains, respectively. We thank Franz Narberhaus for the generous donation of IbpA-specific antiserum and him and the referees of a previous version of this communication for thoughtful comments on the manuscript. We are indebted to Ann Matthysse, Patricia C. Zambryski, and August Böck for support and discussions.

This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) via Sonderforschungsbereich 369/C9.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen S P, Polazzi J O, Gierse J K, Easton A M. Two novel heat shock genes encoding proteins produced in response to heterologous protein expression in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6938–6947. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.21.6938-6947.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlung T, Ingmer H. H-NS: a modulator of environmentally regulated gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:7–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3151679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banta L M, Bohne J, Lovejoy S D, Dostal K. Stability of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB10 protein is modulated by growth temperature and periplasmic osmoadaption. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6597–6606. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6597-6606.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaupre C E, Bohne J, Dale E M, Binns A N. Interactions between VirB9 and VirB10 membrane proteins involved in movement of DNA from Agrobacterium tumefaciens into plant cells. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:78–89. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.1.78-89.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beijersbergen A, Dulk-Ras A, Schilperoort R, Hooykaas P J J. Conjugative transfer by the virulence system of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Science. 1992;256:1324–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5061.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger B R, Christie P J. Genetic complementation analysis of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens virB operon: virB2 through virB11 are essential virulence genes. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:3646–3660. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.12.3646-3660.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun A C. Thermal inactivation studies on the tumor-inducing principle in crown gall. Phytopathology. 1950;40:3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun A C, Mandle R J. Studies on the inactivation of the tumor inducing principle in crown gall. Growth. 1948;12:255–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabezon E, Sastre J I, de la Cruz F. Genetic evidence of a coupling role for the TraG protein family in bacterial conjugation. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;254:400–406. doi: 10.1007/s004380050432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christie P J. Type IV secretion: intercellular transfer of macromolecules by systems ancestrally related to conjugation machines. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:294–305. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Covacci A, Telford J L, Del Giudice G, Parsonnet J, Rappuoli R. Helicobacter pylori virulence and genetic geography. Science. 1999;284:1328–1333. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das A, Xie Y-H. The Agrobacterium T-DNA transport pore proteins VirB8, VirB9, and VirB10 interact with one another. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:758–763. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.3.758-763.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Depicker A, DeWilde M, De Vos G, De Vos R, Van Montagu M, Schell J. Molecular cloning of overlapping segments of the nopaline Ti plasmid of pTiC58 as a means to restriction endonuclease mapping. Plasmid. 1980;31:193–211. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(80)90109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durand J M, Dagberg B, Uhlin B E, Bjork G R. Transfer RNA modification, temperature and DNA superhelicity have a common target in the regulatory network of the virulence of Shigella flexneri: the expression of the virF gene. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:924–935. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez D, Spudich G M, Zhou X-R, Christie P J. The Agrobacterium tumefaciens virB7 lipoprotein is required for stabilization of VirB proteins during assembly of the T-complex transport apparatus. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3168–3176. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3168-3176.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fullner K J, Lara J L, Nester E W. Pilus assembly by Agrobacterium T-DNA transfer genes. Science. 1996;273:1107–1109. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fullner K J, Nester E W. Temperature affects the T-DNA transfer machinery of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1498–1504. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.6.1498-1504.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton C M, Lee H, Li P L, Cook D M, Piper K R, von Bodman S B, Lanka E R W, Farrand S K. TraG from RP4 and TraG and VirD4 from Ti plasmids confer relaxosome specificity to the conjugal transfer system of pTiC58. J Bacteriol. 2001;182:1541–1548. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1541-1548.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hapfelmeier S, Domke N, Zambryski P C, Baron C. VirB6 is required for stabilization of VirB5 and VirB3 and formation of VirB7 homodimers in Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4505–4511. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.16.4505-4511.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hooykaas P J J, Beiersbergen A G M. The virulence system of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1994;32:157–179. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hurme R, Rhen M. Temperature sensing in bacterial gene regulation — what it all burns down to. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:1–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin S, Song Y-N, Deng W-Y, Gordon M, Nester E-W. The regulatory VirA protein of Agrobacterium tumefaciens does not function at elevated temperatures. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6830–6835. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.21.6830-6835.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones A L, Shirasu K, Kado C I. The product of the virB4 gene of Agrobacterium tumefaciens promotes accumulation of VirB3 protein. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5255–5261. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5255-5261.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kovacs L, Pueppke S G. The chromosomal background of Agrobacterium tumefaciens Chry5 conditions high virulence on soybean. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1993;6:601–608. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai E-M, Kado C I. Processed VirB2 is the major subunit of the promiscuous pilus of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2711–2717. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.10.2711-2717.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lai E-M, Kado C I. The T-pilus of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:361–369. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01802-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liles M R, Viswanathan V K, Cianciotto N P. Identification and temperature regulation of Legionella pneumophila genes involved in type IV pilus biogenesis and type II protein secretion. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1776–1782. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1776-1782.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Llosa M, Zupan J, Baron C, Zambryski P C. The N- and C-terminal portions of the Agrobacterium VirB1 protein independently enhance tumorigenesis. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3437–3445. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.12.3437-3445.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maniatis T A, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mogk A, Tomoyasu T, Goloubinoff P, Rüdiger S, Röder D, Langen H, Bukau B. Identification of thermolabile Escherichia coli proteins: prevention and reversion of aggregation by DnaK and ClpB. EMBO J. 1999;18:6934–6949. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.6934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Münchbach M, Nocker A, Narberhaus F. Multiple small heat shock proteins in rhizobia. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:83–90. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.1.83-90.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mushegian A R, Fullner K J, Koonin E V, Nester E W. A family of lysozyme-like virulence factors in bacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7321–7326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakahigashi K, Ron E Z, Yanagi H, Yura T. Differential and independent roles of a ς32 homolog (RpoH) and an HrcA repressor in the heat shock response of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7509–7515. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.24.7509-7515.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Otten L, de Ruffray P. Agrobacterium vitis nopaline Ti plasmid pTiAB4: relationship to other Ti plasmids and T-DNA structure. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;245:493–505. doi: 10.1007/BF00302262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Revell P A, Miller V L. A chromosomally encoded regulator is required for expression of the Yersinia enterocolitica inv gene and for virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:677–685. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riker A J. Studies on the influence of some environmental factors on the development of crown gall. J Agric Res. 1926;32:83–96. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schägger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range of 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt-Eisenlohr H, Domke N, Angerer C, Wanner G, Zambryski P C, Baron C. Vir proteins stabilize VirB5 and mediate its association with the T pilus of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7485–7492. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.24.7485-7492.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stachel S E, Nester E. The genetic and transcriptional organization of the A6 Ti plasmid of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. EMBO J. 1986;5:1445–1454. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04381.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thorstenson Y R, Kuldau G A, Zambryski P C. Subcellular localization of seven VirB proteins of Agrobacterium tumefaciens: implications for the formation of a T-DNA transport structure. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5233–5241. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.5233-5241.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomoyasu T, Mogk A, Langen H, Goloubinoff P, Bukau B. Genetic dissection of the roles of chaperones and proteases in protein folding and degradation in the Escherichia coli cytosol. Mol Microbiol. 2001;40:397–413. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ullrich M, Penaloza-Vazquez A, Bailey A M, Bender C L. A modified two-component regulatory system is involved in temperature-dependent biosynthesis of the Pseudomonas syringae phytotoxin coronatine. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6160–6169. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.21.6160-6169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ullrich M S, Schergaut M, Boch J, Ullrich B. Temperature-responsive genetic loci in the plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea. Microbiology. 2000;146:2457–2468. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-10-2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Larebeke N, Engler G, Holsters M, van den Elsacker S, Zaenen I, Schilperoort R A, Schell J. Large plasmids in Agrobacterium tumefaciens essential for crown gall-inducing ability. Nature. 1974;252:169–170. doi: 10.1038/252169a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Nuenen M, de Ruffray P, Otten L. Rapid divergence of Agrobacterium vitis octopine-cucumopine Ti plasmids from a recent common ancestor. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;240:49–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00276883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winans S C. Two-way chemical signaling in Agrobacterium-plant interactions. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:12–31. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.1.12-31.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequence of the M13mp18 and pUC18 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zupan J, Muth T R, Draper O, Zambryski P C. The transfer of DNA from Agrobacterium tumefaciens into plants: a feast of fundamental insights. Plant J. 2000;23:11–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zupan J R, Ward D, Zambryski P C. Assembly of the VirB transport complex for DNA transfer from Agrobacterium tumefaciens to plant cells. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1998;1:649–655. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(98)80110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]