Abstract

A dinickel catalyst promotes reductive cyclization reactions of 1,1-dichloroalkenes containing pendant olefins. The reactions can be conducted with a Zn reductant or electrocatalytically using a carbon working electrode. Mechanistic studies are consistent with the intermediacy of a Ni2(vinylidene) species, which adds to the alkene and generates a metallacyclic intermediate. β-Hydride elimination followed by C–H reductive elimination forms the cyclization product. The proposed dinickel metallacycle is structurally characterized and its stoichiometric conversion to product is demonstrated. Spin polarized, unrestricted DFT calculations are used to further examine the cyclization mechanism. These computational models reveal that both nickel centers function cooperatively to mediate the key oxidative addition, migratory insertion, β-hydride elimination, and reductive elimination steps.

Keywords: nickel, metal–metal bonds, vinylidene, cyclization, electrocatalysis

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Catalytic 1,6-enyne cycloisomerizations are valuable transformations that yield cyclic unsaturated building blocks from acyclic precursors.1 A notable feature of these reactions is the diversity of products that can be generated from a single starting material (Figure 1a). There are various mechanisms by which transition metal catalysts can engage enyne substrates: oxidative ene–yne coupling to form a metallacycle, attack of an alkene on an electrophilic M(alkyne) species, and addition of a M–H to an alkyne followed by migratory insertion of an alkene. A majority of these processes favor the formation of five-membered ring exocyclization products, with the position of substituents dictated by the specific catalyst/substrate combination being used.

Figure 1.

(a) Exo and endo cyclization modes of 1,6-enynes. (b) Reductive activation of 1,1-dichloroalkenes enable selective vinylidene–alkene cyclization reactions.

There is a less common type of enyne cycloisomerization that generates endocyclization products.2 For example, Wilkinson’s catalyst converts 1,6-enynes into conjugated methylenecyclohexenes.3 On the basis of isotopic labelling experiments, Lee proposed that the reaction is initiated by the isomerization of a Rh(alkyne) complex to a Rh(vinylidene).4,5 It stands to reason that this pathway is disfavored for most other catalysts, because alkynes are approximately 43 kcal/mol more stable than their corresponding vinylidene isomers.6 Consequently, only catalysts that form stable M=C multiple bonds and weak M(π-C≡C) interactions can carry out this step.7

If generation of the key M=C=CR2 intermediate did not rely on an isomerization of an alkyne, it may be possible to develop a more general strategy for catalytic vinylidene transfer. In this context, it was striking to us that the hypothetical reaction of 1,1-dichloroethylene8 and Zn to form vinylidene9 and ZnCl2 is near thermoneutral. Thus, reactive M=C=CR2 species should be thermodynamically accessible from these starting materials. Based on this hypothesis, we discovered that dinickel catalysts could successfully promote intermolecular [2 + 1]-cycloadditions of vinylidenes generated reductively from various substituted 1,1-dichloroalkenes.10 Here, we present the intramolecular variant of this process, which generates the product of a formal vinylidene insertion into a C(sp2)–H bond (Figure 1b). This approach to vinylidene generation addresses some of the previous limitations of enyne endo-cycloisomerizations. For example, internal alkenes are tolerated, and five-membered ring formations are demonstrated. A dinickel metallacycle derived from the addition of a vinylidene to an alkene is structurally characterized, and its role in the mechanism of catalysis is discussed. DFT calculations reveal that catalysis occurs through a series of intermediates and transition states where both Ni centers cooperatively direct bonding changes.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Catalytic Intramolecular Vinylidene Additions to Alkenes.

Following reaction optimization studies, we identified a set of conditions that induces the reductive cyclization of model substrate 1 to form methylenecyclohexene 2 in 92% yield (Table 1, entry 1). The active (i-PrNDI)Ni2Cl (3) catalyst was generated in situ by stirring i-PrNDI (4) (5 mol%) and Ni(dme)Cl2 (10 mol%) over Zn powder (3.0 equiv) for 20 min prior to the addition of 1. Formation of 3 is indicated by the appearance of a deep violet colored reaction solution.11 Premetallated complexes, such as (i-PrNDI)Ni2Cl2 (5) and (i-PrNDI)Ni2(C6H6) (6), provided comparable yields of product 2, 91% and 90%, respectively (entries 4 and 5). The NDI variant containing ortho c-Pent substituents (7) was equally effective in the reaction (entry 6).

Table 1.

Effects of Reaction Parameters on the Reductive Vinylidene Cyclization.a

| entry | deviation from standard conditionsa | yield (2) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | none | 92% |

| 2 | no 4 | 0% |

| 3 | no 4 and no Ni(dme)Cl2 | 0% |

| 4 | (i-PrNDI)Ni2Cl2 (5) instead of 4/Ni(dme)Cl2 | 91% |

| 5 | (i-PrNDI)Ni2(C6H6) (6) instead of 4/Ni(dme)Cl2 | 90% |

| 6 | c-PentNDI (7) instead of 4 | 90% |

| 7 | 0.05 M instead of 0.025 M | 81% |

| 8 | Mn instead of Zn | 88% |

| 9 | Ligands 8–10 (5 mol%) instead of 4b | <10% |

| 10 | 11 or 12 (5 mol%) instead of 4/Ni(dme)Cl2 | <1% |

Standard reaction conditions: 1 (0.10 mmol, 1.0 equiv), i-PrNDI (5 mol%), Ni(dme)Cl2 (10 mol%), Zn (0.3 mmol, 3.0 equiv), NMP (0.8 mL), THF (3.2 mL), 24 h, rt. All yields were determined by 1H NMR using mesitylene (1.0 equiv) as an internal standard.

5 mol% of Ni(dme)Cl2.

A low initial concentration of substrate 1 was beneficial for yield, presumably due to the suppression of competing bimolecular processes. For example, a two-fold increase in concentration to 0.05 M resulted in an 11% decrease in yield (entry 7). In our survey of reductants, Mn provided a similar yield to that obtained with Zn (entry 8).

As a point of comparison, we also tested mononickel catalysts containing various combinations of pyridine and imine donors. In all cases, only trace quantities of 2 were produced (<10% yield, entry 9). Likewise, other Ni(I) dimers 1112 and 1213 also proved to be ineffective as catalysts (entry 10). Collectively, these results suggest that the constrained dinuclear active site of the (NDI)Ni2 system is a requirement for efficient catalysis.

Substrate Scope Studies.

With optimized reaction conditions in hand, we next examined how structural changes to the substrate influence the yield of cyclization (Figure 2). A variety of synthetic routes were used to prepare the requisite 1,1-dichloroalkene substrates. For example, diastereoselective conjugate allylation using an oxazolidinone chiral auxiliary yielded 13.14 Conversion of 13 to aldehyde 14 was carried out with DIBAL-H, and one-carbon homologation using CCl4 (2.0 equiv) and Ph3P (4.0 equiv) yielded 1,1-dichloroalkene 15. The catalytic reductive cyclization was carried out under standard conditions and provided 16 in 81% yield.

Figure 2.

Substrate scope studies. Isolated yields were determined following purification and were averaged over two runs. Standard reaction conditions: substrate (0.2 mmol), i-PrNDI (4) (5–10 mol%), Ni(dme)Cl2 (10–20 mol%), Zn (3.0 equiv), NMP (1.6 mL), THF (6.4 mL), rt or 50 °C, 24 h. a substrate (0.2 mmol), c-PentNDI (7) (10 mol%), Ni(dme)Cl2 (20 mol%), Zn (3.0 equiv), NMP (0.8 mL), THF (7.2 mL), rt, 24 h.

Variation of the substrate tether length grants access to five-membered ring products, requiring only slight modifications to the reaction conditions: increased catalyst loading (10 mol%) and heating at 50 °C. In addition to forming methylenecyclohexenes and methylenecyclopentenes, this method is also amendable to the formation of unsaturated heterocycles (product 18). However, an attempted cyclization to form a seven-membered ring did not yield any product. Common functional groups are tolerated, including protected alcohols, acetals, and esters. Steric hindrance adjacent to the 1,1-dichloroalkene is well-tolerated (products 26, 28, and 30). However, substituting the position next to the terminal alkene results in no yield of cyclized product.

Upon further evaluation of the reaction conditions, we found that a limited scope of products containing substituted exocyclic alkenes are accessible when the c-Pent substituted NDI ligand 7 was used in the place of the i-Pr ligand 4. For example, ester substituted methylenecyclopentene 32 is formed in 63% yield (13:1 Z/E mixture) from 31-E. On the other hand, a substrate containing a Ph substituent on the alkene proved to be unreactive (see Supporting Information for a summary of the reaction limitations).

Evidence in Support of a Stepwise Ni2(vinylidene) Addition Mechanism.

The proposed mechanism for Rh-catalyzed 1,6-enyne cycloisomerization reactions involves an initial [2 + 2]-cycloaddition of a Rh vinylidene and the pendant alkene.4 The metallacyclic intermediate then undergoes β-hydride elimination followed by C–H reductive elimination to form the product. There is evidence to support a similar mechanism for the Ni2-catalyzed reductive cyclization, as opposed to a direct C–H insertion mechanism as would be typical for free vinylidene 1,5-insertions into C(sp3)–H bonds (Figure 3).15

Figure 3.

Experiments supporting a stepwise vinylidene addition mechanism.

A substrate containing a methyl substituent on the alkene was prepared and tested in the reductive cyclization. The putative metallacycle that would be generated from this substrate would have two potential pathways for β-hydride elimination. Indeed, 33 reacts under standard catalytic conditions to yield a 1:4 mixture of two isomeric products (34 and 35) in a combined yield of 84%.

Substrates 36-E and 36-Z react in a stereoconvergent fashion to provide the same product with Z stereochemistry at the exocyclic alkene. One possible explanation for this observation is that the alkene stereochemistry scrambles through a reversible β-hydride elimination/migratory insertion process. This result is inconsistent with a direct C–H insertion mechanism, which would preserve the alkene stereochemistry.

Electrocatalytic Reductive Cyclizations and the Role of Zn.

We next sought to determine whether the only role of Zn is to turn over the catalyst or whether it might be more intimately involved in the mechanism of the cyclization, for example, by forming organozinc intermediates. In the former case, it should be possible to develop an electrocatalytic variant of the cyclization, excluding Zn metal or any Zn(II) salts.16

By cyclic voltammetry (CV), (i-PrNDI)Ni2Cl2 (5) possesses two reduction waves at −1.14 V and −1.34 V vs. Cp2Fe/Cp2Fe+ and one return oxidation at −1.05 V (Figure 4c). We attribute the presence of two reductive events to partial dissociation of chloride in the polar NMP solvent.17 When the CV of 5 was obtained in THF, only the more cathodic wave at −1.34 V was observed.17 There is a second reversible reduction at E1/2 = −1.64 V. When (i-PrNDI)Ni2Cl2 complex 5 is stirred over excess Zn powder, it undergoes a one-electron reduction to the violet (i-PrNDI)Ni2Cl complex 3, and no further reduction is observed. This result suggests that the mechanism of catalysis does not require accessing the two-electron reduced state of the Ni2 complex. When CV experiments were conducted using solutions of complex 5 containing substrate 1, the reduction events for 5 became irreversible, indicating that activation of the 1,1-dichloroalkene by the reduced catalyst is rapid on the CV timescale.

Figure 4.

(a) Controlled potential electrolysis experiments for the catalytic conversion of 1 to 2. (b) Experimental setup (CE = counter electrode; RE = reference electrode; WE = working electrode) and a proposed one-electron catalytic cycle. (c) Cyclic voltammetry data for complex 5 in the presence and absence of 1 (0.3 M [n-BuN4]PF6 in NMP; 100 mV/s scan rate). All cyclic voltammograms were internally referenced to the Cp2Fe/Cp2Fe+ couple.

Based on these data, bulk electrolysis experiments were carried out at constant potential (–0.75 V vs. a Ag/Ag+ reference electrode; approximately −1.35 V vs. Cp2Fe/Cp2Fe+) using substrate 1 in a divided H-cell (Figure 4a and 4b). In order to ensure high mass transport, a large surface area carbon cloth working electrode was used, and the reaction was stirred vigorously at 900 rpm. After 8 h of electrolysis, an aliquot of the reaction mixture was removed. Analysis by 1H NMR spectroscopy indicated that product 2 was formed in 94% yield, and 20.6 C of charge (2.27 F/mol of product) were passed during the 8 h reaction period, corresponding to a Faradaic efficiency of 88%.

Stoichiometric Reductive Cyclization Reactions.

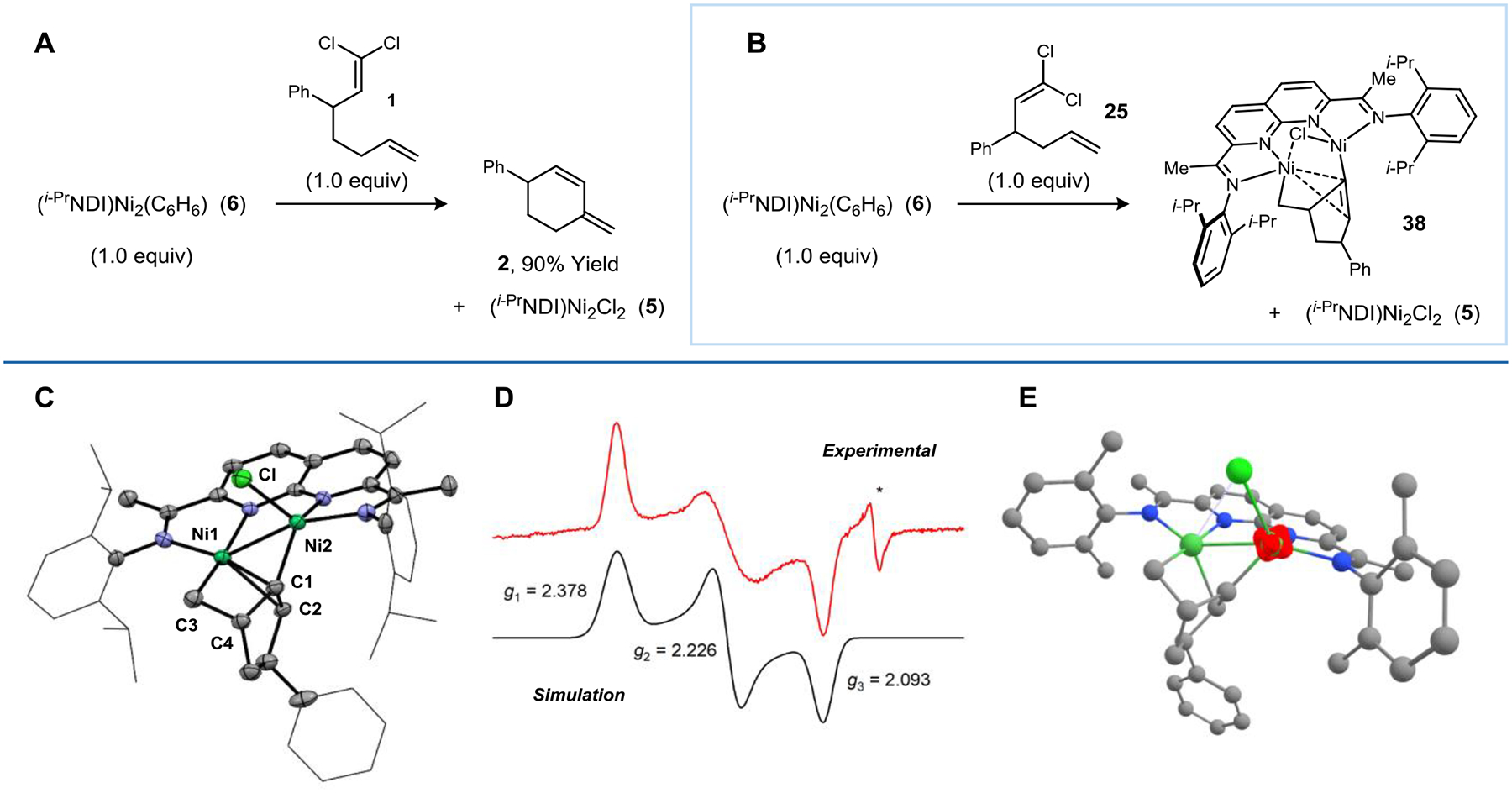

Having established that Zn is only involved in catalyst turnover, we next examined a series of stoichiometric reactions using (i-PrNDI)Ni2(C6H6) (6). A reaction between 6 (1.0 equiv) and substrate 1 was carried out in C6D6 and monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figure 5a). Over the course of 24 h, cyclized product 2 was generated (90% yield), concomitant with the formation of (i-PrNDI)Ni2Cl2 (5). When the same experiment was repeated using substrate 25, some amount of (i-PrNDI)Ni2Cl2 (5) was still generated, but the expected cyclized product 26 could not be detected, and no other diagnostic peaks were observed in the 1H NMR spectrum, even after 24 h (Figure 5b). A frozen-solution EPR spectrum of the product mixture showed a prominent rhombic signal, indicating the presence of an S = 1/2 Ni2 complex (Figure 5d).

Figure 5.

Experiments probing the stoichiometric activation of 1,1-dichloroalkene substrates with (i-PrNDI)Ni2(C6H6) complex 6. (a) Stoichiometric reductive cyclization of 1 using complex 6. (b) Stoichiometric reaction between complex 6 and substrate 25 to form metallacycle 38. (c) XRD structure of metallacycle 38. Selected bond metrics: Ni1–Ni2: 2.743(1) Å; Ni1–C1: 2.000(6) Å; Ni1–C3: 1.967(4) Å; Ni2–C1: 1.954(5) Å; Ni2–Cl: 2.243(2) Å. (d) Frozen solution EPR spectrum for 38 (105 K; toluene). Simulated parameters: g = [2.378, 2.226, 2.093]. * corresponds to a S = 1/2 impurity. (e) UM06-L spin density plot for 38.

After removing the (i-PrNDI)Ni2Cl2 byproduct (5) from this crude mixture, the EPR active complex was successfully isolated, and single crystals were obtained from a pentane/THF solution. XRD analysis revealed that the unknown Ni2 species (38) is a metallacycle, resulting from the addition of a vinylidene to the pendant alkene (Figure 5c). The two Ni atoms, the alkene, and the vinylidene form a five-membered ring, and Ni1 is engaged in a secondary π-interaction with the C1–C2 double bond. Only one chloride is present in the structure, consistent with 38 being in a non-integer spin system. Therefore, the balanced equation for this reaction involves 1.5 equiv of (i-PrNDI)Ni2(C6H6) (6) reacting with 1.0 equiv of substrate 25 to form 0.5 equiv of (i-PrNDI)Ni2Cl2 (5) and 1.0 equiv of 38.

Complex 38 is best described as a mixed valent Ni(II)/Ni(I) species, with the NDI ligand having a neutral charge. The neutral charge of the ligand is supported by analysis of the ligand C–C and C–N bond metrics in the XRD structure. The Ni1–Ni2 distance is 2.743 Å, which is considerably longer than the Ni(I)–Ni(I) single bond in complex 6, suggesting that there is minimal covalent bonding between the two Ni atoms. The spin density plot shows that the unpaired electron is localized on Ni2, which is in a pseudo-tetrahedral geometry (τ4 = 0.85) (Figure 5e). Ni1 is pseudo-square planar (τ4 = 0.14) and is calculated to be in a low-spin configuration.

Metallacycle 38 is sufficiently stable at room temperature to allow for its isolation. However, upon extended heating at 50 °C in NMP/THF, the optimal solvent mixture for the catalytic cyclization, it reacts to form cyclized product 26 in 64% yield after 9 h (Figure 6). Given the relatively slow rate of this stoichiometric process and the modest yield of 26, we wondered whether the catalytic cyclization may require reduction of metallacycle 38. Indeed, metallacycle 38 possesses a reversible one-electron reduction at −1.59 V vs. Cp2Fe/Cp2Fe+, which would be accessible using Zn (see Supporting Information).

Figure 6.

Comparison of rates and yields for stoichiometric cyclizations to form 26 as a function of oxidation state.

When 38 was stirred over Zn (3.0 equiv) in NMP/THF at 50 °C, product 26 was obtained in 96% yield after only 1 h. Given the fast rate of product formation, we were unable to isolate the reduced metallacycle 39. However, when metallacycle 38 was dissolved in C6D6 and reduced over KC8 (1.2 equiv), a new set of diamagnetic signals was observed in the 1H NMR spectrum. These signals decay over the course of 3 h at 50 °C to provide product 26 in 58% yield and the (i-PrNDI)Ni2(C6D6) complex 6 in 61% yield.

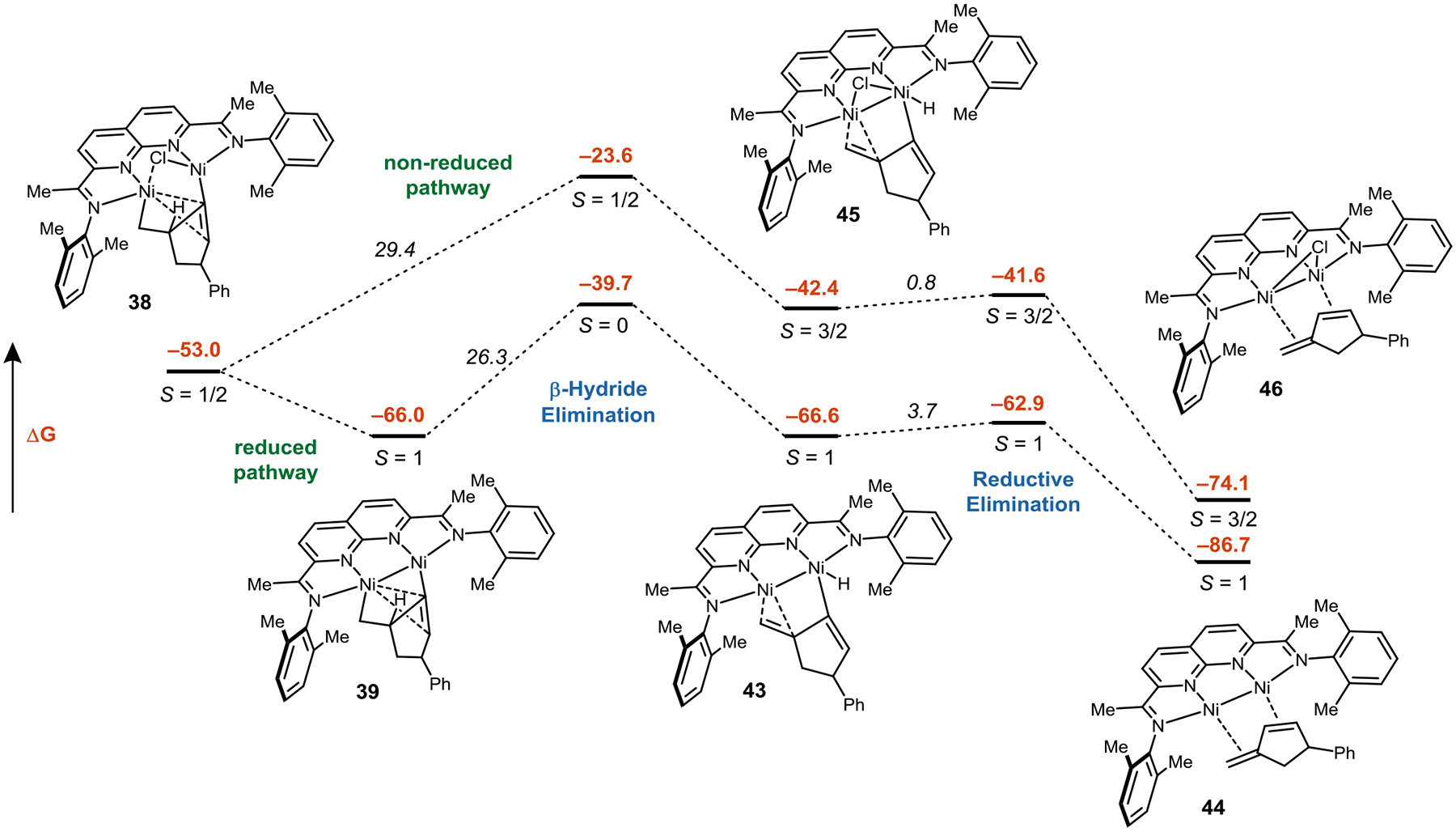

DFT Calculations.

We used unrestricted DFT (UM06-L)18,19,20 to calculate the thermodynamics, barriers, and spin crossovers (MECPro program)21 of reaction pathways that convert 40 to 38 and then to 44 (Figures 7 and 8). From previous benchmarking studies of DFT methods, the M06-L functional was identified as producing relative energies of different spin states for (NDI)Ni2 complexes that matched experimental data.22 Five major pathways were explored for the conversion of 40 to 38, each having oxidative addition, migratory insertion, and reduction steps in different orders. Figure 7 displays only the lowest energy pathway.

Figure 7.

(a) DFT-calculated reaction pathways for the cyclization of 25 to give complex 38. Relative Gibbs free energies are shown in kcal/mol. Isopropyl groups were modeled as methyl groups. (b) 3D representations of key transition-state structures. Spin states are given in parenthesis. Hydrogens are removed for clarity. Distances are reported in Å.

Figure 8.

DFT-calculated reaction pathways for conversion of 38 to 44/46 as a function of oxidation state. Relative Gibbs free energies are shown in kcal/mol.

The initial π-complex 40 favors a triplet ground state, but the singlet is only 3 kcal/mol higher in energy, suggesting that it may have some multireference character. Oxidative addition of the C–Cl bond (TS40) has a low barrier on both the singlet and triplet surfaces. Both Ni centers are directly involved in the oxidative addition, such that the resulting vinyl and chloride fragments in 41 are situated in bridging positions. Vinyl complex 41 has a quintet ground state, and an energy-degenerate spin crossover structure (minimum energy crossing point; MECP) between the triplet and quintet surfaces was identified.

From 41, reduction with Zn coupled to chloride loss is endothermic by 4 kcal/mol. The thermodynamics of this first reduction was calculated as the conversion of Zn2 to linear Zn2Cl. Later, the second reduction was calculated as the conversion of Zn2Cl to ZnCl2 and Zn. This reduction step provides a low barrier pathway for activation of the second C–Cl bond through TS41. Similar to TS40, both Ni centers participate in C–Cl oxidative addition. This transition state leads to bridging vinylidene complex 42, which features a secondary interaction between the vinylidene π-bond and one of the Ni centers (Figure 7). The isolable complex 38 can be accessed through a low energy migratory insertion pathway with a barrier of <2 kcal/mol on the quartet surface (TS42). In progressing from 42 to 38, the Ni–Ni distance elongates from 2.60 to 2.69 Å to accommodate the incoming alkene.

As an alternative mechanism for the formation of 38, a non-reductive second C–Cl oxidative addition step from 41 was considered but found to be higher in energy. Furthermore, without formation of vinylidene 42, migratory insertion of the pendant alkene into the Ni(vinyl) bond of 41 was calculated to be prohibitive in energy (activation barrier: 28 kcal/mol).

Finally, we examined pathways for the conversion of metallacycle 38 to the cyclized product. The fact that complex 38 can be isolated indicates that the subsequent β-hydride elimination must have a relatively high barrier (Figure 8). Our DFT calculations corroborate this finding, and the calculated barrier for β-hydride elimination is 29 kcal/mol. Reduction of 38 and loss of chloride lowers the migratory insertion barrier to 26 kcal/mol, which is also consistent with experimental findings (Figure 8). β-Hydride elimination gives hydride 43. Reductive elimination occurs at a single Ni center and has a barrier of 3 kcal/mol, yielding the product complex 44, where the conjugated diene is η4-coordinated to both Ni centers.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, dinickel catalysts promote the reductive cyclization of 1,1-dichloroalkenes containing pendant alkenes through a Ni2-bound bridging vinylidene intermediate. Previous approaches to carrying out such cyclizations relied on a metal-induced alkyne-to-vinylidene isomerization. However, there is a limited scope of catalysts that can carry out this step, and endo cycloisomerizations are significantly less common that exo cycloisomerizations that proceed through metal(alkyne) intermediates. This reductive strategy may therefore prove useful in other transformations where alkynes are not viable as metal(vinylidene) precursors.

Mechanistic studies are consistent with a putative Ni2(vinylidene) undergoing migratory insertion to generate a metallacyclic intermediate. Product formation would then proceed by β-hydride elimination followed by C–H reductive elimination. In the case of a five-membered ring-forming reaction, the key metallacyclic intermediate proved to be an isolable complex, and reduction with Zn resulted in high-yielding conversion to product. DFT models reveal that the canonical organometallic steps—oxidative addition, migratory insertion, β-hydride elimination, and reductive elimination—involve the direct participation of both Ni centers, with the Ni–Ni interaction responding as needed to accommodate various reactive intermediates.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by the NIH (R35 GM124791). C.U. acknowledges support from a Camille Dreyfus Teacher−Scholar award and a Lilly Grantee award. D.H.E. thanks the NSF Chemical Catalysis Program for support (CHE-1764194). Funding for Hector Torres was provided by the NSF Chemistry and Biochemistry REU Site to Prepare Students for Graduate School and an Industrial Career under award CHE-1757627. We thank Dr. Matthias Zeller for assistance with X-ray crystallography. D.H.E. thanks Brigham Young University (BYU) and the Fulton Supercomputing Lab (FSL).

Footnotes

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at http://pubs.acs.org

Experimental procedures, characterization data, and computational details (PDF)

Cartesian coordinates for stationary points (XYZ)

X-ray crystallography data for 38 (CIF)

REFERENCES

- (1).(a) Ojima I; Tzamarioudaki M; Li Z; Donovan RJ “Transition Metal-Catalyzed Carbocyclizations in Organic Synthesis” Chem. Rev 1996, 96, 635–662; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Aubert C; Buisine O; Malacria M “The Behavior of 1,n-Enynes in the Presence of Transition Metals” Chem. Rev 2002, 102, 813–834; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lloyd-Jones GC “Mechanistic aspects of transition metal catalysed 1,6-diene and 1,6-enyne cycloisomerisation reactions” Org. Biomol. Chem 2003, 1, 215–236; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Echavarren AM; Nevado C “Non-stabilized transition metal carbenes as intermediates in intramolecular reactions of alkynes with alkenes” Chem. Soc. Rev 2004, 33, 431–436; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhang L; Sun J; Kozmin SA “Gold and Platinum Catalysis of Enyne Cycloisomerization” Adv. Synth. Catal 2006, 348, 2271–2296; [Google Scholar]; (f) Michelet V; Toullec PY; Genêt J-P “Cycloisomerization of 1,n-Enynes: Challenging Metal-Catalyzed Rearrangements and Mechanistic Insights” Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2008, 47, 4268–4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).(a) Nuñez-Zarur F; Solans-Monfort X; Rodríguez-Santiago L; Sodupe M “Exo/endo Selectivity of the Ring-Closing Enyne Methathesis Catalyzed by Second Generation Ru-Based Catalysts. Influence of Reactant Substituents” ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 206–218; [Google Scholar]; (b) Lee OS; Kim KH; Kim J; Kwon K; Ok T; Ihee H; Lee H-Y; Sohn J-H “Correlation between Functionality Preference of Ru Carbenes and exo/endo Product Selectivity for Clarifying the Mechanism of Ring-Closing Enyne Metathesis” J. Org. Chem 2013, 78, 8242–8249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Grigg R; Stevenson P; Worakun T “Rhodium (I) catalysed regiospecific cyclisation of 1,6-enynes to methylenecyclohex-2-enes” Tetrahedron 1988, 44, 4967–4972. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Kim H; Lee C “ Cycloisomerization of Enynes via Rhodium Vinylidene-Mediated Catalysis” J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 10180–10181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).(a) Bruneau C; Dixneuf PH “Metal Vinylidenes and Allenylidenes in Catalysis: Applications in Anti-Markovnikov Additions to Terminal Alkynes and Alkene Metathesis” Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2006, 45, 2176–2203; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bruneau C; Dixneuf P Metal vinylidenes and allenylidenes in catalysis: from reactivity to applications in synthesis; John Wiley & Sons, 2008; [Google Scholar]; (c) Trost BM; McClory A “Metal Vinylidenes as Catalytic Species in Organic Reactions” Chem. Asian J 2008, 3, 164–194; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Roh SW; Choi K; Lee C “Transition Metal Vinylidene- and Allenylidene-Mediated Catalysis in Organic Synthesis” Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 4293–4356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Chang N-Y; Shen M-Y; Yu C-H “Extended ab initio studies of the vinylidene–acetylene rearrangement” J. Chem. Phys 1997, 106, 3237–3242. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Bruce MI “Organometallic chemistry of vinylidene and related unsaturated carbenes” Chem. Rev 1991, 91, 197–257. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Manion JA “Evaluated Enthalpies of Formation of the Stable Closed Shell C1 and C2 Chlorinated Hydrocarbons” J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 2002, 31, 123–172. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lee H; Baraban JH; Field RW; Stanton JF “High-Accuracy Estimates for the Vinylidene-Acetylene Isomerization Energy and the Ground State Rotational Constants of: C═CH2” J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 11679–11683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).(a) Pal S; Zhou Y-Y; Uyeda C “Catalytic Reductive Vinylidene Transfer Reactions” J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 11686–11689; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhou Y-Y; Uyeda C “Catalytic reductive [4 + 1]-cycloadditions of vinylidenes and dienes” Science 2019, 363, 857–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Zhou Y-Y; Hartline DR; Steiman TJ; Fanwick PE; Uyeda C “Dinuclear Nickel Complexes in Five States of Oxidation Using a Redox-Active Ligand” Inorg. Chem 2014, 53, 11770–11777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Dible BR; Sigman MS; Arif AM “Oxygen-Induced Ligand Dehydrogenation of a Planar Bis-μ-Chloronickel(I) Dimer Featuring an NHC Ligand” Inorg. Chem 2005, 44, 3774–3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Dong Q; Yang X-J; Gong S; Luo Q; Li Q-S; Su J-H; Zhao Y; Wu B “Distinct Stepwise Reduction of a Nickel-Nickel-Bonded Compound Containing an α-Diimine Ligand: From Perpendicular to Coaxial Structures” Chem. Eur. J 2013, 19, 15240–15247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Smith AB; Cantin L-D; Pasternak A; Guise-Zawacki L; Yao W; Charnley AK; Barbosa J; Sprengeler PA; Hirschmann R; Munshi S; Olsen DB; Schleif WA; Kuo LC “Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Monopyrrolinone-Based HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors” J. Med. Chem 2003, 46, 1831–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Knorr R “Alkylidenecarbenes, Alkylidenecarbenoids, and Competing Species: Which Is Responsible for Vinylic Nucleophilic Substitution, [1 + 2] Cycloadditions, 1,5-CH Insertions, and the Fritsch−Buttenberg−Wiechell Rearrangement?” Chem. Rev 2004, 104, 3795–3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).(a) Perkins RJ; Pedro DJ; Hansen EC “Electrochemical Nickel Catalysis for sp2-sp3 Cross-Electrophile Coupling Reactions of Unactivated Alkyl Halides” Org. Lett 2017, 19, 3755–3758; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Perkins RJ; Hughes AJ; Weix DJ; Hansen EC “Metal-Reductant-Free Electrochemical Nickel-Catalyzed Couplings of Aryl and Alkyl Bromides in Acetonitrile” Org. Process Res. Dev 2019, 23, 1746–1751; [Google Scholar]; (c) DeLano TJ; Reisman SE “Enantioselective Electroreductive Coupling of Alkenyl and Benzyl Halides via Nickel Catalysis” ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 6751–6754; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Jiao K-J; Liu D; Ma H-X; Qiu H; Fang P; Mei T-S “Nickel-Catalyzed Electrochemical Reductive Relay Cross-Coupling of Alkyl Halides to Aryl Halides” Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2020, 59, 6520–6524; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Truesdell BL; Hamby TB; Sevov CS “General C(sp2)–C(sp3) Cross-Electrophile Coupling Reactions Enabled by Overcharge Protection of Homogeneous Electrocatalysts” J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 5884–5893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Zhou Y-Y; Uyeda C “Reductive Cyclopropanations Catalyzed by Dinuclear Nickel Complexes” Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2016, 55, 3171–3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Stationary points were optimized in Gaussian 16 using unrestricted M06-L. All singlet structures refer to open-shell singlets that have spin contamination. All structures were verified as minima or transition-state structures using normal-mode vibrational frequency analysis. All Gibbs energies include standard thermochemical enthalpy and entropy corrections at 298 K.

- (19).Zhao Y; Truhlar DG “The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals” Theo. Chem. Acc 2008, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Frisch MJ; Trucks GW; Schlegel HB; Scuseria GE; Robb MA; Cheeseman JR; Scalmani G; Barone V; Peters-son GA; Nakatsuji H; Li X; Caricato M; Marenich AV; Bloino J; Janesko BG; Gomperts R; Mennucci B; Hratchian HP; Ortiz JV; Izmaylov AF; Sonnenberg JL; Williams-Young D; Ding F; Lipparini F; Egidi F; Goings J; Peng B; Petrone A; Henderson T; Ranasinghe D; Zakrzewski VG; Gao J; Rega N; Zheng G; Liang W; Hada M; Ehara M; Toyota K; Fukuda R; Hasegawa J; Ishida M; Nakajima T; Honda Y; Kitao O; Nakai H; Vreven T; Throssell K; Montgomery JA Jr.; Peralta JE; Ogliaro F; Bearpark MJ; Heyd JJ; Brothers EN; Kudin KN; Staroverov VN; Keith TA; Kobayashi R; Normand J; Raghavachari K; Rendell AP; Burant JC; Iyengar SS; Tomasi J; Cossi M; Millam JM; Klene M; Adamo C; Cammi R; Ochterski JW; Martin RL; Morokuma K; Far-kas O; Foresman JB; Fox DJ Gaussian 16, revision B.01; Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- (21).MECPro Version 1.0.6. Minimum Energy Crossing Program (2020) Snyder Justin D., Hamill Lily-Anne, Faleumu Kavika E., Schultz Allen R. and Ess Daniel H..

- (22).Kwon D-H; Proctor M; Mendoza S; Uyeda C; Ess DH “Catalytic Dinuclear Nickel Spin Crossover Mechanism and Selectivity for Alkyne Cyclotrimerization” ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 4796–4804. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.