Abstract

Combination therapy is a cornerstone of tumor therapy, which can make up for the shortcomings of a single treatment and improve the cure rate of cancer. Near infrared induced therapy is widely applied owing to good accessibility, safety profile, and a wide range of effectiveness. Here, we use reduced nanographene oxide (rNGO) sheets with MnO2 nanoparticles as a photothermal agent to trigger further photodynamic therapy and chemotherapy. Doxorubicin (DOX, chemotherapeutic agent) and methyl blue (MB, photosensitizer) are loaded onto graphene oxide through a strong physical bond and rapidly released under high temperature. Besides, MnO2 nanoparticles can catalyze hydrogen peroxide inside of tumor and produce oxygen as a raw material for photodynamic therapy. In vitro experiments illustrated an effective ablation of PC-12 cells by rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox incubation combined with 808 nm near-infrared (NIR) laser radiation. For in vivo experiments in a model of carotid body tumor, rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox was locally injected, followed by 808 nm NIR laser irradiation. We found that the number of tumor cells was significantly reduced, the tumor volume was reduced, and there were no side effects. This may provide a new idea for the combination treatment of carotid body tumor.

We designed new nanoparticle rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox, and applied to a CBT animal model, it has been proved to be a safe and effective photothermal material in vitro and in vivo.

Introduction

The carotid body tumor (CBT) is a rare neck tumor originating from paraganglion chemical receptors at the carotid artery bifurcation and occurs once in every 30 000 cases.1 Usually, CBT is benign and its malignant biological behavior is rare, accounting for about 4–10% of cases. CBT normally occurs as a painless, slowly increasing neck mass, pressuring surrounding tissues, possibly followed by dysphagia or swallowing pain.2 Previous studies have found that radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or embolization has little effect as the final treatment, and surgical resection remains the primary recommendation. However, due to the rich blood supply of tumors, the close relationship with neurovascular anatomy, and surgical resection difficulties, this treatment option still has significant risks and various complications.3

Photothermal therapy (PTT) and photodynamic therapy (PDT) are two main kinds of general phototherapy protocols of tumor treatment owing to the advantages of higher efficiency, deeper penetration, less adverse side effects, and non-surgery.4 The principle of PTT is to convert light energy into heat energy and induce the subsequent cell necrosis or apoptosis.5 Meanwhile, PDT is based on photosensitizers that adsorb light energy and generate toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) to kill cancer cells.6,34 Compared to other methods, light is an ideal external stimulus because it is easy to adjust, focus, and control remotely. Near-infrared (NIR) light (with wavelengths in the 800–1200 nm range) has greater tissue penetration, making it more suitable for PTT and PDT.7 In recent years, nanomaterials such as gold nanoparticles,8 CNTs,9 black phosphorus,10 and MoS2 nanomaterials11 act as both a PTT agent and a drug nanocarrier to integrate chemotherapy with photothermal therapy to enhance the cytotoxicity on tumor. The ideal PTT candidate should have the following properties: (i) suitable nanoparticulate size and uniform shape for phagocytosis; (ii) good dispersibility in aqueous solutions; (iii) sufficient photothermal conversion efficiency; (iv) exhibit low or no cytotoxicity in living systems. For photosensitizers of PDT, most of the work focuses on three groups (porphyrin family, chlorin family and dyes family) owing to the higher yield of singlet oxygen formation and maximum absorption in the wavelength range 650–800 nm for deeper located tissues.12 However their poor solubility in water limits their intravenous administration. Meanwhile, hypoxia, arisen in solid tumors, not only promotes tumor metastasis but also weakens PDT owing to the lack of oxygen.13 For effective chemotherapy, controlled drug release is necessary for sustained chemotherapy and smart stimulation release including light,14 temperature,15 pH16 and ultrasound17 is developed exhibiting fast response.

Therefore, we designed new MnO2 nanoparticle doped nano-reduced graphene oxide sheets with doxorubicin (Dox, chemotherapeutic agent) and methylene blue (MB, photosensitizer) (rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox). We intelligently combined photothermal/photodynamic/chemotherapy together to get all in one therapy. When rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox nanoparticles were injected into the tumor area, nanoparticles entered tumor cells via the endocytic lysosomal pathway and increased accumulation in tumors through an enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect.18 The temperature of the tumor area increased under NIR irradiation for PTT because the rGO spherical shell and MnO2 nanoparticles adsorbed light energy. Meanwhile, the high temperature and mild acidic environment of the tumor area stimulate the release of Dox for chemotherapy. Meanwhile, MnO2 nanoparticles had unique reactivity with H2O2 in tumor cells to sustainably produce O2, which improved tumor oxygenation in vivo and improved the productivity of ROS.

Given that there are no studies on the photothermal treatment of carotid body tumor and it needs more feasible treatments, we used the rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox nanoparticles to explore the effect on carotid body tumor.

Experimental section

Synthesis of nano-reduced graphene oxide (rGO)

The graphene oxide solution was synthesized by a modified Hummers' method.19 In brief, in the beginning, 1 g expandable graphite was mixed with 10 g sodium chloride crystals, followed by 30 min fine grinding and sodium chloride was removed by water washing. Later, treated graphite was dissolved into 150 mL concentrated sulfuric acid in a flask. Later, 40 g KMnO4 was gradually added into the above solution under strong stirring and reacted at room temperature overnight. Then the whole flask was transferred to an oil bath and the temperature was increased to 60 °C and reacted for 6 h with strong mechanical stirring. Afterwards, the mixture was poured into 1 L DI water and stirred for another 1 h and 40 mL 30% H2O2 was added dropwise to the solution until no more bubbles appeared. The GO sheets were collected by centrifugation and washed with DI water several times until the pH was around 7. To get nano-reduced graphene oxide, an ultrasonic cell disruptor (1000 W, 20 Hz) was utilized at room temperature for 10 h.

Synthesis of rGO@MnO2

Freshly prepared KMnO4 aqueous solution (0.1 M, 20 mL) was added into the prepared GO dispersions (5 mg mL−1, 100 mL) dropwise under magnetic stirring and reacted for 4 h at room temperature in the dark. Finally, rGO@MnO2 was collected by centrifugation and washed with water.

Fabrication of rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox nanoparticles

The fabrication process was similar to nanoprecipitation. Briefly, rGO@MnO2 nanoparticles were dispersed into isopropanol with vigorous sonication and the concentration is 100 mg mL−1. Lecithin and DSPE-PEG5000 (3 : 1 by weight) were dissolved in 4% aqueous ethanol solution at a concentration of 1 mg mL−1. The phospholipid solution (30 mL) was heated to 50 °C. The rGO@MnO2 solution (1 mL) mixed with the desired package (500 μL 2.5 mg mL−1 Dox in DMSO and 100 μL 2.5 mg mL−1 MB in DMSO) was then added dropwise into the preheated phospholipid solution with strong sonication. After cooling down in ice water for 3 min, the cloudy solution was warmed up to ambient temperature and sonication for 3 min, followed by filtration through a surfactant-free cellulose acetate membrane. The unencapsulated molecules and organic solvents were removed using centrifugation. After washing with water three times, the resultant nanoparticles were suspended in water for further use.

Photothermal effect of nanospheres

GO, rGO, and rGO@MnO2 solutions with the same concentration (0.1 mg mL−1) were exposed to an 808 nm NIR laser at a power density of 1.5 W cm−2 for 10 min and the temperature was recorded at intervals of 15 s by using a thermal imager (UTi165K).

NIR/pH-triggered drug release

To measure the release profile of Dox under NIR irradiation, 10 mL of the rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox solution was placed in a dialysis bag (MWCO = 140 000), and then the dialysis bag was sealed and immersed into 90 mL of PBS buffer solution (pH 7.4 or 4) to investigate the effect of pH. Meanwhile, the same dialysis bag was irradiated with an 808 nm NIR laser at a power density of 1.5 W cm−2 for 48 h for NIR stimulations. At set time points, 1 mL solution was retrieved for UV-vis spectrometry at 480 nm.

The photodynamic effect

1,3-Diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF) was selected as the probe to monitor the singlet oxygen produced by rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox. The absorption peak of DPBF at 410 nm was recorded at different irradiation time points. All the solutions were bubbled with nitrogen gas for 1 h to remove oxygen inside before the test.

Cellular experiments

To compare and evaluate the photothermal effects and cytotoxicity of rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox and rGO. A rat chromophobe cell PC-12 was cultured in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum according to the instructions. After being incubated with 100 μg mL−1 rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox or rGO for 12 hours and washed with phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS), some PC-12 cells were irradiated under an 808 nm NIR laser. Then the irradiated and unirradiated PC-12 cells were collected for TEM assay. Thus, the phagocytosis of PC-12 cells on rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox or rGO and the ablation of PC-12 cells by the 808 nm NIR laser were observed. The activity assay of PC-12 cells was then performed. First, the cytotoxicity of rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox or rGO on PC-12 was assessed using CCK-8 cell proliferation assay (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan). PC-12 cells were co-cultured with different concentrations of rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox or rGO (0, 50, 100, 150, 200, and 400 μg mL−1) for 12 h, and then PC-12 cell survival was examined by CCK8 cell proliferation assay. The safe concentration of PC-12 was then selected for the following assays. PC-12 cells were co-cultured with rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox (100 μg mL−1) for 12 h and then irradiated with an 808 nm NIR laser at different power densities (0, 0.35, 0.7 and 1.4 W cm−2) for 5 min. Cell viability was measured using the CCK-8 cell proliferation assay. In another comparison, PC-12 cells were incubated using different concentrations of rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox (0, 50, 100 and 150 μg mL−1) for 12 h, and then half of them were irradiated for 5 min using an 808 nm NIR laser at a power density of 0.7 W cm−2. Meanwhile, in order to compare the PTT effect of rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox with GO, some PC-12 cells were incubated with GO (100 μg mL−1), and then half of them irradiated with an 808 nm NIR laser at a power densities of 0.7 W cm−2, and these cells were stained with calcein AM/PI (Dojindo Laboratories, Shanghai, China) and observed and photographed with a Zeiss LSM 510 immunofluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss Strasse, Oberkochen, Germany).35 Flow cytometry (FCM) was performed to perform cell apoptosis analysis after annexin V/PI staining.

Animal experiments

Nude mice (male, age: 8 weeks) were purchased from the Shanghai Model Biology Research Center (Shanghai, China). All animal operations followed the guidelines for care and use of laboratory animals by the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine and were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Ninth People's Hospital Affiliated to the Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. Surgically resected specimens of patients diagnosed with CBT were cut into multiple 1 cm3 masses. After successful intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital sodium (40 mg kg−1) in the mice, longitudinal incisions were made on their backs and the CBT masses were subcutaneously inserted. Finally, incisions were closed layer by layer. One week later, the incisions healed well, the back tumor volume was stable, and no necrosis or liquefaction was detected. Hence, the CBT model was successfully established.

Photothermal therapy and immunohistochemistry

Mice were randomly divided into control or experimental groups. The tumor in the experimental group was locally injected with rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox (100 μL), while the control received the same amount of PBS solution. Then, the tumor was vertically irradiated with an 808 nm near-infrared (NIR) laser with a power density of 0.7 W cm−2 for 5 min. A GX-300 photothermal medical equipment and infrared camera (Shanghai Arret Electronics Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) were used to monitor temperature changes in real time. The volumes of tissue swelling on the back of the mice were measured immediately after treatment, on days 3, 7, and 14. Finally, the mice were sacrificed two weeks after surgery for blood biochemical indices and histological analyses.

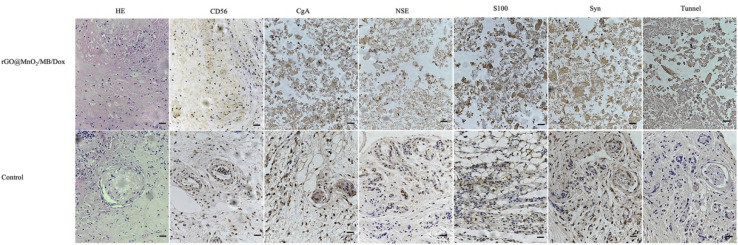

Tumor masses in experimental and control groups were fixed with paraformaldehyde (PFA), sectioned with paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin/eosin (HE). Images were recorded with a light microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and analyzed with Image-Pro-Plus (IPP). Meanwhile, frozen sections were analyzed by immunohistochemistry (CD56, CgA, NSE, S100, Syn, Tunnel).

Long-term toxicity analyses

Blood samples were also collected for biochemical analyses. The heart, liver, lung, and kidney were extracted for HE staining for histological analyses.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and morphology of rGO@MnO2

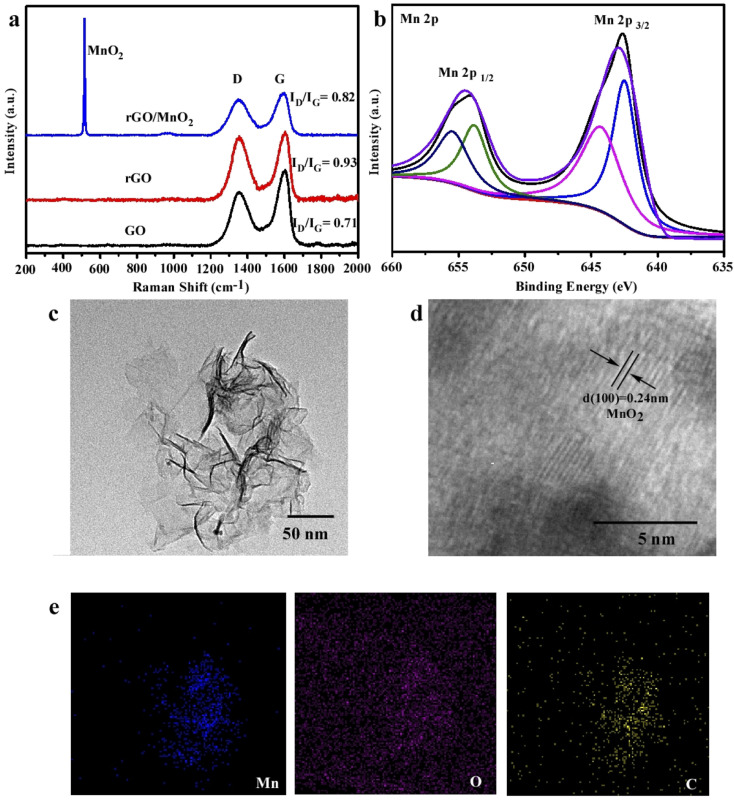

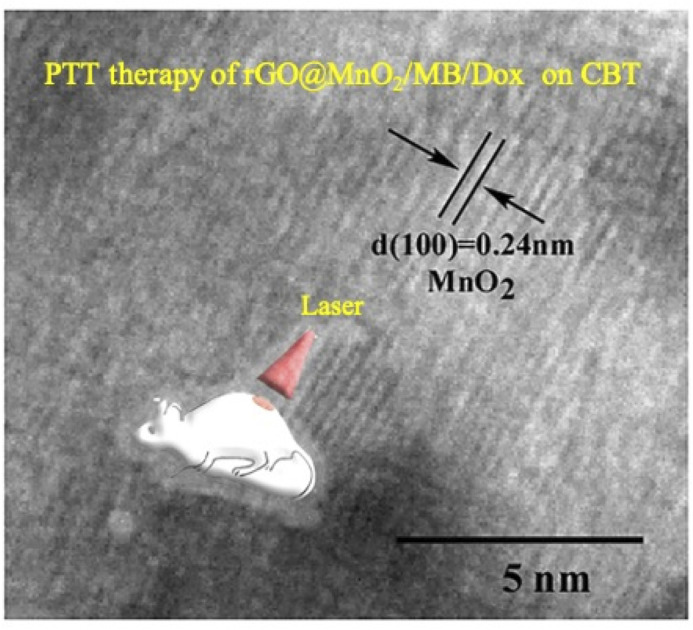

Fig. 1a illustrates that GO was partially reduced during the strong sonication process because the ID/IG ratio was increased from 0.71 to 0.93 and rGO could be further oxidized by the introduction of KMnO4 because the ID/IG ratio decreased to 0.82, which matched with previous work.20 Meanwhile, the bands located at 570 cm−1 in the spectra of rGO@MnO2 can be ascribed to the symmetric stretching vibrations of Mn–O of MnO2.21 MnO2 nanoparticles were formed during this oxidation reaction and loaded onto GO nanosheets. The XPS result in Fig. 1b also confirmed the formation of MnO2. In particular, two peaks (654.6 and 643.2 eV) are ascribed to Mn4+.22 The morphology and structure of rGO@MnO2 were reflected by TEM results in Fig. 1c where the whole size was around 150 nm, which are designed to be phagocytized by tumor cells. The interplanar spacing on rGO sheets belonged to the (100) plane of MnO2 as shown in Fig. 1d.23,24 The elemental mapping also confirmed the existence of Mn element, which uniformly covers the whole surface of rGO nanosheets in Fig. 1e.

Fig. 1. Morphology of rGO@MnO2 nanoparticles. (a) Raman spectrum of GO, rGO, and rGO@MnO2. (b) XPS high-resolution scans of Mn 2p in rGO@MnO2 nanoparticles. (c) TEM images of rGO@MnO2. (d) TEM images of rGO@MnO2 nanoparticles with a high-magnification image of crystals. (e) Elemental mapping of C, O and Mn of rGO@MnO2 nanoparticles.

Characterization of rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox for all in one function

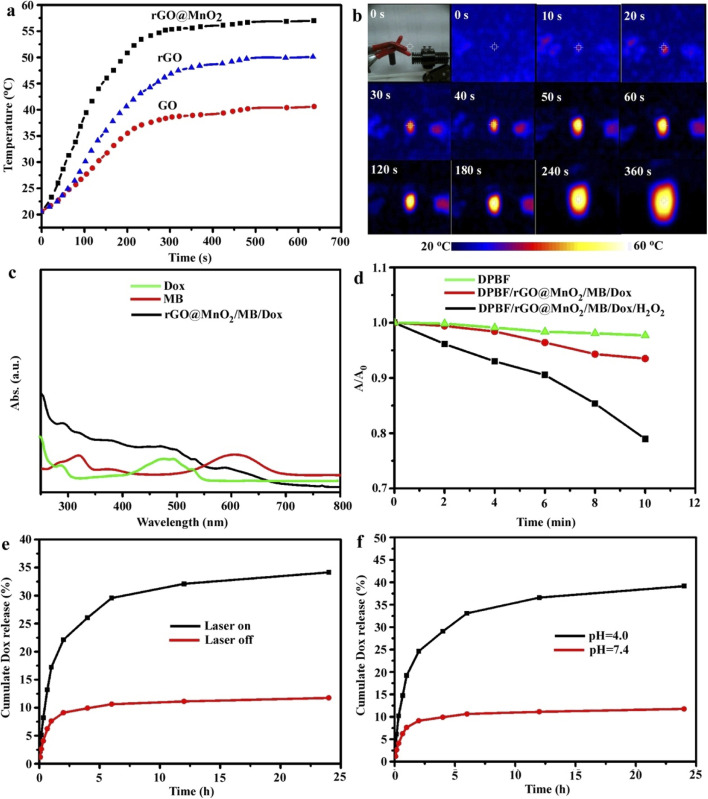

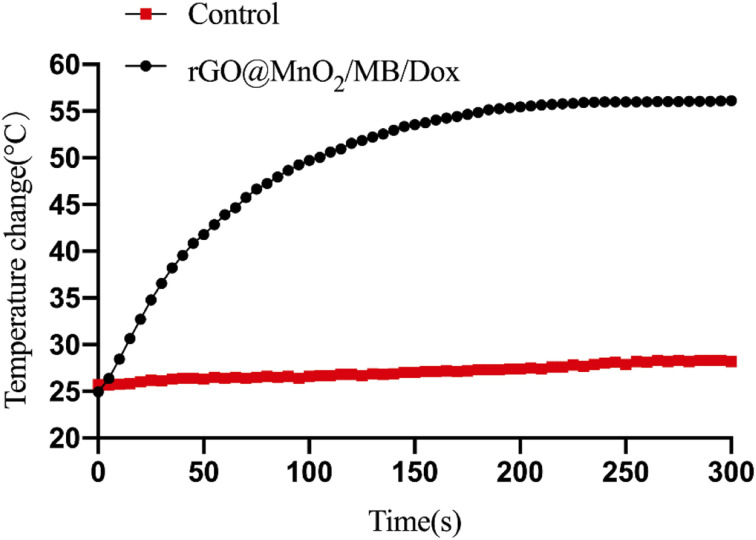

As shown in Fig. S1a,† vesicular rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox nanoparticles with a diameter range of 150–200 nm were observed by SEM. The nanoparticles were uniformly dispersed in an aqueous solution. The average hydrodynamic diameter was determined by DLS and after encapsulation with MB/Dox the diameter was increased from 143.32 to 183.42 nm as shown in Fig. S1b.† Meanwhile the good stability in water was proved by the fact that the size did not show obvious changes even in the past two weeks as shown in Fig. S1c.† To investigate the photothermal properties, an 808 nm NIR laser at a power density of 1.5 W cm−2 was introduced to irradiate at the same concentration (0.1 mg mL−1) for 6 min. From Fig. 2a, GO had week photothermal properties and the photothermal efficiency greatly increased after been reduced to rGO owing to fewer defects, which match with previous reports.25 MnO2 doping could further improve the photothermal properties and the temperature reached 55.2 °C in 5 min because of the high photothermal conversion performance of MnO2 (ref. 26), which even could compensate for the loss of oxidation of GO. The successful loading of Dox/MB was proved by using UV-vis spectra shown in Fig. 2c, and the two peaks of the black line represent Dox and MB compared with each pure solution, which could dissolve into ethyl alcohol from nanoparticles. More importantly, rGO@MnO2 exhibits faster and stronger O2 generation capacity with H2O2 as MnO2 accelerates O2 generation as shown in Fig. S2.†28 To quantitatively analyze the generation of singlet oxygen, the typical 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF) agent was applied. The generation of singlet oxygen could oxidize DPBF to decrease its absorbance intensity in the UV-vis spectrum at a wavelength of 410 nm.27 It could be found that the absorbance intensity of DPBF decreased significantly upon the exposure of DPBF solution to NIR irradiation in the presence of rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox/H2O2 for 10 min (Fig. 2d), demonstrating the quick production of singlet oxygen during PDT. Importantly, the slight decrease of the rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox group illustrated the function of the catalyst MnO2, which consumed H2O2 and supplied O2 for singlet oxygen. Fig. 2e demonstrates the 808 nm NIR laser triggered Dox release, and without irradiation only 11.8% of Dox was released after 24 h and 34.8% of Dox was released under irradiation because heat will accelerate molecular motion. And Fig. 2f shows the influence of pH where the release of Dox from rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox is greatly inhibited in neutral solution but accelerated in mildly acidic buffer solution with a 24 h-releasing amount of 39.6% (pH 4) owing to the break of hydrophobic interactions between multifunctional GO and aromatic Dox molecules. This pH-responsive release was vital for chemotherapy as rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox could maintain the drug when injected into neutral blood vessels and start to release within acidic tumor tissues.

Fig. 2. Characterization of rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox nanoparticles. (a) The rate of temperature rise at a constant laser function power (880 nm, 1.5 W cm−2) for GO, rGO and rGO@MnO2 solutions with the same concentration (0.1 mg mL−1). (b) IR thermal images of 0.1 mg mL−1 rGO@MnO2 solution. (c) UV-vis absorption spectra of free Dox (green), free MB (red) and rGO@MnO2/Dox/MB (black) in ethyl alcohol. (d) Comparison of the decay rate of DPBF under NIR laser irradiation at different times. (e and f) Dox release profiles of rGO@MnO2/Dox/MB with or without NIR laser irradiation and different pH environments.

This indicated that rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox is an excellent PTT agent and has potential applications in cell ablation in vitro.

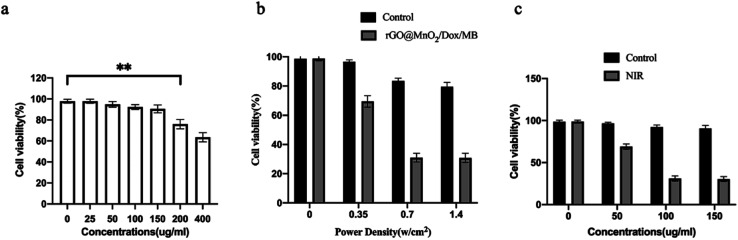

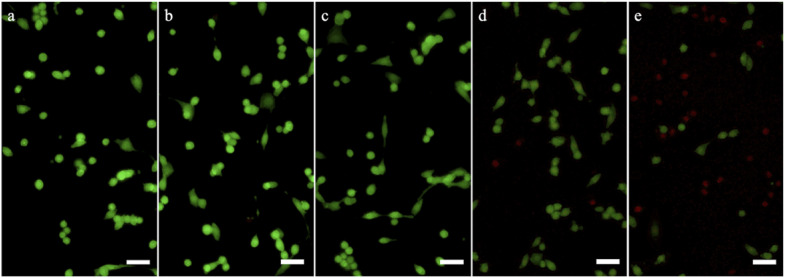

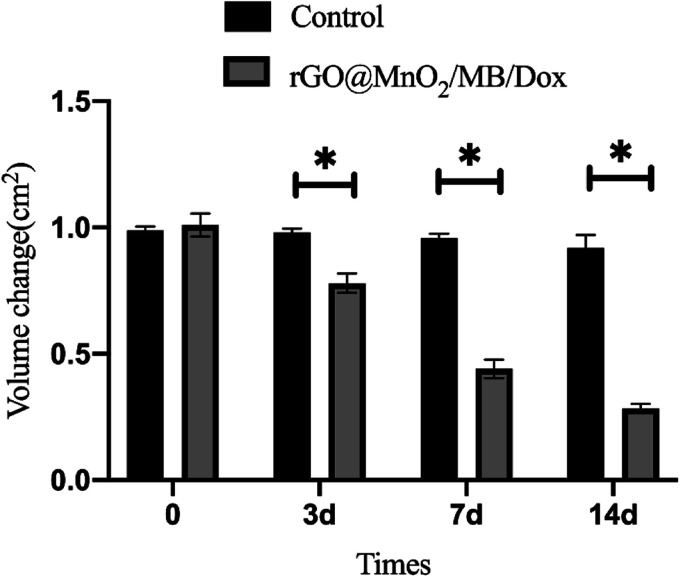

In vivo experiment and histological analyses

A prerequisite for the removal of chromophores is their ability to take up tiny nanoparticles. TEM results showed that PC-12 cells co-incubated with rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox exhibited significant phagocytosis compared to normal PC-12 cells and no significant organelle damage was observed. However, PC-12 cells co-cultured with rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox exhibited significant nucleolysis and cytolysis after 5 min exposure to an 808 nm NIR laser at a power density of 0.7 W cm−2 (Fig. 5). In contrast, the cells co-cultured with rGO showed little change. TEM analysis showed that rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox combined with NIR treatment could effectively remove PC-12 cells and promote cell death. Cytotoxicity assays were then performed to determine whether rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox could be safely used in biomedical and clinical studies. First, rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox was co-cultured with PC-12 cells for 12 h. It was found that there was no significant difference in cell viability between the rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox group and the control group (Fig. 3) at the concentrations of 150 μg mL−1 and below, so in the subsequent experiments, 100 μg mL−1 rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox was co-cultured with PC-12 cells to ensure their biosafety. Next, the effect of NIR laser power density on cell viability was analyzed to explore the optimal power of the 808 nm NIR laser, and cell viability was measured by CCK-8 cell proliferation assay, and live/dead cells were stained with calcein AM/PI and examined under a fluorescence microscope. The results showed that the viability of PC-12 cells decreased gradually with increasing laser power, but the power density of 0.7 W cm−2 was similar to the maximum value of 1.4 W cm−2 and it was safer. The combination of rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox could remove most of the PC-12 cells (Fig. 3). And to investigate the effect of this composite, we chose to compare rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox with rGO for a comparative study. Some PC-12 cells were co-cultured with GO (100 μg mL−1), and half of them were irradiated with a NIR laser. Calcein AM (green)/PI (red) staining for living (green)/dead (red) cells showed that only a very small fraction of cells in the GO + NIR group died, while the majority of cells in the rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox + NIR group died (Fig. 4). As apoptosis is an important type of programmed cell death, which can be induced by the thermal effect, we used annexin V/PI stanning to determine the rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox effect on the PC-12 cell and discriminate between cell apoptosis and necrosis. Toward this end, FCM was performed showing that compared with the rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox group, the rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox + NIR group exhibited a significantly higher mid/late apoptosis (38.4 vs. 4.88%) index of the PC-12 cell with a statistical difference. Meanwhile, the necrosis index of macrophages was different between the two groups (Fig. S4†). These results demonstrated that rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox could ablate PC-12 effectively partly by inducing cell apoptosis. These results indicate that rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox is a safe and low toxic photothermal material that can effectively ablate PC-12 in combination with an 808 nm NIR laser. GO failed to show significant cell destruction under NIR treatment. The results of in vitro PTT indicate the need to further explore the effects of rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox in animal models. As a type of extra-renal pheochromocytoma, the vast majority of CBTs are benign, and given the greater risk of surgical resection and complications, reduction in size to improve symptoms is also a viable option. In vitro experiments using PC-12 cells have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox.29–31 Therefore, we established a CBT model in nude mice using specimens from CBT patients, and then subcutaneously implanted in the mice. One week later, the tumor on the back of nude mice was stable without dissolution, and the CBT model was successfully established (Fig. S3†). Then, a rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox solution (100 μL) was percutaneously injected into the tumor in the experimental group and an equal volume of PBS was injected into the tumor for the control group. Then local irradiation (0.7 W cm−2) was performed on the mice's back using an 808 nm NIR laser. At the same time, temperature changes in the whole body were recorded using an infrared camera. Within 5 min, the local surface temperature of the experimental group progressively increased from 25 to 57 °C, while the PBS control group increased only slightly (Fig. 6). The above results confirmed the excellent photothermal effect of rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox. By measuring the volume of the tumor, we found that in the experimental group the volume decreased gradually over time compared with the control group (Fig. 7).

Fig. 5. (a) An overall review of PC-12 cells. (b) High-resolution representative TEM image of rGO@MnO2/Dox/MB swallowed by cells. (c) Representative TEM image of PC-12 cells incubated with the PBS solution of rGO@MnO2/Dox/MB after laser irradiation.

Fig. 3. Cytotoxicity of rGO@MnO2/Dox/MB and PTT, and the in vitro PTT effect of rGO@MnO2/Dox/MB in combination with 808 nm NIR laser irradiation on PC-12 cells. (a) In vitro relative cell viability of PC-12 cells co-cultured with or without various concentrations of rGO@MnO2/Dox/MB for 12 h. (b) Relative viabilities of PC-12 cells under NIR laser irradiation at different power densities (0, 0.35, 0.7, and 1.4 W cm−2) alone (black) or after incubation with CuCo2S4 NCs (80 μg mL−1) (grey). (c) Relative viabilities of PC-12 cells after incubation with rGO@MnO2/Dox/MB at different concentrations (0, 50, 100, and 150 μg mL−1) alone (black) or followed by NIR laser irradiation (0.7 W cm−2) after incubation (grey).

Fig. 4. Representative images of calcein AM (green)/PI (red) staining for living (green)/dead (red) cells after incubation with rGO@MnO2/Dox/MB or GO (0.1 mg mL−1) followed by NIR laser irradiation (0.7 W cm−2). (a) PC-12 cells alone. (b) PC-12 cells incubated with GO (0.1 mg mL−1). (c) PC-12 cells incubated with rGO@MnO2/Dox/MB (0.1 mg mL−1). (d) PC-12 cells incubation with GO followed by NIR laser irradiation (0.7 W cm−2). (e) PC-12 cells incubated with rGO@MnO2/Dox/MB followed by NIR laser irradiation (0.7 W cm−2).

Fig. 6. Temperature change of the two groups.

Fig. 7. Volume change of the two groups. *P < 0.05.

Two weeks later, mice were killed and tumor specimens were retrieved for HE and immunohistochemical analyses. Histologically, CBT has a well-developed master cell nest surrounded by a large number of supporting cells, mainly tumor cells referring to the master cells.32,33 Due to its neuroendocrine cell characteristics, immunohistochemical staining of Syn, NSE, CD56, and CgA was positive, while the supporting cell was positive for S100. At the same time, Tunel staining was used to observe cell apoptosis. We observed a presentive master cell nest in the control group, while some tumor cells were positive to Syn, NSE, CD56, and CgA staining, which confirmed the tumor as a CBT. Using NIR laser irradiation, the number of all cell types in the experimental group significantly reduced, including those positive to immunohistochemical staining. Moreover, nuclear fragmentation and other phenomena significantly increased. However, no increase in apoptosis was observed in the Tunel staining, considering that more cells presented a necrotic form (Fig. 8). Meanwhile, the mass volume of the experimental group was slightly lower after two weeks compared to the control group, confirming the effectiveness of photothermal therapy for CBT. However the treatment could not achieve the same effect as surgical resections but the tumor grew more slowly, and the degree of compression symptoms was not achieved. On the other hand, the tumor slowly shrinks leading to symptom relieving without removal.

Fig. 8. Histological analysis of carotid body tumor in the two groups (magnification: 200 times).

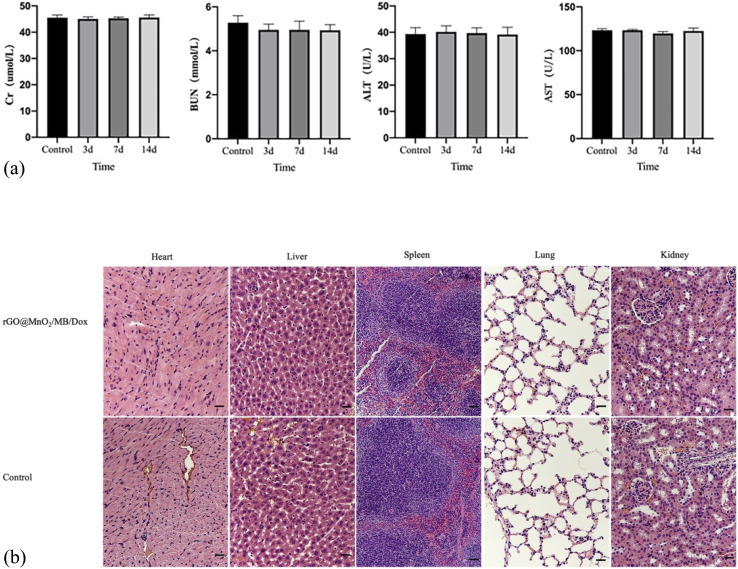

A qualified material for treatment should not be toxic for the body. Therefore, we retrieved blood samples immediately after treatment on days 3, 7, and 14 to evaluate biochemical indices such as ALT, AST, BUN and Cr in mice. We also took heart, liver, spleen, kidney, and lung samples to detect the toxicity via HE staining. Regarding biochemical indices, no significant differences were detected compared to controls (Fig. 9a). Besides, no clear inflammatory reactions or cell necrosis was observed in the heart, lung, kidney, and liver tissue samples (Fig. 9b). Altogether, these results indicated that the photothermal material was harmless or had little toxicity to mice.

Fig. 9. (a) Blood biochemistry assays of both the groups. (b) H&E-stained slices of main organs (magnification: 100 times).

Conclusion

In this study, we successfully synthesized and characterized rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox with high photothermal efficiency, non-toxicity and good biocompatibility. rGO@MnO2/MB/DOX incubation combined with 808 nm near-infrared (NIR) laser irradiation can effectively ablate tumor cells and demonstrate the good photothermal effect of the material in comparison with GO. We establish an animal model of CBT, and then showed that rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox combined with 808 nm near infrared (NIR) irradiation could effectively reduce CBT tumor cells and shrink the tumor size, which is promising to reduce the surgical rate and surgical complications of CBT patients, and our study has demonstrated that rGO@MnO2/MB/Dox is a promising nano-platform for tumor treatment under 808 nm NIR laser irradiation, which may be a new approach for CBT treatment.

Funding

This work was financially sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 81971712 and 81971758), the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai Science and Technology Committee (Grant No. 20ZR1431600), and the Shanghai Sailing Program (Grant No. 20YF1423800).

Author contributions

Xinwu Lu, Jinbao Qin and Yuting Cai contributed to the conception and design of the study. Huaxiang Lu, Peng Qiu, Xing Zhang and Yuting Cai performed the experimental work. Weimin Li carried out the analysis of the data. Huaxiang Lu and Yuting Cai wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See https://doi.org/10.1039/d2na00086e

References

- Boscarino G. Parente E. Minelli F. Ferrante A. Snider F. An evaluation on management of carotid body tumour (CBT). A twelve years experience. Il Giorn. Chir. 2014;35(1–2):47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Mey A. G. Jansen J. C. van Baalen J. M. Management of carotid body tumors. Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am. 2001;34(5):907–924. doi: 10.1016/S0030-6665(05)70354-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Bogt K. E. Peeters M.-P. F. V. van Baalen J. M. Hamming J. F. Resection of carotid body tumors: results of an evolving surgical technique. Ann. Surg. 2008;247(5):877–884. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181656cc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibu E. S. Hamada M. Murase N. Biju V. Nanomaterials formulations for photothermal and photodynamic therapy of cancer. J. Photochem. Photobiol., C. 2013;15:53–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2012.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W. Zhang X. Zhang S. Wei G. Su Z. Biomedical and bioactive engineered nanomaterials for targeted tumor photothermal therapy: a review. Mater. Sci. Eng., C. 2019;104:109891. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.109891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson C. A. Evans D. H. Abrahamse H. Photodynamic therapy (PDT): a short review on cellular mechanisms and cancer research applications for PDT. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 2009;96(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raza A. Hayat U. Rasheed T. Bilal M. Iqbal H. M. “Smart” materials-based near-infrared light-responsive drug delivery systems for cancer treatment: a review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019;8(1):1497–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.jmrt.2018.03.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X. El-Sayed M. A. Gold nanoparticles: Optical properties and implementations in cancer diagnosis and photothermal therapy. J. Adv. Res. 2010;1(1):13–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2010.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu G.-H. Shang W.-T. Deng H. Han Z.-Y. Hu M. Liang X.-Y. Fang C.-H. Zhu X.-H. Fan Y.-F. Tian J. Targeting carbon nanotubes based on IGF-1R for photothermal therapy of orthotopic pancreatic cancer guided by optical imaging. Biomaterials. 2019;195:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. Tong L. Li Z. Yang N. Fu H. Wu L. Cui H. Zhou W. Wang J. Wang H. Stable and multifunctional dye-modified black phosphorus nanosheets for near-infrared imaging-guided photothermal therapy. Chem. Mater. 2017;29(17):7131–7139. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b01106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z. Li B. Shen C. Wu D. Fan H. Zhao J. Li H. Zeng Z. Luo Z. Ma L. Metallic 1T Phase Enabling MoS2 Nanodots as an Efficient Agent for Photoacoustic Imaging Guided Photothermal Therapy in the Near-Infrared-II Window. Small. 2020;16(43):2004173. doi: 10.1002/smll.202004173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan M. Zhao S. Liu W. Lee C. S. Zhang W. Wang P. Photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2019;8(13):1900132. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201900132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockel M. Vaupel P. Tumor hypoxia: definitions and current clinical, biologic, and molecular aspects. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2001;93(4):266–276. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. Gao Y. Cao Z. Wu B. Wang L. Wang H. Dang Z. Wang G. Nanocomposites of spiropyran-functionalized polymers and upconversion nanoparticles for controlled release stimulated by near-infrared light and pH. Macromolecules. 2016;49(19):7490–7496. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b01760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z. Gao N. Wang H. Sukhishvili S. A. Temperature-triggered on-demand drug release enabled by hydrogen-bonded multilayers of block copolymer micelles. J. Controlled Release. 2013;171(1):73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Song S. Liu J. Liu D. Zhang H. ZnO-functionalized upconverting nanotheranostic agent: multi-modality imaging-guided chemotherapy with on-demand drug release triggered by pH. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54(2):536–540. doi: 10.1002/anie.201409519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein-Barash H. Orbey G. Polat B. E. Ewoldt R. H. Feshitan J. Langer R. Borden M. A. Kohane D. S. A microcomposite hydrogel for repeated on-demand ultrasound-triggered drug delivery. Biomaterials. 2010;31(19):5208–5217. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greish K. Enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect for anticancer nanomedicine drug targeting. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;624:25–37. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-609-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou X. Gan L. Luo Z. Graphene-templated growth of hollow Ni3S2 nanoparticles with enhanced pseudocapacitive performance. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2014;2(45):19214–19220. doi: 10.1039/C4TA04502E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. Xu P. Shu Z. Wu M. Wang L. Zhang S. Zheng Y. Chen H. Wang J. Li Y. Multifunctional graphene oxide-based triple stimuli-responsive nanotheranostics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014;24(28):4386–4396. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201400221. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao T. Glerup M. Krumeich F. Nesper R. Fjellvåg H. Norby P. Microstructures and spectroscopic properties of cryptomelane-type manganese dioxide nanofibers. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2008;112(34):13134–13140. doi: 10.1021/jp804924f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. Liu Y. Arandiyan H. Yang H. Bai L. Mujtaba J. Wang Q. Liu S. Sun H. Uniform Fe3O4 microflowers hierarchical structures assembled with porous nanoplates as superior anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016;389:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.07.105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shah H. U. Wang F. Javed M. S. Saleem R. Nazir M. S. Zhan J. Khan Z. U. H. Farooq M. U. Ali S. Synthesis, characterization and electrochemical properties of α-MnO2 nanowires as electrode material for supercapacitors. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2018;13(7):6426–6435. doi: 10.20964/2018.07.48. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma E. Li J. Zhao N. Liu E. He C. Shi C. Preparation of reduced graphene oxide/Fe3O4 nanocomposite and its microwave electromagnetic properties. Mater. Lett. 2013;91:209–212. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2012.09.097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. Liu J. Fang X. Zhang Z. Reduced graphene oxide dispersed nanofluids with improved photo-thermal conversion performance for direct absorption solar collectors. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 2017;163:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.solmat.2017.01.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. Guan S. Weng Y. Xu S.-M. Lu H. Meng X. Zhou S. Highly efficient vacancy-driven photothermal therapy mediated by ultrathin MnO2 nanosheets. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11(6):6267–6275. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b20639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang P. Qian X. Chen Y. Yu L. Lin H. Wang L. Zhu Y. Shi J. Metalloporphyrin-encapsulated biodegradable nanosystems for highly efficient magnetic resonance imaging-guided sonodynamic cancer therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139(3):1275–1284. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X. Yang Y. Gao F. Wei J.-J. Qian C.-G. Sun M. J. Biomimetic hybrid nanozymes with self-supplied H+ and accelerated O2 generation for enhanced starvation and photodynamic therapy against hypoxic tumors. Nano letters. 2019;19(7):4334–4342. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b00934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D. Liu L. Yao H. Hu Y. Ji T. Liu X. et al., A retrospective study in management of carotid body tumour. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009;47:461–465. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amato B. Serra R. Fappiano F. Rossi R. Danzi M. Milone M. et al., Surgical complications of carotid body tumors surgery: a review. Int. J. Angiol. 2015;34:15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metheetrairut C. Chotikavanich C. Keskool P. Suphaphongs N. Carotid body tumor: a 25-year experience. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2016;273:2171–2179. doi: 10.1007/s00405-015-3737-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- edeker C. C. Ridder G. J. Schipper J. et al., Paragan-gliomas of the head and neck: diagnosis and treatment. Fam. Cancer. 2005;4(1):55–59. doi: 10.1007/s10689-004-2154-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt N. Baek W. K. Lachkar S. Iwanaga J. Mian A. Blaak C. Shah S. Griessenauer C. Shane Tubbs R. Loukas M. The carotid body and associated tumors: updatedreview with clinical/surgical significance. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2019;33(5):500–503. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2019.1617404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S. Yang Y. Wu H. Li J. Xie P. Xu F. et al., Thermosensitive and tum or microenvironment activated nanotheranostics for the chemodynamic/photothermal therapy of colorectal tumor. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022;612:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2021.12.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X. Wang S. Wu H. Liu Y. Xu F. Zhao J. A multimodal antimicrobial platform based on MXene for treatment of wound infection. Colloids Surf., B. 2021;207:111979. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2021.111979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.