ABSTRACT

Background: Intensive outpatient treatment could be a promising option for patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Objective: The aim of the study was to test the effectiveness of an eight-day (two-week) intensive treatment for PTSD within a public health care setting (open trial design).

Method: Eighty-nine patients were offered the choice between intensive treatment and spaced individual treatment, of which 34 (38.2%) chose the intensive format. Patients were assessed with self-report batteries and interviews at pre-treatment, start of treatment, post-treatment and three-month follow-up. Each day consisted of individual Prolonged Exposure therapy, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing therapy, group psychoeducation, and physical activity. Therapists rotated between patients.

Results: Between 55 and 62% of the patients showed a clinically significant change (recovery) in symptoms of PTSD, and the effect sizes were large (d = 1.38–1.52). Patients also showed reduction in symptoms of depression and anxiety, along with improved well-being and interpersonal functioning. Changes in social and work functioning were more ambiguous. There were no dropouts, attendance was high, and patients were highly satisfied with the treatment.

Conclusions: The intensive programme was an attractive and effective treatment option for patients with PTSD.

KEYWORDS: Brief, concentrated, EMDR, exercise, massed, PE, preferences, PTSD, trauma

HIGHLIGHTS

More than a third of the patients referred to our clinic chose intensive over spaced treatment.

Patients reported significant reductions in symptoms of PTSD, depression, and anxiety.

None of the patients dropped out of treatment, and they reported high treatment satisfaction.

Abstract

Antecedentes: El tratamiento ambulatorio intensivo podría ser una opción prometedora para los pacientes con trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT).

Objetivo: El objetivo del estudio fue probar la efectividad de un tratamiento intensivo de 8 días (2 semanas) para el TEPT dentro de un entorno de atención de salud pública (diseño de ensayo abierto).

Método: Se ofreció a 89 pacientes elegir entre tratamiento intensivo y tratamiento individual espaciado, de los cuales 34 (38,2%) eligieron el formato intensivo. Los pacientes fueron evaluados con baterías de autoinforme y entrevistas antes del tratamiento, al inicio del tratamiento, después del tratamiento y a los 3 meses de seguimiento. Cada día consistió en terapia de exposición prolongada individual, terapia de reprocesamiento y desensibilización por movimientos oculares, psicoeducación grupal y actividad física. Los terapeutas rotaron entre los pacientes.

Resultados: Entre el 55-62% de los pacientes mostraron un cambio clínicamente significativo (recuperación) en los síntomas del TEPT, y los tamaños del efecto fueron grandes (d = 1,38–1,52). Los pacientes también mostraron una reducción en los síntomas de depresión y ansiedad, junto con mejoría en bienestar y funcionamiento interpersonal. Los cambios en el funcionamiento social y laboral fueron más ambiguos. No hubo abandonos, la asistencia fue alta y los pacientes estaban altamente satisfechos con el tratamiento.

Conclusiones: El programa intensivo fue una opción de tratamiento atractiva y efectiva para pacientes con TEPT.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Breve, concentrado, EMDR, ejercicio, masivo, EP, preferencias, TEPT, trauma

Abstract

背景:对于创伤后应激障碍 (PTSD) 患者,强化门诊治疗可能是一个有希望的选择。

目的:本研究旨在考查公共医护环境中 8 天(2 周)PTSD 强化治疗的有效性(开放试验设计)。

方法:89 例患者在强化治疗和间隔个人治疗之间进行选择,其中 34 例(38.2%)选择强化治疗。在治疗前、治疗开始、治疗后和 3 个月的随访中,通过自我报告问卷和访谈对患者进行评估。每天都包括个人延长暴露疗法、眼动脱敏和再加工疗法、团体心理教育和体育活动。治疗师在患者之间轮换。

结果:55-62% 的患者表现出 PTSD 症状的临床显著变化(恢复),且效应量很大(d = 1.38–1.52)。患者还表现出抑郁和焦虑症状的减轻,以及幸福感和人际交往能力的改善。社会和工作功能的变化更加模糊。没有流失,出勤率高,患者对治疗非常满意。

结论:强化计划对 PTSD 患者来说是一种有吸引力且有效的治疗选择。

关键词: 简短, 集中, EMDR, 运动, 集中, PE, 偏好, PTSD, 创伤

1. Introduction

International guidelines and meta-analyses recommend trauma-focused cognitive–behavioural therapy such as Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE) and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing therapy (EMDR) as first-line treatments for PTSD (Bisson et al., 2019; Lewis, Roberts, Andrew, et al., 2020; National Institue for Health and Care Excellence, 2018). Recent meta-analyses on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) found large effect sizes between 1.2 and 1.5 when comparing exposure-based therapies (including EMDR and PE) with waitlist (Jericho et al., 2022; McLean et al., 2022). However, dropout rates of 18–21% indicate that treatment has potential for improvement (Lewis, Roberts, Gibson, et al., 2020; Varker et al., 2021; both meta-analyses on RCTs). Intensive treatments, commonly operationalized as treatment delivered more than twice weekly (Sciarrino et al., 2020), could be a promising option to more traditional, weekly psychotherapy (e.g. Bruijniks et al., 2020; Hansen et al., 2018). In comparison, the dropout rate shrinks to 5.5% in intensive treatments for PTSD (Sciarrino et al., 2020).

Higher session frequency has been associated with greater symptom reduction in treatment of PTSD (Gutner et al., 2016). A common issue clinicians and patients face in treatment of PTSD is working with avoidance when exposing the patient to emotions, memories, external trauma triggers, and fear of reactions both during and between sessions (Becker et al., 2004; van Minnen et al., 2010). Qualitative studies of patients’ experiences of intensive treatment for PTSD have found that despite short-term discomfort, they experienced that intensified treatment limits distractions and avoidance, and that the experiences of early gains enhance engagement and motivation (Sherrill et al., 2020; Thoresen et al., 2022). The argument for intensifying treatment could therefore especially be valid in the case of PTSD.

Reviews of existing literature on intensive evidence-based therapy for PTSD have documented treatment outcomes equivalent to ordinary outpatient interventions, with a mean effect size of 1.57 (Sciarrino et al., 2020). Furthermore, a study on intensive PE for chronic PTSD patients following multiple trauma and multiple treatment attempts showed a reduction in PTSD symptom scores with large effect sizes at three-month follow-up (d = 1.2–1.3; Hendriks et al., 2018). A systematic review also associates intensive treatment of PTSD with high patient satisfaction and retention of treatment gains 12 months after treatment (Ragsdale et al., 2020). Research literature on the intensive format describes the use of different evidence-based treatments for PTSD, such as cognitive therapy (e.g. Ehlers et al., 2014), PE and EMDR.

van Woudenberg et al. (2018) tested an eight-day inpatient treatment combining both PE and EMDR along with group psychoeducation and group physical activity (PA). The study reported large effect sizes from pre- to post-treatment on PTSD self-report measures (d = 1.31) and clinical interview (d = 1.64). Half of the patients lost their PTSD diagnosis post-treatment, and the dropout rate was low (<3%). The programme has also been shown to be feasible for patients diagnosed with PTSD from childhood sexual abuse with an effect size of 1.2 (self-report) and 1.5 (clinical interview) (Wagenmans et al., 2018). An important feature of the intensive programme was therapist rotation, meaning that the patients met different therapist from session to session. The rotation was hypothesized to prevent therapist drift, hesitation, avoidance, and under-utilization of exposure therapy (Becker et al., 2004; van Minnen et al., 2018). A study exploring the effects of therapist rotation confirmed that it reduced therapists’ negative concerns, fear, and avoidance of trauma-focused exposure (van Minnen et al., 2018). In addition, the patients rated the relationship with the team of therapists as good, and even preferable to having an individual therapist. Two systematic reviews also suggest that PA may have an adjuvant effect on PTSD symptom reduction (Michael et al., 2019; Rosenbaum et al., 2015).

Inspired by this intensive inpatient treatment (van Woudenberg et al., 2018), the programme was adapted to an outpatient format in Norway (Brynhildsvoll Auren et al., 2021). Every element of the original programme was retained, but time appointed for PA and psychoeducation was reduced to fit the schedule of a day programme. The results from this feasibility study (n = 6) showed that the intensive treatment was an attractive treatment option (six out of nine patients chose intensive treatment over spaced treatment), and the overall treatment satisfaction was good. Symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, and depression decreased significantly, and half of the patients no longer met diagnostic criteria for PTSD at three-month follow-up. There were no reports of adverse effects, and none of the patients dropped out of treatment.

The pilot showed promising findings but suffered from a small sample size. Hence, this open trial with a larger sample size was designed to further investigate the effectiveness of the intensive outpatient treatment programme. As far as we know, there is little research on both this treatment format and patients’ treatment preferences for intensive or ordinary treatment formats. The aims of the study were to explore changes in symptoms of PTSD and related symptoms and functioning, the attractiveness of the intensive treatment programme, attendance rates, and patient satisfaction. The main hypothesis was that the treatment would result in a significant reduction in patients’ PTSD symptoms.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and procedure

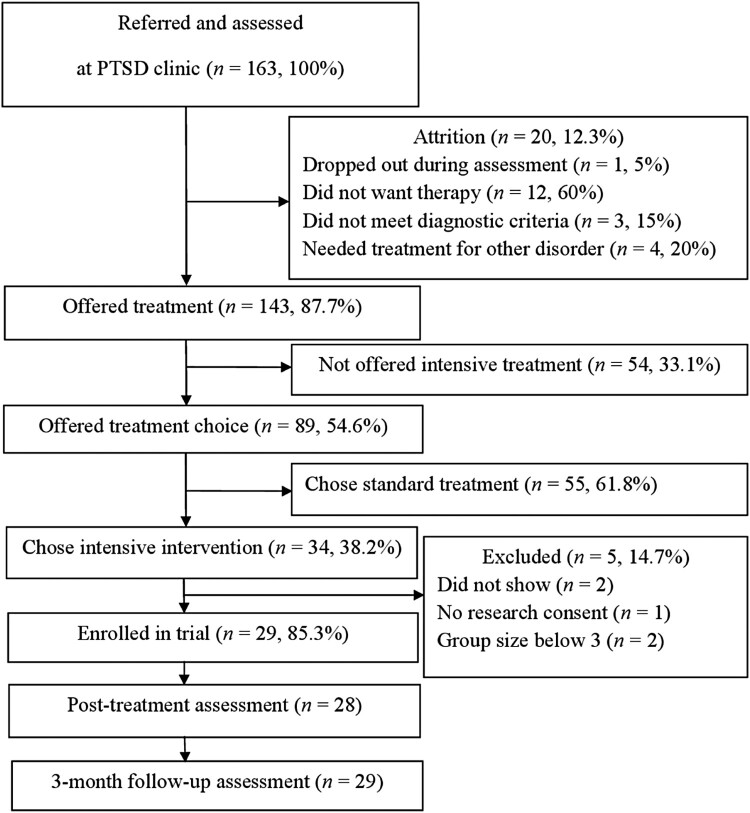

Participants were patients referred to a public regional outpatient clinic specializing in treatment of PTSD between January 2019 and March 2021. To receive treatment at the clinic, patients had to be 18 years or older, diagnosed with a trauma-related disorder (e.g. PTSD or dissociative disorders) and had had at least one previous attempt at treating the trauma-related disorder. A total of 163 patients met for diagnostic assessment during the referral period, of which 143 met the clinic’s inclusion criteria and were offered treatment. The patients not offered treatment (n = 20) either did not want therapy (60%), did not meet diagnostic criteria of PTSD (15%), needed treatment for other diagnosis (20%), or dropped out during assessment (5%). Comorbid disorders were not an exclusion criteria, except for patients in need of treatment due to psychosis, severe drug addiction, or acute suicidality. Therapists working at the clinic conducted the diagnostic evaluations. The assessment included a medical and mental health history and completion of relevant self-report forms. Diagnosis was determined using diagnostic interviews, either the ADIS-IV (Brown et al., 1994) or the MINI Plus 5.0 interview (Sheehan et al., 1998), and the PTSD Symptom Scale Interview (PSS-I; Foa et al., 1993).

Of the 143 patients offered treatment at the clinic (all of which met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD on both PSS-I and PCL-5), 54 patients (37.8%) were not offered intensive treatment. The main reasons were: patients evaluated as being in need of more tailored treatment because of severe comorbidity (n = 21), patients needed less extensive treatment (n = 15), insufficient Norwegian language skills (n = 13), and unstable attendance (n = 4). The remaining 89 patients were offered a choice between the time-limited eight-day intensive treatment with therapist rotation, and a more open-ended weekly therapy with a single therapist (i.e. treatment as usual at the clinic). A total of 55 (61.8%) chose standard treatment. Out of the 55, 40 patients gave one or more reasons for not wanting to participate in the intensive treatment. These reasons were: practical concerns like studies, work or care for children (n = 16), therapist rotation (n = 7), patients not wanting exposure-based treatment (n = 6), waiting time (n = 4), the programme was considered too challenging (n = 4), group elements (n = 3), physical illness, pain or fatigue (n = 3), the time limit of the programme was considered too brief (n = 2), and other reasons (n = 4).

Thirty-four patients (38.2% of those offered treatment) chose intensive treatment. Of these, one did not consent to participate in research and two never showed up for treatment. One group ended up consisting of only two patients and were excluded from the analysis because the group size deviated too much from the treatment protocol. This left 29 eligible study participants, of which one did not respond to self-reports at post-treatment but participated at the three-month follow-up. Figure 1 summarizes the patient flow from referral to follow-up assessment.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for study participants.

After inclusion, patients received individual preparatory sessions in the interim between assessment and the start of the intensive treatment programme. The timing of the preparatory sessions was not structured, as the assessors and patients were free to schedule sessions themselves. The treatment programme was scheduled quarterly. The preparatory sessions included the first steps from the PE manual (trauma-interview, psychoeducation, formulation of an anxiety hierarchy, mapping safety behaviours, and deciding targets for imaginary exposure). On average, patients received 3.1 (SD = 0.9) preparatory sessions. The majority also had a 45-minute consultation with the physiotherapist, who informed about the PA component of the programme and identified potential needs for customization. Six patients also received additional sessions (M = 2.5, SD = 1.2) in the interim between preparation and start of the intensive treatment programme. Four of these patients had their treatment postponed due to national regulations during a COVID-19 lockdown. The extra sessions included themes like relationship difficulties, crisis management, and social work. Average waiting time from assessment until treatment start was calculated to be 43.4 days (SD = 23.9). Two patients who themselves wanted to postpone treatment (one year and half a year) were excluded from calculation of waiting time.

The sample (N = 29) had a mean age of 38.03 (SD = 13.20) years and an uneven gender distribution (2 male and 27 female). All participants spoke Norwegian adequately, 24 as their first language. Twenty patients (69.0%) received social security benefits. Number of prior psychological treatments (defined as minimum three months of psychotherapy) was 3.1 (SD = 1.6, range = 1–6). A total of 82.7% (n = 24) had previous psychotropic treatments. Forty-eight per cent (n = 14) had current psychotropic medication including benzodiazepines (n = 8), antidepressants (n = 6), antipsychotics (n = 3), and stimulants (n = 1). A wide range of traumas was reported, including terrorist acts, witnessing murder, rape, domestic violence, and childhood sexual and physical abuse. Most patients (n = 26, 89.7%) reported multiple traumatic events, while three reported a single traumatic event. Twenty-one (72.4%) had experienced sexual trauma. The mean number of years since the first traumatic incidence was 13.6 (SD = 10.5), within a range of 1.5–44 years. The most common comorbid disorder was major depression (n = 10). Other comorbid diagnoses were avoidant personality disorder, borderline personality disorder, ADHD, OCD, social phobia, unspecified eating disorder and substance abuse disorder (all of which, n = 1). A summary of the group’s background information is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample.

| % | n | % | N | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 93.1 | 27 | Single | 44.8 | 13 | |

| Ethnic minority | 17.2 | 5 | Cohabitant | 41.4 | 12 | |

| Full time work | 13.8 | 4 | Current psychotropic medication | 48,3 | 14 | |

| Part time work | 6.9 | 2 | Comorbid disorder | 41.4 | 12 | |

| Sick leave | 20.7 | 6 | Previous drug abuse | 24.1 | 7 | |

| Benefits | 51.7 | 15 | Current drug abuse | 3.4 | 1 | |

| Student | 6.9 | 2 |

When comparing demographics between patients who declined and accepted the treatment, the patients who accepted treatment were slightly older (38.0 [13.2] vs. 33.3 [11.5]), t(79) = 1.70, p = .046, and had a greater amount of previous treatments (3.1 [1.6] vs. 2.3 [1.2]), t(75) = 2.38, p = .022. Participants also had higher rates of comorbidity than non-participants (58.6% vs. 31.9%), x2 = 5.25, p = .022. There was no significant sex difference between the two groups, but there was a slight tendency towards more men declining participation (ratio of men in each group was 6.9% and 23%), x2 = 3.41, p = .065. There were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to belonging to a minority group (p = .54), being single (p = .49), using psychotropics (p = .94), past drug abuse (p = .24), current drug abuse (p = .92), or working/studying (p = .22).

2.2. Treatment

The treatment programme consisted of eight days in two consecutive weeks, four days each week. Each day started with 90 min of individual PE, followed by group PA for 45 min, and a 45-minute lunch break. After lunch, patients received 90 min of individual EMDR, before the day ended with 45 min of group psychoeducation.

Based on the PE-protocol (Foa et al., 2007), patients were instructed to imagine and recount aloud the trauma memory as lively and detailed as possible. After the in-session exposure, focus turned to processing this experience to alter negative trauma-related thoughts. For a few patients, one session was used as an in vivo exposure (e.g. exposure to the place the trauma happened). Every patient received in vivo exposure exercises to complete at home between treatment days, in addition to listening to audio recordings of the imagery exposure. The EMDR sessions followed the EMDR protocol (Shapiro et al., 2018) focusing on desensitization, installation, body scan, and closure, targeting trauma memories, triggers and future templates of anxiety-provoking situations.

Both the psychoeducation and the PA were administered in a group setting. The group size varied between three to six patients. The psychoeducation was based on the PE protocol and included topics such as defining normal reactions to trauma, the rationale for exposure treatment, avoidance, negative thoughts, feelings, self-esteem, and relapse prevention. There was also added an element about the benefits of PA. The PA was administered in a group by a physiotherapist. Patients were instructed in a diverse set of physical exercises, including step aerobics, medicine ball exercises, punching bag exercises, hiking on a nearby trail, circuit training, and badminton. The goal was to give the patients varied tasks that demanded attention, activated the whole body, and demanded use of muscular strength to facilitate the experience of mastery and strength. The exercises were designed to be of moderate intensity and to fit everyone independent of physical fitness. Fitness level was not monitored. After completing the two-week intensive treatment programme, the patients received individual follow-up sessions after one week (phone call), two weeks, and three and six months, focusing on relapse prevention.

2.3. Therapists

The therapists responsible for the individual therapy were eleven clinical psychologists and one psychiatrist. All therapists had completed at least a three-day EMDR training workshop. Eleven out of 12 therapists had attended a four-day workshop in PE, the last one was trained in trauma-focused cognitive behaviour therapy. Each patient met four to seven therapists depending on their rotation schedule. The therapists met twice daily to inform each other of the therapy process, discuss the next session, and strengthen adherence to therapy protocols.

2.4. Outcome measures

A structured diagnostic interview for PTSD and a varied battery of self-report questionnaires were used to measure symptoms pre-treatment, post-treatment, and three months after treatment. The self-report battery was also administered at treatment start. Independent assessors conducted the post-treatment diagnostic interviews. Included outcome measures were the following:

The PSS-I (Foa et al., 1993) was used to assess post-traumatic symptoms and diagnostic status at post-treatment and follow-up. The diagnostic interview updated to DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, the PSS-I-5, was not available in Norwegian when the study started. The PSS-I consists of 17 items in accordance with DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Each item is scored on a scale from 0 to 3 indicating frequency of symptoms, resulting in a total score from 0 to 51. For the PSS-I there is not an official clinical cut-off score, but for the 20-item PSS-I-5 a cut-off of 23 points has been suggested (Foa et al., 2016). The cut-off was set at 20 and the reliable change index (RCI) to 8 points for the 17-item version used in this study. Cronbach’s alpha was .75.

The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Blevins et al., 2015) was used to assess self-reported presence and severity of PTSD symptoms corresponding with DSM-5 criteria for PTSD, using 20 items scaled from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Total scores range from 0 to 80. The cut-off was set at 32 and the RCI at 10 points as used in the IAPT programme.

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck et al., 1988) and the second edition of the Beck Depression inventory (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996) were used to assess severity of anxiety and depression symptoms. Both the BAI and BDI-II consist of 21 items rated on a scale from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating higher levels of depression or anxiety. Threshold values on the BAI are typically minimal (0–7), mild (8–15), moderate (16–25), and severe (26–63), while for the BDI-II they are set as mild (14–19), moderate (20–28), and severe (29–63). This study set a cut-off of scoring below 15 on the BDI-II with a RCI of 9 points. For the BAI, the cut-off was set at 11 and the RCI at 12 points. Cronbach’s alpha was .84.

The Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS; Mundt et al., 2002) assessed the impact of the patients’ general mental health on their ability to function at work, at home, in social leisure and personal relationships. Five items are rated using a scale from 0 (not at all) to 8 (very severely). Lower scores indicate higher functioning. Scores lower than 15 are considered as mild, moderate (15-30), and severe (>30). This study set the cut-off to 17 and the RCI to 8 points. Cronbach’s alpha was .77.

The five-item World Health Organization Well-Being Index (WHO-5; Topp et al., 2015) assessed the patients’ subjective psychological well-being. Five positively phrased items (e.g. ‘I have felt cheerful and in good spirits’), are rated on a scale from 0 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time), as to how much the individual evaluates it applying to them. The scores are multiplied by four, resulting in a scale ranging from 0 to 100, indicating minimum (0) to maximum (100) well-being. A cut-off score of 50 is often used for screening purposes and thresholds for clinically relevant change have ranged from 10 to 15 points. For this study, we set the cut-off below 29 (similar as in a study on depression by Löwe et al., 2004) and the RCI at 10 points. Cronbach’s alpha was .83.

The Inventory of interpersonal problems (IIP-64; Alden et al., 1990) assessed levels of interpersonal distress using 64 items, rated on a 0–4 scale. These results are presented as mean item scores. Higher scores indicate higher levels on interpersonal problems. A cut-off value of 1.03 and a RCI of at least 0.38 was used, as commonly used in studies using Norwegian samples. Cronbach’s alpha was .89.

To assess patients’ satisfaction with the treatment, the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 was administered at post-treatment (CSQ-8; Larsen et al., 1979). The CSQ-8 consists of eight items rated on a scale from 1 to 4. Higher scores indicate higher satisfaction. Cronbach’s alpha was .91.

2.5. Statistical analyses

There were small amounts of missing data. For the outcome measures, there were 5.24% incomplete values. Little’s MCAR test suggested that data were missing completely at random (x2 = 161.62, p = .45). Most missing data was from the second assessment (when starting treatment) as three to four patients had missing values. One patient did not complete post-treatment questionnaires but participated in the three-month follow-up assessment. For follow-up assessment, there was one missing value on BDI-II, BAI, IIP-64, and WSAS. Different approaches for dealing with missing data were used. For the main analyses, we used the last observation carried forward method for imputing follow-up values (post-treatment scores were used as follow-up scores). The same method was used for missing start scores (pre-treatment scores used as start treatment scores). For the missing post-treatment values, we imputed values using their follow-up scores (follow-up scores were used as post-treatment scores). To ensure that choice of imputation method did not affect the results, the analyses were repeated without imputing missing values (raw scores only) and when using the expectation-maximization method.

A repeated measures ANOVA was used to test for changes in symptoms and functioning following treatment. The analyses used data from four assessments (pre-treatment, start treatment, post-treatment, and follow-up). However, the analysis using PSS-I had three assessments (pre, post, and follow-up). Effect sizes were reported using partial eta squared values and interpreted as small (.01), medium (.06), or large (.14). Cohen’s d using pooled standard deviations was also calculated based on pre-treatment and follow-up scores. Finally, the treatment effect was evaluated using different treatment response criteria such as 35% change, scoring below cut-off, reliable change, and clinically significant change/recovery (Jacobson & Truax, 1991). Cut-off scores for clinical cut-off and the reliable change index were either based on existing standards or calculated based on clinical and non-clinical distributions and reliability of the measure.

2.6. Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Norwegian Regional committees for medical and health research ethics (REK 2019/245). Informed consent to participate in the research study was obtained both written and verbally. A patient group representative participated in the planning and approval of the research project.

3. Results

Of the patients offered the time-limited intensive treatment or spaced treatment, 38.2% (n = 34) chose the intensive treatment programme. All participants that started the treatment followed through to completion (N = 29). Three per cent of both the PE and EMDR sessions were not attended. According to national regulations during the COVID-19 lockdown, one treatment group had to alter the administration of PA from group to individual. There was one adverse event reported during the study (intoxication followed by hospitalization for observation before continuing the intensive treatment).

The mean scores for the outcome measures at pre-treatment suggested that the sample had clear symptoms of PTSD and severe symptoms of depression and anxiety (see Table 2). The sample also reported moderate impairment in work and social functioning, well-being, and interpersonal functioning.

Table 2.

Changes in symptoms and functioning from pre-treatment to three-month follow-up.

| M (SD) | F | P | d | µp2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Start | Post | 3-m f-u | A | B | C | ||||

| PSS-I | 31.40 (8.21) | – | 18.55 (10.06) | 15.90 (11.88) | 44.13 | <.001 | 1.52 | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.60 |

| PCL-5 | 49.79 (11.23) | 50.69 (11.44) | 34.21 (14.84) | 30.00 (16.93) | 30.32 | <.001 | 1.38 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.54 |

| BDI-II | 29.66 (10.35) | 28.21 (12.17) | 19.66 (10.57) | 18.93 (13.83) | 13.69 | <.001 | 0.88 | 0.33 | 0.35 | 0.33 |

| BAI | 26.55 (12.33) | 26.07 (13.44) | 16.66 (12.33) | 17.07 (13.48) | 21.48 | <.001 | 0.73 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.44 |

| WSAS | 21.52 (8.26) | 21.72 (8.18) | 19.41 (7.60) | 18.66 (9.73) | 2.37 | .100 | 0.32 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.09 |

| WHO-5 | 33.24 (17.17) | 28.69 (18.36) | 39.45 (19.38) | 44.14 (20.77) | 5.91 | .003 | −0.57 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 0.18 |

| IIP-64 | 1.74 (0.50) | 1.74 (0.49) | 1.45 (0.47) | 1.39 (0.57) | 14.06 | <.001 | 0.65 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.33 |

Note: Effect sizes (µp2) are reported according to the imputation method used: A = imputation using last observation carried forward/backward; B = raw data (no imputation); C = expectation maximization method. F and p values are calculated using method A. PSS-I = PTSD Symptom Scale – Interview for DSM-IV, PCL-5 = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5, BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory, BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory, WSAS = Work and Social Adjustment Scale, WHO-5 = The World Health Organisation – Five Well-Being Index, IIP-64 = Inventory of Interpersonal Problems.

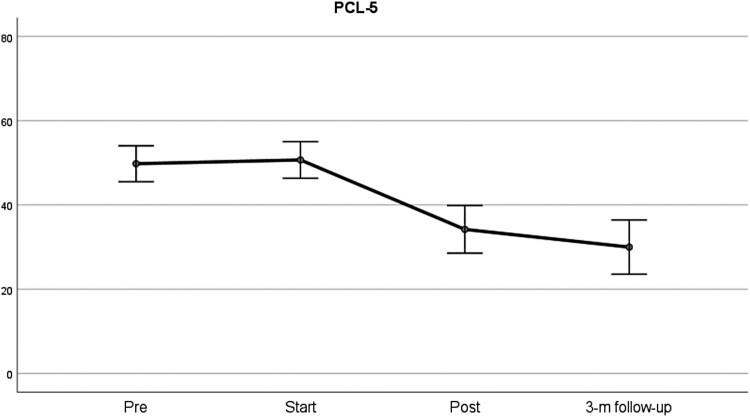

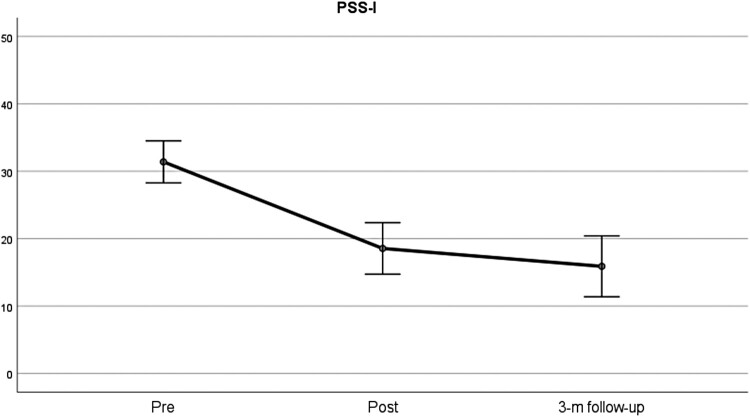

Symptoms were stable from the first assessment to start of treatment. Symptoms declined significantly from starting treatment to post-treatment and remained stable at follow-up. Effect sizes were large (µp2 from .33 to .61) for all outcome measures, except for work and social functioning (WSAS) which showed a medium effect. Unlike the other outcome measures, WSAS did not show a significant change following treatment, although the pairwise comparison indicated a significant change from start to follow-up (p = .034). The largest effects were observed for trauma symptoms (µp2 from .52 [self-report] to .61 [interview]), followed by anxiety symptoms (µp2 = .43), depression (µp2 = .33) and interpersonal problems (µp2 = .33). Effect sizes did not vary much depending upon choice of imputation method. The most notable difference was for WHO-5 as using unimputed data gave a higher effect size than imputed data (µp2 = .17 vs. .29). The results of the repeated measures ANOVA are summarized in Table 2. Figures 2 and 3 also summarize these effects graphically for the two main outcome measures (the PSS-I and PCL-5).

Figure 2.

Changes in PTSD symptoms from pre-treatment to follow-up based on the PSS-I. Note: Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 3.

Changes in PTSD symptoms from pre-treatment to follow-up as measured with the PCL-5. Note: Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Different methods were used for evaluating treatment response rates. The first method involved scoring below a suggested clinical cut-off and the second calculated a reliable change index. The third method combined the first two methods, as participants were classified as having achieved clinically significant change (recovery) if they scored below cut-off and met the criterion for reliable change. The last method involved obtaining at least 35% change. Table 3 summarizes these results. The results supported findings from the repeated measures ANOVA suggesting that the biggest improvement occurred specifically for PTSD symptoms. Fifty-five to 62% achieved clinically significant change related to symptoms of PTSD. The recovery rates for the secondary outcome measures were somewhat lower but 45% achieved recovery from depression and 52% had a clinically significant change with respect to well-being. The lowest recovery rates were observed for anxiety, interpersonal problems, work- and social functioning (rates from 14 to 21%). There were no patients showing signs of deterioration (35% symptom increase) with respect to PTSD symptoms, but some (10.3%) had an increase in depression symptoms and 13.8% reported reduced well-being.

Table 3.

Treatment response rates (from start of treatment to three-month follow-up) in percentages.

| 35% improvement | 35% deterioration | Clinical cut-off | Reliable change | CSC/recovery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSS-I | 65.5% | 0.0% | 62.1% | 79.3% | 62.1% |

| PCL-5 | 58.6% | 0.0% | 55.2% | 72.4% | 55.2% |

| BDI-II | 51.7% | 10.3% | 51.7% | 58.6% | 44.8% |

| BAI | 48.3% | 0.0% | 58.6% | 34.5% | 20.7% |

| WSAS | 34.5% | 6.9% | 44.8% | 24.1% | 24.1% |

| IIP-64 | 27.6% | 3.4% | 24.1% | 44.8% | 13.8% |

| WHO-5 | 48.3% | 13.8% | 72.4% | 62.1% | 51.7% |

Note: CSC = clinically significant change (recovery). PSS-I = PTSD Symptom Scale – Interview for DSM-IV, PCL-5 = PTSD Checklist for DSM-5, BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory, BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory, WSAS = Work and Social Adjustment Scale, WHO-5 = The World Health Organisation – Five Well-Being Index, IIP-64 = Inventory of Interpersonal Problems.

Concerning loss of diagnosis, 51.7% (n = 15) no longer met criteria for PTSD at post-treatment, and 62.1% (n = 18) at follow-up when using PCL-5 criteria. PCL-5 criteria entailed scores of 2 or more as an indication of a symptom endorsed. To meet diagnostic criteria, one would require at least one endorsed symptom from items 1–5 (intrusion), one from items 6–7 (avoidance), two from items 8–14 (cognitions and mood), and two from items 15–20 (arousal). When using PSS-I criteria, 44.8% (n = 13) no longer met criteria for PTSD at post-treatment, and 51.7% (n = 15) at follow-up. PSS-I criteria entail scoring 1 or more as an indication of symptom endorsed. To meet diagnostic criteria, one would require at least one symptom endorsed from items 1–5 (re-experiencing), at least three from items 6–12 (avoidance), and at least two from items 13–17 (arousal).

3.1. Treatment satisfaction

The scores on the CSQ-8 suggested that most patients were happy or very happy with the treatment, but one patient had more negative scores. The lowest scores were concerning whether the treatment met the needs of the patient, as 27.6% reported that only a few of their needs had been met. The mean score for the CSQ-8 was high (M = 27.14, SD = 4.16). A summary of the CSQ-8 scores is displayed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Client satisfaction in percentages.

| Low satisfaction | High satisfaction | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1. Quality of service | 3.4% (1) | 0.0% (0) | 55.2% (16) | 41.4% (12) |

| 2. Kind of service | 3.4% (1) | 3.4% (1) | 58.6% (17) | 34.5% (10) |

| 3. Met needs | 0.0% (0) | 27.6% (8) | 48.3% (14) | 24.1% (7) |

| 4. Recommend to a friend | 0.0% (0) | 0.0% (0) | 13.8% (4) | 86.2% (25) |

| 5. Amount of help | 6.9% (2) | 6.9% (2) | 41.4% (3) | 44.8% (13) |

| 6. Dealt with problems | 0.0% (0) | 3.4% (1) | 34.5% (10) | 62.1% (18) |

| 7. Overall satisfaction | 3.4% (1) | 0.0% (0) | 51.7% (15) | 44.8% (13) |

| 8. Would come back | 0.0% (0) | 6.9% (2) | 34.5% (10) | 58.6% (17) |

Note: Total scores ranged from 13 to 32. Possible range of scores is 8–32. Higher scores indicate greater client satisfaction.

3.2. Patients’ need for further treatment

Eighteen patients received only the scheduled follow-up sessions, while nine received additional sessions at the clinic after completing the intensive programme. The number of sessions ranged from one to eight extra sessions (M = 2.9, SD = 2.3). Out of the additional sessions, 12% of the sessions targeted further PTSD treatment, 22% depressive symptoms, 22% relational stressors, 19% self-esteem issues, 12% various crisis, and 12% discussions of further treatment. Two patients were referred to treatment for other presenting problems.

4. Discussion

The results supported the main hypothesis, that the intensive outpatient treatment programme would be associated with significant improvement in symptoms of PTSD at post-treatment and three-month follow-up. A total of 55–62% achieved a clinically significant change in PTSD symptoms. Patients also reported reduction in symptom severity of both depression and anxiety, along with both improved well-being and interpersonal functioning. The observed effect sizes were large. Reported changes in work- and social functioning were more ambiguous. One possible explanation for this could be that a relatively large number of patients received disability benefits (52%). The patients reported to be highly satisfied with the treatment, there was no dropout, and the sessions had high attendance rates. The intensive treatment format appeared to be an attractive treatment option, as 38.2% chose the time-limited intensive treatment programme over standard open-ended individual outpatient treatment. There was a tendency toward patients preferring intensive treatment being older, with a greater number of previous treatments, and having more comorbidity.

These promising results show that intensive trauma-focused therapy can be efficiently delivered in an outpatient programme involving therapist rotation, combination of therapeutic approaches, physical activity, and both individual and group elements. All patients in this study population had multiple treatments attempts, and 90% reported multiple traumas. The reduction in reported symptoms of PTSD at three-month follow-up as assessed with both self-report (d = 1.38) and clinical interview (d = 1.52) are comparable with the original inpatient treatment programme with effect sizes ranging from 1.31 to 1.64 at post-treatment (van Woudenberg et al., 2018). The study’s effect sizes are also comparable with mean effect size in a review of intensive treatment programmes of 1.57 (Sciarrino et al., 2020), and spaced treatments 1.2 to 1.5 (Jericho et al., 2022; McLean et al., 2022). Meta-analyses typically show lower effect sizes for RCT studies than for open trials. However, for PTSD trials there are indications that study quality may not affect outcome to such an extent (Morina et al., 2021), and a related meta-analysis found no moderating effect of study design (Grubaugh et al., 2021).

In the present study, 52–62% lost their PTSD diagnosis at follow-up. This is on par with former studies. In a systematic review of intensive outpatient programmes loss of PTSD diagnosis ranged from 30 to 66% across studies (Ragsdale et al. 2020). The results provide further support for the notion that intensive treatment could be effective for patients with multiple traumas, severe PTSD symptomatology, and a history of treatment resistance (Wagenmans et al., 2018; Zoet et al., 2018).

The intensity of the treatment and rotation of therapist was not associated with deterioration of post-traumatic symptoms, which is in line with earlier research (van Woudenberg et al., 2018). However, some patients (10.3–13.8%) did report deterioration on measures of depressive symptoms and well-being, and there was one adverse event reported. Earlier studies comparing intensive treatment with spaced treatment have not found any significant difference in reported adverse events (Foa et al., 2018). Thus, it appears that patients tolerated the high load of trauma-focused treatment delivered by rotating therapists in an outpatient setting.

Research on intensive treatment for PTSD has shown substantially lower dropout rates than treatment with standard session frequency (Lewis, Roberts, Gibson, et al., 2020; Ragsdale et al., 2020; Sciarrino et al., 2020). This is also evident in this study as all 29 participants completed treatment. Despite a clinical population with severe impairment, the treatment attendance was very high. The high attendance can be assumed to be explained by advantages with intensive treatment, for instance leaving less time for worry and avoidance developing between sessions. The experience of frequent support and early gains could also be an important factor in enhancing motivation for treatment. Furthermore, the experience of support from other participants may increase treatment adherence (Ragsdale et al., 2020; Sherrill et al., 2020; Thoresen et al., 2022). Nevertheless, with the non-randomized design, we cannot conclude whether the high attendance is caused by the treatment design or the freedom to choose between standard and intensive treatment. The excluded patients and those preferring spaced treatment could have influenced the attendance and dropout rates if included.

The intensive treatment programme was not suitable for all referred patients. Thirteen patients were excluded because of insufficient Norwegian language skills to such an extent that they would need an interpreter. Fifteen were excluded because they needed less treatment, and 25 because of severe comorbidity and unstable attendance. They were therefore given more tailored individual treatment. In total, 38.2% of patients who were offered the intensive treatment chose to participate. This supports the assumption that a portion of patients prefers intensive treatment if given a choice (Ragsdale et al., 2020).

Out of the patients who rejected the intensive treatment, our data implied that about half declined to attend because of practical reasons such as work, school, and care for children. The other half declined due to elements in the intensive treatment programme, for instance therapist rotation, group activities, the intensity, or because of the time-limitation of the programme. The tendency for patients to prefer individual over group therapy was also shown in a systematic review of preferences in treatment of trauma (Simiola et al., 2015). A thematic analysis of patient experience of the present treatment programme showed that many participants uttered scepticism towards both the element of therapist rotation and group activities before starting therapy, but highlighted the importance of these elements in hindsight (Thoresen et al., 2022). The rotation of therapists was reported to provide them with a maintained focus on therapeutic tasks along with different perspectives and relational experiences. The group elements were experienced as important for normalization of symptoms and creating a supportive sense of unity within the patient group.

There are limitations to this study such as a small group size, lack of randomization and a control condition. This implies that although there was no significant change in symptom severity during the baseline period, we cannot conclude about causation. Likewise, we cannot conclude about the contribution of the different interventions (PE, EMDR, group PA, group psychoeducation) due to the combined treatment design. Future studies using dismantling designs or randomized controlled trials are recommended. Furthermore, a comparison with treatment as usual would be interesting, we unfortunately were in lack of structured data for a meaningful analysis. The limitations notwithstanding, this study contributes to the growing evidence that intensive treatment is a feasible option to spaced treatment for PTSD. Furthermore, it shows that efficient intensive treatment including therapist rotation, combination of different therapeutic methods, physical activity, and group activities, can be conducted within a public healthcare outpatient clinic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

References

- Alden, L. E., Wiggins, J. S., & Pincus, A. L. (1990). Construction of circumplex scales for the inventory of interpersonal problems. Journal of Personality Assessment, 55(3–4), 521–536. 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G., & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 893–897. 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II (Vol. 1). Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, C. B., Zayfert, C., & Anderson, E. (2004). A survey of psychologists’ attitudes towards and utilization of exposure therapy for PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42(3), 277–292. 10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00138-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisson, J. I., Berliner, L., Cloitre, M., Forbes, D., Jensen, T. K., Lewis, C., Monson, C. M., Olff, M., Pilling, S., Riggs, D. S., Roberts, N. P., & Shapiro, F. (2019). The international society for traumatic stress studies New guidelines for the prevention and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: Methodology and development process. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(4), 475–483. 10.1002/jts.22421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. 10.1002/jts.22059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T., Di Nardo, P., & Barlow, D. (1994). Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (ADIS-IV). Psychological Corporation. In: Graywind Publications Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Bruijniks, S. J., Lemmens, L. H., Hollon, S. D., Peeters, F. P., Cuijpers, P., Arntz, A., Dingemanse, P., Willems, L., van Oppen, P., & Twisk, J. W. (2020). The effects of once-versus twice-weekly sessions on psychotherapy outcomes in depressed patients. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 216(4), 222–230. 10.1192/bjp.2019.265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brynhildsvoll Auren, T. J., Gjerde Jensen, A., Rendum Klæth, J., Maksic, E., & Solem, S. (2021). Intensive outpatient treatment for PTSD: A pilot feasibility study combining prolonged exposure therapy, EMDR, physical activity, and psychoeducation. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), Article 1917878. 10.1080/20008198.2021.1917878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, A., Hackmann, A., Grey, N., Wild, J., Liness, S., Albert, I., Deale, A., Stott, R., & Clark, D. M. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of 7-day intensive and standard weekly cognitive therapy for PTSD and emotion-focused supportive therapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(3), 294–304. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13040552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E. B., Hembree, E. A., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2007). Treatments That Work. Prolonged Exposure Therapy for PTSD: Emotional Processing of Traumatic Experiences: Therapist Guide. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E. B., McLean, C. P., Zang, Y., Rosenfield, D., Yadin, E., Yarvis, J. S., Mintz, J., Young-McCaughan, S., Borah, E. V., & Dondanville, K. A. (2018). Effect of prolonged exposure therapy delivered over 2 weeks vs 8 weeks vs present-centered therapy on PTSD symptom severity in military personnel: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 319(4), 354–364. 10.1001/jama.2017.21242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E. B., McLean, C. P., Zang, Y., Zhong, J., Rauch, S., Porter, K., Knowles, K., Powers, M. B., & Kauffman, B. Y. (2016). Psychometric properties of the posttraumatic stress disorder symptom scale interview for DSM–5 (PSSI–5). Psychological Assessment, 28(10), 1159–1165. 10.1037/pas0000259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E. B., Riggs, D. S., Dancu, C. V., & Rothbaum, B. O. (1993). Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 6(4), 459–473. 10.1002/jts.2490060405 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grubaugh, A. L., Brown, W. J., Wojtalik, J. A., Myers, U. S., & Eack, S. M. (2021). Meta-analysis of the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in adults with comorbid severe mental illness. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 82(3), Article 33795. 10.4088/JCP.20r13584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutner, C. A., Suvak, M. K., Sloan, D. M., & Resick, P. A. (2016). Does timing matter? Examining the impact of session timing on outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(12), 1108–1115. 10.1037/ccp0000120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, B., Hagen, K., Öst, L.-G., Solem, S., & Kvale, G. (2018). The Bergen 4-Day OCD treatment delivered in a group setting: 12-month follow-up [original research]. Frontiers in Psychology, 639. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, L., Kleine, R. A. D., Broekman, T. G., Hendriks, G.-J., & Minnen, A. V. (2018). Intensive prolonged exposure therapy for chronic PTSD patients following multiple trauma and multiple treatment attempts. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), Article 1425574. 10.1080/20008198.2018.1425574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 12–19. 10.1037/10109-042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jericho, B., Luo, A., & Berle, D. (2022). Trauma-focused psychotherapies for post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 145(2), 132–155. 10.1111/acps.13366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, D. L., Attkisson, C. C., Hargreaves, W. A., & Nguyen, T. D. (1979). Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: Development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning, 2(3), 197–207. 10.1016/0149-7189(79)90094-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, C., Roberts, N. P., Andrew, M., Starling, E., & Bisson, J. I. (2020). Psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), Article 1729633. 10.1080/20008198.2020.1729633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, C., Roberts, N. P., Gibson, S., & Bisson, J. I. (2020). Dropout from psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), Article 1709709. 10.1080/20008198.2019.1709709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löwe, B., Spitzer, R. L., Gräfe, K., Kroenke, K., Quenter, A., Zipfel, S., Buchholz, C., Witte, S., & Herzog, W. (2004). Comparative validity of three screening questionnaires for DSM-IV depressive disorders and physicians’ diagnoses. Journal of Affective Disorders, 78(2), 131–140. 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00237-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean, C. P., Levy, H. C., Miller, M. L., & Tolin, D. F. (2022). Exposure therapy for PTSD: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 91, 102–115. 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael, T., Schanz, C. G., Mattheus, H. K., Issler, T., Frommberger, U., Köllner, V., & Equit, M. (2019). Do adjuvant interventions improve treatment outcome in adult patients with posttraumatic stress disorder receiving trauma-focused psychotherapy? A systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), Article 1634938. 10.1080/20008198.2019.1634938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morina, N., Hoppen, T. H., & Kip, A. (2021). Study quality and efficacy of psychological interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychological Medicine, 51(8), 1260–1270. 10.1017/S0033291721001641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundt, J. C., Marks, I. M., Shear, M. K., & Greist, J. M. (2002). The work and social adjustment scale: A simple measure of impairment in functioning. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(5), 461–464. 10.1192/bjp.180.5.461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institue for Health and Care Excellence . (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116/resources/posttraumatic-stress-disorder-pdf-66141601777861 [PubMed]

- Ragsdale, K. A., Watkins, L. E., Sherrill, A. M., Zwiebach, L., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2020). Advances in PTSD treatment delivery: Evidence base and future directions for intensive outpatient programs. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 7(3), 291–300. 10.1007/s40501-020-00219-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, S., Vancampfort, D., Steel, Z., Newby, J., Ward, P. B., & Stubbs, B. (2015). Physical activity in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 230(2), 130–136. 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sciarrino, N. A., Warnecke, A. J., & Teng, E. J. J. J. O. T. S. (2020). A systematic review of intensive empirically supported treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(4), 443–454. 10.1002/jts.22556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, F., Korn, D. L., Stickgold, R., Maxfield, L., & Smyth, N. J. (2018). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapy (3rd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., Hergueta, T., Baker, R., & Dunbar, G. C. (1998). The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(Suppl 20), 22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherrill, A. M., Maples-Keller, J. L., Yasinski, C. W., Loucks, L. A., Rothbaum, B. O., & Rauch, S. A. M. (2020). Perceived benefits and drawbacks of massed prolonged exposure: A qualitative thematic analysis of reactions from treatment completers. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 14(5), 862–870. 10.1037/tra0000548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simiola, V., Neilson, E. C., Thompson, R., & Cook, J. M. (2015). Preferences for trauma treatment: A systematic review of the empirical literature. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 7(6), 516–524. 10.1037/tra0000038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoresen, I. H., Brynhildsvoll Auren, T. J., Rendum Klæth, J., Gjerde Jensen, A., Engesæth, C., & Langvik, E. O. (2022). Intensive outpatient treatment for PTSD: A thematic analysis of patient experience. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1). 10.1080/20008198.2022.2043639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topp, C. W., Østergaard, S. D., Søndergaard, S., & Bech, P. (2015). The WHO-5 well-being index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(3), 167–176. 10.1159/000376585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Minnen, A., Hendriks, L., Kleine, R. D., Hendriks, G.-J., Verhagen, M., & De Jongh, A. (2018). Therapist rotation: A novel approach for implementation of trauma-focused treatment in post-traumatic stress disorder. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1492836–1492836. 10.1080/20008198.2018.1492836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Minnen, A., Hendriks, L., & Olff, M. (2010). When do trauma experts choose exposure therapy for PTSD patients? A controlled study of therapist and patient factors. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(4), 312–320. 10.1016/j.brat.2009.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Woudenberg, C., Voorendonk, E. M., Bongaerts, H., Zoet, H. A., Verhagen, M., Lee, C. W., van Minnen, A., & De Jongh, A. (2018). Effectiveness of an intensive treatment programme combining prolonged exposure and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for severe post-traumatic stress disorder. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1487225–1487225. 10.1080/20008198.2018.1487225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varker, T., Jones, K. A., Arjmand, H.-A., Hinton, M., Hiles, S. A., Freijah, I., Forbes, D., Kartal, D., Phelps, A., Bryant, R. A., McFarlane, A., Hopwood, M., & O’Donnell, M. (2021). Dropout from guideline-recommended psychological treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 4, Article 100093. 10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenmans, A., Van Minnen, A., Sleijpen, M., & De Jongh, A. (2018). The impact of childhood sexual abuse on the outcome of intensive trauma-focused treatment for PTSD. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), Article 1430962. 10.1080/20008198.2018.1430962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoet, H. A., Wagenmans, A., van Minnen, A., & de Jongh, A. (2018). Presence of the dissociative subtype of PTSD does not moderate the outcome of intensive trauma-focused treatment for PTSD. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1468707–1468707. 10.1080/20008198.2018.1468707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.