Abstract

Purpose of Review

Objective measures of residency applicants do not correlate to success within residency. While industry and business utilize standardized interviews with blinding and structured questions, residency programs have yet to uniformly incorporate these techniques. This review focuses on an in-depth evaluation of these practices and how they impact interview formatting and resident selection.

Recent Findings

Structured interviews use standardized questions that are behaviorally or situationally anchored. This requires careful creation of a scoring rubric and interviewer training, ultimately leading to improved interrater agreements and biases as compared to traditional interviews. Blinded interviews eliminate even further biases, such as halo, horn, and affinity bias. This has also been seen in using multiple interviewers, such as in the multiple mini-interview format, which also contributes to increased diversity in programs. These structured formats can be adopted to the virtual interviews as well.

Summary

There is growing literature that using structured interviews reduces bias, increases diversity, and recruits successful residents. Further research to measure the extent of incorporating this method into residency interviews will be needed in the future.

Keywords: Urology, Resident selection, Structured interviews, Blinded interviewers, Medical student

Introduction

Optimizing the criteria to rank residency applicants is a difficult task. The National Residency Matching Program (NRMP) is designed to be applicant-centric, with the overarching goal to provide favorable outcomes to the applicant while providing opportunity for programs to match high-quality candidates. From a program’s perspective, the NRMP is composed of three phases: the screening of applicants, the interview, and the creation of the rank list. While it is easy to compare candidates based on objective measures, these do not always reflect qualities required to be a successful resident or physician. Prior studies have demonstrated that objective measures such as Alpha Omega Alpha status, United States Medical Licensing Exams (USMLE), and class rank do not correlate with residency performance measures [1]. Due to the variability of these factors to predict success and recognition of the importance of the non-cognitive traits, most programs place increased emphasis on candidate interviews to assess fit [2].

Unfortunately, the interview process lacks standardization across residency programs. Industry and business have more standardized interviews and utilize best practices that include blinded interviewers, use of structured questions (situational and/or behavioral anchored questions), and skills testing. Due to residency interview heterogeneity, studies evaluating the interview as a predictor of success have failed to reliably predict who will perform well during residency. Additionally, resident success has many components, such that isolating any one factor, such as the interview, may be problematic and argues for a more holistic approach to resident selection [3]. Nevertheless, there are multiple ways the application review and interview can be standardized to promote transparency and improve resident selection.

Residency programs have begun adopting best practices from business models for interviewing, which include standardized questions, situational and/or behavioral anchored questions, blinded interviewers, and use of the multiple mini-interview (MMI) model. The focus of this review is to take a more in-depth look at practices that have become standard in business and to review the available data on the impact of these practices in resident selection.

Unstructured Versus Structured Interviews

Unstructured interviews are those in which questions are not set in advance and represent a free-flowing discussion that is conversational in nature. The course of an unstructured interview often depends on the candidate’s replies and may offer opportunities to divert away from topics that are important to applicant selection. While unstructured interviews may involve specific questions such as “tell me about a recent book you read” or “tell me about your research,” the questions do not seek to determine specific applicant attributes and may vary significantly between applicants. Due to their free-form nature, unstructured interviews may be prone to biased or illegal questions. Additionally, due to a lack of a specific scoring rubric, unstructured interviews are open to multiple biases in answer interpretation and as such generally show limited validity [4]. For the applicant, unstructured interviews allow more freedom to choose a response, with some studies reporting higher interviewee satisfaction with these questions [5].

In contrast to the unstructured interview, structured interviews use standardized questions that are written prior to an interview, are asked of every candidate, and are scored using an established rubric. Standardized questions may be behaviorally or situationally anchored [5]. Due to their uniformity, standardized interviews have higher interrater reliability and are less prone to biased or illegal questions.

Behavioral questions ask the candidate to discuss a specific response to a prior experience, which can provide insight into how an applicant may behave in the future [5]. Not only does the candidate’s response reflect a possible prediction of future behavior, it can also demonstrate the knowledge, priorities, and values of the candidate [5]. Questions are specifically targeted to reflect qualities the program is searching for (Table 1) [5–7].

Table 1.

| Behavioral question example | Trait evaluated |

|---|---|

| Tell me about a time in which you had to use your spoken communication skills to get a point across that was important to you. | Communication, patience |

| Can you tell me a time during one of your rotations where you needed to take a leadership role in the case workup or care of the patient? How did this occur and what was the outcome? | Drive, determination |

| Tell us about a time when you made a major mistake. How did you handle it? | Integrity |

| What is the most difficult experience you have had in medical school? | Recognition of own limitations |

Situational questions require an applicant to predict how they would act in a hypothetical situation and are intended to reflect a realistic scenario the applicant may encounter during residency; this can provide insight into priorities and values [5]. For example, asking what an applicant would do when receiving sole credit for something they worked on with a colleague can provide insight into the integrity of a candidate [4]. These types of questions can be especially helpful for fellowships, as applicants would already have the clinical experience of residency to draw from [5].

Using standardized questions provides a method to recruit candidates with characteristics that ultimately correlate to resident success and good performance. Indeed, structured interview scores have demonstrated an ability to predict which students perform better with regard to communication skills, patient care, and professionalism in surgical and non-surgical specialties [8•]. In fields such as radiology, non-cognitive abilities that can be evaluated in behavioral questions, such as conscientiousness or confidence, are thought to critically influence success in residency and even influence cognitive performance [1]. This has also been demonstrated in obstetrics and gynecology, where studies have shown that resident clinical performance after 1 year had a positive correlation with the rank list percentile that was generated using a structured interview process [9].

Creating Effective Structured Interviews

To be effective, standardized interview questions should be designed in a methodical manner. The first step in standardizing the interview process is determining which core values predict resident success in a particular program. To that end, educational leaders and faculty within the department should come to a consensus on the main qualities they seek in a resident. From there, questions can be formatted to elicit those traits during the interview process. Some programs have used personality assessment inventories to establish these qualities. Examples include openness to experience, humility, conscientiousness, and honesty. Further program-specific additions can be included, such as potential for success in an urban versus rural environment [10].

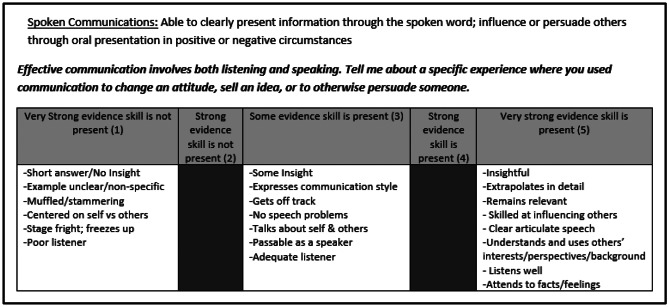

Once key attributes have been chosen and questions have been selected, a scoring rubric can be created. The scoring of each question is important as it helps define what makes a high-performing versus low-performing answer. Once a scoring system is determined, interviewers can be trained to review the questions, score applicant responses, and ensure they do not revise the questions during the interview [11]. Questions and the grading rubric should be further scrutinized through mock interviews with current residents, including discussing responses of the mock interviewee and modifying the questions and rubric prior to formal implementation [12]. Interviewer training itself is critical, as adequate training leads to improved interrater agreements [13]. Figure 1 demonstrates the steps to develop a behavioral interview question.

Fig. 1.

Example of standardized question to evaluate communication with scoring criteria

Rating the responses of the applicants can come with errors that ultimately reduce validity. For example, central tendency error involves interviewers not rating students at the extremes of a scale but rather placing all applicants in the middle; leniency versus severity refers to interviewers who either give all applicants high marks or give everyone low marks; contrast effects involve comparing one applicant to another rather than solely focusing on the rubric for each interviewee. These rating errors reflect the importance of training and providing feedback to interviewers [4].

Blinded Interviewers

Blinding the interviewers to the application prior to meeting with a candidate is intended to eliminate various biases within the interview process (Table 2) [14, 15]. In addition to grades and test scores, aspects of the application that can either introduce or exacerbate bias include photographs, demographics, letters of recommendation, selection to medical honor societies, and even hobbies. Impressions of candidates can be formed prematurely, with the interview then serving to simply confirm (or contradict) those impressions [16•]. Importantly, application blinding may also decrease implicit bias against applicants who identify as underrepresented in medicine [17].

Table 2.

| Type of bias | Definition |

|---|---|

| Halo | Taking someone’s positive characteristic and ignoring any other information that may contradict this positive perception |

| Horn | Taking someone’s negative characteristic and ignoring any other information that may contradict this negative perception |

| Affinity | Increased affinity with those who have shared experiences, such as hometown or education |

| Conformity | When the view of the majority can push one individual to also feel similarly about a candidate, regardless of whether this reflects their true feelings; can occur when there are multiple interviewers on one panel |

| Confirmation | Making an initial opinion and then looking for specific information to support that opinion |

Despite the proven success of these various interview tactics, their use in resident selection remains limited, with only 5% of general surgery programs using standardized interview questions and less than 20% using even a limited amount of blinding (e.g., blinding of photograph) [2]. Some programs have continued to rely on unblinded interviews and prioritize USMLE scores and course grades in ranking [18]. Due to their potential benefits and ability to standardize the interview process, it is critical that programs become familiar with the various interview practices so that they can select the best applicants while minimizing the significant bias in traditional interview formats.

Multiple Mini-interview (MMI)

The use of multiple interviews by multiple interviewers provides an opportunity to ask the applicant more varied questions and also allows for the averaging out of potential interviewer bias leading to more consistent applicant scoring and ability to predict applicant success [7]. Training of the interviewers in interviewing techniques, scoring, and avoiding bias is also likely to decrease scoring variability. Similarly, the use of the same group of interviewers for all candidates should be encouraged in order to limit variance in scoring amongst certain faculty [19].

One interview method that incorporates multiple interviewers and has had growing frequency in medical school interviews as well as residency interviews is the MMI model. This system provides multiple interviews in the form of 6–12 stations, each of which evaluates a non-medical question designed to assess specific non-academic applicant qualities [20]. While the MMI format can intimidate some candidates, others find that it provides an opportunity to demonstrate traits that would not be observed in an unstructured interview, such as multitasking, efficiency, flexibility, interpersonal skills, and ethical decision-making [21]. Furthermore, MMI has been shown to have increased reliability as shown in a study of five California medical schools that showed inter-interviewer consistency was higher for MMIs than traditional interviews which were unstructured and had a 1:1 ratio of interviewer to applicant [22].

The MMI format is also versatile enough to incorporate technical competencies even through a virtual platform. In general surgery interviews, MMI platforms have been designed to test traits such as communication and empathy but also clinical knowledge and surgical aptitude through anatomy questions and surgical skills (knot tying and suturing). Thus, MMIs are not only versatile, but also have an ability to evaluate cognitive traits and practical skills [23].

MMI also has the potential to reduce resident attrition. For example, in evaluating students applying to midwifery programs in Australia, attrition rates and grades were compared for admitted students using academic rank and MMI scores obtained before and after the incorporation of MMIs into their selection program. The authors found that when using MMIs, enrolled students had not only higher grades but significantly lower attrition rates. MMI was better suited to show applicants’ passion and commitment, which then led to similar mindsets of accepted applicants as well as a support network [24]. Furthermore, attrition rates have been found to be higher in female residents in general surgery programs [25]. Perhaps with greater diversity, which is associated with use of standardized interviews, the number of women can increase in surgical specialties and thus reduce attrition rate in this setting as well.

Impact of Interview Best Practices on Bias and Diversity

An imperative of all training programs is to produce a cohort of physicians with broad and diverse experiences representative of the patient populations they treat. To better address diversity within surgical residencies, particularly regarding women and those who are underrepresented in medicine, it is important that interviews be designed to minimize bias against any one portion of the applicant pool. Diverse backgrounds and cultures within a program enhance research, innovation, and collaboration as well as benefit patients [26]. Patients have shown greater satisfaction and reception when they share ethnicity or background with their provider, and underrepresented minorities in medicine often go on to work in underserved communities [27].

All interviewers undoubtedly have elements of implicit bias; Table 2 describes the common subtypes of implicit bias [14]. While it is difficult to eliminate bias in the interview process, unstructured or “traditional” interviews are more likely to risk bias toward candidates than structured interviews. Studies have demonstrated that Hispanic and Black applicants receive scores one quarter of a standard deviation lower than Caucasian applicants [28]. “Like me” bias is just one example of increased subjectivity with unstructured interviews, where interviewers prefer candidates who may look like, speak like, or share personal experiences with the interviewer [29].

Furthermore, unstructured interviews provide opportunities to ask inappropriate or illegal questions, including those that center on religion, child planning, and sexual orientation [30]. Inappropriate questions tend to be disproportionately directed toward certain groups, with women more likely to get questions regarding marital status and to be questioned and interrupted than male counterparts [28, 31].

Structured interviews, conversely, have been shown to decrease bias in the application process. Faculty trained in behavior-based interviews for fellowship applications demonstrated that there were reduced racial biases in candidate evaluations due to scoring rubrics [12]. Furthermore, as structured questions are determined prior to the interview and involve training of interviewers, structured interviews are less prone to illegal and inappropriate questions [32]. Interviewers can ask additional questions such as “could you be more specific?” with the caveat that probing should be minimized and kept consistent between applications. This way the risk of prompting the applicant toward a response is reduced [4].

Implementing Interview Types During the Virtual Interview Process

An added complexity to creating standardized interviews is incorporating a virtual platform. Even prior to the move toward virtual interviews instituted during the COVID-19 pandemic, studies on virtual interviews showed that they provided several advantages over in-person interviews, including decreased cost, reduction in time away from commitments for applicants and staff, and ability to interview at more programs. A significant limitation, for applicants and for programs, is the inability to interact informally, which allows applicants to evaluate the environment of the hospital and the surrounding community [33•]. Following their abrupt implementation in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic, virtual interviews have remained in place and likely will remain in place in some form into the future due to their significant benefits in reducing applicant cost and improving interview efficiency. Although these types of interviews are in their relative infancy in the resident selection process, studies have found that standardized questions and scoring rubrics that have been used in person can still be applied to a virtual interview setting without degrading interview quality [34].

The virtual format may also allow for further interview innovation in the form of standardized video interviews. For medical student applicants, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) has trialed a standardized video interview (SVI) that includes recording of applicant responses, scoring, and subsequent release to the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) application. Though early data in the pilot was promising, the program was not continued after the 2020 cycle due to lack of interest [35]. There is limited evidence supporting the utility of this type of interview in residency training, and one study found that these interviews did not add significant benefit as the scores did not associate with other candidate attributes such as professionalism [32]. Similarly, a separate study found no correlation between standardized video interviews and faculty scores on traits such as communication and professionalism. Granted, there was no standardization in what the faculty asked, and they were not blinded to academic performance of the applicants [36]. While there was an evaluation of six emergency medicine programs that demonstrated a positive linear correlation between the SVI score and the traditional interview score, it was a very low r coefficient; thus the authors concluded that the SVI was not adequate to replace the interview itself [37].

Conclusions: Future Steps in Urology and Beyond

The shift to structured interviews in urology has been slow. Within the last decade, studies consistent with other specialties demonstrated that urology program directors prioritized USMLE scores, reference letters, and away rotations at the program director’s institution as the key factors in choosing applicants [38]. More recently, a survey of urology programs found < 10% blinded the recruitment team at the screening step, with < 20% blinding the recruitment team during the interview itself [39]. In 2020 our program began using structured interview questions and blinded interviewers to all but the personal statement and letters of recommendation. After querying faculty and interviewees, we have found that most interviewers do not miss the additional information, and applicants feel that they are able to have more eye contact with faculty who are not looking down at the application during the interview. Structured behavioral interview questions have allowed us to focus on the key attributes important to our program. With time we hope to see that inclusion of these metrics helps diversify our resident cohort, improve resident satisfaction with the training program, and produce successful future urologists.

Despite the slow transition in urology and other fields, there is a growing body of literature in support of standardized interviews for evaluating key candidate traits that ultimately lead to resident success and reducing bias while increasing diversity. With time, the hope is that programs will continue incorporating these types of interviews in the resident selection process.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

This article is part of Topical Collection on Education

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

- 1.ALTMAIER, EM, et al., The predictive utility of behavior-based interviewing compared with traditional interviewing in the selection of radiology residents. Investigative Radiology 1992;27(5):385–389 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Kim RH, et al. General surgery residency interviews: are we following best practices? Am J Surg. 2016;211(2):476–481.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephenson-Famy A, et al. Use of the interview in resident candidate selection: a review of the literature. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(4):539–548. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00236.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Best practices for conducting residency interviews, A.o.A.M. Colleges, Editor. 2016

- 5.Black C, Budner H, Motta AL. Enhancing the residency interview process with the inclusion of standardised questions. Postgrad Med J. 2018;94(1110):244–246. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2017-135385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartwell CJ, Johnson CD, Posthuma RA. Are we asking the right questions? Predictive validity comparison of four structured interview question types. J Bus Res. 2019;100:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.03.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beran B, et al. An analysis of obstetrics-gynecology residency interview methods in a single institution. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(2):414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.• Marcus-Blank B, et al. Predicting performance of first-year residents: correlations between structured interview, licensure exam, and competency scores in a multi-institutional study. Acad Med. 2019;94(3):378–87. Authors administered 18 behavioral structured interview questions (SI) to measure key noncognitive competencies across 14 programs (13 residency, 1 fellowship) from 6 institutions to determine correlation first-year resident milestone performance in the ACGME's core competency domains and overall scores. They found SI scores predicted midyear and year-end overall performance and year-end performance on patient care, interpersonal and communication skills, and professionalism competencies and that SI scores contributed incremental validity over USMLE scores in predicting year-end performance on patient care, interpersonal and communication skills, and professionalism. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Olawaiye A, Yeh J, Withiam-Leitch M. Resident selection process and prediction of clinical performance in an obstetrics and gynecology program. Teach Learn Med. 2006;18(4):310–315. doi: 10.1207/s15328015tlm1804_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prystowsky MB, et al. Prioritizing the interview in selecting resident applicants: behavioral interviews to determine goodness of fit. Academic pathology. 2021;8:23742895211052885–23742895211052885. doi: 10.1177/23742895211052885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breitkopf DM, Vaughan LE, Hopkins MR. Correlation of behavioral interviewing performance with obstetrics and gynecology residency applicant characteristics☆?>. J Surg Educ. 2016;73(6):954–958. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langhan ML, Goldman MP, Tiyyagura G. Can behavior-based interviews reduce bias in fellowship applicant assessment? Acad Pediatr. 2022;22(3):478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2021.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardner AK, D’Onofrio BC, Dunkin BJ. Can we get faculty interviewers on the same page? An examination of a structured interview course for surgeons. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(1):72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oberai H, Ila Mehrotra A, Unconscious bias: thinking without thinking. Hum Resour Manag Int Dig 2018;26(6):14–17.

- 15.Hull L, Sevdalis N. Advances in teaching and assessing nontechnical skills. Surg Clin North Am. 2015;95(4):869–885. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.• Balhara KS, et al. Navigating bias on interview day: strategies for charting an inclusive and equitable course. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(4):466–70. Strategies for decreasing bias in the interview process based on best practices from medical and corporate literature, cognitive psychology theory, and the authors' experiences. Provides simple, actionable and accessible strategies for navigating and mitigating the pitfalls of bias during residency interview [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Haag J, et al. Impact of blinding interviewers to written applications on ranking of Gynecologic Oncology fellowship applicants from groups underrepresented in medicine. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2022;39:100935. doi: 10.1016/j.gore.2022.100935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kasales C, Peterson C, Gagnon E. Interview techniques utilized in radiology resident selection-a survey of the APDR. Acad Radiol. 2019;26(7):989–998. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levashina J, et al. The structured employment interview: narrative and quantitative review of the research literature. Pers Psychol. 2014;67(1):241–293. doi: 10.1111/peps.12052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al Abri R, Mathew J, Jeyaseelan L. Multiple mini-interview consistency and satisfactoriness for residency program recruitment: Oman evidence. Oman Med J 2019;34(3):218–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Boysen-Osborn M, et al. A multiple-mini interview (MMI) for emergency medicine residency admissions: a brief report and qualitative analysis. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2018;6(4):176–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jerant A, et al. Reliability of multiple mini-interviews and traditional interviews within and between institutions: a study of five California medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):190. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-1030-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lund S, et al. Conducting virtual simulated skills multiple mini-interviews for general surgery residency interviews. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(6):1786–1790. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheehan A, et al. The impact of multiple mini interviews on the attrition and academic outcomes of midwifery students. Women Birth. 2022;35(4):e318–e327. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2021.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khoushhal Z, et al. Prevalence and causes of attrition among surgical residents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(3):265–272. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.4086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeBenedectis CM, et al. A program director’s guide to cultivating diversity and inclusion in radiology residency recruitment. Acad Radiol. 2020;27(6):864–867. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2019.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Figueroa O. The significance of recruiting underrepresented minorities in medicine: an examination of the need for effective approaches used in admissions by higher education institutions. Med Educ Online. 2014;19:24891–24891. doi: 10.3402/meo.v19.24891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costa PC, Gardner AK. Strategies to increase diversity in surgical residency. Current Surgery Reports. 2021;9(5):11. doi: 10.1007/s40137-021-00288-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gardner AK. How can best practices in recruitment and selection improve diversity in surgery? Ann Surg 2018:267(1) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Resident Match process policy and guidelines. 2022; Available from: https://sauweb.org/match-program/resident-match-process.aspx.

- 31.Otugo O, et al. Bias in recruitment: a focus on virtual interviews and holistic review to advance diversity. AEM Education and Training. 2021;5(S1):S135–S139. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hughes RH, Kleinschmidt S, Sheng AY. Using structured interviews to reduce bias in emergency medicine residency recruitment: worth a second look. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5(Suppl 1):S130–s134. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.• Huppert LA, et al. Virtual interviews at graduate medical education training programs: determining evidence-based best practices. Acad Med. 2021;96(8):1137–45. Review of existing literature regarding virtual interviews that summarizes best practices for interviews the advantages and disadvantages of the virtual interview format. The authors make the following recommendations: develop a detailed plan for the interview process, consider using standardized interview questions, recognize and respond to potential biases that may be amplified with the virtual interview format, prepare your own trainees for virtual interviews, develop electronic materials and virtual social events to approximate the interview day, and collect data about virtual interviews at your own institution [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Chou DW, et al. Otolaryngology residency interviews in a socially distanced world: strategies to recruit and assess applicants. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(5):903–908. doi: 10.1177/0194599820957961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.AAMC Standardized Video Interview Evaluation Summary. 2022.

- 36.Schnapp BH, et al. Assessing residency applicants’ communication and professionalism: standardized video interview scores compared to faculty gestalt. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20(1):132–137. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2018.10.39709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chung AS, et al. How well does the standardized video interview score correlate with traditional interview performance? Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2019;20(5):726–730. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2019.7.42731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weissbart SJ, Stock JA, Wein AJ. Program directors’ criteria for selection into urology residency. Urology. 2015;85(4):731–736. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chantal Ghanney Simons E, et al. MP19–05 Landscape analysis of the use of holistic review in the urology residency match process. J Urol 2022;207:e308